User login

Product update: Neuromodulation device, cystoscopy simplified, hysteroscopy seal, next immunization frontier

NEW SACRAL NEUROMODULATION DEVICE

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.axonics.com/

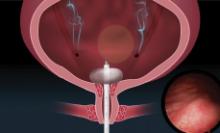

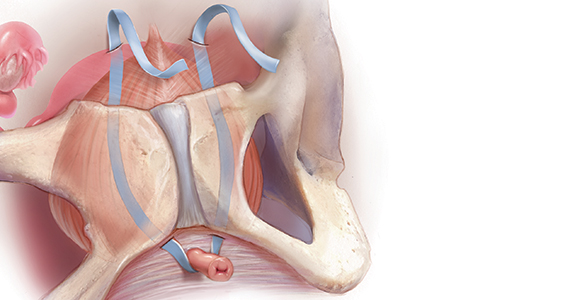

CERVICAL SEAL FOR HYSTEROSCOPIC DEVICES

For more information, visit: https://gynsurgicalsolutions.com/product/omni-lok/

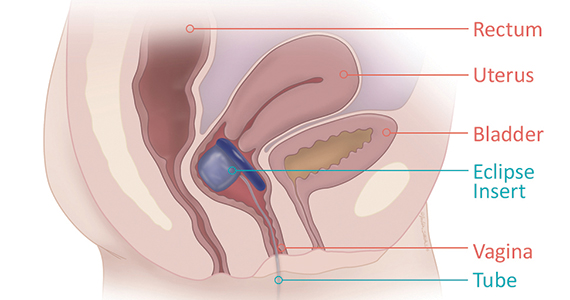

UNIVERSAL CYSTOSCOPY SIMPLIFIED

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://cystosure.com/

NEXT FRONTIER IN VACCINE IMMUNIZATION

Globally, there are 410,000 cases of GBS every year. GBS is most common in newborns; women who are carriers of the GBS bacteria may pass it on to their newborns during labor and birth. An estimated 10% to 30% of pregnant women carry the GBS bacteria. The disease can manifest as sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis, with potentially fatal outcomes for some. A maternal vaccine may prevent 231,000 infant and maternal GBS cases, says Pfizer.

According to Pfizer, RSV causes more hospitalizations each year than influenza among young children, with an estimated 33 million cases globally each year in children less than age 5 years.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.pfizer.com/

NEW SACRAL NEUROMODULATION DEVICE

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.axonics.com/

CERVICAL SEAL FOR HYSTEROSCOPIC DEVICES

For more information, visit: https://gynsurgicalsolutions.com/product/omni-lok/

UNIVERSAL CYSTOSCOPY SIMPLIFIED

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://cystosure.com/

NEXT FRONTIER IN VACCINE IMMUNIZATION

Globally, there are 410,000 cases of GBS every year. GBS is most common in newborns; women who are carriers of the GBS bacteria may pass it on to their newborns during labor and birth. An estimated 10% to 30% of pregnant women carry the GBS bacteria. The disease can manifest as sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis, with potentially fatal outcomes for some. A maternal vaccine may prevent 231,000 infant and maternal GBS cases, says Pfizer.

According to Pfizer, RSV causes more hospitalizations each year than influenza among young children, with an estimated 33 million cases globally each year in children less than age 5 years.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.pfizer.com/

NEW SACRAL NEUROMODULATION DEVICE

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.axonics.com/

CERVICAL SEAL FOR HYSTEROSCOPIC DEVICES

For more information, visit: https://gynsurgicalsolutions.com/product/omni-lok/

UNIVERSAL CYSTOSCOPY SIMPLIFIED

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://cystosure.com/

NEXT FRONTIER IN VACCINE IMMUNIZATION

Globally, there are 410,000 cases of GBS every year. GBS is most common in newborns; women who are carriers of the GBS bacteria may pass it on to their newborns during labor and birth. An estimated 10% to 30% of pregnant women carry the GBS bacteria. The disease can manifest as sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis, with potentially fatal outcomes for some. A maternal vaccine may prevent 231,000 infant and maternal GBS cases, says Pfizer.

According to Pfizer, RSV causes more hospitalizations each year than influenza among young children, with an estimated 33 million cases globally each year in children less than age 5 years.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.pfizer.com/

Can the office visit interval for routine pessary care be extended safely?

Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Timing of office-based pessary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Dec 5. Doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003580.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

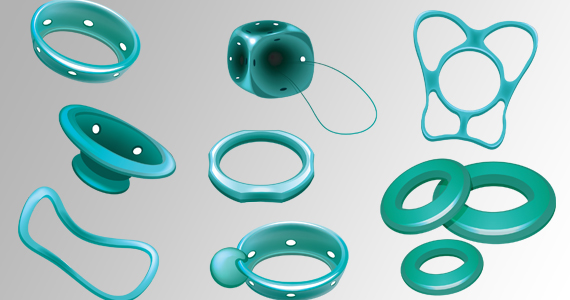

Vaginal pessaries are a common and effective approach for managing pelvic organ prolapse (POP) as well as stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Vaginal mucosal erosions, however, may complicate pessary use. The risk for erosions may be associated with the frequency of pessary change, which involves removing the pessary, washing it, and replacing it in the vagina. Existing data do not address the frequency of pessary change. Recently, however, investigators conducted a randomized noninferiority trial to evaluate the effect of pessary visit intervals on the development of vaginal epithelial abnormalities.

Details of the study

At a single US hospital, Propst and colleagues randomly assigned women who used pessaries for POP, SUI, or both to routine pessary care (offices visits every 12 weeks) or to extended interval pessary care (office visits every 24 weeks). The women used ring, incontinence dish, or Gelhorn pessaries, did not change their pessaries on their own, and had no vaginal mucosal abnormalities.

A total of 130 women were randomly assigned, 64 to the routine care group and 66 to the extended interval care group. The mean age was 79 years and 90% were white, 4.6% were black, and 4% were Hispanic. Approximately 74% of the women used vaginal estrogen.

The primary outcome was the rate of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, including epithelial breaks or erosions. The predetermined noninferiority margin was set at 7.5%.

Results. At the 48-week follow-up, the rate of epithelial erosion was 7.4% in the routine care group and 1.7% in the extended interval care group, thus meeting the prespecified criteria for noninferiority of extended interval pessary care.

Women in each care group reported a similar amount of bothersome vaginal discharge. This was reported on a 5-point scale, with higher numbers indicating greater degree of bother. The mean scores were 1.39 in the routine care group and 1.34 in the extended interval care group. No other pessary-related adverse events occurred in either care group.

Study strengths and limitations

This trial provides good evidence that the timing of office pessary care can be extended to 24 weeks without compromising outcomes. However, since nearly three-quarters of the study participants used vaginal estrogen, the results may not be applicable to pessary users who do not use vaginal estrogen.

Many women change their pessary at home as often as weekly or daily. For women who rely on office visits for pessary care, however, the trial by Propst and colleagues provides good quality evidence that pessaries can be changed as infrequently as every 24 weeks without compromising outcomes. An important limitation of these data is that since most study participants used vaginal estrogen, the findings may not apply to pessary use among women who do not use vaginal estrogen.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD, NCMP

Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Timing of office-based pessary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Dec 5. Doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003580.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Vaginal pessaries are a common and effective approach for managing pelvic organ prolapse (POP) as well as stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Vaginal mucosal erosions, however, may complicate pessary use. The risk for erosions may be associated with the frequency of pessary change, which involves removing the pessary, washing it, and replacing it in the vagina. Existing data do not address the frequency of pessary change. Recently, however, investigators conducted a randomized noninferiority trial to evaluate the effect of pessary visit intervals on the development of vaginal epithelial abnormalities.

Details of the study

At a single US hospital, Propst and colleagues randomly assigned women who used pessaries for POP, SUI, or both to routine pessary care (offices visits every 12 weeks) or to extended interval pessary care (office visits every 24 weeks). The women used ring, incontinence dish, or Gelhorn pessaries, did not change their pessaries on their own, and had no vaginal mucosal abnormalities.

A total of 130 women were randomly assigned, 64 to the routine care group and 66 to the extended interval care group. The mean age was 79 years and 90% were white, 4.6% were black, and 4% were Hispanic. Approximately 74% of the women used vaginal estrogen.

The primary outcome was the rate of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, including epithelial breaks or erosions. The predetermined noninferiority margin was set at 7.5%.

Results. At the 48-week follow-up, the rate of epithelial erosion was 7.4% in the routine care group and 1.7% in the extended interval care group, thus meeting the prespecified criteria for noninferiority of extended interval pessary care.

Women in each care group reported a similar amount of bothersome vaginal discharge. This was reported on a 5-point scale, with higher numbers indicating greater degree of bother. The mean scores were 1.39 in the routine care group and 1.34 in the extended interval care group. No other pessary-related adverse events occurred in either care group.

Study strengths and limitations

This trial provides good evidence that the timing of office pessary care can be extended to 24 weeks without compromising outcomes. However, since nearly three-quarters of the study participants used vaginal estrogen, the results may not be applicable to pessary users who do not use vaginal estrogen.

Many women change their pessary at home as often as weekly or daily. For women who rely on office visits for pessary care, however, the trial by Propst and colleagues provides good quality evidence that pessaries can be changed as infrequently as every 24 weeks without compromising outcomes. An important limitation of these data is that since most study participants used vaginal estrogen, the findings may not apply to pessary use among women who do not use vaginal estrogen.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD, NCMP

Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Timing of office-based pessary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Dec 5. Doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003580.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Vaginal pessaries are a common and effective approach for managing pelvic organ prolapse (POP) as well as stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Vaginal mucosal erosions, however, may complicate pessary use. The risk for erosions may be associated with the frequency of pessary change, which involves removing the pessary, washing it, and replacing it in the vagina. Existing data do not address the frequency of pessary change. Recently, however, investigators conducted a randomized noninferiority trial to evaluate the effect of pessary visit intervals on the development of vaginal epithelial abnormalities.

Details of the study

At a single US hospital, Propst and colleagues randomly assigned women who used pessaries for POP, SUI, or both to routine pessary care (offices visits every 12 weeks) or to extended interval pessary care (office visits every 24 weeks). The women used ring, incontinence dish, or Gelhorn pessaries, did not change their pessaries on their own, and had no vaginal mucosal abnormalities.

A total of 130 women were randomly assigned, 64 to the routine care group and 66 to the extended interval care group. The mean age was 79 years and 90% were white, 4.6% were black, and 4% were Hispanic. Approximately 74% of the women used vaginal estrogen.

The primary outcome was the rate of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, including epithelial breaks or erosions. The predetermined noninferiority margin was set at 7.5%.

Results. At the 48-week follow-up, the rate of epithelial erosion was 7.4% in the routine care group and 1.7% in the extended interval care group, thus meeting the prespecified criteria for noninferiority of extended interval pessary care.

