User login

Patient Navigators for Serious Illnesses Can Now Bill Under New Medicare Codes

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Improving Colorectal Cancer Screening via Mailed Fecal Immunochemical Testing in a Veterans Affairs Health System

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common cancers and causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States.1 Reflective of a nationwide trend, CRC screening rates at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2-5 Contributing factors to this decrease included cancellations of elective colonoscopies during the initial phase of the pandemic and concurrent turnover of endoscopists. In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force lowered the recommended initial CRC screening age from 50 years to 45 years, further increasing the backlog of unscreened patients.6

Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is a noninvasive screening method in which antibodies are used to detect hemoglobin in the stool. The sensitivity and specificity of 1-time FIT are 79% to 80% and 94%, respectively, for the detection of CRC, with sensitivity improving with successive testing.7,8 Annual FIT is recognized as a tier 1 preferred screening method by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.7,9 Programs that mail FIT kits to eligible patients outside of physician visits have been successfully implemented in health care systems.10,11

The VACHS designed and implemented a mailed FIT program using existing infrastructure and staffing.

Program Description

A team of local stakeholders comprised of VACHS leadership, primary care, nursing, and gastroenterology staff, as well as representatives from laboratory, informatics, mail services, and group practice management, was established to execute the project. The team met monthly to plan the project.

The team developed a dataset consisting of patients aged 45 to 75 years who were at average risk for CRC and due for CRC screening. Patients were defined as due for CRC screening if they had not had a colonoscopy in the previous 9 years or a FIT or fecal occult blood test in the previous 11 months. Average risk for CRC was defined by excluding patients with associated diagnosis codes for CRC, colectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, and anemia. The program also excluded patients with diagnosis codes associated with dementia, deferring discussions about cancer screening to their primary care practitioners (PCPs). Patients with invalid mailing addresses were also excluded, as well as those whose PCPs had indicated in the electronic health record that the patient received CRC screening outside the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system.

Letter Templates

Two patient letter electronic health record templates were developed. The first was a primer letter, which was mailed to patients 2 to 3 weeks before the mailed FIT kit as an introduction to the program.12 The purpose of the primer letter was to give advance notice to patients that they could expect a FIT kit to arrive in the mail. The goal was to prepare patients to complete FIT when the kit arrived and prompt them to call the VA to opt out of the mailed FIT program if they were up to date with CRC screening or if they had a condition which made them at high risk for CRC.

The second FIT letter arrived with the FIT kit, introduced FIT and described the importance of CRC screening. The letter detailed instructions for completing FIT and automatically created a FIT order. It also included a list of common conditions that may exclude patients, with a recommendation for patients to contact their medical team if they felt they were not candidates for FIT.

Staff Education

A previous VACHS pilot project demonstrated the success of a mailed FIT program to increase FIT use. Implemented as part of the pilot program, staff education consisted of a session for clinicians about the role of FIT in CRC screening and an all-staff education session. An additional education session about CRC and FIT for all staff was repeated with the program launch.

Program Launch

The mailed FIT program was introduced during a VACHS primary care all-staff meeting. After the meeting, each patient aligned care team (PACT) received an encrypted email that included a list of the patients on their team who were candidates for the program, a patient-facing FIT instruction sheet, detailed instructions on how to send the FIT primer letter, and a FIT package consisting of the labeled FIT kit, FIT letter, and patient instruction sheet. A reminder letter was sent to each patient 3 weeks after the FIT package was mailed. The patient lists were populated into a shared, encrypted Microsoft Teams folder that was edited in real time by PACT teams and viewed by VACHS leadership to track progress.

Program Metrics

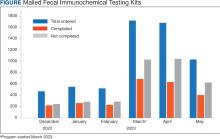

At program launch, the VACHS had 4642 patients due for CRC screening who were eligible for the mailed FIT program. On March 7, 2023, the data consisting of FIT tests ordered between December 2022 and May 2023—3 months before and after the launch of the program—were reviewed and categorized. In the 3 months before program launch, 1528 FIT were ordered and 714 were returned (46.7%). In the 3 months after the launch of the program, 4383 FIT were ordered and 1712 were returned (39.1%) (Figure). Test orders increased 287% from the preintervention to the postintervention period. The mean (SD) number of monthly FIT tests prelaunch was 509 (32.7), which increased to 1461 (331.6) postlaunch.

At the VACHS, 61.4% of patients aged 45 to 75 years were up to date with CRC screening before the program launch. In the 3 months after program launch, the rate increased to 63.8% among patients aged 45 to 75 years, the highest rate in our Veterans Integrated Services Network and exceeding the VA national average CRC screening rate, according to unpublished VA Monthly Management Report data.

