User login

Some women use prescription opioids during pregnancy

and almost a third of those women did not receive counseling from a provider on the effects of opioids on their unborn children, according to analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System 2019 survey show that 7% of the nearly 21,000 respondents reported using an opioid pain reliever during pregnancy, considerably lower than the fill rates of 14%-22% seen in studies of pharmacy dispensing, Jean Y. Ko, PhD, and associates at the CDC said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In the current analysis, opioid use during pregnancy varied by age – the rate was highest, 10%, in those aged 19 years and under and dropped as age increased to 6% among those aged 35 and older – and by race/ethnicity – 9% of black women reported use, compared with 7% of Hispanics, 6% of whites, and 7% of all others, the investigators reported.

Use of prescription opioids was significantly higher for two specific groups. Women who smoked cigarettes during the last 3 months of their pregnancy had a 16% rate of opioid use, and those with depression during pregnancy had a rate of 13%, they said.

Physicians caring for pregnant women should seek to identify and address substance use and misuse, and mental health conditions such as depression, history of trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and anxiety, the CDC researchers pointed out.

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists both recommend that caregivers and patients also need to “discuss and carefully weigh risks and benefits when considering initiation of opioid therapy for chronic pain during pregnancy,” Dr. Ko and associates wrote.

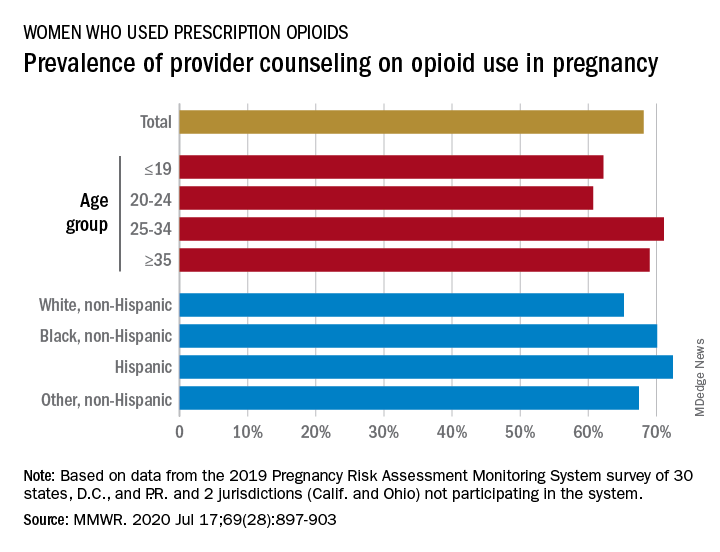

That sort of counseling, however, was not always offered: 32% of the women with self-reported prescription opioid use during their pregnancy said that they had not been counseled about the drugs’ effect on an infant. Some variation was seen by age or race/ethnicity, but the differences were not significant, the researchers reported.

“Opioid prescribing consistent with clinical practice guidelines can ensure that patients, particularly those who are pregnant, have access to safer, more effective chronic pain treatment and reduce the number of persons at risk for opioid misuse, opioid use disorder, and overdose,” the investigators concluded.

Survey data from 32 jurisdictions (30 states, along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) that participate in the monitoring system were included in the analysis, as were data from California and Ohio, which do not participate. All of the respondents had a live birth in the preceding 2-6 months, the researchers explained.

SOURCE: Ko JY et al. MMWR. 2020 Jul 17;69(28):897-903.

and almost a third of those women did not receive counseling from a provider on the effects of opioids on their unborn children, according to analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System 2019 survey show that 7% of the nearly 21,000 respondents reported using an opioid pain reliever during pregnancy, considerably lower than the fill rates of 14%-22% seen in studies of pharmacy dispensing, Jean Y. Ko, PhD, and associates at the CDC said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In the current analysis, opioid use during pregnancy varied by age – the rate was highest, 10%, in those aged 19 years and under and dropped as age increased to 6% among those aged 35 and older – and by race/ethnicity – 9% of black women reported use, compared with 7% of Hispanics, 6% of whites, and 7% of all others, the investigators reported.

Use of prescription opioids was significantly higher for two specific groups. Women who smoked cigarettes during the last 3 months of their pregnancy had a 16% rate of opioid use, and those with depression during pregnancy had a rate of 13%, they said.

Physicians caring for pregnant women should seek to identify and address substance use and misuse, and mental health conditions such as depression, history of trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and anxiety, the CDC researchers pointed out.

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists both recommend that caregivers and patients also need to “discuss and carefully weigh risks and benefits when considering initiation of opioid therapy for chronic pain during pregnancy,” Dr. Ko and associates wrote.

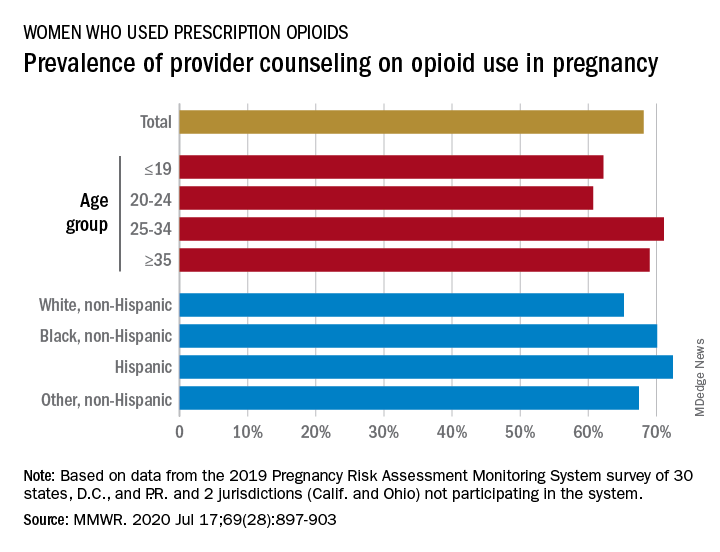

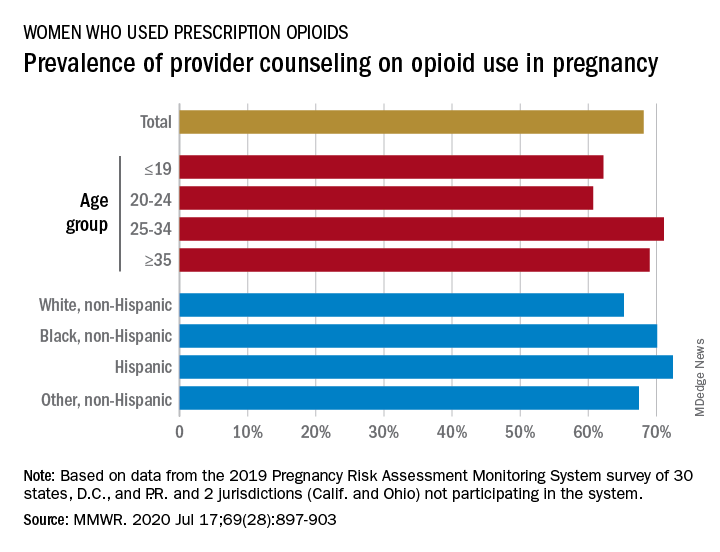

That sort of counseling, however, was not always offered: 32% of the women with self-reported prescription opioid use during their pregnancy said that they had not been counseled about the drugs’ effect on an infant. Some variation was seen by age or race/ethnicity, but the differences were not significant, the researchers reported.

“Opioid prescribing consistent with clinical practice guidelines can ensure that patients, particularly those who are pregnant, have access to safer, more effective chronic pain treatment and reduce the number of persons at risk for opioid misuse, opioid use disorder, and overdose,” the investigators concluded.

Survey data from 32 jurisdictions (30 states, along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) that participate in the monitoring system were included in the analysis, as were data from California and Ohio, which do not participate. All of the respondents had a live birth in the preceding 2-6 months, the researchers explained.

