User login

A Veteran With a Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

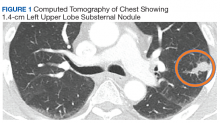

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.

A Veteran With Fibromyalgia Presenting With Dyspnea

Case Presentation. A 64-year-old US Army veteran with a history of colorectal cancer, melanoma, and fibrinolytic presented with dyspnea to VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS). Seven years prior to the current presentation, at the time of her diagnosis of colorectal cancer, the patient was found to be HIV negative but to have a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) test. She was treated with isoniazid (INH) therapy for 9 months. Sputum cultures collected prior to initiation of therapy grew Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) in 1 of 3 samples, with these results reported several months after initiation of therapy. She was a never smoker with no known travel or exposure. At the time of the current presentation, her medications included bupropion, levothyroxine, capsaicin, cyclobenzaprine, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen.

►Lakshmana Swamy, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Boston Medical Center. Dr. Monach, this patient is on a variety of pain medications and has a diagnosis of fibromyalgia. This diagnosis often frustrates doctors and patients alike. Can you tell us about fibromyalgia from the rheumatologist’s perspective and what you think of her current treatment regimen?

►Paul A. Monach, MD, PhD, Chief, Section of Rheumatology, VABHS and Associate Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Fibromyalgia is a syndrome of chronic widespread pain without known pathology in the musculoskeletal system. It is thought to be caused by chronic dysfunction of pain-processing pathways in the central nervous system (CNS). It is often accompanied by other somatic symptoms such as chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain. It is a common condition, affecting up to 5% of otherwise healthy women. It is particularly common in persons with chronic nonrestorative sleep or posttraumatic stress disorder from a wide range of causes. However, it also is more common in persons with autoimmune inflammatory diseases, such as lupus, Sjögren syndrome, or rheumatoid arthritis. Concern for one of these diseases is the main reason to consider referring a patient for evaluation by a rheumatologist. Often rheumatologists participate in the management of fibromyalgia. A patient should be given appropriate expectations by the referring physician.

Effectiveness of treatment varies widely among patients. Nonpharmacologic approaches such as aerobic exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, and tai chi have support from clinical trials, and yoga and aquatherapy also are widely used.1,2 The classes of drugs used are the same as for neuropathic pain: tricyclics, including cyclobenzaprine; serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs); and gabapentinoids. In contrast, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids are ineffective unless there is a superimposed mechanical or inflammatory cause in the periphery. The key point is that continuation of any treatment should be based entirely on the patient’s own assessment of benefit.

►Dr. Swamy. Seven years later, the patient returned to her primary care provider, reporting increased dyspnea on exertion as well as significant fatigue. She was referred to the pulmonary department and had repeat computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, which indicated persistent right middle lobe (RML) bronchiectasis. She then underwent bronchoscopy with a subsequent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture growing MAC. Dr. Fine, please interpret the baseline and follow-up CT scans and help us understand the significance of the MAC on sputum and BAL cultures.

►Alan Fine, MD, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS and Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Prior to this presentation, the patient had a pleural-based area of fibrosis with possible associated RML bronchiectasis. This appears to be a postinflammatory process without classic features of malignant or metastatic disease. She then had a sputum, which grew MAC in only 1 of 3 samples and in liquid media only. Importantly, the sputum was not smear positive. All of this suggests a low organism burden. One possibility is that this could reflect colonization with MAC; it is not uncommon for patients with underlying chronic changes in their lung to grow MAC, and it is often difficult to tell whether it is indicative of active disease. Structural lung disease, such as bronchiectasis, predisposes a patient to MAC, but chronic MAC also may cause bronchiectasis. This chicken-and-egg scenario comes up frequently. She may have a MAC infection, but as she is HIV negative and asymptomatic, there is no urgent indication to treat, especially as the burden of therapy is not insignificant.

►Dr. Swamy. Do we need to worry about Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)?

►Dr. Fine. Although she was previously PPD positive, she had already completed 1 year of isoniazid (INH) therapy, making active MTB less likely. From an infection control standpoint, it is important to distinguish MAC from MTB. The former is not contagious, and there is no need for airborne isolation.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, where does MAC come from? Does it commonly cause disease?

►Dr. Fine. In the environment, MAC is nearly ubiquitous , especially in water and soil. In one study, 20% of showerheads were positive for MAC; when patients are infected, we may suggest changing/bleaching the showerhead, but there are no definitive recommendations.3 Because MAC is so common in the environment, it is unlikely that measures to target MAC colonization will be clinically meaningful. On the other hand, the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections is increasing across the US, and it may be a common and frequently underdiagnosed cause of chronic cough, especially in postmenopausal women.

