User login

Management of Isolated Greater Tuberosity Fractures: A Systematic Review

Take-Home Points

- Fractures of the greater tuberosity are often mismanaged.

- Comprehension of greater tuberosity fractures involves classification into nonoperative and operative treatment, displacement >5mm or <5 mm, and open vs arthroscopic surgery.

- Nearly a third of patients may suffer concomitant anterior glenohumeral instability.

- Stiffness is the most common postoperative complication.

- Surgery is associated with high patient satisfaction and low rates of complications and reoperations.

Although proximal humerus fractures are common in the elderly, isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity occur less often. Management depends on several factors, including fracture pattern and displacement.1,2 Nondisplaced fractures are often successfully managed with sling immobilization and early range of motion.3,4 Although surgical intervention improves outcomes in displaced greater tuberosity fractures, the ideal surgical treatment is less clear.5

Displaced greater tuberosity fractures may require surgery for prevention of subacromial impingement and range-of-motion deficits.2 Superior fracture displacement results in decreased shoulder abduction, and posterior displacement can limit external rotation.6 Although the greater tuberosity can displace in any direction, posterosuperior displacement has the worst outcomes.1 The exact surgery-warranting displacement amount ranges from 3 mm to 10 mm but is yet to be clearly elucidated.5,6 Less displacement is tolerated by young overhead athletes, and more displacement by older less active patients.5,7,8 Surgical options for isolated greater tuberosity fractures include fragment excision, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), closed reduction with percutaneous fixation, and arthroscopically assisted reduction with internal fixation.3,9,10

We conducted a study to determine the management patterns for isolated greater tuberosity fractures. We hypothesized that greater tuberosity fractures displaced <5 mm may be managed nonoperatively and that greater tuberosity fractures displaced >5 mm require surgical fixation.

Methods

Search Strategy

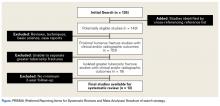

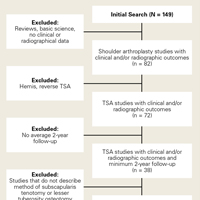

We performed this systematic review according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist11 and registered it (CRD42014010691) with the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews. Literature searches using the PubMed/Medline database and the Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials were completed in August 2014. There were no date or year restrictions. Key words were used to capture all English- language studies with level I to IV evidence (Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine) and reported clinical or radiographic outcomes. Initial exclusion criteria were cadaveric, biomechanical, histologic, and kinematic results. An electronic search algorithm with key words and a series of NOT phrases was designed to match our exclusion criteria:

((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((greater[Title/Abstract]) AND tuberosity [Title/Abstract] OR tubercle [Title/Abstract]) AND fracture[Title/Abstract]) AND proximal[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT intramedullary[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT nonunion[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT malunion[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT biomechanical[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT cadaveric[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT cadaver[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT ((basic[Title/Abstract]) AND science[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang])) AND (English[lang]))) NOT revision[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT pediatric[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT physeal[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT children[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT instability[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT imaging[Title])) NOT salter[Title])) NOT physis[Title])) NOT shaft[Title])) NOT distal[Title])) NOT clavicle[Title])) NOT scapula[Title])) NOT ((diaphysis[Title]) AND diaphyseal[Title]))) NOT infection[Title])) NOT laboratory[Title/Abstract])) NOT metastatic[Title/Abstract])) NOT (((((((malignancy[Title/Abstract]) OR malignant[Title/Abstract]) OR tumor[Title/Abstract]) OR oncologic[Title/Abstract]) OR cyst[Title/Abstract]) OR aneurysmal[Title/Abstract]) OR unicameral[Title/Abstract]).

Study Selection

Data Extraction

We extracted data from the 13 studies that met the eligibility criteria. Details of study design, sample size, and patient demographics, including age, sex, and hand dominance, were recorded, as were mechanism of injury and concomitant anterior shoulder instability. To capture the most patients, we noted radiographic fracture displacement categorically rather than continuously; patients were divided into 2 displacement groups (<5 mm, >5 mm). Most studies did not define degree of comminution or specific direction of displacement per fracture, so these variables were not included in the data analysis. Nonoperative management and operative management were studied. We abstracted surgical factors, such as approach, method, fixation type (screws or sutures), and technique (suture anchors or transosseous tunnels). Clinical outcomes included physical examination findings, functional assessment results (patient satisfaction; Constant and University of California Los Angeles [UCLA] shoulder scores), and the number of revisions. Radiologic outcomes, retrieved from radiographs or computed tomography scans, focused on loss of reduction (as determined by the respective authors), malunion, nonunion, and heterotopic ossification. Each study’s methodologic quality and bias were evaluated with the 15-item Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS), which was described by Cowan and colleagues.23 The MCMS has been used to assess randomized and nonrandomized patient trials.24,25 Its scaled potential score ranges from 0 to 100 (85-100, excellent; 70-84, good; 55-69, fair; <55, poor).

Statistical Analysis

We report our data as weighted means (SDs). A mean was calculated for each study that reported a respective data point, and each mean was then weighed according to its study sample size. This calculation was performed by multiplying a study’s individual mean by the number of patients enrolled in that study and dividing the sum of these weighted data points by the number of eligible patients in all relevant studies. The result was that the nonweighted means from studies with smaller sample sizes did not carry as much weight as the nonweighted means from larger studies. We compared 3 paired groups: treatment type (nonoperative vs operative), fracture displacement amount (<5 mm vs >5 mm), and surgery type (open vs arthroscopic). Regarding all patient, surgery, and outcomes data, unpaired Student t tests were used for continuous variables and 2-tailed Fisher exact tests for categorical variables with α = 0.05 (SPSS Version 18; IBM).

Results

Postoperative physical examination findings were underreported so that surgical groups could be compared. Of all the surgical studies, 4 reported postoperative forward elevation (mean, 160°; SD, 9.8°) and external rotation (mean, 46.4°; SD 26.3°).14,15,18,22 No malunions and only 1 nonunion were reported in all 13 studies. No deaths or other serious medical complications were reported. Patients with anterior instability more often underwent surgery than were treated nonoperatively (39.2% vs 12.0%; P < .01) and more often had fractures displaced >5 mm than <5 mm (44.3% vs 14.5%; P < .01).

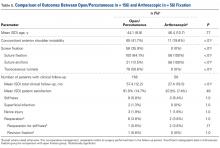

Fisher exact tests were used to perform isolated comparisons of screws and sutures as well as suture anchors and transosseous tunnels. Patients with screw fixation were significantly (P = .051) less likely to require reoperation (0/56; 0%) than patients with suture fixation (8/100; 8.0%). Screw fixation also led to significantly less stiffness (0% vs 12.0%; P < .01) but trended toward a higher rate of superficial infection (3.6% vs 0%; P = .13). There was no statistical difference in nerve injury rates between screws and sutures (1.8% vs 3.0%; P = 1.0). There were no significant differences in reoperations, stiffness, superficial infections, or nerve injuries between suture anchor and transosseous tunnel constructs.

For all 13 studies, mean (SD) MCMS was 41.1 (8.6).

Discussion

Five percent of all fractures involve the proximal humerus, and 20% of proximal humerus fractures are isolated greater tuberosity fractures.26,27 In his classic 1970 article, Neer6 formulated the 4-part proximal humerus fracture classification and defined greater tuberosity fracture “parts” using the same criteria as for other fracture “parts.” Neer6 recommended nonoperative management for isolated greater tuberosity fractures displaced <1 cm but did not present evidence corroborating his recommendation. More recent cutoffs for nonoperative management include 5 mm (general population) and 3 mm (athletes).7,17

In the present systematic review of greater tuberosity fractures, 3 separate comparisons were made: treatment type (nonoperative vs operative), fracture displacement amount (<5 mm vs >5 mm), and surgery type (open vs arthroscopic).

