User login

Peristomal Pyoderma Gangrenosum at an Ileostomy Site

To the Editor:

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) is a rare entity first described in 1984.1 Lesions usually begin as pustules that coalesce into an erythematous skin ulceration that contains purulent material. The lesion appears on the skin that surrounds an abdominal stoma. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically is associated with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cancer, blood dyscrasia, diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis.2 We describe a case of PPG following an ileostomy in a patient with colon cancer and a related history of Crohn disease.

A 32-year-old woman presented to a dermatology office with a spontaneously painful, 3.2-cm ulceration that was extremely tender to palpation, located immediately adjacent to the site of an ileostomy (Figure). The patient had a history of refractory constipation that failed to respond to standard conservative measures 4 years prior. She underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed a 6.5-cm, irregularly shaped, exophytic mass in the rectosigmoid portion of the colon. Histopathologic examination of several biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, and additional evaluation determined the cancer to be stage IIB. She had a medical history of pancolonic Crohn disease since high school that was treated with periodic infusions of infliximab at the standard dose of 5 mg/kg. Colon cancer treatment consisted of preoperative radiotherapy, complete colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis, and creation of a J-pouch and formation of a temporary ileostomy, along with postoperative capecitabine chemotherapy.

The ileostomy eventually was reversed, and the patient did well for 3 years. When the patient developed severe abdominal pain, the J-pouch was examined and found to be remarkably involved with Crohn disease. However, during the colonoscopy, the J-pouch was inadvertently punctured, leading to the formation of a large pelvic abscess. The latter necessitated diversion of stool, and the patient had the original ileostomy recreated.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, various consultants suspected the ulceration was possibly a deep fungal infection, cutaneous Crohn disease, a factitious ulceration, or acute allergic contact dermatitis related to some element of ostomy care. However, dermatologic consultation suggested that the troublesome lesion was classic PPG and recommended administration of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α–blocking agent and concomitant intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide.

The patient was treated with subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg once weekly, and received near weekly subcutaneous injections of triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL. After 2 months, the discomfort subsided, and the ulceration gradually resolved into a depressed scar. Eighteen months later, the scar was barely perceptible as a minimally erythematous depression. Adalimumab ultimately was discontinued, as the residual J-pouch was removed, and the biologic drug was associated with extensive alopecia areata–like hair loss. There has been no recurrence of PPG in the 40 months since clinical resolution.

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum, which is characterized by chronic, persistent, or recurrent painful ulceration(s) close to an abdominal stoma. In total, fewer than 100 cases of PPG have been reported thus far in the readily available medical literature.3 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the most frequently diagnosed systemic condition associated with PPG, though other associated conditions include diverticular disease, abdominal malignancy, and neurologic dysfunction. Approximately 2% to 4.3% of all patients who have stoma creation surgery related to underlying IBD develop PPG. It is estimated that the yearly incidence rate of PPG in all abdominal stomas is quite low (approximately 0.6%).4

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum can occur at any age, but it tends to predominate in young to middle-aged adults, with a slight female predilection. The etiology and pathogenesis of PPG are largely unknown, though studies have shown that an abnormal immune response may be critical to its development. Risk factors for PPG are not well defined but potentially include autoimmune disorders, a high body mass index, and females or African Americans with IBD.4 Because PPG does not have characteristic histopathologic features, it is a diagnosis of exclusion that is based on the clinical examination and histologic findings that rule out other potential disorders.

There are 4 types of PPG based on the clinical and histopathologic characteristics: ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum tends to be either ulcerative or vegetative, with ulcerative being by far the predominant type. The onset of PPG is quite variable, occurring a few weeks to several years after stoma formation.5 Ulcer size can range from less than 3 cm to 30 cm.4 Lesions begin as deep painful nodules or as superficial hemorrhagic pustules, either idiopathic or following ostensibly minimal trauma. Subsequently, they become necrotic and form an ulceration. The ulcers can be single or multiple lesions, typically with erythematous raised borders and purulent discharge. The ulcers are extremely painful and rapidly progressive. After the ulcers heal, they often leave a characteristic weblike atrophic scar that can break down further following any form of irritation or trauma.5

A prompt diagnosis of PPG is important. A diagnosis of PPG should be considered when dealing with a noninfectious ulcer surrounding a stoma in patients with IBD or other autoimmune conditions.6 Because PPG is a rare skin disorder, it is likely to be missed and lead to unnecessary diagnostic workup and a delay in proper therapy. In our patient, a diagnosis of PPG was overlooked for other infectious and autoimmune causes. The diagnostic evaluation of a patient with PPG is based on 3 principles: (1) ruling out other causes of a peristomal ulcer, such as an abscess, contact dermatitis, or wound infection; (2) determining whether there is an underlying intestinal bowel disease in the stoma; and (3) identifying associated systemic disorders such as vasculitis, erythema nodosum, or similar processes.4 The differential diagnosis depends on the type and stage of PPG and can include malignancy, vasculitis, extraintestinal IBD, infectious disease, and insect bites. A review of the history of the ulcer is helpful in ruling out other diseases, and a colonoscopy or ileoscopy can identify if patients have an underlying active IBD. Swabs for smear and both bacterial and fungal cultures should be taken from the exudate and directly from the ulcer base. Biopsy of the ulcer also helps to exclude alternative diagnoses.6

The primary goals of treating PPG include to reduce pain and the risk for secondary infection, increase pouch adherence, and decrease purulent exudate.7 Although there is not one well-defined optimal therapeutic intervention, there are a variety of effective approaches that may be considered and used. In mild cases, management methods such as dressings, topical agents, or intralesional steroids may be capable of controlling the disease. Daily wound care is important. Moisture-retentive dressings can control pain, induce collagen formation, promote angiogenesis, and prevent contamination. Cleaning the wound with sterile saline and applying an anti-infective agent also may be effective. Application of ultrapotent topical steroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% can be used in patients without concomitant secondary infection. In patients who are in remission, human platelet-derived growth factor may be used. Intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide or cyclosporine solution also can be helpful. Cyclosporin A was used as a systemic monotherapy to treat a 48-year-old man and 50-year-old woman with the idiopathic form of PPG. After 3 months of treatment, PPG had completely resolved and there were no major side effects.8 Other potential topical therapies that control inflammation and promote wound healing include benzoyl peroxide, chlormethine (topical alkylating agent and nitrogen mustard that has anti-inflammatory properties), nicotine, and 5-aminosalicylic acid. If an ulcer becomes infected, empiric antibiotic therapy should be given immediately and adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results.4

Systemic therapy should be considered in patients who do not respond to topical or local interventions, have a rapid and severe course, or have an active underlying bowel disease. Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) has proved to be one of the most successful drugs used to treat PPG. Treatment should be continued until complete lesion healing, and low-dose maintenance therapy should be administered in recurrent cases. Intravenous corticosteroid therapy—hydrocortisone 100 mg 4 times daily or pulse therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/d)—can be used for up to 5 days and may be effective. Oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily may be helpful as an adjunctive therapy to corticosteroids. When corticosteroids fail, oral cyclosporine 3 to 5 mg/kg/d often is prescribed. Studies have shown that patients demonstrate clinical improvement within 3 weeks of cyclosporine initiation, and it has been shown further to be more effective than either azathioprine or methotrexate.4,8

Infliximab, a chimeric antibody that binds both circulating and tissue-bound TNF-α, has been shown to effectively treat PPG. A clinical trial conducted by Brooklyn et al9 found that 46% of patients (6/13) treated with infliximab responded compared with only 6% in a placebo control group (1/17). Although infliximab may result in sepsis, the benefits far outweigh the risks, especially for patients with steroid-refractory PPG.4 Adalimumab is a human monoclonal IgG1 antibody to TNF-α that neutralizes its function by blocking the interaction between the molecule and its receptor. Many clinical studies have shown that adalimumab induces and maintains a clinical response in patients with active Crohn disease. The biologic proved to be effective in our patient, but it is associated with potential side effects that should be monitored including injection-site reactions, pruritus, leukopenia, urticaria, and rare instances of alopecia.10 Etanercept is another potentially effective biologic agent.7 Plasma exchange, immunoglobulin infusion, and interferon-alfa therapy also can be used in refractory PPG cases, though data on these treatments are very limited.4

Unlike routine pyoderma gangrenosum—for which surgical intervention is contraindicated—surgical intervention may be appropriate for the peristomal variant. Surgical treatment options include stoma revision and/or relocation; however, both of these procedures are accompanied by failure rates ranging from 40% to 100%.5 Removal of a diseased intestinal segment, especially one with active IBD, may result in healing of the skin lesion. In our patient, removal of the residual and diseased J-pouch was part of the management plan. However,it generally is recommended that any surgical intervention be accompanied by medical therapy including oral metronidazole 500 mg/d and concomitant administration of an immunosuppressant.1,3

Because PPG tends to recur, long-term maintenance therapy should always be considered. Pain reduction, anemia correction, proper nutrition, and management of associated and underlying diseases should be performed. Meticulous care of the stoma and prevention of leaks also should be emphasized. Overall, if PPG is detected and diagnosed early as well as treated appropriately and aggressively, the patient likely will have a good prognosis.4

- Sheldon DG, Sawchuk LL, Kozarek RA, et al. Twenty cases of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: diagnostic implications and management. Arch Surg. 2000;135:564-569.

- Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP. Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA. 2000;284:1546-1548.

- Afifi L, Sanchez IM, Wallace MM, et al. Diagnosis and management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1195-1204.

- Wu XR, Shen B. Diagnosis and management of parastomal pyoderma gangrenosum. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2013;1:1-8.

- Javed A, Pal S, Ahuja V, et al. Management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: two different approaches for the same clinical problem. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32:153-156.

- Toh JW, Whiteley I. Devastating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges in diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:A19-A20.

- DeMartyn LE, Faller NA, Miller L. Treating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed prednisone: a report of three cases. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2014;60:50-54.

- V’lckova-Laskoska MT, Laskoski DS, Caca-Biljanovska NG, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with cyclosporin A.Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:541-555.

- Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MGS, Shetty A, at al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505-509.

- Alkhouri N, Hupertz V, Mahajan L. Adalimumab treatment for peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:803-806.

To the Editor:

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) is a rare entity first described in 1984.1 Lesions usually begin as pustules that coalesce into an erythematous skin ulceration that contains purulent material. The lesion appears on the skin that surrounds an abdominal stoma. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically is associated with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cancer, blood dyscrasia, diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis.2 We describe a case of PPG following an ileostomy in a patient with colon cancer and a related history of Crohn disease.

