User login

Researchers discover brain abnormalities in babies who had SIDS

For decades, researchers have been trying to understand why some otherwise healthy babies under 1 year old mysteriously die during their sleep. SIDS is the leading cause of infant death in the U.S., affecting 103 out of every 100,000 babies.

The new study found that babies who died of SIDS had abnormalities in certain brain receptors responsible for waking and restoring breathing. The scientists decided to look at the babies’ brains at the molecular level because previous research showed that the same kind of brain receptors in rodents are responsible for protective breathing functions during sleep.

The study was published in the Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. The researchers compared brain stems from 70 babies, some of whom died of SIDS and some who died of other causes.

Despite discovering the differences in the babies’ brains, the lead author of the paper said more study is needed.

Robin Haynes, PhD, who studies SIDS at Boston Children’s Hospital, said in a statement that “the relationship between the abnormalities and cause of death remains unknown.”

She said there is no way to identify babies with the brain abnormalities, and “thus, adherence to safe-sleep practices remains critical.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends numerous steps for creating a safe sleeping environment for babies, including placing babies on their backs on a firm surface. Education campaigns targeting parents and caregivers in the 1990s are largely considered successful, but SIDS rates have remained steady since the practices became widely used.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

For decades, researchers have been trying to understand why some otherwise healthy babies under 1 year old mysteriously die during their sleep. SIDS is the leading cause of infant death in the U.S., affecting 103 out of every 100,000 babies.

The new study found that babies who died of SIDS had abnormalities in certain brain receptors responsible for waking and restoring breathing. The scientists decided to look at the babies’ brains at the molecular level because previous research showed that the same kind of brain receptors in rodents are responsible for protective breathing functions during sleep.

The study was published in the Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. The researchers compared brain stems from 70 babies, some of whom died of SIDS and some who died of other causes.

Despite discovering the differences in the babies’ brains, the lead author of the paper said more study is needed.

Robin Haynes, PhD, who studies SIDS at Boston Children’s Hospital, said in a statement that “the relationship between the abnormalities and cause of death remains unknown.”

She said there is no way to identify babies with the brain abnormalities, and “thus, adherence to safe-sleep practices remains critical.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends numerous steps for creating a safe sleeping environment for babies, including placing babies on their backs on a firm surface. Education campaigns targeting parents and caregivers in the 1990s are largely considered successful, but SIDS rates have remained steady since the practices became widely used.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

For decades, researchers have been trying to understand why some otherwise healthy babies under 1 year old mysteriously die during their sleep. SIDS is the leading cause of infant death in the U.S., affecting 103 out of every 100,000 babies.

The new study found that babies who died of SIDS had abnormalities in certain brain receptors responsible for waking and restoring breathing. The scientists decided to look at the babies’ brains at the molecular level because previous research showed that the same kind of brain receptors in rodents are responsible for protective breathing functions during sleep.

The study was published in the Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. The researchers compared brain stems from 70 babies, some of whom died of SIDS and some who died of other causes.

Despite discovering the differences in the babies’ brains, the lead author of the paper said more study is needed.

Robin Haynes, PhD, who studies SIDS at Boston Children’s Hospital, said in a statement that “the relationship between the abnormalities and cause of death remains unknown.”

She said there is no way to identify babies with the brain abnormalities, and “thus, adherence to safe-sleep practices remains critical.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends numerous steps for creating a safe sleeping environment for babies, including placing babies on their backs on a firm surface. Education campaigns targeting parents and caregivers in the 1990s are largely considered successful, but SIDS rates have remained steady since the practices became widely used.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF NEUROPATHY & EXPERIMENTAL NEUROLOGY

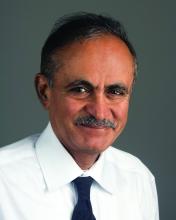

Standard measure may underestimate OSA in Black patients

Measurement error may be the culprit in underdiagnosing obstructive sleep apnea in Black patients, compared with White patients, based on data from nearly 2,000 individuals.

, according to Ali Azarbarzin, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“We wanted to examine the implications for obstructive sleep apnea,” which is often caused by a reduction in air flow, Dr. Azarbarzin said in an interview.

In a study presented at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference, Dr. Azarbarzin and colleagues examined data from 1,955 adults who were enrolled in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Exam 5. The study participants underwent unattended 15-channel polysomnography that included a finger pulse oximeter. The mean age of the participants was 68.3 years, and 53.7% were women. A total of 12.1%, 23.7%, 27.7%, and 36.5% of the participants were Asian, Hispanic, Black, and White, respectively.

Apnea hypopnea index (AHI3P) was similar between Black and White patients, at approximately 19 events per hour. Black participants had higher wake SpO2, higher current smoking rates, and higher body mass index, compared with White participants, but these differences were not significant.

Severity of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was based on the hypoxic burden, which was defined as the total area under the respiratory curve. The total ventilatory burden was defined as the event-specific area under the ventilation signal and identified by amplitude changes in the nasal pressure signal. The researchers then calculated desaturation sensitivity (the primary outcome) as hypoxic burden divided by ventilatory burden.

In an unadjusted analysis, desaturation sensitivity was significantly lower in Black patients and Asian patients, compared with White patients (P < .001 and P < .02, respectively). After adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, and time spent in a supine position, desaturation sensitivity was lower only in Black patients, compared with White patients, and this difference persisted in both men and women.

The difference in desaturation sensitivity by race could be caused by differences in physiology or in measurement error, Dr. Azarbarzin told this news organization. If measurement error is the culprit, “we may be underestimating OSA severity in [Black people],” especially in Black women, he said.

However, more research is needed to understand the potential impact of both physiology and device accuracy on differences in oxygen saturation across ethnicities and to effectively identify and treat OSA in all patients, Dr. Azarbarzin said.

The MESA Study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Aging. Data from MESA were obtained through support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Azarbarzin disclosed funding from the National Institutes of Health, the American Health Association, and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Measurement error may be the culprit in underdiagnosing obstructive sleep apnea in Black patients, compared with White patients, based on data from nearly 2,000 individuals.

, according to Ali Azarbarzin, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“We wanted to examine the implications for obstructive sleep apnea,” which is often caused by a reduction in air flow, Dr. Azarbarzin said in an interview.

In a study presented at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference, Dr. Azarbarzin and colleagues examined data from 1,955 adults who were enrolled in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Exam 5. The study participants underwent unattended 15-channel polysomnography that included a finger pulse oximeter. The mean age of the participants was 68.3 years, and 53.7% were women. A total of 12.1%, 23.7%, 27.7%, and 36.5% of the participants were Asian, Hispanic, Black, and White, respectively.

Apnea hypopnea index (AHI3P) was similar between Black and White patients, at approximately 19 events per hour. Black participants had higher wake SpO2, higher current smoking rates, and higher body mass index, compared with White participants, but these differences were not significant.

Severity of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was based on the hypoxic burden, which was defined as the total area under the respiratory curve. The total ventilatory burden was defined as the event-specific area under the ventilation signal and identified by amplitude changes in the nasal pressure signal. The researchers then calculated desaturation sensitivity (the primary outcome) as hypoxic burden divided by ventilatory burden.

In an unadjusted analysis, desaturation sensitivity was significantly lower in Black patients and Asian patients, compared with White patients (P < .001 and P < .02, respectively). After adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, and time spent in a supine position, desaturation sensitivity was lower only in Black patients, compared with White patients, and this difference persisted in both men and women.

