User login

Is Patient With Fingernail Changes a "Contagious Threat"?

ANSWER

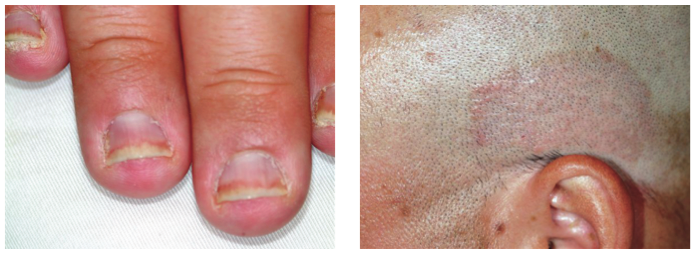

The correct answer is psoriasis (choice “d”), which often involves nail and skin changes such as those seen in this case. There was no particular reason to think this patient had an infection of any kind, but, as is often the case, the original provider considered only one diagnostic possibility.

DISCUSSION

Nail disease can be problematic for both patient and provider. Arguably the biggest issue with it, initially, is “the one-item differential”—the idea that all nail disease can be classified as “fungal infection” simply because neither the patient nor the provider considers any other explanation for the changes seen. This case illustrates that dilemma nicely.

Psoriasis affects more than 2% of the US population, making it a common skin disorder. As this case illustrates, it may affect several areas with diverse but predictable morphologic presentations, all appearing at the same time.

The key diagnostic points from this case include:

• Stress is a known trigger for psoriasis vulgaris.

• The patient’s nails failed to respond to terbinafine treatment.

• There was no obvious source of fungal infection (eg, contact with animals) or reason for him to have a yeast infection (eg, diabetes) or develop mold “infection” in the nails (eg, trauma from digging in soil).

• Fungal infections are about 18 times less likely to occur in the fingernails than in the toenails.

• A unifying explanation for simultaneous nail and skin changes was needed.

• The nail and skin changes seen here are quite typical for psoriasis.

Most important, though, is the need to overcome the urge to hop on the “fungal bandwagon” by first considering other diagnostic possibilities.

Continue for the treatment of this condition >>

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, there is no good treatment for this patient’s nails. However, there is an excellent chance that his scalp psoriasis will respond to short-term use of fluocinolone 0.05% cream.

This patient was also counseled about the role of stress in his condition and the benefits of modest increases in UV exposure. During follow-up, it will be important to ask about joint pain, since up to 30% of psoriasis patients will eventually develop psoriatic arthritis.

If the patient’s current treatment does not produce sufficient results, other options include calcipotriene ointment, oral methotrexate, or even one of the biologics (etanercept or adalimumab).

ANSWER

The correct answer is psoriasis (choice “d”), which often involves nail and skin changes such as those seen in this case. There was no particular reason to think this patient had an infection of any kind, but, as is often the case, the original provider considered only one diagnostic possibility.

DISCUSSION

Nail disease can be problematic for both patient and provider. Arguably the biggest issue with it, initially, is “the one-item differential”—the idea that all nail disease can be classified as “fungal infection” simply because neither the patient nor the provider considers any other explanation for the changes seen. This case illustrates that dilemma nicely.

Psoriasis affects more than 2% of the US population, making it a common skin disorder. As this case illustrates, it may affect several areas with diverse but predictable morphologic presentations, all appearing at the same time.

The key diagnostic points from this case include:

• Stress is a known trigger for psoriasis vulgaris.

• The patient’s nails failed to respond to terbinafine treatment.

• There was no obvious source of fungal infection (eg, contact with animals) or reason for him to have a yeast infection (eg, diabetes) or develop mold “infection” in the nails (eg, trauma from digging in soil).

• Fungal infections are about 18 times less likely to occur in the fingernails than in the toenails.

• A unifying explanation for simultaneous nail and skin changes was needed.

• The nail and skin changes seen here are quite typical for psoriasis.

Most important, though, is the need to overcome the urge to hop on the “fungal bandwagon” by first considering other diagnostic possibilities.

Continue for the treatment of this condition >>

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, there is no good treatment for this patient’s nails. However, there is an excellent chance that his scalp psoriasis will respond to short-term use of fluocinolone 0.05% cream.

This patient was also counseled about the role of stress in his condition and the benefits of modest increases in UV exposure. During follow-up, it will be important to ask about joint pain, since up to 30% of psoriasis patients will eventually develop psoriatic arthritis.

If the patient’s current treatment does not produce sufficient results, other options include calcipotriene ointment, oral methotrexate, or even one of the biologics (etanercept or adalimumab).

ANSWER

The correct answer is psoriasis (choice “d”), which often involves nail and skin changes such as those seen in this case. There was no particular reason to think this patient had an infection of any kind, but, as is often the case, the original provider considered only one diagnostic possibility.

DISCUSSION

Nail disease can be problematic for both patient and provider. Arguably the biggest issue with it, initially, is “the one-item differential”—the idea that all nail disease can be classified as “fungal infection” simply because neither the patient nor the provider considers any other explanation for the changes seen. This case illustrates that dilemma nicely.

Psoriasis affects more than 2% of the US population, making it a common skin disorder. As this case illustrates, it may affect several areas with diverse but predictable morphologic presentations, all appearing at the same time.

The key diagnostic points from this case include:

• Stress is a known trigger for psoriasis vulgaris.

• The patient’s nails failed to respond to terbinafine treatment.

• There was no obvious source of fungal infection (eg, contact with animals) or reason for him to have a yeast infection (eg, diabetes) or develop mold “infection” in the nails (eg, trauma from digging in soil).

• Fungal infections are about 18 times less likely to occur in the fingernails than in the toenails.

• A unifying explanation for simultaneous nail and skin changes was needed.

• The nail and skin changes seen here are quite typical for psoriasis.

Most important, though, is the need to overcome the urge to hop on the “fungal bandwagon” by first considering other diagnostic possibilities.

Continue for the treatment of this condition >>

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, there is no good treatment for this patient’s nails. However, there is an excellent chance that his scalp psoriasis will respond to short-term use of fluocinolone 0.05% cream.

This patient was also counseled about the role of stress in his condition and the benefits of modest increases in UV exposure. During follow-up, it will be important to ask about joint pain, since up to 30% of psoriasis patients will eventually develop psoriatic arthritis.

If the patient’s current treatment does not produce sufficient results, other options include calcipotriene ointment, oral methotrexate, or even one of the biologics (etanercept or adalimumab).

After finishing a month-long course of terbinafine (250 mg), a 27-year-old man is dismayed to see that the fingernail changes he first noted a year ago have not improved. He had been told in no uncertain terms by his primary care provider that his fingernail condition—and accompanying scalp rash—represented fungal infection. When topical antifungal creams failed to help his scalp condition, the oral medication was prescribed. Now it, too, appears to have been unhelpful. At this point, the patient requests referral to dermatology. His primary concern is that he represents a “contagious threat” to his wife and children, although none of them has shown any signs of this condition. The patient denies any skin problems prior to the nail changes and the scalp rash that manifested shortly afterward, which occurred more than a year ago. Shortly before the onset of these problems, he lost his job and had to replace it with two lower-paying part-time jobs. He denies any family history of skin disease or joint pain. There are no new pets in the house, and the patient does not work with animals. Examination reveals that the distal portions of all 10 fingernails are uniformly dystrophic and mildly onycholytic and have numerous longitudinal dark streaks. Several fingernails also have tiny scattered pits in them. The toenails are unaffected. Elsewhere, the man is observed to have salmon-pink scaly patches on the scalp and over both ears, and smaller, round plaques on the forehead, with prominent white tenacious scale. KOH prep of these latter lesions is negative for fungal elements.

