User login

Data Trends 2024: Depression and PTSD

- Inoue C, Shawler E, Jordan CH, Moore MJ, Jackson CA. Veteran and military mental health issues. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 17, 2023. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572092/

- Panaite V, Cohen NJ, Luter SL, et al. Mental health treatment utilization patterns among 108,457 Afghanistan and Iraq veterans with depression. Psychol Serv. 2024 Feb 1. doi:10.1037/ser0000819

- Holder N, Holliday R, Ranney RM, et al. Relationship of social determinants of health with symptom severity among veterans and non-veterans with probable posttraumatic stress disorder or depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2023;58(10):1523-1534. doi:10.1007/s00127-023-02478-0

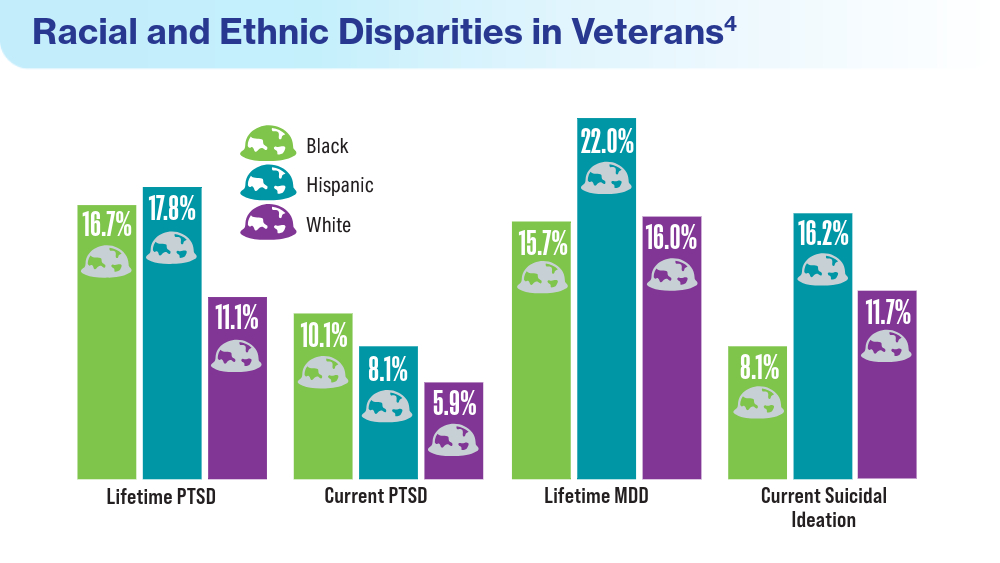

- Merians AN, Gross G, Spoont MR, Bellamy CD, Harpaz-Rotem I, Pietrzak RH. Racial and ethnic mental health disparities in U.S. military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;161:71-76. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.03.005

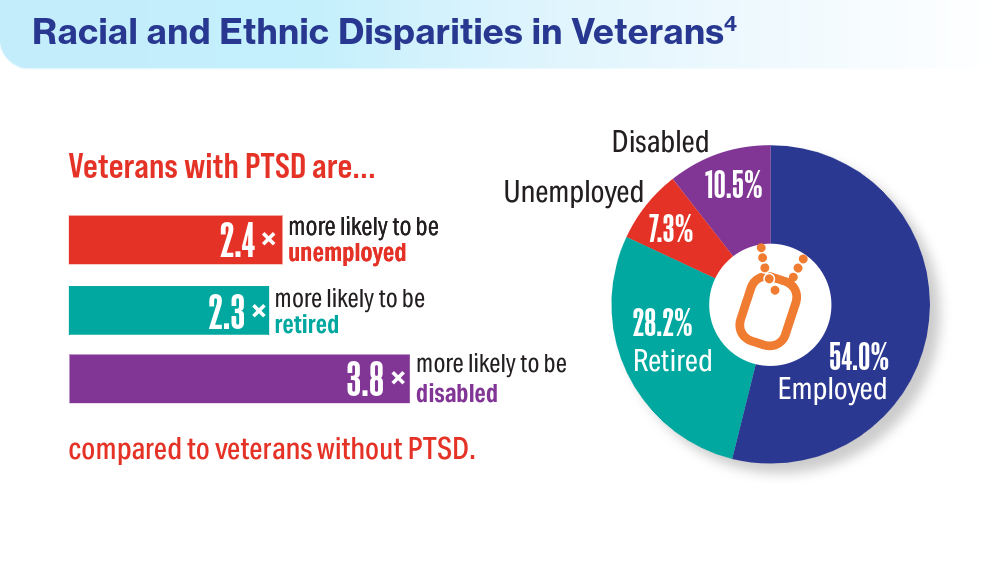

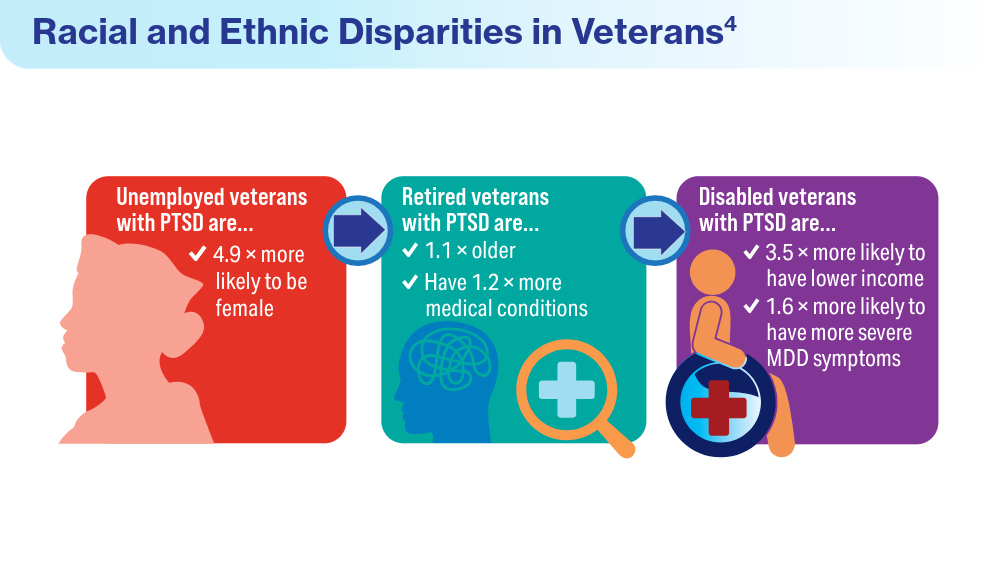

- Fischer IC, Schnurr PP, Pietrzak RH. Employment status among US military veterans with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Trauma Stress. 2023;36(6):1167-1175. doi:10.1002/jts.22977

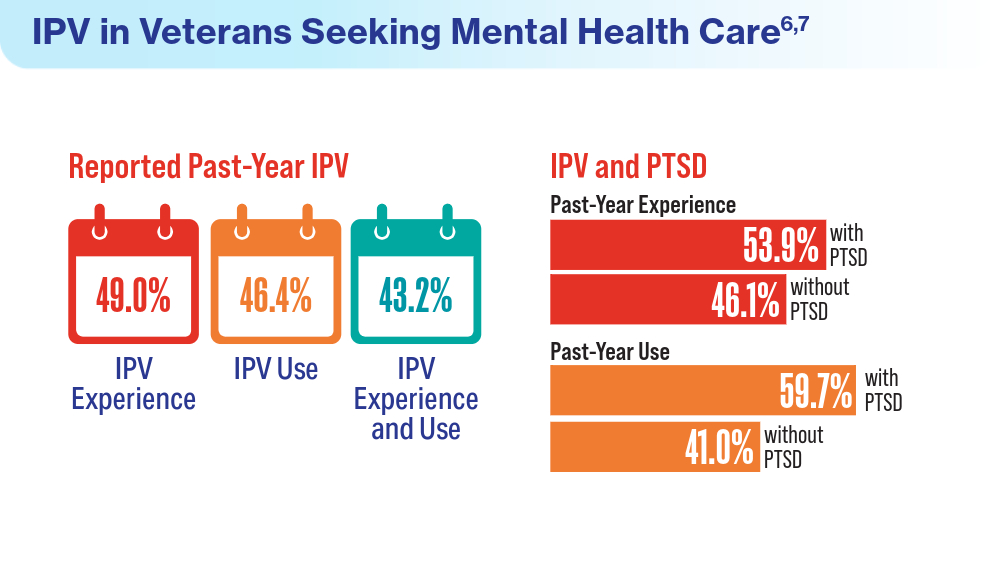

- Portnoy GA, Relyea MR, Presseau C, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence experience and use in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(10):e2337685. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.37685

