User login

Measures of Success

The headlines are harrowing: corporate layoffs; foreclosures on the rise; 401(k) retirement plans halved; government bailouts adding to the national debt. The worst economic downturn since the Great Depression has generated some unexpected outcomes, yet not all of them are bad for hospitalists. Below, four vignettes highlight HM groups that have achieved success despite—or in some cases because of—these troubled times.

A Better Business Agreement

It has taken nearly two years—and sometimes as many as four meetings a week—but Rajeev Alexander, MD, and his colleagues are nearing the finish line of an evolving business arrangement. The new arrangement has come about due to the economic downturn, which forced Oregon Medical Group (OMG), a multispecialty physician group serving hospitals in the Eugene/Springfield area and the HM group’s employer since 1988, to want to divest themselves of the hospitalist group. Now, after a lengthy negotiation, Dr. Alexander’s group of eight hospitalists is busier than ever.

Through what were essentially multiple quasi-buyouts, divestitures, and mergers, Dr. Alexander’s hospitalist group “spun off” from OMG and affiliated with PeaceHealth, a nonprofit health system serving seven hospitals in Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. The new contract means Dr. Alexander’s group is directly employed by Sacred Heart Hospital, a 541-bed PeaceHealth-owned facility in Eugene.

The new contract included a non-compete clause with OMG, which currently employs five hospitalists, yet Dr. Alexander’s group has maintained its patient volume. Compensation held steady and employee benefits improved. During an independent and slow-moving negotiation, Dr. Alexander’s group has merged with another HM service that originally was employed by PeaceHealth. The two HM groups (technically competitors) now practice in the same hospital and are ironing out the terms of the merger. At the moment, the groups have created a mutually respectful joint governance council.

“We’ve tackled the thorniest of problems,” Dr. Alexander says, “first, creating a combined work schedule to distribute patients and divide the work. Those of us on the governance council figured if we could get the docs to actually work together and share patients and communicate with each other as if they were one group, then the momentum for an actual administrative/contractual merger would feel inevitable.”

Although negotiations are expected to last through the end of the year to finalize such details as compensation, recruiting, and a group mission statement, the medical staff at Sacred Heart considers the merger a “done deal” and has thrown its support behind the effort. “Community outpatient docs have been clamoring for our services, and we have been having to hand out numbers and ask them to wait in line, so to speak,” Dr. Alexander says.

Dr. Alexander says he’s learned some lessons through the extensive negotiation process:

- Stay positive. In any business venture, absolutely nothing is impossible, even dodging a noncompete clause.

- Release your preconceptions. Conspiracy theories might abound, but most hospital administrators have the best of intentions. As highly regulated organizations, hospitals might simply be following their own bylaws and fulfilling responsibilities to stakeholders. Seek out at least one administrator whom you can trust, and with whom you can communicate effectively. A mutual understanding of intentions and objectives makes the process more successful for all concerned.

- Look beyond politics. Your trust and respect for administrators and fellow physicians will go a long way toward overcoming obstacles.

- Stick to your plan. Adhere to your goal of remaining independent, if that is important to you. “Our group resisted being funneled into becoming employed by a very large national hospitalist chain,” Dr. Alexander says, “and I would encourage physicians in other parts of the country to stick to their commitments as well.”

- Trust the negotiation process. Even if all goes well, what you’re shooting for at the beginning might not be exactly what you get after negotiations are over. This does not mean you’ve failed, or that hospital administration tricked you or failed to deliver on promises. It simply means you have created a negotiated settlement; both sides have come to a new appreciation for the other’s requirements and have made necessary and respectful accommodations.

Rural Rewards

Based in Traverse City, Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan (HNM) services four community hospitals and continues to witness solid growth. Since 2000, the group has grown from nine to nearly 40 providers, and from 2005 to 2008, patient encounters doubled. “In these hard economic times, hospitals are inviting us in because we provide value to the hospitals through leadership, increased hospital revenues, and improved recruiting and retention of specialists,” says Troy W. Ahlstrom, MD, president of HNM. “We continue to see healthy growth in patient volume as we align patient care goals with the needs of the hospitals and surrounding communities we serve.”

HNM, which established a service at the regional medical center and then assumed management of HM programs at three other rural hospitals, soon will add a fifth service to its ledger. HNM also began a pediatric program at the regional referral center, and the group is exploring the possibility of providing a network of pediatric care throughout the region.

Having grown up in the region, David Friar, MD, CEO of HNM, not only has a better understanding of the needs of rural hospitals, but also a personal investment in his group’s success. “These are our communities. We don’t view the hospitals as just a place to make a profit, but a place where our neighbors work and our families get their care,” he says.

Drs. Ahlstrom and Friar offer the following advice for achieving success in these economic times:

- Optimize receipts. Concern over compliance audits leads many hospitals to sacrifice group receipts by encouraging undercoding. “We’ve found hospitals do a poor job of negotiating the provider portion of third-party payer contracts and frequently lose provider charges because they focus on the much larger facility fees,” says Dr. Ahlstrom. The group’s receipts increased more than 30% when they began using an outside billing firm and adopted productivity incentives to encourage providers to practice better documentation and charge capture. Improving documentation also supports a hospital’s ability to accurately code its patients, which allows a hospital to bill for a more profitable diagnosis-related group (DRG), and improve its case-mix index. With these changes, Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan has increased provider pay and grown their practice while improving the hospitals’ profitability.

- Encourage frugality. The cost-plus model is popular, but it doesn’t incentivize programs to contain costs. In contrast, the fixed-price model encourages hospitalists to find cheaper ways to provide good care. “Because the money we save goes to us, we’ve all found creative ways to provide quality care for a third less money than similar cost-plus programs,” Dr. Ahlstrom says.

- Align incentives. Hospitals live or die on thin margins, Dr. Ahlstrom says. His group trains its employees to ask: What can I do to make the hospital stronger? “What’s good for the hospital is good for us, so we work with the hospitals, not for the hospitals,” Dr. Friar says.

At its smaller hospitals, HNM incentivized orthopedic admissions so that more surgical cases would stay local. Hospitalists were trained to perform stress tests so the hospital can provide testing on weekends. The group pays hospitalists a bonus for each admission, so when the ED calls, the hospitalists say, “Thanks! I’ll be right there.” The group also increased staffing on weekends.

The end result: It improves the hospital’s bottom line by shortening length of stay, and improving quality of care, patient satisfaction, and group morale.

“When we align the incentives, everybody wins,” says Dr. Friar. “The system has more capacity, the patients get better care, and the hospitalists no longer feel that weekend shifts are a huge burden.”

- Build “system-ness.” Sharing providers between hospitals has helped HNM build a cohesive system of quality care. What began as a way to cover shifts has created an interinstitutional camaraderie that allows for the easier flow of patients, improved communication, and widespread use of best-practice models. Sharing such resources as billing, credentialing, benefits, recruiting, and payroll has helped the group stay competitive, Dr. Ahlstrom says.

Growth in a Down Economy

Jude R. Alexander, MD, president of Inpatient Specialists in Rockville, Md., a bedroom community about 12 miles northwest of Washington, D.C., has continued to grow his group despite the down economy. Hospital admissions in the D.C. area decreased sharply in the second half of 2008, and patient volume rebounded slowly in the first half of 2009.

Inpatient Specialists initially downsized its staff, then it used flex physicians to meet demand as volume increased.

Despite national hospital trends of budget shortfalls, downgraded bond ratings, and increases in uninsured patients, two of Inpatient Specialists’ client hospitals chose to invest in the HM program. Dr. Alexander credits the vote of confidence to his group’s track record of optimal resource utilization, which has inherent cost savings in the millions.

Dr. Alexander also recommends HM groups in tough economic circumstances should:

- Maintain good relationships with partner hospitals;

- Run a lean business;

- Focus on excellent customer service to patients, their families, and their PCPs; and

- Build strong alliances with employed physicians by eliciting and giving constructive feedback.

