User login

Things We Do For No Reason: Prealbumin Testing to Diagnose Malnutrition in the Hospitalized Patient

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE PRESENTATION

A 34-year-old man is admitted for a complicated urinary tract infection related to a chronic in-dwelling Foley catheter. The patient suffered a spinal cord injury at the C4/C5 level as a result of a motor vehicle accident 10 years ago and is confined to a motorized wheelchair. He is an engineer and lives independently but has caregivers. His body mass index (BMI) is 18.5 kg/m2, and he reports his weight has been stable. He has slight muscle atrophy of the biceps, triceps, interosseous muscles, and quadriceps. The patient reports that he eats well, has no chronic conditions, and has not had any gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, anorexia, nausea, diarrhea) over the last six months. You consider whether to order a serum prealbumin test to assess for possible malnutrition.

BACKGROUND

The presence of malnutrition in hospitalized patients is widely recognized as an independent predictor of hospital mortality.1 According to the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN), malnutrition is defined as “an acute, subacute or chronic state of nutrition, in which varying degrees of overnutrition or undernutrition with or without inflammatory activity have led to a change in body composition and diminished function.”2 In one large European study, patients screening positive for being at risk of malnutrition had a 12-fold increase in hospital mortality.1

Inpatient malnutrition is remarkably underdocumented. Studies using chart reviews have found a prevalence of malnutrition in hospitalized patients of between 20% and 50%, and only 3% of hospital discharges are associated with a diagnostic code for malnutrition.3–5 Appropriate diagnosis and documentation of malnutrition is important given the profound prognostic and management implications of a malnutrition diagnosis. Appropriate documentation benefits health systems as malnutrition documentation increases expected mortality, thereby improving the observed-to-expected mortality ratio.

Serum prealbumin testing is widely available and frequently ordered in the inpatient setting. In a query we performed of the large aggregate Cerner Electronic Health Record database, HealthFacts, which includes data from inpatient encounters for approximately 700 United States hospitals, prealbumin tests were ordered 129,152 times in 2015. This activity corresponds to estimated total charges of $2,562,375 based on the 2015 clinical laboratory fee schedule.6

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK PREALBUMIN DIAGNOSES MALNUTRITION

Prealbumin is synthesized in the liver and released into circulation prior to excretion by the kidneys and gastrointestinal tract. Prealbumin transports thyroxine, triiodothyronine, and holo-retinol binding protein and, as a result, is also known as transthyretin.7 It was first proposed as a nutritional marker in 1972 with the publication of a study that showed low levels of prealbumin in 40 children with kwashiorkor that improved with intensive dietary supplementation.8 The shorter half-life of prealbumin (2.5 days) as compared with other identified nutritional markers, such as albumin, indicate that it would be suitable for detecting rapid changes in nutritional status.

WHY PREALBUMIN IS NOT HELPFUL FOR DIAGNOSING MALNUTRITION

Prealbumin Is Not Specific

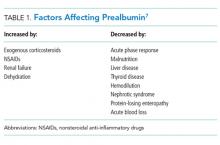

An ideal nutritional marker should be specific enough that changes in this marker reflect changes in nutritional status.9 While there are many systemic factors that affect nutritional markers, such as prealbumin (Table 1), the acute phase response triggered by inflammation is the most significant confounder in the acutely ill hospitalized patient.9 This response to infection, stress, and malignancy leads to an increase in proinflammatory cytokines, increased liver synthesis of inflammatory proteins, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), and increased vascular permeability. Prealbumin is a negative acute phase reactant that decreases in concentration during the stress response due to slowed synthesis and extravasation.9 In a study of 24 patients with severe sepsis and trauma, levels of prealbumin inversely correlated with CRP, a reflection of the stress response, and returned to normal when CRP levels normalized. Neither prealbumin nor CRP, however, correlated with total body protein changes.10 Unfortunately, many studies supporting the use of prealbumin as a nutritional marker do not address the role of the acute phase response in their results. These studies include the original report on prealbumin in kwashiorkor, a condition known to be associated with a high rate of infectious diseases that can trigger the acute phase response.9 A consensus statement from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) and ASPEN noted that prealbumin is an indicator of inflammation and lacks the specificity to diagnose malnutrition.11

Prealbumin Is Not Sensitive

A sensitive laboratory test for malnutrition should allow for detection of malnutrition at an early stage.9 However, patients who demonstrate severe malnutrition without a coexisting inflammatory state do not consistently show low levels of prealbumin. In a systematic review of 20 studies in nondiseased malnourished patients, only two studies, both of which assessed patients with anorexia nervosa, had a mean prealbumin below normal (<20 mg/dL), and this finding corresponded to patient populations with mean BMIs less than 12 kg/m2. More importantly, normal prealbumin levels were seen in groups of patients with a mean BMI as low as 12.9 kg/m2.12 Analysis by AND found insufficient evidence to support a correlation between prealbumin and weight loss in anorexia nervosa, calorie restricted diets, or starvation.13 The data suggest that prealbumin lacks sufficient sensitivity to consistently detect cases of malnutrition easily diagnosed by history and/or physical exam.

