User login

This discussion was recorded on Feb. 21, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Welcome, Dr. Salazar. It’s a pleasure to have you join us today.

Gilberto A. Salazar, MD: The pleasure is all mine, Dr. Glatter. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter: This is such an important topic, as you can imagine. Workplace violence is affecting so many providers in hospital emergency departments but also throughout other parts of the hospital.

First, can you describe how the virtual reality (VR) program was designed that you developed and what type of situations it simulates?

Dr. Salazar: We worked in conjunction with the University of Texas at Dallas. They help people like me, subject matter experts in health care, to bring ideas to reality. I worked very closely with a group of engineers from their department in designing a module specifically designed to tackle, as you mentioned, one of our biggest threats in workplace violence.

We decided to bring in a series of competencies and proficiencies that we wanted to bring into the virtual reality space. In leveraging the technology and the expertise from UT Dallas, we were able to make that happen.

Dr. Glatter: I think it’s important to understand, in terms of virtual reality, what type of environment the program creates. Can you describe what a provider who puts the goggles on is experiencing? Do they feel anything? Is there technology that enables this?

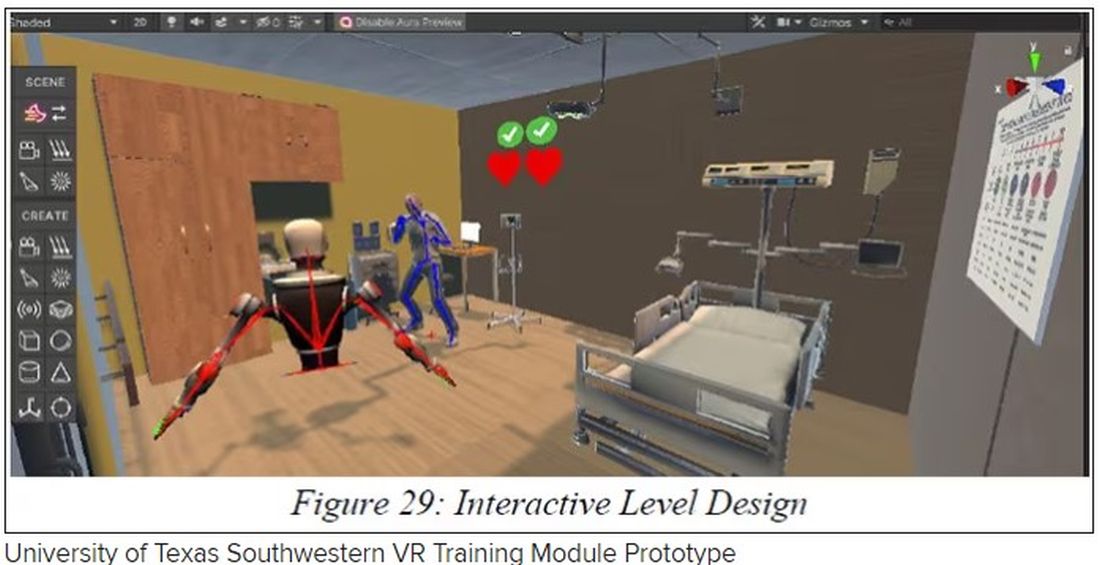

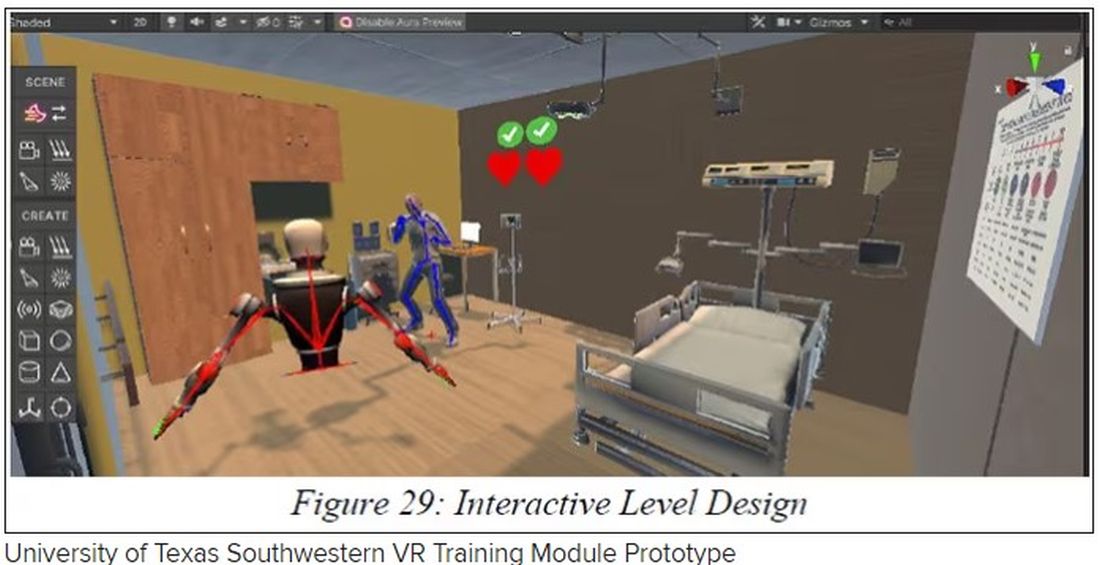

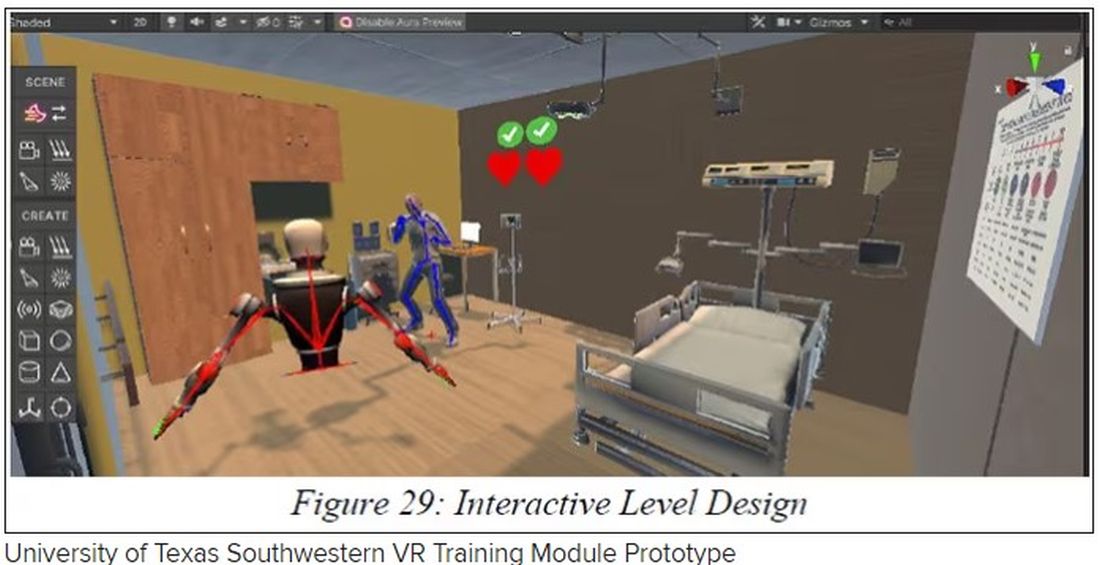

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We were able to bring to reality a series of scenarios very common from what you and I see in the emergency department on a daily basis. We wanted to immerse a learner into that specific environment. We didn’t feel that a module or something on a computer or a slide set could really bring the reality of what it’s like to interact with a patient who may be escalating or may be aggressive.