►Dr. Swamy. Four years prior to the current presentation, the patient developed a cough after an upper respiratory tract infection that persisted for more than 2 weeks. Given her history, she underwent a repeat chest CT, which noted a slight increase in nodularity and ground-glass opacity restricted to the RML. She also reported dyspnea on exertion and was referred to the pulmonary medicine department. By the time she arrived, her dyspnea had largely resolved, but she reported persistent fatigue without other systemic symptoms, such as fevers or chills. Dr. Fine, does MAC explain this patient’s dyspnea?

►Dr. Fine. As her pulmonary symptoms resolved in a short period of time with only azithromycin, it is very unlikely that her symptoms were related to her prior disease. The MAC infection is not likely to cause dyspnea on exertion and fatigue and should be worked up more broadly before attributing it to MAC. In view of this, it would not be unreasonable to follow her clinically and see her again in 6 to 8 weeks. In this context, we also should consider the untoward impact of repeated radiation exposure derived from multiple CT scans. When a patient has an abnormality on CT scan, it often leads to further scans even if the symptoms do not match the previous findings, as in this case.

►Dr. Swamy. Given her ongoing fatigue and systemic symptoms (morning stiffness of the shoulders, legs, and thighs, and leg cramps), she was referred to the rheumatology department where the physical examination revealed muscle tenderness in her proximal arms and legs with normal strength, tender points at the elbows and medial side of the bilateral knees, significant tenderness of lower legs, and no synovitis.

Dr. Monach, can you walk us through your approach to this patient? Are we seeing manifestations of fibromyalgia? What diagnoses concerns you and how would you proceed?

►Dr. Monach. The history and exam are most helpful in raising or reducing suspicion for an underlying inflammatory disease. Areas of tenderness described in her case are typical of fibromyalgia, although it can be difficult to interpret symptoms in the hip girdle and shoulder girdle because objective findings are often absent on exam in patients with inflammatory arthritis or bursitis. Similarly, tenderness at sites of tendon insertion (enthuses) without objective abnormalities is common in different forms of spondyloarthritis, so tenderness at the elbow, knee, lateral hip, and low back can be difficult to interpret. What this patient is lacking is prominent subjective or objective findings in the joints most commonly affected in rheumatoid arthritis and lupus: wrists, hands, ankles, and feet.

►Dr. Swamy. Initial laboratory data include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 79 with a normal C-reactive protein. A tentative diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatic is made with consideration of a trial treatment of prednisone.

Dr. Monach, this patient has an indolent infection and is about to be given glucocorticoids. Could you describe the situations in which you feel that glucocorticoids cause a relative immunosuppression?

►Dr. Monach. Glucocorticoids are considered safe in a patient whose infection is not intrinsically dangerous or who has started appropriate antibiotics for that infection. Although all toxicities of glucocorticoids are dose dependent, the long-standing assertion that doses below 10 mg to 15 mg do not increase risk of infection is contradicted by data published in the past 10 to 15 years, with the caveat that these patients were on long-term treatment.

►Dr. Swamy. The patient was started on prednisone 15 mg per day for 15 days. She returned to the clinic after 1 week of prednisone troutment and noted “significant improvement in fatigue, morning stiffness of shoulders, thighs, leg, back is better, leg cramps resolved, shooting pain in many joints resolved.” Further laboratory results were notable for a negative rheumatoid factor, negative antinuclear antibody, and a cyclic citrullinated peptide of 60. A presumptive diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was made and plaquenil 200 mg twice daily was started.

Dr. Monach, can you explain why RA comes up now on serology but was not considered initially? Why does this presentation fit RA, and was her response to treatment typical? How does this fit in with her previous diagnosis of fibromyalgia? Was that just an atypical, indolent presentation of RA?

►Dr. Monach. Though her presentation is atypical for RA, in elderly patients, RA can present with symptoms resembling polymyalgia rheumatica. The question is whether she had RA all along (in which case “elderly onset” would not apply) or had fibromyalgia and developed RA more recently. The response to empiric glucocorticoid therapy is helpful, since fibromyalgia should not improve with prednisone even in a patient with RA unless treatment of RA would allow better sleep and ability to exercise. Rheumatoid arthritis typically responds very well to prednisone in the 5-mg to 15-mg range.

