User login

PCOS comes with high morbidity, medication use into late 40s

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have an increased risk for several diseases and symptoms, many independent of body mass index (BMI), new research indicates.

Some diseases are linked for the first time to PCOS in this study, the authors wrote.

Researchers, led by Linda Kujanpää, MD, of the research unit for pediatrics, dermatology, clinical genetics, obstetrics, and gynecology at University of Oulu (Finland), found the morbidity risk is evident through the late reproductive years.

The paper was published online in Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

This population-based follow-up study investigated comorbidities and medication and health care services use among women with PCOS in Finland at age 46 years via answers to a questionnaire.

The whole PCOS population (n = 280) consisted of women who reported both hirsutism and oligo/amenorrhea at age 31 (4.1%) and/or polycystic ovary morphology/PCOS at age 46 (3.1%), of which 246 replied to the 46-year questionnaire. They were compared with a control group of 1,573 women without PCOS.

Overall morbidity risk was 35% higher than for women without PCOS (risk ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.57). Medication use was 27% higher (RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.08-1.50), and the risk remained after adjusting for BMI.

Diagnoses with increased prevalence in women with PCOS were osteoarthritis, migraine, hypertension, tendinitis, and endometriosis. PCOS was also associated with autoimmune diseases and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections.

“BMI seems not to be solely responsible for the increased morbidity,” the researchers found. The average morbidity score of women with PCOS with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher was similar to that of women with PCOS and lower BMI.

Mindy Christianson, MD, medical director at Johns Hopkins Fertility Center and associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, said in an interview that the links to diseases independent of BMI are interesting because there’s so much focus on counseling women with PCOS to lose weight.

While that message is still important, it’s important to realize that some related diseases and conditions – such as autoimmune diseases and migraine – are not driven by BMI.

“It really drives home the point that polycystic ovary syndrome is really a chronic medical condition and puts patients at risk for a number of health conditions,” she said. “Having a good primary care physician is important to help them with their overall health.”

Women with PCOS said their health was poor or very poor almost three times more often than did women in the control group.

Surprisingly few studies have looked at overall comorbidity in women with PCOS, the authors wrote.

“This should be of high priority given the high cost to society resulting from PCOS-related morbidity,” they added. As an example, they pointed out that PCOS-related type 2 diabetes alone costs an estimated $1.77 billion in the United States and £237 million ($310 million) each year in the United Kingdom.

Additionally, the focus in previous research has typically been on women in their early or mid-reproductive years, and morbidity burden data in late reproductive years are scarce.

The study population was pulled from the longitudinal Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 and included all pregnancies with estimated date of delivery during 1966 in two provinces of Finland (5,889 women).

Dr. Christianson said she hopes this study will spur more research on PCOS, which has been severely underfunded, especially in the United States.

Part of the reason for that is there is a limited number of subspecialists in the country who work with patients with PCOS and do research in the area. PCOS often gets lost in the research priorities of infertility, diabetes, and thyroid disease.

The message in this study that PCOS is not just a fertility issue or an obesity issue but an overall health issue with a substantial cost to the health system may help raise awareness, Dr. Christianson said.

This study was supported by grants from The Finnish Medical Foundation, The Academy of Finland, The Sigrid Juselius Foundation, The Finnish Cultural Foundation, The Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas Foundation, The Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, Genesis Research Trust, The Medical Research Council, University of Oulu, Oulu University Hospital, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Regional Institute of Occupational Health, and the European Regional Development Fund. The Study authors and Dr. Christianson reported no relevant financial relationships.

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have an increased risk for several diseases and symptoms, many independent of body mass index (BMI), new research indicates.

Some diseases are linked for the first time to PCOS in this study, the authors wrote.

Researchers, led by Linda Kujanpää, MD, of the research unit for pediatrics, dermatology, clinical genetics, obstetrics, and gynecology at University of Oulu (Finland), found the morbidity risk is evident through the late reproductive years.

The paper was published online in Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

This population-based follow-up study investigated comorbidities and medication and health care services use among women with PCOS in Finland at age 46 years via answers to a questionnaire.

The whole PCOS population (n = 280) consisted of women who reported both hirsutism and oligo/amenorrhea at age 31 (4.1%) and/or polycystic ovary morphology/PCOS at age 46 (3.1%), of which 246 replied to the 46-year questionnaire. They were compared with a control group of 1,573 women without PCOS.

Overall morbidity risk was 35% higher than for women without PCOS (risk ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.57). Medication use was 27% higher (RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.08-1.50), and the risk remained after adjusting for BMI.

Diagnoses with increased prevalence in women with PCOS were osteoarthritis, migraine, hypertension, tendinitis, and endometriosis. PCOS was also associated with autoimmune diseases and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections.

“BMI seems not to be solely responsible for the increased morbidity,” the researchers found. The average morbidity score of women with PCOS with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher was similar to that of women with PCOS and lower BMI.

Mindy Christianson, MD, medical director at Johns Hopkins Fertility Center and associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, said in an interview that the links to diseases independent of BMI are interesting because there’s so much focus on counseling women with PCOS to lose weight.

While that message is still important, it’s important to realize that some related diseases and conditions – such as autoimmune diseases and migraine – are not driven by BMI.

“It really drives home the point that polycystic ovary syndrome is really a chronic medical condition and puts patients at risk for a number of health conditions,” she said. “Having a good primary care physician is important to help them with their overall health.”

Women with PCOS said their health was poor or very poor almost three times more often than did women in the control group.

Surprisingly few studies have looked at overall comorbidity in women with PCOS, the authors wrote.

“This should be of high priority given the high cost to society resulting from PCOS-related morbidity,” they added. As an example, they pointed out that PCOS-related type 2 diabetes alone costs an estimated $1.77 billion in the United States and £237 million ($310 million) each year in the United Kingdom.

Additionally, the focus in previous research has typically been on women in their early or mid-reproductive years, and morbidity burden data in late reproductive years are scarce.

The study population was pulled from the longitudinal Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 and included all pregnancies with estimated date of delivery during 1966 in two provinces of Finland (5,889 women).

Dr. Christianson said she hopes this study will spur more research on PCOS, which has been severely underfunded, especially in the United States.

Part of the reason for that is there is a limited number of subspecialists in the country who work with patients with PCOS and do research in the area. PCOS often gets lost in the research priorities of infertility, diabetes, and thyroid disease.

The message in this study that PCOS is not just a fertility issue or an obesity issue but an overall health issue with a substantial cost to the health system may help raise awareness, Dr. Christianson said.

This study was supported by grants from The Finnish Medical Foundation, The Academy of Finland, The Sigrid Juselius Foundation, The Finnish Cultural Foundation, The Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas Foundation, The Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, Genesis Research Trust, The Medical Research Council, University of Oulu, Oulu University Hospital, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Regional Institute of Occupational Health, and the European Regional Development Fund. The Study authors and Dr. Christianson reported no relevant financial relationships.

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have an increased risk for several diseases and symptoms, many independent of body mass index (BMI), new research indicates.

Some diseases are linked for the first time to PCOS in this study, the authors wrote.

Researchers, led by Linda Kujanpää, MD, of the research unit for pediatrics, dermatology, clinical genetics, obstetrics, and gynecology at University of Oulu (Finland), found the morbidity risk is evident through the late reproductive years.

The paper was published online in Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

This population-based follow-up study investigated comorbidities and medication and health care services use among women with PCOS in Finland at age 46 years via answers to a questionnaire.

The whole PCOS population (n = 280) consisted of women who reported both hirsutism and oligo/amenorrhea at age 31 (4.1%) and/or polycystic ovary morphology/PCOS at age 46 (3.1%), of which 246 replied to the 46-year questionnaire. They were compared with a control group of 1,573 women without PCOS.

Overall morbidity risk was 35% higher than for women without PCOS (risk ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.57). Medication use was 27% higher (RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.08-1.50), and the risk remained after adjusting for BMI.

Diagnoses with increased prevalence in women with PCOS were osteoarthritis, migraine, hypertension, tendinitis, and endometriosis. PCOS was also associated with autoimmune diseases and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections.

