User login

Alzheimer's Association International Conference 2013 (AAIC)

Food for thought: DASH diet slowed cognitive decline

BOSTON – Eating well may be the best revenge against cognitive decline, a study has shown.

Among 818 dementia-free participants in a longitudinal study of memory and aging, those who adhered to the basic components of the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet had a slower rate of cognitive decline than others who followed more typical American diets, reported Martha Clare Morris, Sc.D., professor and director of the section of nutrition and nutritional epidemiology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

The relationship between diet and cognition was linear, with people who most closely followed the DASH dietary pattern having the slowest rates of decline, Dr. Morris said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

"The individual dietary components that were contributing to this slower decline were higher servings of vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes, and lower intake of total and saturated fats," she said.

The investigators chose to look at dietary patterns because they provide an index of overall dietary quality and incorporate the interactions or synergies that may occur among food groups that constitute a specific pattern.

The DASH diet has been shown to lower blood pressure, increase insulin sensitivity, and reduce weight, serum cholesterol level, inflammation, and oxidative stress.

The diet is similar to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern: heavy on fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, lean meats, fish, poultry, and low- or nonfat dairy, and light on sugar and salt.

To see whether a DASH diet pattern could have similarly beneficial effects on cognition and memory, the authors studied 818 adults who participated in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) and who agreed to fill out a 139-item food frequency questionnaire.

MAP enrolled residents from 40 retirement communities who were dementia free at enrollment and who agreed to have annual cognitive and motor tests and blood draws. Participants also agreed to donate their brains, spinal cords, muscles, and nerve tissue at death.

Participants were tested at baseline and annually with a summary measure of 19 tests assessing global cognitive function in domains of episodic, semantic, and working memory; visuospatial ability; and perceptual speed. Tests scores were standardized and averaged to come up with the composite measure.

Adherence to the DASH diet was scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 10 being a perfect score. The study participants had a mean DASH score of 4.1 (range, 1.5-8.5).

The investigators created linear mixed models incorporating global cognition, individual cognitive domains, DASH total scores, and scores for 10 dietary components. They also created a basic model adjusted for age, sex, education, and total caloric intake, with further adjustment for apolipoprotein E (apo E) status and depression.

Median DASH scores ranged from 2.5 in the lowest tertile to 4.0 in the middle to 5.5 in the highest tertile. At baseline, the mean global cognitive score was 0.14 (range, –3.24 to 1.61).

Over an average of 4.7 years of follow-up, DASH scores were significantly associated in a linear fashion (the higher the score, the slower the rate of decline) in the basic model alone and after adjustment for apo E status (P = .005) and after adjustment for both apo E and depression (P = .006).

The association was significant for all cognitive domains except visuospatial abilities, which trended toward significance but did not reach it (P = .06).

Dietary components significantly associated with slower decline include vegetables (P = .02); nuts, seeds, and legumes (P = .01); total fat (P = .05); and saturated fat (P = .01).

The Rush MAP is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Elsie Heller Brain Bank Endowment Fund, and a Rush University endowment. Dr. Morris reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Eating well may be the best revenge against cognitive decline, a study has shown.

Among 818 dementia-free participants in a longitudinal study of memory and aging, those who adhered to the basic components of the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet had a slower rate of cognitive decline than others who followed more typical American diets, reported Martha Clare Morris, Sc.D., professor and director of the section of nutrition and nutritional epidemiology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

The relationship between diet and cognition was linear, with people who most closely followed the DASH dietary pattern having the slowest rates of decline, Dr. Morris said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

"The individual dietary components that were contributing to this slower decline were higher servings of vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes, and lower intake of total and saturated fats," she said.

The investigators chose to look at dietary patterns because they provide an index of overall dietary quality and incorporate the interactions or synergies that may occur among food groups that constitute a specific pattern.

The DASH diet has been shown to lower blood pressure, increase insulin sensitivity, and reduce weight, serum cholesterol level, inflammation, and oxidative stress.

The diet is similar to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern: heavy on fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, lean meats, fish, poultry, and low- or nonfat dairy, and light on sugar and salt.

To see whether a DASH diet pattern could have similarly beneficial effects on cognition and memory, the authors studied 818 adults who participated in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) and who agreed to fill out a 139-item food frequency questionnaire.

MAP enrolled residents from 40 retirement communities who were dementia free at enrollment and who agreed to have annual cognitive and motor tests and blood draws. Participants also agreed to donate their brains, spinal cords, muscles, and nerve tissue at death.

Participants were tested at baseline and annually with a summary measure of 19 tests assessing global cognitive function in domains of episodic, semantic, and working memory; visuospatial ability; and perceptual speed. Tests scores were standardized and averaged to come up with the composite measure.

Adherence to the DASH diet was scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 10 being a perfect score. The study participants had a mean DASH score of 4.1 (range, 1.5-8.5).

The investigators created linear mixed models incorporating global cognition, individual cognitive domains, DASH total scores, and scores for 10 dietary components. They also created a basic model adjusted for age, sex, education, and total caloric intake, with further adjustment for apolipoprotein E (apo E) status and depression.

Median DASH scores ranged from 2.5 in the lowest tertile to 4.0 in the middle to 5.5 in the highest tertile. At baseline, the mean global cognitive score was 0.14 (range, –3.24 to 1.61).

Over an average of 4.7 years of follow-up, DASH scores were significantly associated in a linear fashion (the higher the score, the slower the rate of decline) in the basic model alone and after adjustment for apo E status (P = .005) and after adjustment for both apo E and depression (P = .006).

The association was significant for all cognitive domains except visuospatial abilities, which trended toward significance but did not reach it (P = .06).

Dietary components significantly associated with slower decline include vegetables (P = .02); nuts, seeds, and legumes (P = .01); total fat (P = .05); and saturated fat (P = .01).

The Rush MAP is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Elsie Heller Brain Bank Endowment Fund, and a Rush University endowment. Dr. Morris reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Eating well may be the best revenge against cognitive decline, a study has shown.

Among 818 dementia-free participants in a longitudinal study of memory and aging, those who adhered to the basic components of the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet had a slower rate of cognitive decline than others who followed more typical American diets, reported Martha Clare Morris, Sc.D., professor and director of the section of nutrition and nutritional epidemiology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

The relationship between diet and cognition was linear, with people who most closely followed the DASH dietary pattern having the slowest rates of decline, Dr. Morris said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

"The individual dietary components that were contributing to this slower decline were higher servings of vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes, and lower intake of total and saturated fats," she said.

The investigators chose to look at dietary patterns because they provide an index of overall dietary quality and incorporate the interactions or synergies that may occur among food groups that constitute a specific pattern.

The DASH diet has been shown to lower blood pressure, increase insulin sensitivity, and reduce weight, serum cholesterol level, inflammation, and oxidative stress.

The diet is similar to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern: heavy on fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, lean meats, fish, poultry, and low- or nonfat dairy, and light on sugar and salt.

To see whether a DASH diet pattern could have similarly beneficial effects on cognition and memory, the authors studied 818 adults who participated in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) and who agreed to fill out a 139-item food frequency questionnaire.

MAP enrolled residents from 40 retirement communities who were dementia free at enrollment and who agreed to have annual cognitive and motor tests and blood draws. Participants also agreed to donate their brains, spinal cords, muscles, and nerve tissue at death.

Participants were tested at baseline and annually with a summary measure of 19 tests assessing global cognitive function in domains of episodic, semantic, and working memory; visuospatial ability; and perceptual speed. Tests scores were standardized and averaged to come up with the composite measure.

