User login

Phase 3 study of new levodopa/carbidopa delivery system meets all efficacy endpoints

BOSTON – presented at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

When compared with optimized oral immediate-release medication, the delivery system, called ND0612 (NeuroDerm, Rehovot, Israel), improved ON time without troublesome dyskinesias while improving symptoms according to ratings from both patients and clinicians, according to Alberto J. Espay, MD, professor of neurology and director of the Gardner Family Center for Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, University of Cincinnati.

The new delivery system addresses the challenge of reducing the variability in levodopa plasma concentrations, a major factor in motor fluctuations and diminishing benefit from orally administered drug, according to Dr. Espay. He said that continuous infusion strategies have long been sought as a method to preserve levodopa efficacy.

BouNDless findings

There were two phases to this multinational trial, called BouNDless. In the first, an open-label run-in phase, 381 patients with Parkinson’s disease were dose titrated for optimization of oral immediate-release levodopa and carbidopa. They were then optimized for the same drugs delivered with ND0612. The study was conducted over 12 weeks; 122 patients left the study after this phase due to adverse events, lack of efficacy, or withdrawal of consent.

In the second phase, the 259 remaining patients were randomized to the continuous infusion arm or to immediate release oral therapy. In this double-blind, double-dummy phase, those randomized to the ND0612 infusion also received oral placebos. Those randomized to oral therapy received a placebo infusion. Efficacy and safety were assessed at the end of 12 weeks.

At the end of phase 1, the ON time increased by about 3 hours when levodopa-carbidopa dosing was optimized on either delivery method. Dr. Espay attributed the improvement to the value of optimized dosing even in patients with relatively advanced disease.

However, for the purposes of the double-blind comparison, this improvement in ON time provided a new baseline for comparison of the two delivery methods. This is important for interpreting the primary result, which was a 1.72-hour difference in ON time at the end of the study. The difference was created when ON time was maintained with ND0612 continuous drug delivery but eroded in the group randomized to oral immediate-release treatment.

Several secondary endpoints supported the greater efficacy of continuous subcutaneous delivery. These included lower OFF time (0.50 vs. 1.90 hours), less accumulation of disability on the United Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part II-M-EDL (-0.30 vs. +2.75 points), and greater improvement on the Patient Global Impression of Change (+0.31 vs. +0.70 points), and the Clinical Global Impression of change (+0.31 vs. +0.77 points). The differences were highly statistically significant (all P < .0001).

The patients participating in the double-blind phase of the study were similar with a mean age of 63.5 years in both groups and time since Parkinson’s disease diagnosis (> 9 years). The median ON time without troublesome dyskinesias was about 12 hours at baseline in both groups and the median OFF time was about 3.5 hours.

The higher rate of treatment-related adverse events in the ND0612 group (67.2% vs. 52.7%) was largely explained by the greater rate of infusion site reactions (57.0% vs. 42.7%). The rates of severe reactions in the two groups were the same (0.8%), but both mild (43.8% vs. 36.6%) and moderate (12.5% vs. 5.3%) reactions occurred more commonly in the group receiving active therapy.

“Infusion reactions are the Achilles heel of all subcutaneous therapies,” acknowledged Dr. Espay, who expects other infusion systems in development to share this risk. He suggested that the clinical impact can be attenuated to some degree by rotating infusion sites.

BeyoND extension study

Data from an open-label extension (OLE) of the phase 2b BeyoND trial were also presented at the AAN meeting and generated generally similar results. Largely a safety study, there was no active control in the initial BeyoND or the BeyoND OLE. In BeyoND, the improvement in ON time from baseline was even greater than that seen in BouNDless, but, again, the optimization of dosing in the BouNDless run-in established a greater baseline of disease control.

In the OLE of BeyoND, presented by Aaron Ellenbogen, DO, a neurologist in Farmington, Mich., one of the notable findings was the retention of patients. After 2 years of follow-up, 82% completed at least 2 years of follow-up and 66.7% have now remained on treatment for at least 3 years. Dr. Ellenbogen maintains that this retention rate provides compelling evidence of a favorable benefit-to-risk ratio.

Fulfilling an unmet need

The favorable efficacy data from this trial represent “a big advance,” according to Ihtsham Ul Haq, MD, chief, movement disorders division, University of Miami, who was reached for comment. He noted that continuous infusion delivery has been anticipated for some time, and he expects these types of systems to fulfill an unmet need.

“This will be a useful option in a carefully selected group of patients,” said Dr. Haq, who considers the types of improvement in ON time to be highly clinically meaningful.

However, he cautioned that the nodules created by injection site reactions might limit the utility of this treatment option in at least some patients. Wearing the external device might also be a limiting factor for some patients.

In complex Parkinson’s disease, a stage that can be reached fairly rapidly in some patients but might take 15 years or more in others, all of the options involve a careful benefit-to-risk calculation, according to Dr. Haq. Deep brain stimulation is among the most effective options, but continuous infusion might appeal to some patients for delaying this procedure or as an alternative.

“We need multiple options for these types of patients, and it appears that continuous infusion will be one of them,” Dr. Haq said.

Dr. Espay has financial relationships with Acadia, Acorda, Amneal, AskBio, Bexion, Kyowa Kirin, Neuroderm, Neurocrine, and Sunovion. Dr. Ellenbogen has financial relationships with Allergan, Acorda, Supernus, and Teva. Dr. Haq reports no potential conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – presented at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

When compared with optimized oral immediate-release medication, the delivery system, called ND0612 (NeuroDerm, Rehovot, Israel), improved ON time without troublesome dyskinesias while improving symptoms according to ratings from both patients and clinicians, according to Alberto J. Espay, MD, professor of neurology and director of the Gardner Family Center for Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, University of Cincinnati.

The new delivery system addresses the challenge of reducing the variability in levodopa plasma concentrations, a major factor in motor fluctuations and diminishing benefit from orally administered drug, according to Dr. Espay. He said that continuous infusion strategies have long been sought as a method to preserve levodopa efficacy.

BouNDless findings

There were two phases to this multinational trial, called BouNDless. In the first, an open-label run-in phase, 381 patients with Parkinson’s disease were dose titrated for optimization of oral immediate-release levodopa and carbidopa. They were then optimized for the same drugs delivered with ND0612. The study was conducted over 12 weeks; 122 patients left the study after this phase due to adverse events, lack of efficacy, or withdrawal of consent.