Woman Thrown From Horse

ANSWER

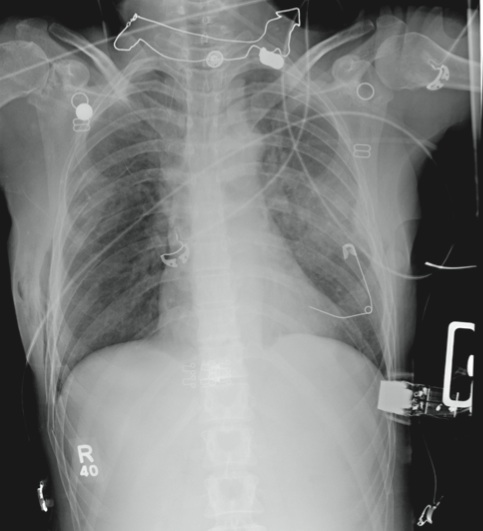

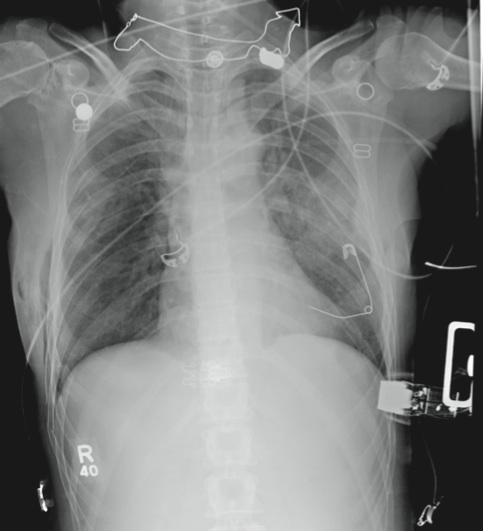

The radiograph demonstrates several findings. First, there are multiple bilateral rib fractures. Five to six ribs are broken and displaced on both sides. In addition, there are bilateral small apical pneumothoraces. Finally, there is evidence of bilateral pulmonary contusions beginning to form, more so on the left than the right side.

This patient was admitted to the ICU, where a chest tube was placed and a thoracic epidural was administered for pain control. As her contusions worsened, she was electively intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation for a few days. She subsequently underwent open reduction and internal fixation of her rib fractures. As her contusions improved, she was weaned off the ventilator and extubated, eventually making a full recovery.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates several findings. First, there are multiple bilateral rib fractures. Five to six ribs are broken and displaced on both sides. In addition, there are bilateral small apical pneumothoraces. Finally, there is evidence of bilateral pulmonary contusions beginning to form, more so on the left than the right side.

This patient was admitted to the ICU, where a chest tube was placed and a thoracic epidural was administered for pain control. As her contusions worsened, she was electively intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation for a few days. She subsequently underwent open reduction and internal fixation of her rib fractures. As her contusions improved, she was weaned off the ventilator and extubated, eventually making a full recovery.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates several findings. First, there are multiple bilateral rib fractures. Five to six ribs are broken and displaced on both sides. In addition, there are bilateral small apical pneumothoraces. Finally, there is evidence of bilateral pulmonary contusions beginning to form, more so on the left than the right side.

This patient was admitted to the ICU, where a chest tube was placed and a thoracic epidural was administered for pain control. As her contusions worsened, she was electively intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation for a few days. She subsequently underwent open reduction and internal fixation of her rib fractures. As her contusions improved, she was weaned off the ventilator and extubated, eventually making a full recovery.

A 53-year-old woman is brought to your facility complaining of right-side chest pain. Earlier this evening, while riding her horse, she was thrown off; the horse then fell on top of her. She denies any loss of consciousness. Most of her pain occurs when she inhales. The patient’s medical history is unremarkable. Her vital signs are: blood pressure, 148/87 mm Hg; heart rate, 100 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 100% with oxygen via nasal cannula. Primary survey reveals moderate tenderness to palpation along the right side of the patient’s chest, with associated crepitus. Some decreased breath sounds are noted on the right, along with crackles. She is moving all of her extremities and otherwise appears neurologically intact. A stat portable chest radiograph is obtained in the trauma bay before the patient is transported for CT scans. What is your impression?

A "Spider Bite" That Wasn't

ANSWER

The one unreasonable choice is a 10-day course of rifampin (choice “a”). One potential explanation for the lack of response to two different antibiotics would be the probability that there was no infection to begin with. See below for further explanation.

DISCUSSION

Erythema nodosum (EN; choice “c”) is the presumptive diagnosis in cases such as this one. The “erythemas” (multiforme, annulare centrifigum, etc) are all secondary reactions to antigenic triggers—such as herpes simplex virus, strep, or other organisms—and not primary conditions.

EN is a type of panniculitis that can be triggered by a number of conditions (eg, sarcoidosis), medicines (eg, penicillin), or organisms (eg, group A β streptococcus). It can also, as in this case, accompany inflammatory bowel disease, paralleling the flares and remissions of Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis and responding to treatment for those diseases. This is why part of the workup for EN includes evaluation for bowel disease.

The absence of breaks in the skin in such cases also speaks loudly for EN, since it involves only the adipose tissues and spares the skin. In this case, given the dearth of other suspicious items in the differential, a presumptive diagnosis of EN was quite reasonable.

Deep punch biopsy (choice “b”), which must include significant adipose tissue (5 mm or surgical wedge), can be crucial in questionable cases. It can show septal panniculitis (as opposed to lobular, which is more consistent with erythema induratum), as well as characteristic Miescher’s granulomas.

A chest radiograph (choice “d”), while not especially indicated in this case, is likewise an intelligent choice. Both tuberculosis and sarcoidosis can lead to radiographic changes and trigger EN.

If local infection were truly suspected as the direct cause of this patient’s lesions, an additional punch biopsy or two might serve to provide sufficient material for aerobic bacterial culture, acid-fast culture, and deep fungal culture—all of which are possible, though unlikely, explanations. Literally, the last thing we’d do is throw yet another antibiotic at this patient, who was in need of one simple thing: a correct diagnosis that would dictate proper treatment.

TREATMENT

A letter was dictated and sent to the gastroenterologist the patient was scheduled to see, to alert him as to our findings. If his workup

(H&P, stool cultures for salmonella, yersinia, and campylobacter, colonoscopy with biopsy) fails to pinpoint a particular trigger for her EN, additional labs will be needed. These would include antistreptolysin-O titer and tuberculosis and coccidioidomycosis skin testing, as well as actual biopsy of the lesions.

As of this writing, the patient’s GI appointment was pending, but the likely outcome will be the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. Treatment for either of these conditions will quiet down her EN. Often, however, EN is idiopathic and must be treated as a stand-alone diagnosis, with NSAIDs, antimalarials, or potassium iodide.

ANSWER

The one unreasonable choice is a 10-day course of rifampin (choice “a”). One potential explanation for the lack of response to two different antibiotics would be the probability that there was no infection to begin with. See below for further explanation.

DISCUSSION

Erythema nodosum (EN; choice “c”) is the presumptive diagnosis in cases such as this one. The “erythemas” (multiforme, annulare centrifigum, etc) are all secondary reactions to antigenic triggers—such as herpes simplex virus, strep, or other organisms—and not primary conditions.

EN is a type of panniculitis that can be triggered by a number of conditions (eg, sarcoidosis), medicines (eg, penicillin), or organisms (eg, group A β streptococcus). It can also, as in this case, accompany inflammatory bowel disease, paralleling the flares and remissions of Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis and responding to treatment for those diseases. This is why part of the workup for EN includes evaluation for bowel disease.

The absence of breaks in the skin in such cases also speaks loudly for EN, since it involves only the adipose tissues and spares the skin. In this case, given the dearth of other suspicious items in the differential, a presumptive diagnosis of EN was quite reasonable.

Deep punch biopsy (choice “b”), which must include significant adipose tissue (5 mm or surgical wedge), can be crucial in questionable cases. It can show septal panniculitis (as opposed to lobular, which is more consistent with erythema induratum), as well as characteristic Miescher’s granulomas.

A chest radiograph (choice “d”), while not especially indicated in this case, is likewise an intelligent choice. Both tuberculosis and sarcoidosis can lead to radiographic changes and trigger EN.

If local infection were truly suspected as the direct cause of this patient’s lesions, an additional punch biopsy or two might serve to provide sufficient material for aerobic bacterial culture, acid-fast culture, and deep fungal culture—all of which are possible, though unlikely, explanations. Literally, the last thing we’d do is throw yet another antibiotic at this patient, who was in need of one simple thing: a correct diagnosis that would dictate proper treatment.