A 32-year-old woman presented to a dermatology office with a spontaneously painful, 3.2-cm ulceration that was extremely tender to palpation, located immediately adjacent to the site of an ileostomy (Figure). The patient had a history of refractory constipation that failed to respond to standard conservative measures 4 years prior. She underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed a 6.5-cm, irregularly shaped, exophytic mass in the rectosigmoid portion of the colon. Histopathologic examination of several biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, and additional evaluation determined the cancer to be stage IIB. She had a medical history of pancolonic Crohn disease since high school that was treated with periodic infusions of infliximab at the standard dose of 5 mg/kg. Colon cancer treatment consisted of preoperative radiotherapy, complete colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis, and creation of a J-pouch and formation of a temporary ileostomy, along with postoperative capecitabine chemotherapy.

The ileostomy eventually was reversed, and the patient did well for 3 years. When the patient developed severe abdominal pain, the J-pouch was examined and found to be remarkably involved with Crohn disease. However, during the colonoscopy, the J-pouch was inadvertently punctured, leading to the formation of a large pelvic abscess. The latter necessitated diversion of stool, and the patient had the original ileostomy recreated.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, various consultants suspected the ulceration was possibly a deep fungal infection, cutaneous Crohn disease, a factitious ulceration, or acute allergic contact dermatitis related to some element of ostomy care. However, dermatologic consultation suggested that the troublesome lesion was classic PPG and recommended administration of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α–blocking agent and concomitant intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide.

The patient was treated with subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg once weekly, and received near weekly subcutaneous injections of triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL. After 2 months, the discomfort subsided, and the ulceration gradually resolved into a depressed scar. Eighteen months later, the scar was barely perceptible as a minimally erythematous depression. Adalimumab ultimately was discontinued, as the residual J-pouch was removed, and the biologic drug was associated with extensive alopecia areata–like hair loss. There has been no recurrence of PPG in the 40 months since clinical resolution.

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum, which is characterized by chronic, persistent, or recurrent painful ulceration(s) close to an abdominal stoma. In total, fewer than 100 cases of PPG have been reported thus far in the readily available medical literature.3 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the most frequently diagnosed systemic condition associated with PPG, though other associated conditions include diverticular disease, abdominal malignancy, and neurologic dysfunction. Approximately 2% to 4.3% of all patients who have stoma creation surgery related to underlying IBD develop PPG. It is estimated that the yearly incidence rate of PPG in all abdominal stomas is quite low (approximately 0.6%).4

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum can occur at any age, but it tends to predominate in young to middle-aged adults, with a slight female predilection. The etiology and pathogenesis of PPG are largely unknown, though studies have shown that an abnormal immune response may be critical to its development. Risk factors for PPG are not well defined but potentially include autoimmune disorders, a high body mass index, and females or African Americans with IBD.4 Because PPG does not have characteristic histopathologic features, it is a diagnosis of exclusion that is based on the clinical examination and histologic findings that rule out other potential disorders.

There are 4 types of PPG based on the clinical and histopathologic characteristics: ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum tends to be either ulcerative or vegetative, with ulcerative being by far the predominant type. The onset of PPG is quite variable, occurring a few weeks to several years after stoma formation.5 Ulcer size can range from less than 3 cm to 30 cm.4 Lesions begin as deep painful nodules or as superficial hemorrhagic pustules, either idiopathic or following ostensibly minimal trauma. Subsequently, they become necrotic and form an ulceration. The ulcers can be single or multiple lesions, typically with erythematous raised borders and purulent discharge. The ulcers are extremely painful and rapidly progressive. After the ulcers heal, they often leave a characteristic weblike atrophic scar that can break down further following any form of irritation or trauma.5

A prompt diagnosis of PPG is important. A diagnosis of PPG should be considered when dealing with a noninfectious ulcer surrounding a stoma in patients with IBD or other autoimmune conditions.6 Because PPG is a rare skin disorder, it is likely to be missed and lead to unnecessary diagnostic workup and a delay in proper therapy. In our patient, a diagnosis of PPG was overlooked for other infectious and autoimmune causes. The diagnostic evaluation of a patient with PPG is based on 3 principles: (1) ruling out other causes of a peristomal ulcer, such as an abscess, contact dermatitis, or wound infection; (2) determining whether there is an underlying intestinal bowel disease in the stoma; and (3) identifying associated systemic disorders such as vasculitis, erythema nodosum, or similar processes.4 The differential diagnosis depends on the type and stage of PPG and can include malignancy, vasculitis, extraintestinal IBD, infectious disease, and insect bites. A review of the history of the ulcer is helpful in ruling out other diseases, and a colonoscopy or ileoscopy can identify if patients have an underlying active IBD. Swabs for smear and both bacterial and fungal cultures should be taken from the exudate and directly from the ulcer base. Biopsy of the ulcer also helps to exclude alternative diagnoses.6

The primary goals of treating PPG include to reduce pain and the risk for secondary infection, increase pouch adherence, and decrease purulent exudate.7 Although there is not one well-defined optimal therapeutic intervention, there are a variety of effective approaches that may be considered and used. In mild cases, management methods such as dressings, topical agents, or intralesional steroids may be capable of controlling the disease. Daily wound care is important. Moisture-retentive dressings can control pain, induce collagen formation, promote angiogenesis, and prevent contamination. Cleaning the wound with sterile saline and applying an anti-infective agent also may be effective. Application of ultrapotent topical steroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% can be used in patients without concomitant secondary infection. In patients who are in remission, human platelet-derived growth factor may be used. Intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide or cyclosporine solution also can be helpful. Cyclosporin A was used as a systemic monotherapy to treat a 48-year-old man and 50-year-old woman with the idiopathic form of PPG. After 3 months of treatment, PPG had completely resolved and there were no major side effects.8 Other potential topical therapies that control inflammation and promote wound healing include benzoyl peroxide, chlormethine (topical alkylating agent and nitrogen mustard that has anti-inflammatory properties), nicotine, and 5-aminosalicylic acid. If an ulcer becomes infected, empiric antibiotic therapy should be given immediately and adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results.4

Systemic therapy should be considered in patients who do not respond to topical or local interventions, have a rapid and severe course, or have an active underlying bowel disease. Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) has proved to be one of the most successful drugs used to treat PPG. Treatment should be continued until complete lesion healing, and low-dose maintenance therapy should be administered in recurrent cases. Intravenous corticosteroid therapy—hydrocortisone 100 mg 4 times daily or pulse therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/d)—can be used for up to 5 days and may be effective. Oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily may be helpful as an adjunctive therapy to corticosteroids. When corticosteroids fail, oral cyclosporine 3 to 5 mg/kg/d often is prescribed. Studies have shown that patients demonstrate clinical improvement within 3 weeks of cyclosporine initiation, and it has been shown further to be more effective than either azathioprine or methotrexate.4,8

Infliximab, a chimeric antibody that binds both circulating and tissue-bound TNF-α, has been shown to effectively treat PPG. A clinical trial conducted by Brooklyn et al9 found that 46% of patients (6/13) treated with infliximab responded compared with only 6% in a placebo control group (1/17). Although infliximab may result in sepsis, the benefits far outweigh the risks, especially for patients with steroid-refractory PPG.4 Adalimumab is a human monoclonal IgG1 antibody to TNF-α that neutralizes its function by blocking the interaction between the molecule and its receptor. Many clinical studies have shown that adalimumab induces and maintains a clinical response in patients with active Crohn disease. The biologic proved to be effective in our patient, but it is associated with potential side effects that should be monitored including injection-site reactions, pruritus, leukopenia, urticaria, and rare instances of alopecia.10 Etanercept is another potentially effective biologic agent.7 Plasma exchange, immunoglobulin infusion, and interferon-alfa therapy also can be used in refractory PPG cases, though data on these treatments are very limited.4

Unlike routine pyoderma gangrenosum—for which surgical intervention is contraindicated—surgical intervention may be appropriate for the peristomal variant. Surgical treatment options include stoma revision and/or relocation; however, both of these procedures are accompanied by failure rates ranging from 40% to 100%.5 Removal of a diseased intestinal segment, especially one with active IBD, may result in healing of the skin lesion. In our patient, removal of the residual and diseased J-pouch was part of the management plan. However,it generally is recommended that any surgical intervention be accompanied by medical therapy including oral metronidazole 500 mg/d and concomitant administration of an immunosuppressant.1,3

Because PPG tends to recur, long-term maintenance therapy should always be considered. Pain reduction, anemia correction, proper nutrition, and management of associated and underlying diseases should be performed. Meticulous care of the stoma and prevention of leaks also should be emphasized. Overall, if PPG is detected and diagnosed early as well as treated appropriately and aggressively, the patient likely will have a good prognosis.4

To the Editor:

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) is a rare entity first described in 1984.1 Lesions usually begin as pustules that coalesce into an erythematous skin ulceration that contains purulent material. The lesion appears on the skin that surrounds an abdominal stoma. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically is associated with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cancer, blood dyscrasia, diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis.2 We describe a case of PPG following an ileostomy in a patient with colon cancer and a related history of Crohn disease.

A 32-year-old woman presented to a dermatology office with a spontaneously painful, 3.2-cm ulceration that was extremely tender to palpation, located immediately adjacent to the site of an ileostomy (Figure). The patient had a history of refractory constipation that failed to respond to standard conservative measures 4 years prior. She underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed a 6.5-cm, irregularly shaped, exophytic mass in the rectosigmoid portion of the colon. Histopathologic examination of several biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, and additional evaluation determined the cancer to be stage IIB. She had a medical history of pancolonic Crohn disease since high school that was treated with periodic infusions of infliximab at the standard dose of 5 mg/kg. Colon cancer treatment consisted of preoperative radiotherapy, complete colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis, and creation of a J-pouch and formation of a temporary ileostomy, along with postoperative capecitabine chemotherapy.

The ileostomy eventually was reversed, and the patient did well for 3 years. When the patient developed severe abdominal pain, the J-pouch was examined and found to be remarkably involved with Crohn disease. However, during the colonoscopy, the J-pouch was inadvertently punctured, leading to the formation of a large pelvic abscess. The latter necessitated diversion of stool, and the patient had the original ileostomy recreated.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, various consultants suspected the ulceration was possibly a deep fungal infection, cutaneous Crohn disease, a factitious ulceration, or acute allergic contact dermatitis related to some element of ostomy care. However, dermatologic consultation suggested that the troublesome lesion was classic PPG and recommended administration of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α–blocking agent and concomitant intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide.

The patient was treated with subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg once weekly, and received near weekly subcutaneous injections of triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL. After 2 months, the discomfort subsided, and the ulceration gradually resolved into a depressed scar. Eighteen months later, the scar was barely perceptible as a minimally erythematous depression. Adalimumab ultimately was discontinued, as the residual J-pouch was removed, and the biologic drug was associated with extensive alopecia areata–like hair loss. There has been no recurrence of PPG in the 40 months since clinical resolution.

