User login

Factors Associated With COVID-19 Disease Severity in US Children and Adolescents

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to more than 40 million infections and more than 650,000 deaths in the United States alone.1 Morbidity and mortality have disproportionately affected older adults.2-4 However, acute infection and delayed effects, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), occur and can lead to severe complications, hospitalization, and death in pediatric patients.5,6 Due to higher clinical disease prevalence and morbidity in the adult population, we have learned much about the clinical factors associated with severe adult COVID-19 disease.5,7-9 Such clinical factors include older age, concurrent comorbidities, smoke exposure, and Black race or Hispanic ethnicity, among others.5,7-10 However, there is a paucity of data on severe COVID-19 disease in pediatric patients.5,11,12 In addition, most immunization strategies and pharmacologic treatments for COVID-19 have not been evaluated or approved for use in children.13 To guide targeted prevention and treatment strategies, there is a critical need to identify children and adolescents—who are among the most vulnerable patient populations—at high risk for severe disease.

Identifying the clinical factors associated with severe COVID-19 disease will help with prioritizing and allocating vaccines when they are approved for use in patients younger than 12 years.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study of patients presenting for care at pediatric hospitals that report data to the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database. The PHIS administrative database includes billing and utilization data from 45 US tertiary care hospitals affiliated with the Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, Kansas). Data quality and reliability are ensured through a joint validation effort between the Children’s Hospital Association and participating hospitals. Hospitals submit discharge data, including demographics, diagnoses, and procedures using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes, along with daily detailed information on pharmacy, location of care, and other services.

Study Population

Patients 30 days to 18 years of age discharged from the emergency department (ED) or inpatient setting with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19 (ICD-10 codes U.071 and U.072) between April 1, 2020, and September 30, 2020, were eligible for inclusion.14 In a prior study, the positive predictive value of an ICD-10–coded diagnosis of COVID-19 among hospitalized pediatric patients was 95.5%, compared with reverse transcription polymerase reaction results or presence of MIS-C.15 The diagnostic code for COVID-19 (ICD-10-CM) also had a high sensitivity (98.0%) in the hospitalized population.16 Acknowledging the increasing practice of screening patients upon admission, and in an attempt to minimize potential misclassification, we did not include encounters with secondary diagnoses of COVID-19 in our primary analyses. Pediatric patients with surgical diagnoses and neonates who never left the hospital were also excluded.

Factors Associated With Severe COVID-19 Disease

Exposures of interest were determined a priori based on current evidence in the literature and included patient age (0-4 years, 5-11 years, and 12-18 years), sex, race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, other non-White race [defined as Pacific Islander, Native American, or other]), payor type, cardiovascular complex chronic conditions (CCC), neuromuscular CCC, obesity/type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), pulmonary CCC, asthma (defined using ICD-10 codes17), and immunocompromised CCC

Pediatric Complications and Conditions Associated With COVID-19

Based on current evidence and expert opinion of study members, associated diagnoses and complications co-occurring with a COVID-19 diagnosis were defined a priori and identified through ICD-10 codes (Appendix Table 1). These included acute kidney injury, acute liver injury, aseptic meningitis, asthma exacerbation, bronchiolitis, cerebral infarction, croup, encephalitis, encephalopathy, infant fever, febrile seizure, gastroenteritis/dehydration, Kawasaki disease/MIS-C, myocarditis/pericarditis, pneumonia, lung effusion or empyema, respiratory failure, sepsis, nonfebrile seizure, pancreatitis, sickle cell complications, and thrombotic complications.

Outcomes

COVID-19 severity outcomes were assessed as follows: (1) mild = ED discharge; (2) moderate = inpatient admission; (3) severe = intensive care unit (ICU) admission without mechanical ventilation, shock, or death; and (4) very severe = ICU admission with mechanical ventilation, shock, or death.19 This ordinal ranking system did not violate the proportional odds assumption. Potential reasons for admission to the ICU without mechanical ventilation, shock, or death include, but are not limited to, need for noninvasive ventilation, vital sign instability, dysrhythmias, respiratory insufficiency, or complications arising from concurrent conditions (eg, thrombotic events, need for continuous albuterol therapy). We examined several secondary, hospital-based outcomes, including associated diagnoses and complications, all-cause 30-day healthcare reutilization (ED visit or rehospitalization), length of stay (LOS), and ICU LOS.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics were summarized using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and geometric means with SD and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables, as appropriate. Factors associated with hospitalization (encompassing severity levels 2-4) vs ED discharge (severity level 1) were assessed using logistic regression. Factors associated with increasing severity among hospitalized pediatric patients (severity levels 2, 3, and 4) were assessed using ordinal logistic regression. Covariates in these analyses included race and ethnicity, age, sex, payor, cardiovascular CCC, neurologic/neuromuscular CCC, obesity/type 2 DM, pulmonary CCC, asthma, and immunocompromised CCC. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and corresponding 95% CI for each risk factor were generated using generalized linear mixed effects models and random intercepts for each hospital. Given the potential for diagnostic misclassification of pediatric patients with COVID-19 based on primary vs secondary diagnoses, we performed sensitivity analyses defining the study population as those with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19 and those with a secondary diagnosis of COVID-19 plus a concurrent primary diagnosis of a condition associated with COVID-19 (Appendix Table 1).

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc), and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. The Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center determined that this study of de-identified data did not meet the criteria for human subjects research.

RESULTS

Study Population

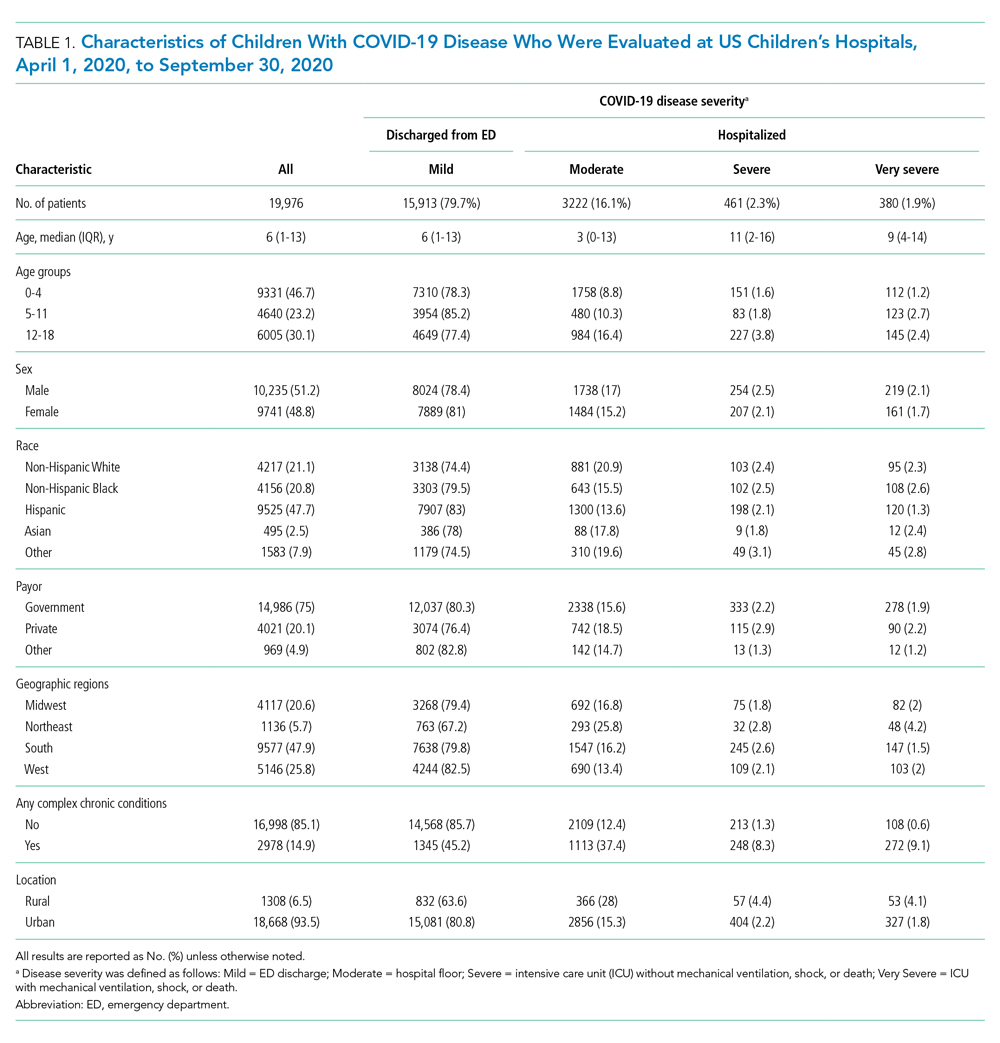

A total of 19,976 encounters were included in the study. Of those, 15,913 (79.7%) were discharged from the ED and 4063 (20.3%) were hospitalized (Table 1). The most common race/ethnicity was Hispanic (9741, 48.8%), followed by non-Hispanic White (4217, 21.1%). Reference race/ethnicity data for the overall 2019 PHIS population can be found in Appendix Table 2.