In the 3 months following the program launch, 139 FIT kits tested positive for potential CRC. Of these, 79 (56.8%) patients had completed a diagnostic colonoscopy. PACT PCPs and nurses received reports on patients with positive FIT tests and those with no colonoscopy scheduled or completed and were asked to follow up.

Discussion

Through a proactive, population-based CRC screening program centered on mailed FIT kits outside of the traditional patient visit, the VACHS increased the use of FIT and rates of CRC screening. The numbers of FIT kits ordered and completed substantially increased in the 3 months after program launch.

Compared to mailed FIT programs described in the literature that rely on centralized processes in that a separate team operates the mailed FIT program for the entire organization, this program used existing PACT infrastructure and staff.10,11 This strategy allowed VACHS to design and implement the program in several months. Not needing to hire new staff or create a central team for the sole purpose of implementing the program allowed us to save on any organizational funding and efforts that would have accompanied the additional staff. The program described in this article may be more attainable for primary care practices or smaller health systems that do not have the capacity for the creation of a centralized process.

Limitations

Although the total number of FIT completions substantially increased during the program, the rate of FIT completion during the mailed FIT program was lower than the rate of completion prior to program launch. This decreased rate of FIT kit completion may be related to separation from a patient visit and potential loss of real-time education with a clinician. The program’s decentralized design increased the existing workload for primary care staff, and as a result, consideration must be given to local staffing levels. Additionally, the report of eligible patients depended on diagnosis codes and may have captured patients with higher-than-average risk of CRC, such as patients with prior history of adenomatous polyps, family history of CRC, or other medical or genetic conditions. We attempted to mitigate this by including a list of conditions that would exclude patients from FIT eligibility in the FIT letter and giving them the option to opt out.

Conclusions

CRC screening rates improved following implementation of a primary care team-centered quality improvement process to proactively identify patients appropriate for FIT and mail them FIT kits. This project highlights that population-health interventions around CRC screening via use of FIT can be successful within a primary care patient-centered medical home model, considering the increases in both CRC screening rates and increase in FIT tests ordered.

1. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for colorectal cancer. Revised January 29, 2024. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

2. Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Katz AJ. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(6):878-884. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884

3. Mazidimoradi A, Tiznobaik A, Salehiniya H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022;53(3):730-744. doi:10.1007/s12029-021-00679-x

4. Adams MA, Kurlander JE, Gao Y, Yankey N, Saini SD. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on screening colonoscopy utilization in a large integrated health system. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(7):2098-2100.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.034

5. Sundaram S, Olson S, Sharma P, Rajendra S. A review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: implications and solutions. Pathogens. 2021;10(11):558. doi:10.3390/pathogens10111508

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

7. Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(1):2-21.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.025

8. Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, Levin TR, Corley DA. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(3):171. doi:10.7326/M13-1484

9. Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):307-323. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.013

10. Deeds SA, Moore CB, Gunnink EJ, et al. Implementation of a mailed faecal immunochemical test programme for colorectal cancer screening among veterans. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11(4):e001927. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001927

11. Selby K, Jensen CD, Levin TR, et al. Program components and results from an organized colorectal cancer screening program using annual fecal immunochemical testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):145-152. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.042

12. Deeds S, Liu T, Schuttner L, et al. A postcard primer prior to mailed fecal immunochemical test among veterans: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2023:38(14):3235-3241. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08248-7

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common cancers and causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States.1 Reflective of a nationwide trend, CRC screening rates at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2-5 Contributing factors to this decrease included cancellations of elective colonoscopies during the initial phase of the pandemic and concurrent turnover of endoscopists. In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force lowered the recommended initial CRC screening age from 50 years to 45 years, further increasing the backlog of unscreened patients.6

Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is a noninvasive screening method in which antibodies are used to detect hemoglobin in the stool. The sensitivity and specificity of 1-time FIT are 79% to 80% and 94%, respectively, for the detection of CRC, with sensitivity improving with successive testing.7,8 Annual FIT is recognized as a tier 1 preferred screening method by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.7,9 Programs that mail FIT kits to eligible patients outside of physician visits have been successfully implemented in health care systems.10,11

The VACHS designed and implemented a mailed FIT program using existing infrastructure and staffing.

Program Description

A team of local stakeholders comprised of VACHS leadership, primary care, nursing, and gastroenterology staff, as well as representatives from laboratory, informatics, mail services, and group practice management, was established to execute the project. The team met monthly to plan the project.

