User login

Yeast Infection in Pregnancy? Think Twice About Fluconazole

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although the latter are recommended as firstline therapy, the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive option.3,4

However, the safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy has recently come under scrutiny. Case reports have linked high-dose use with congenital malformation.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiologic studies in which no such association was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1,079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk for congenital malformation or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriage.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants.

The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth, compared to topical azoles.

STUDY SUMMARY

Increased risk for miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole–exposed pregnancy was matched with up to four unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented by filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. Of the total cohort, 3,315 pregnancies were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 147 of these pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR], 1.48).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5,382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR, 1.32). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were four times more likely than lower doses (150 mg) to be associated with stillbirth (HRs, 4.10 and 0.99, respectively).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion, compared to topical azole use (130 of 2,823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2,823 pregnancies; HR, 1.62)—but not an increased risk for stillbirth (20 of 4,301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4,301 pregnancies; HR, 1.18).

WHAT'S NEW

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk for spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the researchers were able to eliminate Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion as a confounding factor. In addition, this study challenges the balance between ease of use and safety.

CAVEATS

A skewed population?

This cohort study using a Danish hospital registry may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Those not seeking care through a hospital were likely missed; if those seeking care through the hospital had a higher risk for abortion, the results could be biased. However, this would not have affected the results of the comparison between the two active treatments.

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically.

In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to four unexposed pregnancies, these limitations likely had little influence on the overall findings.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole, compared with daily topical azole therapy, many clinicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(9):624-626.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al; Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Practitioner. 1985;229:655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although the latter are recommended as firstline therapy, the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive option.3,4

However, the safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy has recently come under scrutiny. Case reports have linked high-dose use with congenital malformation.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiologic studies in which no such association was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1,079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk for congenital malformation or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriage.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants.

The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth, compared to topical azoles.

STUDY SUMMARY

Increased risk for miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole–exposed pregnancy was matched with up to four unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented by filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. Of the total cohort, 3,315 pregnancies were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 147 of these pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR], 1.48).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5,382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR, 1.32). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were four times more likely than lower doses (150 mg) to be associated with stillbirth (HRs, 4.10 and 0.99, respectively).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion, compared to topical azole use (130 of 2,823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2,823 pregnancies; HR, 1.62)—but not an increased risk for stillbirth (20 of 4,301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4,301 pregnancies; HR, 1.18).

WHAT'S NEW

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk for spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the researchers were able to eliminate Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion as a confounding factor. In addition, this study challenges the balance between ease of use and safety.

CAVEATS

A skewed population?

This cohort study using a Danish hospital registry may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Those not seeking care through a hospital were likely missed; if those seeking care through the hospital had a higher risk for abortion, the results could be biased. However, this would not have affected the results of the comparison between the two active treatments.

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically.

In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to four unexposed pregnancies, these limitations likely had little influence on the overall findings.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole, compared with daily topical azole therapy, many clinicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(9):624-626.

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although the latter are recommended as firstline therapy, the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive option.3,4

However, the safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy has recently come under scrutiny. Case reports have linked high-dose use with congenital malformation.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiologic studies in which no such association was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1,079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk for congenital malformation or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriage.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants.

The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth, compared to topical azoles.

STUDY SUMMARY

Increased risk for miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole–exposed pregnancy was matched with up to four unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented by filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. Of the total cohort, 3,315 pregnancies were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 147 of these pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR], 1.48).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5,382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR, 1.32). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were four times more likely than lower doses (150 mg) to be associated with stillbirth (HRs, 4.10 and 0.99, respectively).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion, compared to topical azole use (130 of 2,823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2,823 pregnancies; HR, 1.62)—but not an increased risk for stillbirth (20 of 4,301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4,301 pregnancies; HR, 1.18).

WHAT'S NEW

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk for spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the researchers were able to eliminate Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion as a confounding factor. In addition, this study challenges the balance between ease of use and safety.

CAVEATS

A skewed population?

This cohort study using a Danish hospital registry may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Those not seeking care through a hospital were likely missed; if those seeking care through the hospital had a higher risk for abortion, the results could be biased. However, this would not have affected the results of the comparison between the two active treatments.

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically.

In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to four unexposed pregnancies, these limitations likely had little influence on the overall findings.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole, compared with daily topical azole therapy, many clinicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(9):624-626.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al; Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Practitioner. 1985;229:655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al; Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Practitioner. 1985;229:655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

Monitoring home BP readings just got easier

PRACTICE CHANGER

Use this easy “3 out of 10 rule” to quickly sift through home blood pressure readings and identify patients with uncontrolled hypertension who require pharmacologic management.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a single, good quality, multicenter trial.

