User login

Moderna says boosters may be needed after 6 months

Moderna says neutralizing antibodies generated by its COVID-19 vaccine against three variants of the virus that causes the disease waned substantially 6 months after the second dose.

Because of this, the company expects an increase in breakthrough infections with a need for boosters before winter.

In an experiment, a 50-mg dose of the vaccine, given as a third shot, boosted levels of antibodies in 20 previously vaccinated people by 32 times against the Beta variant, by 44 times against the Gamma variant, and by 42 times against Delta.

The new data was presented in an earnings call to investors and is based on a small study that hasn’t yet been published in medical literature.

The company also said its vaccine remained highly effective at preventing severe COVID outcomes through 6 months.

Last week, Pfizer released early data suggesting a similar drop in protection from its vaccine. The company also showed a third dose substantially boosted protection, including against the Delta variant.

The new results come just 1 day after the World Health Organization implored wealthy nations to hold off on third doses until more of the world’s population could get a first dose.

More than 80% of the 4 billion vaccine doses given around the world have been distributed to high-income countries.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Moderna says neutralizing antibodies generated by its COVID-19 vaccine against three variants of the virus that causes the disease waned substantially 6 months after the second dose.

Because of this, the company expects an increase in breakthrough infections with a need for boosters before winter.

In an experiment, a 50-mg dose of the vaccine, given as a third shot, boosted levels of antibodies in 20 previously vaccinated people by 32 times against the Beta variant, by 44 times against the Gamma variant, and by 42 times against Delta.

The new data was presented in an earnings call to investors and is based on a small study that hasn’t yet been published in medical literature.

The company also said its vaccine remained highly effective at preventing severe COVID outcomes through 6 months.

Last week, Pfizer released early data suggesting a similar drop in protection from its vaccine. The company also showed a third dose substantially boosted protection, including against the Delta variant.

The new results come just 1 day after the World Health Organization implored wealthy nations to hold off on third doses until more of the world’s population could get a first dose.

More than 80% of the 4 billion vaccine doses given around the world have been distributed to high-income countries.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Moderna says neutralizing antibodies generated by its COVID-19 vaccine against three variants of the virus that causes the disease waned substantially 6 months after the second dose.

Because of this, the company expects an increase in breakthrough infections with a need for boosters before winter.

In an experiment, a 50-mg dose of the vaccine, given as a third shot, boosted levels of antibodies in 20 previously vaccinated people by 32 times against the Beta variant, by 44 times against the Gamma variant, and by 42 times against Delta.

The new data was presented in an earnings call to investors and is based on a small study that hasn’t yet been published in medical literature.

The company also said its vaccine remained highly effective at preventing severe COVID outcomes through 6 months.

Last week, Pfizer released early data suggesting a similar drop in protection from its vaccine. The company also showed a third dose substantially boosted protection, including against the Delta variant.

The new results come just 1 day after the World Health Organization implored wealthy nations to hold off on third doses until more of the world’s population could get a first dose.

More than 80% of the 4 billion vaccine doses given around the world have been distributed to high-income countries.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Vaccine breakthrough cases rising with Delta: Here’s what that means

At a recent town hall meeting in Cincinnati, President Joe Biden was asked about COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths rising in response to the Delta variant.

Touting the importance of vaccination, “We have a pandemic for those who haven’t gotten a vaccination. It’s that basic, that simple,” President Biden said at the event, which was broadcast live on CNN.

“If you’re vaccinated, you’re not going to be hospitalized, not going to the ICU unit, and not going to die,” he said, adding “you’re not going to get COVID if you have these vaccinations.”

Unfortunately, it’s not so simple. Fully vaccinated people continue to be well protected against severe disease and death, even with Delta, Because of that, many experts continue to advise caution, even if fully vaccinated.

“I was disappointed,” Leana Wen, MD, MSc, an emergency physician and visiting professor of health policy and management at George Washington University’s Milken School of Public Health in Washington, told CNN in response to the president’s statement.

“I actually thought he was answering questions as if it were a month ago. He’s not really meeting the realities of what’s happening on the ground,” she said. “I think he may have led people astray.”

Vaccines still work

Recent cases support Dr. Wen’s claim. Fully vaccinated Olympic athletes, wedding guests, healthcare workers, and even White House staff have recently tested positive. So what gives?

The vast majority of these illnesses are mild, and public health officials say they are to be expected.

“The vaccines were designed to keep us out of the hospital and to keep us from dying. That was the whole purpose of the vaccine and they’re even more successful than we anticipated,” says William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

As good as they are, these shots aren’t perfect. Their protection differs from person to person depending on age and underlying health. People with immune function that’s weakened because of age or a health condition can still become seriously ill, and, in very rare cases, die after vaccination.

When people are infected with Delta, they carry approximately 1,000 times more virus compared with previous versions of the virus, according to a recent study. All that virus can overwhelm even the strong protection from the vaccines.

“Three months ago, breakthroughs didn’t occur nearly at this rate because there was just so much less virus exposure in the community,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Breakthroughs by the numbers

In Los Angeles County, where 69% of residents over age 12 have been fully vaccinated, COVID-19 cases are rising, and so, too, are cases that break through the protection of the vaccine.

In June, fully vaccinated people accounted for 20%, or 1 in 5, COVID cases in the county, which is the most populous in the United States. The increase mirrors Delta’s rise. The proportion of breakthrough cases is up from 11% in May, 5% in April, and 2% in March, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

In the United Kingdom, which is collecting the best information on infections caused by variants, the estimated effectiveness of the vaccines to prevent an illness that causes symptoms dropped by about 10 points against Delta compared with Alpha (or B.1.1.7).

After two doses, vaccines prevent symptomatic infection about 79% of the time against Delta, according to data compiled by Public Health England. They are still highly effective at preventing hospitalization, 96% after two doses.

Out of 229,218 COVID infections in the United Kingdom between February and July 19, 28,773 — or 12.5% — were in fully vaccinated people. Of those breakthrough infections, 1,101, or 3.8%, required a visit to an emergency room, according to Public Health England. Just 474, or 2.9%, of fully vaccinated people required hospital admission, and 229, or less than 1%, died.

Unanswered questions

One of the biggest questions about breakthrough cases is how often people who have it may pass the virus to others.

“We know the vaccine reduces the likelihood of carrying the virus and the amount of virus you would carry,” Dr. Wen told CNN. But we don’t yet know whether a vaccinated person with a breakthrough infection may still be contagious to others.

For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that fully vaccinated people still need to be tested if they have symptoms and shouldn’t be out in public for at least 10 days after a positive test.

How should fully vaccinated people behave? That depends a lot on their underlying health and whether or not they have vulnerable people around them.

If you’re older or immunocompromised, Dr. Schaffner recommends what he calls the “belt-and-suspenders approach,” in other words, do everything you can to stay safe.

“Get vaccinated for sure, but since we can’t be absolutely certain that the vaccines are going to be optimally protective and you are particularly susceptible to serious disease, you would be well advised to adopt at least one and perhaps more of the other mitigation measures,” he said.

These include wearing a mask, social distancing, making sure your spaces are well ventilated, and not spending prolonged periods of time indoors in crowded places.

Taking young children to visit vaccinated, elderly grandparents demands extra caution, again, with Delta circulating, particularly as they go back to school and start mixing with other kids.

Dr. Schaffner recommends explaining the ground rules before the visit: Hugs around the waist. No kissing. Wearing a mask while indoors with them.

Other important unanswered questions are whether breakthrough infections can lead to prolonged symptoms, or “long covid.” Most experts think that’s less likely in vaccinated people.

And Dr. Osterholm said it will be important to see whether there’s anything unusual about the breakthrough cases happening in the community.