In the second phase, the 259 remaining patients were randomized to the continuous infusion arm or to immediate release oral therapy. In this double-blind, double-dummy phase, those randomized to the ND0612 infusion also received oral placebos. Those randomized to oral therapy received a placebo infusion. Efficacy and safety were assessed at the end of 12 weeks.

At the end of phase 1, the ON time increased by about 3 hours when levodopa-carbidopa dosing was optimized on either delivery method. Dr. Espay attributed the improvement to the value of optimized dosing even in patients with relatively advanced disease.

However, for the purposes of the double-blind comparison, this improvement in ON time provided a new baseline for comparison of the two delivery methods. This is important for interpreting the primary result, which was a 1.72-hour difference in ON time at the end of the study. The difference was created when ON time was maintained with ND0612 continuous drug delivery but eroded in the group randomized to oral immediate-release treatment.

Several secondary endpoints supported the greater efficacy of continuous subcutaneous delivery. These included lower OFF time (0.50 vs. 1.90 hours), less accumulation of disability on the United Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part II-M-EDL (-0.30 vs. +2.75 points), and greater improvement on the Patient Global Impression of Change (+0.31 vs. +0.70 points), and the Clinical Global Impression of change (+0.31 vs. +0.77 points). The differences were highly statistically significant (all P < .0001).

The patients participating in the double-blind phase of the study were similar with a mean age of 63.5 years in both groups and time since Parkinson’s disease diagnosis (> 9 years). The median ON time without troublesome dyskinesias was about 12 hours at baseline in both groups and the median OFF time was about 3.5 hours.

The higher rate of treatment-related adverse events in the ND0612 group (67.2% vs. 52.7%) was largely explained by the greater rate of infusion site reactions (57.0% vs. 42.7%). The rates of severe reactions in the two groups were the same (0.8%), but both mild (43.8% vs. 36.6%) and moderate (12.5% vs. 5.3%) reactions occurred more commonly in the group receiving active therapy.

“Infusion reactions are the Achilles heel of all subcutaneous therapies,” acknowledged Dr. Espay, who expects other infusion systems in development to share this risk. He suggested that the clinical impact can be attenuated to some degree by rotating infusion sites.

BeyoND extension study

Data from an open-label extension (OLE) of the phase 2b BeyoND trial were also presented at the AAN meeting and generated generally similar results. Largely a safety study, there was no active control in the initial BeyoND or the BeyoND OLE. In BeyoND, the improvement in ON time from baseline was even greater than that seen in BouNDless, but, again, the optimization of dosing in the BouNDless run-in established a greater baseline of disease control.

In the OLE of BeyoND, presented by Aaron Ellenbogen, DO, a neurologist in Farmington, Mich., one of the notable findings was the retention of patients. After 2 years of follow-up, 82% completed at least 2 years of follow-up and 66.7% have now remained on treatment for at least 3 years. Dr. Ellenbogen maintains that this retention rate provides compelling evidence of a favorable benefit-to-risk ratio.

Fulfilling an unmet need

The favorable efficacy data from this trial represent “a big advance,” according to Ihtsham Ul Haq, MD, chief, movement disorders division, University of Miami, who was reached for comment. He noted that continuous infusion delivery has been anticipated for some time, and he expects these types of systems to fulfill an unmet need.

“This will be a useful option in a carefully selected group of patients,” said Dr. Haq, who considers the types of improvement in ON time to be highly clinically meaningful.

However, he cautioned that the nodules created by injection site reactions might limit the utility of this treatment option in at least some patients. Wearing the external device might also be a limiting factor for some patients.

In complex Parkinson’s disease, a stage that can be reached fairly rapidly in some patients but might take 15 years or more in others, all of the options involve a careful benefit-to-risk calculation, according to Dr. Haq. Deep brain stimulation is among the most effective options, but continuous infusion might appeal to some patients for delaying this procedure or as an alternative.

“We need multiple options for these types of patients, and it appears that continuous infusion will be one of them,” Dr. Haq said.

Dr. Espay has financial relationships with Acadia, Acorda, Amneal, AskBio, Bexion, Kyowa Kirin, Neuroderm, Neurocrine, and Sunovion. Dr. Ellenbogen has financial relationships with Allergan, Acorda, Supernus, and Teva. Dr. Haq reports no potential conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – presented at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

When compared with optimized oral immediate-release medication, the delivery system, called ND0612 (NeuroDerm, Rehovot, Israel), improved ON time without troublesome dyskinesias while improving symptoms according to ratings from both patients and clinicians, according to Alberto J. Espay, MD, professor of neurology and director of the Gardner Family Center for Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, University of Cincinnati.

The new delivery system addresses the challenge of reducing the variability in levodopa plasma concentrations, a major factor in motor fluctuations and diminishing benefit from orally administered drug, according to Dr. Espay. He said that continuous infusion strategies have long been sought as a method to preserve levodopa efficacy.

BouNDless findings

There were two phases to this multinational trial, called BouNDless. In the first, an open-label run-in phase, 381 patients with Parkinson’s disease were dose titrated for optimization of oral immediate-release levodopa and carbidopa. They were then optimized for the same drugs delivered with ND0612. The study was conducted over 12 weeks; 122 patients left the study after this phase due to adverse events, lack of efficacy, or withdrawal of consent.

In the second phase, the 259 remaining patients were randomized to the continuous infusion arm or to immediate release oral therapy. In this double-blind, double-dummy phase, those randomized to the ND0612 infusion also received oral placebos. Those randomized to oral therapy received a placebo infusion. Efficacy and safety were assessed at the end of 12 weeks.

At the end of phase 1, the ON time increased by about 3 hours when levodopa-carbidopa dosing was optimized on either delivery method. Dr. Espay attributed the improvement to the value of optimized dosing even in patients with relatively advanced disease.

However, for the purposes of the double-blind comparison, this improvement in ON time provided a new baseline for comparison of the two delivery methods. This is important for interpreting the primary result, which was a 1.72-hour difference in ON time at the end of the study. The difference was created when ON time was maintained with ND0612 continuous drug delivery but eroded in the group randomized to oral immediate-release treatment.

