User login

Multiple Asymptomatic Dome-Shaped Papules on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

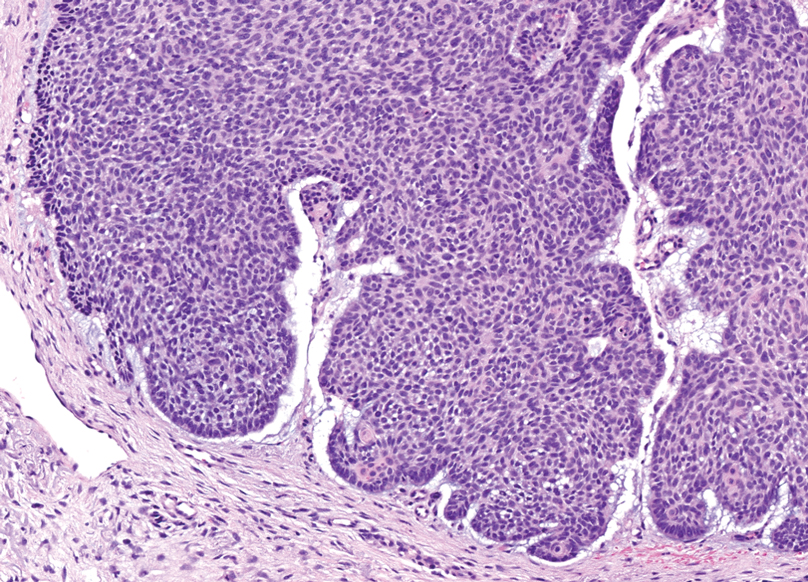

Shave biopsies of our patient’s lesions showed wellcircumscribed dermal nodules resembling a spiradenoma with 3 cell populations: those with lighter nuclei, darker nuclei, and scattered lymphocytes. However, the conspicuous globules of basement membrane material were reminiscent of a cylindroma. These overlapping features and the patient’s history of cylindroma were suggestive of a diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma.

Spiradenocylindroma is an uncommon dermal tumor with features that overlap with spiradenoma and cylindroma.1 It may manifest as a solitary lesion or multiple lesions and can occur sporadically or in the context of a family history. Histologically, it must be distinguished from other intradermal basaloid neoplasms including conventional cylindroma and spiradenoma, dermal duct tumor, hidradenoma, and trichoblastoma.

When patients present with multiple cylindromas, spiradenomas, or spiradenocylindromas, physicians should consider genetic testing and review of the family history to assess for cylindromatosis gene mutations or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Biopsy and histologic examination are important because malignant tumors can evolve from pre-existing spiradenocylindromas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas,2 with an increased risk in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.1 Our patient declined further genetic workup but continues to follow up with dermatology for monitoring of lesions.

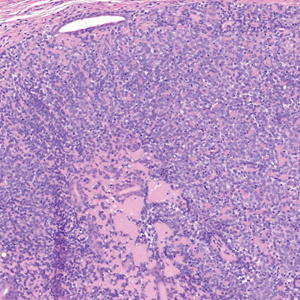

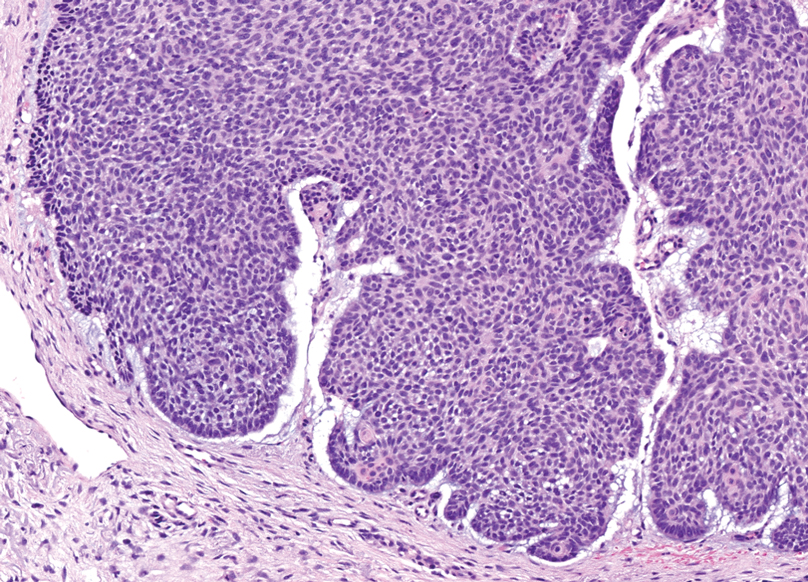

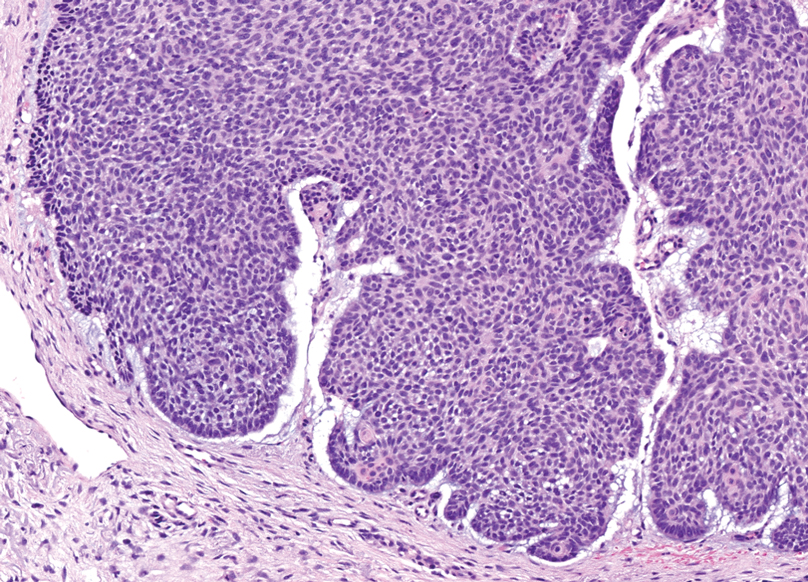

Dermal duct tumors are morphologic variants of poromas that are derived from sweat gland lineage and usually manifest as solitary dome-shaped papules, plaques, or nodules most often seen on acral surfaces as well as the head and neck.3 Clinically, they may be indistinguishable from spiradenocylindromas and require biopsy for histologic evaluation. They can be distinguished from spiradenocylindroma by the presence of small dermal nodules composed of cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm and cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).