The team developed a dataset consisting of patients aged 45 to 75 years who were at average risk for CRC and due for CRC screening. Patients were defined as due for CRC screening if they had not had a colonoscopy in the previous 9 years or a FIT or fecal occult blood test in the previous 11 months. Average risk for CRC was defined by excluding patients with associated diagnosis codes for CRC, colectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, and anemia. The program also excluded patients with diagnosis codes associated with dementia, deferring discussions about cancer screening to their primary care practitioners (PCPs). Patients with invalid mailing addresses were also excluded, as well as those whose PCPs had indicated in the electronic health record that the patient received CRC screening outside the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system.

Letter Templates

Two patient letter electronic health record templates were developed. The first was a primer letter, which was mailed to patients 2 to 3 weeks before the mailed FIT kit as an introduction to the program.12 The purpose of the primer letter was to give advance notice to patients that they could expect a FIT kit to arrive in the mail. The goal was to prepare patients to complete FIT when the kit arrived and prompt them to call the VA to opt out of the mailed FIT program if they were up to date with CRC screening or if they had a condition which made them at high risk for CRC.

The second FIT letter arrived with the FIT kit, introduced FIT and described the importance of CRC screening. The letter detailed instructions for completing FIT and automatically created a FIT order. It also included a list of common conditions that may exclude patients, with a recommendation for patients to contact their medical team if they felt they were not candidates for FIT.

Staff Education

A previous VACHS pilot project demonstrated the success of a mailed FIT program to increase FIT use. Implemented as part of the pilot program, staff education consisted of a session for clinicians about the role of FIT in CRC screening and an all-staff education session. An additional education session about CRC and FIT for all staff was repeated with the program launch.

Program Launch

The mailed FIT program was introduced during a VACHS primary care all-staff meeting. After the meeting, each patient aligned care team (PACT) received an encrypted email that included a list of the patients on their team who were candidates for the program, a patient-facing FIT instruction sheet, detailed instructions on how to send the FIT primer letter, and a FIT package consisting of the labeled FIT kit, FIT letter, and patient instruction sheet. A reminder letter was sent to each patient 3 weeks after the FIT package was mailed. The patient lists were populated into a shared, encrypted Microsoft Teams folder that was edited in real time by PACT teams and viewed by VACHS leadership to track progress.

Program Metrics

At program launch, the VACHS had 4642 patients due for CRC screening who were eligible for the mailed FIT program. On March 7, 2023, the data consisting of FIT tests ordered between December 2022 and May 2023—3 months before and after the launch of the program—were reviewed and categorized. In the 3 months before program launch, 1528 FIT were ordered and 714 were returned (46.7%). In the 3 months after the launch of the program, 4383 FIT were ordered and 1712 were returned (39.1%) (Figure). Test orders increased 287% from the preintervention to the postintervention period. The mean (SD) number of monthly FIT tests prelaunch was 509 (32.7), which increased to 1461 (331.6) postlaunch.

At the VACHS, 61.4% of patients aged 45 to 75 years were up to date with CRC screening before the program launch. In the 3 months after program launch, the rate increased to 63.8% among patients aged 45 to 75 years, the highest rate in our Veterans Integrated Services Network and exceeding the VA national average CRC screening rate, according to unpublished VA Monthly Management Report data.

In the 3 months following the program launch, 139 FIT kits tested positive for potential CRC. Of these, 79 (56.8%) patients had completed a diagnostic colonoscopy. PACT PCPs and nurses received reports on patients with positive FIT tests and those with no colonoscopy scheduled or completed and were asked to follow up.

Discussion

Through a proactive, population-based CRC screening program centered on mailed FIT kits outside of the traditional patient visit, the VACHS increased the use of FIT and rates of CRC screening. The numbers of FIT kits ordered and completed substantially increased in the 3 months after program launch.

Compared to mailed FIT programs described in the literature that rely on centralized processes in that a separate team operates the mailed FIT program for the entire organization, this program used existing PACT infrastructure and staff.10,11 This strategy allowed VACHS to design and implement the program in several months. Not needing to hire new staff or create a central team for the sole purpose of implementing the program allowed us to save on any organizational funding and efforts that would have accompanied the additional staff. The program described in this article may be more attainable for primary care practices or smaller health systems that do not have the capacity for the creation of a centralized process.

Limitations

Although the total number of FIT completions substantially increased during the program, the rate of FIT completion during the mailed FIT program was lower than the rate of completion prior to program launch. This decreased rate of FIT kit completion may be related to separation from a patient visit and potential loss of real-time education with a clinician. The program’s decentralized design increased the existing workload for primary care staff, and as a result, consideration must be given to local staffing levels. Additionally, the report of eligible patients depended on diagnosis codes and may have captured patients with higher-than-average risk of CRC, such as patients with prior history of adenomatous polyps, family history of CRC, or other medical or genetic conditions. We attempted to mitigate this by including a list of conditions that would exclude patients from FIT eligibility in the FIT letter and giving them the option to opt out.

