User login

What’s the best test for underlying osteomyelitis in patients with diabetic foot ulcers?

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a higher sensitivity and specificity (90% and 79%) than plain radiography (54% and 68%) for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis. MRI performs somewhat better than any of several common tests—probe to bone (PTB), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >70 mm/hr, C-reactive protein (CRP) >14 mg/L, procalcitonin >0.3 ng/mL, and ulcer size >2 cm2—although PTB has the highest specificity of any test and is commonly used together with MRI. No studies have directly compared MRI with a combination of these tests, which may assist in diagnosis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of cohort trials and individual cohort and case control trial).

Experts recommend obtaining plain films when considering diabetic foot ulcers to evaluate for bony abnormalities, soft tissue gas, and foreign body; MRI should be considered in most situations when infection is suspected (SOR: B, evidence-based guidelines).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

One-fifth of patients with diabetes who have foot ulcerations will develop osteomyelitis.1,2 Most cases of diabetic foot osteomyelitis result from the spread of a foot infection to underlying bone.2

MRI has highest sensitivity, probe to bone test is most specific

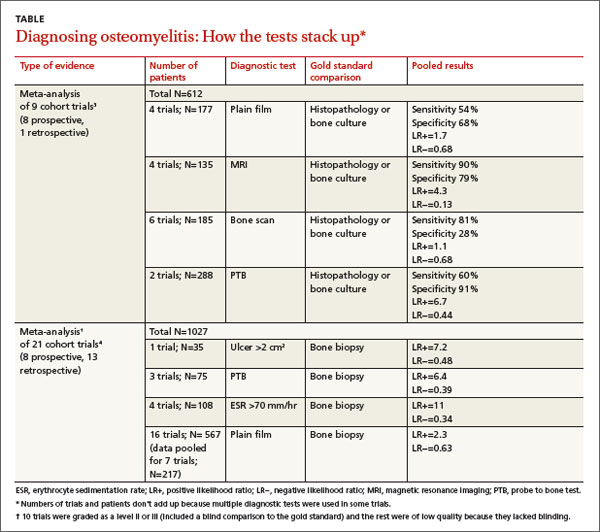

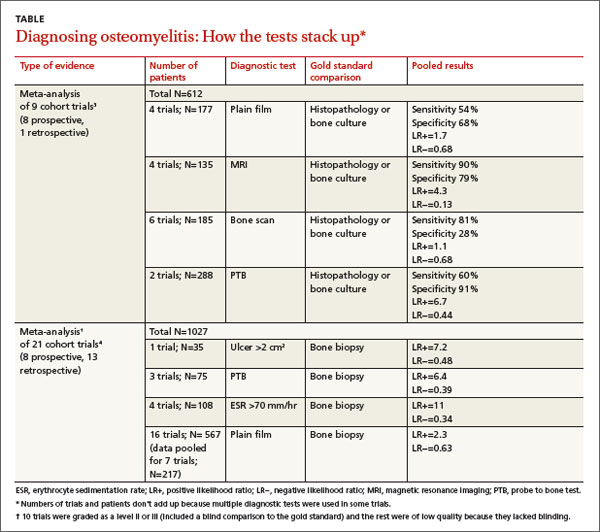

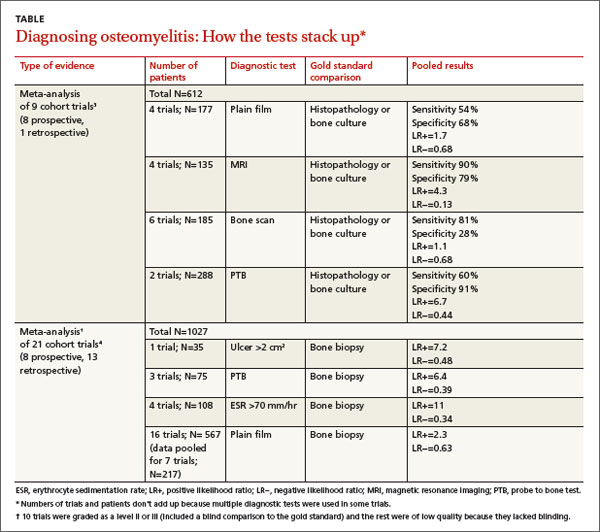

A meta-analysis3 of 9 cohort trials (8 prospective, 1 retrospective) of 612 patients with diabetes and a foot ulcer examined the accuracy of diagnostic methods for osteomyelitis (TABLE3,4). MRI had the highest sensitivity (90%), followed by bone scan (81%). Bone scan was the least specific (28%), however. Plain film radiography had the lowest sensitivity (54%). A PTB test was highly specific (91%) but had moderate sensitivity (60%). (PTB involves inserting a sterile, blunt stainless steel probe into an ulcerated lesion. If the probe comes to a hard stop, considered to be bone, the test is positive.)

A meta-analysis of 21 prospective and retrospective trials with 1027 diabetic patients with foot ulcers or suspected osteomyelitis found that ulcer size >2 cm2, PTB, and ESR >70 mm/hr were helpful in making the diagnosis.4

Combining ESR with ulcer size increases specificity

A prospective trial of 46 diabetic patients hospitalized with a foot infection examined the accuracy of a combination of clinical and laboratory diagnostic features in patients with diabetic foot osteomyelitis that had been diagnosed by MRI or histopathology.5 (Twenty-four patients had osteomyelitis, and 22 didn’t.)

ESR >70 mm/hr had a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 77% (positive likelihood ratio [LR+]=3.6; negative likelihood ratio [LR−]=0.22). Ulcer size >2 cm2 had a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 77% (LR+=3.8; LR−=0.16). Combined, an ESR >70 mm/hr and ulcer size >2cm2 had a slightly better specificity than either finding alone, 82%, but a lower sensitivity of 79% (LR+=4.4; LR−= 0.26).

Serum markers accurately distinguish osteomyelitis from infection

An individual prospective cohort trial of 61 adult patients with diabetes and a foot infection, published after the meta-analysis4 described previously, examined the accuracy of serum markers (ESR, CRP, procalcitonin) for diagnosing osteomyelitis.6 A positive PTB test and imaging study (plain film, MRI, or nuclear scintigraphy) were used as the diagnostic gold standard.

Thirty-four patients had a soft tissue infection and 27 had osteomyelitis. All markers were higher in patients with osteomyelitis than in patients with a soft tissue infection (ESR=76 mm/hr vs 66 mm/hr; P<.001; CRP=25 mg/L vs 8.7 mg/L; P<.001; procalcitonin=2.4 ng/mL vs 0.71 ng/mL; P<.001). The sensitivity and specificity for each marker at its optimum points were: ESR >67 mm/hr (sensitivity 84%; specificity 75%; LR+=3.4; LR−=0.21); CRP >14 mg/L (sensitivity 85%; specificity 83%; LR+=5; LR−=0.18); and procalcitonin >0.3 ng/mL (sensitivity 81%; specificity 71%; LR+=2.8; LR−=0.27).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends performing the PTB test on any diabetic foot infection with an open wound (level of evidence: strong moderate).7 It also recommends performing plain radiography on all patients presenting with a new infection to evaluate for bony abnormalities, soft tissue gas, and foreign bodies (level of evidence: strong moderate).

The IDSA, the American College of Radiology diagnostic imaging expert panel, and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommend using MRI in most clinical scenarios when osteomyelitis is suspected (level of evidence: strong moderate).8,9

1. Gemechu FW, Seemant F, Curley CA. Diabetic foot infections. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:177-184.

2. Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Peters EJ, et al. Probe-to-bone test for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis: reliable or relic? Diabetes Care. 2007;30:270-274.

3. Dinh MT, Abad CL, Safdar N. Diagnostic accuracy of the physical examination and imaging tests for osteomyelitis underlying diabetic foot ulcers: meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:519-527.

4. Butalia S, Palda VA, Sargeant RJ, et al. Does this patient with diabetes have osteomyelitis of the lower extremity? JAMA. 2008;299:806-813.

5. Ertugrul BM, Savk O, Ozturk B, et al. The diagnosis of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: examination findings and laboratory values. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:CR307-CR312.

6. Michail M, Jude E, Liaskos C, et al. The performance of serum inflammatory markers for the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with osteomyelitis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2013;12:94-99.

7. Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, et al. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e132-e173.

8. Schweitzer ME, Daffner RH, Weissman BN, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria on suspected osteomyelitis in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;5:881-886.

9. Tan T, Shaw EJ, Siddiqui F, et al; Guideline Development Group. Inpatient management of diabetic foot problems: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;342:d1280.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a higher sensitivity and specificity (90% and 79%) than plain radiography (54% and 68%) for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis. MRI performs somewhat better than any of several common tests—probe to bone (PTB), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >70 mm/hr, C-reactive protein (CRP) >14 mg/L, procalcitonin >0.3 ng/mL, and ulcer size >2 cm2—although PTB has the highest specificity of any test and is commonly used together with MRI. No studies have directly compared MRI with a combination of these tests, which may assist in diagnosis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of cohort trials and individual cohort and case control trial).

