User login

How to identify, evaluate, and treat patients with ‘Percocet use disorder’

In recent years, Percocet (oxycodone/paracetamol) has experienced a meteoric rise to prominence because of the presence of conspicuous references in pop culture and the ever-evolving hip-hop scene,1 so much so that even propafenone is being mislabeled as the agent.2 It is of utmost importance for clinicians to be made aware of the adverse effects and the treatment protocols associated with Percocet as well as propafenone.

Propafenone is identified as a class 1C antiarrhythmic with adverse effects associated with that particular class of drugs (e.g., generalized tonic-clonic seizures coupled with widened QRS complex), however, Percocet’s toxidrome is the product of the opioid/nonopioid (in the form of oxycodone/acetaminophen) components found within the formulation. Percocet is often recreationally used with MDMA (“molly”) or ecstasy as popularized by the lyrics of “Mask Off” by Future (“Percocets, Molly, Percocets”).3,4

Addressing the challenge of imitation Percocet pills

Differentiating the untoward effects of Percocet and propafenone isn’t too challenging because the agents belong to separate classes – the problem is the use of deceitful labels on propafenone with both medications sporting the “512 imprint” on their respective pills. Initial symptoms of propafenone ingestion may include weakness and dizziness followed by seizures.5As an emergent situation, the patient should be immediately treated with a sodium bicarbonate infusion to effectively reverse the sodium channel blockade associated with the widened QRS.

However, a more likely scenario is that of Percocet counterfeit pills designed to illicitly emulate the properties of officially marketed Percocet. As expected, Percocet overdose management will require that the clinician be familiar with treating general opioid toxicity (in this case, derived from the oxycodone component), in particular respiratory or CNS depression. Symptoms of opioid overdose also include the loss of consciousness with pupillary miosis. Therapy entails the use of naloxone and/or mechanical ventilation for respiratory support. The patient can also exhibit cardiovascular compromise. If further information is elicited during a patient interview, it may reveal a history of drug procurement from the streets.

Epidemiologists from Georgia collaborated with the state’s department of public health’s office of emergency services, forensic experts, and drug enforcement professionals to evaluate almost 40 cases of counterfeit Percocet overdoses during the period spanning the second week of June 2017. Of these cases, a cluster triad was identified consisting of general opioid toxicity symptoms (for example, CNS or respiratory depression with concomitant pupillary constriction, a history of drug procurement, and a history of ingesting only one or two pills with rapid deterioration.6 Unfortunately, the screening process is often hindered by the fact that synthetic opioids such as Percocet are not readily identified on urine drug screens (UDS).

Despite shortcomings in assessment procedures, a UDS will yield positive results for multiple drugs, a feature that is common to seasoned opioid users and serves as an instrumental diagnostic clue in the investigative process. To address the crisis and prevent further spread, numerous Georgia agencies (e.g., drug trafficking and legal authorities) worked with the health care community to expediently identify cases of interest and bring forth public awareness concerning the ongoing perils of counterfeit drug intake. Future investigations might benefit from the implementation of DNA-verified UDS, because those screens are versatile enough to detect the presence of synthetic urine substitutes within the context of opioid use.7,8 Moreover, an expanded panel could be tailored to provide coverage for semisynthetics, including hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and oxymorphone.9

As a well-received painkiller from the opioid family, Percocet derives its analgesic properties from the fast-acting oxycodone; hepatic failure is also possible from Percocet (because of the acetaminophen component) or counterfeit Percocet overdose but is less common unless the Tylenol content approaches 4 grams. By binding to the brain’s opiate receptors, Percocet modulates pain pathways leading to a dulling of pain sensation along with euphoria, which is particularly attractive to drug seekers. Chronic Percocet use corresponds with a myriad of psychological and physical consequences, and the Drug Enforcement Administration recognizes oxycodone as a Schedule II drug.

A chronic Percocet user may try to disrupt the cycle of symptoms by abruptly ceasing use of the offending agent. This can precipitate the development of classical opioid-based withdrawal symptoms, including but not limited to nausea, vomiting, irritability, tachycardia, body aches, and episodes of cold sweats. Physicians have noted that misuse (i.e., deviations from intended prescribed) might include crushing and snorting as well as “doctor-shopping” behaviors for a continuous supply of Percocet.

Treatment recommendations

According to Sarah Wakeman, MD, medical director of the substance use disorders initiative at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, there are apparently two clinical manifestations of Percocet use. The primary consequence is derived from the oxycodone component of Percocet; as an opioid, oxycodone toxicity leads to disrupted breathing and oxygenation, negatively impacting vital organs such as the brain or the heart. Patients experiencing a lack of oxygen will often display cyanosis and may not respond appropriately to stimuli. For individuals suspected of succumbing to overdose, Dr. Wakeman reportedly advised that the clinician or trained professional rub his or her knuckles along the breastbone of the potential user – a drug overdose patient will fail to wake up. On the other hand, a Percocet user may exhibit the symptoms of liver failure depending on the overall level of acetaminophen in the formulation. To prevent relapses, Percocet use disorder is best managed in a professional setting under the direction of trained clinicians; users are provided medications to address ongoing cravings and symptoms associated with the withdrawal process. A detoxification center can tailor the treatment with opioid-based medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone to help patients be weaned off Percocet.

Clinicians may further improve the efficacy of a therapeutic regimen by incorporating a personalized plan with a comprehensive substance UDS panel for monitoring and treatment purposes. This may prove to be beneficial in the event of suspected polysubstance use, as is the case with patients who dabble with Percocet and “molly.” Preparations can also be instituted at the outset of therapy with genetic testing implemented in high-risk patients who exhibit an inclination for opioid use disorder.10 Genetic polymorphisms provide robust clinical assets for evaluating patients most at risk for relapse. For individuals with biological susceptibility, arrangements can be made to incorporate nonopioid treatment alternatives.

References

1. Thomas BB. The death of Lil Peep: How the U.S. prescription drug epidemic is changing hip-hop. The Guardian. 2017 Nov 16.

2. D’Orazio JL and Curtis JA. J Emer Med. 2011 Aug 1;41(2):172-5.

3. Levy L. These are the drugs influencing pop culture now. Vulture. 2018 Feb 6.

4. Kounang N and Bender M. “What is Percocet? Drug facts, side effects, abuse and more.” CNN. 2018 Jul 12.

5. The dangers of Percocet use and overdose. American Addiction Centers. Last updated 2020 Feb 3. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/percocet-treatment/dangers-of-use-and-overdose.

6. Edison L et al. MMWR. 2017 Oct 20;66(41):1119-20.

7. Choudhry Z et al. J Psychiatry. 2015. doi: 10.4172/2378-5756.10000319.

8. Islam F and Choudhry Z. Current Psychiatry. 2018 Dec;17(12):43-4.

9. Jupe N. Ask the Experts: DOT 5-panel drug test regimen. Quest Diagnostics. 2018 Mar 21. https://blog.employersolutions.com/ask-experts-dot-5-panel-drug-test-regimen/.

10. Ahmed S et al. Pharmacogenomics. 2019 Jun 28;20(9):685-703.

Dr. Islam is a medical adviser for the International Maternal and Child Health Foundation, Montreal, and is based in New York. He also is a postdoctoral fellow, psychopharmacologist, and a board-certified medical affairs specialist. Dr. Islam reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Choudhry is the chief scientific officer and head of the department of mental health and clinical research at the IMCHF. He reported no relevant disclosures.

In recent years, Percocet (oxycodone/paracetamol) has experienced a meteoric rise to prominence because of the presence of conspicuous references in pop culture and the ever-evolving hip-hop scene,1 so much so that even propafenone is being mislabeled as the agent.2 It is of utmost importance for clinicians to be made aware of the adverse effects and the treatment protocols associated with Percocet as well as propafenone.

Propafenone is identified as a class 1C antiarrhythmic with adverse effects associated with that particular class of drugs (e.g., generalized tonic-clonic seizures coupled with widened QRS complex), however, Percocet’s toxidrome is the product of the opioid/nonopioid (in the form of oxycodone/acetaminophen) components found within the formulation. Percocet is often recreationally used with MDMA (“molly”) or ecstasy as popularized by the lyrics of “Mask Off” by Future (“Percocets, Molly, Percocets”).3,4

Addressing the challenge of imitation Percocet pills

Differentiating the untoward effects of Percocet and propafenone isn’t too challenging because the agents belong to separate classes – the problem is the use of deceitful labels on propafenone with both medications sporting the “512 imprint” on their respective pills. Initial symptoms of propafenone ingestion may include weakness and dizziness followed by seizures.5As an emergent situation, the patient should be immediately treated with a sodium bicarbonate infusion to effectively reverse the sodium channel blockade associated with the widened QRS.

