User login

Detecting sepsis: Are two opinions better than one?

Sepsis is a leading cause of hospital mortality in the United States, contributing to up to half of all deaths.1 If the infection is identified and treated early, however, its associated morbidity and mortality can be significantly reduced.2 The 2001 sepsis guidelines define sepsis as the suspicion of infection plus meeting 2 or more systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria.3 Although the utility of SIRS criteria has been extensively debated, providers’ accuracy and agreement regarding suspicion of infection are not yet fully characterized. This is very important, as the source of infection is often not identified in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.4

Although much attention recently has been given to ideal objective criteria for accurately identifying sepsis, less is known about what constitutes ideal subjective criteria and who can best make that assessment.5-7 We conducted a study to measure providers’ agreement regarding this subjective assessment and the impact of that agreement on patient outcomes.

METHODS

We performed a secondary analysis of prospectively collected data on consecutive adults hospitalized on a general medicine ward at an academic medical center between April 1, 2014 and March 31, 2015. This study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board with a waiver of consent.

A sepsis screening tool was developed locally as part of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative8 (Supplemental Figure). This tool was completed by bedside nurses for each patient during each shift. Bedside registered nurse (RN) suspicion of infection was deemed positive if the nurse answered yes to question 2: “Does the patient have evidence of an active infection?” We compared RN assessment with assessment by the ordering provider, a medical doctor or advanced practice professionals (MD/APP), using an existing order for antibiotics or a new order for either blood or urine cultures placed within 12 hours before nursing screen time to indicate MD/APP suspicion of infection.

All nursing screens were transcribed into an electronic database, excluding screens not performed, or missing RN suspicion of infection. For quality purposes, screening data were merged with electronic health record data to verify SIRS criteria at the time of the screens as well as the presence of culture and/or antibiotic orders preceding the screens. Outcome data were obtained from an administrative database and confirmed by chart review using the 2001 sepsis definitions.6 Data were de-identified and time-shifted before this analysis. SIRS-positive criteria were defined as meeting 2 or more of the following: temperature higher than 38°C or lower than 36°C; heart rate higher than 90 beats per minute; respiratory rate more than 20 breaths per minute; and white blood cell count more than 2,000/mm3 or less than 4,000/mm3.The primary clinical outcome was progression to severe sepsis or septic shock. Secondary outcomes included transfer to intensive care unit (ICU) and in-hospital mortality. Given that RN and MD/APP suspicion of infection can vary over time, only the initial screen for each patient was used in assessing progression to severe sepsis or septic shock and in-hospital mortality. All available screens were used to investigate the association between each provider’s suspicion of infection over time and ICU transfer.

Demographic characteristics were compared using the χ2 test and analysis of variance, as appropriate. Provider agreement was evaluated with a weighted κ statistic. Fisher exact tests were used to compare proportions of mortality and severe sepsis/septic shock, and the McNemar test was used to compare proportions of ICU transfers. The association of outcomes based on provider agreement was evaluated with a nonparametric test for trend.

RESULTS

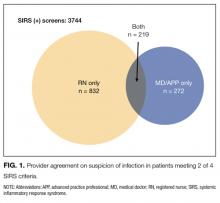

During the study period, 1386 distinct patients had 13,223 screening opportunities, with a 95.4% compliance rate. A total of 1127 screens were excluded for missing nursing documentation of suspicion of infection, leaving 1192 first screens and 11,489 total screens for analysis. Of the completed screens, 3744 (32.6%) met SIRS criteria; suspicion of infection was noted by both RN and MD/APP in 5.8% of cases, by RN only in 22.2%, by MD/APP only in 7.2%, and by neither provider in 64.7% (Figure 1). Overall agreement rate was 80.7% for suspicion of infection (κ = 0.11, P < 0.001). Demographics by subgroup are shown in the Supplemental Table. Progression to severe sepsis or shock was highest when both providers suspected infection in a SIRS-positive patient (17.7%), was substantially reduced with single-provider suspicion (6.0%), and was lowest when neither provider suspected infection (1.5%) (P < 0.001). A similar trend was found for in-hospital mortality (both providers, 6.3%; single provider, 2.7%; neither provider, 2.5%; P = 0.01). Compared with MD/APP-only suspicion, SIRS-positive patients in whom only RNs suspected infection had similar frequency of progression to severe sepsis or septic shock (6.5% vs 5.6%; P = 0.52) and higher mortality (5.0% vs 1.1%; P = 0.32), though these findings were not statistically significant.

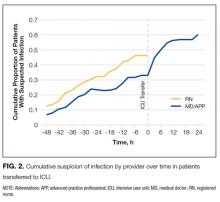

For the 121 patients (10.2%) transferred to ICU, RNs were more likely than MD/APPs to suspect infection at all time points (Figure 2). The difference was small (P = 0.29) 48 hours before transfer (RN, 12.5%; MD/APP, 5.6%) but became more pronounced (P = 0.06) by 3 hours before transfer (RN, 46.3%; MD/APP, 33.1%). Nursing assessments were not available after transfer, but 3 hours after transfer the proportion of patients who met MD/APP suspicion-of-infection criteria (44.6%) was similar (P = 0.90) to that of the RNs 3 hours before transfer (46.3%).

DISCUSSION

Our findings reveal that bedside nurses and ordering providers routinely have discordant assessments regarding presence of infection. Specifically, when RNs are asked to screen patients on the wards, they are suspicious of infection more often than MD/APPs are, and they suspect infection earlier in ICU transfer patients. These findings have significant implications for patient care, compliance with the new national SEP-1 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services quality measure, and identification of appropriate patients for enrollment in sepsis-related clinical trials.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore agreement between bedside RN and MD/APP suspicion of infection in sepsis screening and its association with patient outcomes. Studies on nurse and physician concordance in other domains have had mixed findings.9-11 The high discordance rate found in our study points to the highly subjective nature of suspicion of infection.

Our finding that RNs suspect infection earlier in patients transferred to ICU suggests nursing suspicion has value above and beyond current practice. A possible explanation for the higher rate of RN suspicion, and earlier RN suspicion, is that bedside nurses spend substantially more time with their patients and are more attuned to subtle changes that often occur before any objective signs of deterioration. This phenomenon is well documented and accounts for why rapid response calling criteria often include “nurse worry or concern.”12,13 Thus, nurse intuition may be an important signal for early identification of patients at high risk for sepsis.

That about one third of all screens met SIRS criteria and that almost two thirds of those screens were not thought by RN or MD/APP to be caused by infection add to the literature demonstrating the limited value of SIRS as a screening tool for sepsis.14 To address this issue, the 2016 sepsis definitions propose using the quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) to identify patients at high risk for clinical deterioration; however, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign continues to encourage sepsis screening using the SIRS criteria.15

Limitations of this study include its lack of generalizability, as it was conducted with general medical patients at a single center. Second, we did not specifically ask the MD/APPs whether they suspected infection; instead, we relied on their ordering practices. Third, RN and MD/APP assessments were not independent, as RNs had access to MD/APP orders before making their own assessments, which could bias our results.

Discordance in provider suspicion of infection is common, with RNs documenting suspicion more often than MD/APPs, and earlier in patients transferred to ICU. Suspicion by either provider alone is associated with higher risk for sepsis progression and in-hospital mortality than is the case when neither provider suspects infection. Thus, a collaborative method that includes both RNs and MD/APPs may improve the accuracy and timing of sepsis detection on the wards.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative at the University of Chicago for their help in data collection and review, especially Meredith Borak, Rita Lanier, Mary Ann Francisco, and Bill Marsack. The authors also thank Thomas Best and Mary-Kate Springman for their assistance in data entry and Nicole Twu for administrative support. Data from this study were provided by the Clinical Research Data Warehouse (CRDW) maintained by the Center for Research Informatics (CRI) at the University of Chicago. CRI is funded by the Biological Sciences Division of the Institute for Translational Medicine/Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) (National Institutes of Health UL1 TR000430) at the University of Chicago.

Disclosures

Dr. Bhattacharjee is supported by postdoctoral training grant 4T32HS000078 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Drs. Churpek and Edelson have a patent pending (ARCD.P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. Dr. Churpek is supported by career development award K08 HL121080 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Edelson has received research support from Philips Healthcare (Andover, Massachusetts), American Heart Association (Dallas, Texas), and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway) and has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, Illinois), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Liu V, Escobar GJ, Greene JD, et al. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA. 2014;312(1):90-92. PubMed

2. Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al; Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368-1377. PubMed

3. Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al; SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250-1256. PubMed

4. Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, et al; Sepsis Occurrence in Acutely Ill Patients Investigators. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(2):344-353. PubMed

5. Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Pilcher D, Cooper DJ, Bellomo R. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1629-1638. PubMed

6. Vincent JL, Opal SM, Marshall JC, Tracey KJ. Sepsis definitions: time for change. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):774-775. PubMed

7. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810. PubMed

8. Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) Sepsis on the Floors Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative. Frequently asked questions (FAQs). Society of Critical Care Medicine website. http://www.survivingsepsis.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/About-Collaboratives.pdf. Published October 8, 2013.