We are immersing learners into an actual hospital room to our specifications, very similar to exactly where we practice each and every day, and taking the learners through different situations that we designed with various levels of escalation and aggression, and asking the learner to manage that situation as best as they possibly can using the competencies and proficiencies that we taught them.

Dr. Glatter: Haptic feedback is an important part of the program and also the approach and technique that you’re using. Can you describe what haptic feedback means and what people actually feel?

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. One of the most unfortunate things in my professional career is physical abuse suffered by people like me and you and our colleagues, nursing personnel, technicians, and others, resulting in injury.

We wanted to provide the most realistic experience that we could design. Haptics engage digital senses other than your auditory and your visuals. They really engage your tactile senses. These haptic vests and gloves and technology allow us to provide a third set of sensory stimuli for the learner.

At one of the modules, we have an actual physical assault that takes place, and the learner is actually able to feel in their body the strikes – of course, not painful – but just bringing in those senses and that stimulus, really leaving the learner with an experience that’s going to be long-lasting.

Dr. Glatter: Feeling that stimulus certainly affects your vital signs. Do you monitor a provider’s vital signs, such as their blood pressure and heart rate, as the situation and the threat escalate? That could potentially trigger some issues in people with prior PTSD or people with other mental health issues. Has that ever been considered in the design of your program?

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. The beautiful thing about haptics is that they can be tailored to our specific parameters. The sensory stimulus that’s provided is actually very mild. It feels more like a tap than an actual strike. It just reminds us that when we’re having or experiencing an actual physical attack, we’re really engaging the senses.