However, a more likely scenario is that of Percocet counterfeit pills designed to illicitly emulate the properties of officially marketed Percocet. As expected, Percocet overdose management will require that the clinician be familiar with treating general opioid toxicity (in this case, derived from the oxycodone component), in particular respiratory or CNS depression. Symptoms of opioid overdose also include the loss of consciousness with pupillary miosis. Therapy entails the use of naloxone and/or mechanical ventilation for respiratory support. The patient can also exhibit cardiovascular compromise. If further information is elicited during a patient interview, it may reveal a history of drug procurement from the streets.

Epidemiologists from Georgia collaborated with the state’s department of public health’s office of emergency services, forensic experts, and drug enforcement professionals to evaluate almost 40 cases of counterfeit Percocet overdoses during the period spanning the second week of June 2017. Of these cases, a cluster triad was identified consisting of general opioid toxicity symptoms (for example, CNS or respiratory depression with concomitant pupillary constriction, a history of drug procurement, and a history of ingesting only one or two pills with rapid deterioration.6 Unfortunately, the screening process is often hindered by the fact that synthetic opioids such as Percocet are not readily identified on urine drug screens (UDS).

Despite shortcomings in assessment procedures, a UDS will yield positive results for multiple drugs, a feature that is common to seasoned opioid users and serves as an instrumental diagnostic clue in the investigative process. To address the crisis and prevent further spread, numerous Georgia agencies (e.g., drug trafficking and legal authorities) worked with the health care community to expediently identify cases of interest and bring forth public awareness concerning the ongoing perils of counterfeit drug intake. Future investigations might benefit from the implementation of DNA-verified UDS, because those screens are versatile enough to detect the presence of synthetic urine substitutes within the context of opioid use.7,8 Moreover, an expanded panel could be tailored to provide coverage for semisynthetics, including hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and oxymorphone.9

As a well-received painkiller from the opioid family, Percocet derives its analgesic properties from the fast-acting oxycodone; hepatic failure is also possible from Percocet (because of the acetaminophen component) or counterfeit Percocet overdose but is less common unless the Tylenol content approaches 4 grams. By binding to the brain’s opiate receptors, Percocet modulates pain pathways leading to a dulling of pain sensation along with euphoria, which is particularly attractive to drug seekers. Chronic Percocet use corresponds with a myriad of psychological and physical consequences, and the Drug Enforcement Administration recognizes oxycodone as a Schedule II drug.

A chronic Percocet user may try to disrupt the cycle of symptoms by abruptly ceasing use of the offending agent. This can precipitate the development of classical opioid-based withdrawal symptoms, including but not limited to nausea, vomiting, irritability, tachycardia, body aches, and episodes of cold sweats. Physicians have noted that misuse (i.e., deviations from intended prescribed) might include crushing and snorting as well as “doctor-shopping” behaviors for a continuous supply of Percocet.

Treatment recommendations

According to Sarah Wakeman, MD, medical director of the substance use disorders initiative at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, there are apparently two clinical manifestations of Percocet use. The primary consequence is derived from the oxycodone component of Percocet; as an opioid, oxycodone toxicity leads to disrupted breathing and oxygenation, negatively impacting vital organs such as the brain or the heart. Patients experiencing a lack of oxygen will often display cyanosis and may not respond appropriately to stimuli. For individuals suspected of succumbing to overdose, Dr. Wakeman reportedly advised that the clinician or trained professional rub his or her knuckles along the breastbone of the potential user – a drug overdose patient will fail to wake up. On the other hand, a Percocet user may exhibit the symptoms of liver failure depending on the overall level of acetaminophen in the formulation. To prevent relapses, Percocet use disorder is best managed in a professional setting under the direction of trained clinicians; users are provided medications to address ongoing cravings and symptoms associated with the withdrawal process. A detoxification center can tailor the treatment with opioid-based medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone to help patients be weaned off Percocet.

Clinicians may further improve the efficacy of a therapeutic regimen by incorporating a personalized plan with a comprehensive substance UDS panel for monitoring and treatment purposes. This may prove to be beneficial in the event of suspected polysubstance use, as is the case with patients who dabble with Percocet and “molly.” Preparations can also be instituted at the outset of therapy with genetic testing implemented in high-risk patients who exhibit an inclination for opioid use disorder.10 Genetic polymorphisms provide robust clinical assets for evaluating patients most at risk for relapse. For individuals with biological susceptibility, arrangements can be made to incorporate nonopioid treatment alternatives.

References

1. Thomas BB. The death of Lil Peep: How the U.S. prescription drug epidemic is changing hip-hop. The Guardian. 2017 Nov 16.

2. D’Orazio JL and Curtis JA. J Emer Med. 2011 Aug 1;41(2):172-5.

3. Levy L. These are the drugs influencing pop culture now. Vulture. 2018 Feb 6.

4. Kounang N and Bender M. “What is Percocet? Drug facts, side effects, abuse and more.” CNN. 2018 Jul 12.

5. The dangers of Percocet use and overdose. American Addiction Centers. Last updated 2020 Feb 3. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/percocet-treatment/dangers-of-use-and-overdose.

6. Edison L et al. MMWR. 2017 Oct 20;66(41):1119-20.

7. Choudhry Z et al. J Psychiatry. 2015. doi: 10.4172/2378-5756.10000319.

8. Islam F and Choudhry Z. Current Psychiatry. 2018 Dec;17(12):43-4.

9. Jupe N. Ask the Experts: DOT 5-panel drug test regimen. Quest Diagnostics. 2018 Mar 21. https://blog.employersolutions.com/ask-experts-dot-5-panel-drug-test-regimen/.

10. Ahmed S et al. Pharmacogenomics. 2019 Jun 28;20(9):685-703.

Dr. Islam is a medical adviser for the International Maternal and Child Health Foundation, Montreal, and is based in New York. He also is a postdoctoral fellow, psychopharmacologist, and a board-certified medical affairs specialist. Dr. Islam reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Choudhry is the chief scientific officer and head of the department of mental health and clinical research at the IMCHF. He reported no relevant disclosures.

In recent years, Percocet (oxycodone/paracetamol) has experienced a meteoric rise to prominence because of the presence of conspicuous references in pop culture and the ever-evolving hip-hop scene,1 so much so that even propafenone is being mislabeled as the agent.2 It is of utmost importance for clinicians to be made aware of the adverse effects and the treatment protocols associated with Percocet as well as propafenone.

Propafenone is identified as a class 1C antiarrhythmic with adverse effects associated with that particular class of drugs (e.g., generalized tonic-clonic seizures coupled with widened QRS complex), however, Percocet’s toxidrome is the product of the opioid/nonopioid (in the form of oxycodone/acetaminophen) components found within the formulation. Percocet is often recreationally used with MDMA (“molly”) or ecstasy as popularized by the lyrics of “Mask Off” by Future (“Percocets, Molly, Percocets”).3,4

Addressing the challenge of imitation Percocet pills

Differentiating the untoward effects of Percocet and propafenone isn’t too challenging because the agents belong to separate classes – the problem is the use of deceitful labels on propafenone with both medications sporting the “512 imprint” on their respective pills. Initial symptoms of propafenone ingestion may include weakness and dizziness followed by seizures.5As an emergent situation, the patient should be immediately treated with a sodium bicarbonate infusion to effectively reverse the sodium channel blockade associated with the widened QRS.

However, a more likely scenario is that of Percocet counterfeit pills designed to illicitly emulate the properties of officially marketed Percocet. As expected, Percocet overdose management will require that the clinician be familiar with treating general opioid toxicity (in this case, derived from the oxycodone component), in particular respiratory or CNS depression. Symptoms of opioid overdose also include the loss of consciousness with pupillary miosis. Therapy entails the use of naloxone and/or mechanical ventilation for respiratory support. The patient can also exhibit cardiovascular compromise. If further information is elicited during a patient interview, it may reveal a history of drug procurement from the streets.

Epidemiologists from Georgia collaborated with the state’s department of public health’s office of emergency services, forensic experts, and drug enforcement professionals to evaluate almost 40 cases of counterfeit Percocet overdoses during the period spanning the second week of June 2017. Of these cases, a cluster triad was identified consisting of general opioid toxicity symptoms (for example, CNS or respiratory depression with concomitant pupillary constriction, a history of drug procurement, and a history of ingesting only one or two pills with rapid deterioration.6 Unfortunately, the screening process is often hindered by the fact that synthetic opioids such as Percocet are not readily identified on urine drug screens (UDS).