“I think some of us have been challenged by the number of clusters that we’ve seen,” he said. “I think that really needs to be examined more.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

At a recent town hall meeting in Cincinnati, President Joe Biden was asked about COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths rising in response to the Delta variant.

Touting the importance of vaccination, “We have a pandemic for those who haven’t gotten a vaccination. It’s that basic, that simple,” President Biden said at the event, which was broadcast live on CNN.

“If you’re vaccinated, you’re not going to be hospitalized, not going to the ICU unit, and not going to die,” he said, adding “you’re not going to get COVID if you have these vaccinations.”

Unfortunately, it’s not so simple. Fully vaccinated people continue to be well protected against severe disease and death, even with Delta, Because of that, many experts continue to advise caution, even if fully vaccinated.

“I was disappointed,” Leana Wen, MD, MSc, an emergency physician and visiting professor of health policy and management at George Washington University’s Milken School of Public Health in Washington, told CNN in response to the president’s statement.

“I actually thought he was answering questions as if it were a month ago. He’s not really meeting the realities of what’s happening on the ground,” she said. “I think he may have led people astray.”

Vaccines still work

Recent cases support Dr. Wen’s claim. Fully vaccinated Olympic athletes, wedding guests, healthcare workers, and even White House staff have recently tested positive. So what gives?

The vast majority of these illnesses are mild, and public health officials say they are to be expected.

“The vaccines were designed to keep us out of the hospital and to keep us from dying. That was the whole purpose of the vaccine and they’re even more successful than we anticipated,” says William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

As good as they are, these shots aren’t perfect. Their protection differs from person to person depending on age and underlying health. People with immune function that’s weakened because of age or a health condition can still become seriously ill, and, in very rare cases, die after vaccination.

When people are infected with Delta, they carry approximately 1,000 times more virus compared with previous versions of the virus, according to a recent study. All that virus can overwhelm even the strong protection from the vaccines.

“Three months ago, breakthroughs didn’t occur nearly at this rate because there was just so much less virus exposure in the community,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Breakthroughs by the numbers

In Los Angeles County, where 69% of residents over age 12 have been fully vaccinated, COVID-19 cases are rising, and so, too, are cases that break through the protection of the vaccine.

In June, fully vaccinated people accounted for 20%, or 1 in 5, COVID cases in the county, which is the most populous in the United States. The increase mirrors Delta’s rise. The proportion of breakthrough cases is up from 11% in May, 5% in April, and 2% in March, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

In the United Kingdom, which is collecting the best information on infections caused by variants, the estimated effectiveness of the vaccines to prevent an illness that causes symptoms dropped by about 10 points against Delta compared with Alpha (or B.1.1.7).

After two doses, vaccines prevent symptomatic infection about 79% of the time against Delta, according to data compiled by Public Health England. They are still highly effective at preventing hospitalization, 96% after two doses.

Out of 229,218 COVID infections in the United Kingdom between February and July 19, 28,773 — or 12.5% — were in fully vaccinated people. Of those breakthrough infections, 1,101, or 3.8%, required a visit to an emergency room, according to Public Health England. Just 474, or 2.9%, of fully vaccinated people required hospital admission, and 229, or less than 1%, died.

Unanswered questions

One of the biggest questions about breakthrough cases is how often people who have it may pass the virus to others.

“We know the vaccine reduces the likelihood of carrying the virus and the amount of virus you would carry,” Dr. Wen told CNN. But we don’t yet know whether a vaccinated person with a breakthrough infection may still be contagious to others.

For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that fully vaccinated people still need to be tested if they have symptoms and shouldn’t be out in public for at least 10 days after a positive test.

How should fully vaccinated people behave? That depends a lot on their underlying health and whether or not they have vulnerable people around them.

If you’re older or immunocompromised, Dr. Schaffner recommends what he calls the “belt-and-suspenders approach,” in other words, do everything you can to stay safe.

“Get vaccinated for sure, but since we can’t be absolutely certain that the vaccines are going to be optimally protective and you are particularly susceptible to serious disease, you would be well advised to adopt at least one and perhaps more of the other mitigation measures,” he said.

These include wearing a mask, social distancing, making sure your spaces are well ventilated, and not spending prolonged periods of time indoors in crowded places.

Taking young children to visit vaccinated, elderly grandparents demands extra caution, again, with Delta circulating, particularly as they go back to school and start mixing with other kids.

Dr. Schaffner recommends explaining the ground rules before the visit: Hugs around the waist. No kissing. Wearing a mask while indoors with them.

Other important unanswered questions are whether breakthrough infections can lead to prolonged symptoms, or “long covid.” Most experts think that’s less likely in vaccinated people.

And Dr. Osterholm said it will be important to see whether there’s anything unusual about the breakthrough cases happening in the community.

“I think some of us have been challenged by the number of clusters that we’ve seen,” he said. “I think that really needs to be examined more.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

At a recent town hall meeting in Cincinnati, President Joe Biden was asked about COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths rising in response to the Delta variant.

Touting the importance of vaccination, “We have a pandemic for those who haven’t gotten a vaccination. It’s that basic, that simple,” President Biden said at the event, which was broadcast live on CNN.

“If you’re vaccinated, you’re not going to be hospitalized, not going to the ICU unit, and not going to die,” he said, adding “you’re not going to get COVID if you have these vaccinations.”

Unfortunately, it’s not so simple. Fully vaccinated people continue to be well protected against severe disease and death, even with Delta, Because of that, many experts continue to advise caution, even if fully vaccinated.

“I was disappointed,” Leana Wen, MD, MSc, an emergency physician and visiting professor of health policy and management at George Washington University’s Milken School of Public Health in Washington, told CNN in response to the president’s statement.

“I actually thought he was answering questions as if it were a month ago. He’s not really meeting the realities of what’s happening on the ground,” she said. “I think he may have led people astray.”

Vaccines still work

Recent cases support Dr. Wen’s claim. Fully vaccinated Olympic athletes, wedding guests, healthcare workers, and even White House staff have recently tested positive. So what gives?

The vast majority of these illnesses are mild, and public health officials say they are to be expected.

“The vaccines were designed to keep us out of the hospital and to keep us from dying. That was the whole purpose of the vaccine and they’re even more successful than we anticipated,” says William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

As good as they are, these shots aren’t perfect. Their protection differs from person to person depending on age and underlying health. People with immune function that’s weakened because of age or a health condition can still become seriously ill, and, in very rare cases, die after vaccination.

When people are infected with Delta, they carry approximately 1,000 times more virus compared with previous versions of the virus, according to a recent study. All that virus can overwhelm even the strong protection from the vaccines.

“Three months ago, breakthroughs didn’t occur nearly at this rate because there was just so much less virus exposure in the community,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Breakthroughs by the numbers

In Los Angeles County, where 69% of residents over age 12 have been fully vaccinated, COVID-19 cases are rising, and so, too, are cases that break through the protection of the vaccine.

In June, fully vaccinated people accounted for 20%, or 1 in 5, COVID cases in the county, which is the most populous in the United States. The increase mirrors Delta’s rise. The proportion of breakthrough cases is up from 11% in May, 5% in April, and 2% in March, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

In the United Kingdom, which is collecting the best information on infections caused by variants, the estimated effectiveness of the vaccines to prevent an illness that causes symptoms dropped by about 10 points against Delta compared with Alpha (or B.1.1.7).

After two doses, vaccines prevent symptomatic infection about 79% of the time against Delta, according to data compiled by Public Health England. They are still highly effective at preventing hospitalization, 96% after two doses.