Several secondary endpoints supported the greater efficacy of continuous subcutaneous delivery. These included lower OFF time (0.50 vs. 1.90 hours), less accumulation of disability on the United Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part II-M-EDL (-0.30 vs. +2.75 points), and greater improvement on the Patient Global Impression of Change (+0.31 vs. +0.70 points), and the Clinical Global Impression of change (+0.31 vs. +0.77 points). The differences were highly statistically significant (all P < .0001).

The patients participating in the double-blind phase of the study were similar with a mean age of 63.5 years in both groups and time since Parkinson’s disease diagnosis (> 9 years). The median ON time without troublesome dyskinesias was about 12 hours at baseline in both groups and the median OFF time was about 3.5 hours.

The higher rate of treatment-related adverse events in the ND0612 group (67.2% vs. 52.7%) was largely explained by the greater rate of infusion site reactions (57.0% vs. 42.7%). The rates of severe reactions in the two groups were the same (0.8%), but both mild (43.8% vs. 36.6%) and moderate (12.5% vs. 5.3%) reactions occurred more commonly in the group receiving active therapy.

“Infusion reactions are the Achilles heel of all subcutaneous therapies,” acknowledged Dr. Espay, who expects other infusion systems in development to share this risk. He suggested that the clinical impact can be attenuated to some degree by rotating infusion sites.

BeyoND extension study

Data from an open-label extension (OLE) of the phase 2b BeyoND trial were also presented at the AAN meeting and generated generally similar results. Largely a safety study, there was no active control in the initial BeyoND or the BeyoND OLE. In BeyoND, the improvement in ON time from baseline was even greater than that seen in BouNDless, but, again, the optimization of dosing in the BouNDless run-in established a greater baseline of disease control.

In the OLE of BeyoND, presented by Aaron Ellenbogen, DO, a neurologist in Farmington, Mich., one of the notable findings was the retention of patients. After 2 years of follow-up, 82% completed at least 2 years of follow-up and 66.7% have now remained on treatment for at least 3 years. Dr. Ellenbogen maintains that this retention rate provides compelling evidence of a favorable benefit-to-risk ratio.

Fulfilling an unmet need

The favorable efficacy data from this trial represent “a big advance,” according to Ihtsham Ul Haq, MD, chief, movement disorders division, University of Miami, who was reached for comment. He noted that continuous infusion delivery has been anticipated for some time, and he expects these types of systems to fulfill an unmet need.

“This will be a useful option in a carefully selected group of patients,” said Dr. Haq, who considers the types of improvement in ON time to be highly clinically meaningful.

However, he cautioned that the nodules created by injection site reactions might limit the utility of this treatment option in at least some patients. Wearing the external device might also be a limiting factor for some patients.

In complex Parkinson’s disease, a stage that can be reached fairly rapidly in some patients but might take 15 years or more in others, all of the options involve a careful benefit-to-risk calculation, according to Dr. Haq. Deep brain stimulation is among the most effective options, but continuous infusion might appeal to some patients for delaying this procedure or as an alternative.

“We need multiple options for these types of patients, and it appears that continuous infusion will be one of them,” Dr. Haq said.

Dr. Espay has financial relationships with Acadia, Acorda, Amneal, AskBio, Bexion, Kyowa Kirin, Neuroderm, Neurocrine, and Sunovion. Dr. Ellenbogen has financial relationships with Allergan, Acorda, Supernus, and Teva. Dr. Haq reports no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM AAN 2023

New assay hailed as a game changer for early Parkinson’s diagnosis

, and provides information on molecular subtypes, new research indicates.

“Identifying an effective biomarker for Parkinson’s disease pathology could have profound implications for the way we treat the condition, potentially making it possible to diagnose people earlier, identify the best treatments for different subsets of patients, and speed up clinical trials,” the study’s co-lead author Andrew Siderowf, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in a news release.

“Our findings suggest that the αSyn-SAA technique is highly accurate at detecting the biomarker for Parkinson’s disease regardless of the clinical features, making it possible to accurately diagnose the disease in patients at early stages,” added co-lead author Luis Concha-Marambio, PhD, director of research and development at Amprion, San Diego, Calif.

The study was published online in The Lancet Neurology.

‘New era’ in Parkinson’s disease

The researchers assessed the usefulness of αSyn-SAA in a cross-sectional analysis of 1,123 participants in the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) cohort from 33 participating academic neurology outpatient practices in 12 countries.

The cohort included individuals with sporadic Parkinson’s disease from LRRK2 or GBA variants, healthy controls, individuals with clinical syndromes prodromal to Parkinson’s disease (rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder [RBD] or hyposmia), and nonmanifesting carriers of LRRK2 and GBA variants. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from each participant were analyzed using αSyn-SAA.

Overall, αSyn-SAA differentiated Parkinson’s disease from healthy controls with 87.7% sensitivity and 96.3% specificity.

Sensitivity of the assay varied across subgroups based on genetic and clinical features. Among genetic Parkinson’s disease subgroups, sensitivity was highest for GBA Parkinson’s disease (95.9%), followed by sporadic Parkinson’s disease (93.3%), and lowest for LRRK2 Parkinson’s disease (67.5%). Among clinical features, hyposmia was the most robust predictor of a positive assay result.

Among all Parkinson’s disease cases with hyposmia, the sensitivity of the assay was 97.2%, compared with 63.0% for Parkinson’s disease without olfactory dysfunction. Combining genetic and clinical features, the sensitivity of positive αSyn-SAA in sporadic Parkinson’s disease with olfactory deficit was 98.6%, compared with 78.3% in sporadic Parkinson’s disease without hyposmia. Most prodromal participants (86%) with RBD and hyposmia had positive αSyn-SAA results, indicating they had α-synuclein aggregates despite not yet being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Among those recruited based on their loss of smell, 89% (16 of 18 participants) had positive αSyn-SAA results. Similarly, in those with RBD, positive αSyn-SAA results were present in 85% of cases (28 of 33). No other clinical features were associated with a positive αSyn-SAA result.

In participants who carried LRRK2 or GBA variants but had no Parkinson’s disease diagnosis or prodromal symptoms (nonmanifesting carriers), 9% (14 of 159) and 7% (11 of 151), respectively, had positive αSyn-SAA results.

To date, this is the largest analysis of α-Syn-SAA for the biochemical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, the researchers said.

The results show that the assay classifies people with Parkinson’s disease with “high sensitivity and specificity, provides information about molecular heterogeneity, and detects prodromal individuals before diagnosis,” they wrote.

