User login

Language difficulties persist until age 13 for very preterm infants

Children born very preterm continue to display language difficulties compared with term controls at 13 years of age, with no evidence of developmental “catch up.”

Given the functional implications associated with language deficits, early language-based interventions should be considered for children born VP, investigators wrote in Pediatrics.

“Difficulties in language functioning in this cohort of children born VP remained stable from 2 to 13 years of age. Although generalized language deficits were observed, the VP group had marked difficulties on expressive components of language,” wrote Thi-Nhu-Ngoc Nguyen, BSc, of Monash University, Melbourne, and her associates.

Read the full story here.

Children born very preterm continue to display language difficulties compared with term controls at 13 years of age, with no evidence of developmental “catch up.”

Given the functional implications associated with language deficits, early language-based interventions should be considered for children born VP, investigators wrote in Pediatrics.

“Difficulties in language functioning in this cohort of children born VP remained stable from 2 to 13 years of age. Although generalized language deficits were observed, the VP group had marked difficulties on expressive components of language,” wrote Thi-Nhu-Ngoc Nguyen, BSc, of Monash University, Melbourne, and her associates.

Read the full story here.

Children born very preterm continue to display language difficulties compared with term controls at 13 years of age, with no evidence of developmental “catch up.”

Given the functional implications associated with language deficits, early language-based interventions should be considered for children born VP, investigators wrote in Pediatrics.

“Difficulties in language functioning in this cohort of children born VP remained stable from 2 to 13 years of age. Although generalized language deficits were observed, the VP group had marked difficulties on expressive components of language,” wrote Thi-Nhu-Ngoc Nguyen, BSc, of Monash University, Melbourne, and her associates.

Read the full story here.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Evaluating fever in the first 90 days of life

Fever in the youngest of infants creates a challenge for the pediatric clinician. Fever is a common presentation for serious bacterial infection (SBI) although most fevers are due to viral infection. However, the clinical presentation does not necessarily differ, and the risk for a poor outcome in this age group is substantial.

In the early stages of my pediatric career, most febrile infants less than 90 days of age were evaluated for sepsis, admitted, and treated with antibiotics pending culture results. Group B streptococcal sepsis or Escherichia coli sepsis were common in the first month of life, and Haemophilus influenza type B or Streptococcus pneumoniae in the second and third months of life. The approach to fever in the first 90 days has changed following both the introduction of haemophilus and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, the experience with risk stratification criteria for identifying infants at low risk for SBI, and the recognition of urinary tract infection (UTI) as a common source of infection in this age group as well as development of criteria for diagnosis.

A further nuance was subsequently added with the introduction of rapid diagnostics for viral infection. Byington et al. found that the majority of febrile infants less than 90 days of age had viral infection with enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza or rotavirus.1 Using the Rochester risk stratification and the presence or absence of viral infection, she demonstrated that the risk of SBI was reduced in both high- and low-risk infants in the presence of viral infection; in low risk infants with viral infection, SBI was identified in 1.8%, compared with 3.1% in those without viral infection, and in high-risk infants. 5.5% has SBI when viral infection was found, compared to 16.7% in the absence of viral infection. She also proposed risk features to identify those infected with herpes simplex virus; age less than 42 days, vesicular rash, elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), CSF pleocytosis, and seizure or twitching.

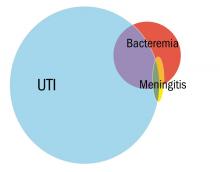

Greenhow et al. reported on the experience with “serious” bacterial infection in infants less than 90 days of age receiving care at Northern California Kaiser Permanente during the period 2005-2011.2 As pictured, the majority of children have UTI, and smaller numbers have bacteremia or meningitis. A small group of children with UTI have urosepsis as well; those with urosepsis can be differentiated from those with only UTI by age (less than 21 days), clinical exam (ill appearing), and elevated C reactive protein (greater than 20 mg/L) or elevated procalcitonin (greater than 0.5 ng/mL).3 Further evaluation of procalcitonin by other groups appears to validate its role in identifying children at low risk of SBI (procalcitonin less than 0.3 ng/mL).4

Currently, studies of febrile infants less than 90 days of age demonstrate that E. coli dominates in bacteremia, UTI, and meningitis, with Group B streptococcus as the next most frequent pathogen identified.2 Increasingly ampicillin resistance has been reported among E. coli isolates from both early- and late-onset disease as well as rare isolates that are resistant to third generation cephalosporins or gentamicin. Surveillance to identify changes in antimicrobial susceptibility will need to be ongoing to ensure that current approaches for initial therapy in high-risk infants aligns with current susceptibility patterns.

Dr. Pelton is chief of the section of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6):1662-6.

2. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014 Jun;33(6):595-9.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015 Jan;34(1):17-21.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):17-18.

5. “AAP Proposes Update to Evaluating, Managing Febrile Infants Guideline,” The Hospitalist, 2016.

Fever in the youngest of infants creates a challenge for the pediatric clinician. Fever is a common presentation for serious bacterial infection (SBI) although most fevers are due to viral infection. However, the clinical presentation does not necessarily differ, and the risk for a poor outcome in this age group is substantial.

In the early stages of my pediatric career, most febrile infants less than 90 days of age were evaluated for sepsis, admitted, and treated with antibiotics pending culture results. Group B streptococcal sepsis or Escherichia coli sepsis were common in the first month of life, and Haemophilus influenza type B or Streptococcus pneumoniae in the second and third months of life. The approach to fever in the first 90 days has changed following both the introduction of haemophilus and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, the experience with risk stratification criteria for identifying infants at low risk for SBI, and the recognition of urinary tract infection (UTI) as a common source of infection in this age group as well as development of criteria for diagnosis.

A further nuance was subsequently added with the introduction of rapid diagnostics for viral infection. Byington et al. found that the majority of febrile infants less than 90 days of age had viral infection with enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza or rotavirus.1 Using the Rochester risk stratification and the presence or absence of viral infection, she demonstrated that the risk of SBI was reduced in both high- and low-risk infants in the presence of viral infection; in low risk infants with viral infection, SBI was identified in 1.8%, compared with 3.1% in those without viral infection, and in high-risk infants. 5.5% has SBI when viral infection was found, compared to 16.7% in the absence of viral infection. She also proposed risk features to identify those infected with herpes simplex virus; age less than 42 days, vesicular rash, elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), CSF pleocytosis, and seizure or twitching.

Greenhow et al. reported on the experience with “serious” bacterial infection in infants less than 90 days of age receiving care at Northern California Kaiser Permanente during the period 2005-2011.2 As pictured, the majority of children have UTI, and smaller numbers have bacteremia or meningitis. A small group of children with UTI have urosepsis as well; those with urosepsis can be differentiated from those with only UTI by age (less than 21 days), clinical exam (ill appearing), and elevated C reactive protein (greater than 20 mg/L) or elevated procalcitonin (greater than 0.5 ng/mL).3 Further evaluation of procalcitonin by other groups appears to validate its role in identifying children at low risk of SBI (procalcitonin less than 0.3 ng/mL).4

Currently, studies of febrile infants less than 90 days of age demonstrate that E. coli dominates in bacteremia, UTI, and meningitis, with Group B streptococcus as the next most frequent pathogen identified.2 Increasingly ampicillin resistance has been reported among E. coli isolates from both early- and late-onset disease as well as rare isolates that are resistant to third generation cephalosporins or gentamicin. Surveillance to identify changes in antimicrobial susceptibility will need to be ongoing to ensure that current approaches for initial therapy in high-risk infants aligns with current susceptibility patterns.