Experts recommend obtaining plain films when considering diabetic foot ulcers to evaluate for bony abnormalities, soft tissue gas, and foreign body; MRI should be considered in most situations when infection is suspected (SOR: B, evidence-based guidelines).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

One-fifth of patients with diabetes who have foot ulcerations will develop osteomyelitis.1,2 Most cases of diabetic foot osteomyelitis result from the spread of a foot infection to underlying bone.2

MRI has highest sensitivity, probe to bone test is most specific

A meta-analysis3 of 9 cohort trials (8 prospective, 1 retrospective) of 612 patients with diabetes and a foot ulcer examined the accuracy of diagnostic methods for osteomyelitis (TABLE3,4). MRI had the highest sensitivity (90%), followed by bone scan (81%). Bone scan was the least specific (28%), however. Plain film radiography had the lowest sensitivity (54%). A PTB test was highly specific (91%) but had moderate sensitivity (60%). (PTB involves inserting a sterile, blunt stainless steel probe into an ulcerated lesion. If the probe comes to a hard stop, considered to be bone, the test is positive.)

A meta-analysis of 21 prospective and retrospective trials with 1027 diabetic patients with foot ulcers or suspected osteomyelitis found that ulcer size >2 cm2, PTB, and ESR >70 mm/hr were helpful in making the diagnosis.4

Combining ESR with ulcer size increases specificity

A prospective trial of 46 diabetic patients hospitalized with a foot infection examined the accuracy of a combination of clinical and laboratory diagnostic features in patients with diabetic foot osteomyelitis that had been diagnosed by MRI or histopathology.5 (Twenty-four patients had osteomyelitis, and 22 didn’t.)

ESR >70 mm/hr had a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 77% (positive likelihood ratio [LR+]=3.6; negative likelihood ratio [LR−]=0.22). Ulcer size >2 cm2 had a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 77% (LR+=3.8; LR−=0.16). Combined, an ESR >70 mm/hr and ulcer size >2cm2 had a slightly better specificity than either finding alone, 82%, but a lower sensitivity of 79% (LR+=4.4; LR−= 0.26).

Serum markers accurately distinguish osteomyelitis from infection

An individual prospective cohort trial of 61 adult patients with diabetes and a foot infection, published after the meta-analysis4 described previously, examined the accuracy of serum markers (ESR, CRP, procalcitonin) for diagnosing osteomyelitis.6 A positive PTB test and imaging study (plain film, MRI, or nuclear scintigraphy) were used as the diagnostic gold standard.

Thirty-four patients had a soft tissue infection and 27 had osteomyelitis. All markers were higher in patients with osteomyelitis than in patients with a soft tissue infection (ESR=76 mm/hr vs 66 mm/hr; P<.001; CRP=25 mg/L vs 8.7 mg/L; P<.001; procalcitonin=2.4 ng/mL vs 0.71 ng/mL; P<.001). The sensitivity and specificity for each marker at its optimum points were: ESR >67 mm/hr (sensitivity 84%; specificity 75%; LR+=3.4; LR−=0.21); CRP >14 mg/L (sensitivity 85%; specificity 83%; LR+=5; LR−=0.18); and procalcitonin >0.3 ng/mL (sensitivity 81%; specificity 71%; LR+=2.8; LR−=0.27).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends performing the PTB test on any diabetic foot infection with an open wound (level of evidence: strong moderate).7 It also recommends performing plain radiography on all patients presenting with a new infection to evaluate for bony abnormalities, soft tissue gas, and foreign bodies (level of evidence: strong moderate).

The IDSA, the American College of Radiology diagnostic imaging expert panel, and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommend using MRI in most clinical scenarios when osteomyelitis is suspected (level of evidence: strong moderate).8,9

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a higher sensitivity and specificity (90% and 79%) than plain radiography (54% and 68%) for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis. MRI performs somewhat better than any of several common tests—probe to bone (PTB), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >70 mm/hr, C-reactive protein (CRP) >14 mg/L, procalcitonin >0.3 ng/mL, and ulcer size >2 cm2—although PTB has the highest specificity of any test and is commonly used together with MRI. No studies have directly compared MRI with a combination of these tests, which may assist in diagnosis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of cohort trials and individual cohort and case control trial).

Experts recommend obtaining plain films when considering diabetic foot ulcers to evaluate for bony abnormalities, soft tissue gas, and foreign body; MRI should be considered in most situations when infection is suspected (SOR: B, evidence-based guidelines).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

One-fifth of patients with diabetes who have foot ulcerations will develop osteomyelitis.1,2 Most cases of diabetic foot osteomyelitis result from the spread of a foot infection to underlying bone.2

MRI has highest sensitivity, probe to bone test is most specific

A meta-analysis3 of 9 cohort trials (8 prospective, 1 retrospective) of 612 patients with diabetes and a foot ulcer examined the accuracy of diagnostic methods for osteomyelitis (TABLE3,4). MRI had the highest sensitivity (90%), followed by bone scan (81%). Bone scan was the least specific (28%), however. Plain film radiography had the lowest sensitivity (54%). A PTB test was highly specific (91%) but had moderate sensitivity (60%). (PTB involves inserting a sterile, blunt stainless steel probe into an ulcerated lesion. If the probe comes to a hard stop, considered to be bone, the test is positive.)

A meta-analysis of 21 prospective and retrospective trials with 1027 diabetic patients with foot ulcers or suspected osteomyelitis found that ulcer size >2 cm2, PTB, and ESR >70 mm/hr were helpful in making the diagnosis.4

Combining ESR with ulcer size increases specificity

A prospective trial of 46 diabetic patients hospitalized with a foot infection examined the accuracy of a combination of clinical and laboratory diagnostic features in patients with diabetic foot osteomyelitis that had been diagnosed by MRI or histopathology.5 (Twenty-four patients had osteomyelitis, and 22 didn’t.)

ESR >70 mm/hr had a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 77% (positive likelihood ratio [LR+]=3.6; negative likelihood ratio [LR−]=0.22). Ulcer size >2 cm2 had a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 77% (LR+=3.8; LR−=0.16). Combined, an ESR >70 mm/hr and ulcer size >2cm2 had a slightly better specificity than either finding alone, 82%, but a lower sensitivity of 79% (LR+=4.4; LR−= 0.26).

Serum markers accurately distinguish osteomyelitis from infection

An individual prospective cohort trial of 61 adult patients with diabetes and a foot infection, published after the meta-analysis4 described previously, examined the accuracy of serum markers (ESR, CRP, procalcitonin) for diagnosing osteomyelitis.6 A positive PTB test and imaging study (plain film, MRI, or nuclear scintigraphy) were used as the diagnostic gold standard.

Thirty-four patients had a soft tissue infection and 27 had osteomyelitis. All markers were higher in patients with osteomyelitis than in patients with a soft tissue infection (ESR=76 mm/hr vs 66 mm/hr; P<.001; CRP=25 mg/L vs 8.7 mg/L; P<.001; procalcitonin=2.4 ng/mL vs 0.71 ng/mL; P<.001). The sensitivity and specificity for each marker at its optimum points were: ESR >67 mm/hr (sensitivity 84%; specificity 75%; LR+=3.4; LR−=0.21); CRP >14 mg/L (sensitivity 85%; specificity 83%; LR+=5; LR−=0.18); and procalcitonin >0.3 ng/mL (sensitivity 81%; specificity 71%; LR+=2.8; LR−=0.27).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends performing the PTB test on any diabetic foot infection with an open wound (level of evidence: strong moderate).7 It also recommends performing plain radiography on all patients presenting with a new infection to evaluate for bony abnormalities, soft tissue gas, and foreign bodies (level of evidence: strong moderate).

The IDSA, the American College of Radiology diagnostic imaging expert panel, and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommend using MRI in most clinical scenarios when osteomyelitis is suspected (level of evidence: strong moderate).8,9

1. Gemechu FW, Seemant F, Curley CA. Diabetic foot infections. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:177-184.

2. Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Peters EJ, et al. Probe-to-bone test for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis: reliable or relic? Diabetes Care. 2007;30:270-274.

3. Dinh MT, Abad CL, Safdar N. Diagnostic accuracy of the physical examination and imaging tests for osteomyelitis underlying diabetic foot ulcers: meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:519-527.

4. Butalia S, Palda VA, Sargeant RJ, et al. Does this patient with diabetes have osteomyelitis of the lower extremity? JAMA. 2008;299:806-813.

5. Ertugrul BM, Savk O, Ozturk B, et al. The diagnosis of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: examination findings and laboratory values. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:CR307-CR312.

6. Michail M, Jude E, Liaskos C, et al. The performance of serum inflammatory markers for the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with osteomyelitis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2013;12:94-99.

7. Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, et al. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e132-e173.

8. Schweitzer ME, Daffner RH, Weissman BN, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria on suspected osteomyelitis in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;5:881-886.

9. Tan T, Shaw EJ, Siddiqui F, et al; Guideline Development Group. Inpatient management of diabetic foot problems: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;342:d1280.

1. Gemechu FW, Seemant F, Curley CA. Diabetic foot infections. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:177-184.

2. Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Peters EJ, et al. Probe-to-bone test for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis: reliable or relic? Diabetes Care. 2007;30:270-274.