“These findings suggest a crucial role for the α-synuclein SAA in therapeutic development, both to identify pathologically defined subgroups of people with Parkinson’s disease and to establish biomarker-defined at-risk cohorts,” they added.

Amprion has commercialized the assay (SYNTap test), which can be ordered online.

‘Seminal development’

The authors of an accompanying editorial noted the study “lays the foundation for a biological diagnosis” of Parkinson’s disease. “We have entered a new era of biomarker and treatment development for Parkinson’s disease. The possibility of detecting a misfolded α-synuclein, the pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease, by employing an SSA, is a seminal development,” wrote Daniela Berg, MD, PhD, and Christine Klein, MD, with University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

“However, to fully leverage the enormous potential of the α-synuclein seed amplification, the test would have to be performed in blood rather than the CSF, a less invasive approach that has proven to be viable,” they added.

“Although the blood-based method needs to be further elaborated for scalability, α-synuclein SAA is a game changer in Parkinson’s disease diagnostics, research, and treatment trials,” they concluded.

The study was funded by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and a consortium of more than 40 private and philanthropic partners. Dr. Siderowf has declared consulting for Merck and Parkinson Study Group, and receiving honoraria from Bial. A full list of author disclosures is available with the original article. Dr. Berg and Dr. Klein have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, and provides information on molecular subtypes, new research indicates.

“Identifying an effective biomarker for Parkinson’s disease pathology could have profound implications for the way we treat the condition, potentially making it possible to diagnose people earlier, identify the best treatments for different subsets of patients, and speed up clinical trials,” the study’s co-lead author Andrew Siderowf, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in a news release.

“Our findings suggest that the αSyn-SAA technique is highly accurate at detecting the biomarker for Parkinson’s disease regardless of the clinical features, making it possible to accurately diagnose the disease in patients at early stages,” added co-lead author Luis Concha-Marambio, PhD, director of research and development at Amprion, San Diego, Calif.

The study was published online in The Lancet Neurology.

‘New era’ in Parkinson’s disease

The researchers assessed the usefulness of αSyn-SAA in a cross-sectional analysis of 1,123 participants in the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) cohort from 33 participating academic neurology outpatient practices in 12 countries.

The cohort included individuals with sporadic Parkinson’s disease from LRRK2 or GBA variants, healthy controls, individuals with clinical syndromes prodromal to Parkinson’s disease (rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder [RBD] or hyposmia), and nonmanifesting carriers of LRRK2 and GBA variants. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from each participant were analyzed using αSyn-SAA.

Overall, αSyn-SAA differentiated Parkinson’s disease from healthy controls with 87.7% sensitivity and 96.3% specificity.

Sensitivity of the assay varied across subgroups based on genetic and clinical features. Among genetic Parkinson’s disease subgroups, sensitivity was highest for GBA Parkinson’s disease (95.9%), followed by sporadic Parkinson’s disease (93.3%), and lowest for LRRK2 Parkinson’s disease (67.5%). Among clinical features, hyposmia was the most robust predictor of a positive assay result.

Among all Parkinson’s disease cases with hyposmia, the sensitivity of the assay was 97.2%, compared with 63.0% for Parkinson’s disease without olfactory dysfunction. Combining genetic and clinical features, the sensitivity of positive αSyn-SAA in sporadic Parkinson’s disease with olfactory deficit was 98.6%, compared with 78.3% in sporadic Parkinson’s disease without hyposmia. Most prodromal participants (86%) with RBD and hyposmia had positive αSyn-SAA results, indicating they had α-synuclein aggregates despite not yet being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Among those recruited based on their loss of smell, 89% (16 of 18 participants) had positive αSyn-SAA results. Similarly, in those with RBD, positive αSyn-SAA results were present in 85% of cases (28 of 33). No other clinical features were associated with a positive αSyn-SAA result.

In participants who carried LRRK2 or GBA variants but had no Parkinson’s disease diagnosis or prodromal symptoms (nonmanifesting carriers), 9% (14 of 159) and 7% (11 of 151), respectively, had positive αSyn-SAA results.

To date, this is the largest analysis of α-Syn-SAA for the biochemical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, the researchers said.

The results show that the assay classifies people with Parkinson’s disease with “high sensitivity and specificity, provides information about molecular heterogeneity, and detects prodromal individuals before diagnosis,” they wrote.

“These findings suggest a crucial role for the α-synuclein SAA in therapeutic development, both to identify pathologically defined subgroups of people with Parkinson’s disease and to establish biomarker-defined at-risk cohorts,” they added.

Amprion has commercialized the assay (SYNTap test), which can be ordered online.

‘Seminal development’

The authors of an accompanying editorial noted the study “lays the foundation for a biological diagnosis” of Parkinson’s disease. “We have entered a new era of biomarker and treatment development for Parkinson’s disease. The possibility of detecting a misfolded α-synuclein, the pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease, by employing an SSA, is a seminal development,” wrote Daniela Berg, MD, PhD, and Christine Klein, MD, with University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

“However, to fully leverage the enormous potential of the α-synuclein seed amplification, the test would have to be performed in blood rather than the CSF, a less invasive approach that has proven to be viable,” they added.

“Although the blood-based method needs to be further elaborated for scalability, α-synuclein SAA is a game changer in Parkinson’s disease diagnostics, research, and treatment trials,” they concluded.

The study was funded by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and a consortium of more than 40 private and philanthropic partners. Dr. Siderowf has declared consulting for Merck and Parkinson Study Group, and receiving honoraria from Bial. A full list of author disclosures is available with the original article. Dr. Berg and Dr. Klein have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, and provides information on molecular subtypes, new research indicates.

“Identifying an effective biomarker for Parkinson’s disease pathology could have profound implications for the way we treat the condition, potentially making it possible to diagnose people earlier, identify the best treatments for different subsets of patients, and speed up clinical trials,” the study’s co-lead author Andrew Siderowf, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in a news release.

“Our findings suggest that the αSyn-SAA technique is highly accurate at detecting the biomarker for Parkinson’s disease regardless of the clinical features, making it possible to accurately diagnose the disease in patients at early stages,” added co-lead author Luis Concha-Marambio, PhD, director of research and development at Amprion, San Diego, Calif.

The study was published online in The Lancet Neurology.