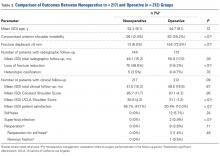

Treatment Type. Only 4 studies reported data on nonoperative treatment outcomes.5,12,16,17 Of these 4 studies, 2 found successful outcomes for fractures displaced <5 mm.12,17 Platzer and colleagues17 found good or excellent results in 97% of 135 shoulders after 4 years. Good results were defined with shoulder scores of ≥80 (Constant), <8 (Vienna), and >28 (UCLA), and excellent results were defined with maximum scores on 2 of the 3 systems. Platzer and colleagues17 also found nonsignificantly worse shoulder scores with superior displacement of 3 mm to 5 mm and recommended surgery for overhead athletes in this group. Rath and colleagues12 described a successful 3-phase rehabilitation protocol of sling immobilization for 3 weeks, pendulum exercises for 3 weeks, and active exercises thereafter. By an average of 31 months, patient satisfaction scores improved to 9.5 from 4.2 (10-point scale), though the authors cautioned that pain and decreased motion lasted 8 months on average. Conservative treatment was far less successful in the 2 studies of fractures displaced >5 mm.5,16 Keene and colleagues16 reported unsatisfactory results in all 4 patients with fractures displaced >1.5 cm. In a study separate from their 2005 analysis,17 Platzer and colleagues5 in 2008 evaluated displaced fractures and found function and patient satisfaction were inferior after nonoperative treatment than after surgery. The studies by Keene and colleagues16 and Platzer and colleagues5 support the finding of an overall lower patient satisfaction rate in nonoperative patients.

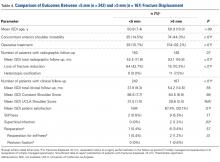

Fracture Displacement Amount. Only 2 arthroscopic studies and no open studies addressed surgery for fractures displaced <5 mm. Fewer than 16% of these fractures were managed operatively, and <1% required reoperation. By contrast, almost all fractures displaced >5 mm were managed operatively, and 3.6% required reoperation. Radiographic loss of reduction was more common in fractures displaced <5 mm, primarily because they were managed without fixation. Radiographic loss of reduction was reported in only 9 operatively treated patients, none of whom was symptomatic enough to require another surgery.5 Reoperations were most commonly performed for stiffness, which itself was significantly more common in fractures displaced >5 mm. Bhatia and colleagues14 reported the highest reoperation rate (14.3%; 3/21), but they studied more complex, comminuted fractures of the greater tuberosity. Two of their 3 reoperations were biceps tenodeses for inflamed, stiff tenosynovitis, and the third patient had a foreign body giant cell reaction to suture material. Fewer than 1% of patients with operatively managed displaced fractures required revision ORIF, and <2% developed a superficial infection or postoperative nerve palsy.19,22 For displaced greater tuberosity fractures, surgery is highly successful overall, complication rates are very low, and 90% of patients report being satisfied.

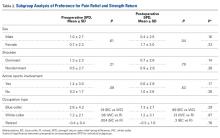

Surgery Type. Patients were divided into 2 groups. In the nonarthroscopic group, open and percutaneous approaches were used. All studies that described a percutaneous approach used screw fixation5,21; in addition, 32 patients were treated with screws through an open approach.2,5 The other open and arthroscopic studies used suture fixation. Interestingly, no studies reported on clinical outcomes of fragment excision. There were no statistically significant differences in rates of reoperation, stiffness, infection, or neurologic injury between the arthroscopic and nonarthroscopic groups. Patient satisfaction scores were slightly higher in the nonarthroscopic group (91.0% vs 87.8%), but the difference was not statistically significant.

With surgical techniques isolated, there were no significant differences between suture anchors and transosseous tunnel constructs, but screws performed significantly better than suture techniques. Compared with suture fixation, screw fixation led to significantly fewer cases of stiffness and reoperation, which suggests surgeons need to give screws more consideration in the operative management of these fractures. However, the number of patients treated with screws was smaller than the number treated with suture fixation; it is possible the differences between these cohorts would be eliminated if there were more patients in the screw cohort. In addition, screw fixation was universally performed with an open or percutaneous approach and trended toward a higher infection rate. As screw and suture techniques have low rates of complications and reoperations, we recommend leaving fixation choice to the surgeon.

Anterior shoulder instability has been associated with greater tuberosity fractures.1,8,19 The supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles all insert into the greater tuberosity and resist anterior translation of the proximal humerus. Loss of this dynamic muscle stabilization is amplified by tuberosity fracture displacement: Anterior shoulder instability was significantly more common in fractures displaced >5 mm (44.3%) vs <5 mm (14.5%). In turn, glenohumeral instability was more common in patients treated with surgery, specifically open surgery, because displaced fractures may not be as easily accessed with arthroscopic techniques. No studies reported concomitant labral repair or capsular plication techniques.

This systematic review was limited by the studies analyzed. All but 1 study5 had level IV evidence. Mean (SD) MCMS was 41.8 (8.6). Any MCMS score <54 indicates a poor methodology level, but this scoring system is designed for randomized controlled trials,23 and there were none in this study. Physical examination findings, such as range of motion, were underreported. In addition, radiographic parameters were not consistently described but rather were determined by the respective authors’ subjective interpretations of malunion, nonunion, and loss of reduction. Publication bias is present in that we excluded non- English language studies and medical conference abstracts and may have omitted potentially eligible studies not discoverable with our search methodology. Performance bias is a factor in any systematic review with multiple surgeons and wide variation in surgical technique.

Conclusion

Greater tuberosity fractures displaced <5 mm may be safely managed nonoperatively, as there are no reports of nonoperatively managed fractures that subsequently required surgery. Nonoperative treatment was initially associated with low patient satisfaction, but only because displaced fractures were conservatively managed in early studies.5,16 Fractures displaced >5 mm respond well to operative fixation with screws, suture anchors, or transosseous suture tunnels. Stiffness is the most common postoperative complication (<6%), followed by heterotopic ossification, transient neurapraxias, and superficial infection. There are no discernible differences in outcome between open and arthroscopic techniques, but screw fixation may lead to significantly fewer cases of stiffness and reoperation in comparison with suture constructs.

1. Verdano MA, Aliani D, Pellegrini A, Baudi P, Pedrazzi G, Ceccarelli F. Isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity in proximal humerus: does the direction of displacement influence functional outcome? An analysis of displacement in greater tuberosity fractures. Acta Biomed. 2013;84(3):219-228.

2. Yin B, Moen TC, Thompson SA, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Operative treatment of isolated greater tuberosity fractures: retrospective review of clinical and functional outcomes. Orthopedics. 2012;35(6):e807-e814.

3. Green A, Izzi J. Isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(6):641-649.

4. Norouzi M, Naderi MN, Komasi MH, Sharifzadeh SR, Shahrezaei M, Eajazi A. Clinical results of using the proximal humeral internal locking system plate for internal fixation of displaced proximal humeral fractures. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(5):E64-E68.

5. Platzer P, Thalhammer G, Oberleitner G, et al. Displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity: a comparison of operative and nonoperative treatment. J Trauma. 2008;65(4):843-848.

6. Neer CS. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52(6):1077-1089.

7. Park TS, Choi IY, Kim YH, Park MR, Shon JH, Kim SI. A new suggestion for the treatment of minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1997;56(3):171-176.

8. McLaughlin HL. Dislocation of the shoulder with tuberosity fracture. Surg Clin North Am. 1963;43:1615-1620.

9. DeBottis D, Anavian J, Green A. Surgical management of isolated greater tuberosity fractures of the proximal humerus. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(2):207-218.

10. Monga P, Verma R, Sharma VK. Closed reduction and external fixation for displaced proximal humeral fractures. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2009;17(2):142-145.

11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006-1012.

12. Rath E, Alkrinawi N, Levy O, Debbi R, Amar E, Atoun E. Minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity: outcome of non-operative treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(10):e8-e11.

13. Dimakopoulos P, Panagopoulos A, Kasimatis G. Transosseous suture fixation of proximal humeral fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1700-1709.

14. Bhatia DN, van Rooyen KS, Toit du DF, de Beer JF. Surgical treatment of comminuted, displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus: a new technique of double-row suture-anchor fixation and long-term results. Injury. 2006;37(10):946-952.

15. Flatow EL, Cuomo F, Maday MG, Miller SR, McIlveen SJ, Bigliani LU. Open reduction and internal fixation of two-part displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal part of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(8):1213-1218.

16. Keene JS, Huizenga RE, Engber WD, Rogers SC. Proximal humeral fractures: a correlation of residual deformity with long-term function. Orthopedics. 1983;6(2):173-178.

17. Platzer P, Kutscha-Lissberg F, Lehr S, Vecsei V, Gaebler C. The influence of displacement on shoulder function in patients with minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity. Injury. 2005;36(10):1185-1189.

18. Park SE, Ji JH, Shafi M, Jung JJ, Gil HJ, Lee HH. Arthroscopic management of occult greater tuberosity fracture of the shoulder. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(4):475-482.

