User login

Cannabinoids being studied for a variety of dermatologic conditions

.

“When you walk into places like CVS or Walgreens, you see lots of displays for CBD creams and oils,” Todd S. Anhalt, MD, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “The problem is, we don’t know what’s in them or who made them or how good they are. That’s going to be a problem for a while.”

According to Dr. Anhalt, clinical professor emeritus of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, there are about 140 active cannabinoid compounds in cannabis, but the most important ones are THC and cannabidiol (CBD). There are three types of cannabinoids, based on where the cannabidiol is produced: endocannabinoids, which are produced in the human body; phytocannabinoids, which are derived from plants such as marijuana and hemp; and synthetic cannabinoids, which are derived in labs.

Dr. Anhalt described the endocannabinoid system as a conserved network of molecular signaling made of several components: signaling molecules (endocannabinoids), endocannabinoid receptors (CB-1 and CB-2), enzymes, and transporters. There is also overlap between cannabinoids and terpenes, which are responsible for flavor and aroma in plants and marijuana and can enhance the effects of CBD.

“For the most part, CB-1 receptors are in the central nervous system and CB-2 [receptors] are mostly in the periphery,” including the skin and digestive system, said Dr. Anhalt, who practices at the California Skin Institute in Los Altos, Calif. “This is interesting because one of the main conditions I recommend cannabidiol for is in patients with peripheral neuropathy, despite the fact they may be on all sorts of medications such as Neurontin and Lyrica or tricyclic antidepressants. Sometimes they don’t get much relief from those. I have had many patients tell me that they have had reduction of pain and increased functionality using the CBD creams.” CB-2 receptors, he noted, are located in keratinocytes, sensory receptors, sweat glands, fibroblasts, Langerhans cells, melanocytes, and sebaceous glands.

Recent research shows that the endocannabinoid system is involved in modulation of the CNS and in immune function, particularly skin homeostasis and barrier function. “We know that barrier function can be affected by the generation of oxidative species,” he said. “The stress that it causes can decrease barrier function and lead to cytokine release and itch. CBDs have been shown to enter cells, target and upregulate genes with decreased oxidation and inflammation, and protect membrane integrity in skin cells. Therefore, this might be helpful in atopic dermatitis.” Other potential uses in dermatology include wound healing, acne, hair growth modulation, skin and hair pigmentation, skin infections, psoriasis, and cutaneous malignancies, as well as neuropathic pain.

Evidence is strongest for neuropathic pain, he said, which is mediated by CB-1 receptors peripherally, followed by itch and atopic dermatitis. The authors of a 2017 systematic review concluded that “low-strength” evidence exists to suggest that cannabis alleviates neuropathic pain, with insufficient evidence for other types of pain.

Topical CBD comes in various forms: oils (usually hemp oil), creams, and lotions, Dr. Anhalt said. “I advise patients to apply it 2-4 times per day depending on how anxious or uncomfortable they are. It takes my patients 10 days to 2 weeks before they notice anything at all.”

For atopic dermatitis, it could be useful “not to use it instead of a moisturizer, but as a moisturizer,” Dr. Anhalt advised. “You can have a patient get big jars of CBD creams and lotions. They may have to try a few before they find one that they really like, but you can replace all of the other moisturizers that you’re using right now in patients who have a lot of itch.”

As for CBD’s effect on peripheral neuropathy, the medical literature is lacking, but some studies show low to moderate evidence of efficacy. For example, a Cochrane Review found that a 30% or greater pain reduction was achieved by 39% of patients who used cannabis-based treatments, vs. 33% of those on placebo.

“I would not suggest CBD as a first-line drug unless it’s very mild peripheral neuropathy, but for patients who are on gabapentin who are better but not better enough, this is an excellent adjunct,” Dr. Anhalt said. “It’s worth trying. It’s not too expensive and it’s really safe.”

The application of topical CBD to treat cutaneous malignancies has not yet shown evidence of significant efficacy, while using CBDs for acne holds promise. “The endogenous cannabinoid system is involved in the production of lipids,” he said. “Cannabinoids have an antilipogenic activity, so they decrease sebum production. CBD could help patients with mild acne who are reluctant to use other types of medications. For this and other potential dermatologic applications, lots more studies need to be done.”

Dr. Anhalt reported having no financial disclosures.

.

“When you walk into places like CVS or Walgreens, you see lots of displays for CBD creams and oils,” Todd S. Anhalt, MD, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “The problem is, we don’t know what’s in them or who made them or how good they are. That’s going to be a problem for a while.”

According to Dr. Anhalt, clinical professor emeritus of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, there are about 140 active cannabinoid compounds in cannabis, but the most important ones are THC and cannabidiol (CBD). There are three types of cannabinoids, based on where the cannabidiol is produced: endocannabinoids, which are produced in the human body; phytocannabinoids, which are derived from plants such as marijuana and hemp; and synthetic cannabinoids, which are derived in labs.

Dr. Anhalt described the endocannabinoid system as a conserved network of molecular signaling made of several components: signaling molecules (endocannabinoids), endocannabinoid receptors (CB-1 and CB-2), enzymes, and transporters. There is also overlap between cannabinoids and terpenes, which are responsible for flavor and aroma in plants and marijuana and can enhance the effects of CBD.

“For the most part, CB-1 receptors are in the central nervous system and CB-2 [receptors] are mostly in the periphery,” including the skin and digestive system, said Dr. Anhalt, who practices at the California Skin Institute in Los Altos, Calif. “This is interesting because one of the main conditions I recommend cannabidiol for is in patients with peripheral neuropathy, despite the fact they may be on all sorts of medications such as Neurontin and Lyrica or tricyclic antidepressants. Sometimes they don’t get much relief from those. I have had many patients tell me that they have had reduction of pain and increased functionality using the CBD creams.” CB-2 receptors, he noted, are located in keratinocytes, sensory receptors, sweat glands, fibroblasts, Langerhans cells, melanocytes, and sebaceous glands.

Recent research shows that the endocannabinoid system is involved in modulation of the CNS and in immune function, particularly skin homeostasis and barrier function. “We know that barrier function can be affected by the generation of oxidative species,” he said. “The stress that it causes can decrease barrier function and lead to cytokine release and itch. CBDs have been shown to enter cells, target and upregulate genes with decreased oxidation and inflammation, and protect membrane integrity in skin cells. Therefore, this might be helpful in atopic dermatitis.” Other potential uses in dermatology include wound healing, acne, hair growth modulation, skin and hair pigmentation, skin infections, psoriasis, and cutaneous malignancies, as well as neuropathic pain.

Evidence is strongest for neuropathic pain, he said, which is mediated by CB-1 receptors peripherally, followed by itch and atopic dermatitis. The authors of a 2017 systematic review concluded that “low-strength” evidence exists to suggest that cannabis alleviates neuropathic pain, with insufficient evidence for other types of pain.

Topical CBD comes in various forms: oils (usually hemp oil), creams, and lotions, Dr. Anhalt said. “I advise patients to apply it 2-4 times per day depending on how anxious or uncomfortable they are. It takes my patients 10 days to 2 weeks before they notice anything at all.”

For atopic dermatitis, it could be useful “not to use it instead of a moisturizer, but as a moisturizer,” Dr. Anhalt advised. “You can have a patient get big jars of CBD creams and lotions. They may have to try a few before they find one that they really like, but you can replace all of the other moisturizers that you’re using right now in patients who have a lot of itch.”

As for CBD’s effect on peripheral neuropathy, the medical literature is lacking, but some studies show low to moderate evidence of efficacy. For example, a Cochrane Review found that a 30% or greater pain reduction was achieved by 39% of patients who used cannabis-based treatments, vs. 33% of those on placebo.

“I would not suggest CBD as a first-line drug unless it’s very mild peripheral neuropathy, but for patients who are on gabapentin who are better but not better enough, this is an excellent adjunct,” Dr. Anhalt said. “It’s worth trying. It’s not too expensive and it’s really safe.”

The application of topical CBD to treat cutaneous malignancies has not yet shown evidence of significant efficacy, while using CBDs for acne holds promise. “The endogenous cannabinoid system is involved in the production of lipids,” he said. “Cannabinoids have an antilipogenic activity, so they decrease sebum production. CBD could help patients with mild acne who are reluctant to use other types of medications. For this and other potential dermatologic applications, lots more studies need to be done.”