Adherence to the DASH diet was scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 10 being a perfect score. The study participants had a mean DASH score of 4.1 (range, 1.5-8.5).

The investigators created linear mixed models incorporating global cognition, individual cognitive domains, DASH total scores, and scores for 10 dietary components. They also created a basic model adjusted for age, sex, education, and total caloric intake, with further adjustment for apolipoprotein E (apo E) status and depression.

Median DASH scores ranged from 2.5 in the lowest tertile to 4.0 in the middle to 5.5 in the highest tertile. At baseline, the mean global cognitive score was 0.14 (range, –3.24 to 1.61).

Over an average of 4.7 years of follow-up, DASH scores were significantly associated in a linear fashion (the higher the score, the slower the rate of decline) in the basic model alone and after adjustment for apo E status (P = .005) and after adjustment for both apo E and depression (P = .006).

The association was significant for all cognitive domains except visuospatial abilities, which trended toward significance but did not reach it (P = .06).

Dietary components significantly associated with slower decline include vegetables (P = .02); nuts, seeds, and legumes (P = .01); total fat (P = .05); and saturated fat (P = .01).

The Rush MAP is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Elsie Heller Brain Bank Endowment Fund, and a Rush University endowment. Dr. Morris reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AAIC 2013

Major finding: Closer adherence to the components of the DASH diet was significantly associated with a slower rate of cognitive decline.

Data source: A prospective, longitudinal study of 818 participants in the Rush Memory and Aging Project.

Disclosures: The Rush MAP is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Elsie Heller Brain Bank Endowment Fund, and a Rush University endowment. Dr. Morris reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Florbetapir PET may rule out amyloidosis and Alzheimer’s disease

BOSTON – Brain amyloid imaging may help clinicians to rule Alzheimer’s disease in or out and spare patients with other forms of dementia from the possibly harmful effects of antiamyloid therapies, a small study has shown.

In a case series of 20 patients who were given clinical diagnoses that included frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease, and mild cognitive impairment, PET scanning with the radiotracer florbetapir 18F (Amyvid) was positive and consistent in scans of patients with diagnoses of AD or amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and was negative in scans of patients with Parkinson’s disease, delayed post-traumatic cognitive impairment, depression, and normal cognition.

One of the patients was a retired National Football League player with a history of multiple concussions. Although neuropsychologists and neurologists disagreed on a diagnosis of possible AD, florbetapir 18F PET imaging helped them confirm a diagnosis of delayed post-traumatic cognitive impairment without amyloidosis and with possible chronic traumatic encephalopathy, said Effie Mitsis, Ph.D., of the department of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

"If this guy came to our Alzheimer’s disease research center without the scan, undoubtedly one of the neurologists would have put him on an antiamyloid agent and put him into a clinical trial," she said in an interview.

Florbetapir is a radioligand that attaches to amyloid plaques in the brain. Dr. Mitsis and her colleagues use the agent as part of a comprehensive clinical dementia evaluation.

In the series she reported, florbetapir PET scans were negative in all of three patients diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia, and in two of three patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia.

In one patient diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and AD, the scans were positive, and in another diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and depression, the scans were negative, the investigators found.

Of four patients with a diagnosis of amnestic mild cognitive impairment and five with a diagnosis of AD alone, all scans were positive. In contrast, in the one patient with a diagnosis of depression but no neurodegenerative disease, the scans were negative.

Dazed and confused after games

Scans were negative in two patients with normal cognition, and in the former NFL player.

He had retired from the game after a 10-year professional career, during which time he had multiple concussions.

"By 12 hours post game, he was at times unable to name which team he had just played against. He does not recall loss of consciousness, but was dazed and confused sometimes up to a full day afterward. On several occasions, the player had difficulty finding his way home after a game," Dr. Mitsis reported in a poster presentation at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

A designated NFL Neurological Care Program team consisting of a neurologist, a neurologic psychiatrist, a neuropsychologist, neuroradiologists, and nuclear medicine physicians had evaluated him with validated cognitive and memory instruments, and determined that he had impairments in information-processing speed, verbal comprehension, and immediate and delayed word recall, but still had intellectual function and learning ability.

Dr. Mitsis and another neuropsychologist independently reviewed the test results and agreed on the inclusion of possible AD in the diagnosis, a finding that was opposed by all but one member of the original evaluation team.

With florbetapir PET scanning, however, they were able to exclude a diagnosis of cerebral amyloidosis, thereby ruling out AD, Dr. Mitsis said.

The research was supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Mitsis reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Brain amyloid imaging may help clinicians to rule Alzheimer’s disease in or out and spare patients with other forms of dementia from the possibly harmful effects of antiamyloid therapies, a small study has shown.

In a case series of 20 patients who were given clinical diagnoses that included frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease, and mild cognitive impairment, PET scanning with the radiotracer florbetapir 18F (Amyvid) was positive and consistent in scans of patients with diagnoses of AD or amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and was negative in scans of patients with Parkinson’s disease, delayed post-traumatic cognitive impairment, depression, and normal cognition.

One of the patients was a retired National Football League player with a history of multiple concussions. Although neuropsychologists and neurologists disagreed on a diagnosis of possible AD, florbetapir 18F PET imaging helped them confirm a diagnosis of delayed post-traumatic cognitive impairment without amyloidosis and with possible chronic traumatic encephalopathy, said Effie Mitsis, Ph.D., of the department of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

"If this guy came to our Alzheimer’s disease research center without the scan, undoubtedly one of the neurologists would have put him on an antiamyloid agent and put him into a clinical trial," she said in an interview.

Florbetapir is a radioligand that attaches to amyloid plaques in the brain. Dr. Mitsis and her colleagues use the agent as part of a comprehensive clinical dementia evaluation.

In the series she reported, florbetapir PET scans were negative in all of three patients diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia, and in two of three patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia.

In one patient diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and AD, the scans were positive, and in another diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and depression, the scans were negative, the investigators found.

Of four patients with a diagnosis of amnestic mild cognitive impairment and five with a diagnosis of AD alone, all scans were positive. In contrast, in the one patient with a diagnosis of depression but no neurodegenerative disease, the scans were negative.

Dazed and confused after games

Scans were negative in two patients with normal cognition, and in the former NFL player.

He had retired from the game after a 10-year professional career, during which time he had multiple concussions.

"By 12 hours post game, he was at times unable to name which team he had just played against. He does not recall loss of consciousness, but was dazed and confused sometimes up to a full day afterward. On several occasions, the player had difficulty finding his way home after a game," Dr. Mitsis reported in a poster presentation at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

A designated NFL Neurological Care Program team consisting of a neurologist, a neurologic psychiatrist, a neuropsychologist, neuroradiologists, and nuclear medicine physicians had evaluated him with validated cognitive and memory instruments, and determined that he had impairments in information-processing speed, verbal comprehension, and immediate and delayed word recall, but still had intellectual function and learning ability.

Dr. Mitsis and another neuropsychologist independently reviewed the test results and agreed on the inclusion of possible AD in the diagnosis, a finding that was opposed by all but one member of the original evaluation team.

With florbetapir PET scanning, however, they were able to exclude a diagnosis of cerebral amyloidosis, thereby ruling out AD, Dr. Mitsis said.

The research was supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Mitsis reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Brain amyloid imaging may help clinicians to rule Alzheimer’s disease in or out and spare patients with other forms of dementia from the possibly harmful effects of antiamyloid therapies, a small study has shown.