Dr. Pelton is chief of the section of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6):1662-6.

2. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014 Jun;33(6):595-9.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015 Jan;34(1):17-21.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):17-18.

5. “AAP Proposes Update to Evaluating, Managing Febrile Infants Guideline,” The Hospitalist, 2016.

Fever in the youngest of infants creates a challenge for the pediatric clinician. Fever is a common presentation for serious bacterial infection (SBI) although most fevers are due to viral infection. However, the clinical presentation does not necessarily differ, and the risk for a poor outcome in this age group is substantial.

In the early stages of my pediatric career, most febrile infants less than 90 days of age were evaluated for sepsis, admitted, and treated with antibiotics pending culture results. Group B streptococcal sepsis or Escherichia coli sepsis were common in the first month of life, and Haemophilus influenza type B or Streptococcus pneumoniae in the second and third months of life. The approach to fever in the first 90 days has changed following both the introduction of haemophilus and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, the experience with risk stratification criteria for identifying infants at low risk for SBI, and the recognition of urinary tract infection (UTI) as a common source of infection in this age group as well as development of criteria for diagnosis.

A further nuance was subsequently added with the introduction of rapid diagnostics for viral infection. Byington et al. found that the majority of febrile infants less than 90 days of age had viral infection with enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza or rotavirus.1 Using the Rochester risk stratification and the presence or absence of viral infection, she demonstrated that the risk of SBI was reduced in both high- and low-risk infants in the presence of viral infection; in low risk infants with viral infection, SBI was identified in 1.8%, compared with 3.1% in those without viral infection, and in high-risk infants. 5.5% has SBI when viral infection was found, compared to 16.7% in the absence of viral infection. She also proposed risk features to identify those infected with herpes simplex virus; age less than 42 days, vesicular rash, elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), CSF pleocytosis, and seizure or twitching.

Greenhow et al. reported on the experience with “serious” bacterial infection in infants less than 90 days of age receiving care at Northern California Kaiser Permanente during the period 2005-2011.2 As pictured, the majority of children have UTI, and smaller numbers have bacteremia or meningitis. A small group of children with UTI have urosepsis as well; those with urosepsis can be differentiated from those with only UTI by age (less than 21 days), clinical exam (ill appearing), and elevated C reactive protein (greater than 20 mg/L) or elevated procalcitonin (greater than 0.5 ng/mL).3 Further evaluation of procalcitonin by other groups appears to validate its role in identifying children at low risk of SBI (procalcitonin less than 0.3 ng/mL).4

Currently, studies of febrile infants less than 90 days of age demonstrate that E. coli dominates in bacteremia, UTI, and meningitis, with Group B streptococcus as the next most frequent pathogen identified.2 Increasingly ampicillin resistance has been reported among E. coli isolates from both early- and late-onset disease as well as rare isolates that are resistant to third generation cephalosporins or gentamicin. Surveillance to identify changes in antimicrobial susceptibility will need to be ongoing to ensure that current approaches for initial therapy in high-risk infants aligns with current susceptibility patterns.

Dr. Pelton is chief of the section of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6):1662-6.

2. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014 Jun;33(6):595-9.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015 Jan;34(1):17-21.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):17-18.

5. “AAP Proposes Update to Evaluating, Managing Febrile Infants Guideline,” The Hospitalist, 2016.

PPIs, H2RAs in infants raise later allergy risk

Children prescribed histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), or antibiotics during the first 6 months of life may be at greater risk of developing allergic disease, research suggests.

A retrospective cohort study looked at the incidence of subsequent allergic disease in 792,130 children, 7.6% of whom were prescribed an H2RA, 1.7% were prescribed a PPI, and 16.6% were prescribed an antibiotic during the first 6 months of life.

Children who were prescribed a H2RA or a PPI had a greater than twofold higher incidence of food allergy (adjusted hazard ratios 2.18 and 2.59, respectively), reported Edward Mitre, MD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and his coauthors, reported in the April 2 online edition of JAMA Pediatrics.

In particular, the use of acid-suppressing medications was associated with a 2.4-fold increase in the risk of being diagnosed with cow’s milk allergy, while the risk of egg allergy was 74% higher in children prescribed an H2RA and 35% higher in children prescribed a PPI. In children prescribed an H2RA, the risk of peanut allergy was 21% higher, and in children prescribed a PPI, it was 27% higher.

There also was a dose-dependent interaction between the duration of medication and risk of food allergy. Children who were prescribed more than 60 days of PPIs had a 52% higher risk than did those who were prescribed 1-60 days, and a similar but slightly lower increased risk was seen in those prescribed more than 60 days of H2RAs (hazard ratio, 1.32).

Acid-suppressing medication use also was associated with an increased risk of nonfood allergies, in particular medication allergy (adjusted HR, 1.70 for H2RAs and 1.84 for PPIs), allergic rhinitis (aHR, 1.50 for H2RAs and 1.44 for PPIs), anaphylaxis (aHR, 1.51 for H2RAs and 1.45 for PPIs).

Infants prescribed acid-suppressing medication also showed higher rates of asthma, allergic conjunctivitis, and urticaria during childhood.

The use of antibiotics in the first 6 months of life was associated with a 14% higher incidence of food allergy but with a 24% higher risk of cow’s milk allergy and egg allergy. Children prescribed antibiotics also had a twofold greater risk of asthma, a 51% higher risk of anaphylaxis, 42% higher risk of allergic conjunctivitis, and a 34% higher risk of medication allergy.

“This study adds to the mounting evidence that agents that disrupt the normal intestinal microbiome during infancy may increase the development of allergic disease,” said Dr. Mitre and his coauthors. “Thus, this study provides further impetus that antibiotics and acid-suppressive medications should be used during infancy only in situations of clear clinical benefit.”

No funding source or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Mitre E et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315.

Children prescribed histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), or antibiotics during the first 6 months of life may be at greater risk of developing allergic disease, research suggests.

A retrospective cohort study looked at the incidence of subsequent allergic disease in 792,130 children, 7.6% of whom were prescribed an H2RA, 1.7% were prescribed a PPI, and 16.6% were prescribed an antibiotic during the first 6 months of life.

Children who were prescribed a H2RA or a PPI had a greater than twofold higher incidence of food allergy (adjusted hazard ratios 2.18 and 2.59, respectively), reported Edward Mitre, MD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and his coauthors, reported in the April 2 online edition of JAMA Pediatrics.

In particular, the use of acid-suppressing medications was associated with a 2.4-fold increase in the risk of being diagnosed with cow’s milk allergy, while the risk of egg allergy was 74% higher in children prescribed an H2RA and 35% higher in children prescribed a PPI. In children prescribed an H2RA, the risk of peanut allergy was 21% higher, and in children prescribed a PPI, it was 27% higher.

There also was a dose-dependent interaction between the duration of medication and risk of food allergy. Children who were prescribed more than 60 days of PPIs had a 52% higher risk than did those who were prescribed 1-60 days, and a similar but slightly lower increased risk was seen in those prescribed more than 60 days of H2RAs (hazard ratio, 1.32).