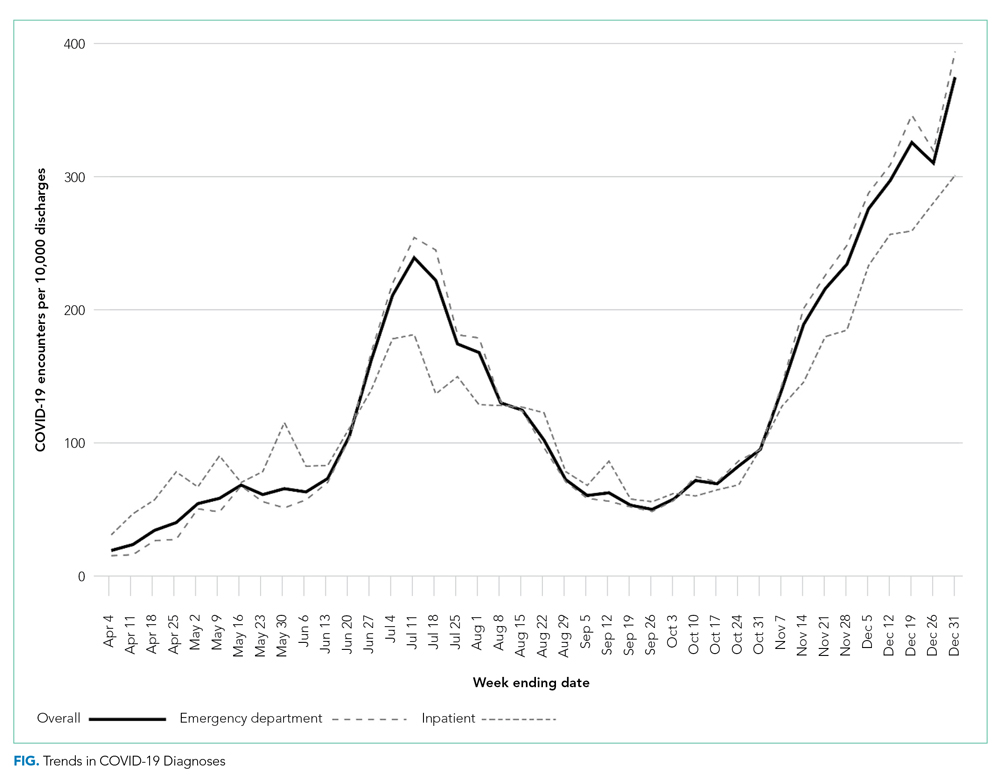

The severity distribution among the hospitalized population was moderate (3222, 79.3%), severe (431, 11.3%), and very severe (380, 9.4%). The frequency of COVID-19 diagnoses increased late in the study period (Figure). Among those hospitalized, the median LOS for the index admission was 2 days (IQR, 1-4), while among those admitted to the ICU, the median LOS was 3 days (IQR, 2-5).

Overall, 10.1% (n = 2020) of the study population had an all-cause repeat encounter (ie, subsequent ED encounter or hospitalization) within 30 days following the index discharge. Repeat encounters were more frequent among patients hospitalized than among those discharged from the ED (Appendix Table 3).

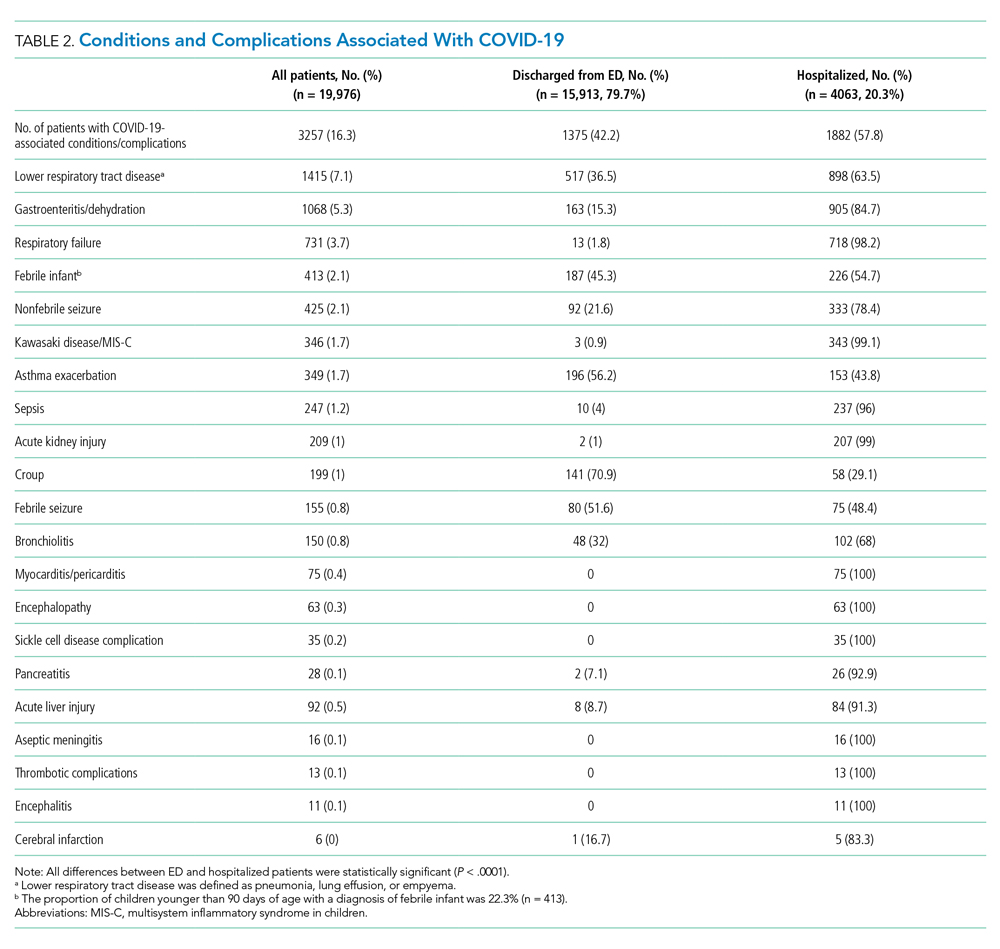

Prevalence of Conditions and Complications Associated With COVID-19

Overall, 3257 (16.3%) patients had one or more co-occurring diagnoses categorized as a COVID-19–associated condition or complication. The most frequent diagnoses included lower respiratory tract disease (pneumonia, lung effusion, or empyema; n = 1415, 7.1%), gastroenteritis/dehydration (n = 1068, 5.3%), respiratory failure (n = 731, 3.7%), febrile infant (n = 413, 2.1%), and nonfebrile seizure (n = 425, 2.1%). Aside from nonfebrile seizure, neurological complications were less frequent and included febrile seizure (n = 155, 0.8%), encephalopathy (n = 63, 0.3%), aseptic meningitis (n = 16, 0.1%), encephalitis (n = 11, 0.1%), and cerebral infarction (n = 6, <0.1%). Kawasaki disease and MIS-C comprised 1.7% (n = 346) of diagnoses. Thrombotic complications occurred in 0.1% (n = 13) of patients. Overall, these conditions and complications associated with COVID-19 were more frequent in hospitalized patients than in those discharged from the ED (P < .001) (Table 2).

Factors Associated With COVID-19 Disease Severity

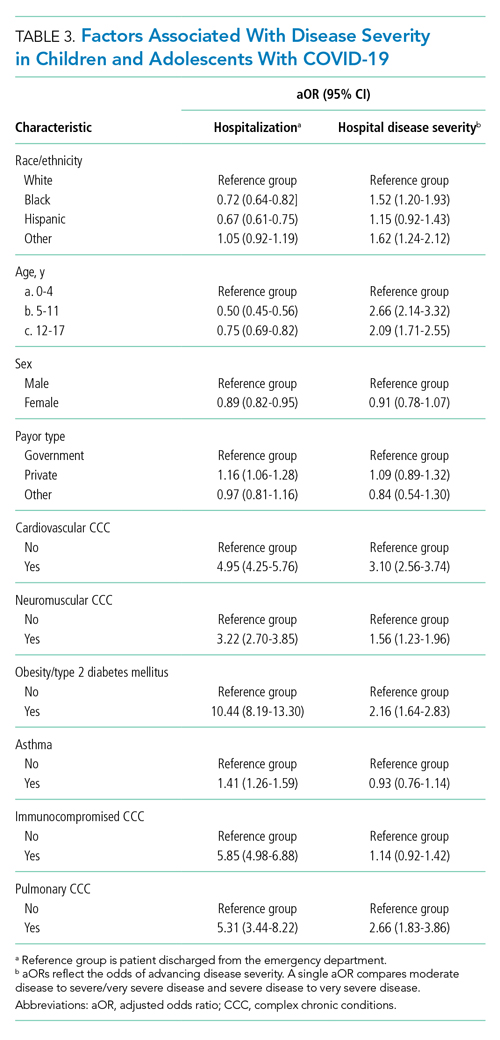

Compared to pediatric patients with COVID-19 discharged from the ED, factors associated with increased odds of hospitalization included private payor insurance; obesity/type 2 DM; asthma; and cardiovascular, immunocompromised, neurologic/neuromuscular, and pulmonary CCCs (Table 3). Factors associated with decreased risk of hospitalization included Black race or Hispanic ethnicity compared with White race; female sex; and age 5 to 11 years and age 12 to 17 years (vs age 0-4 years). Among children and adolescents hospitalized with COVID-19, factors associated with greater disease severity included Black or other non-White race; age 5 to 11 years; age 12 to 17 years; obesity/type 2 DM; immunocompromised conditions; and cardiovascular, neurologic/neuromuscular, and pulmonary CCCs (Table 3).