Sharman JE, Blizzard L, Kosmala W, et al. Pragmatic method using blood pressure diaries to assess blood pressure control. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:63-69.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

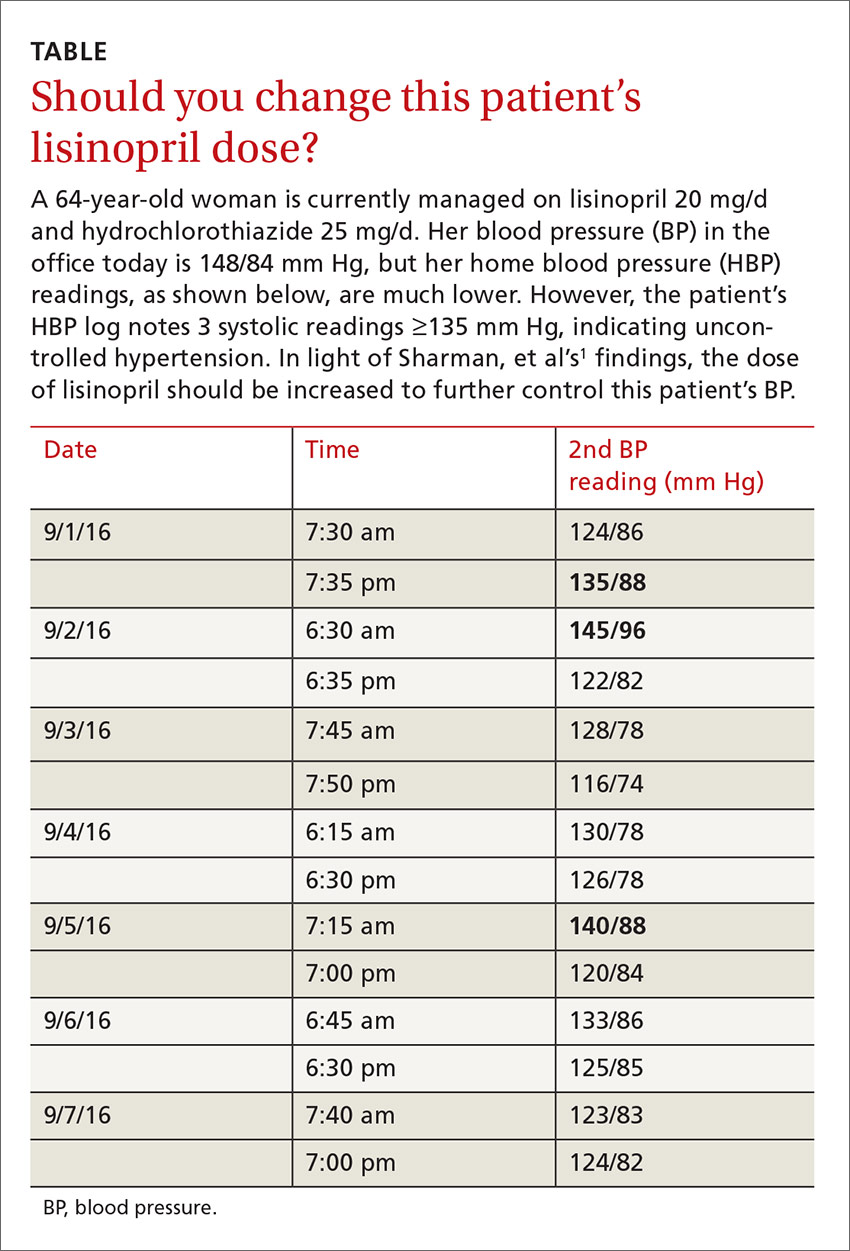

A 64-year-old woman presents to your office for a follow-up visit for her hypertension. She is currently managed on lisinopril 20 mg/d and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d without any problems. The patient’s blood pressure (BP) in the office today is 148/84 mm Hg, but her home blood pressure (HBP) readings are much lower (see TABLE). Should you increase her lisinopril dose today?

Hypertension has been diagnosed on the basis of office readings of BP for almost a century, but the readings can be so inaccurate that they are not useful.2 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends the use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) to accurately diagnose hypertension in all patients, while The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommends ABPM for patients suspected of having white-coat hypertension and any patient with resistant hypertension,3,4 but ABPM is not always acceptable to patients.5

Guidelines recommend HBP monitoring for long-term follow-up of hypertension

The European Society of Hypertension practice guideline on HBP monitoring suggests that HBP values <130/80 mm Hg may be considered normal, while a mean HBP ≥135/85 mm Hg is considered elevated.9 The guideline recommends HBP monitoring for 3 to 7 days prior to a patient’s follow-up appointment with 2 readings taken one to 2 minutes apart in the morning and evening.9 In a busy clinic, averaging all of these home values can be time-consuming.

So how can primary care physicians accurately and efficiently streamline the process? This study sought to answer that question.