Women in each care group reported a similar amount of bothersome vaginal discharge. This was reported on a 5-point scale, with higher numbers indicating greater degree of bother. The mean scores were 1.39 in the routine care group and 1.34 in the extended interval care group. No other pessary-related adverse events occurred in either care group.

Study strengths and limitations

This trial provides good evidence that the timing of office pessary care can be extended to 24 weeks without compromising outcomes. However, since nearly three-quarters of the study participants used vaginal estrogen, the results may not be applicable to pessary users who do not use vaginal estrogen.

Many women change their pessary at home as often as weekly or daily. For women who rely on office visits for pessary care, however, the trial by Propst and colleagues provides good quality evidence that pessaries can be changed as infrequently as every 24 weeks without compromising outcomes. An important limitation of these data is that since most study participants used vaginal estrogen, the findings may not apply to pessary use among women who do not use vaginal estrogen.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD, NCMP

Medical management of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-age women

Case 1 Multiparous woman presents with heavy regular menses

Over the past several years, a 34-year-old woman has noted increasing intensity and duration of menstrual flow, which now persists for 8 days and includes clots “the size of quarters” and soaks a pad within 1 hour. Sometimes she misses or leaves work on her heaviest days of flow. She reports that menstrual cramps prior to and during flow are increasingly bothersome and do not respond adequately to ibuprofen. She intermittently uses condoms for contraception. She does not wish to be pregnant currently; however, she recently entered into a new relationship and may wish to conceive in the future.

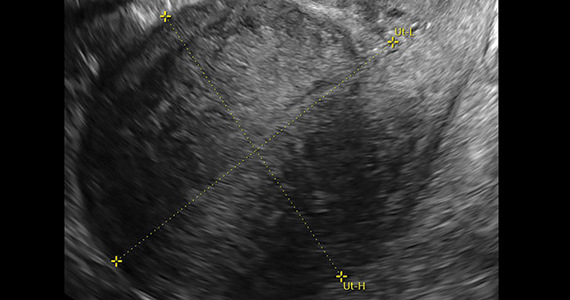

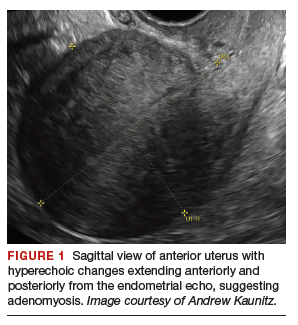

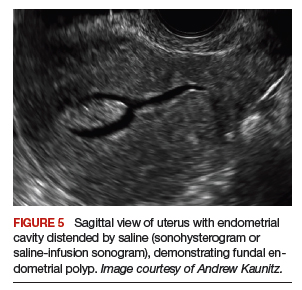

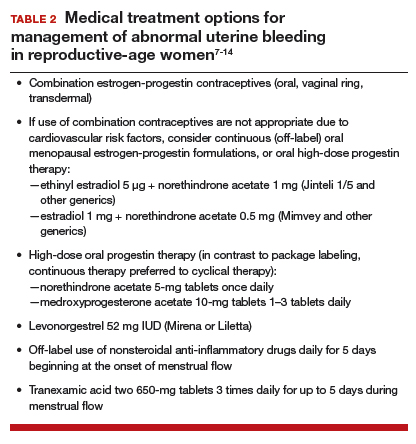

On bimanual examination, the uterus appears bulky. Her hemoglobin is 10.9 g/dL with low mean corpuscular volume and a serum ferritin level indicating iron depletion. Pelvic ultrasonography suggests uterine adenomyosis; no fibroids are imaged (FIGURE 1).

You advise the patient to take ferrous sulfate 325 mg every other day. After discussion with the patient regarding different treatment options, she chooses to proceed with placement of a 52-mg levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD; Mirena or Liletta).

Case 2 Older adolescent presents with irregular bleeding

A 19-year-old patient reports approximately 6 bleeding episodes each year. She reports the duration of her bleeding as variable, and sometimes the bleeding is heavy with small clots passed. She has been previously diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives have been prescribed several times in the past, but she always has discontinued them due to nausea. The patient is in a same-sex relationship and does not anticipate being sexually active with a male. She reports having to shave her mustache and chin twice weekly for the past 1 to 2 years.

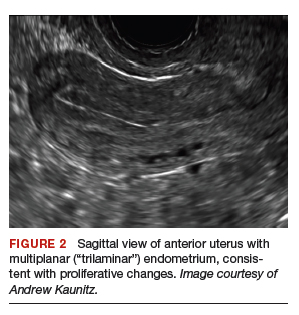

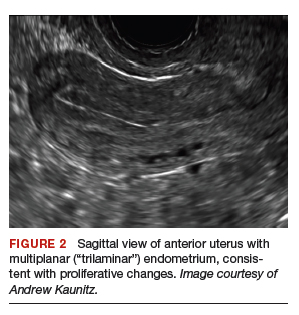

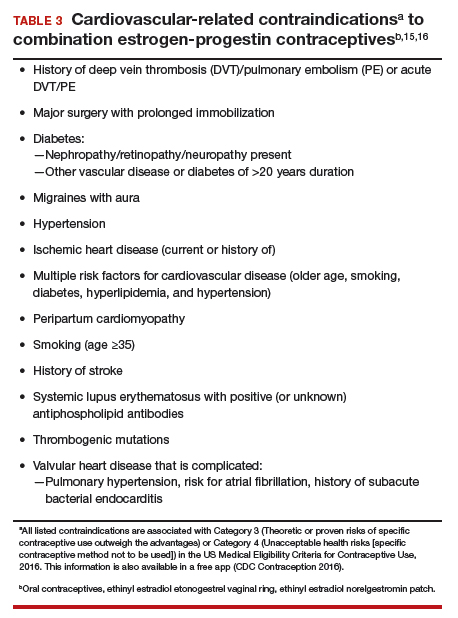

On physical examination, the patient is obese (body mass index [BMI], 32 kg/m2), facial acne and hirsutism are present, and hair extends from the mons toward the umbilicus. Bimanual examination reveals a normal size, mobile, nontender uterus without obvious adnexal pathology. Pelvic ultrasonography demonstrates a normal-appearing uterus with multiplanar endometrium (consistent with proliferative changes) (FIGURE 2). Ovarian imaging demonstrates ≥12 follicles per image (FIGURE 3).

After reviewing various treatment options, you prescribe oral medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg (two 10-mg tablets) daily in a continuous fashion. You counsel her that she should not be surprised or concerned if frequent or even continuous bleeding occurs initially, and that she should continue this medication despite the occurrence of such.

About one-third of all women experience abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) sometime during their lifetime and AUB can impair quality of life.1 Surgical management, including hysterectomy and endometrial ablation, plays an important role in the management of AUB in patients who do not desire future pregnancies. However, many cases of AUB occur in women who may not have completed childbearing or in women who prefer to avoid surgery.2 AUB can be managed effectively medically in most cases.1 Accordingly, in this review, we focus on nonsurgical management of AUB.

Continue to: Because previously used terms, including...

Because previously used terms, including menorrhagia and meno-metrorrhagia, were inconsistently defined and confusing, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics introduced updated terminology in 2011 to better describe and characterize AUB in nonpregnant women. Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) refers to ovulatory (cyclic) bleeding that is more than 8 days’ duration, or sufficiently heavy to impair a woman’s quality of life. HMB is a pattern of AUB distinct from the irregular bleeding pattern typically caused by ovulatory dysfunction (AUB-O).1

Clinical evaluation

Obtain menstrual history. In addition to a medical, surgical, and gynecologic history, a thorough menstrual history should be obtained to further characterize the patient’s bleeding pattern. In contrast to the cyclical or ovulatory bleeding seen with HMB, bleeding associated with inconsistent ovulation (AUB-O) is unpredictable or irregular, and is commonly associated with PCOS. AUB-O is also encountered in recently menarchal girls (secondary to immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis) and in those who are perimenopausal. In addition, medications that can induce hyperprolactinemia (such as certain antipsychotics) can cause AUB-O.

Evaluate for all sources of bleeding. Be sure to evaluate for extrauterine causes of bleeding, including the cervix, vagina, vulva, or the urinary or gastrointestinal tracts for bleeding. Intermenstrual bleeding occurring between normal regular menses may be caused by an endometrial polyp, submucosal fibroid, endometritis, or an IUD. The patient report of postcoital bleeding suggests that cervical disease (cervicitis, polyp, or malignancy) may be present. Uterine leiomyoma or adenomyosis represent common causes of HMB. However, HMB also may be caused by a copper IUD, coagulation disorders (including von Willebrand disease), or use of anticoagulant medications. Hormonal contraceptives also can cause irregular bleeding.

Perform a pelvic examination and measure vital signs. The presence of fever suggests the possible presence of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), while orthostatic hypotension raises the possibility of hypovolemia. When vaginal speculum examination is performed, a cervical cause of abnormal bleeding may be noted. The presence of fresh or old blood or finding clots in the vaginal vault or at the cervical os are all consistent with AUB. A bimanual examination that reveals an enlarged or lobular uterus suggests leiomyoma or adenomyosis. Cervical or adnexal tenderness is often noted in women with PID, which itself may be associated with endometritis. The presence of hyperandrogenic signs on physical examination (eg, acne, hirsutism, or clitoromegaly) suggests PCOS. The finding of galactorrhea suggests that hyperprolactinemia may be present.

Laboratory assessment

Test for pregnancy, cervical disease, and sexually transmitted infection when appropriate. Pregnancy testing is appropriate for women with AUB aged 55 years or younger. If patients with AUB are not up to date with normal cervical cancer screening results, cervical cytology and/or human papillomavirus testing should be performed. Testing for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis should be performed in patients:

- younger than 25 years

- when the history indicates new or multiple sexual partners, or

- when vaginal discharge, cervicitis, cervical motion, or adnexal tenderness is present.

Continue to: Obtain a complete blood count and serum ferritin levels...

Obtain a complete blood count and serum ferritin levels. In women presenting with HMB, iron depletion and iron deficiency anemia are common. The finding of leukocytosis raises the possibility of PID or postpartum endometritis. In women with presumptive AUB-O, checking the levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, free T4, and prolactin should be performed.