“BMI seems not to be solely responsible for the increased morbidity,” the researchers found. The average morbidity score of women with PCOS with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher was similar to that of women with PCOS and lower BMI.

Mindy Christianson, MD, medical director at Johns Hopkins Fertility Center and associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, said in an interview that the links to diseases independent of BMI are interesting because there’s so much focus on counseling women with PCOS to lose weight.

While that message is still important, it’s important to realize that some related diseases and conditions – such as autoimmune diseases and migraine – are not driven by BMI.

“It really drives home the point that polycystic ovary syndrome is really a chronic medical condition and puts patients at risk for a number of health conditions,” she said. “Having a good primary care physician is important to help them with their overall health.”

Women with PCOS said their health was poor or very poor almost three times more often than did women in the control group.

Surprisingly few studies have looked at overall comorbidity in women with PCOS, the authors wrote.

“This should be of high priority given the high cost to society resulting from PCOS-related morbidity,” they added. As an example, they pointed out that PCOS-related type 2 diabetes alone costs an estimated $1.77 billion in the United States and £237 million ($310 million) each year in the United Kingdom.

Additionally, the focus in previous research has typically been on women in their early or mid-reproductive years, and morbidity burden data in late reproductive years are scarce.

The study population was pulled from the longitudinal Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 and included all pregnancies with estimated date of delivery during 1966 in two provinces of Finland (5,889 women).

Dr. Christianson said she hopes this study will spur more research on PCOS, which has been severely underfunded, especially in the United States.

Part of the reason for that is there is a limited number of subspecialists in the country who work with patients with PCOS and do research in the area. PCOS often gets lost in the research priorities of infertility, diabetes, and thyroid disease.

The message in this study that PCOS is not just a fertility issue or an obesity issue but an overall health issue with a substantial cost to the health system may help raise awareness, Dr. Christianson said.

This study was supported by grants from The Finnish Medical Foundation, The Academy of Finland, The Sigrid Juselius Foundation, The Finnish Cultural Foundation, The Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas Foundation, The Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, Genesis Research Trust, The Medical Research Council, University of Oulu, Oulu University Hospital, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Regional Institute of Occupational Health, and the European Regional Development Fund. The Study authors and Dr. Christianson reported no relevant financial relationships.

FROM ACTA OBSTETRICIA ET GYNECOLOGICA SCANDINAVICA

Endometriosis: Diagnosis, Surgical Management, and Overlapping Diagnosis.

As a gynecologist specializing in minimally invasive surgical techniques, what is your involvement in the process for diagnosing endometriosis?

Dr. Lager: At our multidisciplinary endometriosis center, we receive a range of referrals from excellent providers near San Francisco and beyond. As a result, patients will often have had extensive evaluations and multiple treatments. Nonetheless, it is important to take a thorough history, to gain an understanding of the progress of their disease, treatments they have taken and the results or side effects of those treatments, and the goals of the patient in order to guide next steps.

Reviewing previous operative reports, pathology, and surgical photos can also be helpful to guide next steps. Commonly, patients will present with dysmenorrhea, and depending on the severity of associated symptoms, such as dysuria, dyschezia, hematuria, or hematochezia, I may refer patients to our colleagues in urology or GI for further evaluation.

Patients will often have previous imaging such as an ultrasound or CT to evaluate anatomic etiology of the pain, but those studies are often negative. Depending on their history, I may order additional imaging, such as an MRI pelvis, and consideration of vaginal or rectal gel. We have worked closely with our radiologists who have developed a specific endometriosis protocol for deeply infiltrative endometriosis and have a multidisciplinary review committee to discuss complex cases.

Although the gold standard for diagnosis of endometriosis is surgical, this leads to a delay in treatment of 7 to 12 years.[1] So, if a patient presents with symptoms of endometriosis, I will discuss the likely diagnosis and start treatment.

Are there specific techniques that you prefer in your standard practice once a clear diagnosis is determined?

Dr. Lager: As I mentioned, although endometriosis is a surgical diagnosis, there may be findings on imaging which will lead to a diagnosis of endometriosis, including endometriomas, uterosacral thickening, a “kissing ovary” appearance, or hematosalpinx for example.

I discuss a broad range of treatment options based on the patient’s goals, from least invasive treatments to definitive surgery. I discuss dietary changes, integrative medicine (we are fortunate to have an integrative medicine gynecologist here at UCSF Osher Center), and pain psychology. Additionally, I review first-line hormonal management options such as: birth control pills, progestin-only pills, levenogestrol IUD, etonogestrel implant, and medroxyprogesterone acetate injection. In my practice, most patients have already tried initial treatment options, and are most interested in other options. I then review second-line options such as GnRH agonists, antagonists, danazol, and aromatase inhibitors. For patients that have had chronic pelvic pain, I also discuss peripheral and central sensitization, and overlapping diagnoses. Surgical management includes diagnostic laparoscopy and excision or ablation of endometriosis, hysterectomy, and oophorectomy.

Are there specific factors that you look for to help you decide whether surgical management is necessary?

Dr. Lager: There are several reasons why patients decide to proceed with surgical management. First, some patients are reticent to start treatment, particularly if they have had negative experiences with hormonal medications and desire a definitive diagnosis. Other patients choose to proceed with surgery for fertility reasons, and others have severe symptoms that are not managed by medications.

The goal of surgery is to remove all visible endometriotic lesions, restore normal anatomy and for pathologic diagnosis if there is atypical characteristics of an endometrial mass. The pelvic exam and imaging can often be helpful surgical planning. If there is a deeply infiltrative lesion in the bowel or bladder, I consult my urology and colorectal colleagues for surgical planning.

Endometriotic lesions are heterogenous, and can include superficial peritoneal lesions, clear vesicular lesions, “powder burn lesions”, endometriomas, and deep infiltrative lesions.

Additionally, I counsel patients on surgical options depending on the fertility desires. For patients with infertility and symptoms of endometriosis, primary surgery with excision or ablation increases pregnancy rates. One meta-analysis showed that operative laparoscopy improved live births and ongoing pregnancy rates.[2] This was found for the first laparoscopic surgery and not repeat surgery.

Can you talk a little bit more about some of the advancements and the controversies in surgical management, and how that impacts your practice or your treatment?

Dr. Lager: Controversy in surgical management includes excision versus ablation in surgical management of endometriosis. One randomized controlled trial showed an improvement with dyspareunia with excision versus ablation after 5 year follow up.[3] However, a recent meta-analysis from 2021 showed no difference in dysmenorrhea between excision and ablation.[4] I generally perform excision of endometriosis as it can provide a tissue for diagnosis and may allow for complete excision of a lesion that may have an underlying component not easily seen.

We also discussed some of the controversy related to fertility and endometriosis. Management of endometriomas in the face of desired fertility is unclear. Endometriomas that are >3 cm in diameter are associated with decreased anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels, but ovarian cystectomy for endometriomas is also associated with decreased AMH levels. I will counsel patients regarding the risks and benefits of ovarian cystectomy and discuss with the reproductive endocrinologists if they recommend removal to improve oocyte retrieval.

Lastly, conservative versus definitive treatment is an important issue to discuss. Depending on a patient’s goals, conservative surgical management of endometriosis may be the most appropriate procedure. However, if a patient has multiple surgeries, does not desire to have children or has completed childbearing regardless of age and wants to decrease the risk of need for repeat surgery, I will discuss with patients that the risk of reoperation after hysterectomy versus conservative surgery is 8% vs 21% in 2 years and 59% vs 22% after 7 years, respectively.[5] Additionally, the patient may have an overlapping gynecological condition, such as adenomyosis or fibroids, and desire surgical management for those conditions as well. Management ultimately will depend on shared decision making,

You mentioned overlapping diagnosis. What are the impacts and barriers related to misdiagnosis or overlapping diagnosis, and what is your approach to recognizing those signs and symptoms?

