User login

Maternal biologic therapy does not affect infant vaccine responses

MAUI, HAWAII – The infants of inflammatory bowel disease patients on biologic therapy during pregnancy and breastfeeding do not have a diminished response rate to the inactivated vaccines routinely given during the first 6 months of life, Uma Mahadevan, MD, said at the 2018 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Those babies are going to have detectable levels of drug on board, but they respond to vaccines just as well as infants born to mothers with IBD who were not on biologic therapy. The rates are the same, albeit lower than in the general population,” according to Dr. Mahadevan, professor of medicine and medical director of the Center for Colitis and Crohn’s Disease at the University of California, San Francisco.

Previous reports from the national registry have established that continuation of biologics in IBD patients throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding to maintain disease control poses no increased risks to the fetus in terms of rates of congenital anomalies, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, or longer-term developmental delay, compared with unexposed babies whose mothers have IBD.

Dr. Ananthakrishnan’s analysis focused on response rates to tetanus and Haemophilus influenzae B vaccines in the infants of 179 PIANO patients. Sixty-five percent of the IBD patients were on various biologic agents during pregnancy, 8% were on a thiopurine, 21% were on combination therapy, and 6% weren’t exposed to any IBD medications. Serologic studies showed that there was no difference across the four groups in terms of infant rates of protective titers in response to the vaccines. However, the 69%-84% rates of protective titers in the four groups fell short of the 90%-plus rate expected in the general population.

Live virus vaccines are contraindicated in the first 6 months of life in infants exposed to maternal biologics in utero. The only live virus vaccine given during that time frame in the United States is rotavirus, administered at months 2 and 3. Dr. Mahadevan and others recommend skipping that vaccine in babies exposed in utero to any IBD biologic other than certolizumab pegol (Cimzia), which uniquely doesn’t cross the placenta.

“That being said, infants born to 71 of our PIANO participants on anti-TNF therapy in pregnancy inadvertently got the rotavirus vaccine, and they were all just fine, even with very high drug levels,” the gastroenterologist said.

The live virus varicella and MMR vaccines can safely be given as scheduled at 1 year of age. By that time the biologics are long gone from the child.

Dr. Mahadevan reported receiving research funding from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, which sponsors the PIANO registry. She also has financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The infants of inflammatory bowel disease patients on biologic therapy during pregnancy and breastfeeding do not have a diminished response rate to the inactivated vaccines routinely given during the first 6 months of life, Uma Mahadevan, MD, said at the 2018 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Those babies are going to have detectable levels of drug on board, but they respond to vaccines just as well as infants born to mothers with IBD who were not on biologic therapy. The rates are the same, albeit lower than in the general population,” according to Dr. Mahadevan, professor of medicine and medical director of the Center for Colitis and Crohn’s Disease at the University of California, San Francisco.

Previous reports from the national registry have established that continuation of biologics in IBD patients throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding to maintain disease control poses no increased risks to the fetus in terms of rates of congenital anomalies, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, or longer-term developmental delay, compared with unexposed babies whose mothers have IBD.

Dr. Ananthakrishnan’s analysis focused on response rates to tetanus and Haemophilus influenzae B vaccines in the infants of 179 PIANO patients. Sixty-five percent of the IBD patients were on various biologic agents during pregnancy, 8% were on a thiopurine, 21% were on combination therapy, and 6% weren’t exposed to any IBD medications. Serologic studies showed that there was no difference across the four groups in terms of infant rates of protective titers in response to the vaccines. However, the 69%-84% rates of protective titers in the four groups fell short of the 90%-plus rate expected in the general population.

Live virus vaccines are contraindicated in the first 6 months of life in infants exposed to maternal biologics in utero. The only live virus vaccine given during that time frame in the United States is rotavirus, administered at months 2 and 3. Dr. Mahadevan and others recommend skipping that vaccine in babies exposed in utero to any IBD biologic other than certolizumab pegol (Cimzia), which uniquely doesn’t cross the placenta.

“That being said, infants born to 71 of our PIANO participants on anti-TNF therapy in pregnancy inadvertently got the rotavirus vaccine, and they were all just fine, even with very high drug levels,” the gastroenterologist said.

The live virus varicella and MMR vaccines can safely be given as scheduled at 1 year of age. By that time the biologics are long gone from the child.

Dr. Mahadevan reported receiving research funding from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, which sponsors the PIANO registry. She also has financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The infants of inflammatory bowel disease patients on biologic therapy during pregnancy and breastfeeding do not have a diminished response rate to the inactivated vaccines routinely given during the first 6 months of life, Uma Mahadevan, MD, said at the 2018 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Those babies are going to have detectable levels of drug on board, but they respond to vaccines just as well as infants born to mothers with IBD who were not on biologic therapy. The rates are the same, albeit lower than in the general population,” according to Dr. Mahadevan, professor of medicine and medical director of the Center for Colitis and Crohn’s Disease at the University of California, San Francisco.

Previous reports from the national registry have established that continuation of biologics in IBD patients throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding to maintain disease control poses no increased risks to the fetus in terms of rates of congenital anomalies, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, or longer-term developmental delay, compared with unexposed babies whose mothers have IBD.

Dr. Ananthakrishnan’s analysis focused on response rates to tetanus and Haemophilus influenzae B vaccines in the infants of 179 PIANO patients. Sixty-five percent of the IBD patients were on various biologic agents during pregnancy, 8% were on a thiopurine, 21% were on combination therapy, and 6% weren’t exposed to any IBD medications. Serologic studies showed that there was no difference across the four groups in terms of infant rates of protective titers in response to the vaccines. However, the 69%-84% rates of protective titers in the four groups fell short of the 90%-plus rate expected in the general population.

Live virus vaccines are contraindicated in the first 6 months of life in infants exposed to maternal biologics in utero. The only live virus vaccine given during that time frame in the United States is rotavirus, administered at months 2 and 3. Dr. Mahadevan and others recommend skipping that vaccine in babies exposed in utero to any IBD biologic other than certolizumab pegol (Cimzia), which uniquely doesn’t cross the placenta.

“That being said, infants born to 71 of our PIANO participants on anti-TNF therapy in pregnancy inadvertently got the rotavirus vaccine, and they were all just fine, even with very high drug levels,” the gastroenterologist said.

The live virus varicella and MMR vaccines can safely be given as scheduled at 1 year of age. By that time the biologics are long gone from the child.

Dr. Mahadevan reported receiving research funding from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, which sponsors the PIANO registry. She also has financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM RWCS 2018

Alternative oxygen therapy reduces treatment failure in bronchiolitis

High-flow oxygen therapy outside the ICU boosts the likelihood that infants with bronchiolitis will avoid treatment failure and an escalation of treatment, a study finds.

“High flow can be safely used in general emergency wards and general pediatric ward settings in regional and metropolitan hospitals that have no immediate direct access to dedicated pediatric intensive care facilities,” study coauthor Andreas Schibler, MD, of University of Queensland in Australia, said in an interview. The findings were published March 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The typical treatment for bronchiolitis is supportive therapy, providing nutrition, fluids, and if needed respiratory support including provision of oxygen,” Dr. Schibler said.

The prognosis is generally goods thanks to improvements in intensive care, he said, which some infants need because the standard oxygen therapy provided in general pediatric wards is insufficient. The new study examines whether high-flow oxygen therapy through a cannula – which he said has become more common – reduces the risk of treatment failure in non-ICU therapy, compared with standard oxygen treatment.