9. Fiesseler F, Szucs P, Kec R, Richman PB. Can nurses appropriately interpret the Ottawa ankle rule? Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22(3):145-148. PubMed

10. Blomberg H, Lundström E, Toss H, Gedeborg R, Johansson J. Agreement between ambulance nurses and physicians in assessing stroke patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2014;129(1):4955. PubMed

11. Neville TH, Wiley JF, Yamamoto MC, et al. Concordance of nurses and physicians on whether critical care patients are receiving futile treatment. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(5):403410. PubMed

12. Odell M, Victor C, Oliver D. Nurses’ role in detecting deterioration in ward patients: systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(10):1992-2006. PubMed

13. Howell MD, Ngo L, Folcarelli P, et al. Sustained effectiveness of a primary-team-based rapid response system. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(9):2562-2568. PubMed

14. Churpek MM, Zadravecz FJ, Winslow C, Howell MD, Edelson DP. Incidence and prognostic value of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and organ dysfunctions in ward patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(8):958-964. PubMed

15. Antonelli M, DeBacker D, Dorman T, Kleinpell R, Levy M, Rhodes A; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Executive Committee. Surviving Sepsis Campaign responds to Sepsis-3. Society of Critical Care Medicine website. http://www.survivingsepsis.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/SSC-Statements-Sepsis-Definitions-3-2016.pdf. Published March 1, 2016. Accessed May 11, 2016.

Sepsis is a leading cause of hospital mortality in the United States, contributing to up to half of all deaths.1 If the infection is identified and treated early, however, its associated morbidity and mortality can be significantly reduced.2 The 2001 sepsis guidelines define sepsis as the suspicion of infection plus meeting 2 or more systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria.3 Although the utility of SIRS criteria has been extensively debated, providers’ accuracy and agreement regarding suspicion of infection are not yet fully characterized. This is very important, as the source of infection is often not identified in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.4

Although much attention recently has been given to ideal objective criteria for accurately identifying sepsis, less is known about what constitutes ideal subjective criteria and who can best make that assessment.5-7 We conducted a study to measure providers’ agreement regarding this subjective assessment and the impact of that agreement on patient outcomes.

METHODS

We performed a secondary analysis of prospectively collected data on consecutive adults hospitalized on a general medicine ward at an academic medical center between April 1, 2014 and March 31, 2015. This study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board with a waiver of consent.

A sepsis screening tool was developed locally as part of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative8 (Supplemental Figure). This tool was completed by bedside nurses for each patient during each shift. Bedside registered nurse (RN) suspicion of infection was deemed positive if the nurse answered yes to question 2: “Does the patient have evidence of an active infection?” We compared RN assessment with assessment by the ordering provider, a medical doctor or advanced practice professionals (MD/APP), using an existing order for antibiotics or a new order for either blood or urine cultures placed within 12 hours before nursing screen time to indicate MD/APP suspicion of infection.

All nursing screens were transcribed into an electronic database, excluding screens not performed, or missing RN suspicion of infection. For quality purposes, screening data were merged with electronic health record data to verify SIRS criteria at the time of the screens as well as the presence of culture and/or antibiotic orders preceding the screens. Outcome data were obtained from an administrative database and confirmed by chart review using the 2001 sepsis definitions.6 Data were de-identified and time-shifted before this analysis. SIRS-positive criteria were defined as meeting 2 or more of the following: temperature higher than 38°C or lower than 36°C; heart rate higher than 90 beats per minute; respiratory rate more than 20 breaths per minute; and white blood cell count more than 2,000/mm3 or less than 4,000/mm3.The primary clinical outcome was progression to severe sepsis or septic shock. Secondary outcomes included transfer to intensive care unit (ICU) and in-hospital mortality. Given that RN and MD/APP suspicion of infection can vary over time, only the initial screen for each patient was used in assessing progression to severe sepsis or septic shock and in-hospital mortality. All available screens were used to investigate the association between each provider’s suspicion of infection over time and ICU transfer.

Demographic characteristics were compared using the χ2 test and analysis of variance, as appropriate. Provider agreement was evaluated with a weighted κ statistic. Fisher exact tests were used to compare proportions of mortality and severe sepsis/septic shock, and the McNemar test was used to compare proportions of ICU transfers. The association of outcomes based on provider agreement was evaluated with a nonparametric test for trend.

RESULTS

During the study period, 1386 distinct patients had 13,223 screening opportunities, with a 95.4% compliance rate. A total of 1127 screens were excluded for missing nursing documentation of suspicion of infection, leaving 1192 first screens and 11,489 total screens for analysis. Of the completed screens, 3744 (32.6%) met SIRS criteria; suspicion of infection was noted by both RN and MD/APP in 5.8% of cases, by RN only in 22.2%, by MD/APP only in 7.2%, and by neither provider in 64.7% (Figure 1). Overall agreement rate was 80.7% for suspicion of infection (κ = 0.11, P < 0.001). Demographics by subgroup are shown in the Supplemental Table. Progression to severe sepsis or shock was highest when both providers suspected infection in a SIRS-positive patient (17.7%), was substantially reduced with single-provider suspicion (6.0%), and was lowest when neither provider suspected infection (1.5%) (P < 0.001). A similar trend was found for in-hospital mortality (both providers, 6.3%; single provider, 2.7%; neither provider, 2.5%; P = 0.01). Compared with MD/APP-only suspicion, SIRS-positive patients in whom only RNs suspected infection had similar frequency of progression to severe sepsis or septic shock (6.5% vs 5.6%; P = 0.52) and higher mortality (5.0% vs 1.1%; P = 0.32), though these findings were not statistically significant.

For the 121 patients (10.2%) transferred to ICU, RNs were more likely than MD/APPs to suspect infection at all time points (Figure 2). The difference was small (P = 0.29) 48 hours before transfer (RN, 12.5%; MD/APP, 5.6%) but became more pronounced (P = 0.06) by 3 hours before transfer (RN, 46.3%; MD/APP, 33.1%). Nursing assessments were not available after transfer, but 3 hours after transfer the proportion of patients who met MD/APP suspicion-of-infection criteria (44.6%) was similar (P = 0.90) to that of the RNs 3 hours before transfer (46.3%).

DISCUSSION

Our findings reveal that bedside nurses and ordering providers routinely have discordant assessments regarding presence of infection. Specifically, when RNs are asked to screen patients on the wards, they are suspicious of infection more often than MD/APPs are, and they suspect infection earlier in ICU transfer patients. These findings have significant implications for patient care, compliance with the new national SEP-1 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services quality measure, and identification of appropriate patients for enrollment in sepsis-related clinical trials.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore agreement between bedside RN and MD/APP suspicion of infection in sepsis screening and its association with patient outcomes. Studies on nurse and physician concordance in other domains have had mixed findings.9-11 The high discordance rate found in our study points to the highly subjective nature of suspicion of infection.

Our finding that RNs suspect infection earlier in patients transferred to ICU suggests nursing suspicion has value above and beyond current practice. A possible explanation for the higher rate of RN suspicion, and earlier RN suspicion, is that bedside nurses spend substantially more time with their patients and are more attuned to subtle changes that often occur before any objective signs of deterioration. This phenomenon is well documented and accounts for why rapid response calling criteria often include “nurse worry or concern.”12,13 Thus, nurse intuition may be an important signal for early identification of patients at high risk for sepsis.

That about one third of all screens met SIRS criteria and that almost two thirds of those screens were not thought by RN or MD/APP to be caused by infection add to the literature demonstrating the limited value of SIRS as a screening tool for sepsis.14 To address this issue, the 2016 sepsis definitions propose using the quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) to identify patients at high risk for clinical deterioration; however, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign continues to encourage sepsis screening using the SIRS criteria.15

Limitations of this study include its lack of generalizability, as it was conducted with general medical patients at a single center. Second, we did not specifically ask the MD/APPs whether they suspected infection; instead, we relied on their ordering practices. Third, RN and MD/APP assessments were not independent, as RNs had access to MD/APP orders before making their own assessments, which could bias our results.

Discordance in provider suspicion of infection is common, with RNs documenting suspicion more often than MD/APPs, and earlier in patients transferred to ICU. Suspicion by either provider alone is associated with higher risk for sepsis progression and in-hospital mortality than is the case when neither provider suspects infection. Thus, a collaborative method that includes both RNs and MD/APPs may improve the accuracy and timing of sepsis detection on the wards.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative at the University of Chicago for their help in data collection and review, especially Meredith Borak, Rita Lanier, Mary Ann Francisco, and Bill Marsack. The authors also thank Thomas Best and Mary-Kate Springman for their assistance in data entry and Nicole Twu for administrative support. Data from this study were provided by the Clinical Research Data Warehouse (CRDW) maintained by the Center for Research Informatics (CRI) at the University of Chicago. CRI is funded by the Biological Sciences Division of the Institute for Translational Medicine/Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) (National Institutes of Health UL1 TR000430) at the University of Chicago.

Disclosures

Dr. Bhattacharjee is supported by postdoctoral training grant 4T32HS000078 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Drs. Churpek and Edelson have a patent pending (ARCD.P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. Dr. Churpek is supported by career development award K08 HL121080 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Edelson has received research support from Philips Healthcare (Andover, Massachusetts), American Heart Association (Dallas, Texas), and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway) and has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, Illinois), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Sepsis is a leading cause of hospital mortality in the United States, contributing to up to half of all deaths.1 If the infection is identified and treated early, however, its associated morbidity and mortality can be significantly reduced.2 The 2001 sepsis guidelines define sepsis as the suspicion of infection plus meeting 2 or more systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria.3 Although the utility of SIRS criteria has been extensively debated, providers’ accuracy and agreement regarding suspicion of infection are not yet fully characterized. This is very important, as the source of infection is often not identified in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.4

Although much attention recently has been given to ideal objective criteria for accurately identifying sepsis, less is known about what constitutes ideal subjective criteria and who can best make that assessment.5-7 We conducted a study to measure providers’ agreement regarding this subjective assessment and the impact of that agreement on patient outcomes.