‘New era’ in Parkinson’s disease

The researchers assessed the usefulness of αSyn-SAA in a cross-sectional analysis of 1,123 participants in the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) cohort from 33 participating academic neurology outpatient practices in 12 countries.

The cohort included individuals with sporadic Parkinson’s disease from LRRK2 or GBA variants, healthy controls, individuals with clinical syndromes prodromal to Parkinson’s disease (rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder [RBD] or hyposmia), and nonmanifesting carriers of LRRK2 and GBA variants. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from each participant were analyzed using αSyn-SAA.

Overall, αSyn-SAA differentiated Parkinson’s disease from healthy controls with 87.7% sensitivity and 96.3% specificity.

Sensitivity of the assay varied across subgroups based on genetic and clinical features. Among genetic Parkinson’s disease subgroups, sensitivity was highest for GBA Parkinson’s disease (95.9%), followed by sporadic Parkinson’s disease (93.3%), and lowest for LRRK2 Parkinson’s disease (67.5%). Among clinical features, hyposmia was the most robust predictor of a positive assay result.

Among all Parkinson’s disease cases with hyposmia, the sensitivity of the assay was 97.2%, compared with 63.0% for Parkinson’s disease without olfactory dysfunction. Combining genetic and clinical features, the sensitivity of positive αSyn-SAA in sporadic Parkinson’s disease with olfactory deficit was 98.6%, compared with 78.3% in sporadic Parkinson’s disease without hyposmia. Most prodromal participants (86%) with RBD and hyposmia had positive αSyn-SAA results, indicating they had α-synuclein aggregates despite not yet being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Among those recruited based on their loss of smell, 89% (16 of 18 participants) had positive αSyn-SAA results. Similarly, in those with RBD, positive αSyn-SAA results were present in 85% of cases (28 of 33). No other clinical features were associated with a positive αSyn-SAA result.

In participants who carried LRRK2 or GBA variants but had no Parkinson’s disease diagnosis or prodromal symptoms (nonmanifesting carriers), 9% (14 of 159) and 7% (11 of 151), respectively, had positive αSyn-SAA results.

To date, this is the largest analysis of α-Syn-SAA for the biochemical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, the researchers said.

The results show that the assay classifies people with Parkinson’s disease with “high sensitivity and specificity, provides information about molecular heterogeneity, and detects prodromal individuals before diagnosis,” they wrote.

“These findings suggest a crucial role for the α-synuclein SAA in therapeutic development, both to identify pathologically defined subgroups of people with Parkinson’s disease and to establish biomarker-defined at-risk cohorts,” they added.

Amprion has commercialized the assay (SYNTap test), which can be ordered online.

‘Seminal development’

The authors of an accompanying editorial noted the study “lays the foundation for a biological diagnosis” of Parkinson’s disease. “We have entered a new era of biomarker and treatment development for Parkinson’s disease. The possibility of detecting a misfolded α-synuclein, the pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease, by employing an SSA, is a seminal development,” wrote Daniela Berg, MD, PhD, and Christine Klein, MD, with University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

“However, to fully leverage the enormous potential of the α-synuclein seed amplification, the test would have to be performed in blood rather than the CSF, a less invasive approach that has proven to be viable,” they added.

“Although the blood-based method needs to be further elaborated for scalability, α-synuclein SAA is a game changer in Parkinson’s disease diagnostics, research, and treatment trials,” they concluded.

The study was funded by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and a consortium of more than 40 private and philanthropic partners. Dr. Siderowf has declared consulting for Merck and Parkinson Study Group, and receiving honoraria from Bial. A full list of author disclosures is available with the original article. Dr. Berg and Dr. Klein have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET NEUROLOGY

Mississippi–Ohio River valley linked to higher risk of Parkinson’s disease

according to findings from a study that was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The association was attributed to concentrations of particulate matter (PM) 2.5 in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, which was on average higher than in other areas, but that didn’t entirely explain the increase in Parkinson’s disease in that region, Brittany Krzyzanowski, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in the neuroepidemiology research program of the department of neurology at Barrow Neurological Institute, Dignity Health St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, said in an interview.

“This study revealed Parkinson’s disease hot spots in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, a region that has some of the highest levels of air pollution in the nation,” she said, “but we also still find a relationship between air pollution and Parkinson’s risk in the regions in the western half of the United States where Parkinson’s disease and air pollution levels are relatively low.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski and colleagues evaluated 22,546,965 Medicare beneficiaries in 2009, using a multimethod approach that included geospatial analytical techniques to categorize their exposure to PM2.5 based on age, sex, race, smoking status, and health care usage. The researchers also performed individual-level case-control analysis to assess PM2.5 results at the county level. The Medicare beneficiaries were grouped according to average exposure, with the lowest group having an average annual exposure of 5 mcg/m3 and the group with the highest exposure having an average annual exposure of 19 mcg/m3.

In total, researchers identified 83,674 Medicare beneficiaries with incident Parkinson’s disease, with 434 new cases per 100,000 people in the highest exposure group, compared with 359 new cases per 100,000 people in the lowest-exposure group. The relative risk for Parkinson’s disease increased in the highest quartile of PM2.5 by 25%, compared with the lowest quartile after adjusting for factors such as age, smoking status, and health care usage (95% confidence interval, 20%–29%).

The results showed the nationwide average annual PM2.5 was associated with incident Parkinson’s disease, and the Rocky Mountain region carried a strong association between PM2.5 and Parkson’s disease with a 16% increase in risk per level of exposure to PM2.5. While the Mississippi-Ohio River valley was also associated with Parkinson’s disease, there was a weaker association between PM2.5 and Parkinson’s disease, which the researchers attributed to a “ceiling effect” of PM2.5 between approximately 12-19 mcg/m3.

Dr. Krzyzanowski said that use of a large-population-based dataset and high-resolution location data were major strengths of the study. “Having this level of information leaves less room for uncertainty in our measures and analyses,” she said. “Our study also leveraged innovative geographic information systems which allowed us to refine local patterns of disease by using population behavior and demographic information (such as smoking and age) to ensure that we could provide the most accurate map representation available to date.”

A focus on air pollution

Existing research in examining the etiology of Parkinson’s mainly focused on exposure to pesticides,* Dr. Krzyzanowski explained, and “consists of studies using relatively small populations and low-resolution air pollution data.” Genetics is another possible cause, she noted, but only explains some Parkinson’s disease cases.