We have an emergency physician or an EMT-paramedic on site at all times during the training so that we can monitor our subjects and make sure that they’re comfortable and healthy.

Dr. Glatter: Do they have actual sensors attached to their bodies that are part of your program or distinct in terms of monitoring their vital signs?

Dr. Salazar: It’s completely different. We have two different systems that we are planning on utilizing. Frankly, in the final version of this virtual reality module, we may not even involve the haptics. We’re going to study it and see how our learners behave and how much information they’re able to acquire and retain.

It may be very possible that just the visuals – the auditory and the immersion taking place within the hospital room – may be enough. It’s very possible that, in the next final version of this, we may find that haptics bring in quite a bit of value, and we may incorporate that. If that is the case, then we will, of course, acquire different technology to monitor the patient’s vital signs.

Dr. Glatter: Clearly, when situations escalate in the department, everyone gets more concerned about the patient, but providers are part of this equation, as you allude to.

In 2022, there was a poll by the American College of Emergency Physicians that stated that 85% of emergency physicians reported an increase in violent activity in their ERs in the past 5 years. Nearly two-thirds of nearly 3,000 emergency physicians surveyed reported being assaulted in the past year. This is an important module that we integrate into training providers in terms of these types of tense situations that can result not only in mental anguish but also in physical injury.

Dr. Salazar: One hundred percent. I frankly got tired of seeing my friends and my colleagues suffer both the physical and mental effects of verbal and physical abuse, and I wanted to design a project that was very patient centric while allowing our personnel to really manage these situations a little bit better.

Frankly, we don’t receive great training in this space, and I wanted to rewrite that narrative and make things better for our clinicians out there while remaining patient centric. I wanted to do something about it, and hopefully this dream will become a reality.

Dr. Glatter: Absolutely. There are other data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics stating that health care workers are five times more likely than employees in any other area of work to experience workplace violence. This could, again, range from verbal to physical violence. This is a very important module that you’re developing.

Are there any thoughts to extend this to active-shooter scenarios or any other high-stakes scenarios that you can imagine in the department?

Dr. Salazar: We’re actually working with the same developer that’s helping us with this VR module in developing a mass-casualty incident module so that we can get better training in responding to these very unfortunate high-stakes situations.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of using the module remotely, certainly not requiring resources or having to be in a physical place, can providers in your plan be able to take such a headset home and practice on their own in the sense of being able to deal with a situation? Would this be more reserved for in-department use?

Dr. Salazar: That’s a phenomenal question. I wanted to create the most flexible module that I possibly could. Ideally, a dream scenario is leveraging a simulation center at an academic center and not just do the VR module but also have a brief didactics incorporating a small slide set, some feedback, and some standardized patients. I wanted it to be flexible enough so that folks here in my state, a different state, or even internationally could take advantage of this technology and do it from the comfort of their home.

As you mentioned, this is going to strike some people. It’s going to hit them heavier than others in terms of prior experience as PTSD. For some people, it may be more comfortable to do it in the comfort of their homes. I wanted to create something very flexible and dynamic.

Dr. Glatter: I think that’s ideal. Just one other point. Can you discuss the different levels of competencies involved in this module and how that would be attained?

Dr. Salazar: It’s all evidence based, so we borrowed from literature and the specialties of emergency medicine. We collaborated with psychiatrists within our medical center. We looked at all available literature and methods, proficiencies, competencies, and best practices, and we took all of them together to form something that we think is organized and concise.

We were able to create our own algorithm, but it’s not brand new. We’re just borrowing what we think is the best to create something that the majority of health care personnel are going to be able to relate to and be able to really be proficient at.

This includes things like active listening, bargaining, how to respond, where to put yourself in a situation, and the best possible situation to respond to a scenario, how to prevent things – how to get out of a chokehold, for example. We’re borrowing from several different disciplines and creating something that can be very concise and organized.

Dr. Glatter: Does this program that you’ve developed allow the provider to get feedback in the sense that when they’re in such a danger, their life could be at risk? For example, if they don’t remove themselves in a certain amount of time, this could be lethal.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. Probably the one thing that differentiates our project from any others is the ability to customize the experience so that a learner who is doing the things that we ask them to do in terms of safety and response is able to get out of a situation successfully within the environment. If they don’t, they get some kind of feedback.

Not to spoil the surprise here, but we’re going to be doing things like looking at decibel meters to see what the volume in the room is doing and how you’re managing the volume and the stimulation within the room. If you are able to maintain the decibel readings at a specific level, you’re going to succeed through the module. If you don’t, we keep the patient escalation going.

