User login

STS: Score stratifies risks for isolated tricuspid valve surgery patients

PHOENIX – A team of cardiac surgeons has developed the first clinical risk score for predicting the risk that patients face for operative mortality and postsurgical major morbidity when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement.

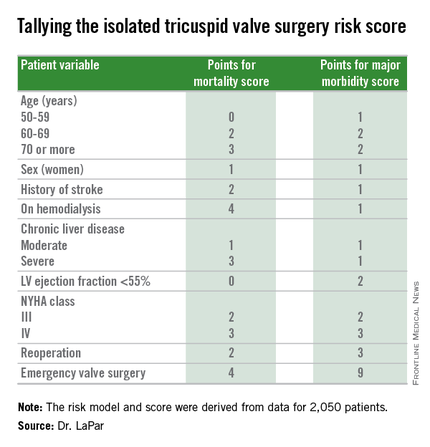

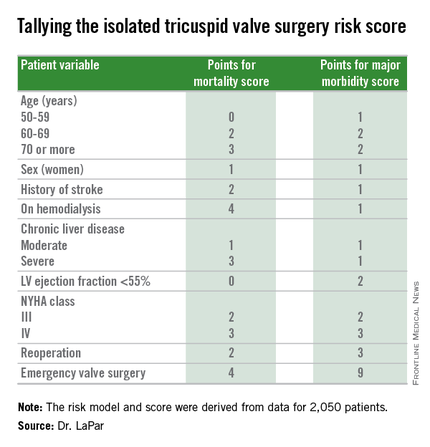

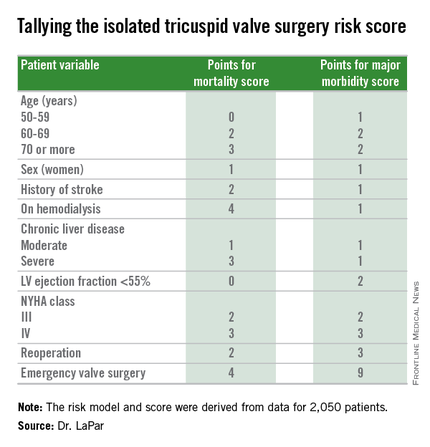

The risk score uses nine easily collected variables, and the derived model discriminates outcomes based on patients who score from 0-10 or more points on both a mortality and a morbidity risk scale, Dr. Damien J. LaPar said at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The risk scores allow surgeons to better describe and quantify to patients considering isolated tricuspid valve surgery the risks they face from the operation, and they have already been incorporated into practice at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, where Dr. LaPar practices.

“Patients love to better understand their risks. We can provide them with empirical data from a large, heterogeneous population that are better than a surgeon’s gut feeling” about the risks they face, said Dr. LaPar, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University.

Another consequence of having the new risk model and score is that it identified certain key risk factors that are controllable, and thereby, “makes the case for early referrals” for isolated tricuspid valve surgery, Dr. LaPar said in an interview. For example, the risk score shows that patients who are older, on hemodialysis, have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, or require emergency intervention all contribute to worse outcomes, compared with patients who are younger, have better renal function, better cardiac output, or can be treated on a more routine basis.

Many physicians have viewed isolated tricuspid valve surgery as posing similar risks to all patients, with an overall average operative mortality rate of about 10%, he noted. The new risk score model shows that some patients who are younger and healthier have operative mortality rates below 5%, while older and sicker patients have rates that can surpass 20%.

“Our data show a spectrum of risk, and that it is better to operate sooner than later. That is the huge clinical message of these data,” Dr. LaPar said.

Designated discussant Dr. Michael A. Acker noted that the risk score for tricuspid-valve surgery “is a first of its kind and a major contribution.” Dr. Acker is professor of surgery and chief of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He is a consultant to Thoratec and HeartWare.

Dr. LaPar and his associates derived the risk model and score from data collected on 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement at 49 hospitals in Virginia or Michigan during 2002-2014. The data came from databases maintained by the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative and by the Michigan Society of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgeons, and reported to the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The model they developed showed operative mortality rates that ranged from 2%, for patients with a mortality score of zero, to 34% for patients with a score of 10 or more. It further showed major morbidity rates of 13%, for patients with a morbidity score of zero, to 71% for those with a score of 10 or more. Scoring for mortality uses a slightly different system than the scoring for morbidity, so the scores must be calculated individually, and the score totals for a patient can differ for each endpoint. The maximum score is 22 for mortality and 23 for morbidity.

Only 5%-15% of patients undergoing tricuspid valve surgery have an isolated procedure, so a relatively limited number of patients fall into this category, a fact that has in the past limited collection of data from large numbers of patients. The dataset used for this analysis, with 2,050 patients “is one of the largest series collected,” and made possible derivation of a robust risk model and scoring system. Future analysis of even more patients should further improve the model and scoring system.

“These data set the stage for looking at national-level data to further refine the model and make it even more generalizable,” Dr. LaPar said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – A team of cardiac surgeons has developed the first clinical risk score for predicting the risk that patients face for operative mortality and postsurgical major morbidity when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement.

The risk score uses nine easily collected variables, and the derived model discriminates outcomes based on patients who score from 0-10 or more points on both a mortality and a morbidity risk scale, Dr. Damien J. LaPar said at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The risk scores allow surgeons to better describe and quantify to patients considering isolated tricuspid valve surgery the risks they face from the operation, and they have already been incorporated into practice at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, where Dr. LaPar practices.

“Patients love to better understand their risks. We can provide them with empirical data from a large, heterogeneous population that are better than a surgeon’s gut feeling” about the risks they face, said Dr. LaPar, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University.

Another consequence of having the new risk model and score is that it identified certain key risk factors that are controllable, and thereby, “makes the case for early referrals” for isolated tricuspid valve surgery, Dr. LaPar said in an interview. For example, the risk score shows that patients who are older, on hemodialysis, have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, or require emergency intervention all contribute to worse outcomes, compared with patients who are younger, have better renal function, better cardiac output, or can be treated on a more routine basis.

Many physicians have viewed isolated tricuspid valve surgery as posing similar risks to all patients, with an overall average operative mortality rate of about 10%, he noted. The new risk score model shows that some patients who are younger and healthier have operative mortality rates below 5%, while older and sicker patients have rates that can surpass 20%.

“Our data show a spectrum of risk, and that it is better to operate sooner than later. That is the huge clinical message of these data,” Dr. LaPar said.

Designated discussant Dr. Michael A. Acker noted that the risk score for tricuspid-valve surgery “is a first of its kind and a major contribution.” Dr. Acker is professor of surgery and chief of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He is a consultant to Thoratec and HeartWare.

Dr. LaPar and his associates derived the risk model and score from data collected on 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement at 49 hospitals in Virginia or Michigan during 2002-2014. The data came from databases maintained by the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative and by the Michigan Society of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgeons, and reported to the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The model they developed showed operative mortality rates that ranged from 2%, for patients with a mortality score of zero, to 34% for patients with a score of 10 or more. It further showed major morbidity rates of 13%, for patients with a morbidity score of zero, to 71% for those with a score of 10 or more. Scoring for mortality uses a slightly different system than the scoring for morbidity, so the scores must be calculated individually, and the score totals for a patient can differ for each endpoint. The maximum score is 22 for mortality and 23 for morbidity.

Only 5%-15% of patients undergoing tricuspid valve surgery have an isolated procedure, so a relatively limited number of patients fall into this category, a fact that has in the past limited collection of data from large numbers of patients. The dataset used for this analysis, with 2,050 patients “is one of the largest series collected,” and made possible derivation of a robust risk model and scoring system. Future analysis of even more patients should further improve the model and scoring system.

