User login

Better late than later: Lessons learned from an investigator-led clinical trial

As a second-year gastroenterology fellow, I designed a prospective, double-blind randomized, controlled trial for vitamin D repletion in patients with Crohn’s disease at a referral inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) center. I had the support of a dedicated research team, several mentors, and a 2-year time frame in which to complete this study. Intellectually curious and academically eager, I labored over a grant application that I did not receive. Under generous financial support from my department, I forged on and opened the trial for enrollment at the start of my advanced IBD fellowship year. However, we experienced recruitment challenges that ultimately led to the study’s premature termination. Through this journey, I gained invaluable experience that will continue to serve me – and, I hope, the reader – as I progress in my career. Below are some important insights gleaned from this experience that may benefit others interested in clinical trial design.

Know your “why” (personally and clinically)

Asked to reflect on their career path, experts tend to recount their “being in the right place at the right time” and having “good mentors.” While luck and good mentorship are necessary, I propose that doing your homework is equally as important. Before ambling down the path of an investigator-led trial, I urge a hard pause to reflect on your “why.” The personal “why” of “getting into fellowship,” “advancement in the department,” or “learning more about the principles of research,” are all valid. But I suggest a deeper dive is in order. Successful clinical trials require resources, a substantial time commitment, lots of sweat and maybe a few tears. In the ideal setting, your trial experience will serve as the foundation for a compelling personal narrative and might help launch a productive clinical research career. With stakes that high, asking the tough questions is critical.

The clinical “why” is just as critical. We press our attendings on why they used this drug or that clip, so don’t be afraid to ask whether this is a space in which others have succeeded. Or conversely, why is there such a large gap in the literature? I remember emailing the world’s expert about my topic because the published data were so murky. He had more questions than answers which, in retrospect, should have raised red flags about the ability to design a sound study. It is equally important to determine if patients are vested in the research question. A successful clinical trial hinges on subject participation, often outside their clinic visit. Patients with complex chronic diseases spend a lot of time navigating the health care system. Participating in a clinical trial needs to be meaningful to them if you want your patients to fully engage. Thoughtfully answering these questions on the front end – for yourself and the study in question – will improve both your experience and the ultimate outcome exponentially.

Identify your village (and listen to them)

Designing a clinical trial truly takes a village, and you need to identify the villagers early. As trainees, the value of mentorship is frequently underscored. But the importance of, and the nuance involved in managing, collaborating, and support cannot be overstated. Meet with a biostatistician to ensure your sample size calculations are correct. Work closely with the research pharmacist to ensure the medication formulation is available; decide on the manner of distribution so as not to inconvenience subjects; create a budget with an experienced manager. Seek out research coordinators often for assistance in creating case report forms, learning appropriate documentation, and crafting responses to Institutional Review Board concerns. Ask clinic personnel about arranging consent or follow-up visits around subjects’ clinic appointments. Present a draft of the protocol to your colleagues, as you will ultimately need them on board to recruit patients. And most importantly, listen to them ... all of them. Get your biases in check and write down all constructive criticism. Thoughtfully address each concern encountered to your satisfaction (and your mentor’s) and present to your village again. Rinse and repeat. Throw nothing under the rug, because if you do, it will eventually rear its head while you are in the throes of the study.

In retrospect, there were concerns raised by faculty and grant reviewers that I did not adequately address. First was the feasibility of screening, recruiting, and enrolling 80 patients during a busy clinical fellowship. While I took this criticism as a reflection of my personal commitment to the project, it was actually a call to consider the impact on clinical (and familial) responsibilities. But as I started enrolling patients, I realized there were logistic issues implied in this suggestion. I could not recruit subjects in Clinic A if I was assigned to see patients at the same time in Clinic B. Patients were not likely to come back another day for study-related discussions. Second, I designed eligibility criteria to make the data as clean as possible. Limiting the study to subjects with Crohn’s disease, in clinical and biochemical remission, without complications of their disease, who also have vitamin deficiency, may be an unrealistic recipe to recruit 80 people in a limited period of time. Finally, I designed laboratory follow-up schedules based on the pharmacokinetics of the drug alone, failing to consider the clinical milieu from which study subjects were recruited. Neglecting the fact that many patients obtain labs with their infusions, my study increased lab draw burden, heaped more patient reminders onto my plate – and more concerning – decreased overall study compliance. In short, trial design cannot be done in a vacuum or by just poring over published data. There are logistical and patient-related considerations that require early input from physicians and clinical staff in order for all the moving parts of a clinical trial to successfully work in harmony.

Create a timetable and follow it

Make a recruitment timetable very early on in the enrollment period. Set up biweekly meetings with mentors to discuss enrollment numbers and reflect on any unforeseen challenges. And be sure to celebrate the wins as well – not matter how small. In our study, falling behind on recruitment goals forced me to amend the stringent eligibility criteria and add additional manpower to help with reminders for laboratory follow-up and patient screening. These pivots caused study delays and cost resources. Ultimately, having a timetable forced me to take pause when it became clear I could not finish the study in the allotted time.

Know when to fold ’em

Knowing when to close a study is far easier said than done. The sunk cost fallacy says it is much harder to abandon a project after investing so many resources into it. For us, it was the recruitment timetable that gave us pause. Finishing trial accrual by the end of my advanced fellowship year was wholly unfeasible. When it became clear that nobody in the department could see it through to completion, I was propelled to terminate the study. If there is concern about termination, I suggest sending the protocol, recruitment numbers, and timeline to an outside colleague for a second, unbiased opinion. Review the already compiled data for any notable findings worthy of a smaller publication. It is said, we often learn more from our failures than our successes. The experience described herein – largely in part to my mentors, collaborators, and the patients who put their faith in me – translates to a lasting, invaluable win.

Mentor’s note

Clinical research is hard. Many trainees meet with me to “get involved” in clinical research, and the challenge as a mentor is to identify a project appropriate to the level of training and provide the infrastructure and resources to facilitate success for the motivated trainee. Trainees have various goals of their involvement in research – to foster a relationship in the hopes of receiving a strong letter of support, to facilitate getting into a competitive training program, and/or to publish. My goal as a mentor is to help my trainees reach their goals, but as a clinical researcher, I look for the trainee’s desire to engage with and learn the research process, with the ancillary potential for a letter, for acceptance to a program, or for publication.

This particular study, a randomized, controlled trial of vitamin D in patients with Crohn’s disease, involved an enormous undertaking by a very motivated trainee who took the project from its inception; to putting a thoughtful grant proposal together; to developing a full clinical trial protocol with its ancillary regulatory documents; and obtaining institutional review board approval, statistician input, pharmacy support, and buy-in from faculty and ancillary staff stakeholders. The study ultimately failed because of low enrollment – patients did not want to participate (for reasons elucidated above) – not because of poor design or execution of the myriad components of a prospective clinical trial. Low enrollment has led to the failure of many otherwise excellent studies, including several in our field of IBD.1,2 As a mentor, it is rational to accept blame for the failure of a trainee project; how could I have better foreseen the outcome of this study? Could this have been prevented with more support, more oversight, or more “micromanagement,” to the potential detriment of fostering independence?

Ultimately, the value of clinical research to trainees is multifaceted. If the goal was a first-author publication with high clinical impact, this trial failed. But if the goal was to learn about the clinical trial process, this study was a resounding success. Ultimately, it behooves trainees and their mentors to engage in early, upfront conversations about research. What are the goals? What does success look like? What if the trial fails? By shifting the focus from the success of the project to the success of the mentorship and educational process, even failed projects are resounding successes, upon which future careers can be further developed.

References

1. Kan S et al. When subjects violate the research covenant: Lessons learned from a failed clinical trial of fecal microbiota transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1508-10.