Conclusions

CRC screening rates improved following implementation of a primary care team-centered quality improvement process to proactively identify patients appropriate for FIT and mail them FIT kits. This project highlights that population-health interventions around CRC screening via use of FIT can be successful within a primary care patient-centered medical home model, considering the increases in both CRC screening rates and increase in FIT tests ordered.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common cancers and causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States.1 Reflective of a nationwide trend, CRC screening rates at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2-5 Contributing factors to this decrease included cancellations of elective colonoscopies during the initial phase of the pandemic and concurrent turnover of endoscopists. In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force lowered the recommended initial CRC screening age from 50 years to 45 years, further increasing the backlog of unscreened patients.6

Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is a noninvasive screening method in which antibodies are used to detect hemoglobin in the stool. The sensitivity and specificity of 1-time FIT are 79% to 80% and 94%, respectively, for the detection of CRC, with sensitivity improving with successive testing.7,8 Annual FIT is recognized as a tier 1 preferred screening method by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.7,9 Programs that mail FIT kits to eligible patients outside of physician visits have been successfully implemented in health care systems.10,11

The VACHS designed and implemented a mailed FIT program using existing infrastructure and staffing.

Program Description

A team of local stakeholders comprised of VACHS leadership, primary care, nursing, and gastroenterology staff, as well as representatives from laboratory, informatics, mail services, and group practice management, was established to execute the project. The team met monthly to plan the project.

The team developed a dataset consisting of patients aged 45 to 75 years who were at average risk for CRC and due for CRC screening. Patients were defined as due for CRC screening if they had not had a colonoscopy in the previous 9 years or a FIT or fecal occult blood test in the previous 11 months. Average risk for CRC was defined by excluding patients with associated diagnosis codes for CRC, colectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, and anemia. The program also excluded patients with diagnosis codes associated with dementia, deferring discussions about cancer screening to their primary care practitioners (PCPs). Patients with invalid mailing addresses were also excluded, as well as those whose PCPs had indicated in the electronic health record that the patient received CRC screening outside the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system.

Letter Templates

Two patient letter electronic health record templates were developed. The first was a primer letter, which was mailed to patients 2 to 3 weeks before the mailed FIT kit as an introduction to the program.12 The purpose of the primer letter was to give advance notice to patients that they could expect a FIT kit to arrive in the mail. The goal was to prepare patients to complete FIT when the kit arrived and prompt them to call the VA to opt out of the mailed FIT program if they were up to date with CRC screening or if they had a condition which made them at high risk for CRC.

The second FIT letter arrived with the FIT kit, introduced FIT and described the importance of CRC screening. The letter detailed instructions for completing FIT and automatically created a FIT order. It also included a list of common conditions that may exclude patients, with a recommendation for patients to contact their medical team if they felt they were not candidates for FIT.

Staff Education

A previous VACHS pilot project demonstrated the success of a mailed FIT program to increase FIT use. Implemented as part of the pilot program, staff education consisted of a session for clinicians about the role of FIT in CRC screening and an all-staff education session. An additional education session about CRC and FIT for all staff was repeated with the program launch.

Program Launch

The mailed FIT program was introduced during a VACHS primary care all-staff meeting. After the meeting, each patient aligned care team (PACT) received an encrypted email that included a list of the patients on their team who were candidates for the program, a patient-facing FIT instruction sheet, detailed instructions on how to send the FIT primer letter, and a FIT package consisting of the labeled FIT kit, FIT letter, and patient instruction sheet. A reminder letter was sent to each patient 3 weeks after the FIT package was mailed. The patient lists were populated into a shared, encrypted Microsoft Teams folder that was edited in real time by PACT teams and viewed by VACHS leadership to track progress.

Program Metrics

At program launch, the VACHS had 4642 patients due for CRC screening who were eligible for the mailed FIT program. On March 7, 2023, the data consisting of FIT tests ordered between December 2022 and May 2023—3 months before and after the launch of the program—were reviewed and categorized. In the 3 months before program launch, 1528 FIT were ordered and 714 were returned (46.7%). In the 3 months after the launch of the program, 4383 FIT were ordered and 1712 were returned (39.1%) (Figure). Test orders increased 287% from the preintervention to the postintervention period. The mean (SD) number of monthly FIT tests prelaunch was 509 (32.7), which increased to 1461 (331.6) postlaunch.