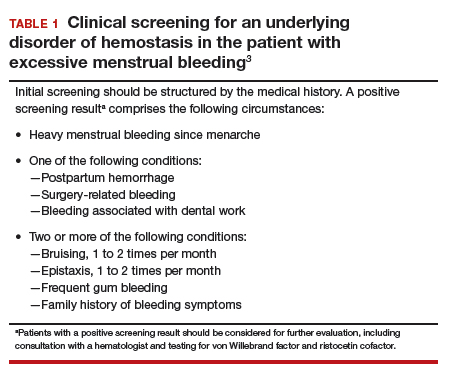

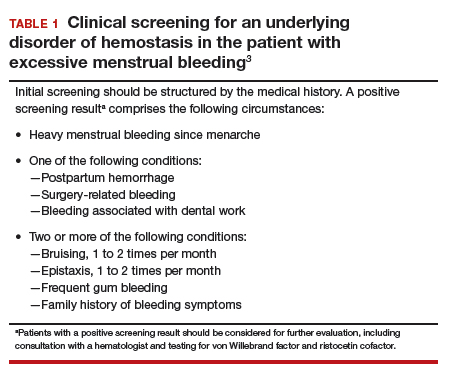

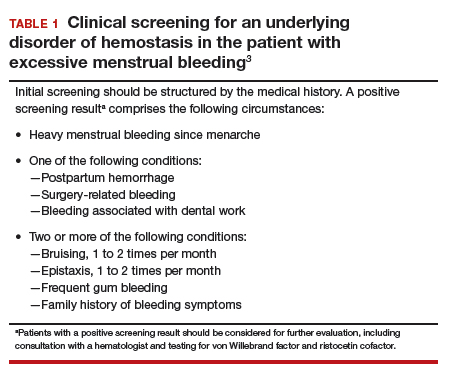

Screen for a hemostasis disorder. Women with excessive menstrual bleeding should be clinically screened for an underlying disorder of hemostasis (TABLE 1).3 When a hemostasis disorder is suspected, initial laboratory evaluation includes a partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen. Women who have a positive clinical screen for a possible bleeding disorder or abnormal initial laboratory test results for disorders of hemostasis should undergo further laboratory evaluation, including von Willebrand factor antigen, ristocetin cofactor assay, and factor VIII. Consultation with a hematologist should be considered in these cases.

Perform endometrial biopsy when indicated

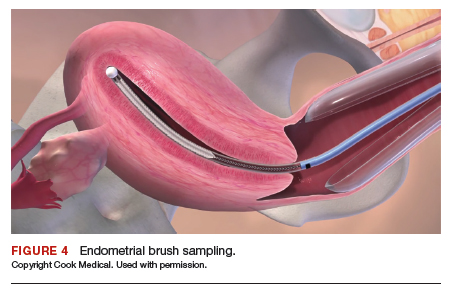

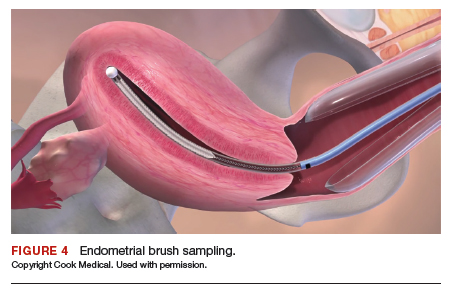

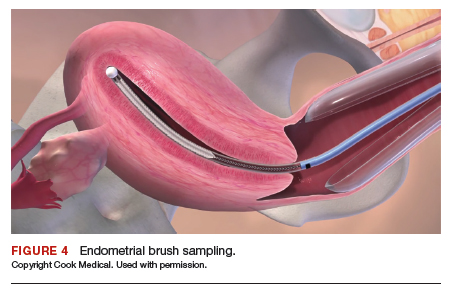

After excluding pregnancy, endometrial biopsy (through pipelle biospy or brush sampling; FIGURE 4) should be performed in women with AUB who are at increased risk for endometrial neoplasia. The prevalence of endometrial neoplasia is substantially higher among women ≥45 years of age4 and among patients with AUB who are also obese (BMI, ≥30 kg/m2).5 In addition, AUB patients with unopposed estrogen exposure (presumed anovulation/PCOS), as well as those with persistent AUB or failed medical management, should undergo endometrial biopsy.6

Utilize transvaginal ultrasonography

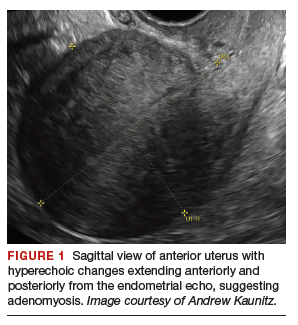

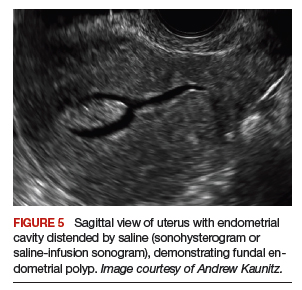

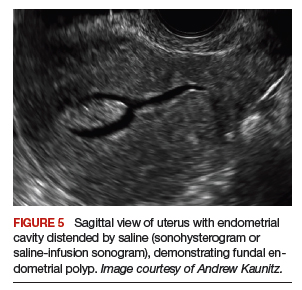

Transvaginal ultrasonography is often useful in the evaluation of patients with AUB, as it may identify uterine fibroids or adenomyosis, suggest intracavitary pathology (such as an endometrial polyp or submucosal fibroid), or raise the possibility of PCOS. In virginal patients or those in whom vaginal ultrasound is not appropriate, abdominal pelvic ultrasonography represents appropriate imaging. If unenhanced ultrasound suggests endometrial polyps or fibroids within the endometrial cavity, an office-based saline infusion sonogram (sonohysterogram) (FIGURE 5) or hysteroscopy should be performed. Targeted endometrial sampling and biopsy of intracavitary pathology can be performed at the time of hysteroscopy.

Treatment

When HMB impairs quality of life, is bothersome to the patient, or results in anemia, treatment is appropriate. Although bleeding episodes in women with AUB-O may be infrequent (as with Case 2), treatment prevents heavy or prolonged bleeding episodes as well as endometrial neoplasia that may otherwise occur in anovulatory women.

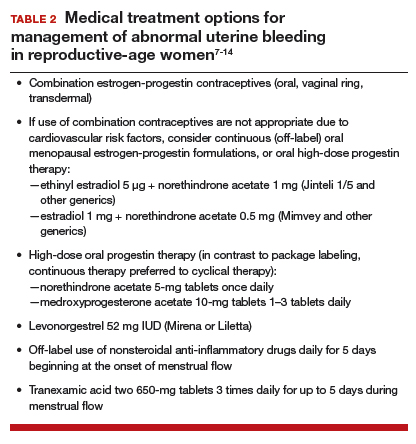

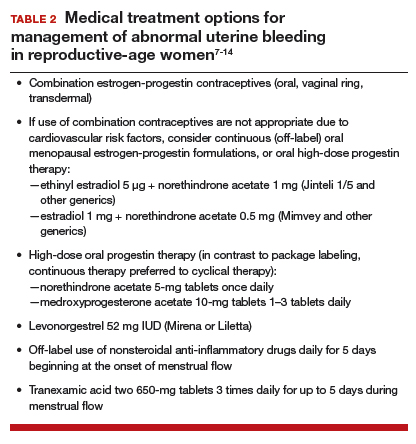

Many women with AUB can be managed medically. However, treatment choices will vary with respect to the patient’s desire for future fertility, medical comorbidities, personal preferences, and financial barriers. While many women may prefer outpatient medical management (TABLE 2),7-14 others might desire surgical therapy, including endometrial ablation or hysterectomy.

Oral contraceptives

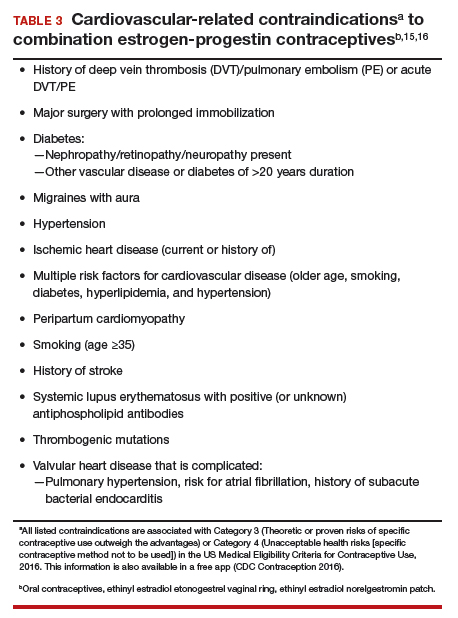

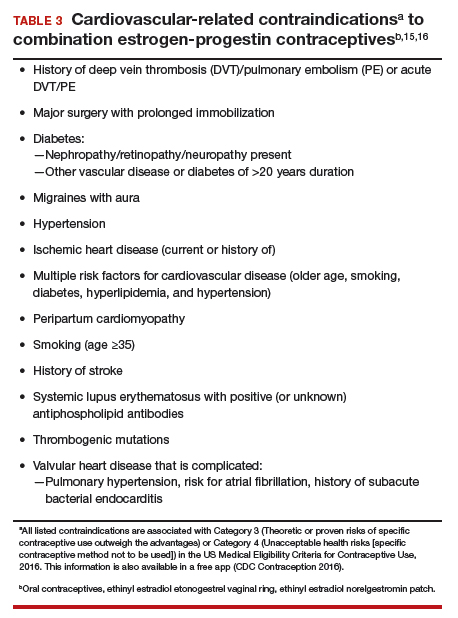

Combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives represent appropriate initial therapy for many women in the reproductive-age group with AUB, whether women have HMB or AUB-O. However, contraceptive doses of estrogen are not appropriate for some women with risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including those who smoke cigarettes and are age ≥35 years or those who have hypertension (TABLE 3).15,16

Continue to: Menopausal dosages of HT...

Menopausal dosages of HT

If use of contraceptive doses of estrogen is not appropriate, continuous off-label use of menopausal combination formulations (physiologic dosage) of hormonal therapy (HT; ie, lower doses of estrogen than contraceptives) may be effective in reducing or eliminating AUB. Options for menopausal combination formulations include generic ethinyl estradiol 5 µg/norethindrone acetate 1 mg or estradiol 1 mg/norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg.7 High-dose oral progestin therapy (norethindrone acetate 5 mg tablet once daily or medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg tablets 1–3 times daily) also can be used when combination contraceptives are contraindicated and may be more effective than lower-dose combination formulations.

Package labeling, as well as some guidelines, indicate that oral progestins used to treat AUB should be taken cyclically.8 However, continuous daily use is easier for many patients and may be more effective in reducing bleeding. Accordingly, we counsel patients with AUB who are using progestins and who do not wish to conceive to take these medications continuously. High-dose oral progestin therapy may cause bloating, dysphoria, and increased appetite/weight gain. Women initiating hormonal management (including the progestin IUDs detailed below) for AUB should be counseled that irregular or even continuous light bleeding/spotting is common initially, but this bleeding pattern typically decreases with continued use.

IUDs

The LNG 52 mg IUD (Mirena or Liletta) effectively treats HMB, reducing bleeding in a manner comparable to that of endometrial ablation.9,10 The Mirena IUD is approved for treatment of HMB in women desiring intrauterine contraception. In contrast to oral medications, use of progestin IUDs does not involve daily administration and may represent an attractive option for women with HMB who would like to avoid surgery or preserve fertility. With ongoing use, continuous oral or intrauterine hormonal management may result in amenorrhea in some women with AUB.