19. Dimakopoulos P, Panagopoulos A, Kasimatis G, Syggelos SA, Lambiris E. Anterior traumatic shoulder dislocation associated with displaced greater tuberosity fracture: the necessity of operative treatment. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(2):104-112.

20. Kim SH, Ha KI. Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic shoulders with minimally displaced greater tuberosity fracture. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(7):695-700.

21. Chen CY, Chao EK, Tu YK, Ueng SW, Shih CH. Closed management and percutaneous fixation of unstable proximal humerus fractures. J Trauma. 1998;45(6):1039-1045.

22. Ji JH, Shafi M, Song IS, Kim YY, McFarland EG, Moon CY. Arthroscopic fixation technique for comminuted, displaced greater tuberosity fracture. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(5):600-609.

23. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderón S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

24. Harris JD, Siston RA, Pan X, Flanigan DC. Autologous chondrocyte implantation: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(12):2220-2233.

25. Harris JD, Siston RA, Brophy RH, Lattermann C, Carey JL, Flanigan DC. Failures, re-operations, and complications after autologous chondrocyte implantation—a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(7):779-791.

26. Chun JM, Groh GI, Rockwood CA. Two-part fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3(5):273-287.

27. Gruson KI, Ruchelsman DE, Tejwani NC. Isolated tuberosity fractures of the proximal humeral: current concepts. Injury. 2008;39(3):284-298.

Take-Home Points

- Fractures of the greater tuberosity are often mismanaged.

- Comprehension of greater tuberosity fractures involves classification into nonoperative and operative treatment, displacement >5mm or <5 mm, and open vs arthroscopic surgery.

- Nearly a third of patients may suffer concomitant anterior glenohumeral instability.

- Stiffness is the most common postoperative complication.

- Surgery is associated with high patient satisfaction and low rates of complications and reoperations.

Although proximal humerus fractures are common in the elderly, isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity occur less often. Management depends on several factors, including fracture pattern and displacement.1,2 Nondisplaced fractures are often successfully managed with sling immobilization and early range of motion.3,4 Although surgical intervention improves outcomes in displaced greater tuberosity fractures, the ideal surgical treatment is less clear.5

Displaced greater tuberosity fractures may require surgery for prevention of subacromial impingement and range-of-motion deficits.2 Superior fracture displacement results in decreased shoulder abduction, and posterior displacement can limit external rotation.6 Although the greater tuberosity can displace in any direction, posterosuperior displacement has the worst outcomes.1 The exact surgery-warranting displacement amount ranges from 3 mm to 10 mm but is yet to be clearly elucidated.5,6 Less displacement is tolerated by young overhead athletes, and more displacement by older less active patients.5,7,8 Surgical options for isolated greater tuberosity fractures include fragment excision, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), closed reduction with percutaneous fixation, and arthroscopically assisted reduction with internal fixation.3,9,10

We conducted a study to determine the management patterns for isolated greater tuberosity fractures. We hypothesized that greater tuberosity fractures displaced <5 mm may be managed nonoperatively and that greater tuberosity fractures displaced >5 mm require surgical fixation.

Methods

Search Strategy

We performed this systematic review according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist11 and registered it (CRD42014010691) with the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews. Literature searches using the PubMed/Medline database and the Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials were completed in August 2014. There were no date or year restrictions. Key words were used to capture all English- language studies with level I to IV evidence (Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine) and reported clinical or radiographic outcomes. Initial exclusion criteria were cadaveric, biomechanical, histologic, and kinematic results. An electronic search algorithm with key words and a series of NOT phrases was designed to match our exclusion criteria:

((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((greater[Title/Abstract]) AND tuberosity [Title/Abstract] OR tubercle [Title/Abstract]) AND fracture[Title/Abstract]) AND proximal[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT intramedullary[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT nonunion[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT malunion[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT biomechanical[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT cadaveric[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT cadaver[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT ((basic[Title/Abstract]) AND science[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang])) AND (English[lang]))) NOT revision[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT pediatric[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT physeal[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT children[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT instability[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT imaging[Title])) NOT salter[Title])) NOT physis[Title])) NOT shaft[Title])) NOT distal[Title])) NOT clavicle[Title])) NOT scapula[Title])) NOT ((diaphysis[Title]) AND diaphyseal[Title]))) NOT infection[Title])) NOT laboratory[Title/Abstract])) NOT metastatic[Title/Abstract])) NOT (((((((malignancy[Title/Abstract]) OR malignant[Title/Abstract]) OR tumor[Title/Abstract]) OR oncologic[Title/Abstract]) OR cyst[Title/Abstract]) OR aneurysmal[Title/Abstract]) OR unicameral[Title/Abstract]).

Study Selection

Data Extraction

We extracted data from the 13 studies that met the eligibility criteria. Details of study design, sample size, and patient demographics, including age, sex, and hand dominance, were recorded, as were mechanism of injury and concomitant anterior shoulder instability. To capture the most patients, we noted radiographic fracture displacement categorically rather than continuously; patients were divided into 2 displacement groups (<5 mm, >5 mm). Most studies did not define degree of comminution or specific direction of displacement per fracture, so these variables were not included in the data analysis. Nonoperative management and operative management were studied. We abstracted surgical factors, such as approach, method, fixation type (screws or sutures), and technique (suture anchors or transosseous tunnels). Clinical outcomes included physical examination findings, functional assessment results (patient satisfaction; Constant and University of California Los Angeles [UCLA] shoulder scores), and the number of revisions. Radiologic outcomes, retrieved from radiographs or computed tomography scans, focused on loss of reduction (as determined by the respective authors), malunion, nonunion, and heterotopic ossification. Each study’s methodologic quality and bias were evaluated with the 15-item Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS), which was described by Cowan and colleagues.23 The MCMS has been used to assess randomized and nonrandomized patient trials.24,25 Its scaled potential score ranges from 0 to 100 (85-100, excellent; 70-84, good; 55-69, fair; <55, poor).

Statistical Analysis

We report our data as weighted means (SDs). A mean was calculated for each study that reported a respective data point, and each mean was then weighed according to its study sample size. This calculation was performed by multiplying a study’s individual mean by the number of patients enrolled in that study and dividing the sum of these weighted data points by the number of eligible patients in all relevant studies. The result was that the nonweighted means from studies with smaller sample sizes did not carry as much weight as the nonweighted means from larger studies. We compared 3 paired groups: treatment type (nonoperative vs operative), fracture displacement amount (<5 mm vs >5 mm), and surgery type (open vs arthroscopic). Regarding all patient, surgery, and outcomes data, unpaired Student t tests were used for continuous variables and 2-tailed Fisher exact tests for categorical variables with α = 0.05 (SPSS Version 18; IBM).

Results

Postoperative physical examination findings were underreported so that surgical groups could be compared. Of all the surgical studies, 4 reported postoperative forward elevation (mean, 160°; SD, 9.8°) and external rotation (mean, 46.4°; SD 26.3°).14,15,18,22 No malunions and only 1 nonunion were reported in all 13 studies. No deaths or other serious medical complications were reported. Patients with anterior instability more often underwent surgery than were treated nonoperatively (39.2% vs 12.0%; P < .01) and more often had fractures displaced >5 mm than <5 mm (44.3% vs 14.5%; P < .01).

Fisher exact tests were used to perform isolated comparisons of screws and sutures as well as suture anchors and transosseous tunnels. Patients with screw fixation were significantly (P = .051) less likely to require reoperation (0/56; 0%) than patients with suture fixation (8/100; 8.0%). Screw fixation also led to significantly less stiffness (0% vs 12.0%; P < .01) but trended toward a higher rate of superficial infection (3.6% vs 0%; P = .13). There was no statistical difference in nerve injury rates between screws and sutures (1.8% vs 3.0%; P = 1.0). There were no significant differences in reoperations, stiffness, superficial infections, or nerve injuries between suture anchor and transosseous tunnel constructs.

For all 13 studies, mean (SD) MCMS was 41.1 (8.6).

Discussion

Five percent of all fractures involve the proximal humerus, and 20% of proximal humerus fractures are isolated greater tuberosity fractures.26,27 In his classic 1970 article, Neer6 formulated the 4-part proximal humerus fracture classification and defined greater tuberosity fracture “parts” using the same criteria as for other fracture “parts.” Neer6 recommended nonoperative management for isolated greater tuberosity fractures displaced <1 cm but did not present evidence corroborating his recommendation. More recent cutoffs for nonoperative management include 5 mm (general population) and 3 mm (athletes).7,17

In the present systematic review of greater tuberosity fractures, 3 separate comparisons were made: treatment type (nonoperative vs operative), fracture displacement amount (<5 mm vs >5 mm), and surgery type (open vs arthroscopic).