Dr. Schibler and his colleagues tracked 1,472 patients under 12 months with bronchiolitis and a need for oxygen treatment who were randomly assigned to high-flow or standard oxygen therapy to maintain their oxygen saturation at 92%-98% or 94%-98%, depending on policy at the hospital. The subjects were patients at 17 hospitals in Australia and New Zealand.

A total of 739 infants received high-flow treatment that provided heated and humidified oxygen at a rate of 2 liters per kilogram of body weight per minute. The other 733 infants received standard oxygen therapy up to a maximum 2 liters per minute.

The treatment failed, requiring an escalation of care, in 87 of 739 patients (12%) in the high-flow group and 167 of 733 (23%) in the standard-therapy group. (risk difference = –11% points; 95% confidence interval, –15 to –7; P less than .001).

“The ease to use and simplicity of high flow made us recognize and think that this level of respiratory care can be provided outside intensive care,” Dr. Schibler said. “This was further supported by the observational fact that most of these infants with bronchiolitis showed a dramatically improved respiratory condition once on high flow.”

Dr. Schibler said there haven’t been any signs of adverse effects from high-flow oxygen therapy. As for the cost of the treatment, he said it is “likely offset by a reduced need for intensive care therapy or costs associated with transferring to a children’s hospital.”

What should physicians and hospitals take from the study findings? “If a hospital explores the option to use high flow in bronchiolitis, then start the therapy early in the disease process or once an oxygen requirement is recognized,” Dr. Schibler said. “Implementation of a solid and structured training program with a clear hospital guideline based on the evidence will ensure the staff who care for these patients will be empowered and comfortable to adjust the oxygen levels given by the high-flow equipment. The greater the confidence and comfort level for the nursing and respiratory technician staff the better for these infants, as they will sooner observe those infants who are not responding well and may require a higher level of care such as intensive care or they will recognize the infant who responds well.”

The National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and the Queensland Emergency Medical Research Fund provided funding, and sites received grant funding from various sources. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, a respiratory care company based in Auckland, New Zealand, donated high-flow equipment and consumables and travel/accommodation support. Study authors reported various grants and other support.

SOURCE: Franklin D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1112-31.

High-flow oxygen therapy outside the ICU boosts the likelihood that infants with bronchiolitis will avoid treatment failure and an escalation of treatment, a study finds.

“High flow can be safely used in general emergency wards and general pediatric ward settings in regional and metropolitan hospitals that have no immediate direct access to dedicated pediatric intensive care facilities,” study coauthor Andreas Schibler, MD, of University of Queensland in Australia, said in an interview. The findings were published March 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The typical treatment for bronchiolitis is supportive therapy, providing nutrition, fluids, and if needed respiratory support including provision of oxygen,” Dr. Schibler said.

The prognosis is generally goods thanks to improvements in intensive care, he said, which some infants need because the standard oxygen therapy provided in general pediatric wards is insufficient. The new study examines whether high-flow oxygen therapy through a cannula – which he said has become more common – reduces the risk of treatment failure in non-ICU therapy, compared with standard oxygen treatment.

Dr. Schibler and his colleagues tracked 1,472 patients under 12 months with bronchiolitis and a need for oxygen treatment who were randomly assigned to high-flow or standard oxygen therapy to maintain their oxygen saturation at 92%-98% or 94%-98%, depending on policy at the hospital. The subjects were patients at 17 hospitals in Australia and New Zealand.

A total of 739 infants received high-flow treatment that provided heated and humidified oxygen at a rate of 2 liters per kilogram of body weight per minute. The other 733 infants received standard oxygen therapy up to a maximum 2 liters per minute.

The treatment failed, requiring an escalation of care, in 87 of 739 patients (12%) in the high-flow group and 167 of 733 (23%) in the standard-therapy group. (risk difference = –11% points; 95% confidence interval, –15 to –7; P less than .001).

“The ease to use and simplicity of high flow made us recognize and think that this level of respiratory care can be provided outside intensive care,” Dr. Schibler said. “This was further supported by the observational fact that most of these infants with bronchiolitis showed a dramatically improved respiratory condition once on high flow.”

Dr. Schibler said there haven’t been any signs of adverse effects from high-flow oxygen therapy. As for the cost of the treatment, he said it is “likely offset by a reduced need for intensive care therapy or costs associated with transferring to a children’s hospital.”

What should physicians and hospitals take from the study findings? “If a hospital explores the option to use high flow in bronchiolitis, then start the therapy early in the disease process or once an oxygen requirement is recognized,” Dr. Schibler said. “Implementation of a solid and structured training program with a clear hospital guideline based on the evidence will ensure the staff who care for these patients will be empowered and comfortable to adjust the oxygen levels given by the high-flow equipment. The greater the confidence and comfort level for the nursing and respiratory technician staff the better for these infants, as they will sooner observe those infants who are not responding well and may require a higher level of care such as intensive care or they will recognize the infant who responds well.”

The National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and the Queensland Emergency Medical Research Fund provided funding, and sites received grant funding from various sources. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, a respiratory care company based in Auckland, New Zealand, donated high-flow equipment and consumables and travel/accommodation support. Study authors reported various grants and other support.

SOURCE: Franklin D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1112-31.

High-flow oxygen therapy outside the ICU boosts the likelihood that infants with bronchiolitis will avoid treatment failure and an escalation of treatment, a study finds.

“High flow can be safely used in general emergency wards and general pediatric ward settings in regional and metropolitan hospitals that have no immediate direct access to dedicated pediatric intensive care facilities,” study coauthor Andreas Schibler, MD, of University of Queensland in Australia, said in an interview. The findings were published March 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The typical treatment for bronchiolitis is supportive therapy, providing nutrition, fluids, and if needed respiratory support including provision of oxygen,” Dr. Schibler said.

The prognosis is generally goods thanks to improvements in intensive care, he said, which some infants need because the standard oxygen therapy provided in general pediatric wards is insufficient. The new study examines whether high-flow oxygen therapy through a cannula – which he said has become more common – reduces the risk of treatment failure in non-ICU therapy, compared with standard oxygen treatment.

Dr. Schibler and his colleagues tracked 1,472 patients under 12 months with bronchiolitis and a need for oxygen treatment who were randomly assigned to high-flow or standard oxygen therapy to maintain their oxygen saturation at 92%-98% or 94%-98%, depending on policy at the hospital. The subjects were patients at 17 hospitals in Australia and New Zealand.

A total of 739 infants received high-flow treatment that provided heated and humidified oxygen at a rate of 2 liters per kilogram of body weight per minute. The other 733 infants received standard oxygen therapy up to a maximum 2 liters per minute.

The treatment failed, requiring an escalation of care, in 87 of 739 patients (12%) in the high-flow group and 167 of 733 (23%) in the standard-therapy group. (risk difference = –11% points; 95% confidence interval, –15 to –7; P less than .001).

“The ease to use and simplicity of high flow made us recognize and think that this level of respiratory care can be provided outside intensive care,” Dr. Schibler said. “This was further supported by the observational fact that most of these infants with bronchiolitis showed a dramatically improved respiratory condition once on high flow.”