At the VACHS, 61.4% of patients aged 45 to 75 years were up to date with CRC screening before the program launch. In the 3 months after program launch, the rate increased to 63.8% among patients aged 45 to 75 years, the highest rate in our Veterans Integrated Services Network and exceeding the VA national average CRC screening rate, according to unpublished VA Monthly Management Report data.

In the 3 months following the program launch, 139 FIT kits tested positive for potential CRC. Of these, 79 (56.8%) patients had completed a diagnostic colonoscopy. PACT PCPs and nurses received reports on patients with positive FIT tests and those with no colonoscopy scheduled or completed and were asked to follow up.

Discussion

Through a proactive, population-based CRC screening program centered on mailed FIT kits outside of the traditional patient visit, the VACHS increased the use of FIT and rates of CRC screening. The numbers of FIT kits ordered and completed substantially increased in the 3 months after program launch.

Compared to mailed FIT programs described in the literature that rely on centralized processes in that a separate team operates the mailed FIT program for the entire organization, this program used existing PACT infrastructure and staff.10,11 This strategy allowed VACHS to design and implement the program in several months. Not needing to hire new staff or create a central team for the sole purpose of implementing the program allowed us to save on any organizational funding and efforts that would have accompanied the additional staff. The program described in this article may be more attainable for primary care practices or smaller health systems that do not have the capacity for the creation of a centralized process.

Limitations

Although the total number of FIT completions substantially increased during the program, the rate of FIT completion during the mailed FIT program was lower than the rate of completion prior to program launch. This decreased rate of FIT kit completion may be related to separation from a patient visit and potential loss of real-time education with a clinician. The program’s decentralized design increased the existing workload for primary care staff, and as a result, consideration must be given to local staffing levels. Additionally, the report of eligible patients depended on diagnosis codes and may have captured patients with higher-than-average risk of CRC, such as patients with prior history of adenomatous polyps, family history of CRC, or other medical or genetic conditions. We attempted to mitigate this by including a list of conditions that would exclude patients from FIT eligibility in the FIT letter and giving them the option to opt out.

Conclusions

CRC screening rates improved following implementation of a primary care team-centered quality improvement process to proactively identify patients appropriate for FIT and mail them FIT kits. This project highlights that population-health interventions around CRC screening via use of FIT can be successful within a primary care patient-centered medical home model, considering the increases in both CRC screening rates and increase in FIT tests ordered.

1. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for colorectal cancer. Revised January 29, 2024. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

2. Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Katz AJ. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(6):878-884. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884

3. Mazidimoradi A, Tiznobaik A, Salehiniya H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022;53(3):730-744. doi:10.1007/s12029-021-00679-x

4. Adams MA, Kurlander JE, Gao Y, Yankey N, Saini SD. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on screening colonoscopy utilization in a large integrated health system. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(7):2098-2100.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.034

5. Sundaram S, Olson S, Sharma P, Rajendra S. A review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: implications and solutions. Pathogens. 2021;10(11):558. doi:10.3390/pathogens10111508

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

7. Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(1):2-21.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.025

8. Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, Levin TR, Corley DA. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(3):171. doi:10.7326/M13-1484

9. Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):307-323. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.013

10. Deeds SA, Moore CB, Gunnink EJ, et al. Implementation of a mailed faecal immunochemical test programme for colorectal cancer screening among veterans. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11(4):e001927. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001927

11. Selby K, Jensen CD, Levin TR, et al. Program components and results from an organized colorectal cancer screening program using annual fecal immunochemical testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):145-152. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.042

12. Deeds S, Liu T, Schuttner L, et al. A postcard primer prior to mailed fecal immunochemical test among veterans: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2023:38(14):3235-3241. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08248-7

1. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for colorectal cancer. Revised January 29, 2024. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

2. Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Katz AJ. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(6):878-884. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884

3. Mazidimoradi A, Tiznobaik A, Salehiniya H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022;53(3):730-744. doi:10.1007/s12029-021-00679-x

4. Adams MA, Kurlander JE, Gao Y, Yankey N, Saini SD. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on screening colonoscopy utilization in a large integrated health system. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(7):2098-2100.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.034

5. Sundaram S, Olson S, Sharma P, Rajendra S. A review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: implications and solutions. Pathogens. 2021;10(11):558. doi:10.3390/pathogens10111508

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

7. Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(1):2-21.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.025

8. Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, Levin TR, Corley DA. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(3):171. doi:10.7326/M13-1484

9. Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):307-323. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.013

10. Deeds SA, Moore CB, Gunnink EJ, et al. Implementation of a mailed faecal immunochemical test programme for colorectal cancer screening among veterans. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11(4):e001927. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001927

11. Selby K, Jensen CD, Levin TR, et al. Program components and results from an organized colorectal cancer screening program using annual fecal immunochemical testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):145-152. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.042

12. Deeds S, Liu T, Schuttner L, et al. A postcard primer prior to mailed fecal immunochemical test among veterans: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2023:38(14):3235-3241. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08248-7

Follow our continuing CROI coverage

Keep up to date with the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections home page for the latest in ID Practitioner's continuing reporting from the CROI meeting and our follow-ups afterward. You can also check out our archival coverage from last year's meeting.