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum, which is characterized by chronic, persistent, or recurrent painful ulceration(s) close to an abdominal stoma. In total, fewer than 100 cases of PPG have been reported thus far in the readily available medical literature.3 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the most frequently diagnosed systemic condition associated with PPG, though other associated conditions include diverticular disease, abdominal malignancy, and neurologic dysfunction. Approximately 2% to 4.3% of all patients who have stoma creation surgery related to underlying IBD develop PPG. It is estimated that the yearly incidence rate of PPG in all abdominal stomas is quite low (approximately 0.6%).4

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum can occur at any age, but it tends to predominate in young to middle-aged adults, with a slight female predilection. The etiology and pathogenesis of PPG are largely unknown, though studies have shown that an abnormal immune response may be critical to its development. Risk factors for PPG are not well defined but potentially include autoimmune disorders, a high body mass index, and females or African Americans with IBD.4 Because PPG does not have characteristic histopathologic features, it is a diagnosis of exclusion that is based on the clinical examination and histologic findings that rule out other potential disorders.

There are 4 types of PPG based on the clinical and histopathologic characteristics: ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum tends to be either ulcerative or vegetative, with ulcerative being by far the predominant type. The onset of PPG is quite variable, occurring a few weeks to several years after stoma formation.5 Ulcer size can range from less than 3 cm to 30 cm.4 Lesions begin as deep painful nodules or as superficial hemorrhagic pustules, either idiopathic or following ostensibly minimal trauma. Subsequently, they become necrotic and form an ulceration. The ulcers can be single or multiple lesions, typically with erythematous raised borders and purulent discharge. The ulcers are extremely painful and rapidly progressive. After the ulcers heal, they often leave a characteristic weblike atrophic scar that can break down further following any form of irritation or trauma.5

A prompt diagnosis of PPG is important. A diagnosis of PPG should be considered when dealing with a noninfectious ulcer surrounding a stoma in patients with IBD or other autoimmune conditions.6 Because PPG is a rare skin disorder, it is likely to be missed and lead to unnecessary diagnostic workup and a delay in proper therapy. In our patient, a diagnosis of PPG was overlooked for other infectious and autoimmune causes. The diagnostic evaluation of a patient with PPG is based on 3 principles: (1) ruling out other causes of a peristomal ulcer, such as an abscess, contact dermatitis, or wound infection; (2) determining whether there is an underlying intestinal bowel disease in the stoma; and (3) identifying associated systemic disorders such as vasculitis, erythema nodosum, or similar processes.4 The differential diagnosis depends on the type and stage of PPG and can include malignancy, vasculitis, extraintestinal IBD, infectious disease, and insect bites. A review of the history of the ulcer is helpful in ruling out other diseases, and a colonoscopy or ileoscopy can identify if patients have an underlying active IBD. Swabs for smear and both bacterial and fungal cultures should be taken from the exudate and directly from the ulcer base. Biopsy of the ulcer also helps to exclude alternative diagnoses.6

The primary goals of treating PPG include to reduce pain and the risk for secondary infection, increase pouch adherence, and decrease purulent exudate.7 Although there is not one well-defined optimal therapeutic intervention, there are a variety of effective approaches that may be considered and used. In mild cases, management methods such as dressings, topical agents, or intralesional steroids may be capable of controlling the disease. Daily wound care is important. Moisture-retentive dressings can control pain, induce collagen formation, promote angiogenesis, and prevent contamination. Cleaning the wound with sterile saline and applying an anti-infective agent also may be effective. Application of ultrapotent topical steroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% can be used in patients without concomitant secondary infection. In patients who are in remission, human platelet-derived growth factor may be used. Intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide or cyclosporine solution also can be helpful. Cyclosporin A was used as a systemic monotherapy to treat a 48-year-old man and 50-year-old woman with the idiopathic form of PPG. After 3 months of treatment, PPG had completely resolved and there were no major side effects.8 Other potential topical therapies that control inflammation and promote wound healing include benzoyl peroxide, chlormethine (topical alkylating agent and nitrogen mustard that has anti-inflammatory properties), nicotine, and 5-aminosalicylic acid. If an ulcer becomes infected, empiric antibiotic therapy should be given immediately and adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results.4

Systemic therapy should be considered in patients who do not respond to topical or local interventions, have a rapid and severe course, or have an active underlying bowel disease. Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) has proved to be one of the most successful drugs used to treat PPG. Treatment should be continued until complete lesion healing, and low-dose maintenance therapy should be administered in recurrent cases. Intravenous corticosteroid therapy—hydrocortisone 100 mg 4 times daily or pulse therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/d)—can be used for up to 5 days and may be effective. Oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily may be helpful as an adjunctive therapy to corticosteroids. When corticosteroids fail, oral cyclosporine 3 to 5 mg/kg/d often is prescribed. Studies have shown that patients demonstrate clinical improvement within 3 weeks of cyclosporine initiation, and it has been shown further to be more effective than either azathioprine or methotrexate.4,8

Infliximab, a chimeric antibody that binds both circulating and tissue-bound TNF-α, has been shown to effectively treat PPG. A clinical trial conducted by Brooklyn et al9 found that 46% of patients (6/13) treated with infliximab responded compared with only 6% in a placebo control group (1/17). Although infliximab may result in sepsis, the benefits far outweigh the risks, especially for patients with steroid-refractory PPG.4 Adalimumab is a human monoclonal IgG1 antibody to TNF-α that neutralizes its function by blocking the interaction between the molecule and its receptor. Many clinical studies have shown that adalimumab induces and maintains a clinical response in patients with active Crohn disease. The biologic proved to be effective in our patient, but it is associated with potential side effects that should be monitored including injection-site reactions, pruritus, leukopenia, urticaria, and rare instances of alopecia.10 Etanercept is another potentially effective biologic agent.7 Plasma exchange, immunoglobulin infusion, and interferon-alfa therapy also can be used in refractory PPG cases, though data on these treatments are very limited.4

Unlike routine pyoderma gangrenosum—for which surgical intervention is contraindicated—surgical intervention may be appropriate for the peristomal variant. Surgical treatment options include stoma revision and/or relocation; however, both of these procedures are accompanied by failure rates ranging from 40% to 100%.5 Removal of a diseased intestinal segment, especially one with active IBD, may result in healing of the skin lesion. In our patient, removal of the residual and diseased J-pouch was part of the management plan. However,it generally is recommended that any surgical intervention be accompanied by medical therapy including oral metronidazole 500 mg/d and concomitant administration of an immunosuppressant.1,3

Because PPG tends to recur, long-term maintenance therapy should always be considered. Pain reduction, anemia correction, proper nutrition, and management of associated and underlying diseases should be performed. Meticulous care of the stoma and prevention of leaks also should be emphasized. Overall, if PPG is detected and diagnosed early as well as treated appropriately and aggressively, the patient likely will have a good prognosis.4

- Sheldon DG, Sawchuk LL, Kozarek RA, et al. Twenty cases of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: diagnostic implications and management. Arch Surg. 2000;135:564-569.

- Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP. Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA. 2000;284:1546-1548.

- Afifi L, Sanchez IM, Wallace MM, et al. Diagnosis and management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1195-1204.

- Wu XR, Shen B. Diagnosis and management of parastomal pyoderma gangrenosum. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2013;1:1-8.

- Javed A, Pal S, Ahuja V, et al. Management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: two different approaches for the same clinical problem. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32:153-156.

- Toh JW, Whiteley I. Devastating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges in diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:A19-A20.

- DeMartyn LE, Faller NA, Miller L. Treating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed prednisone: a report of three cases. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2014;60:50-54.

- V’lckova-Laskoska MT, Laskoski DS, Caca-Biljanovska NG, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with cyclosporin A.Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:541-555.

- Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MGS, Shetty A, at al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505-509.

- Alkhouri N, Hupertz V, Mahajan L. Adalimumab treatment for peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:803-806.

- Sheldon DG, Sawchuk LL, Kozarek RA, et al. Twenty cases of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: diagnostic implications and management. Arch Surg. 2000;135:564-569.

- Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP. Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA. 2000;284:1546-1548.

- Afifi L, Sanchez IM, Wallace MM, et al. Diagnosis and management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1195-1204.

- Wu XR, Shen B. Diagnosis and management of parastomal pyoderma gangrenosum. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2013;1:1-8.

- Javed A, Pal S, Ahuja V, et al. Management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: two different approaches for the same clinical problem. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32:153-156.

- Toh JW, Whiteley I. Devastating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges in diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:A19-A20.

- DeMartyn LE, Faller NA, Miller L. Treating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed prednisone: a report of three cases. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2014;60:50-54.

- V’lckova-Laskoska MT, Laskoski DS, Caca-Biljanovska NG, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with cyclosporin A.Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:541-555.

- Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MGS, Shetty A, at al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505-509.

- Alkhouri N, Hupertz V, Mahajan L. Adalimumab treatment for peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:803-806.

Practice Points

- A pyoderma gangrenosum subtype occurs in close proximity to an abdominal stoma.

- Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is a diagnosis of exclusion.

- Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically responds best to tumor necrosis factor α blockers and corticosteroid therapy (intralesional and systemic).

Dog Walking Can Be Hazardous to Cutaneous Health

Studies have recommended dog walking as an activity designed to improve the overall health of older adults.1,2 Benefits purportedly associated with dog walking include lower body mass index, fewer chronic diseases, reduction in the number of physician visits, and decreased limitations of activities of daily living.2 The Arthritis Foundation even recommends dog walking to relieve arthritis symptoms.3 Of course, dogs also provide comfort in companionship, and dog walking can be an enjoyable way for a pet and owner to spend time together.

However, this seemingly benign activity poses a notable and perhaps grossly underrecognized risk for injury in older adults. The annual number of patients 65 years and older who presented to US emergency departments (EDs) for fractures directly associated with walking leashed dogs more than doubled from 2004 to 2017.4 Interestingly, this dramatic increase parallels a nationwide trend in dog ownership demographics. Between 2006 and 2016, the median age of dog owners in the United States rose from 46 to 49 years.5

These trends raise concern for more than just the health of older Americans’ bones. Intuitively, a dog- walking accident that results in a bone fracture will likely also lead to some degree of skin trauma. Older adults have thin fragile skin due to flattening of the dermoepidermal junction and disintegration or degeneration of dermal collagen and elastin.6 This loss of connective tissue as well as subcutaneous tissue in some body areas facilitates shearing injury; concurrently, weakened perivascular support increases the risk for vascular injury and bruising.7 Therefore, when an older person falls while walking a dog, trauma can easily damage delicate aged skin.

Older adults are particularly susceptible to falls, the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries in this age group.8 There are multiple risk factors for falls, including polypharmacy, impaired balance and gait, visual impairments, and cognitive decline, among others.9

Also, many older adults with atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism take an anticoagulant drug to prevent stroke. The use of anticoagulants is associated with an increased risk for bleeding, ranging from minor cutaneous bleeding to fatal intracranial hemorrhage.10

A predisposition to falling and bleeding can be hazardous for a dog owner whose excited pet suddenly jumps, runs, or scratches. The use of a leash, mandatory in many urban jurisdictions, tethers the human to the dog, which expedites a fall associated with any sudden, forceful forward or lateral movement by the dog. The following case reports describe a variety of cutaneous injuries experienced by older adults while dog walking.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 79-year-old woman was quietly walking her dog when the dog spotted a squirrel climbing a tree. The dog became excited, turned to the owner, and jumped on her, which caused the dog’s claws to dig into the owner’s fragile forearm skin, creating several superficial but painful abrasions and lacerations (Figure 1). These injuries healed well with conservative therapy including application of an occlusive ointment.

