User login

Suspect an eating disorder? Suggest CBT

Refer patients with eating disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) for cognitive behavioral therapy. CBT, which has proven to be the most useful behavioral treatment for bulimia,1 has now been shown to be effective for patients in the NOS category.2

Strength of recommendation

B: 1 high-quality, randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, et al. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: a two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:311-319.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 23-year-old patient with a body mass index (BMI) of 18 tells you she’s fat and she’s afraid of gaining weight. Further questioning reveals that your patient binges on cookies and potato chips about once a week, then compensates for overeating by taking laxatives or exercising excessively—a practice she’s been following since she started college several years ago. The eating disorder she describes does not meet the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) for bulimia or anorexia nervosa, although it has elements of both. Rather, it fits the diagnostic criteria for eating disorder NOS. You’re aware that CBT is the first-line behavioral treatment for bulimia, and wonder whether it would be helpful for your patient.

Eating disorders often go undetected and untreated in primary care practices,3 as many patients don’t volunteer information about their weight or behaviors related to food, and physicians often fail to ask. Overall, as few as 10% of those with eating disorders receive any form of treatment.1

Would you recognize this loosely defined disorder?

In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of eating disorders is 0.6% for anorexia nervosa (0.3% for men and 0.9% for women), 1.0% for bulimia (0.5% for men and 1.5% for women), and 2.8% for binge-eating disorder (2.0% for men, 3.5% for women).4 Eating disorder NOS, which encompasses subthreshold cases of anorexia or bulimia, patients with elements of both anorexia and bulimia, and patients with binge-eating disorder, accounts for 50% to 80% of eating disorder diagnoses in outpatient settings. Yet there have been few studies of the treatment of these patients.2,5,6

A review of DSM-IV criteria

The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa include a refusal to maintain a weight of at least 85% of normal body weight (or having a BMI ≤17.5), intense fear of gaining weight, disturbance in the way one’s body shape is experienced, and amenorrhea in females who are post-menarche.

Criteria for bulimia include recurrent episodes of binge eating (consuming a large amount of food with a sense of lack of control over eating) and recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain (self-induced vomiting, excessive exercise, fasting, laxatives, diuretics, or enemas) at least twice weekly for 3 months; and self-evaluation that is unduly influenced by body shape and weight.7 Most patients with eating disorder NOS have clinical features of both anorexia and bulimia.6

APA guidelines are silent on NOS

CBT has consistently proven to be the most useful behavioral treatment for patients with bulimia.1 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine—the only medication with Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of an eating disorder8 —are about as effective as CBT, and the combination of CBT and an SSRI is superior to either treatment alone.9 CBT has also been found to be somewhat effective in treating binge-eating disorder.10

Anorexia nervosa, the most deadly eating disorder (the mortality rate is 6.6%11 ) and the most difficult to treat, is the exception. Several studies have assessed CBT for treating anorexia, but it has not been found to be very effective.10,12,13

The 2006 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with eating disorders feature recommendations for anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder, but do not address eating disorder NOS.10 The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom issued guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders in 2004. In response to the lack of evidence for treating eating disorder NOS, NICE recommended basing treatment on the form of eating disorder that most closely resembles the patient’s presentation.14 Fairburn et al addressed the lack of evidence for treatment of eating disorder NOS with the study summarized here.

STUDY SUMMARY: Both broad and focused CBT delivered results

Conducted at 2 eating disorder centers in the United Kingdom, this RCT included 154 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who met DSM-IV criteria for either bulimia or eating disorder NOS. Exclusion criteria included prior treatment with CBT or other evidence-based treatment for the same eating disorder, and a BMI ≤17.5.

Most of the patients were female (95.5%) and white (90.3%), with a median age of 26 years and a median duration of eating disorder of 8.6 years. Sixty-two percent of the patients had a diagnosis of eating disorder NOS, and 38% were diagnosed with bulimia. Half of the patients had another current psychiatric diagnosis—a major depressive disorder, an anxiety disorder, or substance abuse.

The patients were randomized into 4 groups: Two received immediate treatment, and the other 2, referred to as waiting list controls, waited 8 weeks before beginning treatment. Treatment consisted of 1 of 2 forms of CBT-E, an enhanced form of CBT used to treat adult outpatients with eating disorders. Patients either received CBT-Ef, a focused form of CBT that exclusively targets eating disorder psychopathology, or CBT-Eb, a broader form of therapy that also addresses other problems that are common in patients with eating disorders, such as perfectionism and low self-esteem.

Both types of CBT-E featured a 90-minute preparatory session, 20 50-minute sessions, and 1 review session 20 weeks after completion of treatment. In the first 4 sessions, CBT-Ef and CBT-Eb were identical—addressing the eating disorder exclusively. CBT-Ef continued to focus on the eating disorder for the rest of the sessions, while subsequent CBT-Eb sessions also dealt with mood intolerance, interpersonal difficulties, and related issues. Five therapists—4 psychologists and 1 nurse-therapist—conducted the treatments.

Patients were weaned from ongoing psychiatric therapy during the study, but those who were on antidepressant therapy (n=76) were able to continue it. Patients were assessed before treatment, at the end of the waiting period for those in the control groups, after 8 weeks of treatment, at the end of treatment, and 20, 40, and 60 weeks after completion of treatment. (Twenty-two percent of the enrollees did not complete treatment.)

Primary outcomes were based on the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE), administered by assessors who were not involved in the treatment and were blinded to the patients’ group assignment. Change in severity of eating disorder features was measured by the global EDE score (0-6) and attaining a global EDE score <1.74 (<1 standard deviation above the community mean).

No treatment vs CBT. The waiting period left little doubt of the short-term efficacy of CBT: After 8 weeks, there was significant improvement in eating disorder behaviors and overall severity in both the CBT-Ef and CBT-Eb groups (EDE scores fell from 4.15 at baseline to 3.26 and from 4.04 to 2.89, respectively). In the same time period, scores for the waiting list control groups remained flat (from 4.08 at baseline to 3.99).

At the end of treatment and at the 60-week follow-up, patients in both forms of CBT-E showed significant improvement across all measures, with no significant difference between treatments. By the end of treatment, 66.4% of those who completed all of the CBT sessions had global EDE scores <1.74 (considered clinically significant).

Subgroup analysis offers opportunity for fine-tuning

When analyzed separately, the patients with bulimia and those with eating disorder NOS did equally well at the end of treatment: 52.7% of those with bulimia and 53.3% of those with eating disorder NOS had global EDE scores <1.74. At the 60-week follow-up, the patients with bulimia maintained their improvement slightly more: 61.4% had global EDE scores <1.74, compared with 45.7% of the patients with eating disorder NOS.

The researchers also compared the outcomes of patients with the most complex additional psychopathology with those of patients with less complex problems. Greater complexity was defined as moderate ratings in at least 2 of the following domains: mood intolerance, clinical perfectionism, low self-esteem, and interpersonal difficulties.