“These data set the stage for looking at national-level data to further refine the model and make it even more generalizable,” Dr. LaPar said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – A team of cardiac surgeons has developed the first clinical risk score for predicting the risk that patients face for operative mortality and postsurgical major morbidity when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement.

The risk score uses nine easily collected variables, and the derived model discriminates outcomes based on patients who score from 0-10 or more points on both a mortality and a morbidity risk scale, Dr. Damien J. LaPar said at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The risk scores allow surgeons to better describe and quantify to patients considering isolated tricuspid valve surgery the risks they face from the operation, and they have already been incorporated into practice at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, where Dr. LaPar practices.

“Patients love to better understand their risks. We can provide them with empirical data from a large, heterogeneous population that are better than a surgeon’s gut feeling” about the risks they face, said Dr. LaPar, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University.

Another consequence of having the new risk model and score is that it identified certain key risk factors that are controllable, and thereby, “makes the case for early referrals” for isolated tricuspid valve surgery, Dr. LaPar said in an interview. For example, the risk score shows that patients who are older, on hemodialysis, have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, or require emergency intervention all contribute to worse outcomes, compared with patients who are younger, have better renal function, better cardiac output, or can be treated on a more routine basis.

Many physicians have viewed isolated tricuspid valve surgery as posing similar risks to all patients, with an overall average operative mortality rate of about 10%, he noted. The new risk score model shows that some patients who are younger and healthier have operative mortality rates below 5%, while older and sicker patients have rates that can surpass 20%.

“Our data show a spectrum of risk, and that it is better to operate sooner than later. That is the huge clinical message of these data,” Dr. LaPar said.

Designated discussant Dr. Michael A. Acker noted that the risk score for tricuspid-valve surgery “is a first of its kind and a major contribution.” Dr. Acker is professor of surgery and chief of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He is a consultant to Thoratec and HeartWare.

Dr. LaPar and his associates derived the risk model and score from data collected on 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement at 49 hospitals in Virginia or Michigan during 2002-2014. The data came from databases maintained by the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative and by the Michigan Society of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgeons, and reported to the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The model they developed showed operative mortality rates that ranged from 2%, for patients with a mortality score of zero, to 34% for patients with a score of 10 or more. It further showed major morbidity rates of 13%, for patients with a morbidity score of zero, to 71% for those with a score of 10 or more. Scoring for mortality uses a slightly different system than the scoring for morbidity, so the scores must be calculated individually, and the score totals for a patient can differ for each endpoint. The maximum score is 22 for mortality and 23 for morbidity.

Only 5%-15% of patients undergoing tricuspid valve surgery have an isolated procedure, so a relatively limited number of patients fall into this category, a fact that has in the past limited collection of data from large numbers of patients. The dataset used for this analysis, with 2,050 patients “is one of the largest series collected,” and made possible derivation of a robust risk model and scoring system. Future analysis of even more patients should further improve the model and scoring system.

“These data set the stage for looking at national-level data to further refine the model and make it even more generalizable,” Dr. LaPar said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A risk-scoring system estimates a patient’s mortality and morbidity risk when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve surgery.

Major finding: The scoring system discriminated mortality risk from 2% to 34%, and major morbidity risk from 13% to 71%.

Data source: Analysis of 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve surgery in the STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Database.

Disclosures: Dr. LaPar had no disclosures.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Who should get an ICD?

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Since the 2011 release of the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, several new evidence-based tools have emerged as being helpful in decision making regarding which patients should receive an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death, Dr. Rick A. Nishimura said at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

These three tools – gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging, a novel European risk score calculator, and a new appreciation of the importance of age-related risk – are most useful in the many cases of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) where the cardiologist is on the fence regarding ICD placement because the patient doesn’t clearly meet the conventional major criteria for an ICD, according to Dr. Nishimura, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Nishimura, a member of the writing panel for the current guidelines (Circulation. 2011 Dec 13;124[24]:2761-96), predicted these tools will be incorporated into the next iteration of the HCM guidelines.

Notably absent from Dr. Nishimura’s list of useful tools was genetic testing for assessment of SCD risk in a patient with HCM.

“You should not spend $6,000 to do a genetic study to try to predict who’s at risk for sudden death. It turns out that most mutations are neither inherently benign nor malignant. High-risk mutations come from high-risk families, so you can do just as well by taking a family history,” according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Nishimura explained that the clinical dilemma in trying to evaluate SCD risk in a patient who presents with HCM is that the overall risk is quite low – probably 1% or less per year in the total HCM population – yet HCM is the number-one cause of SCD in younger patients. And it can occur unpredictably years or decades after diagnosis of HCM.

While ICDs are of proven effectiveness in preventing SCD in patients with HCM, reliance solely upon the conventional risk predictors to identify those who should get a device is clearly inadequate. Those criteria have a positive predictive accuracy of less than 15%; in other words, roughly 85% of HCM patients who get an ICD never receive an appropriate, life-saving shock, Dr. Nishimura said.

“We have a lot of work left to do in order to better identify these patients. In our own data from the Mayo Clinic, 20%-25% of patients have inappropriate ICD shocks despite efforts to program the device to prevent such shocks. That’s especially common in younger, active patients with HCM, and when it occurs patients find it absolutely devastating,” according to the cardiologist.

As stated in the current guidelines, the established SCD risk factors that provide a strong indication for an ICD in a patient with HCM are prior documented cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillation, or hemodynamically significant ventricular tachycardia. Additionally, risk factors which, in Dr. Nishimura’s view, probably warrant insertion of an ICD and, at the very least should trigger a physician-patient discussion about the risks and benefits of preventive device therapy, include a family history of HCM-related sudden death in a first-degree relative, massive left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy as defined by a maximum wall thickness of at least 30 mm, and recent unexplained syncope inconsistent with neurocardiogenic origin.

Less potent risk predictors where savvy clinical judgment becomes imperative include nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on 24-hour Holter monitoring, a hypotensive blood pressure response to exercise, and an increased LV wall thickness in a younger patient that doesn’t rise to the 30-mm standard. These are situations where gadolinium-enhanced MRI, consideration of patient age, and the European risk scoring system can help in the decision-making process, he said.

Gadolinium-enhanced MRI: Contrast-enhanced cardiovascular MRI with late gadolinium enhancement has emerged as a reliable marker of the myocyte disarray and interstitial fibrosis which serves as a substrate for ventricular arrhythmias. In a recent study of 1,293 HCM patients followed for a median of 3.3 years, the incidence of SCD events increased progressively with the extent of late gadolinium enhancement. Extensive late gadolinium enhancement, defined as involving at least 15% of LV mass, was associated with a doubled risk of SCD events in patients otherwise considered at low risk (Circulation. 2014 Aug 5;130[6]:484-95).

“This is probably going to become one of the key markers that can help you when you’re on the fence as to whether or not to put in an ICD. We’re getting MRIs with gadolinium now in all of our HCM patients. What matters is not gadolinium enhancement at the insertion of the left ventricle into the septum – a lot of people have that – but diffuse gadolinium enhancement throughout the septum,” Dr. Nishimura said.

Because SCD risk increases linearly with greater maximal LV wall thickness, gadolinium-enhanced MRI is particularly helpful in assessing risk in a younger patient with a maximal LV wall thickness of, say, 26 mm, he added.

Age: A study by led by Dr. Barry J. Maron, the cochair of the 2011 guideline committee and director of the HCM center at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, provides a new understanding that prophylactic ICD implantation is not warranted in patients with HCM who present at age 60 or older. In their study of 428 consecutive patients presenting with HCM at age 60 or above, the investigators found during 5.8 years of follow-up that the incidence of arrhythmic sudden death events was just 0.2% per year (Circulation. 2013 Feb 5;127[5]:585-93).