Dr. Anhalt reported having no financial disclosures.

.

“When you walk into places like CVS or Walgreens, you see lots of displays for CBD creams and oils,” Todd S. Anhalt, MD, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “The problem is, we don’t know what’s in them or who made them or how good they are. That’s going to be a problem for a while.”

According to Dr. Anhalt, clinical professor emeritus of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, there are about 140 active cannabinoid compounds in cannabis, but the most important ones are THC and cannabidiol (CBD). There are three types of cannabinoids, based on where the cannabidiol is produced: endocannabinoids, which are produced in the human body; phytocannabinoids, which are derived from plants such as marijuana and hemp; and synthetic cannabinoids, which are derived in labs.

Dr. Anhalt described the endocannabinoid system as a conserved network of molecular signaling made of several components: signaling molecules (endocannabinoids), endocannabinoid receptors (CB-1 and CB-2), enzymes, and transporters. There is also overlap between cannabinoids and terpenes, which are responsible for flavor and aroma in plants and marijuana and can enhance the effects of CBD.

“For the most part, CB-1 receptors are in the central nervous system and CB-2 [receptors] are mostly in the periphery,” including the skin and digestive system, said Dr. Anhalt, who practices at the California Skin Institute in Los Altos, Calif. “This is interesting because one of the main conditions I recommend cannabidiol for is in patients with peripheral neuropathy, despite the fact they may be on all sorts of medications such as Neurontin and Lyrica or tricyclic antidepressants. Sometimes they don’t get much relief from those. I have had many patients tell me that they have had reduction of pain and increased functionality using the CBD creams.” CB-2 receptors, he noted, are located in keratinocytes, sensory receptors, sweat glands, fibroblasts, Langerhans cells, melanocytes, and sebaceous glands.

Recent research shows that the endocannabinoid system is involved in modulation of the CNS and in immune function, particularly skin homeostasis and barrier function. “We know that barrier function can be affected by the generation of oxidative species,” he said. “The stress that it causes can decrease barrier function and lead to cytokine release and itch. CBDs have been shown to enter cells, target and upregulate genes with decreased oxidation and inflammation, and protect membrane integrity in skin cells. Therefore, this might be helpful in atopic dermatitis.” Other potential uses in dermatology include wound healing, acne, hair growth modulation, skin and hair pigmentation, skin infections, psoriasis, and cutaneous malignancies, as well as neuropathic pain.

Evidence is strongest for neuropathic pain, he said, which is mediated by CB-1 receptors peripherally, followed by itch and atopic dermatitis. The authors of a 2017 systematic review concluded that “low-strength” evidence exists to suggest that cannabis alleviates neuropathic pain, with insufficient evidence for other types of pain.

Topical CBD comes in various forms: oils (usually hemp oil), creams, and lotions, Dr. Anhalt said. “I advise patients to apply it 2-4 times per day depending on how anxious or uncomfortable they are. It takes my patients 10 days to 2 weeks before they notice anything at all.”

For atopic dermatitis, it could be useful “not to use it instead of a moisturizer, but as a moisturizer,” Dr. Anhalt advised. “You can have a patient get big jars of CBD creams and lotions. They may have to try a few before they find one that they really like, but you can replace all of the other moisturizers that you’re using right now in patients who have a lot of itch.”

As for CBD’s effect on peripheral neuropathy, the medical literature is lacking, but some studies show low to moderate evidence of efficacy. For example, a Cochrane Review found that a 30% or greater pain reduction was achieved by 39% of patients who used cannabis-based treatments, vs. 33% of those on placebo.

“I would not suggest CBD as a first-line drug unless it’s very mild peripheral neuropathy, but for patients who are on gabapentin who are better but not better enough, this is an excellent adjunct,” Dr. Anhalt said. “It’s worth trying. It’s not too expensive and it’s really safe.”

The application of topical CBD to treat cutaneous malignancies has not yet shown evidence of significant efficacy, while using CBDs for acne holds promise. “The endogenous cannabinoid system is involved in the production of lipids,” he said. “Cannabinoids have an antilipogenic activity, so they decrease sebum production. CBD could help patients with mild acne who are reluctant to use other types of medications. For this and other potential dermatologic applications, lots more studies need to be done.”

Dr. Anhalt reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM PDA 2021

How the pandemic prompted one clinic to embrace digital innovation

When the .

“Before COVID, we had zero use of teledermatology,” Dr. Afanasiev, a dermatologist at the practice, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “We didn’t do photography other than the required pre-biopsy photographs, and minimal evaluation of home photos, in response to the patients who say, ‘Wait, doc. Let me pull out my phone and show my photographs.”

During the very first days of the pandemic, in order to accommodate urgent patient requests, she and her colleagues used cloud services for patients to submit photos for concerning skin conditions or lesions, which were then discussed over commonly available video platforms. But they quickly realized that this would not work long-term so within two months, they created an electronic health record–integrated workflow that they are still using, she said.

Here’s how it works. If the patient request is deemed nonacute or does not require a full-body skin exam, the scheduling team offers that patient a store-and-video evaluation (SAVe) or an in-person visit. If a SAVe visit is requested, the patient is required to submit a photograph of his or her condition, then a medical assistant checks for the presence and quality of up to nine patient-submitted photos and contacts the patient if additional photos are required.

Immediately before the encounter, a medical assistant calls the patient to ensure video connectivity and performs a brief intake history. The patient and physician then connect via a video-capable platform – most commonly Vidyo, which is integrated with EPIC. After the visit, the provider notifies the scheduling team if any additional in-person or virtual follow up is required.

In a half day of practice, Dr. Afanasiev sees about 20 patients via video visits scheduled every 15 minutes. On a recent day, 55% of visits were related to acne and 10% were related to a mole check, which usually resulted in recommendation for biopsy. Most (70%) were existing patients, while 30% were new.

“There is no store-and-forward option at this time, meaning that patients can’t just submit a photo without a visit,” she said. “In addition, part of our consent is, if you don’t show up to your scheduled video visit, your photos will not be reviewed. The photos are linked to the video visit and uploaded to the patient’s chart. The rooming workflow is very similar to in clinic, except you’re at home and the medical assistant is remote.”

In an article recently published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Afanasiev and her colleagues described their experience with this photo plus video teledermatology – SAVe – workflow between March 16, 2020, and Aug. 31, 2020. The researchers analyzed 74,411 dermatology cases encountered by 89 providers who cared for 46,024 patients during that time frame. Most of the encounters (79%) were in-person, while the remaining 21% were digital in nature – SAVe in 89% of cases, followed by telephone/message encounters.

At the initial peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020, SAVe encounters increased to 72% of all encounters from 0% prior to March 16, 2020, and were sustained at 12% when the clinic reopened in the summer of 2020. Over the study period, the clinic’s incorporation of SAVe increased care access to patients located in 731 unique ZIP codes in and near California. “We also have been able to retain many patients within our system,” Dr. Afanasiev said. “We have a large proportion of patients that require 2-3 hours of travel time to get to our clinic, so virtual visits allowed for increased rural access. It also allowed for flexibility for patients and providers.”

The new workflow also led to faster access to care. The time from referral to an in-person evaluation fell from an average of 56 days in 2019 to average of 27 days in 2020, while the wait time for a virtual visit was just 14 days in 2020. “We were able to see a diverse number of diagnostic categories with both in-person and virtual care, most commonly rashes, acne, dermal growths, and pigmentary disorders,” she said.

For clinicians interested in incorporating a SAVe-like system into their workflow, Dr. Afanasiev advises them to think seriously about consent. “You want to make sure patients understand what they’re getting themselves into,” she said. “You want to make sure they know that some diagnoses cannot be adequately addressed by teledermatology.” Photo quality is also important, she said. “Video quality is not good enough for most of our diagnoses, so photos are an important part of this evaluation. In this day and age, patients are actually pretty good photographers most of the time.”

She urges practices to carefully think about how they allow patients to submit photos, especially if photographs are not attached to a billable visit.