3. Dinh MT, Abad CL, Safdar N. Diagnostic accuracy of the physical examination and imaging tests for osteomyelitis underlying diabetic foot ulcers: meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:519-527.

4. Butalia S, Palda VA, Sargeant RJ, et al. Does this patient with diabetes have osteomyelitis of the lower extremity? JAMA. 2008;299:806-813.

5. Ertugrul BM, Savk O, Ozturk B, et al. The diagnosis of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: examination findings and laboratory values. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:CR307-CR312.

6. Michail M, Jude E, Liaskos C, et al. The performance of serum inflammatory markers for the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with osteomyelitis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2013;12:94-99.

7. Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, et al. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e132-e173.

8. Schweitzer ME, Daffner RH, Weissman BN, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria on suspected osteomyelitis in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;5:881-886.

9. Tan T, Shaw EJ, Siddiqui F, et al; Guideline Development Group. Inpatient management of diabetic foot problems: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;342:d1280.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Bilateral hand cramping and weakness • broad fingers • coarse facial features • Dx?

THE CASE

A 37-year-old right-hand dominant woman came to our clinic seeking treatment for bilateral generalized hand cramping and weakness that she had been experiencing for approximately 2 to 3 years. She was dropping objects and had finger locking, yet had no numbness, tingling, or morning stiffness.

Ten months earlier, she had given birth to a healthy 3715 g girl. Our patient’s prenatal glucose tolerance test had been normal. Her pregnancy and delivery had been significant for oligohydramnios, failed post-term (41 weeks 4 days) induction, and emergent low transverse cesarean section due to fetal bradycardia. Since giving birth, our patient had 3 menstrual periods while breastfeeding. She had a copper intrauterine device inserted at her 6-week postpartum visit. She also had 2 truncal acrochordons removed 3 months postpartum. She had no history of neck trauma, overuse injury, or occupational exposures.

Her blood pressure and vital signs were within normal limits. Physical exam was notable for subtly coarse facial features and broad fingers (FIGURE 1).

She had normal wrist and hand joint range of motion; her wrist and hand strengths, including grip strength, were 5 out of 5. Tinel’s sign, Phalen’s maneuver, and Finkelstein’s test were negative.

Her upper extremity neurovascular exams were completely normal. Initial laboratory studies—including a comprehensive metabolic panel—were normal. The only exception was her creatine kinase, which was 265 U/L (normal, 24-195 U/L).

At a follow-up appointment 7 weeks later, we gathered a more detailed history and learned that over the past 2 to 3 years, the patient had noticed that her shoe and ring sizes had been increasing. She also mentioned some mild weight gain following her pregnancy.

Occasionally, she had generalized hand swelling, headaches, and saw floaters, but she denied losing peripheral vision. Additional lab work at this time revealed a fasting growth hormone (GH) level of 27.3 ng/mL (normal, 0.05-8 ng/mL) and an insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) level of 848 ng/mL (normal, 106-368 ng/mL). An anterior pituitary hormone panel and cortisol level were normal. A urine pregnancy test was negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

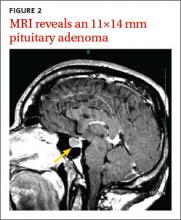

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of our patient’s brain revealed a pituitary adenoma (FIGURE 2). Based on that and the patient’s elevated GH and IGF-1 levels, we diagnosed acromegaly due to a pituitary adenoma.

DISCUSSION

Acromegaly is a rare, progressively disfiguring disease with a prevalence of 40 cases per million people.1 It affects middle-aged adults, with no gender difference.2 In most cases, the cause is a benign pituitary adenoma.1-4

Physical changes include coarse facial features, generalized expansion of the skull, brow protrusion, ocular distension, prognathism, macroglossia, acral overgrowth, and dental malocclusion; these changes typically occur slowly over a long time period.1-5 For example, when we looked at the 3-year-old photo on our patient’s driver’s license, we noticed only subtle changes from her current appearance. Common clinical manifestations include headache, hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, hyperhidrosis, goiter, arthropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, visual disturbances, and acrochordons.1,5

Acromegaly is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, infertility, sleep apnea, arthritis, thyroid tumors, colon adenomas, and carcinoma.1,2,4,5 Due to the insidious progression of acromegaly’s clinical manifestations, diagnosis is delayed for 4 to 10 years, on average.1 The diagnosis of acromegaly is typically based on an elevation of GH and IGF-1 levels.1,5 A brain MRI is essential in the diagnosis of a pituitary adenoma.1

Pregnancy among patients with acromegaly is uncommon. In fact, fewer than 150 cases have been reported in the literature.2,6 In most cases, it appears that pregnancy among patients with acromegaly is safe for mothers and newborns.6,7

The goals of treatment for acromegaly caused by a pituitary adenoma are to remove/ reduce the tumor and its mechanical effects, relieve symptoms, reduce serum GH and IGF-1, and restore pituitary function. Transsphenoidal surgical resection is the preferred treatment for pituitary adenomas.1,2,4 Radiation therapy and pharmacologic treatment may be necessary as adjuncts to surgery or for patients for whom surgery is contraindicated.1,4,5

Pharmacologic management of acromegaly includes dopamine agonists (cabergoline), somatostatin analogues (octreotide, lanreotide), and GH receptor antagonists (pegvisomant).1,3 Patients who receive effective early treatment of acromegaly have a life expectancy similar to that of the general population.1,5

Our patient

Our patient was referred to Neurosurgery and underwent transnasal transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma. Two weeks postop, her GH level had decreased to 0.66 ng/mL and her IGF-1 level was down to 386 ng/mL. Four months later, her GH (2.32 ng/mL) and IGF-1 levels (277 ng/mL) were within normal range and our patient reported improvement in all of her symptoms.

THE TAKEAWAY

Because it may take years for the classical clinical features of acromegaly such as coarse facial features, protruding jaw, and broad fingers to become apparent, diligent history taking is essential to diagnose the condition early. Patients may present with nonspecific and confusing symptoms such as muscle weakness.8 Early nonspecific symptoms and signs in the presence of normal basic laboratory tests should warrant an evaluation of fasting GH and IGF-1. Early treatment with surgery, radiation therapy, or pharmacotherapy may prevent or decrease the intensity of rheumatologic, cardiovascular, respiratory, and metabolic complications of acromegaly.1

1. Scacchi M, Cavagnini F. Acromegaly. Pituitary. 2006;9: 297-303.

2. Hossain B, Drake WM. Acromegaly. Medicine. 2009;37: 407-410.

3. Chan MR, Ziebert M, Maas DL, et al. “My rings won’t fit anymore”. Ectopic growth hormone-secreting tumor. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1766-1767.

4. Lake MG, Krook LS, Cruz SV. Pituitary adenomas: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:319-327.

5. Vilar L, Valenzuela A, Ribeiro-Oliveira A Jr, et al. Multiple facets in the control of acromegaly. Pituitary. 2014;17 suppl 1:S11-S17.

6. Cheng V, Faiman C, Kennedy L, et al. Pregnancy and acromegaly: a review. Pituitary. 2012;15:59-63.

7. Caron P, Broussaud S, Bertherat J, et al. Acromegaly and pregnancy: a retrospective multicenter study of 59 pregnancies in 46 women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4680-4687.

8. Saguil A. Evaluation of the patient with muscle weakness. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1327-1336.

THE CASE

A 37-year-old right-hand dominant woman came to our clinic seeking treatment for bilateral generalized hand cramping and weakness that she had been experiencing for approximately 2 to 3 years. She was dropping objects and had finger locking, yet had no numbness, tingling, or morning stiffness.

Ten months earlier, she had given birth to a healthy 3715 g girl. Our patient’s prenatal glucose tolerance test had been normal. Her pregnancy and delivery had been significant for oligohydramnios, failed post-term (41 weeks 4 days) induction, and emergent low transverse cesarean section due to fetal bradycardia. Since giving birth, our patient had 3 menstrual periods while breastfeeding. She had a copper intrauterine device inserted at her 6-week postpartum visit. She also had 2 truncal acrochordons removed 3 months postpartum. She had no history of neck trauma, overuse injury, or occupational exposures.

Her blood pressure and vital signs were within normal limits. Physical exam was notable for subtly coarse facial features and broad fingers (FIGURE 1).

She had normal wrist and hand joint range of motion; her wrist and hand strengths, including grip strength, were 5 out of 5. Tinel’s sign, Phalen’s maneuver, and Finkelstein’s test were negative.

Her upper extremity neurovascular exams were completely normal. Initial laboratory studies—including a comprehensive metabolic panel—were normal. The only exception was her creatine kinase, which was 265 U/L (normal, 24-195 U/L).

At a follow-up appointment 7 weeks later, we gathered a more detailed history and learned that over the past 2 to 3 years, the patient had noticed that her shoe and ring sizes had been increasing. She also mentioned some mild weight gain following her pregnancy.