“Following this basic strategy, Inpatient Specialists has experienced 7% growth in patient volume in the past 12 months,” Dr. Alexander says. “We’ve expanded to 40 full-time equivalent hospitalists, and 40 part-time employees.” Inpatient Specialists has its eye on geographic expansion, as well. The group is targeting services throughout the Capitol region—Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

Bankruptcy to Profitability in One Year

In 2007, a few months after the 99-bed Auburn Memorial Hospital in Auburn, N.Y., was forced into bankruptcy, James Leyhane, MD, and his hospitalist group were displeased that they weren’t in control of their own program. Physicians had started leaving the hospital; Dr. Leyhane himself had interviewed at another hospital. “Our CEO approached me to ask what would make it right,” Dr. Leyhane recalls. “I said, ‘We’d need to be employed by the hospital.’ ”

The hospital and the private, six-physician internal-medicine group that employed the program entered bids on the HM group. In March 2008, the HM group became contractually employed by the hospital. Dr. Leyhane was given full control as hospitalist director of Auburn Memorial Hospitalists.

As a result of the new alignment, two major shifts took place. First, the hospital CEO more aggressively recruited subspecialists and surgeons. With the HM group now affiliated with the hospital, recruiting surgeons to Auburn Memorial became much easier. Second, more primary-care physicians (PCPs) began sending their patients to Auburn Memorial.

“We were all shocked at how quickly the administration was able to recruit new subspecialists to the area,” Dr. Leyhane says. “That helped get the profitable procedures back to the hospital.”

The biggest surprise came at the end of 2008. Patient volume had risen 11.5% higher than the hospital’s best-case predictions. “As a result of our emerging from under the umbrella of one physician group, the outlying physicians became less fearful that they might lose their patients to that group,” Dr. Leyhane says. “And in good faith, we still maintain a coverage arrangement with that IM group.”

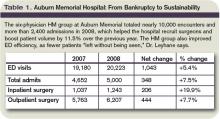

Thus, what was first seen as a bad thing turned into a very good thing for both the hospitalist group and the hospital. Auburn Memorial posted a $3.1 million profit in 2008 (see Table 1).

Dr. Leyhane suggests HM group leaders facing similar financial crunches talk to area subspecialists and find out what it would take to get them affiliated with their institution.

“In our case, a stable hospitalist program was definitely one of their top requests,” Dr. Leyhane says, adding it also would be beneficial to include PCPs in the “what do you want from our hospital?” conversation. TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina.

Image Source: COLIN ANDERSON/GETTYIMAGES

The headlines are harrowing: corporate layoffs; foreclosures on the rise; 401(k) retirement plans halved; government bailouts adding to the national debt. The worst economic downturn since the Great Depression has generated some unexpected outcomes, yet not all of them are bad for hospitalists. Below, four vignettes highlight HM groups that have achieved success despite—or in some cases because of—these troubled times.

A Better Business Agreement

It has taken nearly two years—and sometimes as many as four meetings a week—but Rajeev Alexander, MD, and his colleagues are nearing the finish line of an evolving business arrangement. The new arrangement has come about due to the economic downturn, which forced Oregon Medical Group (OMG), a multispecialty physician group serving hospitals in the Eugene/Springfield area and the HM group’s employer since 1988, to want to divest themselves of the hospitalist group. Now, after a lengthy negotiation, Dr. Alexander’s group of eight hospitalists is busier than ever.

Through what were essentially multiple quasi-buyouts, divestitures, and mergers, Dr. Alexander’s hospitalist group “spun off” from OMG and affiliated with PeaceHealth, a nonprofit health system serving seven hospitals in Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. The new contract means Dr. Alexander’s group is directly employed by Sacred Heart Hospital, a 541-bed PeaceHealth-owned facility in Eugene.

The new contract included a non-compete clause with OMG, which currently employs five hospitalists, yet Dr. Alexander’s group has maintained its patient volume. Compensation held steady and employee benefits improved. During an independent and slow-moving negotiation, Dr. Alexander’s group has merged with another HM service that originally was employed by PeaceHealth. The two HM groups (technically competitors) now practice in the same hospital and are ironing out the terms of the merger. At the moment, the groups have created a mutually respectful joint governance council.

“We’ve tackled the thorniest of problems,” Dr. Alexander says, “first, creating a combined work schedule to distribute patients and divide the work. Those of us on the governance council figured if we could get the docs to actually work together and share patients and communicate with each other as if they were one group, then the momentum for an actual administrative/contractual merger would feel inevitable.”

Although negotiations are expected to last through the end of the year to finalize such details as compensation, recruiting, and a group mission statement, the medical staff at Sacred Heart considers the merger a “done deal” and has thrown its support behind the effort. “Community outpatient docs have been clamoring for our services, and we have been having to hand out numbers and ask them to wait in line, so to speak,” Dr. Alexander says.

Dr. Alexander says he’s learned some lessons through the extensive negotiation process:

- Stay positive. In any business venture, absolutely nothing is impossible, even dodging a noncompete clause.

- Release your preconceptions. Conspiracy theories might abound, but most hospital administrators have the best of intentions. As highly regulated organizations, hospitals might simply be following their own bylaws and fulfilling responsibilities to stakeholders. Seek out at least one administrator whom you can trust, and with whom you can communicate effectively. A mutual understanding of intentions and objectives makes the process more successful for all concerned.

- Look beyond politics. Your trust and respect for administrators and fellow physicians will go a long way toward overcoming obstacles.

- Stick to your plan. Adhere to your goal of remaining independent, if that is important to you. “Our group resisted being funneled into becoming employed by a very large national hospitalist chain,” Dr. Alexander says, “and I would encourage physicians in other parts of the country to stick to their commitments as well.”

- Trust the negotiation process. Even if all goes well, what you’re shooting for at the beginning might not be exactly what you get after negotiations are over. This does not mean you’ve failed, or that hospital administration tricked you or failed to deliver on promises. It simply means you have created a negotiated settlement; both sides have come to a new appreciation for the other’s requirements and have made necessary and respectful accommodations.

Rural Rewards

Based in Traverse City, Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan (HNM) services four community hospitals and continues to witness solid growth. Since 2000, the group has grown from nine to nearly 40 providers, and from 2005 to 2008, patient encounters doubled. “In these hard economic times, hospitals are inviting us in because we provide value to the hospitals through leadership, increased hospital revenues, and improved recruiting and retention of specialists,” says Troy W. Ahlstrom, MD, president of HNM. “We continue to see healthy growth in patient volume as we align patient care goals with the needs of the hospitals and surrounding communities we serve.”

HNM, which established a service at the regional medical center and then assumed management of HM programs at three other rural hospitals, soon will add a fifth service to its ledger. HNM also began a pediatric program at the regional referral center, and the group is exploring the possibility of providing a network of pediatric care throughout the region.

Having grown up in the region, David Friar, MD, CEO of HNM, not only has a better understanding of the needs of rural hospitals, but also a personal investment in his group’s success. “These are our communities. We don’t view the hospitals as just a place to make a profit, but a place where our neighbors work and our families get their care,” he says.

Drs. Ahlstrom and Friar offer the following advice for achieving success in these economic times:

- Optimize receipts. Concern over compliance audits leads many hospitals to sacrifice group receipts by encouraging undercoding. “We’ve found hospitals do a poor job of negotiating the provider portion of third-party payer contracts and frequently lose provider charges because they focus on the much larger facility fees,” says Dr. Ahlstrom. The group’s receipts increased more than 30% when they began using an outside billing firm and adopted productivity incentives to encourage providers to practice better documentation and charge capture. Improving documentation also supports a hospital’s ability to accurately code its patients, which allows a hospital to bill for a more profitable diagnosis-related group (DRG), and improve its case-mix index. With these changes, Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan has increased provider pay and grown their practice while improving the hospitals’ profitability.