The difference in desaturation sensitivity by race could be caused by differences in physiology or in measurement error, Dr. Azarbarzin told this news organization. If measurement error is the culprit, “we may be underestimating OSA severity in [Black people],” especially in Black women, he said.

However, more research is needed to understand the potential impact of both physiology and device accuracy on differences in oxygen saturation across ethnicities and to effectively identify and treat OSA in all patients, Dr. Azarbarzin said.

The MESA Study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Aging. Data from MESA were obtained through support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Azarbarzin disclosed funding from the National Institutes of Health, the American Health Association, and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Measurement error may be the culprit in underdiagnosing obstructive sleep apnea in Black patients, compared with White patients, based on data from nearly 2,000 individuals.

, according to Ali Azarbarzin, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“We wanted to examine the implications for obstructive sleep apnea,” which is often caused by a reduction in air flow, Dr. Azarbarzin said in an interview.

In a study presented at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference, Dr. Azarbarzin and colleagues examined data from 1,955 adults who were enrolled in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Exam 5. The study participants underwent unattended 15-channel polysomnography that included a finger pulse oximeter. The mean age of the participants was 68.3 years, and 53.7% were women. A total of 12.1%, 23.7%, 27.7%, and 36.5% of the participants were Asian, Hispanic, Black, and White, respectively.

Apnea hypopnea index (AHI3P) was similar between Black and White patients, at approximately 19 events per hour. Black participants had higher wake SpO2, higher current smoking rates, and higher body mass index, compared with White participants, but these differences were not significant.

Severity of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was based on the hypoxic burden, which was defined as the total area under the respiratory curve. The total ventilatory burden was defined as the event-specific area under the ventilation signal and identified by amplitude changes in the nasal pressure signal. The researchers then calculated desaturation sensitivity (the primary outcome) as hypoxic burden divided by ventilatory burden.

In an unadjusted analysis, desaturation sensitivity was significantly lower in Black patients and Asian patients, compared with White patients (P < .001 and P < .02, respectively). After adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, and time spent in a supine position, desaturation sensitivity was lower only in Black patients, compared with White patients, and this difference persisted in both men and women.

The difference in desaturation sensitivity by race could be caused by differences in physiology or in measurement error, Dr. Azarbarzin told this news organization. If measurement error is the culprit, “we may be underestimating OSA severity in [Black people],” especially in Black women, he said.

However, more research is needed to understand the potential impact of both physiology and device accuracy on differences in oxygen saturation across ethnicities and to effectively identify and treat OSA in all patients, Dr. Azarbarzin said.

The MESA Study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Aging. Data from MESA were obtained through support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Azarbarzin disclosed funding from the National Institutes of Health, the American Health Association, and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ATS 2023

Which drug best reduces sleepiness in patients with OSA?

Solriamfetol who have residual daytime sleepiness after conventional treatment, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a systematic review of 14 trials that included more than 3,000 patients, solriamfetol was associated with improvements of 3.85 points on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score, compared with placebo.

“We found that solriamfetol is almost twice as effective as modafinil-armodafinil – the cheaper, older option – in improving the ESS score and much more effective at improving the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT),” study author Tyler Pitre, MD, an internal medicine physician at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.

The findings were published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

High-certainty evidence

The analysis included 3,085 adults with excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) who were receiving or were eligible for conventional OSA treatment such as positive airway pressure. Participants were randomly assigned to either placebo or any EDS pharmacotherapy (armodafinil, modafinil, solriamfetol, or pitolisant). The primary outcomes of the analysis were change in ESS and MWT. Secondary outcomes were drug-related adverse events.

The trials had a median follow-up time of 4 weeks. The meta-analysis showed that solriamfetol improves ESS to a greater extent than placebo (high certainty), armodafinil-modafinil and pitolisant (moderate certainty). Compared with placebo, the mean difference in ESS scores for solriamfetol, armodafinil-modafinil, and pitolisant was –3.85, –2.25, and –2.78, respectively.

The analysis yielded high-certainty evidence that solriamfetol and armodafinil-modafinil improved MWT, compared with placebo. The former was “probably superior,” while pitolisant “may have little to no effect on MWT, compared with placebo,” write the authors. The standardized mean difference in MWT scores, compared with placebo, was 0.90 for solriamfetol and 0.41 for armodafinil-modafinil. “Solriamfetol is probably superior to armodafinil-modafinil in improving MWT (SMD, 0.49),” say the authors.

Compared with placebo, armodafinil-modafinil probably increases the risk for discontinuation due to adverse events (relative risk, 2.01), and solriamfetol may increase the risk for discontinuation (RR, 2.04), according to the authors. Pitolisant “may have little to no effect on drug discontinuations due to adverse events,” write the authors.

Although solriamfetol may have led to more discontinuations than armodafinil-modafinil, “we did not find convincing evidence of serious adverse events, albeit with very short-term follow-up,” they add.

The most common side effects for all interventions were headaches, insomnia, and anxiety. Headaches were most likely with armodafinil-modafinil (RR, 1.87), and insomnia was most likely with pitolisant (RR, 7.25).

“Although solriamfetol appears most effective, comorbid hypertension and costs may be barriers to its use,” say the researchers. “Furthermore, there are potentially effective candidate therapies such as methylphenidate, atomoxetine, or caffeine, which have not been examined in randomized clinical trials.”

Although EDS is reported in 40%-58% of patients with OSA and can persist in 6%-18% despite PAP therapy, most non-sleep specialists may not be aware of pharmacologic options, said Dr. Pitre. “I have not seen a study that looks at the prescribing habits of physicians for this condition, but I suspect that primary care physicians are not prescribing modafinil-armodafinil frequently for this and less so for solriamfetol,” he said. “I hope this paper builds awareness of this condition and also informs clinicians on the options available to patients, as well as common side effects to counsel them on before starting treatment.”

Dr. Pitre was surprised at the magnitude of solriamfetol’s superiority to modafinil-armodafinil but cautioned that solriamfetol has been shown to increase blood pressure in higher doses. It therefore must be prescribed carefully, “especially to a population of patients who often have comorbid hypertension,” he said.

Some limitations of the analysis were that all trials were conducted in high-income countries (most commonly the United States). Moreover, 77% of participants were White, and 71% were male.

Beneficial adjunctive therapy

Commenting on the findings, Sogol Javaheri, MD, MPH, who was not involved in the research, said that they confirm those of prior studies and are “consistent with what my colleagues and I experience in our clinical practices.”

Dr. Javaheri is associate program director of the sleep medicine fellowship at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

While sleep medicine specialists are more likely than others to prescribe these medications, “any clinician may use these medications, ideally if they have ruled out other potential reversible causes of EDS,” said Dr. Javaheri. “The medications do not treat the underlying cause, which is why it’s important to use them as an adjunct to conventional therapy that actually treats the underlying sleep disorder and to rule out additional potential causes of sleepiness that are treatable.”

These potential causes might include insufficient sleep (less than 7 hours per night), untreated anemia, and incompletely treated sleep disorders, she explained. In sleep medicine, modafinil is usually the treatment of choice because of its lower cost, but it may reduce the efficacy of hormonal contraception. Solriamfetol, however, does not. “Additionally, I look forward to validation of pitolisant for treatment of EDS in OSA patients, as it is not a controlled substance and may benefit patients with a history of substance abuse or who may be at higher risk of addiction,” said Dr. Javaheri.

The study was conducted without outside funding. Dr. Pitre and Dr. Javaheri report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Solriamfetol who have residual daytime sleepiness after conventional treatment, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a systematic review of 14 trials that included more than 3,000 patients, solriamfetol was associated with improvements of 3.85 points on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score, compared with placebo.