Out of 229,218 COVID infections in the United Kingdom between February and July 19, 28,773 — or 12.5% — were in fully vaccinated people. Of those breakthrough infections, 1,101, or 3.8%, required a visit to an emergency room, according to Public Health England. Just 474, or 2.9%, of fully vaccinated people required hospital admission, and 229, or less than 1%, died.

Unanswered questions

One of the biggest questions about breakthrough cases is how often people who have it may pass the virus to others.

“We know the vaccine reduces the likelihood of carrying the virus and the amount of virus you would carry,” Dr. Wen told CNN. But we don’t yet know whether a vaccinated person with a breakthrough infection may still be contagious to others.

For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that fully vaccinated people still need to be tested if they have symptoms and shouldn’t be out in public for at least 10 days after a positive test.

How should fully vaccinated people behave? That depends a lot on their underlying health and whether or not they have vulnerable people around them.

If you’re older or immunocompromised, Dr. Schaffner recommends what he calls the “belt-and-suspenders approach,” in other words, do everything you can to stay safe.

“Get vaccinated for sure, but since we can’t be absolutely certain that the vaccines are going to be optimally protective and you are particularly susceptible to serious disease, you would be well advised to adopt at least one and perhaps more of the other mitigation measures,” he said.

These include wearing a mask, social distancing, making sure your spaces are well ventilated, and not spending prolonged periods of time indoors in crowded places.

Taking young children to visit vaccinated, elderly grandparents demands extra caution, again, with Delta circulating, particularly as they go back to school and start mixing with other kids.

Dr. Schaffner recommends explaining the ground rules before the visit: Hugs around the waist. No kissing. Wearing a mask while indoors with them.

Other important unanswered questions are whether breakthrough infections can lead to prolonged symptoms, or “long covid.” Most experts think that’s less likely in vaccinated people.

And Dr. Osterholm said it will be important to see whether there’s anything unusual about the breakthrough cases happening in the community.

“I think some of us have been challenged by the number of clusters that we’ve seen,” he said. “I think that really needs to be examined more.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Dealing with a different beast’: Why Delta has doctors worried

Catherine O’Neal, MD, an infectious disease physician, took to the podium of the Louisiana governor’s press conference recently and did not mince words.

“The Delta variant is not last year’s virus, and it’s become incredibly apparent to healthcare workers that we are dealing with a different beast,” she said.

Louisiana is one of the least vaccinated states in the country. In the United States as a whole, 48.6% of the population is fully vaccinated. In Louisiana, it’s just 36%, and Delta is bearing down.

Dr. O’Neal spoke about the pressure that rising COVID cases were already putting on her hospital, Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge. She talked about watching her peers, 30- and 40-year-olds, become severely ill with the latest iteration of the new coronavirus — the Delta variant — which is sweeping through the United States with astonishing speed, causing new cases, hospitalizations, and deaths to rise again.

Dr. O’Neal talked about parents who might not be alive to see their children go off to college in a few weeks. She talked about increasing hospital admissions for infected kids and pregnant women on ventilators.

“I want to be clear after seeing what we’ve seen the last two weeks. We only have two choices: We are either going to get vaccinated and end the pandemic, or we’re going to accept death and a lot of it,” Dr. O’Neal said, her voice choked by emotion.

Where Delta goes, death follows

Delta was first identified in India, where it caused a devastating surge in the spring. In a population that was largely unvaccinated, researchers think it may have caused as many as three million deaths. In just a few months’ time, it has sped across the globe.

, which was first identified in the United Kingdom).

Where a single infected person might have spread older versions of the virus to two or three others, mathematician and epidemiologist Adam Kucharski, PhD, an associate professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, thinks that number — called the basic reproduction number — might be around six for Delta, meaning that, on average, each infected person spreads the virus to six others.

“The Delta variant is the most able and fastest and fittest of those viruses,” said Mike Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization’s Health Emergencies Programme, in a recent press briefing.

Early evidence suggests it may also cause more severe disease in people who are not vaccinated.

“There’s clearly increased risk of ICU admission, hospitalization, and death,” said Ashleigh Tuite, PhD, MPH, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Toronto in Ontario.

In a study published ahead of peer review, Dr. Tuite and her coauthor, David Fisman, MD, MPH, reviewed the health outcomes for more than 200,000 people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Ontario between February and June of 2021. Starting in February, Ontario began screening all positive COVID tests for mutations in the N501Y region for signs of mutation.

Compared with versions of the coronavirus that circulated in 2020, having an Alpha, Beta, or Gamma variant modestly increased the odds that an infected person would become sicker. The Delta variant raised the risk even higher, more than doubling the odds that an infected person would need to be hospitalized or could die from their infection.

Emerging evidence from England and Scotland, analyzed by Public Health England, also shows an increased risk for hospitalization with Delta. The increases are in line with the Canadian data. Experts caution that the picture may change over time as more evidence is gathered.

“What is causing that? We don’t know,” Dr. Tuite said.

Enhanced virus

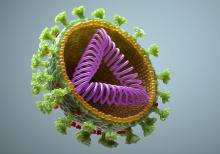

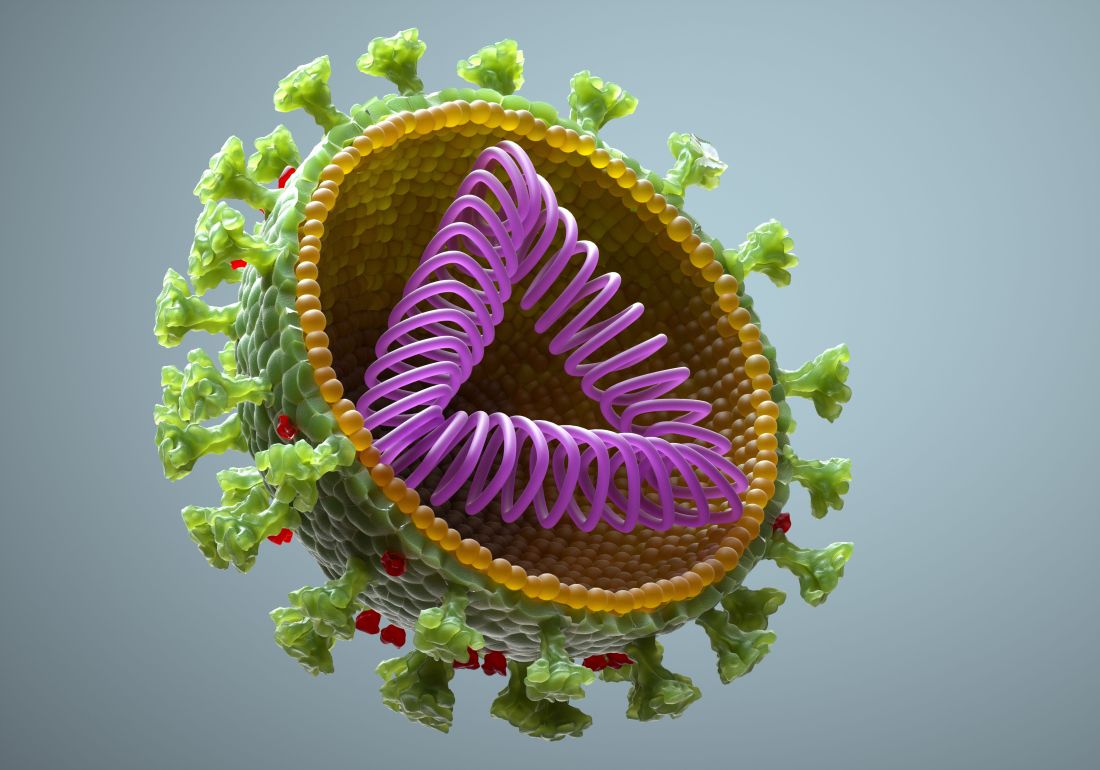

The Delta variants (there’s actually more than one in the same viral family) have about 15 different mutations compared with the original virus. Two of these, L452R and E484Q, are mutations to the spike protein that were first flagged as problematic in other variants because they appear to help the virus escape the antibodies we make to fight it.

