User login

The Shield Sign of Cutaneous Metastases Is Associated With Carcinoma Hemorrhagiectoides

To the Editor:

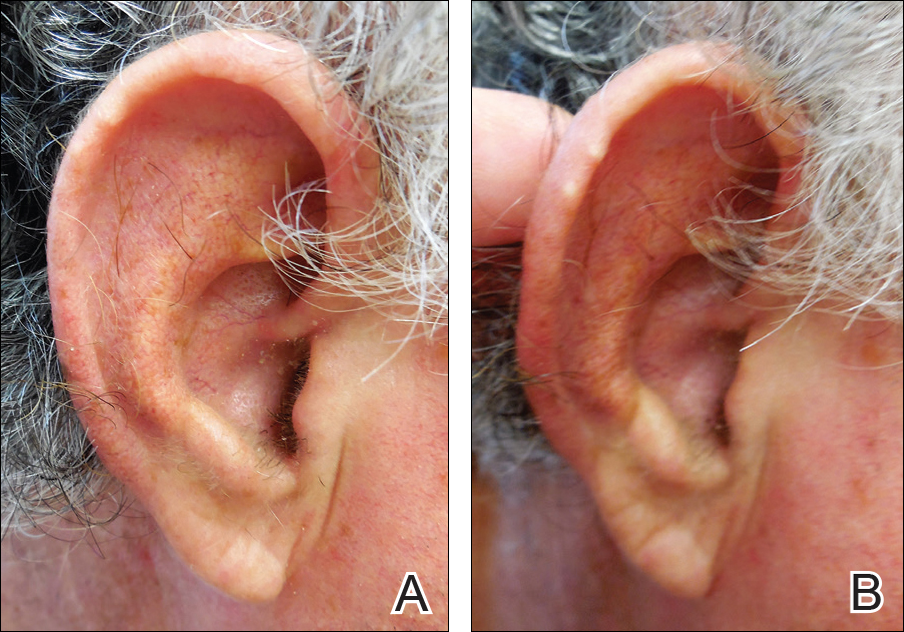

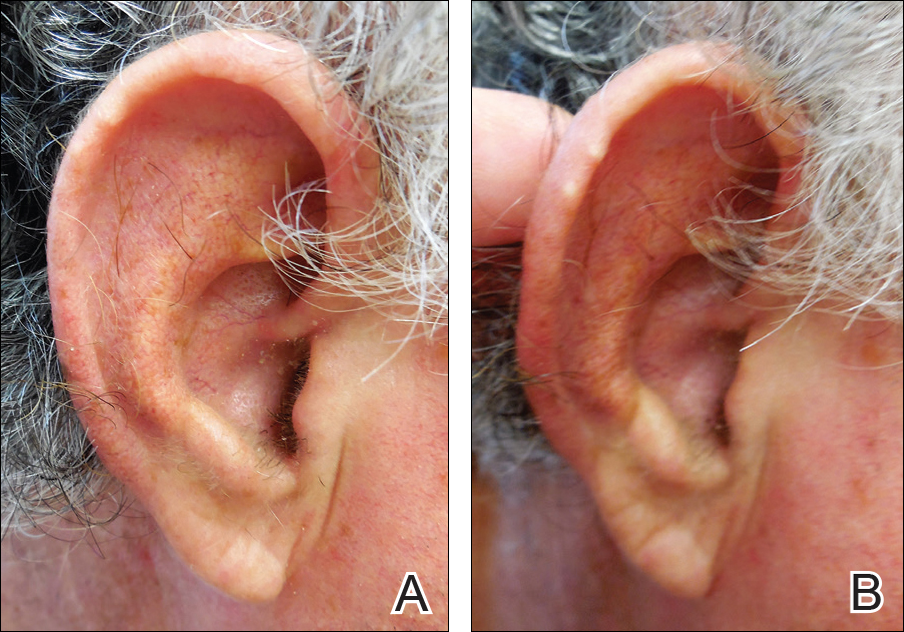

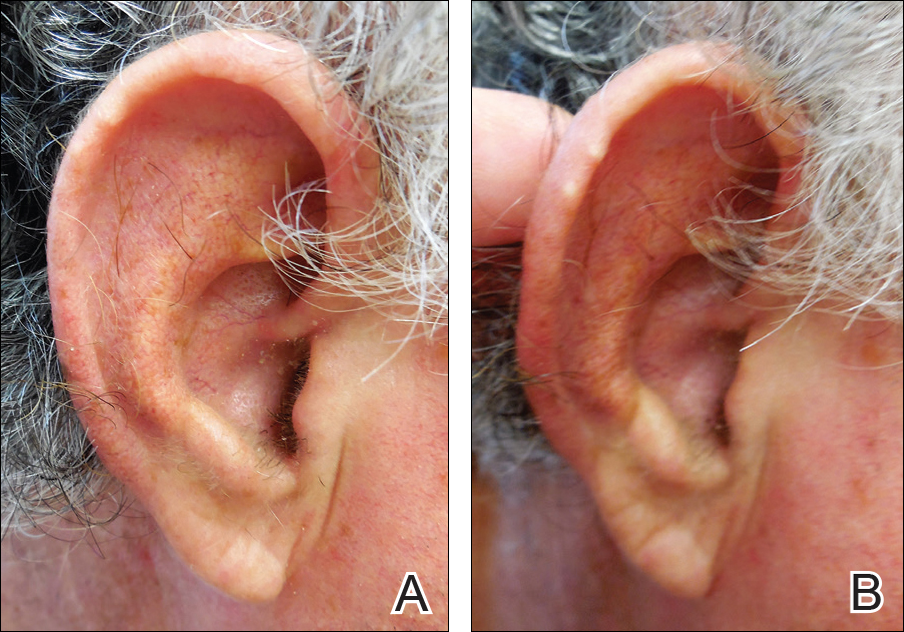

We read with interest the Case Letter from Wang et al1 (Cutis. 2023;112:E13-E15) of a 60-year-old man whose metastatic salivary duct adenocarcinoma manifested with the shield sign as well as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. Cutaneous metastases have seldom been described in association with salivary duct carcinoma.2-7 In addition, carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides–associated shield sign has not been commonly reported.5,8-12

Salivary duct carcinoma—an uncommon head and neck malignancy characterized by androgen receptor expression—rarely is associated with cutaneous metastases. Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous, metastatic, salivary duct carcinoma, and/or skin, including the patient described by Wang et al,1 there have been 8 individuals with cutaneous metastases from this cancer. The morphology of the cutaneous metastases has varied from angiomatous to angiokeratomalike (black and keratotic) papules, bullae, macules (red), papules and nodules (erythematous and scaly), plaques (cellulitislike and confluent that were purpuric, hemorrhagic, and violaceous), pseudovesicles, purpuric papules, subcutaneous nodules, and an ulcer (superficial and mimicked a basal cell carcinoma).1-7 Remarkably, 4 of 8 patients (50%) with salivary duct carcinoma cutaneous metastases presented with a shield sign,5,7 including the case reported by Wang et al.1

The shield sign is a distinctive clinical manifestation of cutaneous metastasis.10 It was named to describe the skin metastases located predominantly on the chest area that would be covered by a medieval knight’s shield5,10,12; metastatic lesions also have been noted on the proximal arm and/or the upper back in a similar distribution.8,9 To date, based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms breast cancer, carcinoma, hemorrhagiectoides, metastases, salivary duct carcinoma, shield, and/or sign, the shield sign has been described in 6 patients with cutaneous metastases either from salivary duct carcinoma (4 patients)1,5,7 or breast cancer (2 patients).8,9 The shield sign pathologically corresponds to carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides, an inflammatory pattern of cutaneous metastases.5,11