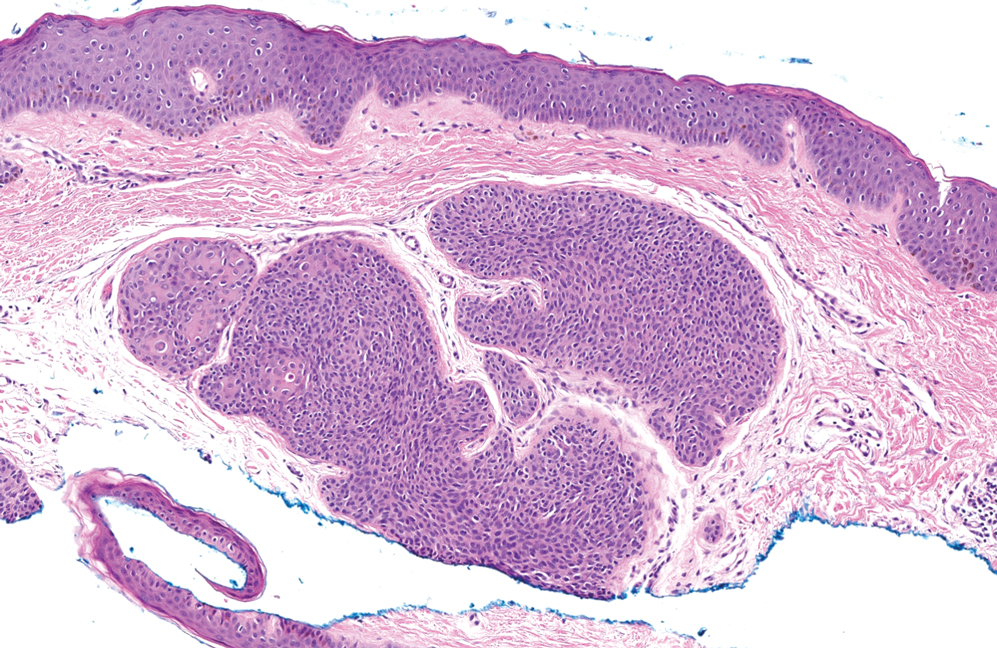

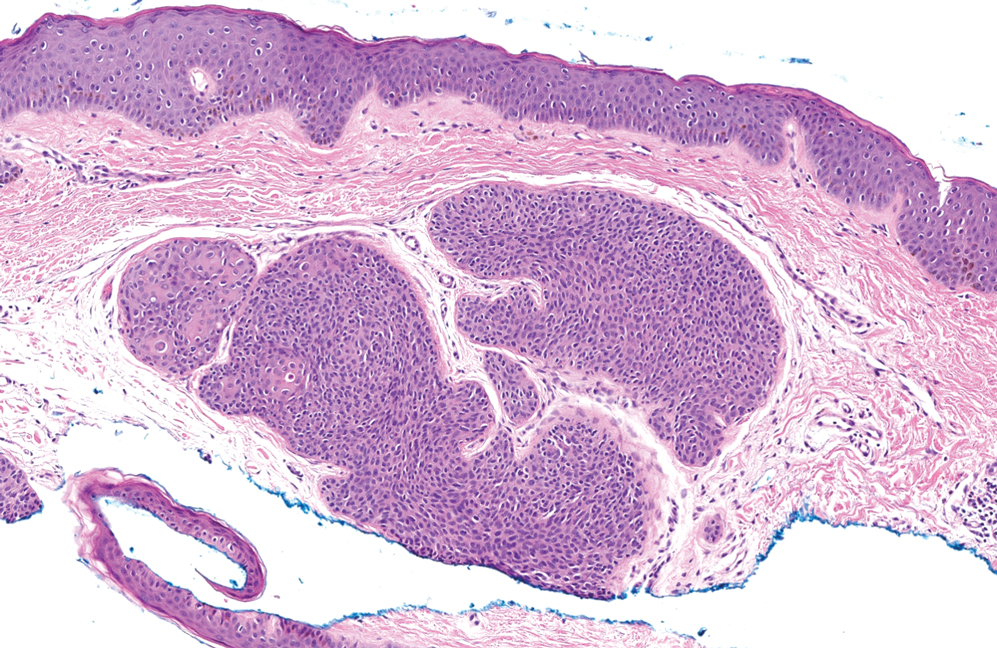

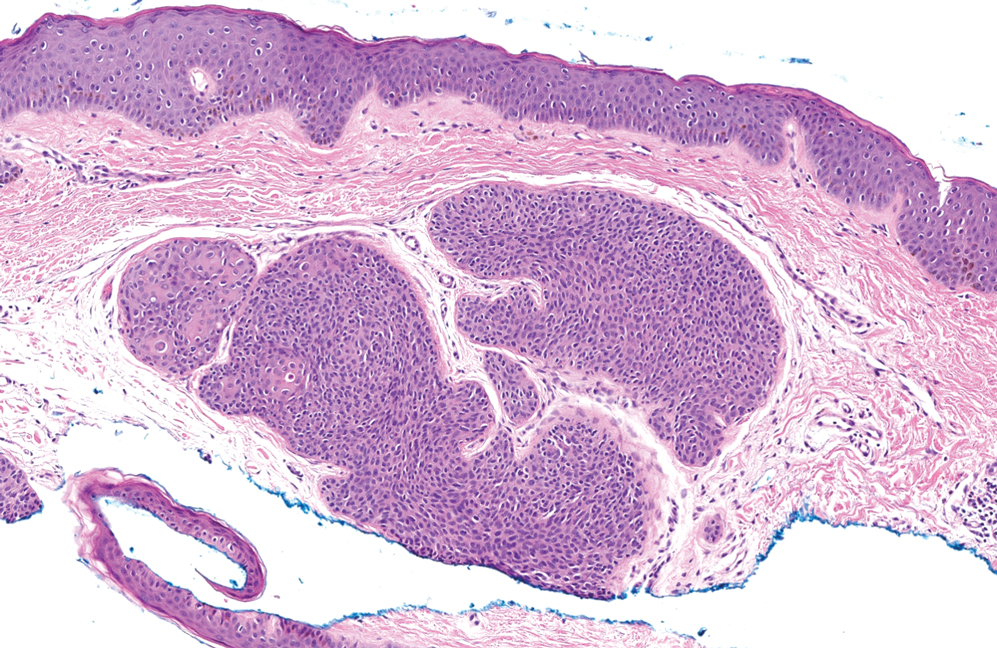

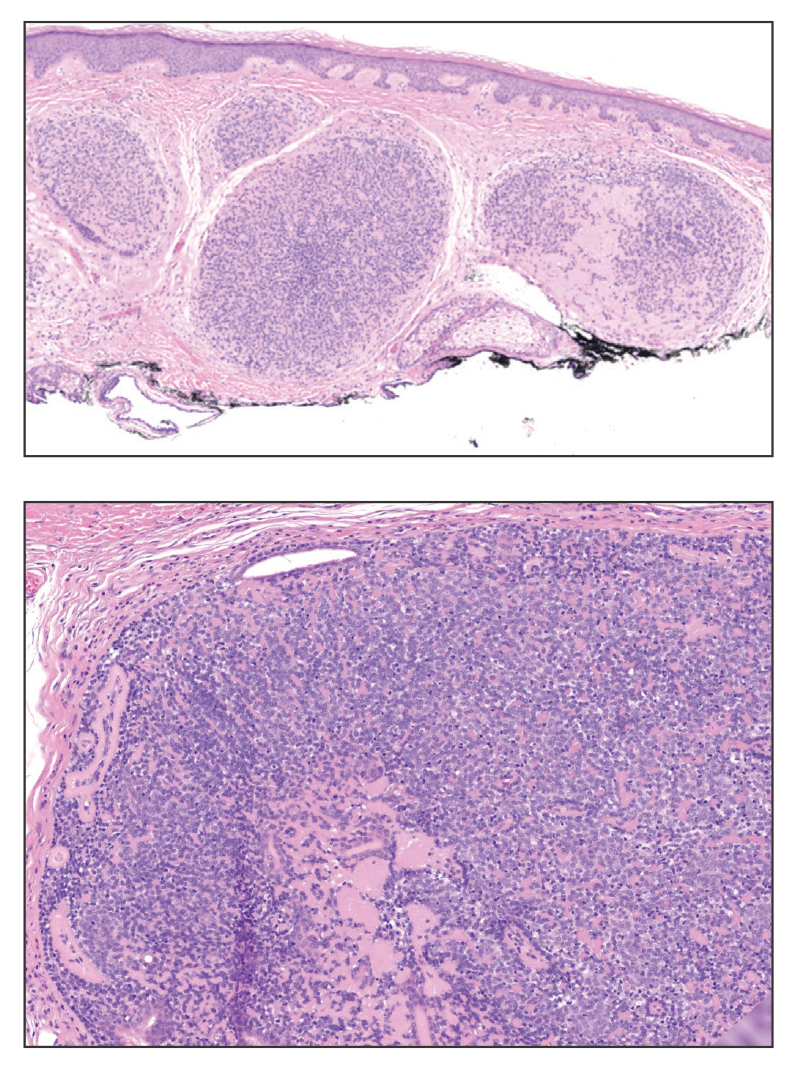

Trichoblastomas typically are deep-seated basaloid follicular neoplasms on the scalp with papillary mesenchyme resembling the normal fibrous sheath of the hair follicle, often replete with papillary mesenchymal bodies (Figure 2). There generally are no retraction spaces between its basaloid nests and the surrounding stroma, which is unlikely to contain mucin relative to basal cell carcinoma (BCC).4,5