SOURCE: Ko JY et al. MMWR. 2020 Jul 17;69(28):897-903.

and almost a third of those women did not receive counseling from a provider on the effects of opioids on their unborn children, according to analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System 2019 survey show that 7% of the nearly 21,000 respondents reported using an opioid pain reliever during pregnancy, considerably lower than the fill rates of 14%-22% seen in studies of pharmacy dispensing, Jean Y. Ko, PhD, and associates at the CDC said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In the current analysis, opioid use during pregnancy varied by age – the rate was highest, 10%, in those aged 19 years and under and dropped as age increased to 6% among those aged 35 and older – and by race/ethnicity – 9% of black women reported use, compared with 7% of Hispanics, 6% of whites, and 7% of all others, the investigators reported.

Use of prescription opioids was significantly higher for two specific groups. Women who smoked cigarettes during the last 3 months of their pregnancy had a 16% rate of opioid use, and those with depression during pregnancy had a rate of 13%, they said.

Physicians caring for pregnant women should seek to identify and address substance use and misuse, and mental health conditions such as depression, history of trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and anxiety, the CDC researchers pointed out.

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists both recommend that caregivers and patients also need to “discuss and carefully weigh risks and benefits when considering initiation of opioid therapy for chronic pain during pregnancy,” Dr. Ko and associates wrote.

That sort of counseling, however, was not always offered: 32% of the women with self-reported prescription opioid use during their pregnancy said that they had not been counseled about the drugs’ effect on an infant. Some variation was seen by age or race/ethnicity, but the differences were not significant, the researchers reported.

“Opioid prescribing consistent with clinical practice guidelines can ensure that patients, particularly those who are pregnant, have access to safer, more effective chronic pain treatment and reduce the number of persons at risk for opioid misuse, opioid use disorder, and overdose,” the investigators concluded.

Survey data from 32 jurisdictions (30 states, along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) that participate in the monitoring system were included in the analysis, as were data from California and Ohio, which do not participate. All of the respondents had a live birth in the preceding 2-6 months, the researchers explained.

SOURCE: Ko JY et al. MMWR. 2020 Jul 17;69(28):897-903.

FROM MMWR

Travel times to opioid addiction programs drive a lack of access to treatment

If US pharmacies were permitted to dispense methadone for opioid use disorder (OUD) it would improve national access to treatment and save costs, new research suggests.

Under current federal regulations, only opioid treatment programs (OTPs) are permitted to dispense methadone maintenance treatment. This stands in sharp contrast to how methadone is dispensed in Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, where patients can obtain daily doses of methadone maintenance from community pharmacies.

“It’s challenging for patients in many parts of the US to access methadone treatment,” Robert Kleinman, MD, of Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, said in a JAMA Psychiatry podcast.

“It’s important for policymakers to consider strategies that enhance access to methadone maintenance treatment, in that it’s associated with large reductions in mortality from opioid use disorder. One possibility is to use pharmacies as dispensing sites,” said Kleinman.

The study was published online July 15 in JAMA Psychiatry.

An Hour vs 10 Minutes

Kleinman examined how pharmacy-based dispensing would affect drive times to the nearest OTP for the general US population. The analysis included all 1682 OTP locations, 69,475 unique pharmacy locations, and 72,443 census tracts.

The average drive time to OTPs in the US is 20.4 minutes vs a drive time of 4.5 minutes to pharmacies.

Driving times to OTPs are particularly long in nonmetropolitan counties while pharmacies remain “relatively easily accessible” in nonmetropolitan counties, he said.

In “micropolitan” counties, for example, the drive time to OTPs was 48.4 minutes vs 7 minutes to pharmacies. In the most rural counties, the drive time to OTPs is 60.9 minutes vs 9.1 minutes to pharmacies.

“This suggests that pharmacy-based dispensing has the potential to reduce urban or rural inequities, and access to methadone treatment,” Kleinman said.

In a mileage cost analysis, Kleinman determined that the average cost of one-way trip to an OTP in the US is $3.12 compared with 45 cents to a pharmacy. In the most rural counties, the average cost one-way is $11.10 vs $1.27 to a pharmacy.

Kleinman says decreasing drive times, distance, and costs for patients seeking methadone treatment by allowing pharmacies to dispense the medication may help achieve several public health goals.

“Patients dissuaded from obtaining treatment because of extended travel, particularly patients with disabilities, unreliable access to transportation, or from rural regions, would have reduced barriers to care. Quality of life may be increased for the more than 380,000 individuals currently receiving methadone treatment if less time is spent commuting,” he writes.

Time for Change

The authors of an accompanying editorial, say the “regulatory burden” on methadone provision in the US “effectively prohibits the integration of methadone prescribing into primary care, even in rural communities where there may exist no specialty substance use treatment options.”

However, federal and state agencies are starting to take action to expand geographic access to methadone treatment, note Paul Joudrey, MD, MPH, and coauthors from Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

, and Ohio and Kentucky have passed laws to allow greater use of federally qualified health centers and other facilities for methadone dispensing.

“While these policies are welcomed, the results here by Kleinman and others suggest they fall short of needed expansion if patients’ rights to evidence-based care for OUD are to be ensured. Importantly, even with broad adoption of mobile or pharmacy-based dispensing, patients would still face a long drive time to a central OTP before starting methadone,” Joudrey and colleagues write.

In their view, the only way to address this barrier is to modify federal law, and this “should be urgently pursued in the context of the ongoing overdose epidemic. It is time for policies that truly support methadone treatment for OUD as opposed to focusing on diversion.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If US pharmacies were permitted to dispense methadone for opioid use disorder (OUD) it would improve national access to treatment and save costs, new research suggests.

Under current federal regulations, only opioid treatment programs (OTPs) are permitted to dispense methadone maintenance treatment. This stands in sharp contrast to how methadone is dispensed in Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, where patients can obtain daily doses of methadone maintenance from community pharmacies.

“It’s challenging for patients in many parts of the US to access methadone treatment,” Robert Kleinman, MD, of Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, said in a JAMA Psychiatry podcast.

“It’s important for policymakers to consider strategies that enhance access to methadone maintenance treatment, in that it’s associated with large reductions in mortality from opioid use disorder. One possibility is to use pharmacies as dispensing sites,” said Kleinman.

The study was published online July 15 in JAMA Psychiatry.

An Hour vs 10 Minutes

Kleinman examined how pharmacy-based dispensing would affect drive times to the nearest OTP for the general US population. The analysis included all 1682 OTP locations, 69,475 unique pharmacy locations, and 72,443 census tracts.

The average drive time to OTPs in the US is 20.4 minutes vs a drive time of 4.5 minutes to pharmacies.

Driving times to OTPs are particularly long in nonmetropolitan counties while pharmacies remain “relatively easily accessible” in nonmetropolitan counties, he said.

In “micropolitan” counties, for example, the drive time to OTPs was 48.4 minutes vs 7 minutes to pharmacies. In the most rural counties, the drive time to OTPs is 60.9 minutes vs 9.1 minutes to pharmacies.

“This suggests that pharmacy-based dispensing has the potential to reduce urban or rural inequities, and access to methadone treatment,” Kleinman said.

In a mileage cost analysis, Kleinman determined that the average cost of one-way trip to an OTP in the US is $3.12 compared with 45 cents to a pharmacy. In the most rural counties, the average cost one-way is $11.10 vs $1.27 to a pharmacy.

Kleinman says decreasing drive times, distance, and costs for patients seeking methadone treatment by allowing pharmacies to dispense the medication may help achieve several public health goals.

“Patients dissuaded from obtaining treatment because of extended travel, particularly patients with disabilities, unreliable access to transportation, or from rural regions, would have reduced barriers to care. Quality of life may be increased for the more than 380,000 individuals currently receiving methadone treatment if less time is spent commuting,” he writes.

Time for Change

The authors of an accompanying editorial, say the “regulatory burden” on methadone provision in the US “effectively prohibits the integration of methadone prescribing into primary care, even in rural communities where there may exist no specialty substance use treatment options.”

However, federal and state agencies are starting to take action to expand geographic access to methadone treatment, note Paul Joudrey, MD, MPH, and coauthors from Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

, and Ohio and Kentucky have passed laws to allow greater use of federally qualified health centers and other facilities for methadone dispensing.

