User login

Locally Acquired Dengue Case Confirmed in California

A case of locally acquired dengue fever has been confirmed in a resident of Baldwin Park, California, according to a press release from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

“Dengue is the most common insect-borne viral infection in the world, with a wide geographic spread; we know that we have mosquitoes capable of carrying and transmitting the virus in the United States already, and Los Angeles county is a major epicenter for international travel and trade,” James Lawler, MD, associate director for International Programs and Innovation at the Global Center for Health Security and professor in the Infectious Diseases Division at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, said in an interview.

Although the patient had no known history of travel to a dengue-endemic area, the potential risk for widespread transmission of the virus in the Los Angeles County area remains low, and no additional suspected cases of locally acquired dengue have been identified, according to the release. However, the recent cases highlight the need for vigilance on the part of the public to reduce transmission of mosquito-borne infections, the public health department noted.

Most cases of dengue occur in people who have traveled to areas where the disease is more common, mainly tropical and subtropical areas, according to the press release. However, the types of mosquitoes that spread dengue exist in parts of the United States, so locally acquired infections can occur.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an official health advisory in June 2024 about an increased risk for dengue infections in the United States. According to the advisory, 745 cases of dengue were identified in US travelers to endemic areas between January 1, 2024, and June 24, 2024.

The CDC advises clinicians to maintain a high level of suspicion for dengue among individuals with fever and recent travel to areas with frequent dengue transmission, but also to consider locally acquired disease in areas of mosquito vectors.

In clinical practice, dengue may be difficult to differentiate from other febrile systemic infections, Dr. Lawler noted. “Joint pain, low back pain, and headache (often retro-orbital) are common and can be severe, and a rash often appears several days into illness,” he noted.

Do not delay treatment in suspected cases while waiting for test results, the CDC emphasized in the advisory. Food and Drug Administration–approved tests for dengue include RT-PCR and IgM antibody tests or NS1 and IgM antibody tests.

“Severe dengue can be life-threatening and progress to a hemorrhagic fever-like syndrome, and patients with severe dengue should be cared for on a high-acuity or intensive care setting, with close monitoring of labs and fluid status,” Dr. Lawler told this news organization.

The World Health Organization has published guidelines for the management of dengue, which Dr. Lawler strongly recommends to clinicians in the rare event that they are facing a severe case. The treatment for dengue is supportive care, according to the CDC; a vaccine that was deemed safe and effective is no longer being manufactured because of low demand.

Most symptoms last for 2-7 days, and most patients recover within a week, but approximately 1 in 20 may develop severe disease, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Approximately one quarter of dengue infections are symptomatic, and clinicians should know the signs of progression to severe disease, which include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, clinical fluid accumulation, mucosal bleeding, lethargy or restlessness, and liver enlargement, according to the CDC.

Local Dengue Not Unexpected

“Sadly, I am not surprised at another locally acquired case of dengue fever in the United States,” said Dr. Lawler. “We also have seen a trend of more historically tropical, insect-borne diseases popping up with locally acquired cases in the United States,” he noted.

Dr. Lawler suggested that “the erosion of state and local public health” is a major contributor to the increase in dengue cases. For more than 100 years, activities of state and local public health officials had significantly curtailed mosquito-borne diseases through aggressive control programs, “but we seem to be losing ground over the last several years,” he said.

“Locally acquired dengue cases are still rare in the United States,” he added. “However, people can protect themselves against dengue and more common arthropod-borne infections by taking precautions to cover up and wear insect repellent while outdoors.”

In addition, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health emphasized in its press release that local residents reduce their risk for contact with mosquitoes by removing areas of standing water on their property and ensuring well-fitted screens on doors and windows.

Dr. Lawler had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A case of locally acquired dengue fever has been confirmed in a resident of Baldwin Park, California, according to a press release from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

“Dengue is the most common insect-borne viral infection in the world, with a wide geographic spread; we know that we have mosquitoes capable of carrying and transmitting the virus in the United States already, and Los Angeles county is a major epicenter for international travel and trade,” James Lawler, MD, associate director for International Programs and Innovation at the Global Center for Health Security and professor in the Infectious Diseases Division at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, said in an interview.

Although the patient had no known history of travel to a dengue-endemic area, the potential risk for widespread transmission of the virus in the Los Angeles County area remains low, and no additional suspected cases of locally acquired dengue have been identified, according to the release. However, the recent cases highlight the need for vigilance on the part of the public to reduce transmission of mosquito-borne infections, the public health department noted.

Most cases of dengue occur in people who have traveled to areas where the disease is more common, mainly tropical and subtropical areas, according to the press release. However, the types of mosquitoes that spread dengue exist in parts of the United States, so locally acquired infections can occur.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an official health advisory in June 2024 about an increased risk for dengue infections in the United States. According to the advisory, 745 cases of dengue were identified in US travelers to endemic areas between January 1, 2024, and June 24, 2024.

The CDC advises clinicians to maintain a high level of suspicion for dengue among individuals with fever and recent travel to areas with frequent dengue transmission, but also to consider locally acquired disease in areas of mosquito vectors.

In clinical practice, dengue may be difficult to differentiate from other febrile systemic infections, Dr. Lawler noted. “Joint pain, low back pain, and headache (often retro-orbital) are common and can be severe, and a rash often appears several days into illness,” he noted.

Do not delay treatment in suspected cases while waiting for test results, the CDC emphasized in the advisory. Food and Drug Administration–approved tests for dengue include RT-PCR and IgM antibody tests or NS1 and IgM antibody tests.

“Severe dengue can be life-threatening and progress to a hemorrhagic fever-like syndrome, and patients with severe dengue should be cared for on a high-acuity or intensive care setting, with close monitoring of labs and fluid status,” Dr. Lawler told this news organization.

The World Health Organization has published guidelines for the management of dengue, which Dr. Lawler strongly recommends to clinicians in the rare event that they are facing a severe case. The treatment for dengue is supportive care, according to the CDC; a vaccine that was deemed safe and effective is no longer being manufactured because of low demand.

Most symptoms last for 2-7 days, and most patients recover within a week, but approximately 1 in 20 may develop severe disease, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Approximately one quarter of dengue infections are symptomatic, and clinicians should know the signs of progression to severe disease, which include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, clinical fluid accumulation, mucosal bleeding, lethargy or restlessness, and liver enlargement, according to the CDC.

