User login

Healthcare Encounter and Financial Impact of COVID-19 on Children’s Hospitals

To benefit patients and the public health of their communities, children’s hospitals across the United States prepared for and responded to COVID-19 by conserving personal protective equipment, suspending noncritical in-person healthcare encounters (including outpatient visits and elective surgeries), and implementing socially distanced essential care.1,2 These measures were promptly instituted during a time of both substantial uncertainty about the pandemic’s behavior in children—including its severity and duration—and extreme variation in local and state governments’ responses to the pandemic.

Congruent with other healthcare institutions, children’s hospitals calibrated their clinical operations to the evolving nature of the pandemic, prioritizing the safety of patients and staff while striving to maintain financial viability in the setting of increased costs and decreased revenue. In some cases, children’s hospitals aided adult hospitals and health systems by admitting young and middle-aged adult patients and by centralizing all pediatric patients requiring intensive care within a region. These efforts occurred while many children’s hospitals remained the sole source of specialized pediatric care, including care for rare complex health problems.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there is a critical need to assess how the initial phase of the pandemic affected healthcare encounters and related finances in children’s hospitals. Understanding these trends will position children’s hospitals to project and prepare for subsequent COVID-19 surges, as well as future related public health crises that necessitate widespread social distancing. Therefore, we compared year-over-year trends in healthcare encounters and hospital charges across US children’s hospitals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the beginning of COVID-19 in the United States, which was defined as February through June 2020.

METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of 26 children’s hospitals (22 freestanding, 4 nonfreestanding) from all US regions (12 South, 7 Midwest, 5 West, 2 Northeast) contributing encounter and financial data to the PROSPECT database (Children’s Hospital Association, Lenexa, Kansas) from February 1 to June 30 in both 2019 (before COVID-19) and 2020 (during COVID-19). In response to COVID-19, hospitals participating in PROSPECT increased the efficiency of data centralization and reporting in 2020 during the period February 1 to June 30 to expedite analysis and dissemination of findings.

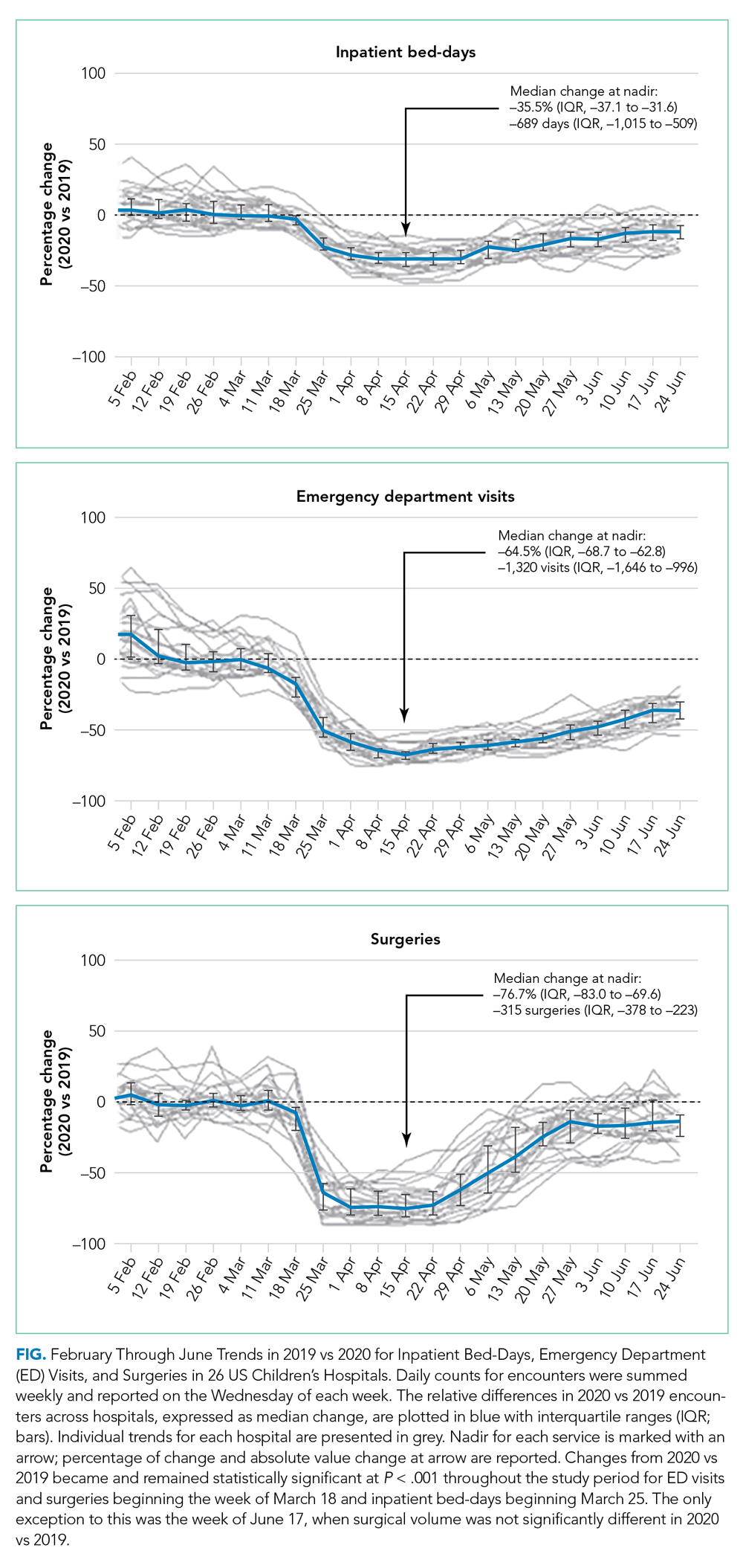

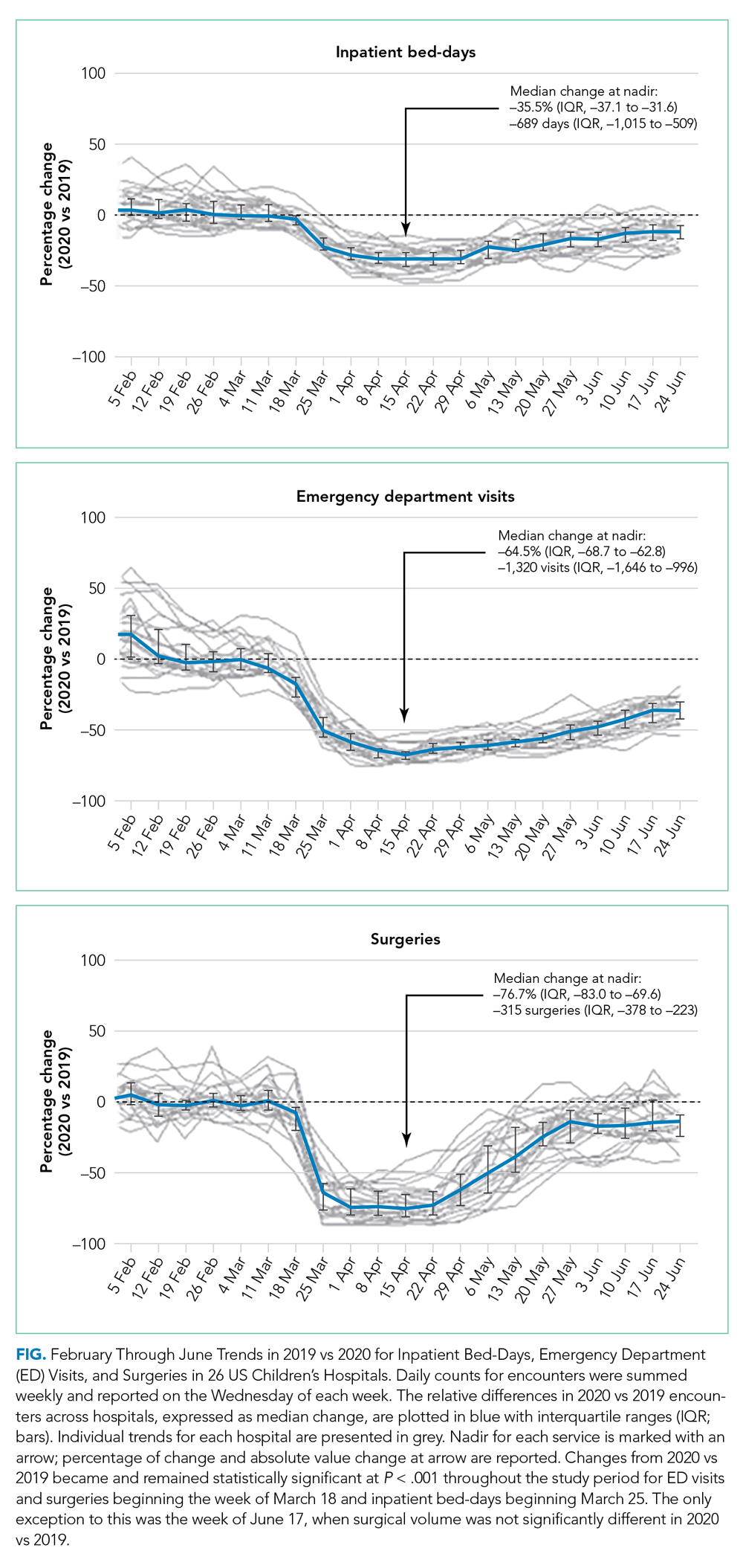

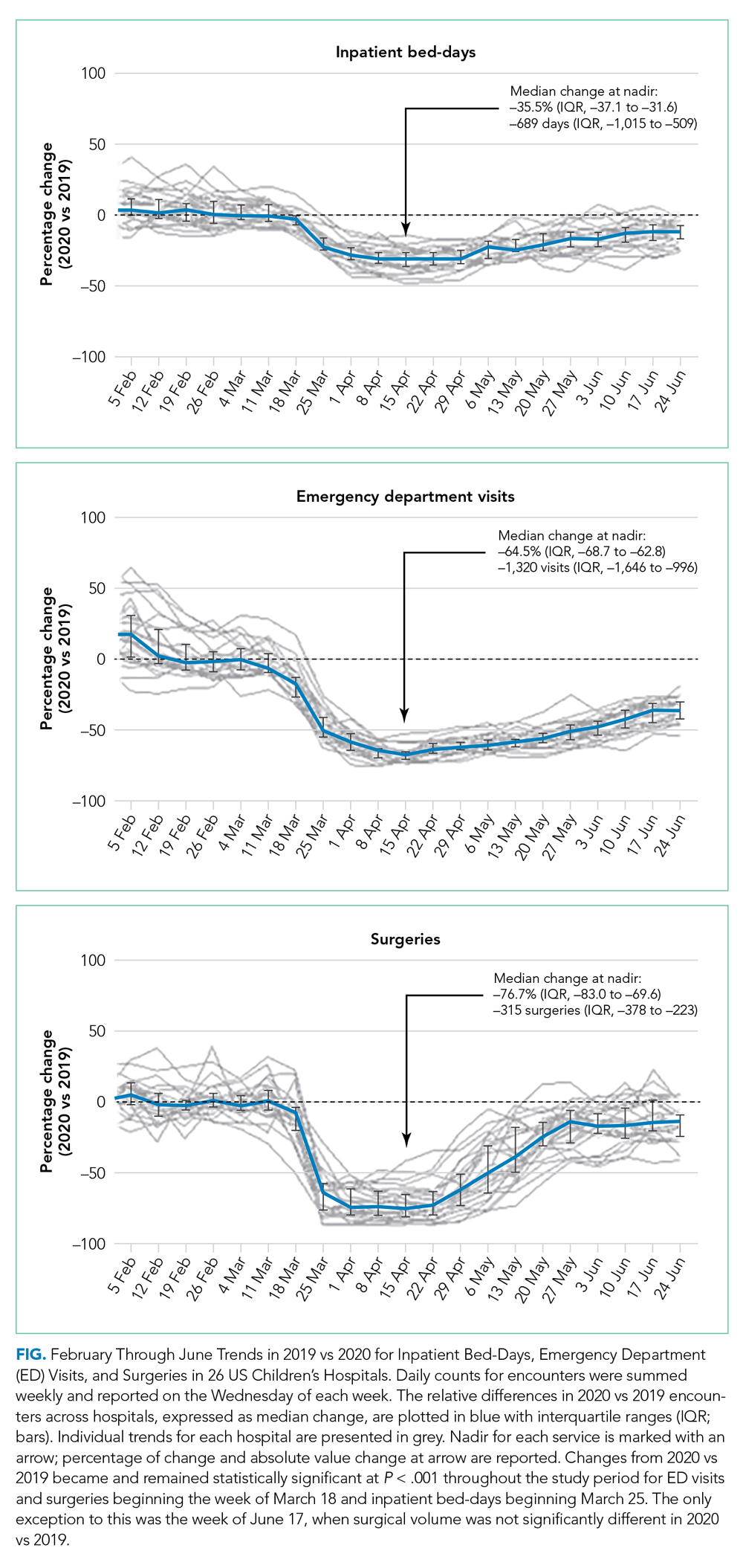

The main outcome measures were the percentage of change in weekly encounters (inpatient bed-days, emergency department [ED] visits, and surgeries) and inflation-adjusted charges (categorized as inpatient care and outpatient care, such as ambulatory surgery, clinics, and ED visits) before vs during COVID-19.