TREATMENT

A letter was dictated and sent to the gastroenterologist the patient was scheduled to see, to alert him as to our findings. If his workup

(H&P, stool cultures for salmonella, yersinia, and campylobacter, colonoscopy with biopsy) fails to pinpoint a particular trigger for her EN, additional labs will be needed. These would include antistreptolysin-O titer and tuberculosis and coccidioidomycosis skin testing, as well as actual biopsy of the lesions.

As of this writing, the patient’s GI appointment was pending, but the likely outcome will be the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. Treatment for either of these conditions will quiet down her EN. Often, however, EN is idiopathic and must be treated as a stand-alone diagnosis, with NSAIDs, antimalarials, or potassium iodide.

ANSWER

The one unreasonable choice is a 10-day course of rifampin (choice “a”). One potential explanation for the lack of response to two different antibiotics would be the probability that there was no infection to begin with. See below for further explanation.

DISCUSSION

Erythema nodosum (EN; choice “c”) is the presumptive diagnosis in cases such as this one. The “erythemas” (multiforme, annulare centrifigum, etc) are all secondary reactions to antigenic triggers—such as herpes simplex virus, strep, or other organisms—and not primary conditions.

EN is a type of panniculitis that can be triggered by a number of conditions (eg, sarcoidosis), medicines (eg, penicillin), or organisms (eg, group A β streptococcus). It can also, as in this case, accompany inflammatory bowel disease, paralleling the flares and remissions of Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis and responding to treatment for those diseases. This is why part of the workup for EN includes evaluation for bowel disease.

The absence of breaks in the skin in such cases also speaks loudly for EN, since it involves only the adipose tissues and spares the skin. In this case, given the dearth of other suspicious items in the differential, a presumptive diagnosis of EN was quite reasonable.

Deep punch biopsy (choice “b”), which must include significant adipose tissue (5 mm or surgical wedge), can be crucial in questionable cases. It can show septal panniculitis (as opposed to lobular, which is more consistent with erythema induratum), as well as characteristic Miescher’s granulomas.

A chest radiograph (choice “d”), while not especially indicated in this case, is likewise an intelligent choice. Both tuberculosis and sarcoidosis can lead to radiographic changes and trigger EN.

If local infection were truly suspected as the direct cause of this patient’s lesions, an additional punch biopsy or two might serve to provide sufficient material for aerobic bacterial culture, acid-fast culture, and deep fungal culture—all of which are possible, though unlikely, explanations. Literally, the last thing we’d do is throw yet another antibiotic at this patient, who was in need of one simple thing: a correct diagnosis that would dictate proper treatment.

TREATMENT

A letter was dictated and sent to the gastroenterologist the patient was scheduled to see, to alert him as to our findings. If his workup

(H&P, stool cultures for salmonella, yersinia, and campylobacter, colonoscopy with biopsy) fails to pinpoint a particular trigger for her EN, additional labs will be needed. These would include antistreptolysin-O titer and tuberculosis and coccidioidomycosis skin testing, as well as actual biopsy of the lesions.

As of this writing, the patient’s GI appointment was pending, but the likely outcome will be the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. Treatment for either of these conditions will quiet down her EN. Often, however, EN is idiopathic and must be treated as a stand-alone diagnosis, with NSAIDs, antimalarials, or potassium iodide.

Sore “red bumps” began to appear on this 31-year-old woman’s posterior calves six months ago. They persisted despite a course of cephalexin (500 mg qid for 10 days), prescribed by her primary care provider for “spider bites,” and a few weeks later, a course of double-strength sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (bid for 10 days), for “staph infection.” When the patient is seen by dermatology, her health history is good, although she mentions a pending appointment with a gastroenterologist to investigate lower abdominal cramping and diarrhea, both of which started several months ago. There has been no weight loss, nausea, or vomiting. The patient is unaware of any bites that could explain the red patches on her legs and denies any breaks in the affected skin. No lesions are evident elsewhere on her body. There is no personal or family history of skin disease, and the patient used no OTC or prescription medication prior to the appearance of the lesions. Examination reveals several deep subcutaneous nodules palpable in the calf, ranging in size from 1.5 to 2.5 cm. There is no broken skin, nor are there other skin changes overlying the lesions, except erythema and induration. There is modest tenderness on palpation, as well as a modest increase in warmth. No nodes are palpable in the groin on that side. Examination of the patient’s skin elsewhere shows no notable changes.

Six-month Facial Rash Continues to Burn

ANSWER

The correct answer is perioral dermatitis (POD; choice “c”), an extremely common dermatosis that often begins in the perinasal area, spreading downward with time.

Impetigo (choice “a”) does not bear much resemblance to POD and would have responded quite well to the course of cephalexin.

Lupus (choice “b”) belongs in the differential, given the patient’s gender and the condition’s chronicity; however, this condition typically prefers the lateral face, usually causes focal atrophy, and does not manifest with pustules and papules.

Had the patient not responded to medication for POD, a punch biopsy would have been a reasonable step to rule out lupus and psoriasis (choice “d”), which can present in a similar manner, though seldom as the sole manifestation of that disease.

DISCUSSION

POD is an eruption of unknown etiology that demonstrates the clinical features of several other conditions (including eczema, seborrhea, and acne). It is therefore often difficult to diagnose—especially when it has been present for so long and has been treated with several medications.

More than 90% of POD cases occur in women ages 24 to 50, which suggests a possible role for hormones, makeup, or facial products. Yet none of these factors has been specifically implicated in the condition’s genesis.

Indeed, virtually every woman with POD presents with a history of having changed her makeup and other facial products, often many times, to no good effect. Stress has also been suggested as a contributing factor, and indeed appears, to many dermatology providers, to be the culprit; however, this has yet to be proven.

What is known is that in a large percentage of cases, the chronic application of topical steroids either brings on POD or worsens it, thereby necessitating questions about steroid use. Many a patient with seborrhea has successfully treated that disease with topical steroids only to create POD—which she naturally treats with more and more steroid.

The histologic picture of POD is similar to rosacea. But unlike POD, the latter spares the concave areas of the face. Like rosacea, POD responds so readily to oral tetracycline (alternatives including minocycline, amoxicillin, and erythromycin) that treatment success essentially verifies the diagnosis. Simply knowing that POD is utterly common is extremely helpful in the development of any differential of facial eruptions.

This particular patient responded quite well to a course of tetracycline (500 mg bid for a month, then 500 qd for another month), at the end of which her skin was totally clear. While her lack of response to topical antibiotics is typical of POD, many women with this condition actually report significant irritation with these products.

ANSWER

The correct answer is perioral dermatitis (POD; choice “c”), an extremely common dermatosis that often begins in the perinasal area, spreading downward with time.

Impetigo (choice “a”) does not bear much resemblance to POD and would have responded quite well to the course of cephalexin.

Lupus (choice “b”) belongs in the differential, given the patient’s gender and the condition’s chronicity; however, this condition typically prefers the lateral face, usually causes focal atrophy, and does not manifest with pustules and papules.

Had the patient not responded to medication for POD, a punch biopsy would have been a reasonable step to rule out lupus and psoriasis (choice “d”), which can present in a similar manner, though seldom as the sole manifestation of that disease.

DISCUSSION

POD is an eruption of unknown etiology that demonstrates the clinical features of several other conditions (including eczema, seborrhea, and acne). It is therefore often difficult to diagnose—especially when it has been present for so long and has been treated with several medications.

More than 90% of POD cases occur in women ages 24 to 50, which suggests a possible role for hormones, makeup, or facial products. Yet none of these factors has been specifically implicated in the condition’s genesis.

Indeed, virtually every woman with POD presents with a history of having changed her makeup and other facial products, often many times, to no good effect. Stress has also been suggested as a contributing factor, and indeed appears, to many dermatology providers, to be the culprit; however, this has yet to be proven.

What is known is that in a large percentage of cases, the chronic application of topical steroids either brings on POD or worsens it, thereby necessitating questions about steroid use. Many a patient with seborrhea has successfully treated that disease with topical steroids only to create POD—which she naturally treats with more and more steroid.