In a case series of 20 patients who were given clinical diagnoses that included frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease, and mild cognitive impairment, PET scanning with the radiotracer florbetapir 18F (Amyvid) was positive and consistent in scans of patients with diagnoses of AD or amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and was negative in scans of patients with Parkinson’s disease, delayed post-traumatic cognitive impairment, depression, and normal cognition.

One of the patients was a retired National Football League player with a history of multiple concussions. Although neuropsychologists and neurologists disagreed on a diagnosis of possible AD, florbetapir 18F PET imaging helped them confirm a diagnosis of delayed post-traumatic cognitive impairment without amyloidosis and with possible chronic traumatic encephalopathy, said Effie Mitsis, Ph.D., of the department of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

"If this guy came to our Alzheimer’s disease research center without the scan, undoubtedly one of the neurologists would have put him on an antiamyloid agent and put him into a clinical trial," she said in an interview.

Florbetapir is a radioligand that attaches to amyloid plaques in the brain. Dr. Mitsis and her colleagues use the agent as part of a comprehensive clinical dementia evaluation.

In the series she reported, florbetapir PET scans were negative in all of three patients diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia, and in two of three patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia.

In one patient diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and AD, the scans were positive, and in another diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and depression, the scans were negative, the investigators found.

Of four patients with a diagnosis of amnestic mild cognitive impairment and five with a diagnosis of AD alone, all scans were positive. In contrast, in the one patient with a diagnosis of depression but no neurodegenerative disease, the scans were negative.

Dazed and confused after games

Scans were negative in two patients with normal cognition, and in the former NFL player.

He had retired from the game after a 10-year professional career, during which time he had multiple concussions.

"By 12 hours post game, he was at times unable to name which team he had just played against. He does not recall loss of consciousness, but was dazed and confused sometimes up to a full day afterward. On several occasions, the player had difficulty finding his way home after a game," Dr. Mitsis reported in a poster presentation at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

A designated NFL Neurological Care Program team consisting of a neurologist, a neurologic psychiatrist, a neuropsychologist, neuroradiologists, and nuclear medicine physicians had evaluated him with validated cognitive and memory instruments, and determined that he had impairments in information-processing speed, verbal comprehension, and immediate and delayed word recall, but still had intellectual function and learning ability.

Dr. Mitsis and another neuropsychologist independently reviewed the test results and agreed on the inclusion of possible AD in the diagnosis, a finding that was opposed by all but one member of the original evaluation team.

With florbetapir PET scanning, however, they were able to exclude a diagnosis of cerebral amyloidosis, thereby ruling out AD, Dr. Mitsis said.

The research was supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Mitsis reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AAIC 2013

Major finding: Brain amyloid imaging with florbetapir 18F PET was consistently positive in patients with amyloid pathology, and negative in patients without cerebral amyloidosis except in one case.

Data source: A case series of 20 patients with various clinical diagnoses of dementia or cognitive problems.

Disclosures: The research was supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Mitsis reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Two-minute Alzheimer’s test? Not so fast!

BOSTON – The quality of websites that purport to help visitors or other people acting on their behalf to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease are very low and should not be used for such a purpose, cautioned an investigator at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

Independent panelists who reviewed 16 online tests for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) found that none provided validated results, and all were sorely lacking in ethical standards, reported Julie Robillard, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at the National Core for Neuroethics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

More than half of all Americans aged 65 years and older use the Internet, and approximately 80% of all adults find health information online, Dr. Robillard noted.

"There’s an increasingly popular behavior online, which is self-diagnosis, and the truth is we have almost no information about the quality of information about Alzheimer’s online," she said.

To at least partially fill in this knowledge gap, she and her colleagues conducted a keyword search to identify 16 freely available online tests purporting to be for Alzheimer’s disease and asked two independent panels of expert reviewers to rate each test on a scale of 1 (very poor) to 10 (excellent) for content, breadth, peer review, and reliability.

The tests were found on news, not-for-profit, academic, commercial, and entertainment sites, with monthly traffic ranging from 200 to 8.8 million unique visits. At least one test could be completed in about 2 minutes; others took as long as 1 hour to complete, Dr. Robillard estimated.

"So, in 2 minutes, you can go online and find out if you have Alzheimer’s disease," she joked.

Thirteen were designed to be self tests, and three were designed to be filled out by a proxy such as a relative or friend. Six sites relied primarily on questionnaires asking about risk factors and symptoms, and 10 used performance measures.

The tests gave users a variety of possible outcomes. For example, nine tests classified users as not at risk, at risk, or as already having AD. Another three rated responses on a continuum based on test answers. Of the four remaining tests, two were pass/fail, one was fail only, and one offered no outcomes.

The scientific validity and reliability of the tests were rated as mediocre at best by the panelists, indicating that the tests were generally poor at achieving their stated goals. The tests were generally poor at including current peer-reviewed evidence, and the experts also said that test/retest reliability was also quite poor.

Experts in human-computer interaction gave decent marks (scores of about 7) for their ease of use. But clinicians, ethicists, and neuropsychologists were less forgiving on whether the tests could detect if the user was performing properly or merely playing around and how easy the tests were to use for those with lower levels of computer literacy. None rated the usability of any test much higher than 5.

None of the tests rated better than poor for meeting various ethical standards, such as providing upfront information about the nature and scope of the test, informed consent, and privacy discussions. The panelists also gave poor ratings to the tests’ wording of outcomes, the clarity of their interpretation, and their provision of appropriate advice for follow-up. Conflict-of-interest disclosures were not present, either.

"Is self-diagnosis appropriate at all? I think that professional consensus is that it’s not, so we have to wonder how we handle these tests being online and people doing them," Dr. Robillard said.

Her next step will be to explore in depth the potential harms or benefits of online dementia screening and to evaluate how such testing may affect clinician/patient relationships.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research and the Canadian Dementia Knowledge Translation Network. Dr. Robillard disclosed that two of her coauthors are involved in developing a computerized testing tool for mild cognitive impairment and dementia for use in specialty-care settings. Dr. Robillard reported having no personal disclosures.

BOSTON – The quality of websites that purport to help visitors or other people acting on their behalf to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease are very low and should not be used for such a purpose, cautioned an investigator at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

Independent panelists who reviewed 16 online tests for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) found that none provided validated results, and all were sorely lacking in ethical standards, reported Julie Robillard, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at the National Core for Neuroethics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

More than half of all Americans aged 65 years and older use the Internet, and approximately 80% of all adults find health information online, Dr. Robillard noted.

"There’s an increasingly popular behavior online, which is self-diagnosis, and the truth is we have almost no information about the quality of information about Alzheimer’s online," she said.

To at least partially fill in this knowledge gap, she and her colleagues conducted a keyword search to identify 16 freely available online tests purporting to be for Alzheimer’s disease and asked two independent panels of expert reviewers to rate each test on a scale of 1 (very poor) to 10 (excellent) for content, breadth, peer review, and reliability.

The tests were found on news, not-for-profit, academic, commercial, and entertainment sites, with monthly traffic ranging from 200 to 8.8 million unique visits. At least one test could be completed in about 2 minutes; others took as long as 1 hour to complete, Dr. Robillard estimated.

"So, in 2 minutes, you can go online and find out if you have Alzheimer’s disease," she joked.

Thirteen were designed to be self tests, and three were designed to be filled out by a proxy such as a relative or friend. Six sites relied primarily on questionnaires asking about risk factors and symptoms, and 10 used performance measures.