Patient 2

A 68-year-old woman was walking her dog when the dog saw a cat running across the street. The dog suddenly leaped toward the cat, causing the owner to fall forward as the animal’s momentum was transferred through the leash. The owner fell awkwardly on her side, leading to an extensive abrasion and contusion of the shoulder (Figure 2). The lesion healed well with conservative management, albeit with moderate postinflammatory hypochromia.

Patient 3

A 65-year-old woman was walking her dog and they heard a loud noise. The dog started to run forward—likely, startled. The owner did not fall, but the leash, which was wrapped around her hand, exerted enough force to avulse a 5×3-cm piece of skin from the dorsum of the hand (Figure 3). The painful abrasion and concomitant bruise eventually healed with conservative management but left a noticeable hemosiderin stain.

Patient 4

A 66-year-old man was walking a large Rottweiler when the dog lurched toward another dog that was being walked across the street. The owner, taken by surprise by this sudden motion, fell on the concrete sidewalk and was dragged several feet by the dog. This unexpected and off-balance fall caused multiple injuries, including bruises on the upper arm, a large avulsion of epidermal forearm skin (Figure 4), a gouge in the dermis down to fat, and a large abrasion of the contralateral knee. The patient received a tetanus booster and conservative therapy. The affected area healed with an atrophic hypopigmented scar.

Patient 5

An 82-year-old woman with known atrial fibrillation who was taking chronic anticoagulation medication was walking her dog. For no apparent reason, the dog sped up the pace. The woman lost her balance and fell face first onto the sidewalk. She did not lose consciousness but did develop a large bruise on the forehead with a tender fluctuant nodule in the center (Figure 5).

The patient presented the next day, requesting drainage of the forehead hematoma. However, a brief review of systems revealed a persistent severe headache and nausea with vomiting since the prior day. She was immediately transported to the nearest ED where complete neurologic workup revealed a moderate-sized subdural hematoma that was treated by trephination. Recovery was uneventful.

Comment

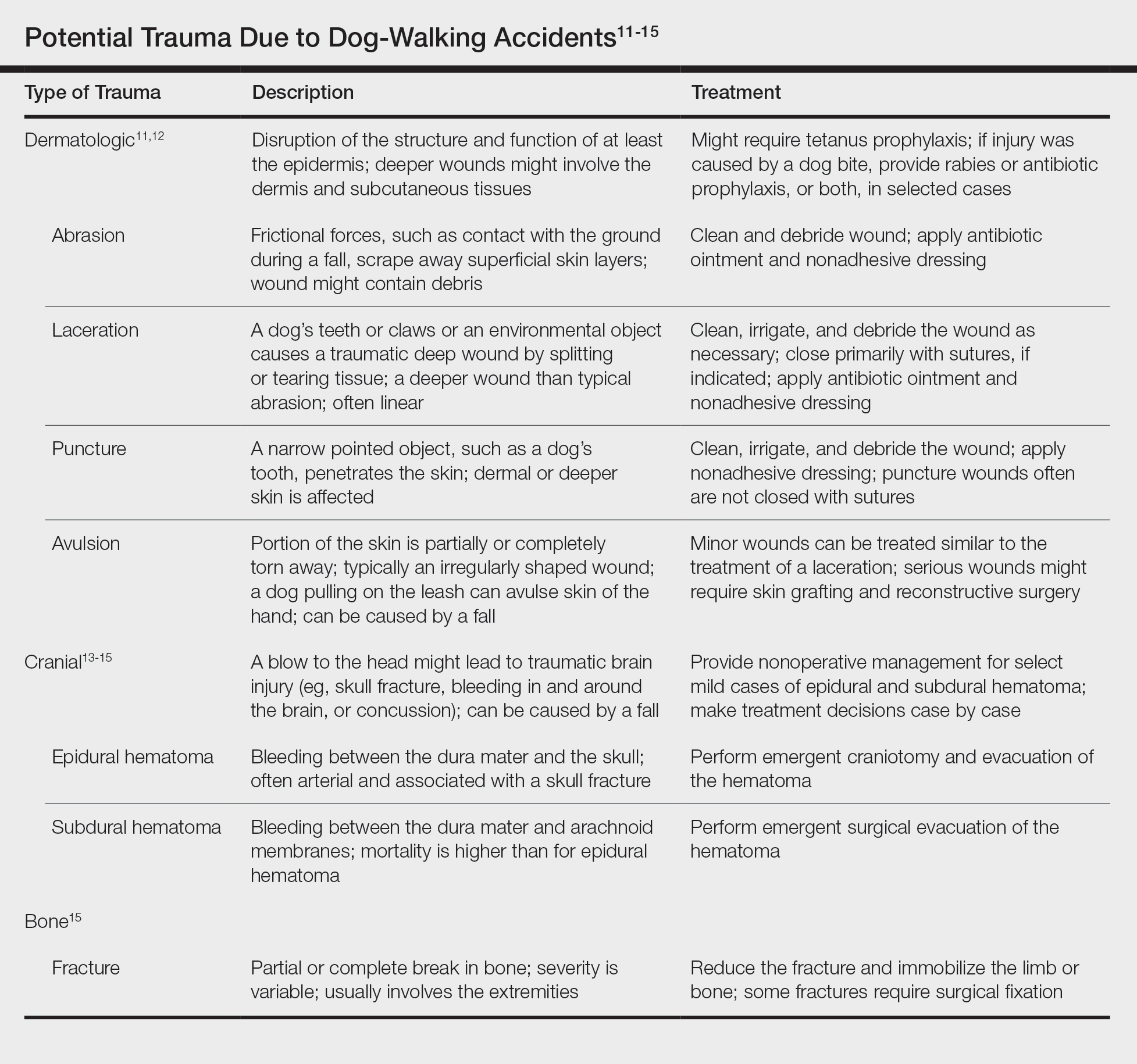

These 5 cases illustrate the notable skin (and neurologic) trauma that can occur due to a dog-walking accident (Table).11-15

Regrettably, obtaining an accurate national estimate of the annual incidence of cutaneous dog-walking injuries is difficult. Researchers who have described the rise in dog walking–associated bone fractures queried the US Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database for its numbers.4 This public database generates incidence estimates of activity- or product-related injuries based on data from a nationally representative sample of approximately 100 hospital EDs.16

We queried the same database for the diagnoses avulsion, abrasion or contusion, and laceration.17 These terms were searched in association with pet supplies, including leashes, and patients 65 years and older. This search yielded fewer than 800 total cases from 2008 to 2017, resulting in unreliable estimates for each year.

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database no doubt underestimates the true incidence of dog walking–related skin trauma; the great majority of patients with cutaneous injury, as illustrated here, likely never present to the ED, unlike patients with bone fracture. Moreover, data do not capture cases handled by providers outside the ED and self-treated injuries.

In the absence of accurate estimates of cutaneous morbidity related to dog-walking injury, the case reports here are clearly a cautionary tale. Physicians and older adults need to be cognizant of the hazards of this activity. Providers should discuss with older patients the potential risks of dog walking before recommending or condoning this exercise.

The presence of other comorbidities that could hamper a person’s ability to control a leashed dog warrants special consideration. Older prospective dog owners might consider adopting a small, easily manageable breed. These measures can help protect older adults’ fragile skin (and bones) from avoidable minor to potentially life-threatening trauma.

- Christian H, Bauman A, Epping JN, et al. Encouraging dog walking for health promotion and disease prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;12:233-243.

- Curl AL, Bibbo J, Johnson RA. Dog walking, the human–animal bond and older adults’ physical health. Gerontologist. 2017;57:930-939.

- Dunkin MA. Walking strategies. Arthritis Foundation website. https://arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/physical-activity/walking/5-walking-strategies. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Pirruccio K, Yoon YM, Ahn J. Fractures in elderly Americans associated with walking leashed dogs. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:458-459.

- Sprinkle D. Pet owner demographics get grayer, more golden. Petfood Industry website. https://www.petfoodindustry.com/articles/6315-pet-owner-demographics-get-grayer-more-golden?v=preview. Published March 10, 2017. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Quan T, Fisher GJ. Role of age-associated alterations of the dermal extracellular matrix microenvironment in human skin aging: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2015;61:427-434.

- Aging & painful skin. Cleveland Clinic website. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16725-aging--painful-skin. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and fall injuries among adults aged ≥65 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:993-998.

- Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75:51-61.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; . 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:E1-E76.

- Armstrong DG, Meyr AJ. Basic principles of wound management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/basic-principles-of-wound-management. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Trott AT. Wounds and Lacerations: Emergency Care and Closure. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Head injuries in adults: what is it? Harvard Health Publishing website. www.health.harvard.edu/a_to_z/head-injury-in-adults-a-to-z. Published October 2018. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- McBride W. Intracranial epidural hematoma in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intracranial-epidural-hematoma-in-adults. Updated July 23, 2018. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- McBride W. Subdural hematoma in adults: prognosis and management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/subdural-hematoma-in-adults-prognosis-and-management. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Schroeder T, Ault K. The NEISS sample: design and implementation. Washington, DC: US Consumer Product Safety Commission, Division of Hazard and Injury Data Systems; June 2001. https://cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_2001d011-6b6.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS). Bethesda, MD: US Consumer Product Safety Commission; 2018. https://www.cpsc.gov/Research--Statistics/NEISS-Injury-Data. Accessed March 16, 2020.

Studies have recommended dog walking as an activity designed to improve the overall health of older adults.1,2 Benefits purportedly associated with dog walking include lower body mass index, fewer chronic diseases, reduction in the number of physician visits, and decreased limitations of activities of daily living.2 The Arthritis Foundation even recommends dog walking to relieve arthritis symptoms.3 Of course, dogs also provide comfort in companionship, and dog walking can be an enjoyable way for a pet and owner to spend time together.

However, this seemingly benign activity poses a notable and perhaps grossly underrecognized risk for injury in older adults. The annual number of patients 65 years and older who presented to US emergency departments (EDs) for fractures directly associated with walking leashed dogs more than doubled from 2004 to 2017.4 Interestingly, this dramatic increase parallels a nationwide trend in dog ownership demographics. Between 2006 and 2016, the median age of dog owners in the United States rose from 46 to 49 years.5

These trends raise concern for more than just the health of older Americans’ bones. Intuitively, a dog- walking accident that results in a bone fracture will likely also lead to some degree of skin trauma. Older adults have thin fragile skin due to flattening of the dermoepidermal junction and disintegration or degeneration of dermal collagen and elastin.6 This loss of connective tissue as well as subcutaneous tissue in some body areas facilitates shearing injury; concurrently, weakened perivascular support increases the risk for vascular injury and bruising.7 Therefore, when an older person falls while walking a dog, trauma can easily damage delicate aged skin.