In her opinion, a good teledermatology platform should have trained support staff with the ability for patients to send photos prior to their visit, and should be safe, secure, and HIPAA compliant. It should also be app and browser compatible and have high resolution and low downtime.

“Into the future, I think it’s important to maintain teledermatology within our clinical practice, especially for remote monitoring of chronic skin diseases,” Dr. Afanasiev said. “Oftentimes we schedule 3- or 6-month follow-ups but often those do not correspond to the patients’ disease flare. They may have had an eczema or psoriatic flare 3 weeks prior, but we see them in clinic with clear skin, which makes it hard to judge how to tailor our treatment. It will also be important for us to understand the safety and security and legal implications of these new practice styles.”

She also referred to technological advances, which she said “will dovetail well with teledermatology, including robust at-home and commercial 3D virtual capture technology, machine learning algorithms for improved photos, and virtual biopsy technology.”

Dr. Afanasiev is a member of the American Academy of Dermatology Teledermatology Task Force. She had no relevant disclosures.

When the .

“Before COVID, we had zero use of teledermatology,” Dr. Afanasiev, a dermatologist at the practice, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “We didn’t do photography other than the required pre-biopsy photographs, and minimal evaluation of home photos, in response to the patients who say, ‘Wait, doc. Let me pull out my phone and show my photographs.”

During the very first days of the pandemic, in order to accommodate urgent patient requests, she and her colleagues used cloud services for patients to submit photos for concerning skin conditions or lesions, which were then discussed over commonly available video platforms. But they quickly realized that this would not work long-term so within two months, they created an electronic health record–integrated workflow that they are still using, she said.

Here’s how it works. If the patient request is deemed nonacute or does not require a full-body skin exam, the scheduling team offers that patient a store-and-video evaluation (SAVe) or an in-person visit. If a SAVe visit is requested, the patient is required to submit a photograph of his or her condition, then a medical assistant checks for the presence and quality of up to nine patient-submitted photos and contacts the patient if additional photos are required.

Immediately before the encounter, a medical assistant calls the patient to ensure video connectivity and performs a brief intake history. The patient and physician then connect via a video-capable platform – most commonly Vidyo, which is integrated with EPIC. After the visit, the provider notifies the scheduling team if any additional in-person or virtual follow up is required.

In a half day of practice, Dr. Afanasiev sees about 20 patients via video visits scheduled every 15 minutes. On a recent day, 55% of visits were related to acne and 10% were related to a mole check, which usually resulted in recommendation for biopsy. Most (70%) were existing patients, while 30% were new.

“There is no store-and-forward option at this time, meaning that patients can’t just submit a photo without a visit,” she said. “In addition, part of our consent is, if you don’t show up to your scheduled video visit, your photos will not be reviewed. The photos are linked to the video visit and uploaded to the patient’s chart. The rooming workflow is very similar to in clinic, except you’re at home and the medical assistant is remote.”

In an article recently published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Afanasiev and her colleagues described their experience with this photo plus video teledermatology – SAVe – workflow between March 16, 2020, and Aug. 31, 2020. The researchers analyzed 74,411 dermatology cases encountered by 89 providers who cared for 46,024 patients during that time frame. Most of the encounters (79%) were in-person, while the remaining 21% were digital in nature – SAVe in 89% of cases, followed by telephone/message encounters.

At the initial peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020, SAVe encounters increased to 72% of all encounters from 0% prior to March 16, 2020, and were sustained at 12% when the clinic reopened in the summer of 2020. Over the study period, the clinic’s incorporation of SAVe increased care access to patients located in 731 unique ZIP codes in and near California. “We also have been able to retain many patients within our system,” Dr. Afanasiev said. “We have a large proportion of patients that require 2-3 hours of travel time to get to our clinic, so virtual visits allowed for increased rural access. It also allowed for flexibility for patients and providers.”

The new workflow also led to faster access to care. The time from referral to an in-person evaluation fell from an average of 56 days in 2019 to average of 27 days in 2020, while the wait time for a virtual visit was just 14 days in 2020. “We were able to see a diverse number of diagnostic categories with both in-person and virtual care, most commonly rashes, acne, dermal growths, and pigmentary disorders,” she said.

For clinicians interested in incorporating a SAVe-like system into their workflow, Dr. Afanasiev advises them to think seriously about consent. “You want to make sure patients understand what they’re getting themselves into,” she said. “You want to make sure they know that some diagnoses cannot be adequately addressed by teledermatology.” Photo quality is also important, she said. “Video quality is not good enough for most of our diagnoses, so photos are an important part of this evaluation. In this day and age, patients are actually pretty good photographers most of the time.”

She urges practices to carefully think about how they allow patients to submit photos, especially if photographs are not attached to a billable visit.

In her opinion, a good teledermatology platform should have trained support staff with the ability for patients to send photos prior to their visit, and should be safe, secure, and HIPAA compliant. It should also be app and browser compatible and have high resolution and low downtime.

“Into the future, I think it’s important to maintain teledermatology within our clinical practice, especially for remote monitoring of chronic skin diseases,” Dr. Afanasiev said. “Oftentimes we schedule 3- or 6-month follow-ups but often those do not correspond to the patients’ disease flare. They may have had an eczema or psoriatic flare 3 weeks prior, but we see them in clinic with clear skin, which makes it hard to judge how to tailor our treatment. It will also be important for us to understand the safety and security and legal implications of these new practice styles.”

She also referred to technological advances, which she said “will dovetail well with teledermatology, including robust at-home and commercial 3D virtual capture technology, machine learning algorithms for improved photos, and virtual biopsy technology.”

Dr. Afanasiev is a member of the American Academy of Dermatology Teledermatology Task Force. She had no relevant disclosures.

When the .

“Before COVID, we had zero use of teledermatology,” Dr. Afanasiev, a dermatologist at the practice, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “We didn’t do photography other than the required pre-biopsy photographs, and minimal evaluation of home photos, in response to the patients who say, ‘Wait, doc. Let me pull out my phone and show my photographs.”

During the very first days of the pandemic, in order to accommodate urgent patient requests, she and her colleagues used cloud services for patients to submit photos for concerning skin conditions or lesions, which were then discussed over commonly available video platforms. But they quickly realized that this would not work long-term so within two months, they created an electronic health record–integrated workflow that they are still using, she said.

Here’s how it works. If the patient request is deemed nonacute or does not require a full-body skin exam, the scheduling team offers that patient a store-and-video evaluation (SAVe) or an in-person visit. If a SAVe visit is requested, the patient is required to submit a photograph of his or her condition, then a medical assistant checks for the presence and quality of up to nine patient-submitted photos and contacts the patient if additional photos are required.

Immediately before the encounter, a medical assistant calls the patient to ensure video connectivity and performs a brief intake history. The patient and physician then connect via a video-capable platform – most commonly Vidyo, which is integrated with EPIC. After the visit, the provider notifies the scheduling team if any additional in-person or virtual follow up is required.

In a half day of practice, Dr. Afanasiev sees about 20 patients via video visits scheduled every 15 minutes. On a recent day, 55% of visits were related to acne and 10% were related to a mole check, which usually resulted in recommendation for biopsy. Most (70%) were existing patients, while 30% were new.

“There is no store-and-forward option at this time, meaning that patients can’t just submit a photo without a visit,” she said. “In addition, part of our consent is, if you don’t show up to your scheduled video visit, your photos will not be reviewed. The photos are linked to the video visit and uploaded to the patient’s chart. The rooming workflow is very similar to in clinic, except you’re at home and the medical assistant is remote.”

In an article recently published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Afanasiev and her colleagues described their experience with this photo plus video teledermatology – SAVe – workflow between March 16, 2020, and Aug. 31, 2020. The researchers analyzed 74,411 dermatology cases encountered by 89 providers who cared for 46,024 patients during that time frame. Most of the encounters (79%) were in-person, while the remaining 21% were digital in nature – SAVe in 89% of cases, followed by telephone/message encounters.

At the initial peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020, SAVe encounters increased to 72% of all encounters from 0% prior to March 16, 2020, and were sustained at 12% when the clinic reopened in the summer of 2020. Over the study period, the clinic’s incorporation of SAVe increased care access to patients located in 731 unique ZIP codes in and near California. “We also have been able to retain many patients within our system,” Dr. Afanasiev said. “We have a large proportion of patients that require 2-3 hours of travel time to get to our clinic, so virtual visits allowed for increased rural access. It also allowed for flexibility for patients and providers.”