“While these policies are welcomed, the results here by Kleinman and others suggest they fall short of needed expansion if patients’ rights to evidence-based care for OUD are to be ensured. Importantly, even with broad adoption of mobile or pharmacy-based dispensing, patients would still face a long drive time to a central OTP before starting methadone,” Joudrey and colleagues write.

In their view, the only way to address this barrier is to modify federal law, and this “should be urgently pursued in the context of the ongoing overdose epidemic. It is time for policies that truly support methadone treatment for OUD as opposed to focusing on diversion.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If US pharmacies were permitted to dispense methadone for opioid use disorder (OUD) it would improve national access to treatment and save costs, new research suggests.

Under current federal regulations, only opioid treatment programs (OTPs) are permitted to dispense methadone maintenance treatment. This stands in sharp contrast to how methadone is dispensed in Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, where patients can obtain daily doses of methadone maintenance from community pharmacies.

“It’s challenging for patients in many parts of the US to access methadone treatment,” Robert Kleinman, MD, of Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, said in a JAMA Psychiatry podcast.

“It’s important for policymakers to consider strategies that enhance access to methadone maintenance treatment, in that it’s associated with large reductions in mortality from opioid use disorder. One possibility is to use pharmacies as dispensing sites,” said Kleinman.

The study was published online July 15 in JAMA Psychiatry.

An Hour vs 10 Minutes

Kleinman examined how pharmacy-based dispensing would affect drive times to the nearest OTP for the general US population. The analysis included all 1682 OTP locations, 69,475 unique pharmacy locations, and 72,443 census tracts.

The average drive time to OTPs in the US is 20.4 minutes vs a drive time of 4.5 minutes to pharmacies.

Driving times to OTPs are particularly long in nonmetropolitan counties while pharmacies remain “relatively easily accessible” in nonmetropolitan counties, he said.

In “micropolitan” counties, for example, the drive time to OTPs was 48.4 minutes vs 7 minutes to pharmacies. In the most rural counties, the drive time to OTPs is 60.9 minutes vs 9.1 minutes to pharmacies.

“This suggests that pharmacy-based dispensing has the potential to reduce urban or rural inequities, and access to methadone treatment,” Kleinman said.

In a mileage cost analysis, Kleinman determined that the average cost of one-way trip to an OTP in the US is $3.12 compared with 45 cents to a pharmacy. In the most rural counties, the average cost one-way is $11.10 vs $1.27 to a pharmacy.

Kleinman says decreasing drive times, distance, and costs for patients seeking methadone treatment by allowing pharmacies to dispense the medication may help achieve several public health goals.

“Patients dissuaded from obtaining treatment because of extended travel, particularly patients with disabilities, unreliable access to transportation, or from rural regions, would have reduced barriers to care. Quality of life may be increased for the more than 380,000 individuals currently receiving methadone treatment if less time is spent commuting,” he writes.

Time for Change

The authors of an accompanying editorial, say the “regulatory burden” on methadone provision in the US “effectively prohibits the integration of methadone prescribing into primary care, even in rural communities where there may exist no specialty substance use treatment options.”

However, federal and state agencies are starting to take action to expand geographic access to methadone treatment, note Paul Joudrey, MD, MPH, and coauthors from Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

, and Ohio and Kentucky have passed laws to allow greater use of federally qualified health centers and other facilities for methadone dispensing.

“While these policies are welcomed, the results here by Kleinman and others suggest they fall short of needed expansion if patients’ rights to evidence-based care for OUD are to be ensured. Importantly, even with broad adoption of mobile or pharmacy-based dispensing, patients would still face a long drive time to a central OTP before starting methadone,” Joudrey and colleagues write.

In their view, the only way to address this barrier is to modify federal law, and this “should be urgently pursued in the context of the ongoing overdose epidemic. It is time for policies that truly support methadone treatment for OUD as opposed to focusing on diversion.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medication-assisted treatment in corrections: A life-saving intervention

Opioid overdose deaths in the United States have more than tripled in recent years, from 6.1 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 1999 to 20.7 per 100,000 individuals in 2018.1 Although the availability of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) has expanded over the past decade, this lifesaving treatment remains largely inaccessible to some of the most vulnerable members of our communities: opioid users facing reentry after incarceration.

Just as abstinence in the community brings a loss of tolerance to opioids, individuals who are incarcerated lose tolerance as well. Clinicians who treat patients with opioid use disorders (OUD) are accustomed to warning patients about the risk of returning to prior levels of use too quickly. Harm reduction strategies include using slowly, using with friends, and having naloxone on hand to prevent unintended overdose.

The risks of opioid use are magnified for those facing reentry; incarceration contributes to a loss of employment, social supports, and connection to care. Those changes can create an exceptionally stressful reentry period – one that places individuals at an acutely high risk of relapse and overdose. Within the first 2 years of release, an individual with a history of incarceration has a risk of death 3.5 times higher than that of someone in the general population. Within the first 2 weeks, those recently incarcerated are 129 times more likely to overdose on opioids and 12.7 times more likely to die than members of the general population.2

Treatment with MAT dramatically reduces deaths during this crucial period. In England, large national studies have shown a similar 75% decrease in all-cause mortality within the first 4 weeks of release among individuals with OUD.4 In California, the counties with the highest overdose death rates are consistently those with fewer opioid treatment programs, which suggests that access to treatment is necessary to prolong the lives of those suffering from OUD.5 In-custody overdose deaths are quite rare, and access to MAT during incarceration has decreased in-custody deaths by 74%.6

Decreased opioid overdose deaths is not the only outcome of MAT. Pharmacotherapy for OUD also has been shown to increase treatment retention,7 reduce reincarceration,8 prevent communicable infections,9 and decrease use of other illicit substances.10 The provision of MAT also has been shown to be cost effective.11

Despite those benefits, as of 2017, only 30 out of 5,100 jails and prisons in the United States provided treatment with methadone or buprenorphine.12 When individuals on maintenance therapy are incarcerated, most correctional facilities force them to taper and discontinue those medications. This practice can cause distressing withdrawal symptoms and actively increase the risk of death for these individuals.

Concerns related to the provision of MAT, and specifically buprenorphine, in the correctional health setting often are related to diversion. Although safe administration of opioid full and partial agonists is a priority, recent literature has suggested that buprenorphine is not a medication frequently used for euphoric properties. In fact, the literature suggests that individuals using illicit buprenorphine primarily do so to treat withdrawal symptoms and that illicit use diminishes with access to formal treatment.13,14

Another concern is that pharmacotherapy for OUD should not be used without adjunctive psychotherapies and social supports. While dual pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is ideal, the American Society for Addiction Medicine 2020 National Practice Guidelines for the treatment of OUD state: “a patient’s decision to decline psychosocial treatment or the absence of available psychosocial treatment should not preclude or delay pharmacotherapy, with appropriate medication management.”15 Just as some patients wish to engage in mutual help or psychotherapeutic modalities only, some patients wish to engage only in psychopharmacologic interventions. Declaring one modality of treatment better, or worse, or more worthwhile is not borne out by the literature and often places clinicians’ preferences over the preferences of patients.

Individuals who suffer from substance use disorders are at high risk of incarceration, relapse, and overdose death. These patients also suffer from stigmatization from peers and health care workers alike, making the process of engaging in care incredibly burdensome. Because of the disease of addiction, many of our patients cannot envision a healthy future: a future with the potential for intimate relationships, meaningful community engagement, and a rich inner life. The provision of MAT is lifesaving and improves the chances of a successful reentry – an intuitive first step in a long, but worthwhile, journey.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al; National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, 2020 Jan, No. 356.

2. Binswanger IA et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157-65.

3. Green TC et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):405-7.

4. Marsden J et al. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1408-18.

5. Joshi V and Urada D. State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis: California Strategic Plan. 2017 Aug 30.