►Dr. Swamy. Given the new diagnosis of an inflammatory arthritis requiring immunosuppression, bronchoscopy with BAL is performed to evaluate for the presence of MAC. These cultures were positive for MAC.

Dr. Fine, does the positive BAL culture indicate an active MAC infection?

►Dr. Fine. Yes, based on these updated data, the patient has an active MAC infection. Active infection is defined as symptoms or imaging consistent with the diagnosis, supporting microbiology data (either 2 sputum or 1 BAL sample growing MAC) and the exclusion of other causes. Previously, this patient grew MAC in just one expectorated sputum; this did not meet the microbiologic criteria. Now sputum has grown in the BAL sample; along with the CT imaging, this is enough to diagnosis active MAC infection.

Treatment for MAC must consider the details of each case. First, this is not an emergency; treatment decisions should be made with the rheumatologist to consider the planned immunosuppression. For example, we must consider potential drug interactions. A specific point should be made of the use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibition, which data indicate can reactivate TB and may inhibit mechanisms that restrain mycobacterial disease. Serious cases of MAC infection have been reported in the literature in the setting of TNF-α inhibition.5,6 Despite these concerns, there is not a contraindication to using these therapies from the perspective of the active MAC disease. All of these decisions will impact the need to commit the patient to MAC therapy.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, what do you consider prior to initiating MAC therapy?

► Dr. Fine. The decision to pursue MAC therapy should not be taken lightly. Therapy often entails prolonged multidrug regimens, usually spanning more than a year, with frequent adverse effects. Outside of very specific cases, such as TNF-β inhibition, MAC is rarely a life-threatening disease, so the benefit may be limited. Treatment for MAC is certainly unlikely to be fruitful without a diligent and motivated patient able to handle the high and prolonged pill burden. Of note, it is also important to keep this patient up-to-date with influenza and pneumonia vaccination given her structural lung disease.

►Dr. Swamy. The decision is made to treat MAC with azithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol. The disease is noted to be nonfibrocavitary. The patient underwent monthly liver function test monitoring and visual acuity testing, which were unremarkable. Dr. Fine, can you describe the phenotypes of nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) disease?

►Dr. Fine. There are 3 main phenotypes of NTM.3 First, we see the elderly man with preexisting lung disease—usually chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—with fibrocavitary and/or reticulonodular appearance. Second, we see the slim, elderly woman often without any preexisting lung disease presenting with focal bronchiectasis and nodular lesions in right middle lobe and lingula—the Lady Windermere syndrome. This eponym is derived from Oscar Wilde’s play “Lady Windermere’s Fan, a Play About a Good Woman,” and was first associated with this disease in 1992.7 At the time, it was thought that the voluntary suppression of cough led to poorly draining lung regions, vulnerable to engraftment by atypical mycobacteria. Infection with atypical mycobacteria are associated with this population; however, it is no longer thought to be due to the voluntary suppression of cough.7,8 Third, we do occasionally see atypical presentations, such as focal masses and solitary nodules.

►Dr. Swamy. At 1-year follow-up she successfully completed MAC therapy and noted ongoing control of rheumatoid symptoms.

1. Bernardy K, Klose P, Welsch P, Häuser W. Efficacy, acceptability and safety of cognitive behavioural therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome—a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(2):242-260.

2. Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011279.

3. Aksamit TR, Philley JV, Griffith DE. Nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) lung disease: the top ten essentials. Respir Med. 2014;108(3):417-425.

4. Aucott JN. Glucocorticoids and infection. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1994;23(3):655-670.

5. Curtis JR, Yang S, Patkar NM, et al. Risk of hospitalized bacterial infections associated with biologic treatment among US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(7):990-997.

6. Lane MA, McDonald JR, Zeringue AL, et al. TNF-α antagonist use and risk of hospitalization for infection in a national cohort of veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90(2):139-145.

7. Reich JM, Johnson RE. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease presenting as an isolated lingular or middle lobe pattern. The Lady Windermere syndrome. Chest. 1992;101(6):1605-1609.

8. Kasthoori JJ, Liam CK, Wastie ML. Lady Windermere syndrome: an inappropriate eponym for an increasingly important condition. Singapore Med J. 2008;49(2):e47-e49.