- Cowlishaw S, Freijah I, Kartal D, et al. Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in Military and Veteran Populations: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Surveys and Population Screening Studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8853. Published 2022 Jul 21. doi:10.3390/ijerph19148853

- Ranney RM, Maguen S, Bernhard PA, et al. Treatment utilization for posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of veterans and nonveterans. Med Care. 2023;61(2):87-94. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001793

- Inoue C, Shawler E, Jordan CH, Moore MJ, Jackson CA. Veteran and military mental health issues. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 17, 2023. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572092/

- Panaite V, Cohen NJ, Luter SL, et al. Mental health treatment utilization patterns among 108,457 Afghanistan and Iraq veterans with depression. Psychol Serv. 2024 Feb 1. doi:10.1037/ser0000819

- Holder N, Holliday R, Ranney RM, et al. Relationship of social determinants of health with symptom severity among veterans and non-veterans with probable posttraumatic stress disorder or depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2023;58(10):1523-1534. doi:10.1007/s00127-023-02478-0

- Merians AN, Gross G, Spoont MR, Bellamy CD, Harpaz-Rotem I, Pietrzak RH. Racial and ethnic mental health disparities in U.S. military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;161:71-76. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.03.005

- Fischer IC, Schnurr PP, Pietrzak RH. Employment status among US military veterans with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Trauma Stress. 2023;36(6):1167-1175. doi:10.1002/jts.22977

- Portnoy GA, Relyea MR, Presseau C, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence experience and use in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(10):e2337685. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.37685

- Cowlishaw S, Freijah I, Kartal D, et al. Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in Military and Veteran Populations: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Surveys and Population Screening Studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8853. Published 2022 Jul 21. doi:10.3390/ijerph19148853

- Ranney RM, Maguen S, Bernhard PA, et al. Treatment utilization for posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of veterans and nonveterans. Med Care. 2023;61(2):87-94. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001793

- Inoue C, Shawler E, Jordan CH, Moore MJ, Jackson CA. Veteran and military mental health issues. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 17, 2023. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572092/

- Panaite V, Cohen NJ, Luter SL, et al. Mental health treatment utilization patterns among 108,457 Afghanistan and Iraq veterans with depression. Psychol Serv. 2024 Feb 1. doi:10.1037/ser0000819

- Holder N, Holliday R, Ranney RM, et al. Relationship of social determinants of health with symptom severity among veterans and non-veterans with probable posttraumatic stress disorder or depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2023;58(10):1523-1534. doi:10.1007/s00127-023-02478-0

- Merians AN, Gross G, Spoont MR, Bellamy CD, Harpaz-Rotem I, Pietrzak RH. Racial and ethnic mental health disparities in U.S. military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;161:71-76. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.03.005

- Fischer IC, Schnurr PP, Pietrzak RH. Employment status among US military veterans with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Trauma Stress. 2023;36(6):1167-1175. doi:10.1002/jts.22977

- Portnoy GA, Relyea MR, Presseau C, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence experience and use in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(10):e2337685. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.37685

- Cowlishaw S, Freijah I, Kartal D, et al. Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in Military and Veteran Populations: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Surveys and Population Screening Studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8853. Published 2022 Jul 21. doi:10.3390/ijerph19148853

- Ranney RM, Maguen S, Bernhard PA, et al. Treatment utilization for posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of veterans and nonveterans. Med Care. 2023;61(2):87-94. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001793

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2024

New Biological Pathway May Explain BPA Exposure, Autism Link

BPA is a potent endocrine disruptor found in polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins and has been banned by the Food and Drug Administration for use in baby bottles, sippy cups, and infant formula packaging.

“Exposure to BPA has already been shown in some studies to be associated with subsequent autism in offspring,” lead researcher Anne-Louise Ponsonby, PhD, The Florey Institute, Heidelberg, Australia, said in a statement.

“Our work is important because it demonstrates one of the biological mechanisms potentially involved. BPA can disrupt hormone-controlled male fetal brain development in several ways, including silencing a key enzyme, aromatase, that controls neurohormones and is especially important in fetal male brain development. This appears to be part of the autism puzzle,” she said.

Brain aromatase, encoded by CYP19A1, converts neural androgens to neural estrogens and has been implicated in ASD. Postmortem analyses of men with ASD also show markedly reduced aromatase activity.

The findings were published online in Nature Communications.

New Biological Mechanism

For the study, the researchers analyzed data from the Barwon Infant Study in 1067 infants in Australia. At age 7-11 years, 43 children had a confirmed ASD diagnosis, and 249 infants with Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) data at age 2 years had an autism spectrum problem score above the median.

The researchers developed a CYP19A1 genetic score for aromatase activity based on five single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with lower estrogen levels. Among 595 children with prenatal BPA and CBCL, those with three or more variants were classified as “low aromatase activity” and the remaining were classified as “high.”

In regression analyses, boys with low aromatase activity and high prenatal BPA exposure (top quartile > 2.18 µg/L) were 3.5 times more likely to have autism symptoms at age 2 years (odds ratio [OR], 3.56; 95% CI, 1.13-11.22).

The odds of a confirmed ASD diagnosis were six times higher at age 9 years only in men with low aromatase activity (OR, 6.24; 95% CI, 1.02-38.26).

The researchers also found that higher BPA levels predicted higher methylation in cord blood across the CYP19A1 brain promoter PI.f region (P = .009).

To replicate the findings, data were used from the Columbia Centre for Children’s Health Study–Mothers and Newborns cohort in the United States. Once again, the BPA level was associated with hypermethylation of the aromatase brain promoter PI.f (P = .0089).

In both cohorts, there was evidence that the effect of increased BPA on brain-derived neurotrophic factor hypermethylation was mediated partly through higher aromatase gene methylation (P = .001).

To validate the findings, the researchers examined human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell lines and found aromatase protein levels were more than halved in the presence of BPA 50 µg/L (P = .01).

Additionally, mouse studies showed that male mice exposed to BPA 50 µg/L mid-gestation and male aromatase knockout mice — but not female mice — had social behavior deficits, such as interacting with a strange mouse, as well as structural and functional brain changes.

“We found that BPA suppresses the aromatase enzyme and is associated with anatomical, neurologic, and behavioral changes in the male mice that may be consistent with autism spectrum disorder,” Wah Chin Boon, PhD, co–lead researcher and research fellow, also with The Florey Institute, said in a statement.

“This is the first time a biological pathway has been identified that might help explain the connection between autism and BPA,” she said.

“In this study, not only were the levels of BPA higher than most people would be exposed to, but in at least one of the experiments the mice were injected with BPA directly, whereas humans would be exposed via food and drink,” observed Oliver Jones, PhD, MSc, professor of chemistry, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. “If you ingest the food, it undergoes metabolism before it gets to the bloodstream, which reduces the effective dose.”

Dr. Jones said further studies with larger numbers of participants measuring BPA throughout pregnancy and other chemicals the mother and child were exposed to are needed to be sure of any such link. “Just because there is a possible mechanism in place does not automatically mean that it is activated,” he said.

Dr. Ponsonby pointed out that BPA and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals are “almost impossible for individuals to avoid” and can enter the body through plastic food and drink packaging, home renovation fumes, and sources such as cosmetics.

Fatty Acid Helpful?

Building on earlier observations that 10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid (10HDA) may have estrogenic modulating activities, the researchers conducted additional studies suggesting that 10HDA may be effective as a competitive ligand that could counteract the effects of BPA on estrogen signaling within cells.

Further, among 3-week-old mice pups prenatally exposed to BPA, daily injections of 10HDA for 3 weeks showed striking and significant improvements in social interaction. Stopping 10HDA resulted in a deficit in social interaction that was again ameliorated by subsequent 10HDA treatment.

“10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid shows early indications of potential in activating opposing biological pathways to improve autism-like characteristics when administered to animals that have been prenatally exposed to BPA,” Dr. Boon said. “It warrants further studies to see whether this potential treatment could be realized in humans.”

Reached for comment, Dr. Jones said “the human studies are not strong at all,” in large part because BPA levels were tested only once at 36 weeks in the BIS cohort.

“I would argue that if BPA is in the urine, it has been excreted and is no longer in the bloodstream, thus not able to affect the child,” he said. “I’d also argue that a single measurement at 36 weeks cannot give you any idea of the mother’s exposure to BPA over the rest of the pregnancy or what the child was exposed to after birth.”