Treatment Type. Only 4 studies reported data on nonoperative treatment outcomes.5,12,16,17 Of these 4 studies, 2 found successful outcomes for fractures displaced <5 mm.12,17 Platzer and colleagues17 found good or excellent results in 97% of 135 shoulders after 4 years. Good results were defined with shoulder scores of ≥80 (Constant), <8 (Vienna), and >28 (UCLA), and excellent results were defined with maximum scores on 2 of the 3 systems. Platzer and colleagues17 also found nonsignificantly worse shoulder scores with superior displacement of 3 mm to 5 mm and recommended surgery for overhead athletes in this group. Rath and colleagues12 described a successful 3-phase rehabilitation protocol of sling immobilization for 3 weeks, pendulum exercises for 3 weeks, and active exercises thereafter. By an average of 31 months, patient satisfaction scores improved to 9.5 from 4.2 (10-point scale), though the authors cautioned that pain and decreased motion lasted 8 months on average. Conservative treatment was far less successful in the 2 studies of fractures displaced >5 mm.5,16 Keene and colleagues16 reported unsatisfactory results in all 4 patients with fractures displaced >1.5 cm. In a study separate from their 2005 analysis,17 Platzer and colleagues5 in 2008 evaluated displaced fractures and found function and patient satisfaction were inferior after nonoperative treatment than after surgery. The studies by Keene and colleagues16 and Platzer and colleagues5 support the finding of an overall lower patient satisfaction rate in nonoperative patients.

Fracture Displacement Amount. Only 2 arthroscopic studies and no open studies addressed surgery for fractures displaced <5 mm. Fewer than 16% of these fractures were managed operatively, and <1% required reoperation. By contrast, almost all fractures displaced >5 mm were managed operatively, and 3.6% required reoperation. Radiographic loss of reduction was more common in fractures displaced <5 mm, primarily because they were managed without fixation. Radiographic loss of reduction was reported in only 9 operatively treated patients, none of whom was symptomatic enough to require another surgery.5 Reoperations were most commonly performed for stiffness, which itself was significantly more common in fractures displaced >5 mm. Bhatia and colleagues14 reported the highest reoperation rate (14.3%; 3/21), but they studied more complex, comminuted fractures of the greater tuberosity. Two of their 3 reoperations were biceps tenodeses for inflamed, stiff tenosynovitis, and the third patient had a foreign body giant cell reaction to suture material. Fewer than 1% of patients with operatively managed displaced fractures required revision ORIF, and <2% developed a superficial infection or postoperative nerve palsy.19,22 For displaced greater tuberosity fractures, surgery is highly successful overall, complication rates are very low, and 90% of patients report being satisfied.

Surgery Type. Patients were divided into 2 groups. In the nonarthroscopic group, open and percutaneous approaches were used. All studies that described a percutaneous approach used screw fixation5,21; in addition, 32 patients were treated with screws through an open approach.2,5 The other open and arthroscopic studies used suture fixation. Interestingly, no studies reported on clinical outcomes of fragment excision. There were no statistically significant differences in rates of reoperation, stiffness, infection, or neurologic injury between the arthroscopic and nonarthroscopic groups. Patient satisfaction scores were slightly higher in the nonarthroscopic group (91.0% vs 87.8%), but the difference was not statistically significant.

With surgical techniques isolated, there were no significant differences between suture anchors and transosseous tunnel constructs, but screws performed significantly better than suture techniques. Compared with suture fixation, screw fixation led to significantly fewer cases of stiffness and reoperation, which suggests surgeons need to give screws more consideration in the operative management of these fractures. However, the number of patients treated with screws was smaller than the number treated with suture fixation; it is possible the differences between these cohorts would be eliminated if there were more patients in the screw cohort. In addition, screw fixation was universally performed with an open or percutaneous approach and trended toward a higher infection rate. As screw and suture techniques have low rates of complications and reoperations, we recommend leaving fixation choice to the surgeon.

Anterior shoulder instability has been associated with greater tuberosity fractures.1,8,19 The supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles all insert into the greater tuberosity and resist anterior translation of the proximal humerus. Loss of this dynamic muscle stabilization is amplified by tuberosity fracture displacement: Anterior shoulder instability was significantly more common in fractures displaced >5 mm (44.3%) vs <5 mm (14.5%). In turn, glenohumeral instability was more common in patients treated with surgery, specifically open surgery, because displaced fractures may not be as easily accessed with arthroscopic techniques. No studies reported concomitant labral repair or capsular plication techniques.

This systematic review was limited by the studies analyzed. All but 1 study5 had level IV evidence. Mean (SD) MCMS was 41.8 (8.6). Any MCMS score <54 indicates a poor methodology level, but this scoring system is designed for randomized controlled trials,23 and there were none in this study. Physical examination findings, such as range of motion, were underreported. In addition, radiographic parameters were not consistently described but rather were determined by the respective authors’ subjective interpretations of malunion, nonunion, and loss of reduction. Publication bias is present in that we excluded non- English language studies and medical conference abstracts and may have omitted potentially eligible studies not discoverable with our search methodology. Performance bias is a factor in any systematic review with multiple surgeons and wide variation in surgical technique.

Conclusion

Greater tuberosity fractures displaced <5 mm may be safely managed nonoperatively, as there are no reports of nonoperatively managed fractures that subsequently required surgery. Nonoperative treatment was initially associated with low patient satisfaction, but only because displaced fractures were conservatively managed in early studies.5,16 Fractures displaced >5 mm respond well to operative fixation with screws, suture anchors, or transosseous suture tunnels. Stiffness is the most common postoperative complication (<6%), followed by heterotopic ossification, transient neurapraxias, and superficial infection. There are no discernible differences in outcome between open and arthroscopic techniques, but screw fixation may lead to significantly fewer cases of stiffness and reoperation in comparison with suture constructs.

Take-Home Points

- Fractures of the greater tuberosity are often mismanaged.

- Comprehension of greater tuberosity fractures involves classification into nonoperative and operative treatment, displacement >5mm or <5 mm, and open vs arthroscopic surgery.

- Nearly a third of patients may suffer concomitant anterior glenohumeral instability.

- Stiffness is the most common postoperative complication.

- Surgery is associated with high patient satisfaction and low rates of complications and reoperations.

Although proximal humerus fractures are common in the elderly, isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity occur less often. Management depends on several factors, including fracture pattern and displacement.1,2 Nondisplaced fractures are often successfully managed with sling immobilization and early range of motion.3,4 Although surgical intervention improves outcomes in displaced greater tuberosity fractures, the ideal surgical treatment is less clear.5

Displaced greater tuberosity fractures may require surgery for prevention of subacromial impingement and range-of-motion deficits.2 Superior fracture displacement results in decreased shoulder abduction, and posterior displacement can limit external rotation.6 Although the greater tuberosity can displace in any direction, posterosuperior displacement has the worst outcomes.1 The exact surgery-warranting displacement amount ranges from 3 mm to 10 mm but is yet to be clearly elucidated.5,6 Less displacement is tolerated by young overhead athletes, and more displacement by older less active patients.5,7,8 Surgical options for isolated greater tuberosity fractures include fragment excision, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), closed reduction with percutaneous fixation, and arthroscopically assisted reduction with internal fixation.3,9,10

We conducted a study to determine the management patterns for isolated greater tuberosity fractures. We hypothesized that greater tuberosity fractures displaced <5 mm may be managed nonoperatively and that greater tuberosity fractures displaced >5 mm require surgical fixation.