Local Dengue Not Unexpected

“Sadly, I am not surprised at another locally acquired case of dengue fever in the United States,” said Dr. Lawler. “We also have seen a trend of more historically tropical, insect-borne diseases popping up with locally acquired cases in the United States,” he noted.

Dr. Lawler suggested that “the erosion of state and local public health” is a major contributor to the increase in dengue cases. For more than 100 years, activities of state and local public health officials had significantly curtailed mosquito-borne diseases through aggressive control programs, “but we seem to be losing ground over the last several years,” he said.

“Locally acquired dengue cases are still rare in the United States,” he added. “However, people can protect themselves against dengue and more common arthropod-borne infections by taking precautions to cover up and wear insect repellent while outdoors.”

In addition, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health emphasized in its press release that local residents reduce their risk for contact with mosquitoes by removing areas of standing water on their property and ensuring well-fitted screens on doors and windows.

Dr. Lawler had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A case of locally acquired dengue fever has been confirmed in a resident of Baldwin Park, California, according to a press release from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

“Dengue is the most common insect-borne viral infection in the world, with a wide geographic spread; we know that we have mosquitoes capable of carrying and transmitting the virus in the United States already, and Los Angeles county is a major epicenter for international travel and trade,” James Lawler, MD, associate director for International Programs and Innovation at the Global Center for Health Security and professor in the Infectious Diseases Division at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, said in an interview.

Although the patient had no known history of travel to a dengue-endemic area, the potential risk for widespread transmission of the virus in the Los Angeles County area remains low, and no additional suspected cases of locally acquired dengue have been identified, according to the release. However, the recent cases highlight the need for vigilance on the part of the public to reduce transmission of mosquito-borne infections, the public health department noted.

Most cases of dengue occur in people who have traveled to areas where the disease is more common, mainly tropical and subtropical areas, according to the press release. However, the types of mosquitoes that spread dengue exist in parts of the United States, so locally acquired infections can occur.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an official health advisory in June 2024 about an increased risk for dengue infections in the United States. According to the advisory, 745 cases of dengue were identified in US travelers to endemic areas between January 1, 2024, and June 24, 2024.

The CDC advises clinicians to maintain a high level of suspicion for dengue among individuals with fever and recent travel to areas with frequent dengue transmission, but also to consider locally acquired disease in areas of mosquito vectors.

In clinical practice, dengue may be difficult to differentiate from other febrile systemic infections, Dr. Lawler noted. “Joint pain, low back pain, and headache (often retro-orbital) are common and can be severe, and a rash often appears several days into illness,” he noted.

Do not delay treatment in suspected cases while waiting for test results, the CDC emphasized in the advisory. Food and Drug Administration–approved tests for dengue include RT-PCR and IgM antibody tests or NS1 and IgM antibody tests.

“Severe dengue can be life-threatening and progress to a hemorrhagic fever-like syndrome, and patients with severe dengue should be cared for on a high-acuity or intensive care setting, with close monitoring of labs and fluid status,” Dr. Lawler told this news organization.

The World Health Organization has published guidelines for the management of dengue, which Dr. Lawler strongly recommends to clinicians in the rare event that they are facing a severe case. The treatment for dengue is supportive care, according to the CDC; a vaccine that was deemed safe and effective is no longer being manufactured because of low demand.

Most symptoms last for 2-7 days, and most patients recover within a week, but approximately 1 in 20 may develop severe disease, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Approximately one quarter of dengue infections are symptomatic, and clinicians should know the signs of progression to severe disease, which include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, clinical fluid accumulation, mucosal bleeding, lethargy or restlessness, and liver enlargement, according to the CDC.

Local Dengue Not Unexpected

“Sadly, I am not surprised at another locally acquired case of dengue fever in the United States,” said Dr. Lawler. “We also have seen a trend of more historically tropical, insect-borne diseases popping up with locally acquired cases in the United States,” he noted.

Dr. Lawler suggested that “the erosion of state and local public health” is a major contributor to the increase in dengue cases. For more than 100 years, activities of state and local public health officials had significantly curtailed mosquito-borne diseases through aggressive control programs, “but we seem to be losing ground over the last several years,” he said.

“Locally acquired dengue cases are still rare in the United States,” he added. “However, people can protect themselves against dengue and more common arthropod-borne infections by taking precautions to cover up and wear insect repellent while outdoors.”

In addition, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health emphasized in its press release that local residents reduce their risk for contact with mosquitoes by removing areas of standing water on their property and ensuring well-fitted screens on doors and windows.

Dr. Lawler had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Controversy Surrounds Optimal Treatment for High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism

VIENNA — The optimal course of treatment when managing acute, high-risk pulmonary embolism (PE) remains a contentious topic among respiratory specialists.

Systemic thrombolysis, specifically using recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA), is the current gold standard treatment for high-risk PE. However, the real-world application is less straightforward due to patient complexities.

Here at the European Respiratory Society (ERS) 2024 Congress, respiratory specialists presented contrasting viewpoints and the latest evidence on each side of the issue to provide a comprehensive framework for navigating the complex decision-making process required for effective treatment.

“High-risk PE is a mechanical problem and thus needs a mechanical solution,” said Parth M. Rali, MD, an associate professor in thoracic medicine and surgery at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

“The marketing on some of the mechanical techniques is very impressive,” said Olivier Sanchez, MD, a pulmonologist in the Department of Pneumology and Intensive Care at the Georges Pompidou European Hospital in France. “But what is the evidence of such treatment in the setting of pulmonary embolism?”

The Case Against rtPA as the Standard of Care

High-risk PE typically involves hemodynamically unstable patients presenting with conditions such as low blood pressure, cardiac arrest, or the need for mechanical circulatory support. There is a spectrum of severity within high-risk PE, making it a complex condition to manage, especially since many patients have comorbidities like anemia or active cancer, complicating treatment. “It’s a very dynamic and fluid condition, and we can’t take for granted that rtPA is a standard of care,” Dr. Rali said.

Alternative treatments such as catheter-directed therapies, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and surgical embolectomy are emerging as promising options, especially for patients who do not respond to or cannot receive rtPA. Mechanical treatments offer benefits in reducing clot burden and stabilizing patients, but they come with their own challenges.