The tests gave users a variety of possible outcomes. For example, nine tests classified users as not at risk, at risk, or as already having AD. Another three rated responses on a continuum based on test answers. Of the four remaining tests, two were pass/fail, one was fail only, and one offered no outcomes.

The scientific validity and reliability of the tests were rated as mediocre at best by the panelists, indicating that the tests were generally poor at achieving their stated goals. The tests were generally poor at including current peer-reviewed evidence, and the experts also said that test/retest reliability was also quite poor.

Experts in human-computer interaction gave decent marks (scores of about 7) for their ease of use. But clinicians, ethicists, and neuropsychologists were less forgiving on whether the tests could detect if the user was performing properly or merely playing around and how easy the tests were to use for those with lower levels of computer literacy. None rated the usability of any test much higher than 5.

None of the tests rated better than poor for meeting various ethical standards, such as providing upfront information about the nature and scope of the test, informed consent, and privacy discussions. The panelists also gave poor ratings to the tests’ wording of outcomes, the clarity of their interpretation, and their provision of appropriate advice for follow-up. Conflict-of-interest disclosures were not present, either.

"Is self-diagnosis appropriate at all? I think that professional consensus is that it’s not, so we have to wonder how we handle these tests being online and people doing them," Dr. Robillard said.

Her next step will be to explore in depth the potential harms or benefits of online dementia screening and to evaluate how such testing may affect clinician/patient relationships.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research and the Canadian Dementia Knowledge Translation Network. Dr. Robillard disclosed that two of her coauthors are involved in developing a computerized testing tool for mild cognitive impairment and dementia for use in specialty-care settings. Dr. Robillard reported having no personal disclosures.

BOSTON – The quality of websites that purport to help visitors or other people acting on their behalf to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease are very low and should not be used for such a purpose, cautioned an investigator at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

Independent panelists who reviewed 16 online tests for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) found that none provided validated results, and all were sorely lacking in ethical standards, reported Julie Robillard, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at the National Core for Neuroethics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

More than half of all Americans aged 65 years and older use the Internet, and approximately 80% of all adults find health information online, Dr. Robillard noted.

"There’s an increasingly popular behavior online, which is self-diagnosis, and the truth is we have almost no information about the quality of information about Alzheimer’s online," she said.

To at least partially fill in this knowledge gap, she and her colleagues conducted a keyword search to identify 16 freely available online tests purporting to be for Alzheimer’s disease and asked two independent panels of expert reviewers to rate each test on a scale of 1 (very poor) to 10 (excellent) for content, breadth, peer review, and reliability.

The tests were found on news, not-for-profit, academic, commercial, and entertainment sites, with monthly traffic ranging from 200 to 8.8 million unique visits. At least one test could be completed in about 2 minutes; others took as long as 1 hour to complete, Dr. Robillard estimated.

"So, in 2 minutes, you can go online and find out if you have Alzheimer’s disease," she joked.

Thirteen were designed to be self tests, and three were designed to be filled out by a proxy such as a relative or friend. Six sites relied primarily on questionnaires asking about risk factors and symptoms, and 10 used performance measures.

The tests gave users a variety of possible outcomes. For example, nine tests classified users as not at risk, at risk, or as already having AD. Another three rated responses on a continuum based on test answers. Of the four remaining tests, two were pass/fail, one was fail only, and one offered no outcomes.

The scientific validity and reliability of the tests were rated as mediocre at best by the panelists, indicating that the tests were generally poor at achieving their stated goals. The tests were generally poor at including current peer-reviewed evidence, and the experts also said that test/retest reliability was also quite poor.

Experts in human-computer interaction gave decent marks (scores of about 7) for their ease of use. But clinicians, ethicists, and neuropsychologists were less forgiving on whether the tests could detect if the user was performing properly or merely playing around and how easy the tests were to use for those with lower levels of computer literacy. None rated the usability of any test much higher than 5.

None of the tests rated better than poor for meeting various ethical standards, such as providing upfront information about the nature and scope of the test, informed consent, and privacy discussions. The panelists also gave poor ratings to the tests’ wording of outcomes, the clarity of their interpretation, and their provision of appropriate advice for follow-up. Conflict-of-interest disclosures were not present, either.

"Is self-diagnosis appropriate at all? I think that professional consensus is that it’s not, so we have to wonder how we handle these tests being online and people doing them," Dr. Robillard said.

Her next step will be to explore in depth the potential harms or benefits of online dementia screening and to evaluate how such testing may affect clinician/patient relationships.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research and the Canadian Dementia Knowledge Translation Network. Dr. Robillard disclosed that two of her coauthors are involved in developing a computerized testing tool for mild cognitive impairment and dementia for use in specialty-care settings. Dr. Robillard reported having no personal disclosures.

AT AAIC 2013

Major finding: All of 16 online tests for Alzheimer’s disease were rated as poor in all respects by two expert panels.

Data source: Evaluation of 16 freely available Internet-based tests purported to screen for Alzheimer’s disease.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research and the Canadian Dementia Knowledge Translation Network. Dr. Robillard disclosed that two of her coauthors are involved in developing a computerized testing tool for mild cognitive impairment and dementia for use in specialty-care settings. Dr. Robillard reported having no personal disclosures.

Subjective cognitive decline may be early omen of Alzheimer’s

BOSTON – Patients who complain of memory and cognition problems may be experiencing early, subtle signs of Alzheimer’s disease, according to findings from four separate studies presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

A study of 2,319 elderly patients with no dementia at baseline and no mild cognitive impairment (MCI) showed that patients who reported subjective memory impairment (SMI) had a significantly greater decline than control subjects in episodic memory (immediate and delayed recall), and that patients with SMI with self-reported concerns about memory had a greater slope of decline, reported Alexander Koppara, a PhD candidate at the Universitätsklinikum Bonn in Germany.

Depression also was associated with cognitive performance at baseline, but the effects of SMI remained when the investigators controlled for depression, he said.

"Even if we introduce depression as a covariate of development over time, depression is not a significant predictor of cognitive decline, which is in line with a lot of findings in psychiatry. That is why subjects who report subjective memory impairment should be tracked over a long period of time," Mr. Koppara said.

He added that a multimodal approach combining studies of biomarkers with experimental assessment tools could help to further objectify clinical impressions from subjective memory and cognition symptoms.

Amyloid mirrors memory concerns

The findings of Mr. Koppara’s group were supported by a second study indicating that, among 200 healthy, clinically normal older adults, those who reported more concerns than their nonworried peers about problems with cognition and memory had more evidence of beta-amyloid protein buildup in the brain, as seen with PET scans with the amyloid tracing agent 11C-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B.

In addition, among subjects with higher levels of education and reading ability, the greater the level of concern, the greater the degree of amyloid deposition, said Rebecca E. Amariglio, Ph.D., a clinical neuropsychologist at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

"We also took a look at reports of concerns by an informant, or somebody who knew these subjects well, like a family member or a friend, and we did not see a relationship with amyloid," she said at a media briefing. "There seems to be something specific to someone’s own knowledge of their abilities that isn’t quite captured by an informant at this stage, the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease."

Dr. Amariglio emphasized that many subjective memory changes should not be cause for concern. For example, it’s normal for an older person to walk into a room and forget why he or she went there, have difficulty retrieving names of unfamiliar people, or have changes in memory, compared with young adulthood.