When the LNG 52 mg IUD is used to treat HMB, the menstrual suppression impact may begin to attenuate after approximately 4 years of use; in this setting, replacing the IUD often restores effective menstrual suppression.11 The LNG 52 mg IUD effectively suppresses menses in women with coagulation disorders; if menstrual suppression with the progestin IUD is not adequate in this setting, it may be appropriate to add an oral combination estrogen-progestin contraceptive or high-dose oral progestin.11,12

NSAIDs and tranexamic acid

Off-label use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (naproxen 500–1,000 mg daily for 5 days beginning at the onset of menstrual flow or tranexamic acid two 650-mg tablets 3 times daily for up to 5 days during episodes of heavy flow) can suppress HMB and is useful for women who prefer to avoid or have contraindications to hormonal treatments.13,14 Unfortunately, these agents are not as effective as hormonal management in treating AUB.

Iron supplementation is often needed

Iron depletion commonly results from HMB, often resulting in iron deficiency anemia. When iron depletion (readily identified by checking a serum ferritin level) or iron deficiency anemia is identified, iron supplementation should be recommended. Every-other-day administration of iron supplements maximizes iron absorption while minimizing the adverse effects of unabsorbed iron, such as nausea. Sixty mg of elemental iron (ferrous sulfate 325 mg) administered every other day represents an inexpensive and effective treatment for iron deficiency/anemia.17 In patients who cannot tolerate oral iron supplementation or for those in whom oral therapy is not appropriate or effective, newer intravenous iron formulations are safe and effective.18

Continue to: Case 1 Follow-up...

Case 1 Follow-up

The patient noted marked improvement in her menstrual cramps following LNG-containing IUD placement. Although she also reported that she no longer experienced heavy menstrual flow or cramps, she was bothered by frequent, unpredictable light bleeding/spotting. You prescribed norethindrone acetate (NETA) 5-mg tablet orally once daily, to be used in addition to her IUD. After using the IUD with concomitant NETA for 2 months’ duration, she noted that her bleeding/spotting almost completely resolved; however, she did report feeling irritable with use of the progestin tablets. She subsequently stopped the NETA tablets and, after 6 months of additional follow-up, reported only minimal spotting and no cramps.

At this later follow-up visit, you noted that her hemoglobin level increased to 12.6 g/dL, and the ferritin level no longer indicated iron depletion. After the IUD had been in place for 4 years, she reported that she was beginning to experience frequent light bleeding again. A follow-up vaginal sonogram noted a well-positioned IUD, there was no suggestion of intracavitary pathology, and adenomyosis continued to be imaged. She underwent IUD removal and placement of a new LNG 52 mg IUD. This resulted in marked reduction in her bleeding.

Case 2 Follow-up

Two weeks after beginning continuous oral progestin therapy, the patient called reporting frequent irregular bleeding. She was reassured that this was not unexpected and encouraged to continue oral progestin therapy. During a 3-month follow-up visit, the patient noted little, if any, bleeding over the previous 2 months and was pleased with this result. She continued to note acne and hirsutism and asked about the possibility of adding spironolactone to her oral progestin regimen.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS; FIGO Menstrual Disorders Committee. The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:393-408.

- Kaunitz AM. Abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-age women. JAMA. 2019;321:2126-2127.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:891-896.

- National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Uterine Cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/corp.html. Accessed October 10, 2019.

- Wise MR, Gill P, Lensen S, et al. Body mass index trumps age in decision for endometrial biopsy: cohort study of symptomatic premenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:598.e1-598.e8.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

- The North American Menopause Society. Menopause Practice–A Clinician’s Guide. 5th ed. NAMS: Mayfield Heights, OH; 2014.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88. Accessed October 10, 2019.

- Kaunitz AM, Bissonnette F, Monteiro I, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or medroxyprogesterone for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:625-632.

- Kaunitz AM, Meredith S, Inki P, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and endometrial ablation in heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1104-1116.

- Kaunitz AM, Inki P. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in heavy menstrual bleeding: a benefit-risk review. Drugs. 2012;72:193-215.

- James AH, Kouides PA, Abdul-Kadir R, et al. Von Willebrand disease and other bleeding disorders in women: consensus on diagnosis and management from an international expert panel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:12.e1-8.

- Ylikorkala O, Pekonen F. Naproxen reduces idiopathic but not fibromyoma-induced menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68:10-12.

- Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:865-875.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–103.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin no. 206: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e128-e150.

- Stoffel NU, Cercamondi CI, Brittenham G, et al. Iron absorption from oral iron supplements given on consecutive versus alternate days and as single morning doses versus twice-daily split dosing in iron-depleted women: two open-label, randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e524–e533.

- Auerbach M, Adamson JW. How we diagnose and treat iron deficiency anemia. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:31-38.

Case 1 Multiparous woman presents with heavy regular menses

Over the past several years, a 34-year-old woman has noted increasing intensity and duration of menstrual flow, which now persists for 8 days and includes clots “the size of quarters” and soaks a pad within 1 hour. Sometimes she misses or leaves work on her heaviest days of flow. She reports that menstrual cramps prior to and during flow are increasingly bothersome and do not respond adequately to ibuprofen. She intermittently uses condoms for contraception. She does not wish to be pregnant currently; however, she recently entered into a new relationship and may wish to conceive in the future.

On bimanual examination, the uterus appears bulky. Her hemoglobin is 10.9 g/dL with low mean corpuscular volume and a serum ferritin level indicating iron depletion. Pelvic ultrasonography suggests uterine adenomyosis; no fibroids are imaged (FIGURE 1).

You advise the patient to take ferrous sulfate 325 mg every other day. After discussion with the patient regarding different treatment options, she chooses to proceed with placement of a 52-mg levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD; Mirena or Liletta).

Case 2 Older adolescent presents with irregular bleeding

A 19-year-old patient reports approximately 6 bleeding episodes each year. She reports the duration of her bleeding as variable, and sometimes the bleeding is heavy with small clots passed. She has been previously diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives have been prescribed several times in the past, but she always has discontinued them due to nausea. The patient is in a same-sex relationship and does not anticipate being sexually active with a male. She reports having to shave her mustache and chin twice weekly for the past 1 to 2 years.

On physical examination, the patient is obese (body mass index [BMI], 32 kg/m2), facial acne and hirsutism are present, and hair extends from the mons toward the umbilicus. Bimanual examination reveals a normal size, mobile, nontender uterus without obvious adnexal pathology. Pelvic ultrasonography demonstrates a normal-appearing uterus with multiplanar endometrium (consistent with proliferative changes) (FIGURE 2). Ovarian imaging demonstrates ≥12 follicles per image (FIGURE 3).

After reviewing various treatment options, you prescribe oral medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg (two 10-mg tablets) daily in a continuous fashion. You counsel her that she should not be surprised or concerned if frequent or even continuous bleeding occurs initially, and that she should continue this medication despite the occurrence of such.

About one-third of all women experience abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) sometime during their lifetime and AUB can impair quality of life.1 Surgical management, including hysterectomy and endometrial ablation, plays an important role in the management of AUB in patients who do not desire future pregnancies. However, many cases of AUB occur in women who may not have completed childbearing or in women who prefer to avoid surgery.2 AUB can be managed effectively medically in most cases.1 Accordingly, in this review, we focus on nonsurgical management of AUB.

Continue to: Because previously used terms, including...

Because previously used terms, including menorrhagia and meno-metrorrhagia, were inconsistently defined and confusing, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics introduced updated terminology in 2011 to better describe and characterize AUB in nonpregnant women. Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) refers to ovulatory (cyclic) bleeding that is more than 8 days’ duration, or sufficiently heavy to impair a woman’s quality of life. HMB is a pattern of AUB distinct from the irregular bleeding pattern typically caused by ovulatory dysfunction (AUB-O).1

Clinical evaluation

Obtain menstrual history. In addition to a medical, surgical, and gynecologic history, a thorough menstrual history should be obtained to further characterize the patient’s bleeding pattern. In contrast to the cyclical or ovulatory bleeding seen with HMB, bleeding associated with inconsistent ovulation (AUB-O) is unpredictable or irregular, and is commonly associated with PCOS. AUB-O is also encountered in recently menarchal girls (secondary to immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis) and in those who are perimenopausal. In addition, medications that can induce hyperprolactinemia (such as certain antipsychotics) can cause AUB-O.

Evaluate for all sources of bleeding. Be sure to evaluate for extrauterine causes of bleeding, including the cervix, vagina, vulva, or the urinary or gastrointestinal tracts for bleeding. Intermenstrual bleeding occurring between normal regular menses may be caused by an endometrial polyp, submucosal fibroid, endometritis, or an IUD. The patient report of postcoital bleeding suggests that cervical disease (cervicitis, polyp, or malignancy) may be present. Uterine leiomyoma or adenomyosis represent common causes of HMB. However, HMB also may be caused by a copper IUD, coagulation disorders (including von Willebrand disease), or use of anticoagulant medications. Hormonal contraceptives also can cause irregular bleeding.

Perform a pelvic examination and measure vital signs. The presence of fever suggests the possible presence of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), while orthostatic hypotension raises the possibility of hypovolemia. When vaginal speculum examination is performed, a cervical cause of abnormal bleeding may be noted. The presence of fresh or old blood or finding clots in the vaginal vault or at the cervical os are all consistent with AUB. A bimanual examination that reveals an enlarged or lobular uterus suggests leiomyoma or adenomyosis. Cervical or adnexal tenderness is often noted in women with PID, which itself may be associated with endometritis. The presence of hyperandrogenic signs on physical examination (eg, acne, hirsutism, or clitoromegaly) suggests PCOS. The finding of galactorrhea suggests that hyperprolactinemia may be present.

Laboratory assessment

Test for pregnancy, cervical disease, and sexually transmitted infection when appropriate. Pregnancy testing is appropriate for women with AUB aged 55 years or younger. If patients with AUB are not up to date with normal cervical cancer screening results, cervical cytology and/or human papillomavirus testing should be performed. Testing for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis should be performed in patients:

- younger than 25 years

- when the history indicates new or multiple sexual partners, or

- when vaginal discharge, cervicitis, cervical motion, or adnexal tenderness is present.

Continue to: Obtain a complete blood count and serum ferritin levels...

Obtain a complete blood count and serum ferritin levels. In women presenting with HMB, iron depletion and iron deficiency anemia are common. The finding of leukocytosis raises the possibility of PID or postpartum endometritis. In women with presumptive AUB-O, checking the levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, free T4, and prolactin should be performed.

Screen for a hemostasis disorder. Women with excessive menstrual bleeding should be clinically screened for an underlying disorder of hemostasis (TABLE 1).3 When a hemostasis disorder is suspected, initial laboratory evaluation includes a partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen. Women who have a positive clinical screen for a possible bleeding disorder or abnormal initial laboratory test results for disorders of hemostasis should undergo further laboratory evaluation, including von Willebrand factor antigen, ristocetin cofactor assay, and factor VIII. Consultation with a hematologist should be considered in these cases.