Sensitivity Analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis that expanded the study population to include those with a secondary diagnosis of COVID-19 plus a diagnosis of a COVID-19–associated condition or complication. Analyses using the expanded population (N = 21,247) were similar to the primary analyses (Appendix Table 4 and Appendix Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In this large multicenter study evaluating COVID-19 disease severity in more than 19,000 patients presenting for emergency care at US pediatric hospitals, approximately 20% were hospitalized, and among those hospitalized almost a quarter required ICU care. Clinical risk factors associated with increased risk of hospitalization include private payor status and selected comorbidities (obesity/type 2 DM; asthma; and cardiovascular, pulmonary, immunocompromised, neurologic/neuromuscular CCCs), while those associated with decreased risk of hospitalization include older age, female sex, and Black race or Hispanic ethnicity. Factors associated with severe disease among hospitalized pediatric patients include Black or other non-White race, school age (≥5 years), and certain chronic conditions (cardiovascular disease, obesity/type 2 DM, neurologic or neuromuscular disease). Sixteen percent of patients had a concurrent diagnosis for a condition or complication associated with COVID-19.

While the study population (ie, children and adolescents presenting to the ED) represents a small fraction of children and adolescents in the community with SARS-CoV-2 infection, the results provide important insight into factors of severe COVID-19 in the pediatric population. A report from France suggested ventilatory or hemodynamic support or death were independently associated with older age (≥10 years), elevated C-reactive protein, and hypoxemia.12 An Italian study found that younger age (0-4 years) was associated with less severe disease, while preexisting conditions were more likely in patients with severe disease.11 A single-center case series of 50 patients (aged ≤21 years) hospitalized at a children’s hospital in New York City found respiratory failure (n = 9) was more common in children older than 1 year, patients with elevated inflammatory markers, and patients with obesity.20

Our study confirms several factors for severe COVID-19 found in these studies, including older age,11,12,20 obesity,20 and preexisting conditions.11 Our findings also expand on these reports, including identification of factors associated with hospitalization. Given the rate of 30-day re-encounters among pediatric patients with COVID-19 (10.1%), identifying risk factors for hospitalization may aid ED providers in determining optimal disposition (eg, home, hospital admission, ICU). We also identified specific comorbidities associated with more severe disease in those hospitalized with COVID-19, such as cardiovascular disease, obesity/type 2 DM, and pulmonary, neurologic, or neuromuscular conditions. We also found that asthma increased the risk for hospitalization but not more severe disease among those hospitalized. This latter finding also aligns with recent single-center studies,21,22 whereas a Turkish study of pediatric patients aged 0 to 18 years found no association between asthma and COVID-19 hospitalizations.23We also examined payor type and racial/ethnic factors in our analysis. In 2019, patients who identified as Black or Hispanic comprised 52.3% of all encounters and 40.7% of hospitalizations recorded in the PHIS database. During the same year, encounters for influenza among Black or Hispanic pediatric patients comprised 58.7% of all influenza diagnoses and 47.0% of pediatric influenza hospitalizations (Appendix Table 2). In this study, patients who identified as Black or Hispanic race represented a disproportionately large share of patients presenting to children’s hospitals (68.5%) and of those hospitalized (60.8%). Hispanic ethnicity, in particular, represented a disproportionate share of patients seeking care for COVID-19 compared to the overall PHIS population (47.7% and 27.1%, respectively). After accounting for other factors, we found Black and other non-White race—but not of Hispanic ethnicity—were independently associated with more disease severity among those hospitalized. This contrasts with findings from a recent adult study by Yehia et al,24 who found (after adjusting for other clinical factors) no significant difference in mortality between Black patients and White patients among adults hospitalized due to COVID-19. It also contrasts with a recent large population-based UK study wherein pediatric patients identifying as Asian, but not Black or mixed race or ethnicity, had an increased risk of hospital admission and admission to the ICU compared to children identifying as White. Children identifying as Black or mixed race had longer hospital admissions.25 However, as the authors of the study note, residual confounders and ascertainment bias due to differences in COVID testing may have influenced these findings.

Our findings of differences in hospitalization and disease severity among those hospitalized by race and ethnicity should be interpreted carefully. These may reflect a constellation of factors that are difficult to measure, including differences in healthcare access, inequalities in care (including hospital admission inequalities), and implicit bias—all of which may reflect structural racism. For example, it is possible that children who identify as Black or Hispanic have different access to care compared to children who identify as White, and this may affect disease severity on presentation.2 Alternatively, it is possible that White pediatric patients are more likely to be hospitalized as compared to non-White pediatric patients with similar illness severity. Our finding that pediatric patients who identify as Hispanic or Black had a lower risk of hospitalization should be also interpreted carefully, as this may reflect higher utilization of the ED for SARS-CoV-2 testing, increased use of nonemergency services among those without access to primary care, or systematic differences in provider decision-making among this segment of the population.2 Further study is needed to determine specific drivers for racial and ethnic differences in healthcare utilization in children and adolescents with COVID-19.26

Complications and co-occurring diagnoses in adults with COVID-19 are well documented.27-30 However, there is little information to date on the co-occurring diagnoses and complications associated with COVID-19 in children and adolescents. We found that complications and co-occurring conditions occurred in 16.3% of the study population, with the most frequent conditions including known complications of viral infections such as pneumonia, respiratory failure, and seizures. Acute kidney and liver injury, as well as thrombotic complications, occurred less commonly than in adults.26-29 Interestingly, neurologic complications were also uncommon compared to adult reports8,31 and less frequent than in other viral illnesses in children and adolescents. For example, neurologic complications occur in approximately 7.5% of children and adolescents hospitalized with influenza.32

Limitations of the present study include the retrospective design, as well as incomplete patient-level clinical data in the PHIS database. The PHIS database only includes children’s hospitals, which may limit the generalizability of findings to community hospitals. We also excluded newborns, and our findings may not be generalizable to this population. We only included children and adolescents with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19, which has the potential for misclassification in cases where COVID-19 was a secondary diagnosis. However, results of our sensitivity analysis, which incorporated secondary diagnoses of COVID-19, were consistent with findings from our main analyses. Our study was designed to examine associations between certain prespecified factors and COVID-19 severity among pediatric patients who visited the ED or were admitted to the hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, our findings must be interpreted in light of these considerations and may not be generalizable outside the ED or hospital setting. For example, it could be that some segments of the population utilized ED resources for testing, whereas others avoided the ED and other healthcare settings for fear of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. We also relied on diagnosis codes to identify concurrent diagnoses, as well as mechanical ventilation in our very severe outcome cohort, which resulted in this classification for some of these diagnoses. Despite these limitations, our findings represent an important step in understanding the risk factors associated with severe clinical COVID-19 disease in pediatric patients.

Our findings may inform future research and clinical interventions. Future studies on antiviral therapies and immune modulators targeting SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents should focus on high-risk populations, such as those identified in the study, as these patients are most likely to benefit from therapeutic interventions. Similarly, vaccine-development efforts may benefit from additional evaluation in high-risk populations, some of which may have altered immune responses. Furthermore, with increasing vaccination among adults and changes in recommendations, societal mitigation efforts (eg, masking, physical distancing) will diminish. Continued vigilance and COVID-19–mitigation efforts among high-risk children, for whom vaccines are not yet available, are critical during this transition.

CONCLUSION

Among children with COVID-19 who received care at children’s hospitals and EDs, 20% were hospitalized, and, of those, 21% were admitted to the ICU. Older children and adolescent patients had a lower risk of hospitalization; however, when hospitalized, they had greater illness severity. Those with selected comorbidities (eg, cardiovascular, obesity/type 2 DM, pulmonary and neurologic or neuromuscular disease) had both increased odds of hospitalization and in-hospital illness severity. While there were observed differences in COVID-19 severity by race and ethnicity, additional research is needed to clarify the drivers of such disparities. These factors should be considered when prioritizing mitigation strategies to prevent infection (eg, remote learning, avoidance of group activities, prioritization of COVID-19 vaccine when approved for children aged <12 years).

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

2. Levy C, Basmaci R, Bensaid P, et al. Changes in reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction-positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 rates in adults and children according to the epidemic stages. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(11):e369-e372. https://doi.org/10.1097/inf.0000000000002861

3. Gudbjartsson DF, Helgason A, Jonsson H, et al. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic population. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2302-2315. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2006100

4. Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 - COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):458-464. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3

5. Castagnoli R, Votto M, Licari A, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(9):882-889. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467

6. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et al; Overcoming COVID-19 Investigators; CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):334-346. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2021680

7. Magro B, Zuccaro V, Novelli L, et al. Predicting in-hospital mortality from coronavirus disease 2019: a simple validated app for clinical use. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245281. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245281

8. Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2268-2270. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2008597

9. Severe Covid GWAS Group; Ellinghaus D, Degenhardt F, Bujanda L, et al. Genomewide association study of severe Covid-19 with respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(16):1522-1534.