Dr. Schibler said there haven’t been any signs of adverse effects from high-flow oxygen therapy. As for the cost of the treatment, he said it is “likely offset by a reduced need for intensive care therapy or costs associated with transferring to a children’s hospital.”

What should physicians and hospitals take from the study findings? “If a hospital explores the option to use high flow in bronchiolitis, then start the therapy early in the disease process or once an oxygen requirement is recognized,” Dr. Schibler said. “Implementation of a solid and structured training program with a clear hospital guideline based on the evidence will ensure the staff who care for these patients will be empowered and comfortable to adjust the oxygen levels given by the high-flow equipment. The greater the confidence and comfort level for the nursing and respiratory technician staff the better for these infants, as they will sooner observe those infants who are not responding well and may require a higher level of care such as intensive care or they will recognize the infant who responds well.”

The National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and the Queensland Emergency Medical Research Fund provided funding, and sites received grant funding from various sources. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, a respiratory care company based in Auckland, New Zealand, donated high-flow equipment and consumables and travel/accommodation support. Study authors reported various grants and other support.

SOURCE: Franklin D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1112-31.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: In non-ICUs, infants under 12 months with bronchiolitis are less likely to fail treatment if they are given high-flow oxygen therapy instead of standard oxygen therapy.

Major finding: Treatment failure occurred in 8 of 739 (12%) patients in the high-flow oxygen therapy group and 167 of 733 (23%) in the standard-therapy group.

Study details: Multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of 1,472 infants.

Disclosures: The National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and the Queensland Emergency Medical Research Fund provided funding, and sites received grant funding from various sources. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, a respiratory care company based in Auckland, New Zealand, donated high-flow equipment/consumables and travel/accommodation support. Study authors reported various grants and other support.

Source: Franklin D et al. N Engl J Med 2018;378(12):1112-31.

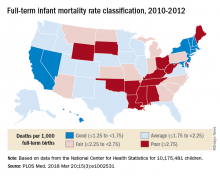

Full-term infant mortality: United States versus Europe

according to Neha Bairoliya, PhD, and Günther Fink, PhD.

The United States had an FTIMR of 2.19 per 1,000 full-term live births for that 3-year period, compared with a median of 1.11 for Austria, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, said Dr. Bairoliya of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Cambridge, Mass., and Dr. Fink of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland.

A classification system for individual states that rated FTIMR scores from poor (greater than or equal to 2.75) to excellent (greater than 1.25) put Connecticut, with a U.S.–low rate of 1.29 per 1,000 births, in the good (greater than or equal to1.25 to 1.75) category, so no state managed to join the excellent group of European countries, whose highest rate was 1.24, they reported in PLOS Medicine.

Missouri’s FTIMR of 3.77 per 1,000 was the highest among the 50 states. Along with Missouri, 12 other states were classified as poor, while 11 were considered fair (less than or equal to 2.25 to less than 2.75), 16 were average (less than or equal to 1.25 to less than 1.75), and 10 states earned a classification of good, the investigators said.

They used National Center for Health Statistics data for 7,431 deaths among 10,175,481 children born full term – defined as 37-42 weeks’ gestation – between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2012. Data on European births came from the Euro-Peristat database.

Data for preterm births put the United States in a somewhat better light: For births from 32 to 36 weeks, mortality rates were 8.24 per 1,000 in the United States and 8.25 for the six European countries; for births at 24-27 weeks, the rates were 199 in the United States and 213 for the Euro six, Dr. Bairoliya and Dr. Fink said.

The investigators did not receive any specific funding for the study, and they said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bairoliya N, Fink G. PLOS Med. 2018 Mar 20;15(3):e1002531.

according to Neha Bairoliya, PhD, and Günther Fink, PhD.

The United States had an FTIMR of 2.19 per 1,000 full-term live births for that 3-year period, compared with a median of 1.11 for Austria, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, said Dr. Bairoliya of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Cambridge, Mass., and Dr. Fink of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland.

A classification system for individual states that rated FTIMR scores from poor (greater than or equal to 2.75) to excellent (greater than 1.25) put Connecticut, with a U.S.–low rate of 1.29 per 1,000 births, in the good (greater than or equal to1.25 to 1.75) category, so no state managed to join the excellent group of European countries, whose highest rate was 1.24, they reported in PLOS Medicine.

Missouri’s FTIMR of 3.77 per 1,000 was the highest among the 50 states. Along with Missouri, 12 other states were classified as poor, while 11 were considered fair (less than or equal to 2.25 to less than 2.75), 16 were average (less than or equal to 1.25 to less than 1.75), and 10 states earned a classification of good, the investigators said.

They used National Center for Health Statistics data for 7,431 deaths among 10,175,481 children born full term – defined as 37-42 weeks’ gestation – between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2012. Data on European births came from the Euro-Peristat database.

Data for preterm births put the United States in a somewhat better light: For births from 32 to 36 weeks, mortality rates were 8.24 per 1,000 in the United States and 8.25 for the six European countries; for births at 24-27 weeks, the rates were 199 in the United States and 213 for the Euro six, Dr. Bairoliya and Dr. Fink said.

The investigators did not receive any specific funding for the study, and they said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bairoliya N, Fink G. PLOS Med. 2018 Mar 20;15(3):e1002531.

according to Neha Bairoliya, PhD, and Günther Fink, PhD.

The United States had an FTIMR of 2.19 per 1,000 full-term live births for that 3-year period, compared with a median of 1.11 for Austria, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, said Dr. Bairoliya of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Cambridge, Mass., and Dr. Fink of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland.

A classification system for individual states that rated FTIMR scores from poor (greater than or equal to 2.75) to excellent (greater than 1.25) put Connecticut, with a U.S.–low rate of 1.29 per 1,000 births, in the good (greater than or equal to1.25 to 1.75) category, so no state managed to join the excellent group of European countries, whose highest rate was 1.24, they reported in PLOS Medicine.

Missouri’s FTIMR of 3.77 per 1,000 was the highest among the 50 states. Along with Missouri, 12 other states were classified as poor, while 11 were considered fair (less than or equal to 2.25 to less than 2.75), 16 were average (less than or equal to 1.25 to less than 1.75), and 10 states earned a classification of good, the investigators said.

They used National Center for Health Statistics data for 7,431 deaths among 10,175,481 children born full term – defined as 37-42 weeks’ gestation – between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2012. Data on European births came from the Euro-Peristat database.

Data for preterm births put the United States in a somewhat better light: For births from 32 to 36 weeks, mortality rates were 8.24 per 1,000 in the United States and 8.25 for the six European countries; for births at 24-27 weeks, the rates were 199 in the United States and 213 for the Euro six, Dr. Bairoliya and Dr. Fink said.

The investigators did not receive any specific funding for the study, and they said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bairoliya N, Fink G. PLOS Med. 2018 Mar 20;15(3):e1002531.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Toxicology reveals worse maternal and fetal outcomes with teen marijuana use

DALLAS – . Also, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were higher in marijuana users, according to a study that incorporated universal urine toxicology testing of adolescents.

The study compared maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes in 211 marijuana-exposed with 995 unexposed pregnancies. Christina Rodriguez, MD, and her coinvestigators found that the risk of a composite adverse pregnancy outcome was higher in marijuana users, occurring in 97/211 marijuana users (46%), and in 337/995 (33.9%) of the non–marijuana users (P less than .001).