“We found that solriamfetol is almost twice as effective as modafinil-armodafinil – the cheaper, older option – in improving the ESS score and much more effective at improving the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT),” study author Tyler Pitre, MD, an internal medicine physician at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.

The findings were published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

High-certainty evidence

The analysis included 3,085 adults with excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) who were receiving or were eligible for conventional OSA treatment such as positive airway pressure. Participants were randomly assigned to either placebo or any EDS pharmacotherapy (armodafinil, modafinil, solriamfetol, or pitolisant). The primary outcomes of the analysis were change in ESS and MWT. Secondary outcomes were drug-related adverse events.

The trials had a median follow-up time of 4 weeks. The meta-analysis showed that solriamfetol improves ESS to a greater extent than placebo (high certainty), armodafinil-modafinil and pitolisant (moderate certainty). Compared with placebo, the mean difference in ESS scores for solriamfetol, armodafinil-modafinil, and pitolisant was –3.85, –2.25, and –2.78, respectively.

The analysis yielded high-certainty evidence that solriamfetol and armodafinil-modafinil improved MWT, compared with placebo. The former was “probably superior,” while pitolisant “may have little to no effect on MWT, compared with placebo,” write the authors. The standardized mean difference in MWT scores, compared with placebo, was 0.90 for solriamfetol and 0.41 for armodafinil-modafinil. “Solriamfetol is probably superior to armodafinil-modafinil in improving MWT (SMD, 0.49),” say the authors.

Compared with placebo, armodafinil-modafinil probably increases the risk for discontinuation due to adverse events (relative risk, 2.01), and solriamfetol may increase the risk for discontinuation (RR, 2.04), according to the authors. Pitolisant “may have little to no effect on drug discontinuations due to adverse events,” write the authors.

Although solriamfetol may have led to more discontinuations than armodafinil-modafinil, “we did not find convincing evidence of serious adverse events, albeit with very short-term follow-up,” they add.

The most common side effects for all interventions were headaches, insomnia, and anxiety. Headaches were most likely with armodafinil-modafinil (RR, 1.87), and insomnia was most likely with pitolisant (RR, 7.25).

“Although solriamfetol appears most effective, comorbid hypertension and costs may be barriers to its use,” say the researchers. “Furthermore, there are potentially effective candidate therapies such as methylphenidate, atomoxetine, or caffeine, which have not been examined in randomized clinical trials.”

Although EDS is reported in 40%-58% of patients with OSA and can persist in 6%-18% despite PAP therapy, most non-sleep specialists may not be aware of pharmacologic options, said Dr. Pitre. “I have not seen a study that looks at the prescribing habits of physicians for this condition, but I suspect that primary care physicians are not prescribing modafinil-armodafinil frequently for this and less so for solriamfetol,” he said. “I hope this paper builds awareness of this condition and also informs clinicians on the options available to patients, as well as common side effects to counsel them on before starting treatment.”

Dr. Pitre was surprised at the magnitude of solriamfetol’s superiority to modafinil-armodafinil but cautioned that solriamfetol has been shown to increase blood pressure in higher doses. It therefore must be prescribed carefully, “especially to a population of patients who often have comorbid hypertension,” he said.

Some limitations of the analysis were that all trials were conducted in high-income countries (most commonly the United States). Moreover, 77% of participants were White, and 71% were male.

Beneficial adjunctive therapy

Commenting on the findings, Sogol Javaheri, MD, MPH, who was not involved in the research, said that they confirm those of prior studies and are “consistent with what my colleagues and I experience in our clinical practices.”

Dr. Javaheri is associate program director of the sleep medicine fellowship at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

While sleep medicine specialists are more likely than others to prescribe these medications, “any clinician may use these medications, ideally if they have ruled out other potential reversible causes of EDS,” said Dr. Javaheri. “The medications do not treat the underlying cause, which is why it’s important to use them as an adjunct to conventional therapy that actually treats the underlying sleep disorder and to rule out additional potential causes of sleepiness that are treatable.”

These potential causes might include insufficient sleep (less than 7 hours per night), untreated anemia, and incompletely treated sleep disorders, she explained. In sleep medicine, modafinil is usually the treatment of choice because of its lower cost, but it may reduce the efficacy of hormonal contraception. Solriamfetol, however, does not. “Additionally, I look forward to validation of pitolisant for treatment of EDS in OSA patients, as it is not a controlled substance and may benefit patients with a history of substance abuse or who may be at higher risk of addiction,” said Dr. Javaheri.

The study was conducted without outside funding. Dr. Pitre and Dr. Javaheri report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Solriamfetol who have residual daytime sleepiness after conventional treatment, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a systematic review of 14 trials that included more than 3,000 patients, solriamfetol was associated with improvements of 3.85 points on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score, compared with placebo.

“We found that solriamfetol is almost twice as effective as modafinil-armodafinil – the cheaper, older option – in improving the ESS score and much more effective at improving the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT),” study author Tyler Pitre, MD, an internal medicine physician at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.

The findings were published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

High-certainty evidence

The analysis included 3,085 adults with excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) who were receiving or were eligible for conventional OSA treatment such as positive airway pressure. Participants were randomly assigned to either placebo or any EDS pharmacotherapy (armodafinil, modafinil, solriamfetol, or pitolisant). The primary outcomes of the analysis were change in ESS and MWT. Secondary outcomes were drug-related adverse events.

The trials had a median follow-up time of 4 weeks. The meta-analysis showed that solriamfetol improves ESS to a greater extent than placebo (high certainty), armodafinil-modafinil and pitolisant (moderate certainty). Compared with placebo, the mean difference in ESS scores for solriamfetol, armodafinil-modafinil, and pitolisant was –3.85, –2.25, and –2.78, respectively.

The analysis yielded high-certainty evidence that solriamfetol and armodafinil-modafinil improved MWT, compared with placebo. The former was “probably superior,” while pitolisant “may have little to no effect on MWT, compared with placebo,” write the authors. The standardized mean difference in MWT scores, compared with placebo, was 0.90 for solriamfetol and 0.41 for armodafinil-modafinil. “Solriamfetol is probably superior to armodafinil-modafinil in improving MWT (SMD, 0.49),” say the authors.

Compared with placebo, armodafinil-modafinil probably increases the risk for discontinuation due to adverse events (relative risk, 2.01), and solriamfetol may increase the risk for discontinuation (RR, 2.04), according to the authors. Pitolisant “may have little to no effect on drug discontinuations due to adverse events,” write the authors.

Although solriamfetol may have led to more discontinuations than armodafinil-modafinil, “we did not find convincing evidence of serious adverse events, albeit with very short-term follow-up,” they add.

The most common side effects for all interventions were headaches, insomnia, and anxiety. Headaches were most likely with armodafinil-modafinil (RR, 1.87), and insomnia was most likely with pitolisant (RR, 7.25).

“Although solriamfetol appears most effective, comorbid hypertension and costs may be barriers to its use,” say the researchers. “Furthermore, there are potentially effective candidate therapies such as methylphenidate, atomoxetine, or caffeine, which have not been examined in randomized clinical trials.”

Although EDS is reported in 40%-58% of patients with OSA and can persist in 6%-18% despite PAP therapy, most non-sleep specialists may not be aware of pharmacologic options, said Dr. Pitre. “I have not seen a study that looks at the prescribing habits of physicians for this condition, but I suspect that primary care physicians are not prescribing modafinil-armodafinil frequently for this and less so for solriamfetol,” he said. “I hope this paper builds awareness of this condition and also informs clinicians on the options available to patients, as well as common side effects to counsel them on before starting treatment.”