Case Presentation. A 64-year-old US Army veteran with a history of colorectal cancer, melanoma, and fibrinolytic presented with dyspnea to VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS). Seven years prior to the current presentation, at the time of her diagnosis of colorectal cancer, the patient was found to be HIV negative but to have a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) test. She was treated with isoniazid (INH) therapy for 9 months. Sputum cultures collected prior to initiation of therapy grew Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) in 1 of 3 samples, with these results reported several months after initiation of therapy. She was a never smoker with no known travel or exposure. At the time of the current presentation, her medications included bupropion, levothyroxine, capsaicin, cyclobenzaprine, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen.

►Lakshmana Swamy, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Boston Medical Center. Dr. Monach, this patient is on a variety of pain medications and has a diagnosis of fibromyalgia. This diagnosis often frustrates doctors and patients alike. Can you tell us about fibromyalgia from the rheumatologist’s perspective and what you think of her current treatment regimen?

►Paul A. Monach, MD, PhD, Chief, Section of Rheumatology, VABHS and Associate Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Fibromyalgia is a syndrome of chronic widespread pain without known pathology in the musculoskeletal system. It is thought to be caused by chronic dysfunction of pain-processing pathways in the central nervous system (CNS). It is often accompanied by other somatic symptoms such as chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain. It is a common condition, affecting up to 5% of otherwise healthy women. It is particularly common in persons with chronic nonrestorative sleep or posttraumatic stress disorder from a wide range of causes. However, it also is more common in persons with autoimmune inflammatory diseases, such as lupus, Sjögren syndrome, or rheumatoid arthritis. Concern for one of these diseases is the main reason to consider referring a patient for evaluation by a rheumatologist. Often rheumatologists participate in the management of fibromyalgia. A patient should be given appropriate expectations by the referring physician.

Effectiveness of treatment varies widely among patients. Nonpharmacologic approaches such as aerobic exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, and tai chi have support from clinical trials, and yoga and aquatherapy also are widely used.1,2 The classes of drugs used are the same as for neuropathic pain: tricyclics, including cyclobenzaprine; serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs); and gabapentinoids. In contrast, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids are ineffective unless there is a superimposed mechanical or inflammatory cause in the periphery. The key point is that continuation of any treatment should be based entirely on the patient’s own assessment of benefit.

►Dr. Swamy. Seven years later, the patient returned to her primary care provider, reporting increased dyspnea on exertion as well as significant fatigue. She was referred to the pulmonary department and had repeat computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, which indicated persistent right middle lobe (RML) bronchiectasis. She then underwent bronchoscopy with a subsequent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture growing MAC. Dr. Fine, please interpret the baseline and follow-up CT scans and help us understand the significance of the MAC on sputum and BAL cultures.

►Alan Fine, MD, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS and Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Prior to this presentation, the patient had a pleural-based area of fibrosis with possible associated RML bronchiectasis. This appears to be a postinflammatory process without classic features of malignant or metastatic disease. She then had a sputum, which grew MAC in only 1 of 3 samples and in liquid media only. Importantly, the sputum was not smear positive. All of this suggests a low organism burden. One possibility is that this could reflect colonization with MAC; it is not uncommon for patients with underlying chronic changes in their lung to grow MAC, and it is often difficult to tell whether it is indicative of active disease. Structural lung disease, such as bronchiectasis, predisposes a patient to MAC, but chronic MAC also may cause bronchiectasis. This chicken-and-egg scenario comes up frequently. She may have a MAC infection, but as she is HIV negative and asymptomatic, there is no urgent indication to treat, especially as the burden of therapy is not insignificant.

►Dr. Swamy. Do we need to worry about Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)?

►Dr. Fine. Although she was previously PPD positive, she had already completed 1 year of isoniazid (INH) therapy, making active MTB less likely. From an infection control standpoint, it is important to distinguish MAC from MTB. The former is not contagious, and there is no need for airborne isolation.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, where does MAC come from? Does it commonly cause disease?

►Dr. Fine. In the environment, MAC is nearly ubiquitous , especially in water and soil. In one study, 20% of showerheads were positive for MAC; when patients are infected, we may suggest changing/bleaching the showerhead, but there are no definitive recommendations.3 Because MAC is so common in the environment, it is unlikely that measures to target MAC colonization will be clinically meaningful. On the other hand, the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections is increasing across the US, and it may be a common and frequently underdiagnosed cause of chronic cough, especially in postmenopausal women.

►Dr. Swamy. Four years prior to the current presentation, the patient developed a cough after an upper respiratory tract infection that persisted for more than 2 weeks. Given her history, she underwent a repeat chest CT, which noted a slight increase in nodularity and ground-glass opacity restricted to the RML. She also reported dyspnea on exertion and was referred to the pulmonary medicine department. By the time she arrived, her dyspnea had largely resolved, but she reported persistent fatigue without other systemic symptoms, such as fevers or chills. Dr. Fine, does MAC explain this patient’s dyspnea?

