User login

Duration of Adalimumab Therapy in Hidradenitis Suppurativa With and Without Oral Immunosuppressants

To the Editor:

The tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Although 50.6% of patients fulfilled Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response criteria with adalimumab at 12 weeks, many responders were not satisfied with their disease control, and secondary loss of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response fulfillment occurred in 15.9% of patients within approximately 3 years.1 Without other US Food and Drug Administration–approved HS treatments, some dermatologists have combined adalimumab with methotrexate (MTX) and/or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to attempt to increase the duration of satisfactory disease control while on adalimumab. Combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants is a well-established approach in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease; however, to the best of our knowledge, this approach has not been studied for HS.2,3

To assess whether there is a role for combining adalimumab with MTX and/or MMF in the treatment of HS, we performed a single-institution retrospective chart review at the University of Connecticut Department of Dermatology to determine whether patients receiving combination therapy stayed on adalimumab longer than those who received adalimumab monotherapy. All patients receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS with at least 1 follow-up visit 3 or more months after treatment initiation were included. Duration of treatment with adalimumab was defined as the length of time between initiation and termination of adalimumab, regardless of flares, adverse events, or addition of adjuvant therapy that occurred during this time span. Because standardized rating scales measuring the severity of HS at this time are not recorded routinely at our institution, treatment duration with adalimumab was used as a surrogate for measuring therapeutic success. Additionally, treatment duration is a meaningful end point, as patients with HS may require indefinite treatment. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS. Patients were excluded if they were lost to follow-up or had received adalimumab for less than 6 months, as data suggest that biologics do not reach peak effect for up to 6 months in HS.4