Acid-suppressing medication use also was associated with an increased risk of nonfood allergies, in particular medication allergy (adjusted HR, 1.70 for H2RAs and 1.84 for PPIs), allergic rhinitis (aHR, 1.50 for H2RAs and 1.44 for PPIs), anaphylaxis (aHR, 1.51 for H2RAs and 1.45 for PPIs).

Infants prescribed acid-suppressing medication also showed higher rates of asthma, allergic conjunctivitis, and urticaria during childhood.

The use of antibiotics in the first 6 months of life was associated with a 14% higher incidence of food allergy but with a 24% higher risk of cow’s milk allergy and egg allergy. Children prescribed antibiotics also had a twofold greater risk of asthma, a 51% higher risk of anaphylaxis, 42% higher risk of allergic conjunctivitis, and a 34% higher risk of medication allergy.

“This study adds to the mounting evidence that agents that disrupt the normal intestinal microbiome during infancy may increase the development of allergic disease,” said Dr. Mitre and his coauthors. “Thus, this study provides further impetus that antibiotics and acid-suppressive medications should be used during infancy only in situations of clear clinical benefit.”

No funding source or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Mitre E et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315.

Children prescribed histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), or antibiotics during the first 6 months of life may be at greater risk of developing allergic disease, research suggests.

A retrospective cohort study looked at the incidence of subsequent allergic disease in 792,130 children, 7.6% of whom were prescribed an H2RA, 1.7% were prescribed a PPI, and 16.6% were prescribed an antibiotic during the first 6 months of life.

Children who were prescribed a H2RA or a PPI had a greater than twofold higher incidence of food allergy (adjusted hazard ratios 2.18 and 2.59, respectively), reported Edward Mitre, MD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and his coauthors, reported in the April 2 online edition of JAMA Pediatrics.

In particular, the use of acid-suppressing medications was associated with a 2.4-fold increase in the risk of being diagnosed with cow’s milk allergy, while the risk of egg allergy was 74% higher in children prescribed an H2RA and 35% higher in children prescribed a PPI. In children prescribed an H2RA, the risk of peanut allergy was 21% higher, and in children prescribed a PPI, it was 27% higher.

There also was a dose-dependent interaction between the duration of medication and risk of food allergy. Children who were prescribed more than 60 days of PPIs had a 52% higher risk than did those who were prescribed 1-60 days, and a similar but slightly lower increased risk was seen in those prescribed more than 60 days of H2RAs (hazard ratio, 1.32).

Acid-suppressing medication use also was associated with an increased risk of nonfood allergies, in particular medication allergy (adjusted HR, 1.70 for H2RAs and 1.84 for PPIs), allergic rhinitis (aHR, 1.50 for H2RAs and 1.44 for PPIs), anaphylaxis (aHR, 1.51 for H2RAs and 1.45 for PPIs).

Infants prescribed acid-suppressing medication also showed higher rates of asthma, allergic conjunctivitis, and urticaria during childhood.

The use of antibiotics in the first 6 months of life was associated with a 14% higher incidence of food allergy but with a 24% higher risk of cow’s milk allergy and egg allergy. Children prescribed antibiotics also had a twofold greater risk of asthma, a 51% higher risk of anaphylaxis, 42% higher risk of allergic conjunctivitis, and a 34% higher risk of medication allergy.

“This study adds to the mounting evidence that agents that disrupt the normal intestinal microbiome during infancy may increase the development of allergic disease,” said Dr. Mitre and his coauthors. “Thus, this study provides further impetus that antibiotics and acid-suppressive medications should be used during infancy only in situations of clear clinical benefit.”

No funding source or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Mitre E et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Children prescribed acid-suppressing medications before 6 months had a greater than twofold higher incidence of food allergy.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study in 792,130 children between Oct. 1, 2001, and Sept. 30, 2013.

Disclosures: No funding source or conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Mitre E et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315.

QI initiative reduces antibiotic use in chorioamnionitis-exposed newborns

A hospital quality improvement initiative reduced antibiotic use by more than half when well-appearing newborns exposed to chorioamnionitis were initially monitored for symptoms instead of routinely given antibiotics, found a study in Pediatrics.

“The reduction in both antibiotic use and laboratory testing occurred without clinically relevant delays in care or poor outcomes,” wrote Neha S. Joshi, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and her associates.

At Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, about half of all antibiotic use for late-preterm or term infants went to newborns exposed to chorioamnionitis. The hospital developed a quality improvement initiative to safely reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in these patients and to decrease unnecessary lab testing given the weak clinical relevance of CBC counts and C-reactive protein labs for determining whether to give a well-appearing child antibiotics, the study authors explained.

Before the initiative began, standard practice included admitting all infants to the neonatal ICU who were at least 34 weeks’ gestation and exposed to chorioamnionitis. They were treated with ampicillin and gentamicin until early-onset sepsis was excluded. Lab evaluations included a CBC count, blood culture, and multiple C-reactive protein labs.

Under the new protocol, symptomatic newborns still had the same labs and received empirical antibiotics. Well-appearing, late-preterm or term infants exposed to chorioamnionitis first spent 2 hours of skin-to-skin contact with their mothers and then were monitored clinically in a level II nursery for at least 24 hours. Unless clinical symptoms developed in that time, the infants then were returned to their mothers until discharge without labs or antibiotics. Those who did develop potentially septic signs/symptoms, as determined by the treating physician, were evaluated and then received antibiotics if deemed appropriate.

During the first 15 months of the quality improvement initiative, 310 infants (5.7% of the 5,425 total births with at least 34 weeks’ gestation) were exposed to chorioamnionitis. Of these, 23 (7.4%) were symptomatic and began antibiotics; another 10 (3.2%) were admitted to the neonatal ICU for a congenital anomaly.

The researchers collected data on antibiotic use, lab tests, cultures, and clinical outcomes from the remaining 277 well-appearing newborns; 88% did not receive antibiotics during their hospital stay, and 83% underwent no laboratory testing. Only 17% of infants had lab testing for sepsis; none had culture result–positive, early-onset sepsis.

Only 12% of infants who initially appeared well developed signs/symptoms of sepsis, underwent laboratory testing, and received antibiotics. Nearly half of these (5% of all infants) received antibiotic treatment for at least 5 days despite negative cultures, while the other 7% received antibiotics for less than 48 hours, Dr. Joshi and her colleagues reported.

Infants with at least 34 weeks’ gestation receiving antibiotics at the hospital dropped from 12.3% before the initiative to 5.5% afterward, a 55% decrease (95% confidence interval, 40%-60%), the researchers said. Study limitations included a lack of postdischarge follow-up, the variability in physician decisions about which infants were symptomatic and which ones needed antibiotics, and an inability to generalize findings to institutions without 24/7 availability of neonatal hospitalists.

Past studies have found that all newborns with positive cultures showed symptoms at birth and needed resuscitation, continuous positive airway pressure, or intubation.

“An infant who is well-appearing at birth likely has an even lower risk of early-onset sepsis even in the setting of chorioamnionitis, and an empirical antibiotic treatment strategy for chorioamnionitis-exposed infants will result in a large number of uninfected infants being treated,” Dr. Joshi and her associates said. “Updated treatment approaches are needed to reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure and provide higher-value care in this population.”

The study did not use external funding. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Joshi NS et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172056.

A hospital quality improvement initiative reduced antibiotic use by more than half when well-appearing newborns exposed to chorioamnionitis were initially monitored for symptoms instead of routinely given antibiotics, found a study in Pediatrics.