Older adults are particularly susceptible to falls, the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries in this age group.8 There are multiple risk factors for falls, including polypharmacy, impaired balance and gait, visual impairments, and cognitive decline, among others.9

Also, many older adults with atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism take an anticoagulant drug to prevent stroke. The use of anticoagulants is associated with an increased risk for bleeding, ranging from minor cutaneous bleeding to fatal intracranial hemorrhage.10

A predisposition to falling and bleeding can be hazardous for a dog owner whose excited pet suddenly jumps, runs, or scratches. The use of a leash, mandatory in many urban jurisdictions, tethers the human to the dog, which expedites a fall associated with any sudden, forceful forward or lateral movement by the dog. The following case reports describe a variety of cutaneous injuries experienced by older adults while dog walking.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 79-year-old woman was quietly walking her dog when the dog spotted a squirrel climbing a tree. The dog became excited, turned to the owner, and jumped on her, which caused the dog’s claws to dig into the owner’s fragile forearm skin, creating several superficial but painful abrasions and lacerations (Figure 1). These injuries healed well with conservative therapy including application of an occlusive ointment.

Patient 2

A 68-year-old woman was walking her dog when the dog saw a cat running across the street. The dog suddenly leaped toward the cat, causing the owner to fall forward as the animal’s momentum was transferred through the leash. The owner fell awkwardly on her side, leading to an extensive abrasion and contusion of the shoulder (Figure 2). The lesion healed well with conservative management, albeit with moderate postinflammatory hypochromia.

Patient 3

A 65-year-old woman was walking her dog and they heard a loud noise. The dog started to run forward—likely, startled. The owner did not fall, but the leash, which was wrapped around her hand, exerted enough force to avulse a 5×3-cm piece of skin from the dorsum of the hand (Figure 3). The painful abrasion and concomitant bruise eventually healed with conservative management but left a noticeable hemosiderin stain.

Patient 4

A 66-year-old man was walking a large Rottweiler when the dog lurched toward another dog that was being walked across the street. The owner, taken by surprise by this sudden motion, fell on the concrete sidewalk and was dragged several feet by the dog. This unexpected and off-balance fall caused multiple injuries, including bruises on the upper arm, a large avulsion of epidermal forearm skin (Figure 4), a gouge in the dermis down to fat, and a large abrasion of the contralateral knee. The patient received a tetanus booster and conservative therapy. The affected area healed with an atrophic hypopigmented scar.

Patient 5

An 82-year-old woman with known atrial fibrillation who was taking chronic anticoagulation medication was walking her dog. For no apparent reason, the dog sped up the pace. The woman lost her balance and fell face first onto the sidewalk. She did not lose consciousness but did develop a large bruise on the forehead with a tender fluctuant nodule in the center (Figure 5).

The patient presented the next day, requesting drainage of the forehead hematoma. However, a brief review of systems revealed a persistent severe headache and nausea with vomiting since the prior day. She was immediately transported to the nearest ED where complete neurologic workup revealed a moderate-sized subdural hematoma that was treated by trephination. Recovery was uneventful.

Comment

These 5 cases illustrate the notable skin (and neurologic) trauma that can occur due to a dog-walking accident (Table).11-15

Regrettably, obtaining an accurate national estimate of the annual incidence of cutaneous dog-walking injuries is difficult. Researchers who have described the rise in dog walking–associated bone fractures queried the US Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database for its numbers.4 This public database generates incidence estimates of activity- or product-related injuries based on data from a nationally representative sample of approximately 100 hospital EDs.16

We queried the same database for the diagnoses avulsion, abrasion or contusion, and laceration.17 These terms were searched in association with pet supplies, including leashes, and patients 65 years and older. This search yielded fewer than 800 total cases from 2008 to 2017, resulting in unreliable estimates for each year.

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database no doubt underestimates the true incidence of dog walking–related skin trauma; the great majority of patients with cutaneous injury, as illustrated here, likely never present to the ED, unlike patients with bone fracture. Moreover, data do not capture cases handled by providers outside the ED and self-treated injuries.

In the absence of accurate estimates of cutaneous morbidity related to dog-walking injury, the case reports here are clearly a cautionary tale. Physicians and older adults need to be cognizant of the hazards of this activity. Providers should discuss with older patients the potential risks of dog walking before recommending or condoning this exercise.

The presence of other comorbidities that could hamper a person’s ability to control a leashed dog warrants special consideration. Older prospective dog owners might consider adopting a small, easily manageable breed. These measures can help protect older adults’ fragile skin (and bones) from avoidable minor to potentially life-threatening trauma.

Studies have recommended dog walking as an activity designed to improve the overall health of older adults.1,2 Benefits purportedly associated with dog walking include lower body mass index, fewer chronic diseases, reduction in the number of physician visits, and decreased limitations of activities of daily living.2 The Arthritis Foundation even recommends dog walking to relieve arthritis symptoms.3 Of course, dogs also provide comfort in companionship, and dog walking can be an enjoyable way for a pet and owner to spend time together.

However, this seemingly benign activity poses a notable and perhaps grossly underrecognized risk for injury in older adults. The annual number of patients 65 years and older who presented to US emergency departments (EDs) for fractures directly associated with walking leashed dogs more than doubled from 2004 to 2017.4 Interestingly, this dramatic increase parallels a nationwide trend in dog ownership demographics. Between 2006 and 2016, the median age of dog owners in the United States rose from 46 to 49 years.5

These trends raise concern for more than just the health of older Americans’ bones. Intuitively, a dog- walking accident that results in a bone fracture will likely also lead to some degree of skin trauma. Older adults have thin fragile skin due to flattening of the dermoepidermal junction and disintegration or degeneration of dermal collagen and elastin.6 This loss of connective tissue as well as subcutaneous tissue in some body areas facilitates shearing injury; concurrently, weakened perivascular support increases the risk for vascular injury and bruising.7 Therefore, when an older person falls while walking a dog, trauma can easily damage delicate aged skin.

Older adults are particularly susceptible to falls, the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries in this age group.8 There are multiple risk factors for falls, including polypharmacy, impaired balance and gait, visual impairments, and cognitive decline, among others.9

Also, many older adults with atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism take an anticoagulant drug to prevent stroke. The use of anticoagulants is associated with an increased risk for bleeding, ranging from minor cutaneous bleeding to fatal intracranial hemorrhage.10

A predisposition to falling and bleeding can be hazardous for a dog owner whose excited pet suddenly jumps, runs, or scratches. The use of a leash, mandatory in many urban jurisdictions, tethers the human to the dog, which expedites a fall associated with any sudden, forceful forward or lateral movement by the dog. The following case reports describe a variety of cutaneous injuries experienced by older adults while dog walking.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 79-year-old woman was quietly walking her dog when the dog spotted a squirrel climbing a tree. The dog became excited, turned to the owner, and jumped on her, which caused the dog’s claws to dig into the owner’s fragile forearm skin, creating several superficial but painful abrasions and lacerations (Figure 1). These injuries healed well with conservative therapy including application of an occlusive ointment.

Patient 2

A 68-year-old woman was walking her dog when the dog saw a cat running across the street. The dog suddenly leaped toward the cat, causing the owner to fall forward as the animal’s momentum was transferred through the leash. The owner fell awkwardly on her side, leading to an extensive abrasion and contusion of the shoulder (Figure 2). The lesion healed well with conservative management, albeit with moderate postinflammatory hypochromia.

Patient 3

A 65-year-old woman was walking her dog and they heard a loud noise. The dog started to run forward—likely, startled. The owner did not fall, but the leash, which was wrapped around her hand, exerted enough force to avulse a 5×3-cm piece of skin from the dorsum of the hand (Figure 3). The painful abrasion and concomitant bruise eventually healed with conservative management but left a noticeable hemosiderin stain.

Patient 4

A 66-year-old man was walking a large Rottweiler when the dog lurched toward another dog that was being walked across the street. The owner, taken by surprise by this sudden motion, fell on the concrete sidewalk and was dragged several feet by the dog. This unexpected and off-balance fall caused multiple injuries, including bruises on the upper arm, a large avulsion of epidermal forearm skin (Figure 4), a gouge in the dermis down to fat, and a large abrasion of the contralateral knee. The patient received a tetanus booster and conservative therapy. The affected area healed with an atrophic hypopigmented scar.

Patient 5

An 82-year-old woman with known atrial fibrillation who was taking chronic anticoagulation medication was walking her dog. For no apparent reason, the dog sped up the pace. The woman lost her balance and fell face first onto the sidewalk. She did not lose consciousness but did develop a large bruise on the forehead with a tender fluctuant nodule in the center (Figure 5).

The patient presented the next day, requesting drainage of the forehead hematoma. However, a brief review of systems revealed a persistent severe headache and nausea with vomiting since the prior day. She was immediately transported to the nearest ED where complete neurologic workup revealed a moderate-sized subdural hematoma that was treated by trephination. Recovery was uneventful.

Comment

These 5 cases illustrate the notable skin (and neurologic) trauma that can occur due to a dog-walking accident (Table).11-15

Regrettably, obtaining an accurate national estimate of the annual incidence of cutaneous dog-walking injuries is difficult. Researchers who have described the rise in dog walking–associated bone fractures queried the US Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database for its numbers.4 This public database generates incidence estimates of activity- or product-related injuries based on data from a nationally representative sample of approximately 100 hospital EDs.16

We queried the same database for the diagnoses avulsion, abrasion or contusion, and laceration.17 These terms were searched in association with pet supplies, including leashes, and patients 65 years and older. This search yielded fewer than 800 total cases from 2008 to 2017, resulting in unreliable estimates for each year.

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database no doubt underestimates the true incidence of dog walking–related skin trauma; the great majority of patients with cutaneous injury, as illustrated here, likely never present to the ED, unlike patients with bone fracture. Moreover, data do not capture cases handled by providers outside the ED and self-treated injuries.

In the absence of accurate estimates of cutaneous morbidity related to dog-walking injury, the case reports here are clearly a cautionary tale. Physicians and older adults need to be cognizant of the hazards of this activity. Providers should discuss with older patients the potential risks of dog walking before recommending or condoning this exercise.

The presence of other comorbidities that could hamper a person’s ability to control a leashed dog warrants special consideration. Older prospective dog owners might consider adopting a small, easily manageable breed. These measures can help protect older adults’ fragile skin (and bones) from avoidable minor to potentially life-threatening trauma.

- Christian H, Bauman A, Epping JN, et al. Encouraging dog walking for health promotion and disease prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;12:233-243.