Dr. Pitre was surprised at the magnitude of solriamfetol’s superiority to modafinil-armodafinil but cautioned that solriamfetol has been shown to increase blood pressure in higher doses. It therefore must be prescribed carefully, “especially to a population of patients who often have comorbid hypertension,” he said.

Some limitations of the analysis were that all trials were conducted in high-income countries (most commonly the United States). Moreover, 77% of participants were White, and 71% were male.

Beneficial adjunctive therapy

Commenting on the findings, Sogol Javaheri, MD, MPH, who was not involved in the research, said that they confirm those of prior studies and are “consistent with what my colleagues and I experience in our clinical practices.”

Dr. Javaheri is associate program director of the sleep medicine fellowship at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

While sleep medicine specialists are more likely than others to prescribe these medications, “any clinician may use these medications, ideally if they have ruled out other potential reversible causes of EDS,” said Dr. Javaheri. “The medications do not treat the underlying cause, which is why it’s important to use them as an adjunct to conventional therapy that actually treats the underlying sleep disorder and to rule out additional potential causes of sleepiness that are treatable.”

These potential causes might include insufficient sleep (less than 7 hours per night), untreated anemia, and incompletely treated sleep disorders, she explained. In sleep medicine, modafinil is usually the treatment of choice because of its lower cost, but it may reduce the efficacy of hormonal contraception. Solriamfetol, however, does not. “Additionally, I look forward to validation of pitolisant for treatment of EDS in OSA patients, as it is not a controlled substance and may benefit patients with a history of substance abuse or who may be at higher risk of addiction,” said Dr. Javaheri.

The study was conducted without outside funding. Dr. Pitre and Dr. Javaheri report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Deep sleep may mitigate the impact of Alzheimer’s pathology

Investigators found that deep sleep, also known as non-REM (NREM) slow-wave sleep, can protect memory function in cognitively normal adults with a high beta-amyloid burden.

“Think of deep sleep almost like a life raft that keeps memory afloat, rather than memory getting dragged down by the weight of Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” senior investigator Matthew Walker, PhD, professor of neuroscience and psychology, University of California, Berkeley, said in a news release.

The study was published online in BMC Medicine.

Resilience factor

Studying resilience to existing brain pathology is “an exciting new research direction,” lead author Zsófia Zavecz, PhD, with the Center for Human Sleep Science at the University of California, Berkeley, said in an interview.

“That is, what factors explain the individual differences in cognitive function despite the same level of brain pathology, and how do some people with significant pathology have largely preserved memory?” she added.

The study included 62 cognitively normal older adults from the Berkeley Aging Cohort Study.

Sleep EEG recordings were obtained over 2 nights in a sleep lab and PET scans were used to quantify beta-amyloid. Half of the participants had high beta-amyloid burden and half were beta-amyloid negative.

After the sleep studies, all participants completed a memory task involving matching names to faces.

The results suggest that deep NREM slow-wave sleep significantly moderates the effect of beta-amyloid status on memory function.

Specifically, NREM slow-wave activity selectively supported superior memory function in adults with high beta-amyloid burden, who are most in need of cognitive reserve (B = 2.694, P = .019), the researchers report.

In contrast, adults without significant beta-amyloid pathological burden – and thus without the same need for cognitive reserve – did not similarly benefit from NREM slow-wave activity (B = –0.115, P = .876).

The findings remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, gray matter atrophy, and previously identified cognitive reserve factors, such as education and physical activity.

Dr. Zavecz said there are several potential reasons why deep sleep may support cognitive reserve.

One is that during deep sleep specifically, memories are replayed in the brain, and this results in a “neural reorganization” that helps stabilize the memory and make it more permanent.

“Other explanations include deep sleep’s role in maintaining homeostasis in the brain’s capacity to form new neural connections and providing an optimal brain state for the clearance of toxins interfering with healthy brain functioning,” she noted.

“The extent to which sleep could offer a protective buffer against severe cognitive impairment remains to be tested. However, this study is the first step in hopefully a series of new research that will investigate sleep as a cognitive reserve factor,” said Dr. Zavecz.

Encouraging data

Reached for comment, Percy Griffin, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association director of scientific engagement, said although the study sample is small, the results are “encouraging because sleep is a modifiable factor and can therefore be targeted.”

“More work is needed in a larger population before we can fully leverage this stage of sleep to reduce the risk of developing cognitive decline,” Dr. Griffin said.

Also weighing in on this research, Shaheen Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist and researcher in Boston, said the study is “exciting on two fronts – we may have an additional marker for the development of Alzheimer’s disease to predict risk and track disease, but also targets for early intervention with sleep architecture–enhancing therapies, be they drug, device, or digital.”

“For the sake of our brain health, we all must get very familiar with the concept of cognitive or brain reserve,” said Dr. Lakhan, who was not involved in the study.

“Brain reserve refers to our ability to buttress against the threat of dementia and classically it’s been associated with ongoing brain stimulation (i.e., higher education, cognitively demanding job),” he noted.

“This line of research now opens the door that optimal sleep health – especially deep NREM slow wave sleep – correlates with greater brain reserve against Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Lakhan said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Walker serves as an advisor to and has equity interest in Bryte, Shuni, Oura, and StimScience. Dr. Zavecz and Dr. Lakhan report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that deep sleep, also known as non-REM (NREM) slow-wave sleep, can protect memory function in cognitively normal adults with a high beta-amyloid burden.

“Think of deep sleep almost like a life raft that keeps memory afloat, rather than memory getting dragged down by the weight of Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” senior investigator Matthew Walker, PhD, professor of neuroscience and psychology, University of California, Berkeley, said in a news release.

The study was published online in BMC Medicine.

Resilience factor

Studying resilience to existing brain pathology is “an exciting new research direction,” lead author Zsófia Zavecz, PhD, with the Center for Human Sleep Science at the University of California, Berkeley, said in an interview.

“That is, what factors explain the individual differences in cognitive function despite the same level of brain pathology, and how do some people with significant pathology have largely preserved memory?” she added.

The study included 62 cognitively normal older adults from the Berkeley Aging Cohort Study.

Sleep EEG recordings were obtained over 2 nights in a sleep lab and PET scans were used to quantify beta-amyloid. Half of the participants had high beta-amyloid burden and half were beta-amyloid negative.

After the sleep studies, all participants completed a memory task involving matching names to faces.

The results suggest that deep NREM slow-wave sleep significantly moderates the effect of beta-amyloid status on memory function.

Specifically, NREM slow-wave activity selectively supported superior memory function in adults with high beta-amyloid burden, who are most in need of cognitive reserve (B = 2.694, P = .019), the researchers report.

In contrast, adults without significant beta-amyloid pathological burden – and thus without the same need for cognitive reserve – did not similarly benefit from NREM slow-wave activity (B = –0.115, P = .876).

The findings remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, gray matter atrophy, and previously identified cognitive reserve factors, such as education and physical activity.

Dr. Zavecz said there are several potential reasons why deep sleep may support cognitive reserve.

One is that during deep sleep specifically, memories are replayed in the brain, and this results in a “neural reorganization” that helps stabilize the memory and make it more permanent.

“Other explanations include deep sleep’s role in maintaining homeostasis in the brain’s capacity to form new neural connections and providing an optimal brain state for the clearance of toxins interfering with healthy brain functioning,” she noted.