Inflammatory cutaneous metastatic carcinoma has 3 distinctive clinical and pathologic manifestations.11 Carcinoma erysipelatoides and carcinoma telangiectoides were the earlier described variants.11 In 2012, carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides was described as the third pattern of inflammatory cutaneous metastasis.5

Carcinoma erysipelatoides, which clinically mimics cutaneous streptococcal cellulitis, appears as a well-defined erythematous patch or plaque; the tumor cells can be found in the lymphatic vessels and either are absent or minimally present in the dermis. Carcinoma telangiectoides, which clinically mimics idiopathic telangiectases, appears as an erythematous patch with prominent telangiectases; the tumor cells can be found in the blood vessels and are either absent or minimally present in the dermis. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides appears as purpuric or violaceous indurated plaques; the tumor cells are not only found in the blood vessels, in the lymphatic vessels, or both, but also can be mildly to extensively present in the dermis.5,10,11

In conclusion, the shield sign is a unique presentation of inflammatory cutaneous metastatic carcinoma, which is associated with carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. The clinical features of the infiltrated plaques correspond to the presence of tumor cells in the blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and the dermis; in addition, the purpuric and violaceous appearance correlates with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes or hemorrhage in the dermis. To date, half of the patients with skin metastases from salivary duct carcinoma have presented with carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides–associated shield sign.

Authors’ Response

We appreciate and welcome the comments provided by the authors. Drawing attention to unusual pathologic manifestations of cutaneous metastatic salivary duct carcinoma manifesting with the shield sign, the authors present a comprehensive review of 3 distinctive presentations: carcinoma erysipelatoides, carcinoma telangiectoides, and carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. The inclusion of these variants enriches the discussion and makes this letter a valuable addition to the literature on cutaneous metastatic carcinoma, particularly metastatic salivary duct carcinoma.

Xintong Wang, MD; William H. Westra, MD

From the Department of Pathology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

- Wang X, Vyas NS, Alghamdi AA, et al. Cutaneous presentation of metastatic salivary duct carcinoma. Cutis. 2023;112:E13-E15.

- Pollock JL, Catalano E. Metastatic ductal carcinoma of the parotid gland in a patient with sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1098-1099.

- Pollock JL. Metastatic carcinoma of the parotid gland resembling carcinoma of the breast. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:1093.

- Aygit AC, Top H, Cakir B, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma of the parotid gland metastasizing to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:48-50.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The “shield sign” in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Chakari W, Andersen L, Anderson JL. Cutaneous metastases from salivary duct carcinoma of the submandibular gland. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:254-258.

- Shin JY, Eun DH, Lee JY, et al. A case of cutaneous metastases of salivary duct carcinoma mimicking radiation recall dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2020;32:436-438.

- Aravena RC, Aravena DC, Velasco MJ, et al. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides: case report of an uncommon presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3hn3z850.

- Smith KA, Basko-Plluska J, Kothari AD, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2020;105:E20-E22.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Cutaneous metastatic cancer: carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides presenting as the shield sign. Cureus. 2021;13:e12627.

- Cohen PR. Pleomorphic appearance of breast cancer cutaneous metastases. Cureus. 2021;13:e20301.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Kurzrock R. Tumor lysis syndrome: introduction of a cutaneous variant and a new classification system. Cureus. 2021;13:e13816.

To the Editor:

We read with interest the Case Letter from Wang et al1 (Cutis. 2023;112:E13-E15) of a 60-year-old man whose metastatic salivary duct adenocarcinoma manifested with the shield sign as well as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. Cutaneous metastases have seldom been described in association with salivary duct carcinoma.2-7 In addition, carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides–associated shield sign has not been commonly reported.5,8-12

Salivary duct carcinoma—an uncommon head and neck malignancy characterized by androgen receptor expression—rarely is associated with cutaneous metastases. Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous, metastatic, salivary duct carcinoma, and/or skin, including the patient described by Wang et al,1 there have been 8 individuals with cutaneous metastases from this cancer. The morphology of the cutaneous metastases has varied from angiomatous to angiokeratomalike (black and keratotic) papules, bullae, macules (red), papules and nodules (erythematous and scaly), plaques (cellulitislike and confluent that were purpuric, hemorrhagic, and violaceous), pseudovesicles, purpuric papules, subcutaneous nodules, and an ulcer (superficial and mimicked a basal cell carcinoma).1-7 Remarkably, 4 of 8 patients (50%) with salivary duct carcinoma cutaneous metastases presented with a shield sign,5,7 including the case reported by Wang et al.1

The shield sign is a distinctive clinical manifestation of cutaneous metastasis.10 It was named to describe the skin metastases located predominantly on the chest area that would be covered by a medieval knight’s shield5,10,12; metastatic lesions also have been noted on the proximal arm and/or the upper back in a similar distribution.8,9 To date, based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms breast cancer, carcinoma, hemorrhagiectoides, metastases, salivary duct carcinoma, shield, and/or sign, the shield sign has been described in 6 patients with cutaneous metastases either from salivary duct carcinoma (4 patients)1,5,7 or breast cancer (2 patients).8,9 The shield sign pathologically corresponds to carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides, an inflammatory pattern of cutaneous metastases.5,11

Inflammatory cutaneous metastatic carcinoma has 3 distinctive clinical and pathologic manifestations.11 Carcinoma erysipelatoides and carcinoma telangiectoides were the earlier described variants.11 In 2012, carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides was described as the third pattern of inflammatory cutaneous metastasis.5

Carcinoma erysipelatoides, which clinically mimics cutaneous streptococcal cellulitis, appears as a well-defined erythematous patch or plaque; the tumor cells can be found in the lymphatic vessels and either are absent or minimally present in the dermis. Carcinoma telangiectoides, which clinically mimics idiopathic telangiectases, appears as an erythematous patch with prominent telangiectases; the tumor cells can be found in the blood vessels and are either absent or minimally present in the dermis. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides appears as purpuric or violaceous indurated plaques; the tumor cells are not only found in the blood vessels, in the lymphatic vessels, or both, but also can be mildly to extensively present in the dermis.5,10,11

In conclusion, the shield sign is a unique presentation of inflammatory cutaneous metastatic carcinoma, which is associated with carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. The clinical features of the infiltrated plaques correspond to the presence of tumor cells in the blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and the dermis; in addition, the purpuric and violaceous appearance correlates with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes or hemorrhage in the dermis. To date, half of the patients with skin metastases from salivary duct carcinoma have presented with carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides–associated shield sign.

Authors’ Response

We appreciate and welcome the comments provided by the authors. Drawing attention to unusual pathologic manifestations of cutaneous metastatic salivary duct carcinoma manifesting with the shield sign, the authors present a comprehensive review of 3 distinctive presentations: carcinoma erysipelatoides, carcinoma telangiectoides, and carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. The inclusion of these variants enriches the discussion and makes this letter a valuable addition to the literature on cutaneous metastatic carcinoma, particularly metastatic salivary duct carcinoma.