“The reduction in both antibiotic use and laboratory testing occurred without clinically relevant delays in care or poor outcomes,” wrote Neha S. Joshi, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and her associates.

At Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, about half of all antibiotic use for late-preterm or term infants went to newborns exposed to chorioamnionitis. The hospital developed a quality improvement initiative to safely reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in these patients and to decrease unnecessary lab testing given the weak clinical relevance of CBC counts and C-reactive protein labs for determining whether to give a well-appearing child antibiotics, the study authors explained.

Before the initiative began, standard practice included admitting all infants to the neonatal ICU who were at least 34 weeks’ gestation and exposed to chorioamnionitis. They were treated with ampicillin and gentamicin until early-onset sepsis was excluded. Lab evaluations included a CBC count, blood culture, and multiple C-reactive protein labs.

Under the new protocol, symptomatic newborns still had the same labs and received empirical antibiotics. Well-appearing, late-preterm or term infants exposed to chorioamnionitis first spent 2 hours of skin-to-skin contact with their mothers and then were monitored clinically in a level II nursery for at least 24 hours. Unless clinical symptoms developed in that time, the infants then were returned to their mothers until discharge without labs or antibiotics. Those who did develop potentially septic signs/symptoms, as determined by the treating physician, were evaluated and then received antibiotics if deemed appropriate.

During the first 15 months of the quality improvement initiative, 310 infants (5.7% of the 5,425 total births with at least 34 weeks’ gestation) were exposed to chorioamnionitis. Of these, 23 (7.4%) were symptomatic and began antibiotics; another 10 (3.2%) were admitted to the neonatal ICU for a congenital anomaly.

The researchers collected data on antibiotic use, lab tests, cultures, and clinical outcomes from the remaining 277 well-appearing newborns; 88% did not receive antibiotics during their hospital stay, and 83% underwent no laboratory testing. Only 17% of infants had lab testing for sepsis; none had culture result–positive, early-onset sepsis.

Only 12% of infants who initially appeared well developed signs/symptoms of sepsis, underwent laboratory testing, and received antibiotics. Nearly half of these (5% of all infants) received antibiotic treatment for at least 5 days despite negative cultures, while the other 7% received antibiotics for less than 48 hours, Dr. Joshi and her colleagues reported.

Infants with at least 34 weeks’ gestation receiving antibiotics at the hospital dropped from 12.3% before the initiative to 5.5% afterward, a 55% decrease (95% confidence interval, 40%-60%), the researchers said. Study limitations included a lack of postdischarge follow-up, the variability in physician decisions about which infants were symptomatic and which ones needed antibiotics, and an inability to generalize findings to institutions without 24/7 availability of neonatal hospitalists.

Past studies have found that all newborns with positive cultures showed symptoms at birth and needed resuscitation, continuous positive airway pressure, or intubation.

“An infant who is well-appearing at birth likely has an even lower risk of early-onset sepsis even in the setting of chorioamnionitis, and an empirical antibiotic treatment strategy for chorioamnionitis-exposed infants will result in a large number of uninfected infants being treated,” Dr. Joshi and her associates said. “Updated treatment approaches are needed to reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure and provide higher-value care in this population.”

The study did not use external funding. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Joshi NS et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172056.

A hospital quality improvement initiative reduced antibiotic use by more than half when well-appearing newborns exposed to chorioamnionitis were initially monitored for symptoms instead of routinely given antibiotics, found a study in Pediatrics.

“The reduction in both antibiotic use and laboratory testing occurred without clinically relevant delays in care or poor outcomes,” wrote Neha S. Joshi, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and her associates.

At Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, about half of all antibiotic use for late-preterm or term infants went to newborns exposed to chorioamnionitis. The hospital developed a quality improvement initiative to safely reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in these patients and to decrease unnecessary lab testing given the weak clinical relevance of CBC counts and C-reactive protein labs for determining whether to give a well-appearing child antibiotics, the study authors explained.

Before the initiative began, standard practice included admitting all infants to the neonatal ICU who were at least 34 weeks’ gestation and exposed to chorioamnionitis. They were treated with ampicillin and gentamicin until early-onset sepsis was excluded. Lab evaluations included a CBC count, blood culture, and multiple C-reactive protein labs.

Under the new protocol, symptomatic newborns still had the same labs and received empirical antibiotics. Well-appearing, late-preterm or term infants exposed to chorioamnionitis first spent 2 hours of skin-to-skin contact with their mothers and then were monitored clinically in a level II nursery for at least 24 hours. Unless clinical symptoms developed in that time, the infants then were returned to their mothers until discharge without labs or antibiotics. Those who did develop potentially septic signs/symptoms, as determined by the treating physician, were evaluated and then received antibiotics if deemed appropriate.

During the first 15 months of the quality improvement initiative, 310 infants (5.7% of the 5,425 total births with at least 34 weeks’ gestation) were exposed to chorioamnionitis. Of these, 23 (7.4%) were symptomatic and began antibiotics; another 10 (3.2%) were admitted to the neonatal ICU for a congenital anomaly.

The researchers collected data on antibiotic use, lab tests, cultures, and clinical outcomes from the remaining 277 well-appearing newborns; 88% did not receive antibiotics during their hospital stay, and 83% underwent no laboratory testing. Only 17% of infants had lab testing for sepsis; none had culture result–positive, early-onset sepsis.

Only 12% of infants who initially appeared well developed signs/symptoms of sepsis, underwent laboratory testing, and received antibiotics. Nearly half of these (5% of all infants) received antibiotic treatment for at least 5 days despite negative cultures, while the other 7% received antibiotics for less than 48 hours, Dr. Joshi and her colleagues reported.

Infants with at least 34 weeks’ gestation receiving antibiotics at the hospital dropped from 12.3% before the initiative to 5.5% afterward, a 55% decrease (95% confidence interval, 40%-60%), the researchers said. Study limitations included a lack of postdischarge follow-up, the variability in physician decisions about which infants were symptomatic and which ones needed antibiotics, and an inability to generalize findings to institutions without 24/7 availability of neonatal hospitalists.

Past studies have found that all newborns with positive cultures showed symptoms at birth and needed resuscitation, continuous positive airway pressure, or intubation.

“An infant who is well-appearing at birth likely has an even lower risk of early-onset sepsis even in the setting of chorioamnionitis, and an empirical antibiotic treatment strategy for chorioamnionitis-exposed infants will result in a large number of uninfected infants being treated,” Dr. Joshi and her associates said. “Updated treatment approaches are needed to reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure and provide higher-value care in this population.”

The study did not use external funding. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Joshi NS et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172056.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: After a quality improvement initiative was implemented, 55% fewer late-preterm and term, chorioamnionitis-exposed infants received antibiotics without an increase in negative outcomes.

Data source: A study of 310 chorioamnionitis-exposed newborns who were late preterm or term at a California hospital.

Disclosures: The study did not use external funding. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Joshi NS et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172056.

Time to HIV rebound in infants off ART linked to birth health

BOSTON – For infants with HIV infection, baseline immune function and birth health appear to influence viral control after the discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), an analysis of data from the landmark CHER trial shows.

Among 183 children diagnosed with HIV between 6 and 12 weeks of age who were started on early, time-limited ART, longer time to viral rebound after treatment discontinuation was associated with higher baseline CD4 percentages, higher birth weight, and with achievement of viral suppression within 40 weeks of starting on ART, reported Man Chan, PhD, of the Medical Research Council clinical trials unit at University College London.