“The extent to which sleep could offer a protective buffer against severe cognitive impairment remains to be tested. However, this study is the first step in hopefully a series of new research that will investigate sleep as a cognitive reserve factor,” said Dr. Zavecz.

Encouraging data

Reached for comment, Percy Griffin, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association director of scientific engagement, said although the study sample is small, the results are “encouraging because sleep is a modifiable factor and can therefore be targeted.”

“More work is needed in a larger population before we can fully leverage this stage of sleep to reduce the risk of developing cognitive decline,” Dr. Griffin said.

Also weighing in on this research, Shaheen Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist and researcher in Boston, said the study is “exciting on two fronts – we may have an additional marker for the development of Alzheimer’s disease to predict risk and track disease, but also targets for early intervention with sleep architecture–enhancing therapies, be they drug, device, or digital.”

“For the sake of our brain health, we all must get very familiar with the concept of cognitive or brain reserve,” said Dr. Lakhan, who was not involved in the study.

“Brain reserve refers to our ability to buttress against the threat of dementia and classically it’s been associated with ongoing brain stimulation (i.e., higher education, cognitively demanding job),” he noted.

“This line of research now opens the door that optimal sleep health – especially deep NREM slow wave sleep – correlates with greater brain reserve against Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Lakhan said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Walker serves as an advisor to and has equity interest in Bryte, Shuni, Oura, and StimScience. Dr. Zavecz and Dr. Lakhan report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that deep sleep, also known as non-REM (NREM) slow-wave sleep, can protect memory function in cognitively normal adults with a high beta-amyloid burden.

“Think of deep sleep almost like a life raft that keeps memory afloat, rather than memory getting dragged down by the weight of Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” senior investigator Matthew Walker, PhD, professor of neuroscience and psychology, University of California, Berkeley, said in a news release.

The study was published online in BMC Medicine.

Resilience factor

Studying resilience to existing brain pathology is “an exciting new research direction,” lead author Zsófia Zavecz, PhD, with the Center for Human Sleep Science at the University of California, Berkeley, said in an interview.

“That is, what factors explain the individual differences in cognitive function despite the same level of brain pathology, and how do some people with significant pathology have largely preserved memory?” she added.

The study included 62 cognitively normal older adults from the Berkeley Aging Cohort Study.

Sleep EEG recordings were obtained over 2 nights in a sleep lab and PET scans were used to quantify beta-amyloid. Half of the participants had high beta-amyloid burden and half were beta-amyloid negative.

After the sleep studies, all participants completed a memory task involving matching names to faces.

The results suggest that deep NREM slow-wave sleep significantly moderates the effect of beta-amyloid status on memory function.

Specifically, NREM slow-wave activity selectively supported superior memory function in adults with high beta-amyloid burden, who are most in need of cognitive reserve (B = 2.694, P = .019), the researchers report.

In contrast, adults without significant beta-amyloid pathological burden – and thus without the same need for cognitive reserve – did not similarly benefit from NREM slow-wave activity (B = –0.115, P = .876).

The findings remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, gray matter atrophy, and previously identified cognitive reserve factors, such as education and physical activity.

Dr. Zavecz said there are several potential reasons why deep sleep may support cognitive reserve.

One is that during deep sleep specifically, memories are replayed in the brain, and this results in a “neural reorganization” that helps stabilize the memory and make it more permanent.

“Other explanations include deep sleep’s role in maintaining homeostasis in the brain’s capacity to form new neural connections and providing an optimal brain state for the clearance of toxins interfering with healthy brain functioning,” she noted.

“The extent to which sleep could offer a protective buffer against severe cognitive impairment remains to be tested. However, this study is the first step in hopefully a series of new research that will investigate sleep as a cognitive reserve factor,” said Dr. Zavecz.

Encouraging data

Reached for comment, Percy Griffin, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association director of scientific engagement, said although the study sample is small, the results are “encouraging because sleep is a modifiable factor and can therefore be targeted.”

“More work is needed in a larger population before we can fully leverage this stage of sleep to reduce the risk of developing cognitive decline,” Dr. Griffin said.

Also weighing in on this research, Shaheen Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist and researcher in Boston, said the study is “exciting on two fronts – we may have an additional marker for the development of Alzheimer’s disease to predict risk and track disease, but also targets for early intervention with sleep architecture–enhancing therapies, be they drug, device, or digital.”

“For the sake of our brain health, we all must get very familiar with the concept of cognitive or brain reserve,” said Dr. Lakhan, who was not involved in the study.

“Brain reserve refers to our ability to buttress against the threat of dementia and classically it’s been associated with ongoing brain stimulation (i.e., higher education, cognitively demanding job),” he noted.

“This line of research now opens the door that optimal sleep health – especially deep NREM slow wave sleep – correlates with greater brain reserve against Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Lakhan said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Walker serves as an advisor to and has equity interest in Bryte, Shuni, Oura, and StimScience. Dr. Zavecz and Dr. Lakhan report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMC MEDICINE

Medical-level empathy? Yup, ChatGPT can fake that

Caution: Robotic uprisings in the rearview mirror are closer than they appear

ChatGPT. If you’ve been even in the proximity of the Internet lately, you may have heard of it. It’s quite an incredible piece of technology, an artificial intelligence that really could up-end a lot of industries. And lest doctors believe they’re safe from robotic replacement, consider this: ChatGPT took a test commonly used as a study resource by ophthalmologists and scored a 46%. Obviously, that’s not a passing grade. Job safe, right?

A month later, the researchers tried again. This time, ChatGPT got a 58%. Still not passing, and ChatGPT did especially poorly on ophthalmology specialty questions (it got 80% of general medicine questions right), but still, the jump in quality after just a month is ... concerning. It’s not like an AI will forget things. That score can only go up, and it’ll go up faster than you think.

“Sure, the robot is smart,” the doctors out there are thinking, “but how can an AI compete with human compassion, understanding, and bedside manner?”

And they’d be right. When it comes to bedside manner, there’s no competition between man and bot. ChatGPT is already winning.

In another study, researchers sampled nearly 200 questions from the subreddit r/AskDocs, which received verified physician responses. The researchers fed ChatGPT the questions – without the doctor’s answer – and a panel of health care professionals evaluated both the human doctor and ChatGPT in terms of quality and empathy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the robot did better when it came to quality, providing a high-quality response 79% of the time, versus 22% for the human. But empathy? It was a bloodbath. ChatGPT provided an empathetic or very empathetic response 45% of the time, while humans could only do so 4.6% of the time. So much for bedside manner.

The researchers were suspiciously quick to note that ChatGPT isn’t a legitimate replacement for physicians, but could represent a tool to better provide care for patients. But let’s be honest, given ChatGPT’s quick advancement, how long before some intrepid stockholder says: “Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?” We give it a week. Or 11 minutes.

This week, on ‘As the sperm turns’

We’ve got a lot of spermy ground to cover, so let’s get right to it, starting with the small and working our way up.

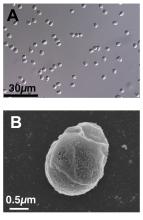

We’re all pretty familiar with the basic structure of a sperm cell, yes? Bulbous head that contains all the important genetic information and a tail-like flagellum to propel it to its ultimate destination. Not much to work with there, you’d think, but what if Mother Nature, who clearly has a robust sense of humor, had something else in mind?

We present exhibit A, Paramormyorps kingsleyae, also known as the electric elephantfish, which happens to be the only known vertebrate species with tailless sperm. Sounds crazy to us, too, but Jason Gallant, PhD, of

Michigan State University, Lansing, has a theory: “A general notion in biology is that sperm are cheap, and eggs are expensive – but these fish may be telling us that sperm are more expensive than we might think. They could be saving energy by cutting back on sperm tails.”