Dr. Glatter: There is a debrief built into this type of approach where, in other words, learning points are emphasized – where you could have done better and such.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We are going to be able to get individualized data for each learner so that we can tailor the debrief to their own performance and be able to give them actionable items to work on. It’s a debrief that’s productive and individualized, and folks can walk away with something useful in the end.

Dr. Glatter: Are the data shared or confidential at present?

Dr. Salazar: At this very moment, the data are confidential. We are going to look at how to best use this. We’re hoping to eventually write this up and see how this information can be best used to train personnel.

Eventually, we may see that some of the advice that we’re giving is very common to most folks. Others may require some individualized type of feedback. That said, it remains to be seen, but right now, it’s confidential.

Dr. Glatter: Is this currently being implemented as part of your curriculum for emergency medicine residents?

Dr. Salazar: We’re going to study it first. We’re very excited to include our emergency medicine residents as one of our cohorts that’s going to be undergoing the module, and we’re going to be studying other forms of workplace violence mitigation strategies. We’re really excited about the possibility of this eventually becoming the standard of education for not only our emergency medicine residents, but also health care personnel all over the world.

Dr. Glatter: I’m glad you mentioned that, because obviously nurses, clerks in the department, and anyone who’s working in the department, for that matter, and who interfaces with patients really should undergo such training.

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. The folks at intake, at check-in, and at kiosks. Do they go through a separate area for screening? You’re absolutely right. There are many folks who interface with patients and all of us are potential victims of workplace violence. We want to give our health care family the best opportunity to succeed in these situations.

Dr. Glatter:: Absolutely. Even EMS providers, being on the front lines and encountering patients in such situations, would benefit, in my opinion.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. Behavioral health emergencies and organically induced altered mental status results in injury, both physical and mental, to EMS professionals as well, and there’s good evidence of that. I’ll be very glad to see this type of education make it out to our initial and continuing education efforts for EMS as well.

Dr. Glatter: I want to thank you. This has been very helpful. It’s such an important task that you’ve started to explore, and I look forward to follow-up on this. Again, thank you for your time.

Dr. Salazar: It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y. He is an editorial adviser and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series on Medscape. He is also a medical contributor for Forbes. Dr. Salazar is a board-certified emergency physician and associate professor at UT Southwestern Medicine Center in Dallas. He is involved with the UTSW Emergency Medicine Education Program and serves as the medical director to teach both initial and continuing the emergency medicine education for emergency medical technicians and paramedics, which trains most of the Dallas Fire Rescue personnel and the vast majority for EMS providers in the Dallas County. In addition, he serves as an associate chief of service at Parkland’s emergency department, and liaison to surgical services. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This discussion was recorded on Feb. 21, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Welcome, Dr. Salazar. It’s a pleasure to have you join us today.

Gilberto A. Salazar, MD: The pleasure is all mine, Dr. Glatter. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter: This is such an important topic, as you can imagine. Workplace violence is affecting so many providers in hospital emergency departments but also throughout other parts of the hospital.

First, can you describe how the virtual reality (VR) program was designed that you developed and what type of situations it simulates?

Dr. Salazar: We worked in conjunction with the University of Texas at Dallas. They help people like me, subject matter experts in health care, to bring ideas to reality. I worked very closely with a group of engineers from their department in designing a module specifically designed to tackle, as you mentioned, one of our biggest threats in workplace violence.

We decided to bring in a series of competencies and proficiencies that we wanted to bring into the virtual reality space. In leveraging the technology and the expertise from UT Dallas, we were able to make that happen.

Dr. Glatter: I think it’s important to understand, in terms of virtual reality, what type of environment the program creates. Can you describe what a provider who puts the goggles on is experiencing? Do they feel anything? Is there technology that enables this?

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We were able to bring to reality a series of scenarios very common from what you and I see in the emergency department on a daily basis. We wanted to immerse a learner into that specific environment. We didn’t feel that a module or something on a computer or a slide set could really bring the reality of what it’s like to interact with a patient who may be escalating or may be aggressive.

We are immersing learners into an actual hospital room to our specifications, very similar to exactly where we practice each and every day, and taking the learners through different situations that we designed with various levels of escalation and aggression, and asking the learner to manage that situation as best as they possibly can using the competencies and proficiencies that we taught them.

Dr. Glatter: Haptic feedback is an important part of the program and also the approach and technique that you’re using. Can you describe what haptic feedback means and what people actually feel?

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. One of the most unfortunate things in my professional career is physical abuse suffered by people like me and you and our colleagues, nursing personnel, technicians, and others, resulting in injury.