Dr. Lager: The classic symptoms of endometriosis can overlap with several medical conditions. In addition to gynecologic issues such as adenomyosis and fibroids that I mentioned previously, symptoms such as pelvic pain, bloating, and dysuria can be associated with gastrointestinal conditions, painful bladder syndrome, neurologic, and musculoskeletal pain conditions. This is complex because the overlapping diagnoses can lead to misdiagnosis, and delay in diagnosis and missing an associated diagnosis can lead to inadequate treatment.

I approach the possibility of overlapping diagnoses in consultation with my colleagues who may recommend further testing, such as endoscopy and colonoscopy. Depending on the diagnoses, several treatments can be started concomitantly to address the multifactorial components of pain. For example, pelvic floor dysfunction related to pelvic pain can affect bowel habits, even without a diagnosis of IBS. Pelvic floor physical therapy can address one component of this. Similarly, even if we surgically or medically manage symptoms of endometriosis, the musculoskeletal pain can lead to persistent or worsening pain. The same goes for pain medicine and peripheral or central pain sensitization or neurological pain.

Was there anything else you’d like to share with your colleagues?

Dr. Lager: Endometriosis is a complex condition that requires a multifactorial approach that takes into consideration a patient’s goals. There is not a one-size fit for all patients with endometriosis due to all the issues we discussed. It will take time to address the varied components of pain and is an iterative process. Minimally invasive surgery has an important role in diagnosis and management of endometriosis but is one of several approaches to treat this complex condition. Thanks for taking the time to discuss this important condition that affects at least 10% of gynecological patients, and potentially more due to delayed and undiagnosed disease.

- Staal AH, van der Zanden M, Nap AW. Diagnostic delay of endometriosis in the Netherlands. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2016;81(4):321-4. doi: 10.1159/000441911

- Duffy JM, Arambage K, Correa FJ, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD011031. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;10:CD011031. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011031.pub2

- Healey M, Cheng C, Kaur H. To excise or ablate endometriosis? A prospective randomized double-blinded trial after 5-year follow-up. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(6):999-1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.04.002

- Burks C, Lee M, DeSarno M, Findley J, Flyckt R. Excision versus ablation for management of minimal to mild endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):587-597. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2020.11.028

- Shakiba K, Bena JF, McGill KM, Minger J, Falcone T. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: a 7-year follow-up on the requirement for further surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1285-92. Erratum in: Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(3):710. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181758ec6

As a gynecologist specializing in minimally invasive surgical techniques, what is your involvement in the process for diagnosing endometriosis?

Dr. Lager: At our multidisciplinary endometriosis center, we receive a range of referrals from excellent providers near San Francisco and beyond. As a result, patients will often have had extensive evaluations and multiple treatments. Nonetheless, it is important to take a thorough history, to gain an understanding of the progress of their disease, treatments they have taken and the results or side effects of those treatments, and the goals of the patient in order to guide next steps.

Reviewing previous operative reports, pathology, and surgical photos can also be helpful to guide next steps. Commonly, patients will present with dysmenorrhea, and depending on the severity of associated symptoms, such as dysuria, dyschezia, hematuria, or hematochezia, I may refer patients to our colleagues in urology or GI for further evaluation.

Patients will often have previous imaging such as an ultrasound or CT to evaluate anatomic etiology of the pain, but those studies are often negative. Depending on their history, I may order additional imaging, such as an MRI pelvis, and consideration of vaginal or rectal gel. We have worked closely with our radiologists who have developed a specific endometriosis protocol for deeply infiltrative endometriosis and have a multidisciplinary review committee to discuss complex cases.

Although the gold standard for diagnosis of endometriosis is surgical, this leads to a delay in treatment of 7 to 12 years.[1] So, if a patient presents with symptoms of endometriosis, I will discuss the likely diagnosis and start treatment.

Are there specific techniques that you prefer in your standard practice once a clear diagnosis is determined?

Dr. Lager: As I mentioned, although endometriosis is a surgical diagnosis, there may be findings on imaging which will lead to a diagnosis of endometriosis, including endometriomas, uterosacral thickening, a “kissing ovary” appearance, or hematosalpinx for example.

I discuss a broad range of treatment options based on the patient’s goals, from least invasive treatments to definitive surgery. I discuss dietary changes, integrative medicine (we are fortunate to have an integrative medicine gynecologist here at UCSF Osher Center), and pain psychology. Additionally, I review first-line hormonal management options such as: birth control pills, progestin-only pills, levenogestrol IUD, etonogestrel implant, and medroxyprogesterone acetate injection. In my practice, most patients have already tried initial treatment options, and are most interested in other options. I then review second-line options such as GnRH agonists, antagonists, danazol, and aromatase inhibitors. For patients that have had chronic pelvic pain, I also discuss peripheral and central sensitization, and overlapping diagnoses. Surgical management includes diagnostic laparoscopy and excision or ablation of endometriosis, hysterectomy, and oophorectomy.

Are there specific factors that you look for to help you decide whether surgical management is necessary?

Dr. Lager: There are several reasons why patients decide to proceed with surgical management. First, some patients are reticent to start treatment, particularly if they have had negative experiences with hormonal medications and desire a definitive diagnosis. Other patients choose to proceed with surgery for fertility reasons, and others have severe symptoms that are not managed by medications.

The goal of surgery is to remove all visible endometriotic lesions, restore normal anatomy and for pathologic diagnosis if there is atypical characteristics of an endometrial mass. The pelvic exam and imaging can often be helpful surgical planning. If there is a deeply infiltrative lesion in the bowel or bladder, I consult my urology and colorectal colleagues for surgical planning.

Endometriotic lesions are heterogenous, and can include superficial peritoneal lesions, clear vesicular lesions, “powder burn lesions”, endometriomas, and deep infiltrative lesions.

Additionally, I counsel patients on surgical options depending on the fertility desires. For patients with infertility and symptoms of endometriosis, primary surgery with excision or ablation increases pregnancy rates. One meta-analysis showed that operative laparoscopy improved live births and ongoing pregnancy rates.[2] This was found for the first laparoscopic surgery and not repeat surgery.

Can you talk a little bit more about some of the advancements and the controversies in surgical management, and how that impacts your practice or your treatment?

Dr. Lager: Controversy in surgical management includes excision versus ablation in surgical management of endometriosis. One randomized controlled trial showed an improvement with dyspareunia with excision versus ablation after 5 year follow up.[3] However, a recent meta-analysis from 2021 showed no difference in dysmenorrhea between excision and ablation.[4] I generally perform excision of endometriosis as it can provide a tissue for diagnosis and may allow for complete excision of a lesion that may have an underlying component not easily seen.

We also discussed some of the controversy related to fertility and endometriosis. Management of endometriomas in the face of desired fertility is unclear. Endometriomas that are >3 cm in diameter are associated with decreased anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels, but ovarian cystectomy for endometriomas is also associated with decreased AMH levels. I will counsel patients regarding the risks and benefits of ovarian cystectomy and discuss with the reproductive endocrinologists if they recommend removal to improve oocyte retrieval.

Lastly, conservative versus definitive treatment is an important issue to discuss. Depending on a patient’s goals, conservative surgical management of endometriosis may be the most appropriate procedure. However, if a patient has multiple surgeries, does not desire to have children or has completed childbearing regardless of age and wants to decrease the risk of need for repeat surgery, I will discuss with patients that the risk of reoperation after hysterectomy versus conservative surgery is 8% vs 21% in 2 years and 59% vs 22% after 7 years, respectively.[5] Additionally, the patient may have an overlapping gynecological condition, such as adenomyosis or fibroids, and desire surgical management for those conditions as well. Management ultimately will depend on shared decision making,

You mentioned overlapping diagnosis. What are the impacts and barriers related to misdiagnosis or overlapping diagnosis, and what is your approach to recognizing those signs and symptoms?

Dr. Lager: The classic symptoms of endometriosis can overlap with several medical conditions. In addition to gynecologic issues such as adenomyosis and fibroids that I mentioned previously, symptoms such as pelvic pain, bloating, and dysuria can be associated with gastrointestinal conditions, painful bladder syndrome, neurologic, and musculoskeletal pain conditions. This is complex because the overlapping diagnoses can lead to misdiagnosis, and delay in diagnosis and missing an associated diagnosis can lead to inadequate treatment.