ECMO can stabilize patients who are in shock or cardiac arrest, buying time for the clot to resolve or for further interventions like surgery or catheter-based treatments, said Dr. Rali. However, it is an invasive procedure requiring cannulation of large blood vessels, often involving significant resources and expertise.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis is a minimally invasive technique where a catheter is inserted directly into the pulmonary artery to deliver thrombolytic drugs at lower doses. This method allows for more targeted treatment of the clot, reducing the risk for systemic bleeding that comes with higher doses of thrombolytic agents used in systemic therapy, Dr. Rali explained.

Dr. Rali reported results from the FLAME study, which investigated the effectiveness of FlowTriever mechanical thrombectomy compared with conventional therapies for high-risk PE. This prospective, multicenter observational study enrolled 53 patients in the FlowTriever arm and 61 in the context arm, which included patients treated with systemic thrombolysis or anticoagulation. The primary endpoint, a composite of adverse in-hospital outcomes, was reached in 17% of FlowTriever patients, significantly lower than the 32% performance goal and the 63.9% rate in the context arm. In-hospital mortality was dramatically lower in the FlowTriever arm (1.9%) compared to the context arm (29.5%).

When catheter-based treatment fails, surgical pulmonary embolectomy is a last-resort option. “Only a minority of the high-risk PE [patients] would qualify for rtPA without harmful side effects,” Dr. Rali concluded. “So think wise before you pull your trigger.”

rtPA Not a Matter of the Past

In high-risk PE, the therapeutic priority is rapid hemodynamic stabilization and restoration of pulmonary blood flow to prevent cardiovascular collapse. Systemic thrombolysis acts quickly, reducing pulmonary vascular resistance and obstruction within hours, said Dr. Sanchez.

Presenting at the ERS Congress, he reported numerous studies, including 15 randomized controlled trials that demonstrated its effectiveness in high-risk PE. The PEITHO trial, in particular, demonstrated the ability of systemic thrombolysis to reduce all-cause mortality and hemodynamic collapse within 7 days.

However, this benefit comes at the cost of increased bleeding risk, including a 10% rate of major bleeding and a 2% risk for intracranial hemorrhage. “These data come from old studies using invasive diagnostic procedures, and with current diagnostic procedures, the rate of bleeding is probably lower,” Dr. Sanchez said. The risk of bleeding is also related to the type of thrombolytic agent, with tenecteplase being strongly associated with a higher risk of bleeding, while alteplase shows no increase in the risk of major bleeding, he added. New strategies like reduced-dose thrombolysis offer comparable efficacy and improved safety, as demonstrated in ongoing trials like PEITHO-3, which aim to optimize the balance between efficacy and bleeding risk. Dr. Sanchez is the lead investigator of the PEITHO-3 study.

While rtPA might not be optimal for all patients, Dr. Sanchez thinks there is not enough evidence to replace it as a first-line treatment.

Existing studies on catheter-directed therapies often focus on surrogate endpoints, such as right-to-left ventricular ratio changes, rather than clinical outcomes like mortality, he said. Retrospective data suggest that catheter-directed therapies may reduce in-hospital mortality compared with systemic therapies, but they also increase the risk of intracranial bleeding, post-procedure complications, and device-related events.

Sanchez mentioned the same FLAME study described by Dr. Rali, which reported a 23% rate of device-related complications and 11% major bleeding in patients treated with catheter-directed therapies.

“Systemic thrombolysis remains the first treatment of choice,” Dr. Sanchez concluded. “The use of catheter-directed treatment should be discussed as an alternative in case of contraindications.”

The Debate Continues

Numerous ongoing clinical studies, such as the FLARE trial, will address gaps in evidence and refine treatment protocols, potentially reshaping the standard of care in high-risk PE in the near future by providing new data on the efficacy and safety of existing and emerging therapies.

“The coming data will make it clearer what the best option is,” said Thamer Al Khouzaie, MD, a pulmonary medicine consultant at Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. For now, he said, systemic thrombolysis remains the best option for most patients because it is widely available, easily administered with intravenous infusion, and at a limited cost. Catheter-directed treatment and surgical options are only available in specialized centers, require expertise and training, and are also very expensive.

Dr. Rali, Dr. Sanchez, and Dr. Khouzaie report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

VIENNA — The optimal course of treatment when managing acute, high-risk pulmonary embolism (PE) remains a contentious topic among respiratory specialists.

Systemic thrombolysis, specifically using recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA), is the current gold standard treatment for high-risk PE. However, the real-world application is less straightforward due to patient complexities.

Here at the European Respiratory Society (ERS) 2024 Congress, respiratory specialists presented contrasting viewpoints and the latest evidence on each side of the issue to provide a comprehensive framework for navigating the complex decision-making process required for effective treatment.

“High-risk PE is a mechanical problem and thus needs a mechanical solution,” said Parth M. Rali, MD, an associate professor in thoracic medicine and surgery at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

“The marketing on some of the mechanical techniques is very impressive,” said Olivier Sanchez, MD, a pulmonologist in the Department of Pneumology and Intensive Care at the Georges Pompidou European Hospital in France. “But what is the evidence of such treatment in the setting of pulmonary embolism?”

The Case Against rtPA as the Standard of Care

High-risk PE typically involves hemodynamically unstable patients presenting with conditions such as low blood pressure, cardiac arrest, or the need for mechanical circulatory support. There is a spectrum of severity within high-risk PE, making it a complex condition to manage, especially since many patients have comorbidities like anemia or active cancer, complicating treatment. “It’s a very dynamic and fluid condition, and we can’t take for granted that rtPA is a standard of care,” Dr. Rali said.

Alternative treatments such as catheter-directed therapies, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and surgical embolectomy are emerging as promising options, especially for patients who do not respond to or cannot receive rtPA. Mechanical treatments offer benefits in reducing clot burden and stabilizing patients, but they come with their own challenges.

