User login

Dozing off: Examining excessive daytime sleepiness in psychiatric patients

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is “the inability to maintain wakefulness and alertness during the major waking periods of the day, with sleep occurring unintentionally or at inappropriate times, almost daily for at least 3 months,” according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.1 EDS is common, with a prevalence up to 25% to 30% in the general population.1-4 The prevalence rate varies in different studies, primarily because of inconsistent definitions of EDS, and therefore differences in diagnosis and assessment.1,2,4 In a study of 300 psychiatric outpatients, 34% had EDS.3 However, studies and evidence reviewing EDS in psychiatric patients are limited.

The causes of EDS are many and varied,1,8 including medical and psychiatric etiologies. A thorough history, screening at-risk patients, and timely sleep center referral are vital to detect and appropriately manage the cause of EDS.5

This article reviews the literature on EDS, with a focus on the risks of untreated EDS, common etiologies of the condition, as well as a brief description of screening and treatment strategies.

EDS vs fatigue

Many patients describe EDS as “fatigue”1; however, a patient’s report of fatigue could be mistaken for EDS.4 Although there is overlap, it is important for physicians to distinguish between these 2 entities for accurate identification and treatment.1,4

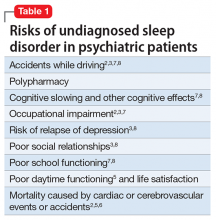

Risk of inadequate screening

A study of 117 patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease showed that EDS is associated with significantly greater incidence of cardiovascular adverse events at 16-month follow up.2 This study had limitations such as small sample size; therefore, more studies are needed. Because of these risks, timely and accurate diagnosis not only improves the patient’s quality of life and reduces polypharmacy but also can be life-saving.

Common causes of EDS in psychiatric patients

Because of the high prevalence and severity of impairments caused by EDS, it is essential for psychiatrists to be informed about causes of EDS and thoroughly assess for the potential underlying etiology before concluding that the sleep problem is a manifestation of the psychiatric disorder and prescribing psychotropic medication for it.

Some common causes of EDS in psychiatric patients include:

Sleep-disordered breathing.8 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is often underdiagnosed,6,7 and considering how common it is,6 psychiatrists likely will see many patients with OSA in their practice.5 OSA has a higher prevalence among patients with psychiatric disorders such as depression6,9 and schizophrenia. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that patients with OSA are more likely to suffer from depression and EDS than healthy controls6,9,10; some of the proposed mechanisms are sleep fragmentation and hypoxemia.6,9-11 OSA is the most common form of sleep-disordered breathing and is a common cause of EDS.1,2,12 Also, undiagnosed and untreated OSA in patients with depression could cause refractoriness to pharmacological treatment of depression.6,9,10

When unrecognized and untreated, OSA can be life-threatening. Despite this, OSA is not regularly screened for in clinical psychiatric practice.6,10 Therefore, it is imperative that psychiatrists be well-acquainted with measures to identify at-risk patients and refer to a sleep specialist when appropriate.

OSA is accompanied by irritability, cognitive difficulties, and poor sleep, creating an overlap with symptoms of depressive disorders.6,10 Use of sedative hypnotic medications, such as benzodiazepines, which further reduces muscle tone in the airway and suppresses respiratory effort, can worsen OSA symptoms5,6,10 and pose cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, and potentially life-threatening risks, and therefore is not indicated in this population.9,13

Obesity is a risk factor for OSA.6 Patients with mood disorders or schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders are at higher risk of obesity because of psychotropic-induced weight gain, stress-induced mechanisms, and/or lower levels of self-care. When these patients have unrecognized or untreated OSA and are prescribed sedative medications at night or stimulant medications during the day, they could be at increased cardiac or respiratory risks without resolving their underlying condition. A diligent psychiatrist can dramatically reduce the risks by referring a patient for nocturnal polysomnography,1 helping the patient implement lifestyle modifications (eg, exercise, weight loss, and healthy nutrition), prescribing judiciously, and monitoring closely for such risks. An accurate diagnosis of and treatment for OSA can improve sleep6 dramatically and help depressive symptoms through better sleep, more daytime energy and concentration, and adequate oxygenation of the brain while sleeping.

Psychiatrists can screen for OSA using the STOP-Bang (Snoring, Tired, Observed apnea, Pressure, Body mass index, Age, Neck circumference, Gender) Questionnaire, which is a quick, 8-item screening scale that helps to categorize OSA risk as mild, moderate, or severe.12 Hypertension, snoring, and/or gasping for breath (“observed apnea”)—a history which often is provided by spouses or significant others—daytime dozing and/or tiredness, having a large neck circumference or volume, body mass index, male sex, and age are items on the STOP-Bang Questionnaire and also are features that should raise high clinical suspicion of OSA.12 Referral for nocturnal polysomnography in at-risk patients should be the next step1,5 in any sleep-related breathing disorder.

Treatment for OSA involves continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, which has been shown to relieve OSA and decrease related EDS.5,6 Other treatment modalities, such as oral appliances and surgery, may be used5 in some cases, but more studies are needed for conclusive results.

Several studies have shown improved depression, mood, and cognition after administering treatment such as CPAP6,9,14 in patients with OSA and depression. Considering the significant risks of cardiovascular,8 cerebrovascular,8 and overall morbidity and mortality associated with untreated OSA,12 it is important to routinely screen for sleep-disordered breathing in patients with depression9 or other psychiatric disorders and refer for specialized sleep evaluation and treatment, when indicated.

Medications. EDS can result from some prescription and over-the-counter medications.1,2,5,7 Sedating antidepressants, antihistamines, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants,1,8 and beta blockers2 could cause sedation, which can persist during daytime, although a few studies did not find an association between antipsychotic use and EDS.3 Benzodiazepines and other sedative-hypnotics,1,7 especially long-acting agents or higher dosages,5 can lead to EDS and decreased alertness. Non-psychotropics, such as opioid pain medications,1,7 antitussives, and skeletal muscle relaxants, also can contribute to or cause daytime sedation.7 When using these agents, psychiatrists should monitor and routinely assess patients while aiming for the lowest effective dosage when feasible.

This strategy creates a framework for psychiatrists to routinely educate patients about these commonly encountered side effects, reduce polypharmacy when possible, and help patients effectively manage or prevent these adverse effects.

Depression.1 Some studies found >45% patients with depression had EDS.3,13,15 Besides an association between depression and EDS,13,16 Chellappa and Araújo13 also found a significant association between EDS and suicidal ideation. The causes of EDS in patients with depression may be varied, ranging from restless legs syndrome, residual depressive symptoms,15 to OSA. Depression is often comorbid with OSA,6 with up to 20% of patients with depression suffering from OSA,10 creating higher risk for EDS. Depressive disorders are routinely assessed during an evaluation of OSA at sleep centers, but OSA often is not screened in psychiatric practice.10

There is a strong need for regular screening for OSA in patients with depression, particularly because most studies show a link between the 2 conditions.10 Both depression and OSA have some common risk factors, such as obesity, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome.10 Patients with these conditions are at greater risk for OSA, and therefore a psychiatrist should proactively screen and refer such patients for nocturnal polysomnography when they suspect OSA. Patients with OSA and depression often present to the psychiatrist with depressive symptoms that appear to be resistant to pharmacological treatment,10 therefore underscoring the importance of screening and ruling out OSA in patients with depression.

Circadian rhythm disorders, restless legs syndrome, alcohol and other substance use, and use of prescription sedative-hypnotics are more common in patients with depression; therefore, this population is at high risk for EDS.

Circadian rhythm disorders and insufficient sleep syndrome. Insufficient sleep syndrome1,2,8 frequently causes EDS and occurs more commonly in busy people who try to get by with less sleep.8 Over time, the effect of sleep loss is cumulative and can be accompanied by mood symptoms, such as irritability, fatigue, and problems with concentration.8 Shift workers1,8 commonly experience insufficient sleep as well as circadian rhythm disorders and EDS. Modafinil is FDA-approved for EDS in shift work sleep disorder.