2. Dassopoulos T et al. Randomised clinical trial: Individualised vs.weight-based dosing of azathioprine in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Jan;39(2):163-75.

Dr. Cohen is an inflammatory bowel disease fellow, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Dr. Melmed is director, inflammatory bowel disease clinical research and codirector, clinical inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

As a second-year gastroenterology fellow, I designed a prospective, double-blind randomized, controlled trial for vitamin D repletion in patients with Crohn’s disease at a referral inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) center. I had the support of a dedicated research team, several mentors, and a 2-year time frame in which to complete this study. Intellectually curious and academically eager, I labored over a grant application that I did not receive. Under generous financial support from my department, I forged on and opened the trial for enrollment at the start of my advanced IBD fellowship year. However, we experienced recruitment challenges that ultimately led to the study’s premature termination. Through this journey, I gained invaluable experience that will continue to serve me – and, I hope, the reader – as I progress in my career. Below are some important insights gleaned from this experience that may benefit others interested in clinical trial design.

Know your “why” (personally and clinically)

Asked to reflect on their career path, experts tend to recount their “being in the right place at the right time” and having “good mentors.” While luck and good mentorship are necessary, I propose that doing your homework is equally as important. Before ambling down the path of an investigator-led trial, I urge a hard pause to reflect on your “why.” The personal “why” of “getting into fellowship,” “advancement in the department,” or “learning more about the principles of research,” are all valid. But I suggest a deeper dive is in order. Successful clinical trials require resources, a substantial time commitment, lots of sweat and maybe a few tears. In the ideal setting, your trial experience will serve as the foundation for a compelling personal narrative and might help launch a productive clinical research career. With stakes that high, asking the tough questions is critical.

The clinical “why” is just as critical. We press our attendings on why they used this drug or that clip, so don’t be afraid to ask whether this is a space in which others have succeeded. Or conversely, why is there such a large gap in the literature? I remember emailing the world’s expert about my topic because the published data were so murky. He had more questions than answers which, in retrospect, should have raised red flags about the ability to design a sound study. It is equally important to determine if patients are vested in the research question. A successful clinical trial hinges on subject participation, often outside their clinic visit. Patients with complex chronic diseases spend a lot of time navigating the health care system. Participating in a clinical trial needs to be meaningful to them if you want your patients to fully engage. Thoughtfully answering these questions on the front end – for yourself and the study in question – will improve both your experience and the ultimate outcome exponentially.

Identify your village (and listen to them)

Designing a clinical trial truly takes a village, and you need to identify the villagers early. As trainees, the value of mentorship is frequently underscored. But the importance of, and the nuance involved in managing, collaborating, and support cannot be overstated. Meet with a biostatistician to ensure your sample size calculations are correct. Work closely with the research pharmacist to ensure the medication formulation is available; decide on the manner of distribution so as not to inconvenience subjects; create a budget with an experienced manager. Seek out research coordinators often for assistance in creating case report forms, learning appropriate documentation, and crafting responses to Institutional Review Board concerns. Ask clinic personnel about arranging consent or follow-up visits around subjects’ clinic appointments. Present a draft of the protocol to your colleagues, as you will ultimately need them on board to recruit patients. And most importantly, listen to them ... all of them. Get your biases in check and write down all constructive criticism. Thoughtfully address each concern encountered to your satisfaction (and your mentor’s) and present to your village again. Rinse and repeat. Throw nothing under the rug, because if you do, it will eventually rear its head while you are in the throes of the study.

In retrospect, there were concerns raised by faculty and grant reviewers that I did not adequately address. First was the feasibility of screening, recruiting, and enrolling 80 patients during a busy clinical fellowship. While I took this criticism as a reflection of my personal commitment to the project, it was actually a call to consider the impact on clinical (and familial) responsibilities. But as I started enrolling patients, I realized there were logistic issues implied in this suggestion. I could not recruit subjects in Clinic A if I was assigned to see patients at the same time in Clinic B. Patients were not likely to come back another day for study-related discussions. Second, I designed eligibility criteria to make the data as clean as possible. Limiting the study to subjects with Crohn’s disease, in clinical and biochemical remission, without complications of their disease, who also have vitamin deficiency, may be an unrealistic recipe to recruit 80 people in a limited period of time. Finally, I designed laboratory follow-up schedules based on the pharmacokinetics of the drug alone, failing to consider the clinical milieu from which study subjects were recruited. Neglecting the fact that many patients obtain labs with their infusions, my study increased lab draw burden, heaped more patient reminders onto my plate – and more concerning – decreased overall study compliance. In short, trial design cannot be done in a vacuum or by just poring over published data. There are logistical and patient-related considerations that require early input from physicians and clinical staff in order for all the moving parts of a clinical trial to successfully work in harmony.

Create a timetable and follow it

Make a recruitment timetable very early on in the enrollment period. Set up biweekly meetings with mentors to discuss enrollment numbers and reflect on any unforeseen challenges. And be sure to celebrate the wins as well – not matter how small. In our study, falling behind on recruitment goals forced me to amend the stringent eligibility criteria and add additional manpower to help with reminders for laboratory follow-up and patient screening. These pivots caused study delays and cost resources. Ultimately, having a timetable forced me to take pause when it became clear I could not finish the study in the allotted time.

Know when to fold ’em

Knowing when to close a study is far easier said than done. The sunk cost fallacy says it is much harder to abandon a project after investing so many resources into it. For us, it was the recruitment timetable that gave us pause. Finishing trial accrual by the end of my advanced fellowship year was wholly unfeasible. When it became clear that nobody in the department could see it through to completion, I was propelled to terminate the study. If there is concern about termination, I suggest sending the protocol, recruitment numbers, and timeline to an outside colleague for a second, unbiased opinion. Review the already compiled data for any notable findings worthy of a smaller publication. It is said, we often learn more from our failures than our successes. The experience described herein – largely in part to my mentors, collaborators, and the patients who put their faith in me – translates to a lasting, invaluable win.

Mentor’s note

Clinical research is hard. Many trainees meet with me to “get involved” in clinical research, and the challenge as a mentor is to identify a project appropriate to the level of training and provide the infrastructure and resources to facilitate success for the motivated trainee. Trainees have various goals of their involvement in research – to foster a relationship in the hopes of receiving a strong letter of support, to facilitate getting into a competitive training program, and/or to publish. My goal as a mentor is to help my trainees reach their goals, but as a clinical researcher, I look for the trainee’s desire to engage with and learn the research process, with the ancillary potential for a letter, for acceptance to a program, or for publication.

This particular study, a randomized, controlled trial of vitamin D in patients with Crohn’s disease, involved an enormous undertaking by a very motivated trainee who took the project from its inception; to putting a thoughtful grant proposal together; to developing a full clinical trial protocol with its ancillary regulatory documents; and obtaining institutional review board approval, statistician input, pharmacy support, and buy-in from faculty and ancillary staff stakeholders. The study ultimately failed because of low enrollment – patients did not want to participate (for reasons elucidated above) – not because of poor design or execution of the myriad components of a prospective clinical trial. Low enrollment has led to the failure of many otherwise excellent studies, including several in our field of IBD.1,2 As a mentor, it is rational to accept blame for the failure of a trainee project; how could I have better foreseen the outcome of this study? Could this have been prevented with more support, more oversight, or more “micromanagement,” to the potential detriment of fostering independence?

Ultimately, the value of clinical research to trainees is multifaceted. If the goal was a first-author publication with high clinical impact, this trial failed. But if the goal was to learn about the clinical trial process, this study was a resounding success. Ultimately, it behooves trainees and their mentors to engage in early, upfront conversations about research. What are the goals? What does success look like? What if the trial fails? By shifting the focus from the success of the project to the success of the mentorship and educational process, even failed projects are resounding successes, upon which future careers can be further developed.