The histologic picture of POD is similar to rosacea. But unlike POD, the latter spares the concave areas of the face. Like rosacea, POD responds so readily to oral tetracycline (alternatives including minocycline, amoxicillin, and erythromycin) that treatment success essentially verifies the diagnosis. Simply knowing that POD is utterly common is extremely helpful in the development of any differential of facial eruptions.

This particular patient responded quite well to a course of tetracycline (500 mg bid for a month, then 500 qd for another month), at the end of which her skin was totally clear. While her lack of response to topical antibiotics is typical of POD, many women with this condition actually report significant irritation with these products.

ANSWER

The correct answer is perioral dermatitis (POD; choice “c”), an extremely common dermatosis that often begins in the perinasal area, spreading downward with time.

Impetigo (choice “a”) does not bear much resemblance to POD and would have responded quite well to the course of cephalexin.

Lupus (choice “b”) belongs in the differential, given the patient’s gender and the condition’s chronicity; however, this condition typically prefers the lateral face, usually causes focal atrophy, and does not manifest with pustules and papules.

Had the patient not responded to medication for POD, a punch biopsy would have been a reasonable step to rule out lupus and psoriasis (choice “d”), which can present in a similar manner, though seldom as the sole manifestation of that disease.

DISCUSSION

POD is an eruption of unknown etiology that demonstrates the clinical features of several other conditions (including eczema, seborrhea, and acne). It is therefore often difficult to diagnose—especially when it has been present for so long and has been treated with several medications.

More than 90% of POD cases occur in women ages 24 to 50, which suggests a possible role for hormones, makeup, or facial products. Yet none of these factors has been specifically implicated in the condition’s genesis.

Indeed, virtually every woman with POD presents with a history of having changed her makeup and other facial products, often many times, to no good effect. Stress has also been suggested as a contributing factor, and indeed appears, to many dermatology providers, to be the culprit; however, this has yet to be proven.

What is known is that in a large percentage of cases, the chronic application of topical steroids either brings on POD or worsens it, thereby necessitating questions about steroid use. Many a patient with seborrhea has successfully treated that disease with topical steroids only to create POD—which she naturally treats with more and more steroid.

The histologic picture of POD is similar to rosacea. But unlike POD, the latter spares the concave areas of the face. Like rosacea, POD responds so readily to oral tetracycline (alternatives including minocycline, amoxicillin, and erythromycin) that treatment success essentially verifies the diagnosis. Simply knowing that POD is utterly common is extremely helpful in the development of any differential of facial eruptions.

This particular patient responded quite well to a course of tetracycline (500 mg bid for a month, then 500 qd for another month), at the end of which her skin was totally clear. While her lack of response to topical antibiotics is typical of POD, many women with this condition actually report significant irritation with these products.

A 39-year-old woman is distraught about the rash that has been present on her face for more than six months. The rash continues to burn and feel raw, despite the use of topical preparations of metronidazole and clindamycin, as well as a seven-day course of cephalexin (500 mg bid). These had been given for diagnoses of acne, then rosacea, and finally, seborrhea. In desperation, the patient has stopped using all makeup, changed brands of facial tissue, and—at the suggestion of her sister—gone on a strict diet of only fresh, raw food. None of these measures has helped, although the condition has waxed and waned a bit. The patient, who is employed as a physical therapist, denies any previous or current use of topical steroids, but states that early on she used a number of OTC products on her face, including triple-antibiotic ointment and numerous moisturizers. Aside from mild dyslipidemia, the patient claims to be in good health, with no history of atopy, eczema, or psoriasis. Initial questioning about her stress level reveals little, but on deeper probing, the patient admits to a great deal of stress and trouble sleeping, which she attributes to job insecurity for both herself and her husband. Moreover, she has noted that her facial condition worsens with spikes in her level of anxiety. Entering the exam room, you are struck by the florid nature of the patient’s condition, especially the redness. But there are also scattered tiny pustules in the eruption, which is largely confined to the perinasal, nasolabial, and perioral areas. Scaling is scattered about the rash. Additional questioning leads to the revelation that the rash originally began in the perinasal area, only later spreading to its current distributive pattern. No rash is observed in the patient’s brows or in or behind the ears, and there is no appreciable dandruff on her scalp. Her elbows, knees, and fingernails show no signs of disease.

Diagnosis Confirmed: What's Next?

ANSWER

The one inappropriate choice—and therefore, the correct answer—is ED&C (choice “a”). Of all the choices, this option has the greatest potential for an unacceptable scar and for a recurrence of the cancer. All the other choices are entirely appropriate.

DISCUSSION

Had this been a far older patient with little concern about appearance, ED&C would have been a perfectly acceptable choice. But this patient made her expectations clear enough, effectively ruling out such an approach. A plastic surgeon (choice “b”) could be expected to not only obtain adequate margins around this cancer, but to be able to close the defect with an acceptable cosmetic outcome. Mohs surgeons (choice “d”) have the unique ability to examine the excised tissue margins at the surgical bedside, closing only when those margins are determined microscopically to be clear. They also have the ability to close larger defects in difficult areas such as this, obtaining an acceptable final result.

Had the patient or situation contraindicated surgery, at least two options would remain. The first is imiquimod (choice “c”) cream, which has a proven ability to destroy basal cell carcinomas (when applied several times a week over a period of six weeks to three months). Uncertain results can, and often do, necessitate a biopsy to confirm total destruction, and the patient has to endure weeks of redness and irritation at the site during treatment.

The other option is radiation therapy (choice “e”), an extremely effective nonsurgical alternative. However, it requires multiple treatment sessions over several weeks and can damage surrounding skin.

ANSWER

The one inappropriate choice—and therefore, the correct answer—is ED&C (choice “a”). Of all the choices, this option has the greatest potential for an unacceptable scar and for a recurrence of the cancer. All the other choices are entirely appropriate.

DISCUSSION

Had this been a far older patient with little concern about appearance, ED&C would have been a perfectly acceptable choice. But this patient made her expectations clear enough, effectively ruling out such an approach. A plastic surgeon (choice “b”) could be expected to not only obtain adequate margins around this cancer, but to be able to close the defect with an acceptable cosmetic outcome. Mohs surgeons (choice “d”) have the unique ability to examine the excised tissue margins at the surgical bedside, closing only when those margins are determined microscopically to be clear. They also have the ability to close larger defects in difficult areas such as this, obtaining an acceptable final result.

Had the patient or situation contraindicated surgery, at least two options would remain. The first is imiquimod (choice “c”) cream, which has a proven ability to destroy basal cell carcinomas (when applied several times a week over a period of six weeks to three months). Uncertain results can, and often do, necessitate a biopsy to confirm total destruction, and the patient has to endure weeks of redness and irritation at the site during treatment.

The other option is radiation therapy (choice “e”), an extremely effective nonsurgical alternative. However, it requires multiple treatment sessions over several weeks and can damage surrounding skin.

ANSWER

The one inappropriate choice—and therefore, the correct answer—is ED&C (choice “a”). Of all the choices, this option has the greatest potential for an unacceptable scar and for a recurrence of the cancer. All the other choices are entirely appropriate.

DISCUSSION

Had this been a far older patient with little concern about appearance, ED&C would have been a perfectly acceptable choice. But this patient made her expectations clear enough, effectively ruling out such an approach. A plastic surgeon (choice “b”) could be expected to not only obtain adequate margins around this cancer, but to be able to close the defect with an acceptable cosmetic outcome. Mohs surgeons (choice “d”) have the unique ability to examine the excised tissue margins at the surgical bedside, closing only when those margins are determined microscopically to be clear. They also have the ability to close larger defects in difficult areas such as this, obtaining an acceptable final result.

Had the patient or situation contraindicated surgery, at least two options would remain. The first is imiquimod (choice “c”) cream, which has a proven ability to destroy basal cell carcinomas (when applied several times a week over a period of six weeks to three months). Uncertain results can, and often do, necessitate a biopsy to confirm total destruction, and the patient has to endure weeks of redness and irritation at the site during treatment.

