User login

Healthcare Encounter and Financial Impact of COVID-19 on Children’s Hospitals

To benefit patients and the public health of their communities, children’s hospitals across the United States prepared for and responded to COVID-19 by conserving personal protective equipment, suspending noncritical in-person healthcare encounters (including outpatient visits and elective surgeries), and implementing socially distanced essential care.1,2 These measures were promptly instituted during a time of both substantial uncertainty about the pandemic’s behavior in children—including its severity and duration—and extreme variation in local and state governments’ responses to the pandemic.

Congruent with other healthcare institutions, children’s hospitals calibrated their clinical operations to the evolving nature of the pandemic, prioritizing the safety of patients and staff while striving to maintain financial viability in the setting of increased costs and decreased revenue. In some cases, children’s hospitals aided adult hospitals and health systems by admitting young and middle-aged adult patients and by centralizing all pediatric patients requiring intensive care within a region. These efforts occurred while many children’s hospitals remained the sole source of specialized pediatric care, including care for rare complex health problems.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there is a critical need to assess how the initial phase of the pandemic affected healthcare encounters and related finances in children’s hospitals. Understanding these trends will position children’s hospitals to project and prepare for subsequent COVID-19 surges, as well as future related public health crises that necessitate widespread social distancing. Therefore, we compared year-over-year trends in healthcare encounters and hospital charges across US children’s hospitals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the beginning of COVID-19 in the United States, which was defined as February through June 2020.

METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of 26 children’s hospitals (22 freestanding, 4 nonfreestanding) from all US regions (12 South, 7 Midwest, 5 West, 2 Northeast) contributing encounter and financial data to the PROSPECT database (Children’s Hospital Association, Lenexa, Kansas) from February 1 to June 30 in both 2019 (before COVID-19) and 2020 (during COVID-19). In response to COVID-19, hospitals participating in PROSPECT increased the efficiency of data centralization and reporting in 2020 during the period February 1 to June 30 to expedite analysis and dissemination of findings.