Geriatric patients may experience advanced sleep phase syndrome involving early awakenings.8 Adolescents, on the other hand, often suffer from delayed sleep phase syndrome, which is a type of circadian rhythm disorder, related to increasing academic and social pressures, natural pubertal shift to later sleep onset, pervading technology use, and often nebulous bedtime routines. This can be a cause of sleep persisting into daytime.8 Taking a careful history and a sleep diary may be useful because this disorder might be confused for insomnia. Treatment involves gradual shifting of the time of sleep onset through bright light exposure and other modalities.8

Adolescents might not be forthcoming about the severity of their sleep problems; therefore, psychiatrists should screen proactively through clinical interviews of patients and parents and consider this possibility when encountering an adolescent with recent-onset attention or cognitive difficulties.

Treatment for circadian rhythm disorders usually includes planned or prescribed sleep scheduling, timed light exposure,8 and occasional use of melatonin or other sedative agents.17

Hypersomnia of central origin, which includes narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia, and recurrent hypersomnia, can present with EDS.1,18,19 Narcolepsy is a rare, debilitating sleep disorder that manifests as EDS or sleep attacks, with or without cataplexy, and sleep paralysis.5,8,18,19 The Multiple Sleep Latency Test and polysomnography are used for diagnosis.1,5 Shortened REM latency is a classic finding often noted on polysomnography. Treatment involves pharmacologic and behavioral strategies and education.5,8 Modafinil is FDA-approved for EDS associated with narcolepsy. Stimulant medications have been used for narcolepsy in the past; further studies are needed to establish benefit–risk ratio of use in this population.18

Kleine-Levin syndrome is a form of recurrent hypersomnia, a less common sleep disorder, characterized by episodes of excessive sleepiness accompanied by hyperphagia and hypersexuality.5,18,19

Other medical conditions,1 such as the rare familial fatal insomnia, neurological conditions1 such as encephalitis,8 epilepsy,8 Alzheimer’s disease or other types of dementia,8 Parkinson’s disease,1 or multiple sclerosis,1,18 can cause excessive daytime fatigue by causing secondary insomnia or hypersomnia.

Treating the underlying disorder is an important first step in these cases. In addition, coordinating with neurologists or other specialists involved in caring for patients with these conditions is important. Regularly reviewing and simplifying the often complex medication regimen, when possible, can go a long way in mitigating EDS in this population.

Other disorders affecting sleep. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder are other causes of EDS.3 Treatment involves lifestyle modifications, iron supplementation in certain patients, and use of dopaminergic agents such as ropinirole, pramipexole, and other medications, depending on severity of the condition, comorbidities, and other factors.20

Alcohol or substance use. Substance use or withdrawal can be associated with sleep disorders, such as hypersomnia,19 insomnia,19 and related EDS.5 For example, alcohol use disorder affects REM sleep, and can cause EDS. Secondary central apnea can be the result of long-standing opioid use19 and can present like EDS.

Insomnia. Primary insomnia rarely causes EDS.5 Insomnia due to a medical or psychiatric condition may be an indirect cause of EDS by causing sleep deprivation.

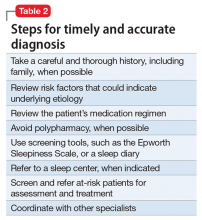

Steps for timely and accurate diagnosis

Utilize the following steps for facilitating timely diagnosis and treatment of EDS:

Thorough history. Patients often describe “tiredness” instead of sleepiness.8 Therefore, the astute psychiatrist should explore further when patients are presenting with this concern, especially by asking more specific questions such as the tendency to doze off during daytime.8

Family members can be vital sources for obtaining a complete history,5 especially because patients might deny,8 minimize, or not be fully aware1 of the extent of their symptoms. Asking family members about patient’s snoring, irregular breathing, or gasping at night can be particularly valuable.5 Obtaining a family history of sleep disorders can be particularly important, especially in conditions such as OSA and narcolepsy.

Asking about any history of safety issues,8 including sleepiness during driving, cooking, or other activities, is also important.

Use of scales and other screening measures. Psychiatrists can use initial screening measures in the office setting. Epworth Sleepiness Scale15,21 is a validated,2 short, self-administered measure to assess the level of daytime sleepiness; however, it has some limitations such as not being able to measure changes in sleepiness from hour to hour or day to day. Because of its limitations, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale should not be used by itself as a diagnostic tool.3 It has been commonly used for detecting OSA2 and narcolepsy. The Stanford Sleepiness Scale is a self-rating scale that measures the subjective degree of sleepiness and alertness; it has limitations as well, such as having little correlation with chronic sleep loss.8 Other tools such as visual analogue scales also could be helpful.8 For more specialized testing, such as Multiple Sleep Latency Test or polysomnography, referral to a sleep specialist is ideal.8

Education. The assessment is an opportunity for the psychiatrist to educate patients about sleep hygiene, the importance of regular bedtimes, and getting adequate sleep to avoid accumulating a sleep deficit.

Urgent referral of at-risk populations. Prompt or urgent referral of at-risk populations, such as geriatric patients or those with a history of dozing off during driving, is invaluable in preventing morbidity and mortality from untreated sleep disorders.

Patients with severe daytime sleepiness should be advised to not drive or operate heavy machinery until this condition is adequately controlled.18

Bottom Line

1. Chervin RD. Approach to the patient with excessive daytime sleepiness. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-excessive-daytime-sleepiness. Updated January 2016. Accessed June 5, 2017.

2. Lee CH, Ng WY, Hau W, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness is associated with longer culprit lesion and adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(12):1267-1272.

3. Hawley CJ, Gale TM, Sivakumaran T, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in psychiatric disorders: prevalence, correlates and clinical significance. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(1-2):138-141.

4. Pigeon WR, Sateia MJ, Ferguson RJ. Distinguishing between excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue: toward improved detection and treatment. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(1):61-69.

5. Krahn LE. Excessive daytime sleepiness: diagnosing the causes. Current Psychiatry. 2002;1(1):49-57.

6. Ejaz SM, Khawaja IS, Bhatia S, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and depression: a review. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(8):17-25.

7. Pagel JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(5):391-396.

8. Guilleminault C, Brooks SN. Excessive daytime sleepiness: a challenge for the practising neurologist. Brain. 2001;124(pt 8):1482-1491.

9. Cheng P, Casement M, Chen CF, et al. Sleep disordered breathing in major depressive disorder. J Sleep Res. 2013;22(4):459-462.

10. Schröder CM, O’Hara R. Depression and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2005;4:13.

11. Bardwell WA, Berry CC, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Psychological correlates of sleep apnea. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47(6):583-596.

12. Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-Bang Questionnaire: a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2016;149(3):631-638.

13. Chellappa SL, Araújo JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with depressive disorder. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28(2):126-129.

14. Habukawa M, Uchimura N, Kakuma T, et al. Effect of CPAP treatment on residual depressive symptoms in patients with major depression and coexisting sleep apnea: contribution of daytime sleepiness to residual depressive symptoms. Sleep Med. 2010;11(6):552-557.

15. Lundt L. Use of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale to evaluate the symptom of excessive sleepiness in major depressive disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27(2):146-148.

16. Hawley CJ. Excessive daytime sleepiness in psychiatry: a relevant focus for clinical attention and treatment? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2006;10(2):117-123.

17. Dodson ER, Zee PC. Therapeutics for circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Sleep Med Clin. 2010;5(4):701-715.

18. Morgenthaler TI, Kapur VK, Brown TM, et al; Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for the treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin. Sleep. 2007;30(12):1705-1711.

19. Thorpy MJ. Classification of sleep disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(4):687-701.

20. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Restless legs syndrome information page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Restless-Legs-Syndrome-Information-Page. Accessed June 2, 2017.

21. Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1992;15(4):376-381.

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is “the inability to maintain wakefulness and alertness during the major waking periods of the day, with sleep occurring unintentionally or at inappropriate times, almost daily for at least 3 months,” according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.1 EDS is common, with a prevalence up to 25% to 30% in the general population.1-4 The prevalence rate varies in different studies, primarily because of inconsistent definitions of EDS, and therefore differences in diagnosis and assessment.1,2,4 In a study of 300 psychiatric outpatients, 34% had EDS.3 However, studies and evidence reviewing EDS in psychiatric patients are limited.