10. Kabarriti R, Brodin NP, Maron MI, et al. association of race and ethnicity with comorbidities and survival among patients with COVID-19 at an urban medical center in New York. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019795. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19795

11. Bellino S, Punzo O, Rota MC, et al; COVID-19 Working Group. COVID-19 disease severity risk factors for pediatric patients in Italy. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020009399. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-009399

12. Ouldali N, Yang DD, Madhi F, et al; investigator group of the PANDOR study. Factors associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatrics. 2020;147(3):e2020023432. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-023432

13. Castells MC, Phillips EJ. Maintaining safety with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(7):643-649. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra2035343

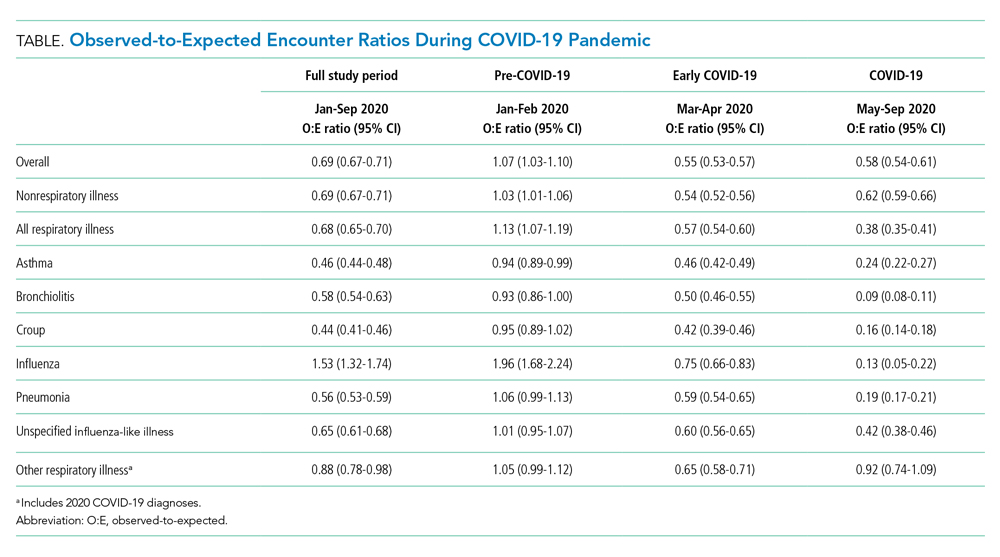

14. Antoon JW, Williams DJ, Thurm C, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and changes in healthcare utilization for pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(5):294-297. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3608

15. Blatz AM, David MZ, Otto WR, Luan X, Gerber JS. Validation of International Classification of Disease-10 code for identifying children hospitalized with coronavirus disease-2019. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020;10(4):547-548. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piaa140

16. Kadri SS, Gundrum J, Warner S, et al. Uptake and accuracy of the diagnosis code for COVID-19 among US hospitalizations. JAMA. 2020;324(24):2553-2554. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.20323

17. Kaiser SV, Rodean J, Bekmezian A, et al; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network. Effectiveness of pediatric asthma pathways for hospitalized children: a multicenter, national analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;197:165-171.e162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.084

18. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-199.

19. Williams DJ, Zhu Y, Grijalva CG, et al. Predicting severe pneumonia outcomes in children. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4):e20161019. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1019

20. Zachariah P, Johnson CL, Halabi KC, et al. Epidemiology, clinical features, and disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a children’s hospital in New York City, New York. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(10):e202430. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2430

21. DeBiasi RL, Song X, Delaney M, et al. Severe coronavirus disease-2019 in children and young adults in the Washington, DC, metropolitan region. J Pediatr. 2020;223:199-203.e191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007

22. Lovinsky-Desir S, Deshpande DR, De A, et al. Asthma among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and related outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(5):1027-1034.e1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.026

23. Beken B, Ozturk GK, Aygun FD, Aydogmus C, Akar HH. Asthma and allergic diseases are not risk factors for hospitalization in children with coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(5):569-575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2021.01.018

24. Yehia BR, Winegar A, Fogel R, et al. Association of race with mortality among patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at 92 US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2018039. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18039

25. Saatci D, Ranger TA, Garriga C, et al. Association between race and COVID-19 outcomes among 2.6 million children in England. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;e211685. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1685

26. Lopez L, 3rd, Hart LH, 3rd, Katz MH. Racial and ethnic health disparities related to COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(8):719-720. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.26443

27. Altunok ES, Alkan M, Kamat S, et al. Clinical characteristics of adult patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia. J Infect Chemother. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2020.10.020

28. Ali H, Daoud A, Mohamed MM, et al. Survival rate in acute kidney injury superimposed COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail. 2020;42(1):393-397. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886022x.2020.1756323

29. Anirvan P, Bharali P, Gogoi M, Thuluvath PJ, Singh SP, Satapathy SK. Liver injury in COVID-19: the hepatic aspect of the respiratory syndrome - what we know so far. World J Hepatol. 2020;12(12):1182-1197. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i12.1182

30. Moschonas IC, Tselepis AD. SARS-CoV-2 infection and thrombotic complications: a narrative review. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;52(1):111-123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-020-02374-3

31. Lee MH, Perl DP, Nair G, et al. Microvascular injury in the brains of patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;384(5):481-483. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2033369

32. Antoon JW, Hall M, Herndon A, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of influenza-associated neurological Complications in Children. J Pediatr. 2021;S0022-3476(21)00657-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.06.075

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to more than 40 million infections and more than 650,000 deaths in the United States alone.1 Morbidity and mortality have disproportionately affected older adults.2-4 However, acute infection and delayed effects, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), occur and can lead to severe complications, hospitalization, and death in pediatric patients.5,6 Due to higher clinical disease prevalence and morbidity in the adult population, we have learned much about the clinical factors associated with severe adult COVID-19 disease.5,7-9 Such clinical factors include older age, concurrent comorbidities, smoke exposure, and Black race or Hispanic ethnicity, among others.5,7-10 However, there is a paucity of data on severe COVID-19 disease in pediatric patients.5,11,12 In addition, most immunization strategies and pharmacologic treatments for COVID-19 have not been evaluated or approved for use in children.13 To guide targeted prevention and treatment strategies, there is a critical need to identify children and adolescents—who are among the most vulnerable patient populations—at high risk for severe disease.

Identifying the clinical factors associated with severe COVID-19 disease will help with prioritizing and allocating vaccines when they are approved for use in patients younger than 12 years.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study of patients presenting for care at pediatric hospitals that report data to the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database. The PHIS administrative database includes billing and utilization data from 45 US tertiary care hospitals affiliated with the Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, Kansas). Data quality and reliability are ensured through a joint validation effort between the Children’s Hospital Association and participating hospitals. Hospitals submit discharge data, including demographics, diagnoses, and procedures using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes, along with daily detailed information on pharmacy, location of care, and other services.

Study Population

Patients 30 days to 18 years of age discharged from the emergency department (ED) or inpatient setting with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19 (ICD-10 codes U.071 and U.072) between April 1, 2020, and September 30, 2020, were eligible for inclusion.14 In a prior study, the positive predictive value of an ICD-10–coded diagnosis of COVID-19 among hospitalized pediatric patients was 95.5%, compared with reverse transcription polymerase reaction results or presence of MIS-C.15 The diagnostic code for COVID-19 (ICD-10-CM) also had a high sensitivity (98.0%) in the hospitalized population.16 Acknowledging the increasing practice of screening patients upon admission, and in an attempt to minimize potential misclassification, we did not include encounters with secondary diagnoses of COVID-19 in our primary analyses. Pediatric patients with surgical diagnoses and neonates who never left the hospital were also excluded.

Factors Associated With Severe COVID-19 Disease

Exposures of interest were determined a priori based on current evidence in the literature and included patient age (0-4 years, 5-11 years, and 12-18 years), sex, race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, other non-White race [defined as Pacific Islander, Native American, or other]), payor type, cardiovascular complex chronic conditions (CCC), neuromuscular CCC, obesity/type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), pulmonary CCC, asthma (defined using ICD-10 codes17), and immunocompromised CCC

Pediatric Complications and Conditions Associated With COVID-19

Based on current evidence and expert opinion of study members, associated diagnoses and complications co-occurring with a COVID-19 diagnosis were defined a priori and identified through ICD-10 codes (Appendix Table 1). These included acute kidney injury, acute liver injury, aseptic meningitis, asthma exacerbation, bronchiolitis, cerebral infarction, croup, encephalitis, encephalopathy, infant fever, febrile seizure, gastroenteritis/dehydration, Kawasaki disease/MIS-C, myocarditis/pericarditis, pneumonia, lung effusion or empyema, respiratory failure, sepsis, nonfebrile seizure, pancreatitis, sickle cell complications, and thrombotic complications.

Outcomes

COVID-19 severity outcomes were assessed as follows: (1) mild = ED discharge; (2) moderate = inpatient admission; (3) severe = intensive care unit (ICU) admission without mechanical ventilation, shock, or death; and (4) very severe = ICU admission with mechanical ventilation, shock, or death.19 This ordinal ranking system did not violate the proportional odds assumption. Potential reasons for admission to the ICU without mechanical ventilation, shock, or death include, but are not limited to, need for noninvasive ventilation, vital sign instability, dysrhythmias, respiratory insufficiency, or complications arising from concurrent conditions (eg, thrombotic events, need for continuous albuterol therapy). We examined several secondary, hospital-based outcomes, including associated diagnoses and complications, all-cause 30-day healthcare reutilization (ED visit or rehospitalization), length of stay (LOS), and ICU LOS.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics were summarized using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and geometric means with SD and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables, as appropriate. Factors associated with hospitalization (encompassing severity levels 2-4) vs ED discharge (severity level 1) were assessed using logistic regression. Factors associated with increasing severity among hospitalized pediatric patients (severity levels 2, 3, and 4) were assessed using ordinal logistic regression. Covariates in these analyses included race and ethnicity, age, sex, payor, cardiovascular CCC, neurologic/neuromuscular CCC, obesity/type 2 DM, pulmonary CCC, asthma, and immunocompromised CCC. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and corresponding 95% CI for each risk factor were generated using generalized linear mixed effects models and random intercepts for each hospital. Given the potential for diagnostic misclassification of pediatric patients with COVID-19 based on primary vs secondary diagnoses, we performed sensitivity analyses defining the study population as those with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19 and those with a secondary diagnosis of COVID-19 plus a concurrent primary diagnosis of a condition associated with COVID-19 (Appendix Table 1).