Perform endometrial biopsy when indicated

After excluding pregnancy, endometrial biopsy (through pipelle biospy or brush sampling; FIGURE 4) should be performed in women with AUB who are at increased risk for endometrial neoplasia. The prevalence of endometrial neoplasia is substantially higher among women ≥45 years of age4 and among patients with AUB who are also obese (BMI, ≥30 kg/m2).5 In addition, AUB patients with unopposed estrogen exposure (presumed anovulation/PCOS), as well as those with persistent AUB or failed medical management, should undergo endometrial biopsy.6

Utilize transvaginal ultrasonography

Transvaginal ultrasonography is often useful in the evaluation of patients with AUB, as it may identify uterine fibroids or adenomyosis, suggest intracavitary pathology (such as an endometrial polyp or submucosal fibroid), or raise the possibility of PCOS. In virginal patients or those in whom vaginal ultrasound is not appropriate, abdominal pelvic ultrasonography represents appropriate imaging. If unenhanced ultrasound suggests endometrial polyps or fibroids within the endometrial cavity, an office-based saline infusion sonogram (sonohysterogram) (FIGURE 5) or hysteroscopy should be performed. Targeted endometrial sampling and biopsy of intracavitary pathology can be performed at the time of hysteroscopy.

Treatment

When HMB impairs quality of life, is bothersome to the patient, or results in anemia, treatment is appropriate. Although bleeding episodes in women with AUB-O may be infrequent (as with Case 2), treatment prevents heavy or prolonged bleeding episodes as well as endometrial neoplasia that may otherwise occur in anovulatory women.

Many women with AUB can be managed medically. However, treatment choices will vary with respect to the patient’s desire for future fertility, medical comorbidities, personal preferences, and financial barriers. While many women may prefer outpatient medical management (TABLE 2),7-14 others might desire surgical therapy, including endometrial ablation or hysterectomy.

Oral contraceptives

Combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives represent appropriate initial therapy for many women in the reproductive-age group with AUB, whether women have HMB or AUB-O. However, contraceptive doses of estrogen are not appropriate for some women with risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including those who smoke cigarettes and are age ≥35 years or those who have hypertension (TABLE 3).15,16

Continue to: Menopausal dosages of HT...

Menopausal dosages of HT

If use of contraceptive doses of estrogen is not appropriate, continuous off-label use of menopausal combination formulations (physiologic dosage) of hormonal therapy (HT; ie, lower doses of estrogen than contraceptives) may be effective in reducing or eliminating AUB. Options for menopausal combination formulations include generic ethinyl estradiol 5 µg/norethindrone acetate 1 mg or estradiol 1 mg/norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg.7 High-dose oral progestin therapy (norethindrone acetate 5 mg tablet once daily or medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg tablets 1–3 times daily) also can be used when combination contraceptives are contraindicated and may be more effective than lower-dose combination formulations.

Package labeling, as well as some guidelines, indicate that oral progestins used to treat AUB should be taken cyclically.8 However, continuous daily use is easier for many patients and may be more effective in reducing bleeding. Accordingly, we counsel patients with AUB who are using progestins and who do not wish to conceive to take these medications continuously. High-dose oral progestin therapy may cause bloating, dysphoria, and increased appetite/weight gain. Women initiating hormonal management (including the progestin IUDs detailed below) for AUB should be counseled that irregular or even continuous light bleeding/spotting is common initially, but this bleeding pattern typically decreases with continued use.

IUDs

The LNG 52 mg IUD (Mirena or Liletta) effectively treats HMB, reducing bleeding in a manner comparable to that of endometrial ablation.9,10 The Mirena IUD is approved for treatment of HMB in women desiring intrauterine contraception. In contrast to oral medications, use of progestin IUDs does not involve daily administration and may represent an attractive option for women with HMB who would like to avoid surgery or preserve fertility. With ongoing use, continuous oral or intrauterine hormonal management may result in amenorrhea in some women with AUB.

When the LNG 52 mg IUD is used to treat HMB, the menstrual suppression impact may begin to attenuate after approximately 4 years of use; in this setting, replacing the IUD often restores effective menstrual suppression.11 The LNG 52 mg IUD effectively suppresses menses in women with coagulation disorders; if menstrual suppression with the progestin IUD is not adequate in this setting, it may be appropriate to add an oral combination estrogen-progestin contraceptive or high-dose oral progestin.11,12

NSAIDs and tranexamic acid

Off-label use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (naproxen 500–1,000 mg daily for 5 days beginning at the onset of menstrual flow or tranexamic acid two 650-mg tablets 3 times daily for up to 5 days during episodes of heavy flow) can suppress HMB and is useful for women who prefer to avoid or have contraindications to hormonal treatments.13,14 Unfortunately, these agents are not as effective as hormonal management in treating AUB.

Iron supplementation is often needed

Iron depletion commonly results from HMB, often resulting in iron deficiency anemia. When iron depletion (readily identified by checking a serum ferritin level) or iron deficiency anemia is identified, iron supplementation should be recommended. Every-other-day administration of iron supplements maximizes iron absorption while minimizing the adverse effects of unabsorbed iron, such as nausea. Sixty mg of elemental iron (ferrous sulfate 325 mg) administered every other day represents an inexpensive and effective treatment for iron deficiency/anemia.17 In patients who cannot tolerate oral iron supplementation or for those in whom oral therapy is not appropriate or effective, newer intravenous iron formulations are safe and effective.18

Continue to: Case 1 Follow-up...

Case 1 Follow-up

The patient noted marked improvement in her menstrual cramps following LNG-containing IUD placement. Although she also reported that she no longer experienced heavy menstrual flow or cramps, she was bothered by frequent, unpredictable light bleeding/spotting. You prescribed norethindrone acetate (NETA) 5-mg tablet orally once daily, to be used in addition to her IUD. After using the IUD with concomitant NETA for 2 months’ duration, she noted that her bleeding/spotting almost completely resolved; however, she did report feeling irritable with use of the progestin tablets. She subsequently stopped the NETA tablets and, after 6 months of additional follow-up, reported only minimal spotting and no cramps.

At this later follow-up visit, you noted that her hemoglobin level increased to 12.6 g/dL, and the ferritin level no longer indicated iron depletion. After the IUD had been in place for 4 years, she reported that she was beginning to experience frequent light bleeding again. A follow-up vaginal sonogram noted a well-positioned IUD, there was no suggestion of intracavitary pathology, and adenomyosis continued to be imaged. She underwent IUD removal and placement of a new LNG 52 mg IUD. This resulted in marked reduction in her bleeding.

Case 2 Follow-up

Two weeks after beginning continuous oral progestin therapy, the patient called reporting frequent irregular bleeding. She was reassured that this was not unexpected and encouraged to continue oral progestin therapy. During a 3-month follow-up visit, the patient noted little, if any, bleeding over the previous 2 months and was pleased with this result. She continued to note acne and hirsutism and asked about the possibility of adding spironolactone to her oral progestin regimen.

Case 1 Multiparous woman presents with heavy regular menses

Over the past several years, a 34-year-old woman has noted increasing intensity and duration of menstrual flow, which now persists for 8 days and includes clots “the size of quarters” and soaks a pad within 1 hour. Sometimes she misses or leaves work on her heaviest days of flow. She reports that menstrual cramps prior to and during flow are increasingly bothersome and do not respond adequately to ibuprofen. She intermittently uses condoms for contraception. She does not wish to be pregnant currently; however, she recently entered into a new relationship and may wish to conceive in the future.

On bimanual examination, the uterus appears bulky. Her hemoglobin is 10.9 g/dL with low mean corpuscular volume and a serum ferritin level indicating iron depletion. Pelvic ultrasonography suggests uterine adenomyosis; no fibroids are imaged (FIGURE 1).

You advise the patient to take ferrous sulfate 325 mg every other day. After discussion with the patient regarding different treatment options, she chooses to proceed with placement of a 52-mg levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD; Mirena or Liletta).

Case 2 Older adolescent presents with irregular bleeding

A 19-year-old patient reports approximately 6 bleeding episodes each year. She reports the duration of her bleeding as variable, and sometimes the bleeding is heavy with small clots passed. She has been previously diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives have been prescribed several times in the past, but she always has discontinued them due to nausea. The patient is in a same-sex relationship and does not anticipate being sexually active with a male. She reports having to shave her mustache and chin twice weekly for the past 1 to 2 years.

On physical examination, the patient is obese (body mass index [BMI], 32 kg/m2), facial acne and hirsutism are present, and hair extends from the mons toward the umbilicus. Bimanual examination reveals a normal size, mobile, nontender uterus without obvious adnexal pathology. Pelvic ultrasonography demonstrates a normal-appearing uterus with multiplanar endometrium (consistent with proliferative changes) (FIGURE 2). Ovarian imaging demonstrates ≥12 follicles per image (FIGURE 3).

After reviewing various treatment options, you prescribe oral medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg (two 10-mg tablets) daily in a continuous fashion. You counsel her that she should not be surprised or concerned if frequent or even continuous bleeding occurs initially, and that she should continue this medication despite the occurrence of such.

About one-third of all women experience abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) sometime during their lifetime and AUB can impair quality of life.1 Surgical management, including hysterectomy and endometrial ablation, plays an important role in the management of AUB in patients who do not desire future pregnancies. However, many cases of AUB occur in women who may not have completed childbearing or in women who prefer to avoid surgery.2 AUB can be managed effectively medically in most cases.1 Accordingly, in this review, we focus on nonsurgical management of AUB.

Continue to: Because previously used terms, including...

Because previously used terms, including menorrhagia and meno-metrorrhagia, were inconsistently defined and confusing, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics introduced updated terminology in 2011 to better describe and characterize AUB in nonpregnant women. Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) refers to ovulatory (cyclic) bleeding that is more than 8 days’ duration, or sufficiently heavy to impair a woman’s quality of life. HMB is a pattern of AUB distinct from the irregular bleeding pattern typically caused by ovulatory dysfunction (AUB-O).1

Clinical evaluation

Obtain menstrual history. In addition to a medical, surgical, and gynecologic history, a thorough menstrual history should be obtained to further characterize the patient’s bleeding pattern. In contrast to the cyclical or ovulatory bleeding seen with HMB, bleeding associated with inconsistent ovulation (AUB-O) is unpredictable or irregular, and is commonly associated with PCOS. AUB-O is also encountered in recently menarchal girls (secondary to immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis) and in those who are perimenopausal. In addition, medications that can induce hyperprolactinemia (such as certain antipsychotics) can cause AUB-O.

