User login

ESC: CERTITUDE casts doubt on defibrillator benefit in CRT

LONDON – Heart failure patients who are candidates for cardiac resynchronization therapy in a routine clinical practice setting will likely not benefit from the addition of a defibrillator to a pacemaker, according to results of the CERTITUDE cohort study.

In CERTITUDE, most of the deaths in patients fitted with a cardiac resynchronization therapy–pacemaker (CRT-P) device were predominantly from causes other than sudden cardiac death (SCD), which is the main rationale for using a CRT-defibrillator (CRT-D) device, said lead investigator Jean-Yves Le Heuzey at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“Our results should not be interpreted as a general lack of benefit from CRT-D vs. CRT-P or vice versa. Rather we demonstrate that given currently selected CRT-P patients in the French population, addition of a defibrillator may not significantly add to survival.” Therefore, patients who may be eligible for CRT should not “automatically” be considered as requiring a CRT-D, suggested Dr. Le Heuzey and his coinvestigators in an article that was published online at the time of the study’s presentation (Eur Heart J. 2015 Sep 1. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv455).

Current ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy “leave flexibility for the physician” on the use of CRT-P and CRT-D” because there was no evidence of a superior effect of the latter over CRT alone, said Dr. Le Heuzey of René Descartes University in Paris at the meeting. A randomized, controlled trial would be the only way to determine this, but such a trial is unlikely to ever be conducted, he noted.

Despite the lack of evidence, however, CRT-D is widely used, more so in the United States than in Europe, Dr. Le Heuzey observed, where more than 90% of patients needing CRT would likely have a CRT-D rather than a CRT-P device implanted.

The aims of the CERTITUDE cohort study were to look at the extent to which CRT-P patients differ from CRT-D patients in a real-life setting, and to also see if there were patients in the CRT-P group that might have benefited from CRT-D.

The prospective, observational study involved 1,705 patients who were recruited at 41 centers throughout France over a 2-year period starting in January 2008. Of these, 31% were fitted with a CRT-P device and 69% with a CRT-D.

Results showed that patients who had a CRT-P versus a CRT-D implanted were significantly older, more often female, and more symptomatic. They were also significantly less likely to have coronary artery disease, more likely to have wider QRS intervals and to have atrial fibrillation, and more often had at least two comorbidities.

Analysis of the causes of death was performed at 2 years’ follow-up, which Dr. Le Heuzey conceded was a short period of time. At this point, 267 of 1,611 patients with complete follow-up data had died, giving an overall mortality rate of 8.4% per 100 patient-years for the entire cohort.

The crude mortality rate was found to be higher among CRT-P than CRT-D patients, at 13.1% versus 6.5% per 100 patient-years (relative risk, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 1.56-2.58; P less than .0001). But when the cause of death was examined more closely, there was no significant difference in the number of SCDs between the groups (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.71-3.46; P = .42) and no significant difference when a specific cause of death analysis was performed.

The main reasons for the almost doubled risk of death in the CRT-P group was an increase in non-SCD cardiovascular mortality, mainly progressive heart failure (RR, 0.27; 95% CI, 1.62-3.18) and other cardiovascular causes (RR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.29-15.03), Dr. Le Heuzey and associates noted in the article.

“Overall, 95% of the excess mortality among CRT-P recipients was not related to SCD,” they wrote, noting that this “suggests that the presence of a back-up defibrillator would probably not have been beneficial in terms of improving survival for these patients.”

So where does this leave clinicians? Dr. Le Heuzey referred to Table 17 in the European guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2281-2329) with guidance on factors favoring CRT-P or CRT-D. For instance, CRT-P might be favorable in a patient with advanced heart failure or one with severe renal insufficiency or on dialysis. Other major comorbidities or frailty or cachexia might veer a decision towards CRT without a defibrillator. On the other hand, factors favoring CRT-D include a life expectancy of more than 1 year; stable, moderate (New York Heart Association class II) disease; or low to moderate–risk ischemic heart disease, with a lack of comorbidities.

CERTITUDE was funded by grants from the French Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) and from the French Cardiology Society. The latter received specific grants from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Saint Jude Medical, and Sorin in order to perform the study. Dr. Le Heuzey disclosed receiving fees for participation in advisory boards and conferences from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Correvio, Daiichi-Sankyo, Meda, Sanofi, and Servier.

LONDON – Heart failure patients who are candidates for cardiac resynchronization therapy in a routine clinical practice setting will likely not benefit from the addition of a defibrillator to a pacemaker, according to results of the CERTITUDE cohort study.

In CERTITUDE, most of the deaths in patients fitted with a cardiac resynchronization therapy–pacemaker (CRT-P) device were predominantly from causes other than sudden cardiac death (SCD), which is the main rationale for using a CRT-defibrillator (CRT-D) device, said lead investigator Jean-Yves Le Heuzey at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“Our results should not be interpreted as a general lack of benefit from CRT-D vs. CRT-P or vice versa. Rather we demonstrate that given currently selected CRT-P patients in the French population, addition of a defibrillator may not significantly add to survival.” Therefore, patients who may be eligible for CRT should not “automatically” be considered as requiring a CRT-D, suggested Dr. Le Heuzey and his coinvestigators in an article that was published online at the time of the study’s presentation (Eur Heart J. 2015 Sep 1. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv455).

Current ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy “leave flexibility for the physician” on the use of CRT-P and CRT-D” because there was no evidence of a superior effect of the latter over CRT alone, said Dr. Le Heuzey of René Descartes University in Paris at the meeting. A randomized, controlled trial would be the only way to determine this, but such a trial is unlikely to ever be conducted, he noted.

Despite the lack of evidence, however, CRT-D is widely used, more so in the United States than in Europe, Dr. Le Heuzey observed, where more than 90% of patients needing CRT would likely have a CRT-D rather than a CRT-P device implanted.

The aims of the CERTITUDE cohort study were to look at the extent to which CRT-P patients differ from CRT-D patients in a real-life setting, and to also see if there were patients in the CRT-P group that might have benefited from CRT-D.

The prospective, observational study involved 1,705 patients who were recruited at 41 centers throughout France over a 2-year period starting in January 2008. Of these, 31% were fitted with a CRT-P device and 69% with a CRT-D.

Results showed that patients who had a CRT-P versus a CRT-D implanted were significantly older, more often female, and more symptomatic. They were also significantly less likely to have coronary artery disease, more likely to have wider QRS intervals and to have atrial fibrillation, and more often had at least two comorbidities.

Analysis of the causes of death was performed at 2 years’ follow-up, which Dr. Le Heuzey conceded was a short period of time. At this point, 267 of 1,611 patients with complete follow-up data had died, giving an overall mortality rate of 8.4% per 100 patient-years for the entire cohort.

The crude mortality rate was found to be higher among CRT-P than CRT-D patients, at 13.1% versus 6.5% per 100 patient-years (relative risk, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 1.56-2.58; P less than .0001). But when the cause of death was examined more closely, there was no significant difference in the number of SCDs between the groups (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.71-3.46; P = .42) and no significant difference when a specific cause of death analysis was performed.

The main reasons for the almost doubled risk of death in the CRT-P group was an increase in non-SCD cardiovascular mortality, mainly progressive heart failure (RR, 0.27; 95% CI, 1.62-3.18) and other cardiovascular causes (RR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.29-15.03), Dr. Le Heuzey and associates noted in the article.

“Overall, 95% of the excess mortality among CRT-P recipients was not related to SCD,” they wrote, noting that this “suggests that the presence of a back-up defibrillator would probably not have been beneficial in terms of improving survival for these patients.”