The causes of EDS are many and varied,1,8 including medical and psychiatric etiologies. A thorough history, screening at-risk patients, and timely sleep center referral are vital to detect and appropriately manage the cause of EDS.5

This article reviews the literature on EDS, with a focus on the risks of untreated EDS, common etiologies of the condition, as well as a brief description of screening and treatment strategies.

EDS vs fatigue

Many patients describe EDS as “fatigue”1; however, a patient’s report of fatigue could be mistaken for EDS.4 Although there is overlap, it is important for physicians to distinguish between these 2 entities for accurate identification and treatment.1,4

Risk of inadequate screening

A study of 117 patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease showed that EDS is associated with significantly greater incidence of cardiovascular adverse events at 16-month follow up.2 This study had limitations such as small sample size; therefore, more studies are needed. Because of these risks, timely and accurate diagnosis not only improves the patient’s quality of life and reduces polypharmacy but also can be life-saving.

Common causes of EDS in psychiatric patients

Because of the high prevalence and severity of impairments caused by EDS, it is essential for psychiatrists to be informed about causes of EDS and thoroughly assess for the potential underlying etiology before concluding that the sleep problem is a manifestation of the psychiatric disorder and prescribing psychotropic medication for it.

Some common causes of EDS in psychiatric patients include:

Sleep-disordered breathing.8 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is often underdiagnosed,6,7 and considering how common it is,6 psychiatrists likely will see many patients with OSA in their practice.5 OSA has a higher prevalence among patients with psychiatric disorders such as depression6,9 and schizophrenia. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that patients with OSA are more likely to suffer from depression and EDS than healthy controls6,9,10; some of the proposed mechanisms are sleep fragmentation and hypoxemia.6,9-11 OSA is the most common form of sleep-disordered breathing and is a common cause of EDS.1,2,12 Also, undiagnosed and untreated OSA in patients with depression could cause refractoriness to pharmacological treatment of depression.6,9,10

When unrecognized and untreated, OSA can be life-threatening. Despite this, OSA is not regularly screened for in clinical psychiatric practice.6,10 Therefore, it is imperative that psychiatrists be well-acquainted with measures to identify at-risk patients and refer to a sleep specialist when appropriate.

OSA is accompanied by irritability, cognitive difficulties, and poor sleep, creating an overlap with symptoms of depressive disorders.6,10 Use of sedative hypnotic medications, such as benzodiazepines, which further reduces muscle tone in the airway and suppresses respiratory effort, can worsen OSA symptoms5,6,10 and pose cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, and potentially life-threatening risks, and therefore is not indicated in this population.9,13

Obesity is a risk factor for OSA.6 Patients with mood disorders or schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders are at higher risk of obesity because of psychotropic-induced weight gain, stress-induced mechanisms, and/or lower levels of self-care. When these patients have unrecognized or untreated OSA and are prescribed sedative medications at night or stimulant medications during the day, they could be at increased cardiac or respiratory risks without resolving their underlying condition. A diligent psychiatrist can dramatically reduce the risks by referring a patient for nocturnal polysomnography,1 helping the patient implement lifestyle modifications (eg, exercise, weight loss, and healthy nutrition), prescribing judiciously, and monitoring closely for such risks. An accurate diagnosis of and treatment for OSA can improve sleep6 dramatically and help depressive symptoms through better sleep, more daytime energy and concentration, and adequate oxygenation of the brain while sleeping.

Psychiatrists can screen for OSA using the STOP-Bang (Snoring, Tired, Observed apnea, Pressure, Body mass index, Age, Neck circumference, Gender) Questionnaire, which is a quick, 8-item screening scale that helps to categorize OSA risk as mild, moderate, or severe.12 Hypertension, snoring, and/or gasping for breath (“observed apnea”)—a history which often is provided by spouses or significant others—daytime dozing and/or tiredness, having a large neck circumference or volume, body mass index, male sex, and age are items on the STOP-Bang Questionnaire and also are features that should raise high clinical suspicion of OSA.12 Referral for nocturnal polysomnography in at-risk patients should be the next step1,5 in any sleep-related breathing disorder.

Treatment for OSA involves continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, which has been shown to relieve OSA and decrease related EDS.5,6 Other treatment modalities, such as oral appliances and surgery, may be used5 in some cases, but more studies are needed for conclusive results.

Several studies have shown improved depression, mood, and cognition after administering treatment such as CPAP6,9,14 in patients with OSA and depression. Considering the significant risks of cardiovascular,8 cerebrovascular,8 and overall morbidity and mortality associated with untreated OSA,12 it is important to routinely screen for sleep-disordered breathing in patients with depression9 or other psychiatric disorders and refer for specialized sleep evaluation and treatment, when indicated.

Medications. EDS can result from some prescription and over-the-counter medications.1,2,5,7 Sedating antidepressants, antihistamines, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants,1,8 and beta blockers2 could cause sedation, which can persist during daytime, although a few studies did not find an association between antipsychotic use and EDS.3 Benzodiazepines and other sedative-hypnotics,1,7 especially long-acting agents or higher dosages,5 can lead to EDS and decreased alertness. Non-psychotropics, such as opioid pain medications,1,7 antitussives, and skeletal muscle relaxants, also can contribute to or cause daytime sedation.7 When using these agents, psychiatrists should monitor and routinely assess patients while aiming for the lowest effective dosage when feasible.

This strategy creates a framework for psychiatrists to routinely educate patients about these commonly encountered side effects, reduce polypharmacy when possible, and help patients effectively manage or prevent these adverse effects.

Depression.1 Some studies found >45% patients with depression had EDS.3,13,15 Besides an association between depression and EDS,13,16 Chellappa and Araújo13 also found a significant association between EDS and suicidal ideation. The causes of EDS in patients with depression may be varied, ranging from restless legs syndrome, residual depressive symptoms,15 to OSA. Depression is often comorbid with OSA,6 with up to 20% of patients with depression suffering from OSA,10 creating higher risk for EDS. Depressive disorders are routinely assessed during an evaluation of OSA at sleep centers, but OSA often is not screened in psychiatric practice.10

There is a strong need for regular screening for OSA in patients with depression, particularly because most studies show a link between the 2 conditions.10 Both depression and OSA have some common risk factors, such as obesity, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome.10 Patients with these conditions are at greater risk for OSA, and therefore a psychiatrist should proactively screen and refer such patients for nocturnal polysomnography when they suspect OSA. Patients with OSA and depression often present to the psychiatrist with depressive symptoms that appear to be resistant to pharmacological treatment,10 therefore underscoring the importance of screening and ruling out OSA in patients with depression.

Circadian rhythm disorders, restless legs syndrome, alcohol and other substance use, and use of prescription sedative-hypnotics are more common in patients with depression; therefore, this population is at high risk for EDS.

Circadian rhythm disorders and insufficient sleep syndrome. Insufficient sleep syndrome1,2,8 frequently causes EDS and occurs more commonly in busy people who try to get by with less sleep.8 Over time, the effect of sleep loss is cumulative and can be accompanied by mood symptoms, such as irritability, fatigue, and problems with concentration.8 Shift workers1,8 commonly experience insufficient sleep as well as circadian rhythm disorders and EDS. Modafinil is FDA-approved for EDS in shift work sleep disorder.

Geriatric patients may experience advanced sleep phase syndrome involving early awakenings.8 Adolescents, on the other hand, often suffer from delayed sleep phase syndrome, which is a type of circadian rhythm disorder, related to increasing academic and social pressures, natural pubertal shift to later sleep onset, pervading technology use, and often nebulous bedtime routines. This can be a cause of sleep persisting into daytime.8 Taking a careful history and a sleep diary may be useful because this disorder might be confused for insomnia. Treatment involves gradual shifting of the time of sleep onset through bright light exposure and other modalities.8

Adolescents might not be forthcoming about the severity of their sleep problems; therefore, psychiatrists should screen proactively through clinical interviews of patients and parents and consider this possibility when encountering an adolescent with recent-onset attention or cognitive difficulties.