Broad focus more effective for high complexity. Overall, those in the more complex subgroup did not respond as well; 48% had global EDE scores <1.74, vs 60% of those in the less complex group. However, those in the more complex subgroup did better with the broad form of CBT (at 60-week follow up, 60% had scores <1.74 with CBT-Eb, compared with 40% in the CBT-Ef treatment arm), while the less complex subgroup did better with the more tightly focused CBT-Ef. 2

WHAT’S NEW: Evidence supports CBT for NOS diagnosis

The most recent (2004) Cochrane review of “psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa and binging” included 40 RCTs of patients with bulimia, binge-eating disorder, and eating disorder NOS with recurrent binge-eating episodes (included in 7 studies). While the review confirmed that CBT is effective for bulimia and “similar syndromes,” it identified a need for larger and higher quality trials of CBT, particularly in patients with eating disorder NOS.1 The study reviewed in this PURL—the first large, high-quality trial to include a number of patients with eating disorder NOS—provides strong evidence that CBT is effective for this group of patients.2

CAVEATS: Limited wait time leaves unanswered questions

One limitation of this study is the lack of a control group beyond the 8-week waiting period. Prior studies of CBT for bulimia that delayed therapy for those in the control groups for a longer duration have consistently shown that patients receiving CBT did significantly better than those in the control group.9 While a “no treatment” group would have made the results more robust in this case, it would not have been ethical to withhold treatment for the entire length of the study.

It is noteworthy, too, that this study only included patients with a BMI >17.5. Patients with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, who by definition have a lower BMI, will need other treatments, including hospitalization in some cases.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Identifying patients and therapists

The primary challenge is to determine which of your patients have eating disorders. When discussing diet, adding a simple question such as, “Are you happy with your current weight?” can help you identify those who meet the criteria for an eating disorder or are at high risk.3

Identifying local mental health providers who are trained to provide CBT for patients with eating disorders is another concern. Insurance coverage for this intensive treatment may also be a limiting factor in some cases.

Many studies support the use of fluoxetine for patients with bulimia, and combined treatment with SSRIs and CBT has been shown to be superior to either treatment alone.8,10,14 Consider starting the patient on an antidepressant while she (or he) awaits the start of CBT.

Acknowledgements

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURLs) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

1. Hay PJ, Bacaltchuk J, Stefano S. Psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa and binging. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000562.

2. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, et al. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: a two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:311-319.

3. Pritts SD, Susman J. Diagnosis of eating disorders in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:297-304.

4. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348-358.

5. Button EJ, Benson E, Nollett C, et al. Don’t forget EDNOS (eating disorder not otherwise specified): patterns of service use in an eating disorders service. Psychiatr Bull. 2005;29:134-136.

6. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Bohn K, et al. The severity and status of eating disorder NOS: implications for DSM-V. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1705-1715.

7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:583-595,787.

8. Berkman ND, Bulik CM, Brownley KA, et al. Management of eating disorders. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No.135. AHRQ Publication No. 06-E010. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; April 2006.

9. Shapiro JR, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, et al. Bulimia nervosa treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:321-336.

10. American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline. Treatment of patients with eating disorders. 3rd ed Available at: http://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/pracGuideTopic_12.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2009.

11. Eckert ED, Halmi KA, Marchi P, et al. Ten-year follow-up of anorexia nervosa: clinical course and outcome. Psychol Med. 1995;25:143-156.

12. Hay PJ, Bacaltchuk J, Byrnes RT, et al. Individual psychotherapy in the outpatient treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD003909.

13. Morris J, Twaddle S. Anorexia Nervosa. BMJ. 2007;334:894-898.

14. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Eating disorders: core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders. Clinical guideline 9. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG9/niceguidance/pdf/English. Accessed June 28, 2007.

Refer patients with eating disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) for cognitive behavioral therapy. CBT, which has proven to be the most useful behavioral treatment for bulimia,1 has now been shown to be effective for patients in the NOS category.2

Strength of recommendation

B: 1 high-quality, randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, et al. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: a two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:311-319.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 23-year-old patient with a body mass index (BMI) of 18 tells you she’s fat and she’s afraid of gaining weight. Further questioning reveals that your patient binges on cookies and potato chips about once a week, then compensates for overeating by taking laxatives or exercising excessively—a practice she’s been following since she started college several years ago. The eating disorder she describes does not meet the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) for bulimia or anorexia nervosa, although it has elements of both. Rather, it fits the diagnostic criteria for eating disorder NOS. You’re aware that CBT is the first-line behavioral treatment for bulimia, and wonder whether it would be helpful for your patient.

Eating disorders often go undetected and untreated in primary care practices,3 as many patients don’t volunteer information about their weight or behaviors related to food, and physicians often fail to ask. Overall, as few as 10% of those with eating disorders receive any form of treatment.1

Would you recognize this loosely defined disorder?

In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of eating disorders is 0.6% for anorexia nervosa (0.3% for men and 0.9% for women), 1.0% for bulimia (0.5% for men and 1.5% for women), and 2.8% for binge-eating disorder (2.0% for men, 3.5% for women).4 Eating disorder NOS, which encompasses subthreshold cases of anorexia or bulimia, patients with elements of both anorexia and bulimia, and patients with binge-eating disorder, accounts for 50% to 80% of eating disorder diagnoses in outpatient settings. Yet there have been few studies of the treatment of these patients.2,5,6

A review of DSM-IV criteria

The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa include a refusal to maintain a weight of at least 85% of normal body weight (or having a BMI ≤17.5), intense fear of gaining weight, disturbance in the way one’s body shape is experienced, and amenorrhea in females who are post-menarche.

Criteria for bulimia include recurrent episodes of binge eating (consuming a large amount of food with a sense of lack of control over eating) and recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain (self-induced vomiting, excessive exercise, fasting, laxatives, diuretics, or enemas) at least twice weekly for 3 months; and self-evaluation that is unduly influenced by body shape and weight.7 Most patients with eating disorder NOS have clinical features of both anorexia and bulimia.6

APA guidelines are silent on NOS

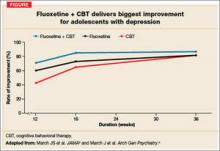

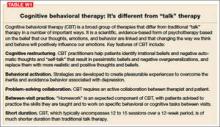

CBT has consistently proven to be the most useful behavioral treatment for patients with bulimia.1 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine—the only medication with Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of an eating disorder8 —are about as effective as CBT, and the combination of CBT and an SSRI is superior to either treatment alone.9 CBT has also been found to be somewhat effective in treating binge-eating disorder.10

Anorexia nervosa, the most deadly eating disorder (the mortality rate is 6.6%11 ) and the most difficult to treat, is the exception. Several studies have assessed CBT for treating anorexia, but it has not been found to be very effective.10,12,13

The 2006 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with eating disorders feature recommendations for anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder, but do not address eating disorder NOS.10 The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom issued guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders in 2004. In response to the lack of evidence for treating eating disorder NOS, NICE recommended basing treatment on the form of eating disorder that most closely resembles the patient’s presentation.14 Fairburn et al addressed the lack of evidence for treatment of eating disorder NOS with the study summarized here.

STUDY SUMMARY: Both broad and focused CBT delivered results

Conducted at 2 eating disorder centers in the United Kingdom, this RCT included 154 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who met DSM-IV criteria for either bulimia or eating disorder NOS. Exclusion criteria included prior treatment with CBT or other evidence-based treatment for the same eating disorder, and a BMI ≤17.5.

Most of the patients were female (95.5%) and white (90.3%), with a median age of 26 years and a median duration of eating disorder of 8.6 years. Sixty-two percent of the patients had a diagnosis of eating disorder NOS, and 38% were diagnosed with bulimia. Half of the patients had another current psychiatric diagnosis—a major depressive disorder, an anxiety disorder, or substance abuse.