We wanted to provide the most realistic experience that we could design. Haptics engage digital senses other than your auditory and your visuals. They really engage your tactile senses. These haptic vests and gloves and technology allow us to provide a third set of sensory stimuli for the learner.

At one of the modules, we have an actual physical assault that takes place, and the learner is actually able to feel in their body the strikes – of course, not painful – but just bringing in those senses and that stimulus, really leaving the learner with an experience that’s going to be long-lasting.

Dr. Glatter: Feeling that stimulus certainly affects your vital signs. Do you monitor a provider’s vital signs, such as their blood pressure and heart rate, as the situation and the threat escalate? That could potentially trigger some issues in people with prior PTSD or people with other mental health issues. Has that ever been considered in the design of your program?

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. The beautiful thing about haptics is that they can be tailored to our specific parameters. The sensory stimulus that’s provided is actually very mild. It feels more like a tap than an actual strike. It just reminds us that when we’re having or experiencing an actual physical attack, we’re really engaging the senses.

We have an emergency physician or an EMT-paramedic on site at all times during the training so that we can monitor our subjects and make sure that they’re comfortable and healthy.

Dr. Glatter: Do they have actual sensors attached to their bodies that are part of your program or distinct in terms of monitoring their vital signs?

Dr. Salazar: It’s completely different. We have two different systems that we are planning on utilizing. Frankly, in the final version of this virtual reality module, we may not even involve the haptics. We’re going to study it and see how our learners behave and how much information they’re able to acquire and retain.

It may be very possible that just the visuals – the auditory and the immersion taking place within the hospital room – may be enough. It’s very possible that, in the next final version of this, we may find that haptics bring in quite a bit of value, and we may incorporate that. If that is the case, then we will, of course, acquire different technology to monitor the patient’s vital signs.

Dr. Glatter: Clearly, when situations escalate in the department, everyone gets more concerned about the patient, but providers are part of this equation, as you allude to.

In 2022, there was a poll by the American College of Emergency Physicians that stated that 85% of emergency physicians reported an increase in violent activity in their ERs in the past 5 years. Nearly two-thirds of nearly 3,000 emergency physicians surveyed reported being assaulted in the past year. This is an important module that we integrate into training providers in terms of these types of tense situations that can result not only in mental anguish but also in physical injury.

Dr. Salazar: One hundred percent. I frankly got tired of seeing my friends and my colleagues suffer both the physical and mental effects of verbal and physical abuse, and I wanted to design a project that was very patient centric while allowing our personnel to really manage these situations a little bit better.

Frankly, we don’t receive great training in this space, and I wanted to rewrite that narrative and make things better for our clinicians out there while remaining patient centric. I wanted to do something about it, and hopefully this dream will become a reality.

Dr. Glatter: Absolutely. There are other data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics stating that health care workers are five times more likely than employees in any other area of work to experience workplace violence. This could, again, range from verbal to physical violence. This is a very important module that you’re developing.

Are there any thoughts to extend this to active-shooter scenarios or any other high-stakes scenarios that you can imagine in the department?

Dr. Salazar: We’re actually working with the same developer that’s helping us with this VR module in developing a mass-casualty incident module so that we can get better training in responding to these very unfortunate high-stakes situations.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of using the module remotely, certainly not requiring resources or having to be in a physical place, can providers in your plan be able to take such a headset home and practice on their own in the sense of being able to deal with a situation? Would this be more reserved for in-department use?

Dr. Salazar: That’s a phenomenal question. I wanted to create the most flexible module that I possibly could. Ideally, a dream scenario is leveraging a simulation center at an academic center and not just do the VR module but also have a brief didactics incorporating a small slide set, some feedback, and some standardized patients. I wanted it to be flexible enough so that folks here in my state, a different state, or even internationally could take advantage of this technology and do it from the comfort of their home.

As you mentioned, this is going to strike some people. It’s going to hit them heavier than others in terms of prior experience as PTSD. For some people, it may be more comfortable to do it in the comfort of their homes. I wanted to create something very flexible and dynamic.

Dr. Glatter: I think that’s ideal. Just one other point. Can you discuss the different levels of competencies involved in this module and how that would be attained?

Dr. Salazar: It’s all evidence based, so we borrowed from literature and the specialties of emergency medicine. We collaborated with psychiatrists within our medical center. We looked at all available literature and methods, proficiencies, competencies, and best practices, and we took all of them together to form something that we think is organized and concise.

We were able to create our own algorithm, but it’s not brand new. We’re just borrowing what we think is the best to create something that the majority of health care personnel are going to be able to relate to and be able to really be proficient at.