Despite shortcomings in assessment procedures, a UDS will yield positive results for multiple drugs, a feature that is common to seasoned opioid users and serves as an instrumental diagnostic clue in the investigative process. To address the crisis and prevent further spread, numerous Georgia agencies (e.g., drug trafficking and legal authorities) worked with the health care community to expediently identify cases of interest and bring forth public awareness concerning the ongoing perils of counterfeit drug intake. Future investigations might benefit from the implementation of DNA-verified UDS, because those screens are versatile enough to detect the presence of synthetic urine substitutes within the context of opioid use.7,8 Moreover, an expanded panel could be tailored to provide coverage for semisynthetics, including hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and oxymorphone.9

As a well-received painkiller from the opioid family, Percocet derives its analgesic properties from the fast-acting oxycodone; hepatic failure is also possible from Percocet (because of the acetaminophen component) or counterfeit Percocet overdose but is less common unless the Tylenol content approaches 4 grams. By binding to the brain’s opiate receptors, Percocet modulates pain pathways leading to a dulling of pain sensation along with euphoria, which is particularly attractive to drug seekers. Chronic Percocet use corresponds with a myriad of psychological and physical consequences, and the Drug Enforcement Administration recognizes oxycodone as a Schedule II drug.

A chronic Percocet user may try to disrupt the cycle of symptoms by abruptly ceasing use of the offending agent. This can precipitate the development of classical opioid-based withdrawal symptoms, including but not limited to nausea, vomiting, irritability, tachycardia, body aches, and episodes of cold sweats. Physicians have noted that misuse (i.e., deviations from intended prescribed) might include crushing and snorting as well as “doctor-shopping” behaviors for a continuous supply of Percocet.

Treatment recommendations

According to Sarah Wakeman, MD, medical director of the substance use disorders initiative at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, there are apparently two clinical manifestations of Percocet use. The primary consequence is derived from the oxycodone component of Percocet; as an opioid, oxycodone toxicity leads to disrupted breathing and oxygenation, negatively impacting vital organs such as the brain or the heart. Patients experiencing a lack of oxygen will often display cyanosis and may not respond appropriately to stimuli. For individuals suspected of succumbing to overdose, Dr. Wakeman reportedly advised that the clinician or trained professional rub his or her knuckles along the breastbone of the potential user – a drug overdose patient will fail to wake up. On the other hand, a Percocet user may exhibit the symptoms of liver failure depending on the overall level of acetaminophen in the formulation. To prevent relapses, Percocet use disorder is best managed in a professional setting under the direction of trained clinicians; users are provided medications to address ongoing cravings and symptoms associated with the withdrawal process. A detoxification center can tailor the treatment with opioid-based medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone to help patients be weaned off Percocet.

Clinicians may further improve the efficacy of a therapeutic regimen by incorporating a personalized plan with a comprehensive substance UDS panel for monitoring and treatment purposes. This may prove to be beneficial in the event of suspected polysubstance use, as is the case with patients who dabble with Percocet and “molly.” Preparations can also be instituted at the outset of therapy with genetic testing implemented in high-risk patients who exhibit an inclination for opioid use disorder.10 Genetic polymorphisms provide robust clinical assets for evaluating patients most at risk for relapse. For individuals with biological susceptibility, arrangements can be made to incorporate nonopioid treatment alternatives.

References

1. Thomas BB. The death of Lil Peep: How the U.S. prescription drug epidemic is changing hip-hop. The Guardian. 2017 Nov 16.

2. D’Orazio JL and Curtis JA. J Emer Med. 2011 Aug 1;41(2):172-5.

3. Levy L. These are the drugs influencing pop culture now. Vulture. 2018 Feb 6.

4. Kounang N and Bender M. “What is Percocet? Drug facts, side effects, abuse and more.” CNN. 2018 Jul 12.

5. The dangers of Percocet use and overdose. American Addiction Centers. Last updated 2020 Feb 3. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/percocet-treatment/dangers-of-use-and-overdose.

6. Edison L et al. MMWR. 2017 Oct 20;66(41):1119-20.

7. Choudhry Z et al. J Psychiatry. 2015. doi: 10.4172/2378-5756.10000319.

8. Islam F and Choudhry Z. Current Psychiatry. 2018 Dec;17(12):43-4.

9. Jupe N. Ask the Experts: DOT 5-panel drug test regimen. Quest Diagnostics. 2018 Mar 21. https://blog.employersolutions.com/ask-experts-dot-5-panel-drug-test-regimen/.

10. Ahmed S et al. Pharmacogenomics. 2019 Jun 28;20(9):685-703.

Dr. Islam is a medical adviser for the International Maternal and Child Health Foundation, Montreal, and is based in New York. He also is a postdoctoral fellow, psychopharmacologist, and a board-certified medical affairs specialist. Dr. Islam reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Choudhry is the chief scientific officer and head of the department of mental health and clinical research at the IMCHF. He reported no relevant disclosures.

Rapid relief of opioid-induced constipation with MNTX

Subcutaneously administered methylnaltrexone (MNTX) (Relistor), a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist, relieves opioid-induced constipation (OID) in both chronic, noncancer-related illness and cancer-related illness, a new analysis concludes.

“While these are two very different patient groups, the ability to have something to treat OIC in noncancer patients who stay on opioids for whatever reason helps, because [otherwise] these patients are not doing well,” said lead author Eric Shah, MD, motility director for the Dartmouth program at Dartmouth Hitchcock Health, Lebanon, N.H.

Importantly, peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists such as MNTX do not affect overall pain control to any significant extent, which is “reassuring,” he said in an interview.

These drugs decrease the constipating effects of opioids without reversing CNS-mediated opioid effects, he explained.

“Methylnaltrexone has already been approved for the treatment of OIC in adults with chronic noncancer pain as well as for OIC in adults with advanced illness who are receiving palliative care, which is often the case in patients with cancer-related pain,” he noted.

Dr. Shah discussed the new analysis during PAINWeek 2020, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 19th Annual Pain Medicine Meeting.

The analysis was based on a review of data collected in two previously reported randomized, placebo-controlled studies (study 302 and 4000), which were used to gain approval.

The new analysis shows that “the drug works up front, and the effect is able to be maintained. I think the studies are clinically relevant in that patients are able to have a bowel movement quickly after you give them an injectable formulation when they are vomiting or otherwise can’t tolerate a pill and they are feeling miserable,” Dr. Shah commented. Many patients with OIC are constipated for reasons other than from opioid use. They often have other side effects from opioids, including bloating, nausea, and vomiting.

“When patients go to the emergency room, it’s not just that they are not able to have a bowel movement; they are often also vomiting, so it’s important to have agents that can be given in a manner that avoids the need for oral medication,” Dr. Shah said. MNTX is the only peripherally acting opioid antagonist available in a subcutaneous formulation.

Moreover, if patients are able to control these symptoms at home with an injectable formulation, they may not need to go to the ED for treatment of their gastrointestinal distress, he added.

Viable product

In a comment, Darren Brenner, MD, associate professor of medicine and surgery, Northwestern University, Chicago, who has worked with this subcutaneous formulation, said it is “definitely a viable product.

“The data presented here were in patients with advanced illness receiving palliative care when other laxatives have failed, and the difference and the potential benefit for MNTX is that it is the only peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist that is approved for advanced cancer,” he added. The other products that are currently approved, naloxegol (Movantik) and naldemedine (Symproic), are both indicated for chronic, noncancer pain.

The other potential benefit of subcutaneous MNTX is that it can work very rapidly for the patients who respond to it. “One of the things investigators did not mention in these two trials but which has been shown in previous studies is that almost half of patients who respond to this drug respond within the first 30 minutes of receiving the injection,” Dr. Brenner said in an interview.

This can be very beneficial in an emergency setting, because it may avoid having patients admitted to hospital. They can be discharged and sent home with enough drug to use on demand, Dr. Brenner suggested.

New analysis of data from studies 302 and 4000

Both studies were carried out in adults with advanced illness and OIC whose conditions were refractory to laxative use. Both of the studies were placebo controlled.