STUDY SUMMARY

When 3 of 10 readings are elevated, it’s predictive

This multicenter trial compared HBP monitoring to 24-hour ABPM in 286 patients with uncomplicated essential hypertension to determine the optimal percentage of HBP readings needed to diagnose uncontrolled BP (HBP ≥135/85 mm Hg). Patients were included if they were diagnosed with uncomplicated hypertension, not pregnant, ≥18 years of age, and taking ≤3 antihypertensive medications. Medication compliance was verified by a study nurse at a clinic visit. Patients were excluded if they had a significant abnormal left ventricular mass index (women >59 g/m2; men >64 g/m2), coronary artery or renal disease, secondary hypertension, serum creatinine exceeding 1.6 mg/dL, aortic valve stenosis, upper limb obstructive atherosclerosis, or BP >180/100 mm Hg.

Approximately half of the participants were women (53%), average body mass index was 29.4 kg/m2, and the average number of hypertension medications being taken was 2.4. The patients were instructed to take 2 BP readings (one minute apart) at home 3 times daily, in the morning (between 6 am and 10 am), at noon, and in the evening (between 6 pm and 10 pm), and to record only the second reading for 7 days. Only the morning and evening readings were used for analysis in the study. The 24-hour ABP was measured every 30 minutes during the daytime hours and every 60 minutes overnight. The primary outcome was to determine the optimal number of systolic HBP readings above goal (135 mm Hg), from the last 10 recordings, that would best predict elevated 24-hour ABP. Secondary outcomes were various cardiovascular markers of target end-organ damage.

The researchers found that if at least 3 of the last 10 HBP readings were elevated (≥135 mm Hg systolic), the patient was likely to have hypertension on 24-hour ABPM (≥130 mm Hg). When patients had <3 HBP elevations out of 10 readings, their mean (±standard deviation [SD]) 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 132.7 (±11.1) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 120.4 (±9.8) mm Hg. When patients had ≥3 HBP elevations, their mean 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 143.4 (±11.2) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 147.4 (±10.5) mm Hg.

The positive and negative predictive values of ≥3 HBP elevations were 0.85 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78-0.91) and 0.56 (95% CI, 0.48-0.64), respectively, for a 24-hour systolic ABP of ≥130 mm Hg. Three elevations or more in HBP, out of the last 10 readings, was also an indicator for target organ disease assessed by aortic stiffness and increased left ventricular mass and decreased function.

The sensitivity and specificity of ≥3 elevations for mean 24-hour ABP systolic readings ≥130 mm Hg were 62% and 80%, respectively, and for 24-hour ABP daytime systolic readings ≥135 mm Hg were 65% and 77%, respectively.

WHAT’S NEW

Monitoring home BP can be simplified

The researchers found that HBP monitoring correlates well with ABPM and that their method provides clinicians with a simple way (3 of the past 10 measurements ≥135 mm Hg systolic) to use HBP readings to make clinical decisions regarding BP management.

CAVEATS

Ideal BP goals are hazy, and a lot of patient education is required

Conflicting information and opinions remain regarding the ideal intensive and standard BP goals in different populations.10,11 Systolic BP goals in this study (≥130 mm Hg for overall 24-hour ABP and ≥135 mm Hg for 24-hour ABP daytime readings) are recommended by some experts, but are not commonly recognized goals in the United States. This study found good correlation between HBP and ABPM at these goals, and it seems likely that this correlation could be extrapolated for similar BP goals.

Other limitations are that: 1) The study focused only on systolic BP goals; 2) Patients in the study adhered to precise instructions on BP monitoring. HBP monitoring requires significant patient education on the proper use of the equipment and the monitoring schedule; and 3) While end-organ complication outcomes showed numerical decreases in function, the clinical significance of these reductions for patients is unclear.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost of device and improper cuff sizes could be barriers

The cost of HBP monitors ($40-$60) has decreased significantly over time, but the devices are not always covered by insurance and may be unobtainable for some people. Additionally, patients should be counseled on how to determine the appropriate cuff size to ensure the accuracy of the measurements.

The British Hypertensive Society maintains a list of validated BP devices on their Web site: http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors.12

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Sharman JE, Blizzard L, Kosmala W, et al. Pragmatic method using blood pressure diaries to assess blood pressure control. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:63-69.

2. Sebo P, Pechère-Bertschi A, Herrmann FR, et al. Blood pressure measurements are unreliable to diagnose hypertension in primary care. J Hypertens. 2014;32:509-517.

3. Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Int Med. 2015;163:778-786. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/high-blood-pressure-in-adults-screening. Accessed June 16, 2016.

4. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2560-2572.

5. Mallion JM, de Gaudemaris R, Baguet JP, et al. Acceptability and tolerance of ambulatory blood pressure measurement in the hypertensive patient. Blood Press Monit. 1996;1:197-203.