The other option is radiation therapy (choice “e”), an extremely effective nonsurgical alternative. However, it requires multiple treatment sessions over several weeks and can damage surrounding skin.

About one year ago, this 48-year-old woman noted the appearance of a tiny papule on her left maxilla. It has grown in the interim, becoming of considerable concern to the patient and her husband. They live in the same high desert country where they both were born and raised. As a result, they have been extensively exposed to a great deal of sunlight, and that exposure has been poorly tolerated in both of them. Several family members have been diagnosed with skin cancer, a fact that finally prompts the patient to have this lesion evaluated. She presents to her primary care provider, who in turn refers her to dermatology. The patient is otherwise fairly healthy. However, she is overweight and has hypertension, which is controlled with medication. On examination, the patient’s red hair, blue eyes, and fair skin are noted, along with signs of past sun damage, including solar lentigines and telangiectasias. The lesion in question is a fairly impressive planar 7.5-mm glassy, telangiectatic nodule with a central area of erosion. It is located on the lower left maxilla, about 3 mm above the vermillion border. The lesion is not tender to palpation but is quite firm. Systematic evaluation of the rest of the patient’s face, ears, and neck reveals no other suspicious findings. Shave biopsy is performed, with the results verifying the suspected diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. The patient is then presented with treatment options—at which point she expresses great concern over the cosmetic outcome of the lesion’s removal and her desire to be rid of all the cancer. Given these concerns, as well as the diagnosis in question, treatment options might reasonably include all except which of the following?

Two Years of Treatment Fails to Resolve Symptoms

ANSWER

The correct choice is iatrogenic (choice “a”)—that is, provider-caused—in this case, the result of prolonged application of a relatively powerful steroid cream. Such use eventuates in what is sometimes termed “steroid addiction.” These patients are often wrongly suspected of being alcoholics (choice “b”) because of their red faces, but there was no reason to suspect that in this case. It is thought that bacteria flourish on steroid-treated skin, which is theorized to worsen rosacea; however, this is not an outright infection (choice “c”). Nor is it the result of using the wrong soap on the face (choice “d”), as irritation from soap would not have been limited to such sharply demarcated areas.

DISCUSSION

The injudicious application of topical steroids can have a number of negative effects, all demonstrated in this case. It thins the skin, literally uncovering normally hidden vasculature, which manifests as telangiectasia. The epidermis turns atrophic and shiny, and a rosacea-like eruption (so-called “iatrosacea”) often appears.

But the worst adverse effect is the one that forces the patient to keep using the medication long after the treated condition has disappeared: Burning and itching ensue immediately if the application stops or is reduced. This is especially true for atopic patients who are born with thin skin, and even more so for relatively thin facial skin. Eyelids and perioral areas are especially prone to this reaction, and it is often the fault of the prescribing provider who refills the medication over and over, while failing to educate patients about its potentially deleterious effects.

The differential diagnosis for this common condition includes contact versus irritant dermatitis (patients often make rosacea worse by applying numerous OTC products, such as triple-antibiotic ointment), rosacea, granulomatous faciale, and discoid lupus.

TREATMENT

Treatment in such cases begins with cessation of the steroid and a switch either to a steroid preparation of lower potency (such as hydrocortisone 2.5%) or better yet, to a calcineurin inhibitor (such as pimecrolimus or tacrolimus). In addition, oral tetracycline (500 mg bid) may be taken until the condition begins to improve markedly—a process that can take months. The latter treatment should be slowly tapered to one dose per day, then stopped only when the problem has totally cleared. These patients often need frequent return visits initially for reassurance and re-education

ANSWER

The correct choice is iatrogenic (choice “a”)—that is, provider-caused—in this case, the result of prolonged application of a relatively powerful steroid cream. Such use eventuates in what is sometimes termed “steroid addiction.” These patients are often wrongly suspected of being alcoholics (choice “b”) because of their red faces, but there was no reason to suspect that in this case. It is thought that bacteria flourish on steroid-treated skin, which is theorized to worsen rosacea; however, this is not an outright infection (choice “c”). Nor is it the result of using the wrong soap on the face (choice “d”), as irritation from soap would not have been limited to such sharply demarcated areas.

DISCUSSION

The injudicious application of topical steroids can have a number of negative effects, all demonstrated in this case. It thins the skin, literally uncovering normally hidden vasculature, which manifests as telangiectasia. The epidermis turns atrophic and shiny, and a rosacea-like eruption (so-called “iatrosacea”) often appears.

But the worst adverse effect is the one that forces the patient to keep using the medication long after the treated condition has disappeared: Burning and itching ensue immediately if the application stops or is reduced. This is especially true for atopic patients who are born with thin skin, and even more so for relatively thin facial skin. Eyelids and perioral areas are especially prone to this reaction, and it is often the fault of the prescribing provider who refills the medication over and over, while failing to educate patients about its potentially deleterious effects.

The differential diagnosis for this common condition includes contact versus irritant dermatitis (patients often make rosacea worse by applying numerous OTC products, such as triple-antibiotic ointment), rosacea, granulomatous faciale, and discoid lupus.

TREATMENT

Treatment in such cases begins with cessation of the steroid and a switch either to a steroid preparation of lower potency (such as hydrocortisone 2.5%) or better yet, to a calcineurin inhibitor (such as pimecrolimus or tacrolimus). In addition, oral tetracycline (500 mg bid) may be taken until the condition begins to improve markedly—a process that can take months. The latter treatment should be slowly tapered to one dose per day, then stopped only when the problem has totally cleared. These patients often need frequent return visits initially for reassurance and re-education

ANSWER

The correct choice is iatrogenic (choice “a”)—that is, provider-caused—in this case, the result of prolonged application of a relatively powerful steroid cream. Such use eventuates in what is sometimes termed “steroid addiction.” These patients are often wrongly suspected of being alcoholics (choice “b”) because of their red faces, but there was no reason to suspect that in this case. It is thought that bacteria flourish on steroid-treated skin, which is theorized to worsen rosacea; however, this is not an outright infection (choice “c”). Nor is it the result of using the wrong soap on the face (choice “d”), as irritation from soap would not have been limited to such sharply demarcated areas.

DISCUSSION

The injudicious application of topical steroids can have a number of negative effects, all demonstrated in this case. It thins the skin, literally uncovering normally hidden vasculature, which manifests as telangiectasia. The epidermis turns atrophic and shiny, and a rosacea-like eruption (so-called “iatrosacea”) often appears.

But the worst adverse effect is the one that forces the patient to keep using the medication long after the treated condition has disappeared: Burning and itching ensue immediately if the application stops or is reduced. This is especially true for atopic patients who are born with thin skin, and even more so for relatively thin facial skin. Eyelids and perioral areas are especially prone to this reaction, and it is often the fault of the prescribing provider who refills the medication over and over, while failing to educate patients about its potentially deleterious effects.

The differential diagnosis for this common condition includes contact versus irritant dermatitis (patients often make rosacea worse by applying numerous OTC products, such as triple-antibiotic ointment), rosacea, granulomatous faciale, and discoid lupus.

TREATMENT

Treatment in such cases begins with cessation of the steroid and a switch either to a steroid preparation of lower potency (such as hydrocortisone 2.5%) or better yet, to a calcineurin inhibitor (such as pimecrolimus or tacrolimus). In addition, oral tetracycline (500 mg bid) may be taken until the condition begins to improve markedly—a process that can take months. The latter treatment should be slowly tapered to one dose per day, then stopped only when the problem has totally cleared. These patients often need frequent return visits initially for reassurance and re-education

Two years ago, this 45-year-old man developed a faint rash on the bilateral malar areas of his cheeks. His primary care provider diagnosed eczema and prescribed triamcinolone 0.1% cream. The patient has applied this cream to the affected areas twice a day for the entire two-year period. Whenever he tries to stop using the medication, the areas begin to itch and burn, invariably causing him to resume use. Frustrated, the patient seeks and obtains a referral to dermatology. Further history taking reveals that the patient has a number of health problems, including type 2 diabetes, mild renal failure, and a lifelong history of atopic dermatitis. He denies excessive alcohol intake and is employed as administrator of information technology for a hospital. On examination, the patient’s cheeks are both bright red, thin-skinned, and shiny, with many fine telangiectasias covering both malar prominences. Scattered sparsely over these areas are discrete red papules ranging in diameter from 1 to 2 mm. The erythema is highly blanchable and slightly warmer than the surrounding uninvolved skin. The rest of the patient’s facial skin is normal in appearance.