Evaluate for all sources of bleeding. Be sure to evaluate for extrauterine causes of bleeding, including the cervix, vagina, vulva, or the urinary or gastrointestinal tracts for bleeding. Intermenstrual bleeding occurring between normal regular menses may be caused by an endometrial polyp, submucosal fibroid, endometritis, or an IUD. The patient report of postcoital bleeding suggests that cervical disease (cervicitis, polyp, or malignancy) may be present. Uterine leiomyoma or adenomyosis represent common causes of HMB. However, HMB also may be caused by a copper IUD, coagulation disorders (including von Willebrand disease), or use of anticoagulant medications. Hormonal contraceptives also can cause irregular bleeding.

Perform a pelvic examination and measure vital signs. The presence of fever suggests the possible presence of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), while orthostatic hypotension raises the possibility of hypovolemia. When vaginal speculum examination is performed, a cervical cause of abnormal bleeding may be noted. The presence of fresh or old blood or finding clots in the vaginal vault or at the cervical os are all consistent with AUB. A bimanual examination that reveals an enlarged or lobular uterus suggests leiomyoma or adenomyosis. Cervical or adnexal tenderness is often noted in women with PID, which itself may be associated with endometritis. The presence of hyperandrogenic signs on physical examination (eg, acne, hirsutism, or clitoromegaly) suggests PCOS. The finding of galactorrhea suggests that hyperprolactinemia may be present.

Laboratory assessment

Test for pregnancy, cervical disease, and sexually transmitted infection when appropriate. Pregnancy testing is appropriate for women with AUB aged 55 years or younger. If patients with AUB are not up to date with normal cervical cancer screening results, cervical cytology and/or human papillomavirus testing should be performed. Testing for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis should be performed in patients:

- younger than 25 years

- when the history indicates new or multiple sexual partners, or

- when vaginal discharge, cervicitis, cervical motion, or adnexal tenderness is present.

Continue to: Obtain a complete blood count and serum ferritin levels...

Obtain a complete blood count and serum ferritin levels. In women presenting with HMB, iron depletion and iron deficiency anemia are common. The finding of leukocytosis raises the possibility of PID or postpartum endometritis. In women with presumptive AUB-O, checking the levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, free T4, and prolactin should be performed.

Screen for a hemostasis disorder. Women with excessive menstrual bleeding should be clinically screened for an underlying disorder of hemostasis (TABLE 1).3 When a hemostasis disorder is suspected, initial laboratory evaluation includes a partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen. Women who have a positive clinical screen for a possible bleeding disorder or abnormal initial laboratory test results for disorders of hemostasis should undergo further laboratory evaluation, including von Willebrand factor antigen, ristocetin cofactor assay, and factor VIII. Consultation with a hematologist should be considered in these cases.

Perform endometrial biopsy when indicated

After excluding pregnancy, endometrial biopsy (through pipelle biospy or brush sampling; FIGURE 4) should be performed in women with AUB who are at increased risk for endometrial neoplasia. The prevalence of endometrial neoplasia is substantially higher among women ≥45 years of age4 and among patients with AUB who are also obese (BMI, ≥30 kg/m2).5 In addition, AUB patients with unopposed estrogen exposure (presumed anovulation/PCOS), as well as those with persistent AUB or failed medical management, should undergo endometrial biopsy.6

Utilize transvaginal ultrasonography

Transvaginal ultrasonography is often useful in the evaluation of patients with AUB, as it may identify uterine fibroids or adenomyosis, suggest intracavitary pathology (such as an endometrial polyp or submucosal fibroid), or raise the possibility of PCOS. In virginal patients or those in whom vaginal ultrasound is not appropriate, abdominal pelvic ultrasonography represents appropriate imaging. If unenhanced ultrasound suggests endometrial polyps or fibroids within the endometrial cavity, an office-based saline infusion sonogram (sonohysterogram) (FIGURE 5) or hysteroscopy should be performed. Targeted endometrial sampling and biopsy of intracavitary pathology can be performed at the time of hysteroscopy.

Treatment

When HMB impairs quality of life, is bothersome to the patient, or results in anemia, treatment is appropriate. Although bleeding episodes in women with AUB-O may be infrequent (as with Case 2), treatment prevents heavy or prolonged bleeding episodes as well as endometrial neoplasia that may otherwise occur in anovulatory women.

Many women with AUB can be managed medically. However, treatment choices will vary with respect to the patient’s desire for future fertility, medical comorbidities, personal preferences, and financial barriers. While many women may prefer outpatient medical management (TABLE 2),7-14 others might desire surgical therapy, including endometrial ablation or hysterectomy.

Oral contraceptives

Combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives represent appropriate initial therapy for many women in the reproductive-age group with AUB, whether women have HMB or AUB-O. However, contraceptive doses of estrogen are not appropriate for some women with risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including those who smoke cigarettes and are age ≥35 years or those who have hypertension (TABLE 3).15,16

Continue to: Menopausal dosages of HT...

Menopausal dosages of HT

If use of contraceptive doses of estrogen is not appropriate, continuous off-label use of menopausal combination formulations (physiologic dosage) of hormonal therapy (HT; ie, lower doses of estrogen than contraceptives) may be effective in reducing or eliminating AUB. Options for menopausal combination formulations include generic ethinyl estradiol 5 µg/norethindrone acetate 1 mg or estradiol 1 mg/norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg.7 High-dose oral progestin therapy (norethindrone acetate 5 mg tablet once daily or medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg tablets 1–3 times daily) also can be used when combination contraceptives are contraindicated and may be more effective than lower-dose combination formulations.

Package labeling, as well as some guidelines, indicate that oral progestins used to treat AUB should be taken cyclically.8 However, continuous daily use is easier for many patients and may be more effective in reducing bleeding. Accordingly, we counsel patients with AUB who are using progestins and who do not wish to conceive to take these medications continuously. High-dose oral progestin therapy may cause bloating, dysphoria, and increased appetite/weight gain. Women initiating hormonal management (including the progestin IUDs detailed below) for AUB should be counseled that irregular or even continuous light bleeding/spotting is common initially, but this bleeding pattern typically decreases with continued use.

IUDs

The LNG 52 mg IUD (Mirena or Liletta) effectively treats HMB, reducing bleeding in a manner comparable to that of endometrial ablation.9,10 The Mirena IUD is approved for treatment of HMB in women desiring intrauterine contraception. In contrast to oral medications, use of progestin IUDs does not involve daily administration and may represent an attractive option for women with HMB who would like to avoid surgery or preserve fertility. With ongoing use, continuous oral or intrauterine hormonal management may result in amenorrhea in some women with AUB.

When the LNG 52 mg IUD is used to treat HMB, the menstrual suppression impact may begin to attenuate after approximately 4 years of use; in this setting, replacing the IUD often restores effective menstrual suppression.11 The LNG 52 mg IUD effectively suppresses menses in women with coagulation disorders; if menstrual suppression with the progestin IUD is not adequate in this setting, it may be appropriate to add an oral combination estrogen-progestin contraceptive or high-dose oral progestin.11,12

NSAIDs and tranexamic acid

Off-label use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (naproxen 500–1,000 mg daily for 5 days beginning at the onset of menstrual flow or tranexamic acid two 650-mg tablets 3 times daily for up to 5 days during episodes of heavy flow) can suppress HMB and is useful for women who prefer to avoid or have contraindications to hormonal treatments.13,14 Unfortunately, these agents are not as effective as hormonal management in treating AUB.

Iron supplementation is often needed

Iron depletion commonly results from HMB, often resulting in iron deficiency anemia. When iron depletion (readily identified by checking a serum ferritin level) or iron deficiency anemia is identified, iron supplementation should be recommended. Every-other-day administration of iron supplements maximizes iron absorption while minimizing the adverse effects of unabsorbed iron, such as nausea. Sixty mg of elemental iron (ferrous sulfate 325 mg) administered every other day represents an inexpensive and effective treatment for iron deficiency/anemia.17 In patients who cannot tolerate oral iron supplementation or for those in whom oral therapy is not appropriate or effective, newer intravenous iron formulations are safe and effective.18

Continue to: Case 1 Follow-up...

Case 1 Follow-up

The patient noted marked improvement in her menstrual cramps following LNG-containing IUD placement. Although she also reported that she no longer experienced heavy menstrual flow or cramps, she was bothered by frequent, unpredictable light bleeding/spotting. You prescribed norethindrone acetate (NETA) 5-mg tablet orally once daily, to be used in addition to her IUD. After using the IUD with concomitant NETA for 2 months’ duration, she noted that her bleeding/spotting almost completely resolved; however, she did report feeling irritable with use of the progestin tablets. She subsequently stopped the NETA tablets and, after 6 months of additional follow-up, reported only minimal spotting and no cramps.

At this later follow-up visit, you noted that her hemoglobin level increased to 12.6 g/dL, and the ferritin level no longer indicated iron depletion. After the IUD had been in place for 4 years, she reported that she was beginning to experience frequent light bleeding again. A follow-up vaginal sonogram noted a well-positioned IUD, there was no suggestion of intracavitary pathology, and adenomyosis continued to be imaged. She underwent IUD removal and placement of a new LNG 52 mg IUD. This resulted in marked reduction in her bleeding.

Case 2 Follow-up

Two weeks after beginning continuous oral progestin therapy, the patient called reporting frequent irregular bleeding. She was reassured that this was not unexpected and encouraged to continue oral progestin therapy. During a 3-month follow-up visit, the patient noted little, if any, bleeding over the previous 2 months and was pleased with this result. She continued to note acne and hirsutism and asked about the possibility of adding spironolactone to her oral progestin regimen.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS; FIGO Menstrual Disorders Committee. The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:393-408.

- Kaunitz AM. Abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-age women. JAMA. 2019;321:2126-2127.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:891-896.

- National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Uterine Cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/corp.html. Accessed October 10, 2019.

- Wise MR, Gill P, Lensen S, et al. Body mass index trumps age in decision for endometrial biopsy: cohort study of symptomatic premenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:598.e1-598.e8.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

- The North American Menopause Society. Menopause Practice–A Clinician’s Guide. 5th ed. NAMS: Mayfield Heights, OH; 2014.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88. Accessed October 10, 2019.

- Kaunitz AM, Bissonnette F, Monteiro I, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or medroxyprogesterone for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:625-632.

- Kaunitz AM, Meredith S, Inki P, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and endometrial ablation in heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1104-1116.

- Kaunitz AM, Inki P. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in heavy menstrual bleeding: a benefit-risk review. Drugs. 2012;72:193-215.

- James AH, Kouides PA, Abdul-Kadir R, et al. Von Willebrand disease and other bleeding disorders in women: consensus on diagnosis and management from an international expert panel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:12.e1-8.

- Ylikorkala O, Pekonen F. Naproxen reduces idiopathic but not fibromyoma-induced menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68:10-12.

- Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:865-875.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–103.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin no. 206: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e128-e150.