Methods

Search Strategy

We performed this systematic review according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist11 and registered it (CRD42014010691) with the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews. Literature searches using the PubMed/Medline database and the Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials were completed in August 2014. There were no date or year restrictions. Key words were used to capture all English- language studies with level I to IV evidence (Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine) and reported clinical or radiographic outcomes. Initial exclusion criteria were cadaveric, biomechanical, histologic, and kinematic results. An electronic search algorithm with key words and a series of NOT phrases was designed to match our exclusion criteria:

((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((greater[Title/Abstract]) AND tuberosity [Title/Abstract] OR tubercle [Title/Abstract]) AND fracture[Title/Abstract]) AND proximal[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT intramedullary[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT nonunion[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT malunion[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT biomechanical[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT cadaveric[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT cadaver[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT ((basic[Title/Abstract]) AND science[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang])) AND (English[lang]))) NOT revision[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT pediatric[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT physeal[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT children[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT instability[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT imaging[Title])) NOT salter[Title])) NOT physis[Title])) NOT shaft[Title])) NOT distal[Title])) NOT clavicle[Title])) NOT scapula[Title])) NOT ((diaphysis[Title]) AND diaphyseal[Title]))) NOT infection[Title])) NOT laboratory[Title/Abstract])) NOT metastatic[Title/Abstract])) NOT (((((((malignancy[Title/Abstract]) OR malignant[Title/Abstract]) OR tumor[Title/Abstract]) OR oncologic[Title/Abstract]) OR cyst[Title/Abstract]) OR aneurysmal[Title/Abstract]) OR unicameral[Title/Abstract]).

Study Selection

Data Extraction

We extracted data from the 13 studies that met the eligibility criteria. Details of study design, sample size, and patient demographics, including age, sex, and hand dominance, were recorded, as were mechanism of injury and concomitant anterior shoulder instability. To capture the most patients, we noted radiographic fracture displacement categorically rather than continuously; patients were divided into 2 displacement groups (<5 mm, >5 mm). Most studies did not define degree of comminution or specific direction of displacement per fracture, so these variables were not included in the data analysis. Nonoperative management and operative management were studied. We abstracted surgical factors, such as approach, method, fixation type (screws or sutures), and technique (suture anchors or transosseous tunnels). Clinical outcomes included physical examination findings, functional assessment results (patient satisfaction; Constant and University of California Los Angeles [UCLA] shoulder scores), and the number of revisions. Radiologic outcomes, retrieved from radiographs or computed tomography scans, focused on loss of reduction (as determined by the respective authors), malunion, nonunion, and heterotopic ossification. Each study’s methodologic quality and bias were evaluated with the 15-item Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS), which was described by Cowan and colleagues.23 The MCMS has been used to assess randomized and nonrandomized patient trials.24,25 Its scaled potential score ranges from 0 to 100 (85-100, excellent; 70-84, good; 55-69, fair; <55, poor).

Statistical Analysis

We report our data as weighted means (SDs). A mean was calculated for each study that reported a respective data point, and each mean was then weighed according to its study sample size. This calculation was performed by multiplying a study’s individual mean by the number of patients enrolled in that study and dividing the sum of these weighted data points by the number of eligible patients in all relevant studies. The result was that the nonweighted means from studies with smaller sample sizes did not carry as much weight as the nonweighted means from larger studies. We compared 3 paired groups: treatment type (nonoperative vs operative), fracture displacement amount (<5 mm vs >5 mm), and surgery type (open vs arthroscopic). Regarding all patient, surgery, and outcomes data, unpaired Student t tests were used for continuous variables and 2-tailed Fisher exact tests for categorical variables with α = 0.05 (SPSS Version 18; IBM).

Results

Postoperative physical examination findings were underreported so that surgical groups could be compared. Of all the surgical studies, 4 reported postoperative forward elevation (mean, 160°; SD, 9.8°) and external rotation (mean, 46.4°; SD 26.3°).14,15,18,22 No malunions and only 1 nonunion were reported in all 13 studies. No deaths or other serious medical complications were reported. Patients with anterior instability more often underwent surgery than were treated nonoperatively (39.2% vs 12.0%; P < .01) and more often had fractures displaced >5 mm than <5 mm (44.3% vs 14.5%; P < .01).

Fisher exact tests were used to perform isolated comparisons of screws and sutures as well as suture anchors and transosseous tunnels. Patients with screw fixation were significantly (P = .051) less likely to require reoperation (0/56; 0%) than patients with suture fixation (8/100; 8.0%). Screw fixation also led to significantly less stiffness (0% vs 12.0%; P < .01) but trended toward a higher rate of superficial infection (3.6% vs 0%; P = .13). There was no statistical difference in nerve injury rates between screws and sutures (1.8% vs 3.0%; P = 1.0). There were no significant differences in reoperations, stiffness, superficial infections, or nerve injuries between suture anchor and transosseous tunnel constructs.

For all 13 studies, mean (SD) MCMS was 41.1 (8.6).

Discussion

Five percent of all fractures involve the proximal humerus, and 20% of proximal humerus fractures are isolated greater tuberosity fractures.26,27 In his classic 1970 article, Neer6 formulated the 4-part proximal humerus fracture classification and defined greater tuberosity fracture “parts” using the same criteria as for other fracture “parts.” Neer6 recommended nonoperative management for isolated greater tuberosity fractures displaced <1 cm but did not present evidence corroborating his recommendation. More recent cutoffs for nonoperative management include 5 mm (general population) and 3 mm (athletes).7,17

In the present systematic review of greater tuberosity fractures, 3 separate comparisons were made: treatment type (nonoperative vs operative), fracture displacement amount (<5 mm vs >5 mm), and surgery type (open vs arthroscopic).

Treatment Type. Only 4 studies reported data on nonoperative treatment outcomes.5,12,16,17 Of these 4 studies, 2 found successful outcomes for fractures displaced <5 mm.12,17 Platzer and colleagues17 found good or excellent results in 97% of 135 shoulders after 4 years. Good results were defined with shoulder scores of ≥80 (Constant), <8 (Vienna), and >28 (UCLA), and excellent results were defined with maximum scores on 2 of the 3 systems. Platzer and colleagues17 also found nonsignificantly worse shoulder scores with superior displacement of 3 mm to 5 mm and recommended surgery for overhead athletes in this group. Rath and colleagues12 described a successful 3-phase rehabilitation protocol of sling immobilization for 3 weeks, pendulum exercises for 3 weeks, and active exercises thereafter. By an average of 31 months, patient satisfaction scores improved to 9.5 from 4.2 (10-point scale), though the authors cautioned that pain and decreased motion lasted 8 months on average. Conservative treatment was far less successful in the 2 studies of fractures displaced >5 mm.5,16 Keene and colleagues16 reported unsatisfactory results in all 4 patients with fractures displaced >1.5 cm. In a study separate from their 2005 analysis,17 Platzer and colleagues5 in 2008 evaluated displaced fractures and found function and patient satisfaction were inferior after nonoperative treatment than after surgery. The studies by Keene and colleagues16 and Platzer and colleagues5 support the finding of an overall lower patient satisfaction rate in nonoperative patients.

Fracture Displacement Amount. Only 2 arthroscopic studies and no open studies addressed surgery for fractures displaced <5 mm. Fewer than 16% of these fractures were managed operatively, and <1% required reoperation. By contrast, almost all fractures displaced >5 mm were managed operatively, and 3.6% required reoperation. Radiographic loss of reduction was more common in fractures displaced <5 mm, primarily because they were managed without fixation. Radiographic loss of reduction was reported in only 9 operatively treated patients, none of whom was symptomatic enough to require another surgery.5 Reoperations were most commonly performed for stiffness, which itself was significantly more common in fractures displaced >5 mm. Bhatia and colleagues14 reported the highest reoperation rate (14.3%; 3/21), but they studied more complex, comminuted fractures of the greater tuberosity. Two of their 3 reoperations were biceps tenodeses for inflamed, stiff tenosynovitis, and the third patient had a foreign body giant cell reaction to suture material. Fewer than 1% of patients with operatively managed displaced fractures required revision ORIF, and <2% developed a superficial infection or postoperative nerve palsy.19,22 For displaced greater tuberosity fractures, surgery is highly successful overall, complication rates are very low, and 90% of patients report being satisfied.

Surgery Type. Patients were divided into 2 groups. In the nonarthroscopic group, open and percutaneous approaches were used. All studies that described a percutaneous approach used screw fixation5,21; in addition, 32 patients were treated with screws through an open approach.2,5 The other open and arthroscopic studies used suture fixation. Interestingly, no studies reported on clinical outcomes of fragment excision. There were no statistically significant differences in rates of reoperation, stiffness, infection, or neurologic injury between the arthroscopic and nonarthroscopic groups. Patient satisfaction scores were slightly higher in the nonarthroscopic group (91.0% vs 87.8%), but the difference was not statistically significant.