References

1. Kan S et al. When subjects violate the research covenant: Lessons learned from a failed clinical trial of fecal microbiota transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1508-10.

2. Dassopoulos T et al. Randomised clinical trial: Individualised vs.weight-based dosing of azathioprine in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Jan;39(2):163-75.

Dr. Cohen is an inflammatory bowel disease fellow, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Dr. Melmed is director, inflammatory bowel disease clinical research and codirector, clinical inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

As a second-year gastroenterology fellow, I designed a prospective, double-blind randomized, controlled trial for vitamin D repletion in patients with Crohn’s disease at a referral inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) center. I had the support of a dedicated research team, several mentors, and a 2-year time frame in which to complete this study. Intellectually curious and academically eager, I labored over a grant application that I did not receive. Under generous financial support from my department, I forged on and opened the trial for enrollment at the start of my advanced IBD fellowship year. However, we experienced recruitment challenges that ultimately led to the study’s premature termination. Through this journey, I gained invaluable experience that will continue to serve me – and, I hope, the reader – as I progress in my career. Below are some important insights gleaned from this experience that may benefit others interested in clinical trial design.

Know your “why” (personally and clinically)

Asked to reflect on their career path, experts tend to recount their “being in the right place at the right time” and having “good mentors.” While luck and good mentorship are necessary, I propose that doing your homework is equally as important. Before ambling down the path of an investigator-led trial, I urge a hard pause to reflect on your “why.” The personal “why” of “getting into fellowship,” “advancement in the department,” or “learning more about the principles of research,” are all valid. But I suggest a deeper dive is in order. Successful clinical trials require resources, a substantial time commitment, lots of sweat and maybe a few tears. In the ideal setting, your trial experience will serve as the foundation for a compelling personal narrative and might help launch a productive clinical research career. With stakes that high, asking the tough questions is critical.

The clinical “why” is just as critical. We press our attendings on why they used this drug or that clip, so don’t be afraid to ask whether this is a space in which others have succeeded. Or conversely, why is there such a large gap in the literature? I remember emailing the world’s expert about my topic because the published data were so murky. He had more questions than answers which, in retrospect, should have raised red flags about the ability to design a sound study. It is equally important to determine if patients are vested in the research question. A successful clinical trial hinges on subject participation, often outside their clinic visit. Patients with complex chronic diseases spend a lot of time navigating the health care system. Participating in a clinical trial needs to be meaningful to them if you want your patients to fully engage. Thoughtfully answering these questions on the front end – for yourself and the study in question – will improve both your experience and the ultimate outcome exponentially.

Identify your village (and listen to them)

Designing a clinical trial truly takes a village, and you need to identify the villagers early. As trainees, the value of mentorship is frequently underscored. But the importance of, and the nuance involved in managing, collaborating, and support cannot be overstated. Meet with a biostatistician to ensure your sample size calculations are correct. Work closely with the research pharmacist to ensure the medication formulation is available; decide on the manner of distribution so as not to inconvenience subjects; create a budget with an experienced manager. Seek out research coordinators often for assistance in creating case report forms, learning appropriate documentation, and crafting responses to Institutional Review Board concerns. Ask clinic personnel about arranging consent or follow-up visits around subjects’ clinic appointments. Present a draft of the protocol to your colleagues, as you will ultimately need them on board to recruit patients. And most importantly, listen to them ... all of them. Get your biases in check and write down all constructive criticism. Thoughtfully address each concern encountered to your satisfaction (and your mentor’s) and present to your village again. Rinse and repeat. Throw nothing under the rug, because if you do, it will eventually rear its head while you are in the throes of the study.

In retrospect, there were concerns raised by faculty and grant reviewers that I did not adequately address. First was the feasibility of screening, recruiting, and enrolling 80 patients during a busy clinical fellowship. While I took this criticism as a reflection of my personal commitment to the project, it was actually a call to consider the impact on clinical (and familial) responsibilities. But as I started enrolling patients, I realized there were logistic issues implied in this suggestion. I could not recruit subjects in Clinic A if I was assigned to see patients at the same time in Clinic B. Patients were not likely to come back another day for study-related discussions. Second, I designed eligibility criteria to make the data as clean as possible. Limiting the study to subjects with Crohn’s disease, in clinical and biochemical remission, without complications of their disease, who also have vitamin deficiency, may be an unrealistic recipe to recruit 80 people in a limited period of time. Finally, I designed laboratory follow-up schedules based on the pharmacokinetics of the drug alone, failing to consider the clinical milieu from which study subjects were recruited. Neglecting the fact that many patients obtain labs with their infusions, my study increased lab draw burden, heaped more patient reminders onto my plate – and more concerning – decreased overall study compliance. In short, trial design cannot be done in a vacuum or by just poring over published data. There are logistical and patient-related considerations that require early input from physicians and clinical staff in order for all the moving parts of a clinical trial to successfully work in harmony.

Create a timetable and follow it

Make a recruitment timetable very early on in the enrollment period. Set up biweekly meetings with mentors to discuss enrollment numbers and reflect on any unforeseen challenges. And be sure to celebrate the wins as well – not matter how small. In our study, falling behind on recruitment goals forced me to amend the stringent eligibility criteria and add additional manpower to help with reminders for laboratory follow-up and patient screening. These pivots caused study delays and cost resources. Ultimately, having a timetable forced me to take pause when it became clear I could not finish the study in the allotted time.

Know when to fold ’em

Knowing when to close a study is far easier said than done. The sunk cost fallacy says it is much harder to abandon a project after investing so many resources into it. For us, it was the recruitment timetable that gave us pause. Finishing trial accrual by the end of my advanced fellowship year was wholly unfeasible. When it became clear that nobody in the department could see it through to completion, I was propelled to terminate the study. If there is concern about termination, I suggest sending the protocol, recruitment numbers, and timeline to an outside colleague for a second, unbiased opinion. Review the already compiled data for any notable findings worthy of a smaller publication. It is said, we often learn more from our failures than our successes. The experience described herein – largely in part to my mentors, collaborators, and the patients who put their faith in me – translates to a lasting, invaluable win.

Mentor’s note

Clinical research is hard. Many trainees meet with me to “get involved” in clinical research, and the challenge as a mentor is to identify a project appropriate to the level of training and provide the infrastructure and resources to facilitate success for the motivated trainee. Trainees have various goals of their involvement in research – to foster a relationship in the hopes of receiving a strong letter of support, to facilitate getting into a competitive training program, and/or to publish. My goal as a mentor is to help my trainees reach their goals, but as a clinical researcher, I look for the trainee’s desire to engage with and learn the research process, with the ancillary potential for a letter, for acceptance to a program, or for publication.

This particular study, a randomized, controlled trial of vitamin D in patients with Crohn’s disease, involved an enormous undertaking by a very motivated trainee who took the project from its inception; to putting a thoughtful grant proposal together; to developing a full clinical trial protocol with its ancillary regulatory documents; and obtaining institutional review board approval, statistician input, pharmacy support, and buy-in from faculty and ancillary staff stakeholders. The study ultimately failed because of low enrollment – patients did not want to participate (for reasons elucidated above) – not because of poor design or execution of the myriad components of a prospective clinical trial. Low enrollment has led to the failure of many otherwise excellent studies, including several in our field of IBD.1,2 As a mentor, it is rational to accept blame for the failure of a trainee project; how could I have better foreseen the outcome of this study? Could this have been prevented with more support, more oversight, or more “micromanagement,” to the potential detriment of fostering independence?