It has another mutation away from its binding site that’s also getting researchers’ attention — P681R.

This mutation appears to enhance the “springiness” of the parts of the virus that dock onto our cells, said Alexander Greninger, MD, PhD, assistant director of the UW Medicine Clinical Virology Laboratory at the University of Washington in Seattle. So it’s more likely to be in the right position to infect our cells if we come into contact with it.

Another theory is that P681R may also enhance the virus’s ability to fuse cells together into clumps that have several different nuclei. These balls of fused cells are called syncytia.

“So it turns into a big factory for making viruses,” said Kamran Kadkhoda, PhD, medical director of immunopathology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

This capability is not unique to Delta or even to the new coronavirus. Earlier versions and other viruses can do the same thing, but according to a recent paper in Nature, the syncytia that Delta creates are larger than the ones created by previous variants.

Scientists aren’t sure what these supersized syncytia mean, exactly, but they have some theories. They may help the virus copy itself more quickly, so a person’s viral load builds up quickly. That may enhance the ability of the virus to transmit from person to person.

And at least one recent study from China supports this idea. That study, which was posted ahead of peer review on the website Virological.org, tracked 167 people infected with Delta back to a single index case.

China has used extensive contact tracing to identify people that may have been exposed to the virus and sequester them quickly to tamp down its spread. Once a person is isolated or quarantined, they are tested daily with gold-standard PCR testing to determine whether or not they were infected.

Researchers compared the characteristics of Delta cases with those of people infected in 2020 with previous versions of the virus.

This study found that people infected by Delta tested positive more quickly than their predecessors did. In 2020, it took an average of 6 days for someone to test positive after an exposure. With Delta, it took an average of about 4 days.

When people tested positive, they had more than 1,000 times more virus in their bodies, suggesting that the Delta variant has a higher growth rate in the body.

This gives Delta a big advantage. According to Angie Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, who posted a thread about the study on Twitter, if people are shedding 1,000 times more virus, it is much more likely that close contacts will be exposed to enough of it to become infected themselves.

And if they’re shedding earlier in the course of their infections, the virus has more opportunity to spread.

This may help explain why Delta is so much more contagious.

Beyond transmission, Delta’s ability to form syncytia may have two other important consequences. It may help the virus hide from our immune system, and it may make the virus more damaging to the body.

Commonly, when a virus infects a cell, it will corrupt the cell’s protein-making machinery to crank out more copies of itself. When the cell dies, these new copies are released into the plasma outside the cell where they can float over and infect new cells. It’s in this extracellular space where a virus can also be attacked by the neutralizing antibodies our immune system makes to fight it off.

“Antibodies don’t penetrate inside the cell. If these viruses are going from one cell to another by just fusing to each other, antibodies become less useful,” Dr. Kadkhoda said.

Escape artist

Recent studies show that Delta is also able to escape antibodies made in response to vaccination more effectively than the Alpha, or B.1.1.7 strain. The effect was more pronounced in older adults, who tend to have weaker responses to vaccines in general.

This evasion of the immune system is particularly problematic for people who are only partially vaccinated. Data from the United Kingdom show that a single dose of vaccine is only about 31% effective at preventing illness with Delta, and 75% effective at preventing hospitalization.

After two doses, the vaccines are still highly effective — even against Delta — reaching 80% protection for illness, and 94% for hospitalization, which is why U.S. officials are begging people to get both doses of their shots, and do it as quickly as possible.

Finally, the virus’s ability to form syncytia may leave greater damage behind in the body’s tissues and organs.

“Especially in the lungs,” Dr. Kadkhoda said. The lungs are very fragile tissues. Their tiny air sacs — the alveoli — are only a single-cell thick. They have to be very thin to exchange oxygen in the blood.

“Any damage like that can severely affect any oxygen exchange and the normal housekeeping activities of that tissue,” he said. “In those vital organs, it may be very problematic.”

The research is still early, but studies in animals and cell lines are backing up what doctors say they are seeing in hospitalized patients.

A recent preprint study from researchers in Japan found that hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight — a proxy for how sick they were — compared with hamsters infected with an older version of the virus. The researchers attribute this to the viruses› ability to fuse cells together to form syncytia.

Another investigation, from researchers in India, infected two groups of hamsters — one with the original “wild type” strain of the virus, the other with the Delta variant of the new coronavirus.

As in the Japanese study, the hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight. When the researchers performed necropsies on the animals, they found more lung damage and bleeding in hamsters infected with Delta. This study was also posted as a preprint ahead of peer review.

German researchers working with pseudotyped versions of the new coronavirus — viruses that have been genetically changed to make them safer to work with — watched what happened after they used these pseudoviruses to infect lung, colon, and kidney cells in the lab.

They, too, found that cells infected with the Delta variant formed more and larger syncytia compared with cells infected with the wild type strain of the virus. The authors write that their findings suggest Delta could “cause more tissue damage, and thus be more pathogenic, than previous variants.”Researchers say it’s important to remember that, while interesting, this research isn’t conclusive. Hamsters and cells aren’t humans. More studies are needed to prove these theories.

Scientists say that what we already know about Delta makes vaccination more important than ever.

“The net effect is really that, you know, this is worrisome in people who are unvaccinated and then people who have breakthrough infections, but it’s not…a reason to panic or to throw up our hands and say you know, this pandemic is never going to end,” Dr. Tuite said, “[b]ecause what we do see is that the vaccines continue to be highly protective.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Catherine O’Neal, MD, an infectious disease physician, took to the podium of the Louisiana governor’s press conference recently and did not mince words.

“The Delta variant is not last year’s virus, and it’s become incredibly apparent to healthcare workers that we are dealing with a different beast,” she said.

Louisiana is one of the least vaccinated states in the country. In the United States as a whole, 48.6% of the population is fully vaccinated. In Louisiana, it’s just 36%, and Delta is bearing down.

Dr. O’Neal spoke about the pressure that rising COVID cases were already putting on her hospital, Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge. She talked about watching her peers, 30- and 40-year-olds, become severely ill with the latest iteration of the new coronavirus — the Delta variant — which is sweeping through the United States with astonishing speed, causing new cases, hospitalizations, and deaths to rise again.

Dr. O’Neal talked about parents who might not be alive to see their children go off to college in a few weeks. She talked about increasing hospital admissions for infected kids and pregnant women on ventilators.

“I want to be clear after seeing what we’ve seen the last two weeks. We only have two choices: We are either going to get vaccinated and end the pandemic, or we’re going to accept death and a lot of it,” Dr. O’Neal said, her voice choked by emotion.

Where Delta goes, death follows

Delta was first identified in India, where it caused a devastating surge in the spring. In a population that was largely unvaccinated, researchers think it may have caused as many as three million deaths. In just a few months’ time, it has sped across the globe.

, which was first identified in the United Kingdom).

Where a single infected person might have spread older versions of the virus to two or three others, mathematician and epidemiologist Adam Kucharski, PhD, an associate professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, thinks that number — called the basic reproduction number — might be around six for Delta, meaning that, on average, each infected person spreads the virus to six others.

“The Delta variant is the most able and fastest and fittest of those viruses,” said Mike Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization’s Health Emergencies Programme, in a recent press briefing.

Early evidence suggests it may also cause more severe disease in people who are not vaccinated.

“There’s clearly increased risk of ICU admission, hospitalization, and death,” said Ashleigh Tuite, PhD, MPH, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Toronto in Ontario.