- Curl AL, Bibbo J, Johnson RA. Dog walking, the human–animal bond and older adults’ physical health. Gerontologist. 2017;57:930-939.

- Dunkin MA. Walking strategies. Arthritis Foundation website. https://arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/physical-activity/walking/5-walking-strategies. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Pirruccio K, Yoon YM, Ahn J. Fractures in elderly Americans associated with walking leashed dogs. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:458-459.

- Sprinkle D. Pet owner demographics get grayer, more golden. Petfood Industry website. https://www.petfoodindustry.com/articles/6315-pet-owner-demographics-get-grayer-more-golden?v=preview. Published March 10, 2017. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Quan T, Fisher GJ. Role of age-associated alterations of the dermal extracellular matrix microenvironment in human skin aging: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2015;61:427-434.

- Aging & painful skin. Cleveland Clinic website. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16725-aging--painful-skin. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and fall injuries among adults aged ≥65 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:993-998.

- Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75:51-61.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; . 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:E1-E76.

- Armstrong DG, Meyr AJ. Basic principles of wound management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/basic-principles-of-wound-management. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Trott AT. Wounds and Lacerations: Emergency Care and Closure. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Head injuries in adults: what is it? Harvard Health Publishing website. www.health.harvard.edu/a_to_z/head-injury-in-adults-a-to-z. Published October 2018. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- McBride W. Intracranial epidural hematoma in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intracranial-epidural-hematoma-in-adults. Updated July 23, 2018. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- McBride W. Subdural hematoma in adults: prognosis and management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/subdural-hematoma-in-adults-prognosis-and-management. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Schroeder T, Ault K. The NEISS sample: design and implementation. Washington, DC: US Consumer Product Safety Commission, Division of Hazard and Injury Data Systems; June 2001. https://cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_2001d011-6b6.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS). Bethesda, MD: US Consumer Product Safety Commission; 2018. https://www.cpsc.gov/Research--Statistics/NEISS-Injury-Data. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Christian H, Bauman A, Epping JN, et al. Encouraging dog walking for health promotion and disease prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;12:233-243.

- Curl AL, Bibbo J, Johnson RA. Dog walking, the human–animal bond and older adults’ physical health. Gerontologist. 2017;57:930-939.

- Dunkin MA. Walking strategies. Arthritis Foundation website. https://arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/physical-activity/walking/5-walking-strategies. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Pirruccio K, Yoon YM, Ahn J. Fractures in elderly Americans associated with walking leashed dogs. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:458-459.

- Sprinkle D. Pet owner demographics get grayer, more golden. Petfood Industry website. https://www.petfoodindustry.com/articles/6315-pet-owner-demographics-get-grayer-more-golden?v=preview. Published March 10, 2017. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Quan T, Fisher GJ. Role of age-associated alterations of the dermal extracellular matrix microenvironment in human skin aging: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2015;61:427-434.

- Aging & painful skin. Cleveland Clinic website. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16725-aging--painful-skin. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and fall injuries among adults aged ≥65 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:993-998.

- Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75:51-61.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; . 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:E1-E76.

- Armstrong DG, Meyr AJ. Basic principles of wound management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/basic-principles-of-wound-management. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Trott AT. Wounds and Lacerations: Emergency Care and Closure. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Head injuries in adults: what is it? Harvard Health Publishing website. www.health.harvard.edu/a_to_z/head-injury-in-adults-a-to-z. Published October 2018. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- McBride W. Intracranial epidural hematoma in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intracranial-epidural-hematoma-in-adults. Updated July 23, 2018. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- McBride W. Subdural hematoma in adults: prognosis and management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/subdural-hematoma-in-adults-prognosis-and-management. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Schroeder T, Ault K. The NEISS sample: design and implementation. Washington, DC: US Consumer Product Safety Commission, Division of Hazard and Injury Data Systems; June 2001. https://cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_2001d011-6b6.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS). Bethesda, MD: US Consumer Product Safety Commission; 2018. https://www.cpsc.gov/Research--Statistics/NEISS-Injury-Data. Accessed March 16, 2020.

Practice Points

- Dog walking is a good source of exercise but can lead to serious skin/soft tissue injury.

- When evaluating cutaneous trauma related to dog walking, remember to consider the possibility of an underlying bone fracture.

- Cutaneous trauma may overlay serious internal injury, such as epidural or subdural hematoma.

The Syphilis Epidemic: Dermatologists on the Frontline of Treatment and Diagnosis

Ulcerative Sarcoidosis: A Prototypical Presentation and Review

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology that primarily affects the lungs and lymphatic system but also may involve the skin, eyes, liver, spleen, muscles, bones, and nervous system.1 Cutaneous symptoms of sarcoidosis occur in approximately 25% of patients and are classified as specific and nonspecific, with specific lesions demonstrating noncaseating granuloma formation, which is typical of sarcoidosis.2 Nonspecific lesions primarily include erythema nodosum and calcinosis cutis. Specific lesions commonly present as reddish brown infiltrated plaques that may be annular, polycyclic, or serpiginous.1,3 They also may appear as yellowish brown or violaceous maculopapular lesions. However, specific lesions may present in a wide variety of morphologies, most often papules, nodules, subcutaneous infiltrates, and lupus pernio.4 Additionally, atypical cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis include erythroderma; scarring alopecia; nail dystrophy; and verrucous, ichthyosiform, psoriasiform, hypopigmented, or ulcerative skin lesions.3-5 Among these many potential clinical presentations, ulcerative sarcoidosis is quite uncommon.