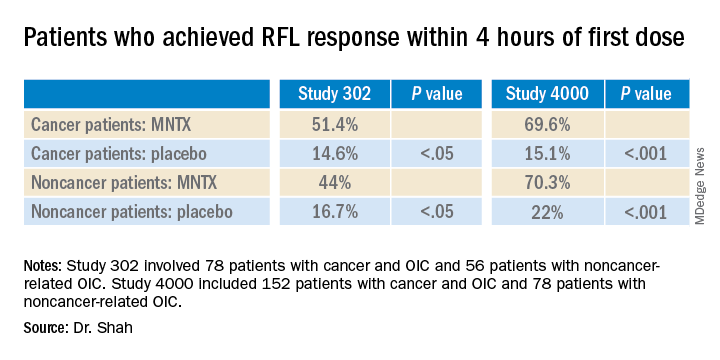

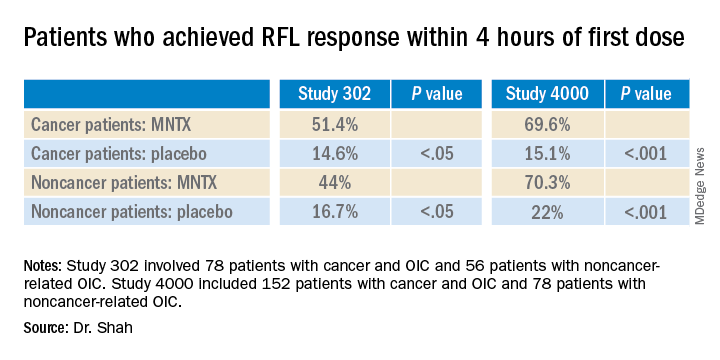

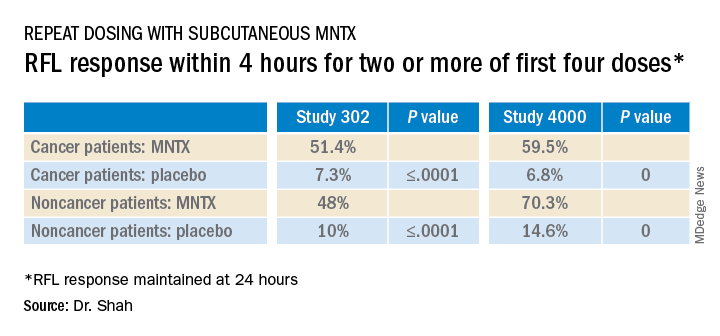

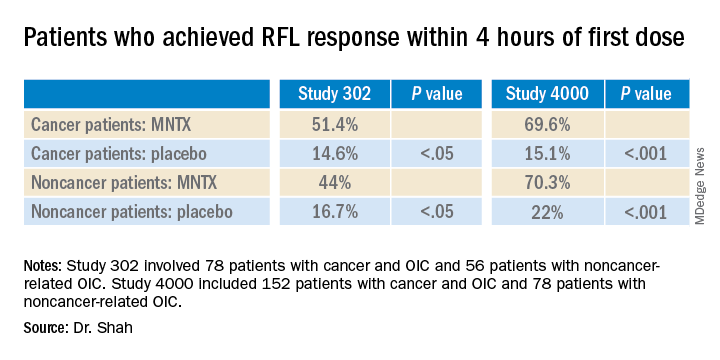

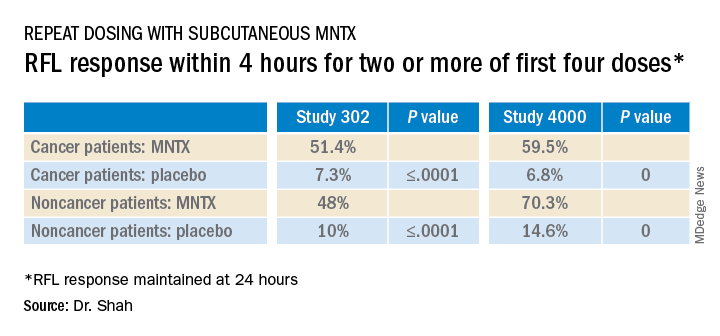

Study 302 involved 78 patients with cancer and 56 patients with noncancer-related OIC. MNTX was given at a dose of 0.15 mg/kg subcutaneously every other day for 2 weeks.

Study 4000 included 152 patients with cancer and OIC and 78 patients with noncancer-related OIC. In this study, the dose of MNTX was based on body weight. Seven or fewer doses of either 8 mg or 12 mg were given subcutaneously for 2 weeks.

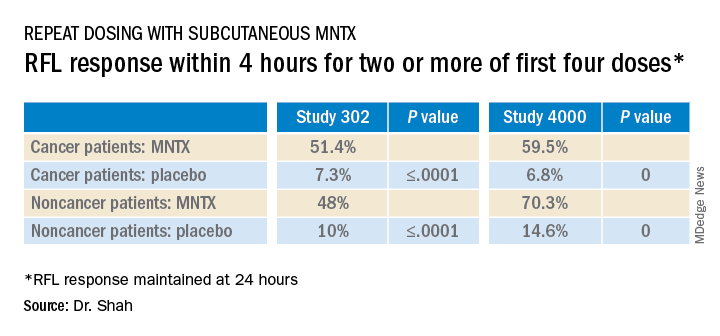

The main endpoints of both studies was the proportion of patients who achieved a rescue-free laxation (RFL) response within 4 hours after the first dose and the proportion of patients with an RFL response within 4 hours for two or more of the first four doses within 24 hours.

Dr. Shah explained that RFL is a meaningful clinical endpoint. Patients could achieve a bowel movement with the two prespecified time endpoints in both studies.

Not all patients were hospitalized for OIC, Dr. Shah noted. Entry criteria were strict and included having fewer than three bowel movements during the previous week and no clinically significant laxation (defecation) within 48 hours of receiving the first dose of study drug.

“In both studies, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with MNTX versus placebo achieved an RFL within 4 hours after the first dose among both cancer and noncancer patients,” the investigators reported.

Results were relatively comparable between cancer and noncancer patients who were treated for OIC in study 4000, the investigators noted.

Both studies were sponsored by Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Shah has received travel fees from Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Brenner has served as a consultant for Salix Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, and Purdue Pharma. AstraZeneca developed naloxegol.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Subcutaneously administered methylnaltrexone (MNTX) (Relistor), a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist, relieves opioid-induced constipation (OID) in both chronic, noncancer-related illness and cancer-related illness, a new analysis concludes.

“While these are two very different patient groups, the ability to have something to treat OIC in noncancer patients who stay on opioids for whatever reason helps, because [otherwise] these patients are not doing well,” said lead author Eric Shah, MD, motility director for the Dartmouth program at Dartmouth Hitchcock Health, Lebanon, N.H.

Importantly, peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists such as MNTX do not affect overall pain control to any significant extent, which is “reassuring,” he said in an interview.

These drugs decrease the constipating effects of opioids without reversing CNS-mediated opioid effects, he explained.

“Methylnaltrexone has already been approved for the treatment of OIC in adults with chronic noncancer pain as well as for OIC in adults with advanced illness who are receiving palliative care, which is often the case in patients with cancer-related pain,” he noted.

Dr. Shah discussed the new analysis during PAINWeek 2020, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 19th Annual Pain Medicine Meeting.

The analysis was based on a review of data collected in two previously reported randomized, placebo-controlled studies (study 302 and 4000), which were used to gain approval.

The new analysis shows that “the drug works up front, and the effect is able to be maintained. I think the studies are clinically relevant in that patients are able to have a bowel movement quickly after you give them an injectable formulation when they are vomiting or otherwise can’t tolerate a pill and they are feeling miserable,” Dr. Shah commented. Many patients with OIC are constipated for reasons other than from opioid use. They often have other side effects from opioids, including bloating, nausea, and vomiting.

“When patients go to the emergency room, it’s not just that they are not able to have a bowel movement; they are often also vomiting, so it’s important to have agents that can be given in a manner that avoids the need for oral medication,” Dr. Shah said. MNTX is the only peripherally acting opioid antagonist available in a subcutaneous formulation.

Moreover, if patients are able to control these symptoms at home with an injectable formulation, they may not need to go to the ED for treatment of their gastrointestinal distress, he added.

Viable product

In a comment, Darren Brenner, MD, associate professor of medicine and surgery, Northwestern University, Chicago, who has worked with this subcutaneous formulation, said it is “definitely a viable product.

“The data presented here were in patients with advanced illness receiving palliative care when other laxatives have failed, and the difference and the potential benefit for MNTX is that it is the only peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist that is approved for advanced cancer,” he added. The other products that are currently approved, naloxegol (Movantik) and naldemedine (Symproic), are both indicated for chronic, noncancer pain.

The other potential benefit of subcutaneous MNTX is that it can work very rapidly for the patients who respond to it. “One of the things investigators did not mention in these two trials but which has been shown in previous studies is that almost half of patients who respond to this drug respond within the first 30 minutes of receiving the injection,” Dr. Brenner said in an interview.

This can be very beneficial in an emergency setting, because it may avoid having patients admitted to hospital. They can be discharged and sent home with enough drug to use on demand, Dr. Brenner suggested.

New analysis of data from studies 302 and 4000

Both studies were carried out in adults with advanced illness and OIC whose conditions were refractory to laxative use. Both of the studies were placebo controlled.

Study 302 involved 78 patients with cancer and 56 patients with noncancer-related OIC. MNTX was given at a dose of 0.15 mg/kg subcutaneously every other day for 2 weeks.

Study 4000 included 152 patients with cancer and OIC and 78 patients with noncancer-related OIC. In this study, the dose of MNTX was based on body weight. Seven or fewer doses of either 8 mg or 12 mg were given subcutaneously for 2 weeks.

The main endpoints of both studies was the proportion of patients who achieved a rescue-free laxation (RFL) response within 4 hours after the first dose and the proportion of patients with an RFL response within 4 hours for two or more of the first four doses within 24 hours.

Dr. Shah explained that RFL is a meaningful clinical endpoint. Patients could achieve a bowel movement with the two prespecified time endpoints in both studies.

