User login

Uptick in adult syphilis means congenital syphilis may be lurking

While many pediatric clinicians have not frequently managed newborns of mothers with reactive syphilis serology, increased adult syphilis may change that.1

Diagnosing/managing congenital syphilis is not always clear cut. A positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titer in a newborn may not indicate congenital infection but merely may reflect transplacental, passively acquired maternal IgG from the mother’s current or previous infection rather than antibodies produced by the newborn. Because currently no IgM assay for syphilis is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for newborn testing, we must deal with IgG test results.

Often initial management decisions are needed while the infant’s status is evolving. The questions to answer to make final decisions include the following2:

- Was the mother actively infected with Treponema pallidum during pregnancy?

- If so, was the mother appropriately treated and when?

- Does the infant have any clinical, laboratory, or radiographic evidence of syphilis?

- How do the mother’s and infant’s nontreponemal serologic titers (NTT) compare at delivery using the same test?

Note: All infants assessed for congenital syphilis need a full evaluation for HIV.

Managing the infant of a mother with positive tests3,4

All such neonates need an examination for evidence of congenital syphilis. The clinical signs of congenital syphilis in neonates include nonimmune hydrops, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, rhinitis, skin rash, and pseudoparalysis of extremity. Also, consider dark-field examination or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of lesions (such as bullae) or secretions (nasal). If available, have the placenta examined histologically (silver stain) or by PCR (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–validated test). Skeletal radiographic surveys are more useful for stillborn than live born infants. (The complete algorithm can be found in Figure 3.10 of reference 4.)

Order a quantitative NTT, using the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or RPR test on neonatal serum. Umbilical cord blood is not appropriate because of potential maternal blood contamination, which could give a false-positive result, or Wharton’s jelly, which could give a false-negative result. Use of treponemal-specific tests that are used for maternal diagnosis – such as T. pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA), T. pallidum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (TP-EIA), fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, or T. pallidum chemiluminescence immunoassay (TP-CIA) – on neonatal serum is not recommended because of difficulties in interpretation.