Prealbumin Is Not Consistently Responsive to Nutritional Interventions

An accurate marker for malnutrition should improve when nutritional intervention results in adequate nutritional intake.9 While some studies have shown improvements in prealbumin in the setting of a nutritional intervention, many of these works are subject to the same limitations related to specificity and lack of control for concurrent inflammatory processes. In a retrospective study, prealbumin increased significantly in 102 patients receiving TPN for one week. Unfortunately, patients with renal or hepatic disease were excluded, and the role of inflammation was not assessed.14 Institutionalized patients with Alzheimer’s disease and normal CRP levels showed a statistically significant increase in weight gain, arm muscle circumference, and triceps skin-fold thickness following a nutritional program without a notable change in prealbumin.15 In a study assessing the relationship of prealbumin, CRP, and nutritional intake, critically ill populations receiving less than or greater than 60% of their estimated caloric needs showed no significant difference in prealbumin. In fact, prealbumin levels were only correlated with CRP levels.16 This finding argues against the routine use of prealbumin for nutrition monitoring in the acutely ill hospitalized patient.

Prealbumin Is Not Consistently Correlated with Health Outcomes

Even if prealbumin increased consistently in response to nutritional intervention, whether this change corresponds to an improvement in clinical outcomes has yet to be demonstrated.9 In 2005, Koretz reviewed 99 clinical trials and concluded that even when changes in nutritional markers are seen with nutritional support, the “changes in nutritional markers do not predict clinical outcomes.”17

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD: USE NONBIOLOGIC METHODS FOR SCREENING AND DIAGNOSING MALNUTRITION

Given the lack of a suitable biologic assay to identify malnutrition, dieticians and clinicians must rely on other means to assess malnutrition. Professional societies, including ASPEN and the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, have proposed different guidelines for the screening and assessment of malnutrition (Table 2).11,18 In 2016, these organizations, along with the Latin American Federation of Nutritional Therapy, Clinical Nutrition, and Metabolism and the Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Society of Asia, formed The Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM). In 2017, the GLIM taskforce agreed on clinically relevant diagnostic variables for the screening and assessment of malnutrition, including reduced food intake (anorexia), nonvolitional weight loss, (reduced) lean mass, status of disease burden and inflammation, and low body mass index or underweight status.19

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Do not use prealbumin to screen for or diagnose malnutrition.

- Consult with local dietitians to ensure that your institutional approach is in agreement with consensus recommendations.

CONCLUSION

In revisiting the case above, the patient does not have clear evidence of malnutrition based on his history (stable weight and good reported nutritional intake), although he does have a low BMI of 18.5 kg/m2. Rather than prealbumin testing, which would likely be low secondary to the acute phase response, he would better benefit from a nutrition-focused history and physical exam.

The uncertainties faced by clinicians in diagnosing malnutrition cannot readily be resolved by relying on a solitary laboratory marker (eg, prealbumin) or a stand-alone assessment protocol. The data obtained reflect the need for multidisciplinary teams of dieticians and clinicians to contextualize each patient’s medical history and ensure that the selected metrics are used appropriately to aid in diagnosis and documentation. We advocate that clinicians not routinely use prealbumin to screen for, confirm the diagnosis of, or assess the severity of malnutrition in the hospitalized patient.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Sorensen J, Kondrup J, Prokopowicz J, et al. EuroOOPS: an international, multicentre study to implement nutritional risk screening and evaluate clinical outcome. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2008;27(3):340-349. PubMed

2. Mueller C, Compher C, Ellen DM, American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) Board of Directors. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in adults. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35(1):16-24. PubMed

3. Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Rämsch C, et al. Frequency of malnutrition in older adults: a multinational perspective using the mini nutritional assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1734-1738. PubMed

4. Robinson MK, Trujillo EB, Mogensen KM, Rounds J, McManus K, Jacobs DO. Improving nutritional screening of hospitalized patients: the role of prealbumin. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003;27(6):389-395; quiz 439. PubMed

5. Corkins MR, Guenter P, DiMaria-Ghalili RA, et al. Malnutrition diagnoses in hospitalized patients: United States, 2010. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(2):186-195. PubMed

6. Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule Files. cms.org. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files.html. Published September 29, 2016. Accessed January 5, 2018.