6. Larney S et al. BMJ Open. 2014. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004666.

7. Rich JD et al. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350-9.

8. Deck D et al. J Addict Dis. 2009. 28(2):89-102.

9. MacArthur GJ et al. BMJ. 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5945.

10. Tsui J et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019. 109:80-5.

11. Gisev N et al. Addiction. 2015 Dec;110(12):1975-84.

12. National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. “Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings.” HHS Publication No. PEP19-MATUSECJS. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019.

13. Bazazi AR et al. J Addict Med. 2011;5(3):175-80.

14. Schuman-Olivier Z. et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010 Jul;39(1):41-50.

15. Crotty K et al. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2)99-112.

Dr. Barnes is chief resident at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services in California. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Lenane is resident* at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The opinions shared in this article represent the viewpoints of the authors and are not necessarily representative of the viewpoints or policies of their academic program or employer.

*This article was updated 7/9/2020.

Opioid overdose deaths in the United States have more than tripled in recent years, from 6.1 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 1999 to 20.7 per 100,000 individuals in 2018.1 Although the availability of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) has expanded over the past decade, this lifesaving treatment remains largely inaccessible to some of the most vulnerable members of our communities: opioid users facing reentry after incarceration.

Just as abstinence in the community brings a loss of tolerance to opioids, individuals who are incarcerated lose tolerance as well. Clinicians who treat patients with opioid use disorders (OUD) are accustomed to warning patients about the risk of returning to prior levels of use too quickly. Harm reduction strategies include using slowly, using with friends, and having naloxone on hand to prevent unintended overdose.

The risks of opioid use are magnified for those facing reentry; incarceration contributes to a loss of employment, social supports, and connection to care. Those changes can create an exceptionally stressful reentry period – one that places individuals at an acutely high risk of relapse and overdose. Within the first 2 years of release, an individual with a history of incarceration has a risk of death 3.5 times higher than that of someone in the general population. Within the first 2 weeks, those recently incarcerated are 129 times more likely to overdose on opioids and 12.7 times more likely to die than members of the general population.2

Treatment with MAT dramatically reduces deaths during this crucial period. In England, large national studies have shown a similar 75% decrease in all-cause mortality within the first 4 weeks of release among individuals with OUD.4 In California, the counties with the highest overdose death rates are consistently those with fewer opioid treatment programs, which suggests that access to treatment is necessary to prolong the lives of those suffering from OUD.5 In-custody overdose deaths are quite rare, and access to MAT during incarceration has decreased in-custody deaths by 74%.6

Decreased opioid overdose deaths is not the only outcome of MAT. Pharmacotherapy for OUD also has been shown to increase treatment retention,7 reduce reincarceration,8 prevent communicable infections,9 and decrease use of other illicit substances.10 The provision of MAT also has been shown to be cost effective.11

Despite those benefits, as of 2017, only 30 out of 5,100 jails and prisons in the United States provided treatment with methadone or buprenorphine.12 When individuals on maintenance therapy are incarcerated, most correctional facilities force them to taper and discontinue those medications. This practice can cause distressing withdrawal symptoms and actively increase the risk of death for these individuals.

Concerns related to the provision of MAT, and specifically buprenorphine, in the correctional health setting often are related to diversion. Although safe administration of opioid full and partial agonists is a priority, recent literature has suggested that buprenorphine is not a medication frequently used for euphoric properties. In fact, the literature suggests that individuals using illicit buprenorphine primarily do so to treat withdrawal symptoms and that illicit use diminishes with access to formal treatment.13,14

Another concern is that pharmacotherapy for OUD should not be used without adjunctive psychotherapies and social supports. While dual pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is ideal, the American Society for Addiction Medicine 2020 National Practice Guidelines for the treatment of OUD state: “a patient’s decision to decline psychosocial treatment or the absence of available psychosocial treatment should not preclude or delay pharmacotherapy, with appropriate medication management.”15 Just as some patients wish to engage in mutual help or psychotherapeutic modalities only, some patients wish to engage only in psychopharmacologic interventions. Declaring one modality of treatment better, or worse, or more worthwhile is not borne out by the literature and often places clinicians’ preferences over the preferences of patients.

Individuals who suffer from substance use disorders are at high risk of incarceration, relapse, and overdose death. These patients also suffer from stigmatization from peers and health care workers alike, making the process of engaging in care incredibly burdensome. Because of the disease of addiction, many of our patients cannot envision a healthy future: a future with the potential for intimate relationships, meaningful community engagement, and a rich inner life. The provision of MAT is lifesaving and improves the chances of a successful reentry – an intuitive first step in a long, but worthwhile, journey.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al; National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, 2020 Jan, No. 356.

2. Binswanger IA et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157-65.

3. Green TC et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):405-7.

4. Marsden J et al. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1408-18.

5. Joshi V and Urada D. State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis: California Strategic Plan. 2017 Aug 30.

6. Larney S et al. BMJ Open. 2014. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004666.

7. Rich JD et al. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350-9.

8. Deck D et al. J Addict Dis. 2009. 28(2):89-102.

9. MacArthur GJ et al. BMJ. 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5945.

10. Tsui J et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019. 109:80-5.

11. Gisev N et al. Addiction. 2015 Dec;110(12):1975-84.

12. National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. “Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings.” HHS Publication No. PEP19-MATUSECJS. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019.

13. Bazazi AR et al. J Addict Med. 2011;5(3):175-80.

14. Schuman-Olivier Z. et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010 Jul;39(1):41-50.

15. Crotty K et al. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2)99-112.

Dr. Barnes is chief resident at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services in California. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Lenane is resident* at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The opinions shared in this article represent the viewpoints of the authors and are not necessarily representative of the viewpoints or policies of their academic program or employer.

*This article was updated 7/9/2020.

Opioid overdose deaths in the United States have more than tripled in recent years, from 6.1 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 1999 to 20.7 per 100,000 individuals in 2018.1 Although the availability of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) has expanded over the past decade, this lifesaving treatment remains largely inaccessible to some of the most vulnerable members of our communities: opioid users facing reentry after incarceration.

Just as abstinence in the community brings a loss of tolerance to opioids, individuals who are incarcerated lose tolerance as well. Clinicians who treat patients with opioid use disorders (OUD) are accustomed to warning patients about the risk of returning to prior levels of use too quickly. Harm reduction strategies include using slowly, using with friends, and having naloxone on hand to prevent unintended overdose.

The risks of opioid use are magnified for those facing reentry; incarceration contributes to a loss of employment, social supports, and connection to care. Those changes can create an exceptionally stressful reentry period – one that places individuals at an acutely high risk of relapse and overdose. Within the first 2 years of release, an individual with a history of incarceration has a risk of death 3.5 times higher than that of someone in the general population. Within the first 2 weeks, those recently incarcerated are 129 times more likely to overdose on opioids and 12.7 times more likely to die than members of the general population.2

Treatment with MAT dramatically reduces deaths during this crucial period. In England, large national studies have shown a similar 75% decrease in all-cause mortality within the first 4 weeks of release among individuals with OUD.4 In California, the counties with the highest overdose death rates are consistently those with fewer opioid treatment programs, which suggests that access to treatment is necessary to prolong the lives of those suffering from OUD.5 In-custody overdose deaths are quite rare, and access to MAT during incarceration has decreased in-custody deaths by 74%.6

Decreased opioid overdose deaths is not the only outcome of MAT. Pharmacotherapy for OUD also has been shown to increase treatment retention,7 reduce reincarceration,8 prevent communicable infections,9 and decrease use of other illicit substances.10 The provision of MAT also has been shown to be cost effective.11

Despite those benefits, as of 2017, only 30 out of 5,100 jails and prisons in the United States provided treatment with methadone or buprenorphine.12 When individuals on maintenance therapy are incarcerated, most correctional facilities force them to taper and discontinue those medications. This practice can cause distressing withdrawal symptoms and actively increase the risk of death for these individuals.