ECMO can stabilize patients who are in shock or cardiac arrest, buying time for the clot to resolve or for further interventions like surgery or catheter-based treatments, said Dr. Rali. However, it is an invasive procedure requiring cannulation of large blood vessels, often involving significant resources and expertise.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis is a minimally invasive technique where a catheter is inserted directly into the pulmonary artery to deliver thrombolytic drugs at lower doses. This method allows for more targeted treatment of the clot, reducing the risk for systemic bleeding that comes with higher doses of thrombolytic agents used in systemic therapy, Dr. Rali explained.

Dr. Rali reported results from the FLAME study, which investigated the effectiveness of FlowTriever mechanical thrombectomy compared with conventional therapies for high-risk PE. This prospective, multicenter observational study enrolled 53 patients in the FlowTriever arm and 61 in the context arm, which included patients treated with systemic thrombolysis or anticoagulation. The primary endpoint, a composite of adverse in-hospital outcomes, was reached in 17% of FlowTriever patients, significantly lower than the 32% performance goal and the 63.9% rate in the context arm. In-hospital mortality was dramatically lower in the FlowTriever arm (1.9%) compared to the context arm (29.5%).

When catheter-based treatment fails, surgical pulmonary embolectomy is a last-resort option. “Only a minority of the high-risk PE [patients] would qualify for rtPA without harmful side effects,” Dr. Rali concluded. “So think wise before you pull your trigger.”

rtPA Not a Matter of the Past

In high-risk PE, the therapeutic priority is rapid hemodynamic stabilization and restoration of pulmonary blood flow to prevent cardiovascular collapse. Systemic thrombolysis acts quickly, reducing pulmonary vascular resistance and obstruction within hours, said Dr. Sanchez.

Presenting at the ERS Congress, he reported numerous studies, including 15 randomized controlled trials that demonstrated its effectiveness in high-risk PE. The PEITHO trial, in particular, demonstrated the ability of systemic thrombolysis to reduce all-cause mortality and hemodynamic collapse within 7 days.

However, this benefit comes at the cost of increased bleeding risk, including a 10% rate of major bleeding and a 2% risk for intracranial hemorrhage. “These data come from old studies using invasive diagnostic procedures, and with current diagnostic procedures, the rate of bleeding is probably lower,” Dr. Sanchez said. The risk of bleeding is also related to the type of thrombolytic agent, with tenecteplase being strongly associated with a higher risk of bleeding, while alteplase shows no increase in the risk of major bleeding, he added. New strategies like reduced-dose thrombolysis offer comparable efficacy and improved safety, as demonstrated in ongoing trials like PEITHO-3, which aim to optimize the balance between efficacy and bleeding risk. Dr. Sanchez is the lead investigator of the PEITHO-3 study.

While rtPA might not be optimal for all patients, Dr. Sanchez thinks there is not enough evidence to replace it as a first-line treatment.

Existing studies on catheter-directed therapies often focus on surrogate endpoints, such as right-to-left ventricular ratio changes, rather than clinical outcomes like mortality, he said. Retrospective data suggest that catheter-directed therapies may reduce in-hospital mortality compared with systemic therapies, but they also increase the risk of intracranial bleeding, post-procedure complications, and device-related events.

Sanchez mentioned the same FLAME study described by Dr. Rali, which reported a 23% rate of device-related complications and 11% major bleeding in patients treated with catheter-directed therapies.

“Systemic thrombolysis remains the first treatment of choice,” Dr. Sanchez concluded. “The use of catheter-directed treatment should be discussed as an alternative in case of contraindications.”

The Debate Continues

Numerous ongoing clinical studies, such as the FLARE trial, will address gaps in evidence and refine treatment protocols, potentially reshaping the standard of care in high-risk PE in the near future by providing new data on the efficacy and safety of existing and emerging therapies.

“The coming data will make it clearer what the best option is,” said Thamer Al Khouzaie, MD, a pulmonary medicine consultant at Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. For now, he said, systemic thrombolysis remains the best option for most patients because it is widely available, easily administered with intravenous infusion, and at a limited cost. Catheter-directed treatment and surgical options are only available in specialized centers, require expertise and training, and are also very expensive.

Dr. Rali, Dr. Sanchez, and Dr. Khouzaie report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

VIENNA — The optimal course of treatment when managing acute, high-risk pulmonary embolism (PE) remains a contentious topic among respiratory specialists.

Systemic thrombolysis, specifically using recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA), is the current gold standard treatment for high-risk PE. However, the real-world application is less straightforward due to patient complexities.

Here at the European Respiratory Society (ERS) 2024 Congress, respiratory specialists presented contrasting viewpoints and the latest evidence on each side of the issue to provide a comprehensive framework for navigating the complex decision-making process required for effective treatment.

“High-risk PE is a mechanical problem and thus needs a mechanical solution,” said Parth M. Rali, MD, an associate professor in thoracic medicine and surgery at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

“The marketing on some of the mechanical techniques is very impressive,” said Olivier Sanchez, MD, a pulmonologist in the Department of Pneumology and Intensive Care at the Georges Pompidou European Hospital in France. “But what is the evidence of such treatment in the setting of pulmonary embolism?”

The Case Against rtPA as the Standard of Care

High-risk PE typically involves hemodynamically unstable patients presenting with conditions such as low blood pressure, cardiac arrest, or the need for mechanical circulatory support. There is a spectrum of severity within high-risk PE, making it a complex condition to manage, especially since many patients have comorbidities like anemia or active cancer, complicating treatment. “It’s a very dynamic and fluid condition, and we can’t take for granted that rtPA is a standard of care,” Dr. Rali said.

Alternative treatments such as catheter-directed therapies, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and surgical embolectomy are emerging as promising options, especially for patients who do not respond to or cannot receive rtPA. Mechanical treatments offer benefits in reducing clot burden and stabilizing patients, but they come with their own challenges.

ECMO can stabilize patients who are in shock or cardiac arrest, buying time for the clot to resolve or for further interventions like surgery or catheter-based treatments, said Dr. Rali. However, it is an invasive procedure requiring cannulation of large blood vessels, often involving significant resources and expertise.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis is a minimally invasive technique where a catheter is inserted directly into the pulmonary artery to deliver thrombolytic drugs at lower doses. This method allows for more targeted treatment of the clot, reducing the risk for systemic bleeding that comes with higher doses of thrombolytic agents used in systemic therapy, Dr. Rali explained.