He and his team think that finding the gene that turns off development of the flagellum in the elephant fish could benefit humans, specifically those with a genetic disorder called primary ciliary dyskinesia, whose lack of normally functioning cilia and flagella leads to chronic respiratory infection, abnormally positioned organs, fluid on the brain, and infertility.

And that – with “that” being infertility – brings us to exhibit B, a 41-year-old Dutch man named Jonathan Meijer who clearly has too much time on his hands.

A court in the Netherlands recently ordered him, and not for the first time, to stop donating sperm to fertility clinics after it was discovered that he had fathered between 500 and 600 children around the world. He had been banned from donating to Dutch clinics in 2017, at which point he had already fathered 100 children, but managed a workaround by donating internationally and online, sometimes using another name.

The judge ordered Mr. Meijer to contact all of the clinics abroad and ask them to destroy any of his sperm they still had in stock and threatened to fine him over $100,000 for each future violation.

Okay, so here’s the thing. We have been, um, let’s call it ... warned, about the evils of tastelessness in journalism, so we’re going to do what Mr. Meijer should have done and abstain. And we can last for longer than 11 minutes.

The realm of lost luggage and lost sleep

It may be convenient to live near an airport if you’re a frequent flyer, but it really doesn’t help your sleep numbers.

The first look at how such a common sound affects sleep duration showed that people exposed to even 45 decibels of airplane noise were less likely to get the 7-9 hours of sleep needed for healthy functioning, investigators said in Environmental Health Perspectives.

How loud is 45 dB exactly? A normal conversation is about 50 dB, while a whisper is 30 dB, to give you an idea. Airplane noise at 45 dB? You might not even notice it amongst the other noises in daily life.

The researchers looked at data from about 35,000 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study who live around 90 major U.S. airports. They examined plane noise every 5 years between 1995 and 2005, focusing on estimates of nighttime and daytime levels. Short sleep was most common among the nurses who lived on the West Coast, near major cargo airports or large bodies of water, and also among those who reported no hearing loss.

The investigators noted, however, that there was no consistent association between airplane noise and quality of sleep and stopped short of making any policy recommendations. Still, sleep is a very important, yet slept-on (pun intended) factor for our overall health, so it’s good to know if anything has the potential to cause disruption.

Caution: Robotic uprisings in the rearview mirror are closer than they appear

ChatGPT. If you’ve been even in the proximity of the Internet lately, you may have heard of it. It’s quite an incredible piece of technology, an artificial intelligence that really could up-end a lot of industries. And lest doctors believe they’re safe from robotic replacement, consider this: ChatGPT took a test commonly used as a study resource by ophthalmologists and scored a 46%. Obviously, that’s not a passing grade. Job safe, right?

A month later, the researchers tried again. This time, ChatGPT got a 58%. Still not passing, and ChatGPT did especially poorly on ophthalmology specialty questions (it got 80% of general medicine questions right), but still, the jump in quality after just a month is ... concerning. It’s not like an AI will forget things. That score can only go up, and it’ll go up faster than you think.

“Sure, the robot is smart,” the doctors out there are thinking, “but how can an AI compete with human compassion, understanding, and bedside manner?”

And they’d be right. When it comes to bedside manner, there’s no competition between man and bot. ChatGPT is already winning.

In another study, researchers sampled nearly 200 questions from the subreddit r/AskDocs, which received verified physician responses. The researchers fed ChatGPT the questions – without the doctor’s answer – and a panel of health care professionals evaluated both the human doctor and ChatGPT in terms of quality and empathy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the robot did better when it came to quality, providing a high-quality response 79% of the time, versus 22% for the human. But empathy? It was a bloodbath. ChatGPT provided an empathetic or very empathetic response 45% of the time, while humans could only do so 4.6% of the time. So much for bedside manner.

The researchers were suspiciously quick to note that ChatGPT isn’t a legitimate replacement for physicians, but could represent a tool to better provide care for patients. But let’s be honest, given ChatGPT’s quick advancement, how long before some intrepid stockholder says: “Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?” We give it a week. Or 11 minutes.

This week, on ‘As the sperm turns’

We’ve got a lot of spermy ground to cover, so let’s get right to it, starting with the small and working our way up.

We’re all pretty familiar with the basic structure of a sperm cell, yes? Bulbous head that contains all the important genetic information and a tail-like flagellum to propel it to its ultimate destination. Not much to work with there, you’d think, but what if Mother Nature, who clearly has a robust sense of humor, had something else in mind?

We present exhibit A, Paramormyorps kingsleyae, also known as the electric elephantfish, which happens to be the only known vertebrate species with tailless sperm. Sounds crazy to us, too, but Jason Gallant, PhD, of

Michigan State University, Lansing, has a theory: “A general notion in biology is that sperm are cheap, and eggs are expensive – but these fish may be telling us that sperm are more expensive than we might think. They could be saving energy by cutting back on sperm tails.”

He and his team think that finding the gene that turns off development of the flagellum in the elephant fish could benefit humans, specifically those with a genetic disorder called primary ciliary dyskinesia, whose lack of normally functioning cilia and flagella leads to chronic respiratory infection, abnormally positioned organs, fluid on the brain, and infertility.

And that – with “that” being infertility – brings us to exhibit B, a 41-year-old Dutch man named Jonathan Meijer who clearly has too much time on his hands.

A court in the Netherlands recently ordered him, and not for the first time, to stop donating sperm to fertility clinics after it was discovered that he had fathered between 500 and 600 children around the world. He had been banned from donating to Dutch clinics in 2017, at which point he had already fathered 100 children, but managed a workaround by donating internationally and online, sometimes using another name.

The judge ordered Mr. Meijer to contact all of the clinics abroad and ask them to destroy any of his sperm they still had in stock and threatened to fine him over $100,000 for each future violation.

Okay, so here’s the thing. We have been, um, let’s call it ... warned, about the evils of tastelessness in journalism, so we’re going to do what Mr. Meijer should have done and abstain. And we can last for longer than 11 minutes.

The realm of lost luggage and lost sleep

It may be convenient to live near an airport if you’re a frequent flyer, but it really doesn’t help your sleep numbers.

The first look at how such a common sound affects sleep duration showed that people exposed to even 45 decibels of airplane noise were less likely to get the 7-9 hours of sleep needed for healthy functioning, investigators said in Environmental Health Perspectives.

How loud is 45 dB exactly? A normal conversation is about 50 dB, while a whisper is 30 dB, to give you an idea. Airplane noise at 45 dB? You might not even notice it amongst the other noises in daily life.

The researchers looked at data from about 35,000 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study who live around 90 major U.S. airports. They examined plane noise every 5 years between 1995 and 2005, focusing on estimates of nighttime and daytime levels. Short sleep was most common among the nurses who lived on the West Coast, near major cargo airports or large bodies of water, and also among those who reported no hearing loss.

The investigators noted, however, that there was no consistent association between airplane noise and quality of sleep and stopped short of making any policy recommendations. Still, sleep is a very important, yet slept-on (pun intended) factor for our overall health, so it’s good to know if anything has the potential to cause disruption.

Caution: Robotic uprisings in the rearview mirror are closer than they appear

ChatGPT. If you’ve been even in the proximity of the Internet lately, you may have heard of it. It’s quite an incredible piece of technology, an artificial intelligence that really could up-end a lot of industries. And lest doctors believe they’re safe from robotic replacement, consider this: ChatGPT took a test commonly used as a study resource by ophthalmologists and scored a 46%. Obviously, that’s not a passing grade. Job safe, right?