“They’ve shown that if you look at patients age 60 or above who have HCM, the risk of sudden cardiac death is almost nonexistent. That’s incredibly important to remember. Sudden death is something that’s going to happen in the younger population, under age 30,” Dr. Nishimura emphasized.

European SCD risk prediction tool: This tool was hailed as a major advance in the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines on HCM (Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2733-2779). The tool was incorporated into the guidelines. It is also available as a smartphone app.

The risk prediction tool (Eur Heart J. 2014 Aug 7;35[30]:2010-20) is a complex equation that incorporates seven predictive factors: age, maximal LV wall thickness, left atrial diameter, LV outflow tract gradient, family history of SCD, nonsustained VT, and unexplained syncope. After input on these seven factors, the equation spits out an individual’s estimated 5-year SCD risk. Based on the study of 3,675 consecutive HCM patients with a median 5.7 years of follow-up that was used to develop the risk equation, the current ESC guidelines state that an ICD is not warranted in HCM patients with a 5-year risk below 4%, device implantation should be considered in those whose risk is 4%-6%, and an ICD should be even more strongly considered in patients with a 5-year risk in excess of 6%.

“A lot of people across the pond are using this risk score. But there are some problems with it,” according to Dr. Nishimura.

In his view, it “doesn’t make much sense” to include left ventricular outflow tract gradient or left atrial diameter in the risk equation. Nor is unexplained syncope carefully defined. Also, the equation would be improved by incorporation of late gadolinium enhancement on MRI, left ventricular dysfunction, and presence or absence of apical aneurysm as predictive variables. But on the plus side, the European equation treats maximal LV wall thickness as a continuous variable, which is more appropriate than the single 30-mm cutoff used in the ACC/AHA guidelines.

The biggest limitation of the European prognostic score, however, is that it hasn’t yet been validated in an independent patient cohort, Dr. Nishimura said. He noted that when Dr. Maron and coworkers recently applied the European SCD risk equation retrospectively to 1,629 consecutive U.S. patients with HCM, the investigators concluded that the risk equation proved unreliable for prediction of future SCD events. Fifty-nine percent of patients who got an appropriate ICD shock or experienced SCD were misclassified as low risk and hence would not have received an ICD under the European guidelines (Am J Cardiol. 2015 Sep 1;116[5]:757-64).

Nonetheless, because of the limited predictive accuracy of today’s standard methods of assessing SCD risk, Dr. Nishimura considers application of the European risk score to be “reasonable” in HCM patients who don’t have any of the strong indications for an ICD.

“If it comes up with an estimated 5-year risk greater than 6%, I think it’s very reasonable to consider implantation of an ICD,” he said.

Dr. Nishimura observed that in addition to assessing SCD risk, cardiologists have two other separate essential tasks when a patient presents with HCM. One is to screen and counsel the first-degree relatives. The other is to determine whether a left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is present in a symptomatic patient and, if so, to improve symptoms by treating the associated hemodynamic abnormalities medically and if need be by septal ablation or septal myectomy.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Since the 2011 release of the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, several new evidence-based tools have emerged as being helpful in decision making regarding which patients should receive an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death, Dr. Rick A. Nishimura said at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

These three tools – gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging, a novel European risk score calculator, and a new appreciation of the importance of age-related risk – are most useful in the many cases of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) where the cardiologist is on the fence regarding ICD placement because the patient doesn’t clearly meet the conventional major criteria for an ICD, according to Dr. Nishimura, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Nishimura, a member of the writing panel for the current guidelines (Circulation. 2011 Dec 13;124[24]:2761-96), predicted these tools will be incorporated into the next iteration of the HCM guidelines.

Notably absent from Dr. Nishimura’s list of useful tools was genetic testing for assessment of SCD risk in a patient with HCM.

“You should not spend $6,000 to do a genetic study to try to predict who’s at risk for sudden death. It turns out that most mutations are neither inherently benign nor malignant. High-risk mutations come from high-risk families, so you can do just as well by taking a family history,” according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Nishimura explained that the clinical dilemma in trying to evaluate SCD risk in a patient who presents with HCM is that the overall risk is quite low – probably 1% or less per year in the total HCM population – yet HCM is the number-one cause of SCD in younger patients. And it can occur unpredictably years or decades after diagnosis of HCM.

While ICDs are of proven effectiveness in preventing SCD in patients with HCM, reliance solely upon the conventional risk predictors to identify those who should get a device is clearly inadequate. Those criteria have a positive predictive accuracy of less than 15%; in other words, roughly 85% of HCM patients who get an ICD never receive an appropriate, life-saving shock, Dr. Nishimura said.

“We have a lot of work left to do in order to better identify these patients. In our own data from the Mayo Clinic, 20%-25% of patients have inappropriate ICD shocks despite efforts to program the device to prevent such shocks. That’s especially common in younger, active patients with HCM, and when it occurs patients find it absolutely devastating,” according to the cardiologist.

As stated in the current guidelines, the established SCD risk factors that provide a strong indication for an ICD in a patient with HCM are prior documented cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillation, or hemodynamically significant ventricular tachycardia. Additionally, risk factors which, in Dr. Nishimura’s view, probably warrant insertion of an ICD and, at the very least should trigger a physician-patient discussion about the risks and benefits of preventive device therapy, include a family history of HCM-related sudden death in a first-degree relative, massive left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy as defined by a maximum wall thickness of at least 30 mm, and recent unexplained syncope inconsistent with neurocardiogenic origin.

Less potent risk predictors where savvy clinical judgment becomes imperative include nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on 24-hour Holter monitoring, a hypotensive blood pressure response to exercise, and an increased LV wall thickness in a younger patient that doesn’t rise to the 30-mm standard. These are situations where gadolinium-enhanced MRI, consideration of patient age, and the European risk scoring system can help in the decision-making process, he said.

Gadolinium-enhanced MRI: Contrast-enhanced cardiovascular MRI with late gadolinium enhancement has emerged as a reliable marker of the myocyte disarray and interstitial fibrosis which serves as a substrate for ventricular arrhythmias. In a recent study of 1,293 HCM patients followed for a median of 3.3 years, the incidence of SCD events increased progressively with the extent of late gadolinium enhancement. Extensive late gadolinium enhancement, defined as involving at least 15% of LV mass, was associated with a doubled risk of SCD events in patients otherwise considered at low risk (Circulation. 2014 Aug 5;130[6]:484-95).

“This is probably going to become one of the key markers that can help you when you’re on the fence as to whether or not to put in an ICD. We’re getting MRIs with gadolinium now in all of our HCM patients. What matters is not gadolinium enhancement at the insertion of the left ventricle into the septum – a lot of people have that – but diffuse gadolinium enhancement throughout the septum,” Dr. Nishimura said.

Because SCD risk increases linearly with greater maximal LV wall thickness, gadolinium-enhanced MRI is particularly helpful in assessing risk in a younger patient with a maximal LV wall thickness of, say, 26 mm, he added.

Age: A study by led by Dr. Barry J. Maron, the cochair of the 2011 guideline committee and director of the HCM center at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, provides a new understanding that prophylactic ICD implantation is not warranted in patients with HCM who present at age 60 or older. In their study of 428 consecutive patients presenting with HCM at age 60 or above, the investigators found during 5.8 years of follow-up that the incidence of arrhythmic sudden death events was just 0.2% per year (Circulation. 2013 Feb 5;127[5]:585-93).

“They’ve shown that if you look at patients age 60 or above who have HCM, the risk of sudden cardiac death is almost nonexistent. That’s incredibly important to remember. Sudden death is something that’s going to happen in the younger population, under age 30,” Dr. Nishimura emphasized.

European SCD risk prediction tool: This tool was hailed as a major advance in the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines on HCM (Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2733-2779). The tool was incorporated into the guidelines. It is also available as a smartphone app.