Not all patients were hospitalized for OIC, Dr. Shah noted. Entry criteria were strict and included having fewer than three bowel movements during the previous week and no clinically significant laxation (defecation) within 48 hours of receiving the first dose of study drug.

“In both studies, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with MNTX versus placebo achieved an RFL within 4 hours after the first dose among both cancer and noncancer patients,” the investigators reported.

Results were relatively comparable between cancer and noncancer patients who were treated for OIC in study 4000, the investigators noted.

Both studies were sponsored by Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Shah has received travel fees from Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Brenner has served as a consultant for Salix Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, and Purdue Pharma. AstraZeneca developed naloxegol.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Subcutaneously administered methylnaltrexone (MNTX) (Relistor), a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist, relieves opioid-induced constipation (OID) in both chronic, noncancer-related illness and cancer-related illness, a new analysis concludes.

“While these are two very different patient groups, the ability to have something to treat OIC in noncancer patients who stay on opioids for whatever reason helps, because [otherwise] these patients are not doing well,” said lead author Eric Shah, MD, motility director for the Dartmouth program at Dartmouth Hitchcock Health, Lebanon, N.H.

Importantly, peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists such as MNTX do not affect overall pain control to any significant extent, which is “reassuring,” he said in an interview.

These drugs decrease the constipating effects of opioids without reversing CNS-mediated opioid effects, he explained.

“Methylnaltrexone has already been approved for the treatment of OIC in adults with chronic noncancer pain as well as for OIC in adults with advanced illness who are receiving palliative care, which is often the case in patients with cancer-related pain,” he noted.

Dr. Shah discussed the new analysis during PAINWeek 2020, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 19th Annual Pain Medicine Meeting.

The analysis was based on a review of data collected in two previously reported randomized, placebo-controlled studies (study 302 and 4000), which were used to gain approval.

The new analysis shows that “the drug works up front, and the effect is able to be maintained. I think the studies are clinically relevant in that patients are able to have a bowel movement quickly after you give them an injectable formulation when they are vomiting or otherwise can’t tolerate a pill and they are feeling miserable,” Dr. Shah commented. Many patients with OIC are constipated for reasons other than from opioid use. They often have other side effects from opioids, including bloating, nausea, and vomiting.

“When patients go to the emergency room, it’s not just that they are not able to have a bowel movement; they are often also vomiting, so it’s important to have agents that can be given in a manner that avoids the need for oral medication,” Dr. Shah said. MNTX is the only peripherally acting opioid antagonist available in a subcutaneous formulation.

Moreover, if patients are able to control these symptoms at home with an injectable formulation, they may not need to go to the ED for treatment of their gastrointestinal distress, he added.

Viable product

In a comment, Darren Brenner, MD, associate professor of medicine and surgery, Northwestern University, Chicago, who has worked with this subcutaneous formulation, said it is “definitely a viable product.

“The data presented here were in patients with advanced illness receiving palliative care when other laxatives have failed, and the difference and the potential benefit for MNTX is that it is the only peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist that is approved for advanced cancer,” he added. The other products that are currently approved, naloxegol (Movantik) and naldemedine (Symproic), are both indicated for chronic, noncancer pain.

The other potential benefit of subcutaneous MNTX is that it can work very rapidly for the patients who respond to it. “One of the things investigators did not mention in these two trials but which has been shown in previous studies is that almost half of patients who respond to this drug respond within the first 30 minutes of receiving the injection,” Dr. Brenner said in an interview.

This can be very beneficial in an emergency setting, because it may avoid having patients admitted to hospital. They can be discharged and sent home with enough drug to use on demand, Dr. Brenner suggested.

New analysis of data from studies 302 and 4000

Both studies were carried out in adults with advanced illness and OIC whose conditions were refractory to laxative use. Both of the studies were placebo controlled.

Study 302 involved 78 patients with cancer and 56 patients with noncancer-related OIC. MNTX was given at a dose of 0.15 mg/kg subcutaneously every other day for 2 weeks.

Study 4000 included 152 patients with cancer and OIC and 78 patients with noncancer-related OIC. In this study, the dose of MNTX was based on body weight. Seven or fewer doses of either 8 mg or 12 mg were given subcutaneously for 2 weeks.

The main endpoints of both studies was the proportion of patients who achieved a rescue-free laxation (RFL) response within 4 hours after the first dose and the proportion of patients with an RFL response within 4 hours for two or more of the first four doses within 24 hours.

Dr. Shah explained that RFL is a meaningful clinical endpoint. Patients could achieve a bowel movement with the two prespecified time endpoints in both studies.

Not all patients were hospitalized for OIC, Dr. Shah noted. Entry criteria were strict and included having fewer than three bowel movements during the previous week and no clinically significant laxation (defecation) within 48 hours of receiving the first dose of study drug.

“In both studies, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with MNTX versus placebo achieved an RFL within 4 hours after the first dose among both cancer and noncancer patients,” the investigators reported.

Results were relatively comparable between cancer and noncancer patients who were treated for OIC in study 4000, the investigators noted.

Both studies were sponsored by Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Shah has received travel fees from Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Brenner has served as a consultant for Salix Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, and Purdue Pharma. AstraZeneca developed naloxegol.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How mental health care would look under a Trump vs. Biden administration

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most pressing public health challenges the United States has ever faced, and the resulting financial ruin and social isolation are creating a mental health pandemic that will continue well after COVID-19 lockdowns end. To understand which presidential candidate would best lead the mental health recovery, we identified three of the most critical issues in mental health and compared the plans of the two candidates.

Fighting the opioid epidemic

Over the last several years, the opioid epidemic has devastated American families and communities. Prior to the pandemic, drug overdoses were the leading cause of death for American adults under 50 years of age. The effects of COVID-19–enabled overdose deaths to rise even higher. Multiple elements of the pandemic – isolation, unemployment, and increased anxiety and depression – make those struggling with substance use even more vulnerable, and immediate and comprehensive action is needed to address this national tragedy.

Donald J. Trump: President Trump has been vocal and active in addressing this problem since he took office. One of the Trump administration’s successes is launching the Opioid and Drug Abuse Commission and rolling out a five-point strategy built around improving services, data, research, overdose-reversing drugs, and pain management. Last year, the Trump administration funded $10 billion over 5 years to combat both the opioid epidemic and mental health issues by building upon the 21st Century CURES Act. However, in this same budget, the administration proposed cutting funding by $600 million for SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which is the top government agency for addressing and providing care for substance use.

President Trump also created an assistant secretary for mental health and substance use position in the Department of Health & Human Services, and appointed Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist with a strong track record on fighting opioid abuse in Rhode Island, to the post.

Joe Biden: Former Vice President Biden emphasizes that substance use is “a disease of the brain,” refuting the long-held misconception that addiction is an issue of willpower. This stigmatization is very personal given that his own son Hunter reportedly suffered through mental health and substance use issues since his teenage years. However, Biden also had a major role in pushing forward the federal “war on drugs,” including his role in crafting the “Len Bias law.”

Mr. Biden has since released a multifaceted plan for reducing substance use, aiming to make prevention and treatment services more available through a $125 billion federal investment. There are also measures to hold pharmaceutical companies accountable for triggering the crisis, stop the flow of fentanyl to the United States, and restrict incentive payments from manufacturers to doctors so as to limit the dosing and usage of powerful opioids.

Accessing health care

One of the main dividing lines in this election has been the battle to either gut or build upon the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This will have deep ramifications on people’s access to health mental health services. Since COVID-19 started, more than 50% of Americans have reported worsening mental health. This makes it crucial that each candidate’s mental health plan is judged by how they would expand access to insurance, address unenforced parity laws, and protect those who have a mental health disorder as a preexisting condition.

Mr. Trump: Following a failed Senate vote to repeal this law, the Trump administration took a piecemeal approach to dismantling the ACA that included removing the individual mandate, enabling states to introduce Medicaid work requirements, and reducing cost-sharing subsidies to insurers.

If a re-elected Trump administration pursued a complete repeal of the ACA law, many individuals with previous access to mental health and substance abuse treatment via Medicaid expansion may lose access altogether. In addition, key mechanisms aimed at making sure that mental health services are covered by private health plans may be lost, which could undermine policies to address opioids and suicide. On the other hand, the Trump administration’s move during the pandemic to expand telemedicine services has also expanded access to mental health services.

Mr. Biden: Mr. Biden’s plan would build upon the ACA by working to achieve parity between the treatment of mental health and physical health. The ACA itself strengthened the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (federal parity law), which Mr. Biden championed as vice president, by mandating that all private insurance cover mental health and substance abuse treatment. This act still exempts some health plans, such as larger employers; and many insurers have used loopholes in the policy to illegally deny what could be life-saving coverage.