RESULTS

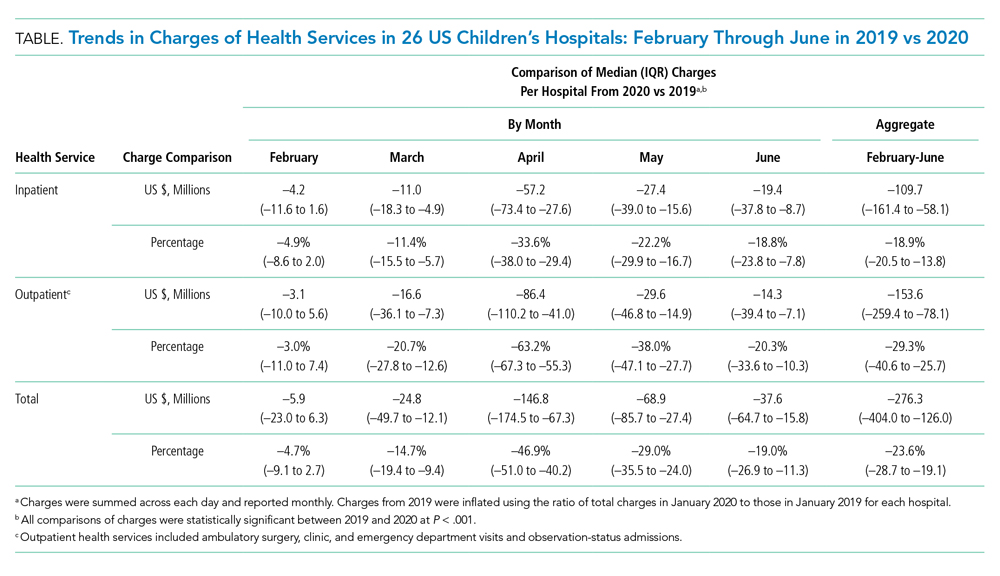

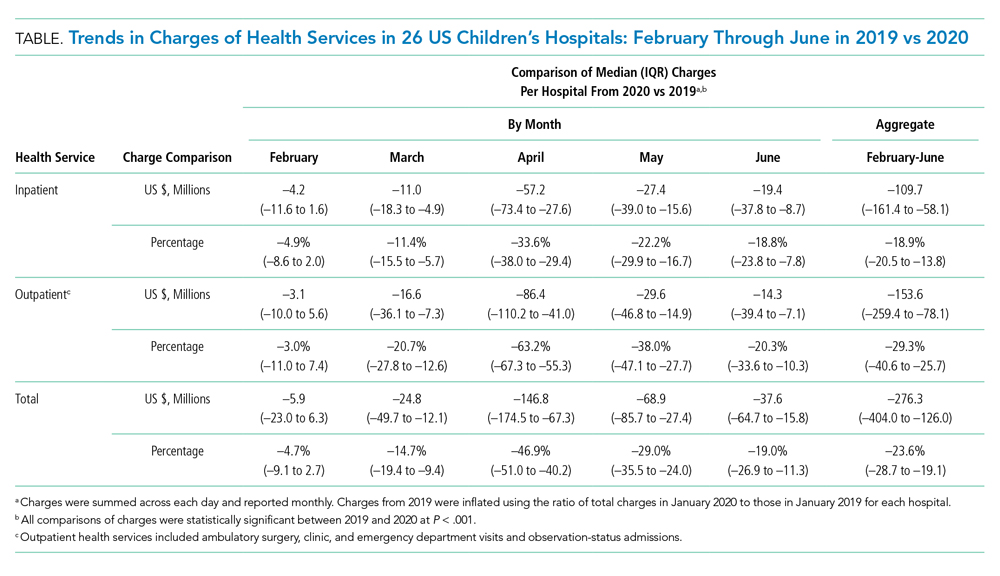

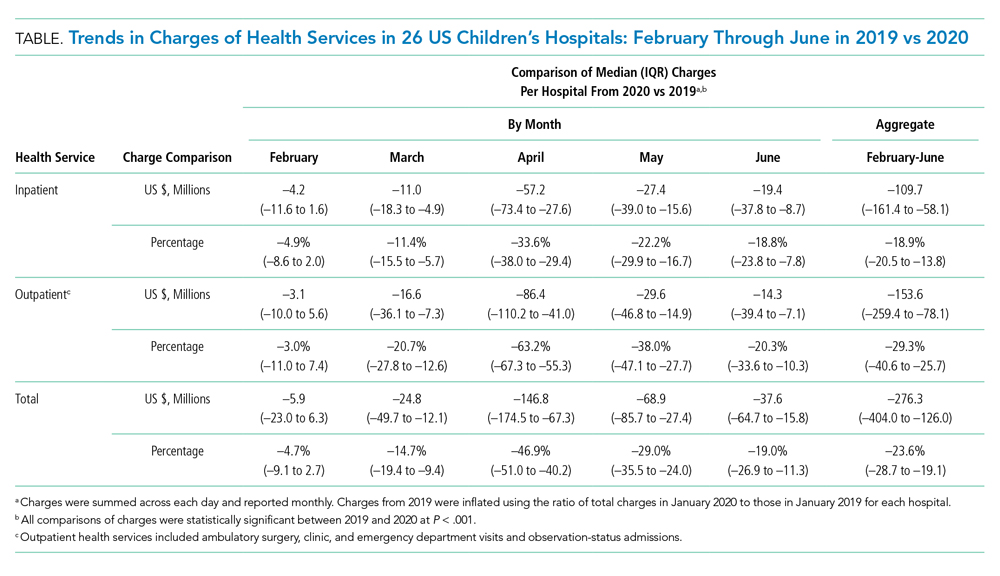

Charges that accrued from February 1 to June 30 were lower in 2020 by a median 23.6% (IQR, –28.7% to –19.1%) per children’s hospital than they were in 2019, corresponding to a median decrease of $276.3 million (IQR, $404.0-$126.0 million) in charges per hospital (Table). Forty percent of this decrease was attributable to decreased charges resulting from fewer inpatient healthcare encounters.

DISCUSSION

These findings beg the question of how well children’s hospitals are positioned to weather a recurrent surge in COVID-19. Because the severity of illness of COVID-19 has been lower to date in the pediatric vs adult populations, an increase in COVID-19-related visits to EDs and admissions to offset the decreased resource use of other pediatric healthcare problems is not anticipated. Existing hospital financial reserves as well as federal aid from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act that helped mitigate the initial encounter and financial losses during the beginning of COVID-19 may not be readily available over time.4,5 Certainly, the findings from the current study support continued lobbying for additional state and federal funds allocated through future relief packages to children’s hospitals.

Additional approaches to financial solvency in children’s hospitals during the sustained COVID-19 pandemic include addressing surgical backlogs and sharing best practices for safe and sustained reopening of clinical operations and financial practices across institutions. Although the PROSPECT database does not contain information on the types of surgeries present within this backlog, our experiences suggest that both same-day and inpatient elective surgeries have been affected, especially lengthy procedures (eg, spinal fusion for neuromuscular scoliosis). Spread and scale of feasible and efficient solutions to reengineer and expand patient capacities and throughput for operating rooms, postanesthesia recovery areas, and intensive care and floor units are needed. Enhanced analytics that accurately predict postoperative length of hospital stay, coupled with early recovery after surgery clinical protocols, could help optimize hospital bed management. Effective ways to convert hospital rooms from single to double occupancy, to manage family visitation, and to proactively test asymptomatic patients, family, and hospital staff will mitigate continued COVID-19 penetration through children’s hospitals.

One important limitation of the current study is the measurement of hospitals’ charges. The charge data were not positioned to comprehensively measure each hospital’s financial state during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the decrease in hospital charges reported by the children’s hospitals in the current study is comparable with the financial losses reported for many adult hospitals during the pandemic.6,7

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals’ ability to serve the nation’s pediatric patients depends on the success of the hospitals’ plans to manage current and future COVID-19 surges and to reopen and recover from the surges that have passed. Additional investigation is needed to identify best operational and financial practices among children’s hospitals that have enabled them to endure the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. COVID-19: ways to prepare your children’s hospital now. Children’s Hospital Association. March 12, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Newsroom/Childrens-Hospitals-Today/Articles/2020/03/COVID-19-11-Ways-to-Prepare-Your-Hospital-Now

2. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

3. Oseran AS, Nash D, Kim C, et al. Changes in hospital admissions for urgent conditions during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(8):327-328. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.43837

4. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the CARES Act. 15 USC Chapter 116 (2020). Pub L No. 116-36, 134 Stat 281. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748

5. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Provider Relief Fund: general information. US Department of Health & Human Services. June 25, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/cares-act-provider-relief-fund/general-information/index.html

6. Hospitals and health systems face unprecedented financial pressures due to COVID-19. American Hospital Association. May 2020. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/aha-covid19-financial-impact-0520-FINAL.pdf

7. Birkmeyer J, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

To benefit patients and the public health of their communities, children’s hospitals across the United States prepared for and responded to COVID-19 by conserving personal protective equipment, suspending noncritical in-person healthcare encounters (including outpatient visits and elective surgeries), and implementing socially distanced essential care.1,2 These measures were promptly instituted during a time of both substantial uncertainty about the pandemic’s behavior in children—including its severity and duration—and extreme variation in local and state governments’ responses to the pandemic.

Congruent with other healthcare institutions, children’s hospitals calibrated their clinical operations to the evolving nature of the pandemic, prioritizing the safety of patients and staff while striving to maintain financial viability in the setting of increased costs and decreased revenue. In some cases, children’s hospitals aided adult hospitals and health systems by admitting young and middle-aged adult patients and by centralizing all pediatric patients requiring intensive care within a region. These efforts occurred while many children’s hospitals remained the sole source of specialized pediatric care, including care for rare complex health problems.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there is a critical need to assess how the initial phase of the pandemic affected healthcare encounters and related finances in children’s hospitals. Understanding these trends will position children’s hospitals to project and prepare for subsequent COVID-19 surges, as well as future related public health crises that necessitate widespread social distancing. Therefore, we compared year-over-year trends in healthcare encounters and hospital charges across US children’s hospitals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the beginning of COVID-19 in the United States, which was defined as February through June 2020.

METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of 26 children’s hospitals (22 freestanding, 4 nonfreestanding) from all US regions (12 South, 7 Midwest, 5 West, 2 Northeast) contributing encounter and financial data to the PROSPECT database (Children’s Hospital Association, Lenexa, Kansas) from February 1 to June 30 in both 2019 (before COVID-19) and 2020 (during COVID-19). In response to COVID-19, hospitals participating in PROSPECT increased the efficiency of data centralization and reporting in 2020 during the period February 1 to June 30 to expedite analysis and dissemination of findings.

The main outcome measures were the percentage of change in weekly encounters (inpatient bed-days, emergency department [ED] visits, and surgeries) and inflation-adjusted charges (categorized as inpatient care and outpatient care, such as ambulatory surgery, clinics, and ED visits) before vs during COVID-19.

RESULTS

Charges that accrued from February 1 to June 30 were lower in 2020 by a median 23.6% (IQR, –28.7% to –19.1%) per children’s hospital than they were in 2019, corresponding to a median decrease of $276.3 million (IQR, $404.0-$126.0 million) in charges per hospital (Table). Forty percent of this decrease was attributable to decreased charges resulting from fewer inpatient healthcare encounters.

DISCUSSION

These findings beg the question of how well children’s hospitals are positioned to weather a recurrent surge in COVID-19. Because the severity of illness of COVID-19 has been lower to date in the pediatric vs adult populations, an increase in COVID-19-related visits to EDs and admissions to offset the decreased resource use of other pediatric healthcare problems is not anticipated. Existing hospital financial reserves as well as federal aid from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act that helped mitigate the initial encounter and financial losses during the beginning of COVID-19 may not be readily available over time.4,5 Certainly, the findings from the current study support continued lobbying for additional state and federal funds allocated through future relief packages to children’s hospitals.

Additional approaches to financial solvency in children’s hospitals during the sustained COVID-19 pandemic include addressing surgical backlogs and sharing best practices for safe and sustained reopening of clinical operations and financial practices across institutions. Although the PROSPECT database does not contain information on the types of surgeries present within this backlog, our experiences suggest that both same-day and inpatient elective surgeries have been affected, especially lengthy procedures (eg, spinal fusion for neuromuscular scoliosis). Spread and scale of feasible and efficient solutions to reengineer and expand patient capacities and throughput for operating rooms, postanesthesia recovery areas, and intensive care and floor units are needed. Enhanced analytics that accurately predict postoperative length of hospital stay, coupled with early recovery after surgery clinical protocols, could help optimize hospital bed management. Effective ways to convert hospital rooms from single to double occupancy, to manage family visitation, and to proactively test asymptomatic patients, family, and hospital staff will mitigate continued COVID-19 penetration through children’s hospitals.

