User login

Gender equity, sexual harassment in health care

SAN FRANCISCO – Women in health care are second only to those in arts and entertainment in contacting* the TIME’S UP Legal Defense Fund, according to two founding members of TIME’S UP Healthcare, which was recently launched to address gender inequity and sexual harassment in medicine.

“As a psychiatrist who has had physicians as patients ... I’d heard this stuff, and I knew it existed,” said Jessica Gold, MD. But to hear it from people who had choked it down ... I understand what it’s like to be a pharma rep and be told that you have to look pretty or wear a thong to get a doctor to look at you.”

In this video, Dr. Gold and Kali D. Cyrus, MD, MPH, sat down at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association and discussed the goals of TIME’S UP Healthcare and the need to bring transgressions – mainly against women – out in the open. The group also wants to advocate for establishing meaningful standards and policies.

“I feel like [psychiatrists are] trained to look for these kinds of dynamics. We should be trained to intervene ... Dr. Cyrus said.

She wants to make sure that all women are equitably represented. We need “a procedure in place where people can voice their concerns.”

All of the group’s founding members are women, and men also need to participate as allies. “There are men who want to mentor women, Dr. Gold said. “We do need men to support us ... We also want to hear about their experiences,” Dr. Cyrus said.

Dr. Gold is assistant professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Cyrus is an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and offers consultation services for conflict management of issues related to identity differences.

*This story was updated 6/3/2019.

SAN FRANCISCO – Women in health care are second only to those in arts and entertainment in contacting* the TIME’S UP Legal Defense Fund, according to two founding members of TIME’S UP Healthcare, which was recently launched to address gender inequity and sexual harassment in medicine.

“As a psychiatrist who has had physicians as patients ... I’d heard this stuff, and I knew it existed,” said Jessica Gold, MD. But to hear it from people who had choked it down ... I understand what it’s like to be a pharma rep and be told that you have to look pretty or wear a thong to get a doctor to look at you.”

In this video, Dr. Gold and Kali D. Cyrus, MD, MPH, sat down at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association and discussed the goals of TIME’S UP Healthcare and the need to bring transgressions – mainly against women – out in the open. The group also wants to advocate for establishing meaningful standards and policies.

“I feel like [psychiatrists are] trained to look for these kinds of dynamics. We should be trained to intervene ... Dr. Cyrus said.

She wants to make sure that all women are equitably represented. We need “a procedure in place where people can voice their concerns.”

All of the group’s founding members are women, and men also need to participate as allies. “There are men who want to mentor women, Dr. Gold said. “We do need men to support us ... We also want to hear about their experiences,” Dr. Cyrus said.

Dr. Gold is assistant professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Cyrus is an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and offers consultation services for conflict management of issues related to identity differences.

*This story was updated 6/3/2019.

SAN FRANCISCO – Women in health care are second only to those in arts and entertainment in contacting* the TIME’S UP Legal Defense Fund, according to two founding members of TIME’S UP Healthcare, which was recently launched to address gender inequity and sexual harassment in medicine.

“As a psychiatrist who has had physicians as patients ... I’d heard this stuff, and I knew it existed,” said Jessica Gold, MD. But to hear it from people who had choked it down ... I understand what it’s like to be a pharma rep and be told that you have to look pretty or wear a thong to get a doctor to look at you.”

In this video, Dr. Gold and Kali D. Cyrus, MD, MPH, sat down at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association and discussed the goals of TIME’S UP Healthcare and the need to bring transgressions – mainly against women – out in the open. The group also wants to advocate for establishing meaningful standards and policies.

“I feel like [psychiatrists are] trained to look for these kinds of dynamics. We should be trained to intervene ... Dr. Cyrus said.

She wants to make sure that all women are equitably represented. We need “a procedure in place where people can voice their concerns.”

All of the group’s founding members are women, and men also need to participate as allies. “There are men who want to mentor women, Dr. Gold said. “We do need men to support us ... We also want to hear about their experiences,” Dr. Cyrus said.

Dr. Gold is assistant professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Cyrus is an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and offers consultation services for conflict management of issues related to identity differences.

*This story was updated 6/3/2019.

REPORTING FROM APA 2019

Consider patients’ perceptions of tardive dyskinesia

SAN FRANCISCO – Stanley N. Caroff, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

“You really need to ask the patient a lot of questions – and the family and the caregivers – about how much tardive dyskinesia affects their lives,” he said.

Those were some of the early results of RE-KINECT, an ongoing study of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder who were being treated with antipsychotic agents.

TD occurs in more than 25% of patients in outpatient practices who are exposed to dopamine receptor blockers. Symptoms can include involuntary movements of the tongue, hands, and feet; facial distortions; rapid eye blinking; and difficulty speaking. In some cases, the side effects resolve after patients stop taking the medications.

In this video, Dr. Caroff discussed the studies’ findings and their implications for everyday clinical practice. He also presented some of the early RE-KINECT findings in a poster at the meeting.

Dr. Caroff is professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He also is affiliated with the Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center in Philadelphia. He disclosed working as a consultant for and receiving research funding from Neurocrine Biosciences. He also is a consultant for DisperSol Technologies, Osmotica Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceutical.

SAN FRANCISCO – Stanley N. Caroff, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

“You really need to ask the patient a lot of questions – and the family and the caregivers – about how much tardive dyskinesia affects their lives,” he said.

Those were some of the early results of RE-KINECT, an ongoing study of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder who were being treated with antipsychotic agents.

TD occurs in more than 25% of patients in outpatient practices who are exposed to dopamine receptor blockers. Symptoms can include involuntary movements of the tongue, hands, and feet; facial distortions; rapid eye blinking; and difficulty speaking. In some cases, the side effects resolve after patients stop taking the medications.

In this video, Dr. Caroff discussed the studies’ findings and their implications for everyday clinical practice. He also presented some of the early RE-KINECT findings in a poster at the meeting.

Dr. Caroff is professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He also is affiliated with the Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center in Philadelphia. He disclosed working as a consultant for and receiving research funding from Neurocrine Biosciences. He also is a consultant for DisperSol Technologies, Osmotica Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceutical.

SAN FRANCISCO – Stanley N. Caroff, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

“You really need to ask the patient a lot of questions – and the family and the caregivers – about how much tardive dyskinesia affects their lives,” he said.

Those were some of the early results of RE-KINECT, an ongoing study of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder who were being treated with antipsychotic agents.

TD occurs in more than 25% of patients in outpatient practices who are exposed to dopamine receptor blockers. Symptoms can include involuntary movements of the tongue, hands, and feet; facial distortions; rapid eye blinking; and difficulty speaking. In some cases, the side effects resolve after patients stop taking the medications.

In this video, Dr. Caroff discussed the studies’ findings and their implications for everyday clinical practice. He also presented some of the early RE-KINECT findings in a poster at the meeting.

Dr. Caroff is professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He also is affiliated with the Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center in Philadelphia. He disclosed working as a consultant for and receiving research funding from Neurocrine Biosciences. He also is a consultant for DisperSol Technologies, Osmotica Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceutical.

REPORTING FROM APA 2019

Increasingly violent storms may strain mental health

SAN FRANCISCO – Longer and more powerful storms caused by climate change will put increasing pressure on mental health care. The unusually powerful 2017 hurricane season, highlighted by damage done to Puerto Rico by Hurricane Maria and to Houston by Hurricane Harvey, may serve as a harbinger of more intense storm seasons to come, according to James M. Shultz, PhD, director of the Center for Disaster and Extreme Event Preparedness at the University of Miami.

Overall, 2017 was something of a “perfect storm” season. “We’ve had predictions about what climate change would do to extreme storms. It was quite exceptional in bringing together all of the elements we have seen predicted by climate scientists,” Dr. Shultz said during a press conference at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Study coauthor Zelde Espinel, MD, MPH, also of the center at the university, presented the poster at the meeting.

Aside from greater intensity, climate change is causing a slowing of storms once they make landfall, which increases rainfall and the risks of floods. Nowhere was that more apparent than in Houston in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, where tens of thousands of spontaneous rescue efforts arose to rescue people trapped in their homes.