Keep up to date with the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections home page for the latest in ID Practitioner's continuing reporting from the CROI meeting and our follow-ups afterward. You can also check out our archival coverage from last year's meeting.

Keep up to date with the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections home page for the latest in ID Practitioner's continuing reporting from the CROI meeting and our follow-ups afterward. You can also check out our archival coverage from last year's meeting.

New SVS Task Force Explores Vascular Certification Program

The Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) executive board has established a task force to explore developing a vascular certification program for inpatient and outpatient care settings.

Noting the shift in professional reimbursement from payment for volume to payment for quality, along with a surge in outpatient endovascular care, “The SVS executive board believes that it is a critical time for vascular surgery to set standards based on quality improvement, efficiency and appropriateness,” said Dr. R. Clement Darling III, SVS president.

Task force chair Dr. Tony Sidawy will oversee two subcommittees, one for inpatient and one for office-based endovascular care (OBEC). Dr. Krishna Jain has been appointed chair of the OBEC subcommittee. A chair for the inpatient subcommittee has yet to be named.

“Vascular surgeons represented by the SVS should take the lead in defining quality and value standards for vascular care before they are defined for us,” said Dr. Sidawy.

“Offering an SVS-led certification process will inspire the most appropriate, high-quality vascular care and optimal outcomes for all patients,” Dr. Jain added.

Many SVS members are pioneers in the design and delivery of care in office-based practice settings, and they have been fierce advocates for this effort, said Dr. Darling. “We have heard our members loud and clear. They want SVS to play a major role in shaping the future of the office-based endovascular center, setting the bar for appropriateness and quality and helping all practitioners achieve it.

“We feel that to provide the best vascular care in a data-driven, quality-based system, the SVS needs to be actively involved in this process," he added. "Vascular surgeons have a long history of making data-driven decisions about which patients need an intervention, and since we treat patients medically as well as by endovascular or open techniques, we have a unique perspective."

A data registry is a critical component and will be provided by the SVS Patient Safety Organization and Vascular Quality Initiative (SVS VQI). VQI registries are already used in more than 430 vascular care settings, ranging from academic to community practice. VQI data can be used to benchmark performance and improve the quality of vascular care.

“Given that the SVS VQI has already been adopted by all types of facilities, including OBECs and vein centers, the SVS VQI is well positioned to help assess and improve quality of care,” said Dr. Jens Eldrup-Jorgensen, SVS PSO medical director.

The process will include discussions and potential collaboration with partners such as the American College of Surgeons, the Outpatient Endovascular and Interventional Society and the Intersociety Accreditation Council, Dr. Darling said, as well as societies such as the American Venous Forum, the Society for Vascular Ultrasound, and the Society for Vascular Nursing.

If established, a pilot program would be launched in 2018 with a full launch planned in 2019.

The Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) executive board has established a task force to explore developing a vascular certification program for inpatient and outpatient care settings.

Noting the shift in professional reimbursement from payment for volume to payment for quality, along with a surge in outpatient endovascular care, “The SVS executive board believes that it is a critical time for vascular surgery to set standards based on quality improvement, efficiency and appropriateness,” said Dr. R. Clement Darling III, SVS president.

Task force chair Dr. Tony Sidawy will oversee two subcommittees, one for inpatient and one for office-based endovascular care (OBEC). Dr. Krishna Jain has been appointed chair of the OBEC subcommittee. A chair for the inpatient subcommittee has yet to be named.

“Vascular surgeons represented by the SVS should take the lead in defining quality and value standards for vascular care before they are defined for us,” said Dr. Sidawy.

“Offering an SVS-led certification process will inspire the most appropriate, high-quality vascular care and optimal outcomes for all patients,” Dr. Jain added.

Many SVS members are pioneers in the design and delivery of care in office-based practice settings, and they have been fierce advocates for this effort, said Dr. Darling. “We have heard our members loud and clear. They want SVS to play a major role in shaping the future of the office-based endovascular center, setting the bar for appropriateness and quality and helping all practitioners achieve it.