The risk prediction tool (Eur Heart J. 2014 Aug 7;35[30]:2010-20) is a complex equation that incorporates seven predictive factors: age, maximal LV wall thickness, left atrial diameter, LV outflow tract gradient, family history of SCD, nonsustained VT, and unexplained syncope. After input on these seven factors, the equation spits out an individual’s estimated 5-year SCD risk. Based on the study of 3,675 consecutive HCM patients with a median 5.7 years of follow-up that was used to develop the risk equation, the current ESC guidelines state that an ICD is not warranted in HCM patients with a 5-year risk below 4%, device implantation should be considered in those whose risk is 4%-6%, and an ICD should be even more strongly considered in patients with a 5-year risk in excess of 6%.

“A lot of people across the pond are using this risk score. But there are some problems with it,” according to Dr. Nishimura.

In his view, it “doesn’t make much sense” to include left ventricular outflow tract gradient or left atrial diameter in the risk equation. Nor is unexplained syncope carefully defined. Also, the equation would be improved by incorporation of late gadolinium enhancement on MRI, left ventricular dysfunction, and presence or absence of apical aneurysm as predictive variables. But on the plus side, the European equation treats maximal LV wall thickness as a continuous variable, which is more appropriate than the single 30-mm cutoff used in the ACC/AHA guidelines.

The biggest limitation of the European prognostic score, however, is that it hasn’t yet been validated in an independent patient cohort, Dr. Nishimura said. He noted that when Dr. Maron and coworkers recently applied the European SCD risk equation retrospectively to 1,629 consecutive U.S. patients with HCM, the investigators concluded that the risk equation proved unreliable for prediction of future SCD events. Fifty-nine percent of patients who got an appropriate ICD shock or experienced SCD were misclassified as low risk and hence would not have received an ICD under the European guidelines (Am J Cardiol. 2015 Sep 1;116[5]:757-64).

Nonetheless, because of the limited predictive accuracy of today’s standard methods of assessing SCD risk, Dr. Nishimura considers application of the European risk score to be “reasonable” in HCM patients who don’t have any of the strong indications for an ICD.

“If it comes up with an estimated 5-year risk greater than 6%, I think it’s very reasonable to consider implantation of an ICD,” he said.

Dr. Nishimura observed that in addition to assessing SCD risk, cardiologists have two other separate essential tasks when a patient presents with HCM. One is to screen and counsel the first-degree relatives. The other is to determine whether a left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is present in a symptomatic patient and, if so, to improve symptoms by treating the associated hemodynamic abnormalities medically and if need be by septal ablation or septal myectomy.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Since the 2011 release of the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, several new evidence-based tools have emerged as being helpful in decision making regarding which patients should receive an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death, Dr. Rick A. Nishimura said at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

These three tools – gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging, a novel European risk score calculator, and a new appreciation of the importance of age-related risk – are most useful in the many cases of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) where the cardiologist is on the fence regarding ICD placement because the patient doesn’t clearly meet the conventional major criteria for an ICD, according to Dr. Nishimura, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Nishimura, a member of the writing panel for the current guidelines (Circulation. 2011 Dec 13;124[24]:2761-96), predicted these tools will be incorporated into the next iteration of the HCM guidelines.

Notably absent from Dr. Nishimura’s list of useful tools was genetic testing for assessment of SCD risk in a patient with HCM.

“You should not spend $6,000 to do a genetic study to try to predict who’s at risk for sudden death. It turns out that most mutations are neither inherently benign nor malignant. High-risk mutations come from high-risk families, so you can do just as well by taking a family history,” according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Nishimura explained that the clinical dilemma in trying to evaluate SCD risk in a patient who presents with HCM is that the overall risk is quite low – probably 1% or less per year in the total HCM population – yet HCM is the number-one cause of SCD in younger patients. And it can occur unpredictably years or decades after diagnosis of HCM.

While ICDs are of proven effectiveness in preventing SCD in patients with HCM, reliance solely upon the conventional risk predictors to identify those who should get a device is clearly inadequate. Those criteria have a positive predictive accuracy of less than 15%; in other words, roughly 85% of HCM patients who get an ICD never receive an appropriate, life-saving shock, Dr. Nishimura said.

“We have a lot of work left to do in order to better identify these patients. In our own data from the Mayo Clinic, 20%-25% of patients have inappropriate ICD shocks despite efforts to program the device to prevent such shocks. That’s especially common in younger, active patients with HCM, and when it occurs patients find it absolutely devastating,” according to the cardiologist.

As stated in the current guidelines, the established SCD risk factors that provide a strong indication for an ICD in a patient with HCM are prior documented cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillation, or hemodynamically significant ventricular tachycardia. Additionally, risk factors which, in Dr. Nishimura’s view, probably warrant insertion of an ICD and, at the very least should trigger a physician-patient discussion about the risks and benefits of preventive device therapy, include a family history of HCM-related sudden death in a first-degree relative, massive left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy as defined by a maximum wall thickness of at least 30 mm, and recent unexplained syncope inconsistent with neurocardiogenic origin.

Less potent risk predictors where savvy clinical judgment becomes imperative include nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on 24-hour Holter monitoring, a hypotensive blood pressure response to exercise, and an increased LV wall thickness in a younger patient that doesn’t rise to the 30-mm standard. These are situations where gadolinium-enhanced MRI, consideration of patient age, and the European risk scoring system can help in the decision-making process, he said.

Gadolinium-enhanced MRI: Contrast-enhanced cardiovascular MRI with late gadolinium enhancement has emerged as a reliable marker of the myocyte disarray and interstitial fibrosis which serves as a substrate for ventricular arrhythmias. In a recent study of 1,293 HCM patients followed for a median of 3.3 years, the incidence of SCD events increased progressively with the extent of late gadolinium enhancement. Extensive late gadolinium enhancement, defined as involving at least 15% of LV mass, was associated with a doubled risk of SCD events in patients otherwise considered at low risk (Circulation. 2014 Aug 5;130[6]:484-95).

“This is probably going to become one of the key markers that can help you when you’re on the fence as to whether or not to put in an ICD. We’re getting MRIs with gadolinium now in all of our HCM patients. What matters is not gadolinium enhancement at the insertion of the left ventricle into the septum – a lot of people have that – but diffuse gadolinium enhancement throughout the septum,” Dr. Nishimura said.

Because SCD risk increases linearly with greater maximal LV wall thickness, gadolinium-enhanced MRI is particularly helpful in assessing risk in a younger patient with a maximal LV wall thickness of, say, 26 mm, he added.

Age: A study by led by Dr. Barry J. Maron, the cochair of the 2011 guideline committee and director of the HCM center at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, provides a new understanding that prophylactic ICD implantation is not warranted in patients with HCM who present at age 60 or older. In their study of 428 consecutive patients presenting with HCM at age 60 or above, the investigators found during 5.8 years of follow-up that the incidence of arrhythmic sudden death events was just 0.2% per year (Circulation. 2013 Feb 5;127[5]:585-93).

“They’ve shown that if you look at patients age 60 or above who have HCM, the risk of sudden cardiac death is almost nonexistent. That’s incredibly important to remember. Sudden death is something that’s going to happen in the younger population, under age 30,” Dr. Nishimura emphasized.

European SCD risk prediction tool: This tool was hailed as a major advance in the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines on HCM (Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2733-2779). The tool was incorporated into the guidelines. It is also available as a smartphone app.