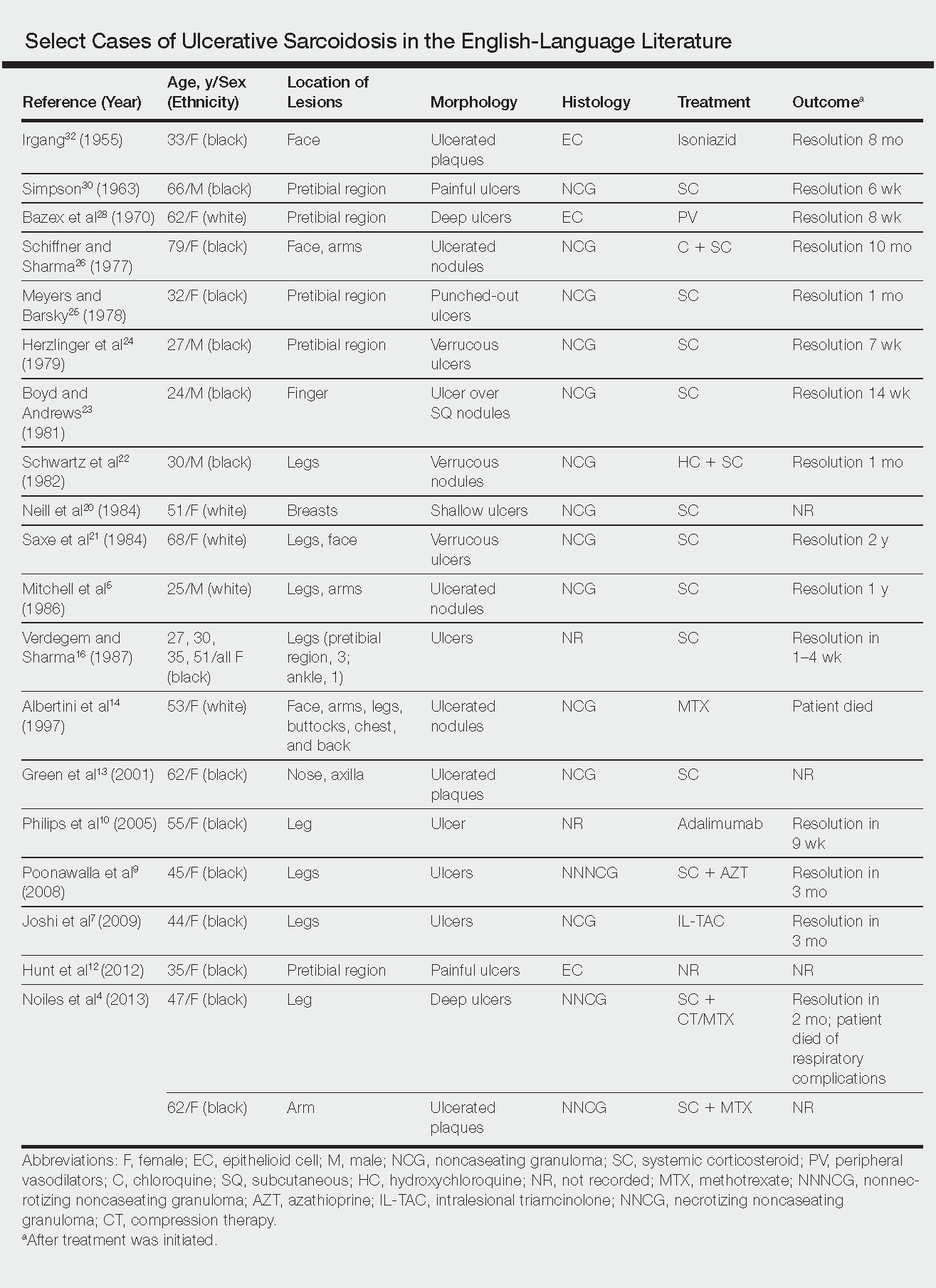

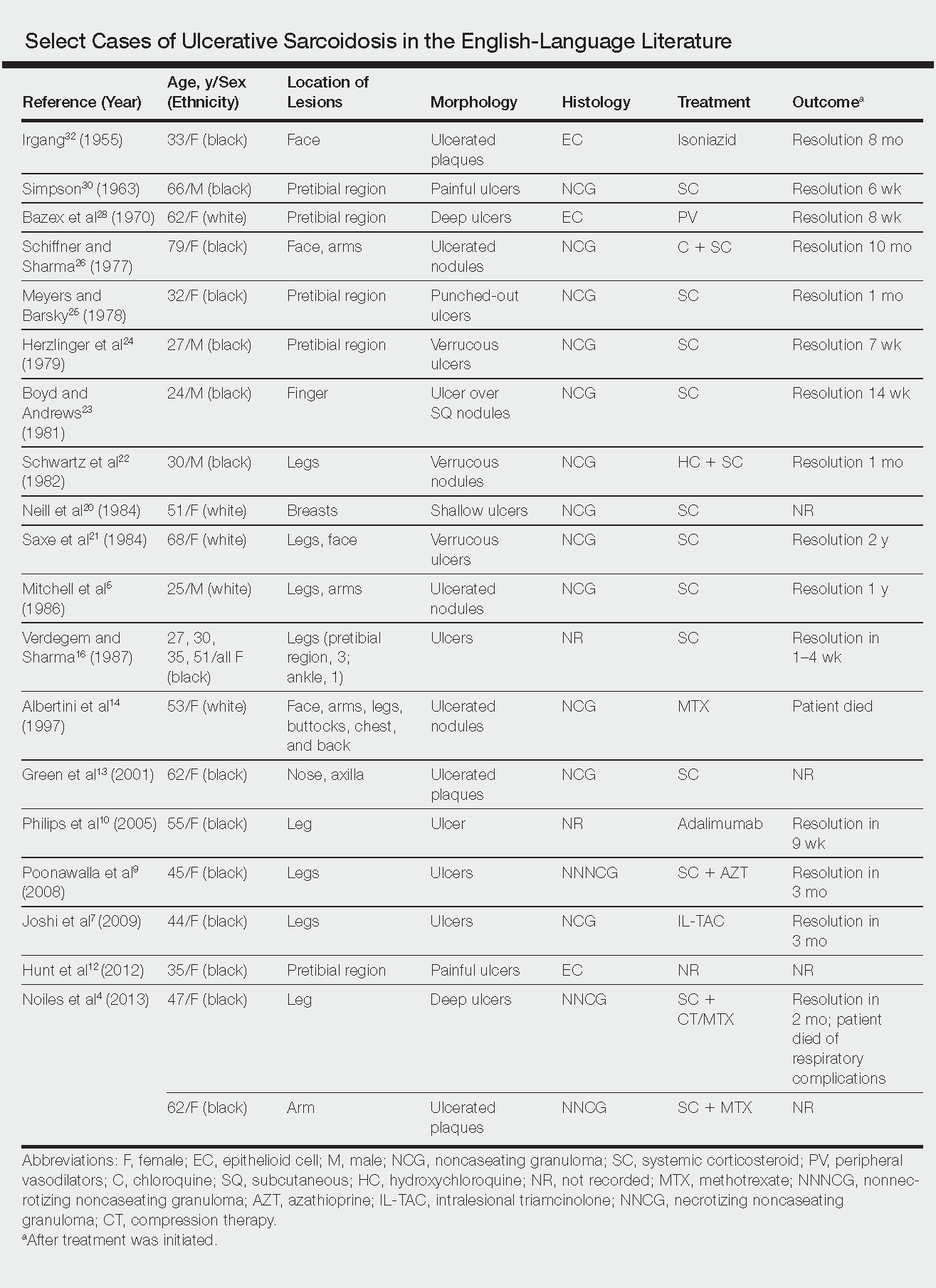

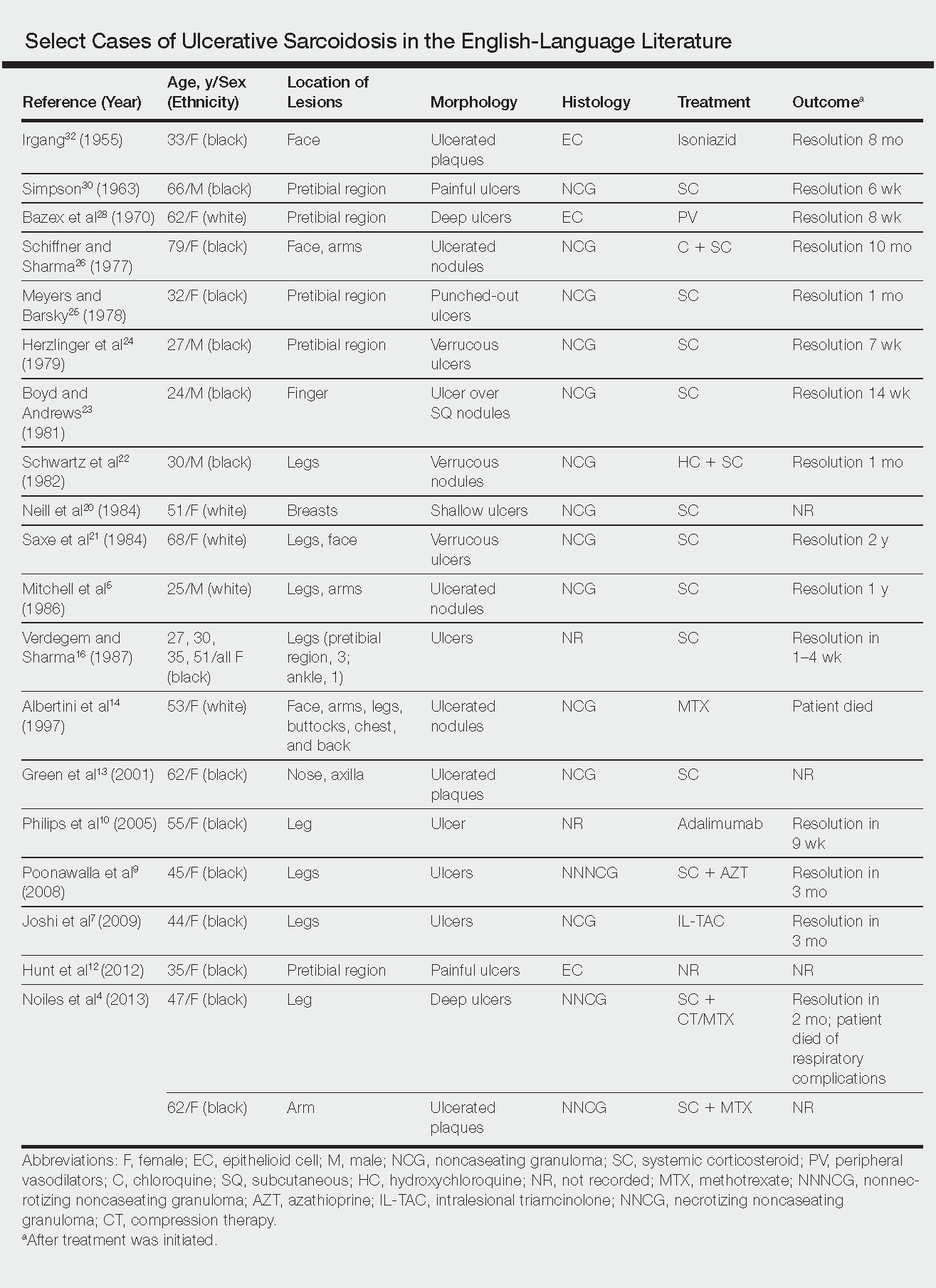

We report a case of a patient who presented with classic clinical and histopathological findings of ulcerative sarcoidosis to highlight the prototypical presentation of a rare condition. We also review 34 additional cases of ulcerative sarcoidosis published in the English-language literature based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term ulcerative sarcoid.4-32 Analyzing this historical information, the scope of this unusual form of cutaneous sarcoidosis can be better understood, recognized, and treated. Although current standard-of-care treatments are most often successful, there is a paucity of definitive clinical trials to justify and verify comparative therapeutic efficacy.

Case Report

A 49-year-old black man with known pulmonary sarcoidosis, idiopathic (human immunodeficiency virus–negative) CD4 depletion syndrome, and chronic kidney disease presented with persistent bilateral ulcers of the legs of 1 month’s duration. The lesions first appeared as multiple “dark spots” on the legs. After the patient applied homemade aloe vera extract under occlusion for 1 to 2 days, the lesions became painful and began to ulcerate approximately 3 months prior to presentation. The patient applied a combination of a topical first aid antibiotic ointment, Epsom salts, and hydrogen peroxide without any improvement. A current review of systems was negative.

The patient’s medical history was notable for sarcoidosis diagnosed more than 10 years prior. During this time, he had intermittently been treated elsewhere with low-dose oral prednisone (5 mg once daily), hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily), and an inhaled steroid as needed. He had a history of human immunodeficiency virus–negative, idiopathic CD4 depletion syndrome, which had been complicated by cryptococcal meningitis 7 years prior to presentation. He also had renal insufficiency, with baseline creatinine levels ranging from 1.4 to 1.7 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL). There was no personal or family history of known or suspected inflammatory bowel disease.

On physical examination, numerous discrete, coalescing, punched out–appearing ulcerations with foul-smelling, greenish yellow, purulent drainage were present bilaterally on the legs (Figure 1). The ulcers had a rolled border with a moderate amount of seemingly nonviable necrotic tissue. A number of hyperpigmented round papules, patches, and plaques also were present on the proximal legs. Laboratory evaluation revealed a CD4 count of 151 cc/mm3 (reference range, 500–1600 cc/mm3) and mildly elevated calcium of 10.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL).

Aerobic, anaerobic, mycobacterial, and fungal cultures of the purulent exudate were obtained. Given a high suspicion for secondary infection of the exogenous wound sites, doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) and topical mupir-ocin were initiated. Gram stain revealed few to moderate polymorphonuclear cells and many gram-positive cocci in pairs, chains, and clusters, along with many gram-negative rods. Bacterial culture grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus species group G streptococci, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus–positive staphylococci. Ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) was then initiated, but the ulcers showed absolutely no clinical improvement and in fact worsened both in number and depth (Figure 2) over subsequent clinic visits during the next 3 months, even after amoxicillin (500 mg 3 times daily) was added. The patient was admitted for treatment with intravenous antibiotics after additional wound cultures revealed fluoroquinolone-resistant Pseudomonas.