These storms put tremendous pressure on health care systems, as in Puerto Rico when Hurricane Maria knocked out electrical grids, some of which stayed down for 6 months or more. This kind of upheaval interrupts health care infrastructure, including psychiatric services, leaving vulnerable individuals at even greater risk.

Then there are the direct and indirect effects of storms on mental health. When air conditioning and fans are inoperative because of power outages, people get exposed to extreme and relentless heat. They may experience food and water shortages. In worst cases, they may be forced out of their homes on a temporary or even permanent basis. Dr. Shultz recounted research looking at victims of Hurricane Maria.

Researchers used standardized measures to assess both survivors who remained in Puerto Rico, and others who were forced to relocate, mostly to Florida. Sixty-six percent of those interviewed had clinically significant elevated symptoms of PTSD, major depression, or generalized anxiety. A study looking at people displaced from Puerto Rico and those who stayed also found high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in both samples, and rates were actually higher in those who were displaced to Florida, Dr. Shultz said (Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019 Feb;13[13]:24-7).

These effects will only worsen as climate change brings more and more powerful storms, and psychiatrists must be ready to help. The year 2017 “is just a snapshot. It may in fact be just a garden variety year when we look back later in this century.

Many countries most affected by climate change are poor in resources and may have few psychiatrists available in the first place. After a storm, infrastructure and the number of trained mental health professionals may further decline. That calls for outside assistance: “We’ve been talking about the possibility of bringing interpersonal psychotherapy (to affected areas) and to have lay personnel supervised by psychiatrists be able to deliver these sorts of interventions,” he said.

Dr. Shultz has no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Longer and more powerful storms caused by climate change will put increasing pressure on mental health care. The unusually powerful 2017 hurricane season, highlighted by damage done to Puerto Rico by Hurricane Maria and to Houston by Hurricane Harvey, may serve as a harbinger of more intense storm seasons to come, according to James M. Shultz, PhD, director of the Center for Disaster and Extreme Event Preparedness at the University of Miami.

Overall, 2017 was something of a “perfect storm” season. “We’ve had predictions about what climate change would do to extreme storms. It was quite exceptional in bringing together all of the elements we have seen predicted by climate scientists,” Dr. Shultz said during a press conference at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Study coauthor Zelde Espinel, MD, MPH, also of the center at the university, presented the poster at the meeting.

Aside from greater intensity, climate change is causing a slowing of storms once they make landfall, which increases rainfall and the risks of floods. Nowhere was that more apparent than in Houston in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, where tens of thousands of spontaneous rescue efforts arose to rescue people trapped in their homes.

These storms put tremendous pressure on health care systems, as in Puerto Rico when Hurricane Maria knocked out electrical grids, some of which stayed down for 6 months or more. This kind of upheaval interrupts health care infrastructure, including psychiatric services, leaving vulnerable individuals at even greater risk.

Then there are the direct and indirect effects of storms on mental health. When air conditioning and fans are inoperative because of power outages, people get exposed to extreme and relentless heat. They may experience food and water shortages. In worst cases, they may be forced out of their homes on a temporary or even permanent basis. Dr. Shultz recounted research looking at victims of Hurricane Maria.

Researchers used standardized measures to assess both survivors who remained in Puerto Rico, and others who were forced to relocate, mostly to Florida. Sixty-six percent of those interviewed had clinically significant elevated symptoms of PTSD, major depression, or generalized anxiety. A study looking at people displaced from Puerto Rico and those who stayed also found high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in both samples, and rates were actually higher in those who were displaced to Florida, Dr. Shultz said (Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019 Feb;13[13]:24-7).

These effects will only worsen as climate change brings more and more powerful storms, and psychiatrists must be ready to help. The year 2017 “is just a snapshot. It may in fact be just a garden variety year when we look back later in this century.

Many countries most affected by climate change are poor in resources and may have few psychiatrists available in the first place. After a storm, infrastructure and the number of trained mental health professionals may further decline. That calls for outside assistance: “We’ve been talking about the possibility of bringing interpersonal psychotherapy (to affected areas) and to have lay personnel supervised by psychiatrists be able to deliver these sorts of interventions,” he said.

Dr. Shultz has no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Longer and more powerful storms caused by climate change will put increasing pressure on mental health care. The unusually powerful 2017 hurricane season, highlighted by damage done to Puerto Rico by Hurricane Maria and to Houston by Hurricane Harvey, may serve as a harbinger of more intense storm seasons to come, according to James M. Shultz, PhD, director of the Center for Disaster and Extreme Event Preparedness at the University of Miami.

Overall, 2017 was something of a “perfect storm” season. “We’ve had predictions about what climate change would do to extreme storms. It was quite exceptional in bringing together all of the elements we have seen predicted by climate scientists,” Dr. Shultz said during a press conference at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Study coauthor Zelde Espinel, MD, MPH, also of the center at the university, presented the poster at the meeting.

Aside from greater intensity, climate change is causing a slowing of storms once they make landfall, which increases rainfall and the risks of floods. Nowhere was that more apparent than in Houston in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, where tens of thousands of spontaneous rescue efforts arose to rescue people trapped in their homes.

These storms put tremendous pressure on health care systems, as in Puerto Rico when Hurricane Maria knocked out electrical grids, some of which stayed down for 6 months or more. This kind of upheaval interrupts health care infrastructure, including psychiatric services, leaving vulnerable individuals at even greater risk.

Then there are the direct and indirect effects of storms on mental health. When air conditioning and fans are inoperative because of power outages, people get exposed to extreme and relentless heat. They may experience food and water shortages. In worst cases, they may be forced out of their homes on a temporary or even permanent basis. Dr. Shultz recounted research looking at victims of Hurricane Maria.

Researchers used standardized measures to assess both survivors who remained in Puerto Rico, and others who were forced to relocate, mostly to Florida. Sixty-six percent of those interviewed had clinically significant elevated symptoms of PTSD, major depression, or generalized anxiety. A study looking at people displaced from Puerto Rico and those who stayed also found high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in both samples, and rates were actually higher in those who were displaced to Florida, Dr. Shultz said (Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019 Feb;13[13]:24-7).

These effects will only worsen as climate change brings more and more powerful storms, and psychiatrists must be ready to help. The year 2017 “is just a snapshot. It may in fact be just a garden variety year when we look back later in this century.

Many countries most affected by climate change are poor in resources and may have few psychiatrists available in the first place. After a storm, infrastructure and the number of trained mental health professionals may further decline. That calls for outside assistance: “We’ve been talking about the possibility of bringing interpersonal psychotherapy (to affected areas) and to have lay personnel supervised by psychiatrists be able to deliver these sorts of interventions,” he said.

Dr. Shultz has no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM APA 2019

Ketamine tied to remission from suicidal ideation

Report of 235 cases deemed largest series to date on impact of infusions

SAN FRANCISCO – Serial ketamine infusions eliminated suicidal ideation in more than two-thirds of patients at a psychiatry office in Connecticut but at significantly higher doses than those recently approved for Janssen’s new esketamine nasal spray (Spravato).

The patients were treated by Lori V. Calabrese, MD, at Innovative Psychiatry, her private outpatient practice in South Windsor. She presented her first 235 IV ketamine cases at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting. It was likely the largest real-world series to date of ketamine infusions for treatment-resistant depression and suicidality.

The patients, 14-84 years old but mostly middle-aged, received six infusions over 2-3 weeks, starting at 0.5 mg/kg over 40-50 minutes, then titrated upward for dissociative effect to a maximum of 1.7 mg/kg. Subjects filled out the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) at baseline and before each infusion. Item nine – “thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way” – was used to gauge suicidality. That item has been validated as a predictor of suicide risk.

Among 144 patients (62%) who were markedly suicidal, ketamine infusions were tied to diminished ideation in 118 (82%) and eliminated ideation in 98 (68%). They were severely depressed at baseline; PHQ-9 scores fell in 127 (89%), and depression went into remission in 89 (62%). There were no suicide attempts, ED visits, or hospitalizations during treatment and at 4-week follow-up.