6. Gaborieau V, Delarche N, Gosse P. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring versus self-measurement of blood pressure at home: correlation with target organ damage. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1919-1927.

7. Ward AM, Takahashi O, Stevens R, et al. Home measurement of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30:449-456.

8. Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, et al. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: executive summary. A joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52:1-9.

9. Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al; ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:779-785.

10. The SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

11. Brunström M, Carlberg B. Effect of antihypertensive treatment at different blood pressure levels in patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2016;352:i717.

12. British Hypertensive Society. BP Monitors. Available at: http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors. Accessed June 27, 2016.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Use this easy “3 out of 10 rule” to quickly sift through home blood pressure readings and identify patients with uncontrolled hypertension who require pharmacologic management.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a single, good quality, multicenter trial.

Sharman JE, Blizzard L, Kosmala W, et al. Pragmatic method using blood pressure diaries to assess blood pressure control. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:63-69.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 64-year-old woman presents to your office for a follow-up visit for her hypertension. She is currently managed on lisinopril 20 mg/d and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d without any problems. The patient’s blood pressure (BP) in the office today is 148/84 mm Hg, but her home blood pressure (HBP) readings are much lower (see TABLE). Should you increase her lisinopril dose today?

Hypertension has been diagnosed on the basis of office readings of BP for almost a century, but the readings can be so inaccurate that they are not useful.2 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends the use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) to accurately diagnose hypertension in all patients, while The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommends ABPM for patients suspected of having white-coat hypertension and any patient with resistant hypertension,3,4 but ABPM is not always acceptable to patients.5

Guidelines recommend HBP monitoring for long-term follow-up of hypertension

The European Society of Hypertension practice guideline on HBP monitoring suggests that HBP values <130/80 mm Hg may be considered normal, while a mean HBP ≥135/85 mm Hg is considered elevated.9 The guideline recommends HBP monitoring for 3 to 7 days prior to a patient’s follow-up appointment with 2 readings taken one to 2 minutes apart in the morning and evening.9 In a busy clinic, averaging all of these home values can be time-consuming.

So how can primary care physicians accurately and efficiently streamline the process? This study sought to answer that question.

STUDY SUMMARY

When 3 of 10 readings are elevated, it’s predictive

This multicenter trial compared HBP monitoring to 24-hour ABPM in 286 patients with uncomplicated essential hypertension to determine the optimal percentage of HBP readings needed to diagnose uncontrolled BP (HBP ≥135/85 mm Hg). Patients were included if they were diagnosed with uncomplicated hypertension, not pregnant, ≥18 years of age, and taking ≤3 antihypertensive medications. Medication compliance was verified by a study nurse at a clinic visit. Patients were excluded if they had a significant abnormal left ventricular mass index (women >59 g/m2; men >64 g/m2), coronary artery or renal disease, secondary hypertension, serum creatinine exceeding 1.6 mg/dL, aortic valve stenosis, upper limb obstructive atherosclerosis, or BP >180/100 mm Hg.

Approximately half of the participants were women (53%), average body mass index was 29.4 kg/m2, and the average number of hypertension medications being taken was 2.4. The patients were instructed to take 2 BP readings (one minute apart) at home 3 times daily, in the morning (between 6 am and 10 am), at noon, and in the evening (between 6 pm and 10 pm), and to record only the second reading for 7 days. Only the morning and evening readings were used for analysis in the study. The 24-hour ABP was measured every 30 minutes during the daytime hours and every 60 minutes overnight. The primary outcome was to determine the optimal number of systolic HBP readings above goal (135 mm Hg), from the last 10 recordings, that would best predict elevated 24-hour ABP. Secondary outcomes were various cardiovascular markers of target end-organ damage.

The researchers found that if at least 3 of the last 10 HBP readings were elevated (≥135 mm Hg systolic), the patient was likely to have hypertension on 24-hour ABPM (≥130 mm Hg). When patients had <3 HBP elevations out of 10 readings, their mean (±standard deviation [SD]) 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 132.7 (±11.1) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 120.4 (±9.8) mm Hg. When patients had ≥3 HBP elevations, their mean 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 143.4 (±11.2) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 147.4 (±10.5) mm Hg.

The positive and negative predictive values of ≥3 HBP elevations were 0.85 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78-0.91) and 0.56 (95% CI, 0.48-0.64), respectively, for a 24-hour systolic ABP of ≥130 mm Hg. Three elevations or more in HBP, out of the last 10 readings, was also an indicator for target organ disease assessed by aortic stiffness and increased left ventricular mass and decreased function.

The sensitivity and specificity of ≥3 elevations for mean 24-hour ABP systolic readings ≥130 mm Hg were 62% and 80%, respectively, and for 24-hour ABP daytime systolic readings ≥135 mm Hg were 65% and 77%, respectively.