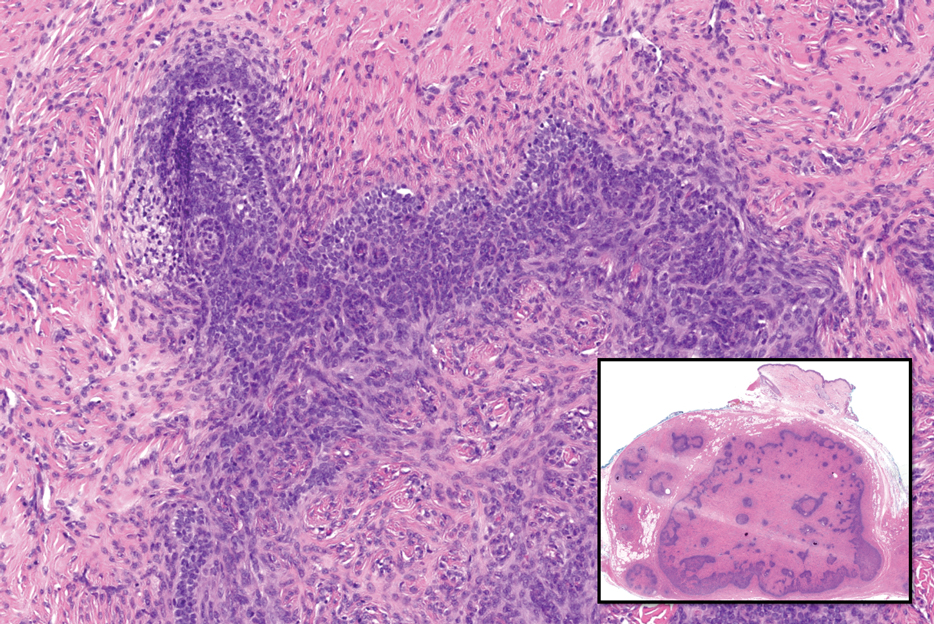

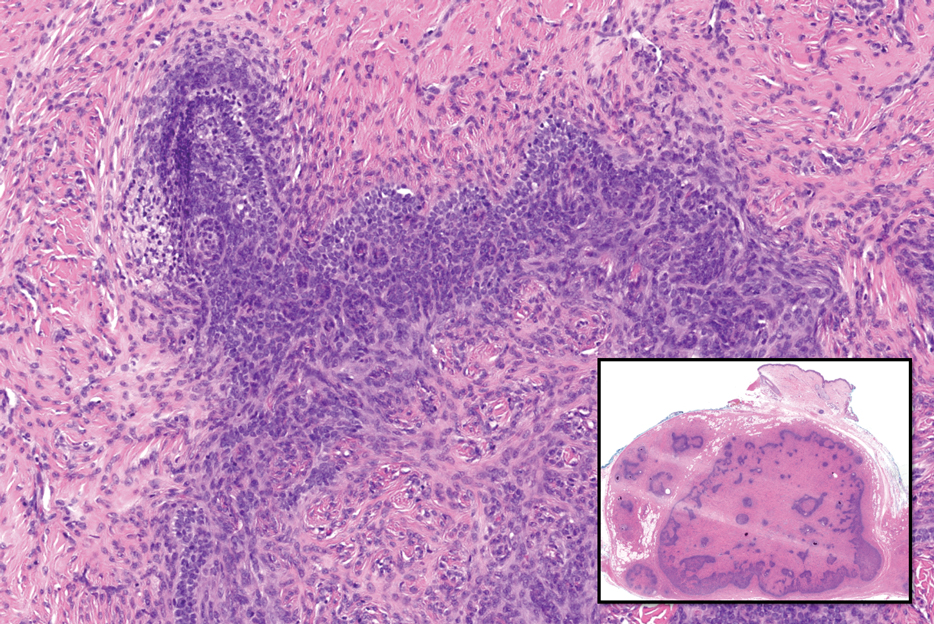

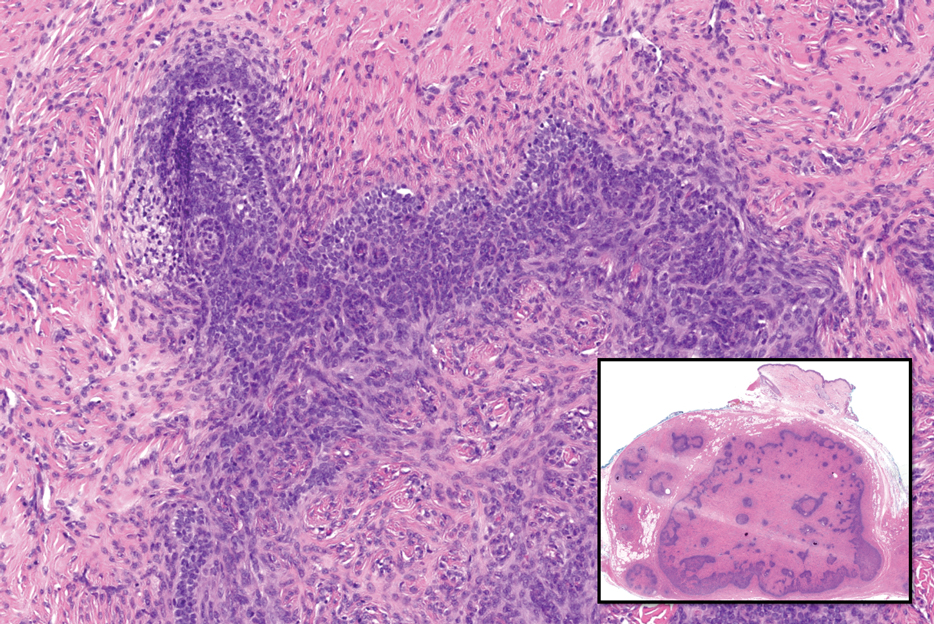

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare salivary gland tumor that can metastasize to the skin and rarely arises as a primary skin adnexal tumor. It manifests as a slowgrowing mass that can be tender to palpation.6 Histologic examination shows dermal islands with cribriform blue and pink spaces. Compared to BCC, adenoid cystic carcinoma cells are enlarged and epithelioid with relatively scarce cytoplasm (Figure 3).6,7 Adenoid cystic carcinoma can show variable growth patterns including infiltrative nests and trabeculae. Perineural invasion is common, and there is a high risk for local recurrence.7 First-line therapy usually is surgical, and postoperative radiotherapy may be required.6,7