- Encourage frugality. The cost-plus model is popular, but it doesn’t incentivize programs to contain costs. In contrast, the fixed-price model encourages hospitalists to find cheaper ways to provide good care. “Because the money we save goes to us, we’ve all found creative ways to provide quality care for a third less money than similar cost-plus programs,” Dr. Ahlstrom says.

- Align incentives. Hospitals live or die on thin margins, Dr. Ahlstrom says. His group trains its employees to ask: What can I do to make the hospital stronger? “What’s good for the hospital is good for us, so we work with the hospitals, not for the hospitals,” Dr. Friar says.

At its smaller hospitals, HNM incentivized orthopedic admissions so that more surgical cases would stay local. Hospitalists were trained to perform stress tests so the hospital can provide testing on weekends. The group pays hospitalists a bonus for each admission, so when the ED calls, the hospitalists say, “Thanks! I’ll be right there.” The group also increased staffing on weekends.

The end result: It improves the hospital’s bottom line by shortening length of stay, and improving quality of care, patient satisfaction, and group morale.

“When we align the incentives, everybody wins,” says Dr. Friar. “The system has more capacity, the patients get better care, and the hospitalists no longer feel that weekend shifts are a huge burden.”

- Build “system-ness.” Sharing providers between hospitals has helped HNM build a cohesive system of quality care. What began as a way to cover shifts has created an interinstitutional camaraderie that allows for the easier flow of patients, improved communication, and widespread use of best-practice models. Sharing such resources as billing, credentialing, benefits, recruiting, and payroll has helped the group stay competitive, Dr. Ahlstrom says.

Growth in a Down Economy

Jude R. Alexander, MD, president of Inpatient Specialists in Rockville, Md., a bedroom community about 12 miles northwest of Washington, D.C., has continued to grow his group despite the down economy. Hospital admissions in the D.C. area decreased sharply in the second half of 2008, and patient volume rebounded slowly in the first half of 2009.

Inpatient Specialists initially downsized its staff, then it used flex physicians to meet demand as volume increased.

Despite national hospital trends of budget shortfalls, downgraded bond ratings, and increases in uninsured patients, two of Inpatient Specialists’ client hospitals chose to invest in the HM program. Dr. Alexander credits the vote of confidence to his group’s track record of optimal resource utilization, which has inherent cost savings in the millions.

Dr. Alexander also recommends HM groups in tough economic circumstances should:

- Maintain good relationships with partner hospitals;

- Run a lean business;

- Focus on excellent customer service to patients, their families, and their PCPs; and

- Build strong alliances with employed physicians by eliciting and giving constructive feedback.

“Following this basic strategy, Inpatient Specialists has experienced 7% growth in patient volume in the past 12 months,” Dr. Alexander says. “We’ve expanded to 40 full-time equivalent hospitalists, and 40 part-time employees.” Inpatient Specialists has its eye on geographic expansion, as well. The group is targeting services throughout the Capitol region—Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

Bankruptcy to Profitability in One Year

In 2007, a few months after the 99-bed Auburn Memorial Hospital in Auburn, N.Y., was forced into bankruptcy, James Leyhane, MD, and his hospitalist group were displeased that they weren’t in control of their own program. Physicians had started leaving the hospital; Dr. Leyhane himself had interviewed at another hospital. “Our CEO approached me to ask what would make it right,” Dr. Leyhane recalls. “I said, ‘We’d need to be employed by the hospital.’ ”

The hospital and the private, six-physician internal-medicine group that employed the program entered bids on the HM group. In March 2008, the HM group became contractually employed by the hospital. Dr. Leyhane was given full control as hospitalist director of Auburn Memorial Hospitalists.

As a result of the new alignment, two major shifts took place. First, the hospital CEO more aggressively recruited subspecialists and surgeons. With the HM group now affiliated with the hospital, recruiting surgeons to Auburn Memorial became much easier. Second, more primary-care physicians (PCPs) began sending their patients to Auburn Memorial.

“We were all shocked at how quickly the administration was able to recruit new subspecialists to the area,” Dr. Leyhane says. “That helped get the profitable procedures back to the hospital.”

The biggest surprise came at the end of 2008. Patient volume had risen 11.5% higher than the hospital’s best-case predictions. “As a result of our emerging from under the umbrella of one physician group, the outlying physicians became less fearful that they might lose their patients to that group,” Dr. Leyhane says. “And in good faith, we still maintain a coverage arrangement with that IM group.”

Thus, what was first seen as a bad thing turned into a very good thing for both the hospitalist group and the hospital. Auburn Memorial posted a $3.1 million profit in 2008 (see Table 1).

Dr. Leyhane suggests HM group leaders facing similar financial crunches talk to area subspecialists and find out what it would take to get them affiliated with their institution.

“In our case, a stable hospitalist program was definitely one of their top requests,” Dr. Leyhane says, adding it also would be beneficial to include PCPs in the “what do you want from our hospital?” conversation. TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina.

Image Source: COLIN ANDERSON/GETTYIMAGES

The headlines are harrowing: corporate layoffs; foreclosures on the rise; 401(k) retirement plans halved; government bailouts adding to the national debt. The worst economic downturn since the Great Depression has generated some unexpected outcomes, yet not all of them are bad for hospitalists. Below, four vignettes highlight HM groups that have achieved success despite—or in some cases because of—these troubled times.

A Better Business Agreement

It has taken nearly two years—and sometimes as many as four meetings a week—but Rajeev Alexander, MD, and his colleagues are nearing the finish line of an evolving business arrangement. The new arrangement has come about due to the economic downturn, which forced Oregon Medical Group (OMG), a multispecialty physician group serving hospitals in the Eugene/Springfield area and the HM group’s employer since 1988, to want to divest themselves of the hospitalist group. Now, after a lengthy negotiation, Dr. Alexander’s group of eight hospitalists is busier than ever.

Through what were essentially multiple quasi-buyouts, divestitures, and mergers, Dr. Alexander’s hospitalist group “spun off” from OMG and affiliated with PeaceHealth, a nonprofit health system serving seven hospitals in Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. The new contract means Dr. Alexander’s group is directly employed by Sacred Heart Hospital, a 541-bed PeaceHealth-owned facility in Eugene.

The new contract included a non-compete clause with OMG, which currently employs five hospitalists, yet Dr. Alexander’s group has maintained its patient volume. Compensation held steady and employee benefits improved. During an independent and slow-moving negotiation, Dr. Alexander’s group has merged with another HM service that originally was employed by PeaceHealth. The two HM groups (technically competitors) now practice in the same hospital and are ironing out the terms of the merger. At the moment, the groups have created a mutually respectful joint governance council.

“We’ve tackled the thorniest of problems,” Dr. Alexander says, “first, creating a combined work schedule to distribute patients and divide the work. Those of us on the governance council figured if we could get the docs to actually work together and share patients and communicate with each other as if they were one group, then the momentum for an actual administrative/contractual merger would feel inevitable.”

Although negotiations are expected to last through the end of the year to finalize such details as compensation, recruiting, and a group mission statement, the medical staff at Sacred Heart considers the merger a “done deal” and has thrown its support behind the effort. “Community outpatient docs have been clamoring for our services, and we have been having to hand out numbers and ask them to wait in line, so to speak,” Dr. Alexander says.

Dr. Alexander says he’s learned some lessons through the extensive negotiation process:

- Stay positive. In any business venture, absolutely nothing is impossible, even dodging a noncompete clause.

- Release your preconceptions. Conspiracy theories might abound, but most hospital administrators have the best of intentions. As highly regulated organizations, hospitals might simply be following their own bylaws and fulfilling responsibilities to stakeholders. Seek out at least one administrator whom you can trust, and with whom you can communicate effectively. A mutual understanding of intentions and objectives makes the process more successful for all concerned.