Dr. Rodriguez said that since it used biological samples to confirm marijuana exposure, the study helps fill a gap in the literature. She presented the retrospective cohort study at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Previous work, she said, had established that up to 70% of pregnant women who had positive tests for tetrahydrocannabinol also denied marijuana use. “If marijuana use is determined by self-report, some women are misclassified as nonusers,” making it difficult to ascertain the true association between marijuana use during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, said Dr. Rodriguez of the University of Colorado, Denver.

Whether marijuana is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes is an increasingly pressing question given rapidly shifting legislation, said Dr. Rodriguez. “In a state with legal access to marijuana, use is common in adolescent pregnancies,” she said.

Participants who were enrolled in prenatal care through the University of Colorado’s adolescent maternity program, where Dr. Rodriguez is a fellow, and who delivered at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora, were eligible to participate; adolescents were excluded for multiple gestation and for known major fetal anomalies or aneuploidy.

In addition to urine toxicology testing, participants also completed a uniformly administered substance use questionnaire. Marijuana exposure was defined as either having a positive urine toxicology result or self-reported marijuana use on the questionnaire (or both). Of the marijuana-exposed pregnancies, 133 (63%) of the adolescents tested positive on urine toxicology, 18 (9%) were positive by self-report, and 60 (28%) had both positive marijuana urine toxicology and positive self-report. Toxicology was available for 91% of participants.

Participants were negative for marijuana exposure if they had a negative toxicology screen, regardless of their response on the substance-use questionnaire.

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including stillbirth, defined as Apgar score of 0; any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count); preterm birth, defined as spontaneous delivery before 37 weeks gestation; and infants born small for gestational age, defined as a birth weight below the 10th percentile after adjustment for gestational age and sex.

Secondary outcomes included pregnancy outcomes including placental abruption, mode of delivery, and gestational age at delivery. Neonatal outcomes included weight, length, and head circumference at birth, and neonatal intensive care unit admission. An Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes was considered an adverse neonatal outcome.

The sample size was determined by an estimate drawn from previous chart abstraction that the composite outcome would be seen in 16% of the clinic’s non–marijuana exposed patients, and 24% of the marijuana-exposed patients. The investigators also factored in that 18% of adolescents in the clinic database were marijuana users.

Dr. Rodriguez and her collaborators used a variety of models for statistical analysis, some of which included self-report alone or in conjunction with urine toxicology. In the end, they found that significant associations between their composite endpoint and marijuana use were seen when patients were dichotomized into those who had at least one positive urine toxicology test, versus those who had no positive toxicology results.

One of the study limitations was that the study didn’t permit investigators to get accurate information about the quantity, timing, or route of marijuana dosing. Also, this methodology may primarily identify heavier marijuana users, said Dr. Rodriguez.

Tobacco use was determined only by self-report, and outcomes were followed over a relatively short period of time.

Still, said Dr. Rodriguez, the study had many strengths, including the use of biological sampling to determine exposure and the near-universal participant urine toxicology testing. The investigators were able to capture and account for many important factors that could confound the results, she said. “Uncertainty regarding the impact of [marijuana] on pregnancy outcomes in the literature may result from incomplete ascertainment of exposure,” she and her coinvestigators wrote in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

SOURCE: Rodriguez C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S37.

DALLAS – . Also, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were higher in marijuana users, according to a study that incorporated universal urine toxicology testing of adolescents.

The study compared maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes in 211 marijuana-exposed with 995 unexposed pregnancies. Christina Rodriguez, MD, and her coinvestigators found that the risk of a composite adverse pregnancy outcome was higher in marijuana users, occurring in 97/211 marijuana users (46%), and in 337/995 (33.9%) of the non–marijuana users (P less than .001).

Dr. Rodriguez said that since it used biological samples to confirm marijuana exposure, the study helps fill a gap in the literature. She presented the retrospective cohort study at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Previous work, she said, had established that up to 70% of pregnant women who had positive tests for tetrahydrocannabinol also denied marijuana use. “If marijuana use is determined by self-report, some women are misclassified as nonusers,” making it difficult to ascertain the true association between marijuana use during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, said Dr. Rodriguez of the University of Colorado, Denver.

Whether marijuana is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes is an increasingly pressing question given rapidly shifting legislation, said Dr. Rodriguez. “In a state with legal access to marijuana, use is common in adolescent pregnancies,” she said.

Participants who were enrolled in prenatal care through the University of Colorado’s adolescent maternity program, where Dr. Rodriguez is a fellow, and who delivered at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora, were eligible to participate; adolescents were excluded for multiple gestation and for known major fetal anomalies or aneuploidy.

In addition to urine toxicology testing, participants also completed a uniformly administered substance use questionnaire. Marijuana exposure was defined as either having a positive urine toxicology result or self-reported marijuana use on the questionnaire (or both). Of the marijuana-exposed pregnancies, 133 (63%) of the adolescents tested positive on urine toxicology, 18 (9%) were positive by self-report, and 60 (28%) had both positive marijuana urine toxicology and positive self-report. Toxicology was available for 91% of participants.

Participants were negative for marijuana exposure if they had a negative toxicology screen, regardless of their response on the substance-use questionnaire.

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including stillbirth, defined as Apgar score of 0; any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count); preterm birth, defined as spontaneous delivery before 37 weeks gestation; and infants born small for gestational age, defined as a birth weight below the 10th percentile after adjustment for gestational age and sex.

Secondary outcomes included pregnancy outcomes including placental abruption, mode of delivery, and gestational age at delivery. Neonatal outcomes included weight, length, and head circumference at birth, and neonatal intensive care unit admission. An Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes was considered an adverse neonatal outcome.

The sample size was determined by an estimate drawn from previous chart abstraction that the composite outcome would be seen in 16% of the clinic’s non–marijuana exposed patients, and 24% of the marijuana-exposed patients. The investigators also factored in that 18% of adolescents in the clinic database were marijuana users.

Dr. Rodriguez and her collaborators used a variety of models for statistical analysis, some of which included self-report alone or in conjunction with urine toxicology. In the end, they found that significant associations between their composite endpoint and marijuana use were seen when patients were dichotomized into those who had at least one positive urine toxicology test, versus those who had no positive toxicology results.

One of the study limitations was that the study didn’t permit investigators to get accurate information about the quantity, timing, or route of marijuana dosing. Also, this methodology may primarily identify heavier marijuana users, said Dr. Rodriguez.

Tobacco use was determined only by self-report, and outcomes were followed over a relatively short period of time.

Still, said Dr. Rodriguez, the study had many strengths, including the use of biological sampling to determine exposure and the near-universal participant urine toxicology testing. The investigators were able to capture and account for many important factors that could confound the results, she said. “Uncertainty regarding the impact of [marijuana] on pregnancy outcomes in the literature may result from incomplete ascertainment of exposure,” she and her coinvestigators wrote in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

SOURCE: Rodriguez C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S37.

DALLAS – . Also, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were higher in marijuana users, according to a study that incorporated universal urine toxicology testing of adolescents.

The study compared maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes in 211 marijuana-exposed with 995 unexposed pregnancies. Christina Rodriguez, MD, and her coinvestigators found that the risk of a composite adverse pregnancy outcome was higher in marijuana users, occurring in 97/211 marijuana users (46%), and in 337/995 (33.9%) of the non–marijuana users (P less than .001).