In a study published ahead of peer review, Dr. Tuite and her coauthor, David Fisman, MD, MPH, reviewed the health outcomes for more than 200,000 people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Ontario between February and June of 2021. Starting in February, Ontario began screening all positive COVID tests for mutations in the N501Y region for signs of mutation.

Compared with versions of the coronavirus that circulated in 2020, having an Alpha, Beta, or Gamma variant modestly increased the odds that an infected person would become sicker. The Delta variant raised the risk even higher, more than doubling the odds that an infected person would need to be hospitalized or could die from their infection.

Emerging evidence from England and Scotland, analyzed by Public Health England, also shows an increased risk for hospitalization with Delta. The increases are in line with the Canadian data. Experts caution that the picture may change over time as more evidence is gathered.

“What is causing that? We don’t know,” Dr. Tuite said.

Enhanced virus

The Delta variants (there’s actually more than one in the same viral family) have about 15 different mutations compared with the original virus. Two of these, L452R and E484Q, are mutations to the spike protein that were first flagged as problematic in other variants because they appear to help the virus escape the antibodies we make to fight it.

It has another mutation away from its binding site that’s also getting researchers’ attention — P681R.

This mutation appears to enhance the “springiness” of the parts of the virus that dock onto our cells, said Alexander Greninger, MD, PhD, assistant director of the UW Medicine Clinical Virology Laboratory at the University of Washington in Seattle. So it’s more likely to be in the right position to infect our cells if we come into contact with it.

Another theory is that P681R may also enhance the virus’s ability to fuse cells together into clumps that have several different nuclei. These balls of fused cells are called syncytia.

“So it turns into a big factory for making viruses,” said Kamran Kadkhoda, PhD, medical director of immunopathology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

This capability is not unique to Delta or even to the new coronavirus. Earlier versions and other viruses can do the same thing, but according to a recent paper in Nature, the syncytia that Delta creates are larger than the ones created by previous variants.

Scientists aren’t sure what these supersized syncytia mean, exactly, but they have some theories. They may help the virus copy itself more quickly, so a person’s viral load builds up quickly. That may enhance the ability of the virus to transmit from person to person.

And at least one recent study from China supports this idea. That study, which was posted ahead of peer review on the website Virological.org, tracked 167 people infected with Delta back to a single index case.

China has used extensive contact tracing to identify people that may have been exposed to the virus and sequester them quickly to tamp down its spread. Once a person is isolated or quarantined, they are tested daily with gold-standard PCR testing to determine whether or not they were infected.

Researchers compared the characteristics of Delta cases with those of people infected in 2020 with previous versions of the virus.

This study found that people infected by Delta tested positive more quickly than their predecessors did. In 2020, it took an average of 6 days for someone to test positive after an exposure. With Delta, it took an average of about 4 days.

When people tested positive, they had more than 1,000 times more virus in their bodies, suggesting that the Delta variant has a higher growth rate in the body.

This gives Delta a big advantage. According to Angie Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, who posted a thread about the study on Twitter, if people are shedding 1,000 times more virus, it is much more likely that close contacts will be exposed to enough of it to become infected themselves.

And if they’re shedding earlier in the course of their infections, the virus has more opportunity to spread.

This may help explain why Delta is so much more contagious.

Beyond transmission, Delta’s ability to form syncytia may have two other important consequences. It may help the virus hide from our immune system, and it may make the virus more damaging to the body.

Commonly, when a virus infects a cell, it will corrupt the cell’s protein-making machinery to crank out more copies of itself. When the cell dies, these new copies are released into the plasma outside the cell where they can float over and infect new cells. It’s in this extracellular space where a virus can also be attacked by the neutralizing antibodies our immune system makes to fight it off.

“Antibodies don’t penetrate inside the cell. If these viruses are going from one cell to another by just fusing to each other, antibodies become less useful,” Dr. Kadkhoda said.

Escape artist

Recent studies show that Delta is also able to escape antibodies made in response to vaccination more effectively than the Alpha, or B.1.1.7 strain. The effect was more pronounced in older adults, who tend to have weaker responses to vaccines in general.

This evasion of the immune system is particularly problematic for people who are only partially vaccinated. Data from the United Kingdom show that a single dose of vaccine is only about 31% effective at preventing illness with Delta, and 75% effective at preventing hospitalization.

After two doses, the vaccines are still highly effective — even against Delta — reaching 80% protection for illness, and 94% for hospitalization, which is why U.S. officials are begging people to get both doses of their shots, and do it as quickly as possible.

Finally, the virus’s ability to form syncytia may leave greater damage behind in the body’s tissues and organs.

“Especially in the lungs,” Dr. Kadkhoda said. The lungs are very fragile tissues. Their tiny air sacs — the alveoli — are only a single-cell thick. They have to be very thin to exchange oxygen in the blood.

“Any damage like that can severely affect any oxygen exchange and the normal housekeeping activities of that tissue,” he said. “In those vital organs, it may be very problematic.”

The research is still early, but studies in animals and cell lines are backing up what doctors say they are seeing in hospitalized patients.

A recent preprint study from researchers in Japan found that hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight — a proxy for how sick they were — compared with hamsters infected with an older version of the virus. The researchers attribute this to the viruses› ability to fuse cells together to form syncytia.

Another investigation, from researchers in India, infected two groups of hamsters — one with the original “wild type” strain of the virus, the other with the Delta variant of the new coronavirus.

As in the Japanese study, the hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight. When the researchers performed necropsies on the animals, they found more lung damage and bleeding in hamsters infected with Delta. This study was also posted as a preprint ahead of peer review.

German researchers working with pseudotyped versions of the new coronavirus — viruses that have been genetically changed to make them safer to work with — watched what happened after they used these pseudoviruses to infect lung, colon, and kidney cells in the lab.

They, too, found that cells infected with the Delta variant formed more and larger syncytia compared with cells infected with the wild type strain of the virus. The authors write that their findings suggest Delta could “cause more tissue damage, and thus be more pathogenic, than previous variants.”Researchers say it’s important to remember that, while interesting, this research isn’t conclusive. Hamsters and cells aren’t humans. More studies are needed to prove these theories.

Scientists say that what we already know about Delta makes vaccination more important than ever.

“The net effect is really that, you know, this is worrisome in people who are unvaccinated and then people who have breakthrough infections, but it’s not…a reason to panic or to throw up our hands and say you know, this pandemic is never going to end,” Dr. Tuite said, “[b]ecause what we do see is that the vaccines continue to be highly protective.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Catherine O’Neal, MD, an infectious disease physician, took to the podium of the Louisiana governor’s press conference recently and did not mince words.

“The Delta variant is not last year’s virus, and it’s become incredibly apparent to healthcare workers that we are dealing with a different beast,” she said.

Louisiana is one of the least vaccinated states in the country. In the United States as a whole, 48.6% of the population is fully vaccinated. In Louisiana, it’s just 36%, and Delta is bearing down.

Dr. O’Neal spoke about the pressure that rising COVID cases were already putting on her hospital, Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge. She talked about watching her peers, 30- and 40-year-olds, become severely ill with the latest iteration of the new coronavirus — the Delta variant — which is sweeping through the United States with astonishing speed, causing new cases, hospitalizations, and deaths to rise again.

Dr. O’Neal talked about parents who might not be alive to see their children go off to college in a few weeks. She talked about increasing hospital admissions for infected kids and pregnant women on ventilators.

“I want to be clear after seeing what we’ve seen the last two weeks. We only have two choices: We are either going to get vaccinated and end the pandemic, or we’re going to accept death and a lot of it,” Dr. O’Neal said, her voice choked by emotion.