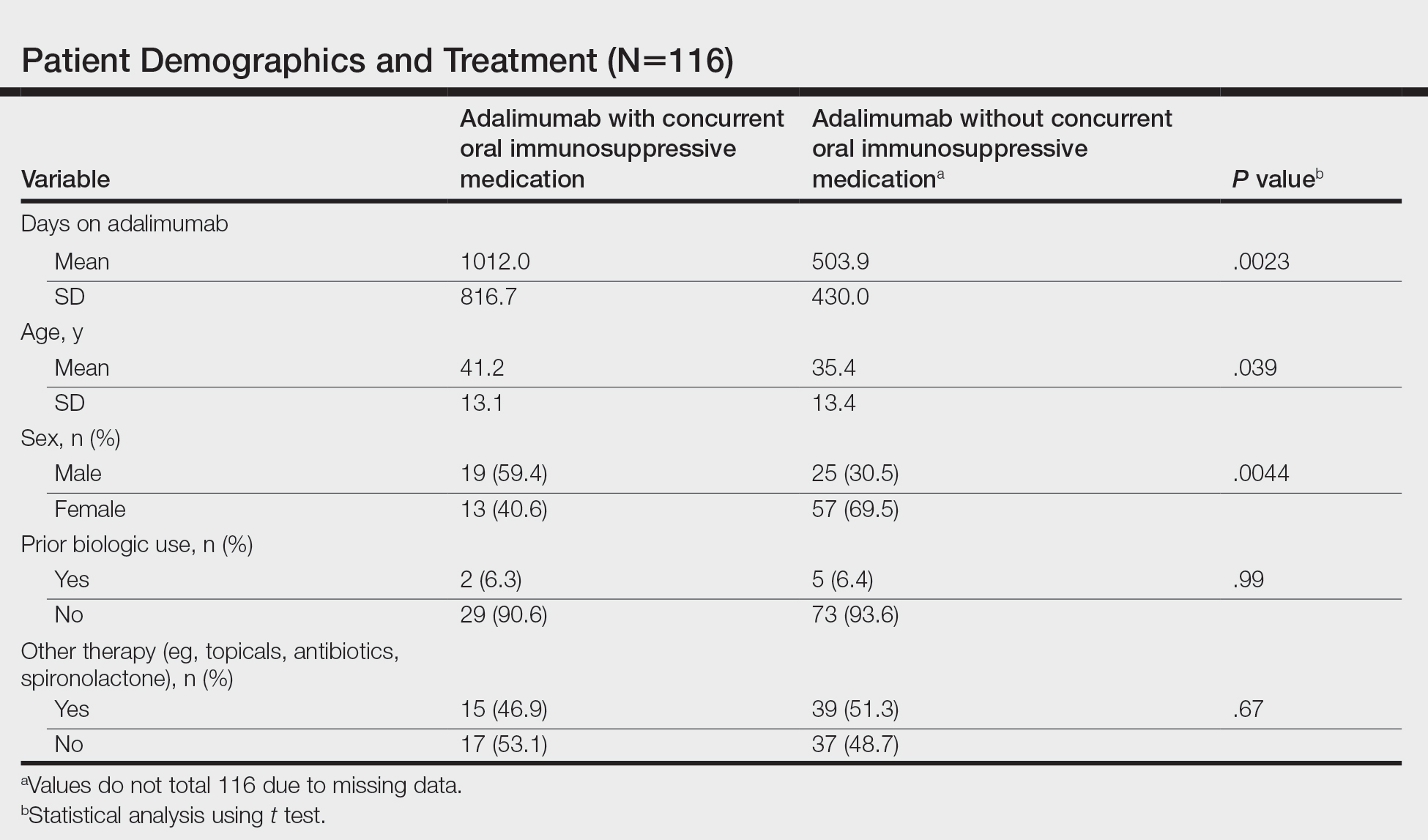

We identified 116 eligible patients with HS, 32 of whom received combination therapy. Five patients received 40 mg of adalimumab every other week, and 111 patients received 40 mg of adalimumab each week. Patients receiving oral immunosuppressants were more likely to be male and as likely to be biologic naïve compared to patients on monotherapy (Table). The average weekly dose of MTX was 14.63 mg, and the average daily dose of MMF was 1000 mg. The average number of days between starting adalimumab and starting an oral immunosuppressant was 114.5 (SD, 217; median, 0) days. Reasons for discontinuation of adalimumab included insufficient response, noncompliance, dislike of injections, adverse events, fear of adverse events, other medical issues unrelated to HS, and insurance coverage issues. Patients who ended treatment with adalimumab owing to insurance coverage issues were still included in our study because insurance coverage remains a major determinant of treatment choice in HS and is relevant to the dynamics of medical decision-making.

Statistical analysis was conducted on all patients inclusive of any reason for discontinuation to avoid bias in the calculation of treatment duration. Cox regression analysis was conducted for all independent variables and was noncontributory. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to assess the duration of treatment of adalimumab with and without concomitant oral immunosuppressants, and quartile survival times were calculated. Quartile survival time is the time point after adalimumab initiation at which 25% of patients have discontinued adalimumab. We chose quartile survival time instead of average treatment duration to adequately power this study, given our small patient pool.

Although patients receiving adalimumab with oral immunosuppressants had a longer quartile treatment duration (450 days; 95% CI, 185-1800) than the group without oral immunosuppressants (360 days; 95% CI, 200-700), neither MTX nor MMF was shown to significantly prolong duration of therapy with adalimumab (log-rank test: P=.12). Additionally, patients receiving combination therapy were just as likely to discontinue adalimumab as those on monotherapy (χ2 test: P=.93). Patients who took both MTX and MMF at different times did show a statistically significant increase in adalimumab quartile treatment duration (1710 days; 95% CI, 1620 [upper limit not calculable]), but this is likely because these patients were kept on adalimumab while trialing adjunctive medications.

The results of our study indicate that MTX and MMF do not prolong duration of adalimumab therapy, which suggests that adalimumab combination therapy with MTX and MMF may not improve HS more than adalimumab alone, and/or partial responders to adalimumab monotherapy are unlikely to be converted to satisfactory responders with the addition of oral immunosuppressants. Limitations of our study include that it was retrospective, used treatment duration as a surrogate for objective efficacy measures, and relied on a single-institution data source. Additionally, owing to our small sample size, we were unable to account for certain potential confounders, including patient weight and insurance status. Future controlled prospective studies using objective end points are needed to further elucidate whether oral immunosuppressants have a role as an adjunct in the treatment of HS.

- Zouboulis CC, Okun MM, Prens EP, et al. Long-term adalimumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: 3-year results of a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:60-69.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.040

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Sultan KS, Berkowitz JC, Khan S. Combination therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8:103-113. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i2.103

- Prussick L, Rothstein B, Joshipura D, et al. Open-label, investigator-initiated, single-site exploratory trial evaluating secukinumab, an anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, for patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:609-611.

To the Editor:

The tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Although 50.6% of patients fulfilled Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response criteria with adalimumab at 12 weeks, many responders were not satisfied with their disease control, and secondary loss of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response fulfillment occurred in 15.9% of patients within approximately 3 years.1 Without other US Food and Drug Administration–approved HS treatments, some dermatologists have combined adalimumab with methotrexate (MTX) and/or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to attempt to increase the duration of satisfactory disease control while on adalimumab. Combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants is a well-established approach in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease; however, to the best of our knowledge, this approach has not been studied for HS.2,3