The patients were randomized into 4 groups: Two received immediate treatment, and the other 2, referred to as waiting list controls, waited 8 weeks before beginning treatment. Treatment consisted of 1 of 2 forms of CBT-E, an enhanced form of CBT used to treat adult outpatients with eating disorders. Patients either received CBT-Ef, a focused form of CBT that exclusively targets eating disorder psychopathology, or CBT-Eb, a broader form of therapy that also addresses other problems that are common in patients with eating disorders, such as perfectionism and low self-esteem.

Both types of CBT-E featured a 90-minute preparatory session, 20 50-minute sessions, and 1 review session 20 weeks after completion of treatment. In the first 4 sessions, CBT-Ef and CBT-Eb were identical—addressing the eating disorder exclusively. CBT-Ef continued to focus on the eating disorder for the rest of the sessions, while subsequent CBT-Eb sessions also dealt with mood intolerance, interpersonal difficulties, and related issues. Five therapists—4 psychologists and 1 nurse-therapist—conducted the treatments.

Patients were weaned from ongoing psychiatric therapy during the study, but those who were on antidepressant therapy (n=76) were able to continue it. Patients were assessed before treatment, at the end of the waiting period for those in the control groups, after 8 weeks of treatment, at the end of treatment, and 20, 40, and 60 weeks after completion of treatment. (Twenty-two percent of the enrollees did not complete treatment.)

Primary outcomes were based on the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE), administered by assessors who were not involved in the treatment and were blinded to the patients’ group assignment. Change in severity of eating disorder features was measured by the global EDE score (0-6) and attaining a global EDE score <1.74 (<1 standard deviation above the community mean).

No treatment vs CBT. The waiting period left little doubt of the short-term efficacy of CBT: After 8 weeks, there was significant improvement in eating disorder behaviors and overall severity in both the CBT-Ef and CBT-Eb groups (EDE scores fell from 4.15 at baseline to 3.26 and from 4.04 to 2.89, respectively). In the same time period, scores for the waiting list control groups remained flat (from 4.08 at baseline to 3.99).

At the end of treatment and at the 60-week follow-up, patients in both forms of CBT-E showed significant improvement across all measures, with no significant difference between treatments. By the end of treatment, 66.4% of those who completed all of the CBT sessions had global EDE scores <1.74 (considered clinically significant).

Subgroup analysis offers opportunity for fine-tuning

When analyzed separately, the patients with bulimia and those with eating disorder NOS did equally well at the end of treatment: 52.7% of those with bulimia and 53.3% of those with eating disorder NOS had global EDE scores <1.74. At the 60-week follow-up, the patients with bulimia maintained their improvement slightly more: 61.4% had global EDE scores <1.74, compared with 45.7% of the patients with eating disorder NOS.

The researchers also compared the outcomes of patients with the most complex additional psychopathology with those of patients with less complex problems. Greater complexity was defined as moderate ratings in at least 2 of the following domains: mood intolerance, clinical perfectionism, low self-esteem, and interpersonal difficulties.

Broad focus more effective for high complexity. Overall, those in the more complex subgroup did not respond as well; 48% had global EDE scores <1.74, vs 60% of those in the less complex group. However, those in the more complex subgroup did better with the broad form of CBT (at 60-week follow up, 60% had scores <1.74 with CBT-Eb, compared with 40% in the CBT-Ef treatment arm), while the less complex subgroup did better with the more tightly focused CBT-Ef. 2

WHAT’S NEW: Evidence supports CBT for NOS diagnosis

The most recent (2004) Cochrane review of “psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa and binging” included 40 RCTs of patients with bulimia, binge-eating disorder, and eating disorder NOS with recurrent binge-eating episodes (included in 7 studies). While the review confirmed that CBT is effective for bulimia and “similar syndromes,” it identified a need for larger and higher quality trials of CBT, particularly in patients with eating disorder NOS.1 The study reviewed in this PURL—the first large, high-quality trial to include a number of patients with eating disorder NOS—provides strong evidence that CBT is effective for this group of patients.2

CAVEATS: Limited wait time leaves unanswered questions

One limitation of this study is the lack of a control group beyond the 8-week waiting period. Prior studies of CBT for bulimia that delayed therapy for those in the control groups for a longer duration have consistently shown that patients receiving CBT did significantly better than those in the control group.9 While a “no treatment” group would have made the results more robust in this case, it would not have been ethical to withhold treatment for the entire length of the study.

It is noteworthy, too, that this study only included patients with a BMI >17.5. Patients with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, who by definition have a lower BMI, will need other treatments, including hospitalization in some cases.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Identifying patients and therapists

The primary challenge is to determine which of your patients have eating disorders. When discussing diet, adding a simple question such as, “Are you happy with your current weight?” can help you identify those who meet the criteria for an eating disorder or are at high risk.3

Identifying local mental health providers who are trained to provide CBT for patients with eating disorders is another concern. Insurance coverage for this intensive treatment may also be a limiting factor in some cases.

Many studies support the use of fluoxetine for patients with bulimia, and combined treatment with SSRIs and CBT has been shown to be superior to either treatment alone.8,10,14 Consider starting the patient on an antidepressant while she (or he) awaits the start of CBT.

Acknowledgements

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURLs) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

Refer patients with eating disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) for cognitive behavioral therapy. CBT, which has proven to be the most useful behavioral treatment for bulimia,1 has now been shown to be effective for patients in the NOS category.2

Strength of recommendation

B: 1 high-quality, randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, et al. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: a two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:311-319.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 23-year-old patient with a body mass index (BMI) of 18 tells you she’s fat and she’s afraid of gaining weight. Further questioning reveals that your patient binges on cookies and potato chips about once a week, then compensates for overeating by taking laxatives or exercising excessively—a practice she’s been following since she started college several years ago. The eating disorder she describes does not meet the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) for bulimia or anorexia nervosa, although it has elements of both. Rather, it fits the diagnostic criteria for eating disorder NOS. You’re aware that CBT is the first-line behavioral treatment for bulimia, and wonder whether it would be helpful for your patient.

Eating disorders often go undetected and untreated in primary care practices,3 as many patients don’t volunteer information about their weight or behaviors related to food, and physicians often fail to ask. Overall, as few as 10% of those with eating disorders receive any form of treatment.1

Would you recognize this loosely defined disorder?

In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of eating disorders is 0.6% for anorexia nervosa (0.3% for men and 0.9% for women), 1.0% for bulimia (0.5% for men and 1.5% for women), and 2.8% for binge-eating disorder (2.0% for men, 3.5% for women).4 Eating disorder NOS, which encompasses subthreshold cases of anorexia or bulimia, patients with elements of both anorexia and bulimia, and patients with binge-eating disorder, accounts for 50% to 80% of eating disorder diagnoses in outpatient settings. Yet there have been few studies of the treatment of these patients.2,5,6

A review of DSM-IV criteria

The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa include a refusal to maintain a weight of at least 85% of normal body weight (or having a BMI ≤17.5), intense fear of gaining weight, disturbance in the way one’s body shape is experienced, and amenorrhea in females who are post-menarche.