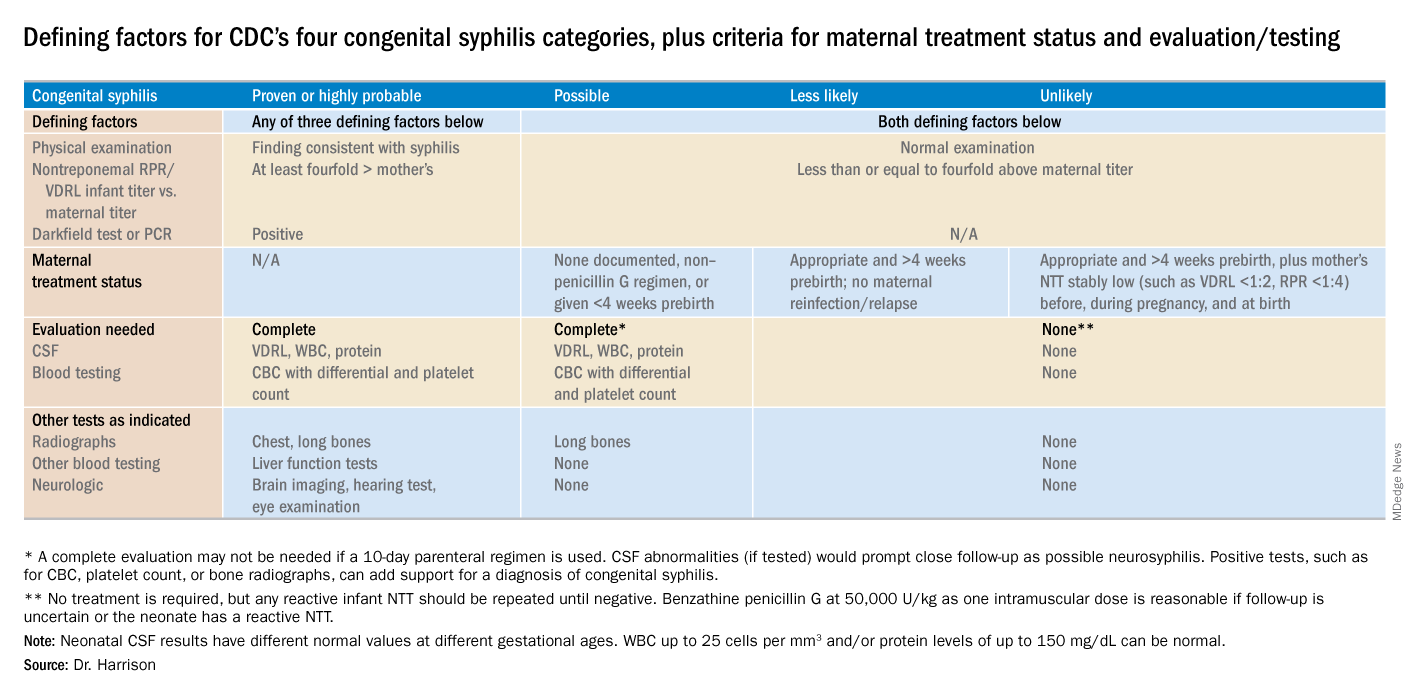

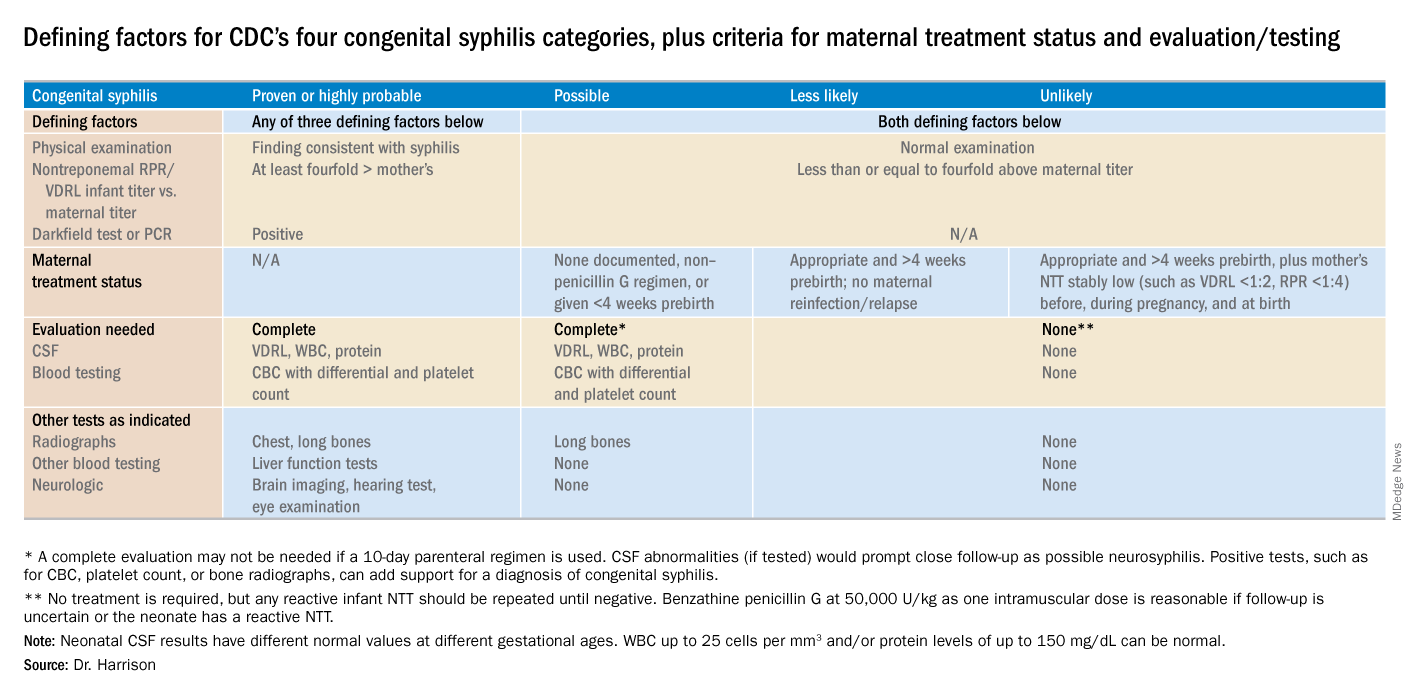

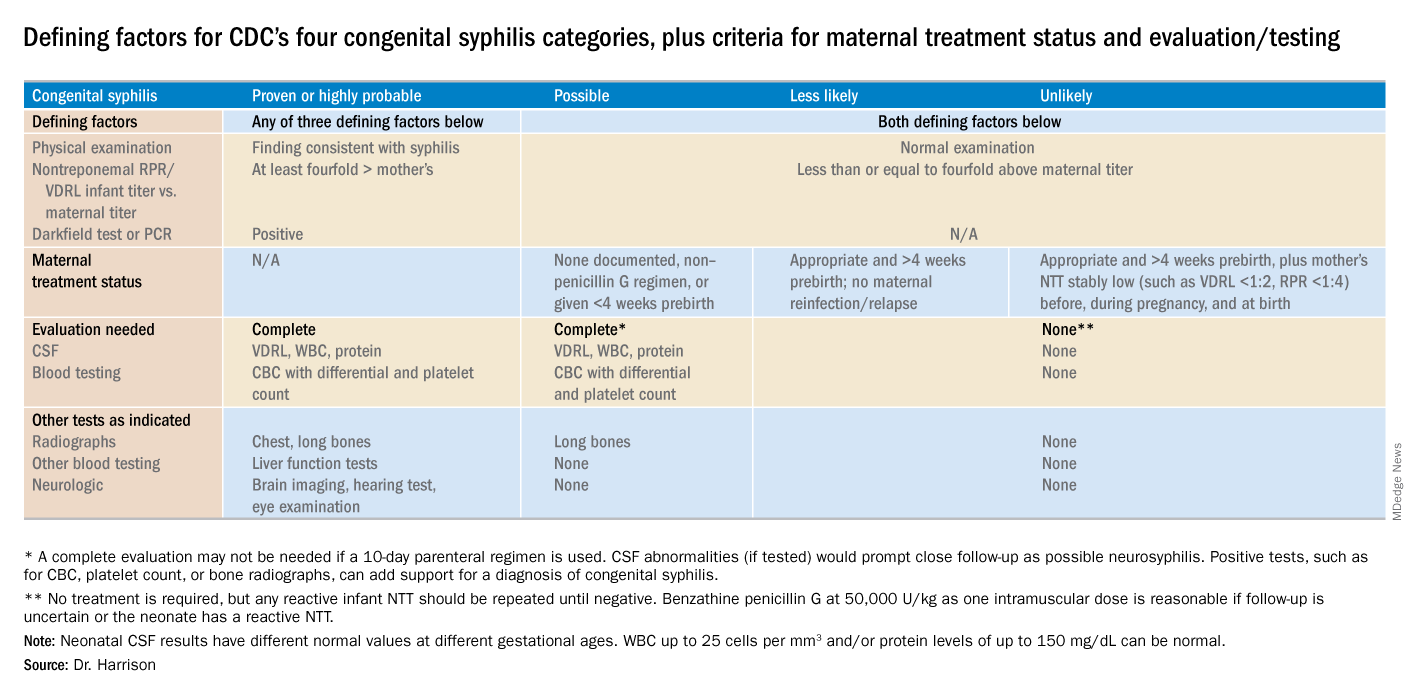

Diagnostic results allow designation of an infant into one of four CDC categories: proven/highly probable syphilis; possible syphilis; syphilis less likely; and syphilis unlikely. Treatment recommendations are based on these categories.

Proven or highly probable syphilis

There are two alternative recommended 10-day treatment regimens.

A. Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 100,000-150,000 U/kg per day by IV at 50,000 U/kg per dose, given every 12 hours through 7 days of age or every 8 hours if greater than 7 days old.

B. Procaine penicillin G at 50,000 U/kg per dose intramuscularly in one dose each day.

More than 1 day of missed therapy requires restarting a new 10-day course. Use of other antimicrobial agents (such as ampicillin) is not validated, so any empiric ampicillin initially given for possible sepsis does not count toward the 10-day penicillin regimen. If nonpenicillin drugs must be used, close serologic follow-up must occur to ensure adequacy of response to therapy.

Possible syphilis

There are three alternative regimens, the same two as in proven/highly probable syphilis (above) plus a single-dose option

A. Aqueous crystalline penicillin G, as described above.

B. Procaine penicillin G, as described above.

C. Benzathine penicillin G at 50,000 U/kg per dose intramuscularly in a single dose.

Note: To be eligible for regimen C, an infant must have a complete evaluation that is normal (cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] examination, long-bone radiographs, and complete blood count with platelet count) and follow-up must be assured. Exception: Neonates born to mothers with untreated early syphilis at the time of delivery are at increased risk for congenital syphilis, and the 10-day course of penicillin G may be considered even if the complete evaluation is normal and follow-up is certain.

Less likely syphilis

One antibiotic regimen is available, but no treatment also may be an option.

A. Benzathine penicillin G as described above.

B. If mother’s NTT has decreased at least fourfold after appropriate early syphilis therapy or remained stably low, which indicates latent syphilis (VDRL less than 1:2; RPR less than 1:4), no treatment is an option but requires repeat serology every 2-3 months until infant is 6 months old.

Unlikely syphilis

No treatment is recommended unless follow-up is uncertain, in which case it is appropriate to give the infant benzathine penicillin G as described above.

Infant with positive NTT at birth

All neonates with reactive NTT need careful follow-up examinations and repeat NTT every 2-3 months until nonreactive. NTT in infants who are not treated because of less likely or unlikely syphilis status should drop by 3 months and be nonreactive by 6 months; this indicates NTT was passively transferred maternal IgG. If NTT remains reactive at 6 months, the infant is likely infected and needs treatment. Persistent NTT at 6-12 months in treated neonates should trigger repeat CSF examination and infectious diseases consultation about a possible repeat of the 10-day penicillin G regimen. If the mother was seroreactive, but the newborn’s NTT was negative at birth, testing of the infant’s NTT needs repeating at 3 months to exclude the possibility that the congenital syphilis was incubating when prior testing occurred at birth. Note: Treponemal-specific tests are not useful in assessing treatment because detectable maternal IgG treponemal antibody can persist at least 15 months.

Neonates with abnormal CSF at birth

Repeat cerebrospinal fluid evaluation every 6 months until results normalize. Persistently reactive CSF VDRL or abnormal CSF indexes not caused by another known cause requires retreatment for possible neurosyphilis, as well as consultation with an expert.

Summary

NTT are the essential test for newborns and some degree of laboratory or imaging work up often are needed. Consider consulting an expert in infectious diseases and/or perinatology if the gray areas do not readily become clear. Treatment of the correct patients with the right drug for the right duration remains the goal, as usual.

Dr. Harrison is a professor of pediatrics at University of Missouri-Kansas City and Director of Research Affairs in the pediatric infectious diseases division at Children’s Mercy Hospital – Kansas City. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. MMWR. 2015 Nov 13;64(44);1241-5.

2. “Congenital Syphilis,” 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines.

3. “Syphilis During Pregnancy,” 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines.

4. Syphilis – Section 3: Summaries of Infectious Diseases. Red Book Online. 2018.

While many pediatric clinicians have not frequently managed newborns of mothers with reactive syphilis serology, increased adult syphilis may change that.1

Diagnosing/managing congenital syphilis is not always clear cut. A positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titer in a newborn may not indicate congenital infection but merely may reflect transplacental, passively acquired maternal IgG from the mother’s current or previous infection rather than antibodies produced by the newborn. Because currently no IgM assay for syphilis is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for newborn testing, we must deal with IgG test results.

Often initial management decisions are needed while the infant’s status is evolving. The questions to answer to make final decisions include the following2:

- Was the mother actively infected with Treponema pallidum during pregnancy?

- If so, was the mother appropriately treated and when?

- Does the infant have any clinical, laboratory, or radiographic evidence of syphilis?

- How do the mother’s and infant’s nontreponemal serologic titers (NTT) compare at delivery using the same test?

Note: All infants assessed for congenital syphilis need a full evaluation for HIV.

Managing the infant of a mother with positive tests3,4

All such neonates need an examination for evidence of congenital syphilis. The clinical signs of congenital syphilis in neonates include nonimmune hydrops, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, rhinitis, skin rash, and pseudoparalysis of extremity. Also, consider dark-field examination or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of lesions (such as bullae) or secretions (nasal). If available, have the placenta examined histologically (silver stain) or by PCR (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–validated test). Skeletal radiographic surveys are more useful for stillborn than live born infants. (The complete algorithm can be found in Figure 3.10 of reference 4.)

Order a quantitative NTT, using the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or RPR test on neonatal serum. Umbilical cord blood is not appropriate because of potential maternal blood contamination, which could give a false-positive result, or Wharton’s jelly, which could give a false-negative result. Use of treponemal-specific tests that are used for maternal diagnosis – such as T. pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA), T. pallidum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (TP-EIA), fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, or T. pallidum chemiluminescence immunoassay (TP-CIA) – on neonatal serum is not recommended because of difficulties in interpretation.

Diagnostic results allow designation of an infant into one of four CDC categories: proven/highly probable syphilis; possible syphilis; syphilis less likely; and syphilis unlikely. Treatment recommendations are based on these categories.

Proven or highly probable syphilis

There are two alternative recommended 10-day treatment regimens.

A. Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 100,000-150,000 U/kg per day by IV at 50,000 U/kg per dose, given every 12 hours through 7 days of age or every 8 hours if greater than 7 days old.

