User login

Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: 2020 American Society of Addiction Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management

Alcohol is the most common substance implicated in hospitalizations for substance use disorders,1 and as a result, hospitalists commonly diagnose and manage alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) in the inpatient medical setting. The 2020 guidelines of the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) provide updated recommendations for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of patients hospitalized with AWS, which we have condensed to emphasize key changes from the last update2 and clarify ongoing areas of uncertainty.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Diagnosis

Recommendation 1. All inpatients who have used alcohol recently or regularly should be risk-stratified for AWS, regardless of whether or not they have suggestive symptoms (recommendations I.3, I.4, I.5, II.10). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-(Piccinelli) Consumption (AUDIT-PC) identifies patients at risk for AWS, and the Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) identifies those at risk for severe or complicated AWS, which includes seizures and alcohol withdrawal delirium (formerly delirium tremens). The guideline emphasizes use of these tools rather than simply initiating Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol, revised (CIWA-Ar) monitoring on all such patients to diagnose AWS, as CIWA-Ar was developed for monitoring response to treatment, not diagnosis (recommendation I.6).

Treating Mild/Moderate or Uncomplicated AWS

Recommendation 2. Because of their proven track record of reducing the incidence of seizure and alcohol withdrawal delirium, benzodiazepines remain the recommended first-line therapy (recommendations V.13, V.16). Symptom-triggered administration of benzodiazepines (via CIWA-Ar) is recommended over fixed-dose administration because the former is associated with shorter length of stay and lower cumulative benzodiazepine administration3,4 (recommendation V.23). Patients with mild AWS who are at low risk for severe or complicated withdrawal should be monitored for up to 36 hours for the development of worsening symptoms (recommendation V.1). For patients with high CIWA-Ar scores or who are at increased risk for severe or complicated AWS, frequent administration of moderate to high doses of a long-acting benzodiazepine early in AWS treatment (a practice called frontloading) is recommended to quickly control symptoms and prevent clinical worsening. This approach has been shown to reduce the incidence of seizures and alcohol withdrawal delirium (recommendations V.14, V.19, V.24).

Carbamazepine or gabapentin may be used in mild or moderate AWS if benzodiazepines are contraindicated; however, neither agent is recommended as first-line therapy because a clear reduction in seizure and withdrawal delirium has not been established (recommendation V.16). Alpha-2 agonists (eg, clonidine, dexmedetomidine) may be used to treat persistent autonomic hyperactivity or anxiety when these are not adequately controlled by benzodiazepines alone (recommendation V.36).

Treating Severe or Complicated AWS

Recommendation 3. The guideline defines severe AWS as withdrawal with severe signs and symptoms, and complicated AWS as withdrawal accompanied by seizures or delirium (Appendix Table5). The development of complications warrants prompt treatment. Patients who experience seizure should receive a fast-acting benzodiazepine (eg, intravenous [IV] diazepam or lorazepam) (recommendation VI.4). Patients with withdrawal delirium should receive a benzodiazepine (preferably parenterally) dosed to achieve light sedation. Clinicians should be prepared for the possibility that large doses may be required and to monitor patients for oversedation and respiratory depression (recommendations VI.13, VI.17). Antipsychotics may be used as adjuncts when withdrawal delirium or other symptoms, such as hallucinosis, are not adequately controlled by benzodiazepines alone, but should not be used as monotherapy (recommendation VI.20). The guideline emphasizes that alpha-2 agonists should not be used to treat withdrawal delirium (recommendation VI.21), but they may be used as adjuncts for resistant alcohol withdrawal in the intensive care unit (ICU) (recommendations VI.27, VI.29). Phenobarbital is an acceptable alternative to benzodiazepines for severe withdrawal (recommendation V.17); however, the guideline recommends that clinicians should be experienced in its use.

Treating Wernicke Encephalopathy

Recommendation 4. Thiamine should be administered to prevent Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), with parenteral formulations recommended in patients with malnutrition, severe/complicated withdrawal, or requiring ICU-level care (recommendations V.7, V.8). In particular, all patients admitted to an ICU for AWS should receive thiamine, as diagnosis of WE is often difficult in this population. Although there is no consensus on the required dose of thiamine to treat WE, 100 mg IV or intramuscularly (IM) daily for 3 to 5 days is commonly administered (recommendation V.7). Because of a lack of evidence of harm, thiamine may be given before, after, or concurrently with glucose or dextrose (recommendation V.7). The guideline does not make a specific recommendation regarding how to risk-stratify patients for WE.