So where does this leave clinicians? Dr. Le Heuzey referred to Table 17 in the European guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2281-2329) with guidance on factors favoring CRT-P or CRT-D. For instance, CRT-P might be favorable in a patient with advanced heart failure or one with severe renal insufficiency or on dialysis. Other major comorbidities or frailty or cachexia might veer a decision towards CRT without a defibrillator. On the other hand, factors favoring CRT-D include a life expectancy of more than 1 year; stable, moderate (New York Heart Association class II) disease; or low to moderate–risk ischemic heart disease, with a lack of comorbidities.

CERTITUDE was funded by grants from the French Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) and from the French Cardiology Society. The latter received specific grants from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Saint Jude Medical, and Sorin in order to perform the study. Dr. Le Heuzey disclosed receiving fees for participation in advisory boards and conferences from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Correvio, Daiichi-Sankyo, Meda, Sanofi, and Servier.

LONDON – Heart failure patients who are candidates for cardiac resynchronization therapy in a routine clinical practice setting will likely not benefit from the addition of a defibrillator to a pacemaker, according to results of the CERTITUDE cohort study.

In CERTITUDE, most of the deaths in patients fitted with a cardiac resynchronization therapy–pacemaker (CRT-P) device were predominantly from causes other than sudden cardiac death (SCD), which is the main rationale for using a CRT-defibrillator (CRT-D) device, said lead investigator Jean-Yves Le Heuzey at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“Our results should not be interpreted as a general lack of benefit from CRT-D vs. CRT-P or vice versa. Rather we demonstrate that given currently selected CRT-P patients in the French population, addition of a defibrillator may not significantly add to survival.” Therefore, patients who may be eligible for CRT should not “automatically” be considered as requiring a CRT-D, suggested Dr. Le Heuzey and his coinvestigators in an article that was published online at the time of the study’s presentation (Eur Heart J. 2015 Sep 1. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv455).

Current ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy “leave flexibility for the physician” on the use of CRT-P and CRT-D” because there was no evidence of a superior effect of the latter over CRT alone, said Dr. Le Heuzey of René Descartes University in Paris at the meeting. A randomized, controlled trial would be the only way to determine this, but such a trial is unlikely to ever be conducted, he noted.

Despite the lack of evidence, however, CRT-D is widely used, more so in the United States than in Europe, Dr. Le Heuzey observed, where more than 90% of patients needing CRT would likely have a CRT-D rather than a CRT-P device implanted.

The aims of the CERTITUDE cohort study were to look at the extent to which CRT-P patients differ from CRT-D patients in a real-life setting, and to also see if there were patients in the CRT-P group that might have benefited from CRT-D.

The prospective, observational study involved 1,705 patients who were recruited at 41 centers throughout France over a 2-year period starting in January 2008. Of these, 31% were fitted with a CRT-P device and 69% with a CRT-D.

Results showed that patients who had a CRT-P versus a CRT-D implanted were significantly older, more often female, and more symptomatic. They were also significantly less likely to have coronary artery disease, more likely to have wider QRS intervals and to have atrial fibrillation, and more often had at least two comorbidities.

Analysis of the causes of death was performed at 2 years’ follow-up, which Dr. Le Heuzey conceded was a short period of time. At this point, 267 of 1,611 patients with complete follow-up data had died, giving an overall mortality rate of 8.4% per 100 patient-years for the entire cohort.

The crude mortality rate was found to be higher among CRT-P than CRT-D patients, at 13.1% versus 6.5% per 100 patient-years (relative risk, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 1.56-2.58; P less than .0001). But when the cause of death was examined more closely, there was no significant difference in the number of SCDs between the groups (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.71-3.46; P = .42) and no significant difference when a specific cause of death analysis was performed.

The main reasons for the almost doubled risk of death in the CRT-P group was an increase in non-SCD cardiovascular mortality, mainly progressive heart failure (RR, 0.27; 95% CI, 1.62-3.18) and other cardiovascular causes (RR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.29-15.03), Dr. Le Heuzey and associates noted in the article.

“Overall, 95% of the excess mortality among CRT-P recipients was not related to SCD,” they wrote, noting that this “suggests that the presence of a back-up defibrillator would probably not have been beneficial in terms of improving survival for these patients.”

So where does this leave clinicians? Dr. Le Heuzey referred to Table 17 in the European guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2281-2329) with guidance on factors favoring CRT-P or CRT-D. For instance, CRT-P might be favorable in a patient with advanced heart failure or one with severe renal insufficiency or on dialysis. Other major comorbidities or frailty or cachexia might veer a decision towards CRT without a defibrillator. On the other hand, factors favoring CRT-D include a life expectancy of more than 1 year; stable, moderate (New York Heart Association class II) disease; or low to moderate–risk ischemic heart disease, with a lack of comorbidities.

CERTITUDE was funded by grants from the French Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) and from the French Cardiology Society. The latter received specific grants from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Saint Jude Medical, and Sorin in order to perform the study. Dr. Le Heuzey disclosed receiving fees for participation in advisory boards and conferences from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Correvio, Daiichi-Sankyo, Meda, Sanofi, and Servier.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point:There appears to be no survival benefit of cardiac resynchronization therapy with a defibrillator CRT-D over a pacemaker (CRT-P).

Major finding: Although there was a higher death rate among CRT-P recipients, 95% of the excess mortality, compared with CRT-D recipients, was not related to sudden cardiac death.

Data source: The prospective, observational CERTITUDE cohort study in 1,705 French patients fitted with a CRT-P or CRT-D.

Disclosures: CERTITUDE was funded by grants from the French Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) and from the French Cardiology Society. The latter received specific grants from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, and Sorin in order to perform the study. Dr. Le Heuzey disclosed receiving fees for participation in advisory boards and conferences from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Correvio, Daiichi-Sankyo, Meda, Sanofi, and Servier.

VIDEO: Adverse ventilation effect means rethinking Cheyne-Stokes respiration

LONDON – The management of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction needs to be reconsidered following the troubling outcome of a major trial that tested adaptive servo-ventilation as treatment for this symptom, Dr. Lars Køber commented during an interview at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Cheyne-Stokes respiration, a form of central sleep apnea, differs from obstructive sleep apnea in that heart failure patients do not seem to derive symptomatic benefit from adaptive servo-ventilation treatment, but “physicians have thought they could treat this sleep apnea [with ventilation] and it would change prognosis,” said Dr. Køber. “Treatment of sleep apnea is possible, so physicians had started doing it.” But instead of helping patients, the trial results strongly suggested that patients were harmed by treatment, which was significantly linked with increased rates of both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506459).

In our video interview, Dr. Køber, professor of cardiology at Rigshospitalet and the University of Copenhagen, discusses the results and what the findings imply for future treatment.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LONDON – The management of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction needs to be reconsidered following the troubling outcome of a major trial that tested adaptive servo-ventilation as treatment for this symptom, Dr. Lars Køber commented during an interview at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Cheyne-Stokes respiration, a form of central sleep apnea, differs from obstructive sleep apnea in that heart failure patients do not seem to derive symptomatic benefit from adaptive servo-ventilation treatment, but “physicians have thought they could treat this sleep apnea [with ventilation] and it would change prognosis,” said Dr. Køber. “Treatment of sleep apnea is possible, so physicians had started doing it.” But instead of helping patients, the trial results strongly suggested that patients were harmed by treatment, which was significantly linked with increased rates of both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506459).