►Dr. Fine. As her pulmonary symptoms resolved in a short period of time with only azithromycin, it is very unlikely that her symptoms were related to her prior disease. The MAC infection is not likely to cause dyspnea on exertion and fatigue and should be worked up more broadly before attributing it to MAC. In view of this, it would not be unreasonable to follow her clinically and see her again in 6 to 8 weeks. In this context, we also should consider the untoward impact of repeated radiation exposure derived from multiple CT scans. When a patient has an abnormality on CT scan, it often leads to further scans even if the symptoms do not match the previous findings, as in this case.

►Dr. Swamy. Given her ongoing fatigue and systemic symptoms (morning stiffness of the shoulders, legs, and thighs, and leg cramps), she was referred to the rheumatology department where the physical examination revealed muscle tenderness in her proximal arms and legs with normal strength, tender points at the elbows and medial side of the bilateral knees, significant tenderness of lower legs, and no synovitis.

Dr. Monach, can you walk us through your approach to this patient? Are we seeing manifestations of fibromyalgia? What diagnoses concerns you and how would you proceed?

►Dr. Monach. The history and exam are most helpful in raising or reducing suspicion for an underlying inflammatory disease. Areas of tenderness described in her case are typical of fibromyalgia, although it can be difficult to interpret symptoms in the hip girdle and shoulder girdle because objective findings are often absent on exam in patients with inflammatory arthritis or bursitis. Similarly, tenderness at sites of tendon insertion (enthuses) without objective abnormalities is common in different forms of spondyloarthritis, so tenderness at the elbow, knee, lateral hip, and low back can be difficult to interpret. What this patient is lacking is prominent subjective or objective findings in the joints most commonly affected in rheumatoid arthritis and lupus: wrists, hands, ankles, and feet.

►Dr. Swamy. Initial laboratory data include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 79 with a normal C-reactive protein. A tentative diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatic is made with consideration of a trial treatment of prednisone.

Dr. Monach, this patient has an indolent infection and is about to be given glucocorticoids. Could you describe the situations in which you feel that glucocorticoids cause a relative immunosuppression?

►Dr. Monach. Glucocorticoids are considered safe in a patient whose infection is not intrinsically dangerous or who has started appropriate antibiotics for that infection. Although all toxicities of glucocorticoids are dose dependent, the long-standing assertion that doses below 10 mg to 15 mg do not increase risk of infection is contradicted by data published in the past 10 to 15 years, with the caveat that these patients were on long-term treatment.

►Dr. Swamy. The patient was started on prednisone 15 mg per day for 15 days. She returned to the clinic after 1 week of prednisone troutment and noted “significant improvement in fatigue, morning stiffness of shoulders, thighs, leg, back is better, leg cramps resolved, shooting pain in many joints resolved.” Further laboratory results were notable for a negative rheumatoid factor, negative antinuclear antibody, and a cyclic citrullinated peptide of 60. A presumptive diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was made and plaquenil 200 mg twice daily was started.

Dr. Monach, can you explain why RA comes up now on serology but was not considered initially? Why does this presentation fit RA, and was her response to treatment typical? How does this fit in with her previous diagnosis of fibromyalgia? Was that just an atypical, indolent presentation of RA?

►Dr. Monach. Though her presentation is atypical for RA, in elderly patients, RA can present with symptoms resembling polymyalgia rheumatica. The question is whether she had RA all along (in which case “elderly onset” would not apply) or had fibromyalgia and developed RA more recently. The response to empiric glucocorticoid therapy is helpful, since fibromyalgia should not improve with prednisone even in a patient with RA unless treatment of RA would allow better sleep and ability to exercise. Rheumatoid arthritis typically responds very well to prednisone in the 5-mg to 15-mg range.

►Dr. Swamy. Given the new diagnosis of an inflammatory arthritis requiring immunosuppression, bronchoscopy with BAL is performed to evaluate for the presence of MAC. These cultures were positive for MAC.

Dr. Fine, does the positive BAL culture indicate an active MAC infection?

►Dr. Fine. Yes, based on these updated data, the patient has an active MAC infection. Active infection is defined as symptoms or imaging consistent with the diagnosis, supporting microbiology data (either 2 sputum or 1 BAL sample growing MAC) and the exclusion of other causes. Previously, this patient grew MAC in just one expectorated sputum; this did not meet the microbiologic criteria. Now sputum has grown in the BAL sample; along with the CT imaging, this is enough to diagnosis active MAC infection.