Treating Underlying Alcohol Use Disorder

Recommendation 5. Hospitalization for AWS is an important opportunity to engage patients in treatment for alcohol use disorder (AUD), including pharmacotherapy and connection with outpatient providers (recommendation V.12). The guideline emphasizes that treatment for AUD should be initiated concomitantly with AWS management whenever possible but does not make recommendations regarding specific pharmacotherapies.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was authored by a committee of emergency medicine physicians, psychiatrists, and internists using the Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense guidelines and the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method to combine the scientific literature with expert opinion. The result is a series of recommendations for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists that are not rated by strength; an assessment of the quality of the supporting evidence is available in an appendix. Four of the nine guideline committee members reported significant financial relationships with industry and other entities relevant to these guidelines.

Despite concern about oversedation from phenobarbital raised in small case series,6 observational studies comparing phenobarbital with benzodiazepines suggest phenobarbital has similar efficacy for treating AWS and that oversedation is rare.7-9 Large randomized controlled trials in this area are lacking; however, at least one small randomized controlled trial10 among patients with AWS presenting to emergency departments supports the safety and efficacy of phenobarbital when used in combination with benzodiazepines. Given the growing body of evidence supporting the safety of phenobarbital, we believe a stronger recommendation for use in patients presenting with alcohol withdrawal delirium or treatment-resistant alcohol withdrawal is warranted. The guidelines also suggest that only “experienced clinicians” use phenobarbital for AWS, which may suppress appropriate use. Nationally, phenobarbital use for AWS remains low.11Finally, although the guideline recommends initiation of treatment for AUD, specific recommendations for pharmacotherapy are not provided. Three medications currently have approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of AUD: acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram. Large randomized controlled trials support the safety and efficacy of acamprosate and naltrexone, with or without counselling, in the treatment of AUD,12 and disulfiram may be appropriate for selected highly motivated patients. We believe more specific recommendations to assist in choosing among these options would be useful.

AREAS IN NEED OF FUTURE STUDY

More data are needed on the safety and efficacy of phenobarbital in patients with AWS, as well as comparative effectiveness against benzodiazepines. Recruitment is ongoing for a single clinical trial comparing the effect of phenobarbital and lorazepam on length of stay among patients in the ICU with AWS (NCT04156464); to date, no randomized trials of phenobarbital have been conducted in medical inpatients with AWS. In addition, gaps in the literature exist regarding benzodiazepine selection, and head-to-head comparisons of symptom-triggered usage of different benzodiazepines are lacking.

1. Heslin KC, Elixhauser A, Steiner CA. Hospitalizations involving mental and substance use disorders among adults, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #191. June 2015. Accessed November 17, 2021. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb191-Hospitalization-Mental-Substance-Use-Disorders-2012.pdf

2. Mayo-Smith MF, Beecher LH, Fischer TL, et al. Management of alcohol withdrawal delirium. An evidence-based practice guideline. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(13):1405-1412. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.13.1405

3. Saitz R, Mayo-Smith MF, Roberts MS, Redmond HA, Bernard DR, Calkins DR. Individualized treatment for alcohol withdrawal. A randomized double-blind controlled trial. JAMA. 1994;272(7):519-523.

4. Daeppen J-B, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.10.1117

5. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. J Addict Med. 2020;14(3S suppl):1-72. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000668

6. Oks M, Cleven KL, Healy L, et al. The safety and utility of phenobarbital use for the treatment of severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome in the medical intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35(9):844-850. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066618783947

7. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00737.x

8. Ibarra Jr F. Single dose phenobarbital in addition to symptom-triggered lorazepam in alcohol withdrawal. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(2):178-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.01.053

9. Nisavic M, Nejad SH, Isenberg BM, et al. Use of phenobarbital in alcohol withdrawal management–a retrospective comparison study of phenobarbital and benzodiazepines for acute alcohol withdrawal management in general medical patients. Psychosomatics. 2019;60(5):458-467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2019.02.002

10. Rosenson J, Clements C, Simon B, et al. Phenobarbital for acute alcohol withdrawal: a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(3):592-598.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.07.056

11. Gupta N, Emerman CL. Trends in the management of inpatients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Addict Disord Their Treat. 2021;20(1):29-32. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADT.0000000000000203

12. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003-2017. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.17.2003