In our video interview, Dr. Køber, professor of cardiology at Rigshospitalet and the University of Copenhagen, discusses the results and what the findings imply for future treatment.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LONDON – The management of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction needs to be reconsidered following the troubling outcome of a major trial that tested adaptive servo-ventilation as treatment for this symptom, Dr. Lars Køber commented during an interview at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Cheyne-Stokes respiration, a form of central sleep apnea, differs from obstructive sleep apnea in that heart failure patients do not seem to derive symptomatic benefit from adaptive servo-ventilation treatment, but “physicians have thought they could treat this sleep apnea [with ventilation] and it would change prognosis,” said Dr. Køber. “Treatment of sleep apnea is possible, so physicians had started doing it.” But instead of helping patients, the trial results strongly suggested that patients were harmed by treatment, which was significantly linked with increased rates of both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506459).

In our video interview, Dr. Køber, professor of cardiology at Rigshospitalet and the University of Copenhagen, discusses the results and what the findings imply for future treatment.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2015

Heart failure’s surprises keep coming

Heart failure has historically been one of the most poorly understood and hard to treat cardiovascular diseases, and many reports at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in London hammered home how many mysteries remain about heart failure and how many tricks it still keeps up its sleeves.

Probably the most high-profile example was the stunning result of the SERVE-HF trial, reported as a hot-line talk and published concurrently (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506459). The trial randomized more than 1,300 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and central sleep apnea presenting as Cheyne-Stokes respiration to nocturnal treatment with adaptive servo-ventilation. The idea was simple: These heart failure patients have trouble breathing while asleep, so help them with a ventilator.

“We had a technology that could alleviate central sleep apnea, and we just wanted to prove how large the benefit was,” said Dr. Martin R. Cowie, the trial’s lead investigator. But in results that “surprised us completely,” said Dr. Cowie, ventilation not only failed to produce a significant benefit for the trial’s primary, combined endpoint, it also showed a significant deleterious effect for the secondary endpoints of death by any cause and for cardiovascular death. In short, treating these patients with a ventilator was killing them. “We don’t understand what’s going on here,” Dr. Cowie said. He characterized the outcome as a “game changer” because many physicians had already begun using this form of ventilation on patients as it made such perfect sense.

“It’s unbelievable. We thought it was a slam dunk,” commented Dr. Frank Rushitka when he summed up the congress’ heart failure program at the end of the meeting.

Dr. Athena Poppas, who delivered the invited commentary on SERVE-HF, highlighted the “complexity” of heart failure and how “poorly understood” it is. “We’ve seen so many times where we saw something that we thought was bad [and treated] without fully understanding the mechanisms,” she said in an interview.

A great example was the misbegotten flirtation a couple of decades ago with inotropic therapy. It was another no-brainer: drugs that stimulate the heart’s pumping function will help patients with impaired cardiac output. But then trial results showed that chronic inotropic treatment actually hastened patients’ demise. “Patients felt better but they died faster,” Dr. Poppas noted.

Heart failure’s surprises keep coming. During the congress, heart failure expert Dr. Marriel L. Jessup said, “We used to think the reason why patients with acute heart failure were diuretic resistant was because of poor cardiac output. Now we know that they have a lot of venous congestion that impacts the kidneys and liver.”

Another researcher, Dr. John C. Burnett Jr. added, “It’s not just plumbing” that harms the kidneys and liver, but also “deleterious molecules” released because of venous congestion that causes organ damage. The identity of those molecules is only now being explored. And recognition that liver damage is an important part of the heart failure syndrome occurred only recently.

Heart failure continues to reveal its mysteries slowly and reluctantly. Clinicians who believe they know all they need about how to safely and effectively treat it are fooling themselves and run the risk of hurting their patients.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Heart failure has historically been one of the most poorly understood and hard to treat cardiovascular diseases, and many reports at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in London hammered home how many mysteries remain about heart failure and how many tricks it still keeps up its sleeves.

Probably the most high-profile example was the stunning result of the SERVE-HF trial, reported as a hot-line talk and published concurrently (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506459). The trial randomized more than 1,300 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and central sleep apnea presenting as Cheyne-Stokes respiration to nocturnal treatment with adaptive servo-ventilation. The idea was simple: These heart failure patients have trouble breathing while asleep, so help them with a ventilator.

“We had a technology that could alleviate central sleep apnea, and we just wanted to prove how large the benefit was,” said Dr. Martin R. Cowie, the trial’s lead investigator. But in results that “surprised us completely,” said Dr. Cowie, ventilation not only failed to produce a significant benefit for the trial’s primary, combined endpoint, it also showed a significant deleterious effect for the secondary endpoints of death by any cause and for cardiovascular death. In short, treating these patients with a ventilator was killing them. “We don’t understand what’s going on here,” Dr. Cowie said. He characterized the outcome as a “game changer” because many physicians had already begun using this form of ventilation on patients as it made such perfect sense.

“It’s unbelievable. We thought it was a slam dunk,” commented Dr. Frank Rushitka when he summed up the congress’ heart failure program at the end of the meeting.

Dr. Athena Poppas, who delivered the invited commentary on SERVE-HF, highlighted the “complexity” of heart failure and how “poorly understood” it is. “We’ve seen so many times where we saw something that we thought was bad [and treated] without fully understanding the mechanisms,” she said in an interview.

A great example was the misbegotten flirtation a couple of decades ago with inotropic therapy. It was another no-brainer: drugs that stimulate the heart’s pumping function will help patients with impaired cardiac output. But then trial results showed that chronic inotropic treatment actually hastened patients’ demise. “Patients felt better but they died faster,” Dr. Poppas noted.

Heart failure’s surprises keep coming. During the congress, heart failure expert Dr. Marriel L. Jessup said, “We used to think the reason why patients with acute heart failure were diuretic resistant was because of poor cardiac output. Now we know that they have a lot of venous congestion that impacts the kidneys and liver.”

Another researcher, Dr. John C. Burnett Jr. added, “It’s not just plumbing” that harms the kidneys and liver, but also “deleterious molecules” released because of venous congestion that causes organ damage. The identity of those molecules is only now being explored. And recognition that liver damage is an important part of the heart failure syndrome occurred only recently.

Heart failure continues to reveal its mysteries slowly and reluctantly. Clinicians who believe they know all they need about how to safely and effectively treat it are fooling themselves and run the risk of hurting their patients.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Heart failure has historically been one of the most poorly understood and hard to treat cardiovascular diseases, and many reports at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in London hammered home how many mysteries remain about heart failure and how many tricks it still keeps up its sleeves.

Probably the most high-profile example was the stunning result of the SERVE-HF trial, reported as a hot-line talk and published concurrently (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506459). The trial randomized more than 1,300 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and central sleep apnea presenting as Cheyne-Stokes respiration to nocturnal treatment with adaptive servo-ventilation. The idea was simple: These heart failure patients have trouble breathing while asleep, so help them with a ventilator.

“We had a technology that could alleviate central sleep apnea, and we just wanted to prove how large the benefit was,” said Dr. Martin R. Cowie, the trial’s lead investigator. But in results that “surprised us completely,” said Dr. Cowie, ventilation not only failed to produce a significant benefit for the trial’s primary, combined endpoint, it also showed a significant deleterious effect for the secondary endpoints of death by any cause and for cardiovascular death. In short, treating these patients with a ventilator was killing them. “We don’t understand what’s going on here,” Dr. Cowie said. He characterized the outcome as a “game changer” because many physicians had already begun using this form of ventilation on patients as it made such perfect sense.

“It’s unbelievable. We thought it was a slam dunk,” commented Dr. Frank Rushitka when he summed up the congress’ heart failure program at the end of the meeting.

Dr. Athena Poppas, who delivered the invited commentary on SERVE-HF, highlighted the “complexity” of heart failure and how “poorly understood” it is. “We’ve seen so many times where we saw something that we thought was bad [and treated] without fully understanding the mechanisms,” she said in an interview.