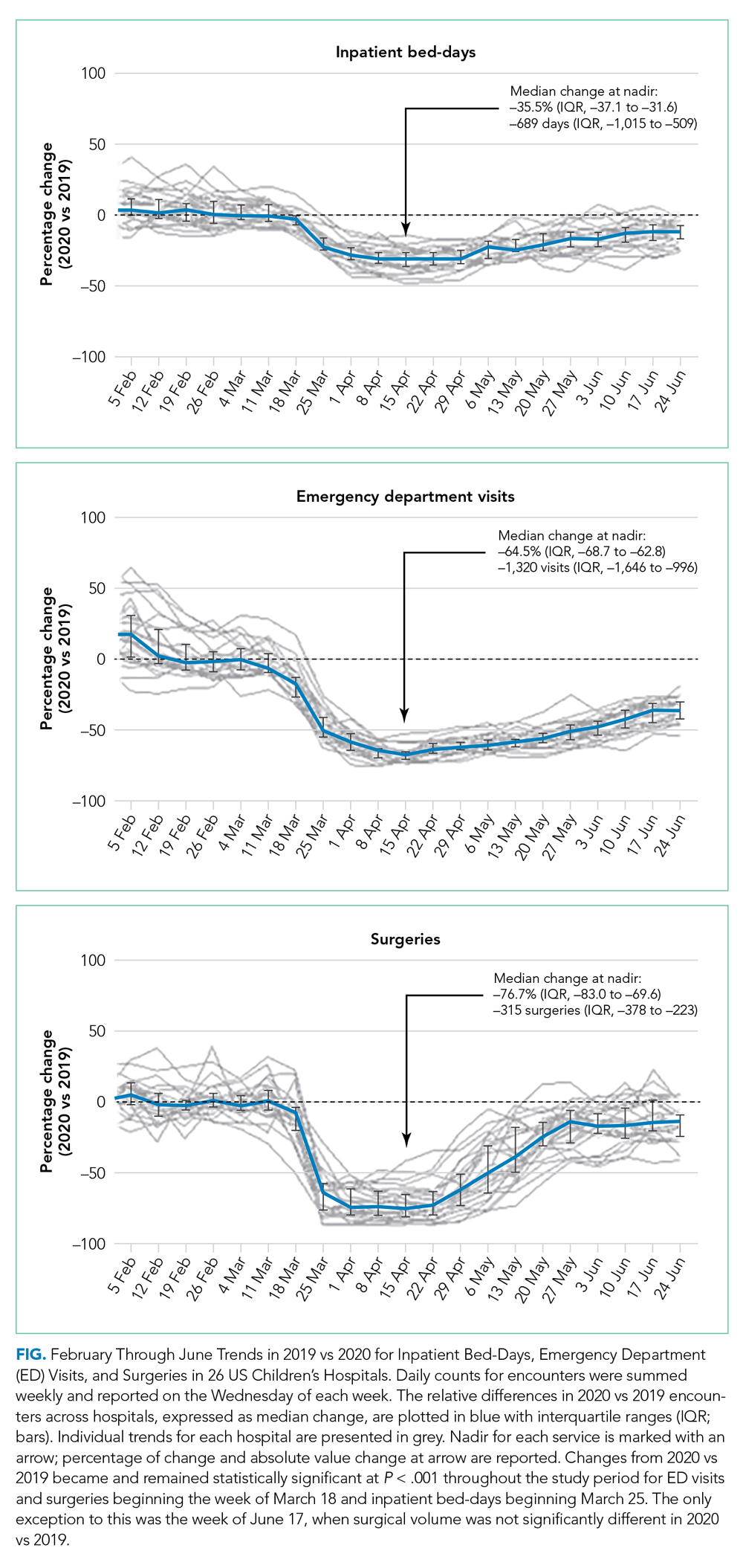

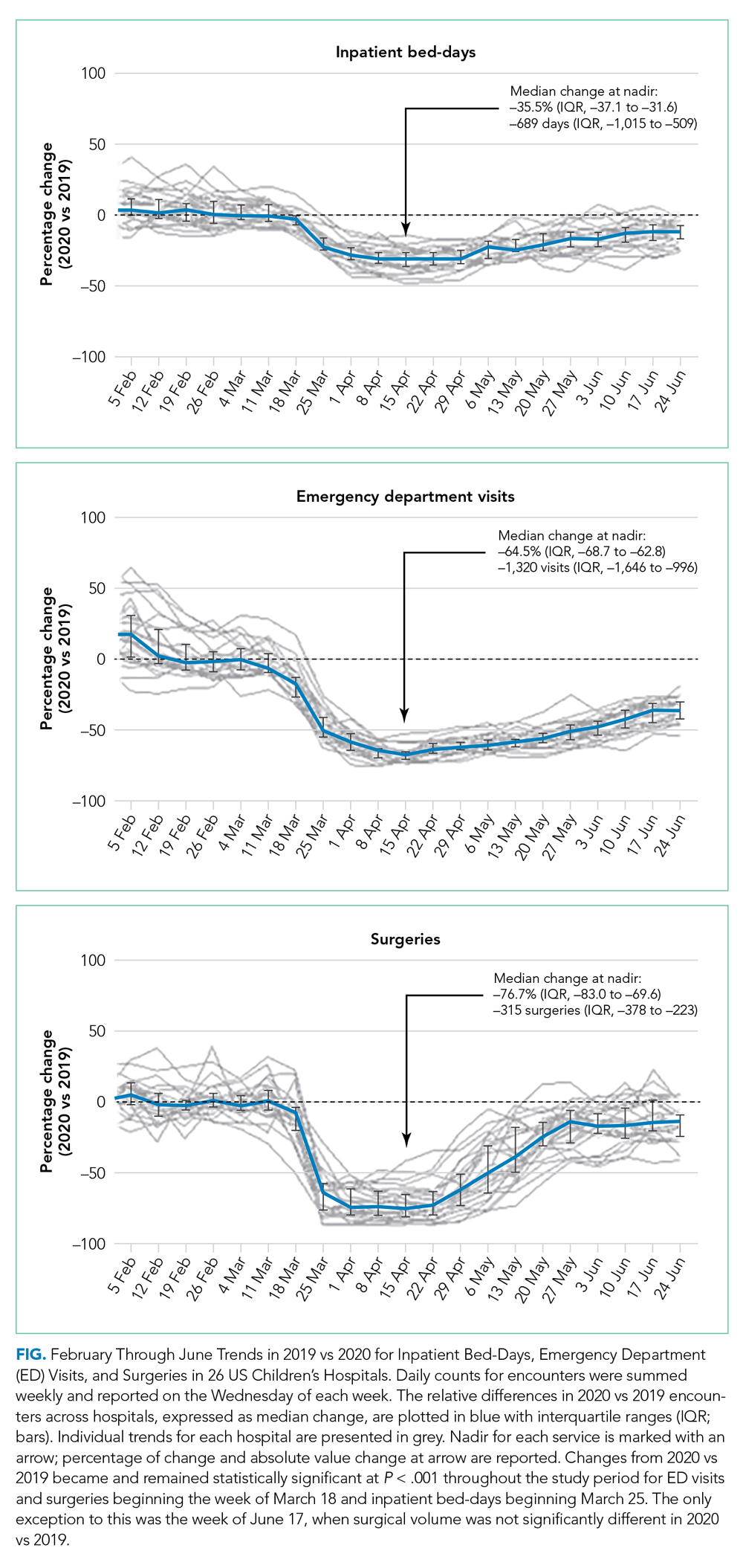

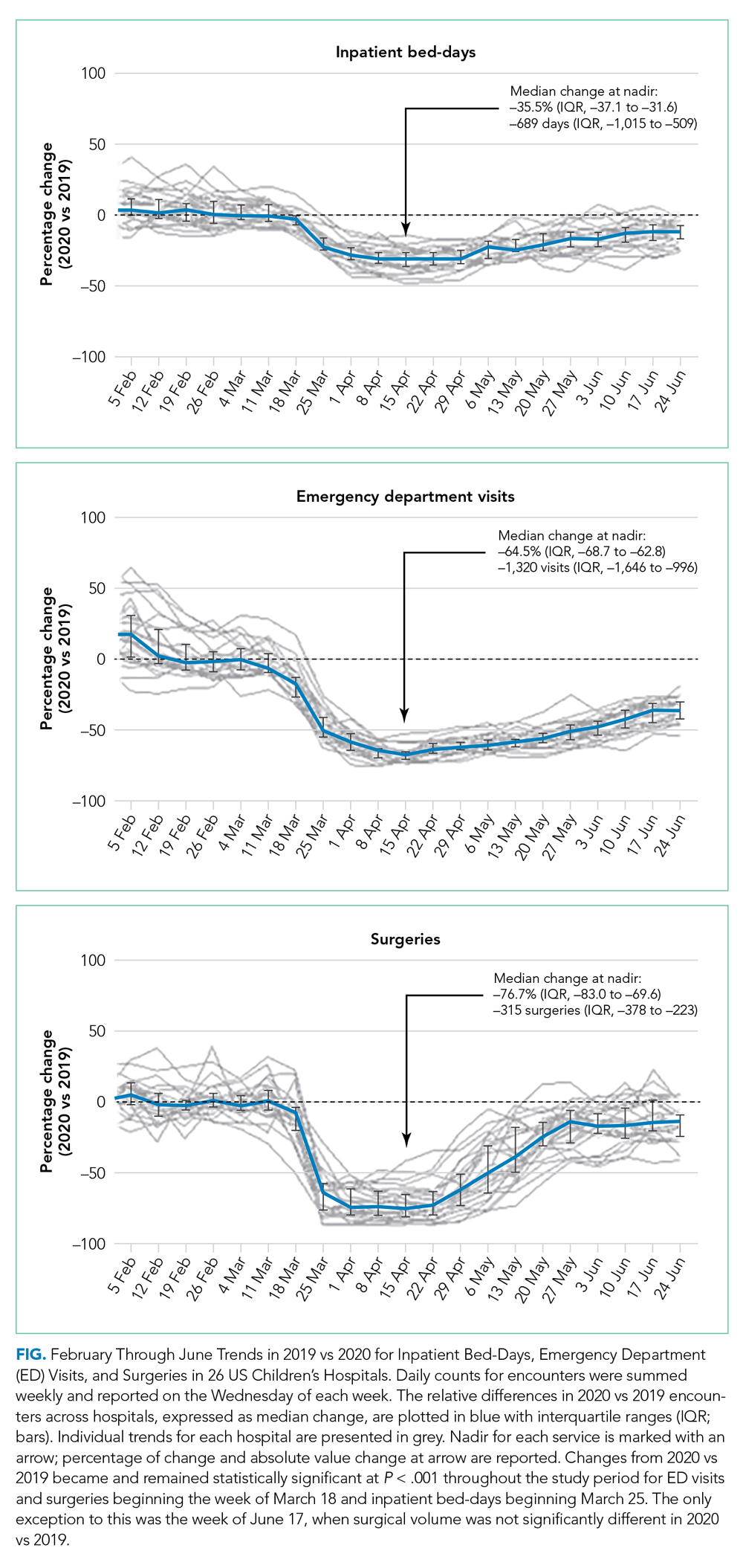

The main outcome measures were the percentage of change in weekly encounters (inpatient bed-days, emergency department [ED] visits, and surgeries) and inflation-adjusted charges (categorized as inpatient care and outpatient care, such as ambulatory surgery, clinics, and ED visits) before vs during COVID-19.

RESULTS

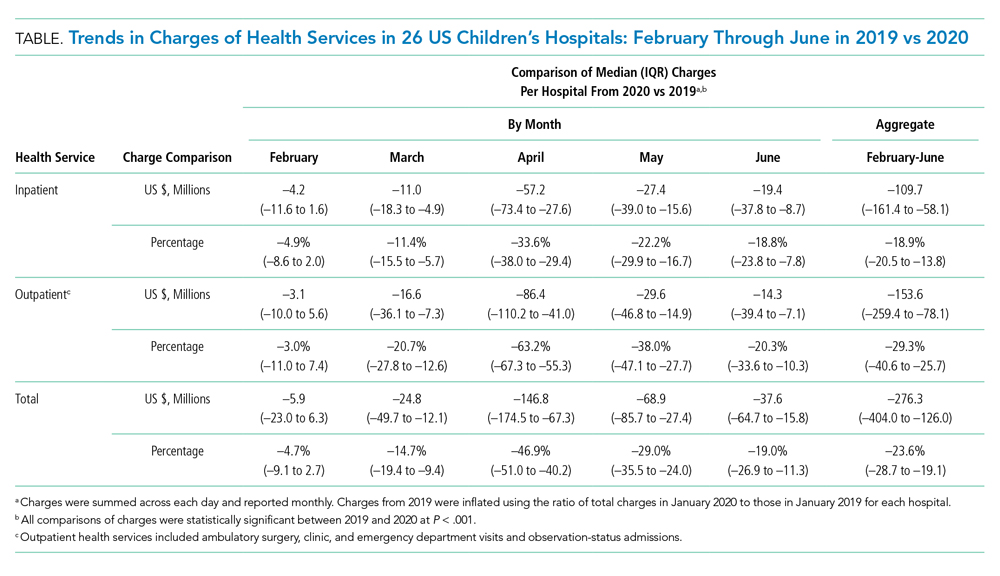

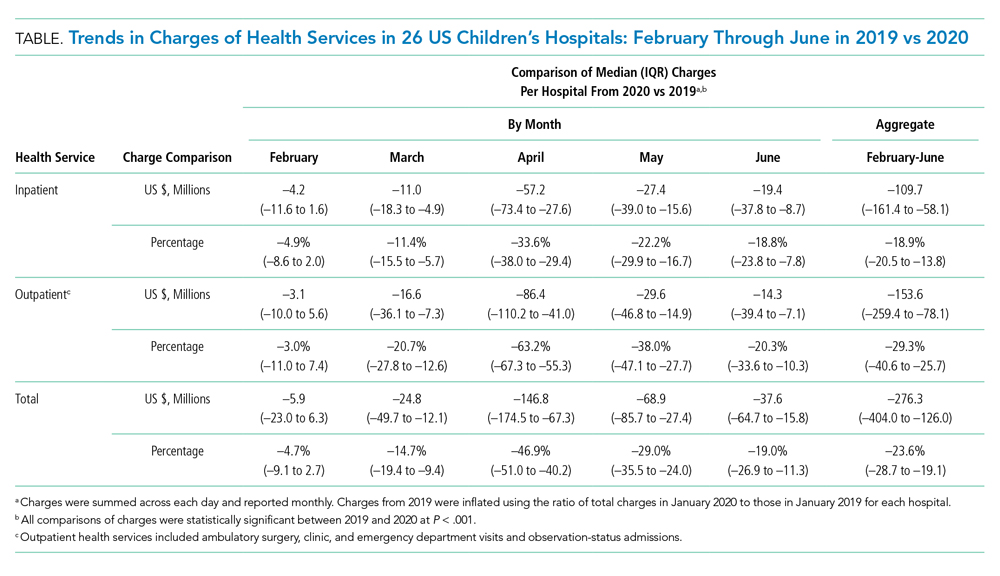

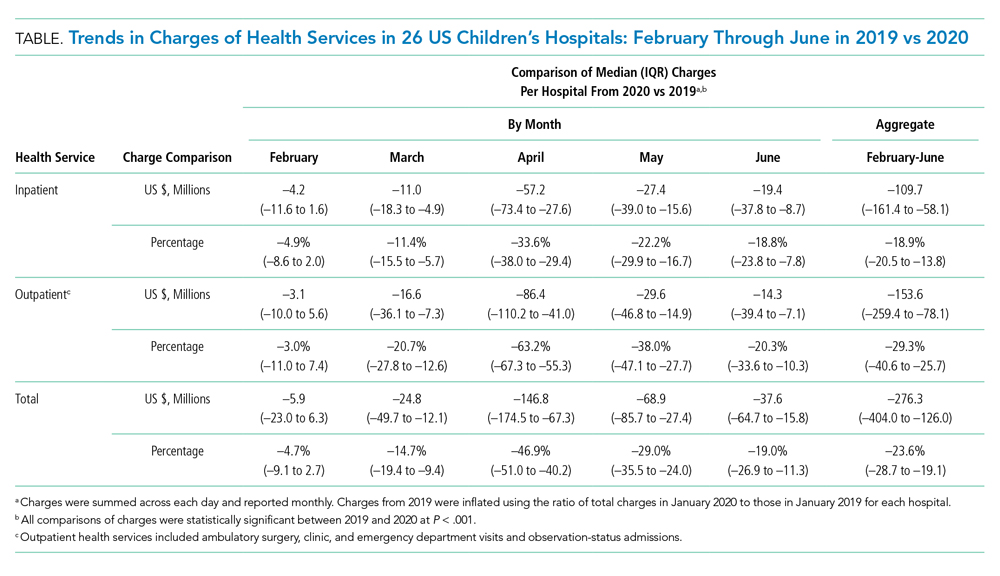

Charges that accrued from February 1 to June 30 were lower in 2020 by a median 23.6% (IQR, –28.7% to –19.1%) per children’s hospital than they were in 2019, corresponding to a median decrease of $276.3 million (IQR, $404.0-$126.0 million) in charges per hospital (Table). Forty percent of this decrease was attributable to decreased charges resulting from fewer inpatient healthcare encounters.

DISCUSSION

These findings beg the question of how well children’s hospitals are positioned to weather a recurrent surge in COVID-19. Because the severity of illness of COVID-19 has been lower to date in the pediatric vs adult populations, an increase in COVID-19-related visits to EDs and admissions to offset the decreased resource use of other pediatric healthcare problems is not anticipated. Existing hospital financial reserves as well as federal aid from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act that helped mitigate the initial encounter and financial losses during the beginning of COVID-19 may not be readily available over time.4,5 Certainly, the findings from the current study support continued lobbying for additional state and federal funds allocated through future relief packages to children’s hospitals.

Additional approaches to financial solvency in children’s hospitals during the sustained COVID-19 pandemic include addressing surgical backlogs and sharing best practices for safe and sustained reopening of clinical operations and financial practices across institutions. Although the PROSPECT database does not contain information on the types of surgeries present within this backlog, our experiences suggest that both same-day and inpatient elective surgeries have been affected, especially lengthy procedures (eg, spinal fusion for neuromuscular scoliosis). Spread and scale of feasible and efficient solutions to reengineer and expand patient capacities and throughput for operating rooms, postanesthesia recovery areas, and intensive care and floor units are needed. Enhanced analytics that accurately predict postoperative length of hospital stay, coupled with early recovery after surgery clinical protocols, could help optimize hospital bed management. Effective ways to convert hospital rooms from single to double occupancy, to manage family visitation, and to proactively test asymptomatic patients, family, and hospital staff will mitigate continued COVID-19 penetration through children’s hospitals.

One important limitation of the current study is the measurement of hospitals’ charges. The charge data were not positioned to comprehensively measure each hospital’s financial state during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the decrease in hospital charges reported by the children’s hospitals in the current study is comparable with the financial losses reported for many adult hospitals during the pandemic.6,7

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals’ ability to serve the nation’s pediatric patients depends on the success of the hospitals’ plans to manage current and future COVID-19 surges and to reopen and recover from the surges that have passed. Additional investigation is needed to identify best operational and financial practices among children’s hospitals that have enabled them to endure the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. COVID-19: ways to prepare your children’s hospital now. Children’s Hospital Association. March 12, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Newsroom/Childrens-Hospitals-Today/Articles/2020/03/COVID-19-11-Ways-to-Prepare-Your-Hospital-Now

2. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

3. Oseran AS, Nash D, Kim C, et al. Changes in hospital admissions for urgent conditions during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(8):327-328. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.43837

4. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the CARES Act. 15 USC Chapter 116 (2020). Pub L No. 116-36, 134 Stat 281. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748

5. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Provider Relief Fund: general information. US Department of Health & Human Services. June 25, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/cares-act-provider-relief-fund/general-information/index.html

6. Hospitals and health systems face unprecedented financial pressures due to COVID-19. American Hospital Association. May 2020. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/aha-covid19-financial-impact-0520-FINAL.pdf

7. Birkmeyer J, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

To benefit patients and the public health of their communities, children’s hospitals across the United States prepared for and responded to COVID-19 by conserving personal protective equipment, suspending noncritical in-person healthcare encounters (including outpatient visits and elective surgeries), and implementing socially distanced essential care.1,2 These measures were promptly instituted during a time of both substantial uncertainty about the pandemic’s behavior in children—including its severity and duration—and extreme variation in local and state governments’ responses to the pandemic.