Concerns related to the provision of MAT, and specifically buprenorphine, in the correctional health setting often are related to diversion. Although safe administration of opioid full and partial agonists is a priority, recent literature has suggested that buprenorphine is not a medication frequently used for euphoric properties. In fact, the literature suggests that individuals using illicit buprenorphine primarily do so to treat withdrawal symptoms and that illicit use diminishes with access to formal treatment.13,14

Another concern is that pharmacotherapy for OUD should not be used without adjunctive psychotherapies and social supports. While dual pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is ideal, the American Society for Addiction Medicine 2020 National Practice Guidelines for the treatment of OUD state: “a patient’s decision to decline psychosocial treatment or the absence of available psychosocial treatment should not preclude or delay pharmacotherapy, with appropriate medication management.”15 Just as some patients wish to engage in mutual help or psychotherapeutic modalities only, some patients wish to engage only in psychopharmacologic interventions. Declaring one modality of treatment better, or worse, or more worthwhile is not borne out by the literature and often places clinicians’ preferences over the preferences of patients.

Individuals who suffer from substance use disorders are at high risk of incarceration, relapse, and overdose death. These patients also suffer from stigmatization from peers and health care workers alike, making the process of engaging in care incredibly burdensome. Because of the disease of addiction, many of our patients cannot envision a healthy future: a future with the potential for intimate relationships, meaningful community engagement, and a rich inner life. The provision of MAT is lifesaving and improves the chances of a successful reentry – an intuitive first step in a long, but worthwhile, journey.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al; National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, 2020 Jan, No. 356.

2. Binswanger IA et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157-65.

3. Green TC et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):405-7.

4. Marsden J et al. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1408-18.

5. Joshi V and Urada D. State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis: California Strategic Plan. 2017 Aug 30.

6. Larney S et al. BMJ Open. 2014. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004666.

7. Rich JD et al. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350-9.

8. Deck D et al. J Addict Dis. 2009. 28(2):89-102.

9. MacArthur GJ et al. BMJ. 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5945.

10. Tsui J et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019. 109:80-5.

11. Gisev N et al. Addiction. 2015 Dec;110(12):1975-84.

12. National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. “Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings.” HHS Publication No. PEP19-MATUSECJS. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019.

13. Bazazi AR et al. J Addict Med. 2011;5(3):175-80.

14. Schuman-Olivier Z. et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010 Jul;39(1):41-50.

15. Crotty K et al. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2)99-112.

Dr. Barnes is chief resident at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services in California. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Lenane is resident* at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The opinions shared in this article represent the viewpoints of the authors and are not necessarily representative of the viewpoints or policies of their academic program or employer.

*This article was updated 7/9/2020.

Amid pandemic, Virginia hospital’s opioid overdoses up nearly 10-fold

Opioid overdoses have shot up by almost 10-fold at a Virginia ED since March, a new report finds. The report provides more evidence that the coronavirus pandemic is sparking a severe medical crisis among illicit drug users.

“Health care providers should closely monitor the number of overdoses coming into their hospitals and in the surrounding community during this time,” study lead author and postdoctoral research fellow Taylor Ochalek, PhD, said in an interview. “If they do notice an increasing trend of overdoses, they should spread awareness in the community to the general public, and offer resources and information for those that may be seeking help and/or may be at a high risk of overdosing.”

Dr. Ochalek presented the study findings at the virtual annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

According to the report, opioid overdoses at the VCU Medical Center in Richmond, Va., grew from an average of six a month from February to December 2019 to 50, 57, and 63 in March, April, and May 2020. Of the 171 cases in the later time frame, the average age was 44 years, 72% were male, and 82% were African American.

“The steep increase in overdoses began primarily in March,” said Dr. Ochalek, of Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. “This timing coincides with the Virginia governor’s state of emergency declaration, stay-at-home order, and closure of nonessential businesses order.”

The researchers did not provide details about the types of opioids used, the patient outcomes, or whether the patients tested positive for COVID-19. It’s unclear whether the pandemic directly spawned a higher number of overdoses, but there are growing signs of a stark nationwide trend.

“Nationwide, federal and local officials are reporting alarming spikes in drug overdoses – a hidden epidemic within the coronavirus pandemic,” the Washington Post reported on July 1, pointing to increases in Kentucky, Virginia, and the Chicago area.

Meanwhile, the federal Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program, which tracks overdoses nationwide, issued 191% more “spike alerts” in January to April 2020 than in the same time period in 2019. However, the spike alerts began to increase in January, weeks before the pandemic began to take hold.

The findings are consistent with trends in Houston, where overdose calls were up 31% in the first 3 months of 2020, compared with 2019, said psychologist James Bray, PhD, of the University of Texas, San Antonio, in an interview. More recent data suggest that the numbers are rising even higher, said Dr. Bray, who works with Houston first responders and has analyzed data.

Dr. Bray said.

Another potential factor is the disruption in the illicit drug supply chain because of limits on crossings at the southern border, said ED physician Scott Weiner, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “As a result, opioids of extremely variable potency have infiltrated markets, and people using drugs may not be used to the new doses, especially if they are high-potency fentanyl analogues.”

Moving forward, Dr. Bray said, “people need continued access to treatment. Telehealth and other virtual services need to be provided so that people can continue to have access to treatment even during the pandemic.”

Dr. Weiner also emphasized the importance of treatment for patients who overdose on opioids. “In my previous work, we discovered that about 1 in 20 patients who are treated in an emergency department and survive would die within 1 year. That number will likely increase drastically during COVID,” he said. “When a patient presents after overdose, we must intervene aggressively with buprenorphine and other harm-reduction techniques to save these lives.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Ochalek, Dr. Weiner, and Dr. Bray reported no relevant disclosures.

Opioid overdoses have shot up by almost 10-fold at a Virginia ED since March, a new report finds. The report provides more evidence that the coronavirus pandemic is sparking a severe medical crisis among illicit drug users.

“Health care providers should closely monitor the number of overdoses coming into their hospitals and in the surrounding community during this time,” study lead author and postdoctoral research fellow Taylor Ochalek, PhD, said in an interview. “If they do notice an increasing trend of overdoses, they should spread awareness in the community to the general public, and offer resources and information for those that may be seeking help and/or may be at a high risk of overdosing.”

Dr. Ochalek presented the study findings at the virtual annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

According to the report, opioid overdoses at the VCU Medical Center in Richmond, Va., grew from an average of six a month from February to December 2019 to 50, 57, and 63 in March, April, and May 2020. Of the 171 cases in the later time frame, the average age was 44 years, 72% were male, and 82% were African American.

“The steep increase in overdoses began primarily in March,” said Dr. Ochalek, of Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. “This timing coincides with the Virginia governor’s state of emergency declaration, stay-at-home order, and closure of nonessential businesses order.”

The researchers did not provide details about the types of opioids used, the patient outcomes, or whether the patients tested positive for COVID-19. It’s unclear whether the pandemic directly spawned a higher number of overdoses, but there are growing signs of a stark nationwide trend.

“Nationwide, federal and local officials are reporting alarming spikes in drug overdoses – a hidden epidemic within the coronavirus pandemic,” the Washington Post reported on July 1, pointing to increases in Kentucky, Virginia, and the Chicago area.

Meanwhile, the federal Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program, which tracks overdoses nationwide, issued 191% more “spike alerts” in January to April 2020 than in the same time period in 2019. However, the spike alerts began to increase in January, weeks before the pandemic began to take hold.

The findings are consistent with trends in Houston, where overdose calls were up 31% in the first 3 months of 2020, compared with 2019, said psychologist James Bray, PhD, of the University of Texas, San Antonio, in an interview. More recent data suggest that the numbers are rising even higher, said Dr. Bray, who works with Houston first responders and has analyzed data.

Dr. Bray said.

Another potential factor is the disruption in the illicit drug supply chain because of limits on crossings at the southern border, said ED physician Scott Weiner, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “As a result, opioids of extremely variable potency have infiltrated markets, and people using drugs may not be used to the new doses, especially if they are high-potency fentanyl analogues.”

Moving forward, Dr. Bray said, “people need continued access to treatment. Telehealth and other virtual services need to be provided so that people can continue to have access to treatment even during the pandemic.”

