To the Editor:

Cutaneous myiasis is a skin infestation with dipterous larvae that feed on the host’s tissue and cause a wide range of manifestations depending on the location of infestation. Cutaneous myiasis, which includes furuncular, wound, and migratory types, is the most common clinical form of this condition.1 It is endemic to tropical and subtropical areas and is not common in the United States, thus it can pose a diagnostic challenge when presenting in nonendemic areas. We present the case of a woman from Michigan who acquired furuncular myiasis without travel history to a tropical or subtropical locale.

A 72-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a chief concern of a burning, pruritic, migratory skin lesion on the left arm of approximately 1 week’s duration. She had a medical history of squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, and multiple tick bites. She reported that the lesion started on the distal aspect of the left arm as an eraser-sized, perfectly round, raised bruise with a dark pepperlike bump in the center. The lesion then spread proximally over the course of 1 week, creating 3 more identical lesions. As one lesion resolved, a new lesion appeared approximately 2 to 4 cm proximal to the preceding lesion. The patient had traveled to England, Scotland, and Ireland 2 months prior but otherwise denied leaving the state of Michigan. She reported frequent exposure to gardens, meadows, and wetlands in search of milkweed and monarch butterfly larvae that she raises in northeast Michigan. She denied any recent illness or associated systemic symptoms. Initial evaluation by a primary care physician resulted in a diagnosis of a furuncle or tick bite; she completed a 10-day course of amoxicillin and a methylprednisolone dose pack without improvement.

Physical examination revealed a 1-cm, firm, violaceous nodule with a small distinct central punctum and surrounding erythema on the proximal aspect of the left arm. Dermoscopy revealed a pulsating motion and expulsion of serosanguineous fluid from the central punctum (Figure 1). Further inspection of the patient’s left arm exposed several noninflammatory puncta distal to the primary lesion spaced at 2- to 4-cm intervals.

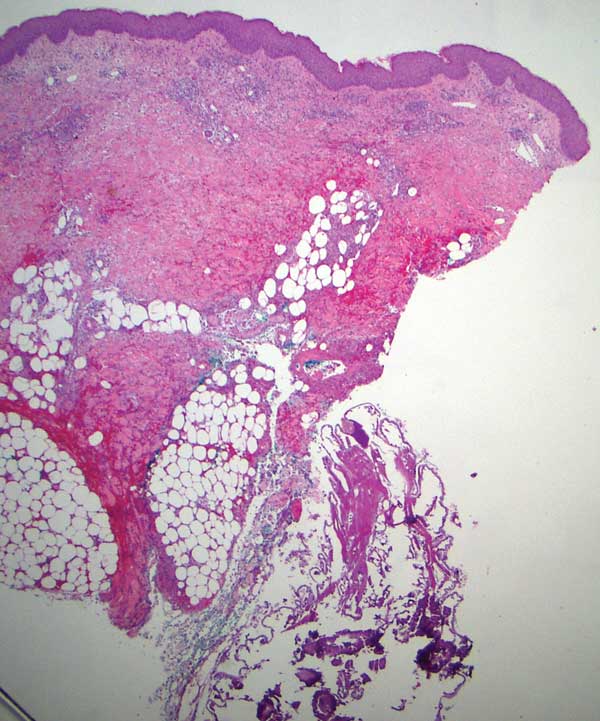

Gross examination of a 6-mm punch biopsy from the primary inflammatory nodule uncovered a small, motile, gray-white larval organism in the inferior portion of the specimen (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed superficial and deep eosinophil-rich inflammation, fibrosis, and hemorrhage. There was a complex wedge-shaped organism with extensive internal muscle bounded by a thin cuticle bearing rows of chitinous hooklets located at one side within the deep dermis (Figure 3). The findings were consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous myiasis. No further treatment was required, as the organism was completely excised with the biopsy.

The most common causative agents of furuncular myiasis obtained from travelers returning from Mexico and Central and South America are Dermatobia hominis and Cordylobia anthropophaga. Cases of furuncular myiasis acquired in the United States without recent foreign travel are rare. Most of these cases are caused by larvae of the Cuterebra species (also known as the rabbit botfly or rodent botfly).2 In a 2003 literature review by Safdar et al3 on 56 cases of furuncular myiasis in the United States, the median age of patients was 14 years, 87% of cases occurred in August and September, and most involved exposure in rural or suburban settings; 53% of cases presented in the northeastern United States.

FIGURE 3. Histopathology revealed superficial and deep eosinophilrich inflammation, fibrosis, and hemorrhage. A complex wedgeshaped organism with extensive internal skeletal muscle bounded by a thin cuticle bearing rows of chitinous hooklets was located in the deep dermis (H&E, original magnification ×40).

Furuncular myiasis occurs when the organism’s ova are deposited on the skin of a human host by the parent organism or a mosquito vector. The heat of the skin causes the eggs to hatch and the dipteran larvae must penetrate the skin within 20 days.1 Signs of infection typically are seen 6 to 10 days after infestation.3 The larvae then feed on human tissue and burrow deep in the dermis, forming an erythematous furunculoid nodule containing one or multiple maggots. After 5 to 10 weeks, the adult larvae drop to the ground, where they mature into adult organisms in the soil.1

The most reported symptoms of furuncular myiasis include pruritus, pain, and movement sensation, typically occurring suddenly at night.4 The most common presentation is a furunclelike lesion that exudes serosanguineous or purulent fluid,1 but there have been reports of vesicular, bullous, pustular, erosive, ecchymotic, and ulcerative lesions.5Dermatobia hominis usually presents on an exposed site, such as the scalp, face, and extremities. It may present with paroxysmal episodes of lancinating pain. Over time, the lesion usually heals without a scar, though hyperpigmentation and scarring can occur. The most reported complication is secondary bacterial infection.4 Local lymphadenopathy or systemic symptoms should raise concern for infection. Staphylococcus aureus and group B Streptococcus have been cultured from lesions.6,7