Treatment for MAC must consider the details of each case. First, this is not an emergency; treatment decisions should be made with the rheumatologist to consider the planned immunosuppression. For example, we must consider potential drug interactions. A specific point should be made of the use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibition, which data indicate can reactivate TB and may inhibit mechanisms that restrain mycobacterial disease. Serious cases of MAC infection have been reported in the literature in the setting of TNF-α inhibition.5,6 Despite these concerns, there is not a contraindication to using these therapies from the perspective of the active MAC disease. All of these decisions will impact the need to commit the patient to MAC therapy.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, what do you consider prior to initiating MAC therapy?

► Dr. Fine. The decision to pursue MAC therapy should not be taken lightly. Therapy often entails prolonged multidrug regimens, usually spanning more than a year, with frequent adverse effects. Outside of very specific cases, such as TNF-β inhibition, MAC is rarely a life-threatening disease, so the benefit may be limited. Treatment for MAC is certainly unlikely to be fruitful without a diligent and motivated patient able to handle the high and prolonged pill burden. Of note, it is also important to keep this patient up-to-date with influenza and pneumonia vaccination given her structural lung disease.

►Dr. Swamy. The decision is made to treat MAC with azithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol. The disease is noted to be nonfibrocavitary. The patient underwent monthly liver function test monitoring and visual acuity testing, which were unremarkable. Dr. Fine, can you describe the phenotypes of nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) disease?

►Dr. Fine. There are 3 main phenotypes of NTM.3 First, we see the elderly man with preexisting lung disease—usually chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—with fibrocavitary and/or reticulonodular appearance. Second, we see the slim, elderly woman often without any preexisting lung disease presenting with focal bronchiectasis and nodular lesions in right middle lobe and lingula—the Lady Windermere syndrome. This eponym is derived from Oscar Wilde’s play “Lady Windermere’s Fan, a Play About a Good Woman,” and was first associated with this disease in 1992.7 At the time, it was thought that the voluntary suppression of cough led to poorly draining lung regions, vulnerable to engraftment by atypical mycobacteria. Infection with atypical mycobacteria are associated with this population; however, it is no longer thought to be due to the voluntary suppression of cough.7,8 Third, we do occasionally see atypical presentations, such as focal masses and solitary nodules.

►Dr. Swamy. At 1-year follow-up she successfully completed MAC therapy and noted ongoing control of rheumatoid symptoms.

Case Presentation. A 64-year-old US Army veteran with a history of colorectal cancer, melanoma, and fibrinolytic presented with dyspnea to VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS). Seven years prior to the current presentation, at the time of her diagnosis of colorectal cancer, the patient was found to be HIV negative but to have a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) test. She was treated with isoniazid (INH) therapy for 9 months. Sputum cultures collected prior to initiation of therapy grew Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) in 1 of 3 samples, with these results reported several months after initiation of therapy. She was a never smoker with no known travel or exposure. At the time of the current presentation, her medications included bupropion, levothyroxine, capsaicin, cyclobenzaprine, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen.

►Lakshmana Swamy, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Boston Medical Center. Dr. Monach, this patient is on a variety of pain medications and has a diagnosis of fibromyalgia. This diagnosis often frustrates doctors and patients alike. Can you tell us about fibromyalgia from the rheumatologist’s perspective and what you think of her current treatment regimen?

►Paul A. Monach, MD, PhD, Chief, Section of Rheumatology, VABHS and Associate Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Fibromyalgia is a syndrome of chronic widespread pain without known pathology in the musculoskeletal system. It is thought to be caused by chronic dysfunction of pain-processing pathways in the central nervous system (CNS). It is often accompanied by other somatic symptoms such as chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain. It is a common condition, affecting up to 5% of otherwise healthy women. It is particularly common in persons with chronic nonrestorative sleep or posttraumatic stress disorder from a wide range of causes. However, it also is more common in persons with autoimmune inflammatory diseases, such as lupus, Sjögren syndrome, or rheumatoid arthritis. Concern for one of these diseases is the main reason to consider referring a patient for evaluation by a rheumatologist. Often rheumatologists participate in the management of fibromyalgia. A patient should be given appropriate expectations by the referring physician.