To assess whether there is a role for combining adalimumab with MTX and/or MMF in the treatment of HS, we performed a single-institution retrospective chart review at the University of Connecticut Department of Dermatology to determine whether patients receiving combination therapy stayed on adalimumab longer than those who received adalimumab monotherapy. All patients receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS with at least 1 follow-up visit 3 or more months after treatment initiation were included. Duration of treatment with adalimumab was defined as the length of time between initiation and termination of adalimumab, regardless of flares, adverse events, or addition of adjuvant therapy that occurred during this time span. Because standardized rating scales measuring the severity of HS at this time are not recorded routinely at our institution, treatment duration with adalimumab was used as a surrogate for measuring therapeutic success. Additionally, treatment duration is a meaningful end point, as patients with HS may require indefinite treatment. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS. Patients were excluded if they were lost to follow-up or had received adalimumab for less than 6 months, as data suggest that biologics do not reach peak effect for up to 6 months in HS.4

We identified 116 eligible patients with HS, 32 of whom received combination therapy. Five patients received 40 mg of adalimumab every other week, and 111 patients received 40 mg of adalimumab each week. Patients receiving oral immunosuppressants were more likely to be male and as likely to be biologic naïve compared to patients on monotherapy (Table). The average weekly dose of MTX was 14.63 mg, and the average daily dose of MMF was 1000 mg. The average number of days between starting adalimumab and starting an oral immunosuppressant was 114.5 (SD, 217; median, 0) days. Reasons for discontinuation of adalimumab included insufficient response, noncompliance, dislike of injections, adverse events, fear of adverse events, other medical issues unrelated to HS, and insurance coverage issues. Patients who ended treatment with adalimumab owing to insurance coverage issues were still included in our study because insurance coverage remains a major determinant of treatment choice in HS and is relevant to the dynamics of medical decision-making.

Statistical analysis was conducted on all patients inclusive of any reason for discontinuation to avoid bias in the calculation of treatment duration. Cox regression analysis was conducted for all independent variables and was noncontributory. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to assess the duration of treatment of adalimumab with and without concomitant oral immunosuppressants, and quartile survival times were calculated. Quartile survival time is the time point after adalimumab initiation at which 25% of patients have discontinued adalimumab. We chose quartile survival time instead of average treatment duration to adequately power this study, given our small patient pool.

Although patients receiving adalimumab with oral immunosuppressants had a longer quartile treatment duration (450 days; 95% CI, 185-1800) than the group without oral immunosuppressants (360 days; 95% CI, 200-700), neither MTX nor MMF was shown to significantly prolong duration of therapy with adalimumab (log-rank test: P=.12). Additionally, patients receiving combination therapy were just as likely to discontinue adalimumab as those on monotherapy (χ2 test: P=.93). Patients who took both MTX and MMF at different times did show a statistically significant increase in adalimumab quartile treatment duration (1710 days; 95% CI, 1620 [upper limit not calculable]), but this is likely because these patients were kept on adalimumab while trialing adjunctive medications.

The results of our study indicate that MTX and MMF do not prolong duration of adalimumab therapy, which suggests that adalimumab combination therapy with MTX and MMF may not improve HS more than adalimumab alone, and/or partial responders to adalimumab monotherapy are unlikely to be converted to satisfactory responders with the addition of oral immunosuppressants. Limitations of our study include that it was retrospective, used treatment duration as a surrogate for objective efficacy measures, and relied on a single-institution data source. Additionally, owing to our small sample size, we were unable to account for certain potential confounders, including patient weight and insurance status. Future controlled prospective studies using objective end points are needed to further elucidate whether oral immunosuppressants have a role as an adjunct in the treatment of HS.

To the Editor:

The tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Although 50.6% of patients fulfilled Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response criteria with adalimumab at 12 weeks, many responders were not satisfied with their disease control, and secondary loss of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response fulfillment occurred in 15.9% of patients within approximately 3 years.1 Without other US Food and Drug Administration–approved HS treatments, some dermatologists have combined adalimumab with methotrexate (MTX) and/or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to attempt to increase the duration of satisfactory disease control while on adalimumab. Combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants is a well-established approach in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease; however, to the best of our knowledge, this approach has not been studied for HS.2,3

To assess whether there is a role for combining adalimumab with MTX and/or MMF in the treatment of HS, we performed a single-institution retrospective chart review at the University of Connecticut Department of Dermatology to determine whether patients receiving combination therapy stayed on adalimumab longer than those who received adalimumab monotherapy. All patients receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS with at least 1 follow-up visit 3 or more months after treatment initiation were included. Duration of treatment with adalimumab was defined as the length of time between initiation and termination of adalimumab, regardless of flares, adverse events, or addition of adjuvant therapy that occurred during this time span. Because standardized rating scales measuring the severity of HS at this time are not recorded routinely at our institution, treatment duration with adalimumab was used as a surrogate for measuring therapeutic success. Additionally, treatment duration is a meaningful end point, as patients with HS may require indefinite treatment. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS. Patients were excluded if they were lost to follow-up or had received adalimumab for less than 6 months, as data suggest that biologics do not reach peak effect for up to 6 months in HS.4