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc), and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. The Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center determined that this study of de-identified data did not meet the criteria for human subjects research.

RESULTS

Study Population

A total of 19,976 encounters were included in the study. Of those, 15,913 (79.7%) were discharged from the ED and 4063 (20.3%) were hospitalized (Table 1). The most common race/ethnicity was Hispanic (9741, 48.8%), followed by non-Hispanic White (4217, 21.1%). Reference race/ethnicity data for the overall 2019 PHIS population can be found in Appendix Table 2.

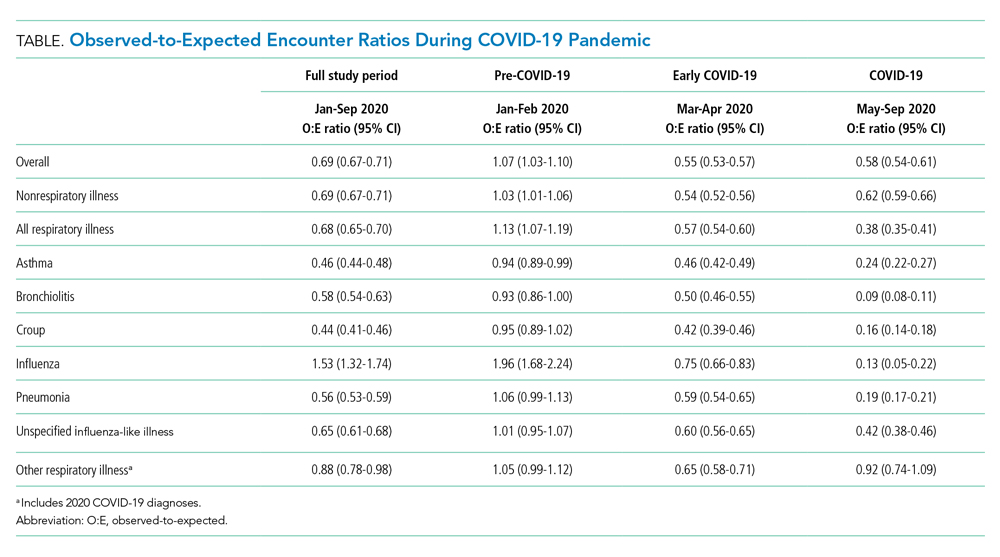

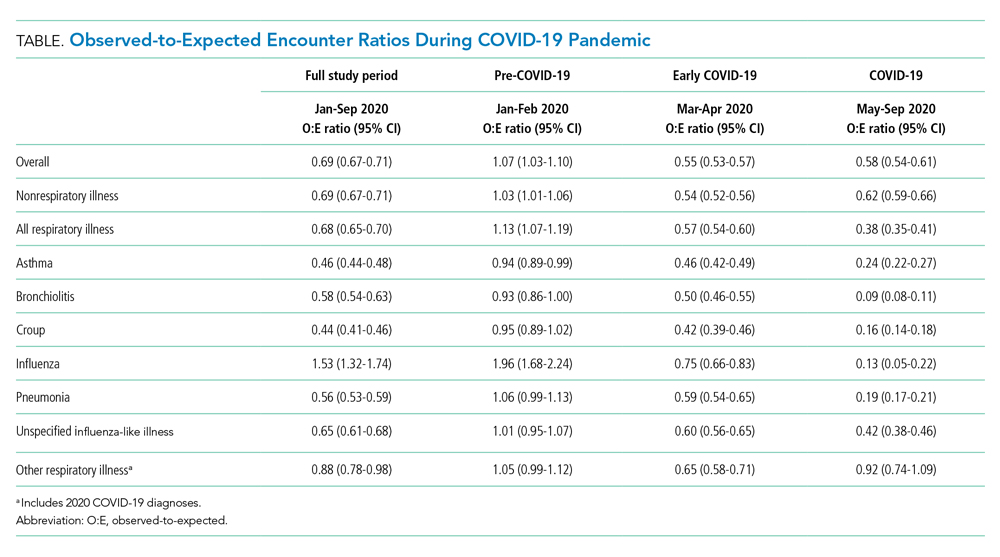

The severity distribution among the hospitalized population was moderate (3222, 79.3%), severe (431, 11.3%), and very severe (380, 9.4%). The frequency of COVID-19 diagnoses increased late in the study period (Figure). Among those hospitalized, the median LOS for the index admission was 2 days (IQR, 1-4), while among those admitted to the ICU, the median LOS was 3 days (IQR, 2-5).

Overall, 10.1% (n = 2020) of the study population had an all-cause repeat encounter (ie, subsequent ED encounter or hospitalization) within 30 days following the index discharge. Repeat encounters were more frequent among patients hospitalized than among those discharged from the ED (Appendix Table 3).

Prevalence of Conditions and Complications Associated With COVID-19

Overall, 3257 (16.3%) patients had one or more co-occurring diagnoses categorized as a COVID-19–associated condition or complication. The most frequent diagnoses included lower respiratory tract disease (pneumonia, lung effusion, or empyema; n = 1415, 7.1%), gastroenteritis/dehydration (n = 1068, 5.3%), respiratory failure (n = 731, 3.7%), febrile infant (n = 413, 2.1%), and nonfebrile seizure (n = 425, 2.1%). Aside from nonfebrile seizure, neurological complications were less frequent and included febrile seizure (n = 155, 0.8%), encephalopathy (n = 63, 0.3%), aseptic meningitis (n = 16, 0.1%), encephalitis (n = 11, 0.1%), and cerebral infarction (n = 6, <0.1%). Kawasaki disease and MIS-C comprised 1.7% (n = 346) of diagnoses. Thrombotic complications occurred in 0.1% (n = 13) of patients. Overall, these conditions and complications associated with COVID-19 were more frequent in hospitalized patients than in those discharged from the ED (P < .001) (Table 2).

Factors Associated With COVID-19 Disease Severity

Compared to pediatric patients with COVID-19 discharged from the ED, factors associated with increased odds of hospitalization included private payor insurance; obesity/type 2 DM; asthma; and cardiovascular, immunocompromised, neurologic/neuromuscular, and pulmonary CCCs (Table 3). Factors associated with decreased risk of hospitalization included Black race or Hispanic ethnicity compared with White race; female sex; and age 5 to 11 years and age 12 to 17 years (vs age 0-4 years). Among children and adolescents hospitalized with COVID-19, factors associated with greater disease severity included Black or other non-White race; age 5 to 11 years; age 12 to 17 years; obesity/type 2 DM; immunocompromised conditions; and cardiovascular, neurologic/neuromuscular, and pulmonary CCCs (Table 3).

Sensitivity Analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis that expanded the study population to include those with a secondary diagnosis of COVID-19 plus a diagnosis of a COVID-19–associated condition or complication. Analyses using the expanded population (N = 21,247) were similar to the primary analyses (Appendix Table 4 and Appendix Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In this large multicenter study evaluating COVID-19 disease severity in more than 19,000 patients presenting for emergency care at US pediatric hospitals, approximately 20% were hospitalized, and among those hospitalized almost a quarter required ICU care. Clinical risk factors associated with increased risk of hospitalization include private payor status and selected comorbidities (obesity/type 2 DM; asthma; and cardiovascular, pulmonary, immunocompromised, neurologic/neuromuscular CCCs), while those associated with decreased risk of hospitalization include older age, female sex, and Black race or Hispanic ethnicity. Factors associated with severe disease among hospitalized pediatric patients include Black or other non-White race, school age (≥5 years), and certain chronic conditions (cardiovascular disease, obesity/type 2 DM, neurologic or neuromuscular disease). Sixteen percent of patients had a concurrent diagnosis for a condition or complication associated with COVID-19.