A great example was the misbegotten flirtation a couple of decades ago with inotropic therapy. It was another no-brainer: drugs that stimulate the heart’s pumping function will help patients with impaired cardiac output. But then trial results showed that chronic inotropic treatment actually hastened patients’ demise. “Patients felt better but they died faster,” Dr. Poppas noted.

Heart failure’s surprises keep coming. During the congress, heart failure expert Dr. Marriel L. Jessup said, “We used to think the reason why patients with acute heart failure were diuretic resistant was because of poor cardiac output. Now we know that they have a lot of venous congestion that impacts the kidneys and liver.”

Another researcher, Dr. John C. Burnett Jr. added, “It’s not just plumbing” that harms the kidneys and liver, but also “deleterious molecules” released because of venous congestion that causes organ damage. The identity of those molecules is only now being explored. And recognition that liver damage is an important part of the heart failure syndrome occurred only recently.

Heart failure continues to reveal its mysteries slowly and reluctantly. Clinicians who believe they know all they need about how to safely and effectively treat it are fooling themselves and run the risk of hurting their patients.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ESC: New review yields reassuring digoxin data

LONDON – The best-quality available evidence demonstrates that digoxin reduces hospital admissions and has no effect upon all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure with or without atrial fibrillation, Dr. Dipak Kotecha reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

His meta-analysis of all observational and randomized controlled studies published since 1960 included 41 studies with 260,335 digoxin-treated patients, roughly 1 million controls, and more than 4 million person-years of follow-up.

What was unique about this meta-analysis is Dr. Kotecha and coworkers assessed each study in terms of its degree of bias due to confounding by indication and other limitations using two standardized bias scoring systems: the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool for randomized controlled trials and the Risk of Bias Assessment tool for Non-randomized Studies (RoBANS).

The level of bias varied greatly among the observational studies. Moreover, the higher an observational study’s bias score, the greater the reported association between digoxin and mortality. In contrast, the seven randomized controlled trials all scored very low on bias and carried a consistent message that digoxin had a neutral effect on mortality, according to Dr. Kotecha of the University of Birmingham (England).

He noted that digoxin was first introduced into clinical cardiology back in 1785 in the form of digitalis. And although digoxin has seen widespread use for heart rate control and symptom reduction in patients with heart failure and/or atrial fibrillation over the years, prescriptions for the venerable drug have markedly declined recently in response to observational studies reporting a link with increased mortality. That purported association, he asserted, is highly dubious.

“Our comprehensive systematic review would suggest that confounding is the main reason why observational studies continue to show increases in mortality associated with digoxin. And this suggests that digoxin should continue to be considered as a treatment option to avoid hospital admissions in patients with heart failure and to achieve heart rate control in those with atrial fibrillation until better randomized data become available,” the cardiologist explained.

“I think that there’s one further important point to make here, and that’s that observational data, particularly when there are systematic differences in the two groups, should not be used to determine clinical efficacy. Propensity matching does not replace a randomized controlled trial in the assessment of efficacy,” he emphasized. “We’ve shown that observational data should be taken with extreme caution because digoxin is a second-line therapy and, like most of us, I tend to give digoxin to patients who are sicker, so we’re bound to see an increase in mortality and hospitalizations in those patients.”

Across all 41 studies, digoxin was associated with a small but clinically meaningful 8% reduction in the rate of all-cause hospitalization.

Asked what data are available regarding optimal dosing of digoxin, the cardiologist replied that the data are limited. “What data there are would suggest lower digoxin doses are better and higher doses tend to cause mortality. So our suggestion would be to continue using low digoxin doses, in combination if necessary with other drugs,” he said.

All of the randomized controlled trials have focused on patients with heart failure, alone or with comorbid atrial fibrillation. None have evaluated the impact of digoxin in patients with atrial fibrillation without heart failure. Given that atrial fibrillation is an emerging modern epidemic and a large chunk of digoxin-prescribing today is for rate control in such patients, this lack of high-quality data constitutes a major unmet need, Dr. Kotecha observed.

The RATE-AF trial, designed to advance knowledge in this area, is due to begin next year. The study, based at the University of Birmingham, will enroll patients with atrial fibrillation without heart failure who need rate control, randomizing them to a beta-blocker or digoxin.

Dr. Kotecha reported having no financial conflicts regarding his meta-analysis, which was funded by a grant from the university’s Arthur Thompson Trust.

Simultaneously with his presentation at the ESC congress, the meta-analysis was published online (BMJ 2105;351:h4451 doi:10.1136/bmj.h4451).

LONDON – The best-quality available evidence demonstrates that digoxin reduces hospital admissions and has no effect upon all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure with or without atrial fibrillation, Dr. Dipak Kotecha reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

His meta-analysis of all observational and randomized controlled studies published since 1960 included 41 studies with 260,335 digoxin-treated patients, roughly 1 million controls, and more than 4 million person-years of follow-up.

What was unique about this meta-analysis is Dr. Kotecha and coworkers assessed each study in terms of its degree of bias due to confounding by indication and other limitations using two standardized bias scoring systems: the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool for randomized controlled trials and the Risk of Bias Assessment tool for Non-randomized Studies (RoBANS).

The level of bias varied greatly among the observational studies. Moreover, the higher an observational study’s bias score, the greater the reported association between digoxin and mortality. In contrast, the seven randomized controlled trials all scored very low on bias and carried a consistent message that digoxin had a neutral effect on mortality, according to Dr. Kotecha of the University of Birmingham (England).

He noted that digoxin was first introduced into clinical cardiology back in 1785 in the form of digitalis. And although digoxin has seen widespread use for heart rate control and symptom reduction in patients with heart failure and/or atrial fibrillation over the years, prescriptions for the venerable drug have markedly declined recently in response to observational studies reporting a link with increased mortality. That purported association, he asserted, is highly dubious.

“Our comprehensive systematic review would suggest that confounding is the main reason why observational studies continue to show increases in mortality associated with digoxin. And this suggests that digoxin should continue to be considered as a treatment option to avoid hospital admissions in patients with heart failure and to achieve heart rate control in those with atrial fibrillation until better randomized data become available,” the cardiologist explained.

“I think that there’s one further important point to make here, and that’s that observational data, particularly when there are systematic differences in the two groups, should not be used to determine clinical efficacy. Propensity matching does not replace a randomized controlled trial in the assessment of efficacy,” he emphasized. “We’ve shown that observational data should be taken with extreme caution because digoxin is a second-line therapy and, like most of us, I tend to give digoxin to patients who are sicker, so we’re bound to see an increase in mortality and hospitalizations in those patients.”

Across all 41 studies, digoxin was associated with a small but clinically meaningful 8% reduction in the rate of all-cause hospitalization.

Asked what data are available regarding optimal dosing of digoxin, the cardiologist replied that the data are limited. “What data there are would suggest lower digoxin doses are better and higher doses tend to cause mortality. So our suggestion would be to continue using low digoxin doses, in combination if necessary with other drugs,” he said.

All of the randomized controlled trials have focused on patients with heart failure, alone or with comorbid atrial fibrillation. None have evaluated the impact of digoxin in patients with atrial fibrillation without heart failure. Given that atrial fibrillation is an emerging modern epidemic and a large chunk of digoxin-prescribing today is for rate control in such patients, this lack of high-quality data constitutes a major unmet need, Dr. Kotecha observed.

The RATE-AF trial, designed to advance knowledge in this area, is due to begin next year. The study, based at the University of Birmingham, will enroll patients with atrial fibrillation without heart failure who need rate control, randomizing them to a beta-blocker or digoxin.