Treatment for circadian rhythm disorders usually includes planned or prescribed sleep scheduling, timed light exposure,8 and occasional use of melatonin or other sedative agents.17

Hypersomnia of central origin, which includes narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia, and recurrent hypersomnia, can present with EDS.1,18,19 Narcolepsy is a rare, debilitating sleep disorder that manifests as EDS or sleep attacks, with or without cataplexy, and sleep paralysis.5,8,18,19 The Multiple Sleep Latency Test and polysomnography are used for diagnosis.1,5 Shortened REM latency is a classic finding often noted on polysomnography. Treatment involves pharmacologic and behavioral strategies and education.5,8 Modafinil is FDA-approved for EDS associated with narcolepsy. Stimulant medications have been used for narcolepsy in the past; further studies are needed to establish benefit–risk ratio of use in this population.18

Kleine-Levin syndrome is a form of recurrent hypersomnia, a less common sleep disorder, characterized by episodes of excessive sleepiness accompanied by hyperphagia and hypersexuality.5,18,19

Other medical conditions,1 such as the rare familial fatal insomnia, neurological conditions1 such as encephalitis,8 epilepsy,8 Alzheimer’s disease or other types of dementia,8 Parkinson’s disease,1 or multiple sclerosis,1,18 can cause excessive daytime fatigue by causing secondary insomnia or hypersomnia.

Treating the underlying disorder is an important first step in these cases. In addition, coordinating with neurologists or other specialists involved in caring for patients with these conditions is important. Regularly reviewing and simplifying the often complex medication regimen, when possible, can go a long way in mitigating EDS in this population.

Other disorders affecting sleep. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder are other causes of EDS.3 Treatment involves lifestyle modifications, iron supplementation in certain patients, and use of dopaminergic agents such as ropinirole, pramipexole, and other medications, depending on severity of the condition, comorbidities, and other factors.20

Alcohol or substance use. Substance use or withdrawal can be associated with sleep disorders, such as hypersomnia,19 insomnia,19 and related EDS.5 For example, alcohol use disorder affects REM sleep, and can cause EDS. Secondary central apnea can be the result of long-standing opioid use19 and can present like EDS.

Insomnia. Primary insomnia rarely causes EDS.5 Insomnia due to a medical or psychiatric condition may be an indirect cause of EDS by causing sleep deprivation.

Steps for timely and accurate diagnosis

Utilize the following steps for facilitating timely diagnosis and treatment of EDS:

Thorough history. Patients often describe “tiredness” instead of sleepiness.8 Therefore, the astute psychiatrist should explore further when patients are presenting with this concern, especially by asking more specific questions such as the tendency to doze off during daytime.8

Family members can be vital sources for obtaining a complete history,5 especially because patients might deny,8 minimize, or not be fully aware1 of the extent of their symptoms. Asking family members about patient’s snoring, irregular breathing, or gasping at night can be particularly valuable.5 Obtaining a family history of sleep disorders can be particularly important, especially in conditions such as OSA and narcolepsy.

Asking about any history of safety issues,8 including sleepiness during driving, cooking, or other activities, is also important.

Use of scales and other screening measures. Psychiatrists can use initial screening measures in the office setting. Epworth Sleepiness Scale15,21 is a validated,2 short, self-administered measure to assess the level of daytime sleepiness; however, it has some limitations such as not being able to measure changes in sleepiness from hour to hour or day to day. Because of its limitations, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale should not be used by itself as a diagnostic tool.3 It has been commonly used for detecting OSA2 and narcolepsy. The Stanford Sleepiness Scale is a self-rating scale that measures the subjective degree of sleepiness and alertness; it has limitations as well, such as having little correlation with chronic sleep loss.8 Other tools such as visual analogue scales also could be helpful.8 For more specialized testing, such as Multiple Sleep Latency Test or polysomnography, referral to a sleep specialist is ideal.8

Education. The assessment is an opportunity for the psychiatrist to educate patients about sleep hygiene, the importance of regular bedtimes, and getting adequate sleep to avoid accumulating a sleep deficit.

Urgent referral of at-risk populations. Prompt or urgent referral of at-risk populations, such as geriatric patients or those with a history of dozing off during driving, is invaluable in preventing morbidity and mortality from untreated sleep disorders.

Patients with severe daytime sleepiness should be advised to not drive or operate heavy machinery until this condition is adequately controlled.18

Bottom Line

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is “the inability to maintain wakefulness and alertness during the major waking periods of the day, with sleep occurring unintentionally or at inappropriate times, almost daily for at least 3 months,” according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.1 EDS is common, with a prevalence up to 25% to 30% in the general population.1-4 The prevalence rate varies in different studies, primarily because of inconsistent definitions of EDS, and therefore differences in diagnosis and assessment.1,2,4 In a study of 300 psychiatric outpatients, 34% had EDS.3 However, studies and evidence reviewing EDS in psychiatric patients are limited.

The causes of EDS are many and varied,1,8 including medical and psychiatric etiologies. A thorough history, screening at-risk patients, and timely sleep center referral are vital to detect and appropriately manage the cause of EDS.5

This article reviews the literature on EDS, with a focus on the risks of untreated EDS, common etiologies of the condition, as well as a brief description of screening and treatment strategies.

EDS vs fatigue

Many patients describe EDS as “fatigue”1; however, a patient’s report of fatigue could be mistaken for EDS.4 Although there is overlap, it is important for physicians to distinguish between these 2 entities for accurate identification and treatment.1,4

Risk of inadequate screening

A study of 117 patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease showed that EDS is associated with significantly greater incidence of cardiovascular adverse events at 16-month follow up.2 This study had limitations such as small sample size; therefore, more studies are needed. Because of these risks, timely and accurate diagnosis not only improves the patient’s quality of life and reduces polypharmacy but also can be life-saving.

Common causes of EDS in psychiatric patients

Because of the high prevalence and severity of impairments caused by EDS, it is essential for psychiatrists to be informed about causes of EDS and thoroughly assess for the potential underlying etiology before concluding that the sleep problem is a manifestation of the psychiatric disorder and prescribing psychotropic medication for it.

Some common causes of EDS in psychiatric patients include:

Sleep-disordered breathing.8 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is often underdiagnosed,6,7 and considering how common it is,6 psychiatrists likely will see many patients with OSA in their practice.5 OSA has a higher prevalence among patients with psychiatric disorders such as depression6,9 and schizophrenia. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that patients with OSA are more likely to suffer from depression and EDS than healthy controls6,9,10; some of the proposed mechanisms are sleep fragmentation and hypoxemia.6,9-11 OSA is the most common form of sleep-disordered breathing and is a common cause of EDS.1,2,12 Also, undiagnosed and untreated OSA in patients with depression could cause refractoriness to pharmacological treatment of depression.6,9,10

When unrecognized and untreated, OSA can be life-threatening. Despite this, OSA is not regularly screened for in clinical psychiatric practice.6,10 Therefore, it is imperative that psychiatrists be well-acquainted with measures to identify at-risk patients and refer to a sleep specialist when appropriate.

OSA is accompanied by irritability, cognitive difficulties, and poor sleep, creating an overlap with symptoms of depressive disorders.6,10 Use of sedative hypnotic medications, such as benzodiazepines, which further reduces muscle tone in the airway and suppresses respiratory effort, can worsen OSA symptoms5,6,10 and pose cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, and potentially life-threatening risks, and therefore is not indicated in this population.9,13

Obesity is a risk factor for OSA.6 Patients with mood disorders or schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders are at higher risk of obesity because of psychotropic-induced weight gain, stress-induced mechanisms, and/or lower levels of self-care. When these patients have unrecognized or untreated OSA and are prescribed sedative medications at night or stimulant medications during the day, they could be at increased cardiac or respiratory risks without resolving their underlying condition. A diligent psychiatrist can dramatically reduce the risks by referring a patient for nocturnal polysomnography,1 helping the patient implement lifestyle modifications (eg, exercise, weight loss, and healthy nutrition), prescribing judiciously, and monitoring closely for such risks. An accurate diagnosis of and treatment for OSA can improve sleep6 dramatically and help depressive symptoms through better sleep, more daytime energy and concentration, and adequate oxygenation of the brain while sleeping.