What is abnormal, and may be a trigger for clinical evaluation, is getting lost in familiar surroundings, having difficulty remembering important details of recent events, trouble following the plot of a TV program or book because of memory, or having noticeably worse memory than friends of the same age, she said.

Subjective symptoms in high-risk allele carriers

Dr. Amariglio was coauthor of a second study looking at women aged 70 years and older with no history of stroke who were participants in the Nurses Health Study. The investigators looked at a subjective memory symptom score based on self-report of up to seven specific, subjective memory symptoms and compared it with verbal memory decline over 6 years among 889 women with one or two copies of the high-risk apolipoprotein E epsilon-4 (APOE epsilon-4) allele and 2,972 APOE epsilon-4 noncarriers.

They found that, for both APOE epsilon-4 carriers and noncarriers, higher numbers of subjective memory symptoms at baseline were related to poorer verbal memory scores (P for trend less than .001 for both groups). In addition, after adjusting for age and the presence of depression, women with more subjective memory symptoms at baseline also had higher rates of verbal memory decline over time (P for trend = .006 for APOE epsilon-4 carriers and less than .001 for noncarriers).

Interestingly, only one subjective memory symptom at baseline was needed to accurately predict verbal memory decline over time among APOE epsilon-4 carriers, compared with three or more needed to predict decline in noncarriers.

"Self-report of memory concerns may be useful for identifying individuals at greater risk of memory decline, particularly within [APOE epsilon-4] carriers, a group at higher risk of memory decline and Alzheimer’s disease dementia," said lead author Cecilia Samieri, Ph.D., an epidemiologist and researcher at the University of Bordeaux in France.

Self-reported symptoms during longitudinal study

Additional evidence for the link between subjective cognitive decline and MCI or dementia comes from the BRAINS (Biologically Resilient Adults in Neurological Studies) longitudinal study. Richard J. Kryscio, Ph.D., a professor of statistics and faculty member in the Sanders-Brown Center on Aging at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and his colleagues looked at 531 men and women with a mean age of 73 who underwent annual cognitive assessments for a mean of 10 years.

Before each exam, the participants were asked, "Have you noticed a change in your memory since the last visit?" More than half of the participants (55.7%) said yes, reporting subjective memory complaints during the study.

The investigators found that a person with a subjective memory complaint had 2.8-fold greater risk of developing MCI or dementia later in life, compared with someone who did not respond in the affirmative.

Dr. Kryscio cautioned, however, that a positive subjective memory complaint "is no guarantee that MCI or dementia will follow."

Dr. Koppara’s study was funded by the AgeCoDe Study Group and the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases. The two studies authored by Dr. Amariglio and Dr. Samieri were supported by the National Institutes of Health and France’s Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale. Dr. Kryscio’s study was supported by the National Institute on Aging. The authors all reported having no relevant disclosures.

BOSTON – Patients who complain of memory and cognition problems may be experiencing early, subtle signs of Alzheimer’s disease, according to findings from four separate studies presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

A study of 2,319 elderly patients with no dementia at baseline and no mild cognitive impairment (MCI) showed that patients who reported subjective memory impairment (SMI) had a significantly greater decline than control subjects in episodic memory (immediate and delayed recall), and that patients with SMI with self-reported concerns about memory had a greater slope of decline, reported Alexander Koppara, a PhD candidate at the Universitätsklinikum Bonn in Germany.

Depression also was associated with cognitive performance at baseline, but the effects of SMI remained when the investigators controlled for depression, he said.

"Even if we introduce depression as a covariate of development over time, depression is not a significant predictor of cognitive decline, which is in line with a lot of findings in psychiatry. That is why subjects who report subjective memory impairment should be tracked over a long period of time," Mr. Koppara said.

He added that a multimodal approach combining studies of biomarkers with experimental assessment tools could help to further objectify clinical impressions from subjective memory and cognition symptoms.

Amyloid mirrors memory concerns

The findings of Mr. Koppara’s group were supported by a second study indicating that, among 200 healthy, clinically normal older adults, those who reported more concerns than their nonworried peers about problems with cognition and memory had more evidence of beta-amyloid protein buildup in the brain, as seen with PET scans with the amyloid tracing agent 11C-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B.

In addition, among subjects with higher levels of education and reading ability, the greater the level of concern, the greater the degree of amyloid deposition, said Rebecca E. Amariglio, Ph.D., a clinical neuropsychologist at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

"We also took a look at reports of concerns by an informant, or somebody who knew these subjects well, like a family member or a friend, and we did not see a relationship with amyloid," she said at a media briefing. "There seems to be something specific to someone’s own knowledge of their abilities that isn’t quite captured by an informant at this stage, the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease."

Dr. Amariglio emphasized that many subjective memory changes should not be cause for concern. For example, it’s normal for an older person to walk into a room and forget why he or she went there, have difficulty retrieving names of unfamiliar people, or have changes in memory, compared with young adulthood.

What is abnormal, and may be a trigger for clinical evaluation, is getting lost in familiar surroundings, having difficulty remembering important details of recent events, trouble following the plot of a TV program or book because of memory, or having noticeably worse memory than friends of the same age, she said.

Subjective symptoms in high-risk allele carriers

Dr. Amariglio was coauthor of a second study looking at women aged 70 years and older with no history of stroke who were participants in the Nurses Health Study. The investigators looked at a subjective memory symptom score based on self-report of up to seven specific, subjective memory symptoms and compared it with verbal memory decline over 6 years among 889 women with one or two copies of the high-risk apolipoprotein E epsilon-4 (APOE epsilon-4) allele and 2,972 APOE epsilon-4 noncarriers.

They found that, for both APOE epsilon-4 carriers and noncarriers, higher numbers of subjective memory symptoms at baseline were related to poorer verbal memory scores (P for trend less than .001 for both groups). In addition, after adjusting for age and the presence of depression, women with more subjective memory symptoms at baseline also had higher rates of verbal memory decline over time (P for trend = .006 for APOE epsilon-4 carriers and less than .001 for noncarriers).

Interestingly, only one subjective memory symptom at baseline was needed to accurately predict verbal memory decline over time among APOE epsilon-4 carriers, compared with three or more needed to predict decline in noncarriers.

"Self-report of memory concerns may be useful for identifying individuals at greater risk of memory decline, particularly within [APOE epsilon-4] carriers, a group at higher risk of memory decline and Alzheimer’s disease dementia," said lead author Cecilia Samieri, Ph.D., an epidemiologist and researcher at the University of Bordeaux in France.

Self-reported symptoms during longitudinal study

Additional evidence for the link between subjective cognitive decline and MCI or dementia comes from the BRAINS (Biologically Resilient Adults in Neurological Studies) longitudinal study. Richard J. Kryscio, Ph.D., a professor of statistics and faculty member in the Sanders-Brown Center on Aging at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and his colleagues looked at 531 men and women with a mean age of 73 who underwent annual cognitive assessments for a mean of 10 years.

Before each exam, the participants were asked, "Have you noticed a change in your memory since the last visit?" More than half of the participants (55.7%) said yes, reporting subjective memory complaints during the study.

The investigators found that a person with a subjective memory complaint had 2.8-fold greater risk of developing MCI or dementia later in life, compared with someone who did not respond in the affirmative.

Dr. Kryscio cautioned, however, that a positive subjective memory complaint "is no guarantee that MCI or dementia will follow."

Dr. Koppara’s study was funded by the AgeCoDe Study Group and the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases. The two studies authored by Dr. Amariglio and Dr. Samieri were supported by the National Institutes of Health and France’s Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale. Dr. Kryscio’s study was supported by the National Institute on Aging. The authors all reported having no relevant disclosures.