Dr. Rodriguez said that since it used biological samples to confirm marijuana exposure, the study helps fill a gap in the literature. She presented the retrospective cohort study at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Previous work, she said, had established that up to 70% of pregnant women who had positive tests for tetrahydrocannabinol also denied marijuana use. “If marijuana use is determined by self-report, some women are misclassified as nonusers,” making it difficult to ascertain the true association between marijuana use during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, said Dr. Rodriguez of the University of Colorado, Denver.

Whether marijuana is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes is an increasingly pressing question given rapidly shifting legislation, said Dr. Rodriguez. “In a state with legal access to marijuana, use is common in adolescent pregnancies,” she said.

Participants who were enrolled in prenatal care through the University of Colorado’s adolescent maternity program, where Dr. Rodriguez is a fellow, and who delivered at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora, were eligible to participate; adolescents were excluded for multiple gestation and for known major fetal anomalies or aneuploidy.

In addition to urine toxicology testing, participants also completed a uniformly administered substance use questionnaire. Marijuana exposure was defined as either having a positive urine toxicology result or self-reported marijuana use on the questionnaire (or both). Of the marijuana-exposed pregnancies, 133 (63%) of the adolescents tested positive on urine toxicology, 18 (9%) were positive by self-report, and 60 (28%) had both positive marijuana urine toxicology and positive self-report. Toxicology was available for 91% of participants.

Participants were negative for marijuana exposure if they had a negative toxicology screen, regardless of their response on the substance-use questionnaire.

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including stillbirth, defined as Apgar score of 0; any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count); preterm birth, defined as spontaneous delivery before 37 weeks gestation; and infants born small for gestational age, defined as a birth weight below the 10th percentile after adjustment for gestational age and sex.

Secondary outcomes included pregnancy outcomes including placental abruption, mode of delivery, and gestational age at delivery. Neonatal outcomes included weight, length, and head circumference at birth, and neonatal intensive care unit admission. An Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes was considered an adverse neonatal outcome.

The sample size was determined by an estimate drawn from previous chart abstraction that the composite outcome would be seen in 16% of the clinic’s non–marijuana exposed patients, and 24% of the marijuana-exposed patients. The investigators also factored in that 18% of adolescents in the clinic database were marijuana users.

Dr. Rodriguez and her collaborators used a variety of models for statistical analysis, some of which included self-report alone or in conjunction with urine toxicology. In the end, they found that significant associations between their composite endpoint and marijuana use were seen when patients were dichotomized into those who had at least one positive urine toxicology test, versus those who had no positive toxicology results.

One of the study limitations was that the study didn’t permit investigators to get accurate information about the quantity, timing, or route of marijuana dosing. Also, this methodology may primarily identify heavier marijuana users, said Dr. Rodriguez.

Tobacco use was determined only by self-report, and outcomes were followed over a relatively short period of time.

Still, said Dr. Rodriguez, the study had many strengths, including the use of biological sampling to determine exposure and the near-universal participant urine toxicology testing. The investigators were able to capture and account for many important factors that could confound the results, she said. “Uncertainty regarding the impact of [marijuana] on pregnancy outcomes in the literature may result from incomplete ascertainment of exposure,” she and her coinvestigators wrote in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

SOURCE: Rodriguez C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S37.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Maternal and fetal outcomes were worse when marijuana use was detected by urine toxicology.

Major finding: A composite adverse outcome occurred in 46% of adolescent marijuana users, compared with 34% of non–marijuana users (P less than .001).

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of participants in an adolescent maternity clinic.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Rodriguez C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S37.

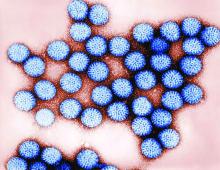

Newborn oral rotavirus vaccine held effective

A new oral rotavirus vaccine administered within the first few days of life appears effective against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in newborns, a study has found.

Julie E. Bines, MD, from the RV3 Rotavirus Vaccine Program at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, and her coauthors reported the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial in 1,513 healthy newborns in Indonesia. Participants were randomized to three doses of oral human neonatal rotavirus vaccine either on a neonatal schedule (0-5 days, 8-10 weeks, and 14-16 weeks of age) or an infant schedule (8-10 weeks, 14-16 weeks, and 18-20 weeks of age), or the equivalent schedules of placebo.

That efficacy was 77% in those who received the doses on the infant schedule.

Overall, severe rotavirus gastroenteritis was reported in 5.6% of the placebo group, compared with 2.1% of the combined vaccine group. The time from randomization to first episode of gastroenteritis was significantly longer among participants who received the vaccine, compared with those who received placebo.

“The use of a neonatal dose was investigated in the early phase of development of the rotavirus vaccine but was not pursued because of concerns regarding inadequate immune responses and safety,” wrote Dr. Bines and her associates

They noted that the results of this trial compared favorably with the efficacy of licensed vaccines in similar low-income countries that experienced a high burden of rotavirus disease.

The rates of severe adverse events were similar across all the trial groups. There were no episodes of intussusception seen within the 21-day risk period after immunization, either in the vaccine or placebo groups. However, there was one episode of intussusception in a child on the infant schedule group, which occurred 114 days after the third dose of the vaccine.

“Because intussusception is rare in newborns, the administration of a rotavirus vaccine at the time of birth may offer a safety advantage,” Dr. Bines and her associates said.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, PT Bio Farma, and the Victorian government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Authors declared fees, grants, and institutional support from the study sponsors, and three authors also declared a stake in the patent of the RV3-BB vaccine, which is licensed to PT Bio Farma.

SOURCE: Bines JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:719-30.

A new oral rotavirus vaccine administered within the first few days of life appears effective against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in newborns, a study has found.

Julie E. Bines, MD, from the RV3 Rotavirus Vaccine Program at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, and her coauthors reported the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial in 1,513 healthy newborns in Indonesia. Participants were randomized to three doses of oral human neonatal rotavirus vaccine either on a neonatal schedule (0-5 days, 8-10 weeks, and 14-16 weeks of age) or an infant schedule (8-10 weeks, 14-16 weeks, and 18-20 weeks of age), or the equivalent schedules of placebo.

That efficacy was 77% in those who received the doses on the infant schedule.

Overall, severe rotavirus gastroenteritis was reported in 5.6% of the placebo group, compared with 2.1% of the combined vaccine group. The time from randomization to first episode of gastroenteritis was significantly longer among participants who received the vaccine, compared with those who received placebo.

“The use of a neonatal dose was investigated in the early phase of development of the rotavirus vaccine but was not pursued because of concerns regarding inadequate immune responses and safety,” wrote Dr. Bines and her associates

They noted that the results of this trial compared favorably with the efficacy of licensed vaccines in similar low-income countries that experienced a high burden of rotavirus disease.

The rates of severe adverse events were similar across all the trial groups. There were no episodes of intussusception seen within the 21-day risk period after immunization, either in the vaccine or placebo groups. However, there was one episode of intussusception in a child on the infant schedule group, which occurred 114 days after the third dose of the vaccine.

“Because intussusception is rare in newborns, the administration of a rotavirus vaccine at the time of birth may offer a safety advantage,” Dr. Bines and her associates said.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, PT Bio Farma, and the Victorian government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Authors declared fees, grants, and institutional support from the study sponsors, and three authors also declared a stake in the patent of the RV3-BB vaccine, which is licensed to PT Bio Farma.