Dr. Kotecha reported having no financial conflicts regarding his meta-analysis, which was funded by a grant from the university’s Arthur Thompson Trust.

Simultaneously with his presentation at the ESC congress, the meta-analysis was published online (BMJ 2105;351:h4451 doi:10.1136/bmj.h4451).

LONDON – The best-quality available evidence demonstrates that digoxin reduces hospital admissions and has no effect upon all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure with or without atrial fibrillation, Dr. Dipak Kotecha reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

His meta-analysis of all observational and randomized controlled studies published since 1960 included 41 studies with 260,335 digoxin-treated patients, roughly 1 million controls, and more than 4 million person-years of follow-up.

What was unique about this meta-analysis is Dr. Kotecha and coworkers assessed each study in terms of its degree of bias due to confounding by indication and other limitations using two standardized bias scoring systems: the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool for randomized controlled trials and the Risk of Bias Assessment tool for Non-randomized Studies (RoBANS).

The level of bias varied greatly among the observational studies. Moreover, the higher an observational study’s bias score, the greater the reported association between digoxin and mortality. In contrast, the seven randomized controlled trials all scored very low on bias and carried a consistent message that digoxin had a neutral effect on mortality, according to Dr. Kotecha of the University of Birmingham (England).

He noted that digoxin was first introduced into clinical cardiology back in 1785 in the form of digitalis. And although digoxin has seen widespread use for heart rate control and symptom reduction in patients with heart failure and/or atrial fibrillation over the years, prescriptions for the venerable drug have markedly declined recently in response to observational studies reporting a link with increased mortality. That purported association, he asserted, is highly dubious.

“Our comprehensive systematic review would suggest that confounding is the main reason why observational studies continue to show increases in mortality associated with digoxin. And this suggests that digoxin should continue to be considered as a treatment option to avoid hospital admissions in patients with heart failure and to achieve heart rate control in those with atrial fibrillation until better randomized data become available,” the cardiologist explained.

“I think that there’s one further important point to make here, and that’s that observational data, particularly when there are systematic differences in the two groups, should not be used to determine clinical efficacy. Propensity matching does not replace a randomized controlled trial in the assessment of efficacy,” he emphasized. “We’ve shown that observational data should be taken with extreme caution because digoxin is a second-line therapy and, like most of us, I tend to give digoxin to patients who are sicker, so we’re bound to see an increase in mortality and hospitalizations in those patients.”

Across all 41 studies, digoxin was associated with a small but clinically meaningful 8% reduction in the rate of all-cause hospitalization.

Asked what data are available regarding optimal dosing of digoxin, the cardiologist replied that the data are limited. “What data there are would suggest lower digoxin doses are better and higher doses tend to cause mortality. So our suggestion would be to continue using low digoxin doses, in combination if necessary with other drugs,” he said.

All of the randomized controlled trials have focused on patients with heart failure, alone or with comorbid atrial fibrillation. None have evaluated the impact of digoxin in patients with atrial fibrillation without heart failure. Given that atrial fibrillation is an emerging modern epidemic and a large chunk of digoxin-prescribing today is for rate control in such patients, this lack of high-quality data constitutes a major unmet need, Dr. Kotecha observed.

The RATE-AF trial, designed to advance knowledge in this area, is due to begin next year. The study, based at the University of Birmingham, will enroll patients with atrial fibrillation without heart failure who need rate control, randomizing them to a beta-blocker or digoxin.

Dr. Kotecha reported having no financial conflicts regarding his meta-analysis, which was funded by a grant from the university’s Arthur Thompson Trust.

Simultaneously with his presentation at the ESC congress, the meta-analysis was published online (BMJ 2105;351:h4451 doi:10.1136/bmj.h4451).

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: Digoxin remains safe and effective in patients with heart failure and/or atrial fibrillation, according to a major new review.

Major finding: Using digoxin in patients with heart failure and/or atrial fibrillation reduces all-cause hospitalizations by 8% and has no impact on mortality.

Data source: A meta-analysis of all studies of the impact of digoxin on death and clinical outcomes published since 1960, including 41 studies with more than a quarter million digoxin-treated patients, 1 million controls, and more than 4 million person-years of follow-up.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, funded by a university grant.

Subclinical heart dysfunction, fatty liver linked

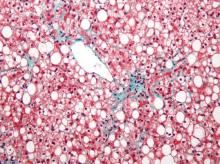

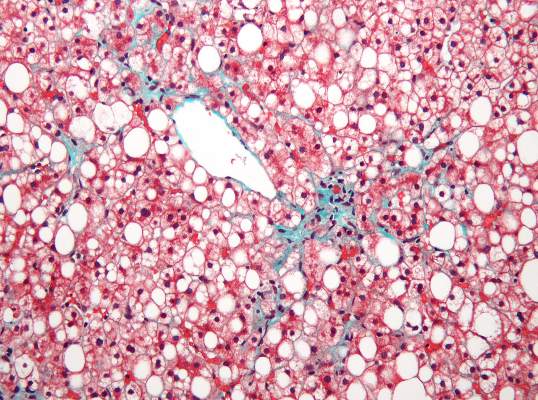

Researchers found an association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and myocardial dysfunction and remodeling, according to a new study published in Hepatology.

“Both NAFLD and heart failure (particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction) are obesity-related conditions that have reached epidemic proportions. We know from epidemiologic studies that persons with NAFLD are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than from liver-related death. This risk seems to be proportional to the amount of fat in the liver and is independent of the presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). There have been numerous studies that have focused on the relationship between NAFLD and coronary artery disease, but very little work has been done to determine relationships with heart failure,” Dr. Lisa B. VanWagner of Northwestern University in Chicago noted. She continued, “There are several well-established major risk factors for the development of clinical heart failure, including coronary artery disease, diabetes, and hypertension, all of which are also closely associated with NAFLD. However, whether NAFLD is independently associated with subclinical myocardial remodeling or dysfunction that may lead to the development of clinical heart failure is unknown.”

NAFLD and heart failure are both associated with obesity. Likewise, there is evidence that NAFLD may also be related to endothelial dysfunction, coronary plaques, coronary artery calcifications, as well as being an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. VanWagner and her colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of 2,713 patients from the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study to understand any associations between NAFLD and abnormalities in left ventricular (LV) function and structure. Study participants completed CT quantification of liver fat and echocardiography with Doppler during the 25-year follow-up to the initial study (Hepatology 2015;62:773-83 [doi:10.1002/hep.27869]). Participants were excluded from analysis if they had missing or incomplete imaging, pregnancy, a history of MI or heart failure, cirrhosis, hepatitis, or chronic liver disease risk factors, or if they weighed more than 450 pounds,

Of the 2,713 subjects included in analysis, 48% were black and 58.8% were female. NAFLD was detected in 10% (n = 271) of participants. Those with NAFLD were more likely to be white males with metabolic syndrome and who were obese and had higher CT-measured levels of visceral adipose tissue, and an increased waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Insulin resistance markers such as elevated fasting glucose, elevated C-reactive protein, and hypertriglyceridemia were more common in the participants with NAFLD.

Study participants with NAFLD had signs of myocardial remodeling such as more left ventricular wall thickness, LV end-diastolic volume, left aortic volume index, and LV mass index. Likewise, NAFLD was associated with more circumferential strain and global longitudinal strain but no differences in ejection fraction.

Subclinical systolic dysfunction (P less than .001 for the trend), subclinical diastolic dysfunction with impaired left ventricular relaxation (34.6% vs. 23.6%; P less than .0001), and elevated LV filling pressures (33.3% vs. 23.7%; P less than .001) was more common in NAFLD participants, compared with non-NAFLD subjects.