Dr. Rali reported results from the FLAME study, which investigated the effectiveness of FlowTriever mechanical thrombectomy compared with conventional therapies for high-risk PE. This prospective, multicenter observational study enrolled 53 patients in the FlowTriever arm and 61 in the context arm, which included patients treated with systemic thrombolysis or anticoagulation. The primary endpoint, a composite of adverse in-hospital outcomes, was reached in 17% of FlowTriever patients, significantly lower than the 32% performance goal and the 63.9% rate in the context arm. In-hospital mortality was dramatically lower in the FlowTriever arm (1.9%) compared to the context arm (29.5%).

When catheter-based treatment fails, surgical pulmonary embolectomy is a last-resort option. “Only a minority of the high-risk PE [patients] would qualify for rtPA without harmful side effects,” Dr. Rali concluded. “So think wise before you pull your trigger.”

rtPA Not a Matter of the Past

In high-risk PE, the therapeutic priority is rapid hemodynamic stabilization and restoration of pulmonary blood flow to prevent cardiovascular collapse. Systemic thrombolysis acts quickly, reducing pulmonary vascular resistance and obstruction within hours, said Dr. Sanchez.

Presenting at the ERS Congress, he reported numerous studies, including 15 randomized controlled trials that demonstrated its effectiveness in high-risk PE. The PEITHO trial, in particular, demonstrated the ability of systemic thrombolysis to reduce all-cause mortality and hemodynamic collapse within 7 days.

However, this benefit comes at the cost of increased bleeding risk, including a 10% rate of major bleeding and a 2% risk for intracranial hemorrhage. “These data come from old studies using invasive diagnostic procedures, and with current diagnostic procedures, the rate of bleeding is probably lower,” Dr. Sanchez said. The risk of bleeding is also related to the type of thrombolytic agent, with tenecteplase being strongly associated with a higher risk of bleeding, while alteplase shows no increase in the risk of major bleeding, he added. New strategies like reduced-dose thrombolysis offer comparable efficacy and improved safety, as demonstrated in ongoing trials like PEITHO-3, which aim to optimize the balance between efficacy and bleeding risk. Dr. Sanchez is the lead investigator of the PEITHO-3 study.

While rtPA might not be optimal for all patients, Dr. Sanchez thinks there is not enough evidence to replace it as a first-line treatment.

Existing studies on catheter-directed therapies often focus on surrogate endpoints, such as right-to-left ventricular ratio changes, rather than clinical outcomes like mortality, he said. Retrospective data suggest that catheter-directed therapies may reduce in-hospital mortality compared with systemic therapies, but they also increase the risk of intracranial bleeding, post-procedure complications, and device-related events.

Sanchez mentioned the same FLAME study described by Dr. Rali, which reported a 23% rate of device-related complications and 11% major bleeding in patients treated with catheter-directed therapies.

“Systemic thrombolysis remains the first treatment of choice,” Dr. Sanchez concluded. “The use of catheter-directed treatment should be discussed as an alternative in case of contraindications.”

The Debate Continues

Numerous ongoing clinical studies, such as the FLARE trial, will address gaps in evidence and refine treatment protocols, potentially reshaping the standard of care in high-risk PE in the near future by providing new data on the efficacy and safety of existing and emerging therapies.

“The coming data will make it clearer what the best option is,” said Thamer Al Khouzaie, MD, a pulmonary medicine consultant at Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. For now, he said, systemic thrombolysis remains the best option for most patients because it is widely available, easily administered with intravenous infusion, and at a limited cost. Catheter-directed treatment and surgical options are only available in specialized centers, require expertise and training, and are also very expensive.

Dr. Rali, Dr. Sanchez, and Dr. Khouzaie report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The language of AI and its applications in health care