The new workflow also led to faster access to care. The time from referral to an in-person evaluation fell from an average of 56 days in 2019 to average of 27 days in 2020, while the wait time for a virtual visit was just 14 days in 2020. “We were able to see a diverse number of diagnostic categories with both in-person and virtual care, most commonly rashes, acne, dermal growths, and pigmentary disorders,” she said.

For clinicians interested in incorporating a SAVe-like system into their workflow, Dr. Afanasiev advises them to think seriously about consent. “You want to make sure patients understand what they’re getting themselves into,” she said. “You want to make sure they know that some diagnoses cannot be adequately addressed by teledermatology.” Photo quality is also important, she said. “Video quality is not good enough for most of our diagnoses, so photos are an important part of this evaluation. In this day and age, patients are actually pretty good photographers most of the time.”

She urges practices to carefully think about how they allow patients to submit photos, especially if photographs are not attached to a billable visit.

In her opinion, a good teledermatology platform should have trained support staff with the ability for patients to send photos prior to their visit, and should be safe, secure, and HIPAA compliant. It should also be app and browser compatible and have high resolution and low downtime.

“Into the future, I think it’s important to maintain teledermatology within our clinical practice, especially for remote monitoring of chronic skin diseases,” Dr. Afanasiev said. “Oftentimes we schedule 3- or 6-month follow-ups but often those do not correspond to the patients’ disease flare. They may have had an eczema or psoriatic flare 3 weeks prior, but we see them in clinic with clear skin, which makes it hard to judge how to tailor our treatment. It will also be important for us to understand the safety and security and legal implications of these new practice styles.”

She also referred to technological advances, which she said “will dovetail well with teledermatology, including robust at-home and commercial 3D virtual capture technology, machine learning algorithms for improved photos, and virtual biopsy technology.”

Dr. Afanasiev is a member of the American Academy of Dermatology Teledermatology Task Force. She had no relevant disclosures.

FROM PDA 2021

Rare hematologic malignancy may first present to a dermatologist

in about 80% of cases.

“You won’t see blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm listed on our primary cutaneous lymphoma classifications because it’s not technically a primary cutaneous disease,” Brittney K. DeClerck, MD, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “It’s a systemic disease that has secondary cutaneous manifestations. That’s a very important distinction to make, in terms of not missing the underlying disease associated with what might be commonly first seen on the skin.”

BPDCN is a malignancy of plasmacytoid dendritic cells, which capture, process, and present antigen, and allow the remainder of the immune system to be activated. “They are mainly derived from the myeloid cell lineage, and possibly from the lymphoid line in a subset of cases,” said Dr. DeClerck, associate professor of clinical pathology and dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “They secrete high levels of type I interferons, which is important for antiviral immunity, but they can also be implicated in severe systemic inflammatory diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis.”

BPDCN involves the skin in about 80% of cases, she added, “but invariably at some point it involves the bone marrow and has an acute leukemic presentation, whether or not it happens concurrently with what we see on the skin as dermatologists. We also see variable involvement of the peripheral blood, lymph nodes, and the central nervous system.”

The classification of BPDCN has changed over time based on evolving immunohistochemical markers and technologies. For example, in 1995 it was called agranular CD4+ NK cell leukemia, in 2001 it was called blastic NK-cell lymphoma, in 2005 it was called CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm, and in 2008 it was called BPDCN (AML subset). In 2016 it became classified as its own entity: BPDCN.

Because of changing nomenclature, the true incidence of the disease is unknown, but according to the best available literature, 75% of cases occur in men and the median age is between 60 and 70 years, “but all ages can be affected,” Dr. DeClerck said. “Cases seem to come in clusters. Our most recent cluster has been in our pediatric population. At Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, we’ve had three cases in the last couple of years. To me, that was a bit unusual.”

She added that 10%-20% of patients will have either a history of, or will develop another, hematologic malignancy, such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), or acute myelogenous leukemia (AML).

The general prognosis of BPDCN is poor, and the mean time from onset of lesions to an actual diagnosis is about 6.2 months, which underscores the importance of early diagnosis, Dr. DeClerck said. “There can be some nondescript solitary lesions that patients can present with, so don’t hesitate to biopsy.” The median overall survival is less than 20 months, but patients under 60 years of age have a slightly better prognosis.

Clinical presentation

Clinically, the malignancy presents with variable involvement of the skin, bone marrow, lymph nodes, peripheral blood, and central nervous system. “Patients may have one or all of these,” she said. Because 80% of patients have skin lesions, “dermatologists should be aware of this entity in order to communicate with our pathologists to understand that maybe one biopsy isn’t enough. Several biopsies may be required.”

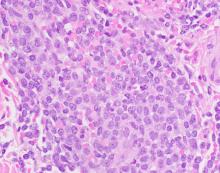

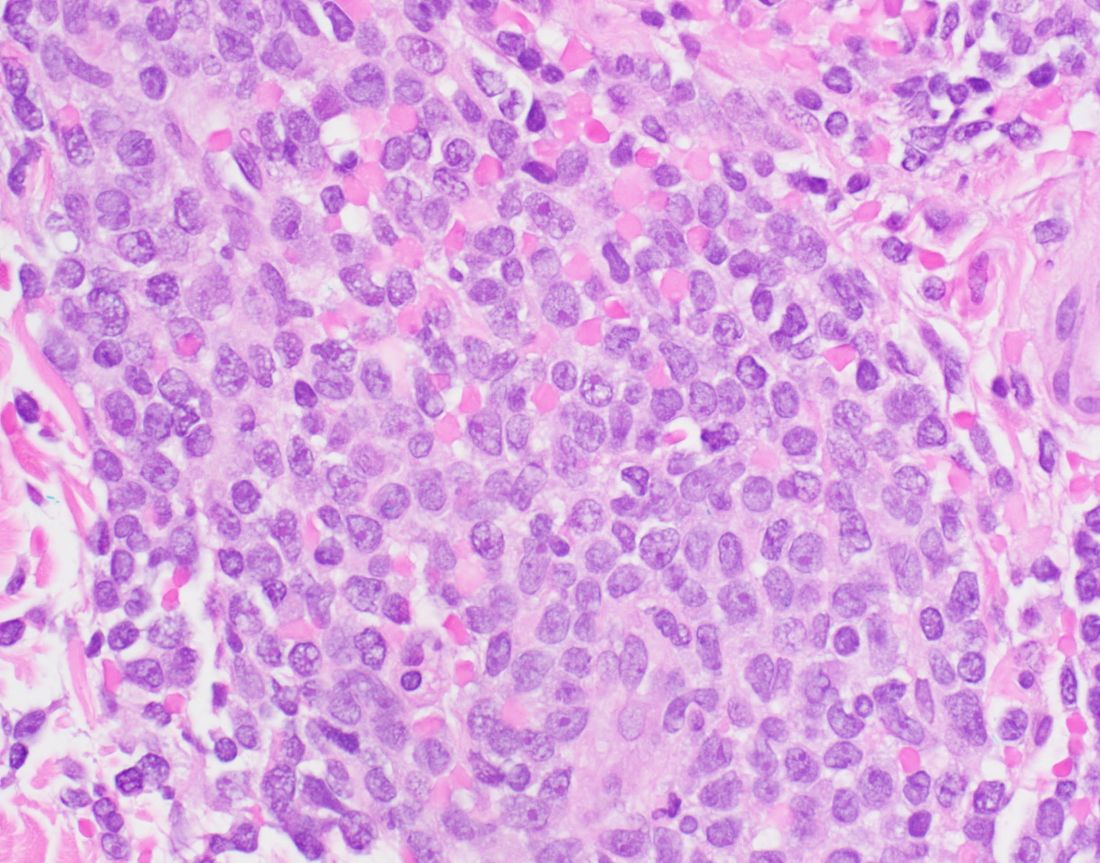

The most common dermatologic presentation of BPDCN is erythematous to deeply violaceous nodules. Other patients may present with infiltrated ecchymotic plaques or petechial to hyperpigmented macules, patches, and plaques. Biopsy reveals a diffusely infiltrated dermis of markedly atypical large cells, but occasionally can be more subtle. “Early lesions may only be perivascular in nature, so going on high power on anything that looks atypical on low power is important in these cases,” Dr. DeClerck said.