Psychiatrists can screen for OSA using the STOP-Bang (Snoring, Tired, Observed apnea, Pressure, Body mass index, Age, Neck circumference, Gender) Questionnaire, which is a quick, 8-item screening scale that helps to categorize OSA risk as mild, moderate, or severe.12 Hypertension, snoring, and/or gasping for breath (“observed apnea”)—a history which often is provided by spouses or significant others—daytime dozing and/or tiredness, having a large neck circumference or volume, body mass index, male sex, and age are items on the STOP-Bang Questionnaire and also are features that should raise high clinical suspicion of OSA.12 Referral for nocturnal polysomnography in at-risk patients should be the next step1,5 in any sleep-related breathing disorder.

Treatment for OSA involves continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, which has been shown to relieve OSA and decrease related EDS.5,6 Other treatment modalities, such as oral appliances and surgery, may be used5 in some cases, but more studies are needed for conclusive results.

Several studies have shown improved depression, mood, and cognition after administering treatment such as CPAP6,9,14 in patients with OSA and depression. Considering the significant risks of cardiovascular,8 cerebrovascular,8 and overall morbidity and mortality associated with untreated OSA,12 it is important to routinely screen for sleep-disordered breathing in patients with depression9 or other psychiatric disorders and refer for specialized sleep evaluation and treatment, when indicated.

Medications. EDS can result from some prescription and over-the-counter medications.1,2,5,7 Sedating antidepressants, antihistamines, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants,1,8 and beta blockers2 could cause sedation, which can persist during daytime, although a few studies did not find an association between antipsychotic use and EDS.3 Benzodiazepines and other sedative-hypnotics,1,7 especially long-acting agents or higher dosages,5 can lead to EDS and decreased alertness. Non-psychotropics, such as opioid pain medications,1,7 antitussives, and skeletal muscle relaxants, also can contribute to or cause daytime sedation.7 When using these agents, psychiatrists should monitor and routinely assess patients while aiming for the lowest effective dosage when feasible.

This strategy creates a framework for psychiatrists to routinely educate patients about these commonly encountered side effects, reduce polypharmacy when possible, and help patients effectively manage or prevent these adverse effects.

Depression.1 Some studies found >45% patients with depression had EDS.3,13,15 Besides an association between depression and EDS,13,16 Chellappa and Araújo13 also found a significant association between EDS and suicidal ideation. The causes of EDS in patients with depression may be varied, ranging from restless legs syndrome, residual depressive symptoms,15 to OSA. Depression is often comorbid with OSA,6 with up to 20% of patients with depression suffering from OSA,10 creating higher risk for EDS. Depressive disorders are routinely assessed during an evaluation of OSA at sleep centers, but OSA often is not screened in psychiatric practice.10

There is a strong need for regular screening for OSA in patients with depression, particularly because most studies show a link between the 2 conditions.10 Both depression and OSA have some common risk factors, such as obesity, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome.10 Patients with these conditions are at greater risk for OSA, and therefore a psychiatrist should proactively screen and refer such patients for nocturnal polysomnography when they suspect OSA. Patients with OSA and depression often present to the psychiatrist with depressive symptoms that appear to be resistant to pharmacological treatment,10 therefore underscoring the importance of screening and ruling out OSA in patients with depression.

Circadian rhythm disorders, restless legs syndrome, alcohol and other substance use, and use of prescription sedative-hypnotics are more common in patients with depression; therefore, this population is at high risk for EDS.

Circadian rhythm disorders and insufficient sleep syndrome. Insufficient sleep syndrome1,2,8 frequently causes EDS and occurs more commonly in busy people who try to get by with less sleep.8 Over time, the effect of sleep loss is cumulative and can be accompanied by mood symptoms, such as irritability, fatigue, and problems with concentration.8 Shift workers1,8 commonly experience insufficient sleep as well as circadian rhythm disorders and EDS. Modafinil is FDA-approved for EDS in shift work sleep disorder.

Geriatric patients may experience advanced sleep phase syndrome involving early awakenings.8 Adolescents, on the other hand, often suffer from delayed sleep phase syndrome, which is a type of circadian rhythm disorder, related to increasing academic and social pressures, natural pubertal shift to later sleep onset, pervading technology use, and often nebulous bedtime routines. This can be a cause of sleep persisting into daytime.8 Taking a careful history and a sleep diary may be useful because this disorder might be confused for insomnia. Treatment involves gradual shifting of the time of sleep onset through bright light exposure and other modalities.8

Adolescents might not be forthcoming about the severity of their sleep problems; therefore, psychiatrists should screen proactively through clinical interviews of patients and parents and consider this possibility when encountering an adolescent with recent-onset attention or cognitive difficulties.

Treatment for circadian rhythm disorders usually includes planned or prescribed sleep scheduling, timed light exposure,8 and occasional use of melatonin or other sedative agents.17

Hypersomnia of central origin, which includes narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia, and recurrent hypersomnia, can present with EDS.1,18,19 Narcolepsy is a rare, debilitating sleep disorder that manifests as EDS or sleep attacks, with or without cataplexy, and sleep paralysis.5,8,18,19 The Multiple Sleep Latency Test and polysomnography are used for diagnosis.1,5 Shortened REM latency is a classic finding often noted on polysomnography. Treatment involves pharmacologic and behavioral strategies and education.5,8 Modafinil is FDA-approved for EDS associated with narcolepsy. Stimulant medications have been used for narcolepsy in the past; further studies are needed to establish benefit–risk ratio of use in this population.18

Kleine-Levin syndrome is a form of recurrent hypersomnia, a less common sleep disorder, characterized by episodes of excessive sleepiness accompanied by hyperphagia and hypersexuality.5,18,19

Other medical conditions,1 such as the rare familial fatal insomnia, neurological conditions1 such as encephalitis,8 epilepsy,8 Alzheimer’s disease or other types of dementia,8 Parkinson’s disease,1 or multiple sclerosis,1,18 can cause excessive daytime fatigue by causing secondary insomnia or hypersomnia.

Treating the underlying disorder is an important first step in these cases. In addition, coordinating with neurologists or other specialists involved in caring for patients with these conditions is important. Regularly reviewing and simplifying the often complex medication regimen, when possible, can go a long way in mitigating EDS in this population.

Other disorders affecting sleep. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder are other causes of EDS.3 Treatment involves lifestyle modifications, iron supplementation in certain patients, and use of dopaminergic agents such as ropinirole, pramipexole, and other medications, depending on severity of the condition, comorbidities, and other factors.20

Alcohol or substance use. Substance use or withdrawal can be associated with sleep disorders, such as hypersomnia,19 insomnia,19 and related EDS.5 For example, alcohol use disorder affects REM sleep, and can cause EDS. Secondary central apnea can be the result of long-standing opioid use19 and can present like EDS.

Insomnia. Primary insomnia rarely causes EDS.5 Insomnia due to a medical or psychiatric condition may be an indirect cause of EDS by causing sleep deprivation.

Steps for timely and accurate diagnosis

Utilize the following steps for facilitating timely diagnosis and treatment of EDS:

Thorough history. Patients often describe “tiredness” instead of sleepiness.8 Therefore, the astute psychiatrist should explore further when patients are presenting with this concern, especially by asking more specific questions such as the tendency to doze off during daytime.8

Family members can be vital sources for obtaining a complete history,5 especially because patients might deny,8 minimize, or not be fully aware1 of the extent of their symptoms. Asking family members about patient’s snoring, irregular breathing, or gasping at night can be particularly valuable.5 Obtaining a family history of sleep disorders can be particularly important, especially in conditions such as OSA and narcolepsy.

Asking about any history of safety issues,8 including sleepiness during driving, cooking, or other activities, is also important.