Occasionally, she had generalized hand swelling, headaches, and saw floaters, but she denied losing peripheral vision. Additional lab work at this time revealed a fasting growth hormone (GH) level of 27.3 ng/mL (normal, 0.05-8 ng/mL) and an insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) level of 848 ng/mL (normal, 106-368 ng/mL). An anterior pituitary hormone panel and cortisol level were normal. A urine pregnancy test was negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of our patient’s brain revealed a pituitary adenoma (FIGURE 2). Based on that and the patient’s elevated GH and IGF-1 levels, we diagnosed acromegaly due to a pituitary adenoma.

DISCUSSION

Acromegaly is a rare, progressively disfiguring disease with a prevalence of 40 cases per million people.1 It affects middle-aged adults, with no gender difference.2 In most cases, the cause is a benign pituitary adenoma.1-4

Physical changes include coarse facial features, generalized expansion of the skull, brow protrusion, ocular distension, prognathism, macroglossia, acral overgrowth, and dental malocclusion; these changes typically occur slowly over a long time period.1-5 For example, when we looked at the 3-year-old photo on our patient’s driver’s license, we noticed only subtle changes from her current appearance. Common clinical manifestations include headache, hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, hyperhidrosis, goiter, arthropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, visual disturbances, and acrochordons.1,5

Acromegaly is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, infertility, sleep apnea, arthritis, thyroid tumors, colon adenomas, and carcinoma.1,2,4,5 Due to the insidious progression of acromegaly’s clinical manifestations, diagnosis is delayed for 4 to 10 years, on average.1 The diagnosis of acromegaly is typically based on an elevation of GH and IGF-1 levels.1,5 A brain MRI is essential in the diagnosis of a pituitary adenoma.1

Pregnancy among patients with acromegaly is uncommon. In fact, fewer than 150 cases have been reported in the literature.2,6 In most cases, it appears that pregnancy among patients with acromegaly is safe for mothers and newborns.6,7

The goals of treatment for acromegaly caused by a pituitary adenoma are to remove/ reduce the tumor and its mechanical effects, relieve symptoms, reduce serum GH and IGF-1, and restore pituitary function. Transsphenoidal surgical resection is the preferred treatment for pituitary adenomas.1,2,4 Radiation therapy and pharmacologic treatment may be necessary as adjuncts to surgery or for patients for whom surgery is contraindicated.1,4,5

Pharmacologic management of acromegaly includes dopamine agonists (cabergoline), somatostatin analogues (octreotide, lanreotide), and GH receptor antagonists (pegvisomant).1,3 Patients who receive effective early treatment of acromegaly have a life expectancy similar to that of the general population.1,5

Our patient

Our patient was referred to Neurosurgery and underwent transnasal transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma. Two weeks postop, her GH level had decreased to 0.66 ng/mL and her IGF-1 level was down to 386 ng/mL. Four months later, her GH (2.32 ng/mL) and IGF-1 levels (277 ng/mL) were within normal range and our patient reported improvement in all of her symptoms.

THE TAKEAWAY

Because it may take years for the classical clinical features of acromegaly such as coarse facial features, protruding jaw, and broad fingers to become apparent, diligent history taking is essential to diagnose the condition early. Patients may present with nonspecific and confusing symptoms such as muscle weakness.8 Early nonspecific symptoms and signs in the presence of normal basic laboratory tests should warrant an evaluation of fasting GH and IGF-1. Early treatment with surgery, radiation therapy, or pharmacotherapy may prevent or decrease the intensity of rheumatologic, cardiovascular, respiratory, and metabolic complications of acromegaly.1

THE CASE

A 37-year-old right-hand dominant woman came to our clinic seeking treatment for bilateral generalized hand cramping and weakness that she had been experiencing for approximately 2 to 3 years. She was dropping objects and had finger locking, yet had no numbness, tingling, or morning stiffness.

Ten months earlier, she had given birth to a healthy 3715 g girl. Our patient’s prenatal glucose tolerance test had been normal. Her pregnancy and delivery had been significant for oligohydramnios, failed post-term (41 weeks 4 days) induction, and emergent low transverse cesarean section due to fetal bradycardia. Since giving birth, our patient had 3 menstrual periods while breastfeeding. She had a copper intrauterine device inserted at her 6-week postpartum visit. She also had 2 truncal acrochordons removed 3 months postpartum. She had no history of neck trauma, overuse injury, or occupational exposures.

Her blood pressure and vital signs were within normal limits. Physical exam was notable for subtly coarse facial features and broad fingers (FIGURE 1).

She had normal wrist and hand joint range of motion; her wrist and hand strengths, including grip strength, were 5 out of 5. Tinel’s sign, Phalen’s maneuver, and Finkelstein’s test were negative.

Her upper extremity neurovascular exams were completely normal. Initial laboratory studies—including a comprehensive metabolic panel—were normal. The only exception was her creatine kinase, which was 265 U/L (normal, 24-195 U/L).

At a follow-up appointment 7 weeks later, we gathered a more detailed history and learned that over the past 2 to 3 years, the patient had noticed that her shoe and ring sizes had been increasing. She also mentioned some mild weight gain following her pregnancy.

Occasionally, she had generalized hand swelling, headaches, and saw floaters, but she denied losing peripheral vision. Additional lab work at this time revealed a fasting growth hormone (GH) level of 27.3 ng/mL (normal, 0.05-8 ng/mL) and an insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) level of 848 ng/mL (normal, 106-368 ng/mL). An anterior pituitary hormone panel and cortisol level were normal. A urine pregnancy test was negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of our patient’s brain revealed a pituitary adenoma (FIGURE 2). Based on that and the patient’s elevated GH and IGF-1 levels, we diagnosed acromegaly due to a pituitary adenoma.

DISCUSSION

Acromegaly is a rare, progressively disfiguring disease with a prevalence of 40 cases per million people.1 It affects middle-aged adults, with no gender difference.2 In most cases, the cause is a benign pituitary adenoma.1-4

Physical changes include coarse facial features, generalized expansion of the skull, brow protrusion, ocular distension, prognathism, macroglossia, acral overgrowth, and dental malocclusion; these changes typically occur slowly over a long time period.1-5 For example, when we looked at the 3-year-old photo on our patient’s driver’s license, we noticed only subtle changes from her current appearance. Common clinical manifestations include headache, hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, hyperhidrosis, goiter, arthropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, visual disturbances, and acrochordons.1,5

Acromegaly is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, infertility, sleep apnea, arthritis, thyroid tumors, colon adenomas, and carcinoma.1,2,4,5 Due to the insidious progression of acromegaly’s clinical manifestations, diagnosis is delayed for 4 to 10 years, on average.1 The diagnosis of acromegaly is typically based on an elevation of GH and IGF-1 levels.1,5 A brain MRI is essential in the diagnosis of a pituitary adenoma.1

Pregnancy among patients with acromegaly is uncommon. In fact, fewer than 150 cases have been reported in the literature.2,6 In most cases, it appears that pregnancy among patients with acromegaly is safe for mothers and newborns.6,7

The goals of treatment for acromegaly caused by a pituitary adenoma are to remove/ reduce the tumor and its mechanical effects, relieve symptoms, reduce serum GH and IGF-1, and restore pituitary function. Transsphenoidal surgical resection is the preferred treatment for pituitary adenomas.1,2,4 Radiation therapy and pharmacologic treatment may be necessary as adjuncts to surgery or for patients for whom surgery is contraindicated.1,4,5

Pharmacologic management of acromegaly includes dopamine agonists (cabergoline), somatostatin analogues (octreotide, lanreotide), and GH receptor antagonists (pegvisomant).1,3 Patients who receive effective early treatment of acromegaly have a life expectancy similar to that of the general population.1,5

Our patient

Our patient was referred to Neurosurgery and underwent transnasal transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma. Two weeks postop, her GH level had decreased to 0.66 ng/mL and her IGF-1 level was down to 386 ng/mL. Four months later, her GH (2.32 ng/mL) and IGF-1 levels (277 ng/mL) were within normal range and our patient reported improvement in all of her symptoms.

THE TAKEAWAY

Because it may take years for the classical clinical features of acromegaly such as coarse facial features, protruding jaw, and broad fingers to become apparent, diligent history taking is essential to diagnose the condition early. Patients may present with nonspecific and confusing symptoms such as muscle weakness.8 Early nonspecific symptoms and signs in the presence of normal basic laboratory tests should warrant an evaluation of fasting GH and IGF-1. Early treatment with surgery, radiation therapy, or pharmacotherapy may prevent or decrease the intensity of rheumatologic, cardiovascular, respiratory, and metabolic complications of acromegaly.1

1. Scacchi M, Cavagnini F. Acromegaly. Pituitary. 2006;9: 297-303.

2. Hossain B, Drake WM. Acromegaly. Medicine. 2009;37: 407-410.

3. Chan MR, Ziebert M, Maas DL, et al. “My rings won’t fit anymore”. Ectopic growth hormone-secreting tumor. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1766-1767.

4. Lake MG, Krook LS, Cruz SV. Pituitary adenomas: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:319-327.

5. Vilar L, Valenzuela A, Ribeiro-Oliveira A Jr, et al. Multiple facets in the control of acromegaly. Pituitary. 2014;17 suppl 1:S11-S17.