Dr. Weiner also emphasized the importance of treatment for patients who overdose on opioids. “In my previous work, we discovered that about 1 in 20 patients who are treated in an emergency department and survive would die within 1 year. That number will likely increase drastically during COVID,” he said. “When a patient presents after overdose, we must intervene aggressively with buprenorphine and other harm-reduction techniques to save these lives.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Ochalek, Dr. Weiner, and Dr. Bray reported no relevant disclosures.

Opioid overdoses have shot up by almost 10-fold at a Virginia ED since March, a new report finds. The report provides more evidence that the coronavirus pandemic is sparking a severe medical crisis among illicit drug users.

“Health care providers should closely monitor the number of overdoses coming into their hospitals and in the surrounding community during this time,” study lead author and postdoctoral research fellow Taylor Ochalek, PhD, said in an interview. “If they do notice an increasing trend of overdoses, they should spread awareness in the community to the general public, and offer resources and information for those that may be seeking help and/or may be at a high risk of overdosing.”

Dr. Ochalek presented the study findings at the virtual annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

According to the report, opioid overdoses at the VCU Medical Center in Richmond, Va., grew from an average of six a month from February to December 2019 to 50, 57, and 63 in March, April, and May 2020. Of the 171 cases in the later time frame, the average age was 44 years, 72% were male, and 82% were African American.

“The steep increase in overdoses began primarily in March,” said Dr. Ochalek, of Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. “This timing coincides with the Virginia governor’s state of emergency declaration, stay-at-home order, and closure of nonessential businesses order.”

The researchers did not provide details about the types of opioids used, the patient outcomes, or whether the patients tested positive for COVID-19. It’s unclear whether the pandemic directly spawned a higher number of overdoses, but there are growing signs of a stark nationwide trend.

“Nationwide, federal and local officials are reporting alarming spikes in drug overdoses – a hidden epidemic within the coronavirus pandemic,” the Washington Post reported on July 1, pointing to increases in Kentucky, Virginia, and the Chicago area.

Meanwhile, the federal Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program, which tracks overdoses nationwide, issued 191% more “spike alerts” in January to April 2020 than in the same time period in 2019. However, the spike alerts began to increase in January, weeks before the pandemic began to take hold.

The findings are consistent with trends in Houston, where overdose calls were up 31% in the first 3 months of 2020, compared with 2019, said psychologist James Bray, PhD, of the University of Texas, San Antonio, in an interview. More recent data suggest that the numbers are rising even higher, said Dr. Bray, who works with Houston first responders and has analyzed data.

Dr. Bray said.

Another potential factor is the disruption in the illicit drug supply chain because of limits on crossings at the southern border, said ED physician Scott Weiner, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “As a result, opioids of extremely variable potency have infiltrated markets, and people using drugs may not be used to the new doses, especially if they are high-potency fentanyl analogues.”

Moving forward, Dr. Bray said, “people need continued access to treatment. Telehealth and other virtual services need to be provided so that people can continue to have access to treatment even during the pandemic.”

Dr. Weiner also emphasized the importance of treatment for patients who overdose on opioids. “In my previous work, we discovered that about 1 in 20 patients who are treated in an emergency department and survive would die within 1 year. That number will likely increase drastically during COVID,” he said. “When a patient presents after overdose, we must intervene aggressively with buprenorphine and other harm-reduction techniques to save these lives.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Ochalek, Dr. Weiner, and Dr. Bray reported no relevant disclosures.

FROM CPDD 2020

Use of nonopioid pain meds is on the rise

Opioid and nonopioid prescription pain medications have taken different journeys since 2009, but they ended up in the same place in 2018, according to a recent report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

At least by one measure, anyway. Survey data from 2009 to 2010 show that 6.2% of adults aged 20 years and older had taken at least one prescription opioid in the last 30 days and 4.3% had used a prescription nonopioid without an opioid. By 2017-2018, past 30-day use of both drug groups was 5.7%, Craig M. Hales, MD, and associates said in an NCHS data brief.

“Opioids may be prescribed together with nonopioid pain medications, [but] nonpharmacologic and nonopioid-containing pharmacologic therapies are preferred for management of chronic pain,” the NCHS researchers noted.

as did the short-term increase in nonopioids from 2015-2016 to 2017-2018, but the 10-year trend for opioids was not significant, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Much of the analysis focused on 2015-2018, when 30-day use of any prescription pain medication was reported by 10.7% of adults aged 20 years and older, with use of opioids at 5.7% and nonopioids at 5.0%. For women, use of any pain drug was 12.6% (6.4% opioid, 6.2% nonopioid) from 2015 to 2018, compared with 8.7% for men (4.9%, 3.8%), Dr. Hales and associates reported.

Past 30-day use of both opioids and nonopioids over those 4 years was highest for non-Hispanic whites and lowest, by a significant margin for both drug groups, among non-Hispanic Asian adults, a pattern that held for both men and women, they said.

Opioid and nonopioid prescription pain medications have taken different journeys since 2009, but they ended up in the same place in 2018, according to a recent report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

At least by one measure, anyway. Survey data from 2009 to 2010 show that 6.2% of adults aged 20 years and older had taken at least one prescription opioid in the last 30 days and 4.3% had used a prescription nonopioid without an opioid. By 2017-2018, past 30-day use of both drug groups was 5.7%, Craig M. Hales, MD, and associates said in an NCHS data brief.

“Opioids may be prescribed together with nonopioid pain medications, [but] nonpharmacologic and nonopioid-containing pharmacologic therapies are preferred for management of chronic pain,” the NCHS researchers noted.

as did the short-term increase in nonopioids from 2015-2016 to 2017-2018, but the 10-year trend for opioids was not significant, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Much of the analysis focused on 2015-2018, when 30-day use of any prescription pain medication was reported by 10.7% of adults aged 20 years and older, with use of opioids at 5.7% and nonopioids at 5.0%. For women, use of any pain drug was 12.6% (6.4% opioid, 6.2% nonopioid) from 2015 to 2018, compared with 8.7% for men (4.9%, 3.8%), Dr. Hales and associates reported.

Past 30-day use of both opioids and nonopioids over those 4 years was highest for non-Hispanic whites and lowest, by a significant margin for both drug groups, among non-Hispanic Asian adults, a pattern that held for both men and women, they said.

Opioid and nonopioid prescription pain medications have taken different journeys since 2009, but they ended up in the same place in 2018, according to a recent report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

At least by one measure, anyway. Survey data from 2009 to 2010 show that 6.2% of adults aged 20 years and older had taken at least one prescription opioid in the last 30 days and 4.3% had used a prescription nonopioid without an opioid. By 2017-2018, past 30-day use of both drug groups was 5.7%, Craig M. Hales, MD, and associates said in an NCHS data brief.

“Opioids may be prescribed together with nonopioid pain medications, [but] nonpharmacologic and nonopioid-containing pharmacologic therapies are preferred for management of chronic pain,” the NCHS researchers noted.

as did the short-term increase in nonopioids from 2015-2016 to 2017-2018, but the 10-year trend for opioids was not significant, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Much of the analysis focused on 2015-2018, when 30-day use of any prescription pain medication was reported by 10.7% of adults aged 20 years and older, with use of opioids at 5.7% and nonopioids at 5.0%. For women, use of any pain drug was 12.6% (6.4% opioid, 6.2% nonopioid) from 2015 to 2018, compared with 8.7% for men (4.9%, 3.8%), Dr. Hales and associates reported.

Past 30-day use of both opioids and nonopioids over those 4 years was highest for non-Hispanic whites and lowest, by a significant margin for both drug groups, among non-Hispanic Asian adults, a pattern that held for both men and women, they said.

High percentage of stimulant use found in opioid ED cases

Nearly 40% of hundreds of opioid abusers at several emergency departments tested positive for stimulants, and they were more likely to be white than other users, a new study finds. Reflecting national trends, patients in the Midwest and West Coast regions were more likely to show signs of stimulant use.