The recommended histochemical stains for suspected BPDCN include CD123, CD4, and CD56. “We need to have other stains to rule out other things, such as negative stains that are going to exclude other T cell and B cell processes, and Merkel cell carcinoma, which can express CD56. We also want to have another confirmatory stain because other things can express CD123, CD4, and CD56. Commonly we use TCL1 or TCF4.”

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous findings includes leukemia cutis, mycosis fungoides, NK/T-cell lymphoma, and cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma, while the differential diagnosis of biopsy findings includes AML, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and NK/T-cell lymphoma.

Treatment of BPDCN

Historically, BPDCN was treated with multiagent high-dose chemotherapy. “Patients would frequently respond early but would relapse quickly, progress, and have a poor outcome,” Dr. DeClerck said. Now, first-line therapy is tagraxofusp-erzs (Elzonris) or multiagent chemotherapy based on where the patient is in the course of disease. Tagraxofusp-erzs is an IL-3 conjugated diphtheria toxic fusion protein which binds to CD123, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for treating BPDCN. After that initial therapy, it is determined whether the patient has a complete response or failed response, she said. “If they have a complete response, they frequently go on to bone marrow transplantation, which is the only curative therapy at this point for these patients.”

According to Dr. DeClerck, an anti-BCL-2 therapy, venetoclax, can be used for patients with BPDCN as well. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for the treatment of BPDCN can be found on the NCCN website.

Dr. DeClerck emphasized the importance of reviewing biopsy results with a hematopathologist, “because there are complex leukemias that are beyond what dermatopathologists have been trained in.” Once a patient is diagnosed with BPDCN, she recommends rapid referral to a large center for treatment and possible bone marrow transplantation.

Dr. DeClerck disclosed that she is an adviser for tagraxofusp-erzs manufacturer Stemline Therapeutics.

in about 80% of cases.

“You won’t see blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm listed on our primary cutaneous lymphoma classifications because it’s not technically a primary cutaneous disease,” Brittney K. DeClerck, MD, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “It’s a systemic disease that has secondary cutaneous manifestations. That’s a very important distinction to make, in terms of not missing the underlying disease associated with what might be commonly first seen on the skin.”

BPDCN is a malignancy of plasmacytoid dendritic cells, which capture, process, and present antigen, and allow the remainder of the immune system to be activated. “They are mainly derived from the myeloid cell lineage, and possibly from the lymphoid line in a subset of cases,” said Dr. DeClerck, associate professor of clinical pathology and dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “They secrete high levels of type I interferons, which is important for antiviral immunity, but they can also be implicated in severe systemic inflammatory diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis.”

BPDCN involves the skin in about 80% of cases, she added, “but invariably at some point it involves the bone marrow and has an acute leukemic presentation, whether or not it happens concurrently with what we see on the skin as dermatologists. We also see variable involvement of the peripheral blood, lymph nodes, and the central nervous system.”

The classification of BPDCN has changed over time based on evolving immunohistochemical markers and technologies. For example, in 1995 it was called agranular CD4+ NK cell leukemia, in 2001 it was called blastic NK-cell lymphoma, in 2005 it was called CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm, and in 2008 it was called BPDCN (AML subset). In 2016 it became classified as its own entity: BPDCN.

Because of changing nomenclature, the true incidence of the disease is unknown, but according to the best available literature, 75% of cases occur in men and the median age is between 60 and 70 years, “but all ages can be affected,” Dr. DeClerck said. “Cases seem to come in clusters. Our most recent cluster has been in our pediatric population. At Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, we’ve had three cases in the last couple of years. To me, that was a bit unusual.”

She added that 10%-20% of patients will have either a history of, or will develop another, hematologic malignancy, such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), or acute myelogenous leukemia (AML).

The general prognosis of BPDCN is poor, and the mean time from onset of lesions to an actual diagnosis is about 6.2 months, which underscores the importance of early diagnosis, Dr. DeClerck said. “There can be some nondescript solitary lesions that patients can present with, so don’t hesitate to biopsy.” The median overall survival is less than 20 months, but patients under 60 years of age have a slightly better prognosis.

Clinical presentation

Clinically, the malignancy presents with variable involvement of the skin, bone marrow, lymph nodes, peripheral blood, and central nervous system. “Patients may have one or all of these,” she said. Because 80% of patients have skin lesions, “dermatologists should be aware of this entity in order to communicate with our pathologists to understand that maybe one biopsy isn’t enough. Several biopsies may be required.”

The most common dermatologic presentation of BPDCN is erythematous to deeply violaceous nodules. Other patients may present with infiltrated ecchymotic plaques or petechial to hyperpigmented macules, patches, and plaques. Biopsy reveals a diffusely infiltrated dermis of markedly atypical large cells, but occasionally can be more subtle. “Early lesions may only be perivascular in nature, so going on high power on anything that looks atypical on low power is important in these cases,” Dr. DeClerck said.

The recommended histochemical stains for suspected BPDCN include CD123, CD4, and CD56. “We need to have other stains to rule out other things, such as negative stains that are going to exclude other T cell and B cell processes, and Merkel cell carcinoma, which can express CD56. We also want to have another confirmatory stain because other things can express CD123, CD4, and CD56. Commonly we use TCL1 or TCF4.”

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous findings includes leukemia cutis, mycosis fungoides, NK/T-cell lymphoma, and cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma, while the differential diagnosis of biopsy findings includes AML, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and NK/T-cell lymphoma.

Treatment of BPDCN

Historically, BPDCN was treated with multiagent high-dose chemotherapy. “Patients would frequently respond early but would relapse quickly, progress, and have a poor outcome,” Dr. DeClerck said. Now, first-line therapy is tagraxofusp-erzs (Elzonris) or multiagent chemotherapy based on where the patient is in the course of disease. Tagraxofusp-erzs is an IL-3 conjugated diphtheria toxic fusion protein which binds to CD123, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for treating BPDCN. After that initial therapy, it is determined whether the patient has a complete response or failed response, she said. “If they have a complete response, they frequently go on to bone marrow transplantation, which is the only curative therapy at this point for these patients.”

According to Dr. DeClerck, an anti-BCL-2 therapy, venetoclax, can be used for patients with BPDCN as well. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for the treatment of BPDCN can be found on the NCCN website.

Dr. DeClerck emphasized the importance of reviewing biopsy results with a hematopathologist, “because there are complex leukemias that are beyond what dermatopathologists have been trained in.” Once a patient is diagnosed with BPDCN, she recommends rapid referral to a large center for treatment and possible bone marrow transplantation.

Dr. DeClerck disclosed that she is an adviser for tagraxofusp-erzs manufacturer Stemline Therapeutics.

in about 80% of cases.

“You won’t see blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm listed on our primary cutaneous lymphoma classifications because it’s not technically a primary cutaneous disease,” Brittney K. DeClerck, MD, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “It’s a systemic disease that has secondary cutaneous manifestations. That’s a very important distinction to make, in terms of not missing the underlying disease associated with what might be commonly first seen on the skin.”

BPDCN is a malignancy of plasmacytoid dendritic cells, which capture, process, and present antigen, and allow the remainder of the immune system to be activated. “They are mainly derived from the myeloid cell lineage, and possibly from the lymphoid line in a subset of cases,” said Dr. DeClerck, associate professor of clinical pathology and dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “They secrete high levels of type I interferons, which is important for antiviral immunity, but they can also be implicated in severe systemic inflammatory diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis.”

BPDCN involves the skin in about 80% of cases, she added, “but invariably at some point it involves the bone marrow and has an acute leukemic presentation, whether or not it happens concurrently with what we see on the skin as dermatologists. We also see variable involvement of the peripheral blood, lymph nodes, and the central nervous system.”

The classification of BPDCN has changed over time based on evolving immunohistochemical markers and technologies. For example, in 1995 it was called agranular CD4+ NK cell leukemia, in 2001 it was called blastic NK-cell lymphoma, in 2005 it was called CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm, and in 2008 it was called BPDCN (AML subset). In 2016 it became classified as its own entity: BPDCN.