While the study population (ie, children and adolescents presenting to the ED) represents a small fraction of children and adolescents in the community with SARS-CoV-2 infection, the results provide important insight into factors of severe COVID-19 in the pediatric population. A report from France suggested ventilatory or hemodynamic support or death were independently associated with older age (≥10 years), elevated C-reactive protein, and hypoxemia.12 An Italian study found that younger age (0-4 years) was associated with less severe disease, while preexisting conditions were more likely in patients with severe disease.11 A single-center case series of 50 patients (aged ≤21 years) hospitalized at a children’s hospital in New York City found respiratory failure (n = 9) was more common in children older than 1 year, patients with elevated inflammatory markers, and patients with obesity.20

Our study confirms several factors for severe COVID-19 found in these studies, including older age,11,12,20 obesity,20 and preexisting conditions.11 Our findings also expand on these reports, including identification of factors associated with hospitalization. Given the rate of 30-day re-encounters among pediatric patients with COVID-19 (10.1%), identifying risk factors for hospitalization may aid ED providers in determining optimal disposition (eg, home, hospital admission, ICU). We also identified specific comorbidities associated with more severe disease in those hospitalized with COVID-19, such as cardiovascular disease, obesity/type 2 DM, and pulmonary, neurologic, or neuromuscular conditions. We also found that asthma increased the risk for hospitalization but not more severe disease among those hospitalized. This latter finding also aligns with recent single-center studies,21,22 whereas a Turkish study of pediatric patients aged 0 to 18 years found no association between asthma and COVID-19 hospitalizations.23We also examined payor type and racial/ethnic factors in our analysis. In 2019, patients who identified as Black or Hispanic comprised 52.3% of all encounters and 40.7% of hospitalizations recorded in the PHIS database. During the same year, encounters for influenza among Black or Hispanic pediatric patients comprised 58.7% of all influenza diagnoses and 47.0% of pediatric influenza hospitalizations (Appendix Table 2). In this study, patients who identified as Black or Hispanic race represented a disproportionately large share of patients presenting to children’s hospitals (68.5%) and of those hospitalized (60.8%). Hispanic ethnicity, in particular, represented a disproportionate share of patients seeking care for COVID-19 compared to the overall PHIS population (47.7% and 27.1%, respectively). After accounting for other factors, we found Black and other non-White race—but not of Hispanic ethnicity—were independently associated with more disease severity among those hospitalized. This contrasts with findings from a recent adult study by Yehia et al,24 who found (after adjusting for other clinical factors) no significant difference in mortality between Black patients and White patients among adults hospitalized due to COVID-19. It also contrasts with a recent large population-based UK study wherein pediatric patients identifying as Asian, but not Black or mixed race or ethnicity, had an increased risk of hospital admission and admission to the ICU compared to children identifying as White. Children identifying as Black or mixed race had longer hospital admissions.25 However, as the authors of the study note, residual confounders and ascertainment bias due to differences in COVID testing may have influenced these findings.

Our findings of differences in hospitalization and disease severity among those hospitalized by race and ethnicity should be interpreted carefully. These may reflect a constellation of factors that are difficult to measure, including differences in healthcare access, inequalities in care (including hospital admission inequalities), and implicit bias—all of which may reflect structural racism. For example, it is possible that children who identify as Black or Hispanic have different access to care compared to children who identify as White, and this may affect disease severity on presentation.2 Alternatively, it is possible that White pediatric patients are more likely to be hospitalized as compared to non-White pediatric patients with similar illness severity. Our finding that pediatric patients who identify as Hispanic or Black had a lower risk of hospitalization should be also interpreted carefully, as this may reflect higher utilization of the ED for SARS-CoV-2 testing, increased use of nonemergency services among those without access to primary care, or systematic differences in provider decision-making among this segment of the population.2 Further study is needed to determine specific drivers for racial and ethnic differences in healthcare utilization in children and adolescents with COVID-19.26

Complications and co-occurring diagnoses in adults with COVID-19 are well documented.27-30 However, there is little information to date on the co-occurring diagnoses and complications associated with COVID-19 in children and adolescents. We found that complications and co-occurring conditions occurred in 16.3% of the study population, with the most frequent conditions including known complications of viral infections such as pneumonia, respiratory failure, and seizures. Acute kidney and liver injury, as well as thrombotic complications, occurred less commonly than in adults.26-29 Interestingly, neurologic complications were also uncommon compared to adult reports8,31 and less frequent than in other viral illnesses in children and adolescents. For example, neurologic complications occur in approximately 7.5% of children and adolescents hospitalized with influenza.32

Limitations of the present study include the retrospective design, as well as incomplete patient-level clinical data in the PHIS database. The PHIS database only includes children’s hospitals, which may limit the generalizability of findings to community hospitals. We also excluded newborns, and our findings may not be generalizable to this population. We only included children and adolescents with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19, which has the potential for misclassification in cases where COVID-19 was a secondary diagnosis. However, results of our sensitivity analysis, which incorporated secondary diagnoses of COVID-19, were consistent with findings from our main analyses. Our study was designed to examine associations between certain prespecified factors and COVID-19 severity among pediatric patients who visited the ED or were admitted to the hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, our findings must be interpreted in light of these considerations and may not be generalizable outside the ED or hospital setting. For example, it could be that some segments of the population utilized ED resources for testing, whereas others avoided the ED and other healthcare settings for fear of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. We also relied on diagnosis codes to identify concurrent diagnoses, as well as mechanical ventilation in our very severe outcome cohort, which resulted in this classification for some of these diagnoses. Despite these limitations, our findings represent an important step in understanding the risk factors associated with severe clinical COVID-19 disease in pediatric patients.

Our findings may inform future research and clinical interventions. Future studies on antiviral therapies and immune modulators targeting SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents should focus on high-risk populations, such as those identified in the study, as these patients are most likely to benefit from therapeutic interventions. Similarly, vaccine-development efforts may benefit from additional evaluation in high-risk populations, some of which may have altered immune responses. Furthermore, with increasing vaccination among adults and changes in recommendations, societal mitigation efforts (eg, masking, physical distancing) will diminish. Continued vigilance and COVID-19–mitigation efforts among high-risk children, for whom vaccines are not yet available, are critical during this transition.

CONCLUSION

Among children with COVID-19 who received care at children’s hospitals and EDs, 20% were hospitalized, and, of those, 21% were admitted to the ICU. Older children and adolescent patients had a lower risk of hospitalization; however, when hospitalized, they had greater illness severity. Those with selected comorbidities (eg, cardiovascular, obesity/type 2 DM, pulmonary and neurologic or neuromuscular disease) had both increased odds of hospitalization and in-hospital illness severity. While there were observed differences in COVID-19 severity by race and ethnicity, additional research is needed to clarify the drivers of such disparities. These factors should be considered when prioritizing mitigation strategies to prevent infection (eg, remote learning, avoidance of group activities, prioritization of COVID-19 vaccine when approved for children aged <12 years).

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to more than 40 million infections and more than 650,000 deaths in the United States alone.1 Morbidity and mortality have disproportionately affected older adults.2-4 However, acute infection and delayed effects, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), occur and can lead to severe complications, hospitalization, and death in pediatric patients.5,6 Due to higher clinical disease prevalence and morbidity in the adult population, we have learned much about the clinical factors associated with severe adult COVID-19 disease.5,7-9 Such clinical factors include older age, concurrent comorbidities, smoke exposure, and Black race or Hispanic ethnicity, among others.5,7-10 However, there is a paucity of data on severe COVID-19 disease in pediatric patients.5,11,12 In addition, most immunization strategies and pharmacologic treatments for COVID-19 have not been evaluated or approved for use in children.13 To guide targeted prevention and treatment strategies, there is a critical need to identify children and adolescents—who are among the most vulnerable patient populations—at high risk for severe disease.

Identifying the clinical factors associated with severe COVID-19 disease will help with prioritizing and allocating vaccines when they are approved for use in patients younger than 12 years.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study of patients presenting for care at pediatric hospitals that report data to the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database. The PHIS administrative database includes billing and utilization data from 45 US tertiary care hospitals affiliated with the Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, Kansas). Data quality and reliability are ensured through a joint validation effort between the Children’s Hospital Association and participating hospitals. Hospitals submit discharge data, including demographics, diagnoses, and procedures using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes, along with daily detailed information on pharmacy, location of care, and other services.

Study Population

Patients 30 days to 18 years of age discharged from the emergency department (ED) or inpatient setting with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19 (ICD-10 codes U.071 and U.072) between April 1, 2020, and September 30, 2020, were eligible for inclusion.14 In a prior study, the positive predictive value of an ICD-10–coded diagnosis of COVID-19 among hospitalized pediatric patients was 95.5%, compared with reverse transcription polymerase reaction results or presence of MIS-C.15 The diagnostic code for COVID-19 (ICD-10-CM) also had a high sensitivity (98.0%) in the hospitalized population.16 Acknowledging the increasing practice of screening patients upon admission, and in an attempt to minimize potential misclassification, we did not include encounters with secondary diagnoses of COVID-19 in our primary analyses. Pediatric patients with surgical diagnoses and neonates who never left the hospital were also excluded.

Factors Associated With Severe COVID-19 Disease

Exposures of interest were determined a priori based on current evidence in the literature and included patient age (0-4 years, 5-11 years, and 12-18 years), sex, race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, other non-White race [defined as Pacific Islander, Native American, or other]), payor type, cardiovascular complex chronic conditions (CCC), neuromuscular CCC, obesity/type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), pulmonary CCC, asthma (defined using ICD-10 codes17), and immunocompromised CCC

Pediatric Complications and Conditions Associated With COVID-19

Based on current evidence and expert opinion of study members, associated diagnoses and complications co-occurring with a COVID-19 diagnosis were defined a priori and identified through ICD-10 codes (Appendix Table 1). These included acute kidney injury, acute liver injury, aseptic meningitis, asthma exacerbation, bronchiolitis, cerebral infarction, croup, encephalitis, encephalopathy, infant fever, febrile seizure, gastroenteritis/dehydration, Kawasaki disease/MIS-C, myocarditis/pericarditis, pneumonia, lung effusion or empyema, respiratory failure, sepsis, nonfebrile seizure, pancreatitis, sickle cell complications, and thrombotic complications.