The CHER trial compared South African infants with HIV on either 40 or 96 weeks of immediate ART with those on deferred ART. The results showed that early time-limited ART was associated with better clinical and immunologic outcomes than was deferred ART and influenced a change in treatment guidelines (Lancet 2013 Nov 9;382[9904]:1555-63).

In the current analysis, investigators examined viral control after treatment interruption in early-treated children and looked for factors that could influence time to viral rebound after ART cessation.

They measured viral load from stored samples at 1.8 weeks after ART interruption and then every 12 weeks thereafter. They defined viral rebound as two consecutive samples with 400 or more copies/mL.

Of the 183 children in the sample, 177 had a rebound; the remaining six children were censored from the analysis, five because they had restarted ART, and one child who remained in viral suppression with an undetectable viral load and was asymptomatic for 8.5 years off ART.

The estimated cumulative probability of rebound was 70% at 2 months following ART interruption, 80% at 4 months, 94% at 6 months, and 99% at 8 months.

In multivariable analysis, factors significantly associated with longer time to viral rebound included higher baseline CD4 counts (P = .03), higher birth weight (P = .032), and viral suppression within 40 weeks of starting on ART (P = .028)

In contrast, there were no significant associations with other factors in the multivariate model, including sex, baseline viral load, baseline CD8 percentage, HIV stage, status of therapy to prevent mother-to-child transmission, age at ART initiation, length of therapy, or treatment center.

Sensitivity analyses of a few cases in which there was a 4-7 month gap between rebound and the last viral load below 400 copies/mL before rebound showed similar results, Dr. Chan noted.

The study was the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Dr. Chan reported having nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Violari A et al. CROI 2018, Abstract 137

BOSTON – For infants with HIV infection, baseline immune function and birth health appear to influence viral control after the discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), an analysis of data from the landmark CHER trial shows.

Among 183 children diagnosed with HIV between 6 and 12 weeks of age who were started on early, time-limited ART, longer time to viral rebound after treatment discontinuation was associated with higher baseline CD4 percentages, higher birth weight, and with achievement of viral suppression within 40 weeks of starting on ART, reported Man Chan, PhD, of the Medical Research Council clinical trials unit at University College London.

The CHER trial compared South African infants with HIV on either 40 or 96 weeks of immediate ART with those on deferred ART. The results showed that early time-limited ART was associated with better clinical and immunologic outcomes than was deferred ART and influenced a change in treatment guidelines (Lancet 2013 Nov 9;382[9904]:1555-63).

In the current analysis, investigators examined viral control after treatment interruption in early-treated children and looked for factors that could influence time to viral rebound after ART cessation.

They measured viral load from stored samples at 1.8 weeks after ART interruption and then every 12 weeks thereafter. They defined viral rebound as two consecutive samples with 400 or more copies/mL.

Of the 183 children in the sample, 177 had a rebound; the remaining six children were censored from the analysis, five because they had restarted ART, and one child who remained in viral suppression with an undetectable viral load and was asymptomatic for 8.5 years off ART.

The estimated cumulative probability of rebound was 70% at 2 months following ART interruption, 80% at 4 months, 94% at 6 months, and 99% at 8 months.

In multivariable analysis, factors significantly associated with longer time to viral rebound included higher baseline CD4 counts (P = .03), higher birth weight (P = .032), and viral suppression within 40 weeks of starting on ART (P = .028)

In contrast, there were no significant associations with other factors in the multivariate model, including sex, baseline viral load, baseline CD8 percentage, HIV stage, status of therapy to prevent mother-to-child transmission, age at ART initiation, length of therapy, or treatment center.

Sensitivity analyses of a few cases in which there was a 4-7 month gap between rebound and the last viral load below 400 copies/mL before rebound showed similar results, Dr. Chan noted.

The study was the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Dr. Chan reported having nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Violari A et al. CROI 2018, Abstract 137

BOSTON – For infants with HIV infection, baseline immune function and birth health appear to influence viral control after the discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), an analysis of data from the landmark CHER trial shows.

Among 183 children diagnosed with HIV between 6 and 12 weeks of age who were started on early, time-limited ART, longer time to viral rebound after treatment discontinuation was associated with higher baseline CD4 percentages, higher birth weight, and with achievement of viral suppression within 40 weeks of starting on ART, reported Man Chan, PhD, of the Medical Research Council clinical trials unit at University College London.

The CHER trial compared South African infants with HIV on either 40 or 96 weeks of immediate ART with those on deferred ART. The results showed that early time-limited ART was associated with better clinical and immunologic outcomes than was deferred ART and influenced a change in treatment guidelines (Lancet 2013 Nov 9;382[9904]:1555-63).

In the current analysis, investigators examined viral control after treatment interruption in early-treated children and looked for factors that could influence time to viral rebound after ART cessation.

They measured viral load from stored samples at 1.8 weeks after ART interruption and then every 12 weeks thereafter. They defined viral rebound as two consecutive samples with 400 or more copies/mL.

Of the 183 children in the sample, 177 had a rebound; the remaining six children were censored from the analysis, five because they had restarted ART, and one child who remained in viral suppression with an undetectable viral load and was asymptomatic for 8.5 years off ART.

The estimated cumulative probability of rebound was 70% at 2 months following ART interruption, 80% at 4 months, 94% at 6 months, and 99% at 8 months.

In multivariable analysis, factors significantly associated with longer time to viral rebound included higher baseline CD4 counts (P = .03), higher birth weight (P = .032), and viral suppression within 40 weeks of starting on ART (P = .028)

In contrast, there were no significant associations with other factors in the multivariate model, including sex, baseline viral load, baseline CD8 percentage, HIV stage, status of therapy to prevent mother-to-child transmission, age at ART initiation, length of therapy, or treatment center.

Sensitivity analyses of a few cases in which there was a 4-7 month gap between rebound and the last viral load below 400 copies/mL before rebound showed similar results, Dr. Chan noted.

The study was the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Dr. Chan reported having nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Violari A et al. CROI 2018, Abstract 137

FROM CROI 2018

Key clinical point: Early initiation of antiretroviral therapy in infants is associated with better outcomes.

Major finding: Longer time to viral rebound was associated with higher baseline CD4, higher birth weight, and viral suppression within 40 weeks of starting ART.

Study details: Analysis of outcomes in 183 infants with HIV infection in the CHER trial.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Dr. Chan reported having nothing to disclose.

Source: Violari A et al. CROI 2018, Abstract 137.

MDedge Daily News: Why most heart failure may be preventable

Why most heart failure may be preventable. Statins miss the mark in familial high cholesterol. Why mumps outbreaks are on the rise. And how using epileptic drugs in pregnancy affects school test scores.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Why most heart failure may be preventable. Statins miss the mark in familial high cholesterol. Why mumps outbreaks are on the rise. And how using epileptic drugs in pregnancy affects school test scores.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Why most heart failure may be preventable. Statins miss the mark in familial high cholesterol. Why mumps outbreaks are on the rise. And how using epileptic drugs in pregnancy affects school test scores.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Dr. T. Berry Brazelton was a pioneer of child-centered parenting

You may not realize it, but as you navigated through this morning’s hospital rounds and your busy office schedule, some of what you did and how you did it was the result of the pioneering work of Boston-based pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton, MD, who died March 13, 2018, at the age of 99.