After researchers adjusted for health behaviors and demographic factors, evidence of NAFLD was associated with worse GLS (P less than .0001). Finally, NAFLD was associated with subclinical cardiac remodeling and dysfunction even after adjustment for body mass index and heart failure risk factors (P less than .01).

Dr. VanWagner summarized, “NAFLD may not necessarily be a ‘benign condition’ as previously thought. In our study, we determined liver fat by CT scan, which admittedly detects fat at a higher level (typically greater than 30%) than for example on MRI, which can detect fat as low as 5%. A fatty liver detected on CT or even on [ultrasound], which has similar sensitivity as CT for detecting liver fat should prompt evaluation for additional cardiovascular risk factors and treatment of identified abnormalities to reduce [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] and [heart failure] risk. Currently, our study only shows associations between liver fat and subclinical changes in the myocardium and causality cannot be determined. [On the basis] of our data, we cannot recommend screening for HF [heart failure] in this population, but future studies are needed to determine if NAFLD in fact lies in the casual pathway for the development of clinical HF.”

The investigators reported multiple supporting sources, including the National Institutes of Health, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Dr. Lewis reported receiving grants from Novo Nordisk.

Researchers found an association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and myocardial dysfunction and remodeling, according to a new study published in Hepatology.

“Both NAFLD and heart failure (particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction) are obesity-related conditions that have reached epidemic proportions. We know from epidemiologic studies that persons with NAFLD are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than from liver-related death. This risk seems to be proportional to the amount of fat in the liver and is independent of the presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). There have been numerous studies that have focused on the relationship between NAFLD and coronary artery disease, but very little work has been done to determine relationships with heart failure,” Dr. Lisa B. VanWagner of Northwestern University in Chicago noted. She continued, “There are several well-established major risk factors for the development of clinical heart failure, including coronary artery disease, diabetes, and hypertension, all of which are also closely associated with NAFLD. However, whether NAFLD is independently associated with subclinical myocardial remodeling or dysfunction that may lead to the development of clinical heart failure is unknown.”

NAFLD and heart failure are both associated with obesity. Likewise, there is evidence that NAFLD may also be related to endothelial dysfunction, coronary plaques, coronary artery calcifications, as well as being an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. VanWagner and her colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of 2,713 patients from the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study to understand any associations between NAFLD and abnormalities in left ventricular (LV) function and structure. Study participants completed CT quantification of liver fat and echocardiography with Doppler during the 25-year follow-up to the initial study (Hepatology 2015;62:773-83 [doi:10.1002/hep.27869]). Participants were excluded from analysis if they had missing or incomplete imaging, pregnancy, a history of MI or heart failure, cirrhosis, hepatitis, or chronic liver disease risk factors, or if they weighed more than 450 pounds,

Of the 2,713 subjects included in analysis, 48% were black and 58.8% were female. NAFLD was detected in 10% (n = 271) of participants. Those with NAFLD were more likely to be white males with metabolic syndrome and who were obese and had higher CT-measured levels of visceral adipose tissue, and an increased waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Insulin resistance markers such as elevated fasting glucose, elevated C-reactive protein, and hypertriglyceridemia were more common in the participants with NAFLD.

Study participants with NAFLD had signs of myocardial remodeling such as more left ventricular wall thickness, LV end-diastolic volume, left aortic volume index, and LV mass index. Likewise, NAFLD was associated with more circumferential strain and global longitudinal strain but no differences in ejection fraction.

Subclinical systolic dysfunction (P less than .001 for the trend), subclinical diastolic dysfunction with impaired left ventricular relaxation (34.6% vs. 23.6%; P less than .0001), and elevated LV filling pressures (33.3% vs. 23.7%; P less than .001) was more common in NAFLD participants, compared with non-NAFLD subjects.

After researchers adjusted for health behaviors and demographic factors, evidence of NAFLD was associated with worse GLS (P less than .0001). Finally, NAFLD was associated with subclinical cardiac remodeling and dysfunction even after adjustment for body mass index and heart failure risk factors (P less than .01).

Dr. VanWagner summarized, “NAFLD may not necessarily be a ‘benign condition’ as previously thought. In our study, we determined liver fat by CT scan, which admittedly detects fat at a higher level (typically greater than 30%) than for example on MRI, which can detect fat as low as 5%. A fatty liver detected on CT or even on [ultrasound], which has similar sensitivity as CT for detecting liver fat should prompt evaluation for additional cardiovascular risk factors and treatment of identified abnormalities to reduce [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] and [heart failure] risk. Currently, our study only shows associations between liver fat and subclinical changes in the myocardium and causality cannot be determined. [On the basis] of our data, we cannot recommend screening for HF [heart failure] in this population, but future studies are needed to determine if NAFLD in fact lies in the casual pathway for the development of clinical HF.”

The investigators reported multiple supporting sources, including the National Institutes of Health, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Dr. Lewis reported receiving grants from Novo Nordisk.

Researchers found an association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and myocardial dysfunction and remodeling, according to a new study published in Hepatology.

“Both NAFLD and heart failure (particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction) are obesity-related conditions that have reached epidemic proportions. We know from epidemiologic studies that persons with NAFLD are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than from liver-related death. This risk seems to be proportional to the amount of fat in the liver and is independent of the presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). There have been numerous studies that have focused on the relationship between NAFLD and coronary artery disease, but very little work has been done to determine relationships with heart failure,” Dr. Lisa B. VanWagner of Northwestern University in Chicago noted. She continued, “There are several well-established major risk factors for the development of clinical heart failure, including coronary artery disease, diabetes, and hypertension, all of which are also closely associated with NAFLD. However, whether NAFLD is independently associated with subclinical myocardial remodeling or dysfunction that may lead to the development of clinical heart failure is unknown.”

NAFLD and heart failure are both associated with obesity. Likewise, there is evidence that NAFLD may also be related to endothelial dysfunction, coronary plaques, coronary artery calcifications, as well as being an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. VanWagner and her colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of 2,713 patients from the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study to understand any associations between NAFLD and abnormalities in left ventricular (LV) function and structure. Study participants completed CT quantification of liver fat and echocardiography with Doppler during the 25-year follow-up to the initial study (Hepatology 2015;62:773-83 [doi:10.1002/hep.27869]). Participants were excluded from analysis if they had missing or incomplete imaging, pregnancy, a history of MI or heart failure, cirrhosis, hepatitis, or chronic liver disease risk factors, or if they weighed more than 450 pounds,

Of the 2,713 subjects included in analysis, 48% were black and 58.8% were female. NAFLD was detected in 10% (n = 271) of participants. Those with NAFLD were more likely to be white males with metabolic syndrome and who were obese and had higher CT-measured levels of visceral adipose tissue, and an increased waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Insulin resistance markers such as elevated fasting glucose, elevated C-reactive protein, and hypertriglyceridemia were more common in the participants with NAFLD.

Study participants with NAFLD had signs of myocardial remodeling such as more left ventricular wall thickness, LV end-diastolic volume, left aortic volume index, and LV mass index. Likewise, NAFLD was associated with more circumferential strain and global longitudinal strain but no differences in ejection fraction.

Subclinical systolic dysfunction (P less than .001 for the trend), subclinical diastolic dysfunction with impaired left ventricular relaxation (34.6% vs. 23.6%; P less than .0001), and elevated LV filling pressures (33.3% vs. 23.7%; P less than .001) was more common in NAFLD participants, compared with non-NAFLD subjects.

After researchers adjusted for health behaviors and demographic factors, evidence of NAFLD was associated with worse GLS (P less than .0001). Finally, NAFLD was associated with subclinical cardiac remodeling and dysfunction even after adjustment for body mass index and heart failure risk factors (P less than .01).