With surgical techniques isolated, there were no significant differences between suture anchors and transosseous tunnel constructs, but screws performed significantly better than suture techniques. Compared with suture fixation, screw fixation led to significantly fewer cases of stiffness and reoperation, which suggests surgeons need to give screws more consideration in the operative management of these fractures. However, the number of patients treated with screws was smaller than the number treated with suture fixation; it is possible the differences between these cohorts would be eliminated if there were more patients in the screw cohort. In addition, screw fixation was universally performed with an open or percutaneous approach and trended toward a higher infection rate. As screw and suture techniques have low rates of complications and reoperations, we recommend leaving fixation choice to the surgeon.

Anterior shoulder instability has been associated with greater tuberosity fractures.1,8,19 The supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles all insert into the greater tuberosity and resist anterior translation of the proximal humerus. Loss of this dynamic muscle stabilization is amplified by tuberosity fracture displacement: Anterior shoulder instability was significantly more common in fractures displaced >5 mm (44.3%) vs <5 mm (14.5%). In turn, glenohumeral instability was more common in patients treated with surgery, specifically open surgery, because displaced fractures may not be as easily accessed with arthroscopic techniques. No studies reported concomitant labral repair or capsular plication techniques.

This systematic review was limited by the studies analyzed. All but 1 study5 had level IV evidence. Mean (SD) MCMS was 41.8 (8.6). Any MCMS score <54 indicates a poor methodology level, but this scoring system is designed for randomized controlled trials,23 and there were none in this study. Physical examination findings, such as range of motion, were underreported. In addition, radiographic parameters were not consistently described but rather were determined by the respective authors’ subjective interpretations of malunion, nonunion, and loss of reduction. Publication bias is present in that we excluded non- English language studies and medical conference abstracts and may have omitted potentially eligible studies not discoverable with our search methodology. Performance bias is a factor in any systematic review with multiple surgeons and wide variation in surgical technique.

Conclusion

Greater tuberosity fractures displaced <5 mm may be safely managed nonoperatively, as there are no reports of nonoperatively managed fractures that subsequently required surgery. Nonoperative treatment was initially associated with low patient satisfaction, but only because displaced fractures were conservatively managed in early studies.5,16 Fractures displaced >5 mm respond well to operative fixation with screws, suture anchors, or transosseous suture tunnels. Stiffness is the most common postoperative complication (<6%), followed by heterotopic ossification, transient neurapraxias, and superficial infection. There are no discernible differences in outcome between open and arthroscopic techniques, but screw fixation may lead to significantly fewer cases of stiffness and reoperation in comparison with suture constructs.

1. Verdano MA, Aliani D, Pellegrini A, Baudi P, Pedrazzi G, Ceccarelli F. Isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity in proximal humerus: does the direction of displacement influence functional outcome? An analysis of displacement in greater tuberosity fractures. Acta Biomed. 2013;84(3):219-228.

2. Yin B, Moen TC, Thompson SA, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Operative treatment of isolated greater tuberosity fractures: retrospective review of clinical and functional outcomes. Orthopedics. 2012;35(6):e807-e814.

3. Green A, Izzi J. Isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(6):641-649.

4. Norouzi M, Naderi MN, Komasi MH, Sharifzadeh SR, Shahrezaei M, Eajazi A. Clinical results of using the proximal humeral internal locking system plate for internal fixation of displaced proximal humeral fractures. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(5):E64-E68.

5. Platzer P, Thalhammer G, Oberleitner G, et al. Displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity: a comparison of operative and nonoperative treatment. J Trauma. 2008;65(4):843-848.

6. Neer CS. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52(6):1077-1089.

7. Park TS, Choi IY, Kim YH, Park MR, Shon JH, Kim SI. A new suggestion for the treatment of minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1997;56(3):171-176.

8. McLaughlin HL. Dislocation of the shoulder with tuberosity fracture. Surg Clin North Am. 1963;43:1615-1620.

9. DeBottis D, Anavian J, Green A. Surgical management of isolated greater tuberosity fractures of the proximal humerus. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(2):207-218.

10. Monga P, Verma R, Sharma VK. Closed reduction and external fixation for displaced proximal humeral fractures. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2009;17(2):142-145.

11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006-1012.

12. Rath E, Alkrinawi N, Levy O, Debbi R, Amar E, Atoun E. Minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity: outcome of non-operative treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(10):e8-e11.

13. Dimakopoulos P, Panagopoulos A, Kasimatis G. Transosseous suture fixation of proximal humeral fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1700-1709.

14. Bhatia DN, van Rooyen KS, Toit du DF, de Beer JF. Surgical treatment of comminuted, displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus: a new technique of double-row suture-anchor fixation and long-term results. Injury. 2006;37(10):946-952.

15. Flatow EL, Cuomo F, Maday MG, Miller SR, McIlveen SJ, Bigliani LU. Open reduction and internal fixation of two-part displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal part of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(8):1213-1218.

16. Keene JS, Huizenga RE, Engber WD, Rogers SC. Proximal humeral fractures: a correlation of residual deformity with long-term function. Orthopedics. 1983;6(2):173-178.

17. Platzer P, Kutscha-Lissberg F, Lehr S, Vecsei V, Gaebler C. The influence of displacement on shoulder function in patients with minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity. Injury. 2005;36(10):1185-1189.

18. Park SE, Ji JH, Shafi M, Jung JJ, Gil HJ, Lee HH. Arthroscopic management of occult greater tuberosity fracture of the shoulder. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(4):475-482.

19. Dimakopoulos P, Panagopoulos A, Kasimatis G, Syggelos SA, Lambiris E. Anterior traumatic shoulder dislocation associated with displaced greater tuberosity fracture: the necessity of operative treatment. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(2):104-112.

20. Kim SH, Ha KI. Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic shoulders with minimally displaced greater tuberosity fracture. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(7):695-700.

21. Chen CY, Chao EK, Tu YK, Ueng SW, Shih CH. Closed management and percutaneous fixation of unstable proximal humerus fractures. J Trauma. 1998;45(6):1039-1045.

22. Ji JH, Shafi M, Song IS, Kim YY, McFarland EG, Moon CY. Arthroscopic fixation technique for comminuted, displaced greater tuberosity fracture. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(5):600-609.

23. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderón S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

24. Harris JD, Siston RA, Pan X, Flanigan DC. Autologous chondrocyte implantation: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(12):2220-2233.

25. Harris JD, Siston RA, Brophy RH, Lattermann C, Carey JL, Flanigan DC. Failures, re-operations, and complications after autologous chondrocyte implantation—a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(7):779-791.

26. Chun JM, Groh GI, Rockwood CA. Two-part fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3(5):273-287.

27. Gruson KI, Ruchelsman DE, Tejwani NC. Isolated tuberosity fractures of the proximal humeral: current concepts. Injury. 2008;39(3):284-298.

1. Verdano MA, Aliani D, Pellegrini A, Baudi P, Pedrazzi G, Ceccarelli F. Isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity in proximal humerus: does the direction of displacement influence functional outcome? An analysis of displacement in greater tuberosity fractures. Acta Biomed. 2013;84(3):219-228.

2. Yin B, Moen TC, Thompson SA, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Operative treatment of isolated greater tuberosity fractures: retrospective review of clinical and functional outcomes. Orthopedics. 2012;35(6):e807-e814.

3. Green A, Izzi J. Isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(6):641-649.

4. Norouzi M, Naderi MN, Komasi MH, Sharifzadeh SR, Shahrezaei M, Eajazi A. Clinical results of using the proximal humeral internal locking system plate for internal fixation of displaced proximal humeral fractures. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(5):E64-E68.

5. Platzer P, Thalhammer G, Oberleitner G, et al. Displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity: a comparison of operative and nonoperative treatment. J Trauma. 2008;65(4):843-848.

6. Neer CS. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52(6):1077-1089.

7. Park TS, Choi IY, Kim YH, Park MR, Shon JH, Kim SI. A new suggestion for the treatment of minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1997;56(3):171-176.

8. McLaughlin HL. Dislocation of the shoulder with tuberosity fracture. Surg Clin North Am. 1963;43:1615-1620.

9. DeBottis D, Anavian J, Green A. Surgical management of isolated greater tuberosity fractures of the proximal humerus. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(2):207-218.

10. Monga P, Verma R, Sharma VK. Closed reduction and external fixation for displaced proximal humeral fractures. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2009;17(2):142-145.

11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006-1012.

12. Rath E, Alkrinawi N, Levy O, Debbi R, Amar E, Atoun E. Minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity: outcome of non-operative treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(10):e8-e11.