Where Delta goes, death follows

Delta was first identified in India, where it caused a devastating surge in the spring. In a population that was largely unvaccinated, researchers think it may have caused as many as three million deaths. In just a few months’ time, it has sped across the globe.

, which was first identified in the United Kingdom).

Where a single infected person might have spread older versions of the virus to two or three others, mathematician and epidemiologist Adam Kucharski, PhD, an associate professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, thinks that number — called the basic reproduction number — might be around six for Delta, meaning that, on average, each infected person spreads the virus to six others.

“The Delta variant is the most able and fastest and fittest of those viruses,” said Mike Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization’s Health Emergencies Programme, in a recent press briefing.

Early evidence suggests it may also cause more severe disease in people who are not vaccinated.

“There’s clearly increased risk of ICU admission, hospitalization, and death,” said Ashleigh Tuite, PhD, MPH, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Toronto in Ontario.

In a study published ahead of peer review, Dr. Tuite and her coauthor, David Fisman, MD, MPH, reviewed the health outcomes for more than 200,000 people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Ontario between February and June of 2021. Starting in February, Ontario began screening all positive COVID tests for mutations in the N501Y region for signs of mutation.

Compared with versions of the coronavirus that circulated in 2020, having an Alpha, Beta, or Gamma variant modestly increased the odds that an infected person would become sicker. The Delta variant raised the risk even higher, more than doubling the odds that an infected person would need to be hospitalized or could die from their infection.

Emerging evidence from England and Scotland, analyzed by Public Health England, also shows an increased risk for hospitalization with Delta. The increases are in line with the Canadian data. Experts caution that the picture may change over time as more evidence is gathered.

“What is causing that? We don’t know,” Dr. Tuite said.

Enhanced virus

The Delta variants (there’s actually more than one in the same viral family) have about 15 different mutations compared with the original virus. Two of these, L452R and E484Q, are mutations to the spike protein that were first flagged as problematic in other variants because they appear to help the virus escape the antibodies we make to fight it.

It has another mutation away from its binding site that’s also getting researchers’ attention — P681R.

This mutation appears to enhance the “springiness” of the parts of the virus that dock onto our cells, said Alexander Greninger, MD, PhD, assistant director of the UW Medicine Clinical Virology Laboratory at the University of Washington in Seattle. So it’s more likely to be in the right position to infect our cells if we come into contact with it.

Another theory is that P681R may also enhance the virus’s ability to fuse cells together into clumps that have several different nuclei. These balls of fused cells are called syncytia.

“So it turns into a big factory for making viruses,” said Kamran Kadkhoda, PhD, medical director of immunopathology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

This capability is not unique to Delta or even to the new coronavirus. Earlier versions and other viruses can do the same thing, but according to a recent paper in Nature, the syncytia that Delta creates are larger than the ones created by previous variants.

Scientists aren’t sure what these supersized syncytia mean, exactly, but they have some theories. They may help the virus copy itself more quickly, so a person’s viral load builds up quickly. That may enhance the ability of the virus to transmit from person to person.

And at least one recent study from China supports this idea. That study, which was posted ahead of peer review on the website Virological.org, tracked 167 people infected with Delta back to a single index case.

China has used extensive contact tracing to identify people that may have been exposed to the virus and sequester them quickly to tamp down its spread. Once a person is isolated or quarantined, they are tested daily with gold-standard PCR testing to determine whether or not they were infected.

Researchers compared the characteristics of Delta cases with those of people infected in 2020 with previous versions of the virus.

This study found that people infected by Delta tested positive more quickly than their predecessors did. In 2020, it took an average of 6 days for someone to test positive after an exposure. With Delta, it took an average of about 4 days.

When people tested positive, they had more than 1,000 times more virus in their bodies, suggesting that the Delta variant has a higher growth rate in the body.

This gives Delta a big advantage. According to Angie Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, who posted a thread about the study on Twitter, if people are shedding 1,000 times more virus, it is much more likely that close contacts will be exposed to enough of it to become infected themselves.

And if they’re shedding earlier in the course of their infections, the virus has more opportunity to spread.

This may help explain why Delta is so much more contagious.

Beyond transmission, Delta’s ability to form syncytia may have two other important consequences. It may help the virus hide from our immune system, and it may make the virus more damaging to the body.

Commonly, when a virus infects a cell, it will corrupt the cell’s protein-making machinery to crank out more copies of itself. When the cell dies, these new copies are released into the plasma outside the cell where they can float over and infect new cells. It’s in this extracellular space where a virus can also be attacked by the neutralizing antibodies our immune system makes to fight it off.

“Antibodies don’t penetrate inside the cell. If these viruses are going from one cell to another by just fusing to each other, antibodies become less useful,” Dr. Kadkhoda said.

Escape artist

Recent studies show that Delta is also able to escape antibodies made in response to vaccination more effectively than the Alpha, or B.1.1.7 strain. The effect was more pronounced in older adults, who tend to have weaker responses to vaccines in general.

This evasion of the immune system is particularly problematic for people who are only partially vaccinated. Data from the United Kingdom show that a single dose of vaccine is only about 31% effective at preventing illness with Delta, and 75% effective at preventing hospitalization.

After two doses, the vaccines are still highly effective — even against Delta — reaching 80% protection for illness, and 94% for hospitalization, which is why U.S. officials are begging people to get both doses of their shots, and do it as quickly as possible.

Finally, the virus’s ability to form syncytia may leave greater damage behind in the body’s tissues and organs.

“Especially in the lungs,” Dr. Kadkhoda said. The lungs are very fragile tissues. Their tiny air sacs — the alveoli — are only a single-cell thick. They have to be very thin to exchange oxygen in the blood.

“Any damage like that can severely affect any oxygen exchange and the normal housekeeping activities of that tissue,” he said. “In those vital organs, it may be very problematic.”

The research is still early, but studies in animals and cell lines are backing up what doctors say they are seeing in hospitalized patients.

A recent preprint study from researchers in Japan found that hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight — a proxy for how sick they were — compared with hamsters infected with an older version of the virus. The researchers attribute this to the viruses› ability to fuse cells together to form syncytia.

Another investigation, from researchers in India, infected two groups of hamsters — one with the original “wild type” strain of the virus, the other with the Delta variant of the new coronavirus.

As in the Japanese study, the hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight. When the researchers performed necropsies on the animals, they found more lung damage and bleeding in hamsters infected with Delta. This study was also posted as a preprint ahead of peer review.

German researchers working with pseudotyped versions of the new coronavirus — viruses that have been genetically changed to make them safer to work with — watched what happened after they used these pseudoviruses to infect lung, colon, and kidney cells in the lab.

They, too, found that cells infected with the Delta variant formed more and larger syncytia compared with cells infected with the wild type strain of the virus. The authors write that their findings suggest Delta could “cause more tissue damage, and thus be more pathogenic, than previous variants.”Researchers say it’s important to remember that, while interesting, this research isn’t conclusive. Hamsters and cells aren’t humans. More studies are needed to prove these theories.

Scientists say that what we already know about Delta makes vaccination more important than ever.

“The net effect is really that, you know, this is worrisome in people who are unvaccinated and then people who have breakthrough infections, but it’s not…a reason to panic or to throw up our hands and say you know, this pandemic is never going to end,” Dr. Tuite said, “[b]ecause what we do see is that the vaccines continue to be highly protective.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA set to okay Pfizer vaccine in younger teens

The Food and Drug Administration could expand the use of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine to teens early next week, The New York Times and CNN reported, both citing unnamed officials familiar with the agency’s plans.