You probably found the newborn you needed to examine in his mother’s hospital room. The 3-year-old in the croup tent was sharing his room with his father, who was sleeping on a cot at his crib side, and three out of the first four patients you saw in your office had been breastfed. These scenarios would have been unheard of 50 years ago. But Dr. Brazelton’s voice was the most widely heard, yet gentlest and persuasive in support of rooming-in and breastfeeding.

My fellow house officers and I had been accustomed to picking up infants to assess their tone. However, when Dr. Brazelton picked up a newborn, it was more like a conversation, an interview, and in a sense, it was a meeting of the minds.

It wasn’t that we had been rejecting the notion that a newborn could have a personality. It is just that we hadn’t been taught to look for it or to take it seriously. Dr. Brazelton taught us how to examine the person inside that little body and understand the importance of her temperament. By sharing what we learned from doing a Brazelton-style exam, we hoped to encourage the child’s parents to adopt more realistic expectations, and as a consequence, make parenting less mysterious and stressful.

When I first met Dr. Brazelton, he was in his mid-40s and just beginning on his trajectory toward national prominence. When we were assigned to take care of his hospitalized patients, it was obvious that his patient skills with sick children had taken a back seat to his interest in newborn temperament. He was more than willing to let us make the management decisions. In retrospect, that experience was a warning that I, like many other pediatricians, would face the similar challenge of maintaining my clinical skills in the face of a patient mix that was steadily acquiring a more behavioral and developmental flavor.

It is impossible to quantify the degree to which Dr. Brazelton’s ubiquity contributed to the popularity of a more child-centered parenting style. However, I think it would be unfair to blame him for the unfortunate phenomenon known as “helicopter parenting.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

You may not realize it, but as you navigated through this morning’s hospital rounds and your busy office schedule, some of what you did and how you did it was the result of the pioneering work of Boston-based pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton, MD, who died March 13, 2018, at the age of 99.

You probably found the newborn you needed to examine in his mother’s hospital room. The 3-year-old in the croup tent was sharing his room with his father, who was sleeping on a cot at his crib side, and three out of the first four patients you saw in your office had been breastfed. These scenarios would have been unheard of 50 years ago. But Dr. Brazelton’s voice was the most widely heard, yet gentlest and persuasive in support of rooming-in and breastfeeding.

My fellow house officers and I had been accustomed to picking up infants to assess their tone. However, when Dr. Brazelton picked up a newborn, it was more like a conversation, an interview, and in a sense, it was a meeting of the minds.

It wasn’t that we had been rejecting the notion that a newborn could have a personality. It is just that we hadn’t been taught to look for it or to take it seriously. Dr. Brazelton taught us how to examine the person inside that little body and understand the importance of her temperament. By sharing what we learned from doing a Brazelton-style exam, we hoped to encourage the child’s parents to adopt more realistic expectations, and as a consequence, make parenting less mysterious and stressful.

When I first met Dr. Brazelton, he was in his mid-40s and just beginning on his trajectory toward national prominence. When we were assigned to take care of his hospitalized patients, it was obvious that his patient skills with sick children had taken a back seat to his interest in newborn temperament. He was more than willing to let us make the management decisions. In retrospect, that experience was a warning that I, like many other pediatricians, would face the similar challenge of maintaining my clinical skills in the face of a patient mix that was steadily acquiring a more behavioral and developmental flavor.

It is impossible to quantify the degree to which Dr. Brazelton’s ubiquity contributed to the popularity of a more child-centered parenting style. However, I think it would be unfair to blame him for the unfortunate phenomenon known as “helicopter parenting.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

You may not realize it, but as you navigated through this morning’s hospital rounds and your busy office schedule, some of what you did and how you did it was the result of the pioneering work of Boston-based pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton, MD, who died March 13, 2018, at the age of 99.

You probably found the newborn you needed to examine in his mother’s hospital room. The 3-year-old in the croup tent was sharing his room with his father, who was sleeping on a cot at his crib side, and three out of the first four patients you saw in your office had been breastfed. These scenarios would have been unheard of 50 years ago. But Dr. Brazelton’s voice was the most widely heard, yet gentlest and persuasive in support of rooming-in and breastfeeding.

My fellow house officers and I had been accustomed to picking up infants to assess their tone. However, when Dr. Brazelton picked up a newborn, it was more like a conversation, an interview, and in a sense, it was a meeting of the minds.

It wasn’t that we had been rejecting the notion that a newborn could have a personality. It is just that we hadn’t been taught to look for it or to take it seriously. Dr. Brazelton taught us how to examine the person inside that little body and understand the importance of her temperament. By sharing what we learned from doing a Brazelton-style exam, we hoped to encourage the child’s parents to adopt more realistic expectations, and as a consequence, make parenting less mysterious and stressful.

When I first met Dr. Brazelton, he was in his mid-40s and just beginning on his trajectory toward national prominence. When we were assigned to take care of his hospitalized patients, it was obvious that his patient skills with sick children had taken a back seat to his interest in newborn temperament. He was more than willing to let us make the management decisions. In retrospect, that experience was a warning that I, like many other pediatricians, would face the similar challenge of maintaining my clinical skills in the face of a patient mix that was steadily acquiring a more behavioral and developmental flavor.

It is impossible to quantify the degree to which Dr. Brazelton’s ubiquity contributed to the popularity of a more child-centered parenting style. However, I think it would be unfair to blame him for the unfortunate phenomenon known as “helicopter parenting.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

High-dose oral ibuprofen most effective for PDA closure

compared with other pharmacological treatments, according to results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

However, using placebo or no treatment at all did not increase the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage in the study, published in JAMA.

PDA is a common cardiovascular issue among prematurely born infants. According to Dr. Mitra and his coauthors, it’s thought that a large proportion of PDAs spontaneously close in a few days and have minimal effect on clinical outcomes.

As a result, treatment is often targeted to PDAs deemed hemodynamically significant based on clinical and echocardiographic parameters, the authors wrote, although there is little guidance on what, if any, treatment to use in this situation.

“The dilemma is whether to use pharmacotherapy at all, and if a decision is made to treat the PDA medically, what should be the ideal choice of pharmacotherapy,” they wrote.

Dr. Mitra and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 68 randomized clinical trials including 4,802 infants with clinically or echocardiographically diagnosed, hemodynamically significant PDA.

They found that closure of hemodynamically significant PDA was significantly more likely with high-dose oral ibuprofen, compared with the two of the most widely used treatments, namely standard-dose intravenous ibuprofen (odds ratio, 3.59) and standard-dose intravenous indomethacin (odds ratio, 2.35).

Despite that finding, there was no significant difference in the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage for use of placebo or no treatment, compared with any of the treatment modalities, the investigators added.

“With increasing emphasis on conservative management of PDA, these results may encourage researchers to revisit placebo-controlled trials against newer pharmacotherapeutic options,” they said.

Study authors reported no relevant potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mitra S et al. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1221-38.

compared with other pharmacological treatments, according to results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

However, using placebo or no treatment at all did not increase the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage in the study, published in JAMA.

PDA is a common cardiovascular issue among prematurely born infants. According to Dr. Mitra and his coauthors, it’s thought that a large proportion of PDAs spontaneously close in a few days and have minimal effect on clinical outcomes.

As a result, treatment is often targeted to PDAs deemed hemodynamically significant based on clinical and echocardiographic parameters, the authors wrote, although there is little guidance on what, if any, treatment to use in this situation.