BOSTON – Patients who complain of memory and cognition problems may be experiencing early, subtle signs of Alzheimer’s disease, according to findings from four separate studies presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

A study of 2,319 elderly patients with no dementia at baseline and no mild cognitive impairment (MCI) showed that patients who reported subjective memory impairment (SMI) had a significantly greater decline than control subjects in episodic memory (immediate and delayed recall), and that patients with SMI with self-reported concerns about memory had a greater slope of decline, reported Alexander Koppara, a PhD candidate at the Universitätsklinikum Bonn in Germany.

Depression also was associated with cognitive performance at baseline, but the effects of SMI remained when the investigators controlled for depression, he said.

"Even if we introduce depression as a covariate of development over time, depression is not a significant predictor of cognitive decline, which is in line with a lot of findings in psychiatry. That is why subjects who report subjective memory impairment should be tracked over a long period of time," Mr. Koppara said.

He added that a multimodal approach combining studies of biomarkers with experimental assessment tools could help to further objectify clinical impressions from subjective memory and cognition symptoms.

Amyloid mirrors memory concerns

The findings of Mr. Koppara’s group were supported by a second study indicating that, among 200 healthy, clinically normal older adults, those who reported more concerns than their nonworried peers about problems with cognition and memory had more evidence of beta-amyloid protein buildup in the brain, as seen with PET scans with the amyloid tracing agent 11C-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B.

In addition, among subjects with higher levels of education and reading ability, the greater the level of concern, the greater the degree of amyloid deposition, said Rebecca E. Amariglio, Ph.D., a clinical neuropsychologist at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

"We also took a look at reports of concerns by an informant, or somebody who knew these subjects well, like a family member or a friend, and we did not see a relationship with amyloid," she said at a media briefing. "There seems to be something specific to someone’s own knowledge of their abilities that isn’t quite captured by an informant at this stage, the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease."

Dr. Amariglio emphasized that many subjective memory changes should not be cause for concern. For example, it’s normal for an older person to walk into a room and forget why he or she went there, have difficulty retrieving names of unfamiliar people, or have changes in memory, compared with young adulthood.

What is abnormal, and may be a trigger for clinical evaluation, is getting lost in familiar surroundings, having difficulty remembering important details of recent events, trouble following the plot of a TV program or book because of memory, or having noticeably worse memory than friends of the same age, she said.

Subjective symptoms in high-risk allele carriers

Dr. Amariglio was coauthor of a second study looking at women aged 70 years and older with no history of stroke who were participants in the Nurses Health Study. The investigators looked at a subjective memory symptom score based on self-report of up to seven specific, subjective memory symptoms and compared it with verbal memory decline over 6 years among 889 women with one or two copies of the high-risk apolipoprotein E epsilon-4 (APOE epsilon-4) allele and 2,972 APOE epsilon-4 noncarriers.

They found that, for both APOE epsilon-4 carriers and noncarriers, higher numbers of subjective memory symptoms at baseline were related to poorer verbal memory scores (P for trend less than .001 for both groups). In addition, after adjusting for age and the presence of depression, women with more subjective memory symptoms at baseline also had higher rates of verbal memory decline over time (P for trend = .006 for APOE epsilon-4 carriers and less than .001 for noncarriers).

Interestingly, only one subjective memory symptom at baseline was needed to accurately predict verbal memory decline over time among APOE epsilon-4 carriers, compared with three or more needed to predict decline in noncarriers.

"Self-report of memory concerns may be useful for identifying individuals at greater risk of memory decline, particularly within [APOE epsilon-4] carriers, a group at higher risk of memory decline and Alzheimer’s disease dementia," said lead author Cecilia Samieri, Ph.D., an epidemiologist and researcher at the University of Bordeaux in France.

Self-reported symptoms during longitudinal study

Additional evidence for the link between subjective cognitive decline and MCI or dementia comes from the BRAINS (Biologically Resilient Adults in Neurological Studies) longitudinal study. Richard J. Kryscio, Ph.D., a professor of statistics and faculty member in the Sanders-Brown Center on Aging at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and his colleagues looked at 531 men and women with a mean age of 73 who underwent annual cognitive assessments for a mean of 10 years.

Before each exam, the participants were asked, "Have you noticed a change in your memory since the last visit?" More than half of the participants (55.7%) said yes, reporting subjective memory complaints during the study.

The investigators found that a person with a subjective memory complaint had 2.8-fold greater risk of developing MCI or dementia later in life, compared with someone who did not respond in the affirmative.

Dr. Kryscio cautioned, however, that a positive subjective memory complaint "is no guarantee that MCI or dementia will follow."

Dr. Koppara’s study was funded by the AgeCoDe Study Group and the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases. The two studies authored by Dr. Amariglio and Dr. Samieri were supported by the National Institutes of Health and France’s Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale. Dr. Kryscio’s study was supported by the National Institute on Aging. The authors all reported having no relevant disclosures.

AT AAIC 2013

In vivo tau imaging confirms patient’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis

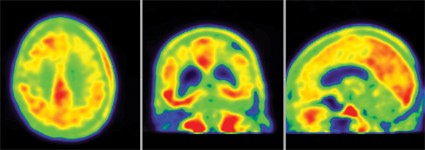

BOSTON – The first investigational tau radioligand for PET imaging has identified pathologic tangles in the brain of a man who was confirmed postmortem to have Alzheimer’s disease.

The patient who died was 1 of 12 participants in a study of the agent, [F-18]T808, and his imaging and neuropathologic results show that the agent binds exclusively to tau deposits, Hartmuth Kolb, Ph.D., said at a press conference at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

The 85-year-old man died of a pulmonary embolism 2 weeks after his [F-18]T808 scan. His death was unrelated to his diagnosis or to the imaging agent, Dr. Kolb said. Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, the company developing the tracer, obtained the brain for autopsy. The examination showed extensive tau tangles in exactly the same areas identified in a PET scan using [F-18]T808. Tau tangles show as red in the PET images; the warmer the shade, the more dense the tangles.

"The results were quite striking," said Dr. Kolb, senior vice president of research at Avid. "The Braak stage was a 5 or 6, which corresponded with a Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score of 15. On the scan, tau was all over the brain except for a sparing of the sensorimotor cortex, and that was exactly what we had found," in the postmortem exam.

The first human imaging cohort comprised nine patients with diagnosed Alzheimer’s and three healthy control subjects. Investigators compared the in vivo PET images with immunohistochemistry and with staining from fluorescent tau ligand T557, which is used to identify the protein in postmortem exams.

In patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, the [F-18]T808 scan showed strong positive correlations with the clinical exam in the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, parietal lobe, and hippocampus. The posterior cingulate gyrus and putamen were relatively spared, and the cerebellum was negative. Patients with an MMSE score of 24 showed moderate tau deposition. Scans of three patients who had an MMSE score of 19, 14, and 3, respectively, showed a progressively denser tau concentration.

There was no significant tau accumulation in any of the three healthy control subjects.

There was one outlier – a patient with an MMSE score of 12 who showed only a very small amount of tau. Dr. Kolb said this patient was probably misdiagnosed as having Alzheimer’s – a problem that continues to plague both clinicians and researchers.

"We don’t have numbers of how many people are misdiagnosed every year, but we do know it’s a big problem," Heather Snyder, Ph.D., director of medical and scientific operations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said in an interview. Misdiagnosis is "not only a mentally difficult thing to go through, but it can potentially keep someone from getting the correct care."