13. Dimakopoulos P, Panagopoulos A, Kasimatis G. Transosseous suture fixation of proximal humeral fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1700-1709.

14. Bhatia DN, van Rooyen KS, Toit du DF, de Beer JF. Surgical treatment of comminuted, displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus: a new technique of double-row suture-anchor fixation and long-term results. Injury. 2006;37(10):946-952.

15. Flatow EL, Cuomo F, Maday MG, Miller SR, McIlveen SJ, Bigliani LU. Open reduction and internal fixation of two-part displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity of the proximal part of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(8):1213-1218.

16. Keene JS, Huizenga RE, Engber WD, Rogers SC. Proximal humeral fractures: a correlation of residual deformity with long-term function. Orthopedics. 1983;6(2):173-178.

17. Platzer P, Kutscha-Lissberg F, Lehr S, Vecsei V, Gaebler C. The influence of displacement on shoulder function in patients with minimally displaced fractures of the greater tuberosity. Injury. 2005;36(10):1185-1189.

18. Park SE, Ji JH, Shafi M, Jung JJ, Gil HJ, Lee HH. Arthroscopic management of occult greater tuberosity fracture of the shoulder. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(4):475-482.

19. Dimakopoulos P, Panagopoulos A, Kasimatis G, Syggelos SA, Lambiris E. Anterior traumatic shoulder dislocation associated with displaced greater tuberosity fracture: the necessity of operative treatment. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(2):104-112.

20. Kim SH, Ha KI. Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic shoulders with minimally displaced greater tuberosity fracture. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(7):695-700.

21. Chen CY, Chao EK, Tu YK, Ueng SW, Shih CH. Closed management and percutaneous fixation of unstable proximal humerus fractures. J Trauma. 1998;45(6):1039-1045.

22. Ji JH, Shafi M, Song IS, Kim YY, McFarland EG, Moon CY. Arthroscopic fixation technique for comminuted, displaced greater tuberosity fracture. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(5):600-609.

23. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderón S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

24. Harris JD, Siston RA, Pan X, Flanigan DC. Autologous chondrocyte implantation: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(12):2220-2233.

25. Harris JD, Siston RA, Brophy RH, Lattermann C, Carey JL, Flanigan DC. Failures, re-operations, and complications after autologous chondrocyte implantation—a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(7):779-791.

26. Chun JM, Groh GI, Rockwood CA. Two-part fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3(5):273-287.

27. Gruson KI, Ruchelsman DE, Tejwani NC. Isolated tuberosity fractures of the proximal humeral: current concepts. Injury. 2008;39(3):284-298.

Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes of Total Shoulder Arthroplasty With a Hybrid Dual-Radii Glenoid Component

Take-Home Points

- The authors have developed a total shoulder glenoid prosthesis that conforms with the humeral head in its center and is nonconforming on its peripheral edge.

- All clinical survey and range of motion parameters demonstrated statistically significant improvements at final follow-up.

- Only 3 shoulders (1.7%) required revision surgery.

- Eighty-six (63%) of 136 shoulders demonstrated no radiographic evidence of glenoid loosening.

- This is the first and largest study that evaluates the clinical and radiographic outcomes of this hybrid shoulder prosthesis.

Fixation of the glenoid component is the limiting factor in modern total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). Glenoid loosening, the most common long-term complication, necessitates revision in up to 12% of patients.1-4 By contrast, humeral component loosening is relatively uncommon, affecting as few as 0.34% of patients.5 Multiple long-term studies have found consistently high rates (45%-93%) of radiolucencies around the glenoid component.3,6,7 Although their clinical significance has been debated, radiolucencies around the glenoid component raise concern about progressive loss of fixation.

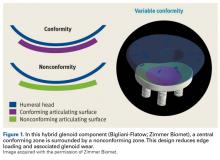

Since TSA was introduced in the 1970s, complications with the glenoid component have been addressed with 2 different designs: conforming (congruent) and nonconforming. In a congruent articulation, the radii of curvature of the glenoid and humeral head components are identical, whereas they differ in a nonconforming model. Joint conformity is inversely related to glenohumeral translation.8 Neer’s original TSA was made congruent in order to limit translation and maximize the contact area. However, this design results in edge loading and a so-called rocking-horse phenomenon, which may lead to glenoid loosening.9-13 Surgeons therefore have increasingly turned to nonconforming implants. In the nonconforming design, the radius of curvature of the humeral head is smaller than that of the glenoid. Although this design may reduce edge loading,14 it allows more translation and reduces the relative contact area of the glenohumeral joint. As a result, more contact stress is transmitted to the glenoid component, leading to polyethylene deformation and wear.15,16

Dual radii of curvature are designed to augment joint stability without increasing component wear. Biomechanical data have indicated that edge loading is not increased by having a central conforming region added to a nonconforming model.17 The clinical value of this prosthesis, however, has not been determined. Therefore, we conducted a study to describe the intermediate-term clinical and radiographic outcomes of TSAs that use a novel hybrid glenoid component.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved (protocol AAAD3473) by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University and was conducted in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations.

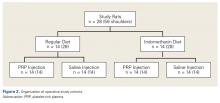

Patient Selection

At Columbia University Medical Center, Dr. Bigliani performed 196 TSAs with a hybrid glenoid component (Bigliani-Flatow; Zimmer Biomet) in 169 patients between September 1998 and November 2007. All patients had received a diagnosis of primary glenohumeral arthritis as defined by Neer.18 Patients with previous surgery such as rotator cuff repair or subacromial decompression were included in our review, and patients with a nonprimary form of arthritis, such as rheumatoid, posttraumatic, or post-capsulorrhaphy arthritis, were excluded.

Operative Technique

For all surgeries, Dr. Bigliani performed a subscapularis tenotomy with regional anesthesia and a standard deltopectoral approach. A partial anterior capsulectomy was performed to increase the glenoid’s visibility. The inferior labrum was removed with a needle-tip bovie while the axillary nerve was being protected with a metal finger or narrow Darrach retractor. After reaming and trialing, the final glenoid component was cemented into place. Cement was placed only in the peg or keel holes and pressurized twice before final implantation. Of the 196 glenoid components, 168 (86%) were pegged and 28 (14%) keeled; in addition,190 of these components were all-polyethylene, whereas 6 had trabecular-metal backing. All glenoid components incorporated the hybrid design of dual radii of curvature. After the glenoid was cemented, the final humeral component was placed in 30° of retroversion. Whenever posterior wear was found, retroversion was reduced by 5° to 10°. The humeral prosthesis was cemented in cases (104/196, 53%) of poor bone quality or a large canal.

After surgery, the patient’s sling was fitted with an abduction pillow and a swathe, to be worn the first 24 hours, and the arm was passively ranged. Patients typically were discharged on postoperative day 2. Then, for 2 weeks, they followed an assisted passive range of motion (ROM) protocol, with limited external rotation, for promotion of subscapularis healing.

Clinical Outcomes

Dr. Bigliani assessed preoperative ROM in all planes. During initial evaluation, patients completed a questionnaire that consisted of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey19,20 (SF-36) and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons21 (ASES) and Simple Shoulder Test22 (SST) surveys. Postoperative clinical data were collected from office follow-up visits, survey questionnaires, or both. Postoperative office data included ROM, subscapularis integrity testing (belly-press or lift-off), and any complications. Patients with <1 year of office follow-up were excluded. In addition, the same survey questionnaire that was used before surgery was mailed to all patients after surgery; then, for anyone who did not respond by mail, we attempted contact by telephone. Neer criteria were based on patients’ subjective assessment of each arm on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = very satisfied, 2 = satisfied, 3 = dissatisfied). Patients were also asked about any specific complications or revision operations since their index procedure.

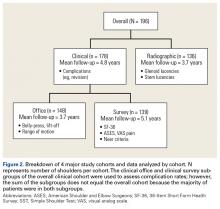

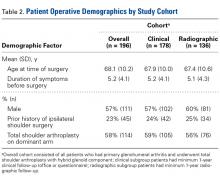

Physical examination and office follow-up data were obtained for 129 patients (148/196 shoulders, 76% follow-up) at a mean of 3.7 years (range 1.0-10.2 years) after surgery. Surveys were completed by 117 patients (139/196 shoulders, 71% follow-up) at a mean of 5.1 years (range, 1.6-11.2 years) after surgery. Only 15 patients had neither 1 year of office follow-up nor a completed questionnaire. The remaining 154 patients (178/196 shoulders, 91% follow-up) had clinical follow-up with office, mail, or telephone questionnaire at a mean of 4.8 years (range, 1.0-11.2 years) after surgery. This cohort of patients was used to determine rates of surgical revisions, subscapularis tears, dislocations, and other complications.