“Our work suggests that we should also be looking at air pollution as a contributor in the development of Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

Ray Dorsey, MD, professor of neurology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), who was not involved with the study, said that evidence is mounting that “air pollution may be an important causal factor in Parkinson’s and especially Alzheimer’s disease.”

“This study by a well-regarded group of researchers adds epidemiological evidence for that association,” he said. Another strength is that the study was conducted in the United States, as many epidemiological studies evaluating air pollution and Parkinson’s disease have been performed outside the country because of “a dearth of reliable data sources.”

“This study, along with others, suggest that some of the important environmental toxicants tied to brain disease may be inhaled,” Dr. Dorsey said. “The nose may be the front door to the brain.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski said the next step in their research is further examination of different types of air pollution. “Air pollution contains a variety of toxic components which vary from region to region. Understanding the different components in air pollution and how they interact with climate, temperature, and topography could help explain the regional differences we observed.”

One potential limitation in the study is a lag between air pollution exposure and development of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Dorsey noted.

“Here, it looks like (but I am not certain) that the investigators looked at current air pollution levels and new cases of Parkinson’s. Ideally, for incident cases of Parkinson’s disease, we would want to know historical data on exposure to air pollution,” he said.

Future studies should include prospective evaluation of adults as well as babies and children who have been exposed to both high and low levels of air pollution. That kind of study “would be incredibly valuable for determining the role of an important environmental toxicant in many brain diseases, including stroke, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s,” he said.

Dr. Krzyzanowski and Dr. Dorsey reported no relevant financial disclosures. This study was supported by grants from the Department of Defense, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

*Correction, 4/14/23: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the disease that was the subject of this research.

according to findings from a study that was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The association was attributed to concentrations of particulate matter (PM) 2.5 in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, which was on average higher than in other areas, but that didn’t entirely explain the increase in Parkinson’s disease in that region, Brittany Krzyzanowski, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in the neuroepidemiology research program of the department of neurology at Barrow Neurological Institute, Dignity Health St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, said in an interview.

“This study revealed Parkinson’s disease hot spots in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, a region that has some of the highest levels of air pollution in the nation,” she said, “but we also still find a relationship between air pollution and Parkinson’s risk in the regions in the western half of the United States where Parkinson’s disease and air pollution levels are relatively low.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski and colleagues evaluated 22,546,965 Medicare beneficiaries in 2009, using a multimethod approach that included geospatial analytical techniques to categorize their exposure to PM2.5 based on age, sex, race, smoking status, and health care usage. The researchers also performed individual-level case-control analysis to assess PM2.5 results at the county level. The Medicare beneficiaries were grouped according to average exposure, with the lowest group having an average annual exposure of 5 mcg/m3 and the group with the highest exposure having an average annual exposure of 19 mcg/m3.

In total, researchers identified 83,674 Medicare beneficiaries with incident Parkinson’s disease, with 434 new cases per 100,000 people in the highest exposure group, compared with 359 new cases per 100,000 people in the lowest-exposure group. The relative risk for Parkinson’s disease increased in the highest quartile of PM2.5 by 25%, compared with the lowest quartile after adjusting for factors such as age, smoking status, and health care usage (95% confidence interval, 20%–29%).

The results showed the nationwide average annual PM2.5 was associated with incident Parkinson’s disease, and the Rocky Mountain region carried a strong association between PM2.5 and Parkson’s disease with a 16% increase in risk per level of exposure to PM2.5. While the Mississippi-Ohio River valley was also associated with Parkinson’s disease, there was a weaker association between PM2.5 and Parkinson’s disease, which the researchers attributed to a “ceiling effect” of PM2.5 between approximately 12-19 mcg/m3.

Dr. Krzyzanowski said that use of a large-population-based dataset and high-resolution location data were major strengths of the study. “Having this level of information leaves less room for uncertainty in our measures and analyses,” she said. “Our study also leveraged innovative geographic information systems which allowed us to refine local patterns of disease by using population behavior and demographic information (such as smoking and age) to ensure that we could provide the most accurate map representation available to date.”

A focus on air pollution

Existing research in examining the etiology of Parkinson’s mainly focused on exposure to pesticides,* Dr. Krzyzanowski explained, and “consists of studies using relatively small populations and low-resolution air pollution data.” Genetics is another possible cause, she noted, but only explains some Parkinson’s disease cases.

“Our work suggests that we should also be looking at air pollution as a contributor in the development of Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

Ray Dorsey, MD, professor of neurology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), who was not involved with the study, said that evidence is mounting that “air pollution may be an important causal factor in Parkinson’s and especially Alzheimer’s disease.”

“This study by a well-regarded group of researchers adds epidemiological evidence for that association,” he said. Another strength is that the study was conducted in the United States, as many epidemiological studies evaluating air pollution and Parkinson’s disease have been performed outside the country because of “a dearth of reliable data sources.”

“This study, along with others, suggest that some of the important environmental toxicants tied to brain disease may be inhaled,” Dr. Dorsey said. “The nose may be the front door to the brain.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski said the next step in their research is further examination of different types of air pollution. “Air pollution contains a variety of toxic components which vary from region to region. Understanding the different components in air pollution and how they interact with climate, temperature, and topography could help explain the regional differences we observed.”

One potential limitation in the study is a lag between air pollution exposure and development of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Dorsey noted.

“Here, it looks like (but I am not certain) that the investigators looked at current air pollution levels and new cases of Parkinson’s. Ideally, for incident cases of Parkinson’s disease, we would want to know historical data on exposure to air pollution,” he said.

Future studies should include prospective evaluation of adults as well as babies and children who have been exposed to both high and low levels of air pollution. That kind of study “would be incredibly valuable for determining the role of an important environmental toxicant in many brain diseases, including stroke, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s,” he said.

Dr. Krzyzanowski and Dr. Dorsey reported no relevant financial disclosures. This study was supported by grants from the Department of Defense, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

*Correction, 4/14/23: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the disease that was the subject of this research.

according to findings from a study that was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The association was attributed to concentrations of particulate matter (PM) 2.5 in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, which was on average higher than in other areas, but that didn’t entirely explain the increase in Parkinson’s disease in that region, Brittany Krzyzanowski, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in the neuroepidemiology research program of the department of neurology at Barrow Neurological Institute, Dignity Health St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, said in an interview.