“Even if they had been suicidal for a long time, been hospitalized, and made suicide attempts, 68% had full remission of suicidality. This is a life-saving treatment, a breakthrough option for psychiatrists,” Dr. Calabrese said.

The results are “fabulous,” said Jaskaran Singh, MD, who said he was clinical leader of the esketamine program at Janssen.

“You prevented hospitalizations and saved lives,” Dr. Singh said. “This is a marvelous study that we should have done.”

Dr. Calabrese’s report, however, raises the question of whether the nasal spray will be potent enough to achieve the same results. She found that cessation of suicidal thoughts required an average dose of 0.75 mg/kg IV ketamine, which is higher than the 0.5 mg/kg used by many ketamine infusion programs in the United States. It’s also significantly higher than Spravato dosing. The spray was cleared by the Food and Drug Administration in March for use with an oral antidepressant for treatment-resistant depression. It was the subject of much buzz at the APA meeting.

Esketamine is approved in doses of 56 mg, which works out to almost 0.2 mg/kg, and 84 mg, which works out to less than 4 mg/kg. Dosing is twice weekly at first, then weekly or biweekly for maintenance.

When asked whether he thought those doses would be enough to prevent suicide, Dr. Singh said his company has finished two trials in suicidal patients and would present results later in 2019.

Dr. Calabrese, meanwhile, plans to incorporate intranasal esketamine into her practice, but will continue to offer ketamine infusions. “How can I not? I’ve seen how effective they are,” she said.

She charges $500 per session, $2 for the ketamine plus nursing and other costs. Insurance companies have sometimes covered it for patients with a history of psychiatric ED visits and hospitalizations, on the grounds that infusions will prevent future admissions. But patients have to fight for coverage – and feel well enough to do so.

That’s the main reason Dr. Calabrese plans to start offering Spravato; coverage will likely be less of a hassle for patients once Janssen works out the insurance issues. Spravato has been reported to cost about $600-$900 per treatment session.

She noted that response among her infusion patients was bimodal, with suicidal ideation eliminated in some patients after one infusion, but most of the rest needed three or more. “Don’t give up,” she said.

Infusion response correlated with suicidality and depression severity, with the sickest patients having the most benefit. Among 91 moderately depressed, nonsuicidal patients, just over half responded to the infusions, and depression went into remission in about a third.

Side effects were minimal, transient, and easily handled in the office. A little bit of IV midazolam calmed patients who got too anxious, and IV ondansetron (Zofran) helped those who got nauseous. Blood pressure can bump up a bit with ketamine, so Dr. Calabrese follows it closely.

The report had no external funding and Dr. Calabrese had no disclosures.

Report of 235 cases deemed largest series to date on impact of infusions

Report of 235 cases deemed largest series to date on impact of infusions

SAN FRANCISCO – Serial ketamine infusions eliminated suicidal ideation in more than two-thirds of patients at a psychiatry office in Connecticut but at significantly higher doses than those recently approved for Janssen’s new esketamine nasal spray (Spravato).

The patients were treated by Lori V. Calabrese, MD, at Innovative Psychiatry, her private outpatient practice in South Windsor. She presented her first 235 IV ketamine cases at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting. It was likely the largest real-world series to date of ketamine infusions for treatment-resistant depression and suicidality.

The patients, 14-84 years old but mostly middle-aged, received six infusions over 2-3 weeks, starting at 0.5 mg/kg over 40-50 minutes, then titrated upward for dissociative effect to a maximum of 1.7 mg/kg. Subjects filled out the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) at baseline and before each infusion. Item nine – “thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way” – was used to gauge suicidality. That item has been validated as a predictor of suicide risk.

Among 144 patients (62%) who were markedly suicidal, ketamine infusions were tied to diminished ideation in 118 (82%) and eliminated ideation in 98 (68%). They were severely depressed at baseline; PHQ-9 scores fell in 127 (89%), and depression went into remission in 89 (62%). There were no suicide attempts, ED visits, or hospitalizations during treatment and at 4-week follow-up.

“Even if they had been suicidal for a long time, been hospitalized, and made suicide attempts, 68% had full remission of suicidality. This is a life-saving treatment, a breakthrough option for psychiatrists,” Dr. Calabrese said.

The results are “fabulous,” said Jaskaran Singh, MD, who said he was clinical leader of the esketamine program at Janssen.

“You prevented hospitalizations and saved lives,” Dr. Singh said. “This is a marvelous study that we should have done.”

Dr. Calabrese’s report, however, raises the question of whether the nasal spray will be potent enough to achieve the same results. She found that cessation of suicidal thoughts required an average dose of 0.75 mg/kg IV ketamine, which is higher than the 0.5 mg/kg used by many ketamine infusion programs in the United States. It’s also significantly higher than Spravato dosing. The spray was cleared by the Food and Drug Administration in March for use with an oral antidepressant for treatment-resistant depression. It was the subject of much buzz at the APA meeting.

Esketamine is approved in doses of 56 mg, which works out to almost 0.2 mg/kg, and 84 mg, which works out to less than 4 mg/kg. Dosing is twice weekly at first, then weekly or biweekly for maintenance.

When asked whether he thought those doses would be enough to prevent suicide, Dr. Singh said his company has finished two trials in suicidal patients and would present results later in 2019.

Dr. Calabrese, meanwhile, plans to incorporate intranasal esketamine into her practice, but will continue to offer ketamine infusions. “How can I not? I’ve seen how effective they are,” she said.

She charges $500 per session, $2 for the ketamine plus nursing and other costs. Insurance companies have sometimes covered it for patients with a history of psychiatric ED visits and hospitalizations, on the grounds that infusions will prevent future admissions. But patients have to fight for coverage – and feel well enough to do so.

That’s the main reason Dr. Calabrese plans to start offering Spravato; coverage will likely be less of a hassle for patients once Janssen works out the insurance issues. Spravato has been reported to cost about $600-$900 per treatment session.

She noted that response among her infusion patients was bimodal, with suicidal ideation eliminated in some patients after one infusion, but most of the rest needed three or more. “Don’t give up,” she said.

Infusion response correlated with suicidality and depression severity, with the sickest patients having the most benefit. Among 91 moderately depressed, nonsuicidal patients, just over half responded to the infusions, and depression went into remission in about a third.

Side effects were minimal, transient, and easily handled in the office. A little bit of IV midazolam calmed patients who got too anxious, and IV ondansetron (Zofran) helped those who got nauseous. Blood pressure can bump up a bit with ketamine, so Dr. Calabrese follows it closely.

The report had no external funding and Dr. Calabrese had no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Serial ketamine infusions eliminated suicidal ideation in more than two-thirds of patients at a psychiatry office in Connecticut but at significantly higher doses than those recently approved for Janssen’s new esketamine nasal spray (Spravato).

The patients were treated by Lori V. Calabrese, MD, at Innovative Psychiatry, her private outpatient practice in South Windsor. She presented her first 235 IV ketamine cases at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting. It was likely the largest real-world series to date of ketamine infusions for treatment-resistant depression and suicidality.

The patients, 14-84 years old but mostly middle-aged, received six infusions over 2-3 weeks, starting at 0.5 mg/kg over 40-50 minutes, then titrated upward for dissociative effect to a maximum of 1.7 mg/kg. Subjects filled out the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) at baseline and before each infusion. Item nine – “thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way” – was used to gauge suicidality. That item has been validated as a predictor of suicide risk.

Among 144 patients (62%) who were markedly suicidal, ketamine infusions were tied to diminished ideation in 118 (82%) and eliminated ideation in 98 (68%). They were severely depressed at baseline; PHQ-9 scores fell in 127 (89%), and depression went into remission in 89 (62%). There were no suicide attempts, ED visits, or hospitalizations during treatment and at 4-week follow-up.

“Even if they had been suicidal for a long time, been hospitalized, and made suicide attempts, 68% had full remission of suicidality. This is a life-saving treatment, a breakthrough option for psychiatrists,” Dr. Calabrese said.

The results are “fabulous,” said Jaskaran Singh, MD, who said he was clinical leader of the esketamine program at Janssen.