One important limitation of the current study is the measurement of hospitals’ charges. The charge data were not positioned to comprehensively measure each hospital’s financial state during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the decrease in hospital charges reported by the children’s hospitals in the current study is comparable with the financial losses reported for many adult hospitals during the pandemic.6,7

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals’ ability to serve the nation’s pediatric patients depends on the success of the hospitals’ plans to manage current and future COVID-19 surges and to reopen and recover from the surges that have passed. Additional investigation is needed to identify best operational and financial practices among children’s hospitals that have enabled them to endure the COVID-19 pandemic.

To benefit patients and the public health of their communities, children’s hospitals across the United States prepared for and responded to COVID-19 by conserving personal protective equipment, suspending noncritical in-person healthcare encounters (including outpatient visits and elective surgeries), and implementing socially distanced essential care.1,2 These measures were promptly instituted during a time of both substantial uncertainty about the pandemic’s behavior in children—including its severity and duration—and extreme variation in local and state governments’ responses to the pandemic.

Congruent with other healthcare institutions, children’s hospitals calibrated their clinical operations to the evolving nature of the pandemic, prioritizing the safety of patients and staff while striving to maintain financial viability in the setting of increased costs and decreased revenue. In some cases, children’s hospitals aided adult hospitals and health systems by admitting young and middle-aged adult patients and by centralizing all pediatric patients requiring intensive care within a region. These efforts occurred while many children’s hospitals remained the sole source of specialized pediatric care, including care for rare complex health problems.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there is a critical need to assess how the initial phase of the pandemic affected healthcare encounters and related finances in children’s hospitals. Understanding these trends will position children’s hospitals to project and prepare for subsequent COVID-19 surges, as well as future related public health crises that necessitate widespread social distancing. Therefore, we compared year-over-year trends in healthcare encounters and hospital charges across US children’s hospitals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the beginning of COVID-19 in the United States, which was defined as February through June 2020.

METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of 26 children’s hospitals (22 freestanding, 4 nonfreestanding) from all US regions (12 South, 7 Midwest, 5 West, 2 Northeast) contributing encounter and financial data to the PROSPECT database (Children’s Hospital Association, Lenexa, Kansas) from February 1 to June 30 in both 2019 (before COVID-19) and 2020 (during COVID-19). In response to COVID-19, hospitals participating in PROSPECT increased the efficiency of data centralization and reporting in 2020 during the period February 1 to June 30 to expedite analysis and dissemination of findings.

The main outcome measures were the percentage of change in weekly encounters (inpatient bed-days, emergency department [ED] visits, and surgeries) and inflation-adjusted charges (categorized as inpatient care and outpatient care, such as ambulatory surgery, clinics, and ED visits) before vs during COVID-19.

RESULTS

Charges that accrued from February 1 to June 30 were lower in 2020 by a median 23.6% (IQR, –28.7% to –19.1%) per children’s hospital than they were in 2019, corresponding to a median decrease of $276.3 million (IQR, $404.0-$126.0 million) in charges per hospital (Table). Forty percent of this decrease was attributable to decreased charges resulting from fewer inpatient healthcare encounters.

DISCUSSION

These findings beg the question of how well children’s hospitals are positioned to weather a recurrent surge in COVID-19. Because the severity of illness of COVID-19 has been lower to date in the pediatric vs adult populations, an increase in COVID-19-related visits to EDs and admissions to offset the decreased resource use of other pediatric healthcare problems is not anticipated. Existing hospital financial reserves as well as federal aid from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act that helped mitigate the initial encounter and financial losses during the beginning of COVID-19 may not be readily available over time.4,5 Certainly, the findings from the current study support continued lobbying for additional state and federal funds allocated through future relief packages to children’s hospitals.

Additional approaches to financial solvency in children’s hospitals during the sustained COVID-19 pandemic include addressing surgical backlogs and sharing best practices for safe and sustained reopening of clinical operations and financial practices across institutions. Although the PROSPECT database does not contain information on the types of surgeries present within this backlog, our experiences suggest that both same-day and inpatient elective surgeries have been affected, especially lengthy procedures (eg, spinal fusion for neuromuscular scoliosis). Spread and scale of feasible and efficient solutions to reengineer and expand patient capacities and throughput for operating rooms, postanesthesia recovery areas, and intensive care and floor units are needed. Enhanced analytics that accurately predict postoperative length of hospital stay, coupled with early recovery after surgery clinical protocols, could help optimize hospital bed management. Effective ways to convert hospital rooms from single to double occupancy, to manage family visitation, and to proactively test asymptomatic patients, family, and hospital staff will mitigate continued COVID-19 penetration through children’s hospitals.

One important limitation of the current study is the measurement of hospitals’ charges. The charge data were not positioned to comprehensively measure each hospital’s financial state during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the decrease in hospital charges reported by the children’s hospitals in the current study is comparable with the financial losses reported for many adult hospitals during the pandemic.6,7

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals’ ability to serve the nation’s pediatric patients depends on the success of the hospitals’ plans to manage current and future COVID-19 surges and to reopen and recover from the surges that have passed. Additional investigation is needed to identify best operational and financial practices among children’s hospitals that have enabled them to endure the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. COVID-19: ways to prepare your children’s hospital now. Children’s Hospital Association. March 12, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Newsroom/Childrens-Hospitals-Today/Articles/2020/03/COVID-19-11-Ways-to-Prepare-Your-Hospital-Now

2. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

3. Oseran AS, Nash D, Kim C, et al. Changes in hospital admissions for urgent conditions during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(8):327-328. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.43837

4. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the CARES Act. 15 USC Chapter 116 (2020). Pub L No. 116-36, 134 Stat 281. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748

5. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Provider Relief Fund: general information. US Department of Health & Human Services. June 25, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/cares-act-provider-relief-fund/general-information/index.html

6. Hospitals and health systems face unprecedented financial pressures due to COVID-19. American Hospital Association. May 2020. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/aha-covid19-financial-impact-0520-FINAL.pdf

7. Birkmeyer J, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

1. COVID-19: ways to prepare your children’s hospital now. Children’s Hospital Association. March 12, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Newsroom/Childrens-Hospitals-Today/Articles/2020/03/COVID-19-11-Ways-to-Prepare-Your-Hospital-Now

2. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

3. Oseran AS, Nash D, Kim C, et al. Changes in hospital admissions for urgent conditions during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(8):327-328. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.43837

4. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the CARES Act. 15 USC Chapter 116 (2020). Pub L No. 116-36, 134 Stat 281. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748

5. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Provider Relief Fund: general information. US Department of Health & Human Services. June 25, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/cares-act-provider-relief-fund/general-information/index.html

6. Hospitals and health systems face unprecedented financial pressures due to COVID-19. American Hospital Association. May 2020. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/aha-covid19-financial-impact-0520-FINAL.pdf

7. Birkmeyer J, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Readmissions Following Hospitalization for Infection in Children With or Without Medical Complexity

Hospitalizations for infections are common in children, with respiratory illnesses, including pneumonia and bronchiolitis, among the most prevalent indications for hospitalization.1,2 Infections are also among the most frequent indications for all-cause readmissions and for potentially preventable readmissions in children.3-5 Beyond hospital resource use, infection hospitalizations and readmissions represent a considerable cause of life disruption for patients and their families.6,7 While emerging evidence supports shortened durations of parenteral antibiotics before transitioning to oral therapy for some infections (eg, pyelonephritis, osteomyelitis),8-10 other infections may require extended treatment courses for weeks. The risk of adverse outcomes (eg, complications of medical treatment, readmission risk) and burdens placed on patients and their families may therefore differ across infection types and extend well beyond the immediate hospitalization.

Although infections are common and pediatric providers are expected to have proficiency in managing infections, substantial variation in the management of common pediatric infections exists and is associated with adverse hospitalization outcomes, including increased readmission risk and healthcare costs.11-18 Potentially avoidable resource use associated with hospital readmission from infection has led to adoption of hospital-level readmission metrics as indicators of the quality of healthcare delivery. For example, the Pediatric Quality Measures Program, established by the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009, has prioritized measurement of readmissions following hospitalization for lower respiratory tract infection.19 With government agencies increasingly using readmission metrics to assess quality of healthcare delivery, developing metrics that focus on these resource-intensive conditions is essential.

Because infections are a common and costly indication for hospital resource use and because substantial variation in management has been observed, promoting a broader understanding of infection-specific readmission rates is important for prioritizing readmission-reduction opportunities in children. This study’s objectives were the following: (1) to describe the prevalence and characteristics of infection hospitalizations in children and their associated readmissions and (2) to estimate the number of readmissions avoided and costs saved if all hospitals achieved the 10th percentile of the hospitals’ risk-adjusted readmission rate (ie, readmission benchmark).

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis using the 2014 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD).20 The 2014 NRD is an administrative database that contains information on inpatient stays from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2014, for all payers and allows for weighted national estimates of readmissions for all US individuals. Data within NRD are aggregated from 22 geographically diverse states representing approximately one-half of the US population. NRD contains deidentified patient-level data with unique verified patient identifiers to track individuals within and across hospitals in a state. However, AHRQ guidelines specify that NRD cannot be used for reporting hospital-specific readmission rates. Thus, for the current study, the Inpatient Essentials (Children’s Hospital Association), or IE, database was used to measure hospital-level readmission rates and to distinguish benchmark readmission rates for individual infection diagnoses.21 The IE database is composed of 90 children’s hospitals distributed throughout all regions of the United States. The inclusion of free-standing children’s hospitals and children’s hospitals within adult hospitals allows for comparisons and benchmarking across hospitals on multiple metrics, including readmissions.

Study Population

Children 0 to 17 years of age with a primary diagnosis at the index admission for infection between January 1, 2014, and November 30, 2014, were included. The end date of November 30, 2014, allowed for a full 30-day readmission window for all index admissions. We excluded index admissions that resulted in transfer to another acute care hospital or in-hospital mortality. Additionally, we excluded index admissions of children who had hematologic or immunologic conditions, malignancy, or history of bone marrow and solid-organ transplant, using the classification system for complex chronic conditions (CCCs) from Feudtner et al.22 Due to the high likelihood of immunosuppression in patients with these conditions, children may have nuanced experiences with illness severity, trajectory, and treatment associated with infection that place them at increased risk for nonpreventable readmission.

Main Exposure

The main exposure was infection type during the index admission. Condition-specific index admissions were identified using AHRQ’s Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) categories.23 CCS is a classification schema that categorizes the greater than 14,000 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes and 3,900 ICD-9-CM procedure codes into clinically meaningful categories of 295 diagnosis (including mental health codes and E-codes) and 231 procedural groupings. Twenty-two groupings indicative of infection were distinguished and used for the current study. Examples of infections included aspiration pneumonia, pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and sexually transmitted infection. We combined related CCS categories when possible for ease of interpretation and presentation of data (Appendix Table 1).

Main Outcome Measure

The main outcome measure was 30-day hospital readmission. Readmission was defined as all-cause, unplanned admission within 30 days following discharge from a preceding hospitalization. Planned hospital readmissions were identified and excluded using methods from AHRQ’s Pediatric All-Condition Readmission Measure.24 We defined a same-cause return as a return with the same CCS infection category as the index admission. Costs associated with readmissions were estimated from charges using hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratios provided with NRD.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Patient demographic characteristics included age at index admission (<1 year, 1-5 years, 6-9 years, 10-14 years, and 15-18 years), sex, payer (ie, government, private, other), and discharge disposition (ie, routine, home health, other). We assessed all patients for medical complexity, as defined by the presence of at least one CCC, and we reported the categories of CCCs by organ system involved.22 Otherwise, patients were identified as without medical complexity.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized continuous variables with medians and interquartile ranges and categorical variables with frequencies and percentages. To develop benchmark readmission rates for each infection type, we used generalized linear mixed models with random intercepts for each hospital in the IE database. For each infection type, the benchmark readmission rate was defined as the 10th percentile of hospitals’ risk-adjusted readmission rates. The 10th percentile was chosen to identify the best performing 10% of hospitals (ie, hospitals with the lowest readmission rates). Because children with medical complexity account for a large proportion of hospital resource use and are at high risk for readmission,4,25 we developed benchmarks stratified by presence/absence of a CCC (ie, with complexity vs without complexity). Models were adjusted for severity of illness using the Hospitalization Resource Intensity Score for Kids (H-RISK),26 a scoring system that assigns relative weights for each All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Group (3M Corporation) and severity of illness level, and each hospital’s risk-adjusted readmission rate was determined.

With use of weights to achieve national estimates of index admissions and readmissions, we determined the number of potentially avoidable readmissions by calculating the number of readmissions observed in the NRD that would not occur if all hospitals achieved readmission rates equal to the 10th percentile. Avoidable costs were estimated by multiplying the number of potentially avoidable readmissions by the mean cost of a readmission for infections of that type. Estimates of avoidable readmissions and costs were stratified by medical complexity. In addition to describing estimates at the 10th percentile benchmark, we similarly developed estimates of potentially avoidable readmissions and avoidable costs for the 5th and 25th percentiles, which are presented within Appendix Table 2 (children without complexity) and Appendix Table 3 (children with complexity).