A month later, the researchers tried again. This time, ChatGPT got a 58%. Still not passing, and ChatGPT did especially poorly on ophthalmology specialty questions (it got 80% of general medicine questions right), but still, the jump in quality after just a month is ... concerning. It’s not like an AI will forget things. That score can only go up, and it’ll go up faster than you think.

“Sure, the robot is smart,” the doctors out there are thinking, “but how can an AI compete with human compassion, understanding, and bedside manner?”

And they’d be right. When it comes to bedside manner, there’s no competition between man and bot. ChatGPT is already winning.

In another study, researchers sampled nearly 200 questions from the subreddit r/AskDocs, which received verified physician responses. The researchers fed ChatGPT the questions – without the doctor’s answer – and a panel of health care professionals evaluated both the human doctor and ChatGPT in terms of quality and empathy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the robot did better when it came to quality, providing a high-quality response 79% of the time, versus 22% for the human. But empathy? It was a bloodbath. ChatGPT provided an empathetic or very empathetic response 45% of the time, while humans could only do so 4.6% of the time. So much for bedside manner.

The researchers were suspiciously quick to note that ChatGPT isn’t a legitimate replacement for physicians, but could represent a tool to better provide care for patients. But let’s be honest, given ChatGPT’s quick advancement, how long before some intrepid stockholder says: “Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?” We give it a week. Or 11 minutes.

This week, on ‘As the sperm turns’

We’ve got a lot of spermy ground to cover, so let’s get right to it, starting with the small and working our way up.

We’re all pretty familiar with the basic structure of a sperm cell, yes? Bulbous head that contains all the important genetic information and a tail-like flagellum to propel it to its ultimate destination. Not much to work with there, you’d think, but what if Mother Nature, who clearly has a robust sense of humor, had something else in mind?

We present exhibit A, Paramormyorps kingsleyae, also known as the electric elephantfish, which happens to be the only known vertebrate species with tailless sperm. Sounds crazy to us, too, but Jason Gallant, PhD, of

Michigan State University, Lansing, has a theory: “A general notion in biology is that sperm are cheap, and eggs are expensive – but these fish may be telling us that sperm are more expensive than we might think. They could be saving energy by cutting back on sperm tails.”

He and his team think that finding the gene that turns off development of the flagellum in the elephant fish could benefit humans, specifically those with a genetic disorder called primary ciliary dyskinesia, whose lack of normally functioning cilia and flagella leads to chronic respiratory infection, abnormally positioned organs, fluid on the brain, and infertility.

And that – with “that” being infertility – brings us to exhibit B, a 41-year-old Dutch man named Jonathan Meijer who clearly has too much time on his hands.

A court in the Netherlands recently ordered him, and not for the first time, to stop donating sperm to fertility clinics after it was discovered that he had fathered between 500 and 600 children around the world. He had been banned from donating to Dutch clinics in 2017, at which point he had already fathered 100 children, but managed a workaround by donating internationally and online, sometimes using another name.

The judge ordered Mr. Meijer to contact all of the clinics abroad and ask them to destroy any of his sperm they still had in stock and threatened to fine him over $100,000 for each future violation.

Okay, so here’s the thing. We have been, um, let’s call it ... warned, about the evils of tastelessness in journalism, so we’re going to do what Mr. Meijer should have done and abstain. And we can last for longer than 11 minutes.

The realm of lost luggage and lost sleep

It may be convenient to live near an airport if you’re a frequent flyer, but it really doesn’t help your sleep numbers.

The first look at how such a common sound affects sleep duration showed that people exposed to even 45 decibels of airplane noise were less likely to get the 7-9 hours of sleep needed for healthy functioning, investigators said in Environmental Health Perspectives.

How loud is 45 dB exactly? A normal conversation is about 50 dB, while a whisper is 30 dB, to give you an idea. Airplane noise at 45 dB? You might not even notice it amongst the other noises in daily life.

The researchers looked at data from about 35,000 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study who live around 90 major U.S. airports. They examined plane noise every 5 years between 1995 and 2005, focusing on estimates of nighttime and daytime levels. Short sleep was most common among the nurses who lived on the West Coast, near major cargo airports or large bodies of water, and also among those who reported no hearing loss.

The investigators noted, however, that there was no consistent association between airplane noise and quality of sleep and stopped short of making any policy recommendations. Still, sleep is a very important, yet slept-on (pun intended) factor for our overall health, so it’s good to know if anything has the potential to cause disruption.

CPAP not only solution for sleep apnea

Although continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines are the gold standard in the management of sleep apnea, several other treatments should be considered.

“Just because you have a hammer doesn’t mean everything is a nail,” Kimberly Hardin, MD, professor of clinical internal medicine at University of California, Davis, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

“Sleep has been underestimated in the health arena for many, many years,” said Dr. Hardin, who likened sound sleep to the “sixth vital sign.” “We know that sleep plays an integral role in our health.”

Surgical options include nasal surgery and maxillomandibular advancement surgery, also known as double-jaw surgery. Such procedures should be considered only for patients who are unwilling or unable to use CPAP or other nonsurgical treatments.

Sleep apnea occurs in 4% of adult men and 2% of adult women aged 30-60. Most commonly, obstructive sleep apnea involves the cessation or significant decrease in airflow while sleeping. The Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) is the number of times a patient experiences apnea or hypopnea during one night divided by the hours of sleep. Normal sleep AHI is fewer than five events per hour on average; mild sleep apnea is five to 14 events; moderate, 15-29; and severe, at least 30 events.

To identify sleep apnea, physicians have several tools at their disposal, starting with preliminary questionnaires that query patients as to whether they are having trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or are tired during the day. Additional assessment tools include sleep lab testing and at-home testing.

At-home testing has come to include more than the common devices that are worn around the chest and nose for a night.

“It’s not very fun looking,” Dr. Hardin said of the weighty, obtrusive monitoring devices. “So lots of folks have come up with some new ways of doing things.”

These new options incorporate headbands, wrist and finger devices, arterial tonometry, and sleep rings.

Studies show that U.S. adults do not get enough sleep, and poor-quality sleep is as inadequate as insufficient sleep. Barely a third of adults get the minimum 7 hours recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Non-Hispanic Black adults are less likely to report sleeping 7-9 hours and are more likely to report sleeping 6 or fewer hours than are non-Hispanic White and Hispanic adults.

Dr. Hardin said doctors can advise patients to keep their bedrooms quiet, dark, and cool with no TVs or electronics, to maintain regular wake and sleep times, and to stop consuming caffeine late in the day.

Insufficient or poor sleep can have wide-ranging implications on medical conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, obesity, immunodeficiency, cognitive function, mental health, and, ultimately, mortality, according to Dr. Hardin.

“Some people say, ‘Oh, never mind, I can sleep when I’m dead,’ “ Dr. Hardin said. But such a mentality can have a bearing on life expectancy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines are the gold standard in the management of sleep apnea, several other treatments should be considered.

“Just because you have a hammer doesn’t mean everything is a nail,” Kimberly Hardin, MD, professor of clinical internal medicine at University of California, Davis, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

“Sleep has been underestimated in the health arena for many, many years,” said Dr. Hardin, who likened sound sleep to the “sixth vital sign.” “We know that sleep plays an integral role in our health.”