B. Procaine penicillin G at 50,000 U/kg per dose intramuscularly in one dose each day.

More than 1 day of missed therapy requires restarting a new 10-day course. Use of other antimicrobial agents (such as ampicillin) is not validated, so any empiric ampicillin initially given for possible sepsis does not count toward the 10-day penicillin regimen. If nonpenicillin drugs must be used, close serologic follow-up must occur to ensure adequacy of response to therapy.

Possible syphilis

There are three alternative regimens, the same two as in proven/highly probable syphilis (above) plus a single-dose option

A. Aqueous crystalline penicillin G, as described above.

B. Procaine penicillin G, as described above.

C. Benzathine penicillin G at 50,000 U/kg per dose intramuscularly in a single dose.

Note: To be eligible for regimen C, an infant must have a complete evaluation that is normal (cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] examination, long-bone radiographs, and complete blood count with platelet count) and follow-up must be assured. Exception: Neonates born to mothers with untreated early syphilis at the time of delivery are at increased risk for congenital syphilis, and the 10-day course of penicillin G may be considered even if the complete evaluation is normal and follow-up is certain.

Less likely syphilis

One antibiotic regimen is available, but no treatment also may be an option.

A. Benzathine penicillin G as described above.

B. If mother’s NTT has decreased at least fourfold after appropriate early syphilis therapy or remained stably low, which indicates latent syphilis (VDRL less than 1:2; RPR less than 1:4), no treatment is an option but requires repeat serology every 2-3 months until infant is 6 months old.

Unlikely syphilis

No treatment is recommended unless follow-up is uncertain, in which case it is appropriate to give the infant benzathine penicillin G as described above.

Infant with positive NTT at birth

All neonates with reactive NTT need careful follow-up examinations and repeat NTT every 2-3 months until nonreactive. NTT in infants who are not treated because of less likely or unlikely syphilis status should drop by 3 months and be nonreactive by 6 months; this indicates NTT was passively transferred maternal IgG. If NTT remains reactive at 6 months, the infant is likely infected and needs treatment. Persistent NTT at 6-12 months in treated neonates should trigger repeat CSF examination and infectious diseases consultation about a possible repeat of the 10-day penicillin G regimen. If the mother was seroreactive, but the newborn’s NTT was negative at birth, testing of the infant’s NTT needs repeating at 3 months to exclude the possibility that the congenital syphilis was incubating when prior testing occurred at birth. Note: Treponemal-specific tests are not useful in assessing treatment because detectable maternal IgG treponemal antibody can persist at least 15 months.

Neonates with abnormal CSF at birth

Repeat cerebrospinal fluid evaluation every 6 months until results normalize. Persistently reactive CSF VDRL or abnormal CSF indexes not caused by another known cause requires retreatment for possible neurosyphilis, as well as consultation with an expert.

Summary

NTT are the essential test for newborns and some degree of laboratory or imaging work up often are needed. Consider consulting an expert in infectious diseases and/or perinatology if the gray areas do not readily become clear. Treatment of the correct patients with the right drug for the right duration remains the goal, as usual.

Dr. Harrison is a professor of pediatrics at University of Missouri-Kansas City and Director of Research Affairs in the pediatric infectious diseases division at Children’s Mercy Hospital – Kansas City. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. MMWR. 2015 Nov 13;64(44);1241-5.

2. “Congenital Syphilis,” 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines.

3. “Syphilis During Pregnancy,” 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines.

4. Syphilis – Section 3: Summaries of Infectious Diseases. Red Book Online. 2018.

While many pediatric clinicians have not frequently managed newborns of mothers with reactive syphilis serology, increased adult syphilis may change that.1

Diagnosing/managing congenital syphilis is not always clear cut. A positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titer in a newborn may not indicate congenital infection but merely may reflect transplacental, passively acquired maternal IgG from the mother’s current or previous infection rather than antibodies produced by the newborn. Because currently no IgM assay for syphilis is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for newborn testing, we must deal with IgG test results.

Often initial management decisions are needed while the infant’s status is evolving. The questions to answer to make final decisions include the following2:

- Was the mother actively infected with Treponema pallidum during pregnancy?

- If so, was the mother appropriately treated and when?

- Does the infant have any clinical, laboratory, or radiographic evidence of syphilis?

- How do the mother’s and infant’s nontreponemal serologic titers (NTT) compare at delivery using the same test?

Note: All infants assessed for congenital syphilis need a full evaluation for HIV.

Managing the infant of a mother with positive tests3,4

All such neonates need an examination for evidence of congenital syphilis. The clinical signs of congenital syphilis in neonates include nonimmune hydrops, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, rhinitis, skin rash, and pseudoparalysis of extremity. Also, consider dark-field examination or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of lesions (such as bullae) or secretions (nasal). If available, have the placenta examined histologically (silver stain) or by PCR (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–validated test). Skeletal radiographic surveys are more useful for stillborn than live born infants. (The complete algorithm can be found in Figure 3.10 of reference 4.)

Order a quantitative NTT, using the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or RPR test on neonatal serum. Umbilical cord blood is not appropriate because of potential maternal blood contamination, which could give a false-positive result, or Wharton’s jelly, which could give a false-negative result. Use of treponemal-specific tests that are used for maternal diagnosis – such as T. pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA), T. pallidum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (TP-EIA), fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, or T. pallidum chemiluminescence immunoassay (TP-CIA) – on neonatal serum is not recommended because of difficulties in interpretation.

Diagnostic results allow designation of an infant into one of four CDC categories: proven/highly probable syphilis; possible syphilis; syphilis less likely; and syphilis unlikely. Treatment recommendations are based on these categories.

Proven or highly probable syphilis

There are two alternative recommended 10-day treatment regimens.

A. Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 100,000-150,000 U/kg per day by IV at 50,000 U/kg per dose, given every 12 hours through 7 days of age or every 8 hours if greater than 7 days old.

B. Procaine penicillin G at 50,000 U/kg per dose intramuscularly in one dose each day.

More than 1 day of missed therapy requires restarting a new 10-day course. Use of other antimicrobial agents (such as ampicillin) is not validated, so any empiric ampicillin initially given for possible sepsis does not count toward the 10-day penicillin regimen. If nonpenicillin drugs must be used, close serologic follow-up must occur to ensure adequacy of response to therapy.

Possible syphilis

There are three alternative regimens, the same two as in proven/highly probable syphilis (above) plus a single-dose option

A. Aqueous crystalline penicillin G, as described above.

B. Procaine penicillin G, as described above.

C. Benzathine penicillin G at 50,000 U/kg per dose intramuscularly in a single dose.

Note: To be eligible for regimen C, an infant must have a complete evaluation that is normal (cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] examination, long-bone radiographs, and complete blood count with platelet count) and follow-up must be assured. Exception: Neonates born to mothers with untreated early syphilis at the time of delivery are at increased risk for congenital syphilis, and the 10-day course of penicillin G may be considered even if the complete evaluation is normal and follow-up is certain.

Less likely syphilis

One antibiotic regimen is available, but no treatment also may be an option.

A. Benzathine penicillin G as described above.

B. If mother’s NTT has decreased at least fourfold after appropriate early syphilis therapy or remained stably low, which indicates latent syphilis (VDRL less than 1:2; RPR less than 1:4), no treatment is an option but requires repeat serology every 2-3 months until infant is 6 months old.

Unlikely syphilis

No treatment is recommended unless follow-up is uncertain, in which case it is appropriate to give the infant benzathine penicillin G as described above.

Infant with positive NTT at birth

All neonates with reactive NTT need careful follow-up examinations and repeat NTT every 2-3 months until nonreactive. NTT in infants who are not treated because of less likely or unlikely syphilis status should drop by 3 months and be nonreactive by 6 months; this indicates NTT was passively transferred maternal IgG. If NTT remains reactive at 6 months, the infant is likely infected and needs treatment. Persistent NTT at 6-12 months in treated neonates should trigger repeat CSF examination and infectious diseases consultation about a possible repeat of the 10-day penicillin G regimen. If the mother was seroreactive, but the newborn’s NTT was negative at birth, testing of the infant’s NTT needs repeating at 3 months to exclude the possibility that the congenital syphilis was incubating when prior testing occurred at birth. Note: Treponemal-specific tests are not useful in assessing treatment because detectable maternal IgG treponemal antibody can persist at least 15 months.

Neonates with abnormal CSF at birth

Repeat cerebrospinal fluid evaluation every 6 months until results normalize. Persistently reactive CSF VDRL or abnormal CSF indexes not caused by another known cause requires retreatment for possible neurosyphilis, as well as consultation with an expert.

Summary

NTT are the essential test for newborns and some degree of laboratory or imaging work up often are needed. Consider consulting an expert in infectious diseases and/or perinatology if the gray areas do not readily become clear. Treatment of the correct patients with the right drug for the right duration remains the goal, as usual.

Dr. Harrison is a professor of pediatrics at University of Missouri-Kansas City and Director of Research Affairs in the pediatric infectious diseases division at Children’s Mercy Hospital – Kansas City. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. MMWR. 2015 Nov 13;64(44);1241-5.