We identified 116 eligible patients with HS, 32 of whom received combination therapy. Five patients received 40 mg of adalimumab every other week, and 111 patients received 40 mg of adalimumab each week. Patients receiving oral immunosuppressants were more likely to be male and as likely to be biologic naïve compared to patients on monotherapy (Table). The average weekly dose of MTX was 14.63 mg, and the average daily dose of MMF was 1000 mg. The average number of days between starting adalimumab and starting an oral immunosuppressant was 114.5 (SD, 217; median, 0) days. Reasons for discontinuation of adalimumab included insufficient response, noncompliance, dislike of injections, adverse events, fear of adverse events, other medical issues unrelated to HS, and insurance coverage issues. Patients who ended treatment with adalimumab owing to insurance coverage issues were still included in our study because insurance coverage remains a major determinant of treatment choice in HS and is relevant to the dynamics of medical decision-making.

Statistical analysis was conducted on all patients inclusive of any reason for discontinuation to avoid bias in the calculation of treatment duration. Cox regression analysis was conducted for all independent variables and was noncontributory. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to assess the duration of treatment of adalimumab with and without concomitant oral immunosuppressants, and quartile survival times were calculated. Quartile survival time is the time point after adalimumab initiation at which 25% of patients have discontinued adalimumab. We chose quartile survival time instead of average treatment duration to adequately power this study, given our small patient pool.

Although patients receiving adalimumab with oral immunosuppressants had a longer quartile treatment duration (450 days; 95% CI, 185-1800) than the group without oral immunosuppressants (360 days; 95% CI, 200-700), neither MTX nor MMF was shown to significantly prolong duration of therapy with adalimumab (log-rank test: P=.12). Additionally, patients receiving combination therapy were just as likely to discontinue adalimumab as those on monotherapy (χ2 test: P=.93). Patients who took both MTX and MMF at different times did show a statistically significant increase in adalimumab quartile treatment duration (1710 days; 95% CI, 1620 [upper limit not calculable]), but this is likely because these patients were kept on adalimumab while trialing adjunctive medications.

The results of our study indicate that MTX and MMF do not prolong duration of adalimumab therapy, which suggests that adalimumab combination therapy with MTX and MMF may not improve HS more than adalimumab alone, and/or partial responders to adalimumab monotherapy are unlikely to be converted to satisfactory responders with the addition of oral immunosuppressants. Limitations of our study include that it was retrospective, used treatment duration as a surrogate for objective efficacy measures, and relied on a single-institution data source. Additionally, owing to our small sample size, we were unable to account for certain potential confounders, including patient weight and insurance status. Future controlled prospective studies using objective end points are needed to further elucidate whether oral immunosuppressants have a role as an adjunct in the treatment of HS.

- Zouboulis CC, Okun MM, Prens EP, et al. Long-term adalimumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: 3-year results of a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:60-69.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.040

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Sultan KS, Berkowitz JC, Khan S. Combination therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8:103-113. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i2.103

- Prussick L, Rothstein B, Joshipura D, et al. Open-label, investigator-initiated, single-site exploratory trial evaluating secukinumab, an anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, for patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:609-611.

- Zouboulis CC, Okun MM, Prens EP, et al. Long-term adalimumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: 3-year results of a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:60-69.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.040

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Sultan KS, Berkowitz JC, Khan S. Combination therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8:103-113. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i2.103

- Prussick L, Rothstein B, Joshipura D, et al. Open-label, investigator-initiated, single-site exploratory trial evaluating secukinumab, an anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, for patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:609-611.

Practice Points

- Adalimumab is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), yet many patients on adalimumab do not achieve satisfactory results. New treatment options are in demand for patients affected by HS.

- Although combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants such as methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil appears to be beneficial in treating other conditions such as psoriasis, these treatments may not have as great a benefit for patients with HS.

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy to Facilitate Knifeless Skin Cancer Management

Practice Gap

Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in elderly patients can cause morbidity because these patients frequently struggle to care for their biopsy sites and experience biopsy- and surgery-related complications. To minimize this treatment-related morbidity, we designed a knifeless treatment approach that employs reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) in lieu of skin biopsy to establish the diagnosis of NMSC, then uses either intralesional or topical chemotherapy or immunotherapy (as appropriate, depending on depth of invasion) to cure the NMSC. With this approach, the patient is spared both biopsy- and surgery-related difficulties, though both intralesional and topical chemotherapy are accompanied by their own risks for adverse effects.