Criteria for bulimia include recurrent episodes of binge eating (consuming a large amount of food with a sense of lack of control over eating) and recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain (self-induced vomiting, excessive exercise, fasting, laxatives, diuretics, or enemas) at least twice weekly for 3 months; and self-evaluation that is unduly influenced by body shape and weight.7 Most patients with eating disorder NOS have clinical features of both anorexia and bulimia.6

APA guidelines are silent on NOS

CBT has consistently proven to be the most useful behavioral treatment for patients with bulimia.1 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine—the only medication with Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of an eating disorder8 —are about as effective as CBT, and the combination of CBT and an SSRI is superior to either treatment alone.9 CBT has also been found to be somewhat effective in treating binge-eating disorder.10

Anorexia nervosa, the most deadly eating disorder (the mortality rate is 6.6%11 ) and the most difficult to treat, is the exception. Several studies have assessed CBT for treating anorexia, but it has not been found to be very effective.10,12,13

The 2006 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with eating disorders feature recommendations for anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder, but do not address eating disorder NOS.10 The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom issued guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders in 2004. In response to the lack of evidence for treating eating disorder NOS, NICE recommended basing treatment on the form of eating disorder that most closely resembles the patient’s presentation.14 Fairburn et al addressed the lack of evidence for treatment of eating disorder NOS with the study summarized here.

STUDY SUMMARY: Both broad and focused CBT delivered results

Conducted at 2 eating disorder centers in the United Kingdom, this RCT included 154 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who met DSM-IV criteria for either bulimia or eating disorder NOS. Exclusion criteria included prior treatment with CBT or other evidence-based treatment for the same eating disorder, and a BMI ≤17.5.

Most of the patients were female (95.5%) and white (90.3%), with a median age of 26 years and a median duration of eating disorder of 8.6 years. Sixty-two percent of the patients had a diagnosis of eating disorder NOS, and 38% were diagnosed with bulimia. Half of the patients had another current psychiatric diagnosis—a major depressive disorder, an anxiety disorder, or substance abuse.

The patients were randomized into 4 groups: Two received immediate treatment, and the other 2, referred to as waiting list controls, waited 8 weeks before beginning treatment. Treatment consisted of 1 of 2 forms of CBT-E, an enhanced form of CBT used to treat adult outpatients with eating disorders. Patients either received CBT-Ef, a focused form of CBT that exclusively targets eating disorder psychopathology, or CBT-Eb, a broader form of therapy that also addresses other problems that are common in patients with eating disorders, such as perfectionism and low self-esteem.

Both types of CBT-E featured a 90-minute preparatory session, 20 50-minute sessions, and 1 review session 20 weeks after completion of treatment. In the first 4 sessions, CBT-Ef and CBT-Eb were identical—addressing the eating disorder exclusively. CBT-Ef continued to focus on the eating disorder for the rest of the sessions, while subsequent CBT-Eb sessions also dealt with mood intolerance, interpersonal difficulties, and related issues. Five therapists—4 psychologists and 1 nurse-therapist—conducted the treatments.

Patients were weaned from ongoing psychiatric therapy during the study, but those who were on antidepressant therapy (n=76) were able to continue it. Patients were assessed before treatment, at the end of the waiting period for those in the control groups, after 8 weeks of treatment, at the end of treatment, and 20, 40, and 60 weeks after completion of treatment. (Twenty-two percent of the enrollees did not complete treatment.)

Primary outcomes were based on the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE), administered by assessors who were not involved in the treatment and were blinded to the patients’ group assignment. Change in severity of eating disorder features was measured by the global EDE score (0-6) and attaining a global EDE score <1.74 (<1 standard deviation above the community mean).

No treatment vs CBT. The waiting period left little doubt of the short-term efficacy of CBT: After 8 weeks, there was significant improvement in eating disorder behaviors and overall severity in both the CBT-Ef and CBT-Eb groups (EDE scores fell from 4.15 at baseline to 3.26 and from 4.04 to 2.89, respectively). In the same time period, scores for the waiting list control groups remained flat (from 4.08 at baseline to 3.99).

At the end of treatment and at the 60-week follow-up, patients in both forms of CBT-E showed significant improvement across all measures, with no significant difference between treatments. By the end of treatment, 66.4% of those who completed all of the CBT sessions had global EDE scores <1.74 (considered clinically significant).

Subgroup analysis offers opportunity for fine-tuning

When analyzed separately, the patients with bulimia and those with eating disorder NOS did equally well at the end of treatment: 52.7% of those with bulimia and 53.3% of those with eating disorder NOS had global EDE scores <1.74. At the 60-week follow-up, the patients with bulimia maintained their improvement slightly more: 61.4% had global EDE scores <1.74, compared with 45.7% of the patients with eating disorder NOS.

The researchers also compared the outcomes of patients with the most complex additional psychopathology with those of patients with less complex problems. Greater complexity was defined as moderate ratings in at least 2 of the following domains: mood intolerance, clinical perfectionism, low self-esteem, and interpersonal difficulties.

Broad focus more effective for high complexity. Overall, those in the more complex subgroup did not respond as well; 48% had global EDE scores <1.74, vs 60% of those in the less complex group. However, those in the more complex subgroup did better with the broad form of CBT (at 60-week follow up, 60% had scores <1.74 with CBT-Eb, compared with 40% in the CBT-Ef treatment arm), while the less complex subgroup did better with the more tightly focused CBT-Ef. 2

WHAT’S NEW: Evidence supports CBT for NOS diagnosis

The most recent (2004) Cochrane review of “psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa and binging” included 40 RCTs of patients with bulimia, binge-eating disorder, and eating disorder NOS with recurrent binge-eating episodes (included in 7 studies). While the review confirmed that CBT is effective for bulimia and “similar syndromes,” it identified a need for larger and higher quality trials of CBT, particularly in patients with eating disorder NOS.1 The study reviewed in this PURL—the first large, high-quality trial to include a number of patients with eating disorder NOS—provides strong evidence that CBT is effective for this group of patients.2

CAVEATS: Limited wait time leaves unanswered questions

One limitation of this study is the lack of a control group beyond the 8-week waiting period. Prior studies of CBT for bulimia that delayed therapy for those in the control groups for a longer duration have consistently shown that patients receiving CBT did significantly better than those in the control group.9 While a “no treatment” group would have made the results more robust in this case, it would not have been ethical to withhold treatment for the entire length of the study.

It is noteworthy, too, that this study only included patients with a BMI >17.5. Patients with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, who by definition have a lower BMI, will need other treatments, including hospitalization in some cases.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Identifying patients and therapists

The primary challenge is to determine which of your patients have eating disorders. When discussing diet, adding a simple question such as, “Are you happy with your current weight?” can help you identify those who meet the criteria for an eating disorder or are at high risk.3

Identifying local mental health providers who are trained to provide CBT for patients with eating disorders is another concern. Insurance coverage for this intensive treatment may also be a limiting factor in some cases.

Many studies support the use of fluoxetine for patients with bulimia, and combined treatment with SSRIs and CBT has been shown to be superior to either treatment alone.8,10,14 Consider starting the patient on an antidepressant while she (or he) awaits the start of CBT.

Acknowledgements

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURLs) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

1. Hay PJ, Bacaltchuk J, Stefano S. Psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa and binging. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000562.

2. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, et al. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: a two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:311-319.

3. Pritts SD, Susman J. Diagnosis of eating disorders in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:297-304.

4. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348-358.

5. Button EJ, Benson E, Nollett C, et al. Don’t forget EDNOS (eating disorder not otherwise specified): patterns of service use in an eating disorders service. Psychiatr Bull. 2005;29:134-136.

6. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Bohn K, et al. The severity and status of eating disorder NOS: implications for DSM-V. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1705-1715.

7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:583-595,787.

8. Berkman ND, Bulik CM, Brownley KA, et al. Management of eating disorders. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No.135. AHRQ Publication No. 06-E010. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; April 2006.