2. “Congenital Syphilis,” 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines.

3. “Syphilis During Pregnancy,” 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines.

4. Syphilis – Section 3: Summaries of Infectious Diseases. Red Book Online. 2018.

Responding to pseudoscience

The Internet has been a transformative means of transmitting information. Alas, the information is often not vetted, so the effects on science, truth, and health literacy have been mixed. Unfortunately, Facebook spawned a billion dollar industry that transmits gossip. Twitter distributes information based on celebrity rather than intelligence or expertise.

Listservs and Google groups have allowed small communities to form unrestricted by the physical locations of the members. A listserv for pediatric hospitalists, with 3,800 members, provides quick access to a vast body of knowledge, an extensive array of experience, and insightful clinical wisdom. Discussions on this listserv resource have inspired several of my columns, including this one. The professionalism of the listserv members ensures the accuracy of the messages. Because many of the members work nights, it is possible to post a question and receive five consults from peers, even at 1 a.m. When I first started office practice in rural areas, all I had available was my memory, Rudolph’s Pediatrics textbook, and The Harriet Lane Handbook.

Misinformation has led to vaccine hesitancy and the reemergence of diseases such as measles that had been essentially eliminated. Because people haven’t seen these diseases, they are prone to believing any critique about the risk of vaccines. More recently, parents have been refusing the vitamin K shot that is provided to all newborns to prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, now called vitamin K deficiency bleeding. The incidence of this bleeding disorder is relatively rare. However, when it occurs, the results can be disastrous, with life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeds and disabling brain hemorrhages. As with vaccine hesitancy, the corruption of scientific knowledge has led to bad outcomes that once were nearly eliminated by modern health care.

Part of being a professional is communicating in a manner that helps parents understand small risks. I compare newborn vitamin K deficiency to the risk of driving the newborn around for the first 30 days of life without a car seat. The vast majority of people will not have an accident in that time and their babies will be fine. But emergency department doctors would see so many preventable cases of injury that they would strongly advocate for car seats. I also note that if the baby has a stroke due to vitamin K deficiency, we can’t catch it early and fix it.

One issue that comes up in the nursery is whether the physician should refuse to perform a circumcision on a newborn who has not received vitamin K. The risk of bleeding is increased further when circumcisions are done as outpatient procedures a few days after birth. When this topic was discussed on the hospitalist’s listserv, most respondents took a hard line and would not perform the procedure. I am more ambivalent because of my strong personal value of accommodating diverse views and perhaps because I have never experienced a severe case of postop bleeding. The absolute risk is low.

The ethical issues are similar to those involved in maintaining or dismissing families from your practice panel if they refuse vaccines. Some physicians think the threat of having to find another doctor is the only way to appear credible when advocating the use of vaccines. Actions speak louder than words. Other physicians are dedicated to accommodating diverse viewpoints. They try to persuade over time. This is a complex subject and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ position on this changed 2 years ago to consider dismissal as a viable option as long as it adheres to relevant state laws that prohibit abandonment of patients.1

Respect for science has diminished since the era when men walked on the moon. There are myriad reasons for this. They exceed what can be covered here. All human endeavors wax and wane in their prestige and credibility. The 1960s was an era of great technological progress in many areas, including space flight and medicine. Since then, the credibility of science has been harmed by mercenary scientists who do research not to illuminate truth but to sow doubt.2 This doubt has impeded educating the public about the risks of smoking, lead paint, and climate change.

Physicians themselves have contributed to this diminished credibility of scientists. Recommendations have been published and later withdrawn in areas such as dietary cholesterol, salt, and saturated fats, estrogen replacement therapy, and screening for prostate and breast cancers. In modern America, even small inconsistencies and errors get blown up into conspiracy plots.

The era of expecting patients to blindly follow a doctor’s orders has long since passed. Parents will search the Internet for answers. The modern physician needs to guide them to good ones.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2146.

2. “Doubt is Their Product,” by David Michaels, Oxford University Press, 2008, and “Merchants of Doubt,” by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Bloomsbury Press, 2011.

The Internet has been a transformative means of transmitting information. Alas, the information is often not vetted, so the effects on science, truth, and health literacy have been mixed. Unfortunately, Facebook spawned a billion dollar industry that transmits gossip. Twitter distributes information based on celebrity rather than intelligence or expertise.

Listservs and Google groups have allowed small communities to form unrestricted by the physical locations of the members. A listserv for pediatric hospitalists, with 3,800 members, provides quick access to a vast body of knowledge, an extensive array of experience, and insightful clinical wisdom. Discussions on this listserv resource have inspired several of my columns, including this one. The professionalism of the listserv members ensures the accuracy of the messages. Because many of the members work nights, it is possible to post a question and receive five consults from peers, even at 1 a.m. When I first started office practice in rural areas, all I had available was my memory, Rudolph’s Pediatrics textbook, and The Harriet Lane Handbook.

Misinformation has led to vaccine hesitancy and the reemergence of diseases such as measles that had been essentially eliminated. Because people haven’t seen these diseases, they are prone to believing any critique about the risk of vaccines. More recently, parents have been refusing the vitamin K shot that is provided to all newborns to prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, now called vitamin K deficiency bleeding. The incidence of this bleeding disorder is relatively rare. However, when it occurs, the results can be disastrous, with life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeds and disabling brain hemorrhages. As with vaccine hesitancy, the corruption of scientific knowledge has led to bad outcomes that once were nearly eliminated by modern health care.

Part of being a professional is communicating in a manner that helps parents understand small risks. I compare newborn vitamin K deficiency to the risk of driving the newborn around for the first 30 days of life without a car seat. The vast majority of people will not have an accident in that time and their babies will be fine. But emergency department doctors would see so many preventable cases of injury that they would strongly advocate for car seats. I also note that if the baby has a stroke due to vitamin K deficiency, we can’t catch it early and fix it.

One issue that comes up in the nursery is whether the physician should refuse to perform a circumcision on a newborn who has not received vitamin K. The risk of bleeding is increased further when circumcisions are done as outpatient procedures a few days after birth. When this topic was discussed on the hospitalist’s listserv, most respondents took a hard line and would not perform the procedure. I am more ambivalent because of my strong personal value of accommodating diverse views and perhaps because I have never experienced a severe case of postop bleeding. The absolute risk is low.

The ethical issues are similar to those involved in maintaining or dismissing families from your practice panel if they refuse vaccines. Some physicians think the threat of having to find another doctor is the only way to appear credible when advocating the use of vaccines. Actions speak louder than words. Other physicians are dedicated to accommodating diverse viewpoints. They try to persuade over time. This is a complex subject and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ position on this changed 2 years ago to consider dismissal as a viable option as long as it adheres to relevant state laws that prohibit abandonment of patients.1

Respect for science has diminished since the era when men walked on the moon. There are myriad reasons for this. They exceed what can be covered here. All human endeavors wax and wane in their prestige and credibility. The 1960s was an era of great technological progress in many areas, including space flight and medicine. Since then, the credibility of science has been harmed by mercenary scientists who do research not to illuminate truth but to sow doubt.2 This doubt has impeded educating the public about the risks of smoking, lead paint, and climate change.

Physicians themselves have contributed to this diminished credibility of scientists. Recommendations have been published and later withdrawn in areas such as dietary cholesterol, salt, and saturated fats, estrogen replacement therapy, and screening for prostate and breast cancers. In modern America, even small inconsistencies and errors get blown up into conspiracy plots.

The era of expecting patients to blindly follow a doctor’s orders has long since passed. Parents will search the Internet for answers. The modern physician needs to guide them to good ones.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2146.

2. “Doubt is Their Product,” by David Michaels, Oxford University Press, 2008, and “Merchants of Doubt,” by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Bloomsbury Press, 2011.

The Internet has been a transformative means of transmitting information. Alas, the information is often not vetted, so the effects on science, truth, and health literacy have been mixed. Unfortunately, Facebook spawned a billion dollar industry that transmits gossip. Twitter distributes information based on celebrity rather than intelligence or expertise.

Listservs and Google groups have allowed small communities to form unrestricted by the physical locations of the members. A listserv for pediatric hospitalists, with 3,800 members, provides quick access to a vast body of knowledge, an extensive array of experience, and insightful clinical wisdom. Discussions on this listserv resource have inspired several of my columns, including this one. The professionalism of the listserv members ensures the accuracy of the messages. Because many of the members work nights, it is possible to post a question and receive five consults from peers, even at 1 a.m. When I first started office practice in rural areas, all I had available was my memory, Rudolph’s Pediatrics textbook, and The Harriet Lane Handbook.

Misinformation has led to vaccine hesitancy and the reemergence of diseases such as measles that had been essentially eliminated. Because people haven’t seen these diseases, they are prone to believing any critique about the risk of vaccines. More recently, parents have been refusing the vitamin K shot that is provided to all newborns to prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, now called vitamin K deficiency bleeding. The incidence of this bleeding disorder is relatively rare. However, when it occurs, the results can be disastrous, with life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeds and disabling brain hemorrhages. As with vaccine hesitancy, the corruption of scientific knowledge has led to bad outcomes that once were nearly eliminated by modern health care.