WHAT’S NEW

Monitoring home BP can be simplified

The researchers found that HBP monitoring correlates well with ABPM and that their method provides clinicians with a simple way (3 of the past 10 measurements ≥135 mm Hg systolic) to use HBP readings to make clinical decisions regarding BP management.

CAVEATS

Ideal BP goals are hazy, and a lot of patient education is required

Conflicting information and opinions remain regarding the ideal intensive and standard BP goals in different populations.10,11 Systolic BP goals in this study (≥130 mm Hg for overall 24-hour ABP and ≥135 mm Hg for 24-hour ABP daytime readings) are recommended by some experts, but are not commonly recognized goals in the United States. This study found good correlation between HBP and ABPM at these goals, and it seems likely that this correlation could be extrapolated for similar BP goals.

Other limitations are that: 1) The study focused only on systolic BP goals; 2) Patients in the study adhered to precise instructions on BP monitoring. HBP monitoring requires significant patient education on the proper use of the equipment and the monitoring schedule; and 3) While end-organ complication outcomes showed numerical decreases in function, the clinical significance of these reductions for patients is unclear.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost of device and improper cuff sizes could be barriers

The cost of HBP monitors ($40-$60) has decreased significantly over time, but the devices are not always covered by insurance and may be unobtainable for some people. Additionally, patients should be counseled on how to determine the appropriate cuff size to ensure the accuracy of the measurements.

The British Hypertensive Society maintains a list of validated BP devices on their Web site: http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors.12

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Use this easy “3 out of 10 rule” to quickly sift through home blood pressure readings and identify patients with uncontrolled hypertension who require pharmacologic management.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a single, good quality, multicenter trial.

Sharman JE, Blizzard L, Kosmala W, et al. Pragmatic method using blood pressure diaries to assess blood pressure control. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:63-69.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 64-year-old woman presents to your office for a follow-up visit for her hypertension. She is currently managed on lisinopril 20 mg/d and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d without any problems. The patient’s blood pressure (BP) in the office today is 148/84 mm Hg, but her home blood pressure (HBP) readings are much lower (see TABLE). Should you increase her lisinopril dose today?

Hypertension has been diagnosed on the basis of office readings of BP for almost a century, but the readings can be so inaccurate that they are not useful.2 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends the use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) to accurately diagnose hypertension in all patients, while The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommends ABPM for patients suspected of having white-coat hypertension and any patient with resistant hypertension,3,4 but ABPM is not always acceptable to patients.5

Guidelines recommend HBP monitoring for long-term follow-up of hypertension

The European Society of Hypertension practice guideline on HBP monitoring suggests that HBP values <130/80 mm Hg may be considered normal, while a mean HBP ≥135/85 mm Hg is considered elevated.9 The guideline recommends HBP monitoring for 3 to 7 days prior to a patient’s follow-up appointment with 2 readings taken one to 2 minutes apart in the morning and evening.9 In a busy clinic, averaging all of these home values can be time-consuming.

So how can primary care physicians accurately and efficiently streamline the process? This study sought to answer that question.

STUDY SUMMARY

When 3 of 10 readings are elevated, it’s predictive

This multicenter trial compared HBP monitoring to 24-hour ABPM in 286 patients with uncomplicated essential hypertension to determine the optimal percentage of HBP readings needed to diagnose uncontrolled BP (HBP ≥135/85 mm Hg). Patients were included if they were diagnosed with uncomplicated hypertension, not pregnant, ≥18 years of age, and taking ≤3 antihypertensive medications. Medication compliance was verified by a study nurse at a clinic visit. Patients were excluded if they had a significant abnormal left ventricular mass index (women >59 g/m2; men >64 g/m2), coronary artery or renal disease, secondary hypertension, serum creatinine exceeding 1.6 mg/dL, aortic valve stenosis, upper limb obstructive atherosclerosis, or BP >180/100 mm Hg.

Approximately half of the participants were women (53%), average body mass index was 29.4 kg/m2, and the average number of hypertension medications being taken was 2.4. The patients were instructed to take 2 BP readings (one minute apart) at home 3 times daily, in the morning (between 6 am and 10 am), at noon, and in the evening (between 6 pm and 10 pm), and to record only the second reading for 7 days. Only the morning and evening readings were used for analysis in the study. The 24-hour ABP was measured every 30 minutes during the daytime hours and every 60 minutes overnight. The primary outcome was to determine the optimal number of systolic HBP readings above goal (135 mm Hg), from the last 10 recordings, that would best predict elevated 24-hour ABP. Secondary outcomes were various cardiovascular markers of target end-organ damage.