Because of changing nomenclature, the true incidence of the disease is unknown, but according to the best available literature, 75% of cases occur in men and the median age is between 60 and 70 years, “but all ages can be affected,” Dr. DeClerck said. “Cases seem to come in clusters. Our most recent cluster has been in our pediatric population. At Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, we’ve had three cases in the last couple of years. To me, that was a bit unusual.”

She added that 10%-20% of patients will have either a history of, or will develop another, hematologic malignancy, such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), or acute myelogenous leukemia (AML).

The general prognosis of BPDCN is poor, and the mean time from onset of lesions to an actual diagnosis is about 6.2 months, which underscores the importance of early diagnosis, Dr. DeClerck said. “There can be some nondescript solitary lesions that patients can present with, so don’t hesitate to biopsy.” The median overall survival is less than 20 months, but patients under 60 years of age have a slightly better prognosis.

Clinical presentation

Clinically, the malignancy presents with variable involvement of the skin, bone marrow, lymph nodes, peripheral blood, and central nervous system. “Patients may have one or all of these,” she said. Because 80% of patients have skin lesions, “dermatologists should be aware of this entity in order to communicate with our pathologists to understand that maybe one biopsy isn’t enough. Several biopsies may be required.”

The most common dermatologic presentation of BPDCN is erythematous to deeply violaceous nodules. Other patients may present with infiltrated ecchymotic plaques or petechial to hyperpigmented macules, patches, and plaques. Biopsy reveals a diffusely infiltrated dermis of markedly atypical large cells, but occasionally can be more subtle. “Early lesions may only be perivascular in nature, so going on high power on anything that looks atypical on low power is important in these cases,” Dr. DeClerck said.

The recommended histochemical stains for suspected BPDCN include CD123, CD4, and CD56. “We need to have other stains to rule out other things, such as negative stains that are going to exclude other T cell and B cell processes, and Merkel cell carcinoma, which can express CD56. We also want to have another confirmatory stain because other things can express CD123, CD4, and CD56. Commonly we use TCL1 or TCF4.”

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous findings includes leukemia cutis, mycosis fungoides, NK/T-cell lymphoma, and cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma, while the differential diagnosis of biopsy findings includes AML, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and NK/T-cell lymphoma.

Treatment of BPDCN

Historically, BPDCN was treated with multiagent high-dose chemotherapy. “Patients would frequently respond early but would relapse quickly, progress, and have a poor outcome,” Dr. DeClerck said. Now, first-line therapy is tagraxofusp-erzs (Elzonris) or multiagent chemotherapy based on where the patient is in the course of disease. Tagraxofusp-erzs is an IL-3 conjugated diphtheria toxic fusion protein which binds to CD123, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for treating BPDCN. After that initial therapy, it is determined whether the patient has a complete response or failed response, she said. “If they have a complete response, they frequently go on to bone marrow transplantation, which is the only curative therapy at this point for these patients.”

According to Dr. DeClerck, an anti-BCL-2 therapy, venetoclax, can be used for patients with BPDCN as well. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for the treatment of BPDCN can be found on the NCCN website.

Dr. DeClerck emphasized the importance of reviewing biopsy results with a hematopathologist, “because there are complex leukemias that are beyond what dermatopathologists have been trained in.” Once a patient is diagnosed with BPDCN, she recommends rapid referral to a large center for treatment and possible bone marrow transplantation.

Dr. DeClerck disclosed that she is an adviser for tagraxofusp-erzs manufacturer Stemline Therapeutics.

FROM PDA 2021

Skin ulcers can pose tricky diagnostic challenges

In the clinical opinion of Alex G. Ortega-Loayza, MD, MCR, few absolutes drive the initial assessment of patients who present with skin ulcers.

The causes can be neoplastic, infectious, inflammatory, vasculopathic, external, and genetic. “Sometimes they can be of mixed etiology, which make them even more complicated to heal,” Dr. Ortega-Loayza, of the department of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

In a study published in 2019, he and his colleagues at four academic hospitals evaluated characteristics and diagnoses of ulcers in 274 patients with skin ulcers in inpatient dermatology consultation services between July 2015 and July 2018. Most primary teams requesting the consultation (93%) were from nonsurgical specialties. The median age of these patients was 54 years, 45% were male, and 50% had lower-extremity ulcers. Nearly two-thirds of the ulcers (62%) were chronic in nature, while the remaining 38% were acute. The skin ulcer was the chief reason for admission in 49% of cases and 66% were admitted through the ED. In addition, 11% had a superinfected skin ulcer.

The top three etiologies rendered by dermatologists after assessing these patients were pyoderma gangrenosum (17%), infection (13%), and exogenous causes (12%); another 12% remained diagnostically inconclusive after consultation. Diagnostic agreements between the primary team requesting the consultation and the dermatologist were poor to modest.

These data highlights the role of the dermatologists in the workup of skin ulcers of unknown etiology.

“The diagnosis of skin ulcers can be challenging,” Dr. Ortega-Loayza said. “Subjective factors playing a role in the diagnosis of skin ulcers include the type of level of training/experience you’ve had and general awareness and education about skin ulcers.” In addition, there is also a lack of gold-standard diagnostic criteria for atypical/inflammatory ulcers and a lack of specificity of ancillary testing, such as for pyoderma gangrenosum.

Dr. Ortega-Loayza’s basic workup is based on the review of systems and the patient’s comorbidities. Blood work may include CBC, comprehensive metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, albumin/prealbumin, autoimmune panels, and hypercoagulable panels. He may order a skin biopsy with H&E staining and microbiological studies, superficial bacterial wound cultures, and vascular studies, such as ankle brachial index (ABI) and chronic venous reflux tests, and Doppler ultrasound, and he might consider an angiogram for certain type of ulcers. Additional imaging studies may include x-ray, CT scan, and/or MRI.

The four key factors to control in patients with skin ulcers, he continued, include effective management of edema (such as compression garments depending on the results of the vascular studies); infection (with topical/oral antibiotics and debridement); the wound microenvironment (with wound dressings), and pain (mainly with nonopioids). “In my practice, we tend to do multilayered compression,” he said. “This can be two- or four-layer. I do light compression if the patient has peripheral arterial disease. I always bring in the patient 2 days later to check on them, or do a telehealth visit, to make sure they are not developing any worsening of the ulcers.”

Infections can be managed with topical antimicrobials such as metronidazole 1% gel and cadexomer iodine. “Iodine can also help dry the wound when you need to do so,” said Dr. Ortega-Loayza, who directs a pyoderma gangrenosum clinic at OHSU. “Debridement can be done with a curette or with commercially available enzymatic products such as Collagenase, PluroGel, and MediHoney.”

When the ulcer is in an active phase (characterized by significant amount of drainage and erythema), he uses one or more of the following products to control the wound microenvironment: zinc oxide, an antimicrobial dressing, a hyperabsorbent dressing, an abdominal pad, and compression.

During the healing phase, with evidence of re-epithelization, he tends to use more foam dressings and continues with compression. His preferred options for managing pain associated with ulcers are medications to control neuropathic pain including initially gabapentin (100 mg-300 mg at bedtime), pregabalin (75 mg twice a day), or duloxetine (extended release, 30 mg once a day). All of these medications can be titrated up based on patients’ needs. Foam dressings with ibuprofen can also provide comfort, he said.

Dr. Ortega-Loayza also provided a few clinical pearls highlighting the role and utility of interleukin-23 inhibitors in the management of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum, oral vitamin K in patients with calciphylaxis, and stanozolol for lipodermatosclerosis. He is also leading the first open-label trial testing a Janus kinase inhibitor – baricitinib – as a treatment for patients with pyoderma gangrenosum.

Dr. Ortega-Loayza disclosed that he is a consultant to Genentech and Guidepoint and is a member of the advisory board for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Janssen. He also has received research support from Lilly.

In the clinical opinion of Alex G. Ortega-Loayza, MD, MCR, few absolutes drive the initial assessment of patients who present with skin ulcers.