- Stoffel NU, Cercamondi CI, Brittenham G, et al. Iron absorption from oral iron supplements given on consecutive versus alternate days and as single morning doses versus twice-daily split dosing in iron-depleted women: two open-label, randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e524–e533.

- Auerbach M, Adamson JW. How we diagnose and treat iron deficiency anemia. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:31-38.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS; FIGO Menstrual Disorders Committee. The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:393-408.

- Kaunitz AM. Abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-age women. JAMA. 2019;321:2126-2127.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:891-896.

- National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Uterine Cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/corp.html. Accessed October 10, 2019.

- Wise MR, Gill P, Lensen S, et al. Body mass index trumps age in decision for endometrial biopsy: cohort study of symptomatic premenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:598.e1-598.e8.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

- The North American Menopause Society. Menopause Practice–A Clinician’s Guide. 5th ed. NAMS: Mayfield Heights, OH; 2014.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88. Accessed October 10, 2019.

- Kaunitz AM, Bissonnette F, Monteiro I, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or medroxyprogesterone for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:625-632.

- Kaunitz AM, Meredith S, Inki P, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and endometrial ablation in heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1104-1116.

- Kaunitz AM, Inki P. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in heavy menstrual bleeding: a benefit-risk review. Drugs. 2012;72:193-215.

- James AH, Kouides PA, Abdul-Kadir R, et al. Von Willebrand disease and other bleeding disorders in women: consensus on diagnosis and management from an international expert panel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:12.e1-8.

- Ylikorkala O, Pekonen F. Naproxen reduces idiopathic but not fibromyoma-induced menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68:10-12.

- Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:865-875.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–103.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin no. 206: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e128-e150.

- Stoffel NU, Cercamondi CI, Brittenham G, et al. Iron absorption from oral iron supplements given on consecutive versus alternate days and as single morning doses versus twice-daily split dosing in iron-depleted women: two open-label, randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e524–e533.

- Auerbach M, Adamson JW. How we diagnose and treat iron deficiency anemia. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:31-38.

Using slings for the surgical management of urinary incontinence: A safe, effective, evidence-based approach

Urinary incontinence affects approximately 50% of women, with up to 80% of these women experiencing stress urinary incontinence (SUI) at some point in their lives.1-3 While conservative measures can offer some improvement in symptoms, the mainstay of treatment for SUI is surgical intervention.4,5 The lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for SUI is 13.6%, and surgery leads to a major improvement in quality of life and productivity.1,6

Types of slings used for SUI

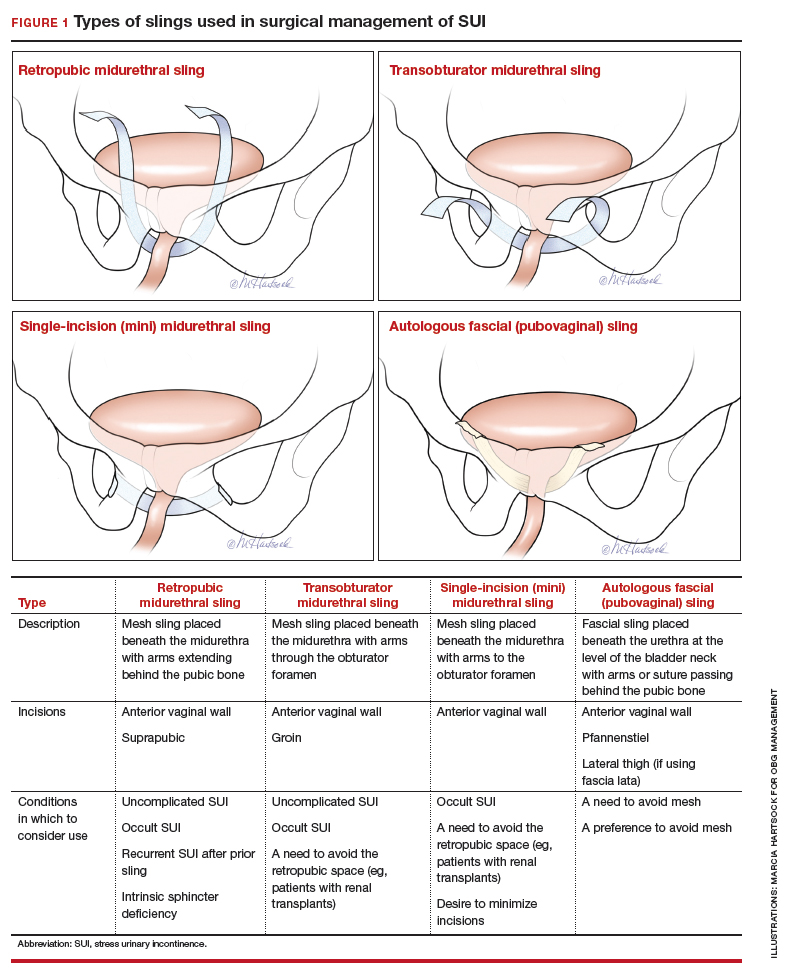

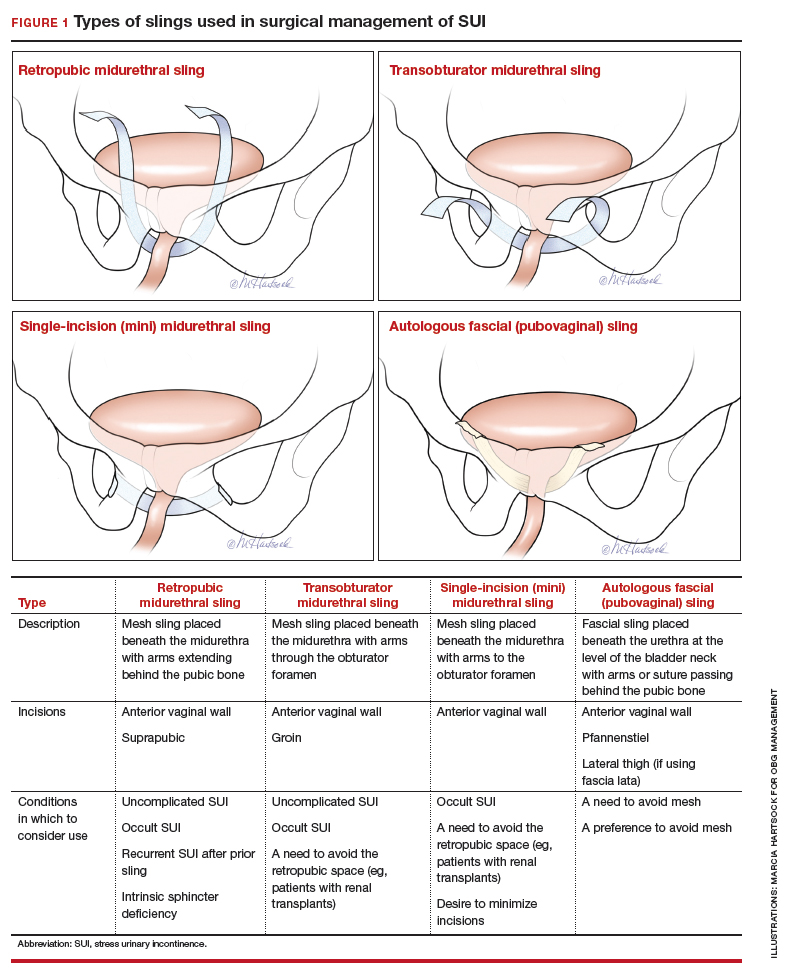

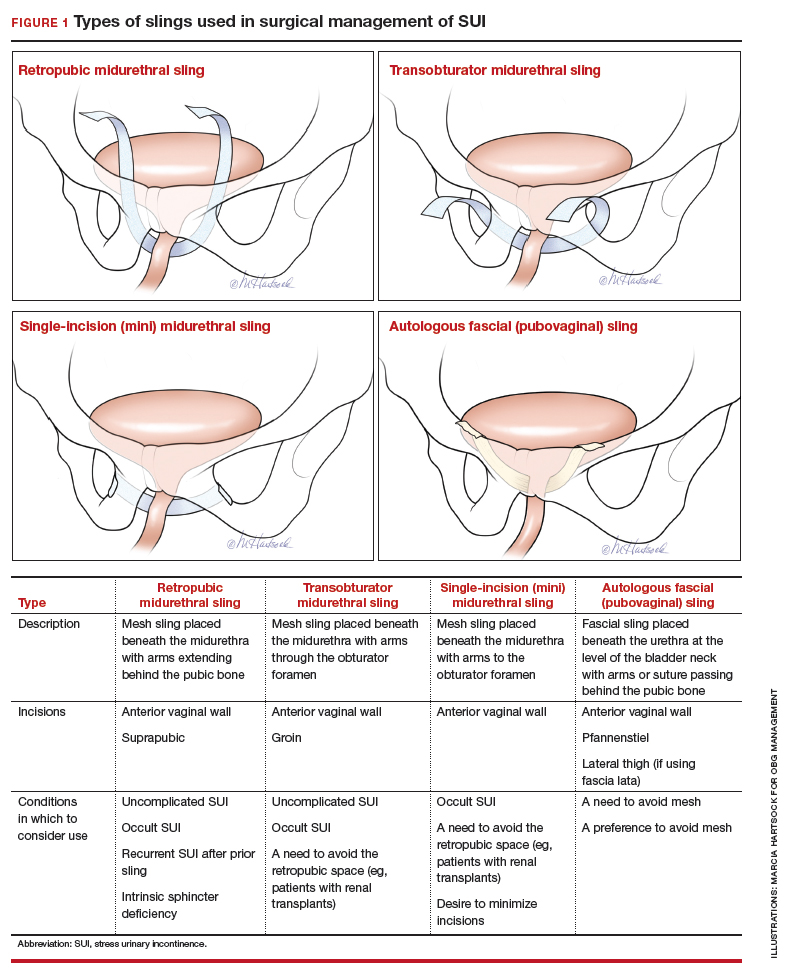

Sling procedures are the most commonly used surgical approach for the treatment of SUI. Two types of urethral slings are used: the midurethral sling and the autologous fascial (pubovaginal) sling. The midurethral sling, which is the most frequently used sling today, can be further characterized as the retropubic sling, the transobturator sling, and the mini sling (FIGURE 1).