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and P values <.001 were considered statistically significant due to the large sample size. The Office of Research Integrity at Children’s Mercy Hospital deemed this study exempt from institutional board review.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Population

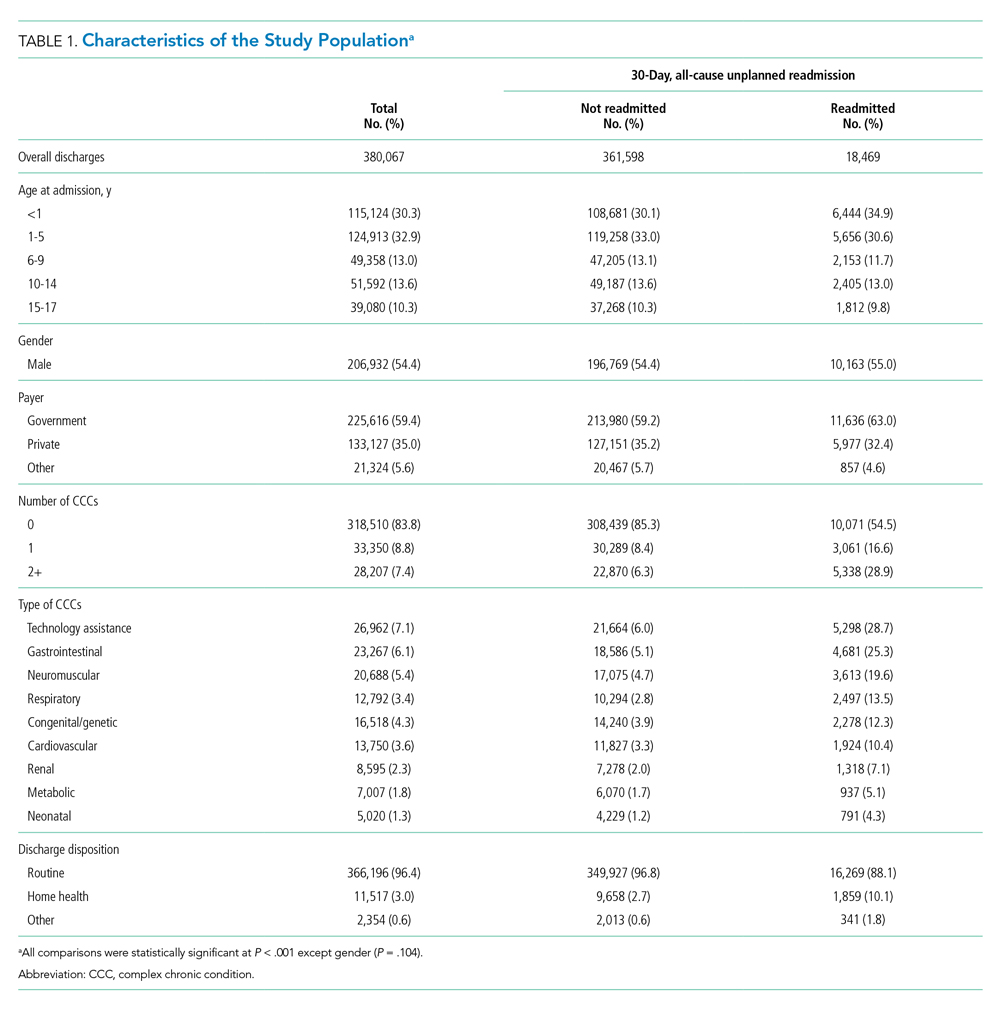

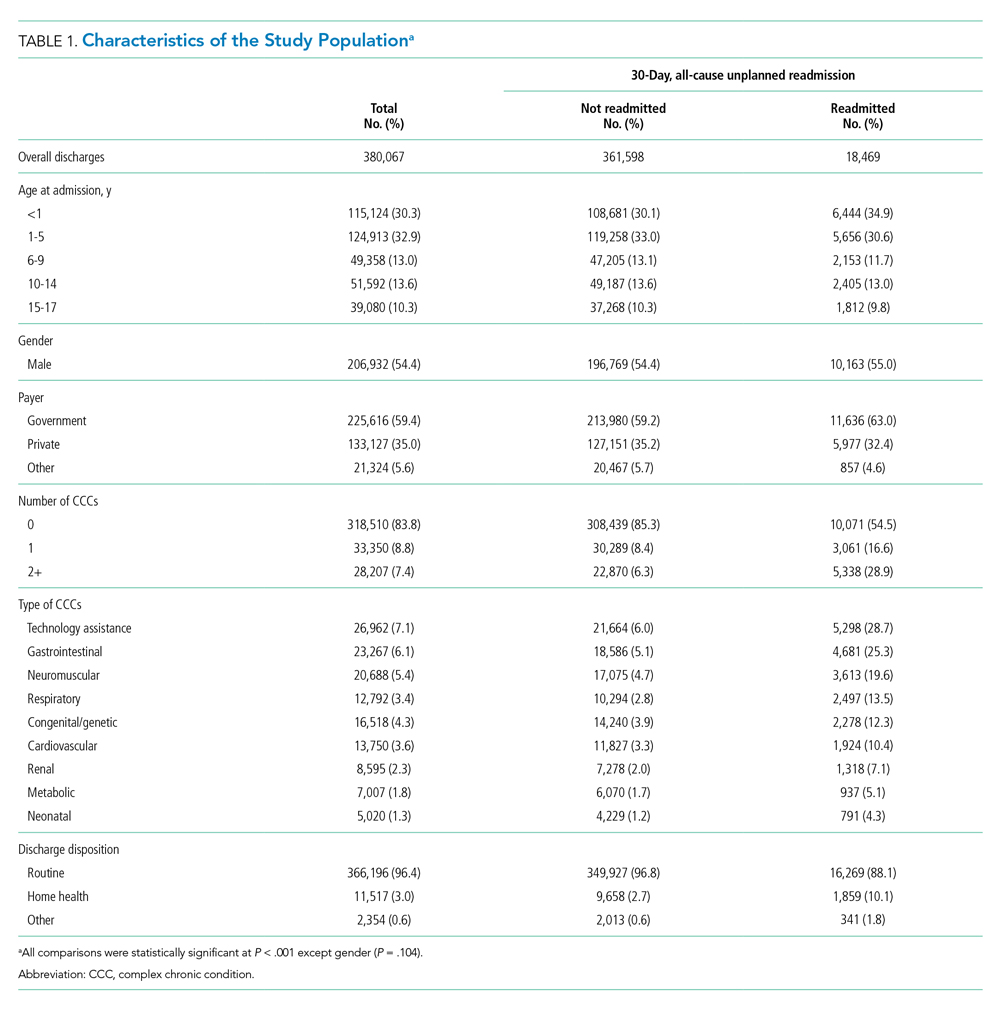

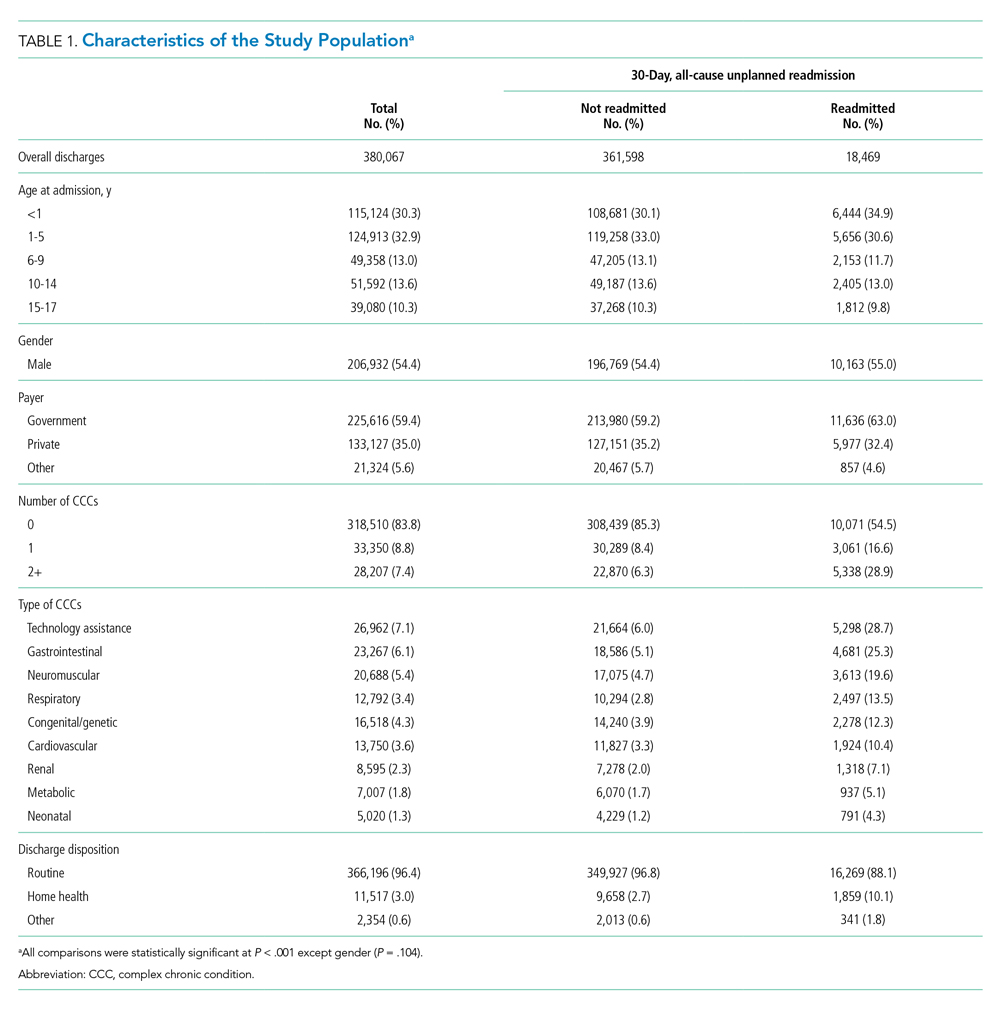

The study included 380,067 index admissions for infection and an accompanying 18,469 unplanned all-cause readmissions over the 30 days following discharge (readmission rate, 4.9%; Table 1). Children ages 1 to 5 years accounted for the largest percentage (32.9%) of index hospitalizations, followed by infants younger than 1 year (30.3%). The readmission rate by age group was highest for infants younger than 1 year, compared with rates among all other age groups (5.6% among infants < 1 year vs 4.4%-4.7% for other age groups; P < .001). In the overall cohort, 16.2% of admissions included patients with a CCC. Children with medical complexity had higher readmission rates than those without medical complexity (no CCC, 3.2%; 1 CCC, 9.2%; 2+ CCCs, 18.9%). A greater percentage of children experiencing a readmission had government insurance (63.0% vs 59.2%; P < .001) and received home health nursing (10.1% vs 2.7%; P < .001) following the index encounter.