This includes things like active listening, bargaining, how to respond, where to put yourself in a situation, and the best possible situation to respond to a scenario, how to prevent things – how to get out of a chokehold, for example. We’re borrowing from several different disciplines and creating something that can be very concise and organized.

Dr. Glatter: Does this program that you’ve developed allow the provider to get feedback in the sense that when they’re in such a danger, their life could be at risk? For example, if they don’t remove themselves in a certain amount of time, this could be lethal.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. Probably the one thing that differentiates our project from any others is the ability to customize the experience so that a learner who is doing the things that we ask them to do in terms of safety and response is able to get out of a situation successfully within the environment. If they don’t, they get some kind of feedback.

Not to spoil the surprise here, but we’re going to be doing things like looking at decibel meters to see what the volume in the room is doing and how you’re managing the volume and the stimulation within the room. If you are able to maintain the decibel readings at a specific level, you’re going to succeed through the module. If you don’t, we keep the patient escalation going.

Dr. Glatter: There is a debrief built into this type of approach where, in other words, learning points are emphasized – where you could have done better and such.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We are going to be able to get individualized data for each learner so that we can tailor the debrief to their own performance and be able to give them actionable items to work on. It’s a debrief that’s productive and individualized, and folks can walk away with something useful in the end.

Dr. Glatter: Are the data shared or confidential at present?

Dr. Salazar: At this very moment, the data are confidential. We are going to look at how to best use this. We’re hoping to eventually write this up and see how this information can be best used to train personnel.

Eventually, we may see that some of the advice that we’re giving is very common to most folks. Others may require some individualized type of feedback. That said, it remains to be seen, but right now, it’s confidential.

Dr. Glatter: Is this currently being implemented as part of your curriculum for emergency medicine residents?

Dr. Salazar: We’re going to study it first. We’re very excited to include our emergency medicine residents as one of our cohorts that’s going to be undergoing the module, and we’re going to be studying other forms of workplace violence mitigation strategies. We’re really excited about the possibility of this eventually becoming the standard of education for not only our emergency medicine residents, but also health care personnel all over the world.

Dr. Glatter: I’m glad you mentioned that, because obviously nurses, clerks in the department, and anyone who’s working in the department, for that matter, and who interfaces with patients really should undergo such training.

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. The folks at intake, at check-in, and at kiosks. Do they go through a separate area for screening? You’re absolutely right. There are many folks who interface with patients and all of us are potential victims of workplace violence. We want to give our health care family the best opportunity to succeed in these situations.

Dr. Glatter:: Absolutely. Even EMS providers, being on the front lines and encountering patients in such situations, would benefit, in my opinion.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. Behavioral health emergencies and organically induced altered mental status results in injury, both physical and mental, to EMS professionals as well, and there’s good evidence of that. I’ll be very glad to see this type of education make it out to our initial and continuing education efforts for EMS as well.

Dr. Glatter: I want to thank you. This has been very helpful. It’s such an important task that you’ve started to explore, and I look forward to follow-up on this. Again, thank you for your time.

Dr. Salazar: It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y. He is an editorial adviser and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series on Medscape. He is also a medical contributor for Forbes. Dr. Salazar is a board-certified emergency physician and associate professor at UT Southwestern Medicine Center in Dallas. He is involved with the UTSW Emergency Medicine Education Program and serves as the medical director to teach both initial and continuing the emergency medicine education for emergency medical technicians and paramedics, which trains most of the Dallas Fire Rescue personnel and the vast majority for EMS providers in the Dallas County. In addition, he serves as an associate chief of service at Parkland’s emergency department, and liaison to surgical services. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This discussion was recorded on Feb. 21, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Welcome, Dr. Salazar. It’s a pleasure to have you join us today.

Gilberto A. Salazar, MD: The pleasure is all mine, Dr. Glatter. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter: This is such an important topic, as you can imagine. Workplace violence is affecting so many providers in hospital emergency departments but also throughout other parts of the hospital.

First, can you describe how the virtual reality (VR) program was designed that you developed and what type of situations it simulates?

Dr. Salazar: We worked in conjunction with the University of Texas at Dallas. They help people like me, subject matter experts in health care, to bring ideas to reality. I worked very closely with a group of engineers from their department in designing a module specifically designed to tackle, as you mentioned, one of our biggest threats in workplace violence.

We decided to bring in a series of competencies and proficiencies that we wanted to bring into the virtual reality space. In leveraging the technology and the expertise from UT Dallas, we were able to make that happen.