“You prevented hospitalizations and saved lives,” Dr. Singh said. “This is a marvelous study that we should have done.”

Dr. Calabrese’s report, however, raises the question of whether the nasal spray will be potent enough to achieve the same results. She found that cessation of suicidal thoughts required an average dose of 0.75 mg/kg IV ketamine, which is higher than the 0.5 mg/kg used by many ketamine infusion programs in the United States. It’s also significantly higher than Spravato dosing. The spray was cleared by the Food and Drug Administration in March for use with an oral antidepressant for treatment-resistant depression. It was the subject of much buzz at the APA meeting.

Esketamine is approved in doses of 56 mg, which works out to almost 0.2 mg/kg, and 84 mg, which works out to less than 4 mg/kg. Dosing is twice weekly at first, then weekly or biweekly for maintenance.

When asked whether he thought those doses would be enough to prevent suicide, Dr. Singh said his company has finished two trials in suicidal patients and would present results later in 2019.

Dr. Calabrese, meanwhile, plans to incorporate intranasal esketamine into her practice, but will continue to offer ketamine infusions. “How can I not? I’ve seen how effective they are,” she said.

She charges $500 per session, $2 for the ketamine plus nursing and other costs. Insurance companies have sometimes covered it for patients with a history of psychiatric ED visits and hospitalizations, on the grounds that infusions will prevent future admissions. But patients have to fight for coverage – and feel well enough to do so.

That’s the main reason Dr. Calabrese plans to start offering Spravato; coverage will likely be less of a hassle for patients once Janssen works out the insurance issues. Spravato has been reported to cost about $600-$900 per treatment session.

She noted that response among her infusion patients was bimodal, with suicidal ideation eliminated in some patients after one infusion, but most of the rest needed three or more. “Don’t give up,” she said.

Infusion response correlated with suicidality and depression severity, with the sickest patients having the most benefit. Among 91 moderately depressed, nonsuicidal patients, just over half responded to the infusions, and depression went into remission in about a third.

Side effects were minimal, transient, and easily handled in the office. A little bit of IV midazolam calmed patients who got too anxious, and IV ondansetron (Zofran) helped those who got nauseous. Blood pressure can bump up a bit with ketamine, so Dr. Calabrese follows it closely.

The report had no external funding and Dr. Calabrese had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM APA 2019

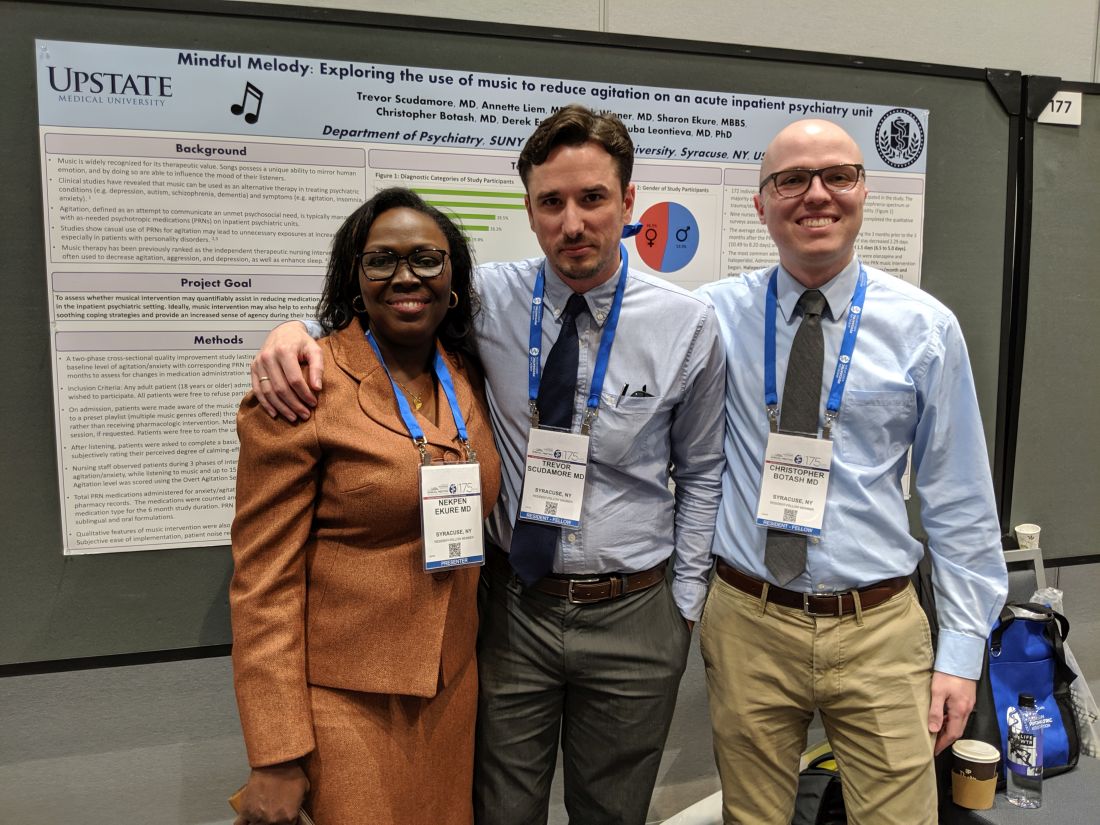

Music shows promise for inpatient agitation

SAN FRANCISCO – In a proof-of-concept study, music provided an alternative to oral psychotropic medication in calming agitated patients at an inpatient psychiatric facility. Music has been studied as a treatment for agitation in dementia patients but not so much in psychiatric patients, according to Trevor Scudamore, MD, who is a resident fellow at State University of New York, Syracuse.

“The other thing is that music has been more looked at in group therapy settings than as adjunct therapy, or as an option as an as-needed medication for agitation,” Dr. Scudamore said in an interview. He presented the study at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

When agitation arose, the program allowed patients to choose between an oral medication or music, which entailed a 30-minute session listening to a preset playlist using a wireless headphone. Playlist options included a variety of musical genres, and participants could sit in one place or roam around while listening.

Traditionally, agitated patients had the choice of an oral medication. If the patient refused and then escalated, they had to accept an intravenous medication. “Now there’s a choice between an oral medication and music, almost like a third layer in defusing agitation in the patient. If they refuse music, then they could go for oral medication, and then [IV medication]. They’re given a little bit more options. Maybe they don’t feel so confined, which is an interesting way of helping possibly defuse anxiety from a situation. That needs to be explored further,” Dr. Scudamore said.

The study had a two-phase, cross-sectional design. The first 3 months, the study included 71 patients, who were used to establish a baseline of agitation and psychotropic medication use. They introduced the music intervention during the second 3-month period, with 101 participants. After they listened to music, the patients completed a self-report form using the Likert scale, and nursing staff observed the patients status during the initial anxiety/agitation, while they listened to music, and 15 minutes after the listening session.

That need for commitment from nurses presented a challenge to implementation. They had to hand out headphones, keep track of them, and make sure they got the headphones back. “It is a lot more work than just giving 50 mg of hydroxyzine,” said coauthor Christopher Botash, MD, who also is a resident at the university.

Study participants had a range of psychiatric ills, including substance abuse (61%), depression (51%), psychosis (28%), trauma (26%), personality disorder (20%), and anxiety (17%).

As part of a preliminary report, the researchers presented data from surveys completed by nine nurses and 31 patients. The two most commonly prescribed antipsychotics saw a decrease in administrations, from 3.37 to 2.93/month for haloperidol, and from 3.83 to 2.73 administrations/month for olanzapine.

A total of 56% of the nursing staff stated that the music therapy program helped calm down the patients. Nurses who disagreed cited the tendency for patients to intrude at the nursing station asking for the music, though this improved as patients learned the routine. Ninety-six percent of the patients reported satisfaction with the experience.

It was challenging for the researchers to implement the study, since offering music was a break in the routine. “The staff really does rely a lot on the meds, so oftentimes we would have to say, ‘Hey, have you offered the music yet?’ It’s a bit of a culture change,” Dr. Botash said.