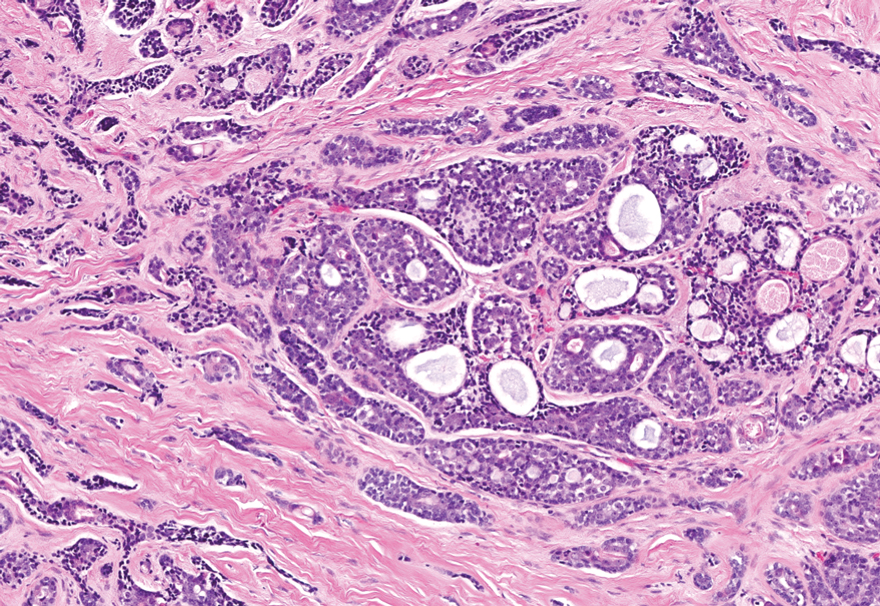

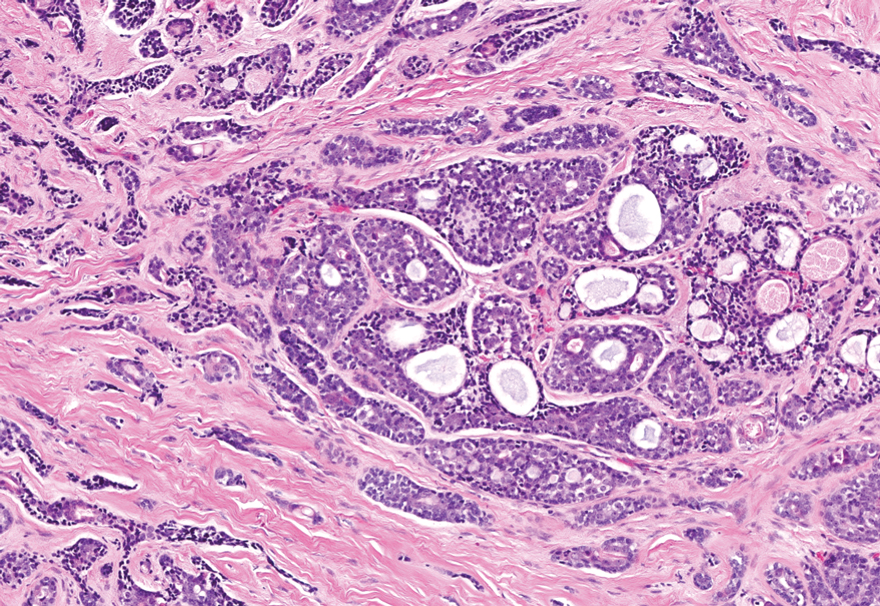

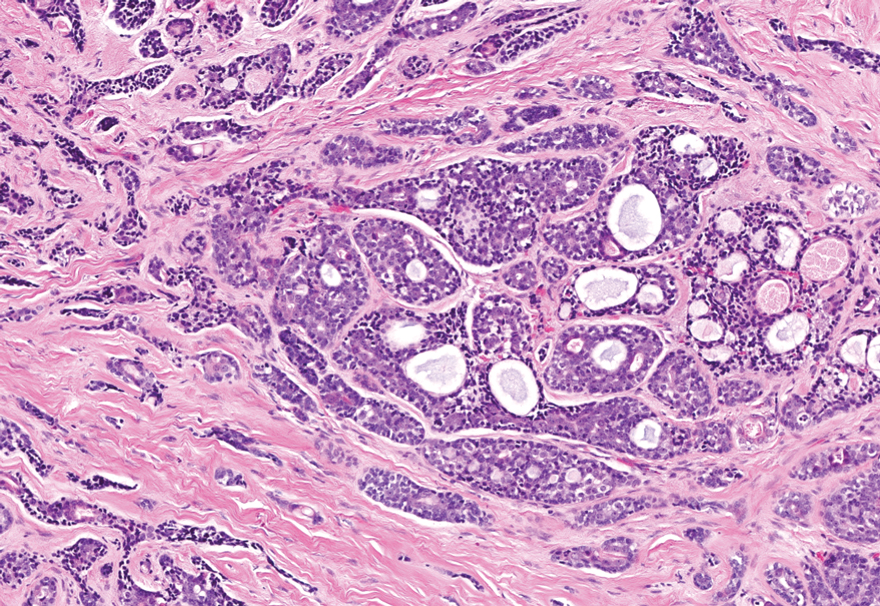

Nodular BCC commonly manifests as an enlarging nonhealing lesion on sun-exposed skin and has many subtypes, typically with arborizing telangiectases on dermoscopy. Histopathologic examination of nodular BCC reveals a nest of basaloid follicular germinative cells in the dermis with peripheral palisading and a fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 4).8 Patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome are at increased risk for nodular BCC, which may be clinically indistinguishable from spiradenoma, cylindroma, and spiradenocylindroma, necessitating histologic assessment.

- Facchini V, Colangeli W, Bozza F, et al. A rare histopathological spiradenocylindroma: a case report. Clin Ter. 2022;173:292-294. doi:10.7417/ CT.2022.2433

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update [published online March 14, 2016]. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-30. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0705-x

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9010007

- Elston DM. Pilar and sebaceous neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018:71-85.

- McCalmont TH, Pincus LB. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni, L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1930-1953.

- Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—an update [published online May 2, 2015]. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:652-661. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.005

- Tonev ID, Pirgova YS, Conev NV. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin with multiple local recurrences. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8:251- 255. doi:10.1159/000431082

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations [published online May 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

Shave biopsies of our patient’s lesions showed wellcircumscribed dermal nodules resembling a spiradenoma with 3 cell populations: those with lighter nuclei, darker nuclei, and scattered lymphocytes. However, the conspicuous globules of basement membrane material were reminiscent of a cylindroma. These overlapping features and the patient’s history of cylindroma were suggestive of a diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma.

Spiradenocylindroma is an uncommon dermal tumor with features that overlap with spiradenoma and cylindroma.1 It may manifest as a solitary lesion or multiple lesions and can occur sporadically or in the context of a family history. Histologically, it must be distinguished from other intradermal basaloid neoplasms including conventional cylindroma and spiradenoma, dermal duct tumor, hidradenoma, and trichoblastoma.

When patients present with multiple cylindromas, spiradenomas, or spiradenocylindromas, physicians should consider genetic testing and review of the family history to assess for cylindromatosis gene mutations or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Biopsy and histologic examination are important because malignant tumors can evolve from pre-existing spiradenocylindromas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas,2 with an increased risk in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.1 Our patient declined further genetic workup but continues to follow up with dermatology for monitoring of lesions.

Dermal duct tumors are morphologic variants of poromas that are derived from sweat gland lineage and usually manifest as solitary dome-shaped papules, plaques, or nodules most often seen on acral surfaces as well as the head and neck.3 Clinically, they may be indistinguishable from spiradenocylindromas and require biopsy for histologic evaluation. They can be distinguished from spiradenocylindroma by the presence of small dermal nodules composed of cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm and cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).

Trichoblastomas typically are deep-seated basaloid follicular neoplasms on the scalp with papillary mesenchyme resembling the normal fibrous sheath of the hair follicle, often replete with papillary mesenchymal bodies (Figure 2). There generally are no retraction spaces between its basaloid nests and the surrounding stroma, which is unlikely to contain mucin relative to basal cell carcinoma (BCC).4,5

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare salivary gland tumor that can metastasize to the skin and rarely arises as a primary skin adnexal tumor. It manifests as a slowgrowing mass that can be tender to palpation.6 Histologic examination shows dermal islands with cribriform blue and pink spaces. Compared to BCC, adenoid cystic carcinoma cells are enlarged and epithelioid with relatively scarce cytoplasm (Figure 3).6,7 Adenoid cystic carcinoma can show variable growth patterns including infiltrative nests and trabeculae. Perineural invasion is common, and there is a high risk for local recurrence.7 First-line therapy usually is surgical, and postoperative radiotherapy may be required.6,7

Nodular BCC commonly manifests as an enlarging nonhealing lesion on sun-exposed skin and has many subtypes, typically with arborizing telangiectases on dermoscopy. Histopathologic examination of nodular BCC reveals a nest of basaloid follicular germinative cells in the dermis with peripheral palisading and a fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 4).8 Patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome are at increased risk for nodular BCC, which may be clinically indistinguishable from spiradenoma, cylindroma, and spiradenocylindroma, necessitating histologic assessment.

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

Shave biopsies of our patient’s lesions showed wellcircumscribed dermal nodules resembling a spiradenoma with 3 cell populations: those with lighter nuclei, darker nuclei, and scattered lymphocytes. However, the conspicuous globules of basement membrane material were reminiscent of a cylindroma. These overlapping features and the patient’s history of cylindroma were suggestive of a diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma.

Spiradenocylindroma is an uncommon dermal tumor with features that overlap with spiradenoma and cylindroma.1 It may manifest as a solitary lesion or multiple lesions and can occur sporadically or in the context of a family history. Histologically, it must be distinguished from other intradermal basaloid neoplasms including conventional cylindroma and spiradenoma, dermal duct tumor, hidradenoma, and trichoblastoma.

When patients present with multiple cylindromas, spiradenomas, or spiradenocylindromas, physicians should consider genetic testing and review of the family history to assess for cylindromatosis gene mutations or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Biopsy and histologic examination are important because malignant tumors can evolve from pre-existing spiradenocylindromas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas,2 with an increased risk in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.1 Our patient declined further genetic workup but continues to follow up with dermatology for monitoring of lesions.

Dermal duct tumors are morphologic variants of poromas that are derived from sweat gland lineage and usually manifest as solitary dome-shaped papules, plaques, or nodules most often seen on acral surfaces as well as the head and neck.3 Clinically, they may be indistinguishable from spiradenocylindromas and require biopsy for histologic evaluation. They can be distinguished from spiradenocylindroma by the presence of small dermal nodules composed of cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm and cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).

Trichoblastomas typically are deep-seated basaloid follicular neoplasms on the scalp with papillary mesenchyme resembling the normal fibrous sheath of the hair follicle, often replete with papillary mesenchymal bodies (Figure 2). There generally are no retraction spaces between its basaloid nests and the surrounding stroma, which is unlikely to contain mucin relative to basal cell carcinoma (BCC).4,5

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare salivary gland tumor that can metastasize to the skin and rarely arises as a primary skin adnexal tumor. It manifests as a slowgrowing mass that can be tender to palpation.6 Histologic examination shows dermal islands with cribriform blue and pink spaces. Compared to BCC, adenoid cystic carcinoma cells are enlarged and epithelioid with relatively scarce cytoplasm (Figure 3).6,7 Adenoid cystic carcinoma can show variable growth patterns including infiltrative nests and trabeculae. Perineural invasion is common, and there is a high risk for local recurrence.7 First-line therapy usually is surgical, and postoperative radiotherapy may be required.6,7

Nodular BCC commonly manifests as an enlarging nonhealing lesion on sun-exposed skin and has many subtypes, typically with arborizing telangiectases on dermoscopy. Histopathologic examination of nodular BCC reveals a nest of basaloid follicular germinative cells in the dermis with peripheral palisading and a fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 4).8 Patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome are at increased risk for nodular BCC, which may be clinically indistinguishable from spiradenoma, cylindroma, and spiradenocylindroma, necessitating histologic assessment.

- Facchini V, Colangeli W, Bozza F, et al. A rare histopathological spiradenocylindroma: a case report. Clin Ter. 2022;173:292-294. doi:10.7417/ CT.2022.2433

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update [published online March 14, 2016]. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-30. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0705-x

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9010007

- Elston DM. Pilar and sebaceous neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018:71-85.

- McCalmont TH, Pincus LB. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni, L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1930-1953.

- Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—an update [published online May 2, 2015]. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:652-661. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.005

- Tonev ID, Pirgova YS, Conev NV. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin with multiple local recurrences. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8:251- 255. doi:10.1159/000431082

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations [published online May 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

- Facchini V, Colangeli W, Bozza F, et al. A rare histopathological spiradenocylindroma: a case report. Clin Ter. 2022;173:292-294. doi:10.7417/ CT.2022.2433

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update [published online March 14, 2016]. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-30. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0705-x

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9010007

- Elston DM. Pilar and sebaceous neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018:71-85.

- McCalmont TH, Pincus LB. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni, L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1930-1953.

- Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—an update [published online May 2, 2015]. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:652-661. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.005

- Tonev ID, Pirgova YS, Conev NV. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin with multiple local recurrences. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8:251- 255. doi:10.1159/000431082

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations [published online May 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

A 62-year-old man with a history of cylindromas presented to our clinic with multiple asymptomatic, 3- to 4-mm, nonmobile, dome-shaped, telangiectatic, pink papules over the parietal and vertex scalp that had been present for more than 10 years without change. Several family members had similar lesions that had not been evaluated by a physician, and there had been no genetic evaluation. Shave biopsies of several lesions were performed.

Papules on the Breast, Flank, and Arm Following Breast Cancer Treatment

The Diagnosis: Acquired Cutaneous Lymphangiectasia

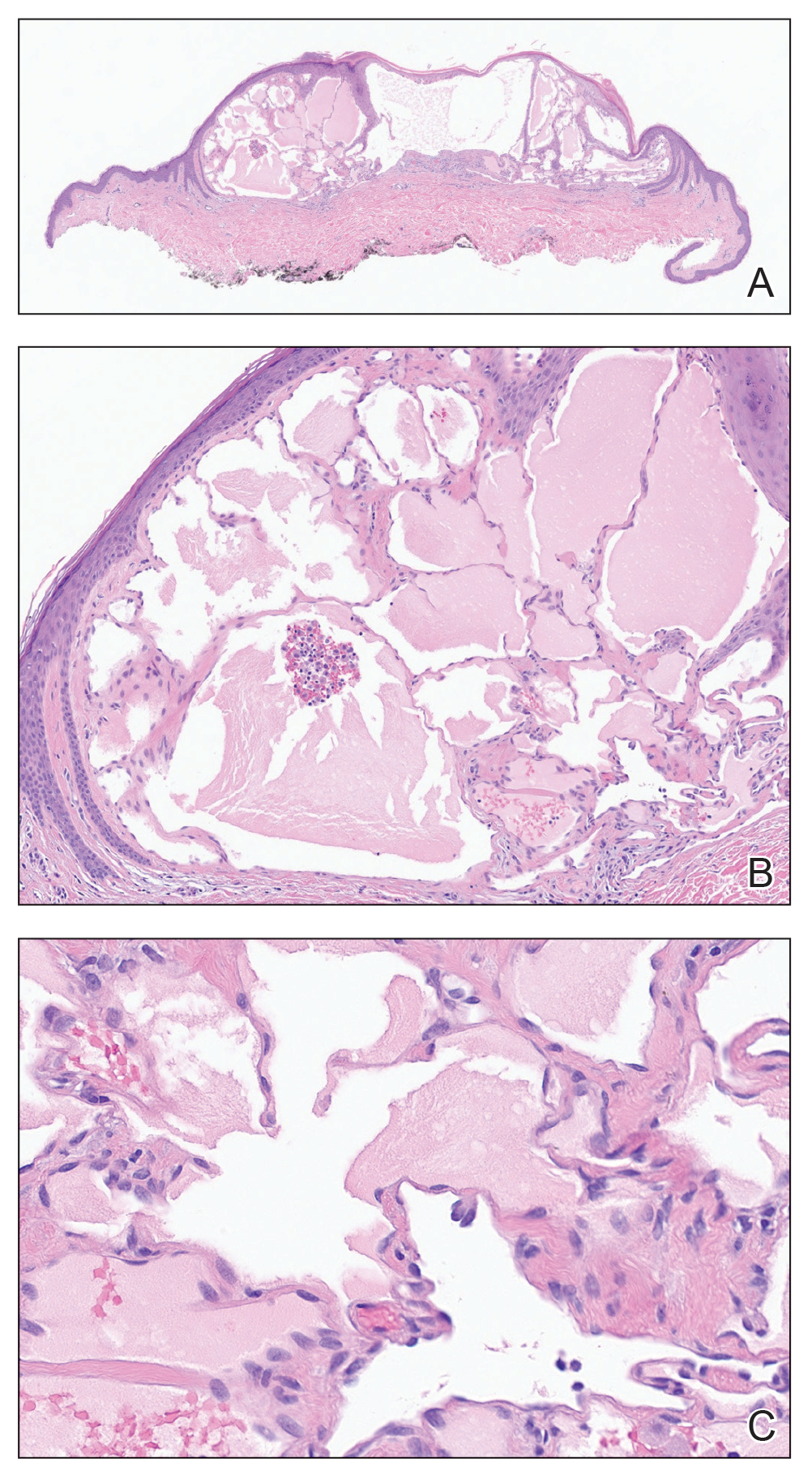

Histopathology showed a cluster of widely ectatic, thin-walled lymphatic spaces immediately subjacent to the epidermis and flanked by an epidermal collarette (Figure, A). The vessels did not extend any further than the papillary dermis and were not accompanied by any notable inflammation (Figure, B). A single layer of bland endothelial cells lined each lymphatic space (Figure, C). A diagnosis of acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia secondary to surgical and radiation treatment of breast cancer was made. Clinical monitoring was recommended, but no treatment was required unless symptoms arose. At 2-year follow-up, she continued to do well.

Acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia is characterized by benign dilations of surface lymphatic vessels, likely resulting from disruption of the lymphatic system.1 This finding most commonly occurs on the external genitalia following combined surgical and radiation treatment of malignancy, though in a minority of cases it is seen with surgical or radiation treatment alone.2 Acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia secondary to radical mastectomy for breast cancer was first reported in 1956 in a patient with persistent ipsilateral lymphadenopathy.3 The presentation in a patient with Cowden syndrome is rare. Cowden syndrome (also called PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome) is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder caused by mutations in the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog gene, PTEN. It is characterized by multiple hamartomas and substantially increased risk for breast, endometrial, and thyroid malignancy.4 In addition to breast cancer, our patient had a history of papillary thyroid carcinoma, cerebellar dysplastic gangliocytoma, and multiple cutaneous fibromas and angiolipomas.

A diagnosis of syringomas—benign tumors that arise from the intraepidermal aspect of eccrine sweat ducts— could be considered in the differential diagnosis. Cases of eruptive syringoma on the breast have been reported, but the biopsy would show a circumscribed proliferation of tadpole-shaped tubules comprised of secretory cells in a sclerotic stroma.5 Hidrocystomas are benign sweat gland cysts that present on the face, especially around the eyes, but rarely have been reported on the trunk, particularly the axillae.6 Although they clinically manifest as translucent papules, histopathology shows fluid-filled cysts lined by a layer of secretory columnar epithelium.7 Metastatic breast carcinoma was considered, given the patient’s history of breast cancer. Cutaneous metastases often are found on the chest wall but also can occur at distant sites. Histopathology can reveal various patterns, including islands of tumor cells with glandular formation or single files of cells infiltrating through dermal collagen.

Angiosarcoma also must be considered in the setting of any vasoformative proliferation arising on previously irradiated skin. Angiosarcomas can sometimes be well differentiated with paradoxically bland cytomorphology but characteristically have anastomosing vessels and infiltrative architecture, which were not identified in our patient. Other diagnostic features of angiosarcoma include endothelial nuclear atypia, multilayering, and mitoses. Radiation-associated angiosarcomas amplify MYC, a transcription factor that affects multiple aspects of the cell cycle and is an oncogene implicated in several different types of malignancy.8MYC immunohistochemistry testing should be performed whenever a vasoformative proliferation on irradiated skin is partially sampled or shows any features concerning for angiosarcoma. Lastly, the term postradiation atypical vascular lesion has been introduced to describe discrete papular proliferations that show close histopathologic overlap with lymphangioma/lymphatic malformations. In contrast, atypical vascular lesions show wedge-shaped intradermal growth that can cause diagnostic confusion with well-differentiated angiosarcoma. Unlike angiosarcomas, they do not express MYC. Postradiation atypical vascular lesions sometimes have an associated inflammatory infiltrate.9 Considerable histomorphologic overlap among lymphangiomas, atypical vascular lesions, and well-differentiated angiosarcomas exists; thus, lesions should be removed in their perceived totality whenever possible to help permit diagnostic distinction. In our patient, the abrupt discontinuation of vessels at the interface of the papillary and reticular dermis was reassuring of benignancy.