Ultimately, the value of clinical research to trainees is multifaceted. If the goal was a first-author publication with high clinical impact, this trial failed. But if the goal was to learn about the clinical trial process, this study was a resounding success. Ultimately, it behooves trainees and their mentors to engage in early, upfront conversations about research. What are the goals? What does success look like? What if the trial fails? By shifting the focus from the success of the project to the success of the mentorship and educational process, even failed projects are resounding successes, upon which future careers can be further developed.

References

1. Kan S et al. When subjects violate the research covenant: Lessons learned from a failed clinical trial of fecal microbiota transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1508-10.

2. Dassopoulos T et al. Randomised clinical trial: Individualised vs.weight-based dosing of azathioprine in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Jan;39(2):163-75.

Dr. Cohen is an inflammatory bowel disease fellow, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Dr. Melmed is director, inflammatory bowel disease clinical research and codirector, clinical inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

A career in industry: Is it right for me?

As gastroenterology fellows ponder their futures, one career path is often overlooked. Working in the pharmaceutical or biotechnology industry is a path that is not often at the top of career option lists. It is a rare occurrence for fellows to transition immediately into an industry position as opposed to a clinical or academic post. Initial clinical experience, caring for patients, and gaining experience with health economic challenges in today’s complex environment are considered invaluable assets for job applicants seeking industry positions. A minimum of 3-5 years of real-world clinical care experience will greatly enhance applicants’ marketability as “clinical experts” who can provide meaningful value to industry employers.

What exactly does “industry” mean? Traditionally it includes pharmaceutical and/or biotechnology (discovery, development, manufacture, sales, and marketing of small or large molecules), contract research organizations (CROs), and medical device companies. The variety in terms of size, scope, and reach of these companies is truly staggering and includes: entrepreneurial small startups (fewer than 20 employees, one location), midsize companies (more than 200 employees), and global multinational worldwide behemoths (“big pharma” with more than 50,000 employees and numerous facilities with diverse geographic locations). There are certain geographic regions of the United States where many companies’ headquarters are concentrated. At present (although this certainly can change over time), Cambridge, Mass.; New Jersey; Philadelphia; Raleigh-Durham, N.C.; and the San Francisco Bay Area are “hot areas.”

The breadth of “specialty” areas in industry for experienced clinicians is wide and includes: discovery, translational medicine, early- and late-stage clinical development, medical affairs, patient safety, epidemiology, and commercial development. For those interested in transitioning into industry, it is ideal to have a preferred area in mind so that training and education while in fellowship and clinical practice can be directed to that topic.

Discovery and translational medicine

These areas focus on preclinical development of small and large molecules from first concept until first-in-human studies and filing of an investigational new drug application (IND) with regulatory agencies. Translation of basic science concepts into potentially clinically useful “candidate” molecules requires a strong basic knowledge of science in addition to clinical experience. A passion for bridging novel concepts from “bench” to nonhuman studies is critical for success in this area.

Early-stage clinical development

Early-stage clinical development focuses on progressing discovery candidates to first-in-human studies (phase 1 in healthy volunteers) through phase 2 proof-of-concept studies (PoC). PoC studies typically involve first proof in a clinical trial in the target population that the drug under development may provide clinical benefit. These studies typically include 50-200 subjects with tight inclusion and exclusion controls. Intellectual rigor and scientific curiosity, as well as a passion for protecting patient safety, are essential for success as an early-stage drug developer.

Late-stage clinical development

Late-stage clinical development involves designing, conducting, and executing very large clinical studies (typically with hundreds to thousands of patients) that will provide the necessary rigorous pivotal clinical data supporting new drug marketing applications (NDAs). Relatively few drug candidates successfully make it to this stage of development and these studies are extremely expensive (sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars). This stage of development requires close collaboration with numerous company functions including regulatory, biostatistics, patient safety, clinical pharmacology, clinical operations, and manufacturing, as well as commercial colleagues. In addition to strong clinical expertise, this stage of drug development requires excellent communication, with leadership skills and attention to detail as well. Successfully shepherding a drug candidate through to Food and Drug Administration or other regulatory agency approval is an extremely satisfying experience, which can lead to meaningful differences for patients.

Medical affairs

This is a very important and challenging specialty area that, at its core, demands value demonstration of a medicine and communication to key stakeholders such as patients, physicians, and payers. This objective has become increasingly challenging over the past decade while evolving from a qualitative specialty to a rigorous quantitative one. Scientific and commercial success depends on efficient design, execution, and dissemination of results for real-world evidence and postapproval studies. Ideally, these data will demonstrate the medicine’s benefit-risk profile and how it fits into treatment algorithms. Communication requires leadership of physician and payer advisory boards, as well as publication planning. Close collaboration with marketing teams to advise on ethical and scientifically accurate promotional activities is another key component.

Patient safety

As the name implies, patient safety focuses on evaluating signals both from clinical trials and from literature that can accurately map out risks to patients that can arise from taking these medications. This is a critical function for proper and ethical prescription and use of medicine in today’s society. In addition to signal recognition and consultation with clinical development teams, collaboration with regulatory agencies is an important component.

Epidemiology

Epidemiologists with clinical expertise have become an increasingly important need for pharmaceutical and biotech companies over the past decade – specifically, for the design of real-world studies that demonstrate benefit-risk profiles for medicines in real-world use. These data are in demand for both private and governmental payers, as well as for regulatory agencies who are interested in evolving postapproval safety data. Successful epidemiologists often have acquired MPH degrees and expertise in study design and biostatistics.

Commercial development

Those with more financial or business acumen and clinical experience sometimes staff commercial careers. Typically commercial leads also have an MBA degree and are responsible for assessing commercial markets and forecasting and executing a path to commercial viability. Ultimately this career path can lead to a CEO position.