The study, which Dr. Scudamore and Dr. Botash coauthored with Nekpen S. Ekure, MD, did not receive external funding. Dr. Scudamore and Dr. Botash had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – In a proof-of-concept study, music provided an alternative to oral psychotropic medication in calming agitated patients at an inpatient psychiatric facility. Music has been studied as a treatment for agitation in dementia patients but not so much in psychiatric patients, according to Trevor Scudamore, MD, who is a resident fellow at State University of New York, Syracuse.

“The other thing is that music has been more looked at in group therapy settings than as adjunct therapy, or as an option as an as-needed medication for agitation,” Dr. Scudamore said in an interview. He presented the study at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

When agitation arose, the program allowed patients to choose between an oral medication or music, which entailed a 30-minute session listening to a preset playlist using a wireless headphone. Playlist options included a variety of musical genres, and participants could sit in one place or roam around while listening.

Traditionally, agitated patients had the choice of an oral medication. If the patient refused and then escalated, they had to accept an intravenous medication. “Now there’s a choice between an oral medication and music, almost like a third layer in defusing agitation in the patient. If they refuse music, then they could go for oral medication, and then [IV medication]. They’re given a little bit more options. Maybe they don’t feel so confined, which is an interesting way of helping possibly defuse anxiety from a situation. That needs to be explored further,” Dr. Scudamore said.

The study had a two-phase, cross-sectional design. The first 3 months, the study included 71 patients, who were used to establish a baseline of agitation and psychotropic medication use. They introduced the music intervention during the second 3-month period, with 101 participants. After they listened to music, the patients completed a self-report form using the Likert scale, and nursing staff observed the patients status during the initial anxiety/agitation, while they listened to music, and 15 minutes after the listening session.

That need for commitment from nurses presented a challenge to implementation. They had to hand out headphones, keep track of them, and make sure they got the headphones back. “It is a lot more work than just giving 50 mg of hydroxyzine,” said coauthor Christopher Botash, MD, who also is a resident at the university.

Study participants had a range of psychiatric ills, including substance abuse (61%), depression (51%), psychosis (28%), trauma (26%), personality disorder (20%), and anxiety (17%).

As part of a preliminary report, the researchers presented data from surveys completed by nine nurses and 31 patients. The two most commonly prescribed antipsychotics saw a decrease in administrations, from 3.37 to 2.93/month for haloperidol, and from 3.83 to 2.73 administrations/month for olanzapine.

A total of 56% of the nursing staff stated that the music therapy program helped calm down the patients. Nurses who disagreed cited the tendency for patients to intrude at the nursing station asking for the music, though this improved as patients learned the routine. Ninety-six percent of the patients reported satisfaction with the experience.

It was challenging for the researchers to implement the study, since offering music was a break in the routine. “The staff really does rely a lot on the meds, so oftentimes we would have to say, ‘Hey, have you offered the music yet?’ It’s a bit of a culture change,” Dr. Botash said.

The study, which Dr. Scudamore and Dr. Botash coauthored with Nekpen S. Ekure, MD, did not receive external funding. Dr. Scudamore and Dr. Botash had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – In a proof-of-concept study, music provided an alternative to oral psychotropic medication in calming agitated patients at an inpatient psychiatric facility. Music has been studied as a treatment for agitation in dementia patients but not so much in psychiatric patients, according to Trevor Scudamore, MD, who is a resident fellow at State University of New York, Syracuse.

“The other thing is that music has been more looked at in group therapy settings than as adjunct therapy, or as an option as an as-needed medication for agitation,” Dr. Scudamore said in an interview. He presented the study at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

When agitation arose, the program allowed patients to choose between an oral medication or music, which entailed a 30-minute session listening to a preset playlist using a wireless headphone. Playlist options included a variety of musical genres, and participants could sit in one place or roam around while listening.

Traditionally, agitated patients had the choice of an oral medication. If the patient refused and then escalated, they had to accept an intravenous medication. “Now there’s a choice between an oral medication and music, almost like a third layer in defusing agitation in the patient. If they refuse music, then they could go for oral medication, and then [IV medication]. They’re given a little bit more options. Maybe they don’t feel so confined, which is an interesting way of helping possibly defuse anxiety from a situation. That needs to be explored further,” Dr. Scudamore said.

The study had a two-phase, cross-sectional design. The first 3 months, the study included 71 patients, who were used to establish a baseline of agitation and psychotropic medication use. They introduced the music intervention during the second 3-month period, with 101 participants. After they listened to music, the patients completed a self-report form using the Likert scale, and nursing staff observed the patients status during the initial anxiety/agitation, while they listened to music, and 15 minutes after the listening session.

That need for commitment from nurses presented a challenge to implementation. They had to hand out headphones, keep track of them, and make sure they got the headphones back. “It is a lot more work than just giving 50 mg of hydroxyzine,” said coauthor Christopher Botash, MD, who also is a resident at the university.

Study participants had a range of psychiatric ills, including substance abuse (61%), depression (51%), psychosis (28%), trauma (26%), personality disorder (20%), and anxiety (17%).

As part of a preliminary report, the researchers presented data from surveys completed by nine nurses and 31 patients. The two most commonly prescribed antipsychotics saw a decrease in administrations, from 3.37 to 2.93/month for haloperidol, and from 3.83 to 2.73 administrations/month for olanzapine.

A total of 56% of the nursing staff stated that the music therapy program helped calm down the patients. Nurses who disagreed cited the tendency for patients to intrude at the nursing station asking for the music, though this improved as patients learned the routine. Ninety-six percent of the patients reported satisfaction with the experience.

It was challenging for the researchers to implement the study, since offering music was a break in the routine. “The staff really does rely a lot on the meds, so oftentimes we would have to say, ‘Hey, have you offered the music yet?’ It’s a bit of a culture change,” Dr. Botash said.

The study, which Dr. Scudamore and Dr. Botash coauthored with Nekpen S. Ekure, MD, did not receive external funding. Dr. Scudamore and Dr. Botash had no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM APA 2019

Questions remain as marijuana enters clinic use

SAN FRANCISCO – Medical marijuana skipped the usual phased testing of pharmaceuticals, so questions abound about how to counsel patients as legalization rolls out across the country, speakers said at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting.

Drug interactions are an issue but remain under the radar. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) are inhibitors of cytochrome P450, specifically the CYP2C enzyme and CYP3A liver enzymes, which means possible interactions with drug classes such as antidepressants and antipsychotics might come into play.

Concomitant use could affect, or be affected by, fluoxetine, clozapine, duloxetine, and olanzapine, among other medications. One case study suggested that warfarin doses should be reduced by 30% in a patient who had started with a liquid formulation of CBD for managing epilepsy (Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019 Jan;124[1]:28-31).

At this point, it’s “not clear what the clinic implications are,” but “it’s not unreasonable to consider that your patients’ response to their psychiatric medications might change based on the introduction of cannabinoids,” said Arthur Williams, MD, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, and one of many researchers playing catch-up as marijuana and its derivatives enter the clinic.

Another question is what, exactly, is a standard dose?

Dosing mostly has been a question of THC, the psychoactive component of marijuana. Washington state and Colorado opted for 10-mg THC when those jurisdictions legalized recreational use; Oregon chose 5 mg. Both are in line with Food and Drug Administration formulations already on the market, including dronabinol (Marinol), a synthetic THC approved in 2.5-mg, 5-mg, and 10-mg doses for AIDS wasting, and chemotherapy nausea and vomiting.

A typical .7-g joint of 8% THC delivers about 5 mg or so, but newer strains range up to 20% THC, and could deliver over 13 mg per joint; occasional users, meanwhile, feel high from just 2-3 mg.

The ratio of THC to CBD matters, as well. Generally, “whole plant marijuana on the black market is much higher in THC and much lower in CBD,” Dr. Williams said. CBD is thought to deliver most of the medical benefits of marijuana.

It’s best to ask people what they’re using, and to counsel new users – especially the elderly – to start low and go slow. But keep in mind that many medical users have years of recreational use and have built up tolerance, he said.