Xintong Wang, MD; William H. Westra, MD

From the Department of Pathology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

To the Editor:

We read with interest the Case Letter from Wang et al1 (Cutis. 2023;112:E13-E15) of a 60-year-old man whose metastatic salivary duct adenocarcinoma manifested with the shield sign as well as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. Cutaneous metastases have seldom been described in association with salivary duct carcinoma.2-7 In addition, carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides–associated shield sign has not been commonly reported.5,8-12

Salivary duct carcinoma—an uncommon head and neck malignancy characterized by androgen receptor expression—rarely is associated with cutaneous metastases. Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous, metastatic, salivary duct carcinoma, and/or skin, including the patient described by Wang et al,1 there have been 8 individuals with cutaneous metastases from this cancer. The morphology of the cutaneous metastases has varied from angiomatous to angiokeratomalike (black and keratotic) papules, bullae, macules (red), papules and nodules (erythematous and scaly), plaques (cellulitislike and confluent that were purpuric, hemorrhagic, and violaceous), pseudovesicles, purpuric papules, subcutaneous nodules, and an ulcer (superficial and mimicked a basal cell carcinoma).1-7 Remarkably, 4 of 8 patients (50%) with salivary duct carcinoma cutaneous metastases presented with a shield sign,5,7 including the case reported by Wang et al.1

The shield sign is a distinctive clinical manifestation of cutaneous metastasis.10 It was named to describe the skin metastases located predominantly on the chest area that would be covered by a medieval knight’s shield5,10,12; metastatic lesions also have been noted on the proximal arm and/or the upper back in a similar distribution.8,9 To date, based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms breast cancer, carcinoma, hemorrhagiectoides, metastases, salivary duct carcinoma, shield, and/or sign, the shield sign has been described in 6 patients with cutaneous metastases either from salivary duct carcinoma (4 patients)1,5,7 or breast cancer (2 patients).8,9 The shield sign pathologically corresponds to carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides, an inflammatory pattern of cutaneous metastases.5,11

Inflammatory cutaneous metastatic carcinoma has 3 distinctive clinical and pathologic manifestations.11 Carcinoma erysipelatoides and carcinoma telangiectoides were the earlier described variants.11 In 2012, carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides was described as the third pattern of inflammatory cutaneous metastasis.5

Carcinoma erysipelatoides, which clinically mimics cutaneous streptococcal cellulitis, appears as a well-defined erythematous patch or plaque; the tumor cells can be found in the lymphatic vessels and either are absent or minimally present in the dermis. Carcinoma telangiectoides, which clinically mimics idiopathic telangiectases, appears as an erythematous patch with prominent telangiectases; the tumor cells can be found in the blood vessels and are either absent or minimally present in the dermis. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides appears as purpuric or violaceous indurated plaques; the tumor cells are not only found in the blood vessels, in the lymphatic vessels, or both, but also can be mildly to extensively present in the dermis.5,10,11

In conclusion, the shield sign is a unique presentation of inflammatory cutaneous metastatic carcinoma, which is associated with carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. The clinical features of the infiltrated plaques correspond to the presence of tumor cells in the blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and the dermis; in addition, the purpuric and violaceous appearance correlates with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes or hemorrhage in the dermis. To date, half of the patients with skin metastases from salivary duct carcinoma have presented with carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides–associated shield sign.

Authors’ Response

We appreciate and welcome the comments provided by the authors. Drawing attention to unusual pathologic manifestations of cutaneous metastatic salivary duct carcinoma manifesting with the shield sign, the authors present a comprehensive review of 3 distinctive presentations: carcinoma erysipelatoides, carcinoma telangiectoides, and carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. The inclusion of these variants enriches the discussion and makes this letter a valuable addition to the literature on cutaneous metastatic carcinoma, particularly metastatic salivary duct carcinoma.

Xintong Wang, MD; William H. Westra, MD

From the Department of Pathology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

- Wang X, Vyas NS, Alghamdi AA, et al. Cutaneous presentation of metastatic salivary duct carcinoma. Cutis. 2023;112:E13-E15.

- Pollock JL, Catalano E. Metastatic ductal carcinoma of the parotid gland in a patient with sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1098-1099.

- Pollock JL. Metastatic carcinoma of the parotid gland resembling carcinoma of the breast. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:1093.

- Aygit AC, Top H, Cakir B, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma of the parotid gland metastasizing to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:48-50.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The “shield sign” in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Chakari W, Andersen L, Anderson JL. Cutaneous metastases from salivary duct carcinoma of the submandibular gland. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:254-258.

- Shin JY, Eun DH, Lee JY, et al. A case of cutaneous metastases of salivary duct carcinoma mimicking radiation recall dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2020;32:436-438.

- Aravena RC, Aravena DC, Velasco MJ, et al. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides: case report of an uncommon presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3hn3z850.

- Smith KA, Basko-Plluska J, Kothari AD, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2020;105:E20-E22.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Cutaneous metastatic cancer: carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides presenting as the shield sign. Cureus. 2021;13:e12627.

- Cohen PR. Pleomorphic appearance of breast cancer cutaneous metastases. Cureus. 2021;13:e20301.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Kurzrock R. Tumor lysis syndrome: introduction of a cutaneous variant and a new classification system. Cureus. 2021;13:e13816.

- Wang X, Vyas NS, Alghamdi AA, et al. Cutaneous presentation of metastatic salivary duct carcinoma. Cutis. 2023;112:E13-E15.

- Pollock JL, Catalano E. Metastatic ductal carcinoma of the parotid gland in a patient with sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1098-1099.

- Pollock JL. Metastatic carcinoma of the parotid gland resembling carcinoma of the breast. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:1093.

- Aygit AC, Top H, Cakir B, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma of the parotid gland metastasizing to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:48-50.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The “shield sign” in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Chakari W, Andersen L, Anderson JL. Cutaneous metastases from salivary duct carcinoma of the submandibular gland. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:254-258.

- Shin JY, Eun DH, Lee JY, et al. A case of cutaneous metastases of salivary duct carcinoma mimicking radiation recall dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2020;32:436-438.

- Aravena RC, Aravena DC, Velasco MJ, et al. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides: case report of an uncommon presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3hn3z850.

- Smith KA, Basko-Plluska J, Kothari AD, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2020;105:E20-E22.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Cutaneous metastatic cancer: carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides presenting as the shield sign. Cureus. 2021;13:e12627.

- Cohen PR. Pleomorphic appearance of breast cancer cutaneous metastases. Cureus. 2021;13:e20301.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Kurzrock R. Tumor lysis syndrome: introduction of a cutaneous variant and a new classification system. Cureus. 2021;13:e13816.

Cutaneous Metastases Masquerading as Solitary or Multiple Keratoacanthomas

To the Editor:

We read with interest the excellent Cutis articles on cutaneous metastases by Tarantino et al1 and Agnetta et al.2 Tarantino et al1 reported a 59-year-old man who developed cutaneous metastases on the scalp from an esophageal adenocarcinoma. Agnetta et al2 described a 76-year-old woman with metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.