Outcomes

COVID-19 severity outcomes were assessed as follows: (1) mild = ED discharge; (2) moderate = inpatient admission; (3) severe = intensive care unit (ICU) admission without mechanical ventilation, shock, or death; and (4) very severe = ICU admission with mechanical ventilation, shock, or death.19 This ordinal ranking system did not violate the proportional odds assumption. Potential reasons for admission to the ICU without mechanical ventilation, shock, or death include, but are not limited to, need for noninvasive ventilation, vital sign instability, dysrhythmias, respiratory insufficiency, or complications arising from concurrent conditions (eg, thrombotic events, need for continuous albuterol therapy). We examined several secondary, hospital-based outcomes, including associated diagnoses and complications, all-cause 30-day healthcare reutilization (ED visit or rehospitalization), length of stay (LOS), and ICU LOS.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics were summarized using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and geometric means with SD and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables, as appropriate. Factors associated with hospitalization (encompassing severity levels 2-4) vs ED discharge (severity level 1) were assessed using logistic regression. Factors associated with increasing severity among hospitalized pediatric patients (severity levels 2, 3, and 4) were assessed using ordinal logistic regression. Covariates in these analyses included race and ethnicity, age, sex, payor, cardiovascular CCC, neurologic/neuromuscular CCC, obesity/type 2 DM, pulmonary CCC, asthma, and immunocompromised CCC. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and corresponding 95% CI for each risk factor were generated using generalized linear mixed effects models and random intercepts for each hospital. Given the potential for diagnostic misclassification of pediatric patients with COVID-19 based on primary vs secondary diagnoses, we performed sensitivity analyses defining the study population as those with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19 and those with a secondary diagnosis of COVID-19 plus a concurrent primary diagnosis of a condition associated with COVID-19 (Appendix Table 1).

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc), and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. The Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center determined that this study of de-identified data did not meet the criteria for human subjects research.

RESULTS

Study Population

A total of 19,976 encounters were included in the study. Of those, 15,913 (79.7%) were discharged from the ED and 4063 (20.3%) were hospitalized (Table 1). The most common race/ethnicity was Hispanic (9741, 48.8%), followed by non-Hispanic White (4217, 21.1%). Reference race/ethnicity data for the overall 2019 PHIS population can be found in Appendix Table 2.

The severity distribution among the hospitalized population was moderate (3222, 79.3%), severe (431, 11.3%), and very severe (380, 9.4%). The frequency of COVID-19 diagnoses increased late in the study period (Figure). Among those hospitalized, the median LOS for the index admission was 2 days (IQR, 1-4), while among those admitted to the ICU, the median LOS was 3 days (IQR, 2-5).

Overall, 10.1% (n = 2020) of the study population had an all-cause repeat encounter (ie, subsequent ED encounter or hospitalization) within 30 days following the index discharge. Repeat encounters were more frequent among patients hospitalized than among those discharged from the ED (Appendix Table 3).

Prevalence of Conditions and Complications Associated With COVID-19

Overall, 3257 (16.3%) patients had one or more co-occurring diagnoses categorized as a COVID-19–associated condition or complication. The most frequent diagnoses included lower respiratory tract disease (pneumonia, lung effusion, or empyema; n = 1415, 7.1%), gastroenteritis/dehydration (n = 1068, 5.3%), respiratory failure (n = 731, 3.7%), febrile infant (n = 413, 2.1%), and nonfebrile seizure (n = 425, 2.1%). Aside from nonfebrile seizure, neurological complications were less frequent and included febrile seizure (n = 155, 0.8%), encephalopathy (n = 63, 0.3%), aseptic meningitis (n = 16, 0.1%), encephalitis (n = 11, 0.1%), and cerebral infarction (n = 6, <0.1%). Kawasaki disease and MIS-C comprised 1.7% (n = 346) of diagnoses. Thrombotic complications occurred in 0.1% (n = 13) of patients. Overall, these conditions and complications associated with COVID-19 were more frequent in hospitalized patients than in those discharged from the ED (P < .001) (Table 2).

Factors Associated With COVID-19 Disease Severity

Compared to pediatric patients with COVID-19 discharged from the ED, factors associated with increased odds of hospitalization included private payor insurance; obesity/type 2 DM; asthma; and cardiovascular, immunocompromised, neurologic/neuromuscular, and pulmonary CCCs (Table 3). Factors associated with decreased risk of hospitalization included Black race or Hispanic ethnicity compared with White race; female sex; and age 5 to 11 years and age 12 to 17 years (vs age 0-4 years). Among children and adolescents hospitalized with COVID-19, factors associated with greater disease severity included Black or other non-White race; age 5 to 11 years; age 12 to 17 years; obesity/type 2 DM; immunocompromised conditions; and cardiovascular, neurologic/neuromuscular, and pulmonary CCCs (Table 3).

Sensitivity Analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis that expanded the study population to include those with a secondary diagnosis of COVID-19 plus a diagnosis of a COVID-19–associated condition or complication. Analyses using the expanded population (N = 21,247) were similar to the primary analyses (Appendix Table 4 and Appendix Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In this large multicenter study evaluating COVID-19 disease severity in more than 19,000 patients presenting for emergency care at US pediatric hospitals, approximately 20% were hospitalized, and among those hospitalized almost a quarter required ICU care. Clinical risk factors associated with increased risk of hospitalization include private payor status and selected comorbidities (obesity/type 2 DM; asthma; and cardiovascular, pulmonary, immunocompromised, neurologic/neuromuscular CCCs), while those associated with decreased risk of hospitalization include older age, female sex, and Black race or Hispanic ethnicity. Factors associated with severe disease among hospitalized pediatric patients include Black or other non-White race, school age (≥5 years), and certain chronic conditions (cardiovascular disease, obesity/type 2 DM, neurologic or neuromuscular disease). Sixteen percent of patients had a concurrent diagnosis for a condition or complication associated with COVID-19.

While the study population (ie, children and adolescents presenting to the ED) represents a small fraction of children and adolescents in the community with SARS-CoV-2 infection, the results provide important insight into factors of severe COVID-19 in the pediatric population. A report from France suggested ventilatory or hemodynamic support or death were independently associated with older age (≥10 years), elevated C-reactive protein, and hypoxemia.12 An Italian study found that younger age (0-4 years) was associated with less severe disease, while preexisting conditions were more likely in patients with severe disease.11 A single-center case series of 50 patients (aged ≤21 years) hospitalized at a children’s hospital in New York City found respiratory failure (n = 9) was more common in children older than 1 year, patients with elevated inflammatory markers, and patients with obesity.20

Our study confirms several factors for severe COVID-19 found in these studies, including older age,11,12,20 obesity,20 and preexisting conditions.11 Our findings also expand on these reports, including identification of factors associated with hospitalization. Given the rate of 30-day re-encounters among pediatric patients with COVID-19 (10.1%), identifying risk factors for hospitalization may aid ED providers in determining optimal disposition (eg, home, hospital admission, ICU). We also identified specific comorbidities associated with more severe disease in those hospitalized with COVID-19, such as cardiovascular disease, obesity/type 2 DM, and pulmonary, neurologic, or neuromuscular conditions. We also found that asthma increased the risk for hospitalization but not more severe disease among those hospitalized. This latter finding also aligns with recent single-center studies,21,22 whereas a Turkish study of pediatric patients aged 0 to 18 years found no association between asthma and COVID-19 hospitalizations.23We also examined payor type and racial/ethnic factors in our analysis. In 2019, patients who identified as Black or Hispanic comprised 52.3% of all encounters and 40.7% of hospitalizations recorded in the PHIS database. During the same year, encounters for influenza among Black or Hispanic pediatric patients comprised 58.7% of all influenza diagnoses and 47.0% of pediatric influenza hospitalizations (Appendix Table 2). In this study, patients who identified as Black or Hispanic race represented a disproportionately large share of patients presenting to children’s hospitals (68.5%) and of those hospitalized (60.8%). Hispanic ethnicity, in particular, represented a disproportionate share of patients seeking care for COVID-19 compared to the overall PHIS population (47.7% and 27.1%, respectively). After accounting for other factors, we found Black and other non-White race—but not of Hispanic ethnicity—were independently associated with more disease severity among those hospitalized. This contrasts with findings from a recent adult study by Yehia et al,24 who found (after adjusting for other clinical factors) no significant difference in mortality between Black patients and White patients among adults hospitalized due to COVID-19. It also contrasts with a recent large population-based UK study wherein pediatric patients identifying as Asian, but not Black or mixed race or ethnicity, had an increased risk of hospital admission and admission to the ICU compared to children identifying as White. Children identifying as Black or mixed race had longer hospital admissions.25 However, as the authors of the study note, residual confounders and ascertainment bias due to differences in COVID testing may have influenced these findings.