Vaping is not a bad idea for those interested. It heats the plant material to high enough temperatures to release cannabinoids but without combusting. It’s a much more efficient THC delivery system than smoking, and there’s no smoke in the lungs. Vape patients often feel they can titrate their dose exactly.

Edibles are another matter. It can take hours for them to hit. Although THC levels do not spike with edibles as they do when the substance is inhaled, the effects last longer. A lot depends on how much food is in the gut.

The risk with edibles is that people may keep popping gummy bears and brownies because they don’t feel anything but end up overdosing. Children might be tempted by the treats, too, and for those under 4 years old, overdose can lead to fatal encephalopathic comas, “something we never really saw until edibles came around,” Dr. Williams said.

With edibles, “you have no idea what’s actually in the product.” Labels can be “inaccurate by an order of magnitude. Patients should be cautioned about that,” he said.

Pregnant and breastfeeding women, especially, should be warned away from marijuana. Some of the literature suggests a link between exposure to marijuana and preterm birth – in addition to early psychosis in vulnerable children.

Dr. Williams had no relevant disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Medical marijuana skipped the usual phased testing of pharmaceuticals, so questions abound about how to counsel patients as legalization rolls out across the country, speakers said at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting.

Drug interactions are an issue but remain under the radar. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) are inhibitors of cytochrome P450, specifically the CYP2C enzyme and CYP3A liver enzymes, which means possible interactions with drug classes such as antidepressants and antipsychotics might come into play.

Concomitant use could affect, or be affected by, fluoxetine, clozapine, duloxetine, and olanzapine, among other medications. One case study suggested that warfarin doses should be reduced by 30% in a patient who had started with a liquid formulation of CBD for managing epilepsy (Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019 Jan;124[1]:28-31).

At this point, it’s “not clear what the clinic implications are,” but “it’s not unreasonable to consider that your patients’ response to their psychiatric medications might change based on the introduction of cannabinoids,” said Arthur Williams, MD, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, and one of many researchers playing catch-up as marijuana and its derivatives enter the clinic.

Another question is what, exactly, is a standard dose?

Dosing mostly has been a question of THC, the psychoactive component of marijuana. Washington state and Colorado opted for 10-mg THC when those jurisdictions legalized recreational use; Oregon chose 5 mg. Both are in line with Food and Drug Administration formulations already on the market, including dronabinol (Marinol), a synthetic THC approved in 2.5-mg, 5-mg, and 10-mg doses for AIDS wasting, and chemotherapy nausea and vomiting.

A typical .7-g joint of 8% THC delivers about 5 mg or so, but newer strains range up to 20% THC, and could deliver over 13 mg per joint; occasional users, meanwhile, feel high from just 2-3 mg.

The ratio of THC to CBD matters, as well. Generally, “whole plant marijuana on the black market is much higher in THC and much lower in CBD,” Dr. Williams said. CBD is thought to deliver most of the medical benefits of marijuana.

It’s best to ask people what they’re using, and to counsel new users – especially the elderly – to start low and go slow. But keep in mind that many medical users have years of recreational use and have built up tolerance, he said.

Vaping is not a bad idea for those interested. It heats the plant material to high enough temperatures to release cannabinoids but without combusting. It’s a much more efficient THC delivery system than smoking, and there’s no smoke in the lungs. Vape patients often feel they can titrate their dose exactly.

Edibles are another matter. It can take hours for them to hit. Although THC levels do not spike with edibles as they do when the substance is inhaled, the effects last longer. A lot depends on how much food is in the gut.

The risk with edibles is that people may keep popping gummy bears and brownies because they don’t feel anything but end up overdosing. Children might be tempted by the treats, too, and for those under 4 years old, overdose can lead to fatal encephalopathic comas, “something we never really saw until edibles came around,” Dr. Williams said.

With edibles, “you have no idea what’s actually in the product.” Labels can be “inaccurate by an order of magnitude. Patients should be cautioned about that,” he said.

Pregnant and breastfeeding women, especially, should be warned away from marijuana. Some of the literature suggests a link between exposure to marijuana and preterm birth – in addition to early psychosis in vulnerable children.

Dr. Williams had no relevant disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Medical marijuana skipped the usual phased testing of pharmaceuticals, so questions abound about how to counsel patients as legalization rolls out across the country, speakers said at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting.

Drug interactions are an issue but remain under the radar. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) are inhibitors of cytochrome P450, specifically the CYP2C enzyme and CYP3A liver enzymes, which means possible interactions with drug classes such as antidepressants and antipsychotics might come into play.

Concomitant use could affect, or be affected by, fluoxetine, clozapine, duloxetine, and olanzapine, among other medications. One case study suggested that warfarin doses should be reduced by 30% in a patient who had started with a liquid formulation of CBD for managing epilepsy (Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019 Jan;124[1]:28-31).

At this point, it’s “not clear what the clinic implications are,” but “it’s not unreasonable to consider that your patients’ response to their psychiatric medications might change based on the introduction of cannabinoids,” said Arthur Williams, MD, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, and one of many researchers playing catch-up as marijuana and its derivatives enter the clinic.

Another question is what, exactly, is a standard dose?

Dosing mostly has been a question of THC, the psychoactive component of marijuana. Washington state and Colorado opted for 10-mg THC when those jurisdictions legalized recreational use; Oregon chose 5 mg. Both are in line with Food and Drug Administration formulations already on the market, including dronabinol (Marinol), a synthetic THC approved in 2.5-mg, 5-mg, and 10-mg doses for AIDS wasting, and chemotherapy nausea and vomiting.

A typical .7-g joint of 8% THC delivers about 5 mg or so, but newer strains range up to 20% THC, and could deliver over 13 mg per joint; occasional users, meanwhile, feel high from just 2-3 mg.

The ratio of THC to CBD matters, as well. Generally, “whole plant marijuana on the black market is much higher in THC and much lower in CBD,” Dr. Williams said. CBD is thought to deliver most of the medical benefits of marijuana.

It’s best to ask people what they’re using, and to counsel new users – especially the elderly – to start low and go slow. But keep in mind that many medical users have years of recreational use and have built up tolerance, he said.

Vaping is not a bad idea for those interested. It heats the plant material to high enough temperatures to release cannabinoids but without combusting. It’s a much more efficient THC delivery system than smoking, and there’s no smoke in the lungs. Vape patients often feel they can titrate their dose exactly.

Edibles are another matter. It can take hours for them to hit. Although THC levels do not spike with edibles as they do when the substance is inhaled, the effects last longer. A lot depends on how much food is in the gut.

The risk with edibles is that people may keep popping gummy bears and brownies because they don’t feel anything but end up overdosing. Children might be tempted by the treats, too, and for those under 4 years old, overdose can lead to fatal encephalopathic comas, “something we never really saw until edibles came around,” Dr. Williams said.

With edibles, “you have no idea what’s actually in the product.” Labels can be “inaccurate by an order of magnitude. Patients should be cautioned about that,” he said.

Pregnant and breastfeeding women, especially, should be warned away from marijuana. Some of the literature suggests a link between exposure to marijuana and preterm birth – in addition to early psychosis in vulnerable children.

Dr. Williams had no relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM APA 2019

Synthetic drugs pose regulatory, diagnostic challenges

SAN FRANCISCO – Designer drugs, especially synthetic opioids and cannabinoids, are presenting increasing challenges to psychiatrists treating patients with overdoses or psychiatric adverse effects. In 2017, synthetic opioids caused more than 28,000 deaths in the United States, more than any other type. Some of these drugs are technically legal, because their modified chemical structures aren’t covered as legal definitions struggle to keep up with street drug identities.

... people are using drugs and they don’t even know what they’re using,” Vanessa Torres-Llenza, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. Dr. Torres-Llenza moderated a session on synthetic opioids at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Of particular concern is the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which has a potency about 50 times that of heroin, and 100 times that of morphine. It is a legal pharmaceutical drug for use in severe pain, but it can be made illicitly, and it is frequently mixed with heroin or cocaine and put into counterfeit pills. The user often is not even aware of its presence. Another derivative, carfentanil, is even more dangerous. Used as a large-animal tranquilizer, and illegal for human use, carfentanil is about 100 times more potent than fentanyl.