Patient Fears She's "Going Bald"

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a biopsy (choice “d”). Although the other choices can be part of the workup for scalp conditions (eg, secondary syphilis, lupus, or fungal infection), the most logical step is to assess the basic histopathologic process. This would provide the clearest direction by revealing characteristic changes in the tissues. Starting an oral antibiotic, such as minocycline, might be a reasonable step if biopsy were not possible.

DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of “scarring alopecia,” a category of hair loss with a wide-ranging differential diagnosis. Included in it would be lymphoma-associated perifollicular mucinosis, discoid lupus, lichen planopilaris (lichen planus affecting the scalp), tinea capitis, secondary syphilis, and pseudopelade. All potentially lead to permanent hair loss; therefore, direct and timely diagnostic information that only a biopsy can provide is essential.

Fungal origin was unlikely for several reasons. Such a diagnosis would be distinctly unusual in a Caucasian woman of this age, particularly since no source (child, spouse, or pet) was identified. The lack of epidermal changes (scale or other broken skin), edema, or adenopathy was a key factor in that regard as well.

In this and most such cases, a 4-mm punch biopsy is taken from the (presumably) active margin of the radially expanding pathologic process; biopsy of the centers would likely only show scar. The biopsy should include at least a few hair shafts, with care taken to penetrate the skin at the same angle from which the hairs emerge. This facilitates collection of the length of the shaft, which could provide valuable diagnostic information.

Done under local anesthesia with lidocaine/epinephrine, the defect is almost always closed with surface sutures, for hemostasis and to speed healing. If one felt strongly about the possibility of infection, an additional sample could be taken and submitted for bacterial and fungal cultures; in this case, neither was suspected.

The results in this case proved the diagnosis of pseudopelade, an inflammatory condition of unknown origin, possibly representing the end-point of either discoid lupus or lichen planopilaris. In any case, the other potential causes of scarring alopecia were ruled out, and appropriate treatment (perilesional injection of 5 mg per cc triamcinolone suspension, oral minocycline 100 mg bid, and topical betamethasone foam) were instituted and follow-up arranged.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a biopsy (choice “d”). Although the other choices can be part of the workup for scalp conditions (eg, secondary syphilis, lupus, or fungal infection), the most logical step is to assess the basic histopathologic process. This would provide the clearest direction by revealing characteristic changes in the tissues. Starting an oral antibiotic, such as minocycline, might be a reasonable step if biopsy were not possible.

DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of “scarring alopecia,” a category of hair loss with a wide-ranging differential diagnosis. Included in it would be lymphoma-associated perifollicular mucinosis, discoid lupus, lichen planopilaris (lichen planus affecting the scalp), tinea capitis, secondary syphilis, and pseudopelade. All potentially lead to permanent hair loss; therefore, direct and timely diagnostic information that only a biopsy can provide is essential.

Fungal origin was unlikely for several reasons. Such a diagnosis would be distinctly unusual in a Caucasian woman of this age, particularly since no source (child, spouse, or pet) was identified. The lack of epidermal changes (scale or other broken skin), edema, or adenopathy was a key factor in that regard as well.

In this and most such cases, a 4-mm punch biopsy is taken from the (presumably) active margin of the radially expanding pathologic process; biopsy of the centers would likely only show scar. The biopsy should include at least a few hair shafts, with care taken to penetrate the skin at the same angle from which the hairs emerge. This facilitates collection of the length of the shaft, which could provide valuable diagnostic information.

Done under local anesthesia with lidocaine/epinephrine, the defect is almost always closed with surface sutures, for hemostasis and to speed healing. If one felt strongly about the possibility of infection, an additional sample could be taken and submitted for bacterial and fungal cultures; in this case, neither was suspected.

The results in this case proved the diagnosis of pseudopelade, an inflammatory condition of unknown origin, possibly representing the end-point of either discoid lupus or lichen planopilaris. In any case, the other potential causes of scarring alopecia were ruled out, and appropriate treatment (perilesional injection of 5 mg per cc triamcinolone suspension, oral minocycline 100 mg bid, and topical betamethasone foam) were instituted and follow-up arranged.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a biopsy (choice “d”). Although the other choices can be part of the workup for scalp conditions (eg, secondary syphilis, lupus, or fungal infection), the most logical step is to assess the basic histopathologic process. This would provide the clearest direction by revealing characteristic changes in the tissues. Starting an oral antibiotic, such as minocycline, might be a reasonable step if biopsy were not possible.

DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of “scarring alopecia,” a category of hair loss with a wide-ranging differential diagnosis. Included in it would be lymphoma-associated perifollicular mucinosis, discoid lupus, lichen planopilaris (lichen planus affecting the scalp), tinea capitis, secondary syphilis, and pseudopelade. All potentially lead to permanent hair loss; therefore, direct and timely diagnostic information that only a biopsy can provide is essential.

Fungal origin was unlikely for several reasons. Such a diagnosis would be distinctly unusual in a Caucasian woman of this age, particularly since no source (child, spouse, or pet) was identified. The lack of epidermal changes (scale or other broken skin), edema, or adenopathy was a key factor in that regard as well.

In this and most such cases, a 4-mm punch biopsy is taken from the (presumably) active margin of the radially expanding pathologic process; biopsy of the centers would likely only show scar. The biopsy should include at least a few hair shafts, with care taken to penetrate the skin at the same angle from which the hairs emerge. This facilitates collection of the length of the shaft, which could provide valuable diagnostic information.

Done under local anesthesia with lidocaine/epinephrine, the defect is almost always closed with surface sutures, for hemostasis and to speed healing. If one felt strongly about the possibility of infection, an additional sample could be taken and submitted for bacterial and fungal cultures; in this case, neither was suspected.

The results in this case proved the diagnosis of pseudopelade, an inflammatory condition of unknown origin, possibly representing the end-point of either discoid lupus or lichen planopilaris. In any case, the other potential causes of scarring alopecia were ruled out, and appropriate treatment (perilesional injection of 5 mg per cc triamcinolone suspension, oral minocycline 100 mg bid, and topical betamethasone foam) were instituted and follow-up arranged.

A 48-year-old woman presents to dermatology with a complaint of hair loss. Distraught, she fears she’s “going bald.” This process began several months ago, when she noted a single area of involvement in the frontal scalp. There are now several asymptomatic areas, which have persisted despite the use of several products prescribed by her primary care provider: topical econazole, triamcinolone cream, and most recently, clobetasol foam. None of these has had any beneficial effect; her existing lesions have slowly expanded in size and number. She denies any history of similar problems or of other skin diseases. In general, her health is quite good, with no joint pain, fever, or malaise. Prior to the onset of this condition, she took no prescription or OTC medications. There is no exposure to new pets or other animals, and no one else in her household is affected. She has been married for more than 25 years, in a mutually monogamous relationship. Blood tests (complete blood count, thyroid, chemistry panel, and antinuclear antibody) have been done by her primary care provider. The results were all normal, shedding no light on the condition’s origins. On examination, four distinct areas of hair loss are seen. They range in size from 3 to 6 cm, are roughly fusiform in shape, and are located from frontal to occipital scalp (all in the central quarter of her scalp). In each of these areas, the hair loss is complete, with a scarlike epithelial surface but no other disruption in the skin. Around the periphery of each lesion, there is a faint pinkish tinge. Other than alopecia, no other changes are palpated. There is no tenderness in the lesions and no palpable adenopathy in nodal locations of the head and neck

Patient, Sister Share Skin Problem

ANSWER

The correct answer is pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE; choice “d”), details of which are discussed below. Eruptive xanthomata (choice “a”) usually present with widespread eruptive papules and/or nodules and are associated with extreme hypertriglyceridemia. There are several different types of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, an inherited defect of connective tissues, but the most common involve hypermobile joints (so-called double-jointedness) and/or cutis laxa, neither of which is present in our patient. Moreover, the skin changes seen in our patient are totally unlike those seen in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Solar elastosis (choice “c”) represents sun-caused basophilic degeneration of the deep dermis and presents with a whitish “chicken skin” look. Most commonly seen on the upper forehead of older men with an extensive history of overexposure to ultraviolet light, it almost never appears in intertriginous or other areas unexposed to sunlight.