Radiographic Outcomes

Patients were included in the radiographic analysis if they had a shoulder radiograph at least 1 year after surgery. One hundred nineteen patients (136/196 shoulders, 69% follow-up) had radiographic follow-up at a mean of 3.7 years (range, 1.0-9.4 years) after surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata Version 10.0. Paired t tests were used to compare preoperative and postoperative numerical data, including ROM and survey scores. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and set statistical significance at P < .05. For qualitative measures, the Fisher exact test was used. Survivorship analysis was performed according to the Kaplan-Meier method, with right-censored data for no event or missing data.25

Results

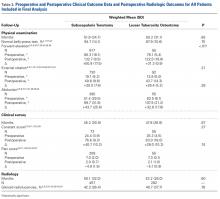

Clinical Analysis of Demographics

In demographics, the clinical and radiographic patient subgroups were similar to each other and to the overall study population (Table 2). Of 196 patients overall, 16 (8%) had a concomitant rotator cuff repair, and 27 (14%) underwent staged bilateral shoulder arthroplasties.

Clinical Analysis of ROM and Survey Scores

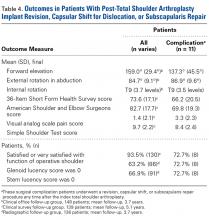

Operative shoulder ROM in forward elevation, external rotation at side, external rotation in abduction, and internal rotation all showed statistically significant (P < .001) improvement from before surgery to after surgery. Over 3.7 years, mean (SD) forward elevation improved from 107.3° (34.8°) to 159.0° (29.4°), external rotation at side improved from 20.4° (16.7°) to 49.4° (11.3°), and external rotation in abduction improved from 53.7° (24.3°) to 84.7° (9.1°). Internal rotation improved from a mean (SD) vertebral level of S1 (6.0 levels) to T9 (3.7 levels).

All validated survey scores also showed statistically significant (P < .001) improvement from before surgery to after surgery. Over 5.1 years, mean (SD) SF-36 scores improved from 64.9 (13.4) to 73.6 (17.1), ASES scores improved from 41.1 (22.5) to 82.7 (17.7), SST scores improved from 3.9 (2.8) to 9.7 (2.2), and visual analog scale pain scores improved from 5.6 (3.2) to 1.4 (2.1). Of 139 patients with follow-up, 130 (93.5%) were either satisfied or very satisfied with their TSA, and only 119 (86%) were either satisfied or very satisfied with the nonoperative shoulder.

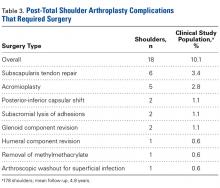

Clinical Analysis of Postoperative Complications

Of the 178 shoulders evaluated for complications, 3 (1.7%) underwent revision surgery. Mean time to revision was 2.3 years (range, 1.5-3.9 years). Two revisions involved the glenoid component, and the third involved the humerus. In one of the glenoid cases, a 77-year-old woman fell and sustained a fracture at the base of the trabecular metal glenoid pegs; her component was revised to an all-polyethylene component, and she had no further complications. In the other glenoid case, a 73-year-old man’s all-polyethylene component loosened after 2 years and was revised to a trabecular metal implant, which loosened as well and was later converted to a hemiarthroplasty. In the humeral case, a 33-year-old man had his 4-year-old index TSA revised to a cemented stem and had no further complications.

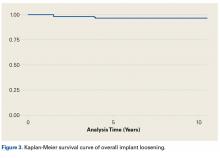

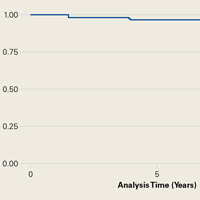

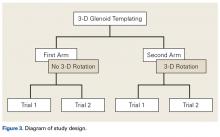

Table 4 compares the clinical and radiographic outcomes of patients who required subscapularis repair, capsular shift, or implant revision with the outcomes of all other study patients, and Figure 3 shows Kaplan-Meier survivorship.

Postoperative Radiographic Analysis

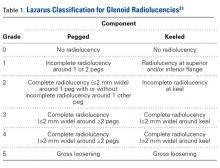

Glenoid Component. At a mean of 3.7 years (minimum, 1 year) after surgery, 86 (63%) of 136 radiographically evaluated shoulders showed no glenoid lucencies; the other 50 (37%) showed ≥1 lucency. Of the 136 shoulders, 33 (24%) had a Lazarus score of 1, 15 (11%) had a score of 2, and only 2 (2%) had a score of 3. None of the shoulders had a score of 4 or 5.

Humeral Component. Of the 136 shoulders, 91 (67%) showed no lucencies in any of the 8 humeral stem zones; the other 45 (33%) showed 1 to 3 lucencies. Thirty (22%) of the 136 shoulders had 1 stem lucency zone, 8 (6%) had 2, and 3 (2%) had 3. None of the shoulders had >3 periprosthetic zones with lucent lines.

Discussion

In this article, we describe a hybrid glenoid TSA component with dual radii of curvature. Its central portion is congruent with the humeral head, and its peripheral portion is noncongruent and larger. The most significant finding of our study is the low rate (1.1%) of glenoid component revision 4.8 years after surgery. This rate is the lowest that has been reported in a study of ≥100 patients. Overall implant survival appeared as an almost flat Kaplan-Meir curve. We attribute this low revision rate to improved biomechanics with the hybrid glenoid design.

Symptomatic glenoid component loosening is the most common TSA complication.1,26-28 In a review of 73 Neer TSAs, Cofield7 found glenoid radiolucencies in 71% of patients 3.8 years after surgery. Radiographic evidence of loosening, defined as component migration, or tilt, or a circumferential lucency 1.5 mm thick, was present in another 11% of patients, and 4.1% developed symptomatic loosening that required glenoid revision. In a study with 12.2-year follow-up, Torchia and colleagues3 found rates of 84% for glenoid radiolucencies, 44% for radiographic loosening, and 5.6% for symptomatic loosening that required revision. In a systematic review of studies with follow-up of ≥10 years, Bohsali and colleagues27 found similar lucency and radiographic loosening rates and a 7% glenoid revision rate. These data suggest glenoid radiolucencies may progress to component loosening.

Degree of joint congruence is a key factor in glenoid loosening. Neer’s congruent design increases the contact area with concentric loading and reduces glenohumeral translation, which leads to reduced polyethylene wear and improved joint stability. In extreme arm positions, however, humeral head subluxation results in edge loading and a glenoid rocking-horse effect.9-13,17,29-31 Conversely, nonconforming implants allow increased glenohumeral translation without edge loading,14 though they also reduce the relative glenohumeral contact area and thus transmit more contact stress to the glenoid.16,17 A hybrid glenoid component with central conforming and peripheral nonconforming zones may reduce the rocking-horse effect while maximizing ROM and joint stability. Wang and colleagues32 studied the biomechanical properties of this glenoid design and found that the addition of a central conforming region did not increase edge loading.

Additional results from our study support the efficacy of a hybrid glenoid component. Patients’ clinical outcomes improved significantly. At 5.1 years after surgery, 93.5% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with their procedure and reported less satisfaction (86%) with the nonoperative shoulder. Also significant was the reduced number of radiolucencies. At 3.7 years after surgery, the overall percentage of shoulders with ≥1 glenoid radiolucency was 37%, considerably lower than the 82% reported by Cofield7 and the rates in more recent studies.3,16,33-36 Of the 178 shoulders in our study, 10 (5.6%) had subscapularis tears, and 6 (3.4%) of 178 had these tears surgically repaired. This 3.4% compares favorably with the 5.9% (of 119 patients) found by Miller and colleagues37 28 months after surgery. Of our 178 shoulders, 27 (15.2%) had clinically significant postoperative complications; 18 (10.1%) of the 178 had these complications surgically treated, and 9 (5.1%) had them managed nonoperatively. Bohsali and colleagues27 systematically reviewed 33 TSA studies and found a slightly higher complication rate (16.3%) 5.3 years after surgery. Furthermore, in our study, the 11 patients who underwent revision, capsular shift, or subscapularis repair had final outcomes comparable to those of the rest of our study population.