The study was funded by the Minderoo Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Australian Research Council, and numerous other sponsors. Dr. Boon is a coinventor on “Methods of treating neurodevelopmental diseases and disorders” and is a board member of Meizon Innovation Holdings. Dr. Ponsonby is a scientific adviser to Meizon Innovation Holdings. The remaining authors declared no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BPA is a potent endocrine disruptor found in polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins and has been banned by the Food and Drug Administration for use in baby bottles, sippy cups, and infant formula packaging.

“Exposure to BPA has already been shown in some studies to be associated with subsequent autism in offspring,” lead researcher Anne-Louise Ponsonby, PhD, The Florey Institute, Heidelberg, Australia, said in a statement.

“Our work is important because it demonstrates one of the biological mechanisms potentially involved. BPA can disrupt hormone-controlled male fetal brain development in several ways, including silencing a key enzyme, aromatase, that controls neurohormones and is especially important in fetal male brain development. This appears to be part of the autism puzzle,” she said.

Brain aromatase, encoded by CYP19A1, converts neural androgens to neural estrogens and has been implicated in ASD. Postmortem analyses of men with ASD also show markedly reduced aromatase activity.

The findings were published online in Nature Communications.

New Biological Mechanism

For the study, the researchers analyzed data from the Barwon Infant Study in 1067 infants in Australia. At age 7-11 years, 43 children had a confirmed ASD diagnosis, and 249 infants with Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) data at age 2 years had an autism spectrum problem score above the median.

The researchers developed a CYP19A1 genetic score for aromatase activity based on five single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with lower estrogen levels. Among 595 children with prenatal BPA and CBCL, those with three or more variants were classified as “low aromatase activity” and the remaining were classified as “high.”

In regression analyses, boys with low aromatase activity and high prenatal BPA exposure (top quartile > 2.18 µg/L) were 3.5 times more likely to have autism symptoms at age 2 years (odds ratio [OR], 3.56; 95% CI, 1.13-11.22).

The odds of a confirmed ASD diagnosis were six times higher at age 9 years only in men with low aromatase activity (OR, 6.24; 95% CI, 1.02-38.26).

The researchers also found that higher BPA levels predicted higher methylation in cord blood across the CYP19A1 brain promoter PI.f region (P = .009).

To replicate the findings, data were used from the Columbia Centre for Children’s Health Study–Mothers and Newborns cohort in the United States. Once again, the BPA level was associated with hypermethylation of the aromatase brain promoter PI.f (P = .0089).

In both cohorts, there was evidence that the effect of increased BPA on brain-derived neurotrophic factor hypermethylation was mediated partly through higher aromatase gene methylation (P = .001).

To validate the findings, the researchers examined human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell lines and found aromatase protein levels were more than halved in the presence of BPA 50 µg/L (P = .01).

Additionally, mouse studies showed that male mice exposed to BPA 50 µg/L mid-gestation and male aromatase knockout mice — but not female mice — had social behavior deficits, such as interacting with a strange mouse, as well as structural and functional brain changes.

“We found that BPA suppresses the aromatase enzyme and is associated with anatomical, neurologic, and behavioral changes in the male mice that may be consistent with autism spectrum disorder,” Wah Chin Boon, PhD, co–lead researcher and research fellow, also with The Florey Institute, said in a statement.

“This is the first time a biological pathway has been identified that might help explain the connection between autism and BPA,” she said.

“In this study, not only were the levels of BPA higher than most people would be exposed to, but in at least one of the experiments the mice were injected with BPA directly, whereas humans would be exposed via food and drink,” observed Oliver Jones, PhD, MSc, professor of chemistry, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. “If you ingest the food, it undergoes metabolism before it gets to the bloodstream, which reduces the effective dose.”

Dr. Jones said further studies with larger numbers of participants measuring BPA throughout pregnancy and other chemicals the mother and child were exposed to are needed to be sure of any such link. “Just because there is a possible mechanism in place does not automatically mean that it is activated,” he said.

Dr. Ponsonby pointed out that BPA and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals are “almost impossible for individuals to avoid” and can enter the body through plastic food and drink packaging, home renovation fumes, and sources such as cosmetics.

Fatty Acid Helpful?

Building on earlier observations that 10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid (10HDA) may have estrogenic modulating activities, the researchers conducted additional studies suggesting that 10HDA may be effective as a competitive ligand that could counteract the effects of BPA on estrogen signaling within cells.

Further, among 3-week-old mice pups prenatally exposed to BPA, daily injections of 10HDA for 3 weeks showed striking and significant improvements in social interaction. Stopping 10HDA resulted in a deficit in social interaction that was again ameliorated by subsequent 10HDA treatment.

“10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid shows early indications of potential in activating opposing biological pathways to improve autism-like characteristics when administered to animals that have been prenatally exposed to BPA,” Dr. Boon said. “It warrants further studies to see whether this potential treatment could be realized in humans.”

Reached for comment, Dr. Jones said “the human studies are not strong at all,” in large part because BPA levels were tested only once at 36 weeks in the BIS cohort.

“I would argue that if BPA is in the urine, it has been excreted and is no longer in the bloodstream, thus not able to affect the child,” he said. “I’d also argue that a single measurement at 36 weeks cannot give you any idea of the mother’s exposure to BPA over the rest of the pregnancy or what the child was exposed to after birth.”

The study was funded by the Minderoo Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Australian Research Council, and numerous other sponsors. Dr. Boon is a coinventor on “Methods of treating neurodevelopmental diseases and disorders” and is a board member of Meizon Innovation Holdings. Dr. Ponsonby is a scientific adviser to Meizon Innovation Holdings. The remaining authors declared no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BPA is a potent endocrine disruptor found in polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins and has been banned by the Food and Drug Administration for use in baby bottles, sippy cups, and infant formula packaging.

“Exposure to BPA has already been shown in some studies to be associated with subsequent autism in offspring,” lead researcher Anne-Louise Ponsonby, PhD, The Florey Institute, Heidelberg, Australia, said in a statement.

“Our work is important because it demonstrates one of the biological mechanisms potentially involved. BPA can disrupt hormone-controlled male fetal brain development in several ways, including silencing a key enzyme, aromatase, that controls neurohormones and is especially important in fetal male brain development. This appears to be part of the autism puzzle,” she said.

Brain aromatase, encoded by CYP19A1, converts neural androgens to neural estrogens and has been implicated in ASD. Postmortem analyses of men with ASD also show markedly reduced aromatase activity.

The findings were published online in Nature Communications.

New Biological Mechanism

For the study, the researchers analyzed data from the Barwon Infant Study in 1067 infants in Australia. At age 7-11 years, 43 children had a confirmed ASD diagnosis, and 249 infants with Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) data at age 2 years had an autism spectrum problem score above the median.

The researchers developed a CYP19A1 genetic score for aromatase activity based on five single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with lower estrogen levels. Among 595 children with prenatal BPA and CBCL, those with three or more variants were classified as “low aromatase activity” and the remaining were classified as “high.”

In regression analyses, boys with low aromatase activity and high prenatal BPA exposure (top quartile > 2.18 µg/L) were 3.5 times more likely to have autism symptoms at age 2 years (odds ratio [OR], 3.56; 95% CI, 1.13-11.22).

The odds of a confirmed ASD diagnosis were six times higher at age 9 years only in men with low aromatase activity (OR, 6.24; 95% CI, 1.02-38.26).

The researchers also found that higher BPA levels predicted higher methylation in cord blood across the CYP19A1 brain promoter PI.f region (P = .009).

To replicate the findings, data were used from the Columbia Centre for Children’s Health Study–Mothers and Newborns cohort in the United States. Once again, the BPA level was associated with hypermethylation of the aromatase brain promoter PI.f (P = .0089).

In both cohorts, there was evidence that the effect of increased BPA on brain-derived neurotrophic factor hypermethylation was mediated partly through higher aromatase gene methylation (P = .001).

To validate the findings, the researchers examined human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell lines and found aromatase protein levels were more than halved in the presence of BPA 50 µg/L (P = .01).

Additionally, mouse studies showed that male mice exposed to BPA 50 µg/L mid-gestation and male aromatase knockout mice — but not female mice — had social behavior deficits, such as interacting with a strange mouse, as well as structural and functional brain changes.

“We found that BPA suppresses the aromatase enzyme and is associated with anatomical, neurologic, and behavioral changes in the male mice that may be consistent with autism spectrum disorder,” Wah Chin Boon, PhD, co–lead researcher and research fellow, also with The Florey Institute, said in a statement.

“This is the first time a biological pathway has been identified that might help explain the connection between autism and BPA,” she said.