“The dilemma is whether to use pharmacotherapy at all, and if a decision is made to treat the PDA medically, what should be the ideal choice of pharmacotherapy,” they wrote.

Dr. Mitra and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 68 randomized clinical trials including 4,802 infants with clinically or echocardiographically diagnosed, hemodynamically significant PDA.

They found that closure of hemodynamically significant PDA was significantly more likely with high-dose oral ibuprofen, compared with the two of the most widely used treatments, namely standard-dose intravenous ibuprofen (odds ratio, 3.59) and standard-dose intravenous indomethacin (odds ratio, 2.35).

Despite that finding, there was no significant difference in the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage for use of placebo or no treatment, compared with any of the treatment modalities, the investigators added.

“With increasing emphasis on conservative management of PDA, these results may encourage researchers to revisit placebo-controlled trials against newer pharmacotherapeutic options,” they said.

Study authors reported no relevant potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mitra S et al. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1221-38.

compared with other pharmacological treatments, according to results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

However, using placebo or no treatment at all did not increase the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage in the study, published in JAMA.

PDA is a common cardiovascular issue among prematurely born infants. According to Dr. Mitra and his coauthors, it’s thought that a large proportion of PDAs spontaneously close in a few days and have minimal effect on clinical outcomes.

As a result, treatment is often targeted to PDAs deemed hemodynamically significant based on clinical and echocardiographic parameters, the authors wrote, although there is little guidance on what, if any, treatment to use in this situation.

“The dilemma is whether to use pharmacotherapy at all, and if a decision is made to treat the PDA medically, what should be the ideal choice of pharmacotherapy,” they wrote.

Dr. Mitra and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 68 randomized clinical trials including 4,802 infants with clinically or echocardiographically diagnosed, hemodynamically significant PDA.

They found that closure of hemodynamically significant PDA was significantly more likely with high-dose oral ibuprofen, compared with the two of the most widely used treatments, namely standard-dose intravenous ibuprofen (odds ratio, 3.59) and standard-dose intravenous indomethacin (odds ratio, 2.35).

Despite that finding, there was no significant difference in the odds of mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, or intraventricular hemorrhage for use of placebo or no treatment, compared with any of the treatment modalities, the investigators added.

“With increasing emphasis on conservative management of PDA, these results may encourage researchers to revisit placebo-controlled trials against newer pharmacotherapeutic options,” they said.

Study authors reported no relevant potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mitra S et al. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1221-38.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Compared with other pharmacological treatments, high-dose oral ibuprofen may be most likely to result in closure of hemodynamically significant PDA in preterm infants.

Major finding: Closure of hemodynamically significant PDA was significantly more likely with high-dose oral ibuprofen, compared with standard-dose intravenous ibuprofen (odds ratio, 3.59) and intravenous indomethacin (odds ratio, 2.35).

Study details: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 68 randomized clinical trials including 4,802 infants with clinically or echocardiographically diagnosed, hemodynamically significant PDA.

Disclosures: Study authors reported no relevant potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Mitra S et al. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1221-38.

RSV immunoprophylaxis in premature infants doesn’t prevent later asthma

reported Nienke M. Scheltema, MD, of Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands, and associates.

In a study of 395 otherwise healthy premature infants who were randomized to receive palivizumab for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunoprophylaxis or placebo and followed for 6 years, 14% of the 199 infants in the RSV prevention group had parent-reported asthma, compared with 24% of the 196 in the placebo group (absolute risk reduction, 9.9%). This was explained mostly by differences in infrequent wheeze, the researchers said. However, physician-diagnosed asthma in the past 12 months was not significantly different between the two groups at 6 years: 10.3% in the RSV prevention group and 9.9% in the placebo group.

SOURCE: Scheltema NM et al. Lancet. 2018 Feb 27. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30055-9.

reported Nienke M. Scheltema, MD, of Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands, and associates.

In a study of 395 otherwise healthy premature infants who were randomized to receive palivizumab for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunoprophylaxis or placebo and followed for 6 years, 14% of the 199 infants in the RSV prevention group had parent-reported asthma, compared with 24% of the 196 in the placebo group (absolute risk reduction, 9.9%). This was explained mostly by differences in infrequent wheeze, the researchers said. However, physician-diagnosed asthma in the past 12 months was not significantly different between the two groups at 6 years: 10.3% in the RSV prevention group and 9.9% in the placebo group.

SOURCE: Scheltema NM et al. Lancet. 2018 Feb 27. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30055-9.

reported Nienke M. Scheltema, MD, of Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands, and associates.

In a study of 395 otherwise healthy premature infants who were randomized to receive palivizumab for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunoprophylaxis or placebo and followed for 6 years, 14% of the 199 infants in the RSV prevention group had parent-reported asthma, compared with 24% of the 196 in the placebo group (absolute risk reduction, 9.9%). This was explained mostly by differences in infrequent wheeze, the researchers said. However, physician-diagnosed asthma in the past 12 months was not significantly different between the two groups at 6 years: 10.3% in the RSV prevention group and 9.9% in the placebo group.

SOURCE: Scheltema NM et al. Lancet. 2018 Feb 27. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30055-9.

FROM THE LANCET

Interventions urged to stop rising NAS, stem Medicaid costs

The incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and the corresponding costs to Medicaid are unlikely to decline unless interventions focus on stopping opioid use by low-income mothers, said Tyler N.A. Winkelman, MD, of Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his associates.

Dr. Winkelman and his associates conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis that used 9,115,457 birth discharge records from the 2004-2014 National Inpatient Sample (NIS), which were representative of 43.6 million weighted births. Overall, 3,991,336 infants were covered by Medicaid, which were representative of 19.1 million weighted births. There were 35,629 (0.89%) infants with a diagnosis of NAS, which were representative of 173,384 weighted births. Medicaid was the primary payer for 74% (95% confidence interval, 68.9%-77.9%) of NAS-related births in 2004 and 82% (95% CI, 80.5%-83.5%) of NAS-related births in 2014.

Infants with NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid were significantly more likely to be male, live in a rural county, and have comorbidities reflective of the syndrome than were infants without NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid, the researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

from 1.5 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 1.2-1.9) to 8 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 7.2-8.7), as the opioid epidemic worsened in the country.

Infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid had a greater chance of being transferred to another hospital for care (9% vs. 7%; P = .02) and stay in the hospital longer (17 days vs. 15 days; P less than .001), compared with infants with NAS who were covered by private insurance.

NAS is costly. In the 2011-2014 era, mean hospital costs for a NAS infant covered by Medicaid were more than fivefold higher than for an infant without NAS ($19,340/birth vs. $3,700/birth; P less than .001). After adjustment for inflation, mean hospital costs for infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid increased 26% between 2004-2006 and 2011-2014 ($15,350 vs. $19,340; P less than .001), the researchers reported. Annual hospital costs, which were adjusted for inflation to 2014 U.S. dollars, for all infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid rose from $65.4 million in 2004 to $462 million in 2014.

“With the disproportionate impact of NAS on the Medicaid population, we suggest that NAS incidence rates are unlikely to improve without interventions targeted at low-income mothers and infants,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates concluded.