METHODS

We performed a secondary analysis of prospectively collected data on consecutive adults hospitalized on a general medicine ward at an academic medical center between April 1, 2014 and March 31, 2015. This study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board with a waiver of consent.

A sepsis screening tool was developed locally as part of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative8 (Supplemental Figure). This tool was completed by bedside nurses for each patient during each shift. Bedside registered nurse (RN) suspicion of infection was deemed positive if the nurse answered yes to question 2: “Does the patient have evidence of an active infection?” We compared RN assessment with assessment by the ordering provider, a medical doctor or advanced practice professionals (MD/APP), using an existing order for antibiotics or a new order for either blood or urine cultures placed within 12 hours before nursing screen time to indicate MD/APP suspicion of infection.

All nursing screens were transcribed into an electronic database, excluding screens not performed, or missing RN suspicion of infection. For quality purposes, screening data were merged with electronic health record data to verify SIRS criteria at the time of the screens as well as the presence of culture and/or antibiotic orders preceding the screens. Outcome data were obtained from an administrative database and confirmed by chart review using the 2001 sepsis definitions.6 Data were de-identified and time-shifted before this analysis. SIRS-positive criteria were defined as meeting 2 or more of the following: temperature higher than 38°C or lower than 36°C; heart rate higher than 90 beats per minute; respiratory rate more than 20 breaths per minute; and white blood cell count more than 2,000/mm3 or less than 4,000/mm3.The primary clinical outcome was progression to severe sepsis or septic shock. Secondary outcomes included transfer to intensive care unit (ICU) and in-hospital mortality. Given that RN and MD/APP suspicion of infection can vary over time, only the initial screen for each patient was used in assessing progression to severe sepsis or septic shock and in-hospital mortality. All available screens were used to investigate the association between each provider’s suspicion of infection over time and ICU transfer.

Demographic characteristics were compared using the χ2 test and analysis of variance, as appropriate. Provider agreement was evaluated with a weighted κ statistic. Fisher exact tests were used to compare proportions of mortality and severe sepsis/septic shock, and the McNemar test was used to compare proportions of ICU transfers. The association of outcomes based on provider agreement was evaluated with a nonparametric test for trend.

RESULTS

During the study period, 1386 distinct patients had 13,223 screening opportunities, with a 95.4% compliance rate. A total of 1127 screens were excluded for missing nursing documentation of suspicion of infection, leaving 1192 first screens and 11,489 total screens for analysis. Of the completed screens, 3744 (32.6%) met SIRS criteria; suspicion of infection was noted by both RN and MD/APP in 5.8% of cases, by RN only in 22.2%, by MD/APP only in 7.2%, and by neither provider in 64.7% (Figure 1). Overall agreement rate was 80.7% for suspicion of infection (κ = 0.11, P < 0.001). Demographics by subgroup are shown in the Supplemental Table. Progression to severe sepsis or shock was highest when both providers suspected infection in a SIRS-positive patient (17.7%), was substantially reduced with single-provider suspicion (6.0%), and was lowest when neither provider suspected infection (1.5%) (P < 0.001). A similar trend was found for in-hospital mortality (both providers, 6.3%; single provider, 2.7%; neither provider, 2.5%; P = 0.01). Compared with MD/APP-only suspicion, SIRS-positive patients in whom only RNs suspected infection had similar frequency of progression to severe sepsis or septic shock (6.5% vs 5.6%; P = 0.52) and higher mortality (5.0% vs 1.1%; P = 0.32), though these findings were not statistically significant.

For the 121 patients (10.2%) transferred to ICU, RNs were more likely than MD/APPs to suspect infection at all time points (Figure 2). The difference was small (P = 0.29) 48 hours before transfer (RN, 12.5%; MD/APP, 5.6%) but became more pronounced (P = 0.06) by 3 hours before transfer (RN, 46.3%; MD/APP, 33.1%). Nursing assessments were not available after transfer, but 3 hours after transfer the proportion of patients who met MD/APP suspicion-of-infection criteria (44.6%) was similar (P = 0.90) to that of the RNs 3 hours before transfer (46.3%).

DISCUSSION

Our findings reveal that bedside nurses and ordering providers routinely have discordant assessments regarding presence of infection. Specifically, when RNs are asked to screen patients on the wards, they are suspicious of infection more often than MD/APPs are, and they suspect infection earlier in ICU transfer patients. These findings have significant implications for patient care, compliance with the new national SEP-1 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services quality measure, and identification of appropriate patients for enrollment in sepsis-related clinical trials.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore agreement between bedside RN and MD/APP suspicion of infection in sepsis screening and its association with patient outcomes. Studies on nurse and physician concordance in other domains have had mixed findings.9-11 The high discordance rate found in our study points to the highly subjective nature of suspicion of infection.

Our finding that RNs suspect infection earlier in patients transferred to ICU suggests nursing suspicion has value above and beyond current practice. A possible explanation for the higher rate of RN suspicion, and earlier RN suspicion, is that bedside nurses spend substantially more time with their patients and are more attuned to subtle changes that often occur before any objective signs of deterioration. This phenomenon is well documented and accounts for why rapid response calling criteria often include “nurse worry or concern.”12,13 Thus, nurse intuition may be an important signal for early identification of patients at high risk for sepsis.

That about one third of all screens met SIRS criteria and that almost two thirds of those screens were not thought by RN or MD/APP to be caused by infection add to the literature demonstrating the limited value of SIRS as a screening tool for sepsis.14 To address this issue, the 2016 sepsis definitions propose using the quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) to identify patients at high risk for clinical deterioration; however, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign continues to encourage sepsis screening using the SIRS criteria.15

Limitations of this study include its lack of generalizability, as it was conducted with general medical patients at a single center. Second, we did not specifically ask the MD/APPs whether they suspected infection; instead, we relied on their ordering practices. Third, RN and MD/APP assessments were not independent, as RNs had access to MD/APP orders before making their own assessments, which could bias our results.

Discordance in provider suspicion of infection is common, with RNs documenting suspicion more often than MD/APPs, and earlier in patients transferred to ICU. Suspicion by either provider alone is associated with higher risk for sepsis progression and in-hospital mortality than is the case when neither provider suspects infection. Thus, a collaborative method that includes both RNs and MD/APPs may improve the accuracy and timing of sepsis detection on the wards.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative at the University of Chicago for their help in data collection and review, especially Meredith Borak, Rita Lanier, Mary Ann Francisco, and Bill Marsack. The authors also thank Thomas Best and Mary-Kate Springman for their assistance in data entry and Nicole Twu for administrative support. Data from this study were provided by the Clinical Research Data Warehouse (CRDW) maintained by the Center for Research Informatics (CRI) at the University of Chicago. CRI is funded by the Biological Sciences Division of the Institute for Translational Medicine/Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) (National Institutes of Health UL1 TR000430) at the University of Chicago.

Disclosures

Dr. Bhattacharjee is supported by postdoctoral training grant 4T32HS000078 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Drs. Churpek and Edelson have a patent pending (ARCD.P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. Dr. Churpek is supported by career development award K08 HL121080 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Edelson has received research support from Philips Healthcare (Andover, Massachusetts), American Heart Association (Dallas, Texas), and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway) and has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, Illinois), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Liu V, Escobar GJ, Greene JD, et al. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA. 2014;312(1):90-92. PubMed

2. Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al; Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368-1377. PubMed

3. Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al; SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250-1256. PubMed

4. Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, et al; Sepsis Occurrence in Acutely Ill Patients Investigators. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(2):344-353. PubMed

5. Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Pilcher D, Cooper DJ, Bellomo R. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1629-1638. PubMed

6. Vincent JL, Opal SM, Marshall JC, Tracey KJ. Sepsis definitions: time for change. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):774-775. PubMed

7. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810. PubMed

8. Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) Sepsis on the Floors Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative. Frequently asked questions (FAQs). Society of Critical Care Medicine website. http://www.survivingsepsis.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/About-Collaboratives.pdf. Published October 8, 2013.

9. Fiesseler F, Szucs P, Kec R, Richman PB. Can nurses appropriately interpret the Ottawa ankle rule? Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22(3):145-148. PubMed

10. Blomberg H, Lundström E, Toss H, Gedeborg R, Johansson J. Agreement between ambulance nurses and physicians in assessing stroke patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2014;129(1):4955. PubMed

11. Neville TH, Wiley JF, Yamamoto MC, et al. Concordance of nurses and physicians on whether critical care patients are receiving futile treatment. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(5):403410. PubMed

12. Odell M, Victor C, Oliver D. Nurses’ role in detecting deterioration in ward patients: systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(10):1992-2006. PubMed

13. Howell MD, Ngo L, Folcarelli P, et al. Sustained effectiveness of a primary-team-based rapid response system. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(9):2562-2568. PubMed

14. Churpek MM, Zadravecz FJ, Winslow C, Howell MD, Edelson DP. Incidence and prognostic value of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and organ dysfunctions in ward patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(8):958-964. PubMed

15. Antonelli M, DeBacker D, Dorman T, Kleinpell R, Levy M, Rhodes A; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Executive Committee. Surviving Sepsis Campaign responds to Sepsis-3. Society of Critical Care Medicine website. http://www.survivingsepsis.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/SSC-Statements-Sepsis-Definitions-3-2016.pdf. Published March 1, 2016. Accessed May 11, 2016.