Our patient’s diagnosis of acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia was a benign adverse effect of prior breast cancer treatments. This case demonstrates a rare dermatologic sequela that may arise in patients who receive surgical or radiation treatment of breast cancer. Given the heightened risk for angiosarcoma after radiation therapy as well as the increased risk for malignancy in patients with Cowden syndrome, biopsy can be an important diagnostic step in the management of these patients.

- Valdés F, Peteiro C, Toribio J. Acquired lymphangiectases and breast cancer. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2007;98:347-350.

- Chiyomaru K, Nishigori C. Acquired lymphangiectasia associated with treatment for preceding malignant neoplasm: a retrospective series of 73 Japanese patients. AMA Arch Derm. 2009;145:841-842.

- Plotnick H, Richfield D. Tuberous lymphangiectatic varices secondary to radical mastectomy. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:466-468.

- Pilarski R, Burt R, Kohlman W, et al. Cowden syndrome and the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: systematic review and revised diagnostic criteria. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1607-1616.

- Müller CSL, Tilgen W, Pföhler C. Clinicopathological diversity of syringomas: a study on current clinical and histopathologic concepts. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:282-288.

- Anzai S, Goto M, Fujiwara S, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma: a case report and analysis of 167 Japanese cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:702-703.

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. MedGenMed. 2006;8:57.

- Ahmadi SE, Rahimi S, Zarandi B, et al. MYC: a multipurpose oncogene with prognostic and therapeutic implications in blood malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:121. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01111-4

- Ronen S, Ivan D, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. Post-radiation vascular lesions of the breast. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:52-58.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Cutaneous Lymphangiectasia

Histopathology showed a cluster of widely ectatic, thin-walled lymphatic spaces immediately subjacent to the epidermis and flanked by an epidermal collarette (Figure, A). The vessels did not extend any further than the papillary dermis and were not accompanied by any notable inflammation (Figure, B). A single layer of bland endothelial cells lined each lymphatic space (Figure, C). A diagnosis of acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia secondary to surgical and radiation treatment of breast cancer was made. Clinical monitoring was recommended, but no treatment was required unless symptoms arose. At 2-year follow-up, she continued to do well.

Acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia is characterized by benign dilations of surface lymphatic vessels, likely resulting from disruption of the lymphatic system.1 This finding most commonly occurs on the external genitalia following combined surgical and radiation treatment of malignancy, though in a minority of cases it is seen with surgical or radiation treatment alone.2 Acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia secondary to radical mastectomy for breast cancer was first reported in 1956 in a patient with persistent ipsilateral lymphadenopathy.3 The presentation in a patient with Cowden syndrome is rare. Cowden syndrome (also called PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome) is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder caused by mutations in the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog gene, PTEN. It is characterized by multiple hamartomas and substantially increased risk for breast, endometrial, and thyroid malignancy.4 In addition to breast cancer, our patient had a history of papillary thyroid carcinoma, cerebellar dysplastic gangliocytoma, and multiple cutaneous fibromas and angiolipomas.

A diagnosis of syringomas—benign tumors that arise from the intraepidermal aspect of eccrine sweat ducts— could be considered in the differential diagnosis. Cases of eruptive syringoma on the breast have been reported, but the biopsy would show a circumscribed proliferation of tadpole-shaped tubules comprised of secretory cells in a sclerotic stroma.5 Hidrocystomas are benign sweat gland cysts that present on the face, especially around the eyes, but rarely have been reported on the trunk, particularly the axillae.6 Although they clinically manifest as translucent papules, histopathology shows fluid-filled cysts lined by a layer of secretory columnar epithelium.7 Metastatic breast carcinoma was considered, given the patient’s history of breast cancer. Cutaneous metastases often are found on the chest wall but also can occur at distant sites. Histopathology can reveal various patterns, including islands of tumor cells with glandular formation or single files of cells infiltrating through dermal collagen.

Angiosarcoma also must be considered in the setting of any vasoformative proliferation arising on previously irradiated skin. Angiosarcomas can sometimes be well differentiated with paradoxically bland cytomorphology but characteristically have anastomosing vessels and infiltrative architecture, which were not identified in our patient. Other diagnostic features of angiosarcoma include endothelial nuclear atypia, multilayering, and mitoses. Radiation-associated angiosarcomas amplify MYC, a transcription factor that affects multiple aspects of the cell cycle and is an oncogene implicated in several different types of malignancy.8MYC immunohistochemistry testing should be performed whenever a vasoformative proliferation on irradiated skin is partially sampled or shows any features concerning for angiosarcoma. Lastly, the term postradiation atypical vascular lesion has been introduced to describe discrete papular proliferations that show close histopathologic overlap with lymphangioma/lymphatic malformations. In contrast, atypical vascular lesions show wedge-shaped intradermal growth that can cause diagnostic confusion with well-differentiated angiosarcoma. Unlike angiosarcomas, they do not express MYC. Postradiation atypical vascular lesions sometimes have an associated inflammatory infiltrate.9 Considerable histomorphologic overlap among lymphangiomas, atypical vascular lesions, and well-differentiated angiosarcomas exists; thus, lesions should be removed in their perceived totality whenever possible to help permit diagnostic distinction. In our patient, the abrupt discontinuation of vessels at the interface of the papillary and reticular dermis was reassuring of benignancy.

Our patient’s diagnosis of acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia was a benign adverse effect of prior breast cancer treatments. This case demonstrates a rare dermatologic sequela that may arise in patients who receive surgical or radiation treatment of breast cancer. Given the heightened risk for angiosarcoma after radiation therapy as well as the increased risk for malignancy in patients with Cowden syndrome, biopsy can be an important diagnostic step in the management of these patients.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Cutaneous Lymphangiectasia

Histopathology showed a cluster of widely ectatic, thin-walled lymphatic spaces immediately subjacent to the epidermis and flanked by an epidermal collarette (Figure, A). The vessels did not extend any further than the papillary dermis and were not accompanied by any notable inflammation (Figure, B). A single layer of bland endothelial cells lined each lymphatic space (Figure, C). A diagnosis of acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia secondary to surgical and radiation treatment of breast cancer was made. Clinical monitoring was recommended, but no treatment was required unless symptoms arose. At 2-year follow-up, she continued to do well.

Acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia is characterized by benign dilations of surface lymphatic vessels, likely resulting from disruption of the lymphatic system.1 This finding most commonly occurs on the external genitalia following combined surgical and radiation treatment of malignancy, though in a minority of cases it is seen with surgical or radiation treatment alone.2 Acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia secondary to radical mastectomy for breast cancer was first reported in 1956 in a patient with persistent ipsilateral lymphadenopathy.3 The presentation in a patient with Cowden syndrome is rare. Cowden syndrome (also called PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome) is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder caused by mutations in the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog gene, PTEN. It is characterized by multiple hamartomas and substantially increased risk for breast, endometrial, and thyroid malignancy.4 In addition to breast cancer, our patient had a history of papillary thyroid carcinoma, cerebellar dysplastic gangliocytoma, and multiple cutaneous fibromas and angiolipomas.

A diagnosis of syringomas—benign tumors that arise from the intraepidermal aspect of eccrine sweat ducts— could be considered in the differential diagnosis. Cases of eruptive syringoma on the breast have been reported, but the biopsy would show a circumscribed proliferation of tadpole-shaped tubules comprised of secretory cells in a sclerotic stroma.5 Hidrocystomas are benign sweat gland cysts that present on the face, especially around the eyes, but rarely have been reported on the trunk, particularly the axillae.6 Although they clinically manifest as translucent papules, histopathology shows fluid-filled cysts lined by a layer of secretory columnar epithelium.7 Metastatic breast carcinoma was considered, given the patient’s history of breast cancer. Cutaneous metastases often are found on the chest wall but also can occur at distant sites. Histopathology can reveal various patterns, including islands of tumor cells with glandular formation or single files of cells infiltrating through dermal collagen.

Angiosarcoma also must be considered in the setting of any vasoformative proliferation arising on previously irradiated skin. Angiosarcomas can sometimes be well differentiated with paradoxically bland cytomorphology but characteristically have anastomosing vessels and infiltrative architecture, which were not identified in our patient. Other diagnostic features of angiosarcoma include endothelial nuclear atypia, multilayering, and mitoses. Radiation-associated angiosarcomas amplify MYC, a transcription factor that affects multiple aspects of the cell cycle and is an oncogene implicated in several different types of malignancy.8MYC immunohistochemistry testing should be performed whenever a vasoformative proliferation on irradiated skin is partially sampled or shows any features concerning for angiosarcoma. Lastly, the term postradiation atypical vascular lesion has been introduced to describe discrete papular proliferations that show close histopathologic overlap with lymphangioma/lymphatic malformations. In contrast, atypical vascular lesions show wedge-shaped intradermal growth that can cause diagnostic confusion with well-differentiated angiosarcoma. Unlike angiosarcomas, they do not express MYC. Postradiation atypical vascular lesions sometimes have an associated inflammatory infiltrate.9 Considerable histomorphologic overlap among lymphangiomas, atypical vascular lesions, and well-differentiated angiosarcomas exists; thus, lesions should be removed in their perceived totality whenever possible to help permit diagnostic distinction. In our patient, the abrupt discontinuation of vessels at the interface of the papillary and reticular dermis was reassuring of benignancy.