- Look beyond politics. Your trust and respect for administrators and fellow physicians will go a long way toward overcoming obstacles.

- Stick to your plan. Adhere to your goal of remaining independent, if that is important to you. “Our group resisted being funneled into becoming employed by a very large national hospitalist chain,” Dr. Alexander says, “and I would encourage physicians in other parts of the country to stick to their commitments as well.”

- Trust the negotiation process. Even if all goes well, what you’re shooting for at the beginning might not be exactly what you get after negotiations are over. This does not mean you’ve failed, or that hospital administration tricked you or failed to deliver on promises. It simply means you have created a negotiated settlement; both sides have come to a new appreciation for the other’s requirements and have made necessary and respectful accommodations.

Rural Rewards

Based in Traverse City, Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan (HNM) services four community hospitals and continues to witness solid growth. Since 2000, the group has grown from nine to nearly 40 providers, and from 2005 to 2008, patient encounters doubled. “In these hard economic times, hospitals are inviting us in because we provide value to the hospitals through leadership, increased hospital revenues, and improved recruiting and retention of specialists,” says Troy W. Ahlstrom, MD, president of HNM. “We continue to see healthy growth in patient volume as we align patient care goals with the needs of the hospitals and surrounding communities we serve.”

HNM, which established a service at the regional medical center and then assumed management of HM programs at three other rural hospitals, soon will add a fifth service to its ledger. HNM also began a pediatric program at the regional referral center, and the group is exploring the possibility of providing a network of pediatric care throughout the region.

Having grown up in the region, David Friar, MD, CEO of HNM, not only has a better understanding of the needs of rural hospitals, but also a personal investment in his group’s success. “These are our communities. We don’t view the hospitals as just a place to make a profit, but a place where our neighbors work and our families get their care,” he says.

Drs. Ahlstrom and Friar offer the following advice for achieving success in these economic times:

- Optimize receipts. Concern over compliance audits leads many hospitals to sacrifice group receipts by encouraging undercoding. “We’ve found hospitals do a poor job of negotiating the provider portion of third-party payer contracts and frequently lose provider charges because they focus on the much larger facility fees,” says Dr. Ahlstrom. The group’s receipts increased more than 30% when they began using an outside billing firm and adopted productivity incentives to encourage providers to practice better documentation and charge capture. Improving documentation also supports a hospital’s ability to accurately code its patients, which allows a hospital to bill for a more profitable diagnosis-related group (DRG), and improve its case-mix index. With these changes, Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan has increased provider pay and grown their practice while improving the hospitals’ profitability.

- Encourage frugality. The cost-plus model is popular, but it doesn’t incentivize programs to contain costs. In contrast, the fixed-price model encourages hospitalists to find cheaper ways to provide good care. “Because the money we save goes to us, we’ve all found creative ways to provide quality care for a third less money than similar cost-plus programs,” Dr. Ahlstrom says.

- Align incentives. Hospitals live or die on thin margins, Dr. Ahlstrom says. His group trains its employees to ask: What can I do to make the hospital stronger? “What’s good for the hospital is good for us, so we work with the hospitals, not for the hospitals,” Dr. Friar says.

At its smaller hospitals, HNM incentivized orthopedic admissions so that more surgical cases would stay local. Hospitalists were trained to perform stress tests so the hospital can provide testing on weekends. The group pays hospitalists a bonus for each admission, so when the ED calls, the hospitalists say, “Thanks! I’ll be right there.” The group also increased staffing on weekends.

The end result: It improves the hospital’s bottom line by shortening length of stay, and improving quality of care, patient satisfaction, and group morale.

“When we align the incentives, everybody wins,” says Dr. Friar. “The system has more capacity, the patients get better care, and the hospitalists no longer feel that weekend shifts are a huge burden.”

- Build “system-ness.” Sharing providers between hospitals has helped HNM build a cohesive system of quality care. What began as a way to cover shifts has created an interinstitutional camaraderie that allows for the easier flow of patients, improved communication, and widespread use of best-practice models. Sharing such resources as billing, credentialing, benefits, recruiting, and payroll has helped the group stay competitive, Dr. Ahlstrom says.

Growth in a Down Economy

Jude R. Alexander, MD, president of Inpatient Specialists in Rockville, Md., a bedroom community about 12 miles northwest of Washington, D.C., has continued to grow his group despite the down economy. Hospital admissions in the D.C. area decreased sharply in the second half of 2008, and patient volume rebounded slowly in the first half of 2009.

Inpatient Specialists initially downsized its staff, then it used flex physicians to meet demand as volume increased.

Despite national hospital trends of budget shortfalls, downgraded bond ratings, and increases in uninsured patients, two of Inpatient Specialists’ client hospitals chose to invest in the HM program. Dr. Alexander credits the vote of confidence to his group’s track record of optimal resource utilization, which has inherent cost savings in the millions.

Dr. Alexander also recommends HM groups in tough economic circumstances should:

- Maintain good relationships with partner hospitals;

- Run a lean business;

- Focus on excellent customer service to patients, their families, and their PCPs; and

- Build strong alliances with employed physicians by eliciting and giving constructive feedback.

“Following this basic strategy, Inpatient Specialists has experienced 7% growth in patient volume in the past 12 months,” Dr. Alexander says. “We’ve expanded to 40 full-time equivalent hospitalists, and 40 part-time employees.” Inpatient Specialists has its eye on geographic expansion, as well. The group is targeting services throughout the Capitol region—Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

Bankruptcy to Profitability in One Year

In 2007, a few months after the 99-bed Auburn Memorial Hospital in Auburn, N.Y., was forced into bankruptcy, James Leyhane, MD, and his hospitalist group were displeased that they weren’t in control of their own program. Physicians had started leaving the hospital; Dr. Leyhane himself had interviewed at another hospital. “Our CEO approached me to ask what would make it right,” Dr. Leyhane recalls. “I said, ‘We’d need to be employed by the hospital.’ ”

The hospital and the private, six-physician internal-medicine group that employed the program entered bids on the HM group. In March 2008, the HM group became contractually employed by the hospital. Dr. Leyhane was given full control as hospitalist director of Auburn Memorial Hospitalists.

As a result of the new alignment, two major shifts took place. First, the hospital CEO more aggressively recruited subspecialists and surgeons. With the HM group now affiliated with the hospital, recruiting surgeons to Auburn Memorial became much easier. Second, more primary-care physicians (PCPs) began sending their patients to Auburn Memorial.

“We were all shocked at how quickly the administration was able to recruit new subspecialists to the area,” Dr. Leyhane says. “That helped get the profitable procedures back to the hospital.”

The biggest surprise came at the end of 2008. Patient volume had risen 11.5% higher than the hospital’s best-case predictions. “As a result of our emerging from under the umbrella of one physician group, the outlying physicians became less fearful that they might lose their patients to that group,” Dr. Leyhane says. “And in good faith, we still maintain a coverage arrangement with that IM group.”

Thus, what was first seen as a bad thing turned into a very good thing for both the hospitalist group and the hospital. Auburn Memorial posted a $3.1 million profit in 2008 (see Table 1).

Dr. Leyhane suggests HM group leaders facing similar financial crunches talk to area subspecialists and find out what it would take to get them affiliated with their institution.

“In our case, a stable hospitalist program was definitely one of their top requests,” Dr. Leyhane says, adding it also would be beneficial to include PCPs in the “what do you want from our hospital?” conversation. TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina.

Image Source: COLIN ANDERSON/GETTYIMAGES

Nice to Meet You

Susan Connelly of Fruitland Park, Fla., is a volunteer at her local community hospital who until recently had never heard of a hospitalist. One day, she entered a hospital room and, as she regularly did with patients she visited, asked if there was anything the man in the bed needed.

“I want to know where my doctor is,” the patient said.