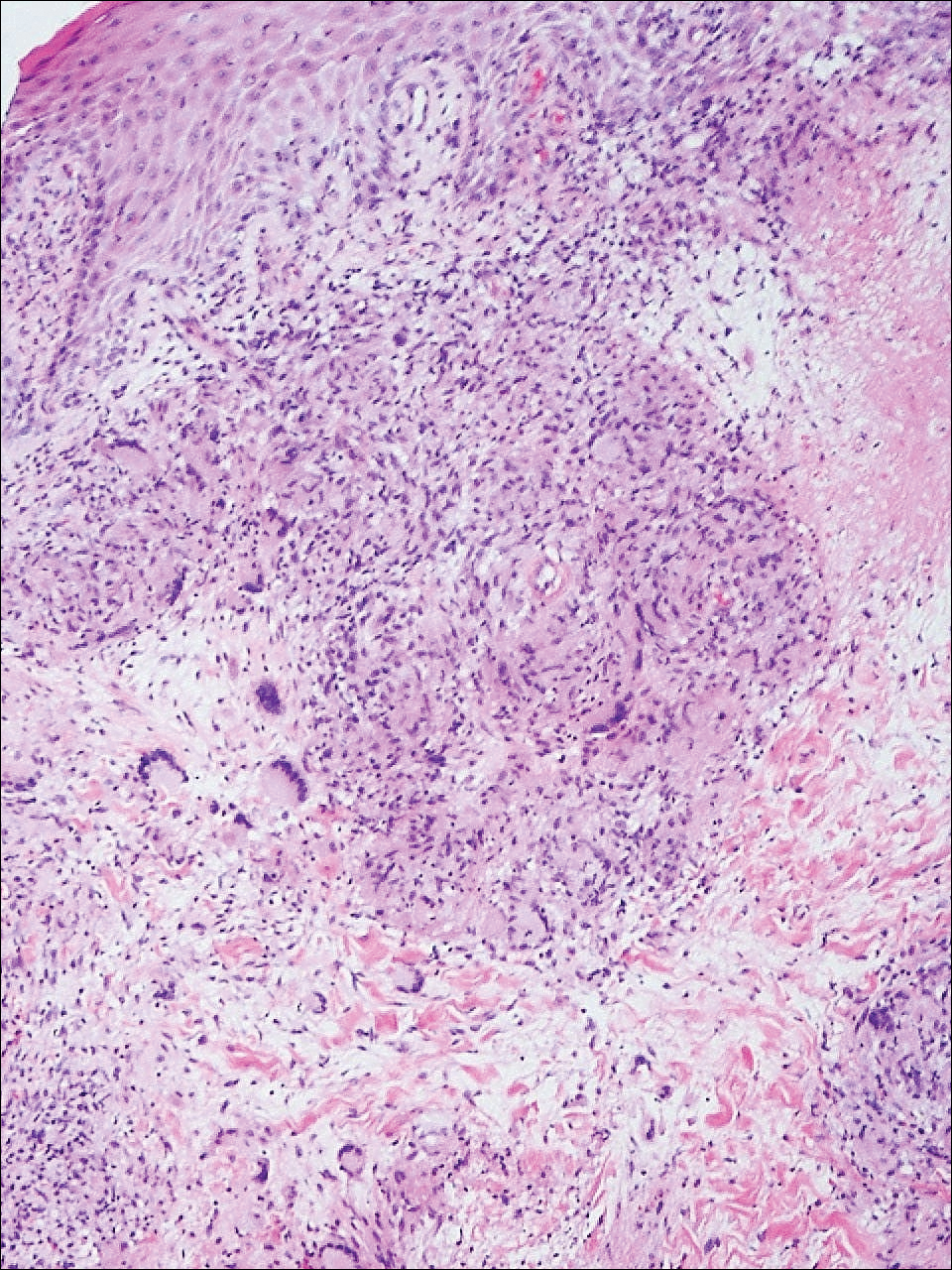

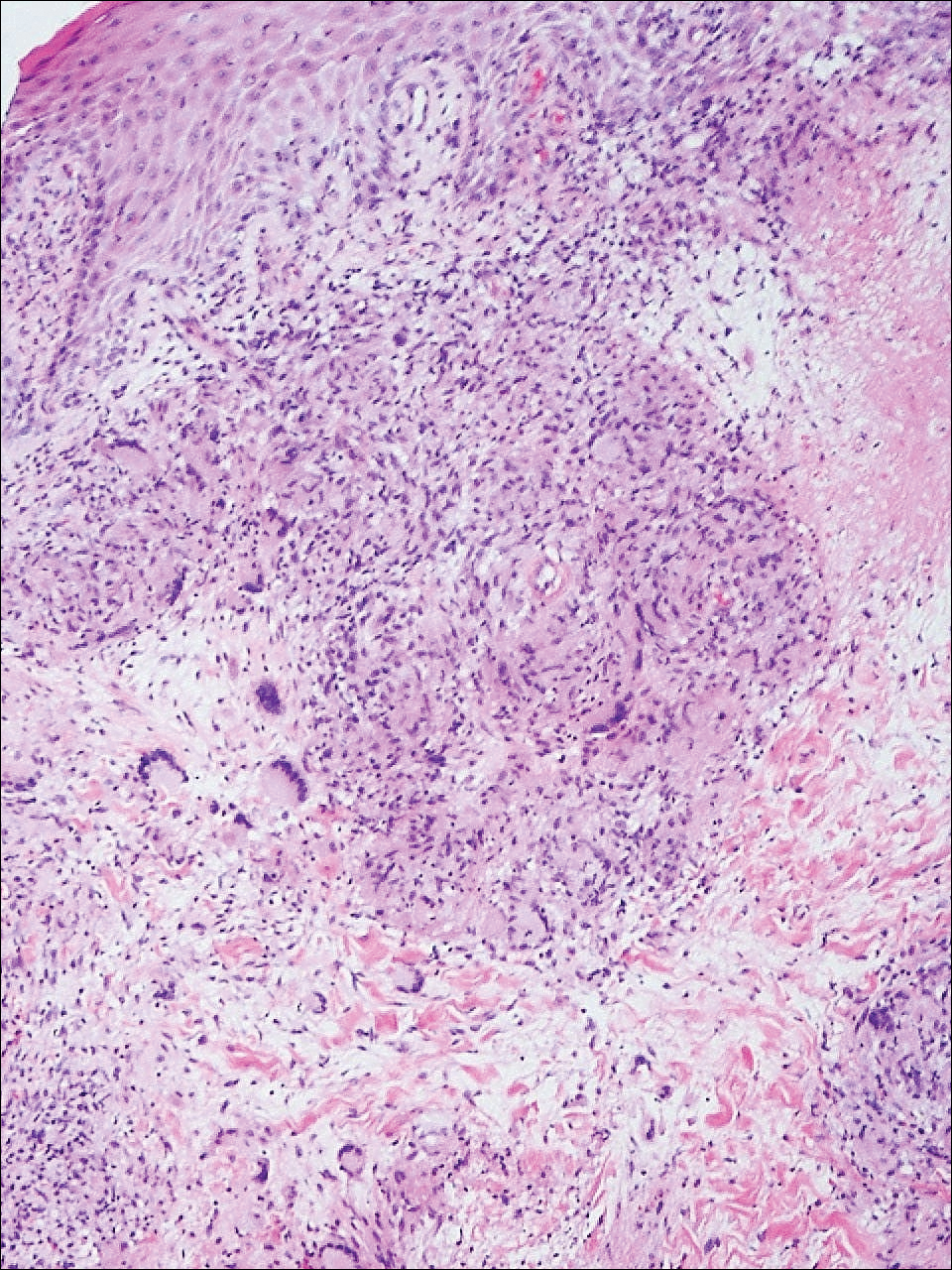

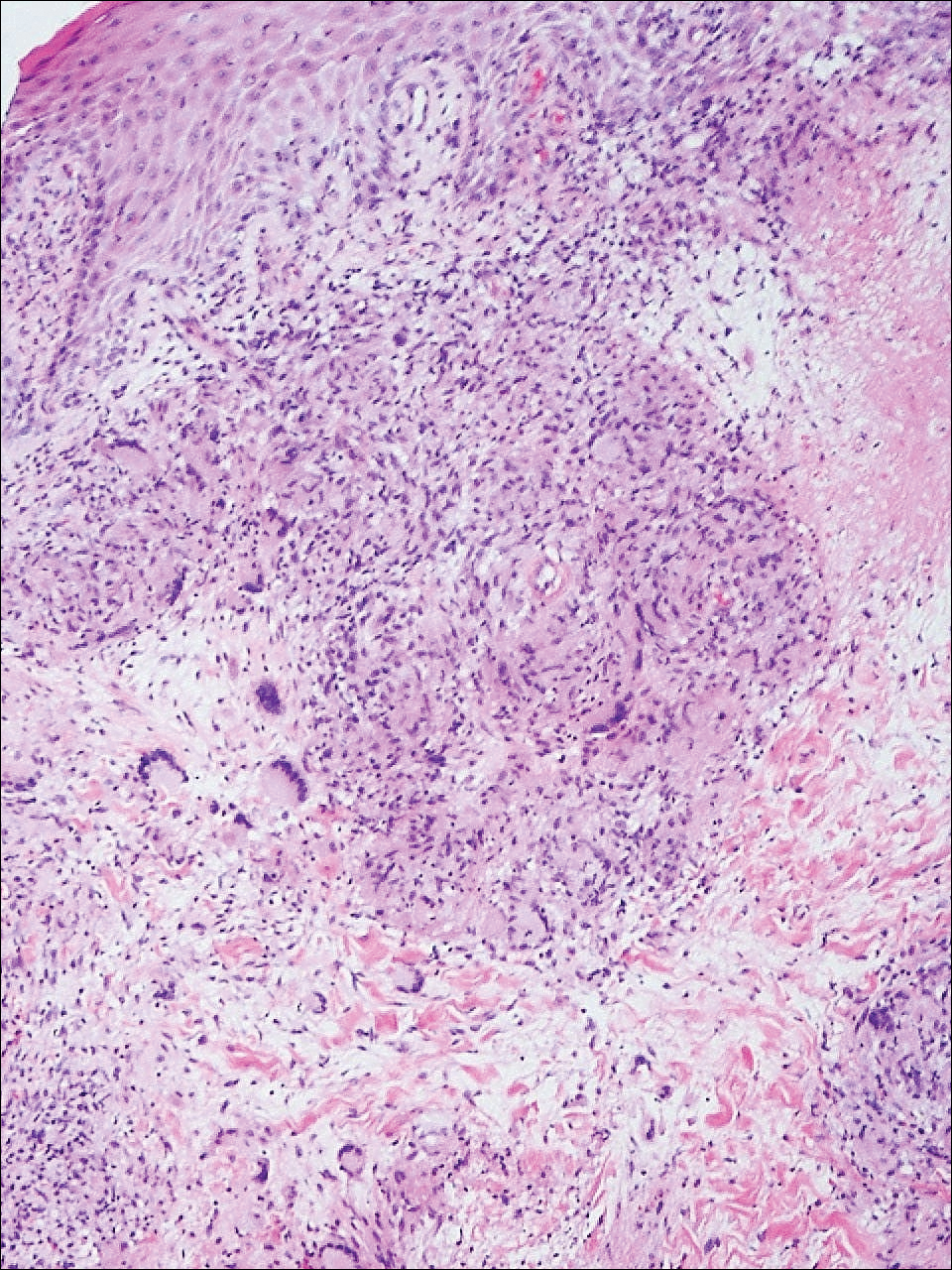

Punch biopsies of the ulcers showed nonspecific acute inflammation and tissue necrosis in the active ulcers with nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammation extending into the deep dermis, with many Langerhans-type giant cells present in the palpable ulcer borders (Figure 3). Neither birefringent particles nor asteroid bodies were observed. Tissue Gram stains did not reveal evidence of bacterial infection. Special stains for acid-fast and fungal organisms (ie, periodic acid–Schiff, Gomori methenamine-silver, Fite, acid-fast bacilli) were similarly negative. Tissue cultures obtained on deep biopsy revealed only rare colonies of P aeruginosa and no isolates on anaerobic, mycobacterial, or fungal cultures. Polymerase chain reaction for mycobacteria and common endemic fungi also was negative. In the absence of infection and considering his history of known sarcoidosis, these histologic features were consistent with ulcerative sarcoidosis. The patient was started on prednisone (60 mg once daily) and hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily). The prednisone was tapered to 20 mg once daily over a 2-year period, at which point 90% of the ulcers had healed. He was continued on hydroxychloroquine at the initial dose, and at a 3-year follow-up his ulcers had healed completely without relapse.

Comment