In late March, Pfizer submitted data to the FDA showing its mRNA vaccine was 100% effective at preventing COVID-19 infection in children ages 12 to 15. Their vaccine is already authorized for use teens and adults ages 16 and older.

The move would make about 17 million more Americans eligible for vaccination and would be a major step toward getting both adolescents and teens back into classrooms full time by next fall.

“Across the globe, we are longing for a normal life. This is especially true for our children. The initial results we have seen in the adolescent studies suggest that children are particularly well protected by vaccination, which is very encouraging given the trends we have seen in recent weeks regarding the spread of the B.1.1.7 U.K. variant,” Ugur Sahin, CEO and co-founder of Pfizer partner BioNTech, said in a March 31 press release.

Getting schools fully reopened for in-person learning has been a goal of both the Trump and Biden administrations, but it has been tricky to pull off, as some parents and teachers have been reluctant to return to classrooms with so much uncertainty about the risk and the role of children in spreading the virus.

A recent study of roughly 150,000 school-aged children in Israel found that while kids under age 10 were unlikely to catch or spread the virus as they reentered classrooms. Older children, though, were a different story. The study found that children ages 10-19 had risks of catching the virus that were as high as adults ages 20-60.

The risk for severe illness and death from COVID-19 rises with age.

Children and teens are at relatively low risk from severe outcomes after a COVID-19 infection compared to adults, but they can catch it and some will get really sick with it, especially if they have an underlying health condition, like obesity or asthma that makes them more vulnerable.

Beyond the initial infection, children can get a rare late complication called MIS-C, that while treatable, can be severe and requires hospitalization. Emerging reports also suggest there are some kids that become long haulers in much the same way adults do, dealing with lingering problems for months after they first get sick.

As new variants of the coronavirus circulate in the United States, some states have seen big increases in the number of children and teens with COVID. In Michigan, for example, which recently dealt with a spring surge of cases dominated by the B.1.1.7 variant, cases in children and teens quadrupled in April compared to February.

Beyond individual protection, vaccinating children and teens has been seen as important to achieving strong community protection, or herd immunity, against the new coronavirus.

If the FDA expands the authorization for the Pfizer vaccine, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will likely meet to review data on the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. The committee may then vote on new recommendations for use of the vaccine in the United States.

Not everyone agrees with the idea that American adolescents, who are at relatively low risk of bad outcomes, could get access to COVID vaccines ahead of vulnerable essential workers and seniors in other parts of the world that are still fighting the pandemic with little access to vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Food and Drug Administration could expand the use of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine to teens early next week, The New York Times and CNN reported, both citing unnamed officials familiar with the agency’s plans.

In late March, Pfizer submitted data to the FDA showing its mRNA vaccine was 100% effective at preventing COVID-19 infection in children ages 12 to 15. Their vaccine is already authorized for use teens and adults ages 16 and older.

The move would make about 17 million more Americans eligible for vaccination and would be a major step toward getting both adolescents and teens back into classrooms full time by next fall.

“Across the globe, we are longing for a normal life. This is especially true for our children. The initial results we have seen in the adolescent studies suggest that children are particularly well protected by vaccination, which is very encouraging given the trends we have seen in recent weeks regarding the spread of the B.1.1.7 U.K. variant,” Ugur Sahin, CEO and co-founder of Pfizer partner BioNTech, said in a March 31 press release.

Getting schools fully reopened for in-person learning has been a goal of both the Trump and Biden administrations, but it has been tricky to pull off, as some parents and teachers have been reluctant to return to classrooms with so much uncertainty about the risk and the role of children in spreading the virus.

A recent study of roughly 150,000 school-aged children in Israel found that while kids under age 10 were unlikely to catch or spread the virus as they reentered classrooms. Older children, though, were a different story. The study found that children ages 10-19 had risks of catching the virus that were as high as adults ages 20-60.

The risk for severe illness and death from COVID-19 rises with age.

Children and teens are at relatively low risk from severe outcomes after a COVID-19 infection compared to adults, but they can catch it and some will get really sick with it, especially if they have an underlying health condition, like obesity or asthma that makes them more vulnerable.

Beyond the initial infection, children can get a rare late complication called MIS-C, that while treatable, can be severe and requires hospitalization. Emerging reports also suggest there are some kids that become long haulers in much the same way adults do, dealing with lingering problems for months after they first get sick.

As new variants of the coronavirus circulate in the United States, some states have seen big increases in the number of children and teens with COVID. In Michigan, for example, which recently dealt with a spring surge of cases dominated by the B.1.1.7 variant, cases in children and teens quadrupled in April compared to February.

Beyond individual protection, vaccinating children and teens has been seen as important to achieving strong community protection, or herd immunity, against the new coronavirus.

If the FDA expands the authorization for the Pfizer vaccine, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will likely meet to review data on the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. The committee may then vote on new recommendations for use of the vaccine in the United States.

Not everyone agrees with the idea that American adolescents, who are at relatively low risk of bad outcomes, could get access to COVID vaccines ahead of vulnerable essential workers and seniors in other parts of the world that are still fighting the pandemic with little access to vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Food and Drug Administration could expand the use of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine to teens early next week, The New York Times and CNN reported, both citing unnamed officials familiar with the agency’s plans.

In late March, Pfizer submitted data to the FDA showing its mRNA vaccine was 100% effective at preventing COVID-19 infection in children ages 12 to 15. Their vaccine is already authorized for use teens and adults ages 16 and older.

The move would make about 17 million more Americans eligible for vaccination and would be a major step toward getting both adolescents and teens back into classrooms full time by next fall.

“Across the globe, we are longing for a normal life. This is especially true for our children. The initial results we have seen in the adolescent studies suggest that children are particularly well protected by vaccination, which is very encouraging given the trends we have seen in recent weeks regarding the spread of the B.1.1.7 U.K. variant,” Ugur Sahin, CEO and co-founder of Pfizer partner BioNTech, said in a March 31 press release.

Getting schools fully reopened for in-person learning has been a goal of both the Trump and Biden administrations, but it has been tricky to pull off, as some parents and teachers have been reluctant to return to classrooms with so much uncertainty about the risk and the role of children in spreading the virus.

A recent study of roughly 150,000 school-aged children in Israel found that while kids under age 10 were unlikely to catch or spread the virus as they reentered classrooms. Older children, though, were a different story. The study found that children ages 10-19 had risks of catching the virus that were as high as adults ages 20-60.

The risk for severe illness and death from COVID-19 rises with age.

Children and teens are at relatively low risk from severe outcomes after a COVID-19 infection compared to adults, but they can catch it and some will get really sick with it, especially if they have an underlying health condition, like obesity or asthma that makes them more vulnerable.

Beyond the initial infection, children can get a rare late complication called MIS-C, that while treatable, can be severe and requires hospitalization. Emerging reports also suggest there are some kids that become long haulers in much the same way adults do, dealing with lingering problems for months after they first get sick.

As new variants of the coronavirus circulate in the United States, some states have seen big increases in the number of children and teens with COVID. In Michigan, for example, which recently dealt with a spring surge of cases dominated by the B.1.1.7 variant, cases in children and teens quadrupled in April compared to February.

Beyond individual protection, vaccinating children and teens has been seen as important to achieving strong community protection, or herd immunity, against the new coronavirus.

If the FDA expands the authorization for the Pfizer vaccine, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will likely meet to review data on the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. The committee may then vote on new recommendations for use of the vaccine in the United States.

Not everyone agrees with the idea that American adolescents, who are at relatively low risk of bad outcomes, could get access to COVID vaccines ahead of vulnerable essential workers and seniors in other parts of the world that are still fighting the pandemic with little access to vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

CDC: Vaccinated people can mostly drop masks outdoors

After hinting that new guidelines on outdoor mask-wearing were coming, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on April 27 officially gave a green light to fully vaccinated people gathering outside in uncrowded activities without the masks that have become so common during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is a minor – but still significant – step toward the end of pandemic restrictions.