Alcohol is the most common substance implicated in hospitalizations for substance use disorders,1 and as a result, hospitalists commonly diagnose and manage alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) in the inpatient medical setting. The 2020 guidelines of the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) provide updated recommendations for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of patients hospitalized with AWS, which we have condensed to emphasize key changes from the last update2 and clarify ongoing areas of uncertainty.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Diagnosis

Recommendation 1. All inpatients who have used alcohol recently or regularly should be risk-stratified for AWS, regardless of whether or not they have suggestive symptoms (recommendations I.3, I.4, I.5, II.10). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-(Piccinelli) Consumption (AUDIT-PC) identifies patients at risk for AWS, and the Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) identifies those at risk for severe or complicated AWS, which includes seizures and alcohol withdrawal delirium (formerly delirium tremens). The guideline emphasizes use of these tools rather than simply initiating Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol, revised (CIWA-Ar) monitoring on all such patients to diagnose AWS, as CIWA-Ar was developed for monitoring response to treatment, not diagnosis (recommendation I.6).

Treating Mild/Moderate or Uncomplicated AWS

Recommendation 2. Because of their proven track record of reducing the incidence of seizure and alcohol withdrawal delirium, benzodiazepines remain the recommended first-line therapy (recommendations V.13, V.16). Symptom-triggered administration of benzodiazepines (via CIWA-Ar) is recommended over fixed-dose administration because the former is associated with shorter length of stay and lower cumulative benzodiazepine administration3,4 (recommendation V.23). Patients with mild AWS who are at low risk for severe or complicated withdrawal should be monitored for up to 36 hours for the development of worsening symptoms (recommendation V.1). For patients with high CIWA-Ar scores or who are at increased risk for severe or complicated AWS, frequent administration of moderate to high doses of a long-acting benzodiazepine early in AWS treatment (a practice called frontloading) is recommended to quickly control symptoms and prevent clinical worsening. This approach has been shown to reduce the incidence of seizures and alcohol withdrawal delirium (recommendations V.14, V.19, V.24).

Carbamazepine or gabapentin may be used in mild or moderate AWS if benzodiazepines are contraindicated; however, neither agent is recommended as first-line therapy because a clear reduction in seizure and withdrawal delirium has not been established (recommendation V.16). Alpha-2 agonists (eg, clonidine, dexmedetomidine) may be used to treat persistent autonomic hyperactivity or anxiety when these are not adequately controlled by benzodiazepines alone (recommendation V.36).

Treating Severe or Complicated AWS

Recommendation 3. The guideline defines severe AWS as withdrawal with severe signs and symptoms, and complicated AWS as withdrawal accompanied by seizures or delirium (Appendix Table5). The development of complications warrants prompt treatment. Patients who experience seizure should receive a fast-acting benzodiazepine (eg, intravenous [IV] diazepam or lorazepam) (recommendation VI.4). Patients with withdrawal delirium should receive a benzodiazepine (preferably parenterally) dosed to achieve light sedation. Clinicians should be prepared for the possibility that large doses may be required and to monitor patients for oversedation and respiratory depression (recommendations VI.13, VI.17). Antipsychotics may be used as adjuncts when withdrawal delirium or other symptoms, such as hallucinosis, are not adequately controlled by benzodiazepines alone, but should not be used as monotherapy (recommendation VI.20). The guideline emphasizes that alpha-2 agonists should not be used to treat withdrawal delirium (recommendation VI.21), but they may be used as adjuncts for resistant alcohol withdrawal in the intensive care unit (ICU) (recommendations VI.27, VI.29). Phenobarbital is an acceptable alternative to benzodiazepines for severe withdrawal (recommendation V.17); however, the guideline recommends that clinicians should be experienced in its use.

Treating Wernicke Encephalopathy

Recommendation 4. Thiamine should be administered to prevent Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), with parenteral formulations recommended in patients with malnutrition, severe/complicated withdrawal, or requiring ICU-level care (recommendations V.7, V.8). In particular, all patients admitted to an ICU for AWS should receive thiamine, as diagnosis of WE is often difficult in this population. Although there is no consensus on the required dose of thiamine to treat WE, 100 mg IV or intramuscularly (IM) daily for 3 to 5 days is commonly administered (recommendation V.7). Because of a lack of evidence of harm, thiamine may be given before, after, or concurrently with glucose or dextrose (recommendation V.7). The guideline does not make a specific recommendation regarding how to risk-stratify patients for WE.