The researchers found that if at least 3 of the last 10 HBP readings were elevated (≥135 mm Hg systolic), the patient was likely to have hypertension on 24-hour ABPM (≥130 mm Hg). When patients had <3 HBP elevations out of 10 readings, their mean (±standard deviation [SD]) 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 132.7 (±11.1) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 120.4 (±9.8) mm Hg. When patients had ≥3 HBP elevations, their mean 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 143.4 (±11.2) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 147.4 (±10.5) mm Hg.

The positive and negative predictive values of ≥3 HBP elevations were 0.85 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78-0.91) and 0.56 (95% CI, 0.48-0.64), respectively, for a 24-hour systolic ABP of ≥130 mm Hg. Three elevations or more in HBP, out of the last 10 readings, was also an indicator for target organ disease assessed by aortic stiffness and increased left ventricular mass and decreased function.

The sensitivity and specificity of ≥3 elevations for mean 24-hour ABP systolic readings ≥130 mm Hg were 62% and 80%, respectively, and for 24-hour ABP daytime systolic readings ≥135 mm Hg were 65% and 77%, respectively.

WHAT’S NEW

Monitoring home BP can be simplified

The researchers found that HBP monitoring correlates well with ABPM and that their method provides clinicians with a simple way (3 of the past 10 measurements ≥135 mm Hg systolic) to use HBP readings to make clinical decisions regarding BP management.

CAVEATS

Ideal BP goals are hazy, and a lot of patient education is required

Conflicting information and opinions remain regarding the ideal intensive and standard BP goals in different populations.10,11 Systolic BP goals in this study (≥130 mm Hg for overall 24-hour ABP and ≥135 mm Hg for 24-hour ABP daytime readings) are recommended by some experts, but are not commonly recognized goals in the United States. This study found good correlation between HBP and ABPM at these goals, and it seems likely that this correlation could be extrapolated for similar BP goals.

Other limitations are that: 1) The study focused only on systolic BP goals; 2) Patients in the study adhered to precise instructions on BP monitoring. HBP monitoring requires significant patient education on the proper use of the equipment and the monitoring schedule; and 3) While end-organ complication outcomes showed numerical decreases in function, the clinical significance of these reductions for patients is unclear.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost of device and improper cuff sizes could be barriers

The cost of HBP monitors ($40-$60) has decreased significantly over time, but the devices are not always covered by insurance and may be unobtainable for some people. Additionally, patients should be counseled on how to determine the appropriate cuff size to ensure the accuracy of the measurements.

The British Hypertensive Society maintains a list of validated BP devices on their Web site: http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors.12

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Sharman JE, Blizzard L, Kosmala W, et al. Pragmatic method using blood pressure diaries to assess blood pressure control. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:63-69.

2. Sebo P, Pechère-Bertschi A, Herrmann FR, et al. Blood pressure measurements are unreliable to diagnose hypertension in primary care. J Hypertens. 2014;32:509-517.

3. Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Int Med. 2015;163:778-786. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/high-blood-pressure-in-adults-screening. Accessed June 16, 2016.

4. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2560-2572.

5. Mallion JM, de Gaudemaris R, Baguet JP, et al. Acceptability and tolerance of ambulatory blood pressure measurement in the hypertensive patient. Blood Press Monit. 1996;1:197-203.

6. Gaborieau V, Delarche N, Gosse P. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring versus self-measurement of blood pressure at home: correlation with target organ damage. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1919-1927.

7. Ward AM, Takahashi O, Stevens R, et al. Home measurement of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30:449-456.

8. Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, et al. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: executive summary. A joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52:1-9.

9. Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al; ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:779-785.

10. The SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

11. Brunström M, Carlberg B. Effect of antihypertensive treatment at different blood pressure levels in patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2016;352:i717.

12. British Hypertensive Society. BP Monitors. Available at: http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors. Accessed June 27, 2016.

1. Sharman JE, Blizzard L, Kosmala W, et al. Pragmatic method using blood pressure diaries to assess blood pressure control. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:63-69.

2. Sebo P, Pechère-Bertschi A, Herrmann FR, et al. Blood pressure measurements are unreliable to diagnose hypertension in primary care. J Hypertens. 2014;32:509-517.

3. Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Int Med. 2015;163:778-786. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/high-blood-pressure-in-adults-screening. Accessed June 16, 2016.

4. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2560-2572.

5. Mallion JM, de Gaudemaris R, Baguet JP, et al. Acceptability and tolerance of ambulatory blood pressure measurement in the hypertensive patient. Blood Press Monit. 1996;1:197-203.

6. Gaborieau V, Delarche N, Gosse P. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring versus self-measurement of blood pressure at home: correlation with target organ damage. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1919-1927.

7. Ward AM, Takahashi O, Stevens R, et al. Home measurement of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30:449-456.

8. Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, et al. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: executive summary. A joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52:1-9.

9. Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al; ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:779-785.