“In this study, not only were the levels of BPA higher than most people would be exposed to, but in at least one of the experiments the mice were injected with BPA directly, whereas humans would be exposed via food and drink,” observed Oliver Jones, PhD, MSc, professor of chemistry, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. “If you ingest the food, it undergoes metabolism before it gets to the bloodstream, which reduces the effective dose.”

Dr. Jones said further studies with larger numbers of participants measuring BPA throughout pregnancy and other chemicals the mother and child were exposed to are needed to be sure of any such link. “Just because there is a possible mechanism in place does not automatically mean that it is activated,” he said.

Dr. Ponsonby pointed out that BPA and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals are “almost impossible for individuals to avoid” and can enter the body through plastic food and drink packaging, home renovation fumes, and sources such as cosmetics.

Fatty Acid Helpful?

Building on earlier observations that 10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid (10HDA) may have estrogenic modulating activities, the researchers conducted additional studies suggesting that 10HDA may be effective as a competitive ligand that could counteract the effects of BPA on estrogen signaling within cells.

Further, among 3-week-old mice pups prenatally exposed to BPA, daily injections of 10HDA for 3 weeks showed striking and significant improvements in social interaction. Stopping 10HDA resulted in a deficit in social interaction that was again ameliorated by subsequent 10HDA treatment.

“10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid shows early indications of potential in activating opposing biological pathways to improve autism-like characteristics when administered to animals that have been prenatally exposed to BPA,” Dr. Boon said. “It warrants further studies to see whether this potential treatment could be realized in humans.”

Reached for comment, Dr. Jones said “the human studies are not strong at all,” in large part because BPA levels were tested only once at 36 weeks in the BIS cohort.

“I would argue that if BPA is in the urine, it has been excreted and is no longer in the bloodstream, thus not able to affect the child,” he said. “I’d also argue that a single measurement at 36 weeks cannot give you any idea of the mother’s exposure to BPA over the rest of the pregnancy or what the child was exposed to after birth.”

The study was funded by the Minderoo Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Australian Research Council, and numerous other sponsors. Dr. Boon is a coinventor on “Methods of treating neurodevelopmental diseases and disorders” and is a board member of Meizon Innovation Holdings. Dr. Ponsonby is a scientific adviser to Meizon Innovation Holdings. The remaining authors declared no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

Sexual Arousal Cream Promising in Some Subsets of Women

Topical sildenafil (citrate) cream 3.6% used by healthy premenopausal women with a primary symptom of female sexual arousal disorder did not show statistically significant improvement over placebo in the coprimary or secondary endpoints over a 3-month period in new preliminary study data published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Topical sildenafil cream is currently used for erectile dysfunction in men. There are no US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for female sexual arousal disorder, which affects up to 26% of women in the United States by some estimates.

Isabella Johnson, senior manager of product development at Daré Bioscience, San Diego, California, led a phase 2b, exploratory, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of sildenafil cream’s potential to help women improve their sexual experiences.

The study included 200 women with female sexual arousal disorder randomized to sildenafil cream (n = 101) or placebo cream (n = 99); 177 completed the trial and made up the intention-to-treat group. Healthy premenopausal women at least 18 years old and their sexual partners were screened for the study.

The authors report that the primary endpoints were scores on Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ28) arousal sensation domain and question 14 on the Female Sexual Distress Scale — Desire/Arousal/Orgasm (FSD-DAO), which asks “How often in the past 30 days did you feel concerned by difficulties with sexual arousal?” The secondary endpoint was the average number and average proportion of satisfactory sexual events. Topical sildenafil was not more effective than placebo with these primary or secondary endpoints.

Some Subgroups Benefited

However, a post hoc analysis told a different story. “[A]mong a subset of women with female sexual arousal disorder only or female sexual arousal disorder with concomitant decreased desire, we found either trends or significant improvements in sexual functioning with sildenafil cream compared with placebo cream across multiple aspects of sexual function,” the authors write.

The researchers also noted that several FSDS-DAO questions, other than question 14, asked about generalized feelings related to sexual distress and interpersonal difficulties and scores on those questions showed significant improvement with sildenafil cream compared with placebo in the exploratory subset.

“The total FSDS-DAO score decreased by about 7 points for sildenafil cream users in the subset population (a clinically meaningful decrease in sexual distress) compared with a two-point decrease for placebo cream users (P = .10),” they write.

Post Hoc Analysis Is Exploratory

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD, with the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Virginia Health in Charlottesville, writes in an editorial that because the authors did not adjust for multiple hypothesis testing, the post hoc subset analyses should be considered only exploratory.

She notes that the trial was underpowered partly because it was halted after recruitment challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. The small sample size and the varied reasons for arousal disorder among the women “may have limited the ability to find a positive outcome.”

, Dr. Pinkerton writes.

“Because improvement in genital arousal is thought to be due to the increased genital blood flow from sildenafil citrate, the subset of participants found least likely to benefit from sildenafil citrate cream were those with concomitant orgasmic dysfunction with or without genital pain,” she writes.

Data May Inform Phase 3 Trial

This phase 2b trial sets the stage for a phase 3 trial, she writes, to evaluate sildenafil topical cream in women with female sexual arousal disorder in the subsets where there were positive findings (those with or without a secondary diagnosis of decreased desire) but not among women having difficulty reaching orgasm.

“If positive, it could lead to a new therapeutic area for the unmet treatment needs of premenopausal and postmenopausal women with female sexual arousal disorder,” Dr. Pinkerton writes.

A study coauthor, Clint Dart, reports money was paid to his institution from Daré Bioscience, he provided independent data verification, and he is an employee of Premier Research. Isabella Johnson, Andrea Ries Thurman, MD, Jessica Hatheway, MBA, David R. Friend, PhD, and Andrew Goldstein, MD, are employees of Daré Bioscience. Katherine A. Cornell is an employee of Strategic Science & Technologies, LLC. C. Paige Brainard, MD, was financially compensated by Del Sol Research Management and her practice received funding from Daré Bioscience for study-specific activities. Dr. Goldstein also reported receiving payments from Nuvig, Ipsen, and AbbVie. Dr. Pinkerton’s institution received funds from Bayer Pharmaceuticals as she served as PI for a multinational clinical trial.

Topical sildenafil (citrate) cream 3.6% used by healthy premenopausal women with a primary symptom of female sexual arousal disorder did not show statistically significant improvement over placebo in the coprimary or secondary endpoints over a 3-month period in new preliminary study data published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Topical sildenafil cream is currently used for erectile dysfunction in men. There are no US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for female sexual arousal disorder, which affects up to 26% of women in the United States by some estimates.

Isabella Johnson, senior manager of product development at Daré Bioscience, San Diego, California, led a phase 2b, exploratory, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of sildenafil cream’s potential to help women improve their sexual experiences.

The study included 200 women with female sexual arousal disorder randomized to sildenafil cream (n = 101) or placebo cream (n = 99); 177 completed the trial and made up the intention-to-treat group. Healthy premenopausal women at least 18 years old and their sexual partners were screened for the study.

The authors report that the primary endpoints were scores on Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ28) arousal sensation domain and question 14 on the Female Sexual Distress Scale — Desire/Arousal/Orgasm (FSD-DAO), which asks “How often in the past 30 days did you feel concerned by difficulties with sexual arousal?” The secondary endpoint was the average number and average proportion of satisfactory sexual events. Topical sildenafil was not more effective than placebo with these primary or secondary endpoints.

Some Subgroups Benefited

However, a post hoc analysis told a different story. “[A]mong a subset of women with female sexual arousal disorder only or female sexual arousal disorder with concomitant decreased desire, we found either trends or significant improvements in sexual functioning with sildenafil cream compared with placebo cream across multiple aspects of sexual function,” the authors write.

The researchers also noted that several FSDS-DAO questions, other than question 14, asked about generalized feelings related to sexual distress and interpersonal difficulties and scores on those questions showed significant improvement with sildenafil cream compared with placebo in the exploratory subset.

“The total FSDS-DAO score decreased by about 7 points for sildenafil cream users in the subset population (a clinically meaningful decrease in sexual distress) compared with a two-point decrease for placebo cream users (P = .10),” they write.

Post Hoc Analysis Is Exploratory

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD, with the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Virginia Health in Charlottesville, writes in an editorial that because the authors did not adjust for multiple hypothesis testing, the post hoc subset analyses should be considered only exploratory.

She notes that the trial was underpowered partly because it was halted after recruitment challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. The small sample size and the varied reasons for arousal disorder among the women “may have limited the ability to find a positive outcome.”

, Dr. Pinkerton writes.

“Because improvement in genital arousal is thought to be due to the increased genital blood flow from sildenafil citrate, the subset of participants found least likely to benefit from sildenafil citrate cream were those with concomitant orgasmic dysfunction with or without genital pain,” she writes.