6. Cheng V, Faiman C, Kennedy L, et al. Pregnancy and acromegaly: a review. Pituitary. 2012;15:59-63.

7. Caron P, Broussaud S, Bertherat J, et al. Acromegaly and pregnancy: a retrospective multicenter study of 59 pregnancies in 46 women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4680-4687.

8. Saguil A. Evaluation of the patient with muscle weakness. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1327-1336.

1. Scacchi M, Cavagnini F. Acromegaly. Pituitary. 2006;9: 297-303.

2. Hossain B, Drake WM. Acromegaly. Medicine. 2009;37: 407-410.

3. Chan MR, Ziebert M, Maas DL, et al. “My rings won’t fit anymore”. Ectopic growth hormone-secreting tumor. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1766-1767.

4. Lake MG, Krook LS, Cruz SV. Pituitary adenomas: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:319-327.

5. Vilar L, Valenzuela A, Ribeiro-Oliveira A Jr, et al. Multiple facets in the control of acromegaly. Pituitary. 2014;17 suppl 1:S11-S17.

6. Cheng V, Faiman C, Kennedy L, et al. Pregnancy and acromegaly: a review. Pituitary. 2012;15:59-63.

7. Caron P, Broussaud S, Bertherat J, et al. Acromegaly and pregnancy: a retrospective multicenter study of 59 pregnancies in 46 women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4680-4687.

8. Saguil A. Evaluation of the patient with muscle weakness. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1327-1336.

4 pregnant women with an unusual finding at delivery

THE CASES

CASE 1 › A 32-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented for induction at 41 weeks and 2 days of gestation. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. A compound presentation and a prolonged second stage of labor made vacuum assistance necessary. The infant had both a true umbilical cord knot (TUCK) (FIGURE 1A) and double nuchal cord.

CASE 2 › A 46-year-old G3P0 at 38 weeks of gestation by in vitro fertilization underwent an uncomplicated primary low transverse cesarean (C-section) delivery of dichorionic/diamniotic twins. The C-section had been necessary because baby A had been in the breech position. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. Baby A had a velamentous cord insertion, and baby B had a succenturiate lobe and a TUCK.

CASE 3 › A 23-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course chose to have a repeat C-section and delivered at 41 weeks in active labor. Fetal heart monitoring showed no abnormalities. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK was noted at time of delivery.

CASE 4 › A 30-year-old G1P0 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented in active labor at 40 weeks and 4 days of gestation. At 7 cm cervical dilation, monitoring showed repeated deep variable fetal heart rate decelerations. The patient underwent an uncomplicated primary C-section. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK (FIGURE 1B) and double nuchal cord were found at time of delivery.

DISCUSSION

TUCKs are thought to occur when a fetus passes through a loop in the umbilical cord. They occur in <2% of term deliveries.1,2 TUCKs differ from false knots. False knots are exaggerated loops of cord vasculature.

Risk factors that have been independently associated with TUCK include advanced maternal age (AMA; >35 years), multiparity, diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, polyhydramnios, and previous spontaneous abortion.1-3 In one study, 72% of women with a TUCK were multiparous.3 Hershkovitz et al2 suggested that laxity of uterine and abdominal musculature in multiparous patients may contribute to increased room for TUCK formation.

The adjusted odds ratio of having a TUCK is 2.53 in women with diabetes mellitus.3 Hyperglycemia can contribute to increased fetal movements, thereby increasing the risk of TUCK development.2 Polyhydramnios is often found in patients with diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes.3 The incidence is higher in monoamniotic twins.4

Being a male and having a longer umbilical cord may also increase the risk of TUCK. On average, male infants have longer cords than females, which may predispose them to TUCKs.3 Räisänen et al3 found that the mean cord length in TUCK infants was 16.9 cm longer than in infants without a TUCK.

Of our 4 patients, one was of AMA, 2 were multiparous, and 3 of the 4 infants who developed TUCK were male.

TUCK is usually diagnosed at delivery

Most cases of TUCK are found incidentally at the time of delivery. Antenatal diagnosis is difficult, because loops of cord lying together are easily mistaken for knots on ultrasound.5 Sepulveda et al6 evaluated the use of 3D power Doppler in 8 cases of suspected TUCK; only 63% were confirmed at delivery. Some researchers have found improved detection of TUCK with color Doppler and 4D ultrasound, which have demonstrated a “hanging noose sign” (a transverse section of umbilical cord surrounded by a loop of cord) as well as views of the cord under pressure.7-10

Outcomes associated with TUCK vary greatly. Neonates affected by TUCK have a 4% to 10% increased risk of stillbirth, usually attributed to knot tightening.2,4,11,12

In addition, there is an increased incidence of fetal heart rate abnormalities during labor.1,3,12,13

There is no increase in the incidence of assisted vaginal or C-section delivery.12 And as for whether TUCK affects an infant’s size or weight, one study found TUCK infants had a 3.2-fold higher risk of measuring small for gestational age, potentially due to chronic umbilical cord compromise; however, mean birth weight between study and control groups did not differ significantly.3

Outcomes for our patients and their infants. All 4 cases had good outcomes (TABLE). The umbilical cord knot produced no detectable fetal compromise in cases 1 through 3. In Case 4, electronic fetal monitoring showed repeated variable fetal heart rate decelerations, presumably associated with cord compression.

THE TAKEAWAY

Pregnant women who may be at risk for experiencing a TUCK include those who are older than age 35, multiparous, carrying a boy, or have diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, or polyhydramnios. While it is good to be aware of these risk factors, there are no recommended changes in management based on risk or ultrasound findings unless there is additional concern for fetal compromise.

Antenatal diagnosis of TUCK is challenging, but Doppler ultrasound may be able to identify the condition. Most cases of TUCK are noted on delivery, and outcomes are generally positive, although infants in whom the TUCK tightens may have an increased risk of heart rate abnormalities or stillbirth.

1. Joura EA, Zeisler H, Sator MO. Epidemiology and clinical value of true umbilical cord knots [in German]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1998;110:232-235.

2. Hershkovitz R, Silberstein T, Sheiner E, et al. Risk factors associated with true knots of the umbilical cord. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98:36-39.

3. Räisänen S, Georgiadis L, Harju M, et al. True umbilical cord knot and obstetric outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122: 18-21.

4. Maher JT, Conti JA. A comparison of umbilical cord blood gas values between newborns with and without true knots. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:863-866.

5. Clerici G, Koutras I, Luzietti R, et al. Multiple true umbilical knots: a silent risk for intrauterine growth restriction with anomalous hemodynamic pattern. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2007;22:440-443.

6. Sepulveda W, Shennan AH, Bower S, et al. True knot of the umbilical cord: a difficult prenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;5:106-108.

7. Hasbun J, Alcalde JL, Sepulveda W. Three-dimensional power Doppler sonography in the prenatal diagnosis of a true knot of the umbilical cord: value and limitations. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1215-1220.

8. Rodriguez N, Angarita AM, Casasbuenas A, et al. Three-dimensional high-definition flow imaging in prenatal diagnosis of a true umbilical cord knot. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:245-246.

9. Scioscia M, Fornalè M, Bruni F, et al. Four-dimensional and Doppler sonography in the diagnosis and surveillance of a true cord knot. J Clin Ultrasound. 2011;39: 157-159.

10. Sherer DM, Dalloul M, Zigalo A, et al. Power Doppler and 3-dimensional sonographic diagnosis of multiple separate true knots of the umbilical cord. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24: 1321-1323.

11. Sørnes T. Umbilical cord knots. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:157-159.

12. Airas U, Heinonen S. Clinical significance of true umbilical knots: a population-based analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2002;19:127-132.

13. Szczepanik ME, Wittich AC. True knot of the umbilical cord: a report of 13 cases. Mil Med. 2007;172:892-894.

THE CASES

CASE 1 › A 32-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented for induction at 41 weeks and 2 days of gestation. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. A compound presentation and a prolonged second stage of labor made vacuum assistance necessary. The infant had both a true umbilical cord knot (TUCK) (FIGURE 1A) and double nuchal cord.

CASE 2 › A 46-year-old G3P0 at 38 weeks of gestation by in vitro fertilization underwent an uncomplicated primary low transverse cesarean (C-section) delivery of dichorionic/diamniotic twins. The C-section had been necessary because baby A had been in the breech position. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. Baby A had a velamentous cord insertion, and baby B had a succenturiate lobe and a TUCK.

CASE 3 › A 23-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course chose to have a repeat C-section and delivered at 41 weeks in active labor. Fetal heart monitoring showed no abnormalities. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK was noted at time of delivery.

CASE 4 › A 30-year-old G1P0 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented in active labor at 40 weeks and 4 days of gestation. At 7 cm cervical dilation, monitoring showed repeated deep variable fetal heart rate decelerations. The patient underwent an uncomplicated primary C-section. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK (FIGURE 1B) and double nuchal cord were found at time of delivery.

DISCUSSION

TUCKs are thought to occur when a fetus passes through a loop in the umbilical cord. They occur in <2% of term deliveries.1,2 TUCKs differ from false knots. False knots are exaggerated loops of cord vasculature.

Risk factors that have been independently associated with TUCK include advanced maternal age (AMA; >35 years), multiparity, diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, polyhydramnios, and previous spontaneous abortion.1-3 In one study, 72% of women with a TUCK were multiparous.3 Hershkovitz et al2 suggested that laxity of uterine and abdominal musculature in multiparous patients may contribute to increased room for TUCK formation.