Congruent with other healthcare institutions, children’s hospitals calibrated their clinical operations to the evolving nature of the pandemic, prioritizing the safety of patients and staff while striving to maintain financial viability in the setting of increased costs and decreased revenue. In some cases, children’s hospitals aided adult hospitals and health systems by admitting young and middle-aged adult patients and by centralizing all pediatric patients requiring intensive care within a region. These efforts occurred while many children’s hospitals remained the sole source of specialized pediatric care, including care for rare complex health problems.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there is a critical need to assess how the initial phase of the pandemic affected healthcare encounters and related finances in children’s hospitals. Understanding these trends will position children’s hospitals to project and prepare for subsequent COVID-19 surges, as well as future related public health crises that necessitate widespread social distancing. Therefore, we compared year-over-year trends in healthcare encounters and hospital charges across US children’s hospitals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the beginning of COVID-19 in the United States, which was defined as February through June 2020.

METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of 26 children’s hospitals (22 freestanding, 4 nonfreestanding) from all US regions (12 South, 7 Midwest, 5 West, 2 Northeast) contributing encounter and financial data to the PROSPECT database (Children’s Hospital Association, Lenexa, Kansas) from February 1 to June 30 in both 2019 (before COVID-19) and 2020 (during COVID-19). In response to COVID-19, hospitals participating in PROSPECT increased the efficiency of data centralization and reporting in 2020 during the period February 1 to June 30 to expedite analysis and dissemination of findings.

The main outcome measures were the percentage of change in weekly encounters (inpatient bed-days, emergency department [ED] visits, and surgeries) and inflation-adjusted charges (categorized as inpatient care and outpatient care, such as ambulatory surgery, clinics, and ED visits) before vs during COVID-19.

RESULTS

Charges that accrued from February 1 to June 30 were lower in 2020 by a median 23.6% (IQR, –28.7% to –19.1%) per children’s hospital than they were in 2019, corresponding to a median decrease of $276.3 million (IQR, $404.0-$126.0 million) in charges per hospital (Table). Forty percent of this decrease was attributable to decreased charges resulting from fewer inpatient healthcare encounters.

DISCUSSION

These findings beg the question of how well children’s hospitals are positioned to weather a recurrent surge in COVID-19. Because the severity of illness of COVID-19 has been lower to date in the pediatric vs adult populations, an increase in COVID-19-related visits to EDs and admissions to offset the decreased resource use of other pediatric healthcare problems is not anticipated. Existing hospital financial reserves as well as federal aid from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act that helped mitigate the initial encounter and financial losses during the beginning of COVID-19 may not be readily available over time.4,5 Certainly, the findings from the current study support continued lobbying for additional state and federal funds allocated through future relief packages to children’s hospitals.

Additional approaches to financial solvency in children’s hospitals during the sustained COVID-19 pandemic include addressing surgical backlogs and sharing best practices for safe and sustained reopening of clinical operations and financial practices across institutions. Although the PROSPECT database does not contain information on the types of surgeries present within this backlog, our experiences suggest that both same-day and inpatient elective surgeries have been affected, especially lengthy procedures (eg, spinal fusion for neuromuscular scoliosis). Spread and scale of feasible and efficient solutions to reengineer and expand patient capacities and throughput for operating rooms, postanesthesia recovery areas, and intensive care and floor units are needed. Enhanced analytics that accurately predict postoperative length of hospital stay, coupled with early recovery after surgery clinical protocols, could help optimize hospital bed management. Effective ways to convert hospital rooms from single to double occupancy, to manage family visitation, and to proactively test asymptomatic patients, family, and hospital staff will mitigate continued COVID-19 penetration through children’s hospitals.

One important limitation of the current study is the measurement of hospitals’ charges. The charge data were not positioned to comprehensively measure each hospital’s financial state during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the decrease in hospital charges reported by the children’s hospitals in the current study is comparable with the financial losses reported for many adult hospitals during the pandemic.6,7

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals’ ability to serve the nation’s pediatric patients depends on the success of the hospitals’ plans to manage current and future COVID-19 surges and to reopen and recover from the surges that have passed. Additional investigation is needed to identify best operational and financial practices among children’s hospitals that have enabled them to endure the COVID-19 pandemic.

To benefit patients and the public health of their communities, children’s hospitals across the United States prepared for and responded to COVID-19 by conserving personal protective equipment, suspending noncritical in-person healthcare encounters (including outpatient visits and elective surgeries), and implementing socially distanced essential care.1,2 These measures were promptly instituted during a time of both substantial uncertainty about the pandemic’s behavior in children—including its severity and duration—and extreme variation in local and state governments’ responses to the pandemic.

Congruent with other healthcare institutions, children’s hospitals calibrated their clinical operations to the evolving nature of the pandemic, prioritizing the safety of patients and staff while striving to maintain financial viability in the setting of increased costs and decreased revenue. In some cases, children’s hospitals aided adult hospitals and health systems by admitting young and middle-aged adult patients and by centralizing all pediatric patients requiring intensive care within a region. These efforts occurred while many children’s hospitals remained the sole source of specialized pediatric care, including care for rare complex health problems.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there is a critical need to assess how the initial phase of the pandemic affected healthcare encounters and related finances in children’s hospitals. Understanding these trends will position children’s hospitals to project and prepare for subsequent COVID-19 surges, as well as future related public health crises that necessitate widespread social distancing. Therefore, we compared year-over-year trends in healthcare encounters and hospital charges across US children’s hospitals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the beginning of COVID-19 in the United States, which was defined as February through June 2020.

METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of 26 children’s hospitals (22 freestanding, 4 nonfreestanding) from all US regions (12 South, 7 Midwest, 5 West, 2 Northeast) contributing encounter and financial data to the PROSPECT database (Children’s Hospital Association, Lenexa, Kansas) from February 1 to June 30 in both 2019 (before COVID-19) and 2020 (during COVID-19). In response to COVID-19, hospitals participating in PROSPECT increased the efficiency of data centralization and reporting in 2020 during the period February 1 to June 30 to expedite analysis and dissemination of findings.

The main outcome measures were the percentage of change in weekly encounters (inpatient bed-days, emergency department [ED] visits, and surgeries) and inflation-adjusted charges (categorized as inpatient care and outpatient care, such as ambulatory surgery, clinics, and ED visits) before vs during COVID-19.

RESULTS

Charges that accrued from February 1 to June 30 were lower in 2020 by a median 23.6% (IQR, –28.7% to –19.1%) per children’s hospital than they were in 2019, corresponding to a median decrease of $276.3 million (IQR, $404.0-$126.0 million) in charges per hospital (Table). Forty percent of this decrease was attributable to decreased charges resulting from fewer inpatient healthcare encounters.

DISCUSSION

These findings beg the question of how well children’s hospitals are positioned to weather a recurrent surge in COVID-19. Because the severity of illness of COVID-19 has been lower to date in the pediatric vs adult populations, an increase in COVID-19-related visits to EDs and admissions to offset the decreased resource use of other pediatric healthcare problems is not anticipated. Existing hospital financial reserves as well as federal aid from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act that helped mitigate the initial encounter and financial losses during the beginning of COVID-19 may not be readily available over time.4,5 Certainly, the findings from the current study support continued lobbying for additional state and federal funds allocated through future relief packages to children’s hospitals.

Additional approaches to financial solvency in children’s hospitals during the sustained COVID-19 pandemic include addressing surgical backlogs and sharing best practices for safe and sustained reopening of clinical operations and financial practices across institutions. Although the PROSPECT database does not contain information on the types of surgeries present within this backlog, our experiences suggest that both same-day and inpatient elective surgeries have been affected, especially lengthy procedures (eg, spinal fusion for neuromuscular scoliosis). Spread and scale of feasible and efficient solutions to reengineer and expand patient capacities and throughput for operating rooms, postanesthesia recovery areas, and intensive care and floor units are needed. Enhanced analytics that accurately predict postoperative length of hospital stay, coupled with early recovery after surgery clinical protocols, could help optimize hospital bed management. Effective ways to convert hospital rooms from single to double occupancy, to manage family visitation, and to proactively test asymptomatic patients, family, and hospital staff will mitigate continued COVID-19 penetration through children’s hospitals.

One important limitation of the current study is the measurement of hospitals’ charges. The charge data were not positioned to comprehensively measure each hospital’s financial state during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the decrease in hospital charges reported by the children’s hospitals in the current study is comparable with the financial losses reported for many adult hospitals during the pandemic.6,7

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals’ ability to serve the nation’s pediatric patients depends on the success of the hospitals’ plans to manage current and future COVID-19 surges and to reopen and recover from the surges that have passed. Additional investigation is needed to identify best operational and financial practices among children’s hospitals that have enabled them to endure the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. COVID-19: ways to prepare your children’s hospital now. Children’s Hospital Association. March 12, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Newsroom/Childrens-Hospitals-Today/Articles/2020/03/COVID-19-11-Ways-to-Prepare-Your-Hospital-Now

2. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

3. Oseran AS, Nash D, Kim C, et al. Changes in hospital admissions for urgent conditions during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(8):327-328. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.43837

4. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the CARES Act. 15 USC Chapter 116 (2020). Pub L No. 116-36, 134 Stat 281. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748

5. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Provider Relief Fund: general information. US Department of Health & Human Services. June 25, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/cares-act-provider-relief-fund/general-information/index.html

6. Hospitals and health systems face unprecedented financial pressures due to COVID-19. American Hospital Association. May 2020. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/aha-covid19-financial-impact-0520-FINAL.pdf

7. Birkmeyer J, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

1. COVID-19: ways to prepare your children’s hospital now. Children’s Hospital Association. March 12, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Newsroom/Childrens-Hospitals-Today/Articles/2020/03/COVID-19-11-Ways-to-Prepare-Your-Hospital-Now

2. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

3. Oseran AS, Nash D, Kim C, et al. Changes in hospital admissions for urgent conditions during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(8):327-328. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.43837

4. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the CARES Act. 15 USC Chapter 116 (2020). Pub L No. 116-36, 134 Stat 281. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748

5. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Provider Relief Fund: general information. US Department of Health & Human Services. June 25, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/cares-act-provider-relief-fund/general-information/index.html

6. Hospitals and health systems face unprecedented financial pressures due to COVID-19. American Hospital Association. May 2020. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/aha-covid19-financial-impact-0520-FINAL.pdf

7. Birkmeyer J, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Performance of Pediatric Readmission Measures

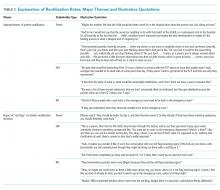

Readmission rates are frequently used as a hospital quality metric, with use including payment incentive at the hospital level,1 specific condition quality measurement,2 balancing measures for quality improvement projects,3-5 transition success,6,7 and use in public hospital rankings.8 Currently, four methods are commonly used to evaluate pediatric readmissions, each with strengths and limitations, including the following (Appendix Table 1):

1. All-cause readmissions: A measure of any readmission within a given time period regardless of the reason for readmission.9

2. Unplanned readmission/time flag: A measure intended to identify unplanned readmissions. This measure relies on time designations within the electronic health record. The time between hospital registration and admission is calculated, and if the readmission is registered more than 24 hours prior to admission, the readmission is considered planned.10 Hereafter, this measure will be referred to as the time flag measure.

3. Pediatric all-condition readmission (PACR): A measure intended to identify unplanned readmission through the exclusion of certain procedures and diagnoses.11

4. Potentially preventable readmission (PPR): A method to identify preventable readmissions based on a proprietary algorithm developed by

While all four of these measures are used to assess quality, there is little known about these measures’ ability to exclude planned readmissions and identify only preventable pediatric readmission, which conceptually is most relevant to the quality of care. However, many of these measures were not intended to capture preventability, but instead capture the related issue of whether the readmission was planned. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the four readmission measures as they relate to both preventability and unplanned status as determined through medical record review with multidisciplinary care provider input.