1. Liu V, Escobar GJ, Greene JD, et al. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA. 2014;312(1):90-92. PubMed

2. Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al; Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368-1377. PubMed

3. Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al; SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250-1256. PubMed

4. Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, et al; Sepsis Occurrence in Acutely Ill Patients Investigators. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(2):344-353. PubMed

5. Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Pilcher D, Cooper DJ, Bellomo R. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1629-1638. PubMed

6. Vincent JL, Opal SM, Marshall JC, Tracey KJ. Sepsis definitions: time for change. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):774-775. PubMed

7. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810. PubMed

8. Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) Sepsis on the Floors Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative. Frequently asked questions (FAQs). Society of Critical Care Medicine website. http://www.survivingsepsis.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/About-Collaboratives.pdf. Published October 8, 2013.

9. Fiesseler F, Szucs P, Kec R, Richman PB. Can nurses appropriately interpret the Ottawa ankle rule? Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22(3):145-148. PubMed

10. Blomberg H, Lundström E, Toss H, Gedeborg R, Johansson J. Agreement between ambulance nurses and physicians in assessing stroke patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2014;129(1):4955. PubMed

11. Neville TH, Wiley JF, Yamamoto MC, et al. Concordance of nurses and physicians on whether critical care patients are receiving futile treatment. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(5):403410. PubMed

12. Odell M, Victor C, Oliver D. Nurses’ role in detecting deterioration in ward patients: systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(10):1992-2006. PubMed

13. Howell MD, Ngo L, Folcarelli P, et al. Sustained effectiveness of a primary-team-based rapid response system. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(9):2562-2568. PubMed

14. Churpek MM, Zadravecz FJ, Winslow C, Howell MD, Edelson DP. Incidence and prognostic value of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and organ dysfunctions in ward patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(8):958-964. PubMed

15. Antonelli M, DeBacker D, Dorman T, Kleinpell R, Levy M, Rhodes A; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Executive Committee. Surviving Sepsis Campaign responds to Sepsis-3. Society of Critical Care Medicine website. http://www.survivingsepsis.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/SSC-Statements-Sepsis-Definitions-3-2016.pdf. Published March 1, 2016. Accessed May 11, 2016.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Reducing Inappropriate Acid Suppressives

Prior studies have found that up to 70% of acid‐suppressive medication (ASM) use in the hospital is not indicated, most commonly for stress ulcer prophylaxis in patients outside of the intensive care unit (ICU).[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] Accordingly, reducing inappropriate use of ASM for stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients is 1 of the 5 opportunities for improved healthcare value identified by the Society of Hospital Medicine as part of the American Board of Internal Medicine's Choosing Wisely campaign.[8]

We designed and tested a computerized clinical decision support (CDS) intervention with the goal of reducing use of ASM for stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients outside the ICU at an academic medical center.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a quasiexperimental study using an interrupted time series to analyze data collected prospectively during clinical care before and after implementation of our intervention. The study was deemed a quality improvement initiative by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations/Institutional Review Board.

Patients and Setting

All admissions >18 years of age to a 649‐bed academic medical center in Boston, Massachusetts from September 12, 2011 through July 3, 2012 were included. The medical center consists of an East and West Campus, located across the street from each other. Care for both critically ill and noncritically ill medical and surgical patients occurs on both campuses. Differences include greater proportions of patients with gastrointestinal and oncologic conditions on the East Campus, and renal and cardiac conditions on the West Campus. Additionally, labor and delivery occurs exclusively on the East Campus, and the density of ICU beds is greater on the West Campus. Both campuses utilize a computer‐based provider order entry (POE) system.