9. Shapiro JR, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, et al. Bulimia nervosa treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:321-336.

10. American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline. Treatment of patients with eating disorders. 3rd ed Available at: http://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/pracGuideTopic_12.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2009.

11. Eckert ED, Halmi KA, Marchi P, et al. Ten-year follow-up of anorexia nervosa: clinical course and outcome. Psychol Med. 1995;25:143-156.

12. Hay PJ, Bacaltchuk J, Byrnes RT, et al. Individual psychotherapy in the outpatient treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD003909.

13. Morris J, Twaddle S. Anorexia Nervosa. BMJ. 2007;334:894-898.

14. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Eating disorders: core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders. Clinical guideline 9. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG9/niceguidance/pdf/English. Accessed June 28, 2007.

1. Hay PJ, Bacaltchuk J, Stefano S. Psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa and binging. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000562.

2. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, et al. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: a two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:311-319.

3. Pritts SD, Susman J. Diagnosis of eating disorders in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:297-304.

4. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348-358.

5. Button EJ, Benson E, Nollett C, et al. Don’t forget EDNOS (eating disorder not otherwise specified): patterns of service use in an eating disorders service. Psychiatr Bull. 2005;29:134-136.

6. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Bohn K, et al. The severity and status of eating disorder NOS: implications for DSM-V. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1705-1715.

7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:583-595,787.

8. Berkman ND, Bulik CM, Brownley KA, et al. Management of eating disorders. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No.135. AHRQ Publication No. 06-E010. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; April 2006.

9. Shapiro JR, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, et al. Bulimia nervosa treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:321-336.

10. American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline. Treatment of patients with eating disorders. 3rd ed Available at: http://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/pracGuideTopic_12.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2009.

11. Eckert ED, Halmi KA, Marchi P, et al. Ten-year follow-up of anorexia nervosa: clinical course and outcome. Psychol Med. 1995;25:143-156.

12. Hay PJ, Bacaltchuk J, Byrnes RT, et al. Individual psychotherapy in the outpatient treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD003909.

13. Morris J, Twaddle S. Anorexia Nervosa. BMJ. 2007;334:894-898.

14. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Eating disorders: core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders. Clinical guideline 9. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG9/niceguidance/pdf/English. Accessed June 28, 2007.

Copyright © 2009 The Family Physicians Inquiries Network.

All rights reserved.

When to suggest this OC alternative

Recommend continuous or extended use of the transvaginal contraceptive ring to women who want fewer days of menstrual bleeding and have trouble remembering to, or prefer not to, take a daily pill. If breakthrough bleeding is troublesome, suggest a 4-day ring-free interval.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a single randomized controlled trial (RCT) with <80% follow up.

Sulak PJ, Smith V, Coffee A, et al. Frequency and management of breakthrough bleeding with continuous use of the transvaginal contraceptive ring: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:563-571.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Case 1: A healthy 25-year-old woman comes to see you because she’s worried about getting pregnant. She’s been on an extended-cycle oral contraceptive (OC) for several months and is happy to have her period only once every 3 months, but she frequently forgets to take her pill.

What can you offer that will give her the benefits of an extended-cycle OC, without the risk of pregnancy she incurs each time she misses a pill?

Case 2: You started a healthy 18-year-old on the transvaginal ring 6 months ago. After counseling, she opted for continuous cycling, so she inserts a new ring right after she removes the old one, on the same date each month. Although she likes the ring, she’s disturbed by a recent increase in breakthrough bleeding. What can you recommend to decrease the bleeding?

Clinicians have long known that the traditional 21/7 OC cycle is not necessary for safety or efficacy. More recently, many women have been happy to learn that there is no physiologic reason to have a monthly period when they’re using combination hormonal contraception. They’re also happy to discover that fewer periods often mean fewer premenstrual mood swings, episodes of painful cramping, and instances of other troublesome symptoms.

The transvaginal ring is often overlooked

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 2 combination OCs for extended-cycle use and 1 for continuous use. But any monophasic OC can be used off-label for extended or continuous cycling to decrease bleeding frequency. So, too, can the transvaginal contraceptive ring (NuvaRing), an infrequently used contraceptive. (According to 1 study, just 5.7% of US women using contraception used either the ring or the patch.2 ) The ring has been studied for extended use,3 but does not have FDA approval for longer-term regimens.

NuvaRing is a flexible, transparent device that contains the progestin etonogestrel and ethinyl estradiol. The manufacturer recommends a 21/7 cycle, inserting the ring in the vagina and leaving it in place for 3 weeks, removing it for 1 week, and then inserting a new ring.4 The ring is well suited to women who have no contraindications to hormonal contraception but have difficulty remembering to take a pill every day—or simply prefer the convenience of less frequent dosing.

While the ring has been found to be effective and tolerable when used without a hormone-free interval—28-, 49-, 91- and 364-day dosing has been studied—breakthrough bleeding or spotting is a frequent side effect of extended-cycle hormonal contraception. In 1 study, 43% of women on a 49-day ring cycle experienced breakthrough bleeding, compared with 16% of those on a 28-day cycle.3

High satisfaction, low risk

Nonetheless, women who use the transvaginal ring often report high satisfaction. One study found that 61% of women were very satisfied with this method of contraception, compared with 34% of triphasic OC users (P<.003).5 The risk of pregnancy (1-2 pregnancies per 100 women-years of use, according to the manufacturer4 ) and the risk of venous thromboembolism (10-30 in 100,000 vs 4-11 in 100,000 nonpregnant women who are not using hormonal contraception) are comparable to that of women using OCs.6,7 The risk of other severe side effects associated with the vaginal ring is comparable to that of OCs, as well.

STUDY SUMMARY: An effective option that women used post-trial

This RCT recruited women between the ages of 18 and 45 years who had been using combination hormonal contraceptives—OCs, the transdermal patch, or the transvaginal ring. All had been on a 21/7 cycle for at least 2 months. Exclusion criteria included a body mass index ≥38 kg/m2, smoking >10 cigarettes per day, use of other estrogen- or phytoestrogen-containing products, and the presence of ovarian cysts >2.5 cm or endometrial thickness >8 mm. Women who wanted to get pregnant within a year were also excluded.

The study began with a baseline phase during which participants completed one 21/7 cycle with the ring for those using the ring prior to the study or two 21/7 cycles for those using the pill or patch prior to the study. Daily flow was assessed during this initial phase, using a scale of 0 to 4, with 4 being the heaviest. Women who completed this phase and wanted to continue using the ring (N=74) were then randomized into 2 groups (n=37) for the 6-month extended phase.

Group 1 was assigned to use the contraceptive ring with no hormone-free days. Participants were instructed to replace the rings monthly, on the same calendar day of the month. Group 2 also used the ring on a continuous basis with monthly replacement, but those who experienced breakthrough bleeding for more than 5 days were permitted to remove the ring for 4 days. Women in both groups kept a daily diary of ring usage, degree of menstrual flow, and symptomatology, including pelvic pain, headaches, and mood.

Most subjects were white (76%), nonsmokers (84%), and unmarried (68% in Group 1 and 57% in Group 2), with an average age of 28 to 29 years. Eight patients (22%) in Group 1 withdrew from the study prior to completing the 6-month extended phase, 4 of them because of side effects. Only 1 woman withdrew from Group 2, because of plans for pregnancy. No one became pregnant while using the ring.