The risk prediction tool (Eur Heart J. 2014 Aug 7;35[30]:2010-20) is a complex equation that incorporates seven predictive factors: age, maximal LV wall thickness, left atrial diameter, LV outflow tract gradient, family history of SCD, nonsustained VT, and unexplained syncope. After input on these seven factors, the equation spits out an individual’s estimated 5-year SCD risk. Based on the study of 3,675 consecutive HCM patients with a median 5.7 years of follow-up that was used to develop the risk equation, the current ESC guidelines state that an ICD is not warranted in HCM patients with a 5-year risk below 4%, device implantation should be considered in those whose risk is 4%-6%, and an ICD should be even more strongly considered in patients with a 5-year risk in excess of 6%.

“A lot of people across the pond are using this risk score. But there are some problems with it,” according to Dr. Nishimura.

In his view, it “doesn’t make much sense” to include left ventricular outflow tract gradient or left atrial diameter in the risk equation. Nor is unexplained syncope carefully defined. Also, the equation would be improved by incorporation of late gadolinium enhancement on MRI, left ventricular dysfunction, and presence or absence of apical aneurysm as predictive variables. But on the plus side, the European equation treats maximal LV wall thickness as a continuous variable, which is more appropriate than the single 30-mm cutoff used in the ACC/AHA guidelines.

The biggest limitation of the European prognostic score, however, is that it hasn’t yet been validated in an independent patient cohort, Dr. Nishimura said. He noted that when Dr. Maron and coworkers recently applied the European SCD risk equation retrospectively to 1,629 consecutive U.S. patients with HCM, the investigators concluded that the risk equation proved unreliable for prediction of future SCD events. Fifty-nine percent of patients who got an appropriate ICD shock or experienced SCD were misclassified as low risk and hence would not have received an ICD under the European guidelines (Am J Cardiol. 2015 Sep 1;116[5]:757-64).

Nonetheless, because of the limited predictive accuracy of today’s standard methods of assessing SCD risk, Dr. Nishimura considers application of the European risk score to be “reasonable” in HCM patients who don’t have any of the strong indications for an ICD.

“If it comes up with an estimated 5-year risk greater than 6%, I think it’s very reasonable to consider implantation of an ICD,” he said.

Dr. Nishimura observed that in addition to assessing SCD risk, cardiologists have two other separate essential tasks when a patient presents with HCM. One is to screen and counsel the first-degree relatives. The other is to determine whether a left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is present in a symptomatic patient and, if so, to improve symptoms by treating the associated hemodynamic abnormalities medically and if need be by septal ablation or septal myectomy.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Finding more transplant hearts but not more donors

Heart transplant volumes in the United States have remained static since the start of the century because of improved trauma prevention and treatment, but that has challenged cardiologists to find enough donor hearts for the growing ranks of advanced heart failure patients. So a multidisciplinary team at the University of Washington in Seattle initiated a quality improvement program that doubled transplant volume without any change in transplant-related deaths by accepting hearts they would have otherwise discarded.

The study came about after the researchers determined that a large number of donor hearts from their own organ procurement program were being sent to other transplant centers. So they gathered a multidisciplinary team of transplant surgeons, cardiologists, and members of the organ procurement program to study ways to improve its center-specific organ utilization rate. The endeavor resulted in an increase in utilization rates from 28% to 49% in a year, a rate that has been sustained through a second year, according to study findings published in the January issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;151:238-43).

“The simple process of systematically reviewing donor turn down events as a group tended to reduce variability [and] increase confidence in expanded criteria donors and resulted in improved donor organ utilization and transplant volumes,” lead author Dr. Jason Smith and colleagues said.

The 30-day and 1-year death rates were similar before and after the quality improvement program started, but the death rates of those on the heart wait list declined from 17.2% to 12%, “which was not statistically significant,” Dr. Smith and coauthors said, “but does show that increasing use of organs that may be outside of the usual pattern has a trend toward improved wait list survival and needs to be considered when assessing donor hearts.”

Because of excellent results of heart transplants in patients with advanced heart failure, a number of investigators have proposed expanding the population of heart donors to include older people, those with higher risk of infectious disease, or with heart disease such as coronary artery disease and left ventricular hypertrophy, Dr. Smith and coauthors said. Their own review found a higher-than-expected rate of donor hearts sent to other centers from the University of Washington organ procurement program.

The multidisciplinary team analyzed the organs the University of Washington surgeons refused and sent to other institutions from July 2012 to June 2013.

For a year after that, the multidisciplinary group did real-time analysis of organ refusal along with quarterly reviews “in a non-confrontational, proactive” setting, as Dr. Smith and his colleagues described it. The group held open discussions on refused organs that were ultimately transplanted elsewhere. “The review process was facilitated to provide a constructive environment to encourage development of best practices and consistency,” the researchers noted. The quality improvement program led to an increase in the unit’s transplant volume despite fewer donor offers.

The researchers acknowledged that donor assessment has been the focus of much controversy. They pointed out that average donor age has increased over the last 20 years from 29 years to 33 years and has since retreated to 31 years, and some programs utilize donors up to their mid-60s. Also, previous studies have advocated for the use of donors who meet the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention high risk behavior of infection as well as some drug abusers because of the low-risk of transmission and emerging evidence affirming the safety of hearts of drug users.

“The individual decision to utilize or discard a donor organ is one of the most challenging aspects of transplant medicine,” Dr. Smith and colleagues said. “It requires balancing donor risks against the exigencies of the recipient.”

Today, the multidisciplinary team evaluates each heart offered for donation and is exploring ways to accept even more donor hearts, even discarded hearts. “This represents a large, untapped pool of potential donor hearts that might add to the net number of transplants performed nationally and not merely redistribute organ usage,” Dr. Smith and colleagues said.

Dr. Smith is a consultant for Thoratec and is a primary site investigator for the EXPAND Trial sponsored by TransMedics. Dr. Todd Dardas is supported by the American College of Cardiology/Daiichi Sankyo Career Development Award. Dr. Jay Pal receives grant support from Tenax. Dr. Wayne Levy is a consultant for HeartWare, Novartis, GE Healthcare, Pharmin, and Biotronik. Dr. Claudius Mahr is a consultant for Thoratec, HeartWare and Abiomed. Dr. Nahush Mokadam is a consultant for Thoratec, HeartWare, Syncardia and St. Jude Medical, and has research grants from Thoratec, HeartWare and Syncardia. The other coauthors had no relationships to disclose.

How the University of Washington researchers brought about such a dramatic increase in donor heart utilization raises a number of questions, Dr. Nicholas Smedira of Cleveland Clinic said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;151:243-4).

“They refer euphemistically to ‘behavioral adaptation’ and ‘frank discussions’ regarding ‘individual and group bias’ as explanations, but understanding exactly how this is accomplished is not easy,” Dr. Smedira said.

Noteworthy is that the researchers used more donors who meet Center for Disease Control and Prevention high risk criteria for infectious disease. However, cardiologists tend to weigh their decision for accepting donor hearts “by the last memorable or distressful experience,” Dr. Smedira said. Hence, many of these donor hearts go unused. At the same time, assessing risk without complete information is challenging, he said.

Besides their thought processes, other factors that influence cardiologists’ decisions on accepting donor hearts include fatigue, scheduling conflicts, reimbursement issues, and outcome metrics. He credited the University of Washington for its “courage” to examine their decision-making process, including exploring biases as well as working “collectively and blamelessly” to support their decisions. “I would encourage more transplant centers to follow a program similar to the University of Washington’s and maybe we will be hearing more yeses and fewer nos,” Dr. Smedira said.

He had no relationships to disclose.

How the University of Washington researchers brought about such a dramatic increase in donor heart utilization raises a number of questions, Dr. Nicholas Smedira of Cleveland Clinic said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;151:243-4).

“They refer euphemistically to ‘behavioral adaptation’ and ‘frank discussions’ regarding ‘individual and group bias’ as explanations, but understanding exactly how this is accomplished is not easy,” Dr. Smedira said.