Data May Inform Phase 3 Trial

This phase 2b trial sets the stage for a phase 3 trial, she writes, to evaluate sildenafil topical cream in women with female sexual arousal disorder in the subsets where there were positive findings (those with or without a secondary diagnosis of decreased desire) but not among women having difficulty reaching orgasm.

“If positive, it could lead to a new therapeutic area for the unmet treatment needs of premenopausal and postmenopausal women with female sexual arousal disorder,” Dr. Pinkerton writes.

A study coauthor, Clint Dart, reports money was paid to his institution from Daré Bioscience, he provided independent data verification, and he is an employee of Premier Research. Isabella Johnson, Andrea Ries Thurman, MD, Jessica Hatheway, MBA, David R. Friend, PhD, and Andrew Goldstein, MD, are employees of Daré Bioscience. Katherine A. Cornell is an employee of Strategic Science & Technologies, LLC. C. Paige Brainard, MD, was financially compensated by Del Sol Research Management and her practice received funding from Daré Bioscience for study-specific activities. Dr. Goldstein also reported receiving payments from Nuvig, Ipsen, and AbbVie. Dr. Pinkerton’s institution received funds from Bayer Pharmaceuticals as she served as PI for a multinational clinical trial.

Topical sildenafil (citrate) cream 3.6% used by healthy premenopausal women with a primary symptom of female sexual arousal disorder did not show statistically significant improvement over placebo in the coprimary or secondary endpoints over a 3-month period in new preliminary study data published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Topical sildenafil cream is currently used for erectile dysfunction in men. There are no US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for female sexual arousal disorder, which affects up to 26% of women in the United States by some estimates.

Isabella Johnson, senior manager of product development at Daré Bioscience, San Diego, California, led a phase 2b, exploratory, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of sildenafil cream’s potential to help women improve their sexual experiences.

The study included 200 women with female sexual arousal disorder randomized to sildenafil cream (n = 101) or placebo cream (n = 99); 177 completed the trial and made up the intention-to-treat group. Healthy premenopausal women at least 18 years old and their sexual partners were screened for the study.

The authors report that the primary endpoints were scores on Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ28) arousal sensation domain and question 14 on the Female Sexual Distress Scale — Desire/Arousal/Orgasm (FSD-DAO), which asks “How often in the past 30 days did you feel concerned by difficulties with sexual arousal?” The secondary endpoint was the average number and average proportion of satisfactory sexual events. Topical sildenafil was not more effective than placebo with these primary or secondary endpoints.

Some Subgroups Benefited

However, a post hoc analysis told a different story. “[A]mong a subset of women with female sexual arousal disorder only or female sexual arousal disorder with concomitant decreased desire, we found either trends or significant improvements in sexual functioning with sildenafil cream compared with placebo cream across multiple aspects of sexual function,” the authors write.

The researchers also noted that several FSDS-DAO questions, other than question 14, asked about generalized feelings related to sexual distress and interpersonal difficulties and scores on those questions showed significant improvement with sildenafil cream compared with placebo in the exploratory subset.

“The total FSDS-DAO score decreased by about 7 points for sildenafil cream users in the subset population (a clinically meaningful decrease in sexual distress) compared with a two-point decrease for placebo cream users (P = .10),” they write.

Post Hoc Analysis Is Exploratory

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD, with the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Virginia Health in Charlottesville, writes in an editorial that because the authors did not adjust for multiple hypothesis testing, the post hoc subset analyses should be considered only exploratory.

She notes that the trial was underpowered partly because it was halted after recruitment challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. The small sample size and the varied reasons for arousal disorder among the women “may have limited the ability to find a positive outcome.”

, Dr. Pinkerton writes.

“Because improvement in genital arousal is thought to be due to the increased genital blood flow from sildenafil citrate, the subset of participants found least likely to benefit from sildenafil citrate cream were those with concomitant orgasmic dysfunction with or without genital pain,” she writes.

Data May Inform Phase 3 Trial

This phase 2b trial sets the stage for a phase 3 trial, she writes, to evaluate sildenafil topical cream in women with female sexual arousal disorder in the subsets where there were positive findings (those with or without a secondary diagnosis of decreased desire) but not among women having difficulty reaching orgasm.

“If positive, it could lead to a new therapeutic area for the unmet treatment needs of premenopausal and postmenopausal women with female sexual arousal disorder,” Dr. Pinkerton writes.

A study coauthor, Clint Dart, reports money was paid to his institution from Daré Bioscience, he provided independent data verification, and he is an employee of Premier Research. Isabella Johnson, Andrea Ries Thurman, MD, Jessica Hatheway, MBA, David R. Friend, PhD, and Andrew Goldstein, MD, are employees of Daré Bioscience. Katherine A. Cornell is an employee of Strategic Science & Technologies, LLC. C. Paige Brainard, MD, was financially compensated by Del Sol Research Management and her practice received funding from Daré Bioscience for study-specific activities. Dr. Goldstein also reported receiving payments from Nuvig, Ipsen, and AbbVie. Dr. Pinkerton’s institution received funds from Bayer Pharmaceuticals as she served as PI for a multinational clinical trial.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Navigating Election Anxiety: How Worry Affects the Brain

Once again, America is deeply divided before a national election, with people on each side convinced of the horrors that will be visited upon us if the other side wins.

’Tis the season — and regrettably, not to be jolly but to be worried.

As a neuroscientist, I am especially aware of the deleterious mental and physical impact of chronic worry on our citizenry. That’s because worry is not “all in your head.” We modern humans live in a world of worry which appears to be progressively growing.

Flight or Fight

Worry stems from the brain’s rather remarkable ability to foresee and reflexively respond to threat. Our “fight or flight” brain machinery probably arose in our vertebrate ancestors more than 300 million years ago. The fact that we have machinery akin to that possessed by lizards or tigers or shrews is testimony to its crucial contribution to our species’ survival.

As the phrase “fight or flight” suggests, a brain that senses trouble immediately biases certain body and brain functions. As it shifts into a higher-alert mode, it increases the energy supplies in our blood and supports other changes that facilitate faster and stronger reactions, while it shuts down less essential processes which do not contribute to hiding, fighting, or running like hell.

This hyperreactive response is initiated in the amygdala in the anterior brain, which identifies “what’s happening” as immediately or potentially threatening. The now-activated amygdala generates a response in the hypothalamus that provokes an immediate increase of adrenaline and cortisol in the body, and cortisol and noradrenaline in the brain. Both sharply speed up our physical and neurologic reactivity. In the brain, that is achieved by increasing the level of excitability of neurons across the forebrain. Depending on the perceived level of threat, an excitable brain will be just a little or a lot more “on alert,” just a little or a lot faster to respond, and just a little or a lot better at remembering the specific “warning” events that trigger this lizard-brain response.

Alas, this machinery was designed to be engaged every so often when a potentially dangerous surprise arises in life. When the worry and stress are persistent, the brain experiences a kind of neurologic “burn-out” of its fight versus flight machinery.

Dangers of Nonstop Anxiety and Stress

A consistently stressed-out brain turns down its production and release of noradrenaline, and the brain becomes less attentive, less engaged. This sets the brain on the path to an anxiety (and then a depressive) disorder, and, in the longer term, to cognitive losses in memory and executive control systems, and to emotional distortions that can lead to substance abuse or other addictions.

Our political distress is but one source of persistent worry and stress. Worry is a modern plague. The head counts of individuals seeking psychiatric or psychological health are at an all-time high in the United States. Near-universal low-level stressors, such as 2 years of COVID, insecurities about the changing demands of our professional and private lives, and a deeply divided body politic are unequivocally affecting American brain health.

The brain also collaborates in our body’s response to stress. Its regulation of hormonal responses and its autonomic nervous system’s mediated responses contribute to elevated blood sugar levels, to craving high-sugar foods, to elevated blood pressure, and to weaker immune responses. This all contributes to higher risks for cardiovascular and other dietary- and immune system–related disease. And ultimately, to shorter lifespans.

Strategies to Address Neurologic Changes Arising From Chronic Stress

There are many things you can try to bring your worry back to a manageable (and even productive) level.

- Engage in a “reset” strategy several times a day to bring your amygdala and locus coeruleus back under control. It takes a minute (or five) of calm, positive meditation to take your brain to a happy, optimistic place. Or use a mindfulness exercise to quiet down that overactive amygdala.

- Talk to people. Keeping your worries to yourself can compound them. Hashing through your concerns with a family member, friend, professional coach, or therapist can help put them in perspective and may allow you to come up with strategies to identify and neurologically respond to your sources of stress.