The causes can be neoplastic, infectious, inflammatory, vasculopathic, external, and genetic. “Sometimes they can be of mixed etiology, which make them even more complicated to heal,” Dr. Ortega-Loayza, of the department of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

In a study published in 2019, he and his colleagues at four academic hospitals evaluated characteristics and diagnoses of ulcers in 274 patients with skin ulcers in inpatient dermatology consultation services between July 2015 and July 2018. Most primary teams requesting the consultation (93%) were from nonsurgical specialties. The median age of these patients was 54 years, 45% were male, and 50% had lower-extremity ulcers. Nearly two-thirds of the ulcers (62%) were chronic in nature, while the remaining 38% were acute. The skin ulcer was the chief reason for admission in 49% of cases and 66% were admitted through the ED. In addition, 11% had a superinfected skin ulcer.

The top three etiologies rendered by dermatologists after assessing these patients were pyoderma gangrenosum (17%), infection (13%), and exogenous causes (12%); another 12% remained diagnostically inconclusive after consultation. Diagnostic agreements between the primary team requesting the consultation and the dermatologist were poor to modest.

These data highlights the role of the dermatologists in the workup of skin ulcers of unknown etiology.

“The diagnosis of skin ulcers can be challenging,” Dr. Ortega-Loayza said. “Subjective factors playing a role in the diagnosis of skin ulcers include the type of level of training/experience you’ve had and general awareness and education about skin ulcers.” In addition, there is also a lack of gold-standard diagnostic criteria for atypical/inflammatory ulcers and a lack of specificity of ancillary testing, such as for pyoderma gangrenosum.

Dr. Ortega-Loayza’s basic workup is based on the review of systems and the patient’s comorbidities. Blood work may include CBC, comprehensive metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, albumin/prealbumin, autoimmune panels, and hypercoagulable panels. He may order a skin biopsy with H&E staining and microbiological studies, superficial bacterial wound cultures, and vascular studies, such as ankle brachial index (ABI) and chronic venous reflux tests, and Doppler ultrasound, and he might consider an angiogram for certain type of ulcers. Additional imaging studies may include x-ray, CT scan, and/or MRI.

The four key factors to control in patients with skin ulcers, he continued, include effective management of edema (such as compression garments depending on the results of the vascular studies); infection (with topical/oral antibiotics and debridement); the wound microenvironment (with wound dressings), and pain (mainly with nonopioids). “In my practice, we tend to do multilayered compression,” he said. “This can be two- or four-layer. I do light compression if the patient has peripheral arterial disease. I always bring in the patient 2 days later to check on them, or do a telehealth visit, to make sure they are not developing any worsening of the ulcers.”

Infections can be managed with topical antimicrobials such as metronidazole 1% gel and cadexomer iodine. “Iodine can also help dry the wound when you need to do so,” said Dr. Ortega-Loayza, who directs a pyoderma gangrenosum clinic at OHSU. “Debridement can be done with a curette or with commercially available enzymatic products such as Collagenase, PluroGel, and MediHoney.”

When the ulcer is in an active phase (characterized by significant amount of drainage and erythema), he uses one or more of the following products to control the wound microenvironment: zinc oxide, an antimicrobial dressing, a hyperabsorbent dressing, an abdominal pad, and compression.

During the healing phase, with evidence of re-epithelization, he tends to use more foam dressings and continues with compression. His preferred options for managing pain associated with ulcers are medications to control neuropathic pain including initially gabapentin (100 mg-300 mg at bedtime), pregabalin (75 mg twice a day), or duloxetine (extended release, 30 mg once a day). All of these medications can be titrated up based on patients’ needs. Foam dressings with ibuprofen can also provide comfort, he said.

Dr. Ortega-Loayza also provided a few clinical pearls highlighting the role and utility of interleukin-23 inhibitors in the management of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum, oral vitamin K in patients with calciphylaxis, and stanozolol for lipodermatosclerosis. He is also leading the first open-label trial testing a Janus kinase inhibitor – baricitinib – as a treatment for patients with pyoderma gangrenosum.

Dr. Ortega-Loayza disclosed that he is a consultant to Genentech and Guidepoint and is a member of the advisory board for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Janssen. He also has received research support from Lilly.

In the clinical opinion of Alex G. Ortega-Loayza, MD, MCR, few absolutes drive the initial assessment of patients who present with skin ulcers.

The causes can be neoplastic, infectious, inflammatory, vasculopathic, external, and genetic. “Sometimes they can be of mixed etiology, which make them even more complicated to heal,” Dr. Ortega-Loayza, of the department of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

In a study published in 2019, he and his colleagues at four academic hospitals evaluated characteristics and diagnoses of ulcers in 274 patients with skin ulcers in inpatient dermatology consultation services between July 2015 and July 2018. Most primary teams requesting the consultation (93%) were from nonsurgical specialties. The median age of these patients was 54 years, 45% were male, and 50% had lower-extremity ulcers. Nearly two-thirds of the ulcers (62%) were chronic in nature, while the remaining 38% were acute. The skin ulcer was the chief reason for admission in 49% of cases and 66% were admitted through the ED. In addition, 11% had a superinfected skin ulcer.

The top three etiologies rendered by dermatologists after assessing these patients were pyoderma gangrenosum (17%), infection (13%), and exogenous causes (12%); another 12% remained diagnostically inconclusive after consultation. Diagnostic agreements between the primary team requesting the consultation and the dermatologist were poor to modest.

These data highlights the role of the dermatologists in the workup of skin ulcers of unknown etiology.

“The diagnosis of skin ulcers can be challenging,” Dr. Ortega-Loayza said. “Subjective factors playing a role in the diagnosis of skin ulcers include the type of level of training/experience you’ve had and general awareness and education about skin ulcers.” In addition, there is also a lack of gold-standard diagnostic criteria for atypical/inflammatory ulcers and a lack of specificity of ancillary testing, such as for pyoderma gangrenosum.

Dr. Ortega-Loayza’s basic workup is based on the review of systems and the patient’s comorbidities. Blood work may include CBC, comprehensive metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, albumin/prealbumin, autoimmune panels, and hypercoagulable panels. He may order a skin biopsy with H&E staining and microbiological studies, superficial bacterial wound cultures, and vascular studies, such as ankle brachial index (ABI) and chronic venous reflux tests, and Doppler ultrasound, and he might consider an angiogram for certain type of ulcers. Additional imaging studies may include x-ray, CT scan, and/or MRI.

The four key factors to control in patients with skin ulcers, he continued, include effective management of edema (such as compression garments depending on the results of the vascular studies); infection (with topical/oral antibiotics and debridement); the wound microenvironment (with wound dressings), and pain (mainly with nonopioids). “In my practice, we tend to do multilayered compression,” he said. “This can be two- or four-layer. I do light compression if the patient has peripheral arterial disease. I always bring in the patient 2 days later to check on them, or do a telehealth visit, to make sure they are not developing any worsening of the ulcers.”

Infections can be managed with topical antimicrobials such as metronidazole 1% gel and cadexomer iodine. “Iodine can also help dry the wound when you need to do so,” said Dr. Ortega-Loayza, who directs a pyoderma gangrenosum clinic at OHSU. “Debridement can be done with a curette or with commercially available enzymatic products such as Collagenase, PluroGel, and MediHoney.”

When the ulcer is in an active phase (characterized by significant amount of drainage and erythema), he uses one or more of the following products to control the wound microenvironment: zinc oxide, an antimicrobial dressing, a hyperabsorbent dressing, an abdominal pad, and compression.

During the healing phase, with evidence of re-epithelization, he tends to use more foam dressings and continues with compression. His preferred options for managing pain associated with ulcers are medications to control neuropathic pain including initially gabapentin (100 mg-300 mg at bedtime), pregabalin (75 mg twice a day), or duloxetine (extended release, 30 mg once a day). All of these medications can be titrated up based on patients’ needs. Foam dressings with ibuprofen can also provide comfort, he said.

Dr. Ortega-Loayza also provided a few clinical pearls highlighting the role and utility of interleukin-23 inhibitors in the management of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum, oral vitamin K in patients with calciphylaxis, and stanozolol for lipodermatosclerosis. He is also leading the first open-label trial testing a Janus kinase inhibitor – baricitinib – as a treatment for patients with pyoderma gangrenosum.