Children Without Complexity

Index Admissions and 30-day Readmissions

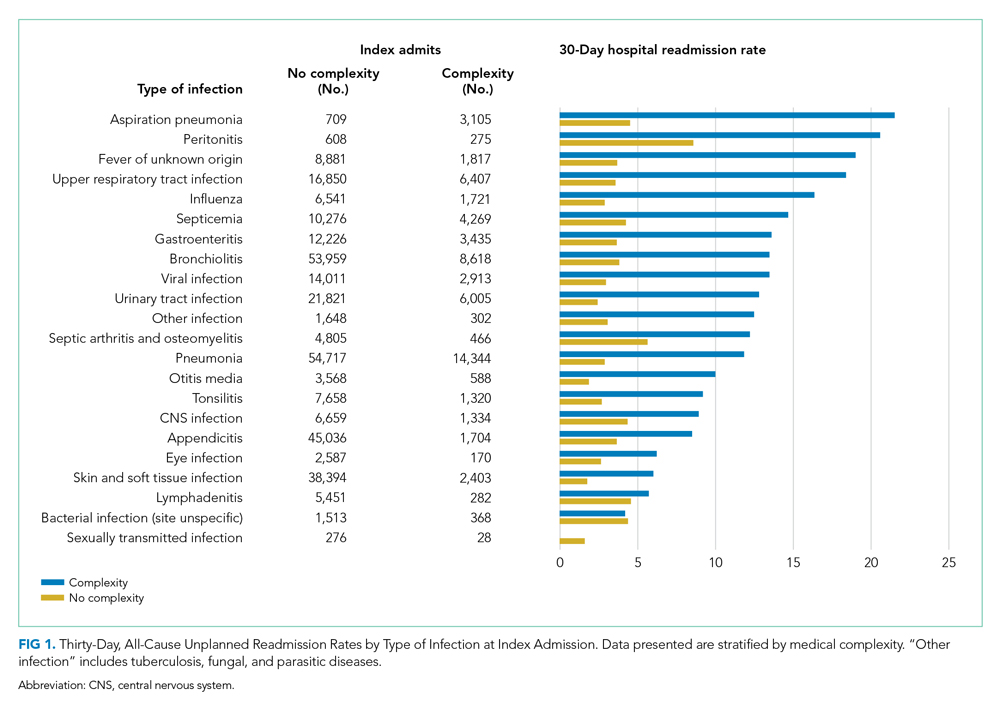

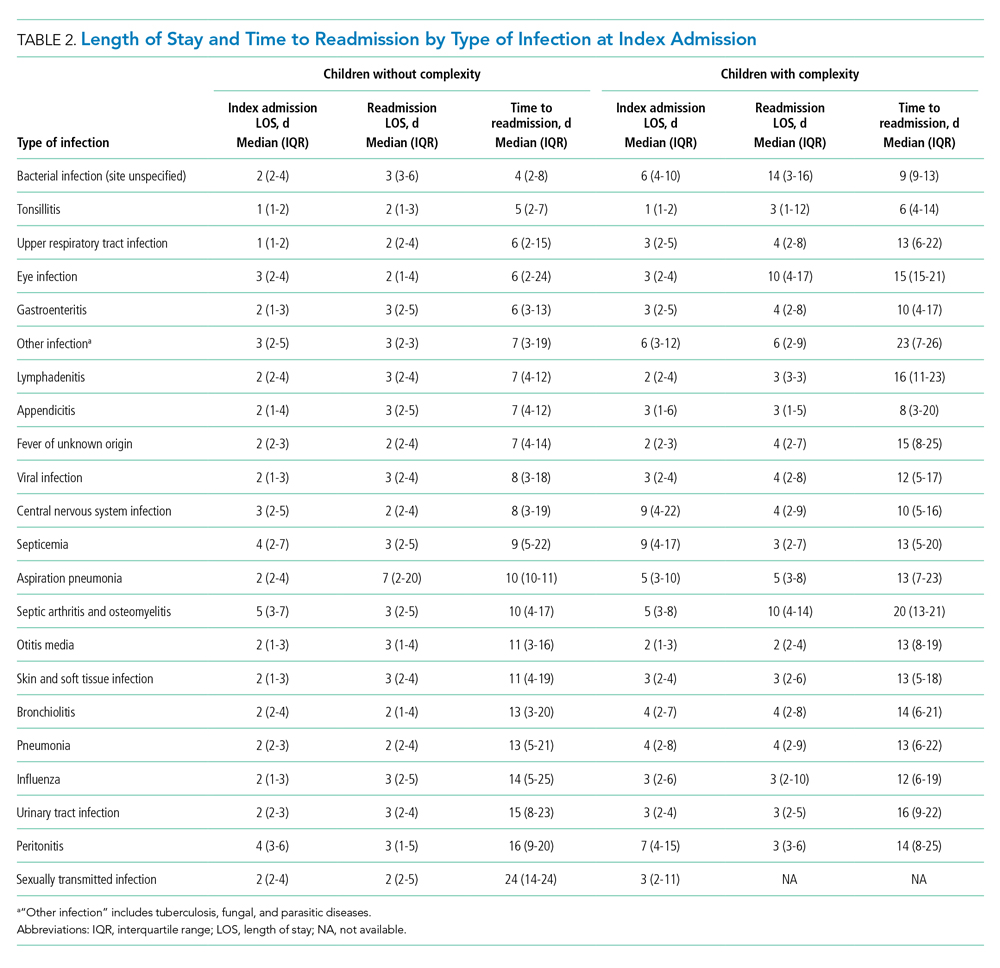

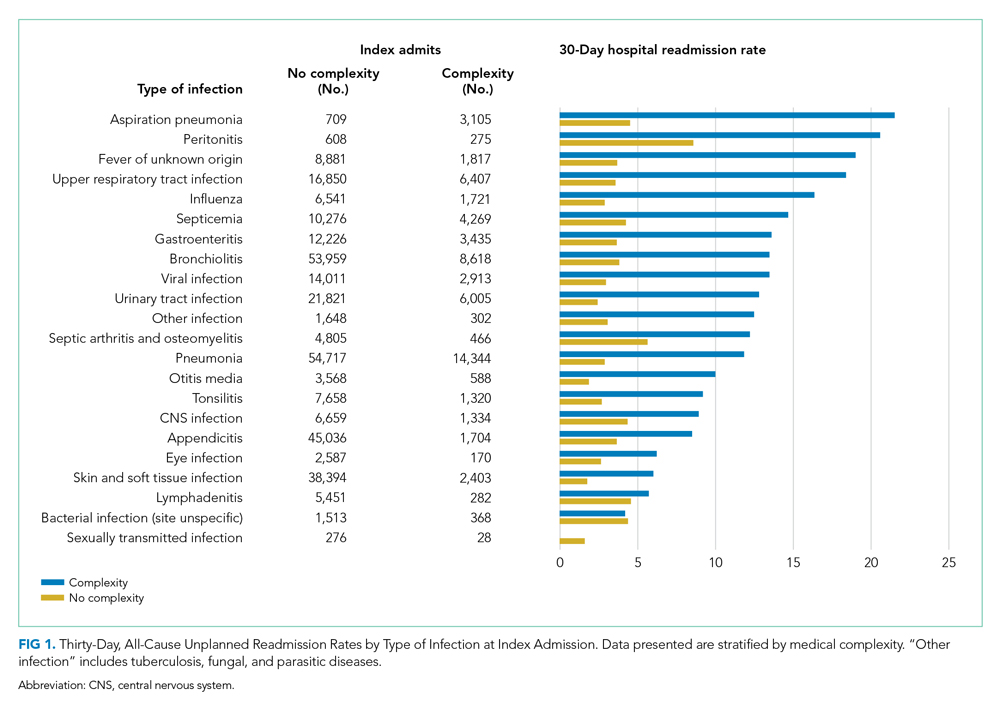

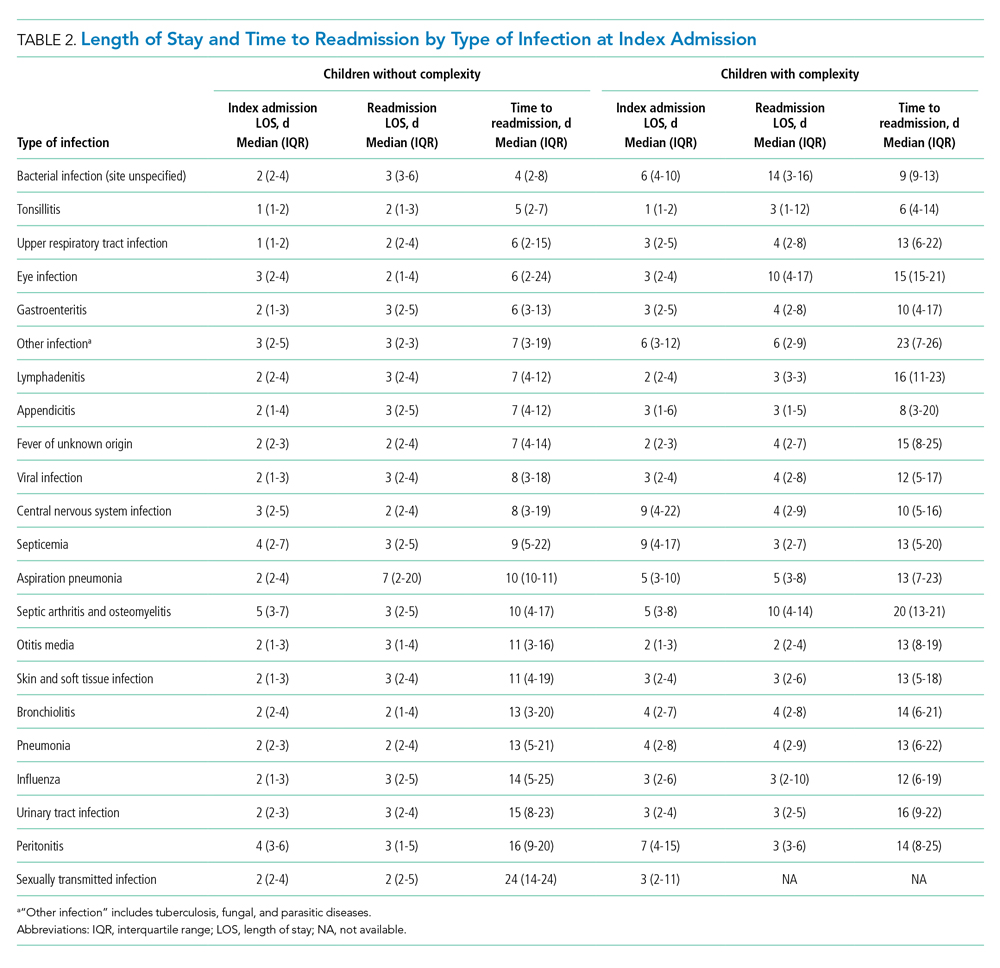

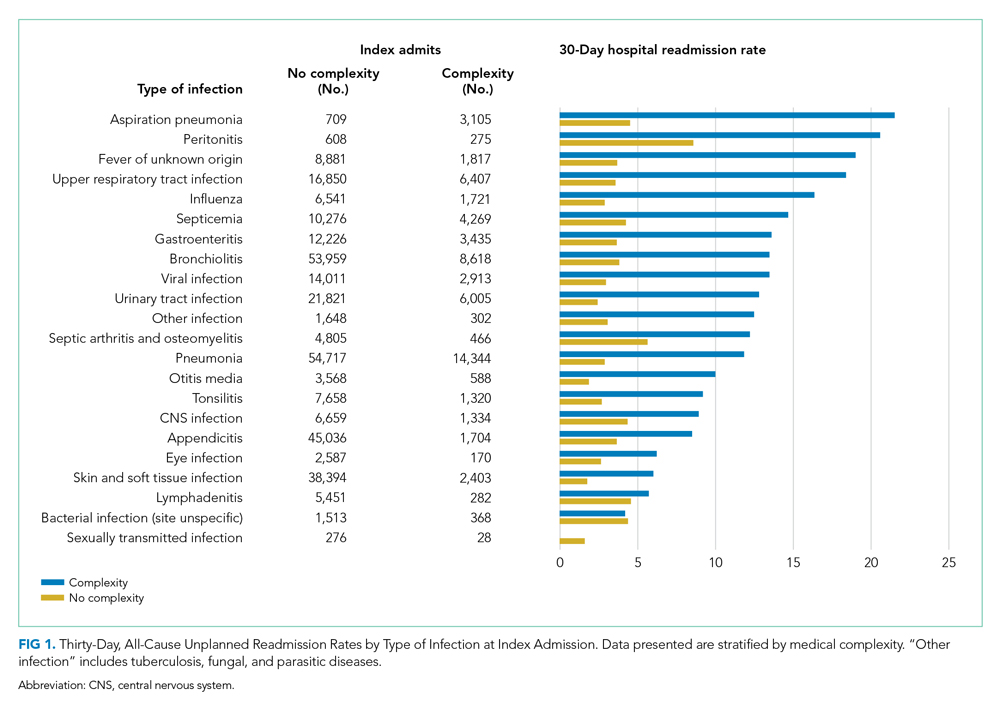

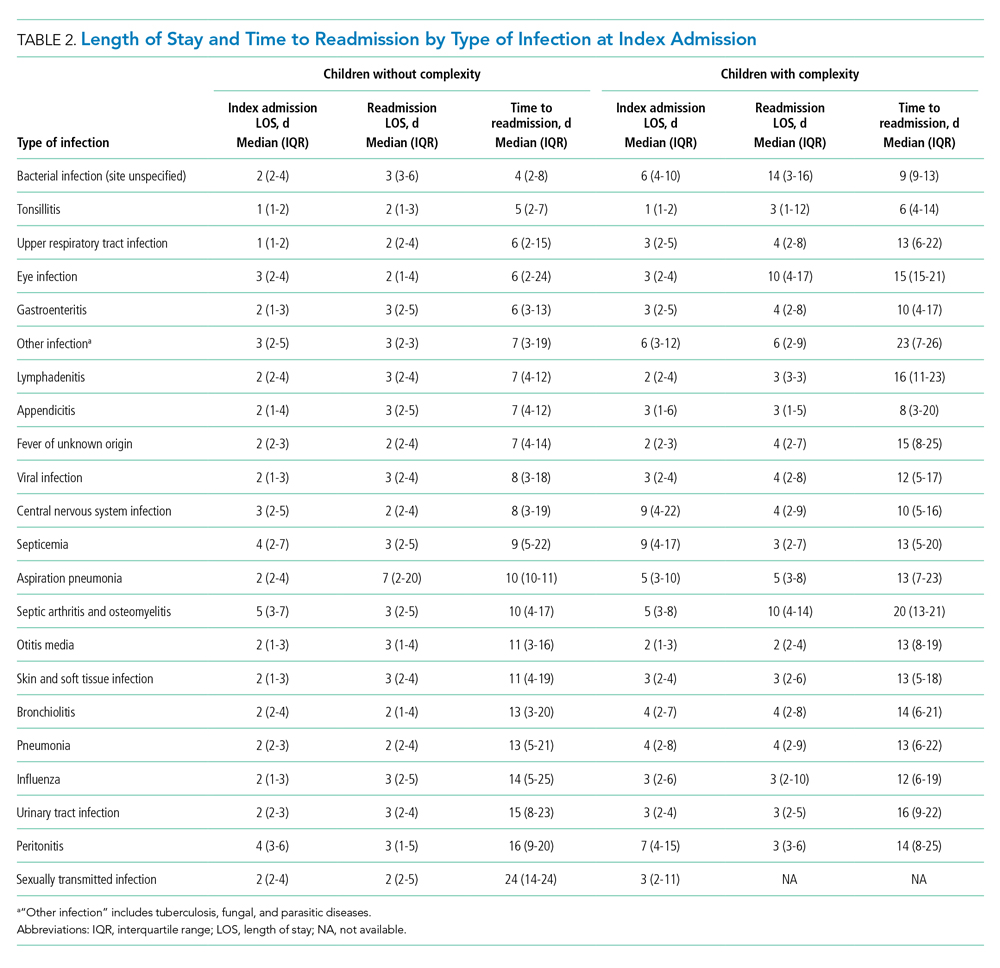

Among patients without medical complexity, index admissions occurred most frequently for pneumonia (n = 54,717), bronchiolitis (n = 53,959), and appendicitis (n = 45,036) (Figure 1). The median length of stay (LOS) for index admissions ranged from 1 to 5 days (Table 2), with septic arthritis and osteomyelitis having the longest median LOS at 5 (IQR, 3-7) days.