Treating Underlying Alcohol Use Disorder

Recommendation 5. Hospitalization for AWS is an important opportunity to engage patients in treatment for alcohol use disorder (AUD), including pharmacotherapy and connection with outpatient providers (recommendation V.12). The guideline emphasizes that treatment for AUD should be initiated concomitantly with AWS management whenever possible but does not make recommendations regarding specific pharmacotherapies.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was authored by a committee of emergency medicine physicians, psychiatrists, and internists using the Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense guidelines and the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method to combine the scientific literature with expert opinion. The result is a series of recommendations for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists that are not rated by strength; an assessment of the quality of the supporting evidence is available in an appendix. Four of the nine guideline committee members reported significant financial relationships with industry and other entities relevant to these guidelines.

Despite concern about oversedation from phenobarbital raised in small case series,6 observational studies comparing phenobarbital with benzodiazepines suggest phenobarbital has similar efficacy for treating AWS and that oversedation is rare.7-9 Large randomized controlled trials in this area are lacking; however, at least one small randomized controlled trial10 among patients with AWS presenting to emergency departments supports the safety and efficacy of phenobarbital when used in combination with benzodiazepines. Given the growing body of evidence supporting the safety of phenobarbital, we believe a stronger recommendation for use in patients presenting with alcohol withdrawal delirium or treatment-resistant alcohol withdrawal is warranted. The guidelines also suggest that only “experienced clinicians” use phenobarbital for AWS, which may suppress appropriate use. Nationally, phenobarbital use for AWS remains low.11Finally, although the guideline recommends initiation of treatment for AUD, specific recommendations for pharmacotherapy are not provided. Three medications currently have approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of AUD: acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram. Large randomized controlled trials support the safety and efficacy of acamprosate and naltrexone, with or without counselling, in the treatment of AUD,12 and disulfiram may be appropriate for selected highly motivated patients. We believe more specific recommendations to assist in choosing among these options would be useful.

AREAS IN NEED OF FUTURE STUDY

More data are needed on the safety and efficacy of phenobarbital in patients with AWS, as well as comparative effectiveness against benzodiazepines. Recruitment is ongoing for a single clinical trial comparing the effect of phenobarbital and lorazepam on length of stay among patients in the ICU with AWS (NCT04156464); to date, no randomized trials of phenobarbital have been conducted in medical inpatients with AWS. In addition, gaps in the literature exist regarding benzodiazepine selection, and head-to-head comparisons of symptom-triggered usage of different benzodiazepines are lacking.

Alcohol is the most common substance implicated in hospitalizations for substance use disorders,1 and as a result, hospitalists commonly diagnose and manage alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) in the inpatient medical setting. The 2020 guidelines of the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) provide updated recommendations for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of patients hospitalized with AWS, which we have condensed to emphasize key changes from the last update2 and clarify ongoing areas of uncertainty.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Diagnosis

Recommendation 1. All inpatients who have used alcohol recently or regularly should be risk-stratified for AWS, regardless of whether or not they have suggestive symptoms (recommendations I.3, I.4, I.5, II.10). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-(Piccinelli) Consumption (AUDIT-PC) identifies patients at risk for AWS, and the Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) identifies those at risk for severe or complicated AWS, which includes seizures and alcohol withdrawal delirium (formerly delirium tremens). The guideline emphasizes use of these tools rather than simply initiating Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol, revised (CIWA-Ar) monitoring on all such patients to diagnose AWS, as CIWA-Ar was developed for monitoring response to treatment, not diagnosis (recommendation I.6).

Treating Mild/Moderate or Uncomplicated AWS

Recommendation 2. Because of their proven track record of reducing the incidence of seizure and alcohol withdrawal delirium, benzodiazepines remain the recommended first-line therapy (recommendations V.13, V.16). Symptom-triggered administration of benzodiazepines (via CIWA-Ar) is recommended over fixed-dose administration because the former is associated with shorter length of stay and lower cumulative benzodiazepine administration3,4 (recommendation V.23). Patients with mild AWS who are at low risk for severe or complicated withdrawal should be monitored for up to 36 hours for the development of worsening symptoms (recommendation V.1). For patients with high CIWA-Ar scores or who are at increased risk for severe or complicated AWS, frequent administration of moderate to high doses of a long-acting benzodiazepine early in AWS treatment (a practice called frontloading) is recommended to quickly control symptoms and prevent clinical worsening. This approach has been shown to reduce the incidence of seizures and alcohol withdrawal delirium (recommendations V.14, V.19, V.24).