Dr. Ortega-Loayza disclosed that he is a consultant to Genentech and Guidepoint and is a member of the advisory board for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Janssen. He also has received research support from Lilly.

FROM PDA 2021

Expert shares vulvovaginal candidiasis treatment pearls

that was approved in June 2021, Aruna Venkatesan, MD, recommends.

“Ibrexafungerp, an inhibitor of beta (1-3)–glucan synthase, is important for many reasons,” Dr. Venkatesan, chief of dermatology and director of the genital dermatology clinic at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, San Jose, Calif., said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “It’s one of the few drugs that can be used to treat Candida glabrata when C. glabrata is resistant to azoles and echinocandins. As the second-most common Candida species after C. albicans, C. glabrata is more common in immunosuppressed patients and it can cause mucosal and invasive disease, so ibrexafungerp is a welcome addition to our treatment armamentarium,” said Dr. Venkatesan, clinical professor of dermatology (affiliated) at Stanford (Calif.) Hospital and Clinics, adding that that vulvovaginal candidiasis can be tricky to diagnose. “In medical school, we learned that yeast infection in a woman presents as white, curd-like discharge, but that’s actually a minority of patients.”

For a patient who is being treated with topical steroids or estrogen for a genital condition, but is experiencing worsening itch, redness, or thick white discharge, she recommends performing a KOH exam.

“Instead of using a 15-blade scalpel, as we are used to performing on the skin for tinea, take a sterile [cotton swab], and swab the affected area. You can then apply it to a slide and perform a KOH exam as you normally would. Then look for yeast elements under the microscope. I also find it helpful to send for fungal culture to get speciation, especially in someone who’s not responding to therapy. This is because non-albicans yeast can be more resistant to azoles and require a different treatment plan.”

Often, patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis who present to her clinic are referred from an ob.gyn. and other general practitioners because they have failed a topical or oral azole. “I tend to avoid the topicals,” said Dr. Venkatesan, who is also president-elect of the North American chapter of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease. “If the culture shows C. albicans, I usually treat with oral fluconazole, 150 mg or 200 mg once, and consider repeat weekly dosing. Many patients come to me because they have recurrent refractory disease, so giving it once weekly for 6-8 weeks while they work on their potential risk factors such as diabetic blood sugar control is sensible.”

Non-albicans yeast can be resistant to azoles. If the fungal culture shows C. glabrata in such patients, “consider a course of intravaginal boric acid suppositories,” she advised. “These used to be difficult to give patients, because you would either have to send the prescription to a compounding pharmacy, or have the patients buy the capsules and boric acid crystals separately and make them themselves. That always made me nervous because of the chance of errors. The safety and the concern of taking it by mouth is an issue.” But now, intravaginal boric acid suppositories are available on Amazon and other web sites, and are relatively affordable, she said, adding, “just make sure the patient doesn’t take it by mouth as this is very toxic.”

Dr. Venkatesan reported having no financial disclosures.

that was approved in June 2021, Aruna Venkatesan, MD, recommends.

“Ibrexafungerp, an inhibitor of beta (1-3)–glucan synthase, is important for many reasons,” Dr. Venkatesan, chief of dermatology and director of the genital dermatology clinic at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, San Jose, Calif., said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “It’s one of the few drugs that can be used to treat Candida glabrata when C. glabrata is resistant to azoles and echinocandins. As the second-most common Candida species after C. albicans, C. glabrata is more common in immunosuppressed patients and it can cause mucosal and invasive disease, so ibrexafungerp is a welcome addition to our treatment armamentarium,” said Dr. Venkatesan, clinical professor of dermatology (affiliated) at Stanford (Calif.) Hospital and Clinics, adding that that vulvovaginal candidiasis can be tricky to diagnose. “In medical school, we learned that yeast infection in a woman presents as white, curd-like discharge, but that’s actually a minority of patients.”

For a patient who is being treated with topical steroids or estrogen for a genital condition, but is experiencing worsening itch, redness, or thick white discharge, she recommends performing a KOH exam.

“Instead of using a 15-blade scalpel, as we are used to performing on the skin for tinea, take a sterile [cotton swab], and swab the affected area. You can then apply it to a slide and perform a KOH exam as you normally would. Then look for yeast elements under the microscope. I also find it helpful to send for fungal culture to get speciation, especially in someone who’s not responding to therapy. This is because non-albicans yeast can be more resistant to azoles and require a different treatment plan.”

Often, patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis who present to her clinic are referred from an ob.gyn. and other general practitioners because they have failed a topical or oral azole. “I tend to avoid the topicals,” said Dr. Venkatesan, who is also president-elect of the North American chapter of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease. “If the culture shows C. albicans, I usually treat with oral fluconazole, 150 mg or 200 mg once, and consider repeat weekly dosing. Many patients come to me because they have recurrent refractory disease, so giving it once weekly for 6-8 weeks while they work on their potential risk factors such as diabetic blood sugar control is sensible.”

Non-albicans yeast can be resistant to azoles. If the fungal culture shows C. glabrata in such patients, “consider a course of intravaginal boric acid suppositories,” she advised. “These used to be difficult to give patients, because you would either have to send the prescription to a compounding pharmacy, or have the patients buy the capsules and boric acid crystals separately and make them themselves. That always made me nervous because of the chance of errors. The safety and the concern of taking it by mouth is an issue.” But now, intravaginal boric acid suppositories are available on Amazon and other web sites, and are relatively affordable, she said, adding, “just make sure the patient doesn’t take it by mouth as this is very toxic.”

Dr. Venkatesan reported having no financial disclosures.

that was approved in June 2021, Aruna Venkatesan, MD, recommends.

“Ibrexafungerp, an inhibitor of beta (1-3)–glucan synthase, is important for many reasons,” Dr. Venkatesan, chief of dermatology and director of the genital dermatology clinic at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, San Jose, Calif., said during the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “It’s one of the few drugs that can be used to treat Candida glabrata when C. glabrata is resistant to azoles and echinocandins. As the second-most common Candida species after C. albicans, C. glabrata is more common in immunosuppressed patients and it can cause mucosal and invasive disease, so ibrexafungerp is a welcome addition to our treatment armamentarium,” said Dr. Venkatesan, clinical professor of dermatology (affiliated) at Stanford (Calif.) Hospital and Clinics, adding that that vulvovaginal candidiasis can be tricky to diagnose. “In medical school, we learned that yeast infection in a woman presents as white, curd-like discharge, but that’s actually a minority of patients.”

For a patient who is being treated with topical steroids or estrogen for a genital condition, but is experiencing worsening itch, redness, or thick white discharge, she recommends performing a KOH exam.

“Instead of using a 15-blade scalpel, as we are used to performing on the skin for tinea, take a sterile [cotton swab], and swab the affected area. You can then apply it to a slide and perform a KOH exam as you normally would. Then look for yeast elements under the microscope. I also find it helpful to send for fungal culture to get speciation, especially in someone who’s not responding to therapy. This is because non-albicans yeast can be more resistant to azoles and require a different treatment plan.”

Often, patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis who present to her clinic are referred from an ob.gyn. and other general practitioners because they have failed a topical or oral azole. “I tend to avoid the topicals,” said Dr. Venkatesan, who is also president-elect of the North American chapter of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease. “If the culture shows C. albicans, I usually treat with oral fluconazole, 150 mg or 200 mg once, and consider repeat weekly dosing. Many patients come to me because they have recurrent refractory disease, so giving it once weekly for 6-8 weeks while they work on their potential risk factors such as diabetic blood sugar control is sensible.”

Non-albicans yeast can be resistant to azoles. If the fungal culture shows C. glabrata in such patients, “consider a course of intravaginal boric acid suppositories,” she advised. “These used to be difficult to give patients, because you would either have to send the prescription to a compounding pharmacy, or have the patients buy the capsules and boric acid crystals separately and make them themselves. That always made me nervous because of the chance of errors. The safety and the concern of taking it by mouth is an issue.” But now, intravaginal boric acid suppositories are available on Amazon and other web sites, and are relatively affordable, she said, adding, “just make sure the patient doesn’t take it by mouth as this is very toxic.”

Dr. Venkatesan reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM PDA 2021