It follows that those who can afford Mr. Biden’s proposed public option Medicare buy-in would receive more comprehensive mental health benefits. He also says he would invest in school and college mental health professionals, an important opportunity for early intervention given 75% of lifetime mental illness starts by age 24 years. While Mr. Biden has not stated a specific plan for addressing minority groups, whose mental health has been disproportionately affected by COVID-19, he has acknowledged that this unmet need should be targeted.

Addressing suicide

More than 3,000 Americans attempt suicide every day. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for America’s youth and one of the top 10 leading causes of death across the population. Numerous strategies are necessary to address suicide, but one of the most decisive is gun control. Gun violence is inextricably tied to suicide: States where gun prevalence is higher see about four times the number of suicides because of guns, whereas nonfirearm suicide rates are the same as those seen elsewhere. In 2017, of the nearly 40,000 people who died of gun violence, 60% were attributable to suicides. Since the pandemic started, there have been increases in reported suicidal thoughts and a nearly 1,000% increase in use of the national crisis hotline. This is especially concerning given the uptick during the pandemic of gun purchases; as of September, more guns have been purchased this year than any year before.

Mr. Trump: Prior to coronavirus, the Trump administration was unwilling to enact gun control legislation. In early 2017, Mr. Trump removed an Obama-era bill that would have expanded the background check database. It would have added those deemed legally unfit to handle their own funds and those who received Social Security funds for mental health reasons. During the lockdown, the administration made an advisory ruling declaring gun shops as essential businesses that states should keep open.

Mr. Biden: The former vice president has a history of supporting gun control measures in his time as a senator and vice president. In the Senate, Mr. Biden supported both the Brady handgun bill in 1993 and a ban on assault weapons in 1994. As vice president, he was tasked by President Obama to push for a renewed assault weapons ban and a background check bill (Manchin-Toomey bill).

During his 2020 presidential campaign, Mr. Biden has suggested creating universal background checks and reinstating bans on assault rifle sales. He has said that he is also open to having a federal buyback program for assault rifles from gun owners.

Why this matters

The winner of the 2020 election will lead an electorate that is reeling from the health, economic, and social consequences COVID-19. The next administration needs to act swiftly to address the mental health pandemic and have a keen awareness of what is ahead. As Americans make their voting decision, consider who has the best plans not only to contain the virus but also the mental health crises that are ravaging our nation.

Dr. Vasan is a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University, where she is founder and executive director of Brainstorm: The Stanford Lab for Mental Health Innovation. She also serves as chief medical officer of Real, and chair of the American Psychiatric Association Committee on Innovation. Dr. Vasan has no conflicts of interest. Mr. Agbafe is a fellow at Stanford Brainstorm and a first-year medical student at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts of interest. Ms. Li is a policy intern at Stanford Brainstorm and an undergraduate student in the department of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. She has no conflicts of interest.

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most pressing public health challenges the United States has ever faced, and the resulting financial ruin and social isolation are creating a mental health pandemic that will continue well after COVID-19 lockdowns end. To understand which presidential candidate would best lead the mental health recovery, we identified three of the most critical issues in mental health and compared the plans of the two candidates.

Fighting the opioid epidemic

Over the last several years, the opioid epidemic has devastated American families and communities. Prior to the pandemic, drug overdoses were the leading cause of death for American adults under 50 years of age. The effects of COVID-19–enabled overdose deaths to rise even higher. Multiple elements of the pandemic – isolation, unemployment, and increased anxiety and depression – make those struggling with substance use even more vulnerable, and immediate and comprehensive action is needed to address this national tragedy.

Donald J. Trump: President Trump has been vocal and active in addressing this problem since he took office. One of the Trump administration’s successes is launching the Opioid and Drug Abuse Commission and rolling out a five-point strategy built around improving services, data, research, overdose-reversing drugs, and pain management. Last year, the Trump administration funded $10 billion over 5 years to combat both the opioid epidemic and mental health issues by building upon the 21st Century CURES Act. However, in this same budget, the administration proposed cutting funding by $600 million for SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which is the top government agency for addressing and providing care for substance use.

President Trump also created an assistant secretary for mental health and substance use position in the Department of Health & Human Services, and appointed Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist with a strong track record on fighting opioid abuse in Rhode Island, to the post.

Joe Biden: Former Vice President Biden emphasizes that substance use is “a disease of the brain,” refuting the long-held misconception that addiction is an issue of willpower. This stigmatization is very personal given that his own son Hunter reportedly suffered through mental health and substance use issues since his teenage years. However, Biden also had a major role in pushing forward the federal “war on drugs,” including his role in crafting the “Len Bias law.”

Mr. Biden has since released a multifaceted plan for reducing substance use, aiming to make prevention and treatment services more available through a $125 billion federal investment. There are also measures to hold pharmaceutical companies accountable for triggering the crisis, stop the flow of fentanyl to the United States, and restrict incentive payments from manufacturers to doctors so as to limit the dosing and usage of powerful opioids.

Accessing health care

One of the main dividing lines in this election has been the battle to either gut or build upon the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This will have deep ramifications on people’s access to health mental health services. Since COVID-19 started, more than 50% of Americans have reported worsening mental health. This makes it crucial that each candidate’s mental health plan is judged by how they would expand access to insurance, address unenforced parity laws, and protect those who have a mental health disorder as a preexisting condition.

Mr. Trump: Following a failed Senate vote to repeal this law, the Trump administration took a piecemeal approach to dismantling the ACA that included removing the individual mandate, enabling states to introduce Medicaid work requirements, and reducing cost-sharing subsidies to insurers.

If a re-elected Trump administration pursued a complete repeal of the ACA law, many individuals with previous access to mental health and substance abuse treatment via Medicaid expansion may lose access altogether. In addition, key mechanisms aimed at making sure that mental health services are covered by private health plans may be lost, which could undermine policies to address opioids and suicide. On the other hand, the Trump administration’s move during the pandemic to expand telemedicine services has also expanded access to mental health services.

Mr. Biden: Mr. Biden’s plan would build upon the ACA by working to achieve parity between the treatment of mental health and physical health. The ACA itself strengthened the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (federal parity law), which Mr. Biden championed as vice president, by mandating that all private insurance cover mental health and substance abuse treatment. This act still exempts some health plans, such as larger employers; and many insurers have used loopholes in the policy to illegally deny what could be life-saving coverage.

It follows that those who can afford Mr. Biden’s proposed public option Medicare buy-in would receive more comprehensive mental health benefits. He also says he would invest in school and college mental health professionals, an important opportunity for early intervention given 75% of lifetime mental illness starts by age 24 years. While Mr. Biden has not stated a specific plan for addressing minority groups, whose mental health has been disproportionately affected by COVID-19, he has acknowledged that this unmet need should be targeted.

Addressing suicide

More than 3,000 Americans attempt suicide every day. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for America’s youth and one of the top 10 leading causes of death across the population. Numerous strategies are necessary to address suicide, but one of the most decisive is gun control. Gun violence is inextricably tied to suicide: States where gun prevalence is higher see about four times the number of suicides because of guns, whereas nonfirearm suicide rates are the same as those seen elsewhere. In 2017, of the nearly 40,000 people who died of gun violence, 60% were attributable to suicides. Since the pandemic started, there have been increases in reported suicidal thoughts and a nearly 1,000% increase in use of the national crisis hotline. This is especially concerning given the uptick during the pandemic of gun purchases; as of September, more guns have been purchased this year than any year before.

Mr. Trump: Prior to coronavirus, the Trump administration was unwilling to enact gun control legislation. In early 2017, Mr. Trump removed an Obama-era bill that would have expanded the background check database. It would have added those deemed legally unfit to handle their own funds and those who received Social Security funds for mental health reasons. During the lockdown, the administration made an advisory ruling declaring gun shops as essential businesses that states should keep open.

Mr. Biden: The former vice president has a history of supporting gun control measures in his time as a senator and vice president. In the Senate, Mr. Biden supported both the Brady handgun bill in 1993 and a ban on assault weapons in 1994. As vice president, he was tasked by President Obama to push for a renewed assault weapons ban and a background check bill (Manchin-Toomey bill).

During his 2020 presidential campaign, Mr. Biden has suggested creating universal background checks and reinstating bans on assault rifle sales. He has said that he is also open to having a federal buyback program for assault rifles from gun owners.

Why this matters

The winner of the 2020 election will lead an electorate that is reeling from the health, economic, and social consequences COVID-19. The next administration needs to act swiftly to address the mental health pandemic and have a keen awareness of what is ahead. As Americans make their voting decision, consider who has the best plans not only to contain the virus but also the mental health crises that are ravaging our nation.

Dr. Vasan is a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University, where she is founder and executive director of Brainstorm: The Stanford Lab for Mental Health Innovation. She also serves as chief medical officer of Real, and chair of the American Psychiatric Association Committee on Innovation. Dr. Vasan has no conflicts of interest. Mr. Agbafe is a fellow at Stanford Brainstorm and a first-year medical student at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts of interest. Ms. Li is a policy intern at Stanford Brainstorm and an undergraduate student in the department of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. She has no conflicts of interest.