SOURCE: Bines JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:719-30.

A new oral rotavirus vaccine administered within the first few days of life appears effective against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in newborns, a study has found.

Julie E. Bines, MD, from the RV3 Rotavirus Vaccine Program at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, and her coauthors reported the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial in 1,513 healthy newborns in Indonesia. Participants were randomized to three doses of oral human neonatal rotavirus vaccine either on a neonatal schedule (0-5 days, 8-10 weeks, and 14-16 weeks of age) or an infant schedule (8-10 weeks, 14-16 weeks, and 18-20 weeks of age), or the equivalent schedules of placebo.

That efficacy was 77% in those who received the doses on the infant schedule.

Overall, severe rotavirus gastroenteritis was reported in 5.6% of the placebo group, compared with 2.1% of the combined vaccine group. The time from randomization to first episode of gastroenteritis was significantly longer among participants who received the vaccine, compared with those who received placebo.

“The use of a neonatal dose was investigated in the early phase of development of the rotavirus vaccine but was not pursued because of concerns regarding inadequate immune responses and safety,” wrote Dr. Bines and her associates

They noted that the results of this trial compared favorably with the efficacy of licensed vaccines in similar low-income countries that experienced a high burden of rotavirus disease.

The rates of severe adverse events were similar across all the trial groups. There were no episodes of intussusception seen within the 21-day risk period after immunization, either in the vaccine or placebo groups. However, there was one episode of intussusception in a child on the infant schedule group, which occurred 114 days after the third dose of the vaccine.

“Because intussusception is rare in newborns, the administration of a rotavirus vaccine at the time of birth may offer a safety advantage,” Dr. Bines and her associates said.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, PT Bio Farma, and the Victorian government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Authors declared fees, grants, and institutional support from the study sponsors, and three authors also declared a stake in the patent of the RV3-BB vaccine, which is licensed to PT Bio Farma.

SOURCE: Bines JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:719-30.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A new oral rotavirus vaccine given to newborns was associated with significant reductions in the incidence of severe rotavirus gastroenteritis.

Major finding: A new oral rotavirus vaccine given within the first 5 days of life showed 94% efficacy at 12 months of age.

Data source: A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial in 1,513 healthy newborns.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, PT Bio Farma, and the Victorian government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Authors declared fees, grants and institutional support from the study sponsors, and three authors also declared a stake in the patent of the RV3-BB vaccine, which is licensed to PT Bio Farma.

Source: Bines JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:719-30.

Prenatal betamethasone could save millions in care costs for women at risk of late preterm delivery

DALLAS – If betamethasone became a routine part of managing women at risk for late preterm birth, the U.S. health care system could save up to $200 million in direct costs every year.

A significant decrease in the cost of managing newborn respiratory morbidity would account for most of the savings, Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Not only was betamethasone treatment cost effective at its base price, but treatment retained economic dominance over no treatment even when its cost was inflated up to 500%.

She presented a cost analysis of the 2016 PARENT trial. PARENT randomized 2,831 women at risk of late preterm delivery to two injections of betamethasone or matching placebo 24 hours apart. Infants exposed to betamethasone were 20% less likely to experience the primary endpoint – a composite of the need for continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula, supplemental oxygen, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or mechanical ventilation. They were also significantly less likely to be stillborn or to die within 72 hours of delivery.

“We found that antenatal betamethasone significantly decreased perinatal morbidity and mortality,” she said. “However, the costs of this intervention were unknown. Therefore, we compared the cost-effectiveness of treatment with no treatment in these women.”

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman described the study as a cost-minimization analysis. “The analysis took a third-party payer approach with a time horizon to first hospital discharge to home.”

Maternal costs were based on Medicaid rates. These included the cost of the betamethasone, and any out- or inpatient visits necessary to administer the drug. The neonatal costs included all direct medical costs for the newborn, including neonatal ICU admissions and any respiratory therapy the infant required.

The analysis included all mother-infant pairs in PARENT who had at least one dose of their assigned study drug and full follow-up. This comprised 1,425 pairs who received betamethasone and 1,396 who received placebo. The total mean cost of maternal/newborn care in the betamethasone group was $4,774, compared with $5,473 in the placebo group – a significant difference.

The cost-effectiveness analysis, with effectiveness defined as the proportion not reaching the primary outcome, significantly favored betamethasone as well (88.4% vs. 85.5%).

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman also examined cost-effectiveness in a variety of pricing scenarios, from looking at betamethasone at its base cost with hospital and physician services priced at 50% of the current level, to betamethasone inflated by 500% and other costs by 200%.

“In almost every estimate, betamethasone remained the cost-effective management option,” she said. “ and was cost effective across most of our variable estimate.”

She had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:S14.

DALLAS – If betamethasone became a routine part of managing women at risk for late preterm birth, the U.S. health care system could save up to $200 million in direct costs every year.

A significant decrease in the cost of managing newborn respiratory morbidity would account for most of the savings, Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Not only was betamethasone treatment cost effective at its base price, but treatment retained economic dominance over no treatment even when its cost was inflated up to 500%.

She presented a cost analysis of the 2016 PARENT trial. PARENT randomized 2,831 women at risk of late preterm delivery to two injections of betamethasone or matching placebo 24 hours apart. Infants exposed to betamethasone were 20% less likely to experience the primary endpoint – a composite of the need for continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula, supplemental oxygen, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or mechanical ventilation. They were also significantly less likely to be stillborn or to die within 72 hours of delivery.

“We found that antenatal betamethasone significantly decreased perinatal morbidity and mortality,” she said. “However, the costs of this intervention were unknown. Therefore, we compared the cost-effectiveness of treatment with no treatment in these women.”

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman described the study as a cost-minimization analysis. “The analysis took a third-party payer approach with a time horizon to first hospital discharge to home.”

Maternal costs were based on Medicaid rates. These included the cost of the betamethasone, and any out- or inpatient visits necessary to administer the drug. The neonatal costs included all direct medical costs for the newborn, including neonatal ICU admissions and any respiratory therapy the infant required.

The analysis included all mother-infant pairs in PARENT who had at least one dose of their assigned study drug and full follow-up. This comprised 1,425 pairs who received betamethasone and 1,396 who received placebo. The total mean cost of maternal/newborn care in the betamethasone group was $4,774, compared with $5,473 in the placebo group – a significant difference.

The cost-effectiveness analysis, with effectiveness defined as the proportion not reaching the primary outcome, significantly favored betamethasone as well (88.4% vs. 85.5%).

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman also examined cost-effectiveness in a variety of pricing scenarios, from looking at betamethasone at its base cost with hospital and physician services priced at 50% of the current level, to betamethasone inflated by 500% and other costs by 200%.

“In almost every estimate, betamethasone remained the cost-effective management option,” she said. “ and was cost effective across most of our variable estimate.”

She had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:S14.

DALLAS – If betamethasone became a routine part of managing women at risk for late preterm birth, the U.S. health care system could save up to $200 million in direct costs every year.

A significant decrease in the cost of managing newborn respiratory morbidity would account for most of the savings, Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Not only was betamethasone treatment cost effective at its base price, but treatment retained economic dominance over no treatment even when its cost was inflated up to 500%.