10. The SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

11. Brunström M, Carlberg B. Effect of antihypertensive treatment at different blood pressure levels in patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2016;352:i717.

12. British Hypertensive Society. BP Monitors. Available at: http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors. Accessed June 27, 2016.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Yeast infection in pregnancy? Think twice about fluconazole

PRACTICE CHANGER

Avoid prescribing oral fluconazole in early pregnancy because it is associated with a higher rate of spontaneous abortion than is topical azole therapy.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on large cohort study performed in Denmark.

Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

Illustrative Case

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although topical azoles are recommended as first-line therapy,3 the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive treatment option.4 The safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy, however, has recently come under scrutiny.

Case reports have linked high-dose fluconazole use during pregnancy with congenital malformations.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiological studies evaluating fluconazole’s safety, but, in these studies, no association with congenital malformations was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk of congenital malformations or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriages.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants. The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole compared to that of topical azoles in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth.

Study Summary

Fluconazole significantly increases risk of miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole-exposed pregnancy was matched with up to 4 unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented based on filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. From the total cohort of more than 1.4 million pregnancies, 3315 were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortions occurred in 147 of the 3315 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR]=1.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.23-1.77).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR=1.32; 95% CI, 0.82-2.14). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were 4 times more likely to be associated with stillbirth (HR=4.10; 95% CI, 1.89-8.90) than lower doses (150 mg) (HR= 0.99; 95% CI, 0.56-1.74).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion when compared to topical azole use: 130 of 2823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2823 pregnancies, respectively (HR=1.62; 95% CI, 1.26-2.07), but not an increased risk of stillbirths: 20 of 4301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4301 pregnancies, respectively (HR=1.18; 95% CI, 0.64-2.16).

What’s New

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk of spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the confounder of Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion was removed. In addition, when considering the ease of dosing of fluconazole as compared with topical imidazoles, this study challenges the balance of ease of use with safety.

Caveats

A skewed population and limited generalizability?

This large cohort study using the National Patient Register in Denmark may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Since a hospital registry was used, those not seeking care through the hospital were likely missed. If patients

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically. In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to 4 unexposed pregnancies, these limitations are likely to have had little influence on the overall findings of the study.

Challenges to Implementation

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole vs daily topical azole therapy, many physicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidosis. Practitioner. 1985;229: 655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Avoid prescribing oral fluconazole in early pregnancy because it is associated with a higher rate of spontaneous abortion than is topical azole therapy.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on large cohort study performed in Denmark.

Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

Illustrative Case

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although topical azoles are recommended as first-line therapy,3 the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive treatment option.4 The safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy, however, has recently come under scrutiny.

Case reports have linked high-dose fluconazole use during pregnancy with congenital malformations.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiological studies evaluating fluconazole’s safety, but, in these studies, no association with congenital malformations was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk of congenital malformations or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriages.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants. The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole compared to that of topical azoles in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth.

Study Summary

Fluconazole significantly increases risk of miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole-exposed pregnancy was matched with up to 4 unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented based on filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. From the total cohort of more than 1.4 million pregnancies, 3315 were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortions occurred in 147 of the 3315 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR]=1.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.23-1.77).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR=1.32; 95% CI, 0.82-2.14). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were 4 times more likely to be associated with stillbirth (HR=4.10; 95% CI, 1.89-8.90) than lower doses (150 mg) (HR= 0.99; 95% CI, 0.56-1.74).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion when compared to topical azole use: 130 of 2823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2823 pregnancies, respectively (HR=1.62; 95% CI, 1.26-2.07), but not an increased risk of stillbirths: 20 of 4301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4301 pregnancies, respectively (HR=1.18; 95% CI, 0.64-2.16).

What’s New

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk of spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the confounder of Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion was removed. In addition, when considering the ease of dosing of fluconazole as compared with topical imidazoles, this study challenges the balance of ease of use with safety.

Caveats

A skewed population and limited generalizability?

This large cohort study using the National Patient Register in Denmark may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Since a hospital registry was used, those not seeking care through the hospital were likely missed. If patients

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically. In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to 4 unexposed pregnancies, these limitations are likely to have had little influence on the overall findings of the study.

Challenges to Implementation

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole vs daily topical azole therapy, many physicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Avoid prescribing oral fluconazole in early pregnancy because it is associated with a higher rate of spontaneous abortion than is topical azole therapy.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on large cohort study performed in Denmark.

Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

Illustrative Case

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although topical azoles are recommended as first-line therapy,3 the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive treatment option.4 The safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy, however, has recently come under scrutiny.

Case reports have linked high-dose fluconazole use during pregnancy with congenital malformations.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiological studies evaluating fluconazole’s safety, but, in these studies, no association with congenital malformations was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk of congenital malformations or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriages.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants. The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole compared to that of topical azoles in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth.