The adjusted odds ratio of having a TUCK is 2.53 in women with diabetes mellitus.3 Hyperglycemia can contribute to increased fetal movements, thereby increasing the risk of TUCK development.2 Polyhydramnios is often found in patients with diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes.3 The incidence is higher in monoamniotic twins.4

Being a male and having a longer umbilical cord may also increase the risk of TUCK. On average, male infants have longer cords than females, which may predispose them to TUCKs.3 Räisänen et al3 found that the mean cord length in TUCK infants was 16.9 cm longer than in infants without a TUCK.

Of our 4 patients, one was of AMA, 2 were multiparous, and 3 of the 4 infants who developed TUCK were male.

TUCK is usually diagnosed at delivery

Most cases of TUCK are found incidentally at the time of delivery. Antenatal diagnosis is difficult, because loops of cord lying together are easily mistaken for knots on ultrasound.5 Sepulveda et al6 evaluated the use of 3D power Doppler in 8 cases of suspected TUCK; only 63% were confirmed at delivery. Some researchers have found improved detection of TUCK with color Doppler and 4D ultrasound, which have demonstrated a “hanging noose sign” (a transverse section of umbilical cord surrounded by a loop of cord) as well as views of the cord under pressure.7-10

Outcomes associated with TUCK vary greatly. Neonates affected by TUCK have a 4% to 10% increased risk of stillbirth, usually attributed to knot tightening.2,4,11,12

In addition, there is an increased incidence of fetal heart rate abnormalities during labor.1,3,12,13

There is no increase in the incidence of assisted vaginal or C-section delivery.12 And as for whether TUCK affects an infant’s size or weight, one study found TUCK infants had a 3.2-fold higher risk of measuring small for gestational age, potentially due to chronic umbilical cord compromise; however, mean birth weight between study and control groups did not differ significantly.3

Outcomes for our patients and their infants. All 4 cases had good outcomes (TABLE). The umbilical cord knot produced no detectable fetal compromise in cases 1 through 3. In Case 4, electronic fetal monitoring showed repeated variable fetal heart rate decelerations, presumably associated with cord compression.

THE TAKEAWAY

Pregnant women who may be at risk for experiencing a TUCK include those who are older than age 35, multiparous, carrying a boy, or have diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, or polyhydramnios. While it is good to be aware of these risk factors, there are no recommended changes in management based on risk or ultrasound findings unless there is additional concern for fetal compromise.

Antenatal diagnosis of TUCK is challenging, but Doppler ultrasound may be able to identify the condition. Most cases of TUCK are noted on delivery, and outcomes are generally positive, although infants in whom the TUCK tightens may have an increased risk of heart rate abnormalities or stillbirth.

THE CASES

CASE 1 › A 32-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented for induction at 41 weeks and 2 days of gestation. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. A compound presentation and a prolonged second stage of labor made vacuum assistance necessary. The infant had both a true umbilical cord knot (TUCK) (FIGURE 1A) and double nuchal cord.

CASE 2 › A 46-year-old G3P0 at 38 weeks of gestation by in vitro fertilization underwent an uncomplicated primary low transverse cesarean (C-section) delivery of dichorionic/diamniotic twins. The C-section had been necessary because baby A had been in the breech position. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. Baby A had a velamentous cord insertion, and baby B had a succenturiate lobe and a TUCK.

CASE 3 › A 23-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course chose to have a repeat C-section and delivered at 41 weeks in active labor. Fetal heart monitoring showed no abnormalities. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK was noted at time of delivery.

CASE 4 › A 30-year-old G1P0 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented in active labor at 40 weeks and 4 days of gestation. At 7 cm cervical dilation, monitoring showed repeated deep variable fetal heart rate decelerations. The patient underwent an uncomplicated primary C-section. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK (FIGURE 1B) and double nuchal cord were found at time of delivery.

DISCUSSION

TUCKs are thought to occur when a fetus passes through a loop in the umbilical cord. They occur in <2% of term deliveries.1,2 TUCKs differ from false knots. False knots are exaggerated loops of cord vasculature.

Risk factors that have been independently associated with TUCK include advanced maternal age (AMA; >35 years), multiparity, diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, polyhydramnios, and previous spontaneous abortion.1-3 In one study, 72% of women with a TUCK were multiparous.3 Hershkovitz et al2 suggested that laxity of uterine and abdominal musculature in multiparous patients may contribute to increased room for TUCK formation.

The adjusted odds ratio of having a TUCK is 2.53 in women with diabetes mellitus.3 Hyperglycemia can contribute to increased fetal movements, thereby increasing the risk of TUCK development.2 Polyhydramnios is often found in patients with diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes.3 The incidence is higher in monoamniotic twins.4

Being a male and having a longer umbilical cord may also increase the risk of TUCK. On average, male infants have longer cords than females, which may predispose them to TUCKs.3 Räisänen et al3 found that the mean cord length in TUCK infants was 16.9 cm longer than in infants without a TUCK.

Of our 4 patients, one was of AMA, 2 were multiparous, and 3 of the 4 infants who developed TUCK were male.

TUCK is usually diagnosed at delivery

Most cases of TUCK are found incidentally at the time of delivery. Antenatal diagnosis is difficult, because loops of cord lying together are easily mistaken for knots on ultrasound.5 Sepulveda et al6 evaluated the use of 3D power Doppler in 8 cases of suspected TUCK; only 63% were confirmed at delivery. Some researchers have found improved detection of TUCK with color Doppler and 4D ultrasound, which have demonstrated a “hanging noose sign” (a transverse section of umbilical cord surrounded by a loop of cord) as well as views of the cord under pressure.7-10

Outcomes associated with TUCK vary greatly. Neonates affected by TUCK have a 4% to 10% increased risk of stillbirth, usually attributed to knot tightening.2,4,11,12

In addition, there is an increased incidence of fetal heart rate abnormalities during labor.1,3,12,13

There is no increase in the incidence of assisted vaginal or C-section delivery.12 And as for whether TUCK affects an infant’s size or weight, one study found TUCK infants had a 3.2-fold higher risk of measuring small for gestational age, potentially due to chronic umbilical cord compromise; however, mean birth weight between study and control groups did not differ significantly.3

Outcomes for our patients and their infants. All 4 cases had good outcomes (TABLE). The umbilical cord knot produced no detectable fetal compromise in cases 1 through 3. In Case 4, electronic fetal monitoring showed repeated variable fetal heart rate decelerations, presumably associated with cord compression.

THE TAKEAWAY

Pregnant women who may be at risk for experiencing a TUCK include those who are older than age 35, multiparous, carrying a boy, or have diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, or polyhydramnios. While it is good to be aware of these risk factors, there are no recommended changes in management based on risk or ultrasound findings unless there is additional concern for fetal compromise.

Antenatal diagnosis of TUCK is challenging, but Doppler ultrasound may be able to identify the condition. Most cases of TUCK are noted on delivery, and outcomes are generally positive, although infants in whom the TUCK tightens may have an increased risk of heart rate abnormalities or stillbirth.

1. Joura EA, Zeisler H, Sator MO. Epidemiology and clinical value of true umbilical cord knots [in German]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1998;110:232-235.

2. Hershkovitz R, Silberstein T, Sheiner E, et al. Risk factors associated with true knots of the umbilical cord. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98:36-39.

3. Räisänen S, Georgiadis L, Harju M, et al. True umbilical cord knot and obstetric outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122: 18-21.

4. Maher JT, Conti JA. A comparison of umbilical cord blood gas values between newborns with and without true knots. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:863-866.

5. Clerici G, Koutras I, Luzietti R, et al. Multiple true umbilical knots: a silent risk for intrauterine growth restriction with anomalous hemodynamic pattern. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2007;22:440-443.

6. Sepulveda W, Shennan AH, Bower S, et al. True knot of the umbilical cord: a difficult prenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;5:106-108.

7. Hasbun J, Alcalde JL, Sepulveda W. Three-dimensional power Doppler sonography in the prenatal diagnosis of a true knot of the umbilical cord: value and limitations. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1215-1220.

8. Rodriguez N, Angarita AM, Casasbuenas A, et al. Three-dimensional high-definition flow imaging in prenatal diagnosis of a true umbilical cord knot. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:245-246.

9. Scioscia M, Fornalè M, Bruni F, et al. Four-dimensional and Doppler sonography in the diagnosis and surveillance of a true cord knot. J Clin Ultrasound. 2011;39: 157-159.

10. Sherer DM, Dalloul M, Zigalo A, et al. Power Doppler and 3-dimensional sonographic diagnosis of multiple separate true knots of the umbilical cord. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24: 1321-1323.

11. Sørnes T. Umbilical cord knots. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:157-159.

12. Airas U, Heinonen S. Clinical significance of true umbilical knots: a population-based analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2002;19:127-132.

13. Szczepanik ME, Wittich AC. True knot of the umbilical cord: a report of 13 cases. Mil Med. 2007;172:892-894.

1. Joura EA, Zeisler H, Sator MO. Epidemiology and clinical value of true umbilical cord knots [in German]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1998;110:232-235.