Cutaneous metastases are not common. They may herald the unsuspected diagnosis of a solid tumor recurrence or progression of systemic disease in an oncology patient. Occasionally, they are the primary manifestation of a visceral tumor in a previously cancer-free patient. Less often, skin lesions are the manifestation of a new or recurrent hematologic malignancy.3,4

The morphology of cutaneous metastases is variable. Most commonly they appear as papules and nodules. However, they can mimic bacterial (eg, erysipelas) and viral (eg, herpes zoster) infections or present as scalp alopecia.5-7

Cutaneous metastases also can mimic benign (eg, epidermoid cysts) or malignant (eg, keratoacanthoma) neoplasms. Keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases are rare.8 They can present as single or multiple tumors.9,10

In the case reported by Tarantino et al,1 the patient had a history of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. His unsuspected recurrence presented not only with a single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastasis on the scalp but also with another metastasis-related scalp lesion that appeared as a smooth pearly papule. We also observed a 53-year-old man whose metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma presented with a keratoacanthomalike nodule on the right upper lip; additionally, the patient had other cutaneous metastases that appeared as an erythematous papule on the forehead and a cystic nodule on the scalp.8 Other investigators also observed a single keratoacanthomalike lesion on the left cheek of a 49-year-old man with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma.11

Agnetta et al2 described a patient with a history of malignant melanoma on the left upper back that had been excised 2 years prior. She presented with the eruptive onset of multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases on the chest, back, and right arm.2 The important observation of metastatic malignant melanoma presenting as multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases pointed out by Agnetta et al2 confirms a similar occurrence reported by Reed et al12 in a patient with metastatic malignant melanoma.

We also previously reported the case of a 68-year-old man with metastatic laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) who developed more than 10 keratoacanthomalike nodules within a radiation port that extended from the face to the mid chest.10 In addition, other researchers have noted a similar phenomenon of keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.13 Gil et al14 described a 40-year-old woman whose metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor initially presented as 11 keratoacanthomalike scalp nodules; interestingly, the first nodule spontaneously regressed. Araghi et al15 reported a 58-year-old woman--with a stable SCC of the larynx that had been diagnosed 2 years prior and treated with chemoradiotherapy--in whom cancer progression presented as multiple keratoacanthomalike lesions in an area of prior radiotherapy.

In conclusion, cutaneous metastases presenting as new-onset solitary or multiple keratoacanthomalike nodules in either a cancer-free individual or a patient with a prior history of a visceral malignancy is uncommon. Although the clinical features mimic those of a single or eruptive keratoacanthomas, a biopsy will readily establish the diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic cancer. Metastatic esophageal carcinoma--either adenocarcinoma or SCC--can present, albeit rarely, with cutaneous lesions that can have various morphologies.8 Whether there is an increased predilection for patients with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma to present with single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases with or without concurrent additional skin lesions of cutaneous metastases of other morphologies remains to be determined.

- Tarantino IS, Tennill T, Fraga G, et al. Cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma on the scalp. Cutis. 2020;105:E3-E5.

- Agnetta V, Hamstra A, Hirokane J, et al. Metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas. Cutis. 2020;105:E29-E31.

- Cohen PR. Skin clues to primary and metastatic malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 1995;51:1199-1204.

- Cohen PR. Leukemia cutis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. Cutis. 2019;103:212.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The "shield sign" in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Manteaux A, Cohen PR, Rapini RP. Zosteriform and epidermotropic metastasis. report of two cases. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:97-100.

- Conner KB, Cohen PR. Cutaneous metastases of breast carcinoma presenting as alopecia neoplastica. South Med J. 2009;102:385-389.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Malignancies with skin lesions mimicking keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20397.

- Ellis DL, Riahi RR, Murina AT, et al. Metastatic laryngeal carcinoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas: report of keratoacanthoma-like cutaneous metastases in a radiation port. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt3s43b81f.

- Hani AC, Nuñez E, Cuellar I, et al. Cutaneous metastases as a manifestation of esophageal adenocarcinoma recurrence: a case report [published online September 5, 2019]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. doi:10.1016/j.rgmx.2019.06.002.

- Reed KB, Cook-Norris RH, Brewer JD. The cutaneous manifestations of metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:243-249.

- Cohen PR, Riahi RR. Cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E320-E322.

- Gil F, Elvas L, Raposo S, et al. Keratoacanthoma-like nodules as first manifestation of metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25. pii:13030/qt9xx6p2tt.

- Araghi F, Fatemi A, Rakhshan A, et al. Skin metastasis of laryngeal carcinoma presenting as multiple eruptive nodules [published online February 10, 2020]. Head Neck Pathol. doi:10.1007/s12105-020-01143-1.

To the Editor:

We read with interest the excellent Cutis articles on cutaneous metastases by Tarantino et al1 and Agnetta et al.2 Tarantino et al1 reported a 59-year-old man who developed cutaneous metastases on the scalp from an esophageal adenocarcinoma. Agnetta et al2 described a 76-year-old woman with metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.

Cutaneous metastases are not common. They may herald the unsuspected diagnosis of a solid tumor recurrence or progression of systemic disease in an oncology patient. Occasionally, they are the primary manifestation of a visceral tumor in a previously cancer-free patient. Less often, skin lesions are the manifestation of a new or recurrent hematologic malignancy.3,4

The morphology of cutaneous metastases is variable. Most commonly they appear as papules and nodules. However, they can mimic bacterial (eg, erysipelas) and viral (eg, herpes zoster) infections or present as scalp alopecia.5-7

Cutaneous metastases also can mimic benign (eg, epidermoid cysts) or malignant (eg, keratoacanthoma) neoplasms. Keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases are rare.8 They can present as single or multiple tumors.9,10

In the case reported by Tarantino et al,1 the patient had a history of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. His unsuspected recurrence presented not only with a single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastasis on the scalp but also with another metastasis-related scalp lesion that appeared as a smooth pearly papule. We also observed a 53-year-old man whose metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma presented with a keratoacanthomalike nodule on the right upper lip; additionally, the patient had other cutaneous metastases that appeared as an erythematous papule on the forehead and a cystic nodule on the scalp.8 Other investigators also observed a single keratoacanthomalike lesion on the left cheek of a 49-year-old man with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma.11

Agnetta et al2 described a patient with a history of malignant melanoma on the left upper back that had been excised 2 years prior. She presented with the eruptive onset of multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases on the chest, back, and right arm.2 The important observation of metastatic malignant melanoma presenting as multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases pointed out by Agnetta et al2 confirms a similar occurrence reported by Reed et al12 in a patient with metastatic malignant melanoma.

We also previously reported the case of a 68-year-old man with metastatic laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) who developed more than 10 keratoacanthomalike nodules within a radiation port that extended from the face to the mid chest.10 In addition, other researchers have noted a similar phenomenon of keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.13 Gil et al14 described a 40-year-old woman whose metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor initially presented as 11 keratoacanthomalike scalp nodules; interestingly, the first nodule spontaneously regressed. Araghi et al15 reported a 58-year-old woman--with a stable SCC of the larynx that had been diagnosed 2 years prior and treated with chemoradiotherapy--in whom cancer progression presented as multiple keratoacanthomalike lesions in an area of prior radiotherapy.

In conclusion, cutaneous metastases presenting as new-onset solitary or multiple keratoacanthomalike nodules in either a cancer-free individual or a patient with a prior history of a visceral malignancy is uncommon. Although the clinical features mimic those of a single or eruptive keratoacanthomas, a biopsy will readily establish the diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic cancer. Metastatic esophageal carcinoma--either adenocarcinoma or SCC--can present, albeit rarely, with cutaneous lesions that can have various morphologies.8 Whether there is an increased predilection for patients with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma to present with single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases with or without concurrent additional skin lesions of cutaneous metastases of other morphologies remains to be determined.

To the Editor:

We read with interest the excellent Cutis articles on cutaneous metastases by Tarantino et al1 and Agnetta et al.2 Tarantino et al1 reported a 59-year-old man who developed cutaneous metastases on the scalp from an esophageal adenocarcinoma. Agnetta et al2 described a 76-year-old woman with metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.