Thirty-day readmission rates varied substantially by infection at the index admission (range, 1.5% for sexually transmitted infection to 8.6% for peritonitis) (Figure 1). The median LOS for 30-day readmissions varied from 2 to 7 days (Table 2), while the median number of days to readmission varied substantially by infection type (range, 4 days for bacterial infection [site unspecified] to 24 days for sexually transmitted infections). Among the top five indications for admission for children without complexity, 14.9% to 52.8% of readmissions were for the same cause as the index admission; however, many additional returns were likely related to the index admission (Appendix Table 4). For example, among other return reasons, an additional 992 (61.7%) readmissions following appendicitis hospitalizations were for complications of surgical procedures or medical care, peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, and abdominal pain.

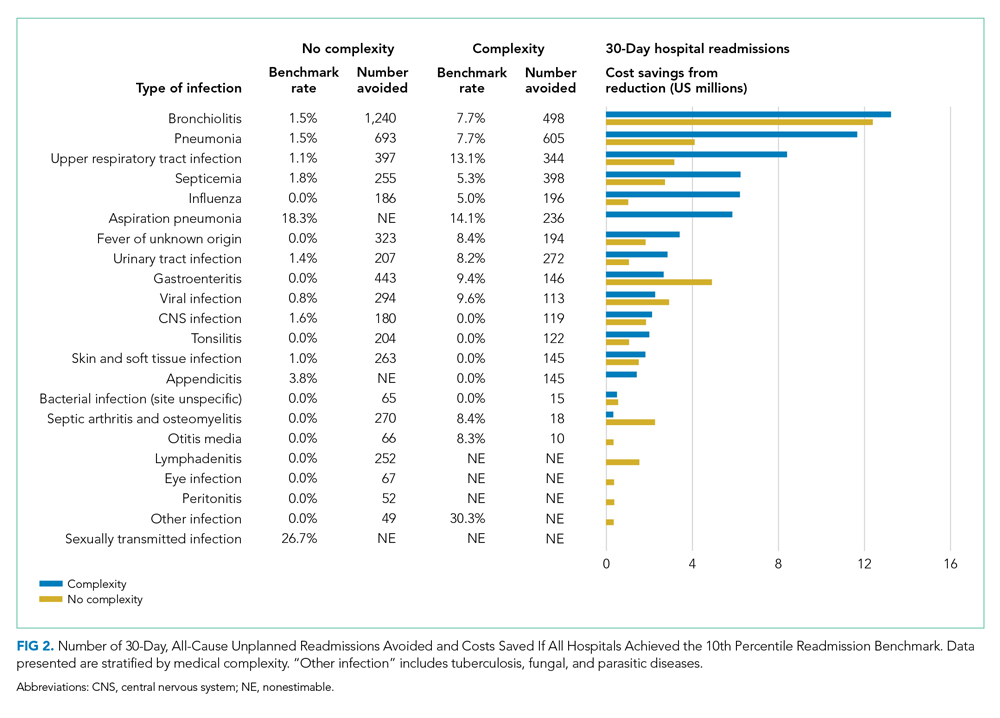

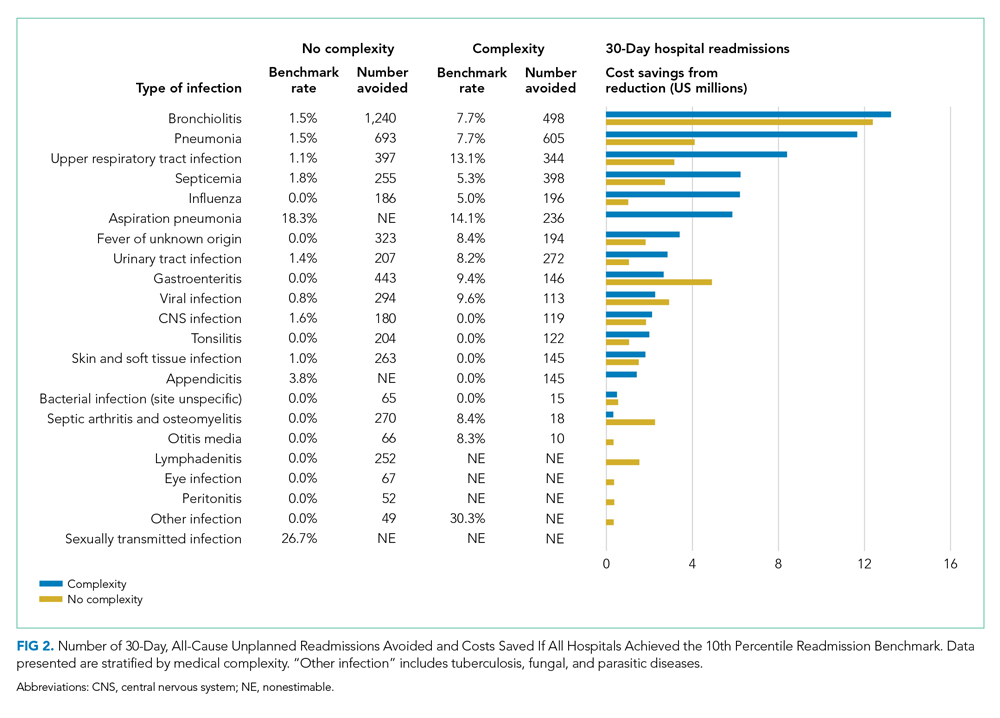

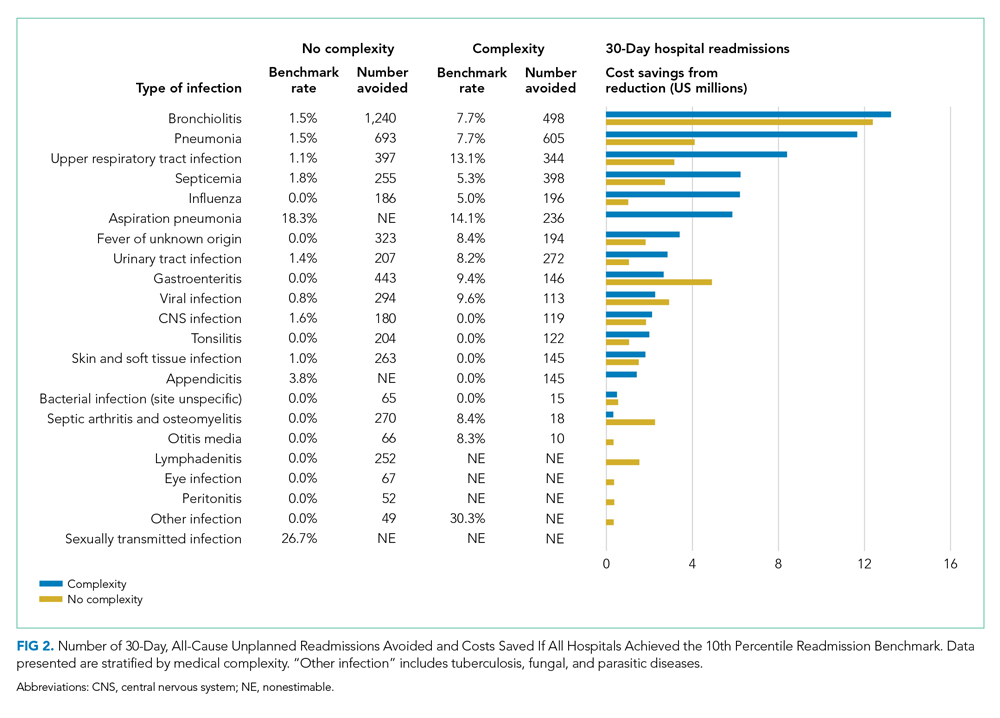

Impact of Achieving Readmission Benchmarks

Among children without complexity, readmission benchmarks (ie, the 10th percentile of readmission rates across hospitals) ranged from 0% to 26.7% (Figure 2). An estimated 54.7% of readmissions (n = 5,507) could potentially be reduced if hospitals achieved infection-specific benchmark readmission rates, which could result in an estimated $44.5 million in savings. Pneumonia, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, and upper respiratory tract infections were among conditions with the greatest potential reductions in readmissions and costs if a 10th percentile benchmark was achieved.

Children With Medical Complexity

Index Admissions and 30-day Readmissions

Among patients with complexity, index admissions occurred most frequently for pneumonia (n = 14,344), bronchiolitis (n = 8,618), and upper respiratory tract infection (n = 6,407) (Figure 1). The median LOS for index admissions ranged from 1 to 9 days (Table 2), with septicemia and CNS infections having the longest median LOS at 9 days.

Thirty-day readmission rates varied substantially by the type of infection at the index admission (range, 0% for sexually transmitted infection to 21.6% for aspiration pneumonia) (Figure 1). The median LOS for 30-day readmissions varied from 2 to 14 days (Table 2), and the median number of days to readmission varied substantially by infection type (range, 6 days for tonsillitis to 23 days for other infection). Among the top five indications for admission for medically complex children, 8% to 40.4% of readmissions were for the same cause as the index admission (Appendix Table 4). As with the children without complexity, additional returns were likely related to the index admission.

Impact of Achieving Readmission Benchmarks

Among children with medical complexity, readmission benchmarks ranged from 0% to 30.3% (Figure 2). An estimated 42.6% of readmissions (n = 3,576) could potentially be reduced if hospitals achieved infection-specific benchmark readmission rates, which could result in an estimated $70.8 million in savings. Pneumonia, bronchiolitis, septicemia, and upper respiratory tract infections were among conditions with the greatest potential reductions in readmissions and costs if the benchmarks were achieved.

DISCUSSION

The current study uncovered new findings regarding unplanned readmissions following index infection hospitalizations for children. In particular, readmission rates and time to readmission varied substantially by infection subtype. The study also identified priority infections and unique considerations for children with CCCs, all of which may help maximize the value of readmission metrics aimed at advancing hospital quality and reducing costs for infection hospitalizations in children. If all hospitals achieved the readmission rates of the best performing hospitals, 42.6% to 54.7% fewer readmissions could be realized with associated cost savings.

Nationally, studies have reported 30-day, all-cause unplanned readmission rates of 6.2% to 10.3%.5,27 In our current study we observed an overall readmission rate of 4.9% across all infectious conditions; however, readmission rates varied substantially by condition, with upper and lower respiratory tract infections, septicemia, and gastroenteritis among infections with the greatest number of potentially avoidable readmissions based on achievement of readmission benchmarks. Currently, pediatric-specific all-cause and lower respiratory tract infection readmission metrics have been developed with the aim of improving quality of care and reducing healthcare expenditures.28 Future readmission studies and metrics may prioritize conditions such as septicemia, gastroenteritis, and other respiratory tract infections. Our current study demonstrated that many readmissions following infection hospitalizations were associated with the same CCS category or within a related CCS category (eg, complications of surgical procedures or medical care, appendicitis, peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, and abdominal pain constituted the top five indications for readmission for appendicitis, whereas respiratory illnesses constituted the top five indications for readmissions for pneumonia). While this current study cannot clarify this relationship further, and the “avoidability” of unplanned readmissions is debated,29-31 our findings suggest that future investigations might focus on identifying whether condition-specific interventions during the index admission could mitigate some readmissions.

While the LOS of the index admission and the readmission were similar for most infection subtypes, we observed substantial variability in the temporal risk for readmission by infection subtype. Our observations complement studies exploring the timing of readmissions for other pediatric conditions.32-34 In particular, our findings further highlight that the composition and interaction of factors influencing infection readmissions may vary by condition. Infections represent a diverse group of conditions, with treatment courses that vary in need for parenteral antibiotics, ability to tailor treatment based on organism and susceptibilities, and length of treatment. While treatment for some infections may be accomplished, or nearly accomplished, prior to discharge, other infections (eg, osteomyelitis) may require prolonged treatment, shifting the burden of management and monitoring to patients and their families, which along with the timeliness and adequacy of outpatient follow-up, may modify an individual’s readmission risk. Consequently, a “one-size fits all” approach to discharge counseling may not be successful across all conditions. Our study lays the groundwork for how these temporal relationships may be used by clinicians to counsel families regarding the likely readmission timeframe, based on infection, and to establish follow-up appointments ahead of the infection-specific “readmission window,” which may allow outpatient providers to intervene when readmission risk is greatest.