Dr. Glatter: I think it’s important to understand, in terms of virtual reality, what type of environment the program creates. Can you describe what a provider who puts the goggles on is experiencing? Do they feel anything? Is there technology that enables this?

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We were able to bring to reality a series of scenarios very common from what you and I see in the emergency department on a daily basis. We wanted to immerse a learner into that specific environment. We didn’t feel that a module or something on a computer or a slide set could really bring the reality of what it’s like to interact with a patient who may be escalating or may be aggressive.

We are immersing learners into an actual hospital room to our specifications, very similar to exactly where we practice each and every day, and taking the learners through different situations that we designed with various levels of escalation and aggression, and asking the learner to manage that situation as best as they possibly can using the competencies and proficiencies that we taught them.

Dr. Glatter: Haptic feedback is an important part of the program and also the approach and technique that you’re using. Can you describe what haptic feedback means and what people actually feel?

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. One of the most unfortunate things in my professional career is physical abuse suffered by people like me and you and our colleagues, nursing personnel, technicians, and others, resulting in injury.

We wanted to provide the most realistic experience that we could design. Haptics engage digital senses other than your auditory and your visuals. They really engage your tactile senses. These haptic vests and gloves and technology allow us to provide a third set of sensory stimuli for the learner.

At one of the modules, we have an actual physical assault that takes place, and the learner is actually able to feel in their body the strikes – of course, not painful – but just bringing in those senses and that stimulus, really leaving the learner with an experience that’s going to be long-lasting.

Dr. Glatter: Feeling that stimulus certainly affects your vital signs. Do you monitor a provider’s vital signs, such as their blood pressure and heart rate, as the situation and the threat escalate? That could potentially trigger some issues in people with prior PTSD or people with other mental health issues. Has that ever been considered in the design of your program?

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. The beautiful thing about haptics is that they can be tailored to our specific parameters. The sensory stimulus that’s provided is actually very mild. It feels more like a tap than an actual strike. It just reminds us that when we’re having or experiencing an actual physical attack, we’re really engaging the senses.

We have an emergency physician or an EMT-paramedic on site at all times during the training so that we can monitor our subjects and make sure that they’re comfortable and healthy.

Dr. Glatter: Do they have actual sensors attached to their bodies that are part of your program or distinct in terms of monitoring their vital signs?

Dr. Salazar: It’s completely different. We have two different systems that we are planning on utilizing. Frankly, in the final version of this virtual reality module, we may not even involve the haptics. We’re going to study it and see how our learners behave and how much information they’re able to acquire and retain.

It may be very possible that just the visuals – the auditory and the immersion taking place within the hospital room – may be enough. It’s very possible that, in the next final version of this, we may find that haptics bring in quite a bit of value, and we may incorporate that. If that is the case, then we will, of course, acquire different technology to monitor the patient’s vital signs.

Dr. Glatter: Clearly, when situations escalate in the department, everyone gets more concerned about the patient, but providers are part of this equation, as you allude to.

In 2022, there was a poll by the American College of Emergency Physicians that stated that 85% of emergency physicians reported an increase in violent activity in their ERs in the past 5 years. Nearly two-thirds of nearly 3,000 emergency physicians surveyed reported being assaulted in the past year. This is an important module that we integrate into training providers in terms of these types of tense situations that can result not only in mental anguish but also in physical injury.

Dr. Salazar: One hundred percent. I frankly got tired of seeing my friends and my colleagues suffer both the physical and mental effects of verbal and physical abuse, and I wanted to design a project that was very patient centric while allowing our personnel to really manage these situations a little bit better.

Frankly, we don’t receive great training in this space, and I wanted to rewrite that narrative and make things better for our clinicians out there while remaining patient centric. I wanted to do something about it, and hopefully this dream will become a reality.

Dr. Glatter: Absolutely. There are other data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics stating that health care workers are five times more likely than employees in any other area of work to experience workplace violence. This could, again, range from verbal to physical violence. This is a very important module that you’re developing.

Are there any thoughts to extend this to active-shooter scenarios or any other high-stakes scenarios that you can imagine in the department?

Dr. Salazar: We’re actually working with the same developer that’s helping us with this VR module in developing a mass-casualty incident module so that we can get better training in responding to these very unfortunate high-stakes situations.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of using the module remotely, certainly not requiring resources or having to be in a physical place, can providers in your plan be able to take such a headset home and practice on their own in the sense of being able to deal with a situation? Would this be more reserved for in-department use?