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

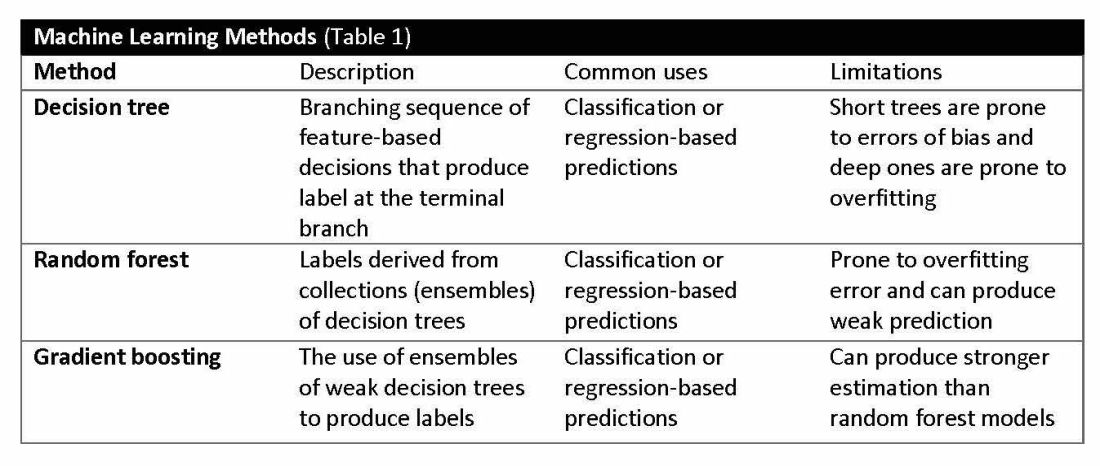

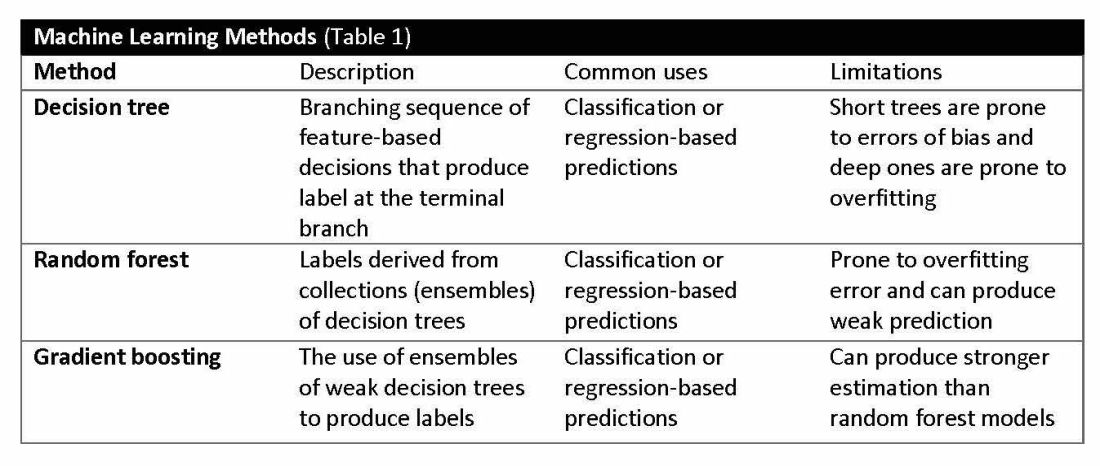

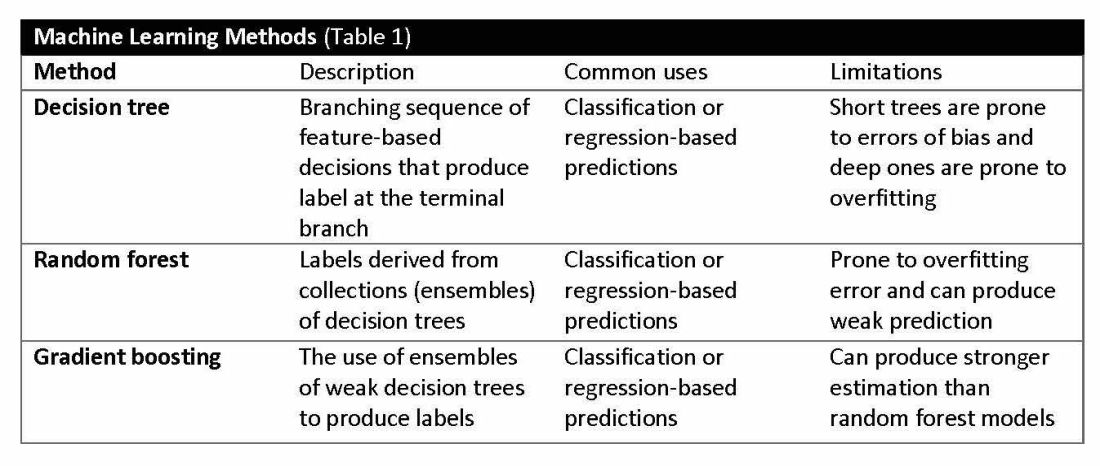

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

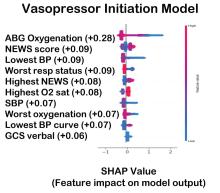

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

The Most Misinterpreted Study in Medicine: Don’t be TRICCed

Ah, blood. That sweet nectar of life that quiets angina, abolishes dyspnea, prevents orthostatic syncope, and quells sinus tachycardia. As a cardiologist, I am an unabashed hemophile.

But we liberal transfusionists are challenged on every request for consideration of transfusion. Whereas the polite may resort to whispered skepticism, vehement critics respond with scorn as if we’d asked them to burn aromatic herbs or fetch a bucket of leeches. And to what do we owe this pathological angst? The broad and persistent misinterpretation of the pesky TRICC trial (N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417). You know; the one that should have been published with a boxed warning stating: “Misinterpretation of this trial could result in significant harm.”

Point 1: Our Actively Bleeding Patient is Not a TRICC Patient.

They were randomly assigned to either a conservative trigger for transfusion of < 7 g/dL or a liberal threshold of < 10 g/dL. Mortality at 30 days was lower with the conservative approach — 18.7% vs 23.3% — but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .11). The findings were similar for the secondary endpoints of inpatient mortality (22.2% vs 28.1%; P = .05) and ICU mortality (13.9% vs 16.2%; P = .29).

One must admit that these P values are not impressive, and the authors’ conclusion should have warranted caution: “A restrictive strategy ... is at least as effective as and possibly superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill patients, with the possible exception of patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina.”

Point 2: Our Critically Ill Cardiac Patient is Unlikely to be a “TRICC” Patient.

Another criticism of TRICC is that only 13% of those assessed and 26% of those eligible were enrolled, mostly owing to physician refusal. Only 26% of enrolled patients had cardiac disease. This makes the TRICC population highly selected and not representative of typical ICU patients.

To prove my point that the edict against higher transfusion thresholds can be dangerous, I’ll describe my most recent interface with TRICC trial misinterpretation

A Case in Point

The patient, Mrs. Kemp,* is 79 years old and has been on aspirin for years following coronary stent placement. One evening, she began spurting bright red blood from her rectum, interrupted only briefly by large clots the consistency of jellied cranberries. When she arrived at the hospital, she was hemodynamically stable, with a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL, down from her usual 12 g/dL. That level bolstered the confidence of her provider, who insisted that she be managed conservatively.

Mrs. Kemp was transferred to the ward, where she continued to bleed briskly. Over the next 2 hours, her hemoglobin level dropped to 9 g/dL, then 8 g/dL. Her daughter, a healthcare worker, requested a transfusion. The answer was, wait for it — the well-scripted, somewhat patronizing oft-quoted line, “The medical literature states that we need to wait for a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL before we transfuse.”

Later that evening, Mrs. Kemp’s systolic blood pressure dropped to the upper 80s, despite her usual hypertension. The provider was again comforted by the fact that she was not tachycardic (she had a pacemaker and was on bisoprolol). The next morning, Mrs. Kemp felt the need to defecate and was placed on the bedside commode and left to her privacy. Predictably, she became dizzy and experienced frank syncope. Thankfully, she avoided a hip fracture or worse. A stat hemoglobin returned at 6 g/dL.

Her daughter said she literally heard the hallelujah chorus because her mother’s hemoglobin was finally below that much revered and often misleading threshold of 7 g/dL. Finally, there was an order for platelets and packed red cells. Five units later, Mr. Kemp achieved a hemoglobin of 8 g/dL and survived. Two more units and she was soaring at 9 g/dL!

Lessons for Transfusion Conservatives

There are many lessons here.