Stimulant/opioid users were also “younger, with unstable housing, mostly unemployed, and reported high rates of recent incarcerations,” said substance use researcher and study lead author Marek Chawarski, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn. “They also reported higher rates of injection drug use during 1 month prior to the study admission and had higher rates of HCV infection. And higher proportions of amphetamine-type stimulant (ATS)–positive patients presented in the emergency departments (EDs) for an injury or with drug overdose.”

Dr. Chawarski, who presented the study findings at the virtual annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, said in an interview that the study is the first to analyze stimulant use in ED patients with opioid use disorder.

The researchers analyzed data for the period 2017-2019 from EDs in Baltimore, New York, Cincinnati, and Seattle. Out of 396 patients, 150 (38%) were positive for amphetamine-type stimulants.

Patients in the Midwest and West Coast were more likely to test positive (38%).

In general, stimulant use is higher in the Midwest and West Coast, said epidemiologist Brandon Marshall, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., in an interview. “This is due to a number of supply-side, historical, and cultural reasons. New England, Appalachia, and large urban centers on the East Coast are the historical hot spots for opioid use, while states west of the Mississippi River have lower rates of opioid overdose, but a much higher prevalence of ATS use and stimulant-related morbidity and mortality.”

Those who showed signs of stimulant use were more likely to be white (69%) vs. the nonusers (46%), and were more likely to have unstable housing (67% vs. 49%).

Those who used stimulants also were more likely to be suffering from an overdose (23% vs. 13%) and to report injecting drugs in the last month (79% vs. 47%). More had unstable housing (67% vs. 49%, P < .05 for all comparisons).

Dr. Chawarski said there are many reasons why users might use more than one kind of drug. For example, they may take one drug to “alleviate problems created by the use of one substance with taking another substance and multiple other reasons,” he said. “Polysubstance use can exacerbate social and medical harms, including overdose risk. It can pose greater treatment challenges, both for the patients and treatment providers, and often is more difficult to overcome.”

Links between opioid and stimulant use are not new. Last year, a study of 2,244 opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts from 2014 to 2015 found that 36% of patients also showed signs of stimulant use. “Persons older than 24 years, nonrural residents, those with comorbid mental illness, non-Hispanic black residents, and persons with recent homelessness were more likely than their counterparts to die with opioids and stimulants than opioids alone,” the researchers reported (Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019 Jul 1;200:59-63).

Dr. Marshall said the study findings are not surprising. However, he said, they do indicate “ongoing, intentional consumption of opioids. The trends and characteristics we are seeing here suggests a large population of persons who are intentionally using both stimulants and opioids, many of whom are also injecting.”

He added that the study sample is probably higher risk than the general population since they’re presenting to the emergency department, so the findings might not reflect the use of stimulants in the general opioid-misusing population.

Dr. Marshall added that “there have been several instances in modern U.S. history during which increases in stimulant use follow a rise in opioid use, so the pattern we are seeing isn’t entirely surprising.”

“What we don’t know,” he added, “is the extent to which overdoses involving both an opioid and a stimulant are due to fentanyl contamination of the methamphetamine supply or intentional concurrent use – e.g., ‘speedballing’ or ‘goof balling’ – or some other pattern of polysubstance use, such as using an opioid to come down off a methamphetamine high.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse funded the study. The study authors reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Marshall reported that he has collaborated frequently with two of the study coauthors.

Nearly 40% of hundreds of opioid abusers at several emergency departments tested positive for stimulants, and they were more likely to be white than other users, a new study finds. Reflecting national trends, patients in the Midwest and West Coast regions were more likely to show signs of stimulant use.

Stimulant/opioid users were also “younger, with unstable housing, mostly unemployed, and reported high rates of recent incarcerations,” said substance use researcher and study lead author Marek Chawarski, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn. “They also reported higher rates of injection drug use during 1 month prior to the study admission and had higher rates of HCV infection. And higher proportions of amphetamine-type stimulant (ATS)–positive patients presented in the emergency departments (EDs) for an injury or with drug overdose.”

Dr. Chawarski, who presented the study findings at the virtual annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, said in an interview that the study is the first to analyze stimulant use in ED patients with opioid use disorder.

The researchers analyzed data for the period 2017-2019 from EDs in Baltimore, New York, Cincinnati, and Seattle. Out of 396 patients, 150 (38%) were positive for amphetamine-type stimulants.

Patients in the Midwest and West Coast were more likely to test positive (38%).

In general, stimulant use is higher in the Midwest and West Coast, said epidemiologist Brandon Marshall, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., in an interview. “This is due to a number of supply-side, historical, and cultural reasons. New England, Appalachia, and large urban centers on the East Coast are the historical hot spots for opioid use, while states west of the Mississippi River have lower rates of opioid overdose, but a much higher prevalence of ATS use and stimulant-related morbidity and mortality.”

Those who showed signs of stimulant use were more likely to be white (69%) vs. the nonusers (46%), and were more likely to have unstable housing (67% vs. 49%).

Those who used stimulants also were more likely to be suffering from an overdose (23% vs. 13%) and to report injecting drugs in the last month (79% vs. 47%). More had unstable housing (67% vs. 49%, P < .05 for all comparisons).

Dr. Chawarski said there are many reasons why users might use more than one kind of drug. For example, they may take one drug to “alleviate problems created by the use of one substance with taking another substance and multiple other reasons,” he said. “Polysubstance use can exacerbate social and medical harms, including overdose risk. It can pose greater treatment challenges, both for the patients and treatment providers, and often is more difficult to overcome.”

Links between opioid and stimulant use are not new. Last year, a study of 2,244 opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts from 2014 to 2015 found that 36% of patients also showed signs of stimulant use. “Persons older than 24 years, nonrural residents, those with comorbid mental illness, non-Hispanic black residents, and persons with recent homelessness were more likely than their counterparts to die with opioids and stimulants than opioids alone,” the researchers reported (Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019 Jul 1;200:59-63).

Dr. Marshall said the study findings are not surprising. However, he said, they do indicate “ongoing, intentional consumption of opioids. The trends and characteristics we are seeing here suggests a large population of persons who are intentionally using both stimulants and opioids, many of whom are also injecting.”

He added that the study sample is probably higher risk than the general population since they’re presenting to the emergency department, so the findings might not reflect the use of stimulants in the general opioid-misusing population.

Dr. Marshall added that “there have been several instances in modern U.S. history during which increases in stimulant use follow a rise in opioid use, so the pattern we are seeing isn’t entirely surprising.”

“What we don’t know,” he added, “is the extent to which overdoses involving both an opioid and a stimulant are due to fentanyl contamination of the methamphetamine supply or intentional concurrent use – e.g., ‘speedballing’ or ‘goof balling’ – or some other pattern of polysubstance use, such as using an opioid to come down off a methamphetamine high.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse funded the study. The study authors reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Marshall reported that he has collaborated frequently with two of the study coauthors.

Nearly 40% of hundreds of opioid abusers at several emergency departments tested positive for stimulants, and they were more likely to be white than other users, a new study finds. Reflecting national trends, patients in the Midwest and West Coast regions were more likely to show signs of stimulant use.

Stimulant/opioid users were also “younger, with unstable housing, mostly unemployed, and reported high rates of recent incarcerations,” said substance use researcher and study lead author Marek Chawarski, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn. “They also reported higher rates of injection drug use during 1 month prior to the study admission and had higher rates of HCV infection. And higher proportions of amphetamine-type stimulant (ATS)–positive patients presented in the emergency departments (EDs) for an injury or with drug overdose.”

Dr. Chawarski, who presented the study findings at the virtual annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, said in an interview that the study is the first to analyze stimulant use in ED patients with opioid use disorder.

The researchers analyzed data for the period 2017-2019 from EDs in Baltimore, New York, Cincinnati, and Seattle. Out of 396 patients, 150 (38%) were positive for amphetamine-type stimulants.

Patients in the Midwest and West Coast were more likely to test positive (38%).

In general, stimulant use is higher in the Midwest and West Coast, said epidemiologist Brandon Marshall, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., in an interview. “This is due to a number of supply-side, historical, and cultural reasons. New England, Appalachia, and large urban centers on the East Coast are the historical hot spots for opioid use, while states west of the Mississippi River have lower rates of opioid overdose, but a much higher prevalence of ATS use and stimulant-related morbidity and mortality.”