2. Hershkovitz R, Silberstein T, Sheiner E, et al. Risk factors associated with true knots of the umbilical cord. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98:36-39.

3. Räisänen S, Georgiadis L, Harju M, et al. True umbilical cord knot and obstetric outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122: 18-21.

4. Maher JT, Conti JA. A comparison of umbilical cord blood gas values between newborns with and without true knots. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:863-866.

5. Clerici G, Koutras I, Luzietti R, et al. Multiple true umbilical knots: a silent risk for intrauterine growth restriction with anomalous hemodynamic pattern. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2007;22:440-443.

6. Sepulveda W, Shennan AH, Bower S, et al. True knot of the umbilical cord: a difficult prenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;5:106-108.

7. Hasbun J, Alcalde JL, Sepulveda W. Three-dimensional power Doppler sonography in the prenatal diagnosis of a true knot of the umbilical cord: value and limitations. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1215-1220.

8. Rodriguez N, Angarita AM, Casasbuenas A, et al. Three-dimensional high-definition flow imaging in prenatal diagnosis of a true umbilical cord knot. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:245-246.

9. Scioscia M, Fornalè M, Bruni F, et al. Four-dimensional and Doppler sonography in the diagnosis and surveillance of a true cord knot. J Clin Ultrasound. 2011;39: 157-159.

10. Sherer DM, Dalloul M, Zigalo A, et al. Power Doppler and 3-dimensional sonographic diagnosis of multiple separate true knots of the umbilical cord. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24: 1321-1323.

11. Sørnes T. Umbilical cord knots. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:157-159.

12. Airas U, Heinonen S. Clinical significance of true umbilical knots: a population-based analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2002;19:127-132.

13. Szczepanik ME, Wittich AC. True knot of the umbilical cord: a report of 13 cases. Mil Med. 2007;172:892-894.

Painless cutaneous nodules

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 46-YEAR-OLD MAN came into our family medicine clinic because he wanted a few “lumps” removed from his left medial elbow and the back of his right thigh and knee. He indicated that he’d had the painless lesions for a long time, but that recently they’d started bothering him because they were getting caught on his clothes.

Other than these lesions, his past medical, social, and surgical histories were unremarkable. He indicated that his mother and 3 of his 5 siblings had similar lesions.

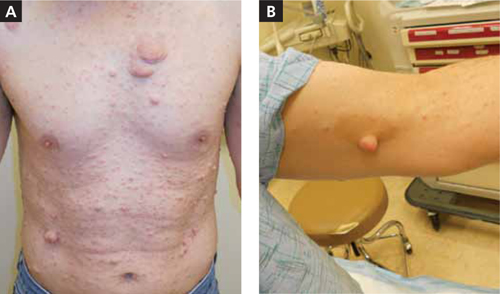

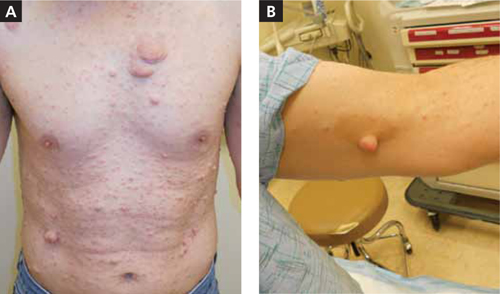

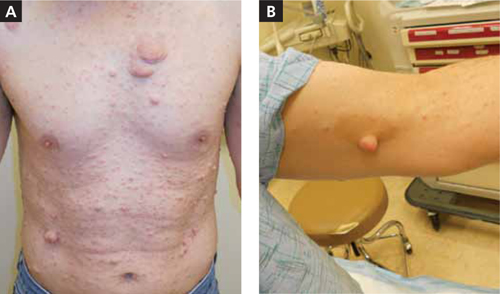

On physical exam, the patient had multiple nontender, soft, pedunculated, and relatively mobile nodules in different sizes (FIGURE 1A). There were also a few well-circumscribed and light brown patches on his left medial elbow (FIGURE 1B), the back of his right thigh, and his upper back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Neurofibromatosis type 1

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant multisystem disorder affecting about one in 3000 people.1-3 The NF1 gene is on chromosome 17q11.2, which encodes for neurofibromin protein.2,3 About half of these patients demonstrate a spontaneous mutation.1-5 Clinical features include cutaneous, subcutaneous, skeletal, peripheral, and central nervous systems abnormalities.

3 common features

Neurofibroma is the hallmark of NF1. Cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors consisting of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, peripheral cells, mast cells, axons, and blood vessels.1-5 Neurofibromas usually develop when patients are in their late teens; they are often painless.

Café-au-lait spots are well-circumscribed, evenly pigmented, light to dark brown macules and/or patches with an average size of 2 to 5 cm (FIGURE 1B). Up to 10% of the general population may have one or 2 café-au-lait spots with no other abnormalities.6 Patients with NF1 will have 6 or more.1

Skin fold freckling is the most specific feature in patients with NF1. This freckling usually occurs in the axilla and groin regions when patients are between 3 and 5 years of age. The freckles are typically small, with an average size of 1 to 3 mm.

Other less common clinical features of NF1 include plexiform neurofibroma, skeletal abnormalities (short stature, scoliosis, long bone dysplasia, and osteopenia/ osteoporosis), Lisch nodules (iris hamartomas), neurocognitive deficits, cardiovascular abnormalities, and optic pathway gliomas.1-5

FIGURE 1

Widespread cutaneous nodules with hyperpigmented patches

Is it neurofibromatosis type 1, or one of these 4 conditions?

Consider these conditions in the differential diagnosis of a patient who presents with soft, pedunculated nodules:

- Segmental/mosaic NF1 occurs as a result of NF1 somatic gene mutation. Clinical manifestations (pigmentary changes, tumor growths, or both) are limited to one or more body segments.3 The extent of the body parts affected depends on the time of the mutation in embryonic development.

- Neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) is an autosomal dominant disease affecting one in 25,000 individuals.2 The characteristic feature is bilateral vestibular schwannomas.4,5 Other clinical features include meningiomas, schwannomas, gliomas, neurofibromas, and posterior subcapsular lens opacity. Café-au-lait spots are less common in NF2 than in NF1; only about one-third of NF2 patients have them.6

- Schwannomatosis is a disease with multiple subcutaneous, peripheral nerve, and spinal schwannomas.4,5 Patients do not have the vestibular schwannomas or the ophthalmologic features of NF2.

- Lipomatosis is an autosomal dominant disease featuring multiple lipomas on the trunk, proximal thighs, and distal arms. Depending on the location, the lipomas can be tender to touch. Biopsy may be necessary to differentiate lipomas from neurofibromas and schwannomas.

Diagnosis hinges on 2 of these 7 criteria

For adult patients, the diagnosis is clinical and straightforward. At least 2 of the following criteria should be present for the diagnosis:1-6

- 6 or more café-au-lait spots

- axillary or inguinal freckling

- 2 or more neurofibromas

- a first-degree relative with NF1

- 2 or more Lisch nodules

- a distinctive osseous lesion

- optic pathway glioma.

The diagnosis in youngsters, especially those younger than 8 years, can be difficult and may require genetic testing. Genetic testing is also recommended for individuals with a single sign, or with variant disorders.3 Genetic counseling and testing are also recommended in preimplantation and prenatal situations.3 Biopsy of the cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions for diagnostic purposes is not usually recommended.1-5

Management is challenging as there is no definitive treatment

The effect of NF1 on patients’ lives is significant. Management usually requires a multidisciplinary approach led by a primary care physician.3 To date, there is no definitive treatment for NF1.

Removal of symptomatic cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions is recommended; however, the recurrence rate is high1-3 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B). About 10% of patients with NF1 will develop a malignant nerve sheath tumor, which usually arises from preexisting plexiform neurofibromas.1-4 Surgical excision with clear margins is the goal of treatment.2

A good outcome for my patient

The nodules on the patient’s medial elbow and the back of his thigh and knee were excised. The pathology confirmed the diagnosis. There was no malignant transformation.

CORRESPONDENCE Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Family Medicine Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@ucdenver.edu

1. Williams VC, Lucas J, Babcock MA, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 revisited. Pediatrics. 2009;123:124-133.

2. Ferner RE. The neurofibromatoses. Pract Neurol. 2010;10:82-93.

3. Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

4. Ferner RE, Huson SM, Thomas N, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of individuals with neurofibromatosis 1. J Med Genet. 2007;44:81-88.

5. Gerber PA, Antal AS, Neumann NJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:102-105.

6. Shah KN. The diagnostic and clinical significance of café-au-lait macules. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1131-1153.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 46-YEAR-OLD MAN came into our family medicine clinic because he wanted a few “lumps” removed from his left medial elbow and the back of his right thigh and knee. He indicated that he’d had the painless lesions for a long time, but that recently they’d started bothering him because they were getting caught on his clothes.

Other than these lesions, his past medical, social, and surgical histories were unremarkable. He indicated that his mother and 3 of his 5 siblings had similar lesions.