Study Summary

Fluconazole significantly increases risk of miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole-exposed pregnancy was matched with up to 4 unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented based on filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. From the total cohort of more than 1.4 million pregnancies, 3315 were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortions occurred in 147 of the 3315 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR]=1.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.23-1.77).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR=1.32; 95% CI, 0.82-2.14). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were 4 times more likely to be associated with stillbirth (HR=4.10; 95% CI, 1.89-8.90) than lower doses (150 mg) (HR= 0.99; 95% CI, 0.56-1.74).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion when compared to topical azole use: 130 of 2823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2823 pregnancies, respectively (HR=1.62; 95% CI, 1.26-2.07), but not an increased risk of stillbirths: 20 of 4301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4301 pregnancies, respectively (HR=1.18; 95% CI, 0.64-2.16).

What’s New

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk of spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the confounder of Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion was removed. In addition, when considering the ease of dosing of fluconazole as compared with topical imidazoles, this study challenges the balance of ease of use with safety.

Caveats

A skewed population and limited generalizability?

This large cohort study using the National Patient Register in Denmark may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Since a hospital registry was used, those not seeking care through the hospital were likely missed. If patients

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically. In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to 4 unexposed pregnancies, these limitations are likely to have had little influence on the overall findings of the study.

Challenges to Implementation

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole vs daily topical azole therapy, many physicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidosis. Practitioner. 1985;229: 655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidosis. Practitioner. 1985;229: 655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

On-demand Pill Protocol Protects Against HIV

In most high-income countries, including the US, HIV-1 infection continues to occur in high-risk groups, especially among men who have sex with men (MSM).2 In the absence of a vaccine, condom use has served as the primary method of preventing infection.

In 2014, the CDC began recommending daily use of tenofovir, disoproxil, fumarate, and emtricitabine (TDF-FTC) in high-risk individuals as a form of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP).3-5 This recommendation is based primarily on the Preexposure Prophylaxis Initiative (iPrEx) trial, which showed a relative reduction of 44% (number needed to treat [NNT], 46 over 1.2 years) in the incidence of new HIV-1 infection among men and transgender women who have sex with men when TDF-FTC was used on a daily basis.6 However, the effectiveness of this strategy in the real world has not been as high as hoped, presumably due to the difficulty in getting patients to take the medication daily.7,8

While it would likely improve adherence rates, the use of prophylaxis in an on-demand manner is not currently recommended.5 This is because, until now, no studies had demonstrated the effectiveness of PrEP used episodically and taken only around the time of potential exposure.

STUDY SUMMARY

Fewer pills improves adherence, reduces HIV infection rates

The Intervention Preventive de l’Exposition aux Risques avec et pour les Gays study—a double-blind, multicenter study conducted in France and Canada—assessed the efficacy and safety of prophylaxis with TDF-FTC used in an on-demand fashion by MSM.1 The study hypothesis proposed that adherence would be higher if chemoprophylaxis was taken only around the time of intercourse, rather than daily, and that this would further reduce the risk for HIV infection.

The study randomized 414 participants who were considered to be at high risk for acquiring HIV-1 infection—defined as having a history of unprotected anal sex with at least two partners in the past six months. Other inclusion criteria included an age of at least 18 and male or transgender female sex. Exclusion criteria included current HIV infection, hepatitis B or C infection, creatinine clearance < 60 mL/min, alanine aminotransferase level more than 2.5 times the upper limit of normal, and significant glycosuria or proteinuria.

The pill and visit schedule. Those who withdrew consent, were lost to follow-up, or acquired HIV-1 infection were excluded, and the remaining study participants were randomized to take TDF-FTC (n = 199) or placebo (n = 201) before and after sexual activity. The dose of TDF-FTC was fixed at 300 mg of TDF and 200 mg of FTC per pill. Participants were instructed to take a loading dose of two pills of TDF-FTC or placebo with food two to 24 hours prior to intercourse, a third pill 24 hours later, and a fourth pill 24 hours after the third.

If there were multiple consecutive days of sexual intercourse, participants were to take one pill on each day of intercourse, followed by the two postexposure pills. If sexual activity resumed within a week of the prior episode, participants were instructed to take only one pill when resuming the PrEP; otherwise, they were to begin again with two pills two to 24 hours prior to intercourse and repeat the protocol.

Study coordinators followed participants four and eight weeks after enrollment, then every eight weeks subsequently. The investigators tested the participants for HIV-1 and HIV-2 at each visit and assessed adherence by pill count, drug levels in plasma, and with an at-home, computer-assisted interview completed by participants prior to each visit.

Participants received counseling from a peer community member and were offered preventive services and testing for other sexually transmitted infections. They were given free condoms and gel at each visit, as well as enough pills (TDF-FTC or placebo) to cover daily use until their next visit.