Intervention

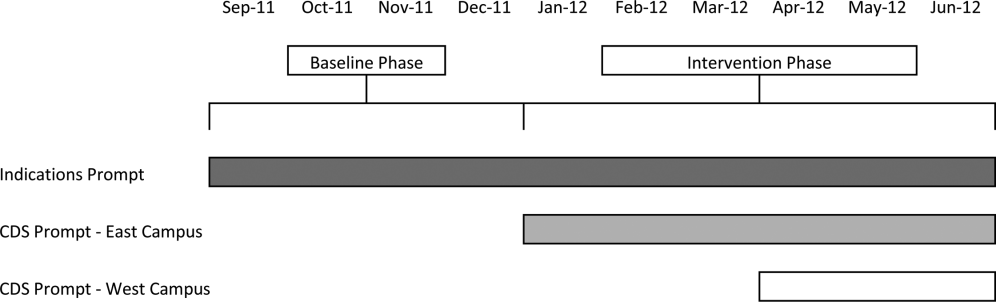

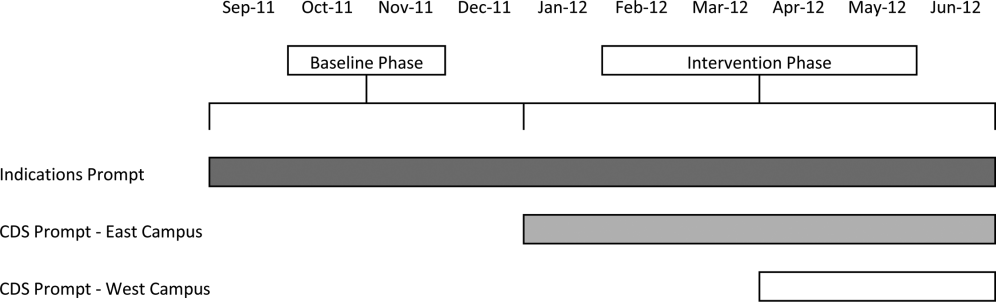

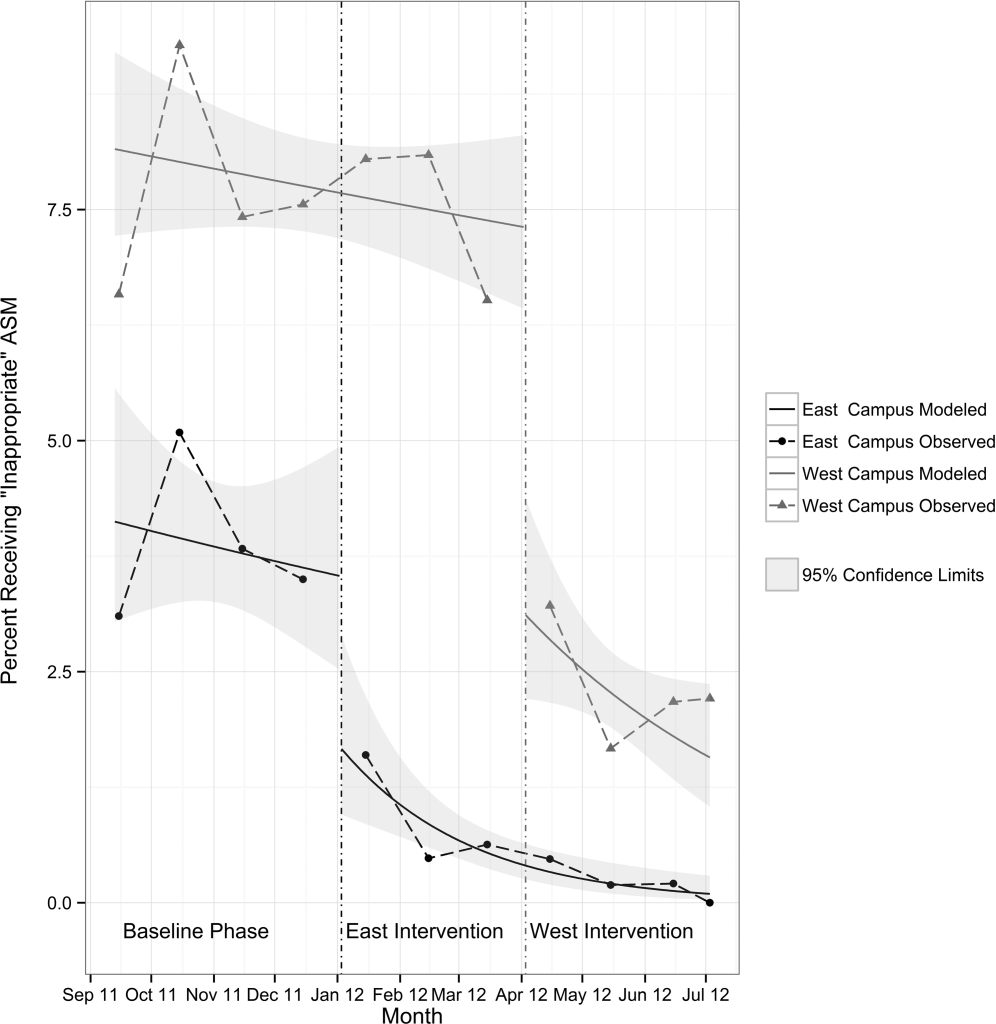

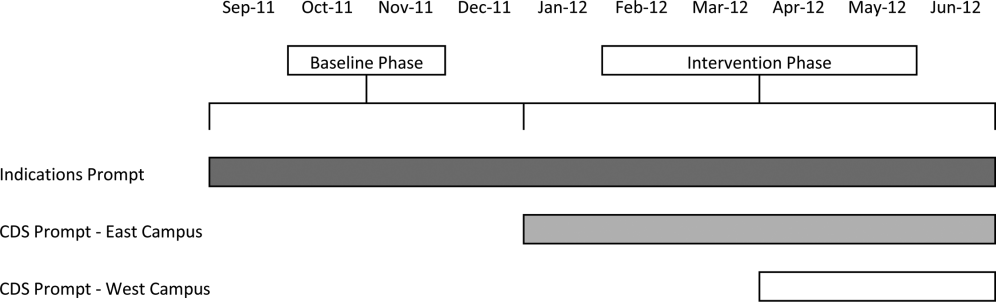

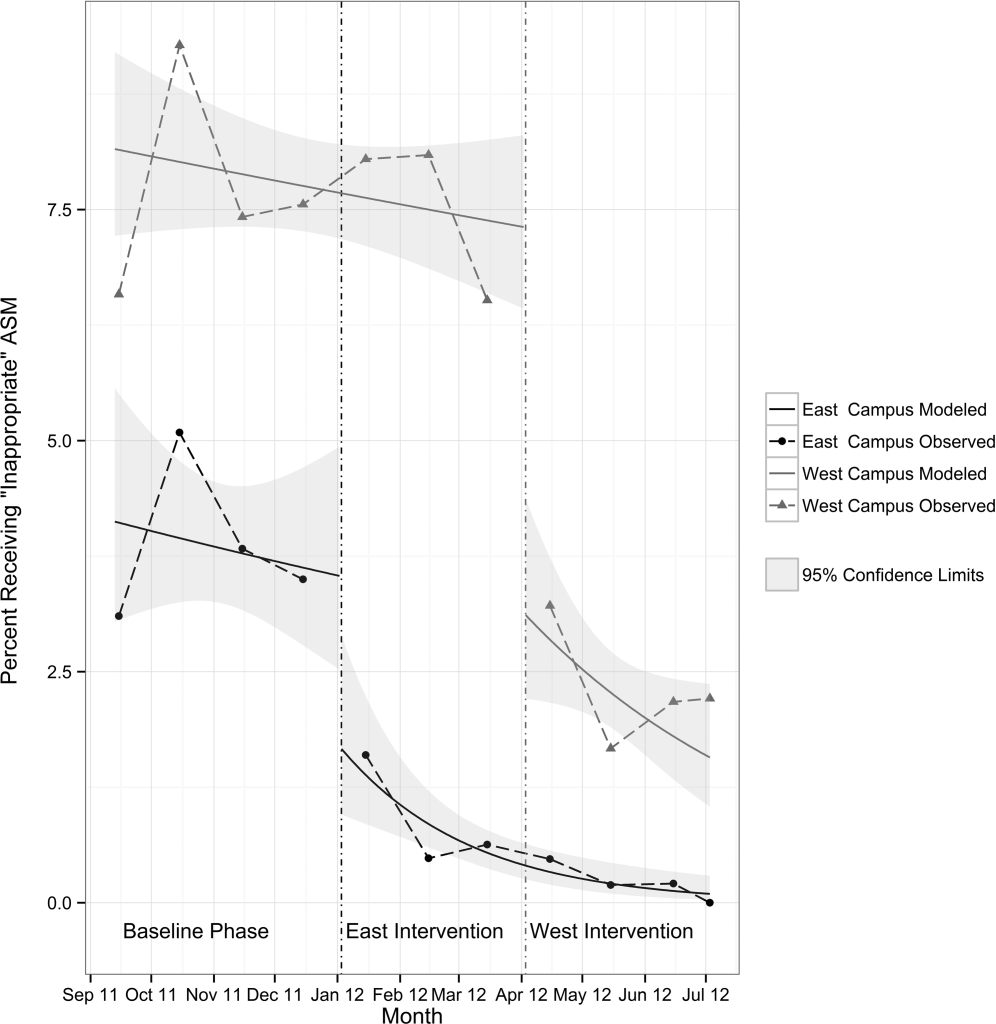

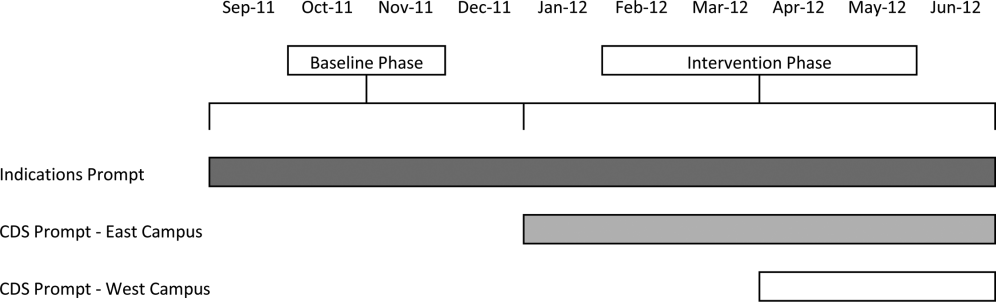

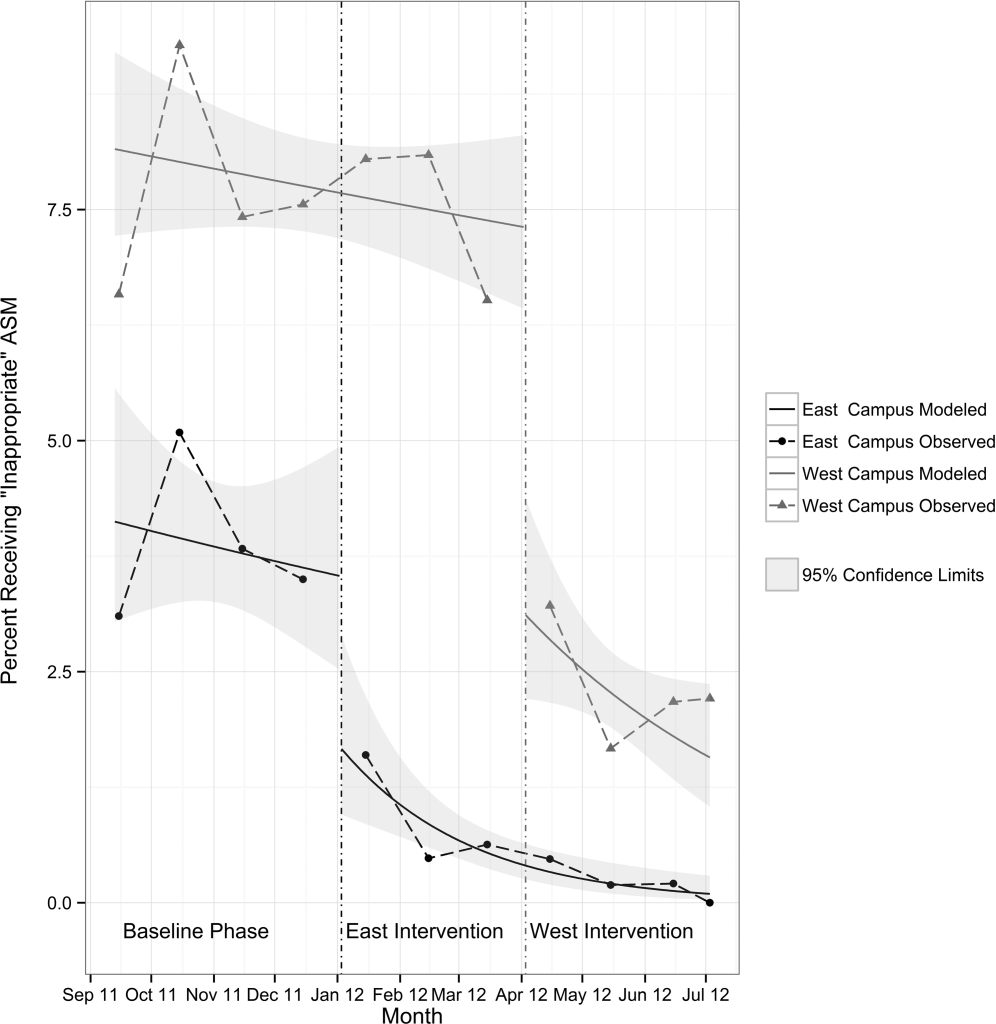

Our study was implemented in 2 phases (Figure 1).

Baseline Phase

The purpose of the first phase was to obtain baseline data on ASM use prior to implementing our CDS tool designed to influence prescribing. During this baseline phase, a computerized prompt was activated through our POE system whenever a clinician initiated an order for ASM (histamine 2 receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors), asking the clinician to select the reason/reasons for the order based on the following predefined response options: (1) active/recent upper gastrointestinal bleed, (2) continuing preadmission medication, (3) Helicobacter pylori treatment, (4) prophylaxis in patient on medications that increase bleeding risk, (5) stress ulcer prophylaxis, (6) suspected/known peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, esophagitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and (7) other, with a free‐text box to input the indication. This indications prompt was rolled out to the entire medical center on September 12, 2011 and remained active for the duration of the study period.

Intervention Phase

In the second phase of the study, if a clinician selected stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only indication for ordering ASM, a CDS prompt alerted the clinician that Stress ulcer prophylaxis is not recommended for patients outside of the intensive care unit (ASHP Therapeutic Guidelines on Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis. Am J Health‐Syst Pharm. 1999, 56:347‐79). The clinician could then select either, For use in ICUOrder Medication, Choose Other Indication, or Cancel Order. This CDS prompt was rolled out in a staggered manner to the East Campus on January 3, 2012, followed by the West Campus on April 3, 2012.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the rate of ASM use with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication in a patient located outside of the ICU. We confirmed patient location in the 24 hours after the order was placed. Secondary outcomes were rates of overall ASM use, defined via pharmacy charges, and rates of use on discharge.