Noteworthy is that the researchers used more donors who meet Center for Disease Control and Prevention high risk criteria for infectious disease. However, cardiologists tend to weigh their decision for accepting donor hearts “by the last memorable or distressful experience,” Dr. Smedira said. Hence, many of these donor hearts go unused. At the same time, assessing risk without complete information is challenging, he said.

Besides their thought processes, other factors that influence cardiologists’ decisions on accepting donor hearts include fatigue, scheduling conflicts, reimbursement issues, and outcome metrics. He credited the University of Washington for its “courage” to examine their decision-making process, including exploring biases as well as working “collectively and blamelessly” to support their decisions. “I would encourage more transplant centers to follow a program similar to the University of Washington’s and maybe we will be hearing more yeses and fewer nos,” Dr. Smedira said.

He had no relationships to disclose.

How the University of Washington researchers brought about such a dramatic increase in donor heart utilization raises a number of questions, Dr. Nicholas Smedira of Cleveland Clinic said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;151:243-4).

“They refer euphemistically to ‘behavioral adaptation’ and ‘frank discussions’ regarding ‘individual and group bias’ as explanations, but understanding exactly how this is accomplished is not easy,” Dr. Smedira said.

Noteworthy is that the researchers used more donors who meet Center for Disease Control and Prevention high risk criteria for infectious disease. However, cardiologists tend to weigh their decision for accepting donor hearts “by the last memorable or distressful experience,” Dr. Smedira said. Hence, many of these donor hearts go unused. At the same time, assessing risk without complete information is challenging, he said.

Besides their thought processes, other factors that influence cardiologists’ decisions on accepting donor hearts include fatigue, scheduling conflicts, reimbursement issues, and outcome metrics. He credited the University of Washington for its “courage” to examine their decision-making process, including exploring biases as well as working “collectively and blamelessly” to support their decisions. “I would encourage more transplant centers to follow a program similar to the University of Washington’s and maybe we will be hearing more yeses and fewer nos,” Dr. Smedira said.

He had no relationships to disclose.

Heart transplant volumes in the United States have remained static since the start of the century because of improved trauma prevention and treatment, but that has challenged cardiologists to find enough donor hearts for the growing ranks of advanced heart failure patients. So a multidisciplinary team at the University of Washington in Seattle initiated a quality improvement program that doubled transplant volume without any change in transplant-related deaths by accepting hearts they would have otherwise discarded.

The study came about after the researchers determined that a large number of donor hearts from their own organ procurement program were being sent to other transplant centers. So they gathered a multidisciplinary team of transplant surgeons, cardiologists, and members of the organ procurement program to study ways to improve its center-specific organ utilization rate. The endeavor resulted in an increase in utilization rates from 28% to 49% in a year, a rate that has been sustained through a second year, according to study findings published in the January issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;151:238-43).

“The simple process of systematically reviewing donor turn down events as a group tended to reduce variability [and] increase confidence in expanded criteria donors and resulted in improved donor organ utilization and transplant volumes,” lead author Dr. Jason Smith and colleagues said.

The 30-day and 1-year death rates were similar before and after the quality improvement program started, but the death rates of those on the heart wait list declined from 17.2% to 12%, “which was not statistically significant,” Dr. Smith and coauthors said, “but does show that increasing use of organs that may be outside of the usual pattern has a trend toward improved wait list survival and needs to be considered when assessing donor hearts.”

Because of excellent results of heart transplants in patients with advanced heart failure, a number of investigators have proposed expanding the population of heart donors to include older people, those with higher risk of infectious disease, or with heart disease such as coronary artery disease and left ventricular hypertrophy, Dr. Smith and coauthors said. Their own review found a higher-than-expected rate of donor hearts sent to other centers from the University of Washington organ procurement program.

The multidisciplinary team analyzed the organs the University of Washington surgeons refused and sent to other institutions from July 2012 to June 2013.

For a year after that, the multidisciplinary group did real-time analysis of organ refusal along with quarterly reviews “in a non-confrontational, proactive” setting, as Dr. Smith and his colleagues described it. The group held open discussions on refused organs that were ultimately transplanted elsewhere. “The review process was facilitated to provide a constructive environment to encourage development of best practices and consistency,” the researchers noted. The quality improvement program led to an increase in the unit’s transplant volume despite fewer donor offers.

The researchers acknowledged that donor assessment has been the focus of much controversy. They pointed out that average donor age has increased over the last 20 years from 29 years to 33 years and has since retreated to 31 years, and some programs utilize donors up to their mid-60s. Also, previous studies have advocated for the use of donors who meet the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention high risk behavior of infection as well as some drug abusers because of the low-risk of transmission and emerging evidence affirming the safety of hearts of drug users.

“The individual decision to utilize or discard a donor organ is one of the most challenging aspects of transplant medicine,” Dr. Smith and colleagues said. “It requires balancing donor risks against the exigencies of the recipient.”

Today, the multidisciplinary team evaluates each heart offered for donation and is exploring ways to accept even more donor hearts, even discarded hearts. “This represents a large, untapped pool of potential donor hearts that might add to the net number of transplants performed nationally and not merely redistribute organ usage,” Dr. Smith and colleagues said.

Dr. Smith is a consultant for Thoratec and is a primary site investigator for the EXPAND Trial sponsored by TransMedics. Dr. Todd Dardas is supported by the American College of Cardiology/Daiichi Sankyo Career Development Award. Dr. Jay Pal receives grant support from Tenax. Dr. Wayne Levy is a consultant for HeartWare, Novartis, GE Healthcare, Pharmin, and Biotronik. Dr. Claudius Mahr is a consultant for Thoratec, HeartWare and Abiomed. Dr. Nahush Mokadam is a consultant for Thoratec, HeartWare, Syncardia and St. Jude Medical, and has research grants from Thoratec, HeartWare and Syncardia. The other coauthors had no relationships to disclose.

Heart transplant volumes in the United States have remained static since the start of the century because of improved trauma prevention and treatment, but that has challenged cardiologists to find enough donor hearts for the growing ranks of advanced heart failure patients. So a multidisciplinary team at the University of Washington in Seattle initiated a quality improvement program that doubled transplant volume without any change in transplant-related deaths by accepting hearts they would have otherwise discarded.

The study came about after the researchers determined that a large number of donor hearts from their own organ procurement program were being sent to other transplant centers. So they gathered a multidisciplinary team of transplant surgeons, cardiologists, and members of the organ procurement program to study ways to improve its center-specific organ utilization rate. The endeavor resulted in an increase in utilization rates from 28% to 49% in a year, a rate that has been sustained through a second year, according to study findings published in the January issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;151:238-43).

“The simple process of systematically reviewing donor turn down events as a group tended to reduce variability [and] increase confidence in expanded criteria donors and resulted in improved donor organ utilization and transplant volumes,” lead author Dr. Jason Smith and colleagues said.

The 30-day and 1-year death rates were similar before and after the quality improvement program started, but the death rates of those on the heart wait list declined from 17.2% to 12%, “which was not statistically significant,” Dr. Smith and coauthors said, “but does show that increasing use of organs that may be outside of the usual pattern has a trend toward improved wait list survival and needs to be considered when assessing donor hearts.”

Because of excellent results of heart transplants in patients with advanced heart failure, a number of investigators have proposed expanding the population of heart donors to include older people, those with higher risk of infectious disease, or with heart disease such as coronary artery disease and left ventricular hypertrophy, Dr. Smith and coauthors said. Their own review found a higher-than-expected rate of donor hearts sent to other centers from the University of Washington organ procurement program.

The multidisciplinary team analyzed the organs the University of Washington surgeons refused and sent to other institutions from July 2012 to June 2013.