“You mean your doctor hasn’t seen you?” Connelly asked.

“No,” he said. “I’m not even sure he knows I’m here.”

Somewhat incredulous, Connelly retrieved the hospital’s physician handbook and helped the patient look up his physician’s phone number. “I didn’t think too much about it,” she says. But the following week, when she appeared at the hospital to volunteer, a supervisor called her into the office. The supervisor asked Connelly about the incident and gently admonished her for encouraging the patient to call his primary-care physician (PCP), as “a hospitalist is working with him now.”

“A what? I had never even heard the term,” Connelly says. She asked her fellow volunteers, known as patient representatives at her hospital, if they had ever heard of a hospitalist. One had, but only because her husband had been admitted for a hospital stay. Concerned, Connelly wrote letters to the editors of two local newspapers. Both were published (see Figure 2, “Familiar Face Gone Missing,” p. 30).

—Robert Centor, MD, associate dean of medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham

“If I am admitted to the hospital, my doctor will most likely ‘dump’ me on what is now called a ‘hospitalist,’ ” she wrote. “Information gathered [by the hospitalist] should be forwarded to your doctor; the key word is ‘should.’ Why develop this long-term relationship with a doctor, if when you really need him, he is not there for you and you are dealing with a stranger?”

Why indeed?

It might not happen with every new admission, but patient fears are a reality. The uncertainty of a hospital stay, a new physician, and new medications can take their toll on the human psyche. Patients are upset with their PCP, the hospital, the system; many times it’s the hospitalist who feels the brunt of their anger. Not only do hospitalists have to calm a patient worried about PCP disconnect, but they also have to reassure the patient that they will be attentive to their needs, provide a high quality of care during the hospital stay, and communicate with their PCP about diagnoses, medications, and follow-up care. Hospitalists should weave in some of the documented plusses a hospitalist brings to the table: shorter length of stays, greater patient access and availability, and improved quality of care.

Although some patients might view hospitalists as “strangers,” HM physicians can learn methods to ease patient anxiety and answer tough questions from patients about the role they play in hospital care.

Restore Confidence

Simple conversations can help hospitalists defuse patient dissatisfaction. When a patient asks why their PCP won’t be seeing them in the hospital, it’s best to begin with a reassuring approach. For example, introduce yourself and say you have reviewed the case with their PCP. You can include key information from their medical history and recent hospitalizations, if appropriate.

Robert Centor, MD, a hospitalist and associate dean of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, suggests a few other key behaviors for initial patient visits. He finds a way to make appropriate physical contact by taking a pulse, checking the heart and lungs, or patting a shoulder to clearly embody the role of the physician in charge.

“And pull up a chair,” he says. “If there is no chair, bring in a chair. But sit down—always.”

Dr. Centor also recommends a transparent approach, “especially in hospital medicine,” he explains. “Be explicit about what you’re thinking, what you’re doing, and why you’re doing it.”1

Transparency can protect you as it informs and comforts patients and their families. For instance, “hospitalized patients are probably hearing from every relative they have and half the friends they have,” Dr. Centor says. “If one of those people is a physician, they may be second-guessing you. You can overcome their wariness by remembering that this is all about bedside manner and the explanations you give them, including discharge instructions.”

Dr. Centor says your bedside manner needs to fit your personality. When you talk to a patient, use language that matches your personality. You can adopt someone else’s introductory script; just make sure to modify it to fit your work environment (see “Strategies to Ease Patient Concerns,” p. 29).

“What Is This?”

Earlier this year, CJ Clarke of Leesburg, Fla., underwent a colonoscopy screening at a local doctor’s office. She had been kept on warfarin (Coumadin) to prevent complications, but after she bled for four days from a puncture sustained during the procedure, she went to the ED. She was admitted, but it wasn’t until the following afternoon that she learned that hospitalists—not her PCP— would be taking care of her.

“This totally unknown guy came in and said he would be filling in for my doctor and communicating with [my PCP],” Clarke says. “It was a weekend, and it turns out the first hospitalist was a substitute hospitalist, so then I got another hospitalist. The first one was subbing for the first hospitalist. I wasn’t exactly mad, but I thought, what is this?”

Clarke thought the first hospitalist was knowledgeable; she took comfort in that. “But the second one was extremely knowledgeable and explained the differences between Coumadin and heparin. He really knew his stuff. He talked to my cardiologist when she came in,” Clarke says. “The only thing that I was sorry about was that my primary didn’t seem to get the information very rapidly.”

Care coordination is a vital step in the discharge process, especially when patients think the flow of information between a hospital and a PCP is immediate and seamless. When Clarke was discharged and she returned home, she scheduled an appointment with her PCP. “When I first called, my [PCP] had not even heard I had been admitted,” Clarke says. But by the time she visited the PCP, “she knew everything. … I think it would have been good if sometime during that five-day hospitalization, she had been told—not afterward. Not that she would have come in, because that is not her policy, but just to know she knew.”

HM’s Role: Extended Education

Many HM groups have designated policies for educating patients and assuaging their fears. Because some PCPs might feel left out of the loop when hospitalists care for their patients, these strategies go beyond patient education.

One of the first steps is to involve PCPs in meaningful ways in their patients’ hospital care. When a patient is particularly angered by his PCP’s absence, invite the PCP to visit, or call the PCP more often and let the patient know you’re doing so. As proposed by Bob Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, a former SHM president, and author of the blog “Wachter’s World,” and Steven Pantilat, MD, FHM, professor of clinical medicine in the division of hospital medicine at UCSF, and a former SHM president, “the PCP can endorse the hospitalist model and the individual hospitalist, notice subtle findings that differ from the patient’s baseline, and help clarify patient preferences regarding difficult situations by drawing on their previous relationship with the patient. This visit may also benefit the PCP by providing insights into the patient’s illness, personality, or social support that he or she was unaware of previously.”2,3

Cogent Healthcare uses an outreach program to calm patient fears and connect with PCPs. The Brentwood, Tenn.-based hospitalist company distributes patient education pamphlets to the PCPs with whom they work, and distributes a flier on admission to show patients the photographs and names of their HM team (see “Make Patient Education A Priority,” p. 29).

Hospitalist training in this arena helps prepare physicians for a potentially uncomfortable work environment. “We need to stress in residency training the specific issue of helping make the patient feel comfortable when their own doctor is not seeing them in the hospital,” Dr. Centor says. “Most young hospitalists right out of their residencies have not experienced primary-care practice, and, so far, we don’t know how to get around that.”

Hospitalist groups also should consider broad initiatives to bring hospitalists together with patient representatives and other volunteers who work with patients. If volunteers are ignored in the educational outreach process, it could exacerbate patients’ negative reactions. Teach volunteers what hospitalists are, their benefit to care delivery, and their value in upholding the mission of quality HM. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina.

References

- Centor RM. A hospitalist inpatient system does not improve patient care outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1257-1258.

- Lo B. Ethical and policy implications of hospitalist systems. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4):281-290.

- Wachter RM, Pantilat SZ. The “continuity visit” and the hospitalist model of care. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4): 267-272.

Image Source: PETRI ARTTURI ASIKAINEN / GETTY IMAGES

Susan Connelly of Fruitland Park, Fla., is a volunteer at her local community hospital who until recently had never heard of a hospitalist. One day, she entered a hospital room and, as she regularly did with patients she visited, asked if there was anything the man in the bed needed.

“I want to know where my doctor is,” the patient said.

“You mean your doctor hasn’t seen you?” Connelly asked.

“No,” he said. “I’m not even sure he knows I’m here.”

Somewhat incredulous, Connelly retrieved the hospital’s physician handbook and helped the patient look up his physician’s phone number. “I didn’t think too much about it,” she says. But the following week, when she appeared at the hospital to volunteer, a supervisor called her into the office. The supervisor asked Connelly about the incident and gently admonished her for encouraging the patient to call his primary-care physician (PCP), as “a hospitalist is working with him now.”