“Over the past year, we have spent a lot of time telling Americans what they cannot do, what they should not do,” CDC director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said at a White House press briefing. “Today, I’m going to tell you some of the things you can do if you are fully vaccinated.”

President Joe Biden affirmed the new guidelines at a press conference soon after the CDC briefing ended.

,” he said, adding “the bottom line is clear: If you’re vaccinated, you can do more things, more safely, both outdoors as well as indoors.”

President Biden emphasized the role science played in the decision, saying “The CDC is able to make this announcement because our scientists are convinced by the data that the odds of getting or giving the virus to others is very, very low if you’ve both been fully vaccinated and are out in the open air.”

President Biden also said these new guidelines should be an incentive for more people to get vaccinated. “This is another great reason to go get vaccinated now. Now,” he said.

The CDC has long advised that outdoor activities are safer than indoor activities.

“Most of transmission is happening indoors rather than outdoors. Less than 10% of documented transmissions in many studies have occurred outdoors,” said Dr. Walensky. “We also know there’s almost a 20-fold increased risk of transmission in the indoor setting, than the outdoor setting.”

Dr. Walensky said the lower risks outdoors, combined with growing vaccination coverage and falling COVID cases around the country, motivated the change.

The new guidelines come as the share of people in the United States who are vaccinated is growing. About 37% of all eligible Americans are fully vaccinated, according to the CDC. Nearly 54% have had at least one dose.

The new guidelines say unvaccinated people should continue to wear masks outdoors when gathering with others or dining at an outdoor restaurant.

And vaccinated people should continue to wear masks outdoors in crowded settings where social distancing might not always be possible, like a concert or sporting event. People are considered fully vaccinated when they are 2 weeks past their last shot

The CDC guidelines say people who live in the same house don’t need to wear masks if they’re exercising or hanging out together outdoors.

You also don’t need a mask if you’re attending a small, outdoor gathering with fully vaccinated family and friends, whether you’re vaccinated or not.

The new guidelines also say it’s OK for fully vaccinated people to take their masks off outdoors when gathering in a small group of vaccinated and unvaccinated people, but suggest that unvaccinated people should still wear a mask.

Reporter Marcia Frellick contributed to this report.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

After hinting that new guidelines on outdoor mask-wearing were coming, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on April 27 officially gave a green light to fully vaccinated people gathering outside in uncrowded activities without the masks that have become so common during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is a minor – but still significant – step toward the end of pandemic restrictions.

“Over the past year, we have spent a lot of time telling Americans what they cannot do, what they should not do,” CDC director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said at a White House press briefing. “Today, I’m going to tell you some of the things you can do if you are fully vaccinated.”

President Joe Biden affirmed the new guidelines at a press conference soon after the CDC briefing ended.

,” he said, adding “the bottom line is clear: If you’re vaccinated, you can do more things, more safely, both outdoors as well as indoors.”

President Biden emphasized the role science played in the decision, saying “The CDC is able to make this announcement because our scientists are convinced by the data that the odds of getting or giving the virus to others is very, very low if you’ve both been fully vaccinated and are out in the open air.”

President Biden also said these new guidelines should be an incentive for more people to get vaccinated. “This is another great reason to go get vaccinated now. Now,” he said.

The CDC has long advised that outdoor activities are safer than indoor activities.

“Most of transmission is happening indoors rather than outdoors. Less than 10% of documented transmissions in many studies have occurred outdoors,” said Dr. Walensky. “We also know there’s almost a 20-fold increased risk of transmission in the indoor setting, than the outdoor setting.”

Dr. Walensky said the lower risks outdoors, combined with growing vaccination coverage and falling COVID cases around the country, motivated the change.

The new guidelines come as the share of people in the United States who are vaccinated is growing. About 37% of all eligible Americans are fully vaccinated, according to the CDC. Nearly 54% have had at least one dose.

The new guidelines say unvaccinated people should continue to wear masks outdoors when gathering with others or dining at an outdoor restaurant.

And vaccinated people should continue to wear masks outdoors in crowded settings where social distancing might not always be possible, like a concert or sporting event. People are considered fully vaccinated when they are 2 weeks past their last shot

The CDC guidelines say people who live in the same house don’t need to wear masks if they’re exercising or hanging out together outdoors.

You also don’t need a mask if you’re attending a small, outdoor gathering with fully vaccinated family and friends, whether you’re vaccinated or not.

The new guidelines also say it’s OK for fully vaccinated people to take their masks off outdoors when gathering in a small group of vaccinated and unvaccinated people, but suggest that unvaccinated people should still wear a mask.

Reporter Marcia Frellick contributed to this report.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

After hinting that new guidelines on outdoor mask-wearing were coming, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on April 27 officially gave a green light to fully vaccinated people gathering outside in uncrowded activities without the masks that have become so common during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is a minor – but still significant – step toward the end of pandemic restrictions.

“Over the past year, we have spent a lot of time telling Americans what they cannot do, what they should not do,” CDC director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said at a White House press briefing. “Today, I’m going to tell you some of the things you can do if you are fully vaccinated.”

President Joe Biden affirmed the new guidelines at a press conference soon after the CDC briefing ended.

,” he said, adding “the bottom line is clear: If you’re vaccinated, you can do more things, more safely, both outdoors as well as indoors.”

President Biden emphasized the role science played in the decision, saying “The CDC is able to make this announcement because our scientists are convinced by the data that the odds of getting or giving the virus to others is very, very low if you’ve both been fully vaccinated and are out in the open air.”

President Biden also said these new guidelines should be an incentive for more people to get vaccinated. “This is another great reason to go get vaccinated now. Now,” he said.

The CDC has long advised that outdoor activities are safer than indoor activities.

“Most of transmission is happening indoors rather than outdoors. Less than 10% of documented transmissions in many studies have occurred outdoors,” said Dr. Walensky. “We also know there’s almost a 20-fold increased risk of transmission in the indoor setting, than the outdoor setting.”

Dr. Walensky said the lower risks outdoors, combined with growing vaccination coverage and falling COVID cases around the country, motivated the change.

The new guidelines come as the share of people in the United States who are vaccinated is growing. About 37% of all eligible Americans are fully vaccinated, according to the CDC. Nearly 54% have had at least one dose.

The new guidelines say unvaccinated people should continue to wear masks outdoors when gathering with others or dining at an outdoor restaurant.

And vaccinated people should continue to wear masks outdoors in crowded settings where social distancing might not always be possible, like a concert or sporting event. People are considered fully vaccinated when they are 2 weeks past their last shot

The CDC guidelines say people who live in the same house don’t need to wear masks if they’re exercising or hanging out together outdoors.

You also don’t need a mask if you’re attending a small, outdoor gathering with fully vaccinated family and friends, whether you’re vaccinated or not.

The new guidelines also say it’s OK for fully vaccinated people to take their masks off outdoors when gathering in a small group of vaccinated and unvaccinated people, but suggest that unvaccinated people should still wear a mask.

Reporter Marcia Frellick contributed to this report.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Feds lift pause of J&J COVID vaccine, add new warning

Use of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine should resume in the United States for all adults, the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Contol and Prevention said April 23, although health care providers should warn patients of the risk of developing the rare and serious blood clots that caused the agencies to pause the vaccine’s distribution earlier this month.

“What we are seeing is the overall rate of events was 1.9 cases per million people. In women 18 to 29 years there was an approximate 7 cases per million. The risk is even lower in women over the age of 50 at .9 cases per million,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said in a news briefing the same day.