Cutaneous metastases are not common. They may herald the unsuspected diagnosis of a solid tumor recurrence or progression of systemic disease in an oncology patient. Occasionally, they are the primary manifestation of a visceral tumor in a previously cancer-free patient. Less often, skin lesions are the manifestation of a new or recurrent hematologic malignancy.3,4

The morphology of cutaneous metastases is variable. Most commonly they appear as papules and nodules. However, they can mimic bacterial (eg, erysipelas) and viral (eg, herpes zoster) infections or present as scalp alopecia.5-7

Cutaneous metastases also can mimic benign (eg, epidermoid cysts) or malignant (eg, keratoacanthoma) neoplasms. Keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases are rare.8 They can present as single or multiple tumors.9,10

In the case reported by Tarantino et al,1 the patient had a history of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. His unsuspected recurrence presented not only with a single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastasis on the scalp but also with another metastasis-related scalp lesion that appeared as a smooth pearly papule. We also observed a 53-year-old man whose metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma presented with a keratoacanthomalike nodule on the right upper lip; additionally, the patient had other cutaneous metastases that appeared as an erythematous papule on the forehead and a cystic nodule on the scalp.8 Other investigators also observed a single keratoacanthomalike lesion on the left cheek of a 49-year-old man with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma.11

Agnetta et al2 described a patient with a history of malignant melanoma on the left upper back that had been excised 2 years prior. She presented with the eruptive onset of multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases on the chest, back, and right arm.2 The important observation of metastatic malignant melanoma presenting as multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases pointed out by Agnetta et al2 confirms a similar occurrence reported by Reed et al12 in a patient with metastatic malignant melanoma.

We also previously reported the case of a 68-year-old man with metastatic laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) who developed more than 10 keratoacanthomalike nodules within a radiation port that extended from the face to the mid chest.10 In addition, other researchers have noted a similar phenomenon of keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.13 Gil et al14 described a 40-year-old woman whose metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor initially presented as 11 keratoacanthomalike scalp nodules; interestingly, the first nodule spontaneously regressed. Araghi et al15 reported a 58-year-old woman--with a stable SCC of the larynx that had been diagnosed 2 years prior and treated with chemoradiotherapy--in whom cancer progression presented as multiple keratoacanthomalike lesions in an area of prior radiotherapy.

In conclusion, cutaneous metastases presenting as new-onset solitary or multiple keratoacanthomalike nodules in either a cancer-free individual or a patient with a prior history of a visceral malignancy is uncommon. Although the clinical features mimic those of a single or eruptive keratoacanthomas, a biopsy will readily establish the diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic cancer. Metastatic esophageal carcinoma--either adenocarcinoma or SCC--can present, albeit rarely, with cutaneous lesions that can have various morphologies.8 Whether there is an increased predilection for patients with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma to present with single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases with or without concurrent additional skin lesions of cutaneous metastases of other morphologies remains to be determined.

- Tarantino IS, Tennill T, Fraga G, et al. Cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma on the scalp. Cutis. 2020;105:E3-E5.

- Agnetta V, Hamstra A, Hirokane J, et al. Metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas. Cutis. 2020;105:E29-E31.

- Cohen PR. Skin clues to primary and metastatic malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 1995;51:1199-1204.

- Cohen PR. Leukemia cutis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. Cutis. 2019;103:212.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The "shield sign" in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Manteaux A, Cohen PR, Rapini RP. Zosteriform and epidermotropic metastasis. report of two cases. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:97-100.

- Conner KB, Cohen PR. Cutaneous metastases of breast carcinoma presenting as alopecia neoplastica. South Med J. 2009;102:385-389.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Malignancies with skin lesions mimicking keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20397.

- Ellis DL, Riahi RR, Murina AT, et al. Metastatic laryngeal carcinoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas: report of keratoacanthoma-like cutaneous metastases in a radiation port. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt3s43b81f.

- Hani AC, Nuñez E, Cuellar I, et al. Cutaneous metastases as a manifestation of esophageal adenocarcinoma recurrence: a case report [published online September 5, 2019]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. doi:10.1016/j.rgmx.2019.06.002.

- Reed KB, Cook-Norris RH, Brewer JD. The cutaneous manifestations of metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:243-249.

- Cohen PR, Riahi RR. Cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E320-E322.

- Gil F, Elvas L, Raposo S, et al. Keratoacanthoma-like nodules as first manifestation of metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25. pii:13030/qt9xx6p2tt.

- Araghi F, Fatemi A, Rakhshan A, et al. Skin metastasis of laryngeal carcinoma presenting as multiple eruptive nodules [published online February 10, 2020]. Head Neck Pathol. doi:10.1007/s12105-020-01143-1.

- Tarantino IS, Tennill T, Fraga G, et al. Cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma on the scalp. Cutis. 2020;105:E3-E5.

- Agnetta V, Hamstra A, Hirokane J, et al. Metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas. Cutis. 2020;105:E29-E31.

- Cohen PR. Skin clues to primary and metastatic malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 1995;51:1199-1204.

- Cohen PR. Leukemia cutis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. Cutis. 2019;103:212.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The "shield sign" in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Manteaux A, Cohen PR, Rapini RP. Zosteriform and epidermotropic metastasis. report of two cases. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:97-100.

- Conner KB, Cohen PR. Cutaneous metastases of breast carcinoma presenting as alopecia neoplastica. South Med J. 2009;102:385-389.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Malignancies with skin lesions mimicking keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20397.

- Ellis DL, Riahi RR, Murina AT, et al. Metastatic laryngeal carcinoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas: report of keratoacanthoma-like cutaneous metastases in a radiation port. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt3s43b81f.

- Hani AC, Nuñez E, Cuellar I, et al. Cutaneous metastases as a manifestation of esophageal adenocarcinoma recurrence: a case report [published online September 5, 2019]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. doi:10.1016/j.rgmx.2019.06.002.

- Reed KB, Cook-Norris RH, Brewer JD. The cutaneous manifestations of metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:243-249.

- Cohen PR, Riahi RR. Cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E320-E322.

- Gil F, Elvas L, Raposo S, et al. Keratoacanthoma-like nodules as first manifestation of metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25. pii:13030/qt9xx6p2tt.

- Araghi F, Fatemi A, Rakhshan A, et al. Skin metastasis of laryngeal carcinoma presenting as multiple eruptive nodules [published online February 10, 2020]. Head Neck Pathol. doi:10.1007/s12105-020-01143-1.