“A what? I had never even heard the term,” Connelly says. She asked her fellow volunteers, known as patient representatives at her hospital, if they had ever heard of a hospitalist. One had, but only because her husband had been admitted for a hospital stay. Concerned, Connelly wrote letters to the editors of two local newspapers. Both were published (see Figure 2, “Familiar Face Gone Missing,” p. 30).

—Robert Centor, MD, associate dean of medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham

“If I am admitted to the hospital, my doctor will most likely ‘dump’ me on what is now called a ‘hospitalist,’ ” she wrote. “Information gathered [by the hospitalist] should be forwarded to your doctor; the key word is ‘should.’ Why develop this long-term relationship with a doctor, if when you really need him, he is not there for you and you are dealing with a stranger?”

Why indeed?

It might not happen with every new admission, but patient fears are a reality. The uncertainty of a hospital stay, a new physician, and new medications can take their toll on the human psyche. Patients are upset with their PCP, the hospital, the system; many times it’s the hospitalist who feels the brunt of their anger. Not only do hospitalists have to calm a patient worried about PCP disconnect, but they also have to reassure the patient that they will be attentive to their needs, provide a high quality of care during the hospital stay, and communicate with their PCP about diagnoses, medications, and follow-up care. Hospitalists should weave in some of the documented plusses a hospitalist brings to the table: shorter length of stays, greater patient access and availability, and improved quality of care.

Although some patients might view hospitalists as “strangers,” HM physicians can learn methods to ease patient anxiety and answer tough questions from patients about the role they play in hospital care.

Restore Confidence

Simple conversations can help hospitalists defuse patient dissatisfaction. When a patient asks why their PCP won’t be seeing them in the hospital, it’s best to begin with a reassuring approach. For example, introduce yourself and say you have reviewed the case with their PCP. You can include key information from their medical history and recent hospitalizations, if appropriate.

Robert Centor, MD, a hospitalist and associate dean of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, suggests a few other key behaviors for initial patient visits. He finds a way to make appropriate physical contact by taking a pulse, checking the heart and lungs, or patting a shoulder to clearly embody the role of the physician in charge.

“And pull up a chair,” he says. “If there is no chair, bring in a chair. But sit down—always.”

Dr. Centor also recommends a transparent approach, “especially in hospital medicine,” he explains. “Be explicit about what you’re thinking, what you’re doing, and why you’re doing it.”1

Transparency can protect you as it informs and comforts patients and their families. For instance, “hospitalized patients are probably hearing from every relative they have and half the friends they have,” Dr. Centor says. “If one of those people is a physician, they may be second-guessing you. You can overcome their wariness by remembering that this is all about bedside manner and the explanations you give them, including discharge instructions.”

Dr. Centor says your bedside manner needs to fit your personality. When you talk to a patient, use language that matches your personality. You can adopt someone else’s introductory script; just make sure to modify it to fit your work environment (see “Strategies to Ease Patient Concerns,” p. 29).

“What Is This?”

Earlier this year, CJ Clarke of Leesburg, Fla., underwent a colonoscopy screening at a local doctor’s office. She had been kept on warfarin (Coumadin) to prevent complications, but after she bled for four days from a puncture sustained during the procedure, she went to the ED. She was admitted, but it wasn’t until the following afternoon that she learned that hospitalists—not her PCP— would be taking care of her.

“This totally unknown guy came in and said he would be filling in for my doctor and communicating with [my PCP],” Clarke says. “It was a weekend, and it turns out the first hospitalist was a substitute hospitalist, so then I got another hospitalist. The first one was subbing for the first hospitalist. I wasn’t exactly mad, but I thought, what is this?”

Clarke thought the first hospitalist was knowledgeable; she took comfort in that. “But the second one was extremely knowledgeable and explained the differences between Coumadin and heparin. He really knew his stuff. He talked to my cardiologist when she came in,” Clarke says. “The only thing that I was sorry about was that my primary didn’t seem to get the information very rapidly.”

Care coordination is a vital step in the discharge process, especially when patients think the flow of information between a hospital and a PCP is immediate and seamless. When Clarke was discharged and she returned home, she scheduled an appointment with her PCP. “When I first called, my [PCP] had not even heard I had been admitted,” Clarke says. But by the time she visited the PCP, “she knew everything. … I think it would have been good if sometime during that five-day hospitalization, she had been told—not afterward. Not that she would have come in, because that is not her policy, but just to know she knew.”

HM’s Role: Extended Education

Many HM groups have designated policies for educating patients and assuaging their fears. Because some PCPs might feel left out of the loop when hospitalists care for their patients, these strategies go beyond patient education.

One of the first steps is to involve PCPs in meaningful ways in their patients’ hospital care. When a patient is particularly angered by his PCP’s absence, invite the PCP to visit, or call the PCP more often and let the patient know you’re doing so. As proposed by Bob Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, a former SHM president, and author of the blog “Wachter’s World,” and Steven Pantilat, MD, FHM, professor of clinical medicine in the division of hospital medicine at UCSF, and a former SHM president, “the PCP can endorse the hospitalist model and the individual hospitalist, notice subtle findings that differ from the patient’s baseline, and help clarify patient preferences regarding difficult situations by drawing on their previous relationship with the patient. This visit may also benefit the PCP by providing insights into the patient’s illness, personality, or social support that he or she was unaware of previously.”2,3

Cogent Healthcare uses an outreach program to calm patient fears and connect with PCPs. The Brentwood, Tenn.-based hospitalist company distributes patient education pamphlets to the PCPs with whom they work, and distributes a flier on admission to show patients the photographs and names of their HM team (see “Make Patient Education A Priority,” p. 29).

Hospitalist training in this arena helps prepare physicians for a potentially uncomfortable work environment. “We need to stress in residency training the specific issue of helping make the patient feel comfortable when their own doctor is not seeing them in the hospital,” Dr. Centor says. “Most young hospitalists right out of their residencies have not experienced primary-care practice, and, so far, we don’t know how to get around that.”

Hospitalist groups also should consider broad initiatives to bring hospitalists together with patient representatives and other volunteers who work with patients. If volunteers are ignored in the educational outreach process, it could exacerbate patients’ negative reactions. Teach volunteers what hospitalists are, their benefit to care delivery, and their value in upholding the mission of quality HM. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina.

References

- Centor RM. A hospitalist inpatient system does not improve patient care outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1257-1258.

- Lo B. Ethical and policy implications of hospitalist systems. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4):281-290.

- Wachter RM, Pantilat SZ. The “continuity visit” and the hospitalist model of care. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4): 267-272.

Image Source: PETRI ARTTURI ASIKAINEN / GETTY IMAGES

Susan Connelly of Fruitland Park, Fla., is a volunteer at her local community hospital who until recently had never heard of a hospitalist. One day, she entered a hospital room and, as she regularly did with patients she visited, asked if there was anything the man in the bed needed.

“I want to know where my doctor is,” the patient said.

“You mean your doctor hasn’t seen you?” Connelly asked.

“No,” he said. “I’m not even sure he knows I’m here.”

Somewhat incredulous, Connelly retrieved the hospital’s physician handbook and helped the patient look up his physician’s phone number. “I didn’t think too much about it,” she says. But the following week, when she appeared at the hospital to volunteer, a supervisor called her into the office. The supervisor asked Connelly about the incident and gently admonished her for encouraging the patient to call his primary-care physician (PCP), as “a hospitalist is working with him now.”

“A what? I had never even heard the term,” Connelly says. She asked her fellow volunteers, known as patient representatives at her hospital, if they had ever heard of a hospitalist. One had, but only because her husband had been admitted for a hospital stay. Concerned, Connelly wrote letters to the editors of two local newspapers. Both were published (see Figure 2, “Familiar Face Gone Missing,” p. 30).