Part of being a professional is communicating in a manner that helps parents understand small risks. I compare newborn vitamin K deficiency to the risk of driving the newborn around for the first 30 days of life without a car seat. The vast majority of people will not have an accident in that time and their babies will be fine. But emergency department doctors would see so many preventable cases of injury that they would strongly advocate for car seats. I also note that if the baby has a stroke due to vitamin K deficiency, we can’t catch it early and fix it.

One issue that comes up in the nursery is whether the physician should refuse to perform a circumcision on a newborn who has not received vitamin K. The risk of bleeding is increased further when circumcisions are done as outpatient procedures a few days after birth. When this topic was discussed on the hospitalist’s listserv, most respondents took a hard line and would not perform the procedure. I am more ambivalent because of my strong personal value of accommodating diverse views and perhaps because I have never experienced a severe case of postop bleeding. The absolute risk is low.

The ethical issues are similar to those involved in maintaining or dismissing families from your practice panel if they refuse vaccines. Some physicians think the threat of having to find another doctor is the only way to appear credible when advocating the use of vaccines. Actions speak louder than words. Other physicians are dedicated to accommodating diverse viewpoints. They try to persuade over time. This is a complex subject and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ position on this changed 2 years ago to consider dismissal as a viable option as long as it adheres to relevant state laws that prohibit abandonment of patients.1

Respect for science has diminished since the era when men walked on the moon. There are myriad reasons for this. They exceed what can be covered here. All human endeavors wax and wane in their prestige and credibility. The 1960s was an era of great technological progress in many areas, including space flight and medicine. Since then, the credibility of science has been harmed by mercenary scientists who do research not to illuminate truth but to sow doubt.2 This doubt has impeded educating the public about the risks of smoking, lead paint, and climate change.

Physicians themselves have contributed to this diminished credibility of scientists. Recommendations have been published and later withdrawn in areas such as dietary cholesterol, salt, and saturated fats, estrogen replacement therapy, and screening for prostate and breast cancers. In modern America, even small inconsistencies and errors get blown up into conspiracy plots.

The era of expecting patients to blindly follow a doctor’s orders has long since passed. Parents will search the Internet for answers. The modern physician needs to guide them to good ones.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2146.

2. “Doubt is Their Product,” by David Michaels, Oxford University Press, 2008, and “Merchants of Doubt,” by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Bloomsbury Press, 2011.

Common AEDs confer modestly increased risk of major congenital malformations

NEW ORLEANS – The most commonly used antiepileptic drugs modestly increased the risk of major congenital malformations among prenatally exposed infants in the MONEAD study.

Malformations occurred among 5% of pregnancies exposed to the medications – higher than the 2% background rate – but this was still much lower than the 9%-10% rate associated with valproate.

Overall, however, the message of the Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic (MONEAD) study is quite reassuring, Kimford J. Meador, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. MONEAD is an ongoing, prospective study to determine both maternal outcomes and long-term childhood neurodevelopmental outcomes associated with the use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) during pregnancy.

“The rate of malformations was higher than I thought it would be, and higher than the 2% background rate, but it’s still a modest increase and most babies are born completely normal,” Dr. Meador, professor of neurology and neurosciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “I think the news here is good, and it’s especially reassuring when you put it in the context that, 60 years ago, there were laws that women with epilepsy couldn’t get married, and some states even had laws to sterilize women. I think that’s absurd when most infants born to these women are without malformations and the risk of miscarriage is very low.”

Another positive finding, he said, is that valproate use among pregnant women is now practically nonexistent. Only 1 of 351 pregnant women with epilepsy and just 2 of a comparator group of 109 nonpregnant women with epilepsy were taking it. That’s great news, said Dr. Meador, who also initiated the NEAD (Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs) study in the early 2000s. NEAD determined the drug’s serious teratogenic potential.

In addition to the cohorts of pregnant and nonpregnant women with epilepsy, 105 healthy pregnant women enrolled in the MONEAD study. Women will be monitored during pregnancy and postpartum to measure maternal outcomes and their children will be monitored from birth through age 6 years to measure their health and developmental outcomes.

The study has six primary outcomes, three for the women and three for their children.

- Determine if women with epilepsy have increased seizures during pregnancy and delineate the contributing factors.

- Determine if C-section rate is increased in women with epilepsy and delineate contributing factors.

- Determine if women with epilepsy have an increased risk for depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period and characterize risk factors.

- Determine the long-term effects of in utero AED exposure on verbal intellectual abilities and other neurobehavioral outcomes.

- Determine if small-for-gestational age and other adverse neonatal outcomes are increased.

- Determine if breastfeeding when taking AEDs impairs the child’s ultimate verbal and other cognitive outcomes.

Rates of miscarriage and neonatal malformations were not primary study outcomes, but the descriptive data were collected and are of high interest, Dr. Meador said.

At baseline, all the women had a mean age of about 30 years. Most (75%) were on monotherapy, 20% were on polytherapy, and the rest were not taking an AED. About 60% had focal epilepsy, 31% had generalized epilepsy, and the remainder had an unclassified seizure disorder. Three subjects had multiple seizure types. The most commonly used AEDs were lamotrigine and levetiracetam (both about 30%); 4% were taking zonisamide, 4% carbamazepine, and 4% oxcarbazepine. Topiramate was being used for 2% of the pregnant woman and 5% of the nonpregnant woman. The combination of lamotrigine and levetiracetam was used for 9.0% of pregnant and 5.5% of nonpregnant women, and other polytherapies in 12.0% of the pregnant and 14.0% of the nonpregnant woman. About 4% of the pregnant and 1% of the nonpregnant women were not taking any AED.

There were 10 (2.8%) spontaneous miscarriages among the pregnant women with epilepsy and none among the healthy pregnant women. Spontaneous miscarriages weren’t associated with acute seizures, and there were no major congenital malformations reported among them. There were also two elective abortions among the pregnant women with epilepsy.

There were 18 major congenital malformations among the pregnant woman with epilepsy (5%). A total of 14 were among pregnancies exposed to monotherapy, 3 were in polytherapy-exposed pregnancies, and 1 was in the group not taking any AEDs.

The malformations were:

- Carbamazepine (one case) – hydronephrosis.

- Gabapentin (one case) – inguinal hernia.

- Lamotrigine (five cases) – aortic coarctation, cryptorchidism, hydronephrosis, pectus excavatum, and morning glory syndrome (a funnel-shaped optic nerve disc associated with impaired visual acuity).

- Levetiracetam (five cases) – atrial septal defect, buried penis syndrome, cryptorchidism, hypoplastic aortic valve, ventricular septal defect.

- Topiramate (one case) – ventricular septal defect.

- Zonisamide (one case) – inguinal hernia, absent pinna.

- Lamotrigine plus clonazepam (one case) – cardiomyopathy.

- Lamotrigine plus levetiracetam (one case) – microcephaly, myelomeningocele, Chiari II malformation.

- Levetiracetam plus phenobarbital (one case) – bilateral inguinal hernia.

MONEAD is funded by the National Institutes of Health; Dr. Meador reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Meador KJ et al. AES 2018, Abstract 3.231.

NEW ORLEANS – The most commonly used antiepileptic drugs modestly increased the risk of major congenital malformations among prenatally exposed infants in the MONEAD study.

Malformations occurred among 5% of pregnancies exposed to the medications – higher than the 2% background rate – but this was still much lower than the 9%-10% rate associated with valproate.

Overall, however, the message of the Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic (MONEAD) study is quite reassuring, Kimford J. Meador, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. MONEAD is an ongoing, prospective study to determine both maternal outcomes and long-term childhood neurodevelopmental outcomes associated with the use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) during pregnancy.

“The rate of malformations was higher than I thought it would be, and higher than the 2% background rate, but it’s still a modest increase and most babies are born completely normal,” Dr. Meador, professor of neurology and neurosciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “I think the news here is good, and it’s especially reassuring when you put it in the context that, 60 years ago, there were laws that women with epilepsy couldn’t get married, and some states even had laws to sterilize women. I think that’s absurd when most infants born to these women are without malformations and the risk of miscarriage is very low.”

Another positive finding, he said, is that valproate use among pregnant women is now practically nonexistent. Only 1 of 351 pregnant women with epilepsy and just 2 of a comparator group of 109 nonpregnant women with epilepsy were taking it. That’s great news, said Dr. Meador, who also initiated the NEAD (Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs) study in the early 2000s. NEAD determined the drug’s serious teratogenic potential.

In addition to the cohorts of pregnant and nonpregnant women with epilepsy, 105 healthy pregnant women enrolled in the MONEAD study. Women will be monitored during pregnancy and postpartum to measure maternal outcomes and their children will be monitored from birth through age 6 years to measure their health and developmental outcomes.

The study has six primary outcomes, three for the women and three for their children.