Addressing Health Literacy for Miscommunication in Dermatology

To the Editor:

We read with interest the Cutis Resident Corner column by Tracey1 on miscommunication with dermatology patients in which the author highlighted how seemingly straightforward language can deceivingly complicate effective communication between dermatologists and their patients. The examples she provided, including subtleties in describing what constitutes the “affected area” for proper application of a topical treatment or the inconsistent use of trade names for medications, underscore how misperceptions of verbal instruction can lead to poor treatment adherence and unintended health outcomes.1

In addition to how dermatologists deliver treatment information to their patients, a broader aspect of physician-patient communication is health literacy, which is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”2 Health literacy involves reading, listening, numeracy, decision-making, and health knowledge; patients who are potentially at risk for having limited skills in these areas include the elderly, those with poor English language proficiency, and those of lower socioeconomic status.3

In 2003, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy found that only 12% of individuals older than 16 years had a proficient level of health literacy.4 In an effort to address gaps in communication between health care providers and patients, the American Medical Association, National Institutes of Health, and the US Department of Health & Human Services recommend that educational materials be written at no higher than a 6th grade reading level.5,6 Currently, only 2% of dermatology educational materials meet this recommendation; the average reading level of patient dermatology materials is at a 12th grade level, despite the average American adult reading at an 8th grade level.7

It is imperative that dermatologists seek to improve both their verbal and nonverbal communication skills to effectively reach a broader patient population. Visual cues, such as pamphlets to illustrate what is meant by a “pea-sized” amount of adapalene or a photograph demonstrating “border asymmetry” in a melanoma, may be more effective than verbal or written communication alone. In addition, when certain drugs or treatments may be called by various names or when different drug names sound similar

The visual nature of dermatology creates unique psychosocial scenarios that may inherently motivate patients to understand their cutaneous disease; for example, providing photographs that depict acne improvement at different time points throughout isotretinoin treatment allows for more realistic expectations during therapy. Therefore, it is only fitting that instructive imagery would serve to benefit patient education.

In conclusion, communication between dermatologists and their patients involves multiple variables that can contribute to successful patient instruction for the management of dermatologic disease. Indeed, successful interaction not only includes mutual awareness of words or phrases that can otherwise be misconstrued but also attention to the readability of written materials and the benefits of visual instruction in the clinic setting. Integrating these aspects of health literacy can optimize rapport, treatment adherence, and health outcomes.

- Tracey E. Miscommunication with dermatology patients: are we speaking the same language? Cutis. 2018;102:E27-E28.

- Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, et al, eds. National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy; Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004.

- Kutner M, Greenberg E, Baer J. A First Look at the Literacy of America’s Adults in the 21st Century. Jessup, MD: National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences; 2006. http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2006470. Published December 15, 2005. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003.

- How to write easy-to-read health materials. National Library of Medicine website. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/etr.html. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Prabhu AV, Gupta R, Kim C, et al. Patient education materials in dermatology: addressing the health literacy needs of patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:946-947.

To the Editor:

We read with interest the Cutis Resident Corner column by Tracey1 on miscommunication with dermatology patients in which the author highlighted how seemingly straightforward language can deceivingly complicate effective communication between dermatologists and their patients. The examples she provided, including subtleties in describing what constitutes the “affected area” for proper application of a topical treatment or the inconsistent use of trade names for medications, underscore how misperceptions of verbal instruction can lead to poor treatment adherence and unintended health outcomes.1

In addition to how dermatologists deliver treatment information to their patients, a broader aspect of physician-patient communication is health literacy, which is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”2 Health literacy involves reading, listening, numeracy, decision-making, and health knowledge; patients who are potentially at risk for having limited skills in these areas include the elderly, those with poor English language proficiency, and those of lower socioeconomic status.3

In 2003, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy found that only 12% of individuals older than 16 years had a proficient level of health literacy.4 In an effort to address gaps in communication between health care providers and patients, the American Medical Association, National Institutes of Health, and the US Department of Health & Human Services recommend that educational materials be written at no higher than a 6th grade reading level.5,6 Currently, only 2% of dermatology educational materials meet this recommendation; the average reading level of patient dermatology materials is at a 12th grade level, despite the average American adult reading at an 8th grade level.7

It is imperative that dermatologists seek to improve both their verbal and nonverbal communication skills to effectively reach a broader patient population. Visual cues, such as pamphlets to illustrate what is meant by a “pea-sized” amount of adapalene or a photograph demonstrating “border asymmetry” in a melanoma, may be more effective than verbal or written communication alone. In addition, when certain drugs or treatments may be called by various names or when different drug names sound similar

The visual nature of dermatology creates unique psychosocial scenarios that may inherently motivate patients to understand their cutaneous disease; for example, providing photographs that depict acne improvement at different time points throughout isotretinoin treatment allows for more realistic expectations during therapy. Therefore, it is only fitting that instructive imagery would serve to benefit patient education.

In conclusion, communication between dermatologists and their patients involves multiple variables that can contribute to successful patient instruction for the management of dermatologic disease. Indeed, successful interaction not only includes mutual awareness of words or phrases that can otherwise be misconstrued but also attention to the readability of written materials and the benefits of visual instruction in the clinic setting. Integrating these aspects of health literacy can optimize rapport, treatment adherence, and health outcomes.

To the Editor:

We read with interest the Cutis Resident Corner column by Tracey1 on miscommunication with dermatology patients in which the author highlighted how seemingly straightforward language can deceivingly complicate effective communication between dermatologists and their patients. The examples she provided, including subtleties in describing what constitutes the “affected area” for proper application of a topical treatment or the inconsistent use of trade names for medications, underscore how misperceptions of verbal instruction can lead to poor treatment adherence and unintended health outcomes.1

In addition to how dermatologists deliver treatment information to their patients, a broader aspect of physician-patient communication is health literacy, which is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”2 Health literacy involves reading, listening, numeracy, decision-making, and health knowledge; patients who are potentially at risk for having limited skills in these areas include the elderly, those with poor English language proficiency, and those of lower socioeconomic status.3

In 2003, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy found that only 12% of individuals older than 16 years had a proficient level of health literacy.4 In an effort to address gaps in communication between health care providers and patients, the American Medical Association, National Institutes of Health, and the US Department of Health & Human Services recommend that educational materials be written at no higher than a 6th grade reading level.5,6 Currently, only 2% of dermatology educational materials meet this recommendation; the average reading level of patient dermatology materials is at a 12th grade level, despite the average American adult reading at an 8th grade level.7

It is imperative that dermatologists seek to improve both their verbal and nonverbal communication skills to effectively reach a broader patient population. Visual cues, such as pamphlets to illustrate what is meant by a “pea-sized” amount of adapalene or a photograph demonstrating “border asymmetry” in a melanoma, may be more effective than verbal or written communication alone. In addition, when certain drugs or treatments may be called by various names or when different drug names sound similar

The visual nature of dermatology creates unique psychosocial scenarios that may inherently motivate patients to understand their cutaneous disease; for example, providing photographs that depict acne improvement at different time points throughout isotretinoin treatment allows for more realistic expectations during therapy. Therefore, it is only fitting that instructive imagery would serve to benefit patient education.

In conclusion, communication between dermatologists and their patients involves multiple variables that can contribute to successful patient instruction for the management of dermatologic disease. Indeed, successful interaction not only includes mutual awareness of words or phrases that can otherwise be misconstrued but also attention to the readability of written materials and the benefits of visual instruction in the clinic setting. Integrating these aspects of health literacy can optimize rapport, treatment adherence, and health outcomes.

- Tracey E. Miscommunication with dermatology patients: are we speaking the same language? Cutis. 2018;102:E27-E28.

- Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, et al, eds. National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy; Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004.

- Kutner M, Greenberg E, Baer J. A First Look at the Literacy of America’s Adults in the 21st Century. Jessup, MD: National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences; 2006. http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2006470. Published December 15, 2005. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003.

- How to write easy-to-read health materials. National Library of Medicine website. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/etr.html. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Prabhu AV, Gupta R, Kim C, et al. Patient education materials in dermatology: addressing the health literacy needs of patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:946-947.

- Tracey E. Miscommunication with dermatology patients: are we speaking the same language? Cutis. 2018;102:E27-E28.

- Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, et al, eds. National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy; Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004.