The Technique

Elderly patients, diabetic patients, and patients with lesions suspicious for NMSC on areas prone to poor wound healing or to notable treatment-related morbidity (eg, lower legs, genitals, the face of younger patients) are offered skin biopsy or RCM; the latter is performed during the appointment by an RC

When resolution is uncertain, RCM is repeated to assess for tumor clearance. Repeat RCM is performed at least 4 weeks after termination of treatment to avoid misinterpretation caused by treatment-related tissue inflammation. Patients who are not cured using this management approach are offered appropriate surgical management.

Practice Implications

Reflectance confocal microscopy has emerged as an effective modality for confirming the diagnosis of NMSC with high sensitivity and specificity.1,2 Emergence of this technology presents an opportunity for improving the way the NMSC is managed because RCM allows dermatologists to confirm the diagnosis of BCC and SCC by interpretation of RCM mosaics rather than by histopathologic examination of biopsied tissue. Our knifeless approach to skin cancer management is especially beneficial when biopsy and dermatologic surgery are likely to confer notable morbidity, such as managing NMSC on the face of a young adult, in the frail elderly population, or in diabetic patients, and when treating sites on the lower extremity prone to poor wound healing.

- Song E, Grant-Kels JM, Swede H, et al. Paired comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis and reflectance confocal microscopy in the detection of melanoma in vivo: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1187-1192.

- Ferrari B, Salgarelli AC, Mandel VD, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: the aid of reflectance confocal microscopy for the accurate diagnosis and management. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152:169-177.

Practice Gap

Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in elderly patients can cause morbidity because these patients frequently struggle to care for their biopsy sites and experience biopsy- and surgery-related complications. To minimize this treatment-related morbidity, we designed a knifeless treatment approach that employs reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) in lieu of skin biopsy to establish the diagnosis of NMSC, then uses either intralesional or topical chemotherapy or immunotherapy (as appropriate, depending on depth of invasion) to cure the NMSC. With this approach, the patient is spared both biopsy- and surgery-related difficulties, though both intralesional and topical chemotherapy are accompanied by their own risks for adverse effects.

The Technique

Elderly patients, diabetic patients, and patients with lesions suspicious for NMSC on areas prone to poor wound healing or to notable treatment-related morbidity (eg, lower legs, genitals, the face of younger patients) are offered skin biopsy or RCM; the latter is performed during the appointment by an RC

When resolution is uncertain, RCM is repeated to assess for tumor clearance. Repeat RCM is performed at least 4 weeks after termination of treatment to avoid misinterpretation caused by treatment-related tissue inflammation. Patients who are not cured using this management approach are offered appropriate surgical management.

Practice Implications

Reflectance confocal microscopy has emerged as an effective modality for confirming the diagnosis of NMSC with high sensitivity and specificity.1,2 Emergence of this technology presents an opportunity for improving the way the NMSC is managed because RCM allows dermatologists to confirm the diagnosis of BCC and SCC by interpretation of RCM mosaics rather than by histopathologic examination of biopsied tissue. Our knifeless approach to skin cancer management is especially beneficial when biopsy and dermatologic surgery are likely to confer notable morbidity, such as managing NMSC on the face of a young adult, in the frail elderly population, or in diabetic patients, and when treating sites on the lower extremity prone to poor wound healing.

Practice Gap

Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in elderly patients can cause morbidity because these patients frequently struggle to care for their biopsy sites and experience biopsy- and surgery-related complications. To minimize this treatment-related morbidity, we designed a knifeless treatment approach that employs reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) in lieu of skin biopsy to establish the diagnosis of NMSC, then uses either intralesional or topical chemotherapy or immunotherapy (as appropriate, depending on depth of invasion) to cure the NMSC. With this approach, the patient is spared both biopsy- and surgery-related difficulties, though both intralesional and topical chemotherapy are accompanied by their own risks for adverse effects.

The Technique

Elderly patients, diabetic patients, and patients with lesions suspicious for NMSC on areas prone to poor wound healing or to notable treatment-related morbidity (eg, lower legs, genitals, the face of younger patients) are offered skin biopsy or RCM; the latter is performed during the appointment by an RC

When resolution is uncertain, RCM is repeated to assess for tumor clearance. Repeat RCM is performed at least 4 weeks after termination of treatment to avoid misinterpretation caused by treatment-related tissue inflammation. Patients who are not cured using this management approach are offered appropriate surgical management.

Practice Implications

Reflectance confocal microscopy has emerged as an effective modality for confirming the diagnosis of NMSC with high sensitivity and specificity.1,2 Emergence of this technology presents an opportunity for improving the way the NMSC is managed because RCM allows dermatologists to confirm the diagnosis of BCC and SCC by interpretation of RCM mosaics rather than by histopathologic examination of biopsied tissue. Our knifeless approach to skin cancer management is especially beneficial when biopsy and dermatologic surgery are likely to confer notable morbidity, such as managing NMSC on the face of a young adult, in the frail elderly population, or in diabetic patients, and when treating sites on the lower extremity prone to poor wound healing.