“This study revealed Parkinson’s disease hot spots in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, a region that has some of the highest levels of air pollution in the nation,” she said, “but we also still find a relationship between air pollution and Parkinson’s risk in the regions in the western half of the United States where Parkinson’s disease and air pollution levels are relatively low.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski and colleagues evaluated 22,546,965 Medicare beneficiaries in 2009, using a multimethod approach that included geospatial analytical techniques to categorize their exposure to PM2.5 based on age, sex, race, smoking status, and health care usage. The researchers also performed individual-level case-control analysis to assess PM2.5 results at the county level. The Medicare beneficiaries were grouped according to average exposure, with the lowest group having an average annual exposure of 5 mcg/m3 and the group with the highest exposure having an average annual exposure of 19 mcg/m3.

In total, researchers identified 83,674 Medicare beneficiaries with incident Parkinson’s disease, with 434 new cases per 100,000 people in the highest exposure group, compared with 359 new cases per 100,000 people in the lowest-exposure group. The relative risk for Parkinson’s disease increased in the highest quartile of PM2.5 by 25%, compared with the lowest quartile after adjusting for factors such as age, smoking status, and health care usage (95% confidence interval, 20%–29%).

The results showed the nationwide average annual PM2.5 was associated with incident Parkinson’s disease, and the Rocky Mountain region carried a strong association between PM2.5 and Parkson’s disease with a 16% increase in risk per level of exposure to PM2.5. While the Mississippi-Ohio River valley was also associated with Parkinson’s disease, there was a weaker association between PM2.5 and Parkinson’s disease, which the researchers attributed to a “ceiling effect” of PM2.5 between approximately 12-19 mcg/m3.

Dr. Krzyzanowski said that use of a large-population-based dataset and high-resolution location data were major strengths of the study. “Having this level of information leaves less room for uncertainty in our measures and analyses,” she said. “Our study also leveraged innovative geographic information systems which allowed us to refine local patterns of disease by using population behavior and demographic information (such as smoking and age) to ensure that we could provide the most accurate map representation available to date.”

A focus on air pollution

Existing research in examining the etiology of Parkinson’s mainly focused on exposure to pesticides,* Dr. Krzyzanowski explained, and “consists of studies using relatively small populations and low-resolution air pollution data.” Genetics is another possible cause, she noted, but only explains some Parkinson’s disease cases.

“Our work suggests that we should also be looking at air pollution as a contributor in the development of Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

Ray Dorsey, MD, professor of neurology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), who was not involved with the study, said that evidence is mounting that “air pollution may be an important causal factor in Parkinson’s and especially Alzheimer’s disease.”

“This study by a well-regarded group of researchers adds epidemiological evidence for that association,” he said. Another strength is that the study was conducted in the United States, as many epidemiological studies evaluating air pollution and Parkinson’s disease have been performed outside the country because of “a dearth of reliable data sources.”

“This study, along with others, suggest that some of the important environmental toxicants tied to brain disease may be inhaled,” Dr. Dorsey said. “The nose may be the front door to the brain.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski said the next step in their research is further examination of different types of air pollution. “Air pollution contains a variety of toxic components which vary from region to region. Understanding the different components in air pollution and how they interact with climate, temperature, and topography could help explain the regional differences we observed.”

One potential limitation in the study is a lag between air pollution exposure and development of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Dorsey noted.

“Here, it looks like (but I am not certain) that the investigators looked at current air pollution levels and new cases of Parkinson’s. Ideally, for incident cases of Parkinson’s disease, we would want to know historical data on exposure to air pollution,” he said.

Future studies should include prospective evaluation of adults as well as babies and children who have been exposed to both high and low levels of air pollution. That kind of study “would be incredibly valuable for determining the role of an important environmental toxicant in many brain diseases, including stroke, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s,” he said.

Dr. Krzyzanowski and Dr. Dorsey reported no relevant financial disclosures. This study was supported by grants from the Department of Defense, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

*Correction, 4/14/23: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the disease that was the subject of this research.