- Exercise, both physically and mentally. Do what works for you, whether it’s a run, a long walk, pumping iron, playing racquetball — anything that promotes physical release. Exercise your brain too. Engage in a project or activity that is mentally demanding. Personally, I like to garden and do online brain exercises. There’s nothing quite like yanking out weeds or hitting a new personal best at a cognitive exercise for me to notch a sense of accomplishment to counterbalance the unresolved issues driving my worry.

- Accept the uncertainty. Life is full of uncertainty. To paraphrase from Yale theologian Reinhold Niebuhr’s “Serenity Prayer”: Have the serenity to accept what you cannot help, the courage to change what you can, and the wisdom to recognize one from the other.

And, please, be assured that you’ll make it through this election season.

Dr. Merzenich, professor emeritus, Department of Neuroscience, University of California San Francisco, disclosed ties with Posit Science. He is often credited with discovering lifelong plasticity, with being the first to harness plasticity for human benefit (in his co-invention of the cochlear implant), and for pioneering the field of plasticity-based computerized brain exercise. He is a Kavli Laureate in Neuroscience, and he has been honored by each of the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. He may be most widely known for a series of specials on the brain on public television. His current focus is BrainHQ, a brain exercise app.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Once again, America is deeply divided before a national election, with people on each side convinced of the horrors that will be visited upon us if the other side wins.

’Tis the season — and regrettably, not to be jolly but to be worried.

As a neuroscientist, I am especially aware of the deleterious mental and physical impact of chronic worry on our citizenry. That’s because worry is not “all in your head.” We modern humans live in a world of worry which appears to be progressively growing.

Flight or Fight

Worry stems from the brain’s rather remarkable ability to foresee and reflexively respond to threat. Our “fight or flight” brain machinery probably arose in our vertebrate ancestors more than 300 million years ago. The fact that we have machinery akin to that possessed by lizards or tigers or shrews is testimony to its crucial contribution to our species’ survival.

As the phrase “fight or flight” suggests, a brain that senses trouble immediately biases certain body and brain functions. As it shifts into a higher-alert mode, it increases the energy supplies in our blood and supports other changes that facilitate faster and stronger reactions, while it shuts down less essential processes which do not contribute to hiding, fighting, or running like hell.

This hyperreactive response is initiated in the amygdala in the anterior brain, which identifies “what’s happening” as immediately or potentially threatening. The now-activated amygdala generates a response in the hypothalamus that provokes an immediate increase of adrenaline and cortisol in the body, and cortisol and noradrenaline in the brain. Both sharply speed up our physical and neurologic reactivity. In the brain, that is achieved by increasing the level of excitability of neurons across the forebrain. Depending on the perceived level of threat, an excitable brain will be just a little or a lot more “on alert,” just a little or a lot faster to respond, and just a little or a lot better at remembering the specific “warning” events that trigger this lizard-brain response.

Alas, this machinery was designed to be engaged every so often when a potentially dangerous surprise arises in life. When the worry and stress are persistent, the brain experiences a kind of neurologic “burn-out” of its fight versus flight machinery.

Dangers of Nonstop Anxiety and Stress

A consistently stressed-out brain turns down its production and release of noradrenaline, and the brain becomes less attentive, less engaged. This sets the brain on the path to an anxiety (and then a depressive) disorder, and, in the longer term, to cognitive losses in memory and executive control systems, and to emotional distortions that can lead to substance abuse or other addictions.

Our political distress is but one source of persistent worry and stress. Worry is a modern plague. The head counts of individuals seeking psychiatric or psychological health are at an all-time high in the United States. Near-universal low-level stressors, such as 2 years of COVID, insecurities about the changing demands of our professional and private lives, and a deeply divided body politic are unequivocally affecting American brain health.

The brain also collaborates in our body’s response to stress. Its regulation of hormonal responses and its autonomic nervous system’s mediated responses contribute to elevated blood sugar levels, to craving high-sugar foods, to elevated blood pressure, and to weaker immune responses. This all contributes to higher risks for cardiovascular and other dietary- and immune system–related disease. And ultimately, to shorter lifespans.

Strategies to Address Neurologic Changes Arising From Chronic Stress

There are many things you can try to bring your worry back to a manageable (and even productive) level.

- Engage in a “reset” strategy several times a day to bring your amygdala and locus coeruleus back under control. It takes a minute (or five) of calm, positive meditation to take your brain to a happy, optimistic place. Or use a mindfulness exercise to quiet down that overactive amygdala.

- Talk to people. Keeping your worries to yourself can compound them. Hashing through your concerns with a family member, friend, professional coach, or therapist can help put them in perspective and may allow you to come up with strategies to identify and neurologically respond to your sources of stress.

- Exercise, both physically and mentally. Do what works for you, whether it’s a run, a long walk, pumping iron, playing racquetball — anything that promotes physical release. Exercise your brain too. Engage in a project or activity that is mentally demanding. Personally, I like to garden and do online brain exercises. There’s nothing quite like yanking out weeds or hitting a new personal best at a cognitive exercise for me to notch a sense of accomplishment to counterbalance the unresolved issues driving my worry.

- Accept the uncertainty. Life is full of uncertainty. To paraphrase from Yale theologian Reinhold Niebuhr’s “Serenity Prayer”: Have the serenity to accept what you cannot help, the courage to change what you can, and the wisdom to recognize one from the other.

And, please, be assured that you’ll make it through this election season.

Dr. Merzenich, professor emeritus, Department of Neuroscience, University of California San Francisco, disclosed ties with Posit Science. He is often credited with discovering lifelong plasticity, with being the first to harness plasticity for human benefit (in his co-invention of the cochlear implant), and for pioneering the field of plasticity-based computerized brain exercise. He is a Kavli Laureate in Neuroscience, and he has been honored by each of the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. He may be most widely known for a series of specials on the brain on public television. His current focus is BrainHQ, a brain exercise app.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Once again, America is deeply divided before a national election, with people on each side convinced of the horrors that will be visited upon us if the other side wins.

’Tis the season — and regrettably, not to be jolly but to be worried.

As a neuroscientist, I am especially aware of the deleterious mental and physical impact of chronic worry on our citizenry. That’s because worry is not “all in your head.” We modern humans live in a world of worry which appears to be progressively growing.

Flight or Fight

Worry stems from the brain’s rather remarkable ability to foresee and reflexively respond to threat. Our “fight or flight” brain machinery probably arose in our vertebrate ancestors more than 300 million years ago. The fact that we have machinery akin to that possessed by lizards or tigers or shrews is testimony to its crucial contribution to our species’ survival.

As the phrase “fight or flight” suggests, a brain that senses trouble immediately biases certain body and brain functions. As it shifts into a higher-alert mode, it increases the energy supplies in our blood and supports other changes that facilitate faster and stronger reactions, while it shuts down less essential processes which do not contribute to hiding, fighting, or running like hell.

This hyperreactive response is initiated in the amygdala in the anterior brain, which identifies “what’s happening” as immediately or potentially threatening. The now-activated amygdala generates a response in the hypothalamus that provokes an immediate increase of adrenaline and cortisol in the body, and cortisol and noradrenaline in the brain. Both sharply speed up our physical and neurologic reactivity. In the brain, that is achieved by increasing the level of excitability of neurons across the forebrain. Depending on the perceived level of threat, an excitable brain will be just a little or a lot more “on alert,” just a little or a lot faster to respond, and just a little or a lot better at remembering the specific “warning” events that trigger this lizard-brain response.

Alas, this machinery was designed to be engaged every so often when a potentially dangerous surprise arises in life. When the worry and stress are persistent, the brain experiences a kind of neurologic “burn-out” of its fight versus flight machinery.

Dangers of Nonstop Anxiety and Stress

A consistently stressed-out brain turns down its production and release of noradrenaline, and the brain becomes less attentive, less engaged. This sets the brain on the path to an anxiety (and then a depressive) disorder, and, in the longer term, to cognitive losses in memory and executive control systems, and to emotional distortions that can lead to substance abuse or other addictions.

Our political distress is but one source of persistent worry and stress. Worry is a modern plague. The head counts of individuals seeking psychiatric or psychological health are at an all-time high in the United States. Near-universal low-level stressors, such as 2 years of COVID, insecurities about the changing demands of our professional and private lives, and a deeply divided body politic are unequivocally affecting American brain health.

The brain also collaborates in our body’s response to stress. Its regulation of hormonal responses and its autonomic nervous system’s mediated responses contribute to elevated blood sugar levels, to craving high-sugar foods, to elevated blood pressure, and to weaker immune responses. This all contributes to higher risks for cardiovascular and other dietary- and immune system–related disease. And ultimately, to shorter lifespans.