Use of scales and other screening measures. Psychiatrists can use initial screening measures in the office setting. Epworth Sleepiness Scale15,21 is a validated,2 short, self-administered measure to assess the level of daytime sleepiness; however, it has some limitations such as not being able to measure changes in sleepiness from hour to hour or day to day. Because of its limitations, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale should not be used by itself as a diagnostic tool.3 It has been commonly used for detecting OSA2 and narcolepsy. The Stanford Sleepiness Scale is a self-rating scale that measures the subjective degree of sleepiness and alertness; it has limitations as well, such as having little correlation with chronic sleep loss.8 Other tools such as visual analogue scales also could be helpful.8 For more specialized testing, such as Multiple Sleep Latency Test or polysomnography, referral to a sleep specialist is ideal.8

Education. The assessment is an opportunity for the psychiatrist to educate patients about sleep hygiene, the importance of regular bedtimes, and getting adequate sleep to avoid accumulating a sleep deficit.

Urgent referral of at-risk populations. Prompt or urgent referral of at-risk populations, such as geriatric patients or those with a history of dozing off during driving, is invaluable in preventing morbidity and mortality from untreated sleep disorders.

Patients with severe daytime sleepiness should be advised to not drive or operate heavy machinery until this condition is adequately controlled.18

Bottom Line

1. Chervin RD. Approach to the patient with excessive daytime sleepiness. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-excessive-daytime-sleepiness. Updated January 2016. Accessed June 5, 2017.

2. Lee CH, Ng WY, Hau W, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness is associated with longer culprit lesion and adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(12):1267-1272.

3. Hawley CJ, Gale TM, Sivakumaran T, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in psychiatric disorders: prevalence, correlates and clinical significance. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(1-2):138-141.

4. Pigeon WR, Sateia MJ, Ferguson RJ. Distinguishing between excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue: toward improved detection and treatment. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(1):61-69.

5. Krahn LE. Excessive daytime sleepiness: diagnosing the causes. Current Psychiatry. 2002;1(1):49-57.

6. Ejaz SM, Khawaja IS, Bhatia S, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and depression: a review. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(8):17-25.

7. Pagel JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(5):391-396.

8. Guilleminault C, Brooks SN. Excessive daytime sleepiness: a challenge for the practising neurologist. Brain. 2001;124(pt 8):1482-1491.

9. Cheng P, Casement M, Chen CF, et al. Sleep disordered breathing in major depressive disorder. J Sleep Res. 2013;22(4):459-462.

10. Schröder CM, O’Hara R. Depression and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2005;4:13.

11. Bardwell WA, Berry CC, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Psychological correlates of sleep apnea. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47(6):583-596.

12. Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-Bang Questionnaire: a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2016;149(3):631-638.

13. Chellappa SL, Araújo JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with depressive disorder. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28(2):126-129.

14. Habukawa M, Uchimura N, Kakuma T, et al. Effect of CPAP treatment on residual depressive symptoms in patients with major depression and coexisting sleep apnea: contribution of daytime sleepiness to residual depressive symptoms. Sleep Med. 2010;11(6):552-557.

15. Lundt L. Use of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale to evaluate the symptom of excessive sleepiness in major depressive disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27(2):146-148.

16. Hawley CJ. Excessive daytime sleepiness in psychiatry: a relevant focus for clinical attention and treatment? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2006;10(2):117-123.

17. Dodson ER, Zee PC. Therapeutics for circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Sleep Med Clin. 2010;5(4):701-715.

18. Morgenthaler TI, Kapur VK, Brown TM, et al; Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for the treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin. Sleep. 2007;30(12):1705-1711.

19. Thorpy MJ. Classification of sleep disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(4):687-701.

20. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Restless legs syndrome information page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Restless-Legs-Syndrome-Information-Page. Accessed June 2, 2017.

21. Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1992;15(4):376-381.

1. Chervin RD. Approach to the patient with excessive daytime sleepiness. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-excessive-daytime-sleepiness. Updated January 2016. Accessed June 5, 2017.

2. Lee CH, Ng WY, Hau W, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness is associated with longer culprit lesion and adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(12):1267-1272.

3. Hawley CJ, Gale TM, Sivakumaran T, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in psychiatric disorders: prevalence, correlates and clinical significance. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(1-2):138-141.

4. Pigeon WR, Sateia MJ, Ferguson RJ. Distinguishing between excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue: toward improved detection and treatment. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(1):61-69.

5. Krahn LE. Excessive daytime sleepiness: diagnosing the causes. Current Psychiatry. 2002;1(1):49-57.

6. Ejaz SM, Khawaja IS, Bhatia S, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and depression: a review. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(8):17-25.

7. Pagel JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(5):391-396.

8. Guilleminault C, Brooks SN. Excessive daytime sleepiness: a challenge for the practising neurologist. Brain. 2001;124(pt 8):1482-1491.

9. Cheng P, Casement M, Chen CF, et al. Sleep disordered breathing in major depressive disorder. J Sleep Res. 2013;22(4):459-462.

10. Schröder CM, O’Hara R. Depression and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2005;4:13.

11. Bardwell WA, Berry CC, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Psychological correlates of sleep apnea. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47(6):583-596.

12. Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-Bang Questionnaire: a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2016;149(3):631-638.

13. Chellappa SL, Araújo JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with depressive disorder. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28(2):126-129.

14. Habukawa M, Uchimura N, Kakuma T, et al. Effect of CPAP treatment on residual depressive symptoms in patients with major depression and coexisting sleep apnea: contribution of daytime sleepiness to residual depressive symptoms. Sleep Med. 2010;11(6):552-557.

15. Lundt L. Use of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale to evaluate the symptom of excessive sleepiness in major depressive disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27(2):146-148.

16. Hawley CJ. Excessive daytime sleepiness in psychiatry: a relevant focus for clinical attention and treatment? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2006;10(2):117-123.

17. Dodson ER, Zee PC. Therapeutics for circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Sleep Med Clin. 2010;5(4):701-715.

18. Morgenthaler TI, Kapur VK, Brown TM, et al; Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for the treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin. Sleep. 2007;30(12):1705-1711.

19. Thorpy MJ. Classification of sleep disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(4):687-701.

20. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Restless legs syndrome information page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Restless-Legs-Syndrome-Information-Page. Accessed June 2, 2017.

21. Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1992;15(4):376-381.

Excessive daytime sleepiness

Nocturia and sleep apnea

Author’s note: I have been writing “Myth of the Month” columns for the last several years. I will try to continue to write about myths when possible, but I would like to introduce a new column, “Pearl of the Month.” I want to share with you pearls that I have found really helpful in medical practice. Some of these will be new news, while some may be old news that may not be well known.

A 65-year-old man comes to a clinic concerned about frequent nocturia. He is getting up four times a night to urinate, and he has been urinating about every 5 hours during the day. He has been seen twice for this problem and was diagnosed with benign prostatic hyperplasia and started on tamsulosin.

He found a slight improvement when he started on 0.4 mg qhs, reducing his nocturia episodes from four to three. His dose was increased to 0.8 mg qhs, with no improvement in nocturia.

Exam today: BP, 140/94; pulse, 70. Rectal exam: Prostate is twice normal size without nodules. Labs: Na, 140; K, 4.0; glucose, 80; Ca, 9.6.

He is frustrated because he feels tired and sleepy from having to get up so often to urinate every night.

What is the best treatment/advice at this point?

A. Check hemoglobin A1C.

B. Start finasteride.

C. Switch tamsulosin to terazosin.

D. Evaluate for sleep apnea.

Umpei Yamamoto, MD, of Kyushu University Hospital, Japan, and colleagues studied the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing among patients who presented to a urology clinic with nocturia and in those who visited a sleep apnea clinic with symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness.1 Sleep-disordered breathing was found in 91% of the patients from the sleep apnea clinic and 70% of the patients from the urology clinic. The frequency of nocturia was reduced with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in both groups in the patients who had not responded to conventional therapy or nocturia.