FROM AAN 2023

Picking up the premotor symptoms of Parkinson’s

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

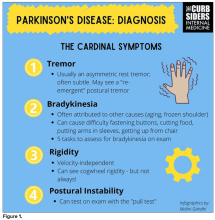

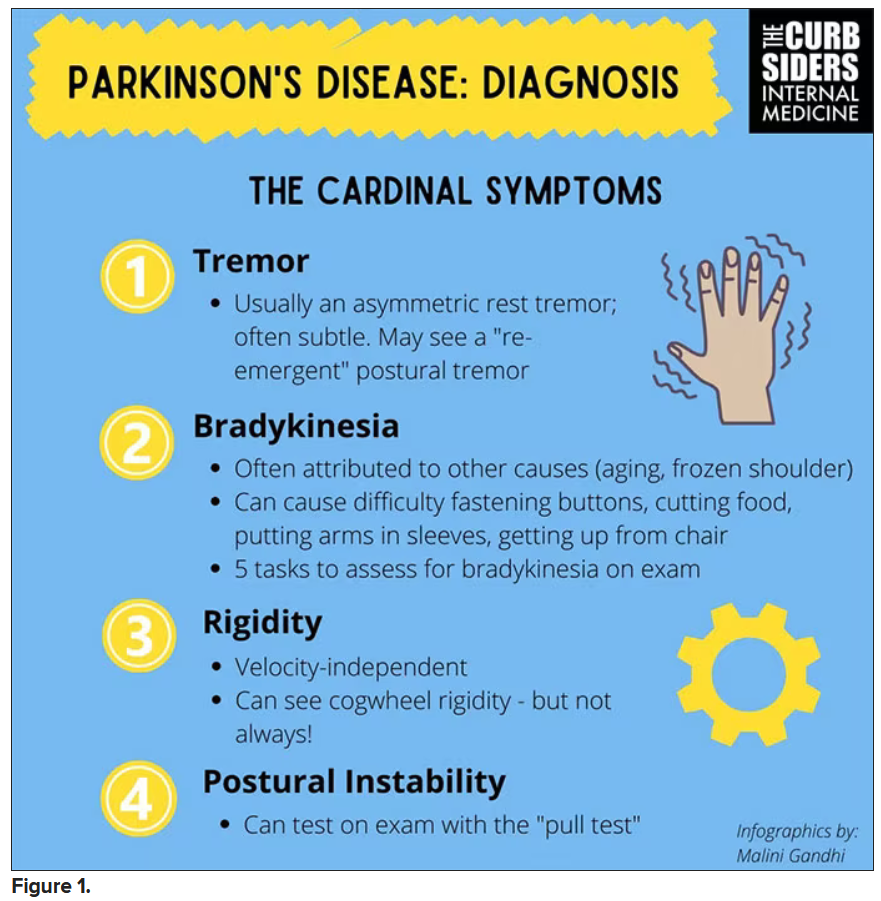

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

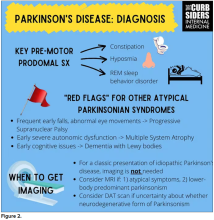

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

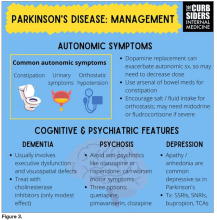

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Parkinson’s disease: What’s trauma got to do with it?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Kathrin LaFaver, MD: Hello. I’m happy to talk today to Dr. Indu Subramanian, clinical professor at University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education and Clinical Center in Los Angeles. I am a neurologist in Saratoga Springs, New York, and we will be talking today about Indu’s new paper on childhood trauma and Parkinson’s disease. Welcome and thanks for taking the time.

Indu Subramanian, MD: Thank you so much for letting us highlight this important topic.

Dr. LaFaver: There are many papers published every month on Parkinson’s disease, but this topic stands out because it’s not a thing that has been commonly looked at. What gave you the idea to study this?

Neurology behind other specialties

Dr. Subramanian: Kathrin, you and I have been looking at things that can inform us about our patients – the person who’s standing in front of us when they come in and we’re giving them this diagnosis. I think that so much of what we’ve done [in the past] is a cookie cutter approach to giving everybody the standard treatment. [We’ve been assuming that] It doesn’t matter if they’re a man or woman. It doesn’t matter if they’re a veteran. It doesn’t matter if they may be from a minoritized population.

We’ve also been interested in approaches that are outside the box, right? We have this integrative medicine and lifestyle medicine background. I’ve been going to those meetings and really been struck by the mounting evidence on the importance of things like early adverse childhood events (ACEs), what zip code you live in, what your pollution index is, and how these things can affect people through their life and their health.

I think that it is high time neurologists pay attention to this. There’s been mounting evidence throughout many disease states, various types of cancers, and mental health. Cardiology is much more advanced, but we haven’t had much data in neurology. In fact, when we went to write this paper, there were just one or two papers that were looking at multiple sclerosis or general neurologic issues, but really nothing in Parkinson’s disease.

We know that Parkinson’s disease is not only a motor disease that affects mental health, but that it also affects nonmotor issues. Childhood adversity may affect how people progress or how quickly they may get a disease, and we were interested in how it may manifest in a disease like Parkinson’s disease.

That was the framework going to meetings. As we wrote this paper and were in various editing stages, there was a beautiful paper that came out by Nadine Burke Harris and team that really was a call to action for neurologists and caring about trauma.

Dr. LaFaver: I couldn’t agree more. It’s really an underrecognized issue. With my own background, being very interested in functional movement disorders, psychosomatic disorders, and so on, it becomes much more evident how common a trauma background is, not only for people we were traditionally asking about.

Why don’t you summarize your findings for us?

Adverse childhood events

Dr. Subramanian: This is a web-based survey, so obviously, these are patient self-reports of their disease. We have a large cohort of people that we’ve been following over 7 years. I’m looking at modifiable variables and what really impacts Parkinson’s disease. Some of our previous papers have looked at diet, exercise, and loneliness. This is the same cohort.

We ended up putting the ACEs questionnaire, which is 10 questions looking at whether you were exposed to certain things in your household below the age of 18. This is a relatively standard questionnaire that’s administered one time, and you get a score out of 10. This is something that has been pushed, at least in the state of California, as something that we should be checking more in all people coming in.

We introduced the survey, and we didn’t force everyone to take it. Unfortunately, there was 20% or so of our patients who chose not to answer these questions. One has to ask, who are those people that didn’t answer the questions? Are they the ones that may have had trauma and these questions were triggering? It was a gap. We didn’t add extra questions to explore why people didn’t answer those questions.

We have to also put this in context. We have a patient population that’s largely quite affluent, who are able to access web-based surveys through their computer, and largely Caucasian; there are not many minoritized populations in our cohort. We want to do better with that. We actually were able to gather a decent number of women. We represent women quite well in our survey. I think that’s because of this online approach and some of the things that we’re studying.

In our survey, we broke it down into people who had no ACEs, one to three ACEs, or four or more ACEs. This is a standard way to break down ACEs so that we’re able to categorize what to do with these patient populations.

What we saw – and it’s preliminary evidence – is that people who had higher ACE scores seemed to have more symptom severity when we controlled for things like years since diagnosis, age, and gender. They also seem to have a worse quality of life. There was some indication that there were more nonmotor issues in those populations, as you might expect, such as anxiety, depression, and things that presumably ACEs can affect separately.

There are some confounders, but I think we really want to use this as the first piece of evidence to hopefully pave the way for caring about trauma in Parkinson’s disease moving forward.

Dr. LaFaver: Thank you so much for that summary. You already mentioned the main methodology you used.

What is the next step for you? How do you see these findings informing our clinical care? Do you have suggestions for all of the neurologists listening in this regard?

PD not yet considered ACE-related

Dr. Subramanian: Dr. Burke Harris was the former surgeon general in California. She’s a woman of color and a brilliant speaker, and she had worked in inner cities, I think in San Francisco, with pediatric populations, seeing these effects of adversity in that time frame.

You see this population at risk, and then you’re following this cohort, which we knew from the Kaiser cohort determines earlier morbidity and mortality across a number of disease states. We’re seeing things like more heart attacks, more diabetes, and all kinds of things in these populations. This is not new news; we just have not been focusing on this.

In her paper, this call to action, they had talked about some ACE-related conditions that currently do not include Parkinson’s disease. There are three ACE-related neurologic conditions that people should be aware of. One is in the headache/pain universe. Another is in the stroke universe, and that’s understandable, given cardiovascular risk factors . Then the third is in this dementia risk category. I think Parkinson’s disease, as we know, can be associated with dementia. A large percentage of our patients get dementia, but we don’t have Parkinson’s disease called out in this framework.