Dr. Salazar: That’s a phenomenal question. I wanted to create the most flexible module that I possibly could. Ideally, a dream scenario is leveraging a simulation center at an academic center and not just do the VR module but also have a brief didactics incorporating a small slide set, some feedback, and some standardized patients. I wanted it to be flexible enough so that folks here in my state, a different state, or even internationally could take advantage of this technology and do it from the comfort of their home.

As you mentioned, this is going to strike some people. It’s going to hit them heavier than others in terms of prior experience as PTSD. For some people, it may be more comfortable to do it in the comfort of their homes. I wanted to create something very flexible and dynamic.

Dr. Glatter: I think that’s ideal. Just one other point. Can you discuss the different levels of competencies involved in this module and how that would be attained?

Dr. Salazar: It’s all evidence based, so we borrowed from literature and the specialties of emergency medicine. We collaborated with psychiatrists within our medical center. We looked at all available literature and methods, proficiencies, competencies, and best practices, and we took all of them together to form something that we think is organized and concise.

We were able to create our own algorithm, but it’s not brand new. We’re just borrowing what we think is the best to create something that the majority of health care personnel are going to be able to relate to and be able to really be proficient at.

This includes things like active listening, bargaining, how to respond, where to put yourself in a situation, and the best possible situation to respond to a scenario, how to prevent things – how to get out of a chokehold, for example. We’re borrowing from several different disciplines and creating something that can be very concise and organized.

Dr. Glatter: Does this program that you’ve developed allow the provider to get feedback in the sense that when they’re in such a danger, their life could be at risk? For example, if they don’t remove themselves in a certain amount of time, this could be lethal.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. Probably the one thing that differentiates our project from any others is the ability to customize the experience so that a learner who is doing the things that we ask them to do in terms of safety and response is able to get out of a situation successfully within the environment. If they don’t, they get some kind of feedback.

Not to spoil the surprise here, but we’re going to be doing things like looking at decibel meters to see what the volume in the room is doing and how you’re managing the volume and the stimulation within the room. If you are able to maintain the decibel readings at a specific level, you’re going to succeed through the module. If you don’t, we keep the patient escalation going.

Dr. Glatter: There is a debrief built into this type of approach where, in other words, learning points are emphasized – where you could have done better and such.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We are going to be able to get individualized data for each learner so that we can tailor the debrief to their own performance and be able to give them actionable items to work on. It’s a debrief that’s productive and individualized, and folks can walk away with something useful in the end.

Dr. Glatter: Are the data shared or confidential at present?

Dr. Salazar: At this very moment, the data are confidential. We are going to look at how to best use this. We’re hoping to eventually write this up and see how this information can be best used to train personnel.

Eventually, we may see that some of the advice that we’re giving is very common to most folks. Others may require some individualized type of feedback. That said, it remains to be seen, but right now, it’s confidential.

Dr. Glatter: Is this currently being implemented as part of your curriculum for emergency medicine residents?

Dr. Salazar: We’re going to study it first. We’re very excited to include our emergency medicine residents as one of our cohorts that’s going to be undergoing the module, and we’re going to be studying other forms of workplace violence mitigation strategies. We’re really excited about the possibility of this eventually becoming the standard of education for not only our emergency medicine residents, but also health care personnel all over the world.

Dr. Glatter: I’m glad you mentioned that, because obviously nurses, clerks in the department, and anyone who’s working in the department, for that matter, and who interfaces with patients really should undergo such training.

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. The folks at intake, at check-in, and at kiosks. Do they go through a separate area for screening? You’re absolutely right. There are many folks who interface with patients and all of us are potential victims of workplace violence. We want to give our health care family the best opportunity to succeed in these situations.

Dr. Glatter:: Absolutely. Even EMS providers, being on the front lines and encountering patients in such situations, would benefit, in my opinion.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. Behavioral health emergencies and organically induced altered mental status results in injury, both physical and mental, to EMS professionals as well, and there’s good evidence of that. I’ll be very glad to see this type of education make it out to our initial and continuing education efforts for EMS as well.

Dr. Glatter: I want to thank you. This has been very helpful. It’s such an important task that you’ve started to explore, and I look forward to follow-up on this. Again, thank you for your time.

Dr. Salazar: It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y. He is an editorial adviser and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series on Medscape. He is also a medical contributor for Forbes. Dr. Salazar is a board-certified emergency physician and associate professor at UT Southwestern Medicine Center in Dallas. He is involved with the UTSW Emergency Medicine Education Program and serves as the medical director to teach both initial and continuing the emergency medicine education for emergency medical technicians and paramedics, which trains most of the Dallas Fire Rescue personnel and the vast majority for EMS providers in the Dallas County. In addition, he serves as an associate chief of service at Parkland’s emergency department, and liaison to surgical services. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.