For a year after that, the multidisciplinary group did real-time analysis of organ refusal along with quarterly reviews “in a non-confrontational, proactive” setting, as Dr. Smith and his colleagues described it. The group held open discussions on refused organs that were ultimately transplanted elsewhere. “The review process was facilitated to provide a constructive environment to encourage development of best practices and consistency,” the researchers noted. The quality improvement program led to an increase in the unit’s transplant volume despite fewer donor offers.

The researchers acknowledged that donor assessment has been the focus of much controversy. They pointed out that average donor age has increased over the last 20 years from 29 years to 33 years and has since retreated to 31 years, and some programs utilize donors up to their mid-60s. Also, previous studies have advocated for the use of donors who meet the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention high risk behavior of infection as well as some drug abusers because of the low-risk of transmission and emerging evidence affirming the safety of hearts of drug users.

“The individual decision to utilize or discard a donor organ is one of the most challenging aspects of transplant medicine,” Dr. Smith and colleagues said. “It requires balancing donor risks against the exigencies of the recipient.”

Today, the multidisciplinary team evaluates each heart offered for donation and is exploring ways to accept even more donor hearts, even discarded hearts. “This represents a large, untapped pool of potential donor hearts that might add to the net number of transplants performed nationally and not merely redistribute organ usage,” Dr. Smith and colleagues said.

Dr. Smith is a consultant for Thoratec and is a primary site investigator for the EXPAND Trial sponsored by TransMedics. Dr. Todd Dardas is supported by the American College of Cardiology/Daiichi Sankyo Career Development Award. Dr. Jay Pal receives grant support from Tenax. Dr. Wayne Levy is a consultant for HeartWare, Novartis, GE Healthcare, Pharmin, and Biotronik. Dr. Claudius Mahr is a consultant for Thoratec, HeartWare and Abiomed. Dr. Nahush Mokadam is a consultant for Thoratec, HeartWare, Syncardia and St. Jude Medical, and has research grants from Thoratec, HeartWare and Syncardia. The other coauthors had no relationships to disclose.

Key clinical point: A group approach to systematically review rejected donor organs has led to expanded donor criteria and resulted in improved donor organ utilization and transplant volume.

Major finding: Transplant utilization rate increased from 28% to 49% with no significant change in 30-day survival after implementation of a donor review protocol.

Data source: Retrospective review of 293 total donor heart offers at a single center from July 2012 to June 2013 compared with review of 279 heart offers from July 2013 to June 2014.

Disclosures: Lead author Dr. Jason Smith is a consultant for Thoratec and is a primary site investigator for the EXPAND Trial sponsored by TransMedics. Dr. Todd Dardas is supported by the American College of Cardiology/Daiichi Sankyo Career Development Award. Dr. Jay Pal receives grant support from Tenax. Dr. Wayne Levy is a consultant for HeartWare, Novartis, GE Healthcare, Pharmin, and Biotronik. Dr. Claudius Mahr is a consultant for Thoratec, HeartWare and Abiomed. Dr. Nahush Mokadam is a consultant for Thoratec, HeartWare, Syncardia, and St. Jude Medical, and has research grants from Thoratec, HeartWare and Syncardia. The other coauthors had no relationships to disclose.

Neurosurgeon memoir illuminates the journey through cancer treatment and acceptance of mortality

Dr. Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon who had just completed his residency at the Stanford (Calif.) University, died of metastatic lung cancer last year, but he left a memoir of his experiences as a physician, a patient, and a dying man that was published on Jan. 12. His book, “When Breath Becomes Air” (New York: Random House, 2016), recounts the many years of working to exhaustion and deferring of life experiences and pleasures that are necessary to complete medical training.

In a review of the book, Janet Maslin wrote, “One of the most poignant things about Dr. Kalanithi’s story is that he had postponed learning how to live while pursuing his career in neurosurgery. By the time he was ready to enjoy a life outside the operating room, what he needed to learn was how to die.”

Dr. Kalanithi reflected on the profound grief and sense of loss that comes with a diagnosis that he knew meant imminent death. The memoir also reveals his search for meaning and joy, and finally, his acceptance of mortality. He opted for palliative care and his memoir, along with the epilogue written by his wife, Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, gives insight into the value of the palliative path to patients and their families in dire medical crises.

Dr. Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon who had just completed his residency at the Stanford (Calif.) University, died of metastatic lung cancer last year, but he left a memoir of his experiences as a physician, a patient, and a dying man that was published on Jan. 12. His book, “When Breath Becomes Air” (New York: Random House, 2016), recounts the many years of working to exhaustion and deferring of life experiences and pleasures that are necessary to complete medical training.

In a review of the book, Janet Maslin wrote, “One of the most poignant things about Dr. Kalanithi’s story is that he had postponed learning how to live while pursuing his career in neurosurgery. By the time he was ready to enjoy a life outside the operating room, what he needed to learn was how to die.”

Dr. Kalanithi reflected on the profound grief and sense of loss that comes with a diagnosis that he knew meant imminent death. The memoir also reveals his search for meaning and joy, and finally, his acceptance of mortality. He opted for palliative care and his memoir, along with the epilogue written by his wife, Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, gives insight into the value of the palliative path to patients and their families in dire medical crises.

Dr. Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon who had just completed his residency at the Stanford (Calif.) University, died of metastatic lung cancer last year, but he left a memoir of his experiences as a physician, a patient, and a dying man that was published on Jan. 12. His book, “When Breath Becomes Air” (New York: Random House, 2016), recounts the many years of working to exhaustion and deferring of life experiences and pleasures that are necessary to complete medical training.

In a review of the book, Janet Maslin wrote, “One of the most poignant things about Dr. Kalanithi’s story is that he had postponed learning how to live while pursuing his career in neurosurgery. By the time he was ready to enjoy a life outside the operating room, what he needed to learn was how to die.”

Dr. Kalanithi reflected on the profound grief and sense of loss that comes with a diagnosis that he knew meant imminent death. The memoir also reveals his search for meaning and joy, and finally, his acceptance of mortality. He opted for palliative care and his memoir, along with the epilogue written by his wife, Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, gives insight into the value of the palliative path to patients and their families in dire medical crises.

David Bowie’s death inspires blog on palliative care

The death of David Bowie, iconic musician and artist, on Jan. 10 inspired palliative care specialist Dr. Mark Taubert to write a blog about end-of-life scenarios and the importance of advance care planning. The blog, which begins by thanking Mr. Bowie for his many artistic contributions, continues by suggesting that his planned death at home will inspire many people in similar health crises to consider palliative care. The palliative care conversation between a doctor and a patient facing death can be challenging but can lead to what Dr. Taubert called “a good death” at home with symptoms managed and loved ones nearby. Mr. Bowie’s son, Duncan Jones, tweeted a link to the blog in the days after his father’s death.

Dr. Taubert found himself speaking with a patient who was facing probable death in the near future, and both doctor and patient found inspiration in Mr. Bowie’s final music project and his death at home with his family. Dr. Taubert and his patient were able to have the conversation about palliative care at end-of-life in part because they were both impressed with what Mr. Bowie was able to achieve in his last months. “Your story became a way for us to communicate very openly about death, something many doctors and nurses struggle to introduce as a topic of conversation,” he wrote.

Dr. Taubert of the Velindre NHS Trust in Cardiff, Wales, noted that, although palliative care is a highly developed skill with many resources to help patients at the end of life, “this essential part of training is not always available for junior healthcare professionals, including doctors and nurses, and is sometimes overlooked or under-prioritized by those who plan their education. I think if you [David Bowie] were ever to return (as Lazarus did), you would be a firm advocate for good palliative care training being available everywhere.”