—Robert Centor, MD, associate dean of medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham

“If I am admitted to the hospital, my doctor will most likely ‘dump’ me on what is now called a ‘hospitalist,’ ” she wrote. “Information gathered [by the hospitalist] should be forwarded to your doctor; the key word is ‘should.’ Why develop this long-term relationship with a doctor, if when you really need him, he is not there for you and you are dealing with a stranger?”

Why indeed?

It might not happen with every new admission, but patient fears are a reality. The uncertainty of a hospital stay, a new physician, and new medications can take their toll on the human psyche. Patients are upset with their PCP, the hospital, the system; many times it’s the hospitalist who feels the brunt of their anger. Not only do hospitalists have to calm a patient worried about PCP disconnect, but they also have to reassure the patient that they will be attentive to their needs, provide a high quality of care during the hospital stay, and communicate with their PCP about diagnoses, medications, and follow-up care. Hospitalists should weave in some of the documented plusses a hospitalist brings to the table: shorter length of stays, greater patient access and availability, and improved quality of care.

Although some patients might view hospitalists as “strangers,” HM physicians can learn methods to ease patient anxiety and answer tough questions from patients about the role they play in hospital care.

Restore Confidence

Simple conversations can help hospitalists defuse patient dissatisfaction. When a patient asks why their PCP won’t be seeing them in the hospital, it’s best to begin with a reassuring approach. For example, introduce yourself and say you have reviewed the case with their PCP. You can include key information from their medical history and recent hospitalizations, if appropriate.

Robert Centor, MD, a hospitalist and associate dean of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, suggests a few other key behaviors for initial patient visits. He finds a way to make appropriate physical contact by taking a pulse, checking the heart and lungs, or patting a shoulder to clearly embody the role of the physician in charge.

“And pull up a chair,” he says. “If there is no chair, bring in a chair. But sit down—always.”

Dr. Centor also recommends a transparent approach, “especially in hospital medicine,” he explains. “Be explicit about what you’re thinking, what you’re doing, and why you’re doing it.”1

Transparency can protect you as it informs and comforts patients and their families. For instance, “hospitalized patients are probably hearing from every relative they have and half the friends they have,” Dr. Centor says. “If one of those people is a physician, they may be second-guessing you. You can overcome their wariness by remembering that this is all about bedside manner and the explanations you give them, including discharge instructions.”

Dr. Centor says your bedside manner needs to fit your personality. When you talk to a patient, use language that matches your personality. You can adopt someone else’s introductory script; just make sure to modify it to fit your work environment (see “Strategies to Ease Patient Concerns,” p. 29).

“What Is This?”

Earlier this year, CJ Clarke of Leesburg, Fla., underwent a colonoscopy screening at a local doctor’s office. She had been kept on warfarin (Coumadin) to prevent complications, but after she bled for four days from a puncture sustained during the procedure, she went to the ED. She was admitted, but it wasn’t until the following afternoon that she learned that hospitalists—not her PCP— would be taking care of her.

“This totally unknown guy came in and said he would be filling in for my doctor and communicating with [my PCP],” Clarke says. “It was a weekend, and it turns out the first hospitalist was a substitute hospitalist, so then I got another hospitalist. The first one was subbing for the first hospitalist. I wasn’t exactly mad, but I thought, what is this?”

Clarke thought the first hospitalist was knowledgeable; she took comfort in that. “But the second one was extremely knowledgeable and explained the differences between Coumadin and heparin. He really knew his stuff. He talked to my cardiologist when she came in,” Clarke says. “The only thing that I was sorry about was that my primary didn’t seem to get the information very rapidly.”

Care coordination is a vital step in the discharge process, especially when patients think the flow of information between a hospital and a PCP is immediate and seamless. When Clarke was discharged and she returned home, she scheduled an appointment with her PCP. “When I first called, my [PCP] had not even heard I had been admitted,” Clarke says. But by the time she visited the PCP, “she knew everything. … I think it would have been good if sometime during that five-day hospitalization, she had been told—not afterward. Not that she would have come in, because that is not her policy, but just to know she knew.”

HM’s Role: Extended Education

Many HM groups have designated policies for educating patients and assuaging their fears. Because some PCPs might feel left out of the loop when hospitalists care for their patients, these strategies go beyond patient education.

One of the first steps is to involve PCPs in meaningful ways in their patients’ hospital care. When a patient is particularly angered by his PCP’s absence, invite the PCP to visit, or call the PCP more often and let the patient know you’re doing so. As proposed by Bob Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, a former SHM president, and author of the blog “Wachter’s World,” and Steven Pantilat, MD, FHM, professor of clinical medicine in the division of hospital medicine at UCSF, and a former SHM president, “the PCP can endorse the hospitalist model and the individual hospitalist, notice subtle findings that differ from the patient’s baseline, and help clarify patient preferences regarding difficult situations by drawing on their previous relationship with the patient. This visit may also benefit the PCP by providing insights into the patient’s illness, personality, or social support that he or she was unaware of previously.”2,3

Cogent Healthcare uses an outreach program to calm patient fears and connect with PCPs. The Brentwood, Tenn.-based hospitalist company distributes patient education pamphlets to the PCPs with whom they work, and distributes a flier on admission to show patients the photographs and names of their HM team (see “Make Patient Education A Priority,” p. 29).

Hospitalist training in this arena helps prepare physicians for a potentially uncomfortable work environment. “We need to stress in residency training the specific issue of helping make the patient feel comfortable when their own doctor is not seeing them in the hospital,” Dr. Centor says. “Most young hospitalists right out of their residencies have not experienced primary-care practice, and, so far, we don’t know how to get around that.”

Hospitalist groups also should consider broad initiatives to bring hospitalists together with patient representatives and other volunteers who work with patients. If volunteers are ignored in the educational outreach process, it could exacerbate patients’ negative reactions. Teach volunteers what hospitalists are, their benefit to care delivery, and their value in upholding the mission of quality HM. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina.

References

- Centor RM. A hospitalist inpatient system does not improve patient care outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1257-1258.

- Lo B. Ethical and policy implications of hospitalist systems. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4):281-290.

- Wachter RM, Pantilat SZ. The “continuity visit” and the hospitalist model of care. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4): 267-272.

Image Source: PETRI ARTTURI ASIKAINEN / GETTY IMAGES

Social Work

Editors’ note: “Alliances” is a new series written about the relationships that hospitalists have with members of the clinical care team—from the team members’ points of view. It’s our hope that each installment of “Alliances” will provide valuable, revealing feedback that hospitalists can use to continually improve their intrateam relationships and, ultimately, patient care.

Social workers are a natural fit with hospitalists and the hospitalist’s strongest allies and staunchest supporters, wrote Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, in his Nov./Dec. 2003 article in The Hospitalist. What makes this collaboration such a positive one and what can members of these two professions learn from each other?

Dr. Flansbaum, a hospitalist and internist with the Division of Internal Medicine/Primary Care at Lenox Hill Hospital, Bronx, N.Y., and a former SHM board member, recently reiterated the benefits of the hospitalist-social worker relationship. In general, he believes that hospitalists provide a unique history-taking perspective that is useful to social workers in their work. Foremost, social workers bring a rich understanding of the available resources that patients need after discharge and a view of the patient’s nonmedical circumstances. Together, the two professionals’ daily interactions generate more effective discharge planning as a part of the multidisciplinary team.

ALWAYS THERE

Amy Lingg, MS, MPA, works on the general medicine unit at Greenwich Hospital (Conn). She says the role of the hospitalist is fairly new at Greenwich. In fact Sabitha Rajan, MD, MS, was the first one at Greenwich Hospital.

In Lingg’s view, nothing can replace the availability of the hospitalist to discuss patient cases, not only with the social worker but also as a team with the patient and family.