- Determine if women with epilepsy have increased seizures during pregnancy and delineate the contributing factors.

- Determine if C-section rate is increased in women with epilepsy and delineate contributing factors.

- Determine if women with epilepsy have an increased risk for depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period and characterize risk factors.

- Determine the long-term effects of in utero AED exposure on verbal intellectual abilities and other neurobehavioral outcomes.

- Determine if small-for-gestational age and other adverse neonatal outcomes are increased.

- Determine if breastfeeding when taking AEDs impairs the child’s ultimate verbal and other cognitive outcomes.

Rates of miscarriage and neonatal malformations were not primary study outcomes, but the descriptive data were collected and are of high interest, Dr. Meador said.

At baseline, all the women had a mean age of about 30 years. Most (75%) were on monotherapy, 20% were on polytherapy, and the rest were not taking an AED. About 60% had focal epilepsy, 31% had generalized epilepsy, and the remainder had an unclassified seizure disorder. Three subjects had multiple seizure types. The most commonly used AEDs were lamotrigine and levetiracetam (both about 30%); 4% were taking zonisamide, 4% carbamazepine, and 4% oxcarbazepine. Topiramate was being used for 2% of the pregnant woman and 5% of the nonpregnant woman. The combination of lamotrigine and levetiracetam was used for 9.0% of pregnant and 5.5% of nonpregnant women, and other polytherapies in 12.0% of the pregnant and 14.0% of the nonpregnant woman. About 4% of the pregnant and 1% of the nonpregnant women were not taking any AED.

There were 10 (2.8%) spontaneous miscarriages among the pregnant women with epilepsy and none among the healthy pregnant women. Spontaneous miscarriages weren’t associated with acute seizures, and there were no major congenital malformations reported among them. There were also two elective abortions among the pregnant women with epilepsy.

There were 18 major congenital malformations among the pregnant woman with epilepsy (5%). A total of 14 were among pregnancies exposed to monotherapy, 3 were in polytherapy-exposed pregnancies, and 1 was in the group not taking any AEDs.

The malformations were:

- Carbamazepine (one case) – hydronephrosis.

- Gabapentin (one case) – inguinal hernia.

- Lamotrigine (five cases) – aortic coarctation, cryptorchidism, hydronephrosis, pectus excavatum, and morning glory syndrome (a funnel-shaped optic nerve disc associated with impaired visual acuity).

- Levetiracetam (five cases) – atrial septal defect, buried penis syndrome, cryptorchidism, hypoplastic aortic valve, ventricular septal defect.

- Topiramate (one case) – ventricular septal defect.

- Zonisamide (one case) – inguinal hernia, absent pinna.

- Lamotrigine plus clonazepam (one case) – cardiomyopathy.

- Lamotrigine plus levetiracetam (one case) – microcephaly, myelomeningocele, Chiari II malformation.

- Levetiracetam plus phenobarbital (one case) – bilateral inguinal hernia.

MONEAD is funded by the National Institutes of Health; Dr. Meador reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Meador KJ et al. AES 2018, Abstract 3.231.

NEW ORLEANS – The most commonly used antiepileptic drugs modestly increased the risk of major congenital malformations among prenatally exposed infants in the MONEAD study.

Malformations occurred among 5% of pregnancies exposed to the medications – higher than the 2% background rate – but this was still much lower than the 9%-10% rate associated with valproate.

Overall, however, the message of the Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic (MONEAD) study is quite reassuring, Kimford J. Meador, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. MONEAD is an ongoing, prospective study to determine both maternal outcomes and long-term childhood neurodevelopmental outcomes associated with the use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) during pregnancy.

“The rate of malformations was higher than I thought it would be, and higher than the 2% background rate, but it’s still a modest increase and most babies are born completely normal,” Dr. Meador, professor of neurology and neurosciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “I think the news here is good, and it’s especially reassuring when you put it in the context that, 60 years ago, there were laws that women with epilepsy couldn’t get married, and some states even had laws to sterilize women. I think that’s absurd when most infants born to these women are without malformations and the risk of miscarriage is very low.”

Another positive finding, he said, is that valproate use among pregnant women is now practically nonexistent. Only 1 of 351 pregnant women with epilepsy and just 2 of a comparator group of 109 nonpregnant women with epilepsy were taking it. That’s great news, said Dr. Meador, who also initiated the NEAD (Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs) study in the early 2000s. NEAD determined the drug’s serious teratogenic potential.

In addition to the cohorts of pregnant and nonpregnant women with epilepsy, 105 healthy pregnant women enrolled in the MONEAD study. Women will be monitored during pregnancy and postpartum to measure maternal outcomes and their children will be monitored from birth through age 6 years to measure their health and developmental outcomes.

The study has six primary outcomes, three for the women and three for their children.

- Determine if women with epilepsy have increased seizures during pregnancy and delineate the contributing factors.

- Determine if C-section rate is increased in women with epilepsy and delineate contributing factors.

- Determine if women with epilepsy have an increased risk for depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period and characterize risk factors.

- Determine the long-term effects of in utero AED exposure on verbal intellectual abilities and other neurobehavioral outcomes.

- Determine if small-for-gestational age and other adverse neonatal outcomes are increased.

- Determine if breastfeeding when taking AEDs impairs the child’s ultimate verbal and other cognitive outcomes.

Rates of miscarriage and neonatal malformations were not primary study outcomes, but the descriptive data were collected and are of high interest, Dr. Meador said.

At baseline, all the women had a mean age of about 30 years. Most (75%) were on monotherapy, 20% were on polytherapy, and the rest were not taking an AED. About 60% had focal epilepsy, 31% had generalized epilepsy, and the remainder had an unclassified seizure disorder. Three subjects had multiple seizure types. The most commonly used AEDs were lamotrigine and levetiracetam (both about 30%); 4% were taking zonisamide, 4% carbamazepine, and 4% oxcarbazepine. Topiramate was being used for 2% of the pregnant woman and 5% of the nonpregnant woman. The combination of lamotrigine and levetiracetam was used for 9.0% of pregnant and 5.5% of nonpregnant women, and other polytherapies in 12.0% of the pregnant and 14.0% of the nonpregnant woman. About 4% of the pregnant and 1% of the nonpregnant women were not taking any AED.

There were 10 (2.8%) spontaneous miscarriages among the pregnant women with epilepsy and none among the healthy pregnant women. Spontaneous miscarriages weren’t associated with acute seizures, and there were no major congenital malformations reported among them. There were also two elective abortions among the pregnant women with epilepsy.

There were 18 major congenital malformations among the pregnant woman with epilepsy (5%). A total of 14 were among pregnancies exposed to monotherapy, 3 were in polytherapy-exposed pregnancies, and 1 was in the group not taking any AEDs.

The malformations were:

- Carbamazepine (one case) – hydronephrosis.

- Gabapentin (one case) – inguinal hernia.

- Lamotrigine (five cases) – aortic coarctation, cryptorchidism, hydronephrosis, pectus excavatum, and morning glory syndrome (a funnel-shaped optic nerve disc associated with impaired visual acuity).

- Levetiracetam (five cases) – atrial septal defect, buried penis syndrome, cryptorchidism, hypoplastic aortic valve, ventricular septal defect.

- Topiramate (one case) – ventricular septal defect.

- Zonisamide (one case) – inguinal hernia, absent pinna.

- Lamotrigine plus clonazepam (one case) – cardiomyopathy.

- Lamotrigine plus levetiracetam (one case) – microcephaly, myelomeningocele, Chiari II malformation.

- Levetiracetam plus phenobarbital (one case) – bilateral inguinal hernia.

MONEAD is funded by the National Institutes of Health; Dr. Meador reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Meador KJ et al. AES 2018, Abstract 3.231.

REPORTING FROM AES 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The malformation rate was 5% in exposed pregnancies.

Study details: The MONEAD study comprised 351 pregnant women with epilepsy, 109 nonpregnant women with epilepsy, and 105 healthy pregnant women.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the study; Dr. Meador reported no financial disclosures.

Source: Meador KJ et al. AES 2018, Abstract 3.231.

Breastfeeding with MS: Good for mom, too

BERLIN – In the changing multiple sclerosis landscape, more women are having babies, and more are asking questions. With these women, what’s the best way to address the complicated interplay among pregnancy, relapse risk, breastfeeding, and medication resumption? A starting point is to recognize that “women with MS are very different today than they were 25 years ago,” said Annette Langer-Gould, MD, PhD. Not only have diagnostic criteria changed but also highly effective treatments now exist that were not available when the first pregnancy cohorts were studied, she pointed out, speaking at the annual congress of the European Committee on Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

The existing literature, said Dr. Langer-Gould, has addressed one controversy: “Most women with MS can have normal pregnancies – and breastfeed – without incurring harm,” though it’s true that severe rebound relapses are possible if natalizumab (Tysabri) or fingolimod (Gilenya) are stopped before pregnancy. In any case, new small-molecule MS medications need to be stopped during pregnancy and breastfeeding, she pointed out. “We didn’t have to worry about that too much when we only had injectables and monoclonal antibodies because they were larger and didn’t cross the placenta.”