Hormone-free interval reduced bleeding. In Group 1, the average daily flow score was slightly reduced with continuous use (from 0.33 during the 21/7 baseline phase to 0.21 in the 6-month extended phase), but researchers reported no significant difference in flow-free days. On average, 85% of the days were flow-free in the 21/7 phase, vs 89% in the extended phase.

In Group 2, flow-free days increased, from 83% in the baseline phase to 95% in the extended phase, and average flow scores fell from 0.38 to 0.17.

Overall, the 65 participants who completed 6 months of continuous ring use had fewer bleeding days per month—1.8 days, on average, vs 3.3 days during the initial 21/7 phase, but more days of spotting per month (2.5 vs 1.8 days). There was no difference between Groups 1 and 2 in pelvic pain, headache, or mood scores, and no significant difference in headache or mood scores between the baseline and continuous phases of the trial. Pelvic pain scores were lower during the extended phase, however—0.18 vs 0.32 on a scale of 0 to 10.

A high continuation rate. After the 6-month extended phase, 57 of the 65 remaining participants chose to continue using the ring for contraception, on a continuous dosing basis—a continuation rate of 88%. But more than half of the women who chose to stick with the ring (57%) decided not to take advantage of the 4-day hormone-free interval to manage breakthrough bleeding or spotting, regardless of original group assignment.

WHAT’S NEW?: The ring moves further mainstream

Continuous or extended use of the transvaginal ring may be a new idea for many patients—and physicians. But the idea may catch on in light of this study’s findings. Given the high rate of unwanted pregnancy in the United States, many women may benefit from a contraceptive that is as safe and effective as an OC but doesn’t involve a daily pill.

CAVEATS: Side effects, off-label concerns

In 2005, Oddsson et al found that women who used the ring reported more vaginitis and more leukorrhea than women who used OCs; conversely, they reported less nausea and less acne. Other side effects that are common to hormonal contraceptives, such as headache and weight gain, occurred at similar rates among women using the ring and OCs.6

However, the high proportion of patients who elected to keep using the ring at the end of the study by Sulak et al suggests that its side effects are acceptable.1 As with all contraception, however, patient preference is a key consideration. The study population was highly motivated, particularly since women who had difficulty with this means of contraception dropped out after the baseline phase of the trial.

Off-label use. Pharmacokinetic research involving the contraceptive ring has shown that hormone levels required to protect against pregnancy persist for at least 35 days after it is placed in the vagina.8 The manufacturer has data only to confirm contraceptive efficacy for up to 28 days and therefore does not recommend use beyond 4 weeks.4

This study highlights another off-label issue: Women in Group 2, who were allowed to remove the ring for 4 day-intervals to decrease breakthrough bleeding, were instructed to reinsert the same ring after 4 days and keep it in place until the next scheduled replacement date. But the manufacturer does not recommend reinsertion of a ring that has been out of the body for more than 3 hours. In my practice (KR), women are generally unwilling to store and replace a ring, preferring to place a new one after removal for more than a few hours.

Should she try continuous use?

Changing the ring on the same date each month may boost adherence for some women. Funding. The research was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Organon, Inc, the manufacturer of NuvaRing, which included salary support for 5 of the 6 authors. The published study gives no additional information about the involvement of the pharmaceutical company.

Contraindications, drug interactions. As with other combined hormonal contraceptives, women who have a history of venous thromboembolism, headaches with focal neurological symptoms, severe hypertension, breast or endometrial cancer, or liver disease, and smokers older than 35 years should not use the contraceptive ring.4 In addition, women need to be aware that a number of medications—griseofulvin, rifampin, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and herbal products containing St. John’s Wort, among others—may reduce the effectiveness of the contraceptive ring.4

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Going off-label isn’t for everyone

When it comes to choosing a contraceptive method, patient preference is paramount. Some women may not be comfortable inserting or removing the ring and should be counseled on other forms of contraception. Women who prefer to bleed every month should not use extended cycling. Similarly, some physicians may not be comfortable recommending an off-label use of the ring.

Those who are comfortable making the recommendation should be prepared to educate patients about this method of contraception and to discuss the benefits of extended or continuous use of the ring. For some women, the memory-triggering mechanism of changing the ring on the same date each month may boost adherence. For others, replacing the ring every 28 days may be acceptable—again, depending on patient preference.

Acknowledgements

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURLs) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

1. Sulak PJ, Smith V, Coffee A, et al. Frequency and management of breakthrough bleeding with continuous use of the transvaginal contraceptive ring: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:563-571.

2. Frost JJ, Singh S, Finer LB. US women’s one-year contraceptive use patterns, 2004. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39:48-55.

3. Miller L, Verhoeven C, Hout J. Extended regimens of the contraceptive vaginal ring: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:473-482.

4. NuvaRing (etonogestrel/ethinyl estradiol vaginal ring) [prescribing information]. Roseland, NJ: Organon USA Inc; June 2008. Available at: http://www.spfiles.com/pinuvaring.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2009.

5. Schafer JE, Osborne LM, Davis AR, et al. Acceptability and satisfaction using Quick Start with the contraceptive vaginal ring versus an oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2006;73:488-492.

6. Oddsson K, Leifels-Fischer B, de Melo NR, et al. Efficacy and safety of a contraceptive vaginal ring (NuvaRing) compared with a combined oral contraceptive: a 1-year randomized trial. Contraception. 2005;71:176-182.

7. Wilks JF. Hormonal birth control and pregnancy: a comparative analysis of thromboembolic risk. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:912-916.

8. Timmer C, Mulders T. Pharmacokinetics of etonogestrel and ethinylestradiol released from a combined contraceptive vaginal ring. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2000;39:233-242.

Recommend continuous or extended use of the transvaginal contraceptive ring to women who want fewer days of menstrual bleeding and have trouble remembering to, or prefer not to, take a daily pill. If breakthrough bleeding is troublesome, suggest a 4-day ring-free interval.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a single randomized controlled trial (RCT) with <80% follow up.

Sulak PJ, Smith V, Coffee A, et al. Frequency and management of breakthrough bleeding with continuous use of the transvaginal contraceptive ring: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:563-571.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Case 1: A healthy 25-year-old woman comes to see you because she’s worried about getting pregnant. She’s been on an extended-cycle oral contraceptive (OC) for several months and is happy to have her period only once every 3 months, but she frequently forgets to take her pill.

What can you offer that will give her the benefits of an extended-cycle OC, without the risk of pregnancy she incurs each time she misses a pill?

Case 2: You started a healthy 18-year-old on the transvaginal ring 6 months ago. After counseling, she opted for continuous cycling, so she inserts a new ring right after she removes the old one, on the same date each month. Although she likes the ring, she’s disturbed by a recent increase in breakthrough bleeding. What can you recommend to decrease the bleeding?

Clinicians have long known that the traditional 21/7 OC cycle is not necessary for safety or efficacy. More recently, many women have been happy to learn that there is no physiologic reason to have a monthly period when they’re using combination hormonal contraception. They’re also happy to discover that fewer periods often mean fewer premenstrual mood swings, episodes of painful cramping, and instances of other troublesome symptoms.

The transvaginal ring is often overlooked

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 2 combination OCs for extended-cycle use and 1 for continuous use. But any monophasic OC can be used off-label for extended or continuous cycling to decrease bleeding frequency. So, too, can the transvaginal contraceptive ring (NuvaRing), an infrequently used contraceptive. (According to 1 study, just 5.7% of US women using contraception used either the ring or the patch.2 ) The ring has been studied for extended use,3 but does not have FDA approval for longer-term regimens.