“[Attendings] are not there for the moment-by-moment events that happen on the unit, including availability when families are here,” says Lingg. “If I need to speak with a family and the physician’s input is important there, I can just page the hospitalist, she’s here. Whereas with an attending you have to make an appointment; you have to schedule around them. It can become difficult.”

Lingg, who works with hospitalist Dr. Rajan, director of hospitalist services at Greenwich Hospital, cites an example of the benefits of hospitalists’ 24/7 availability: “We had a fairly young woman in her mid-40s who was the divorced mother of a 17-year-old son. The father was not in the picture, and the woman was dying of alcoholic cirrhosis and liver failure. She was Dr. Rajan’s patient. One of the issues was the fact that there was no adult guardian for the son although he was going to be 18 in two months.

“So it involved a lot of talking with friends of the woman, who were sort of stepping in as surrogate guardians to him,” Lingg continues. “There were a lot of logistics [regarding] what would happen with him. We were trying to call the grandfather who was estranged. It was a very, very sensitive, very, very tricky case. It went on for days and days. … Dr. Rajan and I could work on this together on a dayto-day basis, [including] … the counseling, relaying medical knowledge to the family, what was going on clinically, trying to deal with that in a way where she was talking in one way to [the] adults and in a different, more appropriate [for the boy’s age] way to the 17-yearold son. And I can be there to help with that process.”

The situation was resolved to the satisfaction of the mother, the son, the friends, and the providers. “It was really pretty extraordinary,” she said. “I’ve talked about that a couple of times, including at a staff meetings when we were talking about getting new hospitalists. That is something I’ve described because, really, it was very special.”

TRUE TEAMWORK

Although everyone on a multidisciplinary team can bring something to the discussion that makes the team work better, social workers and hospitalists collaborate well in painting a more comprehensive picture of the patient’s lifestyle, living habits, and needs.

“In many hospitals … there’s a pattern that develops [whereby at] some time in the morning the hospitalist and social worker will get together and talk,” says Dr. Flansbaum “The hospitalist speaks the language of the social worker and knows what to tell them and how to direct them rather than just saying, ‘the patient’s homeless or the patient needs help at home.’”

After working regularly with social workers and recognizing what they need to know, he says, “the hospitalist is more likely to say, ‘the patient has Medicaid,’ or ‘the patient has this insurance,’ [or] ‘the patient has a home-health [caregiver] four hours a day and needs six or eight hours a day,’ or ‘the patient’s going to need a subacute nursing facility.’ … I think our insights are different from voluntary physicians and our face-time with social workers is more efficient.”

Sylvia Krafcik, MSSA, LISW, with MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, says hospitalists are “great to work with because they’re very dedicated to the population they’re caring for, because this is their whole responsibility; they don’t have a private caseload.”

But in her view most hospitalists are focused on patients’ medical conditions and some of them are not as tuned in to all the other aspects of the patient, such as all the psychosocial dynamics.

“A lot of them are, but some aren’t,” Krafcik says. “Especially at MetroHealth, we’re a county hospital. So many of the patients that come here are poor. A lot of them are alcoholics or drug abusers. They’re homeless. They live on the streets. They don’t have a primary doctor. They’re usually not compliant with their medications.”

“Here at Metro we have a lot of patients who have extreme social circumstances that affect their medical issues so much,” says Sara Dunson, MSW, LSW, who also works as a social worker at Metro-Health. “I think the hospitalist has greater insight into the person’s environment and all the social structures that they have at home and that are going on in their life [than other physicians might].”

But there is always room for improvement.

“We had one patient who wasn’t able to read, and he never told anybody this,” says Dunson. “And as social workers, we have more of a way of finding that kind of stuff out from patients than the doctors might. And he kept coming in and coming in and was noncompliant with his medication. We eventually determined that this was why he was noncompliant and was causing all these medical issues. The doctors finally [understood] why this gentleman kept coming in with the same problems and he wasn’t taking care of himself. It wasn’t that he didn’t want to, it was just that he was having problems reading all the medications and all the discharge paperwork, and he was too ashamed to tell anybody. [Once the social workers questioned him and got this] out in the open, we were able to get him help with that.”

The doctors focused on what he was or wasn’t doing, but they hadn’t looked at why he wasn’t adherent, explains Dunson. If hospitalists do that more often, she thinks, they could save time and get better outcomes sooner.

COMMUNICATING WITH PATIENTS AND FAMILIES

“I think where hospitalists are coming from is a whole different mindset than a physician who has mainly an office practice,” said Lingg. “The office practice comes first [for them]. Some of our physicians have huge practices in town. And they’ll visit the hospital very early in the morning or in the evening. ... So if I need something in a case like that, if there was not a hospitalist involved, it would have been separate meetings for the family with the physician … and [with] me at another time.”

To hospitalists, a social worker can serve as an important adjunct in talking to the patient and family. “For example, if [social workers] are giving bad news, they warn the physician first,” says Dr. Rajan. “If they’re going to go in and tell the patient that they’re not going to qualify for any home services, they tell the physician as well so that [the hospitalist will not later be] meeting an angry patient.” In addition, she says, “for critically ill or long-term patients, social workers [can] help family members cope. Sometimes as physicians we don’t have the time or we don’t have the resources to do that.”

But this doesn’t let doctors off the hook in regard to addressing the whole person’s needs. Especially if someone has multiple medical problems, the social worker needs to know the availability and level of support for which the family can be counted.

“Social workers will ask questions such as: Are the families involved? or Is there any family?” says Krafcik. “Do they need to go in a nursing home or do they need 24-hour care at home? Is the family able to provide that? [E]very morning we meet to have team rounds. And the [team] go[es] over every patient on the floor, and then I will ask those questions if the doctor hasn’t given me that information.”

Social workers appreciate and would like hospitalists to do more listening to the patient and family for the aspects of the history and psychosocial status that the social worker will need to know.

TEACHING POINTS

In the course of their interactions, what do hospitalists and social workers teach each other that could lead to working a case more effectively and to the greater satisfaction of all involved?

Most of those we interviewed seem to think that the greatest service hospitalists provide is to teach the social worker the medical components that go along with what the social worker does every day.

“[Social workers] get a better understanding of [whether] someone comes in with heart failure or a fall or a stroke, just by repetition and also education; they get to understand after a while what’s needed for individual medical diagnoses,” says Dr. Flansbaum.

“When I know [better] what the medical condition is,” says Krafcik, “I have an idea of how much help [the patient] would need at home and their ability to function. And I would make sure that the patient gets physical therapy or occupational therapy referral or speech therapy.”

Again, perhaps the area where the social worker most teaches the hospitalist regards available resources to solve problems over and above the purely medical. “They know the social system and the needs of different forms and eligibility and what different patients are entitled to and what the system will provide,” says Dr. Flansbaum.

Dunson believes hospitalists are perceived as being more involved in a holistic way with the patient. “I always stress that it is so important to look at the whole person and not just the medical aspects,” she says. “It’s hard for the doctor sometimes to realize that this person might not be able to afford this medication and that’s why they’re noncompliant and all the other issues. So I think is important to open up to the other aspects of a person’s life and not just the medical aspects.”

CONCLUSION

Social workers’ knowledge of medical and nonmedical resources, both locally and nationally, offer hospitalists essential information that leads to designing more appropriate and effective post-discharge plans. Hospitalists can best team with social workers by consistently keeping in mind the patient’s overall circumstances and informing their colleagues of the medical information that can help social workers do their best work. TH

Writer Andrea Sattinger will write about the effect of poor communication skills in the November issue of The Hospitalist.

Editors’ note: “Alliances” is a new series written about the relationships that hospitalists have with members of the clinical care team—from the team members’ points of view. It’s our hope that each installment of “Alliances” will provide valuable, revealing feedback that hospitalists can use to continually improve their intrateam relationships and, ultimately, patient care.