The TRICC study found that hemodynamically stable, asymptomatic patients who are not actively bleeding may well tolerate a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL. But a patient with bright red blood actively pouring from an orifice and a rapidly declining hemoglobin level isn’t one of those people. Additionally, a patient who faints from hypovolemia is not one of those people.

Patients with a history of bleeding presenting with new resting sinus tachycardia (in those who have chronotropic competence) should be presumed to be actively bleeding, and the findings of TRICC do not apply to them. Patients who have bled buckets on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies and have dropped their hemoglobin will probably continue to ooze and should be subject to a low threshold for transfusion.

Additionally, anemic people who are hemodynamically stable but can’t walk without new significant shortness of air or new rest angina need blood, and sometimes at hemoglobin levels higher than generally accepted by conservative strategists. Finally, failing to treat or at least monitor patients who are spontaneously bleeding as aggressively as some trauma patients is a failure to provide proper medical care.

The vast majority of my healthcare clinician colleagues are competent, compassionate individuals who can reasonably discuss the nuances of any medical scenario. One important distinction of a good medical team is the willingness to change course based on a change in patient status or the presentation of what may be new information for the provider.

But those proud transfusion conservatives who will not budge until their threshold is met need to make certain their patient is truly subject to their supposed edicts. Our blood banks should not be more difficult to access than Fort Knox, and transfusion should be used appropriately and liberally in the hemodynamically unstable, the symptomatic, and active brisk bleeders.

I beg staunch transfusion conservatives to consider how they might feel if someone stuck a magic spigot in their brachial artery and acutely drained their hemoglobin to that magic threshold of 7 g/dL. When syncope, shortness of air, fatigue, and angina find them, they may generate empathy for those who need transfusion. Might that do the TRICC?

*Some details have been changed to conceal the identity of the patient, but the essence of the case has been preserved.

Dr. Walton-Shirley, a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology and now does locums work in Montana, is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Ah, blood. That sweet nectar of life that quiets angina, abolishes dyspnea, prevents orthostatic syncope, and quells sinus tachycardia. As a cardiologist, I am an unabashed hemophile.

But we liberal transfusionists are challenged on every request for consideration of transfusion. Whereas the polite may resort to whispered skepticism, vehement critics respond with scorn as if we’d asked them to burn aromatic herbs or fetch a bucket of leeches. And to what do we owe this pathological angst? The broad and persistent misinterpretation of the pesky TRICC trial (N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417). You know; the one that should have been published with a boxed warning stating: “Misinterpretation of this trial could result in significant harm.”

Point 1: Our Actively Bleeding Patient is Not a TRICC Patient.

They were randomly assigned to either a conservative trigger for transfusion of < 7 g/dL or a liberal threshold of < 10 g/dL. Mortality at 30 days was lower with the conservative approach — 18.7% vs 23.3% — but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .11). The findings were similar for the secondary endpoints of inpatient mortality (22.2% vs 28.1%; P = .05) and ICU mortality (13.9% vs 16.2%; P = .29).

One must admit that these P values are not impressive, and the authors’ conclusion should have warranted caution: “A restrictive strategy ... is at least as effective as and possibly superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill patients, with the possible exception of patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina.”

Point 2: Our Critically Ill Cardiac Patient is Unlikely to be a “TRICC” Patient.

Another criticism of TRICC is that only 13% of those assessed and 26% of those eligible were enrolled, mostly owing to physician refusal. Only 26% of enrolled patients had cardiac disease. This makes the TRICC population highly selected and not representative of typical ICU patients.

To prove my point that the edict against higher transfusion thresholds can be dangerous, I’ll describe my most recent interface with TRICC trial misinterpretation

A Case in Point

The patient, Mrs. Kemp,* is 79 years old and has been on aspirin for years following coronary stent placement. One evening, she began spurting bright red blood from her rectum, interrupted only briefly by large clots the consistency of jellied cranberries. When she arrived at the hospital, she was hemodynamically stable, with a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL, down from her usual 12 g/dL. That level bolstered the confidence of her provider, who insisted that she be managed conservatively.

Mrs. Kemp was transferred to the ward, where she continued to bleed briskly. Over the next 2 hours, her hemoglobin level dropped to 9 g/dL, then 8 g/dL. Her daughter, a healthcare worker, requested a transfusion. The answer was, wait for it — the well-scripted, somewhat patronizing oft-quoted line, “The medical literature states that we need to wait for a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL before we transfuse.”

Later that evening, Mrs. Kemp’s systolic blood pressure dropped to the upper 80s, despite her usual hypertension. The provider was again comforted by the fact that she was not tachycardic (she had a pacemaker and was on bisoprolol). The next morning, Mrs. Kemp felt the need to defecate and was placed on the bedside commode and left to her privacy. Predictably, she became dizzy and experienced frank syncope. Thankfully, she avoided a hip fracture or worse. A stat hemoglobin returned at 6 g/dL.

Her daughter said she literally heard the hallelujah chorus because her mother’s hemoglobin was finally below that much revered and often misleading threshold of 7 g/dL. Finally, there was an order for platelets and packed red cells. Five units later, Mr. Kemp achieved a hemoglobin of 8 g/dL and survived. Two more units and she was soaring at 9 g/dL!

Lessons for Transfusion Conservatives

There are many lessons here.

The TRICC study found that hemodynamically stable, asymptomatic patients who are not actively bleeding may well tolerate a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL. But a patient with bright red blood actively pouring from an orifice and a rapidly declining hemoglobin level isn’t one of those people. Additionally, a patient who faints from hypovolemia is not one of those people.

Patients with a history of bleeding presenting with new resting sinus tachycardia (in those who have chronotropic competence) should be presumed to be actively bleeding, and the findings of TRICC do not apply to them. Patients who have bled buckets on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies and have dropped their hemoglobin will probably continue to ooze and should be subject to a low threshold for transfusion.

Additionally, anemic people who are hemodynamically stable but can’t walk without new significant shortness of air or new rest angina need blood, and sometimes at hemoglobin levels higher than generally accepted by conservative strategists. Finally, failing to treat or at least monitor patients who are spontaneously bleeding as aggressively as some trauma patients is a failure to provide proper medical care.