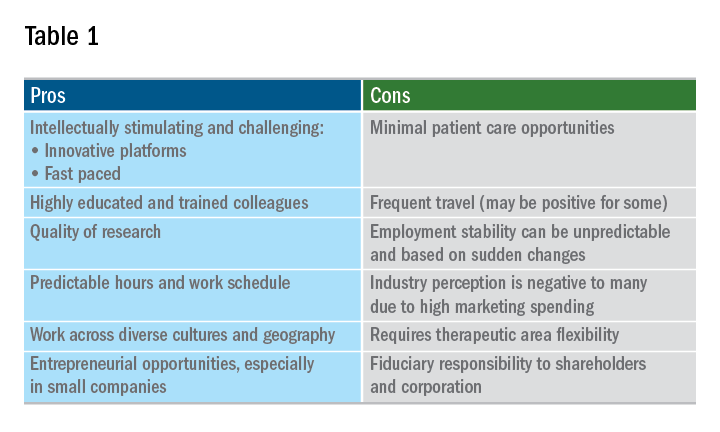

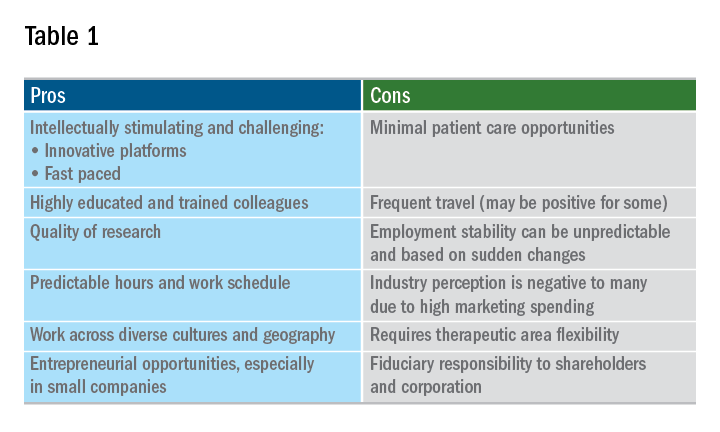

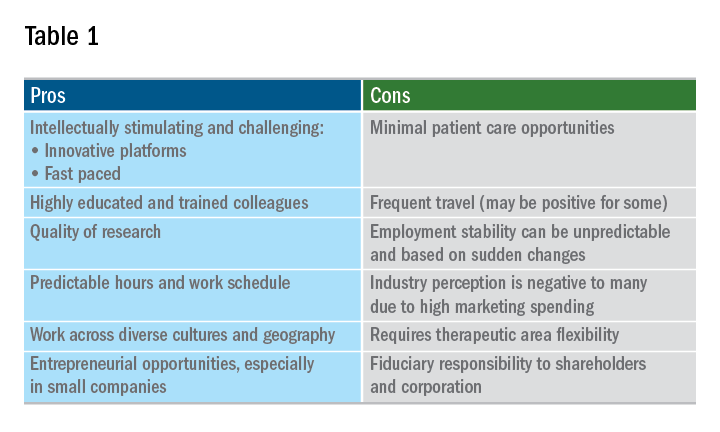

A career in industry is a perfect fit for some, but not so much for others. Table 1 outlines some pros and cons. Commercial factors do come into play with regard to corporate objectives and areas of focus. The top pharmaceutical product therapeutic categories, according to the number of drugs under development in 2017, were cancer, vaccines, diabetes, ophthalmology, gene therapy, anti-inflammatory, and antivirals and immunosuppressants; inflammatory bowel disease was 15th. Therapeutic research and development areas in gastroenterology that are relatively in demand in 2019 include IBD, irritable bowel syndrome, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. The high demand areas seem to change with the science and also payers’ willingness to reimburse.

Is industry a good career choice for you? Consider the following factors:

- Travel capabilities.

- Small biotech versus big pharma versus CRO.

- Capability to function in a team environment.

- Communication skills, resilience, self-awareness.

- Therapeutic area and category.

- Early stage versus late stage versus translational versus medical affairs.

- Additional education: MBA, MPH, PhD.

- Geography.

The pharmaceutical industry evolves and undergoes transformation extremely quickly in response to changes in the external environment. If you are considering a current or future career in industry, staying informed about changes in the delivery of health care and health economics is important. There is an ongoing need in industry for trainees and experienced gastroenterologists who can deploy their clinical expertise in development and communication of new medicines and devices that will make a positive difference in patients’ lives.

As gastroenterology fellows ponder their futures, one career path is often overlooked. Working in the pharmaceutical or biotechnology industry is a path that is not often at the top of career option lists. It is a rare occurrence for fellows to transition immediately into an industry position as opposed to a clinical or academic post. Initial clinical experience, caring for patients, and gaining experience with health economic challenges in today’s complex environment are considered invaluable assets for job applicants seeking industry positions. A minimum of 3-5 years of real-world clinical care experience will greatly enhance applicants’ marketability as “clinical experts” who can provide meaningful value to industry employers.

What exactly does “industry” mean? Traditionally it includes pharmaceutical and/or biotechnology (discovery, development, manufacture, sales, and marketing of small or large molecules), contract research organizations (CROs), and medical device companies. The variety in terms of size, scope, and reach of these companies is truly staggering and includes: entrepreneurial small startups (fewer than 20 employees, one location), midsize companies (more than 200 employees), and global multinational worldwide behemoths (“big pharma” with more than 50,000 employees and numerous facilities with diverse geographic locations). There are certain geographic regions of the United States where many companies’ headquarters are concentrated. At present (although this certainly can change over time), Cambridge, Mass.; New Jersey; Philadelphia; Raleigh-Durham, N.C.; and the San Francisco Bay Area are “hot areas.”

The breadth of “specialty” areas in industry for experienced clinicians is wide and includes: discovery, translational medicine, early- and late-stage clinical development, medical affairs, patient safety, epidemiology, and commercial development. For those interested in transitioning into industry, it is ideal to have a preferred area in mind so that training and education while in fellowship and clinical practice can be directed to that topic.

Discovery and translational medicine

These areas focus on preclinical development of small and large molecules from first concept until first-in-human studies and filing of an investigational new drug application (IND) with regulatory agencies. Translation of basic science concepts into potentially clinically useful “candidate” molecules requires a strong basic knowledge of science in addition to clinical experience. A passion for bridging novel concepts from “bench” to nonhuman studies is critical for success in this area.

Early-stage clinical development

Early-stage clinical development focuses on progressing discovery candidates to first-in-human studies (phase 1 in healthy volunteers) through phase 2 proof-of-concept studies (PoC). PoC studies typically involve first proof in a clinical trial in the target population that the drug under development may provide clinical benefit. These studies typically include 50-200 subjects with tight inclusion and exclusion controls. Intellectual rigor and scientific curiosity, as well as a passion for protecting patient safety, are essential for success as an early-stage drug developer.

Late-stage clinical development

Late-stage clinical development involves designing, conducting, and executing very large clinical studies (typically with hundreds to thousands of patients) that will provide the necessary rigorous pivotal clinical data supporting new drug marketing applications (NDAs). Relatively few drug candidates successfully make it to this stage of development and these studies are extremely expensive (sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars). This stage of development requires close collaboration with numerous company functions including regulatory, biostatistics, patient safety, clinical pharmacology, clinical operations, and manufacturing, as well as commercial colleagues. In addition to strong clinical expertise, this stage of drug development requires excellent communication, with leadership skills and attention to detail as well. Successfully shepherding a drug candidate through to Food and Drug Administration or other regulatory agency approval is an extremely satisfying experience, which can lead to meaningful differences for patients.

Medical affairs

This is a very important and challenging specialty area that, at its core, demands value demonstration of a medicine and communication to key stakeholders such as patients, physicians, and payers. This objective has become increasingly challenging over the past decade while evolving from a qualitative specialty to a rigorous quantitative one. Scientific and commercial success depends on efficient design, execution, and dissemination of results for real-world evidence and postapproval studies. Ideally, these data will demonstrate the medicine’s benefit-risk profile and how it fits into treatment algorithms. Communication requires leadership of physician and payer advisory boards, as well as publication planning. Close collaboration with marketing teams to advise on ethical and scientifically accurate promotional activities is another key component.

Patient safety

As the name implies, patient safety focuses on evaluating signals both from clinical trials and from literature that can accurately map out risks to patients that can arise from taking these medications. This is a critical function for proper and ethical prescription and use of medicine in today’s society. In addition to signal recognition and consultation with clinical development teams, collaboration with regulatory agencies is an important component.

Epidemiology

Epidemiologists with clinical expertise have become an increasingly important need for pharmaceutical and biotech companies over the past decade – specifically, for the design of real-world studies that demonstrate benefit-risk profiles for medicines in real-world use. These data are in demand for both private and governmental payers, as well as for regulatory agencies who are interested in evolving postapproval safety data. Successful epidemiologists often have acquired MPH degrees and expertise in study design and biostatistics.

Commercial development

Those with more financial or business acumen and clinical experience sometimes staff commercial careers. Typically commercial leads also have an MBA degree and are responsible for assessing commercial markets and forecasting and executing a path to commercial viability. Ultimately this career path can lead to a CEO position.