“We feel that to provide the best vascular care in a data-driven, quality-based system, the SVS needs to be actively involved in this process," he added. "Vascular surgeons have a long history of making data-driven decisions about which patients need an intervention, and since we treat patients medically as well as by endovascular or open techniques, we have a unique perspective."

A data registry is a critical component and will be provided by the SVS Patient Safety Organization and Vascular Quality Initiative (SVS VQI). VQI registries are already used in more than 430 vascular care settings, ranging from academic to community practice. VQI data can be used to benchmark performance and improve the quality of vascular care.

“Given that the SVS VQI has already been adopted by all types of facilities, including OBECs and vein centers, the SVS VQI is well positioned to help assess and improve quality of care,” said Dr. Jens Eldrup-Jorgensen, SVS PSO medical director.

The process will include discussions and potential collaboration with partners such as the American College of Surgeons, the Outpatient Endovascular and Interventional Society and the Intersociety Accreditation Council, Dr. Darling said, as well as societies such as the American Venous Forum, the Society for Vascular Ultrasound, and the Society for Vascular Nursing.

If established, a pilot program would be launched in 2018 with a full launch planned in 2019.

The Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) executive board has established a task force to explore developing a vascular certification program for inpatient and outpatient care settings.

Noting the shift in professional reimbursement from payment for volume to payment for quality, along with a surge in outpatient endovascular care, “The SVS executive board believes that it is a critical time for vascular surgery to set standards based on quality improvement, efficiency and appropriateness,” said Dr. R. Clement Darling III, SVS president.

Task force chair Dr. Tony Sidawy will oversee two subcommittees, one for inpatient and one for office-based endovascular care (OBEC). Dr. Krishna Jain has been appointed chair of the OBEC subcommittee. A chair for the inpatient subcommittee has yet to be named.

“Vascular surgeons represented by the SVS should take the lead in defining quality and value standards for vascular care before they are defined for us,” said Dr. Sidawy.

“Offering an SVS-led certification process will inspire the most appropriate, high-quality vascular care and optimal outcomes for all patients,” Dr. Jain added.

Many SVS members are pioneers in the design and delivery of care in office-based practice settings, and they have been fierce advocates for this effort, said Dr. Darling. “We have heard our members loud and clear. They want SVS to play a major role in shaping the future of the office-based endovascular center, setting the bar for appropriateness and quality and helping all practitioners achieve it.

“We feel that to provide the best vascular care in a data-driven, quality-based system, the SVS needs to be actively involved in this process," he added. "Vascular surgeons have a long history of making data-driven decisions about which patients need an intervention, and since we treat patients medically as well as by endovascular or open techniques, we have a unique perspective."

A data registry is a critical component and will be provided by the SVS Patient Safety Organization and Vascular Quality Initiative (SVS VQI). VQI registries are already used in more than 430 vascular care settings, ranging from academic to community practice. VQI data can be used to benchmark performance and improve the quality of vascular care.

“Given that the SVS VQI has already been adopted by all types of facilities, including OBECs and vein centers, the SVS VQI is well positioned to help assess and improve quality of care,” said Dr. Jens Eldrup-Jorgensen, SVS PSO medical director.

The process will include discussions and potential collaboration with partners such as the American College of Surgeons, the Outpatient Endovascular and Interventional Society and the Intersociety Accreditation Council, Dr. Darling said, as well as societies such as the American Venous Forum, the Society for Vascular Ultrasound, and the Society for Vascular Nursing.

If established, a pilot program would be launched in 2018 with a full launch planned in 2019.

VA Choice Bill Defeated in the House

A U.S. House of Representatives appropriation to fund the Veterans Choice Program surprisingly went down to defeat on Monday. The VA Choice Program is set to run out of money in September, and VA officials have been calling for Congress to provide additional funding for the program. Republican leaders, hoping to expedite the bill’s passage and thinking that it was not controversial, submitted the bill in a process that required the votes of two-thirds of the representatives. The 219-186 vote fell well short of the necessary two-thirds, and voting fell largely along party lines.

Many veterans service organizations (VSOs) were critical of the bill and called on the House to make substantial changes to it. Seven VSOs signed a joint statement calling for the bill’s defeat. “As organizations who represent and support the interests of America’s 21 million veterans, and in fulfillment of our mandate to ensure that the men and women who served are able to receive the health care and benefits they need and deserve, we are calling on Members of Congress to defeat the House vote on unacceptable choice funding legislation (S. 114, with amendments),” the statement read.