NuvaRing is a flexible, transparent device that contains the progestin etonogestrel and ethinyl estradiol. The manufacturer recommends a 21/7 cycle, inserting the ring in the vagina and leaving it in place for 3 weeks, removing it for 1 week, and then inserting a new ring.4 The ring is well suited to women who have no contraindications to hormonal contraception but have difficulty remembering to take a pill every day—or simply prefer the convenience of less frequent dosing.

While the ring has been found to be effective and tolerable when used without a hormone-free interval—28-, 49-, 91- and 364-day dosing has been studied—breakthrough bleeding or spotting is a frequent side effect of extended-cycle hormonal contraception. In 1 study, 43% of women on a 49-day ring cycle experienced breakthrough bleeding, compared with 16% of those on a 28-day cycle.3

High satisfaction, low risk

Nonetheless, women who use the transvaginal ring often report high satisfaction. One study found that 61% of women were very satisfied with this method of contraception, compared with 34% of triphasic OC users (P<.003).5 The risk of pregnancy (1-2 pregnancies per 100 women-years of use, according to the manufacturer4 ) and the risk of venous thromboembolism (10-30 in 100,000 vs 4-11 in 100,000 nonpregnant women who are not using hormonal contraception) are comparable to that of women using OCs.6,7 The risk of other severe side effects associated with the vaginal ring is comparable to that of OCs, as well.

STUDY SUMMARY: An effective option that women used post-trial

This RCT recruited women between the ages of 18 and 45 years who had been using combination hormonal contraceptives—OCs, the transdermal patch, or the transvaginal ring. All had been on a 21/7 cycle for at least 2 months. Exclusion criteria included a body mass index ≥38 kg/m2, smoking >10 cigarettes per day, use of other estrogen- or phytoestrogen-containing products, and the presence of ovarian cysts >2.5 cm or endometrial thickness >8 mm. Women who wanted to get pregnant within a year were also excluded.

The study began with a baseline phase during which participants completed one 21/7 cycle with the ring for those using the ring prior to the study or two 21/7 cycles for those using the pill or patch prior to the study. Daily flow was assessed during this initial phase, using a scale of 0 to 4, with 4 being the heaviest. Women who completed this phase and wanted to continue using the ring (N=74) were then randomized into 2 groups (n=37) for the 6-month extended phase.

Group 1 was assigned to use the contraceptive ring with no hormone-free days. Participants were instructed to replace the rings monthly, on the same calendar day of the month. Group 2 also used the ring on a continuous basis with monthly replacement, but those who experienced breakthrough bleeding for more than 5 days were permitted to remove the ring for 4 days. Women in both groups kept a daily diary of ring usage, degree of menstrual flow, and symptomatology, including pelvic pain, headaches, and mood.

Most subjects were white (76%), nonsmokers (84%), and unmarried (68% in Group 1 and 57% in Group 2), with an average age of 28 to 29 years. Eight patients (22%) in Group 1 withdrew from the study prior to completing the 6-month extended phase, 4 of them because of side effects. Only 1 woman withdrew from Group 2, because of plans for pregnancy. No one became pregnant while using the ring.

Hormone-free interval reduced bleeding. In Group 1, the average daily flow score was slightly reduced with continuous use (from 0.33 during the 21/7 baseline phase to 0.21 in the 6-month extended phase), but researchers reported no significant difference in flow-free days. On average, 85% of the days were flow-free in the 21/7 phase, vs 89% in the extended phase.

In Group 2, flow-free days increased, from 83% in the baseline phase to 95% in the extended phase, and average flow scores fell from 0.38 to 0.17.

Overall, the 65 participants who completed 6 months of continuous ring use had fewer bleeding days per month—1.8 days, on average, vs 3.3 days during the initial 21/7 phase, but more days of spotting per month (2.5 vs 1.8 days). There was no difference between Groups 1 and 2 in pelvic pain, headache, or mood scores, and no significant difference in headache or mood scores between the baseline and continuous phases of the trial. Pelvic pain scores were lower during the extended phase, however—0.18 vs 0.32 on a scale of 0 to 10.

A high continuation rate. After the 6-month extended phase, 57 of the 65 remaining participants chose to continue using the ring for contraception, on a continuous dosing basis—a continuation rate of 88%. But more than half of the women who chose to stick with the ring (57%) decided not to take advantage of the 4-day hormone-free interval to manage breakthrough bleeding or spotting, regardless of original group assignment.

WHAT’S NEW?: The ring moves further mainstream

Continuous or extended use of the transvaginal ring may be a new idea for many patients—and physicians. But the idea may catch on in light of this study’s findings. Given the high rate of unwanted pregnancy in the United States, many women may benefit from a contraceptive that is as safe and effective as an OC but doesn’t involve a daily pill.

CAVEATS: Side effects, off-label concerns

In 2005, Oddsson et al found that women who used the ring reported more vaginitis and more leukorrhea than women who used OCs; conversely, they reported less nausea and less acne. Other side effects that are common to hormonal contraceptives, such as headache and weight gain, occurred at similar rates among women using the ring and OCs.6

However, the high proportion of patients who elected to keep using the ring at the end of the study by Sulak et al suggests that its side effects are acceptable.1 As with all contraception, however, patient preference is a key consideration. The study population was highly motivated, particularly since women who had difficulty with this means of contraception dropped out after the baseline phase of the trial.

Off-label use. Pharmacokinetic research involving the contraceptive ring has shown that hormone levels required to protect against pregnancy persist for at least 35 days after it is placed in the vagina.8 The manufacturer has data only to confirm contraceptive efficacy for up to 28 days and therefore does not recommend use beyond 4 weeks.4

This study highlights another off-label issue: Women in Group 2, who were allowed to remove the ring for 4 day-intervals to decrease breakthrough bleeding, were instructed to reinsert the same ring after 4 days and keep it in place until the next scheduled replacement date. But the manufacturer does not recommend reinsertion of a ring that has been out of the body for more than 3 hours. In my practice (KR), women are generally unwilling to store and replace a ring, preferring to place a new one after removal for more than a few hours.

Should she try continuous use?

Changing the ring on the same date each month may boost adherence for some women. Funding. The research was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Organon, Inc, the manufacturer of NuvaRing, which included salary support for 5 of the 6 authors. The published study gives no additional information about the involvement of the pharmaceutical company.

Contraindications, drug interactions. As with other combined hormonal contraceptives, women who have a history of venous thromboembolism, headaches with focal neurological symptoms, severe hypertension, breast or endometrial cancer, or liver disease, and smokers older than 35 years should not use the contraceptive ring.4 In addition, women need to be aware that a number of medications—griseofulvin, rifampin, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and herbal products containing St. John’s Wort, among others—may reduce the effectiveness of the contraceptive ring.4

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Going off-label isn’t for everyone

When it comes to choosing a contraceptive method, patient preference is paramount. Some women may not be comfortable inserting or removing the ring and should be counseled on other forms of contraception. Women who prefer to bleed every month should not use extended cycling. Similarly, some physicians may not be comfortable recommending an off-label use of the ring.

Those who are comfortable making the recommendation should be prepared to educate patients about this method of contraception and to discuss the benefits of extended or continuous use of the ring. For some women, the memory-triggering mechanism of changing the ring on the same date each month may boost adherence. For others, replacing the ring every 28 days may be acceptable—again, depending on patient preference.