Our findings of differences in hospitalization and disease severity among those hospitalized by race and ethnicity should be interpreted carefully. These may reflect a constellation of factors that are difficult to measure, including differences in healthcare access, inequalities in care (including hospital admission inequalities), and implicit bias—all of which may reflect structural racism. For example, it is possible that children who identify as Black or Hispanic have different access to care compared to children who identify as White, and this may affect disease severity on presentation.2 Alternatively, it is possible that White pediatric patients are more likely to be hospitalized as compared to non-White pediatric patients with similar illness severity. Our finding that pediatric patients who identify as Hispanic or Black had a lower risk of hospitalization should be also interpreted carefully, as this may reflect higher utilization of the ED for SARS-CoV-2 testing, increased use of nonemergency services among those without access to primary care, or systematic differences in provider decision-making among this segment of the population.2 Further study is needed to determine specific drivers for racial and ethnic differences in healthcare utilization in children and adolescents with COVID-19.26

Complications and co-occurring diagnoses in adults with COVID-19 are well documented.27-30 However, there is little information to date on the co-occurring diagnoses and complications associated with COVID-19 in children and adolescents. We found that complications and co-occurring conditions occurred in 16.3% of the study population, with the most frequent conditions including known complications of viral infections such as pneumonia, respiratory failure, and seizures. Acute kidney and liver injury, as well as thrombotic complications, occurred less commonly than in adults.26-29 Interestingly, neurologic complications were also uncommon compared to adult reports8,31 and less frequent than in other viral illnesses in children and adolescents. For example, neurologic complications occur in approximately 7.5% of children and adolescents hospitalized with influenza.32

Limitations of the present study include the retrospective design, as well as incomplete patient-level clinical data in the PHIS database. The PHIS database only includes children’s hospitals, which may limit the generalizability of findings to community hospitals. We also excluded newborns, and our findings may not be generalizable to this population. We only included children and adolescents with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19, which has the potential for misclassification in cases where COVID-19 was a secondary diagnosis. However, results of our sensitivity analysis, which incorporated secondary diagnoses of COVID-19, were consistent with findings from our main analyses. Our study was designed to examine associations between certain prespecified factors and COVID-19 severity among pediatric patients who visited the ED or were admitted to the hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, our findings must be interpreted in light of these considerations and may not be generalizable outside the ED or hospital setting. For example, it could be that some segments of the population utilized ED resources for testing, whereas others avoided the ED and other healthcare settings for fear of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. We also relied on diagnosis codes to identify concurrent diagnoses, as well as mechanical ventilation in our very severe outcome cohort, which resulted in this classification for some of these diagnoses. Despite these limitations, our findings represent an important step in understanding the risk factors associated with severe clinical COVID-19 disease in pediatric patients.

Our findings may inform future research and clinical interventions. Future studies on antiviral therapies and immune modulators targeting SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents should focus on high-risk populations, such as those identified in the study, as these patients are most likely to benefit from therapeutic interventions. Similarly, vaccine-development efforts may benefit from additional evaluation in high-risk populations, some of which may have altered immune responses. Furthermore, with increasing vaccination among adults and changes in recommendations, societal mitigation efforts (eg, masking, physical distancing) will diminish. Continued vigilance and COVID-19–mitigation efforts among high-risk children, for whom vaccines are not yet available, are critical during this transition.

CONCLUSION

Among children with COVID-19 who received care at children’s hospitals and EDs, 20% were hospitalized, and, of those, 21% were admitted to the ICU. Older children and adolescent patients had a lower risk of hospitalization; however, when hospitalized, they had greater illness severity. Those with selected comorbidities (eg, cardiovascular, obesity/type 2 DM, pulmonary and neurologic or neuromuscular disease) had both increased odds of hospitalization and in-hospital illness severity. While there were observed differences in COVID-19 severity by race and ethnicity, additional research is needed to clarify the drivers of such disparities. These factors should be considered when prioritizing mitigation strategies to prevent infection (eg, remote learning, avoidance of group activities, prioritization of COVID-19 vaccine when approved for children aged <12 years).

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

2. Levy C, Basmaci R, Bensaid P, et al. Changes in reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction-positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 rates in adults and children according to the epidemic stages. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(11):e369-e372. https://doi.org/10.1097/inf.0000000000002861

3. Gudbjartsson DF, Helgason A, Jonsson H, et al. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic population. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2302-2315. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2006100

4. Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 - COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):458-464. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3

5. Castagnoli R, Votto M, Licari A, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(9):882-889. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467

6. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et al; Overcoming COVID-19 Investigators; CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):334-346. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2021680

7. Magro B, Zuccaro V, Novelli L, et al. Predicting in-hospital mortality from coronavirus disease 2019: a simple validated app for clinical use. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245281. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245281

8. Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2268-2270. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2008597

9. Severe Covid GWAS Group; Ellinghaus D, Degenhardt F, Bujanda L, et al. Genomewide association study of severe Covid-19 with respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(16):1522-1534.

10. Kabarriti R, Brodin NP, Maron MI, et al. association of race and ethnicity with comorbidities and survival among patients with COVID-19 at an urban medical center in New York. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019795. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19795

11. Bellino S, Punzo O, Rota MC, et al; COVID-19 Working Group. COVID-19 disease severity risk factors for pediatric patients in Italy. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020009399. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-009399

12. Ouldali N, Yang DD, Madhi F, et al; investigator group of the PANDOR study. Factors associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatrics. 2020;147(3):e2020023432. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-023432

13. Castells MC, Phillips EJ. Maintaining safety with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(7):643-649. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra2035343

14. Antoon JW, Williams DJ, Thurm C, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and changes in healthcare utilization for pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(5):294-297. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3608

15. Blatz AM, David MZ, Otto WR, Luan X, Gerber JS. Validation of International Classification of Disease-10 code for identifying children hospitalized with coronavirus disease-2019. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020;10(4):547-548. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piaa140

16. Kadri SS, Gundrum J, Warner S, et al. Uptake and accuracy of the diagnosis code for COVID-19 among US hospitalizations. JAMA. 2020;324(24):2553-2554. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.20323

17. Kaiser SV, Rodean J, Bekmezian A, et al; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network. Effectiveness of pediatric asthma pathways for hospitalized children: a multicenter, national analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;197:165-171.e162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.084

18. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-199.

19. Williams DJ, Zhu Y, Grijalva CG, et al. Predicting severe pneumonia outcomes in children. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4):e20161019. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1019

20. Zachariah P, Johnson CL, Halabi KC, et al. Epidemiology, clinical features, and disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a children’s hospital in New York City, New York. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(10):e202430. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2430

21. DeBiasi RL, Song X, Delaney M, et al. Severe coronavirus disease-2019 in children and young adults in the Washington, DC, metropolitan region. J Pediatr. 2020;223:199-203.e191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007

22. Lovinsky-Desir S, Deshpande DR, De A, et al. Asthma among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and related outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(5):1027-1034.e1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.026

23. Beken B, Ozturk GK, Aygun FD, Aydogmus C, Akar HH. Asthma and allergic diseases are not risk factors for hospitalization in children with coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(5):569-575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2021.01.018

24. Yehia BR, Winegar A, Fogel R, et al. Association of race with mortality among patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at 92 US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2018039. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18039

25. Saatci D, Ranger TA, Garriga C, et al. Association between race and COVID-19 outcomes among 2.6 million children in England. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;e211685. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1685

26. Lopez L, 3rd, Hart LH, 3rd, Katz MH. Racial and ethnic health disparities related to COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(8):719-720. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.26443

27. Altunok ES, Alkan M, Kamat S, et al. Clinical characteristics of adult patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia. J Infect Chemother. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2020.10.020

28. Ali H, Daoud A, Mohamed MM, et al. Survival rate in acute kidney injury superimposed COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail. 2020;42(1):393-397. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886022x.2020.1756323

29. Anirvan P, Bharali P, Gogoi M, Thuluvath PJ, Singh SP, Satapathy SK. Liver injury in COVID-19: the hepatic aspect of the respiratory syndrome - what we know so far. World J Hepatol. 2020;12(12):1182-1197. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i12.1182

30. Moschonas IC, Tselepis AD. SARS-CoV-2 infection and thrombotic complications: a narrative review. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;52(1):111-123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-020-02374-3

31. Lee MH, Perl DP, Nair G, et al. Microvascular injury in the brains of patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;384(5):481-483. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2033369

32. Antoon JW, Hall M, Herndon A, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of influenza-associated neurological Complications in Children. J Pediatr. 2021;S0022-3476(21)00657-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.06.075

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

2. Levy C, Basmaci R, Bensaid P, et al. Changes in reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction-positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 rates in adults and children according to the epidemic stages. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(11):e369-e372. https://doi.org/10.1097/inf.0000000000002861

3. Gudbjartsson DF, Helgason A, Jonsson H, et al. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic population. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2302-2315. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2006100

4. Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 - COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):458-464. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3

5. Castagnoli R, Votto M, Licari A, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(9):882-889. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467

6. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et al; Overcoming COVID-19 Investigators; CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):334-346. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2021680

7. Magro B, Zuccaro V, Novelli L, et al. Predicting in-hospital mortality from coronavirus disease 2019: a simple validated app for clinical use. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245281. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245281

8. Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2268-2270. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2008597

9. Severe Covid GWAS Group; Ellinghaus D, Degenhardt F, Bujanda L, et al. Genomewide association study of severe Covid-19 with respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(16):1522-1534.

10. Kabarriti R, Brodin NP, Maron MI, et al. association of race and ethnicity with comorbidities and survival among patients with COVID-19 at an urban medical center in New York. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019795. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19795

11. Bellino S, Punzo O, Rota MC, et al; COVID-19 Working Group. COVID-19 disease severity risk factors for pediatric patients in Italy. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020009399. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-009399

12. Ouldali N, Yang DD, Madhi F, et al; investigator group of the PANDOR study. Factors associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatrics. 2020;147(3):e2020023432. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-023432

13. Castells MC, Phillips EJ. Maintaining safety with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(7):643-649. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra2035343

14. Antoon JW, Williams DJ, Thurm C, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and changes in healthcare utilization for pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(5):294-297. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3608