The symptom of nocturia as a symptom of sleep apnea might be even more common in women.2 Ozen K. Basoglu, MD, and Mehmet Sezai Tasbakan, MD, of Ege University, Izmir, Turkey, described clinical similarities and differences based on gender in a large group of patients with sleep apnea. Both men and women with sleep apnea had similar rates of excessive daytime sleepiness, snoring, and impaired concentration. Women had more frequent nocturia.

Nocturia especially should be considered a possible clue for the presence of sleep apnea in younger patients who have fewer other reasons to have nocturia. Takahiro Maeda, MD, of Keio University, Tokyo, and colleagues found that men younger than 50 years had more nocturnal urinations the worse their apnea-hypopnea index was.3 Overall in the study, 85% of the patients had a reduction in nighttime urination after CPAP therapy.

Treatment of sleep apnea has been shown in several studies to improve the nocturia that occurs in patients with sleep apnea. Hyoung Keun Park, MD, of Konkuk University, Seoul, and colleagues studied whether surgical intervention with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) reduced nocturia in patients with sleep apnea.4 In the study, there was a 73% success rate in treatment for sleep apnea with the UPPP surgery, and, among those who had successful surgeries, nocturia episodes decreased from 1.9 preoperatively to 0.7 postoperatively (P less than .001).

Minoru Miyazato, MD, PhD, of University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa, Japan, and colleagues looked at the effect of CPAP treatment on nighttime urine production in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.5 In this small study of 40 patients, mean nighttime voiding episodes decreased from 2.1 to 1.2 (P less than .01).

Pearl: Sleep apnea should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with nocturia, and treatment of sleep apnea may decrease nocturia.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

References

1. Intern Med. 2016;55(8):901-5.

2. Sleep Breath. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1007/s11325-017-1482-9.

3. Can Urol Assoc J. 2016 Jul-Aug;10(7-8):E241-5.

4. Int Neurourol J. 2016 Dec;20(4):329-34.

5. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017 Feb;36(2):376-9.

Author’s note: I have been writing “Myth of the Month” columns for the last several years. I will try to continue to write about myths when possible, but I would like to introduce a new column, “Pearl of the Month.” I want to share with you pearls that I have found really helpful in medical practice. Some of these will be new news, while some may be old news that may not be well known.

A 65-year-old man comes to a clinic concerned about frequent nocturia. He is getting up four times a night to urinate, and he has been urinating about every 5 hours during the day. He has been seen twice for this problem and was diagnosed with benign prostatic hyperplasia and started on tamsulosin.

He found a slight improvement when he started on 0.4 mg qhs, reducing his nocturia episodes from four to three. His dose was increased to 0.8 mg qhs, with no improvement in nocturia.

Exam today: BP, 140/94; pulse, 70. Rectal exam: Prostate is twice normal size without nodules. Labs: Na, 140; K, 4.0; glucose, 80; Ca, 9.6.

He is frustrated because he feels tired and sleepy from having to get up so often to urinate every night.

What is the best treatment/advice at this point?

A. Check hemoglobin A1C.

B. Start finasteride.

C. Switch tamsulosin to terazosin.

D. Evaluate for sleep apnea.

Umpei Yamamoto, MD, of Kyushu University Hospital, Japan, and colleagues studied the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing among patients who presented to a urology clinic with nocturia and in those who visited a sleep apnea clinic with symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness.1 Sleep-disordered breathing was found in 91% of the patients from the sleep apnea clinic and 70% of the patients from the urology clinic. The frequency of nocturia was reduced with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in both groups in the patients who had not responded to conventional therapy or nocturia.

The symptom of nocturia as a symptom of sleep apnea might be even more common in women.2 Ozen K. Basoglu, MD, and Mehmet Sezai Tasbakan, MD, of Ege University, Izmir, Turkey, described clinical similarities and differences based on gender in a large group of patients with sleep apnea. Both men and women with sleep apnea had similar rates of excessive daytime sleepiness, snoring, and impaired concentration. Women had more frequent nocturia.

Nocturia especially should be considered a possible clue for the presence of sleep apnea in younger patients who have fewer other reasons to have nocturia. Takahiro Maeda, MD, of Keio University, Tokyo, and colleagues found that men younger than 50 years had more nocturnal urinations the worse their apnea-hypopnea index was.3 Overall in the study, 85% of the patients had a reduction in nighttime urination after CPAP therapy.

Treatment of sleep apnea has been shown in several studies to improve the nocturia that occurs in patients with sleep apnea. Hyoung Keun Park, MD, of Konkuk University, Seoul, and colleagues studied whether surgical intervention with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) reduced nocturia in patients with sleep apnea.4 In the study, there was a 73% success rate in treatment for sleep apnea with the UPPP surgery, and, among those who had successful surgeries, nocturia episodes decreased from 1.9 preoperatively to 0.7 postoperatively (P less than .001).

Minoru Miyazato, MD, PhD, of University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa, Japan, and colleagues looked at the effect of CPAP treatment on nighttime urine production in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.5 In this small study of 40 patients, mean nighttime voiding episodes decreased from 2.1 to 1.2 (P less than .01).

Pearl: Sleep apnea should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with nocturia, and treatment of sleep apnea may decrease nocturia.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

References

1. Intern Med. 2016;55(8):901-5.

2. Sleep Breath. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1007/s11325-017-1482-9.

3. Can Urol Assoc J. 2016 Jul-Aug;10(7-8):E241-5.

4. Int Neurourol J. 2016 Dec;20(4):329-34.

5. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017 Feb;36(2):376-9.

Author’s note: I have been writing “Myth of the Month” columns for the last several years. I will try to continue to write about myths when possible, but I would like to introduce a new column, “Pearl of the Month.” I want to share with you pearls that I have found really helpful in medical practice. Some of these will be new news, while some may be old news that may not be well known.

A 65-year-old man comes to a clinic concerned about frequent nocturia. He is getting up four times a night to urinate, and he has been urinating about every 5 hours during the day. He has been seen twice for this problem and was diagnosed with benign prostatic hyperplasia and started on tamsulosin.

He found a slight improvement when he started on 0.4 mg qhs, reducing his nocturia episodes from four to three. His dose was increased to 0.8 mg qhs, with no improvement in nocturia.

Exam today: BP, 140/94; pulse, 70. Rectal exam: Prostate is twice normal size without nodules. Labs: Na, 140; K, 4.0; glucose, 80; Ca, 9.6.

He is frustrated because he feels tired and sleepy from having to get up so often to urinate every night.

What is the best treatment/advice at this point?

A. Check hemoglobin A1C.

B. Start finasteride.

C. Switch tamsulosin to terazosin.

D. Evaluate for sleep apnea.

Umpei Yamamoto, MD, of Kyushu University Hospital, Japan, and colleagues studied the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing among patients who presented to a urology clinic with nocturia and in those who visited a sleep apnea clinic with symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness.1 Sleep-disordered breathing was found in 91% of the patients from the sleep apnea clinic and 70% of the patients from the urology clinic. The frequency of nocturia was reduced with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in both groups in the patients who had not responded to conventional therapy or nocturia.

The symptom of nocturia as a symptom of sleep apnea might be even more common in women.2 Ozen K. Basoglu, MD, and Mehmet Sezai Tasbakan, MD, of Ege University, Izmir, Turkey, described clinical similarities and differences based on gender in a large group of patients with sleep apnea. Both men and women with sleep apnea had similar rates of excessive daytime sleepiness, snoring, and impaired concentration. Women had more frequent nocturia.

Nocturia especially should be considered a possible clue for the presence of sleep apnea in younger patients who have fewer other reasons to have nocturia. Takahiro Maeda, MD, of Keio University, Tokyo, and colleagues found that men younger than 50 years had more nocturnal urinations the worse their apnea-hypopnea index was.3 Overall in the study, 85% of the patients had a reduction in nighttime urination after CPAP therapy.

Treatment of sleep apnea has been shown in several studies to improve the nocturia that occurs in patients with sleep apnea. Hyoung Keun Park, MD, of Konkuk University, Seoul, and colleagues studied whether surgical intervention with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) reduced nocturia in patients with sleep apnea.4 In the study, there was a 73% success rate in treatment for sleep apnea with the UPPP surgery, and, among those who had successful surgeries, nocturia episodes decreased from 1.9 preoperatively to 0.7 postoperatively (P less than .001).