Effectiveness of treatment varies widely among patients. Nonpharmacologic approaches such as aerobic exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, and tai chi have support from clinical trials, and yoga and aquatherapy also are widely used.1,2 The classes of drugs used are the same as for neuropathic pain: tricyclics, including cyclobenzaprine; serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs); and gabapentinoids. In contrast, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids are ineffective unless there is a superimposed mechanical or inflammatory cause in the periphery. The key point is that continuation of any treatment should be based entirely on the patient’s own assessment of benefit.

►Dr. Swamy. Seven years later, the patient returned to her primary care provider, reporting increased dyspnea on exertion as well as significant fatigue. She was referred to the pulmonary department and had repeat computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, which indicated persistent right middle lobe (RML) bronchiectasis. She then underwent bronchoscopy with a subsequent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture growing MAC. Dr. Fine, please interpret the baseline and follow-up CT scans and help us understand the significance of the MAC on sputum and BAL cultures.

►Alan Fine, MD, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS and Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Prior to this presentation, the patient had a pleural-based area of fibrosis with possible associated RML bronchiectasis. This appears to be a postinflammatory process without classic features of malignant or metastatic disease. She then had a sputum, which grew MAC in only 1 of 3 samples and in liquid media only. Importantly, the sputum was not smear positive. All of this suggests a low organism burden. One possibility is that this could reflect colonization with MAC; it is not uncommon for patients with underlying chronic changes in their lung to grow MAC, and it is often difficult to tell whether it is indicative of active disease. Structural lung disease, such as bronchiectasis, predisposes a patient to MAC, but chronic MAC also may cause bronchiectasis. This chicken-and-egg scenario comes up frequently. She may have a MAC infection, but as she is HIV negative and asymptomatic, there is no urgent indication to treat, especially as the burden of therapy is not insignificant.

►Dr. Swamy. Do we need to worry about Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)?

►Dr. Fine. Although she was previously PPD positive, she had already completed 1 year of isoniazid (INH) therapy, making active MTB less likely. From an infection control standpoint, it is important to distinguish MAC from MTB. The former is not contagious, and there is no need for airborne isolation.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, where does MAC come from? Does it commonly cause disease?

►Dr. Fine. In the environment, MAC is nearly ubiquitous , especially in water and soil. In one study, 20% of showerheads were positive for MAC; when patients are infected, we may suggest changing/bleaching the showerhead, but there are no definitive recommendations.3 Because MAC is so common in the environment, it is unlikely that measures to target MAC colonization will be clinically meaningful. On the other hand, the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections is increasing across the US, and it may be a common and frequently underdiagnosed cause of chronic cough, especially in postmenopausal women.

►Dr. Swamy. Four years prior to the current presentation, the patient developed a cough after an upper respiratory tract infection that persisted for more than 2 weeks. Given her history, she underwent a repeat chest CT, which noted a slight increase in nodularity and ground-glass opacity restricted to the RML. She also reported dyspnea on exertion and was referred to the pulmonary medicine department. By the time she arrived, her dyspnea had largely resolved, but she reported persistent fatigue without other systemic symptoms, such as fevers or chills. Dr. Fine, does MAC explain this patient’s dyspnea?

►Dr. Fine. As her pulmonary symptoms resolved in a short period of time with only azithromycin, it is very unlikely that her symptoms were related to her prior disease. The MAC infection is not likely to cause dyspnea on exertion and fatigue and should be worked up more broadly before attributing it to MAC. In view of this, it would not be unreasonable to follow her clinically and see her again in 6 to 8 weeks. In this context, we also should consider the untoward impact of repeated radiation exposure derived from multiple CT scans. When a patient has an abnormality on CT scan, it often leads to further scans even if the symptoms do not match the previous findings, as in this case.

►Dr. Swamy. Given her ongoing fatigue and systemic symptoms (morning stiffness of the shoulders, legs, and thighs, and leg cramps), she was referred to the rheumatology department where the physical examination revealed muscle tenderness in her proximal arms and legs with normal strength, tender points at the elbows and medial side of the bilateral knees, significant tenderness of lower legs, and no synovitis.

Dr. Monach, can you walk us through your approach to this patient? Are we seeing manifestations of fibromyalgia? What diagnoses concerns you and how would you proceed?