Our patient’s diagnosis of acquired cutaneous lymphangiectasia was a benign adverse effect of prior breast cancer treatments. This case demonstrates a rare dermatologic sequela that may arise in patients who receive surgical or radiation treatment of breast cancer. Given the heightened risk for angiosarcoma after radiation therapy as well as the increased risk for malignancy in patients with Cowden syndrome, biopsy can be an important diagnostic step in the management of these patients.

- Valdés F, Peteiro C, Toribio J. Acquired lymphangiectases and breast cancer. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2007;98:347-350.

- Chiyomaru K, Nishigori C. Acquired lymphangiectasia associated with treatment for preceding malignant neoplasm: a retrospective series of 73 Japanese patients. AMA Arch Derm. 2009;145:841-842.

- Plotnick H, Richfield D. Tuberous lymphangiectatic varices secondary to radical mastectomy. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:466-468.

- Pilarski R, Burt R, Kohlman W, et al. Cowden syndrome and the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: systematic review and revised diagnostic criteria. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1607-1616.

- Müller CSL, Tilgen W, Pföhler C. Clinicopathological diversity of syringomas: a study on current clinical and histopathologic concepts. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:282-288.

- Anzai S, Goto M, Fujiwara S, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma: a case report and analysis of 167 Japanese cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:702-703.

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. MedGenMed. 2006;8:57.

- Ahmadi SE, Rahimi S, Zarandi B, et al. MYC: a multipurpose oncogene with prognostic and therapeutic implications in blood malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:121. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01111-4

- Ronen S, Ivan D, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. Post-radiation vascular lesions of the breast. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:52-58.

- Valdés F, Peteiro C, Toribio J. Acquired lymphangiectases and breast cancer. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2007;98:347-350.

- Chiyomaru K, Nishigori C. Acquired lymphangiectasia associated with treatment for preceding malignant neoplasm: a retrospective series of 73 Japanese patients. AMA Arch Derm. 2009;145:841-842.

- Plotnick H, Richfield D. Tuberous lymphangiectatic varices secondary to radical mastectomy. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:466-468.

- Pilarski R, Burt R, Kohlman W, et al. Cowden syndrome and the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: systematic review and revised diagnostic criteria. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1607-1616.

- Müller CSL, Tilgen W, Pföhler C. Clinicopathological diversity of syringomas: a study on current clinical and histopathologic concepts. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:282-288.

- Anzai S, Goto M, Fujiwara S, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma: a case report and analysis of 167 Japanese cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:702-703.

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. MedGenMed. 2006;8:57.

- Ahmadi SE, Rahimi S, Zarandi B, et al. MYC: a multipurpose oncogene with prognostic and therapeutic implications in blood malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:121. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01111-4

- Ronen S, Ivan D, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. Post-radiation vascular lesions of the breast. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:52-58.

A 47-year-old woman with Cowden syndrome presented to the dermatology clinic with asymptomatic papules on and near the right breast that had increased in number over the last year. She had a medical history of breast cancer treated with mastectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation; papillary thyroid carcinoma treated with thyroidectomy and subsequent thyroid hormone replacement; dysplastic cerebellar gangliocytoma treated with surgical excision; and multiple cutaneous fibromas and angiolipomas. Physical examination revealed multiple clustered, 1- to 5-mm, translucent to red papules on the right breast, flank, and upper arm. A shave biopsy of a papule from the right lateral breast was performed.

Painful Violaceous Nodule With Peripheral Hyperpigmentation

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

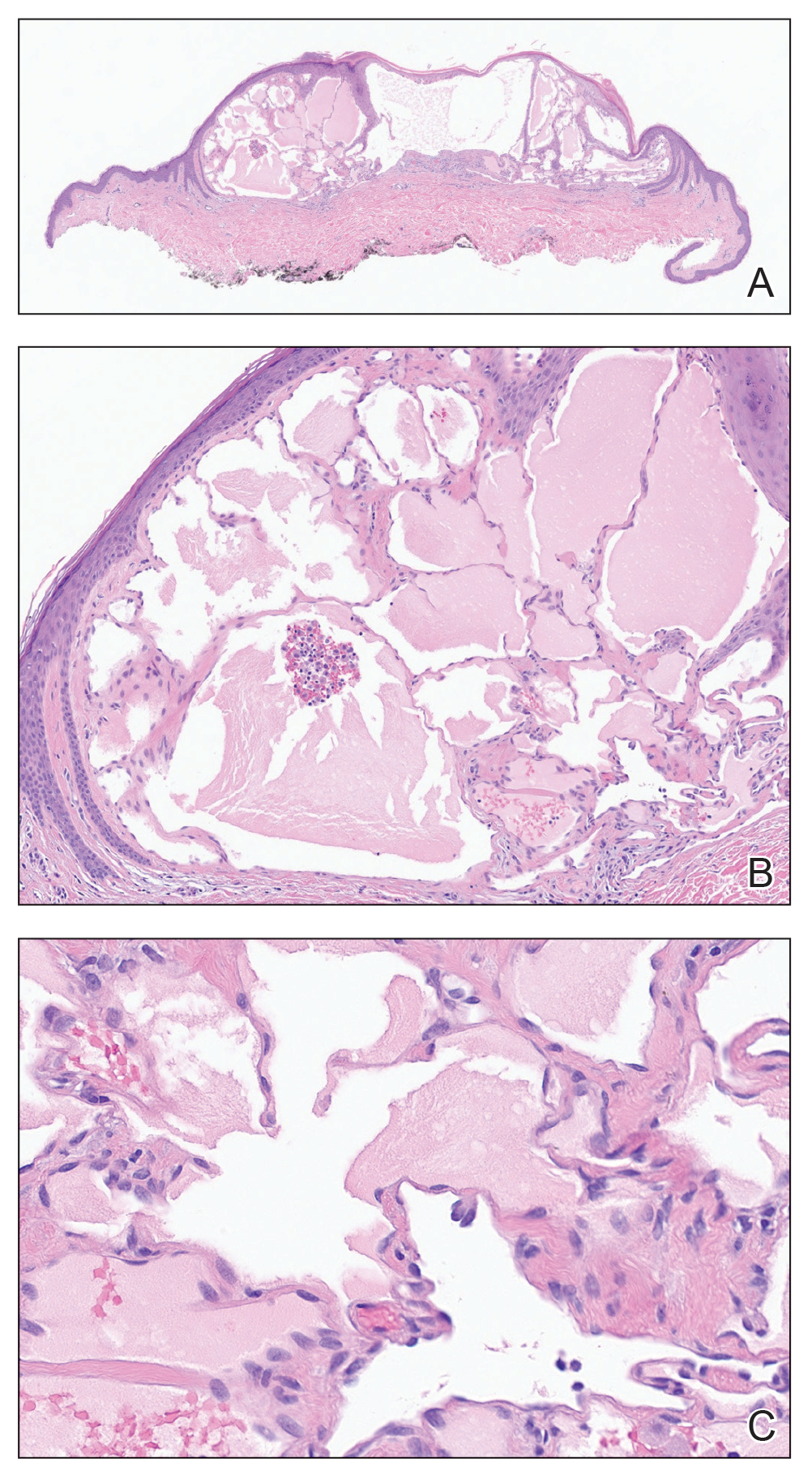

Biopsy of the lesion revealed a circumscribed dermal nodule comprised of storiform arrangements of enlarged, plump, fibrohistiocytic cells punctuated by variably sized clefts and large cystic spaces filled with blood that lacked an endothelial lining. No bizarre nuclear pleomorphism, atypical mitoses, or tumor necrosis were identified. The overlying epidermis exhibited mild acanthosis with broadening of the rete ridges. Proliferative spindled cells entrapped dermal collagen bundles at the periphery. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages were present throughout the proliferation and in the adjacent dermis (Figure). These findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma (ADF).

Aneurysmal dermatofibroma, also known as aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare variant of dermatofibroma that was described by Santa Cruz et al1 in 1981 and represents 2% to 6% of dermatofibromas.1,2 Aneurysmal dermatofibromas often lack the characteristic clinical and dermoscopic findings of conventional dermatofibromas, creating a diagnostic challenge for the clinician.3 Incomplete excision of this benign tumor was associated with a local recurrence rate of 19% (5/26) in one study,4 in contrast with the exceedingly low rate of local recurrence (<2%) attributed to conventional dermatofibromas.2,4

Clinically, ADFs commonly appear as blue-brown nodules on the arms and legs, often with a history of rapid and sometimes painful growth.1 Clinically, an ADF can have vascular, cystic, or melanocytic features that, in the context of lacking typical clinical findings of a dermatofibroma, can complicate clinical diagnosis; for example, ADFs can demonstrate several melanomalike features including atypical vessels, chrysalis structures, blue-white structures, a pinkish-white veil, irregular brown globulelike structures, an atypical pigment network, color variegation, a multicomponent pattern, and ulceration.3 Alternatively, ADFs can present with a vascular tumor-like pattern consisting of white areas and globular blue-red areas or a polymorphous vascular pattern with a peripheral collarette.