- Kutner M, Greenberg E, Baer J. A First Look at the Literacy of America’s Adults in the 21st Century. Jessup, MD: National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences; 2006. http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2006470. Published December 15, 2005. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003.

- How to write easy-to-read health materials. National Library of Medicine website. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/etr.html. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Prabhu AV, Gupta R, Kim C, et al. Patient education materials in dermatology: addressing the health literacy needs of patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:946-947.

Leukemia Cutis–Associated Leonine Facies and Eyebrow Loss

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5

The eyebrow loss associated with leonine facies often is not reversible once the causative cell of the associated condition (eg, granulomas of mycobacteria-infected histiocytes in leprosy, neoplastic lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) has infiltrated the area of the eyebrows and abolished the preexisting hair follicles; however, follow-up descriptions of patients after treatment of other conditions that cause eyebrow loss usually are not reported. Indeed, there was partial reappearance of the eyebrows in a woman with systemic mastocytosis–associated loss of the eyebrows after malignancy-related treatment was reinitiated and the infiltrative facial plaques that had created her leonine facies had decreased in size.5 It is reasonable to speculate that the eyebrows may have reappeared in the patient reported by Krooks and Weatherall1 and his leonine facies–associated facial plaques may have resolved if he had underwent and responded to treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Jin CC, Martinelli PT, Cohen PR. What are these erythematous skin lesions? leukemia cutis. The Dermatologist. 2012;20:46-50.

- Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Systemic mastocytosis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. South Med J. 2011;104:236-238.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Beran M. Infiltrated blue-gray plaques in a patient with leukemia. Chloroma (granulocytic sarcoma). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:251, 254.

- Cohen PR. Leonine facies associated with eyebrow loss. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e148-e149.

- Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Actinic reticuloid presented as facies leonine. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:234-236.

- Jacob Raja SA, Raja JJ, Vijayashree R, et al. Evaluation of oral and periodontal status of leprosy patients in Dindigul district. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(suppl 1):S119-S121.

- McGaughran J, Aftimos S. Setleis syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:376-380.

- Benoit T, Bacelieri R, Morrell DS, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia of immunosuppression: report of a pediatric patient with response to oral valganciclovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:871-874.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5

The eyebrow loss associated with leonine facies often is not reversible once the causative cell of the associated condition (eg, granulomas of mycobacteria-infected histiocytes in leprosy, neoplastic lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) has infiltrated the area of the eyebrows and abolished the preexisting hair follicles; however, follow-up descriptions of patients after treatment of other conditions that cause eyebrow loss usually are not reported. Indeed, there was partial reappearance of the eyebrows in a woman with systemic mastocytosis–associated loss of the eyebrows after malignancy-related treatment was reinitiated and the infiltrative facial plaques that had created her leonine facies had decreased in size.5 It is reasonable to speculate that the eyebrows may have reappeared in the patient reported by Krooks and Weatherall1 and his leonine facies–associated facial plaques may have resolved if he had underwent and responded to treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5

The eyebrow loss associated with leonine facies often is not reversible once the causative cell of the associated condition (eg, granulomas of mycobacteria-infected histiocytes in leprosy, neoplastic lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) has infiltrated the area of the eyebrows and abolished the preexisting hair follicles; however, follow-up descriptions of patients after treatment of other conditions that cause eyebrow loss usually are not reported. Indeed, there was partial reappearance of the eyebrows in a woman with systemic mastocytosis–associated loss of the eyebrows after malignancy-related treatment was reinitiated and the infiltrative facial plaques that had created her leonine facies had decreased in size.5 It is reasonable to speculate that the eyebrows may have reappeared in the patient reported by Krooks and Weatherall1 and his leonine facies–associated facial plaques may have resolved if he had underwent and responded to treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Jin CC, Martinelli PT, Cohen PR. What are these erythematous skin lesions? leukemia cutis. The Dermatologist. 2012;20:46-50.

- Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Systemic mastocytosis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. South Med J. 2011;104:236-238.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Beran M. Infiltrated blue-gray plaques in a patient with leukemia. Chloroma (granulocytic sarcoma). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:251, 254.

- Cohen PR. Leonine facies associated with eyebrow loss. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e148-e149.

- Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Actinic reticuloid presented as facies leonine. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:234-236.

- Jacob Raja SA, Raja JJ, Vijayashree R, et al. Evaluation of oral and periodontal status of leprosy patients in Dindigul district. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(suppl 1):S119-S121.

- McGaughran J, Aftimos S. Setleis syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:376-380.

- Benoit T, Bacelieri R, Morrell DS, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia of immunosuppression: report of a pediatric patient with response to oral valganciclovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:871-874.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Jin CC, Martinelli PT, Cohen PR. What are these erythematous skin lesions? leukemia cutis. The Dermatologist. 2012;20:46-50.

- Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Systemic mastocytosis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. South Med J. 2011;104:236-238.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Beran M. Infiltrated blue-gray plaques in a patient with leukemia. Chloroma (granulocytic sarcoma). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:251, 254.

- Cohen PR. Leonine facies associated with eyebrow loss. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e148-e149.

- Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Actinic reticuloid presented as facies leonine. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:234-236.

- Jacob Raja SA, Raja JJ, Vijayashree R, et al. Evaluation of oral and periodontal status of leprosy patients in Dindigul district. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(suppl 1):S119-S121.

- McGaughran J, Aftimos S. Setleis syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:376-380.

- Benoit T, Bacelieri R, Morrell DS, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia of immunosuppression: report of a pediatric patient with response to oral valganciclovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:871-874.

Vaginal and Scrotal Rejuvenation: The Potential Role of Dermatologists in Genital Rejuvenation

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis article by Hashim et al,1 which not only summarized the key features of vaginal rejuvenation but also concisely reviewed noninvasive treatments, including lasers and radiofrequency devices, that can be used to address this important issue. The authors emphasized that these treatments may represent a valuable addition to the cosmetic landscape. In addition, they also asserted that noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation is an expanding focus of cosmetic dermatology.1

Genital rejuvenation includes rejuvenation of the vagina in women and the scrotum in men. Since the term initially appeared in the literature in 2007,2 a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE yields an increasing number of articles on vaginal rejuvenation. More recently, the concept of scrotal rejuvenation was introduced in 2018.3

Similar to vaginal rejuvenation, scrotal rejuvenation includes procedures to remedy medical or cosmetic conditions of the scrotum. Hashim et al1 focused on morphology-associated vaginal changes for which rejuvenation techniques have been successful, such as excess clitoral hood; excess labia majora or minora; vaginal laxity; and vulvovaginal atrophy, which is considered to be a component of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Morphology-associated changes of the scrotum include wrinkling (cutis scrotum gyratum or scrotum rugosum) and laxity (low-hanging or sagging scrotum or scrotomegaly

Intrinsic (aging) and extrinsic (trauma) alterations also can result in other changes that may be amenable to vaginal or scrotal rejuvenation; for example, in addition to changes in morphology, there are hair (eg, alopecia, hypertrichosis) and vascular (eg, angiokeratomas) conditions of the vagina and scrotum that may be suitable for rejuvenation.3-5 Dermatologists have the opportunity to provide treatment for the genital rejuvenation of their patients.

- Hashim PW, Nia JK, Zade J, et al. Noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation. Cutis. 2018;102:243-246.

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 378: vaginal “rejuvenation” and cosmetic vaginal procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:737-738.

- Cohen PR. Scrotal rejuvenation. Cureus. 2018;10:e2316.