She presented a cost analysis of the 2016 PARENT trial. PARENT randomized 2,831 women at risk of late preterm delivery to two injections of betamethasone or matching placebo 24 hours apart. Infants exposed to betamethasone were 20% less likely to experience the primary endpoint – a composite of the need for continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula, supplemental oxygen, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or mechanical ventilation. They were also significantly less likely to be stillborn or to die within 72 hours of delivery.

“We found that antenatal betamethasone significantly decreased perinatal morbidity and mortality,” she said. “However, the costs of this intervention were unknown. Therefore, we compared the cost-effectiveness of treatment with no treatment in these women.”

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman described the study as a cost-minimization analysis. “The analysis took a third-party payer approach with a time horizon to first hospital discharge to home.”

Maternal costs were based on Medicaid rates. These included the cost of the betamethasone, and any out- or inpatient visits necessary to administer the drug. The neonatal costs included all direct medical costs for the newborn, including neonatal ICU admissions and any respiratory therapy the infant required.

The analysis included all mother-infant pairs in PARENT who had at least one dose of their assigned study drug and full follow-up. This comprised 1,425 pairs who received betamethasone and 1,396 who received placebo. The total mean cost of maternal/newborn care in the betamethasone group was $4,774, compared with $5,473 in the placebo group – a significant difference.

The cost-effectiveness analysis, with effectiveness defined as the proportion not reaching the primary outcome, significantly favored betamethasone as well (88.4% vs. 85.5%).

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman also examined cost-effectiveness in a variety of pricing scenarios, from looking at betamethasone at its base cost with hospital and physician services priced at 50% of the current level, to betamethasone inflated by 500% and other costs by 200%.

“In almost every estimate, betamethasone remained the cost-effective management option,” she said. “ and was cost effective across most of our variable estimate.”

She had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:S14.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: If widely adopted, prenatal betamethasone could save up to $200 million per year by preventing neonatal respiratory morbidity.

Major finding: The total mean maternal/newborn care cost was $4,774 in the betamethasone group and $5,473 in the placebo group.

Study details: The cost analysis of the PARENT trial comprised 2,821 mother/infant pairs.

Disclosures: Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman had no financial disclosures.

Source: Gyamfi-Bannerman C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:S14.

Advocating for reality

Our first daughter was born during my last year in medical school, and our second was born as I was finishing my second year in residency. Seeing those two little darlings grow and develop was a critical supplement to my pediatric training. And, watching my wife initially struggle and then succeed with breastfeeding provided a very personal experience and education about lactation that my interactions in the hospital and outpatient clinics didn’t offer.

We considered ourselves lucky because my wife wasn’t facing the additional challenge of returning to an out-of-the-home job. However, our good fortune did not confer immunity against the anxiety, insecurity, discomfort, and sleep deprivation–induced frustrations of breastfeeding. Watching my wife navigate the choppy waters of lactation certainly influenced my approach to counseling new mothers over my subsequent 4 decades of practice. I think I was a more sympathetic and realistic adviser based on my first-hand observations.

In a different survey of American Academy of Pediatrics fellows, more of the 832 pediatricians responding reported having had a personal experience with breastfeeding in 2014 than of the 620 responding in 1995 (68% vs. 42%). However, it is interesting that fewer of the respondents in 2014 felt that any mother can succeed at breastfeeding (predicted value = 70% in 1995, PV = 56% in 2014; P less than .05), and fewer in 2014 believed that the advantages of breastfeeding outweighed the difficulties than among those surveyed in 1995 (PV = 70% in 1995, PV = 50% in 2014; P less than .05) (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct;140[4]. pii: e20171229). These results suggest that, as more pediatricians gained personal experience with breastfeeding, more may have realized that the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations for breastfeeding are unrealistic and may contribute to the negative experiences of some women, including pediatric trainees.

An implied assumption in the AAP News article is that a pediatrician who has had a negative breastfeeding experience is less likely to be a strong advocate for breastfeeding. I would argue that a pediatrician who has witnessed or personally experienced difficulties is more likely to be a sympathetic and realistic advocate of breastfeeding.

We must walk that fine line between actively advocating for lactation-friendly hospitals and work environments and supporting mothers who, due to circumstances beyond their control, can’t meet the expectations we have created for them.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Our first daughter was born during my last year in medical school, and our second was born as I was finishing my second year in residency. Seeing those two little darlings grow and develop was a critical supplement to my pediatric training. And, watching my wife initially struggle and then succeed with breastfeeding provided a very personal experience and education about lactation that my interactions in the hospital and outpatient clinics didn’t offer.

We considered ourselves lucky because my wife wasn’t facing the additional challenge of returning to an out-of-the-home job. However, our good fortune did not confer immunity against the anxiety, insecurity, discomfort, and sleep deprivation–induced frustrations of breastfeeding. Watching my wife navigate the choppy waters of lactation certainly influenced my approach to counseling new mothers over my subsequent 4 decades of practice. I think I was a more sympathetic and realistic adviser based on my first-hand observations.

In a different survey of American Academy of Pediatrics fellows, more of the 832 pediatricians responding reported having had a personal experience with breastfeeding in 2014 than of the 620 responding in 1995 (68% vs. 42%). However, it is interesting that fewer of the respondents in 2014 felt that any mother can succeed at breastfeeding (predicted value = 70% in 1995, PV = 56% in 2014; P less than .05), and fewer in 2014 believed that the advantages of breastfeeding outweighed the difficulties than among those surveyed in 1995 (PV = 70% in 1995, PV = 50% in 2014; P less than .05) (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct;140[4]. pii: e20171229). These results suggest that, as more pediatricians gained personal experience with breastfeeding, more may have realized that the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations for breastfeeding are unrealistic and may contribute to the negative experiences of some women, including pediatric trainees.

An implied assumption in the AAP News article is that a pediatrician who has had a negative breastfeeding experience is less likely to be a strong advocate for breastfeeding. I would argue that a pediatrician who has witnessed or personally experienced difficulties is more likely to be a sympathetic and realistic advocate of breastfeeding.

We must walk that fine line between actively advocating for lactation-friendly hospitals and work environments and supporting mothers who, due to circumstances beyond their control, can’t meet the expectations we have created for them.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Our first daughter was born during my last year in medical school, and our second was born as I was finishing my second year in residency. Seeing those two little darlings grow and develop was a critical supplement to my pediatric training. And, watching my wife initially struggle and then succeed with breastfeeding provided a very personal experience and education about lactation that my interactions in the hospital and outpatient clinics didn’t offer.

We considered ourselves lucky because my wife wasn’t facing the additional challenge of returning to an out-of-the-home job. However, our good fortune did not confer immunity against the anxiety, insecurity, discomfort, and sleep deprivation–induced frustrations of breastfeeding. Watching my wife navigate the choppy waters of lactation certainly influenced my approach to counseling new mothers over my subsequent 4 decades of practice. I think I was a more sympathetic and realistic adviser based on my first-hand observations.

In a different survey of American Academy of Pediatrics fellows, more of the 832 pediatricians responding reported having had a personal experience with breastfeeding in 2014 than of the 620 responding in 1995 (68% vs. 42%). However, it is interesting that fewer of the respondents in 2014 felt that any mother can succeed at breastfeeding (predicted value = 70% in 1995, PV = 56% in 2014; P less than .05), and fewer in 2014 believed that the advantages of breastfeeding outweighed the difficulties than among those surveyed in 1995 (PV = 70% in 1995, PV = 50% in 2014; P less than .05) (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct;140[4]. pii: e20171229). These results suggest that, as more pediatricians gained personal experience with breastfeeding, more may have realized that the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations for breastfeeding are unrealistic and may contribute to the negative experiences of some women, including pediatric trainees.