Strategies to Address Neurologic Changes Arising From Chronic Stress

There are many things you can try to bring your worry back to a manageable (and even productive) level.

- Engage in a “reset” strategy several times a day to bring your amygdala and locus coeruleus back under control. It takes a minute (or five) of calm, positive meditation to take your brain to a happy, optimistic place. Or use a mindfulness exercise to quiet down that overactive amygdala.

- Talk to people. Keeping your worries to yourself can compound them. Hashing through your concerns with a family member, friend, professional coach, or therapist can help put them in perspective and may allow you to come up with strategies to identify and neurologically respond to your sources of stress.

- Exercise, both physically and mentally. Do what works for you, whether it’s a run, a long walk, pumping iron, playing racquetball — anything that promotes physical release. Exercise your brain too. Engage in a project or activity that is mentally demanding. Personally, I like to garden and do online brain exercises. There’s nothing quite like yanking out weeds or hitting a new personal best at a cognitive exercise for me to notch a sense of accomplishment to counterbalance the unresolved issues driving my worry.

- Accept the uncertainty. Life is full of uncertainty. To paraphrase from Yale theologian Reinhold Niebuhr’s “Serenity Prayer”: Have the serenity to accept what you cannot help, the courage to change what you can, and the wisdom to recognize one from the other.

And, please, be assured that you’ll make it through this election season.

Dr. Merzenich, professor emeritus, Department of Neuroscience, University of California San Francisco, disclosed ties with Posit Science. He is often credited with discovering lifelong plasticity, with being the first to harness plasticity for human benefit (in his co-invention of the cochlear implant), and for pioneering the field of plasticity-based computerized brain exercise. He is a Kavli Laureate in Neuroscience, and he has been honored by each of the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. He may be most widely known for a series of specials on the brain on public television. His current focus is BrainHQ, a brain exercise app.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

More Access to Perinatal Mental Healthcare Needed

Despite federal legislation improving healthcare access, concerted efforts are still needed to increase evidence-based treatment for maternal perinatal mental health issues, a large study of commercially insured mothers suggested. It found that federal legislation had variable and suboptimal effect on mental health services use by delivering mothers.

In the cross-sectional study, published in JAMA Network Open, psychotherapy receipt increased somewhat during 2007-2019 among all mothers and among those diagnosed with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs). The timeline encompassed periods before and after passage of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008 and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010.

The investigators, led by Kara Zivin, PhD, MS, MFA, a professor of psychiatry in the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health at Ann Arbor, found the results varied by policy and between the overall delivering population and the PMAD population. “We did not find a statistically significant immediate change associated with the MHPAEA or ACA in the overall delivering population, except for a steady increase in delivering women who received any psychotherapy after ACA,” Dr. Zivin and colleagues wrote.

The researchers looked at private insurance data for 837,316 deliveries among 716,052 women (64.2% White), ages 15-44 (mean 31.2), to assess changes in psychotherapy visits in the year before and after delivery. They also estimated per-visit out-of-pocket costs for the ACA in 2014 and the MHPAEA in 2010.

In the PMAD population, the MHPAEA was associated with an immediate increase in psychotherapy receipt of 0.72% (95% CI, 0.26%-1.18%; P = .002), followed by a sustained decrease of 0.05% (95% CI, 0.09%-0.02%; P = .001).

In both populations, the ACA was associated with immediate and sustained monthly increases in use of 0.77% (95% CI, 0.26%-1.27%; P = .003) and 0.07% (95% CI, 0.02%-0.12%; P = .005), respectively.

Post MHPAEA, both populations experienced a slight decrease in per-visit monthly out-of-pocket costs, while after the ACA they saw an immediate and steady monthly increase in these.

Although both policies expanded access to any psychotherapy, the greater number of people receiving visits coincided with fewer visits per person, the authors noted. “One hypothesis suggests that the number of available mental health clinicians may not have increased enough to meet the new demand; future research should better characterize this trend,” they wrote.

In addition, a lower standard cost per visit may have dampened the incentive to increase the number of mental health clinicians, they conjectured. These factors could explain why the PMAD group appeared to experience a decrease in the proportion receiving any psychotherapy after the MHPAEA’s implementation.

The findings should be reviewed in the context of the current mental health burden, the authors wrote, in which the shortage of mental health professionals means that less than 30% of mental healthcare needs are being met.

They called for more measures to mitigate the excess burden of PMADs.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zivin had no conflicts of interest. Coauthor Dr. Dalton reported personal fees from Merck, the Society of Family Planning, Up to Date, and The Medical Letter outside of the submitted work.

Despite federal legislation improving healthcare access, concerted efforts are still needed to increase evidence-based treatment for maternal perinatal mental health issues, a large study of commercially insured mothers suggested. It found that federal legislation had variable and suboptimal effect on mental health services use by delivering mothers.

In the cross-sectional study, published in JAMA Network Open, psychotherapy receipt increased somewhat during 2007-2019 among all mothers and among those diagnosed with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs). The timeline encompassed periods before and after passage of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008 and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010.

The investigators, led by Kara Zivin, PhD, MS, MFA, a professor of psychiatry in the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health at Ann Arbor, found the results varied by policy and between the overall delivering population and the PMAD population. “We did not find a statistically significant immediate change associated with the MHPAEA or ACA in the overall delivering population, except for a steady increase in delivering women who received any psychotherapy after ACA,” Dr. Zivin and colleagues wrote.

The researchers looked at private insurance data for 837,316 deliveries among 716,052 women (64.2% White), ages 15-44 (mean 31.2), to assess changes in psychotherapy visits in the year before and after delivery. They also estimated per-visit out-of-pocket costs for the ACA in 2014 and the MHPAEA in 2010.

In the PMAD population, the MHPAEA was associated with an immediate increase in psychotherapy receipt of 0.72% (95% CI, 0.26%-1.18%; P = .002), followed by a sustained decrease of 0.05% (95% CI, 0.09%-0.02%; P = .001).

In both populations, the ACA was associated with immediate and sustained monthly increases in use of 0.77% (95% CI, 0.26%-1.27%; P = .003) and 0.07% (95% CI, 0.02%-0.12%; P = .005), respectively.

Post MHPAEA, both populations experienced a slight decrease in per-visit monthly out-of-pocket costs, while after the ACA they saw an immediate and steady monthly increase in these.

Although both policies expanded access to any psychotherapy, the greater number of people receiving visits coincided with fewer visits per person, the authors noted. “One hypothesis suggests that the number of available mental health clinicians may not have increased enough to meet the new demand; future research should better characterize this trend,” they wrote.

In addition, a lower standard cost per visit may have dampened the incentive to increase the number of mental health clinicians, they conjectured. These factors could explain why the PMAD group appeared to experience a decrease in the proportion receiving any psychotherapy after the MHPAEA’s implementation.

The findings should be reviewed in the context of the current mental health burden, the authors wrote, in which the shortage of mental health professionals means that less than 30% of mental healthcare needs are being met.

They called for more measures to mitigate the excess burden of PMADs.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zivin had no conflicts of interest. Coauthor Dr. Dalton reported personal fees from Merck, the Society of Family Planning, Up to Date, and The Medical Letter outside of the submitted work.

Despite federal legislation improving healthcare access, concerted efforts are still needed to increase evidence-based treatment for maternal perinatal mental health issues, a large study of commercially insured mothers suggested. It found that federal legislation had variable and suboptimal effect on mental health services use by delivering mothers.

In the cross-sectional study, published in JAMA Network Open, psychotherapy receipt increased somewhat during 2007-2019 among all mothers and among those diagnosed with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs). The timeline encompassed periods before and after passage of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008 and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010.

The investigators, led by Kara Zivin, PhD, MS, MFA, a professor of psychiatry in the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health at Ann Arbor, found the results varied by policy and between the overall delivering population and the PMAD population. “We did not find a statistically significant immediate change associated with the MHPAEA or ACA in the overall delivering population, except for a steady increase in delivering women who received any psychotherapy after ACA,” Dr. Zivin and colleagues wrote.

The researchers looked at private insurance data for 837,316 deliveries among 716,052 women (64.2% White), ages 15-44 (mean 31.2), to assess changes in psychotherapy visits in the year before and after delivery. They also estimated per-visit out-of-pocket costs for the ACA in 2014 and the MHPAEA in 2010.

In the PMAD population, the MHPAEA was associated with an immediate increase in psychotherapy receipt of 0.72% (95% CI, 0.26%-1.18%; P = .002), followed by a sustained decrease of 0.05% (95% CI, 0.09%-0.02%; P = .001).