Acknowledgements

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURLs) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

Recommend continuous or extended use of the transvaginal contraceptive ring to women who want fewer days of menstrual bleeding and have trouble remembering to, or prefer not to, take a daily pill. If breakthrough bleeding is troublesome, suggest a 4-day ring-free interval.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a single randomized controlled trial (RCT) with <80% follow up.

Sulak PJ, Smith V, Coffee A, et al. Frequency and management of breakthrough bleeding with continuous use of the transvaginal contraceptive ring: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:563-571.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Case 1: A healthy 25-year-old woman comes to see you because she’s worried about getting pregnant. She’s been on an extended-cycle oral contraceptive (OC) for several months and is happy to have her period only once every 3 months, but she frequently forgets to take her pill.

What can you offer that will give her the benefits of an extended-cycle OC, without the risk of pregnancy she incurs each time she misses a pill?

Case 2: You started a healthy 18-year-old on the transvaginal ring 6 months ago. After counseling, she opted for continuous cycling, so she inserts a new ring right after she removes the old one, on the same date each month. Although she likes the ring, she’s disturbed by a recent increase in breakthrough bleeding. What can you recommend to decrease the bleeding?

Clinicians have long known that the traditional 21/7 OC cycle is not necessary for safety or efficacy. More recently, many women have been happy to learn that there is no physiologic reason to have a monthly period when they’re using combination hormonal contraception. They’re also happy to discover that fewer periods often mean fewer premenstrual mood swings, episodes of painful cramping, and instances of other troublesome symptoms.

The transvaginal ring is often overlooked

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 2 combination OCs for extended-cycle use and 1 for continuous use. But any monophasic OC can be used off-label for extended or continuous cycling to decrease bleeding frequency. So, too, can the transvaginal contraceptive ring (NuvaRing), an infrequently used contraceptive. (According to 1 study, just 5.7% of US women using contraception used either the ring or the patch.2 ) The ring has been studied for extended use,3 but does not have FDA approval for longer-term regimens.

NuvaRing is a flexible, transparent device that contains the progestin etonogestrel and ethinyl estradiol. The manufacturer recommends a 21/7 cycle, inserting the ring in the vagina and leaving it in place for 3 weeks, removing it for 1 week, and then inserting a new ring.4 The ring is well suited to women who have no contraindications to hormonal contraception but have difficulty remembering to take a pill every day—or simply prefer the convenience of less frequent dosing.

While the ring has been found to be effective and tolerable when used without a hormone-free interval—28-, 49-, 91- and 364-day dosing has been studied—breakthrough bleeding or spotting is a frequent side effect of extended-cycle hormonal contraception. In 1 study, 43% of women on a 49-day ring cycle experienced breakthrough bleeding, compared with 16% of those on a 28-day cycle.3

High satisfaction, low risk

Nonetheless, women who use the transvaginal ring often report high satisfaction. One study found that 61% of women were very satisfied with this method of contraception, compared with 34% of triphasic OC users (P<.003).5 The risk of pregnancy (1-2 pregnancies per 100 women-years of use, according to the manufacturer4 ) and the risk of venous thromboembolism (10-30 in 100,000 vs 4-11 in 100,000 nonpregnant women who are not using hormonal contraception) are comparable to that of women using OCs.6,7 The risk of other severe side effects associated with the vaginal ring is comparable to that of OCs, as well.

STUDY SUMMARY: An effective option that women used post-trial

This RCT recruited women between the ages of 18 and 45 years who had been using combination hormonal contraceptives—OCs, the transdermal patch, or the transvaginal ring. All had been on a 21/7 cycle for at least 2 months. Exclusion criteria included a body mass index ≥38 kg/m2, smoking >10 cigarettes per day, use of other estrogen- or phytoestrogen-containing products, and the presence of ovarian cysts >2.5 cm or endometrial thickness >8 mm. Women who wanted to get pregnant within a year were also excluded.

The study began with a baseline phase during which participants completed one 21/7 cycle with the ring for those using the ring prior to the study or two 21/7 cycles for those using the pill or patch prior to the study. Daily flow was assessed during this initial phase, using a scale of 0 to 4, with 4 being the heaviest. Women who completed this phase and wanted to continue using the ring (N=74) were then randomized into 2 groups (n=37) for the 6-month extended phase.

Group 1 was assigned to use the contraceptive ring with no hormone-free days. Participants were instructed to replace the rings monthly, on the same calendar day of the month. Group 2 also used the ring on a continuous basis with monthly replacement, but those who experienced breakthrough bleeding for more than 5 days were permitted to remove the ring for 4 days. Women in both groups kept a daily diary of ring usage, degree of menstrual flow, and symptomatology, including pelvic pain, headaches, and mood.

Most subjects were white (76%), nonsmokers (84%), and unmarried (68% in Group 1 and 57% in Group 2), with an average age of 28 to 29 years. Eight patients (22%) in Group 1 withdrew from the study prior to completing the 6-month extended phase, 4 of them because of side effects. Only 1 woman withdrew from Group 2, because of plans for pregnancy. No one became pregnant while using the ring.

Hormone-free interval reduced bleeding. In Group 1, the average daily flow score was slightly reduced with continuous use (from 0.33 during the 21/7 baseline phase to 0.21 in the 6-month extended phase), but researchers reported no significant difference in flow-free days. On average, 85% of the days were flow-free in the 21/7 phase, vs 89% in the extended phase.

In Group 2, flow-free days increased, from 83% in the baseline phase to 95% in the extended phase, and average flow scores fell from 0.38 to 0.17.

Overall, the 65 participants who completed 6 months of continuous ring use had fewer bleeding days per month—1.8 days, on average, vs 3.3 days during the initial 21/7 phase, but more days of spotting per month (2.5 vs 1.8 days). There was no difference between Groups 1 and 2 in pelvic pain, headache, or mood scores, and no significant difference in headache or mood scores between the baseline and continuous phases of the trial. Pelvic pain scores were lower during the extended phase, however—0.18 vs 0.32 on a scale of 0 to 10.

A high continuation rate. After the 6-month extended phase, 57 of the 65 remaining participants chose to continue using the ring for contraception, on a continuous dosing basis—a continuation rate of 88%. But more than half of the women who chose to stick with the ring (57%) decided not to take advantage of the 4-day hormone-free interval to manage breakthrough bleeding or spotting, regardless of original group assignment.

WHAT’S NEW?: The ring moves further mainstream

Continuous or extended use of the transvaginal ring may be a new idea for many patients—and physicians. But the idea may catch on in light of this study’s findings. Given the high rate of unwanted pregnancy in the United States, many women may benefit from a contraceptive that is as safe and effective as an OC but doesn’t involve a daily pill.

CAVEATS: Side effects, off-label concerns

In 2005, Oddsson et al found that women who used the ring reported more vaginitis and more leukorrhea than women who used OCs; conversely, they reported less nausea and less acne. Other side effects that are common to hormonal contraceptives, such as headache and weight gain, occurred at similar rates among women using the ring and OCs.6

However, the high proportion of patients who elected to keep using the ring at the end of the study by Sulak et al suggests that its side effects are acceptable.1 As with all contraception, however, patient preference is a key consideration. The study population was highly motivated, particularly since women who had difficulty with this means of contraception dropped out after the baseline phase of the trial.

Off-label use. Pharmacokinetic research involving the contraceptive ring has shown that hormone levels required to protect against pregnancy persist for at least 35 days after it is placed in the vagina.8 The manufacturer has data only to confirm contraceptive efficacy for up to 28 days and therefore does not recommend use beyond 4 weeks.4