A career in industry is a perfect fit for some, but not so much for others. Table 1 outlines some pros and cons. Commercial factors do come into play with regard to corporate objectives and areas of focus. The top pharmaceutical product therapeutic categories, according to the number of drugs under development in 2017, were cancer, vaccines, diabetes, ophthalmology, gene therapy, anti-inflammatory, and antivirals and immunosuppressants; inflammatory bowel disease was 15th. Therapeutic research and development areas in gastroenterology that are relatively in demand in 2019 include IBD, irritable bowel syndrome, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. The high demand areas seem to change with the science and also payers’ willingness to reimburse.

Is industry a good career choice for you? Consider the following factors:

- Travel capabilities.

- Small biotech versus big pharma versus CRO.

- Capability to function in a team environment.

- Communication skills, resilience, self-awareness.

- Therapeutic area and category.

- Early stage versus late stage versus translational versus medical affairs.

- Additional education: MBA, MPH, PhD.

- Geography.

The pharmaceutical industry evolves and undergoes transformation extremely quickly in response to changes in the external environment. If you are considering a current or future career in industry, staying informed about changes in the delivery of health care and health economics is important. There is an ongoing need in industry for trainees and experienced gastroenterologists who can deploy their clinical expertise in development and communication of new medicines and devices that will make a positive difference in patients’ lives.

As gastroenterology fellows ponder their futures, one career path is often overlooked. Working in the pharmaceutical or biotechnology industry is a path that is not often at the top of career option lists. It is a rare occurrence for fellows to transition immediately into an industry position as opposed to a clinical or academic post. Initial clinical experience, caring for patients, and gaining experience with health economic challenges in today’s complex environment are considered invaluable assets for job applicants seeking industry positions. A minimum of 3-5 years of real-world clinical care experience will greatly enhance applicants’ marketability as “clinical experts” who can provide meaningful value to industry employers.

What exactly does “industry” mean? Traditionally it includes pharmaceutical and/or biotechnology (discovery, development, manufacture, sales, and marketing of small or large molecules), contract research organizations (CROs), and medical device companies. The variety in terms of size, scope, and reach of these companies is truly staggering and includes: entrepreneurial small startups (fewer than 20 employees, one location), midsize companies (more than 200 employees), and global multinational worldwide behemoths (“big pharma” with more than 50,000 employees and numerous facilities with diverse geographic locations). There are certain geographic regions of the United States where many companies’ headquarters are concentrated. At present (although this certainly can change over time), Cambridge, Mass.; New Jersey; Philadelphia; Raleigh-Durham, N.C.; and the San Francisco Bay Area are “hot areas.”

The breadth of “specialty” areas in industry for experienced clinicians is wide and includes: discovery, translational medicine, early- and late-stage clinical development, medical affairs, patient safety, epidemiology, and commercial development. For those interested in transitioning into industry, it is ideal to have a preferred area in mind so that training and education while in fellowship and clinical practice can be directed to that topic.

Discovery and translational medicine

These areas focus on preclinical development of small and large molecules from first concept until first-in-human studies and filing of an investigational new drug application (IND) with regulatory agencies. Translation of basic science concepts into potentially clinically useful “candidate” molecules requires a strong basic knowledge of science in addition to clinical experience. A passion for bridging novel concepts from “bench” to nonhuman studies is critical for success in this area.

Early-stage clinical development

Early-stage clinical development focuses on progressing discovery candidates to first-in-human studies (phase 1 in healthy volunteers) through phase 2 proof-of-concept studies (PoC). PoC studies typically involve first proof in a clinical trial in the target population that the drug under development may provide clinical benefit. These studies typically include 50-200 subjects with tight inclusion and exclusion controls. Intellectual rigor and scientific curiosity, as well as a passion for protecting patient safety, are essential for success as an early-stage drug developer.

Late-stage clinical development

Late-stage clinical development involves designing, conducting, and executing very large clinical studies (typically with hundreds to thousands of patients) that will provide the necessary rigorous pivotal clinical data supporting new drug marketing applications (NDAs). Relatively few drug candidates successfully make it to this stage of development and these studies are extremely expensive (sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars). This stage of development requires close collaboration with numerous company functions including regulatory, biostatistics, patient safety, clinical pharmacology, clinical operations, and manufacturing, as well as commercial colleagues. In addition to strong clinical expertise, this stage of drug development requires excellent communication, with leadership skills and attention to detail as well. Successfully shepherding a drug candidate through to Food and Drug Administration or other regulatory agency approval is an extremely satisfying experience, which can lead to meaningful differences for patients.

Medical affairs

This is a very important and challenging specialty area that, at its core, demands value demonstration of a medicine and communication to key stakeholders such as patients, physicians, and payers. This objective has become increasingly challenging over the past decade while evolving from a qualitative specialty to a rigorous quantitative one. Scientific and commercial success depends on efficient design, execution, and dissemination of results for real-world evidence and postapproval studies. Ideally, these data will demonstrate the medicine’s benefit-risk profile and how it fits into treatment algorithms. Communication requires leadership of physician and payer advisory boards, as well as publication planning. Close collaboration with marketing teams to advise on ethical and scientifically accurate promotional activities is another key component.

Patient safety

As the name implies, patient safety focuses on evaluating signals both from clinical trials and from literature that can accurately map out risks to patients that can arise from taking these medications. This is a critical function for proper and ethical prescription and use of medicine in today’s society. In addition to signal recognition and consultation with clinical development teams, collaboration with regulatory agencies is an important component.

Epidemiology

Epidemiologists with clinical expertise have become an increasingly important need for pharmaceutical and biotech companies over the past decade – specifically, for the design of real-world studies that demonstrate benefit-risk profiles for medicines in real-world use. These data are in demand for both private and governmental payers, as well as for regulatory agencies who are interested in evolving postapproval safety data. Successful epidemiologists often have acquired MPH degrees and expertise in study design and biostatistics.

Commercial development

Those with more financial or business acumen and clinical experience sometimes staff commercial careers. Typically commercial leads also have an MBA degree and are responsible for assessing commercial markets and forecasting and executing a path to commercial viability. Ultimately this career path can lead to a CEO position.

A career in industry is a perfect fit for some, but not so much for others. Table 1 outlines some pros and cons. Commercial factors do come into play with regard to corporate objectives and areas of focus. The top pharmaceutical product therapeutic categories, according to the number of drugs under development in 2017, were cancer, vaccines, diabetes, ophthalmology, gene therapy, anti-inflammatory, and antivirals and immunosuppressants; inflammatory bowel disease was 15th. Therapeutic research and development areas in gastroenterology that are relatively in demand in 2019 include IBD, irritable bowel syndrome, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. The high demand areas seem to change with the science and also payers’ willingness to reimburse.

Is industry a good career choice for you? Consider the following factors:

- Travel capabilities.

- Small biotech versus big pharma versus CRO.

- Capability to function in a team environment.

- Communication skills, resilience, self-awareness.

- Therapeutic area and category.

- Early stage versus late stage versus translational versus medical affairs.

- Additional education: MBA, MPH, PhD.

- Geography.

The pharmaceutical industry evolves and undergoes transformation extremely quickly in response to changes in the external environment. If you are considering a current or future career in industry, staying informed about changes in the delivery of health care and health economics is important. There is an ongoing need in industry for trainees and experienced gastroenterologists who can deploy their clinical expertise in development and communication of new medicines and devices that will make a positive difference in patients’ lives.

CPAP use associated with greater weight loss in obese patients with sleep apnea

NEW ORLEANS – Contrary to previously published data suggesting continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) produces weight gain in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), new study findings presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society provided data supporting the exact opposite conclusion.