- Cohen PR. Genital rejuvenation: the next frontier in medical and cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2018:24. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/27v774t5. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Cohen PR. A case report of scrotal rejuvenation: laser treatment of angiokeratomas of the scrotum [published online November 26, 2018]. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). doi:10.1007/s13555-018-0272-z.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis article by Hashim et al,1 which not only summarized the key features of vaginal rejuvenation but also concisely reviewed noninvasive treatments, including lasers and radiofrequency devices, that can be used to address this important issue. The authors emphasized that these treatments may represent a valuable addition to the cosmetic landscape. In addition, they also asserted that noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation is an expanding focus of cosmetic dermatology.1

Genital rejuvenation includes rejuvenation of the vagina in women and the scrotum in men. Since the term initially appeared in the literature in 2007,2 a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE yields an increasing number of articles on vaginal rejuvenation. More recently, the concept of scrotal rejuvenation was introduced in 2018.3

Similar to vaginal rejuvenation, scrotal rejuvenation includes procedures to remedy medical or cosmetic conditions of the scrotum. Hashim et al1 focused on morphology-associated vaginal changes for which rejuvenation techniques have been successful, such as excess clitoral hood; excess labia majora or minora; vaginal laxity; and vulvovaginal atrophy, which is considered to be a component of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Morphology-associated changes of the scrotum include wrinkling (cutis scrotum gyratum or scrotum rugosum) and laxity (low-hanging or sagging scrotum or scrotomegaly

Intrinsic (aging) and extrinsic (trauma) alterations also can result in other changes that may be amenable to vaginal or scrotal rejuvenation; for example, in addition to changes in morphology, there are hair (eg, alopecia, hypertrichosis) and vascular (eg, angiokeratomas) conditions of the vagina and scrotum that may be suitable for rejuvenation.3-5 Dermatologists have the opportunity to provide treatment for the genital rejuvenation of their patients.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis article by Hashim et al,1 which not only summarized the key features of vaginal rejuvenation but also concisely reviewed noninvasive treatments, including lasers and radiofrequency devices, that can be used to address this important issue. The authors emphasized that these treatments may represent a valuable addition to the cosmetic landscape. In addition, they also asserted that noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation is an expanding focus of cosmetic dermatology.1

Genital rejuvenation includes rejuvenation of the vagina in women and the scrotum in men. Since the term initially appeared in the literature in 2007,2 a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE yields an increasing number of articles on vaginal rejuvenation. More recently, the concept of scrotal rejuvenation was introduced in 2018.3

Similar to vaginal rejuvenation, scrotal rejuvenation includes procedures to remedy medical or cosmetic conditions of the scrotum. Hashim et al1 focused on morphology-associated vaginal changes for which rejuvenation techniques have been successful, such as excess clitoral hood; excess labia majora or minora; vaginal laxity; and vulvovaginal atrophy, which is considered to be a component of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Morphology-associated changes of the scrotum include wrinkling (cutis scrotum gyratum or scrotum rugosum) and laxity (low-hanging or sagging scrotum or scrotomegaly

Intrinsic (aging) and extrinsic (trauma) alterations also can result in other changes that may be amenable to vaginal or scrotal rejuvenation; for example, in addition to changes in morphology, there are hair (eg, alopecia, hypertrichosis) and vascular (eg, angiokeratomas) conditions of the vagina and scrotum that may be suitable for rejuvenation.3-5 Dermatologists have the opportunity to provide treatment for the genital rejuvenation of their patients.

- Hashim PW, Nia JK, Zade J, et al. Noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation. Cutis. 2018;102:243-246.

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 378: vaginal “rejuvenation” and cosmetic vaginal procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:737-738.

- Cohen PR. Scrotal rejuvenation. Cureus. 2018;10:e2316.

- Cohen PR. Genital rejuvenation: the next frontier in medical and cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2018:24. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/27v774t5. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Cohen PR. A case report of scrotal rejuvenation: laser treatment of angiokeratomas of the scrotum [published online November 26, 2018]. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). doi:10.1007/s13555-018-0272-z.

- Hashim PW, Nia JK, Zade J, et al. Noninvasive vaginal rejuvenation. Cutis. 2018;102:243-246.

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 378: vaginal “rejuvenation” and cosmetic vaginal procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:737-738.

- Cohen PR. Scrotal rejuvenation. Cureus. 2018;10:e2316.

- Cohen PR. Genital rejuvenation: the next frontier in medical and cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2018:24. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/27v774t5. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Cohen PR. A case report of scrotal rejuvenation: laser treatment of angiokeratomas of the scrotum [published online November 26, 2018]. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). doi:10.1007/s13555-018-0272-z.

Melasma Treatment With Oral Tranexamic Acid and a Novel Adjuvant Topical Therapy

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative article by Sheu1 published online in Cutis in February 2018, which succinctly described the pharmacologic characteristics of tranexamic acid, a synthetic lysine derivative, and its mechanism of action in the management of melasma by mitigating UV radiation-induced melanogenesis and neovascularization by inhibiting plasminogen activation. Additionally, the author summarized a study in which oral tranexamic acid was used to successfully treat melasma patients. After 4 months of treatment, 90% of 561 patients treated at a single center in Singapore demonstrated improvement in melasma severity.2 Sheu1 also discussed daily oral doses of tranexamic acid (500-1500 mg) that demonstrated improvement in melasma patients and reviewed potential adverse events (eg, abdominal pain and bloating, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism) for which patients should be screened and counseled prior to initiating treatment.

Recently, another study showed oral tranexamic acid to be an effective treatment in women with moderate to severe melasma. An important observation by the investigators was that once the initial phase of their study--250 mg of oral tranexamic acid twice daily and sunscreen applied to the face each morning and every 2 hours during daylight hours for 3 months--concluded and a second phase during which all participants only applied sunscreen for an additional 3 months, those with severe melasma lost most of their improvement.3 An adjuvant topical treatment, such as tranexamic acid or an inhibitor of tyrosinase (hydroquinone), might improve the results; however, initiating therapy with a topical agent whose mode of action is directed toward other melasma etiologic factors, such as the increased expression of estrogen receptors and vascular endothelial growth factor in affected skin, might be more beneficial.4,5

I recently proposed a novel approach for melasma management that would be appropriate as an adjuvant topical therapy for patients concurrently being treated with oral tranexamic acid.6 The therapeutic intervention utilizes active agents that specifically affect etiologic factors in the pathogenesis of melasma--estrogen and angiogenesis--that previously have not been targeted topically. Indeed, the topical agent contains an antiestrogen--either a selective estrogen receptor modulator (eg, tamoxifen, raloxifene), aromatase inhibitor (eg, anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane), or a selective estrogen receptor degrader (eg, fulvestrant)--and a vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor (eg, bevacizumab).6

In conclusion, the therapeutic armamentarium for managing patients with melasma includes topical agents, oral therapies, and physical modalities. Optimizing the approach to treating melasma patients should incorporate therapies that are specifically directed toward various etiologic factors of the condition. The concurrent use of a topical agent that contains an antiestrogen and an inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor in women with melasma who are being treated with oral tranexamic acid warrants further investigation to assess not only for enhanced but also sustained reduction in facial skin pigmentation.

- Sheu SL. Treatment of melasma using tranexamic acid: what's known and what's next. Cutis. 2018;101:E7-E8.

- Lee HC, Thng TG, Goh CL. Oral tranexamic acid (TA) in the treatment of melasma: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:385-392.