The vast majority of my healthcare clinician colleagues are competent, compassionate individuals who can reasonably discuss the nuances of any medical scenario. One important distinction of a good medical team is the willingness to change course based on a change in patient status or the presentation of what may be new information for the provider.

But those proud transfusion conservatives who will not budge until their threshold is met need to make certain their patient is truly subject to their supposed edicts. Our blood banks should not be more difficult to access than Fort Knox, and transfusion should be used appropriately and liberally in the hemodynamically unstable, the symptomatic, and active brisk bleeders.

I beg staunch transfusion conservatives to consider how they might feel if someone stuck a magic spigot in their brachial artery and acutely drained their hemoglobin to that magic threshold of 7 g/dL. When syncope, shortness of air, fatigue, and angina find them, they may generate empathy for those who need transfusion. Might that do the TRICC?

*Some details have been changed to conceal the identity of the patient, but the essence of the case has been preserved.

Dr. Walton-Shirley, a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology and now does locums work in Montana, is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Ah, blood. That sweet nectar of life that quiets angina, abolishes dyspnea, prevents orthostatic syncope, and quells sinus tachycardia. As a cardiologist, I am an unabashed hemophile.

But we liberal transfusionists are challenged on every request for consideration of transfusion. Whereas the polite may resort to whispered skepticism, vehement critics respond with scorn as if we’d asked them to burn aromatic herbs or fetch a bucket of leeches. And to what do we owe this pathological angst? The broad and persistent misinterpretation of the pesky TRICC trial (N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417). You know; the one that should have been published with a boxed warning stating: “Misinterpretation of this trial could result in significant harm.”

Point 1: Our Actively Bleeding Patient is Not a TRICC Patient.

They were randomly assigned to either a conservative trigger for transfusion of < 7 g/dL or a liberal threshold of < 10 g/dL. Mortality at 30 days was lower with the conservative approach — 18.7% vs 23.3% — but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .11). The findings were similar for the secondary endpoints of inpatient mortality (22.2% vs 28.1%; P = .05) and ICU mortality (13.9% vs 16.2%; P = .29).

One must admit that these P values are not impressive, and the authors’ conclusion should have warranted caution: “A restrictive strategy ... is at least as effective as and possibly superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill patients, with the possible exception of patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina.”

Point 2: Our Critically Ill Cardiac Patient is Unlikely to be a “TRICC” Patient.

Another criticism of TRICC is that only 13% of those assessed and 26% of those eligible were enrolled, mostly owing to physician refusal. Only 26% of enrolled patients had cardiac disease. This makes the TRICC population highly selected and not representative of typical ICU patients.

To prove my point that the edict against higher transfusion thresholds can be dangerous, I’ll describe my most recent interface with TRICC trial misinterpretation

A Case in Point

The patient, Mrs. Kemp,* is 79 years old and has been on aspirin for years following coronary stent placement. One evening, she began spurting bright red blood from her rectum, interrupted only briefly by large clots the consistency of jellied cranberries. When she arrived at the hospital, she was hemodynamically stable, with a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL, down from her usual 12 g/dL. That level bolstered the confidence of her provider, who insisted that she be managed conservatively.

Mrs. Kemp was transferred to the ward, where she continued to bleed briskly. Over the next 2 hours, her hemoglobin level dropped to 9 g/dL, then 8 g/dL. Her daughter, a healthcare worker, requested a transfusion. The answer was, wait for it — the well-scripted, somewhat patronizing oft-quoted line, “The medical literature states that we need to wait for a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL before we transfuse.”

Later that evening, Mrs. Kemp’s systolic blood pressure dropped to the upper 80s, despite her usual hypertension. The provider was again comforted by the fact that she was not tachycardic (she had a pacemaker and was on bisoprolol). The next morning, Mrs. Kemp felt the need to defecate and was placed on the bedside commode and left to her privacy. Predictably, she became dizzy and experienced frank syncope. Thankfully, she avoided a hip fracture or worse. A stat hemoglobin returned at 6 g/dL.

Her daughter said she literally heard the hallelujah chorus because her mother’s hemoglobin was finally below that much revered and often misleading threshold of 7 g/dL. Finally, there was an order for platelets and packed red cells. Five units later, Mr. Kemp achieved a hemoglobin of 8 g/dL and survived. Two more units and she was soaring at 9 g/dL!

Lessons for Transfusion Conservatives

There are many lessons here.

The TRICC study found that hemodynamically stable, asymptomatic patients who are not actively bleeding may well tolerate a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL. But a patient with bright red blood actively pouring from an orifice and a rapidly declining hemoglobin level isn’t one of those people. Additionally, a patient who faints from hypovolemia is not one of those people.

Patients with a history of bleeding presenting with new resting sinus tachycardia (in those who have chronotropic competence) should be presumed to be actively bleeding, and the findings of TRICC do not apply to them. Patients who have bled buckets on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies and have dropped their hemoglobin will probably continue to ooze and should be subject to a low threshold for transfusion.

Additionally, anemic people who are hemodynamically stable but can’t walk without new significant shortness of air or new rest angina need blood, and sometimes at hemoglobin levels higher than generally accepted by conservative strategists. Finally, failing to treat or at least monitor patients who are spontaneously bleeding as aggressively as some trauma patients is a failure to provide proper medical care.

The vast majority of my healthcare clinician colleagues are competent, compassionate individuals who can reasonably discuss the nuances of any medical scenario. One important distinction of a good medical team is the willingness to change course based on a change in patient status or the presentation of what may be new information for the provider.

But those proud transfusion conservatives who will not budge until their threshold is met need to make certain their patient is truly subject to their supposed edicts. Our blood banks should not be more difficult to access than Fort Knox, and transfusion should be used appropriately and liberally in the hemodynamically unstable, the symptomatic, and active brisk bleeders.

I beg staunch transfusion conservatives to consider how they might feel if someone stuck a magic spigot in their brachial artery and acutely drained their hemoglobin to that magic threshold of 7 g/dL. When syncope, shortness of air, fatigue, and angina find them, they may generate empathy for those who need transfusion. Might that do the TRICC?

*Some details have been changed to conceal the identity of the patient, but the essence of the case has been preserved.

Dr. Walton-Shirley, a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology and now does locums work in Montana, is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

What Every Provider Should Know About Type 1 Diabetes