DISCUSSION

PXE is an autosomal recessive disease with prevalence estimates ranging from 1:25,000 to 1:100,000. It does not demonstrate racial or geographic predilections, although it appears to have a slight preponderance in females. It typically begins to manifest in the second to third decade of life. This genetic defect results in the improper function of elastin and elastic fibers in the deep dermis, the intima of midsized arteries, and the Bruch membrane in the eye, where characteristic clinical and histopathologic changes occur. Thus, three main organ systems are affected: the skin, the eyes, and the cardiovascular system. However, the manifestations can vary a great deal—even among siblings.

Almost 100% of patients older than 30 eventually show signs of the disease in the eyes, with angioid streaks often becoming symptomatic only after trauma to the eye. The end point is reparative neovascularization, leakage from which can eventuate in hemorrhage, scarring, and loss of vision.

PXE also affects midsized arteries, especially of the extremities, where pathologic changes in the vessel walls lead to the premature formation of atheromatous plaques and eventual claudication, loss of peripheral pulses, hypertension, angina, and myocardial infarction that occur at a much younger age than in the unaffected population. Cerebral ischemic attacks, with the exception of aneurysms, are common with PXE. Gastrointestinal bleeds are common, but PXE does not affect the liver, lung, or kidneys.

“Treatment” for the appearance of PXE-affected skin is nearly nonexistent, but there are steps that should be taken. For example: (1) genetic counseling to assess the risk for future generations, as well as presymptomatic testing; (2) regular, periodic eye examination, including funduscopic examination, as well as advice to avoid heavy lifting, trauma, smoking, or other counterproductive activities; and (3) emphasis on preventive lifestyle choices to avoid cardiovascular complications, with early detection a more attainable goal with continued surveillance.

PXE is only one of several so-called “genodermatoses,” that is, inheritable conditions with dermatologic manifestations. Other examples include neurofibromatosis type 1, the aforementioned Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and epidermolysis bullosa—among many, many others.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE; choice “d”), details of which are discussed below. Eruptive xanthomata (choice “a”) usually present with widespread eruptive papules and/or nodules and are associated with extreme hypertriglyceridemia. There are several different types of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, an inherited defect of connective tissues, but the most common involve hypermobile joints (so-called double-jointedness) and/or cutis laxa, neither of which is present in our patient. Moreover, the skin changes seen in our patient are totally unlike those seen in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Solar elastosis (choice “c”) represents sun-caused basophilic degeneration of the deep dermis and presents with a whitish “chicken skin” look. Most commonly seen on the upper forehead of older men with an extensive history of overexposure to ultraviolet light, it almost never appears in intertriginous or other areas unexposed to sunlight.

DISCUSSION

PXE is an autosomal recessive disease with prevalence estimates ranging from 1:25,000 to 1:100,000. It does not demonstrate racial or geographic predilections, although it appears to have a slight preponderance in females. It typically begins to manifest in the second to third decade of life. This genetic defect results in the improper function of elastin and elastic fibers in the deep dermis, the intima of midsized arteries, and the Bruch membrane in the eye, where characteristic clinical and histopathologic changes occur. Thus, three main organ systems are affected: the skin, the eyes, and the cardiovascular system. However, the manifestations can vary a great deal—even among siblings.

Almost 100% of patients older than 30 eventually show signs of the disease in the eyes, with angioid streaks often becoming symptomatic only after trauma to the eye. The end point is reparative neovascularization, leakage from which can eventuate in hemorrhage, scarring, and loss of vision.

PXE also affects midsized arteries, especially of the extremities, where pathologic changes in the vessel walls lead to the premature formation of atheromatous plaques and eventual claudication, loss of peripheral pulses, hypertension, angina, and myocardial infarction that occur at a much younger age than in the unaffected population. Cerebral ischemic attacks, with the exception of aneurysms, are common with PXE. Gastrointestinal bleeds are common, but PXE does not affect the liver, lung, or kidneys.

“Treatment” for the appearance of PXE-affected skin is nearly nonexistent, but there are steps that should be taken. For example: (1) genetic counseling to assess the risk for future generations, as well as presymptomatic testing; (2) regular, periodic eye examination, including funduscopic examination, as well as advice to avoid heavy lifting, trauma, smoking, or other counterproductive activities; and (3) emphasis on preventive lifestyle choices to avoid cardiovascular complications, with early detection a more attainable goal with continued surveillance.

PXE is only one of several so-called “genodermatoses,” that is, inheritable conditions with dermatologic manifestations. Other examples include neurofibromatosis type 1, the aforementioned Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and epidermolysis bullosa—among many, many others.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE; choice “d”), details of which are discussed below. Eruptive xanthomata (choice “a”) usually present with widespread eruptive papules and/or nodules and are associated with extreme hypertriglyceridemia. There are several different types of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, an inherited defect of connective tissues, but the most common involve hypermobile joints (so-called double-jointedness) and/or cutis laxa, neither of which is present in our patient. Moreover, the skin changes seen in our patient are totally unlike those seen in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Solar elastosis (choice “c”) represents sun-caused basophilic degeneration of the deep dermis and presents with a whitish “chicken skin” look. Most commonly seen on the upper forehead of older men with an extensive history of overexposure to ultraviolet light, it almost never appears in intertriginous or other areas unexposed to sunlight.

DISCUSSION

PXE is an autosomal recessive disease with prevalence estimates ranging from 1:25,000 to 1:100,000. It does not demonstrate racial or geographic predilections, although it appears to have a slight preponderance in females. It typically begins to manifest in the second to third decade of life. This genetic defect results in the improper function of elastin and elastic fibers in the deep dermis, the intima of midsized arteries, and the Bruch membrane in the eye, where characteristic clinical and histopathologic changes occur. Thus, three main organ systems are affected: the skin, the eyes, and the cardiovascular system. However, the manifestations can vary a great deal—even among siblings.

Almost 100% of patients older than 30 eventually show signs of the disease in the eyes, with angioid streaks often becoming symptomatic only after trauma to the eye. The end point is reparative neovascularization, leakage from which can eventuate in hemorrhage, scarring, and loss of vision.

PXE also affects midsized arteries, especially of the extremities, where pathologic changes in the vessel walls lead to the premature formation of atheromatous plaques and eventual claudication, loss of peripheral pulses, hypertension, angina, and myocardial infarction that occur at a much younger age than in the unaffected population. Cerebral ischemic attacks, with the exception of aneurysms, are common with PXE. Gastrointestinal bleeds are common, but PXE does not affect the liver, lung, or kidneys.

“Treatment” for the appearance of PXE-affected skin is nearly nonexistent, but there are steps that should be taken. For example: (1) genetic counseling to assess the risk for future generations, as well as presymptomatic testing; (2) regular, periodic eye examination, including funduscopic examination, as well as advice to avoid heavy lifting, trauma, smoking, or other counterproductive activities; and (3) emphasis on preventive lifestyle choices to avoid cardiovascular complications, with early detection a more attainable goal with continued surveillance.

PXE is only one of several so-called “genodermatoses,” that is, inheritable conditions with dermatologic manifestations. Other examples include neurofibromatosis type 1, the aforementioned Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and epidermolysis bullosa—among many, many others.