METHODS

As part of a hospital-wide readmission reduction quality improvement collaborative at a free-standing tertiary care children’s hospital, clinicians from hospital medicine, cardiology, neonatology, and neurology teams reviewed 30-day readmissions using a standardized abstraction tool. All readmission events (observation or inpatient encounter) after any discharge (observation or inpatient encounter) from eligible units were reviewed; therefore, each hospitalization was a potential index hospitalization. We classified the preventability of each readmission with use of a previously described Likert scale with high interrater reliability.14 For these analyses, readmissions were considered preventable if the reviewing team rated them as either “more likely preventable” or “preventable in most circumstances.” Each readmission was also evaluated as planned or unplanned. Methods for readmission review and classification are in the Appendix.

We included all readmissions between July 2014 and June 2016. We compared the medical record review classifications with the assessments from each of the four measures of pediatric readmission. We calculated sensitivity and specificity for both outcomes (planned/unplanned and preventable/not preventable) for all four measures. For standardization of discussion, we categorized description of measure performance as “very poor” as less than 50%, “poor” between 50%-75%, “fair” as 75%-85%, “good” as 85%-90%, “very good” as 90%-95% and excellent as greater than 95%. We also calculated positive and negative predictive value (PPV and NPV) over plausible ranges of prevalence using the sensitivity and specificity of each comparison (Appendix).

Of note, certain exclusions are outlined by the PACR and PPR algorithms. The PACR evaluates only readmission events that occur in children younger than 18 years. The PPR algorithm does not assign preventability if either the index or readmission event is classified as an observation stay or if it is part of a larger chain of readmissions.

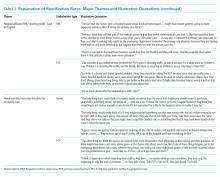

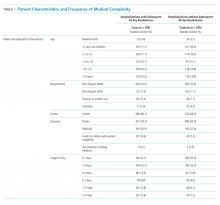

RESULTS

Among 30-day readmissions considered, 1,643 were eligible for medical record review; 1,125 reviews were completed by the clinical teams (68.5%). The median time to readmission was 7 days (interquartile range [IQR], 4-18). Most children were non-Hispanic White (71%) or Black (20%). The median age at hospitalization was 2.3 years (IQR 0.4-12.1). Most children had Medicaid (56%) or private (41%) insurance. Most of the reviews were performed in cardiology (43%) and hospital medicine (37%) with patients in neurology (13%) and neonatology (7%) constituting the remaining reviews. Uncontrolled advancement of chronic disease was the most common readmission category on medical record review (25.1%), followed by unrelated readmission (20.7%), scheduled readmission (20.4%), and progression of acute disease (16.6%) (Appendix Table 2).

Assessment of Preventable and Unplanned Readmissions

On multidisciplinary medical record review, most readmissions were classified as not preventable (84.5%). Specifically, 64% were not preventable and unplanned; 20% were deemed not preventable and planned. Only 15% were classified as unplanned and preventable and 1% as planned and preventable (Appendix Figure: Population A/B).

Matching Chart Review to the Four Algorithms

All 1,125 readmissions were assessed by the all-cause and time flag readmission measures (Appendix Figure: Population A/B). After applying algorithm exclusions (details in Appendix), only 804 of the 1,125 (71.5%) reviewed readmissions matched for PACR readmission comparison (Appendix Figure: Population C); 487 of the 1,125 (43.3%) of the reviewed readmissions matched for PPR comparison (Appendix Figure: Population D).

All-Cause

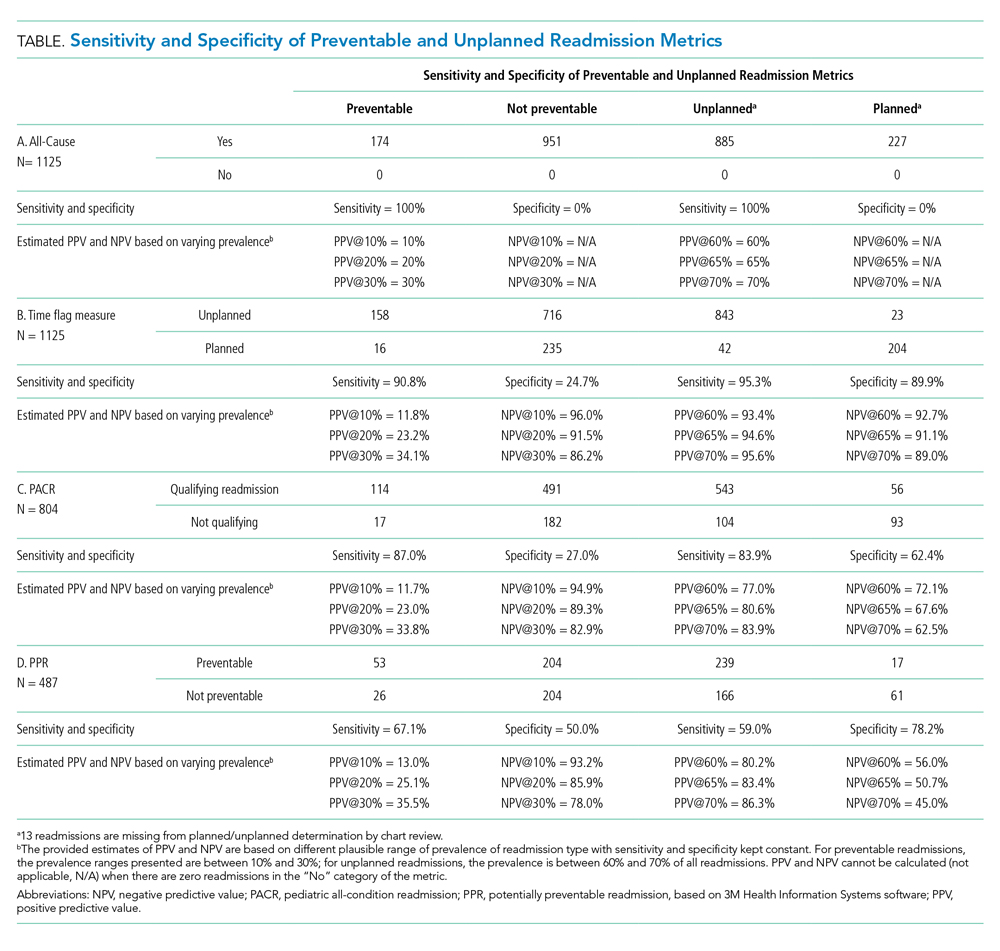

Because all-cause determines only if a readmission occurs, the measure is by definition 100% sensitive and 0% specific in both assessment of preventability and unplanned readmission (Table: Section A).

Time Flag

The time flag measure identified 80% (866/1,112) of the readmissions as unplanned. This measure had very good sensitivity but very poor specificity in identifying preventable readmissions, which corresponded to very poor PPV and good to excellent NPV. In terms of identifying unplanned readmissions, the time flag measure had excellent sensitivity and very good specificity, which corresponded to very good to excellent PPV and good to very good NPV (Table: Section B).

PACR

The PACR algorithm identified 75% (599/796) of readmissions as unplanned. The PACR has good sensitivity but very poor specificity in identifying preventable readmissions, which corresponded to very poor PPV and fair to very good NPV. In terms of identifying unplanned readmissions, the PACR had fair sensitivity but poor specificity, which corresponded to fair PPV and poor NPV (Table: Section C).

PPR

The PPR algorithm identified 53% (257/487) of admissions as potentially preventable. The PPR algorithm had poor sensitivity and specificity in identifying preventable readmissions, which corresponded to very poor PPV and fair to very good NPV. In terms of identifying unplanned readmissions, the PPR algorithm had poor sensitivity and fair specificity in identifying unplanned readmissions, which corresponded to fair to good PPV and very poor to poor NPV (Table: Section D).

Evaluation of Excluded Readmission Events

Because both the PACR and PPR had large numbers of algorithm exclusions, we describe the preventability and unplanned assessment of the excluded readmission events. Both algorithms excluded preventable events. Of the 321 readmissions excluded by the PACR algorithm, 13.4% were classified as preventable by chart review. Likewise, 14.9% of 638 readmissions excluded by PPR were classified as preventable by chart review.

DISCUSSION

The ability to accurately capture preventable pediatric readmission is a goal for hospital quality experts and health policymakers alike. Of the four commonly used readmission measures to assess readmission, only PPR is designed to focus on preventability. Unfortunately, none of these four measures is adequately sensitive or specific to identify preventable readmissions; all measures had very poor PPV for preventability. Of the four measures, the time flag measure had the best sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for identifying unplanned readmissions.

The overall percentage of unplanned readmissions identified by both the time flag and by PACR measures match the overall percentage of unplanned readmissions identified in chart review: The time flag measure identified 80% of admissions as unplanned versus 79% identified by chart review (Appendix Figure: Population A/B); PACR classified 75% as unplanned versus 81% identified by chart review for PACR-eligible readmissions (Appendix Figure: Population C). In contrast, the PPR algorithm classified many more readmissions as potentially preventable (53%) than were identified by chart review at only 16% (Appendix Figure: Population D). The PACR and PPR algorithms also exclude a significant number of readmissions that are unplanned and a smaller, but not trivial, number of readmissions that are preventable; these exclusions limit their accuracy.

The ability to apply these four measures in real time during a hospitalization varies by metric. Two of the measures, the all-cause and time flag, can be applied during a readmission event, which is appealing for quality improvement initiatives. These measures allow for notification of providers that a current hospitalization is a readmission event, which allows providers the opportunity to learn from these events as they occur (Appendix Table 1). While “unplanned” is not the same as “potentially preventable,” almost all potentially preventable readmissions are unplanned; therefore, accurately identifying unplanned readmissions is more beneficial than all-cause. Additionally, a low all-cause readmission rate can be indicative of poor access to scheduled procedures. Nevertheless, all-cause readmission is sometimes used to measure quality.1,8 While the time flag measure may be more useful for quality improvement initiatives and hospital providers, it relies on hospital registration time, which is not widely available in administrative data sources and, therefore, has limited usefulness to policymakers.

Both PACR and PPR require administrative claims analysis, which is appealing from a policy standpoint. However, the reliance on claims data means the inclusion/exclusion of events can occur only retrospectively, which limits the usefulness of these measures in learning and intervening in real time. When the two measures are compared, PACR offers better sensitivity and PPR offers better specificity with regard to identifying unplanned readmission. The PPR software overcalls preventable readmissions, identifying more readmissions as preventable than there actually are. Nevertheless, Medicaid in several states uses PPR for payment incentive.1,15-17 Given the poor performance of PPR in assessing both preventable and unplanned pediatric readmission, the use of this measure as a quality metric should be limited.

This study should be considered in the context of several limitations. Because the assessment of preventability was determined as part of a learning quality improvement collaborative and not as a planned research endeavor, not all readmission reviews were completed nor were other existent tools18 that allow for preventability assessment via more structured medical record review used. Second, we reviewed cases only from certain clinical services, which would limit generalizability of these findings to all pediatric admissions. However, given the low sensitivity and specificity of some of the metrics, we would not anticipate that the addition of other types of admissions would improve the sensitivity and specificity enough to ensure reliability. Third, while we relied on an established method to determine preventability, prior work has demonstrated that additional information gathered from families may change preventability.19 Finally, due to the exclusions required by the PPR and PACR algorithms, not all readmission events were reviewed. However, these exclusions reflect the actual specifications of use for both measures.