These developments may require reconsideration of treatment using the opioid antagonist naloxone and similar drugs. The current guidance for naloxone is a 0.4- to 2-mg dose, followed by repeat dose at 2- to 3-minute intervals as needed. Considering the increasing presence of more potent drugs, “there may not be time to wait,” Dr. Torres-Llenza said.

Another concern is illicit manufacturing: By making even slight modifications to legal drugs, illegal operations can stay a step ahead of regulators because these derivatives are completely legal until legislation is passed to ban them. Estimates peg the number of such new derivatives at about 250 per year.

The recent history of the Food Drug Administration’s regulation of synthetic opioids, presented during the session by Gowri Ramachandran, MD, a resident at George Washington University, illustrates the challenges. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 assigned every regulated drug into one of five classes based on medical use, and potential for abuse and dependence. Schedule I substances are flagged for a high potential of abuse, having no medical use in the United States, and a lack of accepted safety data for use under medical supervision. Schedule II substances have accepted medical uses.

In 2012, the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act amended the earlier legislation, declaring that any chemical or related derivative with cannabimimetic properties, as well as some other hallucinogenic molecules and their close relatives, were included as schedule I controlled substances.

The amended legislation also extended the potential length of temporary schedule I status, from 1 year with a 6-month extension, to 2 years with a 1-year extension, to give regulators more time to catch up with both legal and illegal synthetic changes to determine if a drug should be schedule I or II.

A recent example of this problem is bath salts, which are far more powerful, synthetic versions of a stimulant derived from the khat plant that is grown in East Africa and southern Arabia. Bath salts can produce hallucinogenic and euphoric effects similar to methamphetamine and ecstasy, but they are readily available online and in retail stores, labeled as “not for human use” and marketed as “bath salts,” “plant food,” “jewelry cleaner,” or “phone screen cleaner.”

Another concern is synthetic cannabinoids, which resemble the 100 or so cannabinoids found in marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and cannabidiol (CBD) being the most well-known examples. These began to appear in recreational use in 2005, representing legal forms of marijuana and sold with names like K2, Spice, and Kronic. They are sold in tobacco shops, again labeled “not for human consumption,” trumpeted instead as a “harmless incense blend” or “natural herbs.” Manufacture and content of these derivatives are completely unregulated, according to Dr. Ramachandran.

Like other drug classes, synthetic cannabinoids – many related to THC – have been structurally altered in recent years, posing challenges to regulation and even detection. This is especially concerning because a synthetic cannabinoid product could contain a potpourri of other drugs such as opioids or herbs, leading to unpredictable effects. It’s also nearly impossible to identify everything in a patient’s system, Dr. Torrez-Llenza said.

That makes diagnosis challenging given that synthetic cannabinoids can cause a wide range of symptoms, commonly violence, agitation, panic attacks, hallucinations, hyperglycemia, hyperkalemia, and tachycardia.

Synthetic cannabinoids usually do not contain CBD, which has some antipsychotic and anxiolytic effects. Instead they are generally derived from THC, which is associated with psychosis, and they are 40-660 times more potent than natural THC. This suggests that synthetic versions may pose a greater psychosis risk than natural cannabis. However, only case reports have examined the existence of an association between synthetic cannabinoids and psychosis, and it is difficult to distinguish a toxic syndrome from exacerbation of a previous prodromal syndrome, or new-onset illness.

Acute reactions can occur within minutes of use and last 2-5 hours or more. But this is all very unpredictable as it depends on the specific mixture used.

In the emergency department, agitation, aggression, and impulsive behaviors may signal exposure to synthetic cannabinoids. Most patients can be treated in the ED with antipsychotics or benzodiazepines to manage symptoms. There could be regional toxidromes that arise from local distribution of specific synthetic cannabinoid combinations.

While testing for synthetic cannabinoids remains challenging, Quest Diagnostics has a urine-based panel that includes them, and the company says it is working with information from the National Forensic Laboratory Information System, the Drug Enforcement Agency, industry sources, and the scientific literature to periodically update its standard panel.

Dr. Torres-Llenza had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Designer drugs, especially synthetic opioids and cannabinoids, are presenting increasing challenges to psychiatrists treating patients with overdoses or psychiatric adverse effects. In 2017, synthetic opioids caused more than 28,000 deaths in the United States, more than any other type. Some of these drugs are technically legal, because their modified chemical structures aren’t covered as legal definitions struggle to keep up with street drug identities.

... people are using drugs and they don’t even know what they’re using,” Vanessa Torres-Llenza, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. Dr. Torres-Llenza moderated a session on synthetic opioids at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Of particular concern is the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which has a potency about 50 times that of heroin, and 100 times that of morphine. It is a legal pharmaceutical drug for use in severe pain, but it can be made illicitly, and it is frequently mixed with heroin or cocaine and put into counterfeit pills. The user often is not even aware of its presence. Another derivative, carfentanil, is even more dangerous. Used as a large-animal tranquilizer, and illegal for human use, carfentanil is about 100 times more potent than fentanyl.

These developments may require reconsideration of treatment using the opioid antagonist naloxone and similar drugs. The current guidance for naloxone is a 0.4- to 2-mg dose, followed by repeat dose at 2- to 3-minute intervals as needed. Considering the increasing presence of more potent drugs, “there may not be time to wait,” Dr. Torres-Llenza said.

Another concern is illicit manufacturing: By making even slight modifications to legal drugs, illegal operations can stay a step ahead of regulators because these derivatives are completely legal until legislation is passed to ban them. Estimates peg the number of such new derivatives at about 250 per year.

The recent history of the Food Drug Administration’s regulation of synthetic opioids, presented during the session by Gowri Ramachandran, MD, a resident at George Washington University, illustrates the challenges. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 assigned every regulated drug into one of five classes based on medical use, and potential for abuse and dependence. Schedule I substances are flagged for a high potential of abuse, having no medical use in the United States, and a lack of accepted safety data for use under medical supervision. Schedule II substances have accepted medical uses.

In 2012, the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act amended the earlier legislation, declaring that any chemical or related derivative with cannabimimetic properties, as well as some other hallucinogenic molecules and their close relatives, were included as schedule I controlled substances.

The amended legislation also extended the potential length of temporary schedule I status, from 1 year with a 6-month extension, to 2 years with a 1-year extension, to give regulators more time to catch up with both legal and illegal synthetic changes to determine if a drug should be schedule I or II.

A recent example of this problem is bath salts, which are far more powerful, synthetic versions of a stimulant derived from the khat plant that is grown in East Africa and southern Arabia. Bath salts can produce hallucinogenic and euphoric effects similar to methamphetamine and ecstasy, but they are readily available online and in retail stores, labeled as “not for human use” and marketed as “bath salts,” “plant food,” “jewelry cleaner,” or “phone screen cleaner.”

Another concern is synthetic cannabinoids, which resemble the 100 or so cannabinoids found in marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and cannabidiol (CBD) being the most well-known examples. These began to appear in recreational use in 2005, representing legal forms of marijuana and sold with names like K2, Spice, and Kronic. They are sold in tobacco shops, again labeled “not for human consumption,” trumpeted instead as a “harmless incense blend” or “natural herbs.” Manufacture and content of these derivatives are completely unregulated, according to Dr. Ramachandran.

Like other drug classes, synthetic cannabinoids – many related to THC – have been structurally altered in recent years, posing challenges to regulation and even detection. This is especially concerning because a synthetic cannabinoid product could contain a potpourri of other drugs such as opioids or herbs, leading to unpredictable effects. It’s also nearly impossible to identify everything in a patient’s system, Dr. Torrez-Llenza said.

That makes diagnosis challenging given that synthetic cannabinoids can cause a wide range of symptoms, commonly violence, agitation, panic attacks, hallucinations, hyperglycemia, hyperkalemia, and tachycardia.