A 29-year-old woman presents for evaluation of changes in her skin, which she first noticed during her late teens. The changes have been asymptomatic and slowly progressive, and various providers have given different explanations for them at different times. However, she has never been seen by dermatology prior to this visit, which is ostensibly for treatment of hand warts and eyelid dermatitis. Aside from being somewhat atopic, the patient is in otherwise excellent health. Laboratory work done as part of a recent physical showed her lipid levels to be well within normal limits. A discussion of family history reveals she has a sister with the same type of skin changes; however, she too has never received a definitive diagnosis from any of the many providers who have evaluated her over the years. The patient points to changes in several intertriginous locations, including bilateral neck skin, both antecubital areas, axillae, and crural folds. The skin in those areas has an odd cobblestone-like papularity, appears atrophic, and is light yellow. The changes are barely palpable. The midline posterior neck is spared, but the same changes can be seen on oral mucosal surfaces. Elsewhere, there are no signs of hypermobile joints or of cutis laxa. No evidence of excessive sun exposure is observed. Several punch biopsies show distorted, fragmented elastic fibers in the mid to deep reticular dermis.

Common "Lesion" Leads to Rare Diagnosis

ANSWER

The one incorrect statement is choice “a,” since morphea does not progress into systemic sclerosis (SS), although the local histologic process is almost identical in each. Morphea—especially in children, and especially with linear types that course over crucial structures such as joints or faces—can interfere with normal function and growth, making choice “b” correct. Several theories have arisen to explain the genesis of this disease, including an autoimmune basis; to date, none has been proven, so both choice “c” and choice “d” are technically correct.

DISCUSSION

This case is a perfect example of an established maxim of dermatology: One seldom diagnoses what one has never heard of. The reported incidence of morphea is 25 cases per one million Americans, but it is a common enough complaint in dermatology practices.

Although the precise cause is unknown, there is general agreement that morphea represents localized dysregulation of collagen synthesis and deposition in the dermis. While that process is identical to that seen in SS, the two are otherwise not part of the same clinical continuum—good news for the morphea patient, since SS is a far more serious disease. Morphea patients do not, for example, experience the components of SS such as Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, or involvement of internal organs, nor do they share the potentially dire prognosis of SS patients.

Morphea takes several clinical forms; the most common is the plaque type, which typically presents as an annular lesion on the trunk or extremity, with the potential to grow to considerable size. Most will stop growing in time, but the discolored “burnt-out” lesion remains, leaving a purplish brown atrophic area.

Another form of morphea is a linear configuration. This is seen particularly in children, in whom it can interfere with normal growth and function. Examples include the morphea variants Parry-Romberg syndrome and en coup de sabre; both appear on the face, and deeper structures such as soft tissue and bone can be affected.

TREATMENT

This patient has advanced disease, for which calcipotriene cream (to be applied bid for two months) was prescribed, with follow-up to monitor his disease and its effect on the joint as well as the skin. Other medications have been tried for morphea, including minocycline and methotrexate, with decidedly mixed results.

ANSWER

The one incorrect statement is choice “a,” since morphea does not progress into systemic sclerosis (SS), although the local histologic process is almost identical in each. Morphea—especially in children, and especially with linear types that course over crucial structures such as joints or faces—can interfere with normal function and growth, making choice “b” correct. Several theories have arisen to explain the genesis of this disease, including an autoimmune basis; to date, none has been proven, so both choice “c” and choice “d” are technically correct.

DISCUSSION

This case is a perfect example of an established maxim of dermatology: One seldom diagnoses what one has never heard of. The reported incidence of morphea is 25 cases per one million Americans, but it is a common enough complaint in dermatology practices.

Although the precise cause is unknown, there is general agreement that morphea represents localized dysregulation of collagen synthesis and deposition in the dermis. While that process is identical to that seen in SS, the two are otherwise not part of the same clinical continuum—good news for the morphea patient, since SS is a far more serious disease. Morphea patients do not, for example, experience the components of SS such as Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, or involvement of internal organs, nor do they share the potentially dire prognosis of SS patients.

Morphea takes several clinical forms; the most common is the plaque type, which typically presents as an annular lesion on the trunk or extremity, with the potential to grow to considerable size. Most will stop growing in time, but the discolored “burnt-out” lesion remains, leaving a purplish brown atrophic area.

Another form of morphea is a linear configuration. This is seen particularly in children, in whom it can interfere with normal growth and function. Examples include the morphea variants Parry-Romberg syndrome and en coup de sabre; both appear on the face, and deeper structures such as soft tissue and bone can be affected.

TREATMENT

This patient has advanced disease, for which calcipotriene cream (to be applied bid for two months) was prescribed, with follow-up to monitor his disease and its effect on the joint as well as the skin. Other medications have been tried for morphea, including minocycline and methotrexate, with decidedly mixed results.

ANSWER

The one incorrect statement is choice “a,” since morphea does not progress into systemic sclerosis (SS), although the local histologic process is almost identical in each. Morphea—especially in children, and especially with linear types that course over crucial structures such as joints or faces—can interfere with normal function and growth, making choice “b” correct. Several theories have arisen to explain the genesis of this disease, including an autoimmune basis; to date, none has been proven, so both choice “c” and choice “d” are technically correct.

DISCUSSION

This case is a perfect example of an established maxim of dermatology: One seldom diagnoses what one has never heard of. The reported incidence of morphea is 25 cases per one million Americans, but it is a common enough complaint in dermatology practices.

Although the precise cause is unknown, there is general agreement that morphea represents localized dysregulation of collagen synthesis and deposition in the dermis. While that process is identical to that seen in SS, the two are otherwise not part of the same clinical continuum—good news for the morphea patient, since SS is a far more serious disease. Morphea patients do not, for example, experience the components of SS such as Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, or involvement of internal organs, nor do they share the potentially dire prognosis of SS patients.

Morphea takes several clinical forms; the most common is the plaque type, which typically presents as an annular lesion on the trunk or extremity, with the potential to grow to considerable size. Most will stop growing in time, but the discolored “burnt-out” lesion remains, leaving a purplish brown atrophic area.

Another form of morphea is a linear configuration. This is seen particularly in children, in whom it can interfere with normal growth and function. Examples include the morphea variants Parry-Romberg syndrome and en coup de sabre; both appear on the face, and deeper structures such as soft tissue and bone can be affected.

TREATMENT

This patient has advanced disease, for which calcipotriene cream (to be applied bid for two months) was prescribed, with follow-up to monitor his disease and its effect on the joint as well as the skin. Other medications have been tried for morphea, including minocycline and methotrexate, with decidedly mixed results.

For five years, a 12-year-old boy has had an expanding, asymptomatic lesion on his left thigh and knee. There was no known precipitating event—no trauma or insect bite. No other areas are involved. The boy’s health is otherwise good. On examination, a 20 x 10–cm “lesion” is noted on the left medial thigh and knee. The entire area is surprisingly firm to the touch and is brownish blue, with a sclerotic look and feel. There is a central area of depression that, at its deepest, is at least 2 cm lower than the surrounding skin. The area is covered by a cicatricial fusiform plaque measuring 8 x 3 cm. The overlying skin is remarkably smooth. The courses of the subcutaneous venous plexus can be easily traced through the atrophic skin. The pathologic process covers the medial thigh, crosses the joint, and is (based on the history) extending inferiorly in a somewhat linear configuration. No other areas of involvement are appreciated, and the patient’s skin is otherwise normal. In an effort to avoid the creation of a nonhealing wound, a 5-mm punch biopsy is performed on the wall of the depressed area, avoiding the central cicatricial portion. The results are as follows: thickening and homogenization of collagen bundles concentrated in the lower reticular dermis. It therefore seems clear that the diagnosis is morphea. Which of the following statements about this condition is false?

An Unexpected Effect of Crohn's

ANSWER

The correct answer is Sweet’s syndrome (choice “a”), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Read on for a discussion of this condition.

Mastocytosis (choice “b”) can present with solitary lesions (“mastocytoma”), but biopsy would have shown a marked increase in mast cells, not the mature polymorphonuclear leukocytes seen in this biopsy. Pyoderma gangrenosum (choice “c”) lesions eventually ulcerate, and biopsy would have revealed a mixed infiltrate instead of the purely neutrophilic one seen. Cellulitis (choice “d”) would have manifested acutely, quickly becoming suppurative, in contrast to the persistence seen with this lesion.

DISCUSSION/TREATMENT

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in 1964 and has since been organized into three basic categories: the classic type, often idiopathic since most cases are of unknown origin; malignancy-associated, typically hematologic (eg, myelogenous leukemia); and drug induced, which was first described in association with sulfa-trimethoprim.