“We think the data are strong enough to conclude that combining CPAP with a weight-loss program should be considered for all OSA patients. The weight-loss advantage is substantial,” reported Yuanjie Mao, MD, PhD, of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

Both weight loss and CPAP have been shown to be effective for the treatment of OSA, but concern that CPAP produces a counterproductive gain in weight was raised by findings in a meta-analysis in which CPAP was associated with increased body mass index (Thorax. 2015 Mar;70:258-64). As a result of that finding, some guidelines subsequently advised intensifying a weight-loss program at the time that CPAP is initiated to mitigate the weight gain effect, according to Dr. Mao. However, he noted that prospective data were never collected, so a causal relationship was never proven. Now, his data support the opposite conclusion.

In the more recent study, 300 patients who had participated in an intensive weight-loss program at his institution were divided into three groups: OSA patients who had been treated with CPAP, symptomatic OSA patients who had not been treated with CPAP, and asymptomatic OSA patients not treated with CPAP. They were compared retrospectively for weight change over a 16-week period.

“This was a very simple study,” said Dr. Mao, who explained that several exclusions, such as thyroid dysfunction, active infection, and uncontrolled diabetes, were used to reduce variables that might also affect weight change. At the end of 16 weeks, the median absolute weight loss in the CPAP group was 26.7 lb (12.1 kg), compared with 21 lb (9.5 kg) for the symptomatic OSA group and 19.2 lb (8.7 kg) for the asymptomatic OSA group. The weight loss was significantly greater for the CPAP group (P less than .01), compared with either of the other two groups, but not significantly different between the groups that were not treated with CPAP.

“The differences remained significant after adjusting for baseline BMI [body mass index], age, and gender,” Dr. Mao reported.

Asked why his data contradicted the previously reported data, Dr. Mao said that the previous studies were not evaluating CPAP in the context of a weight-loss program. He contends that when CPAP is combined with a rigorous weight-reduction regimen, there is an additive benefit from CPAP.

According to Dr. Mao, these data bring the value of CPAP for weight loss full circle. Before publication of the 2015 meta-analysis, it was widely assumed that CPAP helped with weight loss based on the expectation that better sleep quality would increase daytime activity. However, in the absence of strong data confirming that effect, Dr. Mao believes the unexpected results of the 2015 study easily pushed the pendulum in the opposite direction.

“The conclusion that CPAP increases weight was drawn from studies not designed to evaluate a weight-loss effect in those participating in a weight-loss program,” Dr. Mao explained. His study suggests that it is this combination that is important. He believes the observed effect from better sleep quality associated with CPAP is not necessarily related to better daytime function alone.

“Patients who sleep well also have more favorable diurnal changes in factors that might be important to weight change, such as leptin resistance and hormonal secretion,” he said. Although more work is needed to determine whether these purported mechanisms are important, he thinks his study has an immediate clinical message.

“Patients with OSA who are prescribed weight loss should also be considered for CPAP for the goal of weight loss,” Dr. Mao said. “We think this therapy should be started right away.”

SOURCE: Mao Y et al. ENDO 2019, Session SAT-095.

NEW ORLEANS – Contrary to previously published data suggesting continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) produces weight gain in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), new study findings presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society provided data supporting the exact opposite conclusion.

“We think the data are strong enough to conclude that combining CPAP with a weight-loss program should be considered for all OSA patients. The weight-loss advantage is substantial,” reported Yuanjie Mao, MD, PhD, of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

Both weight loss and CPAP have been shown to be effective for the treatment of OSA, but concern that CPAP produces a counterproductive gain in weight was raised by findings in a meta-analysis in which CPAP was associated with increased body mass index (Thorax. 2015 Mar;70:258-64). As a result of that finding, some guidelines subsequently advised intensifying a weight-loss program at the time that CPAP is initiated to mitigate the weight gain effect, according to Dr. Mao. However, he noted that prospective data were never collected, so a causal relationship was never proven. Now, his data support the opposite conclusion.

In the more recent study, 300 patients who had participated in an intensive weight-loss program at his institution were divided into three groups: OSA patients who had been treated with CPAP, symptomatic OSA patients who had not been treated with CPAP, and asymptomatic OSA patients not treated with CPAP. They were compared retrospectively for weight change over a 16-week period.

“This was a very simple study,” said Dr. Mao, who explained that several exclusions, such as thyroid dysfunction, active infection, and uncontrolled diabetes, were used to reduce variables that might also affect weight change. At the end of 16 weeks, the median absolute weight loss in the CPAP group was 26.7 lb (12.1 kg), compared with 21 lb (9.5 kg) for the symptomatic OSA group and 19.2 lb (8.7 kg) for the asymptomatic OSA group. The weight loss was significantly greater for the CPAP group (P less than .01), compared with either of the other two groups, but not significantly different between the groups that were not treated with CPAP.

“The differences remained significant after adjusting for baseline BMI [body mass index], age, and gender,” Dr. Mao reported.

Asked why his data contradicted the previously reported data, Dr. Mao said that the previous studies were not evaluating CPAP in the context of a weight-loss program. He contends that when CPAP is combined with a rigorous weight-reduction regimen, there is an additive benefit from CPAP.

According to Dr. Mao, these data bring the value of CPAP for weight loss full circle. Before publication of the 2015 meta-analysis, it was widely assumed that CPAP helped with weight loss based on the expectation that better sleep quality would increase daytime activity. However, in the absence of strong data confirming that effect, Dr. Mao believes the unexpected results of the 2015 study easily pushed the pendulum in the opposite direction.

“The conclusion that CPAP increases weight was drawn from studies not designed to evaluate a weight-loss effect in those participating in a weight-loss program,” Dr. Mao explained. His study suggests that it is this combination that is important. He believes the observed effect from better sleep quality associated with CPAP is not necessarily related to better daytime function alone.

“Patients who sleep well also have more favorable diurnal changes in factors that might be important to weight change, such as leptin resistance and hormonal secretion,” he said. Although more work is needed to determine whether these purported mechanisms are important, he thinks his study has an immediate clinical message.

“Patients with OSA who are prescribed weight loss should also be considered for CPAP for the goal of weight loss,” Dr. Mao said. “We think this therapy should be started right away.”

SOURCE: Mao Y et al. ENDO 2019, Session SAT-095.

NEW ORLEANS – Contrary to previously published data suggesting continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) produces weight gain in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), new study findings presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society provided data supporting the exact opposite conclusion.

“We think the data are strong enough to conclude that combining CPAP with a weight-loss program should be considered for all OSA patients. The weight-loss advantage is substantial,” reported Yuanjie Mao, MD, PhD, of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

Both weight loss and CPAP have been shown to be effective for the treatment of OSA, but concern that CPAP produces a counterproductive gain in weight was raised by findings in a meta-analysis in which CPAP was associated with increased body mass index (Thorax. 2015 Mar;70:258-64). As a result of that finding, some guidelines subsequently advised intensifying a weight-loss program at the time that CPAP is initiated to mitigate the weight gain effect, according to Dr. Mao. However, he noted that prospective data were never collected, so a causal relationship was never proven. Now, his data support the opposite conclusion.

In the more recent study, 300 patients who had participated in an intensive weight-loss program at his institution were divided into three groups: OSA patients who had been treated with CPAP, symptomatic OSA patients who had not been treated with CPAP, and asymptomatic OSA patients not treated with CPAP. They were compared retrospectively for weight change over a 16-week period.

“This was a very simple study,” said Dr. Mao, who explained that several exclusions, such as thyroid dysfunction, active infection, and uncontrolled diabetes, were used to reduce variables that might also affect weight change. At the end of 16 weeks, the median absolute weight loss in the CPAP group was 26.7 lb (12.1 kg), compared with 21 lb (9.5 kg) for the symptomatic OSA group and 19.2 lb (8.7 kg) for the asymptomatic OSA group. The weight loss was significantly greater for the CPAP group (P less than .01), compared with either of the other two groups, but not significantly different between the groups that were not treated with CPAP.