I approach the possibility of overlapping diagnoses in consultation with my colleagues who may recommend further testing, such as endoscopy and colonoscopy. Depending on the diagnoses, several treatments can be started concomitantly to address the multifactorial components of pain. For example, pelvic floor dysfunction related to pelvic pain can affect bowel habits, even without a diagnosis of IBS. Pelvic floor physical therapy can address one component of this. Similarly, even if we surgically or medically manage symptoms of endometriosis, the musculoskeletal pain can lead to persistent or worsening pain. The same goes for pain medicine and peripheral or central pain sensitization or neurological pain.

Was there anything else you’d like to share with your colleagues?

Dr. Lager: Endometriosis is a complex condition that requires a multifactorial approach that takes into consideration a patient’s goals. There is not a one-size fit for all patients with endometriosis due to all the issues we discussed. It will take time to address the varied components of pain and is an iterative process. Minimally invasive surgery has an important role in diagnosis and management of endometriosis but is one of several approaches to treat this complex condition. Thanks for taking the time to discuss this important condition that affects at least 10% of gynecological patients, and potentially more due to delayed and undiagnosed disease.

As a gynecologist specializing in minimally invasive surgical techniques, what is your involvement in the process for diagnosing endometriosis?

Dr. Lager: At our multidisciplinary endometriosis center, we receive a range of referrals from excellent providers near San Francisco and beyond. As a result, patients will often have had extensive evaluations and multiple treatments. Nonetheless, it is important to take a thorough history, to gain an understanding of the progress of their disease, treatments they have taken and the results or side effects of those treatments, and the goals of the patient in order to guide next steps.

Reviewing previous operative reports, pathology, and surgical photos can also be helpful to guide next steps. Commonly, patients will present with dysmenorrhea, and depending on the severity of associated symptoms, such as dysuria, dyschezia, hematuria, or hematochezia, I may refer patients to our colleagues in urology or GI for further evaluation.

Patients will often have previous imaging such as an ultrasound or CT to evaluate anatomic etiology of the pain, but those studies are often negative. Depending on their history, I may order additional imaging, such as an MRI pelvis, and consideration of vaginal or rectal gel. We have worked closely with our radiologists who have developed a specific endometriosis protocol for deeply infiltrative endometriosis and have a multidisciplinary review committee to discuss complex cases.

Although the gold standard for diagnosis of endometriosis is surgical, this leads to a delay in treatment of 7 to 12 years.[1] So, if a patient presents with symptoms of endometriosis, I will discuss the likely diagnosis and start treatment.

Are there specific techniques that you prefer in your standard practice once a clear diagnosis is determined?

Dr. Lager: As I mentioned, although endometriosis is a surgical diagnosis, there may be findings on imaging which will lead to a diagnosis of endometriosis, including endometriomas, uterosacral thickening, a “kissing ovary” appearance, or hematosalpinx for example.

I discuss a broad range of treatment options based on the patient’s goals, from least invasive treatments to definitive surgery. I discuss dietary changes, integrative medicine (we are fortunate to have an integrative medicine gynecologist here at UCSF Osher Center), and pain psychology. Additionally, I review first-line hormonal management options such as: birth control pills, progestin-only pills, levenogestrol IUD, etonogestrel implant, and medroxyprogesterone acetate injection. In my practice, most patients have already tried initial treatment options, and are most interested in other options. I then review second-line options such as GnRH agonists, antagonists, danazol, and aromatase inhibitors. For patients that have had chronic pelvic pain, I also discuss peripheral and central sensitization, and overlapping diagnoses. Surgical management includes diagnostic laparoscopy and excision or ablation of endometriosis, hysterectomy, and oophorectomy.

Are there specific factors that you look for to help you decide whether surgical management is necessary?

Dr. Lager: There are several reasons why patients decide to proceed with surgical management. First, some patients are reticent to start treatment, particularly if they have had negative experiences with hormonal medications and desire a definitive diagnosis. Other patients choose to proceed with surgery for fertility reasons, and others have severe symptoms that are not managed by medications.

The goal of surgery is to remove all visible endometriotic lesions, restore normal anatomy and for pathologic diagnosis if there is atypical characteristics of an endometrial mass. The pelvic exam and imaging can often be helpful surgical planning. If there is a deeply infiltrative lesion in the bowel or bladder, I consult my urology and colorectal colleagues for surgical planning.

Endometriotic lesions are heterogenous, and can include superficial peritoneal lesions, clear vesicular lesions, “powder burn lesions”, endometriomas, and deep infiltrative lesions.

Additionally, I counsel patients on surgical options depending on the fertility desires. For patients with infertility and symptoms of endometriosis, primary surgery with excision or ablation increases pregnancy rates. One meta-analysis showed that operative laparoscopy improved live births and ongoing pregnancy rates.[2] This was found for the first laparoscopic surgery and not repeat surgery.

Can you talk a little bit more about some of the advancements and the controversies in surgical management, and how that impacts your practice or your treatment?

Dr. Lager: Controversy in surgical management includes excision versus ablation in surgical management of endometriosis. One randomized controlled trial showed an improvement with dyspareunia with excision versus ablation after 5 year follow up.[3] However, a recent meta-analysis from 2021 showed no difference in dysmenorrhea between excision and ablation.[4] I generally perform excision of endometriosis as it can provide a tissue for diagnosis and may allow for complete excision of a lesion that may have an underlying component not easily seen.

We also discussed some of the controversy related to fertility and endometriosis. Management of endometriomas in the face of desired fertility is unclear. Endometriomas that are >3 cm in diameter are associated with decreased anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels, but ovarian cystectomy for endometriomas is also associated with decreased AMH levels. I will counsel patients regarding the risks and benefits of ovarian cystectomy and discuss with the reproductive endocrinologists if they recommend removal to improve oocyte retrieval.

Lastly, conservative versus definitive treatment is an important issue to discuss. Depending on a patient’s goals, conservative surgical management of endometriosis may be the most appropriate procedure. However, if a patient has multiple surgeries, does not desire to have children or has completed childbearing regardless of age and wants to decrease the risk of need for repeat surgery, I will discuss with patients that the risk of reoperation after hysterectomy versus conservative surgery is 8% vs 21% in 2 years and 59% vs 22% after 7 years, respectively.[5] Additionally, the patient may have an overlapping gynecological condition, such as adenomyosis or fibroids, and desire surgical management for those conditions as well. Management ultimately will depend on shared decision making,

You mentioned overlapping diagnosis. What are the impacts and barriers related to misdiagnosis or overlapping diagnosis, and what is your approach to recognizing those signs and symptoms?

Dr. Lager: The classic symptoms of endometriosis can overlap with several medical conditions. In addition to gynecologic issues such as adenomyosis and fibroids that I mentioned previously, symptoms such as pelvic pain, bloating, and dysuria can be associated with gastrointestinal conditions, painful bladder syndrome, neurologic, and musculoskeletal pain conditions. This is complex because the overlapping diagnoses can lead to misdiagnosis, and delay in diagnosis and missing an associated diagnosis can lead to inadequate treatment.

I approach the possibility of overlapping diagnoses in consultation with my colleagues who may recommend further testing, such as endoscopy and colonoscopy. Depending on the diagnoses, several treatments can be started concomitantly to address the multifactorial components of pain. For example, pelvic floor dysfunction related to pelvic pain can affect bowel habits, even without a diagnosis of IBS. Pelvic floor physical therapy can address one component of this. Similarly, even if we surgically or medically manage symptoms of endometriosis, the musculoskeletal pain can lead to persistent or worsening pain. The same goes for pain medicine and peripheral or central pain sensitization or neurological pain.

Was there anything else you’d like to share with your colleagues?

Dr. Lager: Endometriosis is a complex condition that requires a multifactorial approach that takes into consideration a patient’s goals. There is not a one-size fit for all patients with endometriosis due to all the issues we discussed. It will take time to address the varied components of pain and is an iterative process. Minimally invasive surgery has an important role in diagnosis and management of endometriosis but is one of several approaches to treat this complex condition. Thanks for taking the time to discuss this important condition that affects at least 10% of gynecological patients, and potentially more due to delayed and undiagnosed disease.