On physical exam, the patient had multiple nontender, soft, pedunculated, and relatively mobile nodules in different sizes (FIGURE 1A). There were also a few well-circumscribed and light brown patches on his left medial elbow (FIGURE 1B), the back of his right thigh, and his upper back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Neurofibromatosis type 1

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant multisystem disorder affecting about one in 3000 people.1-3 The NF1 gene is on chromosome 17q11.2, which encodes for neurofibromin protein.2,3 About half of these patients demonstrate a spontaneous mutation.1-5 Clinical features include cutaneous, subcutaneous, skeletal, peripheral, and central nervous systems abnormalities.

3 common features

Neurofibroma is the hallmark of NF1. Cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors consisting of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, peripheral cells, mast cells, axons, and blood vessels.1-5 Neurofibromas usually develop when patients are in their late teens; they are often painless.

Café-au-lait spots are well-circumscribed, evenly pigmented, light to dark brown macules and/or patches with an average size of 2 to 5 cm (FIGURE 1B). Up to 10% of the general population may have one or 2 café-au-lait spots with no other abnormalities.6 Patients with NF1 will have 6 or more.1

Skin fold freckling is the most specific feature in patients with NF1. This freckling usually occurs in the axilla and groin regions when patients are between 3 and 5 years of age. The freckles are typically small, with an average size of 1 to 3 mm.

Other less common clinical features of NF1 include plexiform neurofibroma, skeletal abnormalities (short stature, scoliosis, long bone dysplasia, and osteopenia/ osteoporosis), Lisch nodules (iris hamartomas), neurocognitive deficits, cardiovascular abnormalities, and optic pathway gliomas.1-5

FIGURE 1

Widespread cutaneous nodules with hyperpigmented patches

Is it neurofibromatosis type 1, or one of these 4 conditions?

Consider these conditions in the differential diagnosis of a patient who presents with soft, pedunculated nodules:

- Segmental/mosaic NF1 occurs as a result of NF1 somatic gene mutation. Clinical manifestations (pigmentary changes, tumor growths, or both) are limited to one or more body segments.3 The extent of the body parts affected depends on the time of the mutation in embryonic development.

- Neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) is an autosomal dominant disease affecting one in 25,000 individuals.2 The characteristic feature is bilateral vestibular schwannomas.4,5 Other clinical features include meningiomas, schwannomas, gliomas, neurofibromas, and posterior subcapsular lens opacity. Café-au-lait spots are less common in NF2 than in NF1; only about one-third of NF2 patients have them.6

- Schwannomatosis is a disease with multiple subcutaneous, peripheral nerve, and spinal schwannomas.4,5 Patients do not have the vestibular schwannomas or the ophthalmologic features of NF2.

- Lipomatosis is an autosomal dominant disease featuring multiple lipomas on the trunk, proximal thighs, and distal arms. Depending on the location, the lipomas can be tender to touch. Biopsy may be necessary to differentiate lipomas from neurofibromas and schwannomas.

Diagnosis hinges on 2 of these 7 criteria

For adult patients, the diagnosis is clinical and straightforward. At least 2 of the following criteria should be present for the diagnosis:1-6

- 6 or more café-au-lait spots

- axillary or inguinal freckling

- 2 or more neurofibromas

- a first-degree relative with NF1

- 2 or more Lisch nodules

- a distinctive osseous lesion

- optic pathway glioma.

The diagnosis in youngsters, especially those younger than 8 years, can be difficult and may require genetic testing. Genetic testing is also recommended for individuals with a single sign, or with variant disorders.3 Genetic counseling and testing are also recommended in preimplantation and prenatal situations.3 Biopsy of the cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions for diagnostic purposes is not usually recommended.1-5

Management is challenging as there is no definitive treatment

The effect of NF1 on patients’ lives is significant. Management usually requires a multidisciplinary approach led by a primary care physician.3 To date, there is no definitive treatment for NF1.

Removal of symptomatic cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions is recommended; however, the recurrence rate is high1-3 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B). About 10% of patients with NF1 will develop a malignant nerve sheath tumor, which usually arises from preexisting plexiform neurofibromas.1-4 Surgical excision with clear margins is the goal of treatment.2

A good outcome for my patient

The nodules on the patient’s medial elbow and the back of his thigh and knee were excised. The pathology confirmed the diagnosis. There was no malignant transformation.

CORRESPONDENCE Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Family Medicine Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@ucdenver.edu

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 46-YEAR-OLD MAN came into our family medicine clinic because he wanted a few “lumps” removed from his left medial elbow and the back of his right thigh and knee. He indicated that he’d had the painless lesions for a long time, but that recently they’d started bothering him because they were getting caught on his clothes.

Other than these lesions, his past medical, social, and surgical histories were unremarkable. He indicated that his mother and 3 of his 5 siblings had similar lesions.

On physical exam, the patient had multiple nontender, soft, pedunculated, and relatively mobile nodules in different sizes (FIGURE 1A). There were also a few well-circumscribed and light brown patches on his left medial elbow (FIGURE 1B), the back of his right thigh, and his upper back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Neurofibromatosis type 1

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant multisystem disorder affecting about one in 3000 people.1-3 The NF1 gene is on chromosome 17q11.2, which encodes for neurofibromin protein.2,3 About half of these patients demonstrate a spontaneous mutation.1-5 Clinical features include cutaneous, subcutaneous, skeletal, peripheral, and central nervous systems abnormalities.

3 common features

Neurofibroma is the hallmark of NF1. Cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors consisting of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, peripheral cells, mast cells, axons, and blood vessels.1-5 Neurofibromas usually develop when patients are in their late teens; they are often painless.

Café-au-lait spots are well-circumscribed, evenly pigmented, light to dark brown macules and/or patches with an average size of 2 to 5 cm (FIGURE 1B). Up to 10% of the general population may have one or 2 café-au-lait spots with no other abnormalities.6 Patients with NF1 will have 6 or more.1

Skin fold freckling is the most specific feature in patients with NF1. This freckling usually occurs in the axilla and groin regions when patients are between 3 and 5 years of age. The freckles are typically small, with an average size of 1 to 3 mm.

Other less common clinical features of NF1 include plexiform neurofibroma, skeletal abnormalities (short stature, scoliosis, long bone dysplasia, and osteopenia/ osteoporosis), Lisch nodules (iris hamartomas), neurocognitive deficits, cardiovascular abnormalities, and optic pathway gliomas.1-5

FIGURE 1

Widespread cutaneous nodules with hyperpigmented patches

Is it neurofibromatosis type 1, or one of these 4 conditions?

Consider these conditions in the differential diagnosis of a patient who presents with soft, pedunculated nodules:

- Segmental/mosaic NF1 occurs as a result of NF1 somatic gene mutation. Clinical manifestations (pigmentary changes, tumor growths, or both) are limited to one or more body segments.3 The extent of the body parts affected depends on the time of the mutation in embryonic development.

- Neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) is an autosomal dominant disease affecting one in 25,000 individuals.2 The characteristic feature is bilateral vestibular schwannomas.4,5 Other clinical features include meningiomas, schwannomas, gliomas, neurofibromas, and posterior subcapsular lens opacity. Café-au-lait spots are less common in NF2 than in NF1; only about one-third of NF2 patients have them.6

- Schwannomatosis is a disease with multiple subcutaneous, peripheral nerve, and spinal schwannomas.4,5 Patients do not have the vestibular schwannomas or the ophthalmologic features of NF2.

- Lipomatosis is an autosomal dominant disease featuring multiple lipomas on the trunk, proximal thighs, and distal arms. Depending on the location, the lipomas can be tender to touch. Biopsy may be necessary to differentiate lipomas from neurofibromas and schwannomas.

Diagnosis hinges on 2 of these 7 criteria

For adult patients, the diagnosis is clinical and straightforward. At least 2 of the following criteria should be present for the diagnosis:1-6

- 6 or more café-au-lait spots

- axillary or inguinal freckling

- 2 or more neurofibromas

- a first-degree relative with NF1

- 2 or more Lisch nodules

- a distinctive osseous lesion

- optic pathway glioma.

The diagnosis in youngsters, especially those younger than 8 years, can be difficult and may require genetic testing. Genetic testing is also recommended for individuals with a single sign, or with variant disorders.3 Genetic counseling and testing are also recommended in preimplantation and prenatal situations.3 Biopsy of the cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions for diagnostic purposes is not usually recommended.1-5

Management is challenging as there is no definitive treatment

The effect of NF1 on patients’ lives is significant. Management usually requires a multidisciplinary approach led by a primary care physician.3 To date, there is no definitive treatment for NF1.

Removal of symptomatic cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions is recommended; however, the recurrence rate is high1-3 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B). About 10% of patients with NF1 will develop a malignant nerve sheath tumor, which usually arises from preexisting plexiform neurofibromas.1-4 Surgical excision with clear margins is the goal of treatment.2

A good outcome for my patient

The nodules on the patient’s medial elbow and the back of his thigh and knee were excised. The pathology confirmed the diagnosis. There was no malignant transformation.

CORRESPONDENCE Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Family Medicine Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@ucdenver.edu

1. Williams VC, Lucas J, Babcock MA, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 revisited. Pediatrics. 2009;123:124-133.