CONCLUSION

The PPR software has poor fidelity in identifying preventable and unplanned pediatric readmission; this finding has broad policy implications given how widely it is used by state Medicaid offices to assess financial penalties. Among the four pediatric readmission measures used, the time flag metric best identifies unplanned readmissions.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding

Dr Auger’s research is supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS204735-01A1). The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number 5UL1TR001425-04. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

1. State Medicaid Payment Policies for Inpatient Hospital Services. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission; December 2018. Accessed June 1, 2019. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/macpac-inpatient-hospital-payment-landscapes/

2. Mangione-Smith R, Zhou C, Williams DJ, et al. Pediatric Respiratory Illness Measurement System (PRIMES) scores and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):e20190242. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0242

3. Biondi EA, McCulloh R, Staggs VS, et al. Reducing Variability in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE): a national quality initiative. Pediatrics. 2019;144(3):e20182201. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2201

4. Statile AM, Schondelmeyer AC, Thomson JE, et al. Improving discharge efficiency in medically complex pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20153832. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3832

5. White CM, Statile AM, White DL, et al. Using quality improvement to optimise paediatric discharge efficiency. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):428-436. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002556

6. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al; H20 Trial Study Group. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: the Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3919

7. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482

8. Olmsted MG, Powell R, Murphy J, Bell Denise, Stanley M, Sanchz R. Methodology: U.S. News & World Report Best Children’s Hospitals 2019-20. U.S. News & World Report; June 17, 2019. Accessed June 16, 2020. https://www.usnews.com/static/documents/health/best-hospitals/BCH_Methodology_2019-20.pdf

9. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3527

10. Auger KA, Mueller EL, Weinberg SH, et al. A validated method for identifying unplanned pediatric readmission. J Pediatr. 2016;170:105-12.e102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.051

11. Readmissions-Content. Boston Children’s Hospital. Accessed April 8, 2019. http://www.childrenshospital.org/research-and-innovation/research/centers/center-of-excellence-for-pediatric-quality-measurement-cepqm/cepqm-measures/pediatric-readmissions/content

12. Gay JC, Agrawal R, Auger KA, et al. Rates and impact of potentially preventable readmissions at children’s hospitals. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):613-9.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.052

13. Auger KA, Teufel RJ, Harris JM, et al. Children’s hospital characteristics and readmission metrics. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20161720. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1720

14. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of early readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0820

15. Potentially Preventable Events. Texas Health and Human Services. Accessed May 19, 2019. https://hhs.texas.gov/about-hhs/process-improvement/medicaid-chip-quality-efficiency-improvement/potentially-preventable-events

16. Potentially Preventable Readmissions. New York State Department of Health. Accessed May 28, 2019. https://regs.health.ny.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/recently_adopted_regulations/2011-02-23_potentially_preventable_readmissions.pdf

17. Potentially Preventable Readmissions Policy. Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. Accessed May 28, 2019. https://www.illinois.gov/hfs/SiteCollectionDocuments/PPR_Overview.pdf

18. Jonas JA, Devon EP, Ronan JC, et al. Determining preventability of pediatric readmissions using fault tree analysis. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):329-335. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2555

19. Toomey SL, Peltz A, Loren S, et al. Potentially preventable 30-day hospital readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20154182. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4182

Readmission rates are frequently used as a hospital quality metric, with use including payment incentive at the hospital level,1 specific condition quality measurement,2 balancing measures for quality improvement projects,3-5 transition success,6,7 and use in public hospital rankings.8 Currently, four methods are commonly used to evaluate pediatric readmissions, each with strengths and limitations, including the following (Appendix Table 1):

1. All-cause readmissions: A measure of any readmission within a given time period regardless of the reason for readmission.9

2. Unplanned readmission/time flag: A measure intended to identify unplanned readmissions. This measure relies on time designations within the electronic health record. The time between hospital registration and admission is calculated, and if the readmission is registered more than 24 hours prior to admission, the readmission is considered planned.10 Hereafter, this measure will be referred to as the time flag measure.

3. Pediatric all-condition readmission (PACR): A measure intended to identify unplanned readmission through the exclusion of certain procedures and diagnoses.11

4. Potentially preventable readmission (PPR): A method to identify preventable readmissions based on a proprietary algorithm developed by

While all four of these measures are used to assess quality, there is little known about these measures’ ability to exclude planned readmissions and identify only preventable pediatric readmission, which conceptually is most relevant to the quality of care. However, many of these measures were not intended to capture preventability, but instead capture the related issue of whether the readmission was planned. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the four readmission measures as they relate to both preventability and unplanned status as determined through medical record review with multidisciplinary care provider input.

METHODS

As part of a hospital-wide readmission reduction quality improvement collaborative at a free-standing tertiary care children’s hospital, clinicians from hospital medicine, cardiology, neonatology, and neurology teams reviewed 30-day readmissions using a standardized abstraction tool. All readmission events (observation or inpatient encounter) after any discharge (observation or inpatient encounter) from eligible units were reviewed; therefore, each hospitalization was a potential index hospitalization. We classified the preventability of each readmission with use of a previously described Likert scale with high interrater reliability.14 For these analyses, readmissions were considered preventable if the reviewing team rated them as either “more likely preventable” or “preventable in most circumstances.” Each readmission was also evaluated as planned or unplanned. Methods for readmission review and classification are in the Appendix.

We included all readmissions between July 2014 and June 2016. We compared the medical record review classifications with the assessments from each of the four measures of pediatric readmission. We calculated sensitivity and specificity for both outcomes (planned/unplanned and preventable/not preventable) for all four measures. For standardization of discussion, we categorized description of measure performance as “very poor” as less than 50%, “poor” between 50%-75%, “fair” as 75%-85%, “good” as 85%-90%, “very good” as 90%-95% and excellent as greater than 95%. We also calculated positive and negative predictive value (PPV and NPV) over plausible ranges of prevalence using the sensitivity and specificity of each comparison (Appendix).

Of note, certain exclusions are outlined by the PACR and PPR algorithms. The PACR evaluates only readmission events that occur in children younger than 18 years. The PPR algorithm does not assign preventability if either the index or readmission event is classified as an observation stay or if it is part of a larger chain of readmissions.

RESULTS

Among 30-day readmissions considered, 1,643 were eligible for medical record review; 1,125 reviews were completed by the clinical teams (68.5%). The median time to readmission was 7 days (interquartile range [IQR], 4-18). Most children were non-Hispanic White (71%) or Black (20%). The median age at hospitalization was 2.3 years (IQR 0.4-12.1). Most children had Medicaid (56%) or private (41%) insurance. Most of the reviews were performed in cardiology (43%) and hospital medicine (37%) with patients in neurology (13%) and neonatology (7%) constituting the remaining reviews. Uncontrolled advancement of chronic disease was the most common readmission category on medical record review (25.1%), followed by unrelated readmission (20.7%), scheduled readmission (20.4%), and progression of acute disease (16.6%) (Appendix Table 2).

Assessment of Preventable and Unplanned Readmissions

On multidisciplinary medical record review, most readmissions were classified as not preventable (84.5%). Specifically, 64% were not preventable and unplanned; 20% were deemed not preventable and planned. Only 15% were classified as unplanned and preventable and 1% as planned and preventable (Appendix Figure: Population A/B).

Matching Chart Review to the Four Algorithms

All 1,125 readmissions were assessed by the all-cause and time flag readmission measures (Appendix Figure: Population A/B). After applying algorithm exclusions (details in Appendix), only 804 of the 1,125 (71.5%) reviewed readmissions matched for PACR readmission comparison (Appendix Figure: Population C); 487 of the 1,125 (43.3%) of the reviewed readmissions matched for PPR comparison (Appendix Figure: Population D).

All-Cause

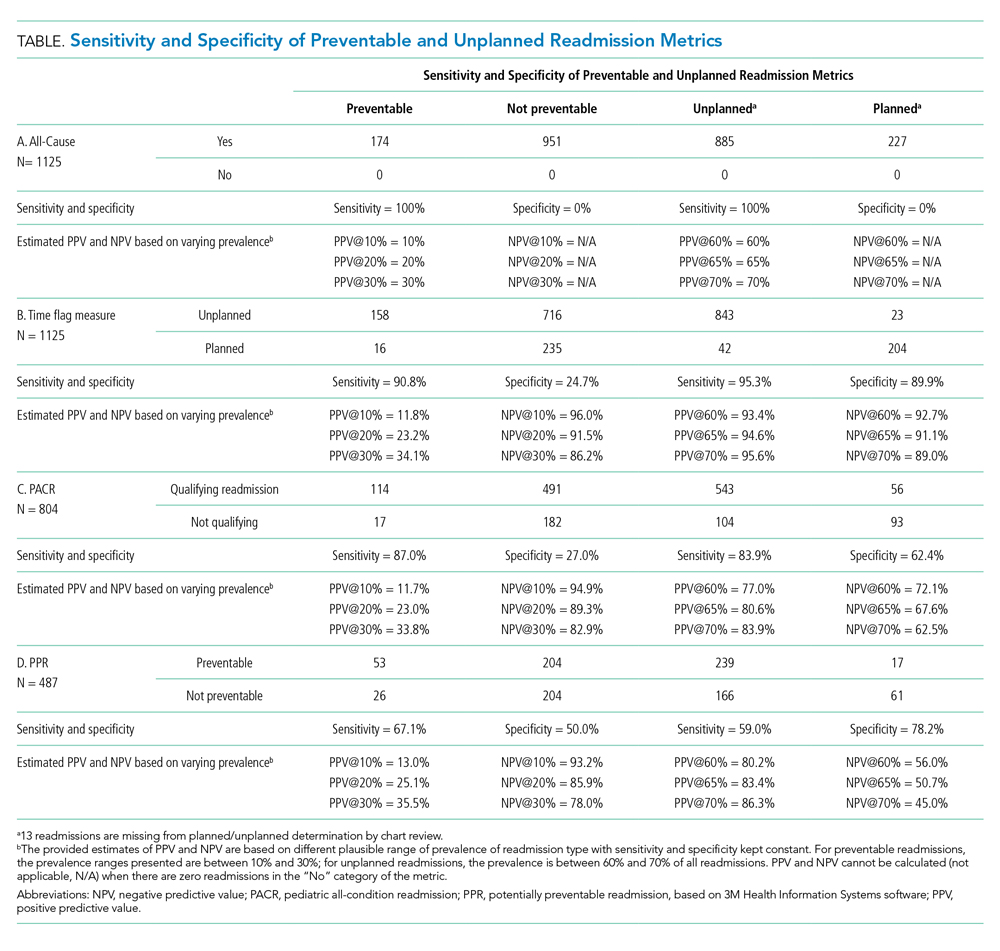

Because all-cause determines only if a readmission occurs, the measure is by definition 100% sensitive and 0% specific in both assessment of preventability and unplanned readmission (Table: Section A).

Time Flag

The time flag measure identified 80% (866/1,112) of the readmissions as unplanned. This measure had very good sensitivity but very poor specificity in identifying preventable readmissions, which corresponded to very poor PPV and good to excellent NPV. In terms of identifying unplanned readmissions, the time flag measure had excellent sensitivity and very good specificity, which corresponded to very good to excellent PPV and good to very good NPV (Table: Section B).

PACR

The PACR algorithm identified 75% (599/796) of readmissions as unplanned. The PACR has good sensitivity but very poor specificity in identifying preventable readmissions, which corresponded to very poor PPV and fair to very good NPV. In terms of identifying unplanned readmissions, the PACR had fair sensitivity but poor specificity, which corresponded to fair PPV and poor NPV (Table: Section C).