Surgical options include nasal surgery and maxillomandibular advancement surgery, also known as double-jaw surgery. Such procedures should be considered only for patients who are unwilling or unable to use CPAP or other nonsurgical treatments.

Sleep apnea occurs in 4% of adult men and 2% of adult women aged 30-60. Most commonly, obstructive sleep apnea involves the cessation or significant decrease in airflow while sleeping. The Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) is the number of times a patient experiences apnea or hypopnea during one night divided by the hours of sleep. Normal sleep AHI is fewer than five events per hour on average; mild sleep apnea is five to 14 events; moderate, 15-29; and severe, at least 30 events.

To identify sleep apnea, physicians have several tools at their disposal, starting with preliminary questionnaires that query patients as to whether they are having trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or are tired during the day. Additional assessment tools include sleep lab testing and at-home testing.

At-home testing has come to include more than the common devices that are worn around the chest and nose for a night.

“It’s not very fun looking,” Dr. Hardin said of the weighty, obtrusive monitoring devices. “So lots of folks have come up with some new ways of doing things.”

These new options incorporate headbands, wrist and finger devices, arterial tonometry, and sleep rings.

Studies show that U.S. adults do not get enough sleep, and poor-quality sleep is as inadequate as insufficient sleep. Barely a third of adults get the minimum 7 hours recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Non-Hispanic Black adults are less likely to report sleeping 7-9 hours and are more likely to report sleeping 6 or fewer hours than are non-Hispanic White and Hispanic adults.

Dr. Hardin said doctors can advise patients to keep their bedrooms quiet, dark, and cool with no TVs or electronics, to maintain regular wake and sleep times, and to stop consuming caffeine late in the day.

Insufficient or poor sleep can have wide-ranging implications on medical conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, obesity, immunodeficiency, cognitive function, mental health, and, ultimately, mortality, according to Dr. Hardin.

“Some people say, ‘Oh, never mind, I can sleep when I’m dead,’ “ Dr. Hardin said. But such a mentality can have a bearing on life expectancy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines are the gold standard in the management of sleep apnea, several other treatments should be considered.

“Just because you have a hammer doesn’t mean everything is a nail,” Kimberly Hardin, MD, professor of clinical internal medicine at University of California, Davis, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

“Sleep has been underestimated in the health arena for many, many years,” said Dr. Hardin, who likened sound sleep to the “sixth vital sign.” “We know that sleep plays an integral role in our health.”

Surgical options include nasal surgery and maxillomandibular advancement surgery, also known as double-jaw surgery. Such procedures should be considered only for patients who are unwilling or unable to use CPAP or other nonsurgical treatments.

Sleep apnea occurs in 4% of adult men and 2% of adult women aged 30-60. Most commonly, obstructive sleep apnea involves the cessation or significant decrease in airflow while sleeping. The Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) is the number of times a patient experiences apnea or hypopnea during one night divided by the hours of sleep. Normal sleep AHI is fewer than five events per hour on average; mild sleep apnea is five to 14 events; moderate, 15-29; and severe, at least 30 events.

To identify sleep apnea, physicians have several tools at their disposal, starting with preliminary questionnaires that query patients as to whether they are having trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or are tired during the day. Additional assessment tools include sleep lab testing and at-home testing.

At-home testing has come to include more than the common devices that are worn around the chest and nose for a night.

“It’s not very fun looking,” Dr. Hardin said of the weighty, obtrusive monitoring devices. “So lots of folks have come up with some new ways of doing things.”

These new options incorporate headbands, wrist and finger devices, arterial tonometry, and sleep rings.

Studies show that U.S. adults do not get enough sleep, and poor-quality sleep is as inadequate as insufficient sleep. Barely a third of adults get the minimum 7 hours recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Non-Hispanic Black adults are less likely to report sleeping 7-9 hours and are more likely to report sleeping 6 or fewer hours than are non-Hispanic White and Hispanic adults.

Dr. Hardin said doctors can advise patients to keep their bedrooms quiet, dark, and cool with no TVs or electronics, to maintain regular wake and sleep times, and to stop consuming caffeine late in the day.

Insufficient or poor sleep can have wide-ranging implications on medical conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, obesity, immunodeficiency, cognitive function, mental health, and, ultimately, mortality, according to Dr. Hardin.

“Some people say, ‘Oh, never mind, I can sleep when I’m dead,’ “ Dr. Hardin said. But such a mentality can have a bearing on life expectancy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2023

Erratic sleep, lack of activity tied to worsening schizophrenia symptoms

The findings also showed that people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs) who lived in residential facilities experienced rigid routines, which correlated with a higher degree of negative symptoms.

The rigid routines were problematic for the patients living in residential settings, lead investigator Fabio Ferrarelli, MD, PhD, told this news organization. Dr. Ferrarelli is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh.

“Engaging in different activities at different times in activities associated with motivation and social interaction – this helps to ameliorate difficult-to-treat negative symptoms,” he said.

The findings were published online in Molecular Psychiatry.

Need to increase activity levels

While there is no shortage of research on sleep disturbances among people with schizophrenia, research focusing specifically on rest-activity rhythm disturbances and their relationships to symptoms of schizophrenia has been limited by small sample sizes or the lack of a control group, the investigators note.

To address this research gap, the investigators recruited 230 patients with SSD from participating residential facilities and communities throughout Italy. The participants included 108 healthy control participants, 54 community-dwelling patients with SSD who were receiving outpatient services, and 68 patients with SSD who were living in residential facilities.

All participants wore an actigraph for 7 consecutive days so that investigators could monitor sleep-wake patterns.

Compared with healthy control participants, both SSD groups had more total sleep time and spent more time resting or being passive (P < .001). In contrast, healthy control participants were much more active.

Part of the explanation for this may be that most of the control participants had jobs or attended school. In addition, the investigators note that many medications used to treat SSD can be highly sedating, causing some patients to sleep up to 15 hours per day.

Among residential participants with SSD, there was a higher level of inter-daily stability and higher daily rest-activity-rest fragmentation than occurred among healthy control participants or community-dwelling patients with SSD (P < .001). There was also a higher level of negative symptoms among residential participants with SSD than among the community-dwelling group with SSD.

When the findings were taken together, Dr. Ferrarelli and his team interpreted them to mean that inter-daily stability could reflect premature aging or neurodegenerative processes in patients with more severe forms of schizophrenia.

Another explanation could be that the rigid routine of the residential facility was making negative symptoms worse, Dr. Ferrarelli said. It is important to add variety into the mix – getting people to engage in different activities at different times of day would likely help residential SSD patients overcome negative symptoms of the disorder.

Although participants were recruited in Italy, Dr. Ferrarelli said he believes the findings are generalizable.

Bidirectional relationship?

Commenting on the findings, Matcheri Keshavan, MD, professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School in Boston, said the results are consistent with “well-known clinical observations that SSD patients tend to spend more time in bed and have more dysregulated sleep.

“Negative symptoms are also common, especially in residential patients. However, it is difficult to determine causality, as we do not know whether excessive sleepiness and decreased physical activity cause negative symptoms, or vice versa, or whether this is a bidirectional relationship,” Dr. Keshavan said.

He emphasized that physical exercise is known to increase sleep quality for people with mental illness and may also improve negative symptoms. “A useful approach in clinical practice is to increase activity levels, especially physical activities like walking and gardening.”

Dr. Keshavan said he would like to see future research that focuses on whether an intervention such as aerobic exercise would improve sleep quality as well as negative symptoms.

He also said that future research should ideally examine the characteristics of sleep alterations in schizophrenia.