An implied assumption in the AAP News article is that a pediatrician who has had a negative breastfeeding experience is less likely to be a strong advocate for breastfeeding. I would argue that a pediatrician who has witnessed or personally experienced difficulties is more likely to be a sympathetic and realistic advocate of breastfeeding.

We must walk that fine line between actively advocating for lactation-friendly hospitals and work environments and supporting mothers who, due to circumstances beyond their control, can’t meet the expectations we have created for them.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

… What comes naturally

When we were invited to a family gathering to celebrate a 60th birthday, we expected to hear an abundance of news about grandchildren. They are natural, and seldom controversial, topics of discussion. If there is a child still waiting in utero and destined to be the first grandchild on one or both sides of the family, the impending adventure in parenthood will dominate the conversation.

To our great surprise, despite the presence of one very pregnant young woman, who in 6 weeks would be giving birth to the first grandchild in my nephew’s family, my wife and I can recall only one brief dialogue in which I was asked about how one might go about selecting a pediatrician.

I’m not sure why the blessed event to come was being ignored, but I found the oversight unusual and refreshing. It is possible that there had been so much hype about the pregnancy on her side of the family that the couple relished its absence from the birthday party’s topics for discussion.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I must add that, as a result of my frequent claims of ignorance when asked about medically related topics, I am often referred to by the extended family as “Dr. I-Don’t-Know.” It may be that my presence influenced the conversation, but regardless of the reason, I was impressed with the ease at which this couple was approaching the birth of their first child.

I am sure they harbor some anxieties, and I am sure they have listened to some horror stories from their peers about sleep and breastfeeding problems. They are bright people who acknowledge that they are going to encounter some bumps along the road of parenthood. However, they seem to be immune to the epidemic of anxiety that for decades has been sweeping over cohorts of North Americans entering their family-building years.

The young couple my wife and I encountered are just as clueless about what parenthood has in store as their anxiety-driven peers are. The difference is that they are enjoying their pregnancy in blissful ignorance buffered by their refreshing confidence that, however they do it, they will be doing it naturally.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

When we were invited to a family gathering to celebrate a 60th birthday, we expected to hear an abundance of news about grandchildren. They are natural, and seldom controversial, topics of discussion. If there is a child still waiting in utero and destined to be the first grandchild on one or both sides of the family, the impending adventure in parenthood will dominate the conversation.

To our great surprise, despite the presence of one very pregnant young woman, who in 6 weeks would be giving birth to the first grandchild in my nephew’s family, my wife and I can recall only one brief dialogue in which I was asked about how one might go about selecting a pediatrician.

I’m not sure why the blessed event to come was being ignored, but I found the oversight unusual and refreshing. It is possible that there had been so much hype about the pregnancy on her side of the family that the couple relished its absence from the birthday party’s topics for discussion.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I must add that, as a result of my frequent claims of ignorance when asked about medically related topics, I am often referred to by the extended family as “Dr. I-Don’t-Know.” It may be that my presence influenced the conversation, but regardless of the reason, I was impressed with the ease at which this couple was approaching the birth of their first child.

I am sure they harbor some anxieties, and I am sure they have listened to some horror stories from their peers about sleep and breastfeeding problems. They are bright people who acknowledge that they are going to encounter some bumps along the road of parenthood. However, they seem to be immune to the epidemic of anxiety that for decades has been sweeping over cohorts of North Americans entering their family-building years.

The young couple my wife and I encountered are just as clueless about what parenthood has in store as their anxiety-driven peers are. The difference is that they are enjoying their pregnancy in blissful ignorance buffered by their refreshing confidence that, however they do it, they will be doing it naturally.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

When we were invited to a family gathering to celebrate a 60th birthday, we expected to hear an abundance of news about grandchildren. They are natural, and seldom controversial, topics of discussion. If there is a child still waiting in utero and destined to be the first grandchild on one or both sides of the family, the impending adventure in parenthood will dominate the conversation.

To our great surprise, despite the presence of one very pregnant young woman, who in 6 weeks would be giving birth to the first grandchild in my nephew’s family, my wife and I can recall only one brief dialogue in which I was asked about how one might go about selecting a pediatrician.

I’m not sure why the blessed event to come was being ignored, but I found the oversight unusual and refreshing. It is possible that there had been so much hype about the pregnancy on her side of the family that the couple relished its absence from the birthday party’s topics for discussion.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I must add that, as a result of my frequent claims of ignorance when asked about medically related topics, I am often referred to by the extended family as “Dr. I-Don’t-Know.” It may be that my presence influenced the conversation, but regardless of the reason, I was impressed with the ease at which this couple was approaching the birth of their first child.

I am sure they harbor some anxieties, and I am sure they have listened to some horror stories from their peers about sleep and breastfeeding problems. They are bright people who acknowledge that they are going to encounter some bumps along the road of parenthood. However, they seem to be immune to the epidemic of anxiety that for decades has been sweeping over cohorts of North Americans entering their family-building years.

The young couple my wife and I encountered are just as clueless about what parenthood has in store as their anxiety-driven peers are. The difference is that they are enjoying their pregnancy in blissful ignorance buffered by their refreshing confidence that, however they do it, they will be doing it naturally.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Is elective induction at 39 weeks a good idea?

DALLAS – Elective inductions at 39 weeks’ gestation were safe for the newborn and conferred dual benefits upon first-time mothers, reducing the risk of cesarean delivery by 16% and pregnancy-related hypertensive disorder by 36%, compared with women managed expectantly.

Infants delivered by elective inductions were smaller than those born to expectantly managed women and experienced a 29% reduction in the need for respiratory support at birth, William A. Grobman, MD, reported at the meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. They were no more likely than infants in the comparator group to experience dangerous perinatal outcomes, including low Apgar scores, meconium inhalation, hypoxia, or birth trauma, said Dr. Grobman, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The new data, however, may set a new standard by which to make this decision, Dr. Grobman said.

“I will leave it up to the professional organizations to determine the final outcome of these data, but it’s important to understand that the Choosing Wisely recommendation was based on observational data that essentially used an incorrect clinical comparator” of spontaneous labor, he said. The large study that Dr. Grobman and his colleagues conducted used expectant management (EM) as the comparator, allowing women to continue up to 42 weeks’ gestation. Using this comparator, he said, “Our data are largely with almost every observational study” and with a recently published randomized controlled trial by Kate F. Walker, a clinical research fellow at the University of Nottingham (England).

That study determined that labor induction between 39 weeks and 39 weeks, 6 days, in women older than 35 years had no significant effect on the rate of cesarean section and no adverse short-term effects on maternal or neonatal outcomes.

Dr. Grobman conducted his randomized trial at 41 hospitals in the National Institutes of Health’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

It randomized 6,106 healthy, nulliparous women to either elective induction from 39 weeks to 39 weeks, 4 days, or to EM. These women were asked to forgo elective delivery before 40 weeks, 5 days, but to be delivered by 42 weeks, 2 days.