Consistent with prior literature, children with medical complexity in our study had increased frequency of 30-day, all-cause unplanned readmissions and LOS, compared with peers who did not have complexity.5 Readmission rates following hospitalizations for aspiration pneumonia were comparable to those reported by Thompson et al in their study examining rates of pneumonia in children with neurologic impairment.35 In our current study, nearly 96% of readmissions following aspiration pneumonia hospitalizations were for children with medical complexity, and more than 58% of these readmissions were for aspiration pneumonia or respiratory illness. Future investigations should seek to explore factors contributing to readmissions in children with medical complexity and to evaluate whether interventions such as postdischarge coaching or discharge bundles could assist with reductions in healthcare resource use.36,37

Despite a lack of clear association between readmissions and quality of care for children,38 readmissions rates continue to be used as a quality measure for hospitalized patients. Within our present study, we found that achieving benchmark readmission rates for infection hospitalizations could lead to substantial reductions in readmissions; however, these reductions were seen across this relatively similar group of infection diagnoses, and hospitals may face greater challenges when attempting to achieve a 10th percentile readmission benchmark across a more expansive set of diagnoses. Despite these challenges, understanding the intricacies of readmissions may lead to improved readmission metrics and the systematic identification of avoidable readmissions, the goal of which is to enhance the quality of healthcare for hospitalized children.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. We defined our readmission benchmark at the 10th percentile using the IE database. Because an estimated 70% of hospitalizations for children occur within general hospitals,39 we believe that our use of the IE database allowed for increased generalizability, though the broadening of our findings to nonacademic hospital settings may be less reliable. While we describe the 10th percentile readmission benchmark here, alternative benchmarks would result in different estimates of avoidable readmissions and associated readmission costs (Appendix Tables 2 and 3). The IE and NRD databases do not distinguish intensive care use. We tried to address this limitation through model adjustments using H-RISK, which is particularly helpful for adjusting for NICU admissions through use of the 27 All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Groups for neonatal conditions. Additionally, the NRD uses state-level data to derive national estimates and is not equipped to measure readmissions to hospitals in a different state, distinguish patient deaths occurring after discharge, or to examine the specific indication for readmission (ie, unable to assess if the readmission is related to a complication of the treatment plan, progression of the illness course, or for an unrelated reason). While sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors may affect readmissions, the NRD does not contain information on patients’ race/ethnicity, family/social attributes, or postdischarge follow-up health services, which are known to influence the need for readmission.

Despite these limitations, this study highlights future areas for research and potential opportunities for reducing readmission following infection hospitalizations. First, identifying hospital- and systems-based factors that contribute to readmission reductions at the best-performing hospitals may identify opportunities for hospitals with the highest readmission rates to achieve the rates of the best-performing hospitals. Second, conditions such as upper and lower respiratory tract infections, along with septicemia and gastroenteritis, may serve as prime targets for future investigation based on the estimated number of avoidable readmissions and potential cost savings associated with these conditions. Finally, future investigations that explore discharge counseling and follow-up tailored to the infection-specific temporal risk and patient complexity may identify opportunities for further readmission reductions.

CONCLUSION

Our study provides a broad look at readmissions following infection hospitalizations and highlights substantial variation in readmissions based on infection type. To improve hospital resource use for infections, future preventive measures could prioritize children with complex chronic conditions and those with specific diagnoses (eg, upper and lower respiratory tract infections).

Disclaimer

This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by, NIH or the US government.

1. Keren R, Luan X, Localio R, et al; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network. Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1155-1164. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1266

2. Van Horne B, Netherton E, Helton J, Fu M, Greeley C. The scope and trends of pediatric hospitalizations in Texas, 2004-2010. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(7):390-398. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2014-0105

3. Neuman MI, Hall M, Gay JC, et al. Readmissions among children previously hospitalized with pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):100-109. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0331

4. Gay JC, Hain PD, Grantham JA, Saville BR. Epidemiology of 15-day readmissions to a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):e1505-e1512. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1737

5. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.188351

6. Shudy M, de Almeida ML, Ly S, et al. Impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families: a systematic literature review. Pediatrics. 2006;118(suppl 3):S203-S218. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-0951b

7. Rennick JE, Johnston CC, Dougherty G, Platt R, Ritchie JA. Children’s psychological responses after critical illness and exposure to invasive technology. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23(3):133-144. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200206000-00002

8. Michael M, Hodson EM, Craig JC, Martin S, Moyer VA. Short versus standard duration oral antibiotic therapy for acute urinary tract infection in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1):CD003966. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003966

9. Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Sadaka Y, Ben-Shimol S, Bar-Ziv J, Dagan R. Short-course antibiotic treatment for community-acquired alveolar pneumonia in ambulatory children: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(2):136-142. https://doi.org/10.1097/inf.0000000000000023

10. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(2):120-128. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2822

11. Markham JL, Hall M, Bettenhausen JL, Myers AL, Puls HT, McCulloh RJ. Variation in care and clinical outcomes in children hospitalized with orbital cellulitis. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8(1):28-35. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0040

12. Neubauer HC, Hall M, Wallace SS, Cruz AT, Queen MA, Foradori DM, Aronson PL, Markham JL, Nead JA, Hester GZ, McCulloh RJ, Lopez MA. Variation in diagnostic test use and associated outcomes in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome at children’s hospitals. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8(9):530-537. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2018-0032

13. Aronson PL, Thurm C, Alpern ER, et al; Febrile Young Infant Research Collaborative. Variation in care of the febrile young infant <90 days in US pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):667-677. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1382

14. Florin TA, French B, Zorc JJ, Alpern ER, Shah SS. Variation in emergency department diagnostic testing and disposition outcomes in pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):237-244. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0179

15. Brogan TV, Hall M, Williams DJ, et al. Variability in processes of care and outcomes among children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(10):1036-1041. https://doi.org/10.1097/inf.0b013e31825f2b10

16. Leyenaar JK, Lagu T, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Variation in resource utilization for the management of uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia across community and children’s hospitals. J Pediatr. 2014;165(3):585-591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.04.062

17. Knapp JF, Simon SD, Sharma V. Variation and trends in ED use of radiographs for asthma, bronchiolitis, and croup in children. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):245-252. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2830

18. Rice-Townsend S, Barnes JN, Hall M, Baxter JL, Rangel SJ. Variation in practice and resource utilization associated with the diagnosis and management of appendicitis at freestanding children’s hospitals: implications for value-based comparative analysis. Ann Surg. 2014;259(6):1228-1234. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000246

19. Pediatric Quality Measures Program (PQMP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed March 1, 2019. https://www.ahrq.gov/pqmp/index.html

20. NRD Database Documentation. Accessed June 1, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nrd/nrddbdocumentation.jsp

21. Inpatient Essentials. Children’s Hospitals Association. Accessed August 1, 2018. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Programs-and-Services/Data-Analytics-and-Research/Pediatric-Analytic-Solutions/Inpatient-Essentials

22. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-199

23. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. March 2017. Accessed August 2, 2018. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp

24. NQF: Quality Positioning System. National Quality Forum. Accessed September 3, 2018. http://www.qualityforum.org/QPS/QPSTool.aspx

25. Berry JG, Ash AS, Cohen E, Hasan F, Feudtner C, Hall M. Contributions of children with multiple chronic conditions to pediatric hospitalizations in the United States: a retrospective cohort analysis. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(7):365-372. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0179

26. Richardson T, Rodean J, Harris M, Berry J, Gay JC, Hall M. Development of Hospitalization Resource Intensity Scores for Kids (H-RISK) and comparison across pediatric populations. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(9):602-608. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2948

27. Auger KA, Mueller EL, Weinberg SH, et al. A validated method for identifying unplanned pediatric readmission. J Pediatr. 2016;170:105-12.e122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.051

28. NQF: Pediatric Measures Final Report. National Quality Forum. June 2016. Accessed January 24, 2019. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2016/06/Pediatric_Measures_Final_Report.aspx

29. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of early readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0820

30. Toomey SL, Peltz A, Loren S, et al. Potentially preventable 30-day hospital readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20154182. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4182

31. Jonas JA, Devon EP, Ronan JC, et al. Determining preventability of pediatric readmissions using fault tree analysis. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):329-335. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2555

32. Bucholz EM, Gay JC, Hall M, Harris M, Berry JG. Timing and causes of common pediatric readmissions. J Pediatr. 2018;200:240-248.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.04.044

33. Morse RB, Hall M, Fieldston ES, et al. Children’s hospitals with shorter lengths of stay do not have higher readmission rates. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1034-8.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.083

34. Kenyon CC, Melvin PR, Chiang VW, Elliott MN, Schuster MA, Berry JG. Rehospitalization for childhood asthma: timing, variation, and opportunities for intervention. J Pediatr. 2014;164(2):300-305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.003

35. Thomson J, Hall M, Ambroggio L, et al. Aspiration and non-aspiration pneumonia in hospitalized children with neurologic impairment. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20151612. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1612

36. Coller RJ, Klitzner TS, Lerner CF, et al. Complex Care hospital use and postdischarge coaching: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20174278. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4278

37. Stephens JR, Kimple KS, Steiner MJ, Berry JG. Discharge interventions and modifiable risk factors for preventing hospital readmissions in children with medical complexity. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12(4):290-297. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574887112666170816144455

38. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3527

39. Leyenaar JK, Ralston SL, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Mangione-Smith R, Lindenauer PK. Epidemiology of pediatric hospitalizations at general hospitals and freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):743-749. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2624

Hospitalizations for infections are common in children, with respiratory illnesses, including pneumonia and bronchiolitis, among the most prevalent indications for hospitalization.1,2 Infections are also among the most frequent indications for all-cause readmissions and for potentially preventable readmissions in children.3-5 Beyond hospital resource use, infection hospitalizations and readmissions represent a considerable cause of life disruption for patients and their families.6,7 While emerging evidence supports shortened durations of parenteral antibiotics before transitioning to oral therapy for some infections (eg, pyelonephritis, osteomyelitis),8-10 other infections may require extended treatment courses for weeks. The risk of adverse outcomes (eg, complications of medical treatment, readmission risk) and burdens placed on patients and their families may therefore differ across infection types and extend well beyond the immediate hospitalization.

Although infections are common and pediatric providers are expected to have proficiency in managing infections, substantial variation in the management of common pediatric infections exists and is associated with adverse hospitalization outcomes, including increased readmission risk and healthcare costs.11-18 Potentially avoidable resource use associated with hospital readmission from infection has led to adoption of hospital-level readmission metrics as indicators of the quality of healthcare delivery. For example, the Pediatric Quality Measures Program, established by the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009, has prioritized measurement of readmissions following hospitalization for lower respiratory tract infection.19 With government agencies increasingly using readmission metrics to assess quality of healthcare delivery, developing metrics that focus on these resource-intensive conditions is essential.

Because infections are a common and costly indication for hospital resource use and because substantial variation in management has been observed, promoting a broader understanding of infection-specific readmission rates is important for prioritizing readmission-reduction opportunities in children. This study’s objectives were the following: (1) to describe the prevalence and characteristics of infection hospitalizations in children and their associated readmissions and (2) to estimate the number of readmissions avoided and costs saved if all hospitals achieved the 10th percentile of the hospitals’ risk-adjusted readmission rate (ie, readmission benchmark).

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis using the 2014 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD).20 The 2014 NRD is an administrative database that contains information on inpatient stays from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2014, for all payers and allows for weighted national estimates of readmissions for all US individuals. Data within NRD are aggregated from 22 geographically diverse states representing approximately one-half of the US population. NRD contains deidentified patient-level data with unique verified patient identifiers to track individuals within and across hospitals in a state. However, AHRQ guidelines specify that NRD cannot be used for reporting hospital-specific readmission rates. Thus, for the current study, the Inpatient Essentials (Children’s Hospital Association), or IE, database was used to measure hospital-level readmission rates and to distinguish benchmark readmission rates for individual infection diagnoses.21 The IE database is composed of 90 children’s hospitals distributed throughout all regions of the United States. The inclusion of free-standing children’s hospitals and children’s hospitals within adult hospitals allows for comparisons and benchmarking across hospitals on multiple metrics, including readmissions.

Study Population

Children 0 to 17 years of age with a primary diagnosis at the index admission for infection between January 1, 2014, and November 30, 2014, were included. The end date of November 30, 2014, allowed for a full 30-day readmission window for all index admissions. We excluded index admissions that resulted in transfer to another acute care hospital or in-hospital mortality. Additionally, we excluded index admissions of children who had hematologic or immunologic conditions, malignancy, or history of bone marrow and solid-organ transplant, using the classification system for complex chronic conditions (CCCs) from Feudtner et al.22 Due to the high likelihood of immunosuppression in patients with these conditions, children may have nuanced experiences with illness severity, trajectory, and treatment associated with infection that place them at increased risk for nonpreventable readmission.

Main Exposure

The main exposure was infection type during the index admission. Condition-specific index admissions were identified using AHRQ’s Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) categories.23 CCS is a classification schema that categorizes the greater than 14,000 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes and 3,900 ICD-9-CM procedure codes into clinically meaningful categories of 295 diagnosis (including mental health codes and E-codes) and 231 procedural groupings. Twenty-two groupings indicative of infection were distinguished and used for the current study. Examples of infections included aspiration pneumonia, pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and sexually transmitted infection. We combined related CCS categories when possible for ease of interpretation and presentation of data (Appendix Table 1).