Statistical Analysis

To assure stable measurement of trends, we studied at least 3 months before and after the intervention on each campus. We used the Fisher exact test to compare the rates of our primary and secondary outcomes before and after the intervention, stratified by campus. For our primary outcomeat least 1 ASM order with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication during hospitalizationwe developed a logistic regression model with a generalized estimating equation and exchangeable working correlation structure to control for admission characteristics (Table 1) and repeated admissions. Using a term for the interaction between time and the intervention, this model allowed us to assess changes in level and trend for the odds of a patient receiving at least 1 ASM order with stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only indication before, compared to after the intervention, stratified by campus. We used a 2‐sided type I error of <0.05 to indicate statistical significance.

| Study Phase | Campus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | West | |||

| Baseline, n=3,747 | Intervention, n=6,191 | Baseline, n=11,177 | Intervention, n=5,285 | |

| ||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 48.1 (18.5) | 47.7 (18.2) | 61.0 (18.0) | 60.3 (18.1) |

| Gender, no. (%) | ||||

| Female | 2744 (73.2%) | 4542 (73.4%) | 5551 (49.7%) | 2653 (50.2%) |

| Male | 1003 (26.8%) | 1649 (26.6%) | 5626 (50.3%) | 2632 (49.8%) |

| Race, no. (%) | ||||

| Asian | 281 (7.5%) | 516 (8.3%) | 302 (2.7%) | 156 (3%) |

| Black | 424 (11.3%) | 667 (10.8%) | 1426 (12.8%) | 685 (13%) |

| Hispanic | 224 (6%) | 380 (6.1%) | 619 (5.5%) | 282 (5.3%) |

| Other | 378 (10.1%) | 738 (11.9%) | 776 (6.9%) | 396 (7.5%) |

| White | 2440 (65.1%) | 3890 (62.8%) | 8054 (72%) | 3766 (71.3%) |

| Charlson score, mean (SD) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.7 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.4) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding, no. (%)* | 49 (1.3%) | 99 (1.6%) | 385 (3.4%) | 149 (2.8%) |

| Other medication exposures, no. (%) | ||||

| Therapeutic anticoagulant | 218 (5.8%) | 409 (6.6%) | 2242 (20.1%) | 1022 (19.3%) |

| Prophylactic anticoagulant | 1081 (28.8%) | 1682 (27.2%) | 5999 (53.7%) | 2892 (54.7%) |

| NSAID | 1899 (50.7%) | 3141 (50.7%) | 1248 (11.2%) | 575 (10.9%) |

| Antiplatelet | 313 (8.4%) | 585 (9.4%) | 4543 (40.6%) | 2071 (39.2%) |

| Admitting department, no. (%) | ||||

| Surgery | 2507 (66.9%) | 4146 (67%) | 3255 (29.1%) | 1578 (29.9%) |

| Nonsurgery | 1240 (33.1%) | 2045 (33%) | 7922 (70.9%) | 3707 (70.1%) |

| Any ICU Stay, no. (%) | 217 (5.8%) | 383 (6.2%) | 2786 (24.9%) | 1252 (23.7%) |

RESULTS

There were 26,400 adult admissions during the study period, and 22,330 discrete orders for ASM. Overall, 12,056 (46%) admissions had at least 1 charge for ASM. Admission characteristics were similar before and after the intervention on each campus (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the indications chosen each time ASM was ordered, stratified by campus and study phase. Although selection of stress ulcer prophylaxis decreased on both campuses during the intervention phase, selection of continuing preadmission medication increased.

| Study Phase | Campus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | West | |||

| Baseline, n=2,062 | Intervention, n=3,243 | Baseline, n=12,038 | Intervention, n=4,987 | |

| ||||

| Indication* | ||||

| Continuing preadmission medication | 910 (44.1%) | 1695 (52.3%) | 5597 (46.5%) | 2802 (56.2%) |

| PUD, gastritis, esophagitis, GERD | 440 (21.3%) | 797 (24.6%) | 1303 (10.8%) | 582 (11.7%) |

| Stress ulcer prophylaxis | 298 (14.4%) | 100 (3.1%) | 2659 (22.1%) | 681 (13.7%) |

| Prophylaxis in patient on medications that increase bleeding risk | 226 (11.0%) | 259 (8.0%) | 965 (8.0%) | 411 (8.2%) |

| Active/recent gastrointestinal bleed | 154 (7.5%) | 321 (9.9%) | 1450 (12.0%) | 515 (10.3) |

| Helicobacter pylori treatment | 6 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) | 43 (0.4%) | 21 (0.4%) |

| Other | 111 (5.4%) | 156 (4.8%) | 384 (3.2%) | 186 (3.7%) |

Table 3 shows the unadjusted comparison of outcomes between baseline and intervention phases on each campus. Use of ASM with stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only indication decreased during the intervention phase on both campuses. There was a nonsignificant reduction in overall rates of use on both campuses, and use on discharge was unchanged. Figure 2 demonstrates the unadjusted and modeled monthly rates of admissions with at least 1 ASM order with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication, stratified by campus. After adjusting for the admission characteristics in Table 1, during the intervention phase on both campuses there was a significant immediate reduction in the odds of receiving an ASM with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication (East Campus odds ratio [OR]: 0.36, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.180.71; West Campus OR: 0.41, 95% CI: 0.280.60), and a significant change in trend compared to the baseline phase (East Campus 1.5% daily decrease in odds of receiving ASM solely for stress ulcer prophylaxis, P=0.002; West Campus 0.9% daily decrease in odds of receiving ASM solely for stress ulcer prophylaxis, P=0.02).

| Study Phase | Campus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | West | |||||

| Baseline, n=3,747 | Intervention, n=6,191 | P Value* | Baseline, n=11,177 | Intervention, n=5,285 | P Value* | |

| ||||||

| Outcome | ||||||

| Any inappropriate acid‐suppressive exposure | 4.0% | 0.6% | <0.001 | 7.7% | 2.2% | <0.001 |

| Any acid‐suppressive exposure | 33.1% | 31.8% | 0.16 | 54.5% | 52.9% | 0.05 |

| Discharged on acid‐suppressive medication | 18.9% | 19.6% | 0.40 | 34.7% | 34.7% | 0.95 |

DISCUSSION

In this single‐center study, we found that a computerized CDS intervention resulted in a significant reduction in use of ASM for the sole purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis in patients outside the ICU, a nonsignificant reduction in overall use, and no change in use on discharge. We found low rates of use for the isolated purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis even before the intervention, and continuing preadmission medication was the most commonly selected indication throughout the study.

Although overall rates of ASM use declined after the intervention, the change was not statistically significant, and was not of the same magnitude as the decline in rates of use for the purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis. This suggests that our intervention, in part, led to substitution of 1 indication for another. The indication that increased the most after rollout on both campuses was continuing preadmission medication. There are at least 2 possibilities for this finding: (1) the intervention prompted physicians to more accurately record the indication, or (2) physicians falsified the indication in order to execute the order. To explore these possibilities, we reviewed the charts of a random sample of 100 admissions during each of the baseline and intervention phases where continuing preadmission medication was selected as an indication for an ASM order. We found that 6/100 orders in the baseline phase and 7/100 orders in the intervention phase incorrectly indicated that the patient was on ASM prior to admission (P=0.77). This suggests that scenario 1 above is the more likely explanation for the increased use of this indication, and that the intervention, in part, simply unmasked the true rate of use at our medical center for the isolated purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis.

These findings have implications for others attempting to use computerized CDS to better understand physician prescribing. They suggest that information collected through computer‐based interaction with clinicians at the point of care may not always be accurate or complete. As institutions increasingly use similar interventions to drive behavior, information obtained from such interaction should be validated, and when possible, patient outcomes should be measured.

Our findings suggest that rates of ASM use for the purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis in the hospital may have declined over the last decade. Studies demonstrating that up to 70% of inpatient use of ASM was inappropriate were conducted 5 to 10 years ago.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] Since then, studies have demonstrated risk of nosocomial infections in patients on ASM.[9, 10, 11] It is possible that the low rate of use for stress ulcer prophylaxis in our study is attributable to awareness of the risks of these medications, and limited our ability to detect differences in overall use. It is also possible, however, that a portion of the admissions with continuation of preadmission medication as the indication were started on these medications during a prior hospitalization. Thus, some portion of preadmission use is likely to represent failed medication reconciliation during a prior discharge. In this context, hospitalization may serve as an opportunity to evaluate the indication for ASM use even when these medications show up as preadmission medications.

There are additional limitations. First, the single‐center nature limits generalizability. Second, the first phase of our study, designed to obtain baseline data on ASM use, may have led to changes in prescribing prior to implementation of our CDS tool. Additionally, we did not validate the accuracy of each of the chosen indications, or the site of initial prescription in the case of preadmission exposure. Last, our study was not powered to investigate changes in rates of nosocomial gastrointestinal bleeding or nosocomial pneumonia owing to the infrequent nature of these complications.

In conclusion, we designed a simple computerized CDS intervention that was associated with a reduction in ASM use for stress ulcer prophylaxis in patients outside the ICU, a nonsignificant reduction in overall use, and no change in use on discharge. The majority of inpatient use represented continuation of preadmission medication, suggesting that interventions to improve the appropriateness of ASM prescribing should span the continuum of care. Future studies should investigate whether it is worthwhile and appropriate to reevaluate continued use of preadmission ASM during an inpatient stay.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Joshua Guthermann, MBA, and Jane Hui Chen Lim, MBA, for their assistance in the early phases of data analysis, and Long H. Ngo, PhD, for his statistical consultation.

Disclosures: Dr. Herzig was funded by a Young Clinician Research Award from the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology, a nonprofit consortium of Boston teaching hospitals and universities, and grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Marcantonio was funded by grant number K24AG035075 from the National Institute on Aging. The funding organizations had no involvement in any aspect of the study, including design, conduct, and reporting of the study. Dr. Herzig had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Herzig and Marcantonio were responsible for the study concept and design. Drs. Herzig, Feinbloom, Howell, and Ms. Adra and Mr. Afonso were responsible for the acquisition of data. Drs. Herzig, Howell, Marcantonio, and Mr. Guess were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data. Dr. Herzig drafted the manuscript. All of the authors participated in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Drs. Herzig and Marcantonio were responsible for study supervision. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , . Stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients not in intensive care units. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(13):1396–1400.