PPR

The PPR algorithm identified 53% (257/487) of admissions as potentially preventable. The PPR algorithm had poor sensitivity and specificity in identifying preventable readmissions, which corresponded to very poor PPV and fair to very good NPV. In terms of identifying unplanned readmissions, the PPR algorithm had poor sensitivity and fair specificity in identifying unplanned readmissions, which corresponded to fair to good PPV and very poor to poor NPV (Table: Section D).

Evaluation of Excluded Readmission Events

Because both the PACR and PPR had large numbers of algorithm exclusions, we describe the preventability and unplanned assessment of the excluded readmission events. Both algorithms excluded preventable events. Of the 321 readmissions excluded by the PACR algorithm, 13.4% were classified as preventable by chart review. Likewise, 14.9% of 638 readmissions excluded by PPR were classified as preventable by chart review.

DISCUSSION

The ability to accurately capture preventable pediatric readmission is a goal for hospital quality experts and health policymakers alike. Of the four commonly used readmission measures to assess readmission, only PPR is designed to focus on preventability. Unfortunately, none of these four measures is adequately sensitive or specific to identify preventable readmissions; all measures had very poor PPV for preventability. Of the four measures, the time flag measure had the best sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for identifying unplanned readmissions.

The overall percentage of unplanned readmissions identified by both the time flag and by PACR measures match the overall percentage of unplanned readmissions identified in chart review: The time flag measure identified 80% of admissions as unplanned versus 79% identified by chart review (Appendix Figure: Population A/B); PACR classified 75% as unplanned versus 81% identified by chart review for PACR-eligible readmissions (Appendix Figure: Population C). In contrast, the PPR algorithm classified many more readmissions as potentially preventable (53%) than were identified by chart review at only 16% (Appendix Figure: Population D). The PACR and PPR algorithms also exclude a significant number of readmissions that are unplanned and a smaller, but not trivial, number of readmissions that are preventable; these exclusions limit their accuracy.

The ability to apply these four measures in real time during a hospitalization varies by metric. Two of the measures, the all-cause and time flag, can be applied during a readmission event, which is appealing for quality improvement initiatives. These measures allow for notification of providers that a current hospitalization is a readmission event, which allows providers the opportunity to learn from these events as they occur (Appendix Table 1). While “unplanned” is not the same as “potentially preventable,” almost all potentially preventable readmissions are unplanned; therefore, accurately identifying unplanned readmissions is more beneficial than all-cause. Additionally, a low all-cause readmission rate can be indicative of poor access to scheduled procedures. Nevertheless, all-cause readmission is sometimes used to measure quality.1,8 While the time flag measure may be more useful for quality improvement initiatives and hospital providers, it relies on hospital registration time, which is not widely available in administrative data sources and, therefore, has limited usefulness to policymakers.

Both PACR and PPR require administrative claims analysis, which is appealing from a policy standpoint. However, the reliance on claims data means the inclusion/exclusion of events can occur only retrospectively, which limits the usefulness of these measures in learning and intervening in real time. When the two measures are compared, PACR offers better sensitivity and PPR offers better specificity with regard to identifying unplanned readmission. The PPR software overcalls preventable readmissions, identifying more readmissions as preventable than there actually are. Nevertheless, Medicaid in several states uses PPR for payment incentive.1,15-17 Given the poor performance of PPR in assessing both preventable and unplanned pediatric readmission, the use of this measure as a quality metric should be limited.

This study should be considered in the context of several limitations. Because the assessment of preventability was determined as part of a learning quality improvement collaborative and not as a planned research endeavor, not all readmission reviews were completed nor were other existent tools18 that allow for preventability assessment via more structured medical record review used. Second, we reviewed cases only from certain clinical services, which would limit generalizability of these findings to all pediatric admissions. However, given the low sensitivity and specificity of some of the metrics, we would not anticipate that the addition of other types of admissions would improve the sensitivity and specificity enough to ensure reliability. Third, while we relied on an established method to determine preventability, prior work has demonstrated that additional information gathered from families may change preventability.19 Finally, due to the exclusions required by the PPR and PACR algorithms, not all readmission events were reviewed. However, these exclusions reflect the actual specifications of use for both measures.

CONCLUSION

The PPR software has poor fidelity in identifying preventable and unplanned pediatric readmission; this finding has broad policy implications given how widely it is used by state Medicaid offices to assess financial penalties. Among the four pediatric readmission measures used, the time flag metric best identifies unplanned readmissions.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding

Dr Auger’s research is supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS204735-01A1). The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number 5UL1TR001425-04. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Readmission rates are frequently used as a hospital quality metric, with use including payment incentive at the hospital level,1 specific condition quality measurement,2 balancing measures for quality improvement projects,3-5 transition success,6,7 and use in public hospital rankings.8 Currently, four methods are commonly used to evaluate pediatric readmissions, each with strengths and limitations, including the following (Appendix Table 1):

1. All-cause readmissions: A measure of any readmission within a given time period regardless of the reason for readmission.9

2. Unplanned readmission/time flag: A measure intended to identify unplanned readmissions. This measure relies on time designations within the electronic health record. The time between hospital registration and admission is calculated, and if the readmission is registered more than 24 hours prior to admission, the readmission is considered planned.10 Hereafter, this measure will be referred to as the time flag measure.

3. Pediatric all-condition readmission (PACR): A measure intended to identify unplanned readmission through the exclusion of certain procedures and diagnoses.11

4. Potentially preventable readmission (PPR): A method to identify preventable readmissions based on a proprietary algorithm developed by

While all four of these measures are used to assess quality, there is little known about these measures’ ability to exclude planned readmissions and identify only preventable pediatric readmission, which conceptually is most relevant to the quality of care. However, many of these measures were not intended to capture preventability, but instead capture the related issue of whether the readmission was planned. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the four readmission measures as they relate to both preventability and unplanned status as determined through medical record review with multidisciplinary care provider input.

METHODS

As part of a hospital-wide readmission reduction quality improvement collaborative at a free-standing tertiary care children’s hospital, clinicians from hospital medicine, cardiology, neonatology, and neurology teams reviewed 30-day readmissions using a standardized abstraction tool. All readmission events (observation or inpatient encounter) after any discharge (observation or inpatient encounter) from eligible units were reviewed; therefore, each hospitalization was a potential index hospitalization. We classified the preventability of each readmission with use of a previously described Likert scale with high interrater reliability.14 For these analyses, readmissions were considered preventable if the reviewing team rated them as either “more likely preventable” or “preventable in most circumstances.” Each readmission was also evaluated as planned or unplanned. Methods for readmission review and classification are in the Appendix.

We included all readmissions between July 2014 and June 2016. We compared the medical record review classifications with the assessments from each of the four measures of pediatric readmission. We calculated sensitivity and specificity for both outcomes (planned/unplanned and preventable/not preventable) for all four measures. For standardization of discussion, we categorized description of measure performance as “very poor” as less than 50%, “poor” between 50%-75%, “fair” as 75%-85%, “good” as 85%-90%, “very good” as 90%-95% and excellent as greater than 95%. We also calculated positive and negative predictive value (PPV and NPV) over plausible ranges of prevalence using the sensitivity and specificity of each comparison (Appendix).

Of note, certain exclusions are outlined by the PACR and PPR algorithms. The PACR evaluates only readmission events that occur in children younger than 18 years. The PPR algorithm does not assign preventability if either the index or readmission event is classified as an observation stay or if it is part of a larger chain of readmissions.

RESULTS

Among 30-day readmissions considered, 1,643 were eligible for medical record review; 1,125 reviews were completed by the clinical teams (68.5%). The median time to readmission was 7 days (interquartile range [IQR], 4-18). Most children were non-Hispanic White (71%) or Black (20%). The median age at hospitalization was 2.3 years (IQR 0.4-12.1). Most children had Medicaid (56%) or private (41%) insurance. Most of the reviews were performed in cardiology (43%) and hospital medicine (37%) with patients in neurology (13%) and neonatology (7%) constituting the remaining reviews. Uncontrolled advancement of chronic disease was the most common readmission category on medical record review (25.1%), followed by unrelated readmission (20.7%), scheduled readmission (20.4%), and progression of acute disease (16.6%) (Appendix Table 2).

Assessment of Preventable and Unplanned Readmissions

On multidisciplinary medical record review, most readmissions were classified as not preventable (84.5%). Specifically, 64% were not preventable and unplanned; 20% were deemed not preventable and planned. Only 15% were classified as unplanned and preventable and 1% as planned and preventable (Appendix Figure: Population A/B).

Matching Chart Review to the Four Algorithms

All 1,125 readmissions were assessed by the all-cause and time flag readmission measures (Appendix Figure: Population A/B). After applying algorithm exclusions (details in Appendix), only 804 of the 1,125 (71.5%) reviewed readmissions matched for PACR readmission comparison (Appendix Figure: Population C); 487 of the 1,125 (43.3%) of the reviewed readmissions matched for PPR comparison (Appendix Figure: Population D).

All-Cause

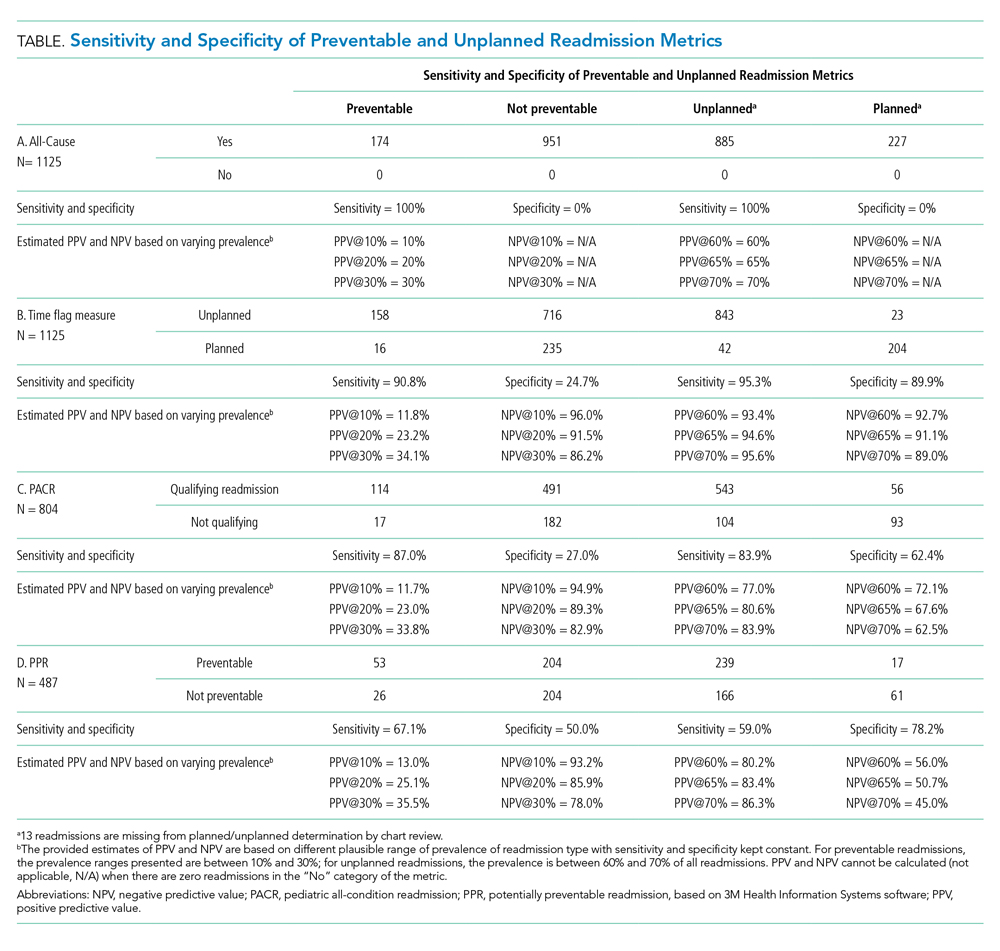

Because all-cause determines only if a readmission occurs, the measure is by definition 100% sensitive and 0% specific in both assessment of preventability and unplanned readmission (Table: Section A).