- Staal AH, van der Zanden M, Nap AW. Diagnostic delay of endometriosis in the Netherlands. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2016;81(4):321-4. doi: 10.1159/000441911

- Duffy JM, Arambage K, Correa FJ, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD011031. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;10:CD011031. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011031.pub2

- Healey M, Cheng C, Kaur H. To excise or ablate endometriosis? A prospective randomized double-blinded trial after 5-year follow-up. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(6):999-1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.04.002

- Burks C, Lee M, DeSarno M, Findley J, Flyckt R. Excision versus ablation for management of minimal to mild endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):587-597. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2020.11.028

- Shakiba K, Bena JF, McGill KM, Minger J, Falcone T. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: a 7-year follow-up on the requirement for further surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1285-92. Erratum in: Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(3):710. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181758ec6

- Staal AH, van der Zanden M, Nap AW. Diagnostic delay of endometriosis in the Netherlands. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2016;81(4):321-4. doi: 10.1159/000441911

- Duffy JM, Arambage K, Correa FJ, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD011031. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;10:CD011031. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011031.pub2

- Healey M, Cheng C, Kaur H. To excise or ablate endometriosis? A prospective randomized double-blinded trial after 5-year follow-up. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(6):999-1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.04.002

- Burks C, Lee M, DeSarno M, Findley J, Flyckt R. Excision versus ablation for management of minimal to mild endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):587-597. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2020.11.028

- Shakiba K, Bena JF, McGill KM, Minger J, Falcone T. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: a 7-year follow-up on the requirement for further surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1285-92. Erratum in: Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(3):710. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181758ec6

Müllerian anomalies – old problem, new approach and classification

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s classification system for müllerian anomalies was the standard until the revision in 2021 by ASRM, which updated and expanded the classification presenting nine classes and imaging criteria: müllerian agenesis, cervical agenesis, unicornuate, uterus didelphys, bicornuate, septate, longitudinal vaginal septum, transverse vaginal septum, and complex anomalies. This month’s article addresses müllerian anomalies from embryology to treatment options.

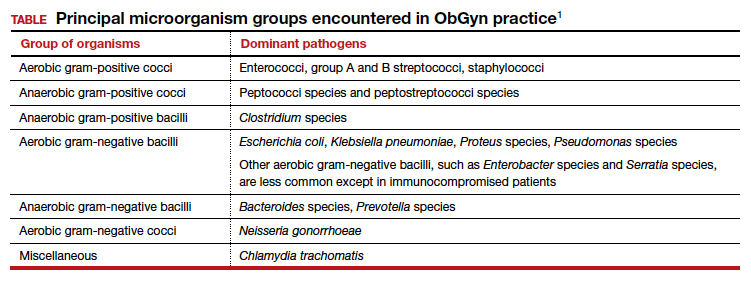

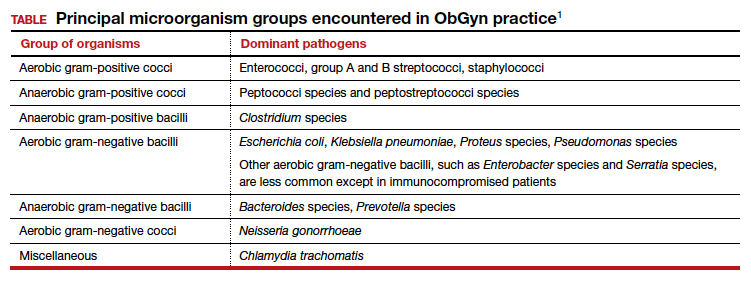

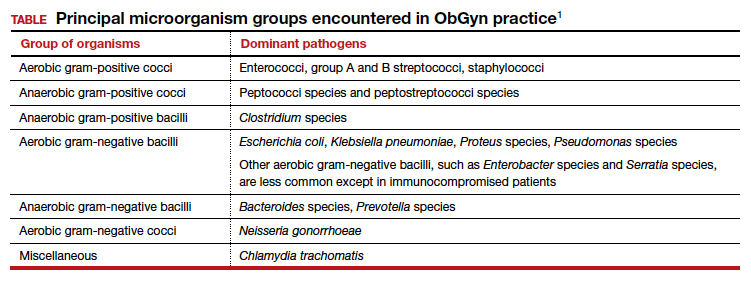

The early embryo has the capability of developing a wolffian (internal male) or müllerian (internal female) system. Unless anti-müllerian hormone (formerly müllerian-inhibiting substance) is produced, the embryo develops a female reproductive system beginning with two lateral uterine anlagen that fuse in the midline and canalize. Müllerian anomalies occur because of accidents during fusion and canalization (see Table).

The incidence of müllerian anomalies is difficult to discern, given the potential for a normal reproductive outcome precluding an evaluation and based on the population studied. Müllerian anomalies are found in approximately 4.3% of fertile women, 3.5%-8% of infertile patients, 12.3%-13% of those with recurrent pregnancy losses, and 24.5% of patients with miscarriage and infertility. Of the müllerian anomalies, the most common is septate (35%), followed by bicornuate (26%), arcuate (18%), unicornuate (10%), didelphys (8%), and agenesis (3%) (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161; Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17[6]:761-71).

In 20%-30% of patients with müllerian anomalies, particularly in women with a unicornuate uterus, renal anomalies exist that are typically ipsilateral to the absent or rudimentary contralateral uterine horn (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34[2]:154-60). As there is no definitive evidence to suggest an association between a septate uterus and renal anomalies, the renal system evaluation can be deferred in this population (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Diagnosis

2-D ultrasound can be a screen for müllerian anomalies and genitourinary anatomic variants. The diagnostic accuracy of 3-D ultrasound with müllerian anomalies is reported to be 97.6% with sensitivity and specificity of 98.3% and 99.4%, respectively (Hum. Reprod. 2016;31[1]:2-7). As a result, office 3-D has essentially replaced MRI in the diagnosis of müllerian anomalies (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Nov;46[5]:616-22), with one exception because of the avoidance of a transvaginal probe in the non–sexually active adult and younger adolescent/child. MRI is reserved for diagnosing complex müllerian anomalies or if there is a diagnostic challenge.

Criteria to diagnose müllerian anomalies by radiology begins with the “reference line,” i.e., a line joining both tubal ostia (interostial line). A septate uterus is diagnosed if the distance from the interostial line to the cephalad endometrium is more than 1 cm, otherwise it is considered normal or arcuate based on its appearance. An arcuate uterus has not been associated with impaired reproduction and can be viewed as a normal variant. Alternatively, a bicornuate uterus is diagnosed when the external fundal indentation is more than 1 cm (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Clinical course

Women with müllerian anomalies may experience pelvic pain and prolonged and/or abnormal bleeding at the time of menarche. While the ability to conceive may not be impaired from müllerian anomalies with the possible exception of the septate uterus, the pregnancy course can be affected, i.e., recurrent pregnancy loss, preterm birth, perinatal mortality, and malpresentation in labor (Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;29[6]:665). In women with septate, bicornuate, and uterine didelphys, fetal growth restriction appears to be increased. Spontaneous abortion rates of 32% and preterm birth rates of 28% have been reported in patients with uterus didelphys (Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75[6]:906).

Special consideration of the unicornuate is given because of the potential for a rudimentary horn that may communicate with the main uterine cavity and/or have functional endometrium which places the woman at risk of an ectopic pregnancy in the smaller horn. Patients with a unicornuate uterus are at higher risk for preterm labor and breech presentation. An obstructed (noncommunicating) functional rudimentary horn is a risk for endometriosis with cyclic pain because of outflow tract obstruction and an ectopic pregnancy prompting consideration for hemihysterectomy based on symptoms.

The septate uterus – old dogma revisited

The incidence of uterine septa is approximately 1-15 per 1,000. As the most common müllerian anomaly, the septate uterus has traditionally been associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion (21%-44%) and preterm birth (12%-33%). The live birth rate ranges from 50% to 72% (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161-74). A uterine septum is believed to develop as a result of failure of resorption of the tissue connecting the two paramesonephric (müllerian) ducts prior to the 20th embryonic week.