- , . Magnitude and economic impact of inappropriate use of stress ulcer prophylaxis in non‐ICU hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2200–2205.

- , . Stress‐ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):86–92.

- , , , et al. Hospital use of acid‐suppressive medications and its fall‐out on prescribing in general practice: a 1‐month survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17(12):1503–1506.

- , , , , , . Inadequate use of acid‐suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients and its implications for general practice. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(12):2307–2311.

- , . Brief report: reducing inappropriate usage of stress ulcer prophylaxis among internal medicine residents. A practice‐based educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):498–500.

- , , . Inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylactic therapy after discharge. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(10):1611–1616.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486–492.

- , , , , . Risk of Clostridium difficile diarrhea among hospital inpatients prescribed proton pump inhibitors: cohort and case‐control studies. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):33–38.

- , , , et al. Iatrogenic gastric acid suppression and the risk of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(9):784–790.

- , , , . Acid‐suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital‐acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2009;301(20):2120–2128.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Clinical classifications software (CCS) for ICD‐9‐CM. December 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed June 18, 2014.

Prior studies have found that up to 70% of acid‐suppressive medication (ASM) use in the hospital is not indicated, most commonly for stress ulcer prophylaxis in patients outside of the intensive care unit (ICU).[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] Accordingly, reducing inappropriate use of ASM for stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients is 1 of the 5 opportunities for improved healthcare value identified by the Society of Hospital Medicine as part of the American Board of Internal Medicine's Choosing Wisely campaign.[8]

We designed and tested a computerized clinical decision support (CDS) intervention with the goal of reducing use of ASM for stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients outside the ICU at an academic medical center.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a quasiexperimental study using an interrupted time series to analyze data collected prospectively during clinical care before and after implementation of our intervention. The study was deemed a quality improvement initiative by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations/Institutional Review Board.

Patients and Setting

All admissions >18 years of age to a 649‐bed academic medical center in Boston, Massachusetts from September 12, 2011 through July 3, 2012 were included. The medical center consists of an East and West Campus, located across the street from each other. Care for both critically ill and noncritically ill medical and surgical patients occurs on both campuses. Differences include greater proportions of patients with gastrointestinal and oncologic conditions on the East Campus, and renal and cardiac conditions on the West Campus. Additionally, labor and delivery occurs exclusively on the East Campus, and the density of ICU beds is greater on the West Campus. Both campuses utilize a computer‐based provider order entry (POE) system.

Intervention

Our study was implemented in 2 phases (Figure 1).

Baseline Phase

The purpose of the first phase was to obtain baseline data on ASM use prior to implementing our CDS tool designed to influence prescribing. During this baseline phase, a computerized prompt was activated through our POE system whenever a clinician initiated an order for ASM (histamine 2 receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors), asking the clinician to select the reason/reasons for the order based on the following predefined response options: (1) active/recent upper gastrointestinal bleed, (2) continuing preadmission medication, (3) Helicobacter pylori treatment, (4) prophylaxis in patient on medications that increase bleeding risk, (5) stress ulcer prophylaxis, (6) suspected/known peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, esophagitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and (7) other, with a free‐text box to input the indication. This indications prompt was rolled out to the entire medical center on September 12, 2011 and remained active for the duration of the study period.

Intervention Phase

In the second phase of the study, if a clinician selected stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only indication for ordering ASM, a CDS prompt alerted the clinician that Stress ulcer prophylaxis is not recommended for patients outside of the intensive care unit (ASHP Therapeutic Guidelines on Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis. Am J Health‐Syst Pharm. 1999, 56:347‐79). The clinician could then select either, For use in ICUOrder Medication, Choose Other Indication, or Cancel Order. This CDS prompt was rolled out in a staggered manner to the East Campus on January 3, 2012, followed by the West Campus on April 3, 2012.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the rate of ASM use with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication in a patient located outside of the ICU. We confirmed patient location in the 24 hours after the order was placed. Secondary outcomes were rates of overall ASM use, defined via pharmacy charges, and rates of use on discharge.

Statistical Analysis

To assure stable measurement of trends, we studied at least 3 months before and after the intervention on each campus. We used the Fisher exact test to compare the rates of our primary and secondary outcomes before and after the intervention, stratified by campus. For our primary outcomeat least 1 ASM order with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication during hospitalizationwe developed a logistic regression model with a generalized estimating equation and exchangeable working correlation structure to control for admission characteristics (Table 1) and repeated admissions. Using a term for the interaction between time and the intervention, this model allowed us to assess changes in level and trend for the odds of a patient receiving at least 1 ASM order with stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only indication before, compared to after the intervention, stratified by campus. We used a 2‐sided type I error of <0.05 to indicate statistical significance.

| Study Phase | Campus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | West | |||

| Baseline, n=3,747 | Intervention, n=6,191 | Baseline, n=11,177 | Intervention, n=5,285 | |

| ||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 48.1 (18.5) | 47.7 (18.2) | 61.0 (18.0) | 60.3 (18.1) |

| Gender, no. (%) | ||||

| Female | 2744 (73.2%) | 4542 (73.4%) | 5551 (49.7%) | 2653 (50.2%) |

| Male | 1003 (26.8%) | 1649 (26.6%) | 5626 (50.3%) | 2632 (49.8%) |

| Race, no. (%) | ||||

| Asian | 281 (7.5%) | 516 (8.3%) | 302 (2.7%) | 156 (3%) |

| Black | 424 (11.3%) | 667 (10.8%) | 1426 (12.8%) | 685 (13%) |

| Hispanic | 224 (6%) | 380 (6.1%) | 619 (5.5%) | 282 (5.3%) |

| Other | 378 (10.1%) | 738 (11.9%) | 776 (6.9%) | 396 (7.5%) |

| White | 2440 (65.1%) | 3890 (62.8%) | 8054 (72%) | 3766 (71.3%) |

| Charlson score, mean (SD) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.7 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.4) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding, no. (%)* | 49 (1.3%) | 99 (1.6%) | 385 (3.4%) | 149 (2.8%) |

| Other medication exposures, no. (%) | ||||

| Therapeutic anticoagulant | 218 (5.8%) | 409 (6.6%) | 2242 (20.1%) | 1022 (19.3%) |

| Prophylactic anticoagulant | 1081 (28.8%) | 1682 (27.2%) | 5999 (53.7%) | 2892 (54.7%) |

| NSAID | 1899 (50.7%) | 3141 (50.7%) | 1248 (11.2%) | 575 (10.9%) |

| Antiplatelet | 313 (8.4%) | 585 (9.4%) | 4543 (40.6%) | 2071 (39.2%) |

| Admitting department, no. (%) | ||||

| Surgery | 2507 (66.9%) | 4146 (67%) | 3255 (29.1%) | 1578 (29.9%) |

| Nonsurgery | 1240 (33.1%) | 2045 (33%) | 7922 (70.9%) | 3707 (70.1%) |

| Any ICU Stay, no. (%) | 217 (5.8%) | 383 (6.2%) | 2786 (24.9%) | 1252 (23.7%) |

RESULTS

There were 26,400 adult admissions during the study period, and 22,330 discrete orders for ASM. Overall, 12,056 (46%) admissions had at least 1 charge for ASM. Admission characteristics were similar before and after the intervention on each campus (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the indications chosen each time ASM was ordered, stratified by campus and study phase. Although selection of stress ulcer prophylaxis decreased on both campuses during the intervention phase, selection of continuing preadmission medication increased.

| Study Phase | Campus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | West | |||

| Baseline, n=2,062 | Intervention, n=3,243 | Baseline, n=12,038 | Intervention, n=4,987 | |

| ||||

| Indication* | ||||

| Continuing preadmission medication | 910 (44.1%) | 1695 (52.3%) | 5597 (46.5%) | 2802 (56.2%) |

| PUD, gastritis, esophagitis, GERD | 440 (21.3%) | 797 (24.6%) | 1303 (10.8%) | 582 (11.7%) |

| Stress ulcer prophylaxis | 298 (14.4%) | 100 (3.1%) | 2659 (22.1%) | 681 (13.7%) |

| Prophylaxis in patient on medications that increase bleeding risk | 226 (11.0%) | 259 (8.0%) | 965 (8.0%) | 411 (8.2%) |

| Active/recent gastrointestinal bleed | 154 (7.5%) | 321 (9.9%) | 1450 (12.0%) | 515 (10.3) |

| Helicobacter pylori treatment | 6 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) | 43 (0.4%) | 21 (0.4%) |

| Other | 111 (5.4%) | 156 (4.8%) | 384 (3.2%) | 186 (3.7%) |

Table 3 shows the unadjusted comparison of outcomes between baseline and intervention phases on each campus. Use of ASM with stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only indication decreased during the intervention phase on both campuses. There was a nonsignificant reduction in overall rates of use on both campuses, and use on discharge was unchanged. Figure 2 demonstrates the unadjusted and modeled monthly rates of admissions with at least 1 ASM order with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication, stratified by campus. After adjusting for the admission characteristics in Table 1, during the intervention phase on both campuses there was a significant immediate reduction in the odds of receiving an ASM with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication (East Campus odds ratio [OR]: 0.36, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.180.71; West Campus OR: 0.41, 95% CI: 0.280.60), and a significant change in trend compared to the baseline phase (East Campus 1.5% daily decrease in odds of receiving ASM solely for stress ulcer prophylaxis, P=0.002; West Campus 0.9% daily decrease in odds of receiving ASM solely for stress ulcer prophylaxis, P=0.02).

| Study Phase | Campus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | West | |||||

| Baseline, n=3,747 | Intervention, n=6,191 | P Value* | Baseline, n=11,177 | Intervention, n=5,285 | P Value* | |

| ||||||

| Outcome | ||||||

| Any inappropriate acid‐suppressive exposure | 4.0% | 0.6% | <0.001 | 7.7% | 2.2% | <0.001 |

| Any acid‐suppressive exposure | 33.1% | 31.8% | 0.16 | 54.5% | 52.9% | 0.05 |

| Discharged on acid‐suppressive medication | 18.9% | 19.6% | 0.40 | 34.7% | 34.7% | 0.95 |

DISCUSSION

In this single‐center study, we found that a computerized CDS intervention resulted in a significant reduction in use of ASM for the sole purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis in patients outside the ICU, a nonsignificant reduction in overall use, and no change in use on discharge. We found low rates of use for the isolated purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis even before the intervention, and continuing preadmission medication was the most commonly selected indication throughout the study.