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most pressing public health challenges the United States has ever faced, and the resulting financial ruin and social isolation are creating a mental health pandemic that will continue well after COVID-19 lockdowns end. To understand which presidential candidate would best lead the mental health recovery, we identified three of the most critical issues in mental health and compared the plans of the two candidates.

Fighting the opioid epidemic

Over the last several years, the opioid epidemic has devastated American families and communities. Prior to the pandemic, drug overdoses were the leading cause of death for American adults under 50 years of age. The effects of COVID-19–enabled overdose deaths to rise even higher. Multiple elements of the pandemic – isolation, unemployment, and increased anxiety and depression – make those struggling with substance use even more vulnerable, and immediate and comprehensive action is needed to address this national tragedy.

Donald J. Trump: President Trump has been vocal and active in addressing this problem since he took office. One of the Trump administration’s successes is launching the Opioid and Drug Abuse Commission and rolling out a five-point strategy built around improving services, data, research, overdose-reversing drugs, and pain management. Last year, the Trump administration funded $10 billion over 5 years to combat both the opioid epidemic and mental health issues by building upon the 21st Century CURES Act. However, in this same budget, the administration proposed cutting funding by $600 million for SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which is the top government agency for addressing and providing care for substance use.

President Trump also created an assistant secretary for mental health and substance use position in the Department of Health & Human Services, and appointed Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist with a strong track record on fighting opioid abuse in Rhode Island, to the post.

Joe Biden: Former Vice President Biden emphasizes that substance use is “a disease of the brain,” refuting the long-held misconception that addiction is an issue of willpower. This stigmatization is very personal given that his own son Hunter reportedly suffered through mental health and substance use issues since his teenage years. However, Biden also had a major role in pushing forward the federal “war on drugs,” including his role in crafting the “Len Bias law.”

Mr. Biden has since released a multifaceted plan for reducing substance use, aiming to make prevention and treatment services more available through a $125 billion federal investment. There are also measures to hold pharmaceutical companies accountable for triggering the crisis, stop the flow of fentanyl to the United States, and restrict incentive payments from manufacturers to doctors so as to limit the dosing and usage of powerful opioids.

Accessing health care

One of the main dividing lines in this election has been the battle to either gut or build upon the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This will have deep ramifications on people’s access to health mental health services. Since COVID-19 started, more than 50% of Americans have reported worsening mental health. This makes it crucial that each candidate’s mental health plan is judged by how they would expand access to insurance, address unenforced parity laws, and protect those who have a mental health disorder as a preexisting condition.

Mr. Trump: Following a failed Senate vote to repeal this law, the Trump administration took a piecemeal approach to dismantling the ACA that included removing the individual mandate, enabling states to introduce Medicaid work requirements, and reducing cost-sharing subsidies to insurers.

If a re-elected Trump administration pursued a complete repeal of the ACA law, many individuals with previous access to mental health and substance abuse treatment via Medicaid expansion may lose access altogether. In addition, key mechanisms aimed at making sure that mental health services are covered by private health plans may be lost, which could undermine policies to address opioids and suicide. On the other hand, the Trump administration’s move during the pandemic to expand telemedicine services has also expanded access to mental health services.

Mr. Biden: Mr. Biden’s plan would build upon the ACA by working to achieve parity between the treatment of mental health and physical health. The ACA itself strengthened the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (federal parity law), which Mr. Biden championed as vice president, by mandating that all private insurance cover mental health and substance abuse treatment. This act still exempts some health plans, such as larger employers; and many insurers have used loopholes in the policy to illegally deny what could be life-saving coverage.

It follows that those who can afford Mr. Biden’s proposed public option Medicare buy-in would receive more comprehensive mental health benefits. He also says he would invest in school and college mental health professionals, an important opportunity for early intervention given 75% of lifetime mental illness starts by age 24 years. While Mr. Biden has not stated a specific plan for addressing minority groups, whose mental health has been disproportionately affected by COVID-19, he has acknowledged that this unmet need should be targeted.

Addressing suicide

More than 3,000 Americans attempt suicide every day. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for America’s youth and one of the top 10 leading causes of death across the population. Numerous strategies are necessary to address suicide, but one of the most decisive is gun control. Gun violence is inextricably tied to suicide: States where gun prevalence is higher see about four times the number of suicides because of guns, whereas nonfirearm suicide rates are the same as those seen elsewhere. In 2017, of the nearly 40,000 people who died of gun violence, 60% were attributable to suicides. Since the pandemic started, there have been increases in reported suicidal thoughts and a nearly 1,000% increase in use of the national crisis hotline. This is especially concerning given the uptick during the pandemic of gun purchases; as of September, more guns have been purchased this year than any year before.

Mr. Trump: Prior to coronavirus, the Trump administration was unwilling to enact gun control legislation. In early 2017, Mr. Trump removed an Obama-era bill that would have expanded the background check database. It would have added those deemed legally unfit to handle their own funds and those who received Social Security funds for mental health reasons. During the lockdown, the administration made an advisory ruling declaring gun shops as essential businesses that states should keep open.

Mr. Biden: The former vice president has a history of supporting gun control measures in his time as a senator and vice president. In the Senate, Mr. Biden supported both the Brady handgun bill in 1993 and a ban on assault weapons in 1994. As vice president, he was tasked by President Obama to push for a renewed assault weapons ban and a background check bill (Manchin-Toomey bill).

During his 2020 presidential campaign, Mr. Biden has suggested creating universal background checks and reinstating bans on assault rifle sales. He has said that he is also open to having a federal buyback program for assault rifles from gun owners.

Why this matters

The winner of the 2020 election will lead an electorate that is reeling from the health, economic, and social consequences COVID-19. The next administration needs to act swiftly to address the mental health pandemic and have a keen awareness of what is ahead. As Americans make their voting decision, consider who has the best plans not only to contain the virus but also the mental health crises that are ravaging our nation.

Dr. Vasan is a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University, where she is founder and executive director of Brainstorm: The Stanford Lab for Mental Health Innovation. She also serves as chief medical officer of Real, and chair of the American Psychiatric Association Committee on Innovation. Dr. Vasan has no conflicts of interest. Mr. Agbafe is a fellow at Stanford Brainstorm and a first-year medical student at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts of interest. Ms. Li is a policy intern at Stanford Brainstorm and an undergraduate student in the department of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. She has no conflicts of interest.