Incising the uterine septum (metroplasty) dates back to 1884 when Ruge described a blind transcervical metroplasty in a woman with two previous miscarriages who, postoperatively, delivered a healthy baby. In the early 1900s, Tompkins reported an abdominal metroplasty (Fertil Stertil. 2021;115:1140-2). The decision to proceed with metroplasty is based on only established observational studies (Fertil Steril. 2016;106:530-40). Until recently, the majority of studies suggested that metroplasty is associated with decreased spontaneous abortion rates and improved obstetrical outcomes. A retrospective case series of 361 patients with a septate uterus who had primary infertility of >2 years’ duration, a history of 1-2 spontaneous abortions, or recurrent pregnancy loss suggested a significant improvement in the live birth rate and reduction in miscarriage (Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;268:289-92). A meta-analysis found that the overall pregnancy rate after septum incision was 67.8% and the live-birth rate was 53.5% (J Minim Invas Gynecol. 2013;20:22-42).

Recently, two multinational studies question the prevailing dogma (Fertil Steril. 2021 Sep;116[3]:693-4). Both studies could not demonstrate any increase in live birth rate, reduction in preterm birth, or in pregnancy loss after metroplasty. A significant limitation was the lack of a uniform consensus on the definition of the septate uterus and allowing the discretion of the physician to diagnosis a septum (Hum Reprod. 2020;35:1578-88; Hum Reprod. 2021;36:1260-7).

Hysteroscopic metroplasty is not without complications. Uterine rupture during pregnancy or delivery, while rare, may be linked to significant entry into the myometrium and/or overzealous cauterization and perforation, which emphasizes the importance of appropriate techniques.

Conclusion

A diagnosis of müllerian anomalies justifies a comprehensive consultation with the patient given the risk of pregnancy complications. Management of the septate uterus has become controversial. In a patient with infertility, prior pregnancy loss, or poor obstetrical outcome, it is reasonable to consider metroplasty; otherwise, expectant management is an option.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s classification system for müllerian anomalies was the standard until the revision in 2021 by ASRM, which updated and expanded the classification presenting nine classes and imaging criteria: müllerian agenesis, cervical agenesis, unicornuate, uterus didelphys, bicornuate, septate, longitudinal vaginal septum, transverse vaginal septum, and complex anomalies. This month’s article addresses müllerian anomalies from embryology to treatment options.

The early embryo has the capability of developing a wolffian (internal male) or müllerian (internal female) system. Unless anti-müllerian hormone (formerly müllerian-inhibiting substance) is produced, the embryo develops a female reproductive system beginning with two lateral uterine anlagen that fuse in the midline and canalize. Müllerian anomalies occur because of accidents during fusion and canalization (see Table).

The incidence of müllerian anomalies is difficult to discern, given the potential for a normal reproductive outcome precluding an evaluation and based on the population studied. Müllerian anomalies are found in approximately 4.3% of fertile women, 3.5%-8% of infertile patients, 12.3%-13% of those with recurrent pregnancy losses, and 24.5% of patients with miscarriage and infertility. Of the müllerian anomalies, the most common is septate (35%), followed by bicornuate (26%), arcuate (18%), unicornuate (10%), didelphys (8%), and agenesis (3%) (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161; Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17[6]:761-71).

In 20%-30% of patients with müllerian anomalies, particularly in women with a unicornuate uterus, renal anomalies exist that are typically ipsilateral to the absent or rudimentary contralateral uterine horn (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34[2]:154-60). As there is no definitive evidence to suggest an association between a septate uterus and renal anomalies, the renal system evaluation can be deferred in this population (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Diagnosis

2-D ultrasound can be a screen for müllerian anomalies and genitourinary anatomic variants. The diagnostic accuracy of 3-D ultrasound with müllerian anomalies is reported to be 97.6% with sensitivity and specificity of 98.3% and 99.4%, respectively (Hum. Reprod. 2016;31[1]:2-7). As a result, office 3-D has essentially replaced MRI in the diagnosis of müllerian anomalies (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Nov;46[5]:616-22), with one exception because of the avoidance of a transvaginal probe in the non–sexually active adult and younger adolescent/child. MRI is reserved for diagnosing complex müllerian anomalies or if there is a diagnostic challenge.

Criteria to diagnose müllerian anomalies by radiology begins with the “reference line,” i.e., a line joining both tubal ostia (interostial line). A septate uterus is diagnosed if the distance from the interostial line to the cephalad endometrium is more than 1 cm, otherwise it is considered normal or arcuate based on its appearance. An arcuate uterus has not been associated with impaired reproduction and can be viewed as a normal variant. Alternatively, a bicornuate uterus is diagnosed when the external fundal indentation is more than 1 cm (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Clinical course

Women with müllerian anomalies may experience pelvic pain and prolonged and/or abnormal bleeding at the time of menarche. While the ability to conceive may not be impaired from müllerian anomalies with the possible exception of the septate uterus, the pregnancy course can be affected, i.e., recurrent pregnancy loss, preterm birth, perinatal mortality, and malpresentation in labor (Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;29[6]:665). In women with septate, bicornuate, and uterine didelphys, fetal growth restriction appears to be increased. Spontaneous abortion rates of 32% and preterm birth rates of 28% have been reported in patients with uterus didelphys (Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75[6]:906).

Special consideration of the unicornuate is given because of the potential for a rudimentary horn that may communicate with the main uterine cavity and/or have functional endometrium which places the woman at risk of an ectopic pregnancy in the smaller horn. Patients with a unicornuate uterus are at higher risk for preterm labor and breech presentation. An obstructed (noncommunicating) functional rudimentary horn is a risk for endometriosis with cyclic pain because of outflow tract obstruction and an ectopic pregnancy prompting consideration for hemihysterectomy based on symptoms.

The septate uterus – old dogma revisited

The incidence of uterine septa is approximately 1-15 per 1,000. As the most common müllerian anomaly, the septate uterus has traditionally been associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion (21%-44%) and preterm birth (12%-33%). The live birth rate ranges from 50% to 72% (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161-74). A uterine septum is believed to develop as a result of failure of resorption of the tissue connecting the two paramesonephric (müllerian) ducts prior to the 20th embryonic week.

Incising the uterine septum (metroplasty) dates back to 1884 when Ruge described a blind transcervical metroplasty in a woman with two previous miscarriages who, postoperatively, delivered a healthy baby. In the early 1900s, Tompkins reported an abdominal metroplasty (Fertil Stertil. 2021;115:1140-2). The decision to proceed with metroplasty is based on only established observational studies (Fertil Steril. 2016;106:530-40). Until recently, the majority of studies suggested that metroplasty is associated with decreased spontaneous abortion rates and improved obstetrical outcomes. A retrospective case series of 361 patients with a septate uterus who had primary infertility of >2 years’ duration, a history of 1-2 spontaneous abortions, or recurrent pregnancy loss suggested a significant improvement in the live birth rate and reduction in miscarriage (Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;268:289-92). A meta-analysis found that the overall pregnancy rate after septum incision was 67.8% and the live-birth rate was 53.5% (J Minim Invas Gynecol. 2013;20:22-42).

Recently, two multinational studies question the prevailing dogma (Fertil Steril. 2021 Sep;116[3]:693-4). Both studies could not demonstrate any increase in live birth rate, reduction in preterm birth, or in pregnancy loss after metroplasty. A significant limitation was the lack of a uniform consensus on the definition of the septate uterus and allowing the discretion of the physician to diagnosis a septum (Hum Reprod. 2020;35:1578-88; Hum Reprod. 2021;36:1260-7).

Hysteroscopic metroplasty is not without complications. Uterine rupture during pregnancy or delivery, while rare, may be linked to significant entry into the myometrium and/or overzealous cauterization and perforation, which emphasizes the importance of appropriate techniques.