Carbamazepine or gabapentin may be used in mild or moderate AWS if benzodiazepines are contraindicated; however, neither agent is recommended as first-line therapy because a clear reduction in seizure and withdrawal delirium has not been established (recommendation V.16). Alpha-2 agonists (eg, clonidine, dexmedetomidine) may be used to treat persistent autonomic hyperactivity or anxiety when these are not adequately controlled by benzodiazepines alone (recommendation V.36).

Treating Severe or Complicated AWS

Recommendation 3. The guideline defines severe AWS as withdrawal with severe signs and symptoms, and complicated AWS as withdrawal accompanied by seizures or delirium (Appendix Table5). The development of complications warrants prompt treatment. Patients who experience seizure should receive a fast-acting benzodiazepine (eg, intravenous [IV] diazepam or lorazepam) (recommendation VI.4). Patients with withdrawal delirium should receive a benzodiazepine (preferably parenterally) dosed to achieve light sedation. Clinicians should be prepared for the possibility that large doses may be required and to monitor patients for oversedation and respiratory depression (recommendations VI.13, VI.17). Antipsychotics may be used as adjuncts when withdrawal delirium or other symptoms, such as hallucinosis, are not adequately controlled by benzodiazepines alone, but should not be used as monotherapy (recommendation VI.20). The guideline emphasizes that alpha-2 agonists should not be used to treat withdrawal delirium (recommendation VI.21), but they may be used as adjuncts for resistant alcohol withdrawal in the intensive care unit (ICU) (recommendations VI.27, VI.29). Phenobarbital is an acceptable alternative to benzodiazepines for severe withdrawal (recommendation V.17); however, the guideline recommends that clinicians should be experienced in its use.

Treating Wernicke Encephalopathy

Recommendation 4. Thiamine should be administered to prevent Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), with parenteral formulations recommended in patients with malnutrition, severe/complicated withdrawal, or requiring ICU-level care (recommendations V.7, V.8). In particular, all patients admitted to an ICU for AWS should receive thiamine, as diagnosis of WE is often difficult in this population. Although there is no consensus on the required dose of thiamine to treat WE, 100 mg IV or intramuscularly (IM) daily for 3 to 5 days is commonly administered (recommendation V.7). Because of a lack of evidence of harm, thiamine may be given before, after, or concurrently with glucose or dextrose (recommendation V.7). The guideline does not make a specific recommendation regarding how to risk-stratify patients for WE.

Treating Underlying Alcohol Use Disorder

Recommendation 5. Hospitalization for AWS is an important opportunity to engage patients in treatment for alcohol use disorder (AUD), including pharmacotherapy and connection with outpatient providers (recommendation V.12). The guideline emphasizes that treatment for AUD should be initiated concomitantly with AWS management whenever possible but does not make recommendations regarding specific pharmacotherapies.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was authored by a committee of emergency medicine physicians, psychiatrists, and internists using the Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense guidelines and the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method to combine the scientific literature with expert opinion. The result is a series of recommendations for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists that are not rated by strength; an assessment of the quality of the supporting evidence is available in an appendix. Four of the nine guideline committee members reported significant financial relationships with industry and other entities relevant to these guidelines.

Despite concern about oversedation from phenobarbital raised in small case series,6 observational studies comparing phenobarbital with benzodiazepines suggest phenobarbital has similar efficacy for treating AWS and that oversedation is rare.7-9 Large randomized controlled trials in this area are lacking; however, at least one small randomized controlled trial10 among patients with AWS presenting to emergency departments supports the safety and efficacy of phenobarbital when used in combination with benzodiazepines. Given the growing body of evidence supporting the safety of phenobarbital, we believe a stronger recommendation for use in patients presenting with alcohol withdrawal delirium or treatment-resistant alcohol withdrawal is warranted. The guidelines also suggest that only “experienced clinicians” use phenobarbital for AWS, which may suppress appropriate use. Nationally, phenobarbital use for AWS remains low.11Finally, although the guideline recommends initiation of treatment for AUD, specific recommendations for pharmacotherapy are not provided. Three medications currently have approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of AUD: acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram. Large randomized controlled trials support the safety and efficacy of acamprosate and naltrexone, with or without counselling, in the treatment of AUD,12 and disulfiram may be appropriate for selected highly motivated patients. We believe more specific recommendations to assist in choosing among these options would be useful.