Dr. VanWagner summarized, “NAFLD may not necessarily be a ‘benign condition’ as previously thought. In our study, we determined liver fat by CT scan, which admittedly detects fat at a higher level (typically greater than 30%) than for example on MRI, which can detect fat as low as 5%. A fatty liver detected on CT or even on [ultrasound], which has similar sensitivity as CT for detecting liver fat should prompt evaluation for additional cardiovascular risk factors and treatment of identified abnormalities to reduce [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] and [heart failure] risk. Currently, our study only shows associations between liver fat and subclinical changes in the myocardium and causality cannot be determined. [On the basis] of our data, we cannot recommend screening for HF [heart failure] in this population, but future studies are needed to determine if NAFLD in fact lies in the casual pathway for the development of clinical HF.”

The investigators reported multiple supporting sources, including the National Institutes of Health, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Dr. Lewis reported receiving grants from Novo Nordisk.

FROM HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Researchers found an association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and myocardial dysfunction and remodeling.

Major finding: Subclinical systolic dysfunction (P less than .001 for the trend), subclinical diastolic dysfunction with impaired left ventricular relaxation (P less than .0001), and elevated LV filling pressures (P less than .001) was more common in participants with NAFLD than in those without.

Data source: A cross-sectional study of 2,713 patients from the CARDIA study using CT quantification of liver fat and echocardiography with Doppler during the 25-year follow-up to the initial study.

Disclosures: The investigators reported multiple supporting sources, including the National Institutes of Health, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Dr. Lewis reported receiving grants from Novo Nordisk.

ESC: Novel apnea treatment not helpful, possibly harmful in heart failure

Adaptive servo-ventilation is not beneficial and may even be harmful for patients who have predominantly central sleep apnea accompanying heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, Dr. Martin R. Cowie reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The noninvasive therapy did control central sleep apnea in a large international randomized controlled trial, but nevertheless did not affect the composite end point of death from any cause, lifesaving cardiovascular intervention, or unplanned hospitalization for worsening HF. Moreover, it unexpectedly raised the risk of cardiovascular death by 34%, and significantly increased all-cause mortality as well, said Dr. Cowie of Imperial College London.

Adaptive servo-ventilation delivers servo-controlled inspiratory pressure on top of expiratory positive airway pressure during sleep, to alleviate central sleep apnea. This form of sleep-disordered breathing, which may manifest as Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients who have HF with reduced ejection fraction, is reported to affect up to 40% of this patient population. Its prevalence rises as the severity of HF increases, and it is an independent risk marker for poor prognosis and death in HF.

A recent trial showed that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) did not improve morbidity or mortality in patients who had HF with central sleep apnea, but suggested that a treatment that could reduce the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) – the number of apnea or hypopnea events per hour of sleep – to below 15 might be effective. Adaptive servo-ventilation can accomplish this, and small studies and meta-analyses have shown that the treatment improves surrogate markers including plasma concentration of brain natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and functional outcomes in heart failure.

Dr. Cowie and his associates conducted the SERVE-HF trial, assessing the effect of adding adaptive servo-ventilation to guideline-based medical therapy on survival and cardiovascular outcomes. He presented the trial results at the meeting, and they were simultaneously published online (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506459).

The industry-sponsored study comprised 1,325 patients aged 22 and older treated and followed at 91 medical centers for a median of 31 months (range, 0-80 months). They were randomly assigned to receive medical therapy plus adaptive servo-ventilation delivered through a face mask for at least 5 hours every night (666 intervention subjects) or medical therapy alone (659 control subjects).

Central sleep apnea was well controlled only in the intervention group. At 1 year, their mean AHI was 6.6 events per hour, and the oxygen desaturation index – the number of times per hour that the blood oxygen level dropped by 3 or more percentage points from baseline level – was 8.6.

Yet the primary composite end point was not significantly different between the two study groups: The rate of death from any cause, lifesaving cardiovascular intervention, and unplanned hospitalization for worsening HF was 54.1% with adaptive servo-ventilation and 50.8% without it. The treatment also had no significant effect on a broad spectrum of secondary measures such as symptoms and quality of life. Six-minute walk distance gradually declined in both groups, but that decline was significantly more pronounced in the intervention group, the investigator said.

Even more worrisome was the significant increase in mortality associated with adaptive servo-ventilation. Cardiovascular mortality was 29.9% with the treatment, compared with 24.0% without it, for a hazard ratio of 1.34. All-cause mortality was 34.8% with the treatment and 29.3% without it, for an HR of 1.28.

The reason for this unexpected result is not yet known. One explanation is that central sleep apnea may be a compensatory mechanism with potentially beneficial effects in patients who have HF. Attenuating those effects with adaptive servo-ventilation may then have been detrimental. For example, central sleep apnea, and particularly Cheyne-Stokes breathing, may beneficially activate the respiratory muscles, increase sympathetic nervous system activity, induce hypercapnic acidosis, increase end-expiratory lung volume, and raise intrinsic positive airway pressure.

Another possibility is that applying positive airway pressure with adaptive servo-ventilation may impair cardiac function in at least a portion of patients who have HF by decreasing cardiac output and stroke volume during treatment.

ResMed, maker of the AutoSet adaptive servo-ventilator, sponsored SERVE-HF, which was also supported by the National Institute for Health Research and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cowie disclosed ties with Servier, Novartis, Pfizer, St. Jude Medical, Boston Scientific, Respicardia,Medtronic, and Bayer; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Adaptive servo-ventilation should not be used outside of clinical trials in heart failure patients who have predominantly central sleep apnea, at least until the reason for the unexpected 34% increase in cardiovascular mortality is understood.

The issue is important because at least one new technique to abolish Cheyne-Stokes respiration that doesn’t use positive pressure therapy – phrenic-nerve stimulation – has already been developed and is being assessed in a clinical trial. If Cheyne-Stokes respiration is actually beneficial in HF, this strategy may prove harmful.

Dr. Ulysses J. Magalang is in the division of pulmonary, allergy, critical care, and sleep medicine at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus. Dr. Allan I. Pack is at the Center for Sleep and Circadian Neurobiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Magalang reported grants support from the Rudi Schulte Family Foundation, Hill-Rom, and the Tzagournis Medical Research Endowment; Dr. Pack reported having no relevant financial disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the SERVE-HF report (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1510397Th).

Adaptive servo-ventilation should not be used outside of clinical trials in heart failure patients who have predominantly central sleep apnea, at least until the reason for the unexpected 34% increase in cardiovascular mortality is understood.

The issue is important because at least one new technique to abolish Cheyne-Stokes respiration that doesn’t use positive pressure therapy – phrenic-nerve stimulation – has already been developed and is being assessed in a clinical trial. If Cheyne-Stokes respiration is actually beneficial in HF, this strategy may prove harmful.

Dr. Ulysses J. Magalang is in the division of pulmonary, allergy, critical care, and sleep medicine at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus. Dr. Allan I. Pack is at the Center for Sleep and Circadian Neurobiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Magalang reported grants support from the Rudi Schulte Family Foundation, Hill-Rom, and the Tzagournis Medical Research Endowment; Dr. Pack reported having no relevant financial disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the SERVE-HF report (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1510397Th).

Adaptive servo-ventilation should not be used outside of clinical trials in heart failure patients who have predominantly central sleep apnea, at least until the reason for the unexpected 34% increase in cardiovascular mortality is understood.

The issue is important because at least one new technique to abolish Cheyne-Stokes respiration that doesn’t use positive pressure therapy – phrenic-nerve stimulation – has already been developed and is being assessed in a clinical trial. If Cheyne-Stokes respiration is actually beneficial in HF, this strategy may prove harmful.