Conclusion

A diagnosis of müllerian anomalies justifies a comprehensive consultation with the patient given the risk of pregnancy complications. Management of the septate uterus has become controversial. In a patient with infertility, prior pregnancy loss, or poor obstetrical outcome, it is reasonable to consider metroplasty; otherwise, expectant management is an option.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s classification system for müllerian anomalies was the standard until the revision in 2021 by ASRM, which updated and expanded the classification presenting nine classes and imaging criteria: müllerian agenesis, cervical agenesis, unicornuate, uterus didelphys, bicornuate, septate, longitudinal vaginal septum, transverse vaginal septum, and complex anomalies. This month’s article addresses müllerian anomalies from embryology to treatment options.

The early embryo has the capability of developing a wolffian (internal male) or müllerian (internal female) system. Unless anti-müllerian hormone (formerly müllerian-inhibiting substance) is produced, the embryo develops a female reproductive system beginning with two lateral uterine anlagen that fuse in the midline and canalize. Müllerian anomalies occur because of accidents during fusion and canalization (see Table).

The incidence of müllerian anomalies is difficult to discern, given the potential for a normal reproductive outcome precluding an evaluation and based on the population studied. Müllerian anomalies are found in approximately 4.3% of fertile women, 3.5%-8% of infertile patients, 12.3%-13% of those with recurrent pregnancy losses, and 24.5% of patients with miscarriage and infertility. Of the müllerian anomalies, the most common is septate (35%), followed by bicornuate (26%), arcuate (18%), unicornuate (10%), didelphys (8%), and agenesis (3%) (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161; Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17[6]:761-71).

In 20%-30% of patients with müllerian anomalies, particularly in women with a unicornuate uterus, renal anomalies exist that are typically ipsilateral to the absent or rudimentary contralateral uterine horn (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34[2]:154-60). As there is no definitive evidence to suggest an association between a septate uterus and renal anomalies, the renal system evaluation can be deferred in this population (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Diagnosis

2-D ultrasound can be a screen for müllerian anomalies and genitourinary anatomic variants. The diagnostic accuracy of 3-D ultrasound with müllerian anomalies is reported to be 97.6% with sensitivity and specificity of 98.3% and 99.4%, respectively (Hum. Reprod. 2016;31[1]:2-7). As a result, office 3-D has essentially replaced MRI in the diagnosis of müllerian anomalies (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Nov;46[5]:616-22), with one exception because of the avoidance of a transvaginal probe in the non–sexually active adult and younger adolescent/child. MRI is reserved for diagnosing complex müllerian anomalies or if there is a diagnostic challenge.

Criteria to diagnose müllerian anomalies by radiology begins with the “reference line,” i.e., a line joining both tubal ostia (interostial line). A septate uterus is diagnosed if the distance from the interostial line to the cephalad endometrium is more than 1 cm, otherwise it is considered normal or arcuate based on its appearance. An arcuate uterus has not been associated with impaired reproduction and can be viewed as a normal variant. Alternatively, a bicornuate uterus is diagnosed when the external fundal indentation is more than 1 cm (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Clinical course

Women with müllerian anomalies may experience pelvic pain and prolonged and/or abnormal bleeding at the time of menarche. While the ability to conceive may not be impaired from müllerian anomalies with the possible exception of the septate uterus, the pregnancy course can be affected, i.e., recurrent pregnancy loss, preterm birth, perinatal mortality, and malpresentation in labor (Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;29[6]:665). In women with septate, bicornuate, and uterine didelphys, fetal growth restriction appears to be increased. Spontaneous abortion rates of 32% and preterm birth rates of 28% have been reported in patients with uterus didelphys (Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75[6]:906).

Special consideration of the unicornuate is given because of the potential for a rudimentary horn that may communicate with the main uterine cavity and/or have functional endometrium which places the woman at risk of an ectopic pregnancy in the smaller horn. Patients with a unicornuate uterus are at higher risk for preterm labor and breech presentation. An obstructed (noncommunicating) functional rudimentary horn is a risk for endometriosis with cyclic pain because of outflow tract obstruction and an ectopic pregnancy prompting consideration for hemihysterectomy based on symptoms.

The septate uterus – old dogma revisited

The incidence of uterine septa is approximately 1-15 per 1,000. As the most common müllerian anomaly, the septate uterus has traditionally been associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion (21%-44%) and preterm birth (12%-33%). The live birth rate ranges from 50% to 72% (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161-74). A uterine septum is believed to develop as a result of failure of resorption of the tissue connecting the two paramesonephric (müllerian) ducts prior to the 20th embryonic week.

Incising the uterine septum (metroplasty) dates back to 1884 when Ruge described a blind transcervical metroplasty in a woman with two previous miscarriages who, postoperatively, delivered a healthy baby. In the early 1900s, Tompkins reported an abdominal metroplasty (Fertil Stertil. 2021;115:1140-2). The decision to proceed with metroplasty is based on only established observational studies (Fertil Steril. 2016;106:530-40). Until recently, the majority of studies suggested that metroplasty is associated with decreased spontaneous abortion rates and improved obstetrical outcomes. A retrospective case series of 361 patients with a septate uterus who had primary infertility of >2 years’ duration, a history of 1-2 spontaneous abortions, or recurrent pregnancy loss suggested a significant improvement in the live birth rate and reduction in miscarriage (Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;268:289-92). A meta-analysis found that the overall pregnancy rate after septum incision was 67.8% and the live-birth rate was 53.5% (J Minim Invas Gynecol. 2013;20:22-42).

Recently, two multinational studies question the prevailing dogma (Fertil Steril. 2021 Sep;116[3]:693-4). Both studies could not demonstrate any increase in live birth rate, reduction in preterm birth, or in pregnancy loss after metroplasty. A significant limitation was the lack of a uniform consensus on the definition of the septate uterus and allowing the discretion of the physician to diagnosis a septum (Hum Reprod. 2020;35:1578-88; Hum Reprod. 2021;36:1260-7).

Hysteroscopic metroplasty is not without complications. Uterine rupture during pregnancy or delivery, while rare, may be linked to significant entry into the myometrium and/or overzealous cauterization and perforation, which emphasizes the importance of appropriate techniques.

Conclusion

A diagnosis of müllerian anomalies justifies a comprehensive consultation with the patient given the risk of pregnancy complications. Management of the septate uterus has become controversial. In a patient with infertility, prior pregnancy loss, or poor obstetrical outcome, it is reasonable to consider metroplasty; otherwise, expectant management is an option.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Doxycycline bests azithromycin for anorectal chlamydia in women

NEW YORK (Reuters) – A one-week course of doxycycline was superior to a single dose of azithromycin in women with concurrent vaginal and anorectal chlamydia infection in an unblinded randomized controlled trial, mirroring previous results in men.

Researchers suggest that doxycycline should be the first-line therapy for chlamydia infection in women.

“It is clear we must consider that any woman with a urogenital infection must have an effective treatment for the anal infection, since nearly 80% of women have an anal infection concomitant with the vaginal infection,” Dr. Bertille de Barbeyrac of the University of Bordeaux, France, told Reuters Health by email.

However, she noted that “even [though] the study shows that doxycycline is more effective than azithromycin on anal infection, other studies are needed to prove that residual anal infection after treatment with azithromycin can be a source of vaginal contamination and therefore justify changing practices and eliminating azithromycin as a treatment for lower urogenital chlamydial infection in women.”

“There are other reasons [to make] this change,” she added, “such as the acquisition of macrolide resistance by M. genitalium following heavy use of azithromycin.”

As reported in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Dr. Barbeyrac and colleagues randomly assigned 460 women (median age, 21) to either doxycycline or azithromycin in a multicenter, open-label superiority trial.

Participants received either azithromycin (a single 1-g dose, with or without food) or doxycycline (100 mg in the morning and evening at mealtimes for 7 days – that is, 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily).

The primary outcome was that the microbiological anorectal cure rate, defined as a C. trachomatis-negative nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT), resulted in anorectal specimens six weeks after treatment initiation among women who had a baseline positive result (about half the women in each treatment group).