Since the 1980s, the conversation about pregnancy and MS has moved from asking “Is pregnancy bad for women with MS?” to the current MS landscape, in which sicker women are able to become pregnant, Dr. Langer-Gould said, adding that how women with MS fare through pregnancy and in the postpartum period is changing over time as well. She and her colleagues’ experience with pregnancy in a cohort of women with MS in the Kaiser Permanente care system, where she is a clinical neurologist and regional research lead, revealed a relapse rate of 8.4%. “So it was pretty rare for a woman to have a relapse during pregnancy,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

Most women with MS who become pregnant, whether their care is received in a referral center or is community based, are now doing so while on a disease-modifying therapy (DMT), Dr. Langer-Gould said. On these highly effective treatments, “women who were too sick to get pregnant are now well controlled and having babies.”

As more women with MS become pregnant, more conversations about breastfeeding will inevitably crop up, she said. And the discussion about breastfeeding has now begun to acknowledge the “strong benefits to mom and the baby of not just breastfeeding, but longer breastfeeding,” as well.

“Because of this baby-friendly push in a lot of hospitals in the United States, where they’re trying to encourage all women to breastfeed,” a full 87% of women breastfed their infants at least some of the time, and over a third of women (35%) breastfed exclusively for at least 2 months, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“There’s no one clear explanation of why the women seem to be healthier and doing better through pregnancy as a group, but it’s probably a combination of having milder disease, breastfeeding more, and they’ve got better controlled disease before pregnancy,” she said.

At least eight studies to date have examined the relationship between postpartum MS relapses and breastfeeding, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“The thing to take away ... is that, even though we’ve studied this many, many times, no one can show that it’s harmful,” she said. For mothers who want to breastfeed, “you can support them in the breastfeeding choice, because they are not going to have more severe disease because of that.”

Whether breastfeeding is exclusive or not has not always been tracked in studies of childbearing women with MS, but when it was captured in the data, exclusive breastfeeding has exerted a protective effect, with about a 50% reduction in risk for postpartum relapse seen in one study (JAMA Neurol. 2015 Oct;72[10]:1132-8).

There is a hormonal rationale for exclusive breastfeeding exerting a protective effect on MS: With exclusive breastfeeding comes more frequent, intense suckling, with more profound elevations in prolactin, and larger drops in follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, progesterone, and estradiol. All these hormonal changes work together to produce more prolonged amenorrhea and anovulation, Dr. Langer-Gould said, with potentially beneficial immunologic effects.

When other, more general maternal and infant health benefits of breastfeeding also are taken into account, there’s strong evidence for the benefits of breastfeeding for women with MS whose medication profile allows them to breastfeed, she said.

However, the “treatment” effect of exclusive breastfeeding is only effective until the infant starts taking regular supplemental feedings, including the introduction of table food at around 6 months of age. “Once regular supplemental feedings are introduced, relapses return,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

There is some suggestion that, in women without MS, prolonged breastfeeding may be associated with reduced risk of MS. In the MS Sunshine study, breastfeeding for 15 months or longer decreased the risk of later MS by 23%-53% (Nutrients. 2018 Feb 27;10[3]:268). The investigators, led by Dr. Langer-Gould, summed the total months of breastfeeding across all children, so that the 15-month threshold could be reached by breastfeeding one child for 15 months, or three children for 5 months each. “It’s a single study; I wouldn’t make too much out of it,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

Open questions still remain, she said: “So far, no one has been able to demonstrate a clear beneficial effect in reducing the risk of postpartum relapse if they resume their DMT early in the postpartum period.” Dr. Langer-Gould noted that the literature in this area is hampered by heterogeneity and by the fact that newer, more highly active DMTs have not been well studied.

Also, the link between postpartum relapses and long-term prognosis is not completely delineated. Indirect evidence, she said, points to a postpartum relapse as being “overall, a low-impact event.”

Dr. Langer-Gould reported that she has been the site principal investigator for clinical trials sponsored by Roche and Biogen.

SOURCE: Langer-Gould A. ECTRIMS 2018, Abstract 5.

BERLIN – In the changing multiple sclerosis landscape, more women are having babies, and more are asking questions. With these women, what’s the best way to address the complicated interplay among pregnancy, relapse risk, breastfeeding, and medication resumption? A starting point is to recognize that “women with MS are very different today than they were 25 years ago,” said Annette Langer-Gould, MD, PhD. Not only have diagnostic criteria changed but also highly effective treatments now exist that were not available when the first pregnancy cohorts were studied, she pointed out, speaking at the annual congress of the European Committee on Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

The existing literature, said Dr. Langer-Gould, has addressed one controversy: “Most women with MS can have normal pregnancies – and breastfeed – without incurring harm,” though it’s true that severe rebound relapses are possible if natalizumab (Tysabri) or fingolimod (Gilenya) are stopped before pregnancy. In any case, new small-molecule MS medications need to be stopped during pregnancy and breastfeeding, she pointed out. “We didn’t have to worry about that too much when we only had injectables and monoclonal antibodies because they were larger and didn’t cross the placenta.”

Since the 1980s, the conversation about pregnancy and MS has moved from asking “Is pregnancy bad for women with MS?” to the current MS landscape, in which sicker women are able to become pregnant, Dr. Langer-Gould said, adding that how women with MS fare through pregnancy and in the postpartum period is changing over time as well. She and her colleagues’ experience with pregnancy in a cohort of women with MS in the Kaiser Permanente care system, where she is a clinical neurologist and regional research lead, revealed a relapse rate of 8.4%. “So it was pretty rare for a woman to have a relapse during pregnancy,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

Most women with MS who become pregnant, whether their care is received in a referral center or is community based, are now doing so while on a disease-modifying therapy (DMT), Dr. Langer-Gould said. On these highly effective treatments, “women who were too sick to get pregnant are now well controlled and having babies.”

As more women with MS become pregnant, more conversations about breastfeeding will inevitably crop up, she said. And the discussion about breastfeeding has now begun to acknowledge the “strong benefits to mom and the baby of not just breastfeeding, but longer breastfeeding,” as well.

“Because of this baby-friendly push in a lot of hospitals in the United States, where they’re trying to encourage all women to breastfeed,” a full 87% of women breastfed their infants at least some of the time, and over a third of women (35%) breastfed exclusively for at least 2 months, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“There’s no one clear explanation of why the women seem to be healthier and doing better through pregnancy as a group, but it’s probably a combination of having milder disease, breastfeeding more, and they’ve got better controlled disease before pregnancy,” she said.

At least eight studies to date have examined the relationship between postpartum MS relapses and breastfeeding, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“The thing to take away ... is that, even though we’ve studied this many, many times, no one can show that it’s harmful,” she said. For mothers who want to breastfeed, “you can support them in the breastfeeding choice, because they are not going to have more severe disease because of that.”

Whether breastfeeding is exclusive or not has not always been tracked in studies of childbearing women with MS, but when it was captured in the data, exclusive breastfeeding has exerted a protective effect, with about a 50% reduction in risk for postpartum relapse seen in one study (JAMA Neurol. 2015 Oct;72[10]:1132-8).

There is a hormonal rationale for exclusive breastfeeding exerting a protective effect on MS: With exclusive breastfeeding comes more frequent, intense suckling, with more profound elevations in prolactin, and larger drops in follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, progesterone, and estradiol. All these hormonal changes work together to produce more prolonged amenorrhea and anovulation, Dr. Langer-Gould said, with potentially beneficial immunologic effects.

When other, more general maternal and infant health benefits of breastfeeding also are taken into account, there’s strong evidence for the benefits of breastfeeding for women with MS whose medication profile allows them to breastfeed, she said.

However, the “treatment” effect of exclusive breastfeeding is only effective until the infant starts taking regular supplemental feedings, including the introduction of table food at around 6 months of age. “Once regular supplemental feedings are introduced, relapses return,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

There is some suggestion that, in women without MS, prolonged breastfeeding may be associated with reduced risk of MS. In the MS Sunshine study, breastfeeding for 15 months or longer decreased the risk of later MS by 23%-53% (Nutrients. 2018 Feb 27;10[3]:268). The investigators, led by Dr. Langer-Gould, summed the total months of breastfeeding across all children, so that the 15-month threshold could be reached by breastfeeding one child for 15 months, or three children for 5 months each. “It’s a single study; I wouldn’t make too much out of it,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

Open questions still remain, she said: “So far, no one has been able to demonstrate a clear beneficial effect in reducing the risk of postpartum relapse if they resume their DMT early in the postpartum period.” Dr. Langer-Gould noted that the literature in this area is hampered by heterogeneity and by the fact that newer, more highly active DMTs have not been well studied.

Also, the link between postpartum relapses and long-term prognosis is not completely delineated. Indirect evidence, she said, points to a postpartum relapse as being “overall, a low-impact event.”