AMVETS, Disabled American Veterans , Military Officers Association of America, Military Order of the Purple Heart, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Vietnam Veterans of America, and Wounded Warrior Project all signed on to the statement. The chief complaint was that the legislation “includes funding only for the ‘choice’ program which provides additional community care options, but makes no investment in VA and uses ‘savings’ from other veterans benefits or services to ‘pay’ for the ‘choice’ program.”

The bill would have allocated $2 billion for the Veterans Choice Program, taken funding for veteran housing loan fees, and would reduce the pensions for some veterans living in nursing facilities that also could be paid for under the Medicaid program.

The fate of the bill and funding for the Veterans Choice Program remains unclear. Senate and House veterans committees seem to be far apart on how to fund the program and for efforts to make more substantive changes to the program. Although House Republicans eventually may be able to pass a bill without Democrats, in the Senate, they will need the support of at least a handful of Democrats to move the bill to the President’s desk.

A U.S. House of Representatives appropriation to fund the Veterans Choice Program surprisingly went down to defeat on Monday. The VA Choice Program is set to run out of money in September, and VA officials have been calling for Congress to provide additional funding for the program. Republican leaders, hoping to expedite the bill’s passage and thinking that it was not controversial, submitted the bill in a process that required the votes of two-thirds of the representatives. The 219-186 vote fell well short of the necessary two-thirds, and voting fell largely along party lines.

Many veterans service organizations (VSOs) were critical of the bill and called on the House to make substantial changes to it. Seven VSOs signed a joint statement calling for the bill’s defeat. “As organizations who represent and support the interests of America’s 21 million veterans, and in fulfillment of our mandate to ensure that the men and women who served are able to receive the health care and benefits they need and deserve, we are calling on Members of Congress to defeat the House vote on unacceptable choice funding legislation (S. 114, with amendments),” the statement read.

AMVETS, Disabled American Veterans , Military Officers Association of America, Military Order of the Purple Heart, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Vietnam Veterans of America, and Wounded Warrior Project all signed on to the statement. The chief complaint was that the legislation “includes funding only for the ‘choice’ program which provides additional community care options, but makes no investment in VA and uses ‘savings’ from other veterans benefits or services to ‘pay’ for the ‘choice’ program.”

The bill would have allocated $2 billion for the Veterans Choice Program, taken funding for veteran housing loan fees, and would reduce the pensions for some veterans living in nursing facilities that also could be paid for under the Medicaid program.

The fate of the bill and funding for the Veterans Choice Program remains unclear. Senate and House veterans committees seem to be far apart on how to fund the program and for efforts to make more substantive changes to the program. Although House Republicans eventually may be able to pass a bill without Democrats, in the Senate, they will need the support of at least a handful of Democrats to move the bill to the President’s desk.

A U.S. House of Representatives appropriation to fund the Veterans Choice Program surprisingly went down to defeat on Monday. The VA Choice Program is set to run out of money in September, and VA officials have been calling for Congress to provide additional funding for the program. Republican leaders, hoping to expedite the bill’s passage and thinking that it was not controversial, submitted the bill in a process that required the votes of two-thirds of the representatives. The 219-186 vote fell well short of the necessary two-thirds, and voting fell largely along party lines.

Many veterans service organizations (VSOs) were critical of the bill and called on the House to make substantial changes to it. Seven VSOs signed a joint statement calling for the bill’s defeat. “As organizations who represent and support the interests of America’s 21 million veterans, and in fulfillment of our mandate to ensure that the men and women who served are able to receive the health care and benefits they need and deserve, we are calling on Members of Congress to defeat the House vote on unacceptable choice funding legislation (S. 114, with amendments),” the statement read.

AMVETS, Disabled American Veterans , Military Officers Association of America, Military Order of the Purple Heart, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Vietnam Veterans of America, and Wounded Warrior Project all signed on to the statement. The chief complaint was that the legislation “includes funding only for the ‘choice’ program which provides additional community care options, but makes no investment in VA and uses ‘savings’ from other veterans benefits or services to ‘pay’ for the ‘choice’ program.”

The bill would have allocated $2 billion for the Veterans Choice Program, taken funding for veteran housing loan fees, and would reduce the pensions for some veterans living in nursing facilities that also could be paid for under the Medicaid program.

The fate of the bill and funding for the Veterans Choice Program remains unclear. Senate and House veterans committees seem to be far apart on how to fund the program and for efforts to make more substantive changes to the program. Although House Republicans eventually may be able to pass a bill without Democrats, in the Senate, they will need the support of at least a handful of Democrats to move the bill to the President’s desk.

How to explain physician compounding to legislators

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.