Ninety-four percent of the doxycycline group versus 85% of the azithromycin group had an anorectal cure (adjusted odds ratio with imputation of missing values, 0.43).

Adverse events possibly related to treatment occurred in 11% of the doxycycline group versus 13% of the azithromycin group. Gastrointestinal disorders were most frequent, occurring in 8% of the doxycycline and 11% of the azithromycin groups.

Summing up, the authors write, “The microbiological anorectal cure rate was significantly lower among women who received a single dose of azithromycin than among those who received a 1-week course of doxycycline. This finding suggests that doxycycline should be the first-line therapy for C trachomatis infection in women.”

Dr. Meleen Chuang, medical director of women’s health at the Family Health Centers at NYU Langone, Brooklyn, commented in an email to Reuters Health that after reviewing this study “as well as CDC and WHO recommendations updated as of 2022, health care providers should be treating C. trachomatis infections with doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for seven days as first-line therapy rather than azithromycin, [given] concerns of increasing macrolide drug resistance against Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhea.”

“Our clinicians also see the growing uptick of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia infections in our population, similarly to the rest of the United States since 2020,” she noted. “With the increase in STD infection ... treatment with doxycycline therapy with an important caveat to the patient to complete the one-week treatment regimen is extremely important.”

Dr. Latasha Murphy of the Gynecologic Care Institute at Mercy, Baltimore, also commented in an email to Reuters Health. She noted, “this study does not mirror my clinical experience. More patients have side effects from doxycycline than azithromycin in my experience. Also, anorectal screening is not routine in STD screening.”

“If any major changes to clinical care are made,” she said, “it may be for more consistent screening for anorectal disease. This may ultimately lead to doxycycline being the first line-treatment. More research is needed before making any definitive changes.”

Reuters Health Information © 2022

NEW YORK (Reuters) – A one-week course of doxycycline was superior to a single dose of azithromycin in women with concurrent vaginal and anorectal chlamydia infection in an unblinded randomized controlled trial, mirroring previous results in men.

Researchers suggest that doxycycline should be the first-line therapy for chlamydia infection in women.

“It is clear we must consider that any woman with a urogenital infection must have an effective treatment for the anal infection, since nearly 80% of women have an anal infection concomitant with the vaginal infection,” Dr. Bertille de Barbeyrac of the University of Bordeaux, France, told Reuters Health by email.

However, she noted that “even [though] the study shows that doxycycline is more effective than azithromycin on anal infection, other studies are needed to prove that residual anal infection after treatment with azithromycin can be a source of vaginal contamination and therefore justify changing practices and eliminating azithromycin as a treatment for lower urogenital chlamydial infection in women.”

“There are other reasons [to make] this change,” she added, “such as the acquisition of macrolide resistance by M. genitalium following heavy use of azithromycin.”

As reported in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Dr. Barbeyrac and colleagues randomly assigned 460 women (median age, 21) to either doxycycline or azithromycin in a multicenter, open-label superiority trial.

Participants received either azithromycin (a single 1-g dose, with or without food) or doxycycline (100 mg in the morning and evening at mealtimes for 7 days – that is, 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily).

The primary outcome was that the microbiological anorectal cure rate, defined as a C. trachomatis-negative nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT), resulted in anorectal specimens six weeks after treatment initiation among women who had a baseline positive result (about half the women in each treatment group).

Ninety-four percent of the doxycycline group versus 85% of the azithromycin group had an anorectal cure (adjusted odds ratio with imputation of missing values, 0.43).

Adverse events possibly related to treatment occurred in 11% of the doxycycline group versus 13% of the azithromycin group. Gastrointestinal disorders were most frequent, occurring in 8% of the doxycycline and 11% of the azithromycin groups.

Summing up, the authors write, “The microbiological anorectal cure rate was significantly lower among women who received a single dose of azithromycin than among those who received a 1-week course of doxycycline. This finding suggests that doxycycline should be the first-line therapy for C trachomatis infection in women.”

Dr. Meleen Chuang, medical director of women’s health at the Family Health Centers at NYU Langone, Brooklyn, commented in an email to Reuters Health that after reviewing this study “as well as CDC and WHO recommendations updated as of 2022, health care providers should be treating C. trachomatis infections with doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for seven days as first-line therapy rather than azithromycin, [given] concerns of increasing macrolide drug resistance against Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhea.”

“Our clinicians also see the growing uptick of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia infections in our population, similarly to the rest of the United States since 2020,” she noted. “With the increase in STD infection ... treatment with doxycycline therapy with an important caveat to the patient to complete the one-week treatment regimen is extremely important.”

Dr. Latasha Murphy of the Gynecologic Care Institute at Mercy, Baltimore, also commented in an email to Reuters Health. She noted, “this study does not mirror my clinical experience. More patients have side effects from doxycycline than azithromycin in my experience. Also, anorectal screening is not routine in STD screening.”

“If any major changes to clinical care are made,” she said, “it may be for more consistent screening for anorectal disease. This may ultimately lead to doxycycline being the first line-treatment. More research is needed before making any definitive changes.”

Reuters Health Information © 2022

NEW YORK (Reuters) – A one-week course of doxycycline was superior to a single dose of azithromycin in women with concurrent vaginal and anorectal chlamydia infection in an unblinded randomized controlled trial, mirroring previous results in men.

Researchers suggest that doxycycline should be the first-line therapy for chlamydia infection in women.

“It is clear we must consider that any woman with a urogenital infection must have an effective treatment for the anal infection, since nearly 80% of women have an anal infection concomitant with the vaginal infection,” Dr. Bertille de Barbeyrac of the University of Bordeaux, France, told Reuters Health by email.

However, she noted that “even [though] the study shows that doxycycline is more effective than azithromycin on anal infection, other studies are needed to prove that residual anal infection after treatment with azithromycin can be a source of vaginal contamination and therefore justify changing practices and eliminating azithromycin as a treatment for lower urogenital chlamydial infection in women.”

“There are other reasons [to make] this change,” she added, “such as the acquisition of macrolide resistance by M. genitalium following heavy use of azithromycin.”

As reported in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Dr. Barbeyrac and colleagues randomly assigned 460 women (median age, 21) to either doxycycline or azithromycin in a multicenter, open-label superiority trial.

Participants received either azithromycin (a single 1-g dose, with or without food) or doxycycline (100 mg in the morning and evening at mealtimes for 7 days – that is, 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily).

The primary outcome was that the microbiological anorectal cure rate, defined as a C. trachomatis-negative nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT), resulted in anorectal specimens six weeks after treatment initiation among women who had a baseline positive result (about half the women in each treatment group).

Ninety-four percent of the doxycycline group versus 85% of the azithromycin group had an anorectal cure (adjusted odds ratio with imputation of missing values, 0.43).

Adverse events possibly related to treatment occurred in 11% of the doxycycline group versus 13% of the azithromycin group. Gastrointestinal disorders were most frequent, occurring in 8% of the doxycycline and 11% of the azithromycin groups.

Summing up, the authors write, “The microbiological anorectal cure rate was significantly lower among women who received a single dose of azithromycin than among those who received a 1-week course of doxycycline. This finding suggests that doxycycline should be the first-line therapy for C trachomatis infection in women.”

Dr. Meleen Chuang, medical director of women’s health at the Family Health Centers at NYU Langone, Brooklyn, commented in an email to Reuters Health that after reviewing this study “as well as CDC and WHO recommendations updated as of 2022, health care providers should be treating C. trachomatis infections with doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for seven days as first-line therapy rather than azithromycin, [given] concerns of increasing macrolide drug resistance against Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhea.”

“Our clinicians also see the growing uptick of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia infections in our population, similarly to the rest of the United States since 2020,” she noted. “With the increase in STD infection ... treatment with doxycycline therapy with an important caveat to the patient to complete the one-week treatment regimen is extremely important.”

Dr. Latasha Murphy of the Gynecologic Care Institute at Mercy, Baltimore, also commented in an email to Reuters Health. She noted, “this study does not mirror my clinical experience. More patients have side effects from doxycycline than azithromycin in my experience. Also, anorectal screening is not routine in STD screening.”