Nonpharmacologic interventions are available to help NAS infants. “Systematic implementation of policies that support rooming-in, breastfeeding, swaddling, on-demand feeding schedules, and minimization of sleep disruption may reduce symptoms of NAS and reduce the duration of, or even eliminate the need for, pharmacologic treatment of NAS,” the researchers said. “Pharmacologic treatment with buprenorphine, for example, has been shown to reduce hospital length of stay by 35%.”

Another intervention is medication-assisted treatment during pregnancy, which studies have shown “improves outcomes and reduces costs associated with NAS, compared with attempted abstinence,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates said. It does not necessarily reduce NAS incidence, but “it may prevent prolonged hospital stays due to preterm birth, reduce NICU [neonatal intensive care unit] admissions, decrease the severity of NAS symptoms, and improve birth outcomes for some infants.”

The researchers also endorsed screening, referral, and treatment for substance abuse and mental health disorders among reproductive age women, including adolescents, because these are risk factors for opioid abuse.

One author was supported by an award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. None of the other authors had relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Winkelman TNA et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173520.

The incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and the corresponding costs to Medicaid are unlikely to decline unless interventions focus on stopping opioid use by low-income mothers, said Tyler N.A. Winkelman, MD, of Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his associates.

Dr. Winkelman and his associates conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis that used 9,115,457 birth discharge records from the 2004-2014 National Inpatient Sample (NIS), which were representative of 43.6 million weighted births. Overall, 3,991,336 infants were covered by Medicaid, which were representative of 19.1 million weighted births. There were 35,629 (0.89%) infants with a diagnosis of NAS, which were representative of 173,384 weighted births. Medicaid was the primary payer for 74% (95% confidence interval, 68.9%-77.9%) of NAS-related births in 2004 and 82% (95% CI, 80.5%-83.5%) of NAS-related births in 2014.

Infants with NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid were significantly more likely to be male, live in a rural county, and have comorbidities reflective of the syndrome than were infants without NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid, the researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

from 1.5 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 1.2-1.9) to 8 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 7.2-8.7), as the opioid epidemic worsened in the country.

Infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid had a greater chance of being transferred to another hospital for care (9% vs. 7%; P = .02) and stay in the hospital longer (17 days vs. 15 days; P less than .001), compared with infants with NAS who were covered by private insurance.

NAS is costly. In the 2011-2014 era, mean hospital costs for a NAS infant covered by Medicaid were more than fivefold higher than for an infant without NAS ($19,340/birth vs. $3,700/birth; P less than .001). After adjustment for inflation, mean hospital costs for infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid increased 26% between 2004-2006 and 2011-2014 ($15,350 vs. $19,340; P less than .001), the researchers reported. Annual hospital costs, which were adjusted for inflation to 2014 U.S. dollars, for all infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid rose from $65.4 million in 2004 to $462 million in 2014.

“With the disproportionate impact of NAS on the Medicaid population, we suggest that NAS incidence rates are unlikely to improve without interventions targeted at low-income mothers and infants,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates concluded.

Nonpharmacologic interventions are available to help NAS infants. “Systematic implementation of policies that support rooming-in, breastfeeding, swaddling, on-demand feeding schedules, and minimization of sleep disruption may reduce symptoms of NAS and reduce the duration of, or even eliminate the need for, pharmacologic treatment of NAS,” the researchers said. “Pharmacologic treatment with buprenorphine, for example, has been shown to reduce hospital length of stay by 35%.”

Another intervention is medication-assisted treatment during pregnancy, which studies have shown “improves outcomes and reduces costs associated with NAS, compared with attempted abstinence,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates said. It does not necessarily reduce NAS incidence, but “it may prevent prolonged hospital stays due to preterm birth, reduce NICU [neonatal intensive care unit] admissions, decrease the severity of NAS symptoms, and improve birth outcomes for some infants.”

The researchers also endorsed screening, referral, and treatment for substance abuse and mental health disorders among reproductive age women, including adolescents, because these are risk factors for opioid abuse.

One author was supported by an award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. None of the other authors had relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Winkelman TNA et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173520.

The incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and the corresponding costs to Medicaid are unlikely to decline unless interventions focus on stopping opioid use by low-income mothers, said Tyler N.A. Winkelman, MD, of Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his associates.

Dr. Winkelman and his associates conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis that used 9,115,457 birth discharge records from the 2004-2014 National Inpatient Sample (NIS), which were representative of 43.6 million weighted births. Overall, 3,991,336 infants were covered by Medicaid, which were representative of 19.1 million weighted births. There were 35,629 (0.89%) infants with a diagnosis of NAS, which were representative of 173,384 weighted births. Medicaid was the primary payer for 74% (95% confidence interval, 68.9%-77.9%) of NAS-related births in 2004 and 82% (95% CI, 80.5%-83.5%) of NAS-related births in 2014.

Infants with NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid were significantly more likely to be male, live in a rural county, and have comorbidities reflective of the syndrome than were infants without NAS who were enrolled in Medicaid, the researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

from 1.5 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 1.2-1.9) to 8 per 1,000 hospital births (95% CI, 7.2-8.7), as the opioid epidemic worsened in the country.

Infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid had a greater chance of being transferred to another hospital for care (9% vs. 7%; P = .02) and stay in the hospital longer (17 days vs. 15 days; P less than .001), compared with infants with NAS who were covered by private insurance.

NAS is costly. In the 2011-2014 era, mean hospital costs for a NAS infant covered by Medicaid were more than fivefold higher than for an infant without NAS ($19,340/birth vs. $3,700/birth; P less than .001). After adjustment for inflation, mean hospital costs for infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid increased 26% between 2004-2006 and 2011-2014 ($15,350 vs. $19,340; P less than .001), the researchers reported. Annual hospital costs, which were adjusted for inflation to 2014 U.S. dollars, for all infants with NAS who were covered by Medicaid rose from $65.4 million in 2004 to $462 million in 2014.

“With the disproportionate impact of NAS on the Medicaid population, we suggest that NAS incidence rates are unlikely to improve without interventions targeted at low-income mothers and infants,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates concluded.

Nonpharmacologic interventions are available to help NAS infants. “Systematic implementation of policies that support rooming-in, breastfeeding, swaddling, on-demand feeding schedules, and minimization of sleep disruption may reduce symptoms of NAS and reduce the duration of, or even eliminate the need for, pharmacologic treatment of NAS,” the researchers said. “Pharmacologic treatment with buprenorphine, for example, has been shown to reduce hospital length of stay by 35%.”

Another intervention is medication-assisted treatment during pregnancy, which studies have shown “improves outcomes and reduces costs associated with NAS, compared with attempted abstinence,” Dr. Winkelman and his associates said. It does not necessarily reduce NAS incidence, but “it may prevent prolonged hospital stays due to preterm birth, reduce NICU [neonatal intensive care unit] admissions, decrease the severity of NAS symptoms, and improve birth outcomes for some infants.”

The researchers also endorsed screening, referral, and treatment for substance abuse and mental health disorders among reproductive age women, including adolescents, because these are risk factors for opioid abuse.

One author was supported by an award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. None of the other authors had relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Winkelman TNA et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173520.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In 2011-2014, mean hospital costs for NAS infants covered by Medicaid were more than fivefold higher than for infants without NAS ($19,340/birth vs. $3,700/birth).

Study details: A serial cross-sectional analysis that usd data from the 2004-2014 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) of 9,115,457 birth discharge records.

Disclosures: Stephen W. Patrick, MD, was supported by an award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. None of the other authors had relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Winkelman TNA et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173520.