The death of David Bowie, iconic musician and artist, on Jan. 10 inspired palliative care specialist Dr. Mark Taubert to write a blog about end-of-life scenarios and the importance of advance care planning. The blog, which begins by thanking Mr. Bowie for his many artistic contributions, continues by suggesting that his planned death at home will inspire many people in similar health crises to consider palliative care. The palliative care conversation between a doctor and a patient facing death can be challenging but can lead to what Dr. Taubert called “a good death” at home with symptoms managed and loved ones nearby. Mr. Bowie’s son, Duncan Jones, tweeted a link to the blog in the days after his father’s death.

Dr. Taubert found himself speaking with a patient who was facing probable death in the near future, and both doctor and patient found inspiration in Mr. Bowie’s final music project and his death at home with his family. Dr. Taubert and his patient were able to have the conversation about palliative care at end-of-life in part because they were both impressed with what Mr. Bowie was able to achieve in his last months. “Your story became a way for us to communicate very openly about death, something many doctors and nurses struggle to introduce as a topic of conversation,” he wrote.

Dr. Taubert of the Velindre NHS Trust in Cardiff, Wales, noted that, although palliative care is a highly developed skill with many resources to help patients at the end of life, “this essential part of training is not always available for junior healthcare professionals, including doctors and nurses, and is sometimes overlooked or under-prioritized by those who plan their education. I think if you [David Bowie] were ever to return (as Lazarus did), you would be a firm advocate for good palliative care training being available everywhere.”

The death of David Bowie, iconic musician and artist, on Jan. 10 inspired palliative care specialist Dr. Mark Taubert to write a blog about end-of-life scenarios and the importance of advance care planning. The blog, which begins by thanking Mr. Bowie for his many artistic contributions, continues by suggesting that his planned death at home will inspire many people in similar health crises to consider palliative care. The palliative care conversation between a doctor and a patient facing death can be challenging but can lead to what Dr. Taubert called “a good death” at home with symptoms managed and loved ones nearby. Mr. Bowie’s son, Duncan Jones, tweeted a link to the blog in the days after his father’s death.

Dr. Taubert found himself speaking with a patient who was facing probable death in the near future, and both doctor and patient found inspiration in Mr. Bowie’s final music project and his death at home with his family. Dr. Taubert and his patient were able to have the conversation about palliative care at end-of-life in part because they were both impressed with what Mr. Bowie was able to achieve in his last months. “Your story became a way for us to communicate very openly about death, something many doctors and nurses struggle to introduce as a topic of conversation,” he wrote.

Dr. Taubert of the Velindre NHS Trust in Cardiff, Wales, noted that, although palliative care is a highly developed skill with many resources to help patients at the end of life, “this essential part of training is not always available for junior healthcare professionals, including doctors and nurses, and is sometimes overlooked or under-prioritized by those who plan their education. I think if you [David Bowie] were ever to return (as Lazarus did), you would be a firm advocate for good palliative care training being available everywhere.”

Families perceive few benefits from aggressive end-of-life care

Bereaved families were substantially more satisfied with end-of-life cancer care when patients did not die in hospital, received more than 3 days of hospice care, and did not enter the ICU within 30 days of dying, according to a multicenter, prospective study published online Jan. 19 in JAMA.

The analysis is one of the first of its type to assess these end-of-life care indicators, said Dr. Alexi Wright of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates. The findings could affect health policy as electronic health records expand under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, they said.

End-of-life cancer care has become increasingly aggressive, belying evidence that this approach does not improve patient outcomes, quality of life, or caregiver bereavement. To explore alternatives, the researchers analyzed 1,146 interviews of family members of Medicare patients who died of lung or colorectal cancer by 2011. Their data source was the multiregional, prospective, observational Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study (JAMA 2016;315:284-92).

Family members described end-of-life care as “excellent” 59% of the time when hospice care lasted more 3 days, but 43% of the time otherwise (95% confidence interval for adjusted difference, 11% to 22%). Notably, 73% of patients who received more than 3 days of hospice care died in their preferred location, compared with 40% of patients who received less or no hospice care. Care was rated as excellent 52% of the time when ICU admission was avoided within 30 days of death, and 57% of the time when patients died outside the hospital, compared with 45% and 42% of the time otherwise.

The results support “advance care planning consistent with the preferences of patients,” said the investigators. They recommended more extensive counseling of cancer patients and families, earlier palliative care referrals, and an audit and feedback system to monitor the use of aggressive end-of-life care.

The National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium funded the study. One coinvestigator reported financial relationships with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute on Aging, Retirement Research Retirement Foundation, California Healthcare Foundation, Commonwealth Fund, West Health Institute, University of Wisconsin, and UpToDate.com. Senior author Dr. Mary Landrum, also of Harvard Medical School, reported grant funding from Pfizer and personal fees from McKinsey and Company and Greylock McKinnon Associates. The other authors had no disclosures.

Bereaved families were substantially more satisfied with end-of-life cancer care when patients did not die in hospital, received more than 3 days of hospice care, and did not enter the ICU within 30 days of dying, according to a multicenter, prospective study published online Jan. 19 in JAMA.

The analysis is one of the first of its type to assess these end-of-life care indicators, said Dr. Alexi Wright of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates. The findings could affect health policy as electronic health records expand under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, they said.

End-of-life cancer care has become increasingly aggressive, belying evidence that this approach does not improve patient outcomes, quality of life, or caregiver bereavement. To explore alternatives, the researchers analyzed 1,146 interviews of family members of Medicare patients who died of lung or colorectal cancer by 2011. Their data source was the multiregional, prospective, observational Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study (JAMA 2016;315:284-92).

Family members described end-of-life care as “excellent” 59% of the time when hospice care lasted more 3 days, but 43% of the time otherwise (95% confidence interval for adjusted difference, 11% to 22%). Notably, 73% of patients who received more than 3 days of hospice care died in their preferred location, compared with 40% of patients who received less or no hospice care. Care was rated as excellent 52% of the time when ICU admission was avoided within 30 days of death, and 57% of the time when patients died outside the hospital, compared with 45% and 42% of the time otherwise.

The results support “advance care planning consistent with the preferences of patients,” said the investigators. They recommended more extensive counseling of cancer patients and families, earlier palliative care referrals, and an audit and feedback system to monitor the use of aggressive end-of-life care.

The National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium funded the study. One coinvestigator reported financial relationships with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute on Aging, Retirement Research Retirement Foundation, California Healthcare Foundation, Commonwealth Fund, West Health Institute, University of Wisconsin, and UpToDate.com. Senior author Dr. Mary Landrum, also of Harvard Medical School, reported grant funding from Pfizer and personal fees from McKinsey and Company and Greylock McKinnon Associates. The other authors had no disclosures.

Bereaved families were substantially more satisfied with end-of-life cancer care when patients did not die in hospital, received more than 3 days of hospice care, and did not enter the ICU within 30 days of dying, according to a multicenter, prospective study published online Jan. 19 in JAMA.

The analysis is one of the first of its type to assess these end-of-life care indicators, said Dr. Alexi Wright of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates. The findings could affect health policy as electronic health records expand under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, they said.

End-of-life cancer care has become increasingly aggressive, belying evidence that this approach does not improve patient outcomes, quality of life, or caregiver bereavement. To explore alternatives, the researchers analyzed 1,146 interviews of family members of Medicare patients who died of lung or colorectal cancer by 2011. Their data source was the multiregional, prospective, observational Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study (JAMA 2016;315:284-92).

Family members described end-of-life care as “excellent” 59% of the time when hospice care lasted more 3 days, but 43% of the time otherwise (95% confidence interval for adjusted difference, 11% to 22%). Notably, 73% of patients who received more than 3 days of hospice care died in their preferred location, compared with 40% of patients who received less or no hospice care. Care was rated as excellent 52% of the time when ICU admission was avoided within 30 days of death, and 57% of the time when patients died outside the hospital, compared with 45% and 42% of the time otherwise.