Dr. Langer-Gould reported that she has been the site principal investigator for clinical trials sponsored by Roche and Biogen.

SOURCE: Langer-Gould A. ECTRIMS 2018, Abstract 5.

BERLIN – In the changing multiple sclerosis landscape, more women are having babies, and more are asking questions. With these women, what’s the best way to address the complicated interplay among pregnancy, relapse risk, breastfeeding, and medication resumption? A starting point is to recognize that “women with MS are very different today than they were 25 years ago,” said Annette Langer-Gould, MD, PhD. Not only have diagnostic criteria changed but also highly effective treatments now exist that were not available when the first pregnancy cohorts were studied, she pointed out, speaking at the annual congress of the European Committee on Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

The existing literature, said Dr. Langer-Gould, has addressed one controversy: “Most women with MS can have normal pregnancies – and breastfeed – without incurring harm,” though it’s true that severe rebound relapses are possible if natalizumab (Tysabri) or fingolimod (Gilenya) are stopped before pregnancy. In any case, new small-molecule MS medications need to be stopped during pregnancy and breastfeeding, she pointed out. “We didn’t have to worry about that too much when we only had injectables and monoclonal antibodies because they were larger and didn’t cross the placenta.”

Since the 1980s, the conversation about pregnancy and MS has moved from asking “Is pregnancy bad for women with MS?” to the current MS landscape, in which sicker women are able to become pregnant, Dr. Langer-Gould said, adding that how women with MS fare through pregnancy and in the postpartum period is changing over time as well. She and her colleagues’ experience with pregnancy in a cohort of women with MS in the Kaiser Permanente care system, where she is a clinical neurologist and regional research lead, revealed a relapse rate of 8.4%. “So it was pretty rare for a woman to have a relapse during pregnancy,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

Most women with MS who become pregnant, whether their care is received in a referral center or is community based, are now doing so while on a disease-modifying therapy (DMT), Dr. Langer-Gould said. On these highly effective treatments, “women who were too sick to get pregnant are now well controlled and having babies.”

As more women with MS become pregnant, more conversations about breastfeeding will inevitably crop up, she said. And the discussion about breastfeeding has now begun to acknowledge the “strong benefits to mom and the baby of not just breastfeeding, but longer breastfeeding,” as well.

“Because of this baby-friendly push in a lot of hospitals in the United States, where they’re trying to encourage all women to breastfeed,” a full 87% of women breastfed their infants at least some of the time, and over a third of women (35%) breastfed exclusively for at least 2 months, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“There’s no one clear explanation of why the women seem to be healthier and doing better through pregnancy as a group, but it’s probably a combination of having milder disease, breastfeeding more, and they’ve got better controlled disease before pregnancy,” she said.

At least eight studies to date have examined the relationship between postpartum MS relapses and breastfeeding, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“The thing to take away ... is that, even though we’ve studied this many, many times, no one can show that it’s harmful,” she said. For mothers who want to breastfeed, “you can support them in the breastfeeding choice, because they are not going to have more severe disease because of that.”

Whether breastfeeding is exclusive or not has not always been tracked in studies of childbearing women with MS, but when it was captured in the data, exclusive breastfeeding has exerted a protective effect, with about a 50% reduction in risk for postpartum relapse seen in one study (JAMA Neurol. 2015 Oct;72[10]:1132-8).

There is a hormonal rationale for exclusive breastfeeding exerting a protective effect on MS: With exclusive breastfeeding comes more frequent, intense suckling, with more profound elevations in prolactin, and larger drops in follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, progesterone, and estradiol. All these hormonal changes work together to produce more prolonged amenorrhea and anovulation, Dr. Langer-Gould said, with potentially beneficial immunologic effects.

When other, more general maternal and infant health benefits of breastfeeding also are taken into account, there’s strong evidence for the benefits of breastfeeding for women with MS whose medication profile allows them to breastfeed, she said.

However, the “treatment” effect of exclusive breastfeeding is only effective until the infant starts taking regular supplemental feedings, including the introduction of table food at around 6 months of age. “Once regular supplemental feedings are introduced, relapses return,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

There is some suggestion that, in women without MS, prolonged breastfeeding may be associated with reduced risk of MS. In the MS Sunshine study, breastfeeding for 15 months or longer decreased the risk of later MS by 23%-53% (Nutrients. 2018 Feb 27;10[3]:268). The investigators, led by Dr. Langer-Gould, summed the total months of breastfeeding across all children, so that the 15-month threshold could be reached by breastfeeding one child for 15 months, or three children for 5 months each. “It’s a single study; I wouldn’t make too much out of it,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

Open questions still remain, she said: “So far, no one has been able to demonstrate a clear beneficial effect in reducing the risk of postpartum relapse if they resume their DMT early in the postpartum period.” Dr. Langer-Gould noted that the literature in this area is hampered by heterogeneity and by the fact that newer, more highly active DMTs have not been well studied.

Also, the link between postpartum relapses and long-term prognosis is not completely delineated. Indirect evidence, she said, points to a postpartum relapse as being “overall, a low-impact event.”

Dr. Langer-Gould reported that she has been the site principal investigator for clinical trials sponsored by Roche and Biogen.

SOURCE: Langer-Gould A. ECTRIMS 2018, Abstract 5.

REPORTING FROM ECTRIMS 2018

Early caffeine therapy linked to improved neurologic outcomes in premature babies

Premature babies may benefit more if caffeine therapy is given within 2 days of birth, based on a retrospective observational cohort study of more than 2,000 newborns.

When caffeine was given within the first 2 days of birth, neonates had an adjusted odds ratio of significant neurodevelopmental impairment of 0.68, compared with neonates who received caffeine after 2 or more days. Further, the early-caffeine group had a 0.67 adjusted odds ratio for having cognitive scores of less than 85 on the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition, compared with the late-caffeine group. After researchers corrected for small-for-gestational-age status and other risk factors, however, early-caffeine therapy was associated with lower odds of cerebral palsy and hearing impairment only, according to the study published online in Pediatrics.

Caffeine administration should be a priority once extremely preterm neonates are stabilized, Abhay Lodha, MD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), and his coauthors wrote. “It is rather easy to organize the administration of caffeine as early as possible for Level 3 nurseries, and many units have already accomplished this. However, certain Level 2 nurseries may not have facilities available for such early administration. We do not have data that indicate the earliest that caffeine would have to be given to get maximum benefit, and thus, it should not be counted as an emergency medication yet,” they wrote.

The study examined data from 2,108 neonates born before 29 weeks of gestational age and given caffeine to treat or prevent apnea; 1,545 received the caffeine within 2 days of birth and the remaining 563 were treated with caffeine after 2 days. Data were adjusted for gestational age, sex, antenatal steroids, and SNAP-II (Score of Neonatal Acute Physiology-II) score.

The early-caffeine group had a significantly reduced odds of hearing impairment and cerebral palsy, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, patent ductus arteriosus, and severe neurologic injury. When the data were further analyzed using propensity-matched groups – which also accounted for small-for-gestational-age status – the difference in outcomes was a nonsignificant trend in favor of early caffeine.

The authors noted that the late-caffeine group contained a higher proportion of infants born at or before 24 weeks’ gestational age, and a lower proportion of infants born at 25-28 weeks’ gestational age, compared with the early-caffeine group. The infants in the early-caffeine group also had higher Apgar scores, higher median birth weight, and lower SNAP-II scores, and received a longer median duration of caffeine treatment.

Dr. Lodha and his coauthors said the reason for the differences between the early- and late-caffeine groups was unclear. “However, it could be attributable to an increased growth of dendrites and spines in neurons that is initiated by the especially prolonged use of caffeine in the early-caffeine group,” they wrote. “The other speculation is that caffeine improves cardiac output and blood pressure in infants who are relatively stable.”

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lodha A et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Dec. 5. doi. org/10.1542/peds.2018-1348.

Premature babies may benefit more if caffeine therapy is given within 2 days of birth, based on a retrospective observational cohort study of more than 2,000 newborns.

When caffeine was given within the first 2 days of birth, neonates had an adjusted odds ratio of significant neurodevelopmental impairment of 0.68, compared with neonates who received caffeine after 2 or more days. Further, the early-caffeine group had a 0.67 adjusted odds ratio for having cognitive scores of less than 85 on the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition, compared with the late-caffeine group. After researchers corrected for small-for-gestational-age status and other risk factors, however, early-caffeine therapy was associated with lower odds of cerebral palsy and hearing impairment only, according to the study published online in Pediatrics.

Caffeine administration should be a priority once extremely preterm neonates are stabilized, Abhay Lodha, MD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), and his coauthors wrote. “It is rather easy to organize the administration of caffeine as early as possible for Level 3 nurseries, and many units have already accomplished this. However, certain Level 2 nurseries may not have facilities available for such early administration. We do not have data that indicate the earliest that caffeine would have to be given to get maximum benefit, and thus, it should not be counted as an emergency medication yet,” they wrote.