►Dr. Monach. The history and exam are most helpful in raising or reducing suspicion for an underlying inflammatory disease. Areas of tenderness described in her case are typical of fibromyalgia, although it can be difficult to interpret symptoms in the hip girdle and shoulder girdle because objective findings are often absent on exam in patients with inflammatory arthritis or bursitis. Similarly, tenderness at sites of tendon insertion (enthuses) without objective abnormalities is common in different forms of spondyloarthritis, so tenderness at the elbow, knee, lateral hip, and low back can be difficult to interpret. What this patient is lacking is prominent subjective or objective findings in the joints most commonly affected in rheumatoid arthritis and lupus: wrists, hands, ankles, and feet.

►Dr. Swamy. Initial laboratory data include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 79 with a normal C-reactive protein. A tentative diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatic is made with consideration of a trial treatment of prednisone.

Dr. Monach, this patient has an indolent infection and is about to be given glucocorticoids. Could you describe the situations in which you feel that glucocorticoids cause a relative immunosuppression?

►Dr. Monach. Glucocorticoids are considered safe in a patient whose infection is not intrinsically dangerous or who has started appropriate antibiotics for that infection. Although all toxicities of glucocorticoids are dose dependent, the long-standing assertion that doses below 10 mg to 15 mg do not increase risk of infection is contradicted by data published in the past 10 to 15 years, with the caveat that these patients were on long-term treatment.

►Dr. Swamy. The patient was started on prednisone 15 mg per day for 15 days. She returned to the clinic after 1 week of prednisone troutment and noted “significant improvement in fatigue, morning stiffness of shoulders, thighs, leg, back is better, leg cramps resolved, shooting pain in many joints resolved.” Further laboratory results were notable for a negative rheumatoid factor, negative antinuclear antibody, and a cyclic citrullinated peptide of 60. A presumptive diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was made and plaquenil 200 mg twice daily was started.

Dr. Monach, can you explain why RA comes up now on serology but was not considered initially? Why does this presentation fit RA, and was her response to treatment typical? How does this fit in with her previous diagnosis of fibromyalgia? Was that just an atypical, indolent presentation of RA?

►Dr. Monach. Though her presentation is atypical for RA, in elderly patients, RA can present with symptoms resembling polymyalgia rheumatica. The question is whether she had RA all along (in which case “elderly onset” would not apply) or had fibromyalgia and developed RA more recently. The response to empiric glucocorticoid therapy is helpful, since fibromyalgia should not improve with prednisone even in a patient with RA unless treatment of RA would allow better sleep and ability to exercise. Rheumatoid arthritis typically responds very well to prednisone in the 5-mg to 15-mg range.

►Dr. Swamy. Given the new diagnosis of an inflammatory arthritis requiring immunosuppression, bronchoscopy with BAL is performed to evaluate for the presence of MAC. These cultures were positive for MAC.

Dr. Fine, does the positive BAL culture indicate an active MAC infection?

►Dr. Fine. Yes, based on these updated data, the patient has an active MAC infection. Active infection is defined as symptoms or imaging consistent with the diagnosis, supporting microbiology data (either 2 sputum or 1 BAL sample growing MAC) and the exclusion of other causes. Previously, this patient grew MAC in just one expectorated sputum; this did not meet the microbiologic criteria. Now sputum has grown in the BAL sample; along with the CT imaging, this is enough to diagnosis active MAC infection.

Treatment for MAC must consider the details of each case. First, this is not an emergency; treatment decisions should be made with the rheumatologist to consider the planned immunosuppression. For example, we must consider potential drug interactions. A specific point should be made of the use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibition, which data indicate can reactivate TB and may inhibit mechanisms that restrain mycobacterial disease. Serious cases of MAC infection have been reported in the literature in the setting of TNF-α inhibition.5,6 Despite these concerns, there is not a contraindication to using these therapies from the perspective of the active MAC disease. All of these decisions will impact the need to commit the patient to MAC therapy.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, what do you consider prior to initiating MAC therapy?

► Dr. Fine. The decision to pursue MAC therapy should not be taken lightly. Therapy often entails prolonged multidrug regimens, usually spanning more than a year, with frequent adverse effects. Outside of very specific cases, such as TNF-β inhibition, MAC is rarely a life-threatening disease, so the benefit may be limited. Treatment for MAC is certainly unlikely to be fruitful without a diligent and motivated patient able to handle the high and prolonged pill burden. Of note, it is also important to keep this patient up-to-date with influenza and pneumonia vaccination given her structural lung disease.

►Dr. Swamy. The decision is made to treat MAC with azithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol. The disease is noted to be nonfibrocavitary. The patient underwent monthly liver function test monitoring and visual acuity testing, which were unremarkable. Dr. Fine, can you describe the phenotypes of nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) disease?