In vivo imaging of Alzheimer’s brain pathology is now held to be an imperative for moving Alzheimer’s research forward. The first agent, Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), which binds to amyloid plaques, has virtually revolutionized research by allowing direct visualization of plaques in living patients. PiB has helped to build a new understanding of prodromal and presymptomatic Alzheimer’s, and it has contributed greatly to patient stratification in clinical trials and to the ability to track therapeutic response.

But PiB is not particularly useful in a clinical setting due to its short, 20-minute half-life. Florbetapir (Amyvid), the investigational PET radioligand florbetaben, and [F-18]T808 all use the same fluorine isotope, making their half-lives 120 minutes and much more friendly for clinical use. [F-18]T808 reaches a plateau of action at about 40 minutes post injection, Dr. Kolb said.

Avid performed its study under an Investigational New Drug designation granted last year, Dr. Kolb said. The company will continue to accrue patients toward an approval request, but it didn’t speculate as to how long that might take, he noted.

[F-18]T808 was being developed by Siemens Medical Solutions USA until last April, when Avid, a subsidiary of Eli Lilly, purchased it along with another investigational tau radiotracer.

The other agent is named [F-18]T807, Lilly spokesperson Eva Catherine Groves said in an interview. She noted that "both have reported similar results and, as such, we plan to complete additional development work on both tracers prior to selecting at least one for advancement into our Alzheimer’s research and development programs."

Dr. Kolb is an employee of Avid Radiopharmaceuticals.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – The first investigational tau radioligand for PET imaging has identified pathologic tangles in the brain of a man who was confirmed postmortem to have Alzheimer’s disease.

The patient who died was 1 of 12 participants in a study of the agent, [F-18]T808, and his imaging and neuropathologic results show that the agent binds exclusively to tau deposits, Hartmuth Kolb, Ph.D., said at a press conference at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

The 85-year-old man died of a pulmonary embolism 2 weeks after his [F-18]T808 scan. His death was unrelated to his diagnosis or to the imaging agent, Dr. Kolb said. Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, the company developing the tracer, obtained the brain for autopsy. The examination showed extensive tau tangles in exactly the same areas identified in a PET scan using [F-18]T808. Tau tangles show as red in the PET images; the warmer the shade, the more dense the tangles.

"The results were quite striking," said Dr. Kolb, senior vice president of research at Avid. "The Braak stage was a 5 or 6, which corresponded with a Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score of 15. On the scan, tau was all over the brain except for a sparing of the sensorimotor cortex, and that was exactly what we had found," in the postmortem exam.

The first human imaging cohort comprised nine patients with diagnosed Alzheimer’s and three healthy control subjects. Investigators compared the in vivo PET images with immunohistochemistry and with staining from fluorescent tau ligand T557, which is used to identify the protein in postmortem exams.

In patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, the [F-18]T808 scan showed strong positive correlations with the clinical exam in the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, parietal lobe, and hippocampus. The posterior cingulate gyrus and putamen were relatively spared, and the cerebellum was negative. Patients with an MMSE score of 24 showed moderate tau deposition. Scans of three patients who had an MMSE score of 19, 14, and 3, respectively, showed a progressively denser tau concentration.

There was no significant tau accumulation in any of the three healthy control subjects.

There was one outlier – a patient with an MMSE score of 12 who showed only a very small amount of tau. Dr. Kolb said this patient was probably misdiagnosed as having Alzheimer’s – a problem that continues to plague both clinicians and researchers.

"We don’t have numbers of how many people are misdiagnosed every year, but we do know it’s a big problem," Heather Snyder, Ph.D., director of medical and scientific operations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said in an interview. Misdiagnosis is "not only a mentally difficult thing to go through, but it can potentially keep someone from getting the correct care."

In vivo imaging of Alzheimer’s brain pathology is now held to be an imperative for moving Alzheimer’s research forward. The first agent, Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), which binds to amyloid plaques, has virtually revolutionized research by allowing direct visualization of plaques in living patients. PiB has helped to build a new understanding of prodromal and presymptomatic Alzheimer’s, and it has contributed greatly to patient stratification in clinical trials and to the ability to track therapeutic response.

But PiB is not particularly useful in a clinical setting due to its short, 20-minute half-life. Florbetapir (Amyvid), the investigational PET radioligand florbetaben, and [F-18]T808 all use the same fluorine isotope, making their half-lives 120 minutes and much more friendly for clinical use. [F-18]T808 reaches a plateau of action at about 40 minutes post injection, Dr. Kolb said.

Avid performed its study under an Investigational New Drug designation granted last year, Dr. Kolb said. The company will continue to accrue patients toward an approval request, but it didn’t speculate as to how long that might take, he noted.

[F-18]T808 was being developed by Siemens Medical Solutions USA until last April, when Avid, a subsidiary of Eli Lilly, purchased it along with another investigational tau radiotracer.

The other agent is named [F-18]T807, Lilly spokesperson Eva Catherine Groves said in an interview. She noted that "both have reported similar results and, as such, we plan to complete additional development work on both tracers prior to selecting at least one for advancement into our Alzheimer’s research and development programs."

Dr. Kolb is an employee of Avid Radiopharmaceuticals.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – The first investigational tau radioligand for PET imaging has identified pathologic tangles in the brain of a man who was confirmed postmortem to have Alzheimer’s disease.

The patient who died was 1 of 12 participants in a study of the agent, [F-18]T808, and his imaging and neuropathologic results show that the agent binds exclusively to tau deposits, Hartmuth Kolb, Ph.D., said at a press conference at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

The 85-year-old man died of a pulmonary embolism 2 weeks after his [F-18]T808 scan. His death was unrelated to his diagnosis or to the imaging agent, Dr. Kolb said. Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, the company developing the tracer, obtained the brain for autopsy. The examination showed extensive tau tangles in exactly the same areas identified in a PET scan using [F-18]T808. Tau tangles show as red in the PET images; the warmer the shade, the more dense the tangles.

"The results were quite striking," said Dr. Kolb, senior vice president of research at Avid. "The Braak stage was a 5 or 6, which corresponded with a Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score of 15. On the scan, tau was all over the brain except for a sparing of the sensorimotor cortex, and that was exactly what we had found," in the postmortem exam.

The first human imaging cohort comprised nine patients with diagnosed Alzheimer’s and three healthy control subjects. Investigators compared the in vivo PET images with immunohistochemistry and with staining from fluorescent tau ligand T557, which is used to identify the protein in postmortem exams.

In patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, the [F-18]T808 scan showed strong positive correlations with the clinical exam in the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, parietal lobe, and hippocampus. The posterior cingulate gyrus and putamen were relatively spared, and the cerebellum was negative. Patients with an MMSE score of 24 showed moderate tau deposition. Scans of three patients who had an MMSE score of 19, 14, and 3, respectively, showed a progressively denser tau concentration.

There was no significant tau accumulation in any of the three healthy control subjects.

There was one outlier – a patient with an MMSE score of 12 who showed only a very small amount of tau. Dr. Kolb said this patient was probably misdiagnosed as having Alzheimer’s – a problem that continues to plague both clinicians and researchers.

"We don’t have numbers of how many people are misdiagnosed every year, but we do know it’s a big problem," Heather Snyder, Ph.D., director of medical and scientific operations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said in an interview. Misdiagnosis is "not only a mentally difficult thing to go through, but it can potentially keep someone from getting the correct care."