Time Flag

The time flag measure identified 80% (866/1,112) of the readmissions as unplanned. This measure had very good sensitivity but very poor specificity in identifying preventable readmissions, which corresponded to very poor PPV and good to excellent NPV. In terms of identifying unplanned readmissions, the time flag measure had excellent sensitivity and very good specificity, which corresponded to very good to excellent PPV and good to very good NPV (Table: Section B).

PACR

The PACR algorithm identified 75% (599/796) of readmissions as unplanned. The PACR has good sensitivity but very poor specificity in identifying preventable readmissions, which corresponded to very poor PPV and fair to very good NPV. In terms of identifying unplanned readmissions, the PACR had fair sensitivity but poor specificity, which corresponded to fair PPV and poor NPV (Table: Section C).

PPR

The PPR algorithm identified 53% (257/487) of admissions as potentially preventable. The PPR algorithm had poor sensitivity and specificity in identifying preventable readmissions, which corresponded to very poor PPV and fair to very good NPV. In terms of identifying unplanned readmissions, the PPR algorithm had poor sensitivity and fair specificity in identifying unplanned readmissions, which corresponded to fair to good PPV and very poor to poor NPV (Table: Section D).

Evaluation of Excluded Readmission Events

Because both the PACR and PPR had large numbers of algorithm exclusions, we describe the preventability and unplanned assessment of the excluded readmission events. Both algorithms excluded preventable events. Of the 321 readmissions excluded by the PACR algorithm, 13.4% were classified as preventable by chart review. Likewise, 14.9% of 638 readmissions excluded by PPR were classified as preventable by chart review.

DISCUSSION

The ability to accurately capture preventable pediatric readmission is a goal for hospital quality experts and health policymakers alike. Of the four commonly used readmission measures to assess readmission, only PPR is designed to focus on preventability. Unfortunately, none of these four measures is adequately sensitive or specific to identify preventable readmissions; all measures had very poor PPV for preventability. Of the four measures, the time flag measure had the best sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for identifying unplanned readmissions.

The overall percentage of unplanned readmissions identified by both the time flag and by PACR measures match the overall percentage of unplanned readmissions identified in chart review: The time flag measure identified 80% of admissions as unplanned versus 79% identified by chart review (Appendix Figure: Population A/B); PACR classified 75% as unplanned versus 81% identified by chart review for PACR-eligible readmissions (Appendix Figure: Population C). In contrast, the PPR algorithm classified many more readmissions as potentially preventable (53%) than were identified by chart review at only 16% (Appendix Figure: Population D). The PACR and PPR algorithms also exclude a significant number of readmissions that are unplanned and a smaller, but not trivial, number of readmissions that are preventable; these exclusions limit their accuracy.

The ability to apply these four measures in real time during a hospitalization varies by metric. Two of the measures, the all-cause and time flag, can be applied during a readmission event, which is appealing for quality improvement initiatives. These measures allow for notification of providers that a current hospitalization is a readmission event, which allows providers the opportunity to learn from these events as they occur (Appendix Table 1). While “unplanned” is not the same as “potentially preventable,” almost all potentially preventable readmissions are unplanned; therefore, accurately identifying unplanned readmissions is more beneficial than all-cause. Additionally, a low all-cause readmission rate can be indicative of poor access to scheduled procedures. Nevertheless, all-cause readmission is sometimes used to measure quality.1,8 While the time flag measure may be more useful for quality improvement initiatives and hospital providers, it relies on hospital registration time, which is not widely available in administrative data sources and, therefore, has limited usefulness to policymakers.

Both PACR and PPR require administrative claims analysis, which is appealing from a policy standpoint. However, the reliance on claims data means the inclusion/exclusion of events can occur only retrospectively, which limits the usefulness of these measures in learning and intervening in real time. When the two measures are compared, PACR offers better sensitivity and PPR offers better specificity with regard to identifying unplanned readmission. The PPR software overcalls preventable readmissions, identifying more readmissions as preventable than there actually are. Nevertheless, Medicaid in several states uses PPR for payment incentive.1,15-17 Given the poor performance of PPR in assessing both preventable and unplanned pediatric readmission, the use of this measure as a quality metric should be limited.

This study should be considered in the context of several limitations. Because the assessment of preventability was determined as part of a learning quality improvement collaborative and not as a planned research endeavor, not all readmission reviews were completed nor were other existent tools18 that allow for preventability assessment via more structured medical record review used. Second, we reviewed cases only from certain clinical services, which would limit generalizability of these findings to all pediatric admissions. However, given the low sensitivity and specificity of some of the metrics, we would not anticipate that the addition of other types of admissions would improve the sensitivity and specificity enough to ensure reliability. Third, while we relied on an established method to determine preventability, prior work has demonstrated that additional information gathered from families may change preventability.19 Finally, due to the exclusions required by the PPR and PACR algorithms, not all readmission events were reviewed. However, these exclusions reflect the actual specifications of use for both measures.

CONCLUSION

The PPR software has poor fidelity in identifying preventable and unplanned pediatric readmission; this finding has broad policy implications given how widely it is used by state Medicaid offices to assess financial penalties. Among the four pediatric readmission measures used, the time flag metric best identifies unplanned readmissions.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding

Dr Auger’s research is supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS204735-01A1). The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number 5UL1TR001425-04. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

1. State Medicaid Payment Policies for Inpatient Hospital Services. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission; December 2018. Accessed June 1, 2019. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/macpac-inpatient-hospital-payment-landscapes/

2. Mangione-Smith R, Zhou C, Williams DJ, et al. Pediatric Respiratory Illness Measurement System (PRIMES) scores and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):e20190242. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0242

3. Biondi EA, McCulloh R, Staggs VS, et al. Reducing Variability in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE): a national quality initiative. Pediatrics. 2019;144(3):e20182201. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2201

4. Statile AM, Schondelmeyer AC, Thomson JE, et al. Improving discharge efficiency in medically complex pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20153832. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3832

5. White CM, Statile AM, White DL, et al. Using quality improvement to optimise paediatric discharge efficiency. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):428-436. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002556

6. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al; H20 Trial Study Group. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: the Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3919

7. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482

8. Olmsted MG, Powell R, Murphy J, Bell Denise, Stanley M, Sanchz R. Methodology: U.S. News & World Report Best Children’s Hospitals 2019-20. U.S. News & World Report; June 17, 2019. Accessed June 16, 2020. https://www.usnews.com/static/documents/health/best-hospitals/BCH_Methodology_2019-20.pdf

9. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3527

10. Auger KA, Mueller EL, Weinberg SH, et al. A validated method for identifying unplanned pediatric readmission. J Pediatr. 2016;170:105-12.e102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.051

11. Readmissions-Content. Boston Children’s Hospital. Accessed April 8, 2019. http://www.childrenshospital.org/research-and-innovation/research/centers/center-of-excellence-for-pediatric-quality-measurement-cepqm/cepqm-measures/pediatric-readmissions/content

12. Gay JC, Agrawal R, Auger KA, et al. Rates and impact of potentially preventable readmissions at children’s hospitals. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):613-9.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.052

13. Auger KA, Teufel RJ, Harris JM, et al. Children’s hospital characteristics and readmission metrics. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20161720. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1720

14. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of early readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0820

15. Potentially Preventable Events. Texas Health and Human Services. Accessed May 19, 2019. https://hhs.texas.gov/about-hhs/process-improvement/medicaid-chip-quality-efficiency-improvement/potentially-preventable-events

16. Potentially Preventable Readmissions. New York State Department of Health. Accessed May 28, 2019. https://regs.health.ny.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/recently_adopted_regulations/2011-02-23_potentially_preventable_readmissions.pdf

17. Potentially Preventable Readmissions Policy. Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. Accessed May 28, 2019. https://www.illinois.gov/hfs/SiteCollectionDocuments/PPR_Overview.pdf

18. Jonas JA, Devon EP, Ronan JC, et al. Determining preventability of pediatric readmissions using fault tree analysis. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):329-335. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2555

19. Toomey SL, Peltz A, Loren S, et al. Potentially preventable 30-day hospital readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20154182. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4182

1. State Medicaid Payment Policies for Inpatient Hospital Services. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission; December 2018. Accessed June 1, 2019. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/macpac-inpatient-hospital-payment-landscapes/

2. Mangione-Smith R, Zhou C, Williams DJ, et al. Pediatric Respiratory Illness Measurement System (PRIMES) scores and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):e20190242. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0242

3. Biondi EA, McCulloh R, Staggs VS, et al. Reducing Variability in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE): a national quality initiative. Pediatrics. 2019;144(3):e20182201. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2201

4. Statile AM, Schondelmeyer AC, Thomson JE, et al. Improving discharge efficiency in medically complex pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20153832. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3832

5. White CM, Statile AM, White DL, et al. Using quality improvement to optimise paediatric discharge efficiency. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):428-436. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002556

6. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al; H20 Trial Study Group. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: the Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3919

7. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482

8. Olmsted MG, Powell R, Murphy J, Bell Denise, Stanley M, Sanchz R. Methodology: U.S. News & World Report Best Children’s Hospitals 2019-20. U.S. News & World Report; June 17, 2019. Accessed June 16, 2020. https://www.usnews.com/static/documents/health/best-hospitals/BCH_Methodology_2019-20.pdf

9. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3527

10. Auger KA, Mueller EL, Weinberg SH, et al. A validated method for identifying unplanned pediatric readmission. J Pediatr. 2016;170:105-12.e102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.051

11. Readmissions-Content. Boston Children’s Hospital. Accessed April 8, 2019. http://www.childrenshospital.org/research-and-innovation/research/centers/center-of-excellence-for-pediatric-quality-measurement-cepqm/cepqm-measures/pediatric-readmissions/content

12. Gay JC, Agrawal R, Auger KA, et al. Rates and impact of potentially preventable readmissions at children’s hospitals. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):613-9.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.052

13. Auger KA, Teufel RJ, Harris JM, et al. Children’s hospital characteristics and readmission metrics. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20161720. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1720

14. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of early readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0820

15. Potentially Preventable Events. Texas Health and Human Services. Accessed May 19, 2019. https://hhs.texas.gov/about-hhs/process-improvement/medicaid-chip-quality-efficiency-improvement/potentially-preventable-events

16. Potentially Preventable Readmissions. New York State Department of Health. Accessed May 28, 2019. https://regs.health.ny.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/recently_adopted_regulations/2011-02-23_potentially_preventable_readmissions.pdf

17. Potentially Preventable Readmissions Policy. Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. Accessed May 28, 2019. https://www.illinois.gov/hfs/SiteCollectionDocuments/PPR_Overview.pdf

18. Jonas JA, Devon EP, Ronan JC, et al. Determining preventability of pediatric readmissions using fault tree analysis. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):329-335. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2555

19. Toomey SL, Peltz A, Loren S, et al. Potentially preventable 30-day hospital readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20154182. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4182

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Effect of Parental Adverse Childhood Experiences and Resilience on a Child’s Healthcare Reutilization

Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, include exposure to abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction (eg, having a parent who is mentally ill) as a child.1 Exposure to ACEs affects health into adulthood, with a dose-response relationship between ACEs and a range of comorbidities.1 Adults with 6 or more ACEs have a 20-year shorter life expectancy than do those with no ACEs.1 Still, ACEs are static; once experienced, that experience cannot be undone. However, resilience, or positive adaptation in the context of adversity, can be protective, buffering the negative effects of ACEs.2,3 Protective factors that promote resilience include social capital, such as positive relationships with caregivers and peers.3

With their clear link to health outcomes across the life-course, there is a movement for pediatricians to screen children for ACEs4 and to develop strategies that promote resilience in children, parents, and families. However, screening a child for adversity has challenges because younger children may not have experienced an adverse exposure, or they may be unable to voice their experiences. Studies have demonstrated that parental adversity, or ACEs, may be a marker for childhood adversity.5,6 Biological models also support this potential intergenerational effect of ACEs. Chronic exposure to stress, including ACEs, results in elevated cortisol via a dysregulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which results in chronic inflammation.7 This “toxic stress” is prolonged, severe in intensity, and can lead to epigenetic changes that may be passed on to the next generation.8,9

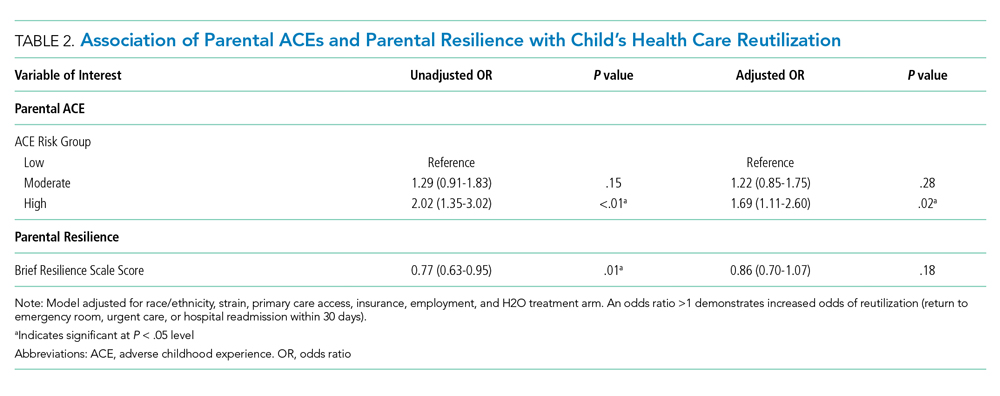

Hospitalization of an ill child, and the transition to home after that hospitalization, is a stressful event for children and families.10 This stress may be relevant to parents that have a history of a high rate of ACEs or a current low degree of resilience. Our previous work demonstrated that, in the inpatient setting, parents with high ACEs (≥4) or low resilience have increased coping difficulty 14 days after their child’s hospital discharge.11 Our objective here was to evaluate whether a parent’s ACEs and/or resilience would also be associated with that child’s likelihood of reutilization. We hypothesized that more parental ACEs and/or lower parental resilience would be associated with revisits the emergency room, urgent care, or hospital readmissions.

METHODS

Participants and Study Design

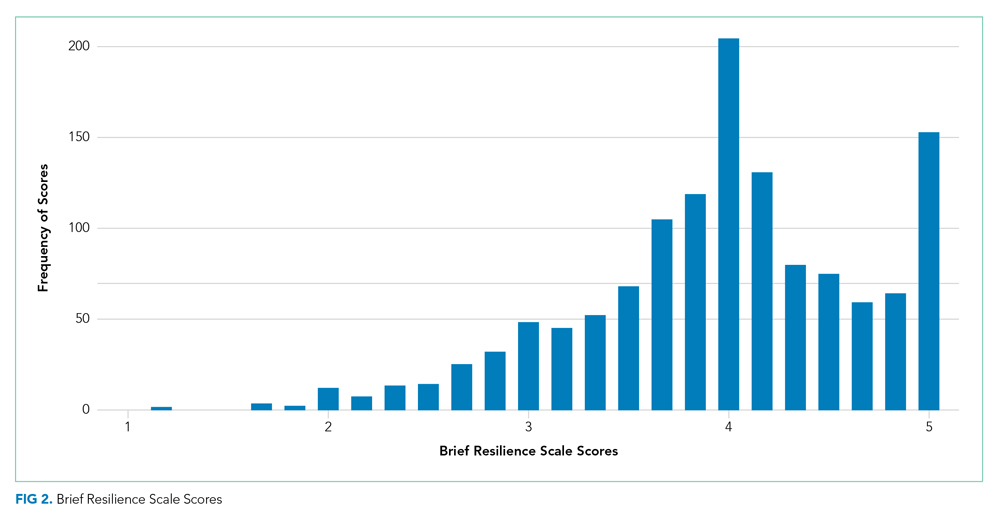

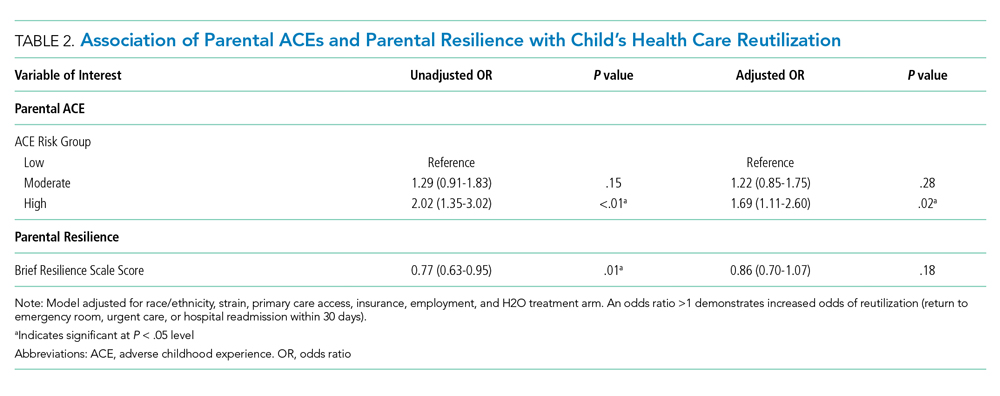

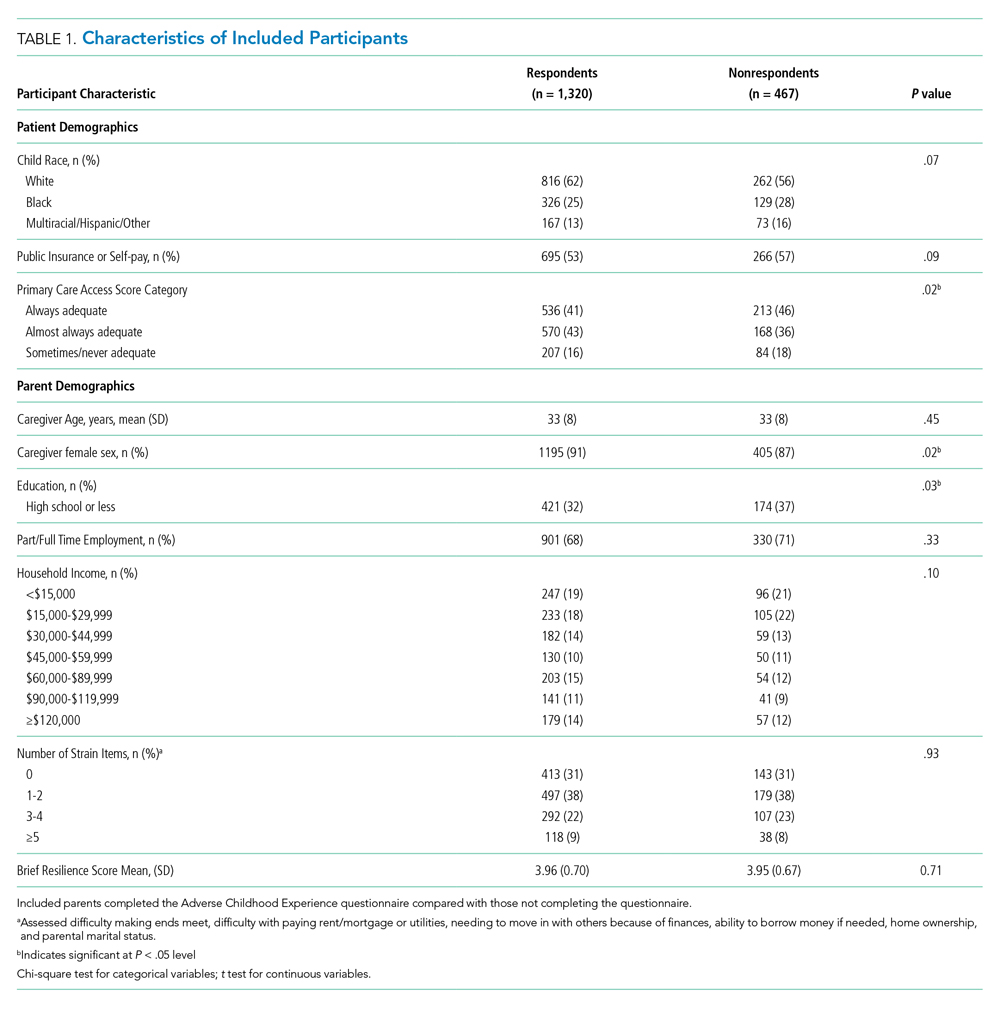

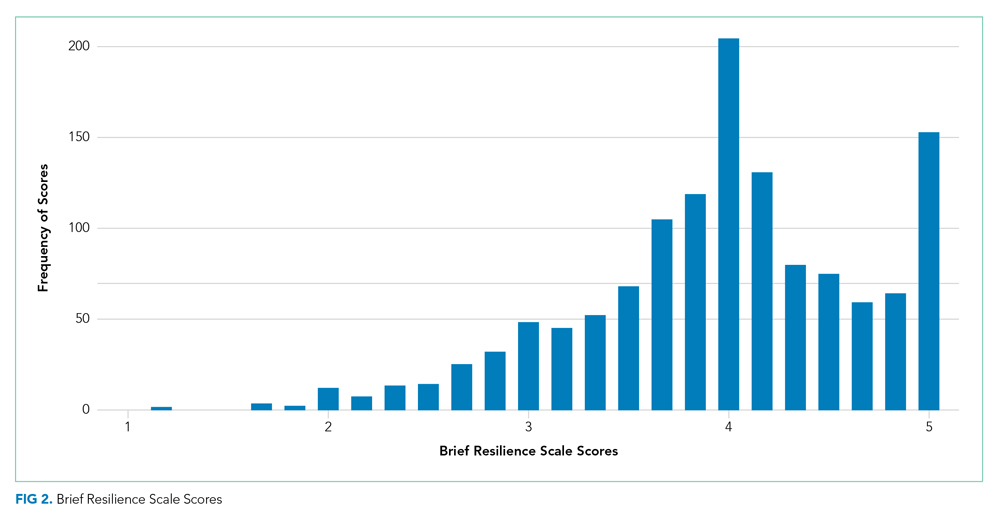

We conducted a prospective cohort study of parents of hospitalized children recruited from the “Hospital-to-Home Outcomes” Studies (H2O I and H2O II).12,13 H2O I and II were prospective, single-center, randomized controlled trials designed to determine the effectiveness of either a nurse-led transitional home visit (H2O I) or telephone call (H2O II) on 30-day unplanned healthcare reutilization. The trials and this study were approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Institutional Review Board. All parents provided written informed consent.