Synthetic cannabinoids usually do not contain CBD, which has some antipsychotic and anxiolytic effects. Instead they are generally derived from THC, which is associated with psychosis, and they are 40-660 times more potent than natural THC. This suggests that synthetic versions may pose a greater psychosis risk than natural cannabis. However, only case reports have examined the existence of an association between synthetic cannabinoids and psychosis, and it is difficult to distinguish a toxic syndrome from exacerbation of a previous prodromal syndrome, or new-onset illness.

Acute reactions can occur within minutes of use and last 2-5 hours or more. But this is all very unpredictable as it depends on the specific mixture used.

In the emergency department, agitation, aggression, and impulsive behaviors may signal exposure to synthetic cannabinoids. Most patients can be treated in the ED with antipsychotics or benzodiazepines to manage symptoms. There could be regional toxidromes that arise from local distribution of specific synthetic cannabinoid combinations.

While testing for synthetic cannabinoids remains challenging, Quest Diagnostics has a urine-based panel that includes them, and the company says it is working with information from the National Forensic Laboratory Information System, the Drug Enforcement Agency, industry sources, and the scientific literature to periodically update its standard panel.

Dr. Torres-Llenza had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Designer drugs, especially synthetic opioids and cannabinoids, are presenting increasing challenges to psychiatrists treating patients with overdoses or psychiatric adverse effects. In 2017, synthetic opioids caused more than 28,000 deaths in the United States, more than any other type. Some of these drugs are technically legal, because their modified chemical structures aren’t covered as legal definitions struggle to keep up with street drug identities.

... people are using drugs and they don’t even know what they’re using,” Vanessa Torres-Llenza, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. Dr. Torres-Llenza moderated a session on synthetic opioids at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Of particular concern is the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which has a potency about 50 times that of heroin, and 100 times that of morphine. It is a legal pharmaceutical drug for use in severe pain, but it can be made illicitly, and it is frequently mixed with heroin or cocaine and put into counterfeit pills. The user often is not even aware of its presence. Another derivative, carfentanil, is even more dangerous. Used as a large-animal tranquilizer, and illegal for human use, carfentanil is about 100 times more potent than fentanyl.

These developments may require reconsideration of treatment using the opioid antagonist naloxone and similar drugs. The current guidance for naloxone is a 0.4- to 2-mg dose, followed by repeat dose at 2- to 3-minute intervals as needed. Considering the increasing presence of more potent drugs, “there may not be time to wait,” Dr. Torres-Llenza said.

Another concern is illicit manufacturing: By making even slight modifications to legal drugs, illegal operations can stay a step ahead of regulators because these derivatives are completely legal until legislation is passed to ban them. Estimates peg the number of such new derivatives at about 250 per year.

The recent history of the Food Drug Administration’s regulation of synthetic opioids, presented during the session by Gowri Ramachandran, MD, a resident at George Washington University, illustrates the challenges. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 assigned every regulated drug into one of five classes based on medical use, and potential for abuse and dependence. Schedule I substances are flagged for a high potential of abuse, having no medical use in the United States, and a lack of accepted safety data for use under medical supervision. Schedule II substances have accepted medical uses.

In 2012, the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act amended the earlier legislation, declaring that any chemical or related derivative with cannabimimetic properties, as well as some other hallucinogenic molecules and their close relatives, were included as schedule I controlled substances.

The amended legislation also extended the potential length of temporary schedule I status, from 1 year with a 6-month extension, to 2 years with a 1-year extension, to give regulators more time to catch up with both legal and illegal synthetic changes to determine if a drug should be schedule I or II.

A recent example of this problem is bath salts, which are far more powerful, synthetic versions of a stimulant derived from the khat plant that is grown in East Africa and southern Arabia. Bath salts can produce hallucinogenic and euphoric effects similar to methamphetamine and ecstasy, but they are readily available online and in retail stores, labeled as “not for human use” and marketed as “bath salts,” “plant food,” “jewelry cleaner,” or “phone screen cleaner.”

Another concern is synthetic cannabinoids, which resemble the 100 or so cannabinoids found in marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and cannabidiol (CBD) being the most well-known examples. These began to appear in recreational use in 2005, representing legal forms of marijuana and sold with names like K2, Spice, and Kronic. They are sold in tobacco shops, again labeled “not for human consumption,” trumpeted instead as a “harmless incense blend” or “natural herbs.” Manufacture and content of these derivatives are completely unregulated, according to Dr. Ramachandran.

Like other drug classes, synthetic cannabinoids – many related to THC – have been structurally altered in recent years, posing challenges to regulation and even detection. This is especially concerning because a synthetic cannabinoid product could contain a potpourri of other drugs such as opioids or herbs, leading to unpredictable effects. It’s also nearly impossible to identify everything in a patient’s system, Dr. Torrez-Llenza said.

That makes diagnosis challenging given that synthetic cannabinoids can cause a wide range of symptoms, commonly violence, agitation, panic attacks, hallucinations, hyperglycemia, hyperkalemia, and tachycardia.

Synthetic cannabinoids usually do not contain CBD, which has some antipsychotic and anxiolytic effects. Instead they are generally derived from THC, which is associated with psychosis, and they are 40-660 times more potent than natural THC. This suggests that synthetic versions may pose a greater psychosis risk than natural cannabis. However, only case reports have examined the existence of an association between synthetic cannabinoids and psychosis, and it is difficult to distinguish a toxic syndrome from exacerbation of a previous prodromal syndrome, or new-onset illness.

Acute reactions can occur within minutes of use and last 2-5 hours or more. But this is all very unpredictable as it depends on the specific mixture used.

In the emergency department, agitation, aggression, and impulsive behaviors may signal exposure to synthetic cannabinoids. Most patients can be treated in the ED with antipsychotics or benzodiazepines to manage symptoms. There could be regional toxidromes that arise from local distribution of specific synthetic cannabinoid combinations.

While testing for synthetic cannabinoids remains challenging, Quest Diagnostics has a urine-based panel that includes them, and the company says it is working with information from the National Forensic Laboratory Information System, the Drug Enforcement Agency, industry sources, and the scientific literature to periodically update its standard panel.

Dr. Torres-Llenza had no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM APA 2019

For borderline personality disorder, less may be more

SAN FRANCISCO – Borderline personality disorder is often treated with long-running psychotherapy, but this could be a disservice to patients. Instead, stepped-care models may offer more benefit in a shorter period of time, conserving resources and potentially expanding the reach of therapeutic interventions.

“There is this legacy of psychoanalysis, this idea that if you’ve had a condition for 20 years, it’s going to take 20 years of therapy to get rid of it – which is not true,” Joel Paris, MD, said in an interview. Dr. Paris moderated a session on stepped-care interventions for borderline personality disorder at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

He also pointed out that psychoanalysis can prove self-sustaining: “There’s something to talk about, so it can go on and if there’s money to pay for the service, why stop?”

But psychoanalysis can have diminishing returns, and that in turn can strain resources. “Some people won’t get better or won’t go beyond a certain point. You help them to a certain extent, and then you have to be able to say, ‘That’s enough; stop there. If you get in to bad trouble, you can always come back,’ ” said Dr. Paris, professor of psychiatry at McGill University, Montreal.

That realization has led Dr. McGill to introduce a stepped-care model, which has provided a 12-week program for 15 years. Dr. Paris presented a retrospective look at the program, including 479 patients who received individual and group therapy. The dropout rate was high at 30%, but only 12% of patients returned asking for more therapy. A total of 145 patients deemed to be more chronic or who did not respond to the short-term program had the option of completing additional individual or group therapy over a period of 6-24 months.

“ There are also dropouts; maybe a quarter will not complete the program,” Dr. Paris said. “But that means 75% do, and most of them get better. There’s also good evidence that short therapy can help many people with substance abuse.”

Lois W. Choi-Kain, MD, assistant professor psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, presented evidence from several studies showing that shorter- and long-term courses of dialectical behavior therapy led to similar improvements, but that brief courses were associated with more rapid improvement. The short course consisted of weekly 1-hour individual sessions, while the longer course involved weekly 2-hour group sessions. The individual approach was associated with an 89% faster improvement in symptoms in the first 3 months (P less than .0001).