Main Outcome Measure

The main outcome measure was 30-day hospital readmission. Readmission was defined as all-cause, unplanned admission within 30 days following discharge from a preceding hospitalization. Planned hospital readmissions were identified and excluded using methods from AHRQ’s Pediatric All-Condition Readmission Measure.24 We defined a same-cause return as a return with the same CCS infection category as the index admission. Costs associated with readmissions were estimated from charges using hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratios provided with NRD.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Patient demographic characteristics included age at index admission (<1 year, 1-5 years, 6-9 years, 10-14 years, and 15-18 years), sex, payer (ie, government, private, other), and discharge disposition (ie, routine, home health, other). We assessed all patients for medical complexity, as defined by the presence of at least one CCC, and we reported the categories of CCCs by organ system involved.22 Otherwise, patients were identified as without medical complexity.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized continuous variables with medians and interquartile ranges and categorical variables with frequencies and percentages. To develop benchmark readmission rates for each infection type, we used generalized linear mixed models with random intercepts for each hospital in the IE database. For each infection type, the benchmark readmission rate was defined as the 10th percentile of hospitals’ risk-adjusted readmission rates. The 10th percentile was chosen to identify the best performing 10% of hospitals (ie, hospitals with the lowest readmission rates). Because children with medical complexity account for a large proportion of hospital resource use and are at high risk for readmission,4,25 we developed benchmarks stratified by presence/absence of a CCC (ie, with complexity vs without complexity). Models were adjusted for severity of illness using the Hospitalization Resource Intensity Score for Kids (H-RISK),26 a scoring system that assigns relative weights for each All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Group (3M Corporation) and severity of illness level, and each hospital’s risk-adjusted readmission rate was determined.

With use of weights to achieve national estimates of index admissions and readmissions, we determined the number of potentially avoidable readmissions by calculating the number of readmissions observed in the NRD that would not occur if all hospitals achieved readmission rates equal to the 10th percentile. Avoidable costs were estimated by multiplying the number of potentially avoidable readmissions by the mean cost of a readmission for infections of that type. Estimates of avoidable readmissions and costs were stratified by medical complexity. In addition to describing estimates at the 10th percentile benchmark, we similarly developed estimates of potentially avoidable readmissions and avoidable costs for the 5th and 25th percentiles, which are presented within Appendix Table 2 (children without complexity) and Appendix Table 3 (children with complexity).

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and P values <.001 were considered statistically significant due to the large sample size. The Office of Research Integrity at Children’s Mercy Hospital deemed this study exempt from institutional board review.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Population

The study included 380,067 index admissions for infection and an accompanying 18,469 unplanned all-cause readmissions over the 30 days following discharge (readmission rate, 4.9%; Table 1). Children ages 1 to 5 years accounted for the largest percentage (32.9%) of index hospitalizations, followed by infants younger than 1 year (30.3%). The readmission rate by age group was highest for infants younger than 1 year, compared with rates among all other age groups (5.6% among infants < 1 year vs 4.4%-4.7% for other age groups; P < .001). In the overall cohort, 16.2% of admissions included patients with a CCC. Children with medical complexity had higher readmission rates than those without medical complexity (no CCC, 3.2%; 1 CCC, 9.2%; 2+ CCCs, 18.9%). A greater percentage of children experiencing a readmission had government insurance (63.0% vs 59.2%; P < .001) and received home health nursing (10.1% vs 2.7%; P < .001) following the index encounter.

Children Without Complexity

Index Admissions and 30-day Readmissions

Among patients without medical complexity, index admissions occurred most frequently for pneumonia (n = 54,717), bronchiolitis (n = 53,959), and appendicitis (n = 45,036) (Figure 1). The median length of stay (LOS) for index admissions ranged from 1 to 5 days (Table 2), with septic arthritis and osteomyelitis having the longest median LOS at 5 (IQR, 3-7) days.

Thirty-day readmission rates varied substantially by infection at the index admission (range, 1.5% for sexually transmitted infection to 8.6% for peritonitis) (Figure 1). The median LOS for 30-day readmissions varied from 2 to 7 days (Table 2), while the median number of days to readmission varied substantially by infection type (range, 4 days for bacterial infection [site unspecified] to 24 days for sexually transmitted infections). Among the top five indications for admission for children without complexity, 14.9% to 52.8% of readmissions were for the same cause as the index admission; however, many additional returns were likely related to the index admission (Appendix Table 4). For example, among other return reasons, an additional 992 (61.7%) readmissions following appendicitis hospitalizations were for complications of surgical procedures or medical care, peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, and abdominal pain.

Impact of Achieving Readmission Benchmarks

Among children without complexity, readmission benchmarks (ie, the 10th percentile of readmission rates across hospitals) ranged from 0% to 26.7% (Figure 2). An estimated 54.7% of readmissions (n = 5,507) could potentially be reduced if hospitals achieved infection-specific benchmark readmission rates, which could result in an estimated $44.5 million in savings. Pneumonia, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, and upper respiratory tract infections were among conditions with the greatest potential reductions in readmissions and costs if a 10th percentile benchmark was achieved.

Children With Medical Complexity

Index Admissions and 30-day Readmissions

Among patients with complexity, index admissions occurred most frequently for pneumonia (n = 14,344), bronchiolitis (n = 8,618), and upper respiratory tract infection (n = 6,407) (Figure 1). The median LOS for index admissions ranged from 1 to 9 days (Table 2), with septicemia and CNS infections having the longest median LOS at 9 days.

Thirty-day readmission rates varied substantially by the type of infection at the index admission (range, 0% for sexually transmitted infection to 21.6% for aspiration pneumonia) (Figure 1). The median LOS for 30-day readmissions varied from 2 to 14 days (Table 2), and the median number of days to readmission varied substantially by infection type (range, 6 days for tonsillitis to 23 days for other infection). Among the top five indications for admission for medically complex children, 8% to 40.4% of readmissions were for the same cause as the index admission (Appendix Table 4). As with the children without complexity, additional returns were likely related to the index admission.

Impact of Achieving Readmission Benchmarks

Among children with medical complexity, readmission benchmarks ranged from 0% to 30.3% (Figure 2). An estimated 42.6% of readmissions (n = 3,576) could potentially be reduced if hospitals achieved infection-specific benchmark readmission rates, which could result in an estimated $70.8 million in savings. Pneumonia, bronchiolitis, septicemia, and upper respiratory tract infections were among conditions with the greatest potential reductions in readmissions and costs if the benchmarks were achieved.

DISCUSSION

The current study uncovered new findings regarding unplanned readmissions following index infection hospitalizations for children. In particular, readmission rates and time to readmission varied substantially by infection subtype. The study also identified priority infections and unique considerations for children with CCCs, all of which may help maximize the value of readmission metrics aimed at advancing hospital quality and reducing costs for infection hospitalizations in children. If all hospitals achieved the readmission rates of the best performing hospitals, 42.6% to 54.7% fewer readmissions could be realized with associated cost savings.

Nationally, studies have reported 30-day, all-cause unplanned readmission rates of 6.2% to 10.3%.5,27 In our current study we observed an overall readmission rate of 4.9% across all infectious conditions; however, readmission rates varied substantially by condition, with upper and lower respiratory tract infections, septicemia, and gastroenteritis among infections with the greatest number of potentially avoidable readmissions based on achievement of readmission benchmarks. Currently, pediatric-specific all-cause and lower respiratory tract infection readmission metrics have been developed with the aim of improving quality of care and reducing healthcare expenditures.28 Future readmission studies and metrics may prioritize conditions such as septicemia, gastroenteritis, and other respiratory tract infections. Our current study demonstrated that many readmissions following infection hospitalizations were associated with the same CCS category or within a related CCS category (eg, complications of surgical procedures or medical care, appendicitis, peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, and abdominal pain constituted the top five indications for readmission for appendicitis, whereas respiratory illnesses constituted the top five indications for readmissions for pneumonia). While this current study cannot clarify this relationship further, and the “avoidability” of unplanned readmissions is debated,29-31 our findings suggest that future investigations might focus on identifying whether condition-specific interventions during the index admission could mitigate some readmissions.

While the LOS of the index admission and the readmission were similar for most infection subtypes, we observed substantial variability in the temporal risk for readmission by infection subtype. Our observations complement studies exploring the timing of readmissions for other pediatric conditions.32-34 In particular, our findings further highlight that the composition and interaction of factors influencing infection readmissions may vary by condition. Infections represent a diverse group of conditions, with treatment courses that vary in need for parenteral antibiotics, ability to tailor treatment based on organism and susceptibilities, and length of treatment. While treatment for some infections may be accomplished, or nearly accomplished, prior to discharge, other infections (eg, osteomyelitis) may require prolonged treatment, shifting the burden of management and monitoring to patients and their families, which along with the timeliness and adequacy of outpatient follow-up, may modify an individual’s readmission risk. Consequently, a “one-size fits all” approach to discharge counseling may not be successful across all conditions. Our study lays the groundwork for how these temporal relationships may be used by clinicians to counsel families regarding the likely readmission timeframe, based on infection, and to establish follow-up appointments ahead of the infection-specific “readmission window,” which may allow outpatient providers to intervene when readmission risk is greatest.

Consistent with prior literature, children with medical complexity in our study had increased frequency of 30-day, all-cause unplanned readmissions and LOS, compared with peers who did not have complexity.5 Readmission rates following hospitalizations for aspiration pneumonia were comparable to those reported by Thompson et al in their study examining rates of pneumonia in children with neurologic impairment.35 In our current study, nearly 96% of readmissions following aspiration pneumonia hospitalizations were for children with medical complexity, and more than 58% of these readmissions were for aspiration pneumonia or respiratory illness. Future investigations should seek to explore factors contributing to readmissions in children with medical complexity and to evaluate whether interventions such as postdischarge coaching or discharge bundles could assist with reductions in healthcare resource use.36,37

Despite a lack of clear association between readmissions and quality of care for children,38 readmissions rates continue to be used as a quality measure for hospitalized patients. Within our present study, we found that achieving benchmark readmission rates for infection hospitalizations could lead to substantial reductions in readmissions; however, these reductions were seen across this relatively similar group of infection diagnoses, and hospitals may face greater challenges when attempting to achieve a 10th percentile readmission benchmark across a more expansive set of diagnoses. Despite these challenges, understanding the intricacies of readmissions may lead to improved readmission metrics and the systematic identification of avoidable readmissions, the goal of which is to enhance the quality of healthcare for hospitalized children.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. We defined our readmission benchmark at the 10th percentile using the IE database. Because an estimated 70% of hospitalizations for children occur within general hospitals,39 we believe that our use of the IE database allowed for increased generalizability, though the broadening of our findings to nonacademic hospital settings may be less reliable. While we describe the 10th percentile readmission benchmark here, alternative benchmarks would result in different estimates of avoidable readmissions and associated readmission costs (Appendix Tables 2 and 3). The IE and NRD databases do not distinguish intensive care use. We tried to address this limitation through model adjustments using H-RISK, which is particularly helpful for adjusting for NICU admissions through use of the 27 All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Groups for neonatal conditions. Additionally, the NRD uses state-level data to derive national estimates and is not equipped to measure readmissions to hospitals in a different state, distinguish patient deaths occurring after discharge, or to examine the specific indication for readmission (ie, unable to assess if the readmission is related to a complication of the treatment plan, progression of the illness course, or for an unrelated reason). While sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors may affect readmissions, the NRD does not contain information on patients’ race/ethnicity, family/social attributes, or postdischarge follow-up health services, which are known to influence the need for readmission.

Despite these limitations, this study highlights future areas for research and potential opportunities for reducing readmission following infection hospitalizations. First, identifying hospital- and systems-based factors that contribute to readmission reductions at the best-performing hospitals may identify opportunities for hospitals with the highest readmission rates to achieve the rates of the best-performing hospitals. Second, conditions such as upper and lower respiratory tract infections, along with septicemia and gastroenteritis, may serve as prime targets for future investigation based on the estimated number of avoidable readmissions and potential cost savings associated with these conditions. Finally, future investigations that explore discharge counseling and follow-up tailored to the infection-specific temporal risk and patient complexity may identify opportunities for further readmission reductions.

CONCLUSION

Our study provides a broad look at readmissions following infection hospitalizations and highlights substantial variation in readmissions based on infection type. To improve hospital resource use for infections, future preventive measures could prioritize children with complex chronic conditions and those with specific diagnoses (eg, upper and lower respiratory tract infections).

Disclaimer

This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by, NIH or the US government.

Hospitalizations for infections are common in children, with respiratory illnesses, including pneumonia and bronchiolitis, among the most prevalent indications for hospitalization.1,2 Infections are also among the most frequent indications for all-cause readmissions and for potentially preventable readmissions in children.3-5 Beyond hospital resource use, infection hospitalizations and readmissions represent a considerable cause of life disruption for patients and their families.6,7 While emerging evidence supports shortened durations of parenteral antibiotics before transitioning to oral therapy for some infections (eg, pyelonephritis, osteomyelitis),8-10 other infections may require extended treatment courses for weeks. The risk of adverse outcomes (eg, complications of medical treatment, readmission risk) and burdens placed on patients and their families may therefore differ across infection types and extend well beyond the immediate hospitalization.