“The differences remained significant after adjusting for baseline BMI [body mass index], age, and gender,” Dr. Mao reported.

Asked why his data contradicted the previously reported data, Dr. Mao said that the previous studies were not evaluating CPAP in the context of a weight-loss program. He contends that when CPAP is combined with a rigorous weight-reduction regimen, there is an additive benefit from CPAP.

According to Dr. Mao, these data bring the value of CPAP for weight loss full circle. Before publication of the 2015 meta-analysis, it was widely assumed that CPAP helped with weight loss based on the expectation that better sleep quality would increase daytime activity. However, in the absence of strong data confirming that effect, Dr. Mao believes the unexpected results of the 2015 study easily pushed the pendulum in the opposite direction.

“The conclusion that CPAP increases weight was drawn from studies not designed to evaluate a weight-loss effect in those participating in a weight-loss program,” Dr. Mao explained. His study suggests that it is this combination that is important. He believes the observed effect from better sleep quality associated with CPAP is not necessarily related to better daytime function alone.

“Patients who sleep well also have more favorable diurnal changes in factors that might be important to weight change, such as leptin resistance and hormonal secretion,” he said. Although more work is needed to determine whether these purported mechanisms are important, he thinks his study has an immediate clinical message.

“Patients with OSA who are prescribed weight loss should also be considered for CPAP for the goal of weight loss,” Dr. Mao said. “We think this therapy should be started right away.”

SOURCE: Mao Y et al. ENDO 2019, Session SAT-095.

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2019

How to create your specialized niche in a private practice

Let’s imagine you landed your first job in a private gastroenterology practice or are trying to find the perfect job that allows you to put your energy toward your passions. And, like many GI doctors, you spent additional time in your fellowship training focusing on a specific interest – whether inflammatory bowel disease, advanced endoscopy, motility, hepatology, or maybe the lesser-traveled paths of weight management, geriatrics, or public policy.

Perhaps you haven’t taken an extra year of training, but you have a desire to specialize. What steps should you take to create your own niche in a private practice? How do you go about growing a practice that allows you to utilize your training?

Why specialize? Know your market!

Without a focus, unless you plan to work in an underserved area or to take over a retiring physician’s practice, a generalist position can be challenging because the demand for your skills may not be met with the supply of patients. Much like in any business, the more focused you are, the more you have a differentiator that separates you from your colleagues, increasing your chances of success.

With specialization, however, comes the importance of understanding your patient catchment area. If your focus is highly specialized and serves a less-diagnosed entity, you’ll need a larger catchment area or you won’t have the volume of patients. Also, be mindful about an oversupply of subspecialists in your given area. If you are the third or fourth subspecialist in your group, the only way you will get patients is if you are far superior in talent or personality (sorry – not typical!) or your more senior colleagues are looking to turn over work to you.

Economic considerations for subspecialties

Compensation for subspecializing is often a major factor. Understanding the economics of your specialty are important, as providers can become disappointed and disenchanted when they realize that their desire for income, especially when compared to other colleagues, differs from what their subspecialty can provide.

For instance, in GI, a physician pursuing a procedurally focused subspecialty like advanced endoscopy is likely to be compensated more highly than one who focuses on a more office-based, evaluation and management (E/M) billing-driven specialty, like motility, geriatric gastroenterology, or even hepatology. These office-based specialties are no less important, but the reality is that they create less revenue for a private practice.

Negotiating a fair contract at the beginning is critical, as you may need your income to be supplemented by your higher revenue-producing colleagues and partners for long-term success. Academic centers are often able to provide the supplement through endowments, grants, or better payer reimbursement for E/M codes, compared with a private practice.

Remember, everyone’s in sales

From my vantage point as a partner at Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates, there are several ways new GI physicians can set about a path toward specialization.

One of the first things that you should ask yourself during training is whether you want to spend another year beyond the typical 3 years. Best-case scenario would be figuring out a way to get the necessary training during the 3 years, possibly spending the third year dedicated to the specialty. Another possibility is to simply get on-the-job training during your first few years in practice without the extra year.

Whichever path you choose, building up a specialized niche within a private practice won’t come overnight. You have to create a plan and navigate a course. Here are a few ways to do that:

Take the case, especially the hard ones!

Have the mentality: “I will take care of it.” One of the best ways to specialize is to offer to help with all cases, but especially the most challenging ones. Be open to helping take on any patient. In the beginning, if you develop a reputation that you enjoy caring for all patients, even when the case requires more time and effort, this will translate into future referrals. Naturally, it may be slower in the beginning, as there may not be enough patients to treat within your specialty. Being willing to do everything will expedite the growth of your practice. No consult should be rebuffed, even when it appears unnecessary (i.e., heme-positive stool in an elderly, septic ICU patient – we all have gotten them); think of it as your opportunity to show off your skills and share your interests.

Market yourself.

This is perhaps one of the most important steps you can take. Get out in the community! This includes:

- Attend your hospital grand rounds and offer to be a presenter. There is no better way to show your enthusiasm and knowledge on a topic than to teach it. Many state GI societies have meetings, which provide opportunities to introduce yourself to physicians in other practices that can act as a good referral source if you are a local expert.

- Remember, as a subspecialist, always communicate back with the primary gastroenterologist. In doing so, feel out whether the referring doctor wants you to take over the patient’s management or send the patient back.

- Reach out to foundations, pharmaceutical companies, and advocacy groups in the area. Understand each specialty has an ecosystem beyond just a doctor-patient relationship. Participating in events that support the patient outside of the office will provide goodwill. Further, many patients rely on foundations for referrals.

- Consider research studies. Many pharmaceutical companies have the opportunity for you to register patients in investigational drug studies. By being a part of these studies, you will be included in publications, which will build your brand.

- Many disease processes need a multidisciplinary approach to treating them. Attending multidisciplinary conferences will allow you to lend your expertise. Also, presenting interesting cases and asking for help from more experienced physicians will show humility and leads to more referrals; it won’t be viewed as a weakness.

- Be creative. Develop relationships with providers who are not often considered to be a primary referral source. Motility experts may want to work closely with the local speech pathologists. An IBD specialist should develop a network of specialists for patients with extraintestinal manifestations. Advanced endoscopists and oncologists work closely together.

- Get involved in social media. Engage with other specialists and become part of the online community. Follow the subspecialty organizations or key thought leaders in your space on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn. You should share relevant articles or interesting cases.

There are so many aspects of gastroenterology that present great opportunities to specialize. Following your passions will lead to long-term happiness and prevent burnout. Remember that, even once you’ve built your practice, you must continue to stay involved and nurture what you’ve built. Go to the conferences. Make connections. Continue your education. Your career will thank you.

Dr. Sonenshine joined Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates in 2012. An Atlanta native, he graduated magna cum laude from the University of Georgia in Athens where he received a bachelor’s degree in microbiology and was selected to the Phi Beta Kappa Academic Honor Society. He received his medical degree from the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta, where he was named to the Alpha Omega Alpha Medical Honor Society. He completed both his internship and residency through the Osler Housestaff Training Program at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. Following his residency, Dr. Sonenshine completed a fellowship in digestive diseases at Emory University in Atlanta while earning a master of business administration degree from the Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia. He is a partner in United Digestive and the chairman of medicine at Northside Hospital.

Let’s imagine you landed your first job in a private gastroenterology practice or are trying to find the perfect job that allows you to put your energy toward your passions. And, like many GI doctors, you spent additional time in your fellowship training focusing on a specific interest – whether inflammatory bowel disease, advanced endoscopy, motility, hepatology, or maybe the lesser-traveled paths of weight management, geriatrics, or public policy.