Dr. Ulysses J. Magalang is in the division of pulmonary, allergy, critical care, and sleep medicine at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus. Dr. Allan I. Pack is at the Center for Sleep and Circadian Neurobiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Magalang reported grants support from the Rudi Schulte Family Foundation, Hill-Rom, and the Tzagournis Medical Research Endowment; Dr. Pack reported having no relevant financial disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the SERVE-HF report (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1510397Th).

Adaptive servo-ventilation is not beneficial and may even be harmful for patients who have predominantly central sleep apnea accompanying heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, Dr. Martin R. Cowie reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The noninvasive therapy did control central sleep apnea in a large international randomized controlled trial, but nevertheless did not affect the composite end point of death from any cause, lifesaving cardiovascular intervention, or unplanned hospitalization for worsening HF. Moreover, it unexpectedly raised the risk of cardiovascular death by 34%, and significantly increased all-cause mortality as well, said Dr. Cowie of Imperial College London.

Adaptive servo-ventilation delivers servo-controlled inspiratory pressure on top of expiratory positive airway pressure during sleep, to alleviate central sleep apnea. This form of sleep-disordered breathing, which may manifest as Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients who have HF with reduced ejection fraction, is reported to affect up to 40% of this patient population. Its prevalence rises as the severity of HF increases, and it is an independent risk marker for poor prognosis and death in HF.

A recent trial showed that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) did not improve morbidity or mortality in patients who had HF with central sleep apnea, but suggested that a treatment that could reduce the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) – the number of apnea or hypopnea events per hour of sleep – to below 15 might be effective. Adaptive servo-ventilation can accomplish this, and small studies and meta-analyses have shown that the treatment improves surrogate markers including plasma concentration of brain natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and functional outcomes in heart failure.

Dr. Cowie and his associates conducted the SERVE-HF trial, assessing the effect of adding adaptive servo-ventilation to guideline-based medical therapy on survival and cardiovascular outcomes. He presented the trial results at the meeting, and they were simultaneously published online (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506459).

The industry-sponsored study comprised 1,325 patients aged 22 and older treated and followed at 91 medical centers for a median of 31 months (range, 0-80 months). They were randomly assigned to receive medical therapy plus adaptive servo-ventilation delivered through a face mask for at least 5 hours every night (666 intervention subjects) or medical therapy alone (659 control subjects).

Central sleep apnea was well controlled only in the intervention group. At 1 year, their mean AHI was 6.6 events per hour, and the oxygen desaturation index – the number of times per hour that the blood oxygen level dropped by 3 or more percentage points from baseline level – was 8.6.

Yet the primary composite end point was not significantly different between the two study groups: The rate of death from any cause, lifesaving cardiovascular intervention, and unplanned hospitalization for worsening HF was 54.1% with adaptive servo-ventilation and 50.8% without it. The treatment also had no significant effect on a broad spectrum of secondary measures such as symptoms and quality of life. Six-minute walk distance gradually declined in both groups, but that decline was significantly more pronounced in the intervention group, the investigator said.

Even more worrisome was the significant increase in mortality associated with adaptive servo-ventilation. Cardiovascular mortality was 29.9% with the treatment, compared with 24.0% without it, for a hazard ratio of 1.34. All-cause mortality was 34.8% with the treatment and 29.3% without it, for an HR of 1.28.

The reason for this unexpected result is not yet known. One explanation is that central sleep apnea may be a compensatory mechanism with potentially beneficial effects in patients who have HF. Attenuating those effects with adaptive servo-ventilation may then have been detrimental. For example, central sleep apnea, and particularly Cheyne-Stokes breathing, may beneficially activate the respiratory muscles, increase sympathetic nervous system activity, induce hypercapnic acidosis, increase end-expiratory lung volume, and raise intrinsic positive airway pressure.

Another possibility is that applying positive airway pressure with adaptive servo-ventilation may impair cardiac function in at least a portion of patients who have HF by decreasing cardiac output and stroke volume during treatment.

ResMed, maker of the AutoSet adaptive servo-ventilator, sponsored SERVE-HF, which was also supported by the National Institute for Health Research and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cowie disclosed ties with Servier, Novartis, Pfizer, St. Jude Medical, Boston Scientific, Respicardia,Medtronic, and Bayer; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Adaptive servo-ventilation is not beneficial and may even be harmful for patients who have predominantly central sleep apnea accompanying heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, Dr. Martin R. Cowie reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The noninvasive therapy did control central sleep apnea in a large international randomized controlled trial, but nevertheless did not affect the composite end point of death from any cause, lifesaving cardiovascular intervention, or unplanned hospitalization for worsening HF. Moreover, it unexpectedly raised the risk of cardiovascular death by 34%, and significantly increased all-cause mortality as well, said Dr. Cowie of Imperial College London.

Adaptive servo-ventilation delivers servo-controlled inspiratory pressure on top of expiratory positive airway pressure during sleep, to alleviate central sleep apnea. This form of sleep-disordered breathing, which may manifest as Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients who have HF with reduced ejection fraction, is reported to affect up to 40% of this patient population. Its prevalence rises as the severity of HF increases, and it is an independent risk marker for poor prognosis and death in HF.

A recent trial showed that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) did not improve morbidity or mortality in patients who had HF with central sleep apnea, but suggested that a treatment that could reduce the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) – the number of apnea or hypopnea events per hour of sleep – to below 15 might be effective. Adaptive servo-ventilation can accomplish this, and small studies and meta-analyses have shown that the treatment improves surrogate markers including plasma concentration of brain natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and functional outcomes in heart failure.

Dr. Cowie and his associates conducted the SERVE-HF trial, assessing the effect of adding adaptive servo-ventilation to guideline-based medical therapy on survival and cardiovascular outcomes. He presented the trial results at the meeting, and they were simultaneously published online (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 1. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506459).

The industry-sponsored study comprised 1,325 patients aged 22 and older treated and followed at 91 medical centers for a median of 31 months (range, 0-80 months). They were randomly assigned to receive medical therapy plus adaptive servo-ventilation delivered through a face mask for at least 5 hours every night (666 intervention subjects) or medical therapy alone (659 control subjects).

Central sleep apnea was well controlled only in the intervention group. At 1 year, their mean AHI was 6.6 events per hour, and the oxygen desaturation index – the number of times per hour that the blood oxygen level dropped by 3 or more percentage points from baseline level – was 8.6.

Yet the primary composite end point was not significantly different between the two study groups: The rate of death from any cause, lifesaving cardiovascular intervention, and unplanned hospitalization for worsening HF was 54.1% with adaptive servo-ventilation and 50.8% without it. The treatment also had no significant effect on a broad spectrum of secondary measures such as symptoms and quality of life. Six-minute walk distance gradually declined in both groups, but that decline was significantly more pronounced in the intervention group, the investigator said.

Even more worrisome was the significant increase in mortality associated with adaptive servo-ventilation. Cardiovascular mortality was 29.9% with the treatment, compared with 24.0% without it, for a hazard ratio of 1.34. All-cause mortality was 34.8% with the treatment and 29.3% without it, for an HR of 1.28.

The reason for this unexpected result is not yet known. One explanation is that central sleep apnea may be a compensatory mechanism with potentially beneficial effects in patients who have HF. Attenuating those effects with adaptive servo-ventilation may then have been detrimental. For example, central sleep apnea, and particularly Cheyne-Stokes breathing, may beneficially activate the respiratory muscles, increase sympathetic nervous system activity, induce hypercapnic acidosis, increase end-expiratory lung volume, and raise intrinsic positive airway pressure.