AREAS IN NEED OF FUTURE STUDY

More data are needed on the safety and efficacy of phenobarbital in patients with AWS, as well as comparative effectiveness against benzodiazepines. Recruitment is ongoing for a single clinical trial comparing the effect of phenobarbital and lorazepam on length of stay among patients in the ICU with AWS (NCT04156464); to date, no randomized trials of phenobarbital have been conducted in medical inpatients with AWS. In addition, gaps in the literature exist regarding benzodiazepine selection, and head-to-head comparisons of symptom-triggered usage of different benzodiazepines are lacking.

1. Heslin KC, Elixhauser A, Steiner CA. Hospitalizations involving mental and substance use disorders among adults, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #191. June 2015. Accessed November 17, 2021. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb191-Hospitalization-Mental-Substance-Use-Disorders-2012.pdf

2. Mayo-Smith MF, Beecher LH, Fischer TL, et al. Management of alcohol withdrawal delirium. An evidence-based practice guideline. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(13):1405-1412. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.13.1405

3. Saitz R, Mayo-Smith MF, Roberts MS, Redmond HA, Bernard DR, Calkins DR. Individualized treatment for alcohol withdrawal. A randomized double-blind controlled trial. JAMA. 1994;272(7):519-523.

4. Daeppen J-B, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.10.1117

5. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. J Addict Med. 2020;14(3S suppl):1-72. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000668

6. Oks M, Cleven KL, Healy L, et al. The safety and utility of phenobarbital use for the treatment of severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome in the medical intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35(9):844-850. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066618783947

7. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00737.x

8. Ibarra Jr F. Single dose phenobarbital in addition to symptom-triggered lorazepam in alcohol withdrawal. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(2):178-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.01.053

9. Nisavic M, Nejad SH, Isenberg BM, et al. Use of phenobarbital in alcohol withdrawal management–a retrospective comparison study of phenobarbital and benzodiazepines for acute alcohol withdrawal management in general medical patients. Psychosomatics. 2019;60(5):458-467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2019.02.002

10. Rosenson J, Clements C, Simon B, et al. Phenobarbital for acute alcohol withdrawal: a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(3):592-598.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.07.056

11. Gupta N, Emerman CL. Trends in the management of inpatients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Addict Disord Their Treat. 2021;20(1):29-32. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADT.0000000000000203

12. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003-2017. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.17.2003

1. Heslin KC, Elixhauser A, Steiner CA. Hospitalizations involving mental and substance use disorders among adults, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #191. June 2015. Accessed November 17, 2021. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb191-Hospitalization-Mental-Substance-Use-Disorders-2012.pdf

2. Mayo-Smith MF, Beecher LH, Fischer TL, et al. Management of alcohol withdrawal delirium. An evidence-based practice guideline. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(13):1405-1412. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.13.1405

3. Saitz R, Mayo-Smith MF, Roberts MS, Redmond HA, Bernard DR, Calkins DR. Individualized treatment for alcohol withdrawal. A randomized double-blind controlled trial. JAMA. 1994;272(7):519-523.

4. Daeppen J-B, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.10.1117

5. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. J Addict Med. 2020;14(3S suppl):1-72. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000668

6. Oks M, Cleven KL, Healy L, et al. The safety and utility of phenobarbital use for the treatment of severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome in the medical intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35(9):844-850. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066618783947

7. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00737.x

8. Ibarra Jr F. Single dose phenobarbital in addition to symptom-triggered lorazepam in alcohol withdrawal. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(2):178-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.01.053

9. Nisavic M, Nejad SH, Isenberg BM, et al. Use of phenobarbital in alcohol withdrawal management–a retrospective comparison study of phenobarbital and benzodiazepines for acute alcohol withdrawal management in general medical patients. Psychosomatics. 2019;60(5):458-467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2019.02.002

10. Rosenson J, Clements C, Simon B, et al. Phenobarbital for acute alcohol withdrawal: a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(3):592-598.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.07.056

11. Gupta N, Emerman CL. Trends in the management of inpatients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Addict Disord Their Treat. 2021;20(1):29-32. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADT.0000000000000203

12. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003-2017. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.17.2003

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Veteran With a Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

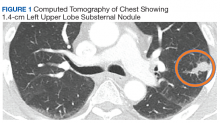

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.