Minoru Miyazato, MD, PhD, of University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa, Japan, and colleagues looked at the effect of CPAP treatment on nighttime urine production in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.5 In this small study of 40 patients, mean nighttime voiding episodes decreased from 2.1 to 1.2 (P less than .01).

Pearl: Sleep apnea should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with nocturia, and treatment of sleep apnea may decrease nocturia.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

References

1. Intern Med. 2016;55(8):901-5.

2. Sleep Breath. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1007/s11325-017-1482-9.

3. Can Urol Assoc J. 2016 Jul-Aug;10(7-8):E241-5.

4. Int Neurourol J. 2016 Dec;20(4):329-34.

5. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017 Feb;36(2):376-9.

Most arrhythmia clinic patients have undetected OSA

BOSTON – In a study of patients without a previous diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), 85% of participants in outpatient arrhythmia clinics had undetected OSA.

The study, which also excluded patients who had ever been treated for OSA, was presented by Colin Shapiro, MD, of the Department of Psychiatry, Toronto Western Hospital, University of Toronto, at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

A binary logistic regression analysis showed that only age and male gender were significant predictors of OSA.

Along with a home sleep study, researchers tested 75 nonselected consecutive patients (mean age of 64 years; 72% male) from three outpatient arrhythmia clinics for symptoms indicative of OSA using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), the Non-Restorative Sleep Scale (NRSS), and other questionnaires.

On the ESS, 32% of patients had a score of 8 or greater, indicating higher than normal daytime sleepiness. Almost half (47%) of patients had a high level of fatigue on the FSS, and symptoms of nonrestorative sleep were detected in 15% (NRSS score greater than or equal to 46).

Dr. Shapiro noted that “high scores suggestive of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or insomnia did not particularly predict the presence of OSA in patients with arrhythmia.” He concluded that, “with a hit rate of 85%, just about every patient with an arrhythmia should have a sleep study.”

Dr. Shapiro informed attendees at the annual meeting of the Professional Sleep Societies that he was presenting in place of his student and the abstract’s first author, Dr. Asmaa M. Abumuamar, MD, who was denied a visa to attend the meeting. Dr. Abumuamar is from the Toronto Western Research Institute, University of Toronto.

Dr. Shapiro reported that Dr. Abumuamar has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Shapiro reported that he is an investor in the company that supplied the home sleep testing apparatus.

BOSTON – In a study of patients without a previous diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), 85% of participants in outpatient arrhythmia clinics had undetected OSA.

The study, which also excluded patients who had ever been treated for OSA, was presented by Colin Shapiro, MD, of the Department of Psychiatry, Toronto Western Hospital, University of Toronto, at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

A binary logistic regression analysis showed that only age and male gender were significant predictors of OSA.

Along with a home sleep study, researchers tested 75 nonselected consecutive patients (mean age of 64 years; 72% male) from three outpatient arrhythmia clinics for symptoms indicative of OSA using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), the Non-Restorative Sleep Scale (NRSS), and other questionnaires.

On the ESS, 32% of patients had a score of 8 or greater, indicating higher than normal daytime sleepiness. Almost half (47%) of patients had a high level of fatigue on the FSS, and symptoms of nonrestorative sleep were detected in 15% (NRSS score greater than or equal to 46).

Dr. Shapiro noted that “high scores suggestive of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or insomnia did not particularly predict the presence of OSA in patients with arrhythmia.” He concluded that, “with a hit rate of 85%, just about every patient with an arrhythmia should have a sleep study.”

Dr. Shapiro informed attendees at the annual meeting of the Professional Sleep Societies that he was presenting in place of his student and the abstract’s first author, Dr. Asmaa M. Abumuamar, MD, who was denied a visa to attend the meeting. Dr. Abumuamar is from the Toronto Western Research Institute, University of Toronto.

Dr. Shapiro reported that Dr. Abumuamar has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Shapiro reported that he is an investor in the company that supplied the home sleep testing apparatus.

BOSTON – In a study of patients without a previous diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), 85% of participants in outpatient arrhythmia clinics had undetected OSA.

The study, which also excluded patients who had ever been treated for OSA, was presented by Colin Shapiro, MD, of the Department of Psychiatry, Toronto Western Hospital, University of Toronto, at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

A binary logistic regression analysis showed that only age and male gender were significant predictors of OSA.

Along with a home sleep study, researchers tested 75 nonselected consecutive patients (mean age of 64 years; 72% male) from three outpatient arrhythmia clinics for symptoms indicative of OSA using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), the Non-Restorative Sleep Scale (NRSS), and other questionnaires.

On the ESS, 32% of patients had a score of 8 or greater, indicating higher than normal daytime sleepiness. Almost half (47%) of patients had a high level of fatigue on the FSS, and symptoms of nonrestorative sleep were detected in 15% (NRSS score greater than or equal to 46).

Dr. Shapiro noted that “high scores suggestive of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or insomnia did not particularly predict the presence of OSA in patients with arrhythmia.” He concluded that, “with a hit rate of 85%, just about every patient with an arrhythmia should have a sleep study.”

Dr. Shapiro informed attendees at the annual meeting of the Professional Sleep Societies that he was presenting in place of his student and the abstract’s first author, Dr. Asmaa M. Abumuamar, MD, who was denied a visa to attend the meeting. Dr. Abumuamar is from the Toronto Western Research Institute, University of Toronto.

Dr. Shapiro reported that Dr. Abumuamar has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Shapiro reported that he is an investor in the company that supplied the home sleep testing apparatus.

AT SLEEP 2017

Key clinical point: The majority of patients attending an outpatient arrhythmia clinic had undetected OSA.

Major finding: Of the participants, 91% of males and 71% of females with no history of OSA were found to have the disorder (85% of total).

Data source: A screening study using a randomized, unselected population drawn from outpatient arrhythmia clinics. Those with a diagnoses of OSA were excluded.

Disclosures: Dr. Shapiro reported that Dr. Abumuamar has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Shapiro reported that he is an investor in the company that supplied the home sleep testing apparatus.

Telemonitoring with feedback improves CPAP

BOSTON – Remote monitoring of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) use with feedback messaging to patients improves adherence but only when patients opt to receive continual feedback on their usage, according to a study.

Dennis Hwang, MD, medical director of Kaiser Permanent Fontana Medical Center in California and his colleagues designed the four-arm Tele-OSA study to evaluate the impact of two automated telemedicine interventions: an obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) education program (provided by Emmi Solutions) and a CPAP remote monitoring system with automated patient feedback (U-Sleep, ResMed). Dr. Hwang, who is also cochair of sleep medicine at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, presented his findings at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

CPAP adherence was compared at 3 months and 1 year for patients in all four groups. Dr. Hwang reported findings from 556 patients who completed one-year follow-up.

At 90 days, patients assigned to either of the telemonitoring arms had significantly higher CPAP usage than those who did not receive telemonitoring.

However, at 3 months when the study protocol called for the automated messaging to be turned off, CPAP adherence dropped off. By 8 months, adherence in patients using the telemonitoring system was no different from that in those who never received the automated messaging. That would have been the end of the story, except that there was a glitch in the system.

“Perhaps serendipitously, we had a group of patients, about one-third, for whom we inadvertently did not turn off the messaging,” explained Dr. Hwang. “In these patients who continued to receive feedback, CPAP usage remained elevated throughout the course of the year and, at 12 months, was significantly higher than in the patients who were not receiving any kind of messaging.”

Dr. Hwang added that the telemonitoring required no additional provider intervention, “suggesting that this could be a cost-effective strategy.”

Only one-third of patients (66.7%) assigned to one of the tele-education groups viewed the video. Additionally, the researchers found that, whether patients used the tele-education alone or in combination with the telemonitoring, tele-education use had no impact on 90-day compliance with CPAP.

Dr. Hwang received support from the American Sleep Medicine Foundation and ResMed Science.