In both populations, the ACA was associated with immediate and sustained monthly increases in use of 0.77% (95% CI, 0.26%-1.27%; P = .003) and 0.07% (95% CI, 0.02%-0.12%; P = .005), respectively.

Post MHPAEA, both populations experienced a slight decrease in per-visit monthly out-of-pocket costs, while after the ACA they saw an immediate and steady monthly increase in these.

Although both policies expanded access to any psychotherapy, the greater number of people receiving visits coincided with fewer visits per person, the authors noted. “One hypothesis suggests that the number of available mental health clinicians may not have increased enough to meet the new demand; future research should better characterize this trend,” they wrote.

In addition, a lower standard cost per visit may have dampened the incentive to increase the number of mental health clinicians, they conjectured. These factors could explain why the PMAD group appeared to experience a decrease in the proportion receiving any psychotherapy after the MHPAEA’s implementation.

The findings should be reviewed in the context of the current mental health burden, the authors wrote, in which the shortage of mental health professionals means that less than 30% of mental healthcare needs are being met.

They called for more measures to mitigate the excess burden of PMADs.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zivin had no conflicts of interest. Coauthor Dr. Dalton reported personal fees from Merck, the Society of Family Planning, Up to Date, and The Medical Letter outside of the submitted work.

FROM JAMA NETWORK NEWS

How Clinicians Can Help Patients Navigate Psychedelics/Microdosing

Peter Grinspoon, MD, has some advice for clinicians when patients ask questions about microdosing of psychedelics: Keep the lines of communication open — and don’t be judgmental.

“If you’re dismissive or critical or sound like you’re judging them, then the patients just clam up,” said Dr. Grinspoon, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a primary care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

Psychedelic drugs are still illegal in the majority of states despite the growth of public interest in and use of these substances. That growth is evidenced by a flurry of workshops, reports, law enforcement seizures, and pressure by Congressional members for the Food and Drug Administration to approve new psychedelic drugs, just in the past year.

A recent study in JAMA Health Forum showed a nearly 14-fold increase in Google searches — from 7.9 to 105.6 per 10 million nationwide — for the term “microdosing” and related wording, between 2015 and 2023.

Two states — Oregon and Colorado — have decriminalized certain psychedelic drugs and are in various stages of establishing regulations and centers for prospective clients. Almost two dozen localities, like Ann Arbor, Michigan, have decriminalized psychedelic drugs. A handful of states have active legislation to decriminalize use, while others have bills that never made it out of committee.

But no definitive studies have reported that microdosing produces positive mental effects at a higher rate than placebo, according to Dr. Grinspoon. So

“We’re in this renaissance where everybody is idealizing these medications, as opposed to 20 years ago when we were in the war on drugs and everybody was dismissing them,” Dr. Grinspoon said. “The truth is somewhere in between.”

The Science

Microdosing is defined as taking doses of 1/5 to 1/20 of the conventional recreational amount, which might include a dried psilocybin mushroom, lysergic acid diethylamide, or 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. But even that much may be neither effective nor safe.

Dr. Grinspoon said clinicians should tell patients that psychedelics may cause harm, although the drugs are relatively nontoxic and are not addictive. An illegally obtained psilocybin could cause negative reactions, especially if the drug has been adulterated with other substances and if the actual dose is higher than what was indicated by the seller.

He noted that people have different reactions to psychedelics, just as they have to prescription medications. He cited one example of a woman who microdosed and could not sleep for 2 weeks afterward. Only recently have randomized, double-blinded studies begun on benefits and harms.

Researchers have also begun investigating whether long-term microdosing of psilocybin could lead to valvular heart disease (VHD), said Kevin Yang, MD, a psychiatry resident at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine. A recent review of evidence concluded that microdosing various psychedelics over a period of months can lead to drug-induced VHD.

“It’s extremely important to emphasize with patients that not only do we not know if it works or not, we also don’t really know how safe it is,” Dr. Yang said.

Dr. Yang also said clinicians should consider referring patients to a mental health professional, and especially those that may have expertise in psychedelic therapies.

One of those experts is Rachel Yehuda, PhD, director of the Center for Psychedelic Psychotherapy and Trauma Research at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. She said therapists should be able to assess the patient’s perceived need for microdosing and “invite reflections about why current approaches are falling short.”

“I would also not actively discourage it either but remain curious until both of you have a better understanding of the reasons for seeking this out and potential alternative strategies for obtaining more therapeutic benefits,” she said. “I think it is really important to study the effects of both micro- and macrodosing of psychedelics but not move in advance of the data.”

Navigating Legality

Recent ballot measures in Oregon and Colorado directed the states to develop regulated and licensed psilocybin-assisted therapy centers for legal “trips.” Oregon’s first center was opened in 2023, and Colorado is now developing its own licensing model.

According to the Oregon Health Authority, the centers are not medical facilities, and prescription or referral from a medical professional is not required.

The Oregon Academy of Family Physicians (OAFP) has yet to release guidance to clinicians on how to talk to their patients about these drugs or potential interest in visiting a licensed therapy center.

However, Betsy Boyd-Flynn, executive director of OAFP, said the organization is working on continuing medical education for what the average family physician needs to know if a patient asks about use.

“We suspect that many of our members have interest and want to learn more,” she said.

Dr. Grinspoon said clinicians should talk with patients about legality during these conversations.

“The big question I get is: ‘I really want to try microdosing, but how do I obtain the mushrooms?’ ” he said. “You can’t really as a physician tell them to do anything illegal. So you tell them to be safe, be careful, and to use their judgment.”

Patients who want to pursue microdosing who do not live in Oregon have two legal and safe options, Dr. Grinspoon said: Enroll in a clinical study or find a facility in a state or country — such as Oregon or Jamaica — that offers microdosing with psilocybin.

Clinicians also should warn their patients that the consequences of obtaining illicit psilocybin could exacerbate the mental health stresses they are seeking to alleviate.

“It’s going to get worse if they get tangled up with law enforcement or take something that’s contaminated and they get real sick,” he said.

Lisa Gillespie contributed reporting to this story. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Peter Grinspoon, MD, has some advice for clinicians when patients ask questions about microdosing of psychedelics: Keep the lines of communication open — and don’t be judgmental.

“If you’re dismissive or critical or sound like you’re judging them, then the patients just clam up,” said Dr. Grinspoon, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a primary care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

Psychedelic drugs are still illegal in the majority of states despite the growth of public interest in and use of these substances. That growth is evidenced by a flurry of workshops, reports, law enforcement seizures, and pressure by Congressional members for the Food and Drug Administration to approve new psychedelic drugs, just in the past year.

A recent study in JAMA Health Forum showed a nearly 14-fold increase in Google searches — from 7.9 to 105.6 per 10 million nationwide — for the term “microdosing” and related wording, between 2015 and 2023.

Two states — Oregon and Colorado — have decriminalized certain psychedelic drugs and are in various stages of establishing regulations and centers for prospective clients. Almost two dozen localities, like Ann Arbor, Michigan, have decriminalized psychedelic drugs. A handful of states have active legislation to decriminalize use, while others have bills that never made it out of committee.

But no definitive studies have reported that microdosing produces positive mental effects at a higher rate than placebo, according to Dr. Grinspoon. So

“We’re in this renaissance where everybody is idealizing these medications, as opposed to 20 years ago when we were in the war on drugs and everybody was dismissing them,” Dr. Grinspoon said. “The truth is somewhere in between.”

The Science

Microdosing is defined as taking doses of 1/5 to 1/20 of the conventional recreational amount, which might include a dried psilocybin mushroom, lysergic acid diethylamide, or 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. But even that much may be neither effective nor safe.

Dr. Grinspoon said clinicians should tell patients that psychedelics may cause harm, although the drugs are relatively nontoxic and are not addictive. An illegally obtained psilocybin could cause negative reactions, especially if the drug has been adulterated with other substances and if the actual dose is higher than what was indicated by the seller.

He noted that people have different reactions to psychedelics, just as they have to prescription medications. He cited one example of a woman who microdosed and could not sleep for 2 weeks afterward. Only recently have randomized, double-blinded studies begun on benefits and harms.

Researchers have also begun investigating whether long-term microdosing of psilocybin could lead to valvular heart disease (VHD), said Kevin Yang, MD, a psychiatry resident at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine. A recent review of evidence concluded that microdosing various psychedelics over a period of months can lead to drug-induced VHD.

“It’s extremely important to emphasize with patients that not only do we not know if it works or not, we also don’t really know how safe it is,” Dr. Yang said.

Dr. Yang also said clinicians should consider referring patients to a mental health professional, and especially those that may have expertise in psychedelic therapies.