Although overall rates of ASM use declined after the intervention, the change was not statistically significant, and was not of the same magnitude as the decline in rates of use for the purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis. This suggests that our intervention, in part, led to substitution of 1 indication for another. The indication that increased the most after rollout on both campuses was continuing preadmission medication. There are at least 2 possibilities for this finding: (1) the intervention prompted physicians to more accurately record the indication, or (2) physicians falsified the indication in order to execute the order. To explore these possibilities, we reviewed the charts of a random sample of 100 admissions during each of the baseline and intervention phases where continuing preadmission medication was selected as an indication for an ASM order. We found that 6/100 orders in the baseline phase and 7/100 orders in the intervention phase incorrectly indicated that the patient was on ASM prior to admission (P=0.77). This suggests that scenario 1 above is the more likely explanation for the increased use of this indication, and that the intervention, in part, simply unmasked the true rate of use at our medical center for the isolated purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis.

These findings have implications for others attempting to use computerized CDS to better understand physician prescribing. They suggest that information collected through computer‐based interaction with clinicians at the point of care may not always be accurate or complete. As institutions increasingly use similar interventions to drive behavior, information obtained from such interaction should be validated, and when possible, patient outcomes should be measured.

Our findings suggest that rates of ASM use for the purpose of stress ulcer prophylaxis in the hospital may have declined over the last decade. Studies demonstrating that up to 70% of inpatient use of ASM was inappropriate were conducted 5 to 10 years ago.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] Since then, studies have demonstrated risk of nosocomial infections in patients on ASM.[9, 10, 11] It is possible that the low rate of use for stress ulcer prophylaxis in our study is attributable to awareness of the risks of these medications, and limited our ability to detect differences in overall use. It is also possible, however, that a portion of the admissions with continuation of preadmission medication as the indication were started on these medications during a prior hospitalization. Thus, some portion of preadmission use is likely to represent failed medication reconciliation during a prior discharge. In this context, hospitalization may serve as an opportunity to evaluate the indication for ASM use even when these medications show up as preadmission medications.

There are additional limitations. First, the single‐center nature limits generalizability. Second, the first phase of our study, designed to obtain baseline data on ASM use, may have led to changes in prescribing prior to implementation of our CDS tool. Additionally, we did not validate the accuracy of each of the chosen indications, or the site of initial prescription in the case of preadmission exposure. Last, our study was not powered to investigate changes in rates of nosocomial gastrointestinal bleeding or nosocomial pneumonia owing to the infrequent nature of these complications.

In conclusion, we designed a simple computerized CDS intervention that was associated with a reduction in ASM use for stress ulcer prophylaxis in patients outside the ICU, a nonsignificant reduction in overall use, and no change in use on discharge. The majority of inpatient use represented continuation of preadmission medication, suggesting that interventions to improve the appropriateness of ASM prescribing should span the continuum of care. Future studies should investigate whether it is worthwhile and appropriate to reevaluate continued use of preadmission ASM during an inpatient stay.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Joshua Guthermann, MBA, and Jane Hui Chen Lim, MBA, for their assistance in the early phases of data analysis, and Long H. Ngo, PhD, for his statistical consultation.

Disclosures: Dr. Herzig was funded by a Young Clinician Research Award from the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology, a nonprofit consortium of Boston teaching hospitals and universities, and grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Marcantonio was funded by grant number K24AG035075 from the National Institute on Aging. The funding organizations had no involvement in any aspect of the study, including design, conduct, and reporting of the study. Dr. Herzig had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Herzig and Marcantonio were responsible for the study concept and design. Drs. Herzig, Feinbloom, Howell, and Ms. Adra and Mr. Afonso were responsible for the acquisition of data. Drs. Herzig, Howell, Marcantonio, and Mr. Guess were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data. Dr. Herzig drafted the manuscript. All of the authors participated in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Drs. Herzig and Marcantonio were responsible for study supervision. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Prior studies have found that up to 70% of acid‐suppressive medication (ASM) use in the hospital is not indicated, most commonly for stress ulcer prophylaxis in patients outside of the intensive care unit (ICU).[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] Accordingly, reducing inappropriate use of ASM for stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients is 1 of the 5 opportunities for improved healthcare value identified by the Society of Hospital Medicine as part of the American Board of Internal Medicine's Choosing Wisely campaign.[8]

We designed and tested a computerized clinical decision support (CDS) intervention with the goal of reducing use of ASM for stress ulcer prophylaxis in hospitalized patients outside the ICU at an academic medical center.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a quasiexperimental study using an interrupted time series to analyze data collected prospectively during clinical care before and after implementation of our intervention. The study was deemed a quality improvement initiative by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations/Institutional Review Board.

Patients and Setting

All admissions >18 years of age to a 649‐bed academic medical center in Boston, Massachusetts from September 12, 2011 through July 3, 2012 were included. The medical center consists of an East and West Campus, located across the street from each other. Care for both critically ill and noncritically ill medical and surgical patients occurs on both campuses. Differences include greater proportions of patients with gastrointestinal and oncologic conditions on the East Campus, and renal and cardiac conditions on the West Campus. Additionally, labor and delivery occurs exclusively on the East Campus, and the density of ICU beds is greater on the West Campus. Both campuses utilize a computer‐based provider order entry (POE) system.

Intervention

Our study was implemented in 2 phases (Figure 1).

Baseline Phase

The purpose of the first phase was to obtain baseline data on ASM use prior to implementing our CDS tool designed to influence prescribing. During this baseline phase, a computerized prompt was activated through our POE system whenever a clinician initiated an order for ASM (histamine 2 receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors), asking the clinician to select the reason/reasons for the order based on the following predefined response options: (1) active/recent upper gastrointestinal bleed, (2) continuing preadmission medication, (3) Helicobacter pylori treatment, (4) prophylaxis in patient on medications that increase bleeding risk, (5) stress ulcer prophylaxis, (6) suspected/known peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, esophagitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and (7) other, with a free‐text box to input the indication. This indications prompt was rolled out to the entire medical center on September 12, 2011 and remained active for the duration of the study period.

Intervention Phase

In the second phase of the study, if a clinician selected stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only indication for ordering ASM, a CDS prompt alerted the clinician that Stress ulcer prophylaxis is not recommended for patients outside of the intensive care unit (ASHP Therapeutic Guidelines on Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis. Am J Health‐Syst Pharm. 1999, 56:347‐79). The clinician could then select either, For use in ICUOrder Medication, Choose Other Indication, or Cancel Order. This CDS prompt was rolled out in a staggered manner to the East Campus on January 3, 2012, followed by the West Campus on April 3, 2012.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the rate of ASM use with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication in a patient located outside of the ICU. We confirmed patient location in the 24 hours after the order was placed. Secondary outcomes were rates of overall ASM use, defined via pharmacy charges, and rates of use on discharge.

Statistical Analysis

To assure stable measurement of trends, we studied at least 3 months before and after the intervention on each campus. We used the Fisher exact test to compare the rates of our primary and secondary outcomes before and after the intervention, stratified by campus. For our primary outcomeat least 1 ASM order with stress ulcer prophylaxis selected as the only indication during hospitalizationwe developed a logistic regression model with a generalized estimating equation and exchangeable working correlation structure to control for admission characteristics (Table 1) and repeated admissions. Using a term for the interaction between time and the intervention, this model allowed us to assess changes in level and trend for the odds of a patient receiving at least 1 ASM order with stress ulcer prophylaxis as the only indication before, compared to after the intervention, stratified by campus. We used a 2‐sided type I error of <0.05 to indicate statistical significance.

| Study Phase | Campus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | West | |||

| Baseline, n=3,747 | Intervention, n=6,191 | Baseline, n=11,177 | Intervention, n=5,285 | |

| ||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 48.1 (18.5) | 47.7 (18.2) | 61.0 (18.0) | 60.3 (18.1) |

| Gender, no. (%) | ||||

| Female | 2744 (73.2%) | 4542 (73.4%) | 5551 (49.7%) | 2653 (50.2%) |

| Male | 1003 (26.8%) | 1649 (26.6%) | 5626 (50.3%) | 2632 (49.8%) |

| Race, no. (%) | ||||

| Asian | 281 (7.5%) | 516 (8.3%) | 302 (2.7%) | 156 (3%) |