Those who showed signs of stimulant use were more likely to be white (69%) vs. the nonusers (46%), and were more likely to have unstable housing (67% vs. 49%).

Those who used stimulants also were more likely to be suffering from an overdose (23% vs. 13%) and to report injecting drugs in the last month (79% vs. 47%). More had unstable housing (67% vs. 49%, P < .05 for all comparisons).

Dr. Chawarski said there are many reasons why users might use more than one kind of drug. For example, they may take one drug to “alleviate problems created by the use of one substance with taking another substance and multiple other reasons,” he said. “Polysubstance use can exacerbate social and medical harms, including overdose risk. It can pose greater treatment challenges, both for the patients and treatment providers, and often is more difficult to overcome.”

Links between opioid and stimulant use are not new. Last year, a study of 2,244 opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts from 2014 to 2015 found that 36% of patients also showed signs of stimulant use. “Persons older than 24 years, nonrural residents, those with comorbid mental illness, non-Hispanic black residents, and persons with recent homelessness were more likely than their counterparts to die with opioids and stimulants than opioids alone,” the researchers reported (Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019 Jul 1;200:59-63).

Dr. Marshall said the study findings are not surprising. However, he said, they do indicate “ongoing, intentional consumption of opioids. The trends and characteristics we are seeing here suggests a large population of persons who are intentionally using both stimulants and opioids, many of whom are also injecting.”

He added that the study sample is probably higher risk than the general population since they’re presenting to the emergency department, so the findings might not reflect the use of stimulants in the general opioid-misusing population.

Dr. Marshall added that “there have been several instances in modern U.S. history during which increases in stimulant use follow a rise in opioid use, so the pattern we are seeing isn’t entirely surprising.”

“What we don’t know,” he added, “is the extent to which overdoses involving both an opioid and a stimulant are due to fentanyl contamination of the methamphetamine supply or intentional concurrent use – e.g., ‘speedballing’ or ‘goof balling’ – or some other pattern of polysubstance use, such as using an opioid to come down off a methamphetamine high.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse funded the study. The study authors reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Marshall reported that he has collaborated frequently with two of the study coauthors.

FROM CPDD 2020

App links overdosing people to nearby volunteers with naloxone

Naloxone can reverse opioid overdoses, but time is crucial and its effectiveness wanes if medics can’t arrive right away. Now, a new app links overdose victims or their companions to trained volunteers nearby who may be able to administer the drug much faster.

Over a 1-year period, about half of 112 participants in a Philadelphia trial said they’d responded to overdoses via the app, and about half used it to report overdoses, according to a study released at the virtual annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

“Thanks to the app, there may have been a life saved about twice a month that otherwise wouldn’t have been,” said public health researcher and study coauthor Stephen Lankenau, PhD, of Drexel University, Philadelphia, in an interview.

Philadelphia has the largest opioid overdose rate of any large city, Dr. Lankenau said, and people who overdose are often reluctant to call 911. “Police are often alerted when it’s determined that it’s a drug-related call. They’re concerned that police could show up and someone will get arrested.”

However, the app, called UnityPhilly, doesn’t remove professional medics from the picture. It’s designed to be a supplement to the existing first-response system – “it’s not meant to replace 911” – and allow a faster response to overdoses when minutes matter, Dr. Lankenau said.

“If someone is adamantly opposed to calling 911,” he said, “this may not be the best intervention for them.”

Here’s how the app works: Participants who overdose themselves or witness an overdose can send out an alert to nearby app users. When an alert goes out, the app also attempts to dial 911, although the participant can bypass this.

Nearby responders can reply by pressing “En route” and then go to the address of the overdose with a provided supply of naloxone (Narcan). The amateur responders, many of whom are or were opioid users themselves, are trained in how to administer the drug.

The study authors recruited 112 participants from the Philadelphia neighborhood of Kensington and tracked them from 2019 to 2020. About half (n = 57) reported using opioids within the past 30 days, and those participants had an average age of 42 years, were 54% men, and were 74% non-Hispanic white. Only 19% were employed, and 42% had been recently homeless. Nearly 80% had overdosed before, and all had witnessed overdoses.

The other participants (n = 55), defined as “community members,” had less experience with opioids (44% had misused them before), although 91% had witnessed overdoses. Their average age was 42 years, 56% were women, 53% were employed, and 16% had been recently homeless.

The percentages who reported being en route to an overdose was 47% (opioid users) and 46% (community members).

“The idea of people being trained as community responders has been around for quite a while, and there are hundreds of programs across the country. People are willing to carry naloxone and respond if they see an overdose in front of them,” Dr. Lankenau said. “Here, you have people becoming civilian responders to events they wouldn’t otherwise know about. This creates a community of individuals who can help out immediately and augment the work that emergency responders do.”

Opioid users who download the app may be drawn to the idea of responders who are nonjudgmental and supportive, compared with professional medics. “The system has not done well by people with substance abuse disorders,” said addiction medicine specialist Sukhpreet Klaire, MD, of the British Columbia Center on Substance Use in Vancouver. “In terms of overdose reversal, you may prefer that someone else [other than a medic] give you Narcan and support you through this experience. When it’s over after you’re reversed, you have a sudden onset of withdrawal symptoms. You feel terrible, and you don’t want to be sitting in an ambulance. You want to be in a supportive environment.”

As for adverse effects, there was concern that opioid users might take more risks with an app safety net in place. However, no one reported more risky behavior in interviews, Dr. Lankenau said.

The 3-year program costs $215,000, he said, and the next step is to get funding for a Philadelphia citywide trial.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Dr. Lankenau reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Klaire disclosed participating in a research fellowship and a research in addiction medical scholars program, both funded by NIDA.

Naloxone can reverse opioid overdoses, but time is crucial and its effectiveness wanes if medics can’t arrive right away. Now, a new app links overdose victims or their companions to trained volunteers nearby who may be able to administer the drug much faster.

Over a 1-year period, about half of 112 participants in a Philadelphia trial said they’d responded to overdoses via the app, and about half used it to report overdoses, according to a study released at the virtual annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

“Thanks to the app, there may have been a life saved about twice a month that otherwise wouldn’t have been,” said public health researcher and study coauthor Stephen Lankenau, PhD, of Drexel University, Philadelphia, in an interview.

Philadelphia has the largest opioid overdose rate of any large city, Dr. Lankenau said, and people who overdose are often reluctant to call 911. “Police are often alerted when it’s determined that it’s a drug-related call. They’re concerned that police could show up and someone will get arrested.”

However, the app, called UnityPhilly, doesn’t remove professional medics from the picture. It’s designed to be a supplement to the existing first-response system – “it’s not meant to replace 911” – and allow a faster response to overdoses when minutes matter, Dr. Lankenau said.

“If someone is adamantly opposed to calling 911,” he said, “this may not be the best intervention for them.”

Here’s how the app works: Participants who overdose themselves or witness an overdose can send out an alert to nearby app users. When an alert goes out, the app also attempts to dial 911, although the participant can bypass this.

Nearby responders can reply by pressing “En route” and then go to the address of the overdose with a provided supply of naloxone (Narcan). The amateur responders, many of whom are or were opioid users themselves, are trained in how to administer the drug.

The study authors recruited 112 participants from the Philadelphia neighborhood of Kensington and tracked them from 2019 to 2020. About half (n = 57) reported using opioids within the past 30 days, and those participants had an average age of 42 years, were 54% men, and were 74% non-Hispanic white. Only 19% were employed, and 42% had been recently homeless. Nearly 80% had overdosed before, and all had witnessed overdoses.

The other participants (n = 55), defined as “community members,” had less experience with opioids (44% had misused them before), although 91% had witnessed overdoses. Their average age was 42 years, 56% were women, 53% were employed, and 16% had been recently homeless.

The percentages who reported being en route to an overdose was 47% (opioid users) and 46% (community members).