In vivo imaging of Alzheimer’s brain pathology is now held to be an imperative for moving Alzheimer’s research forward. The first agent, Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), which binds to amyloid plaques, has virtually revolutionized research by allowing direct visualization of plaques in living patients. PiB has helped to build a new understanding of prodromal and presymptomatic Alzheimer’s, and it has contributed greatly to patient stratification in clinical trials and to the ability to track therapeutic response.

But PiB is not particularly useful in a clinical setting due to its short, 20-minute half-life. Florbetapir (Amyvid), the investigational PET radioligand florbetaben, and [F-18]T808 all use the same fluorine isotope, making their half-lives 120 minutes and much more friendly for clinical use. [F-18]T808 reaches a plateau of action at about 40 minutes post injection, Dr. Kolb said.

Avid performed its study under an Investigational New Drug designation granted last year, Dr. Kolb said. The company will continue to accrue patients toward an approval request, but it didn’t speculate as to how long that might take, he noted.

[F-18]T808 was being developed by Siemens Medical Solutions USA until last April, when Avid, a subsidiary of Eli Lilly, purchased it along with another investigational tau radiotracer.

The other agent is named [F-18]T807, Lilly spokesperson Eva Catherine Groves said in an interview. She noted that "both have reported similar results and, as such, we plan to complete additional development work on both tracers prior to selecting at least one for advancement into our Alzheimer’s research and development programs."

Dr. Kolb is an employee of Avid Radiopharmaceuticals.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT AAIC 2013

Major finding: The results of in vivo tau tangle PET imaging with [F-18]T808 in a patient diagnosed with Alzheimer’s were later confirmed in a postmortem neuropathologic analysis.

Data source: A study of PET imaging with [F-18]T808 in nine patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and three healthy controls .

Disclosures: Dr. Kolb is an employee of Avid Radiopharmaceuticals.

Cancer survivors may have lower Alzheimer’s risk

BOSTON – It’s a trade-off that few people would be likely to make, but having cancer – particularly a type treated by chemotherapy – is associated with a significantly decreased risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease, a retrospective study has shown.

An inverse relationship was found between the incidence of the majority of different types of cancer and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk, in a review of the records of nearly 3.5 million U.S. veterans.

Liver cancer survivors had the lowest risk for AD (hazard ratio = 0.49), followed by survivors of pancreatic cancer (HR = 0.56), esophageal cancer (0.67), and multiple myeloma (0.74), reported Dr. Laura Frain of the geriatric research education and clinical center at Boston VA Medical Center.

However, survivors of prostate cancer had a small but significantly higher risk for AD (HR = 1.11), and other screening-detected cancers (colorectal cancer, melanoma) were not associated with a reduced risk, Dr. Frain and her associates found.

"There may be something different about prostate cancer survivors, but whether that’s biologic or related to the way that they’re screened is unclear," Dr. Frain said in an interview.

Many types of cancer were associated with an increased risk for non-AD dementias, with increased risks ranging from an HR of 1.11 for head and neck cancer to 2.64 for brain cancer.

The investigators attempted to control for the possibility that people with cancer may not survive long enough to develop frank dementia by looking at other age-related conditions, including stroke, osteoarthritis, cataracts, and macular degeneration. They found that all cancers were associated with an increased risk for other age-related conditions, suggesting that their findings of reduced AD risk were valid, Dr. Frain said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

Findings corroborated

The findings parallel those of a recently published study of more than 1 million residents of Northern Italy (Neurology 2013 July 10 [doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829c5ec1]). The investigators in that study found that "[t]he risk of cancer in patients with AD dementia was halved, and the risk of AD dementia in patients with cancer was 35% reduced. This relationship was observed in almost all subgroup analyses, suggesting that some anticipated potential confounding factors did not significantly influence the results."

Dr. Frain noted that three previous prospective cohort studies had found that older adults with cancer had a reduction in risk for incident AD, ranging from a 33% to a 60% decline. Those studies, however, were limited by small numbers of patients with cancer, limiting the ability to look for associations with specific cancer or treatment types.

The current study drew on data from the massive U.S. National Veterans Affairs Healthcare System to assemble a cohort of 3,499,378 veterans who received outpatient care within the system from 1997 to 2011. The investigators used regression analysis models adjusted for cancer treatment, multiple comorbidities, follow-up time, and number of visits per year before baseline. In addition, the researchers performed subanalyses of patients with diagnoses of prostate, lung, colorectal, and bladder cancers and lymphoma, with the models adjusted for cancer stage and grade.

The median age of the cohort was 71 years, 98% were males, and 66% were white. A total of 771,285 veterans (22%) had a cancer diagnosis. Of the 82,028 veterans who developed AD (2.3% of the entire cohort), 24% were cancer survivors, and the remainder had no cancer history.

The investigators also found that "treatment with chemotherapy conferred additional protection against AD in nearly all cancer types, suggesting that some forms of chemotherapy may have neuroprotective action."

Chemotherapy lowered the risk of AD associated with all cancers except prostate cancer by 20%-45%.

The investigators plan to look at individual categories of anticancer agents, and to see whether they may be common factors between cancer and AD in regard to proteins, genes, and biochemical pathways.

One intriguing target for exploration, Dr. Frain said, is peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 (PIN1), an enzyme that when upregulated has been associated with the pathogenesis of some forms of cancer, and when downregulated may be associated with the development of AD.

The study was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Frain is supported by a VA Special Fellowship in geriatrics.

BOSTON – It’s a trade-off that few people would be likely to make, but having cancer – particularly a type treated by chemotherapy – is associated with a significantly decreased risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease, a retrospective study has shown.

An inverse relationship was found between the incidence of the majority of different types of cancer and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk, in a review of the records of nearly 3.5 million U.S. veterans.

Liver cancer survivors had the lowest risk for AD (hazard ratio = 0.49), followed by survivors of pancreatic cancer (HR = 0.56), esophageal cancer (0.67), and multiple myeloma (0.74), reported Dr. Laura Frain of the geriatric research education and clinical center at Boston VA Medical Center.

However, survivors of prostate cancer had a small but significantly higher risk for AD (HR = 1.11), and other screening-detected cancers (colorectal cancer, melanoma) were not associated with a reduced risk, Dr. Frain and her associates found.

"There may be something different about prostate cancer survivors, but whether that’s biologic or related to the way that they’re screened is unclear," Dr. Frain said in an interview.

Many types of cancer were associated with an increased risk for non-AD dementias, with increased risks ranging from an HR of 1.11 for head and neck cancer to 2.64 for brain cancer.

The investigators attempted to control for the possibility that people with cancer may not survive long enough to develop frank dementia by looking at other age-related conditions, including stroke, osteoarthritis, cataracts, and macular degeneration. They found that all cancers were associated with an increased risk for other age-related conditions, suggesting that their findings of reduced AD risk were valid, Dr. Frain said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

Findings corroborated

The findings parallel those of a recently published study of more than 1 million residents of Northern Italy (Neurology 2013 July 10 [doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829c5ec1]). The investigators in that study found that "[t]he risk of cancer in patients with AD dementia was halved, and the risk of AD dementia in patients with cancer was 35% reduced. This relationship was observed in almost all subgroup analyses, suggesting that some anticipated potential confounding factors did not significantly influence the results."

Dr. Frain noted that three previous prospective cohort studies had found that older adults with cancer had a reduction in risk for incident AD, ranging from a 33% to a 60% decline. Those studies, however, were limited by small numbers of patients with cancer, limiting the ability to look for associations with specific cancer or treatment types.