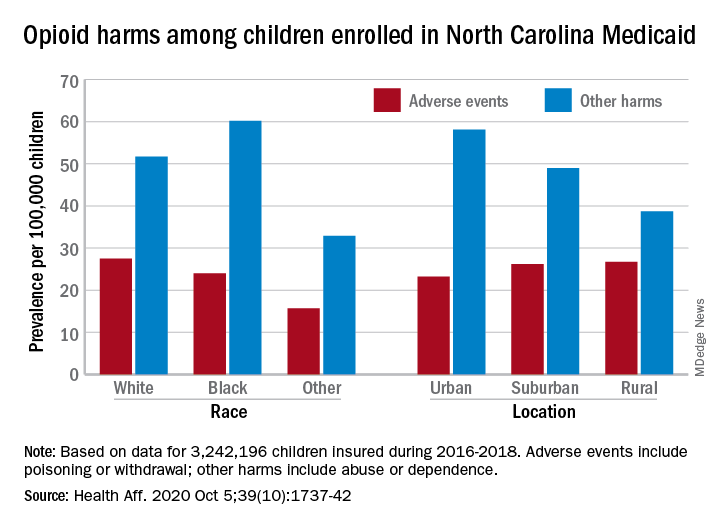

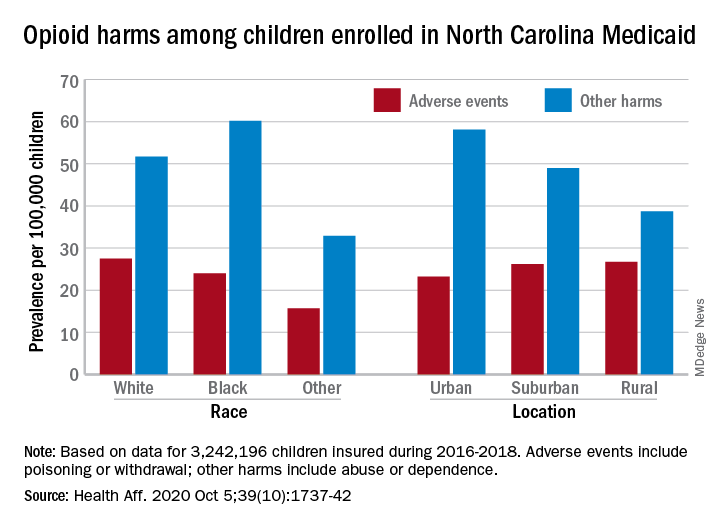

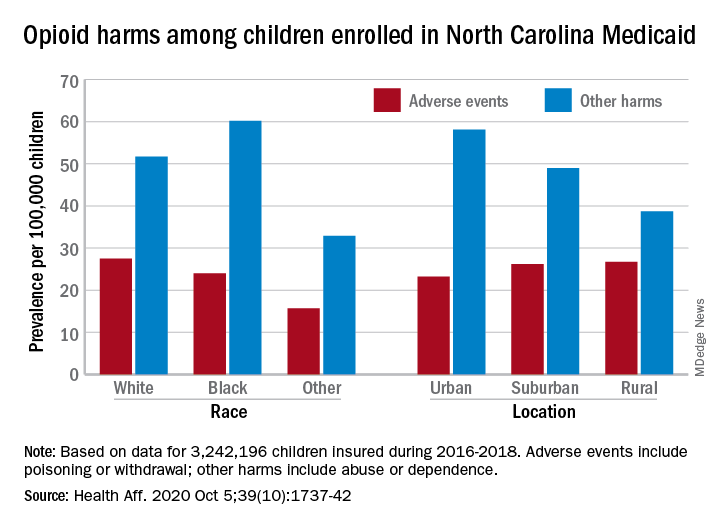

Children’s opioid harms vary by race, location

or dependence, compared with their White or rural/suburban counterparts, according to a study of 3.2 million Medicaid-enrolled children in North Carolina.

Analysis of the almost 138,000 prescription fills also showed that Black and urban children in North Carolina were less likely to fill a opioid prescription, suggesting a need “for future studies to explore racial and geographic opioid-related inequities in children,” Kelby W. Brown, MA, and associates at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said Oct. 5 in Health Affairs.

In 2016-2018, the prevalence of opioid-related adverse events, such as poisoning or withdrawal, was 24.0 per 100,000 children among Blacks aged 1-17 years, compared with 27.5 per 100,000 for whites. For other opioid-related harms such as abuse or dependence, the order was reversed: 60.2 for Blacks and 51.7 for Whites, the investigators reported. Children of all other races were lowest in both measures.

Geography also appears to play a part. The children in urban areas had the lowest rate of adverse events – 23.2 per 100,000 vs. 26.2 (suburban) and 26.7 (rural) – and the highest rate of other opioid-related harms – 58.1 vs. 49.0 (suburban) and 38.7 (rural), the Medicaid claims data showed.

Analysis of prescription fills revealed that black children aged 1-17 years had a significantly lower rate (2.7%) than Whites (3.1%) or those of other races (3.0%) and that urban children were significantly less likely to fill a prescription (2.7%) for opioids than the other two groups (suburban, 3.1%; rural, 3.4%), Mr. Brown and associates said.

The prescription data also showed that 48.4% of children aged 6-17 years who had an adverse event had filled a prescription for an opioid in the previous 6 months, compared with just 9.4% of those with other opioid-related harms. The median length of time since the last fill? Three days for children with an adverse event and 67 days for those with other harms, they said.

And those prescriptions, it turns out, were not coming just from the physicians of North Carolina. Physicians, with 35.5% of the prescription load, were the main source, but 33.3% of opioid fills in 2016-2018 came from dentists, and another 17.7% were written by advanced practice providers. Among physicians, the leading opioid-prescribing specialists were surgeons, with 17.3% of the total, the investigators reported.

“The distinct and separate groups of clinicians who prescribe opioids to children suggest the need for pediatric opioid prescribing guidelines, particularly for postprocedural pain,” Mr. Brown and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Brown KW et al. Health Aff. 2020;39(10):1737-42.

or dependence, compared with their White or rural/suburban counterparts, according to a study of 3.2 million Medicaid-enrolled children in North Carolina.

Analysis of the almost 138,000 prescription fills also showed that Black and urban children in North Carolina were less likely to fill a opioid prescription, suggesting a need “for future studies to explore racial and geographic opioid-related inequities in children,” Kelby W. Brown, MA, and associates at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said Oct. 5 in Health Affairs.

In 2016-2018, the prevalence of opioid-related adverse events, such as poisoning or withdrawal, was 24.0 per 100,000 children among Blacks aged 1-17 years, compared with 27.5 per 100,000 for whites. For other opioid-related harms such as abuse or dependence, the order was reversed: 60.2 for Blacks and 51.7 for Whites, the investigators reported. Children of all other races were lowest in both measures.

Geography also appears to play a part. The children in urban areas had the lowest rate of adverse events – 23.2 per 100,000 vs. 26.2 (suburban) and 26.7 (rural) – and the highest rate of other opioid-related harms – 58.1 vs. 49.0 (suburban) and 38.7 (rural), the Medicaid claims data showed.

Analysis of prescription fills revealed that black children aged 1-17 years had a significantly lower rate (2.7%) than Whites (3.1%) or those of other races (3.0%) and that urban children were significantly less likely to fill a prescription (2.7%) for opioids than the other two groups (suburban, 3.1%; rural, 3.4%), Mr. Brown and associates said.

The prescription data also showed that 48.4% of children aged 6-17 years who had an adverse event had filled a prescription for an opioid in the previous 6 months, compared with just 9.4% of those with other opioid-related harms. The median length of time since the last fill? Three days for children with an adverse event and 67 days for those with other harms, they said.

And those prescriptions, it turns out, were not coming just from the physicians of North Carolina. Physicians, with 35.5% of the prescription load, were the main source, but 33.3% of opioid fills in 2016-2018 came from dentists, and another 17.7% were written by advanced practice providers. Among physicians, the leading opioid-prescribing specialists were surgeons, with 17.3% of the total, the investigators reported.

“The distinct and separate groups of clinicians who prescribe opioids to children suggest the need for pediatric opioid prescribing guidelines, particularly for postprocedural pain,” Mr. Brown and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Brown KW et al. Health Aff. 2020;39(10):1737-42.

or dependence, compared with their White or rural/suburban counterparts, according to a study of 3.2 million Medicaid-enrolled children in North Carolina.

Analysis of the almost 138,000 prescription fills also showed that Black and urban children in North Carolina were less likely to fill a opioid prescription, suggesting a need “for future studies to explore racial and geographic opioid-related inequities in children,” Kelby W. Brown, MA, and associates at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said Oct. 5 in Health Affairs.

In 2016-2018, the prevalence of opioid-related adverse events, such as poisoning or withdrawal, was 24.0 per 100,000 children among Blacks aged 1-17 years, compared with 27.5 per 100,000 for whites. For other opioid-related harms such as abuse or dependence, the order was reversed: 60.2 for Blacks and 51.7 for Whites, the investigators reported. Children of all other races were lowest in both measures.

Geography also appears to play a part. The children in urban areas had the lowest rate of adverse events – 23.2 per 100,000 vs. 26.2 (suburban) and 26.7 (rural) – and the highest rate of other opioid-related harms – 58.1 vs. 49.0 (suburban) and 38.7 (rural), the Medicaid claims data showed.

Analysis of prescription fills revealed that black children aged 1-17 years had a significantly lower rate (2.7%) than Whites (3.1%) or those of other races (3.0%) and that urban children were significantly less likely to fill a prescription (2.7%) for opioids than the other two groups (suburban, 3.1%; rural, 3.4%), Mr. Brown and associates said.

The prescription data also showed that 48.4% of children aged 6-17 years who had an adverse event had filled a prescription for an opioid in the previous 6 months, compared with just 9.4% of those with other opioid-related harms. The median length of time since the last fill? Three days for children with an adverse event and 67 days for those with other harms, they said.

And those prescriptions, it turns out, were not coming just from the physicians of North Carolina. Physicians, with 35.5% of the prescription load, were the main source, but 33.3% of opioid fills in 2016-2018 came from dentists, and another 17.7% were written by advanced practice providers. Among physicians, the leading opioid-prescribing specialists were surgeons, with 17.3% of the total, the investigators reported.

“The distinct and separate groups of clinicians who prescribe opioids to children suggest the need for pediatric opioid prescribing guidelines, particularly for postprocedural pain,” Mr. Brown and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Brown KW et al. Health Aff. 2020;39(10):1737-42.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

FDA orders stronger warnings on benzodiazepines

The Food and Drug Administration wants updated boxed warnings on benzodiazepines to reflect the “serious” risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions associated with these medications.

“The current prescribing information for benzodiazepines does not provide adequate warnings about these serious risks and harms associated with these medicines so they may be prescribed and used inappropriately,” the FDA said in a safety communication.

The FDA also wants revisions to the patient medication guides for benzodiazepines to help educate patients and caregivers about these risks.

“While benzodiazepines are important therapies for many Americans, they are also commonly abused and misused, often together with opioid pain relievers and other medicines, alcohol, and illicit drugs,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said in a statement.