- Song E, Grant-Kels JM, Swede H, et al. Paired comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis and reflectance confocal microscopy in the detection of melanoma in vivo: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1187-1192.

- Ferrari B, Salgarelli AC, Mandel VD, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: the aid of reflectance confocal microscopy for the accurate diagnosis and management. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152:169-177.

- Song E, Grant-Kels JM, Swede H, et al. Paired comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis and reflectance confocal microscopy in the detection of melanoma in vivo: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1187-1192.

- Ferrari B, Salgarelli AC, Mandel VD, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: the aid of reflectance confocal microscopy for the accurate diagnosis and management. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152:169-177.

Linear Bluish Black Papules on the Shoulder

The Diagnosis: Agminated Blue Nevus

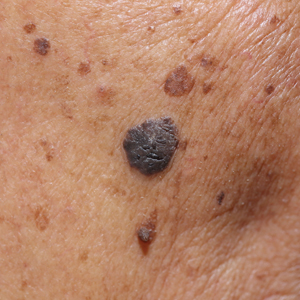

Agminated blue nevus is a rare melanocytic nevus that characteristically presents as a group of multiple small, bluish papules occurring in a well-circumscribed area.1 It also has been referred to as a plaque-type nevus2,3 and an eruptive blue nevus.4 Originally described by Upshaw et al2 in 1947, agminated blue nevi may be congenital or arise in early childhood and almost always occur on the trunk. The skin between the papules often is unaffected or sometimes may show bluish or brown pigmentation.4 Agminated blue nevi usually are smaller than 10 cm in diameter; however, rare cases have measured up to 24 cm.1,4-6 The incidence of agminated blue nevi is 2 times higher in males than in females.1

|

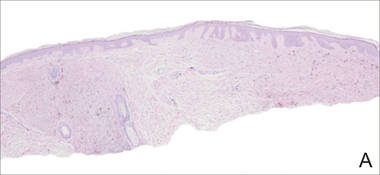

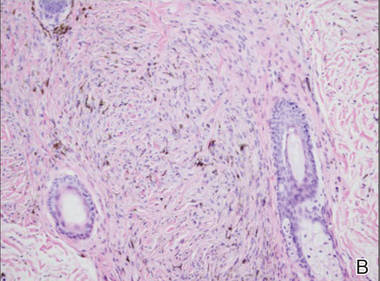

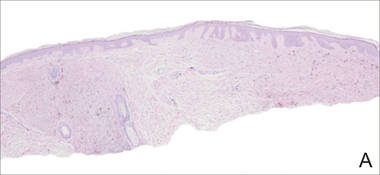

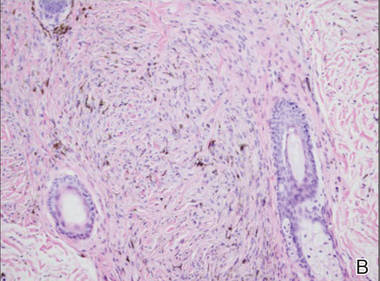

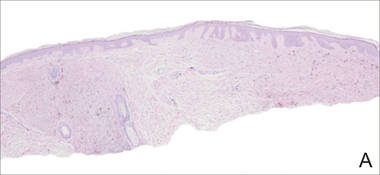

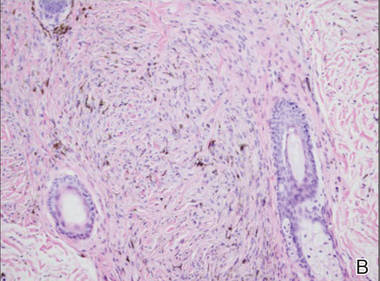

A biopsy of the lesion revealed pigmented dendritic melanocytes admixed with melanophages, forming fascicles and bundles (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). In some areas the dermis was uninvolved. Higher magnification showed dendritic and epithelioid melanocytes extending down along the adnexal structures (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Histopathologically, agminated blue nevi typically demonstrate the features of common and/or cellular blue nevi. Cytologic atypia and mitoses are rare.1 The degree of cellularity and pigmentation of the lesions is variable, and the presence of subcutaneous cellular nodules also has been described.5