Our case illustrates the classic histologic appearance of an ADF. Large cavities and slitlike spaces filled with blood distinguish this entity from conventional dermatofibroma and other dermatofibroma variants; for example, cellular dermatofibroma is a benign variant of dermatofibroma that exhibits crowded fascicular architecture without an increase in vascular spaces. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas also should be distinguished from angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, which has intermediate malignant potential despite a similar-sounding name and a similar nodular appearance with large blood-filled spaces; however, many cases are located predominantly in the subcutis with epithelioid morphology, desmin immunohistochemical reactivity, and prominent tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation that can be mistaken for a lymph node.5 Furthermore, in contrast with vascular tumors, the blood-filled spaces of ADFs do not have an endothelial lining.

In summary, ADF is a rare dermatofibroma variant that has a variety of clinical presentations, often masquerading as a cyst, vascular tumor, or melanocytic neoplasm. The classic histopathologic features confirm the diagnosis. Although ADFs can be painful and have a tendency to recur, these lesions have a benign clinical course.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Kyriakos M. Aneurysmal ("angiomatoid") fibrous histiocytoma of the skin. Cancer. 1981;47:2053-2061.

- Alves JV, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Ferrari A, Argenziano G, Buccini P, et al. Typical and atypical dermoscopic presentations of dermatofibroma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1375-1380.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Cutaneous fibrohistiocytic tumours--an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:148-165.

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

Biopsy of the lesion revealed a circumscribed dermal nodule comprised of storiform arrangements of enlarged, plump, fibrohistiocytic cells punctuated by variably sized clefts and large cystic spaces filled with blood that lacked an endothelial lining. No bizarre nuclear pleomorphism, atypical mitoses, or tumor necrosis were identified. The overlying epidermis exhibited mild acanthosis with broadening of the rete ridges. Proliferative spindled cells entrapped dermal collagen bundles at the periphery. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages were present throughout the proliferation and in the adjacent dermis (Figure). These findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma (ADF).

Aneurysmal dermatofibroma, also known as aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare variant of dermatofibroma that was described by Santa Cruz et al1 in 1981 and represents 2% to 6% of dermatofibromas.1,2 Aneurysmal dermatofibromas often lack the characteristic clinical and dermoscopic findings of conventional dermatofibromas, creating a diagnostic challenge for the clinician.3 Incomplete excision of this benign tumor was associated with a local recurrence rate of 19% (5/26) in one study,4 in contrast with the exceedingly low rate of local recurrence (<2%) attributed to conventional dermatofibromas.2,4

Clinically, ADFs commonly appear as blue-brown nodules on the arms and legs, often with a history of rapid and sometimes painful growth.1 Clinically, an ADF can have vascular, cystic, or melanocytic features that, in the context of lacking typical clinical findings of a dermatofibroma, can complicate clinical diagnosis; for example, ADFs can demonstrate several melanomalike features including atypical vessels, chrysalis structures, blue-white structures, a pinkish-white veil, irregular brown globulelike structures, an atypical pigment network, color variegation, a multicomponent pattern, and ulceration.3 Alternatively, ADFs can present with a vascular tumor-like pattern consisting of white areas and globular blue-red areas or a polymorphous vascular pattern with a peripheral collarette.

Our case illustrates the classic histologic appearance of an ADF. Large cavities and slitlike spaces filled with blood distinguish this entity from conventional dermatofibroma and other dermatofibroma variants; for example, cellular dermatofibroma is a benign variant of dermatofibroma that exhibits crowded fascicular architecture without an increase in vascular spaces. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas also should be distinguished from angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, which has intermediate malignant potential despite a similar-sounding name and a similar nodular appearance with large blood-filled spaces; however, many cases are located predominantly in the subcutis with epithelioid morphology, desmin immunohistochemical reactivity, and prominent tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation that can be mistaken for a lymph node.5 Furthermore, in contrast with vascular tumors, the blood-filled spaces of ADFs do not have an endothelial lining.

In summary, ADF is a rare dermatofibroma variant that has a variety of clinical presentations, often masquerading as a cyst, vascular tumor, or melanocytic neoplasm. The classic histopathologic features confirm the diagnosis. Although ADFs can be painful and have a tendency to recur, these lesions have a benign clinical course.

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

Biopsy of the lesion revealed a circumscribed dermal nodule comprised of storiform arrangements of enlarged, plump, fibrohistiocytic cells punctuated by variably sized clefts and large cystic spaces filled with blood that lacked an endothelial lining. No bizarre nuclear pleomorphism, atypical mitoses, or tumor necrosis were identified. The overlying epidermis exhibited mild acanthosis with broadening of the rete ridges. Proliferative spindled cells entrapped dermal collagen bundles at the periphery. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages were present throughout the proliferation and in the adjacent dermis (Figure). These findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma (ADF).

Aneurysmal dermatofibroma, also known as aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare variant of dermatofibroma that was described by Santa Cruz et al1 in 1981 and represents 2% to 6% of dermatofibromas.1,2 Aneurysmal dermatofibromas often lack the characteristic clinical and dermoscopic findings of conventional dermatofibromas, creating a diagnostic challenge for the clinician.3 Incomplete excision of this benign tumor was associated with a local recurrence rate of 19% (5/26) in one study,4 in contrast with the exceedingly low rate of local recurrence (<2%) attributed to conventional dermatofibromas.2,4

Clinically, ADFs commonly appear as blue-brown nodules on the arms and legs, often with a history of rapid and sometimes painful growth.1 Clinically, an ADF can have vascular, cystic, or melanocytic features that, in the context of lacking typical clinical findings of a dermatofibroma, can complicate clinical diagnosis; for example, ADFs can demonstrate several melanomalike features including atypical vessels, chrysalis structures, blue-white structures, a pinkish-white veil, irregular brown globulelike structures, an atypical pigment network, color variegation, a multicomponent pattern, and ulceration.3 Alternatively, ADFs can present with a vascular tumor-like pattern consisting of white areas and globular blue-red areas or a polymorphous vascular pattern with a peripheral collarette.

Our case illustrates the classic histologic appearance of an ADF. Large cavities and slitlike spaces filled with blood distinguish this entity from conventional dermatofibroma and other dermatofibroma variants; for example, cellular dermatofibroma is a benign variant of dermatofibroma that exhibits crowded fascicular architecture without an increase in vascular spaces. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas also should be distinguished from angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, which has intermediate malignant potential despite a similar-sounding name and a similar nodular appearance with large blood-filled spaces; however, many cases are located predominantly in the subcutis with epithelioid morphology, desmin immunohistochemical reactivity, and prominent tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation that can be mistaken for a lymph node.5 Furthermore, in contrast with vascular tumors, the blood-filled spaces of ADFs do not have an endothelial lining.

In summary, ADF is a rare dermatofibroma variant that has a variety of clinical presentations, often masquerading as a cyst, vascular tumor, or melanocytic neoplasm. The classic histopathologic features confirm the diagnosis. Although ADFs can be painful and have a tendency to recur, these lesions have a benign clinical course.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Kyriakos M. Aneurysmal ("angiomatoid") fibrous histiocytoma of the skin. Cancer. 1981;47:2053-2061.

- Alves JV, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Ferrari A, Argenziano G, Buccini P, et al. Typical and atypical dermoscopic presentations of dermatofibroma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1375-1380.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Cutaneous fibrohistiocytic tumours--an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:148-165.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Kyriakos M. Aneurysmal ("angiomatoid") fibrous histiocytoma of the skin. Cancer. 1981;47:2053-2061.

- Alves JV, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Ferrari A, Argenziano G, Buccini P, et al. Typical and atypical dermoscopic presentations of dermatofibroma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1375-1380.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Cutaneous fibrohistiocytic tumours--an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:148-165.

A 30-year-old man presented for evaluation of a painful lesion on the left thigh of 3 to 4 years' duration. Pain was exacerbated on physical exertion and was relieved by application of ice packs and use of over-the-counter analgesics. The patient denied any bleeding from the lesion. No other medical comorbidities were present. Physical examination demonstrated a pink, scaly, 3.2 ×2-cm patch with peripheral hyperpigmentation overlying a central, moderately firm, violaceous, 10.2 ×15-mm nodule on the left anteromedial thigh. The lesion was excised and sent to pathology.