Retropubic sling

A retropubic sling is a midurethral mesh sling that is placed beneath the urethra at the midpoint between the urethral meatus and the bladder neck. The arms of the sling extend behind the pubic symphysis, providing a hammock-like support that helps prevent leakage with increased abdominal pressures. The retropubic sling is the most commonly used type of sling. For women presenting with uncomplicated SUI who desire surgical correction, it often is the best choice for providing long-term treatment success.7

Transobturator sling

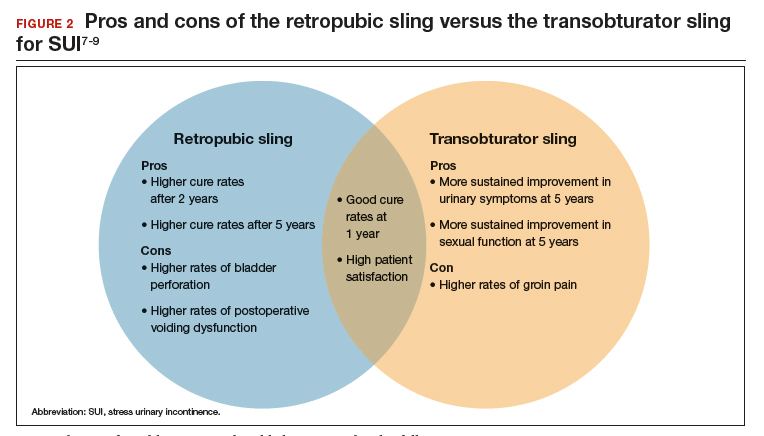

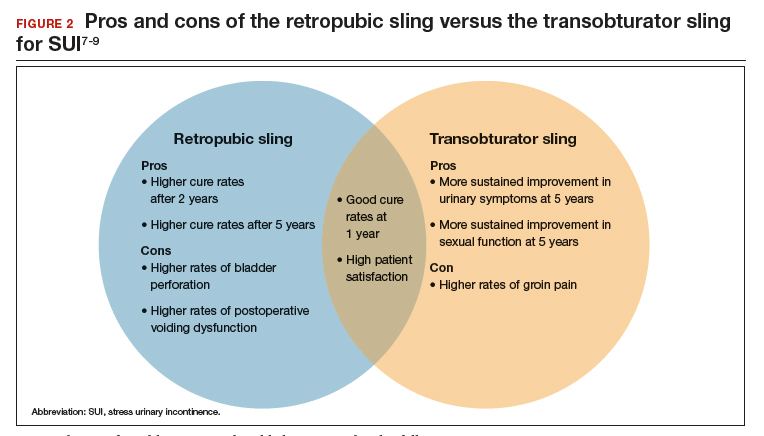

A transobturator sling is a midurethral mesh sling that is placed beneath the urethra as described above, but the arms of the sling extend outward through the obturator foramen and into the groin. This enables support of the midurethra, but this sling is less likely to result in such complications as bladder perforation or postoperative urinary retention. Transobturator slings also are associated with lower rates of voiding dysfunction and urinary urgency than retropubic slings.7-9 However, transobturator slings have higher rates of groin pain, and they are less effective in maintaining long-term cure of SUI.7

First introduced in 1996, the midurethral sling quickly grew in popularity for the treatment of SUI because of its high success rates and its minimally invasive approach.10 Both retropubic and transobturator slings are safe, extensively researched surgical approaches for the management of SUI.3 Midurethral slings have a very high rate of incontinence cure (80%–90%) and extremely high patient satisfaction rates (85%–90%), as even patients without complete cure report meaningful symptomatic improvement.7,8,11

Single-incision (mini) sling

A single-incision sling is a midurethral mesh sling that is designed to be shorter in length than standard midurethral slings. The placed sling lies under the midurethra and extends toward the superior edge of the obturator foramen but does not penetrate it. The sling is held in place by small pledgets on either side of the mesh hammock that anchor it in place to the obturator internus muscular fascia. Because this “mini” sling was introduced in 2006, fewer long-term data are available for this sling than for standard midurethral slings.

Continue to: Autologous (fascial) sling...

Autologous (fascial) sling

An autologous sling is a retropubic sling made from the patient’s own fascia; it is harvested from either the fascia lata of the lateral thigh or the rectus fascia of the abdomen. The sling is placed beneath the urethra in the bladder neck region, and sutures affixed to the sling edges pass behind the pubic symphysis and through the abdominal fascia to anchor it in place.

Choose a sling based on the clinical situation and patient goals

Consider the unique features of each sling when selecting the proper sling; this should be a shared decision with the patient after thorough counseling. Below, we present 4 clinical cases to exemplify scenarios in which different slings are appropriate, and we review the rationale for each selection.

CASE 1 SUI that interferes with exercise routine

Ms. P. is a 46-year-old (G3P3) active mother. She loves to exercise, but she has been working out less frequently because of embarrassing urinary leakage that occurs with activity. She has tried pelvic floor exercises and changing her fluid intake habits, but improvements have been minimal with these interventions. On evaluation, she has a positive cough stress test with a recently emptied bladder and a normal postvoid residual volume.

What type of sling would be best?

Because this patient is young, active, and has significant leakage with an empty bladder, a sling with good long-term treatment success is likely to provide her with the best results (Figure 1). We therefore offered her a retropubic midurethral sling. The retropubic approach is preferred here as it is less likely than the transobturator sling to cause groin/thigh pain, which is an important consideration in this young, active patient.

Further testing is not needed

For women with uncomplicated SUI who demonstrate leakage with stress (coughing, Valsalva stress test) and who have a normal postvoid residual volume, additional testing, such as urodynamic evaluation, is not necessary.12 These patients can be counseled on the range of conservative management options and as well as surgical inventions.

CASE 2 Return of SUI symptoms after transobturator sling placement

Ms. E. is a 70-year-old woman who had a transobturator sling placed 5 years ago. Initially, her SUI symptoms improved after surgery. Recently, however, she noticed a return of her SUI, which she finds bothersome and limiting to her quality of life.

How would you manage this patient?

While midurethral slings are highly effective, there are instances in which patients will have symptom recurrence. For women who already have a midurethral sling, consider the following important questions.

Is this truly recurrent SUI, or is it a new process?

Like any reconstructive procedure, midurethral sling success rates decline over time and recurrent SUI can develop.7 However, it also is possible for urge urinary incontinence to develop as a new process, and it is important to distinguish which type of urinary incontinence your patient has prior to counseling about treatment options.

To further evaluate patients with recurrent incontinence and a prior sling, we recommend urodynamic studies with cystoscopy (in addition to a detailed history and physical exam). This not only helps rule out other forms of incontinence, such as overactive bladder, but also evaluates for possible mesh erosion into the urethra or bladder, which can cause irritative voiding symptoms and incontinence.

Continue to: What type of sling did the patient have initially...

What type of sling did the patient have initially, and how does this impact a repeat procedure?

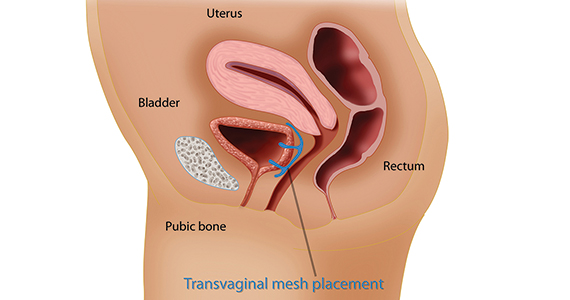

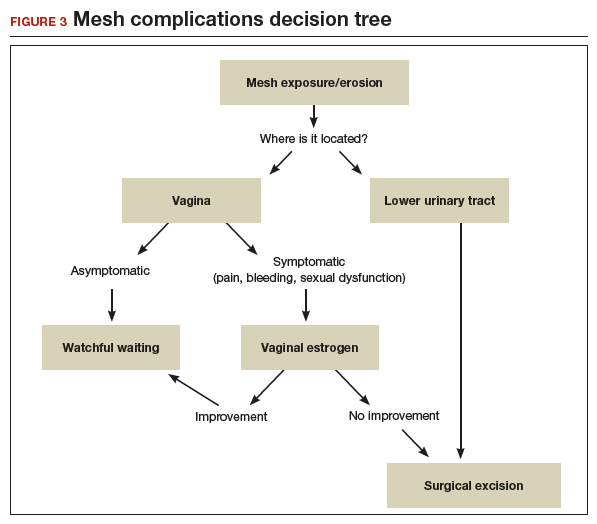

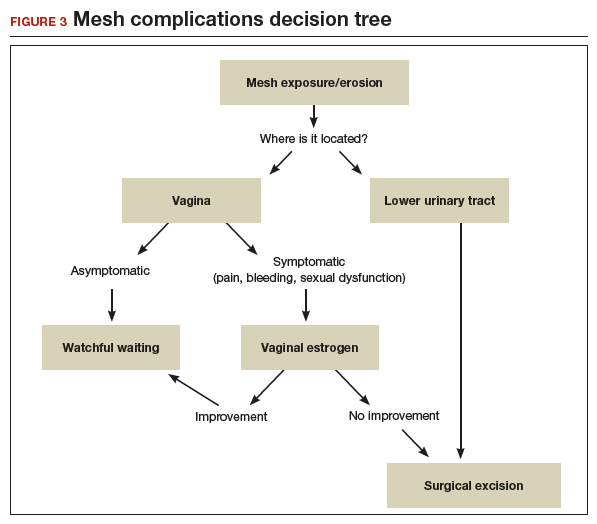

Regardless of the initial sling type used, repeat midurethral sling procedures have a significantly lower cure rate than primary midurethral sling procedures.13 Retropubic slings are more effective than transobturator slings for patients with recurrent SUI who have failed a prior sling. When a patient presents with recurrent SUI after a prior transobturator sling, the best option for a repeat procedure is usually a retropubic sling, as it achieves higher objective and subjective cure rates.13,14 (See FIGURE 2 for a comparison of retropubic and transobturator slings.)

Should I remove the old sling prior to placing a new one?

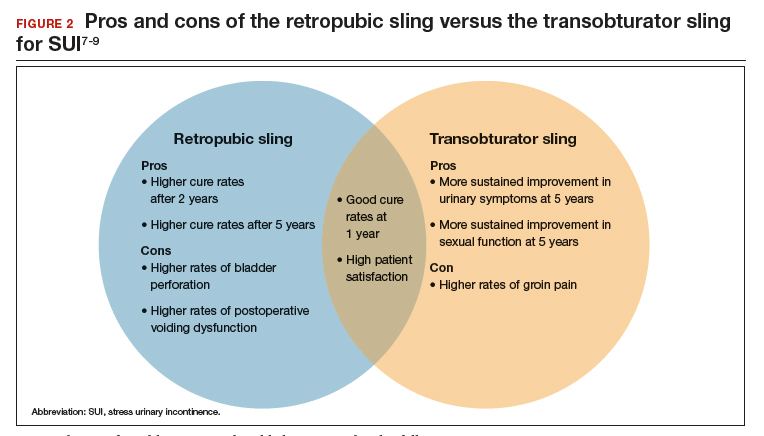

While it is recommended to remove the vaginal portion of the sling if the patient has a mesh exposure or is experiencing other symptoms, such as pain or bleeding, removal of the old sling is not necessarily indicated prior to (or during) a repeat incontinence procedure.15,16 Removing the sling, removing a portion of the sling, or leaving the sling in situ are all reasonable options.

CASE 3 Treated SUI has mesh exposure