In our patient, histologic evaluation revealed foci of diffuse dermal spindle cell proliferation composed of heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes admixed with melanophages in a fibrotic stroma (Figure, A). The dermis was uninvolved in some areas and the melanocytes were epithelioid and formed fascicles and bundles that extended down adnexal structures in other areas (Figure, B). Junctional involvement of melanocytes, cellular atypia, and mitoses were not identified. Our case demonstrated a combination of histologic findings of a cellular blue nevus as well as features reminiscent of a deep penetrating nevus. The differential diagnosis of agminated blue nevus includes agminated Spitz nevus arising in a speckled lentiginous nevus,7 dermal melanocytosis, melanoma, and pilar neurocristic hamartoma. Pilar neurocristic hamartomas may resemble plaque-type blue nevi; however, the former show a predilection for the scalp, histologically demonstrate features that overlap with blue nevi and congenital nevi, and are associated with neural structures that show Schwannian differentiation.8 Agminated blue nevi usually are characterized by a benign clinical course, but few cases describing malignant changes with development of malignant melanoma have been reported.9,10 Therefore, recognition of the clinical and histopathologic spectrum of agminated blue nevus is critical in order to avoid diagnostic pitfalls and confusion with melanoma.

- Vélez A, del-Río E, Martín-de-Hijas C, et al. Agminated blue nevi: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 1993;186:144-148.

- Upshaw BY, Ghormley RK, Montgomery H. Extensive blue nevus of Jadassohn-Tièche; report of a case. Surgery. 1947;22:761-765.

- Pittman JL, Fisher BK. Plaque-type blue nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1127-1128.

- Hendricks WM. Eruptive blue nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol.1981;4:50-53.

- Busam KJ, Woodruff JM, Erlandson RA, et al. Large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:92-99.

- Shenfield HT, Maize JC. Multiple and agminated blue nevi. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1980;6:725-728.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y, Kohda H. A combination of speckled lentiginous nevus with patch-type blue nevus. J Dermatol. 1993;20:643-647.

- Bevona C, Tannous Z, Tsao H. Dermal melanocytic proliferation with features of a plaque-type blue nevus and neurocristic hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:924-929.

- Yeh I, Fang Y, Busam KJ. Melanoma arising in a large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1258-1263.

- Zattra E, Salmaso R, Montesco MC, et al. Large plaque type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:287-288.

The Diagnosis: Agminated Blue Nevus

Agminated blue nevus is a rare melanocytic nevus that characteristically presents as a group of multiple small, bluish papules occurring in a well-circumscribed area.1 It also has been referred to as a plaque-type nevus2,3 and an eruptive blue nevus.4 Originally described by Upshaw et al2 in 1947, agminated blue nevi may be congenital or arise in early childhood and almost always occur on the trunk. The skin between the papules often is unaffected or sometimes may show bluish or brown pigmentation.4 Agminated blue nevi usually are smaller than 10 cm in diameter; however, rare cases have measured up to 24 cm.1,4-6 The incidence of agminated blue nevi is 2 times higher in males than in females.1

|

A biopsy of the lesion revealed pigmented dendritic melanocytes admixed with melanophages, forming fascicles and bundles (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). In some areas the dermis was uninvolved. Higher magnification showed dendritic and epithelioid melanocytes extending down along the adnexal structures (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Histopathologically, agminated blue nevi typically demonstrate the features of common and/or cellular blue nevi. Cytologic atypia and mitoses are rare.1 The degree of cellularity and pigmentation of the lesions is variable, and the presence of subcutaneous cellular nodules also has been described.5

In our patient, histologic evaluation revealed foci of diffuse dermal spindle cell proliferation composed of heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes admixed with melanophages in a fibrotic stroma (Figure, A). The dermis was uninvolved in some areas and the melanocytes were epithelioid and formed fascicles and bundles that extended down adnexal structures in other areas (Figure, B). Junctional involvement of melanocytes, cellular atypia, and mitoses were not identified. Our case demonstrated a combination of histologic findings of a cellular blue nevus as well as features reminiscent of a deep penetrating nevus. The differential diagnosis of agminated blue nevus includes agminated Spitz nevus arising in a speckled lentiginous nevus,7 dermal melanocytosis, melanoma, and pilar neurocristic hamartoma. Pilar neurocristic hamartomas may resemble plaque-type blue nevi; however, the former show a predilection for the scalp, histologically demonstrate features that overlap with blue nevi and congenital nevi, and are associated with neural structures that show Schwannian differentiation.8 Agminated blue nevi usually are characterized by a benign clinical course, but few cases describing malignant changes with development of malignant melanoma have been reported.9,10 Therefore, recognition of the clinical and histopathologic spectrum of agminated blue nevus is critical in order to avoid diagnostic pitfalls and confusion with melanoma.

The Diagnosis: Agminated Blue Nevus

Agminated blue nevus is a rare melanocytic nevus that characteristically presents as a group of multiple small, bluish papules occurring in a well-circumscribed area.1 It also has been referred to as a plaque-type nevus2,3 and an eruptive blue nevus.4 Originally described by Upshaw et al2 in 1947, agminated blue nevi may be congenital or arise in early childhood and almost always occur on the trunk. The skin between the papules often is unaffected or sometimes may show bluish or brown pigmentation.4 Agminated blue nevi usually are smaller than 10 cm in diameter; however, rare cases have measured up to 24 cm.1,4-6 The incidence of agminated blue nevi is 2 times higher in males than in females.1

|

A biopsy of the lesion revealed pigmented dendritic melanocytes admixed with melanophages, forming fascicles and bundles (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). In some areas the dermis was uninvolved. Higher magnification showed dendritic and epithelioid melanocytes extending down along the adnexal structures (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Histopathologically, agminated blue nevi typically demonstrate the features of common and/or cellular blue nevi. Cytologic atypia and mitoses are rare.1 The degree of cellularity and pigmentation of the lesions is variable, and the presence of subcutaneous cellular nodules also has been described.5

In our patient, histologic evaluation revealed foci of diffuse dermal spindle cell proliferation composed of heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes admixed with melanophages in a fibrotic stroma (Figure, A). The dermis was uninvolved in some areas and the melanocytes were epithelioid and formed fascicles and bundles that extended down adnexal structures in other areas (Figure, B). Junctional involvement of melanocytes, cellular atypia, and mitoses were not identified. Our case demonstrated a combination of histologic findings of a cellular blue nevus as well as features reminiscent of a deep penetrating nevus. The differential diagnosis of agminated blue nevus includes agminated Spitz nevus arising in a speckled lentiginous nevus,7 dermal melanocytosis, melanoma, and pilar neurocristic hamartoma. Pilar neurocristic hamartomas may resemble plaque-type blue nevi; however, the former show a predilection for the scalp, histologically demonstrate features that overlap with blue nevi and congenital nevi, and are associated with neural structures that show Schwannian differentiation.8 Agminated blue nevi usually are characterized by a benign clinical course, but few cases describing malignant changes with development of malignant melanoma have been reported.9,10 Therefore, recognition of the clinical and histopathologic spectrum of agminated blue nevus is critical in order to avoid diagnostic pitfalls and confusion with melanoma.

- Vélez A, del-Río E, Martín-de-Hijas C, et al. Agminated blue nevi: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 1993;186:144-148.

- Upshaw BY, Ghormley RK, Montgomery H. Extensive blue nevus of Jadassohn-Tièche; report of a case. Surgery. 1947;22:761-765.

- Pittman JL, Fisher BK. Plaque-type blue nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1127-1128.

- Hendricks WM. Eruptive blue nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol.1981;4:50-53.

- Busam KJ, Woodruff JM, Erlandson RA, et al. Large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:92-99.

- Shenfield HT, Maize JC. Multiple and agminated blue nevi. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1980;6:725-728.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y, Kohda H. A combination of speckled lentiginous nevus with patch-type blue nevus. J Dermatol. 1993;20:643-647.

- Bevona C, Tannous Z, Tsao H. Dermal melanocytic proliferation with features of a plaque-type blue nevus and neurocristic hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:924-929.

- Yeh I, Fang Y, Busam KJ. Melanoma arising in a large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1258-1263.

- Zattra E, Salmaso R, Montesco MC, et al. Large plaque type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:287-288.

- Vélez A, del-Río E, Martín-de-Hijas C, et al. Agminated blue nevi: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 1993;186:144-148.

- Upshaw BY, Ghormley RK, Montgomery H. Extensive blue nevus of Jadassohn-Tièche; report of a case. Surgery. 1947;22:761-765.

- Pittman JL, Fisher BK. Plaque-type blue nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1127-1128.

- Hendricks WM. Eruptive blue nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol.1981;4:50-53.

- Busam KJ, Woodruff JM, Erlandson RA, et al. Large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:92-99.

- Shenfield HT, Maize JC. Multiple and agminated blue nevi. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1980;6:725-728.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y, Kohda H. A combination of speckled lentiginous nevus with patch-type blue nevus. J Dermatol. 1993;20:643-647.

- Bevona C, Tannous Z, Tsao H. Dermal melanocytic proliferation with features of a plaque-type blue nevus and neurocristic hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:924-929.

- Yeh I, Fang Y, Busam KJ. Melanoma arising in a large plaque-type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1258-1263.

- Zattra E, Salmaso R, Montesco MC, et al. Large plaque type blue nevus with subcutaneous cellular nodules. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:287-288.

A 57-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic, unchanging, 3.5×0.7-cm linear plaque on the right shoulder composed of dozens of clustered, bluish black papules that had been present for several decades. The skin between the papules was unaffected. The patient’s medical and family histories were unremarkable. A deep shave biopsy from the center of the plaque was performed.