7. Myron Johnson A, Merlini G, Sheldon J, Ichihara K, Scientific Division Committee on Plasma Proteins (C-PP), International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC). Clinical indications for plasma protein assays: transthyretin (prealbumin) in inflammation and malnutrition. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45(3):419-426. PubMed

8. Ingenbleek Y, De Visscher M, De Nayer P. Measurement of prealbumin as index of protein-calorie malnutrition. Lancet. 1972;2(7768):106-109. PubMed

9. Barbosa-Silva MCG. Subjective and objective nutritional assessment methods: what do they really assess? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11(3):248-254. PubMed

10. Clark MA, Hentzen BTH, Plank LD, Hill GL. Sequential changes in insulin-like growth factor 1, plasma proteins, and total body protein in severe sepsis and multiple injury. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1996;20(5):363-370. PubMed

11. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, et al. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738. PubMed

12. Lee JL, Oh ES, Lee RW, Finucane TE. Serum albumin and prealbumin in calorically restricted, nondiseased individuals: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2015;128(9):1023.e1-22. PubMed

13. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Evidence Analysis Library. Nutrition Screening (NSCR) Systematic Review (2009-2010). https://www.andeal.org/tmp/pdf-print-919C51237950859AE3E15F978CEF49D8.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2017.

14. Sawicky CP, Nippo J, Winkler MF, Albina JE. Adequate energy intake and improved prealbumin concentration as indicators of the response to total parenteral nutrition. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92(10):1266-1268. PubMed

15. Van Wymelbeke V, Guédon A, Maniere D, Manckoundia P, Pfitzenmeyer P. A 6-month follow-up of nutritional status in institutionalized patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2004;8(6):505-508. PubMed

16. Davis CJ, Sowa D, Keim KS, Kinnare K, Peterson S. The use of prealbumin and C-reactive protein for monitoring nutrition support in adult patients receiving enteral nutrition in an urban medical center. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36(2):197-204. PubMed

17. Koretz RL. Death, morbidity and economics are the only end points for trials. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64(3):277-284. PubMed

18. Cederholm T, Bosaeus I, Barazzoni R, et al. Diagnostic criteria for malnutrition - an ESPEN consensus statement. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2015;34(3):335-340. PubMed

19. Jensen GL, Cederholm T. Global leadership initiative on malnutrition: progress report from ASPEN clinical nutrition week 2017. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. April 2017:148607117707761. PubMed

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE PRESENTATION

A 34-year-old man is admitted for a complicated urinary tract infection related to a chronic in-dwelling Foley catheter. The patient suffered a spinal cord injury at the C4/C5 level as a result of a motor vehicle accident 10 years ago and is confined to a motorized wheelchair. He is an engineer and lives independently but has caregivers. His body mass index (BMI) is 18.5 kg/m2, and he reports his weight has been stable. He has slight muscle atrophy of the biceps, triceps, interosseous muscles, and quadriceps. The patient reports that he eats well, has no chronic conditions, and has not had any gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, anorexia, nausea, diarrhea) over the last six months. You consider whether to order a serum prealbumin test to assess for possible malnutrition.

BACKGROUND

The presence of malnutrition in hospitalized patients is widely recognized as an independent predictor of hospital mortality.1 According to the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN), malnutrition is defined as “an acute, subacute or chronic state of nutrition, in which varying degrees of overnutrition or undernutrition with or without inflammatory activity have led to a change in body composition and diminished function.”2 In one large European study, patients screening positive for being at risk of malnutrition had a 12-fold increase in hospital mortality.1

Inpatient malnutrition is remarkably underdocumented. Studies using chart reviews have found a prevalence of malnutrition in hospitalized patients of between 20% and 50%, and only 3% of hospital discharges are associated with a diagnostic code for malnutrition.3–5 Appropriate diagnosis and documentation of malnutrition is important given the profound prognostic and management implications of a malnutrition diagnosis. Appropriate documentation benefits health systems as malnutrition documentation increases expected mortality, thereby improving the observed-to-expected mortality ratio.

Serum prealbumin testing is widely available and frequently ordered in the inpatient setting. In a query we performed of the large aggregate Cerner Electronic Health Record database, HealthFacts, which includes data from inpatient encounters for approximately 700 United States hospitals, prealbumin tests were ordered 129,152 times in 2015. This activity corresponds to estimated total charges of $2,562,375 based on the 2015 clinical laboratory fee schedule.6

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK PREALBUMIN DIAGNOSES MALNUTRITION

Prealbumin is synthesized in the liver and released into circulation prior to excretion by the kidneys and gastrointestinal tract. Prealbumin transports thyroxine, triiodothyronine, and holo-retinol binding protein and, as a result, is also known as transthyretin.7 It was first proposed as a nutritional marker in 1972 with the publication of a study that showed low levels of prealbumin in 40 children with kwashiorkor that improved with intensive dietary supplementation.8 The shorter half-life of prealbumin (2.5 days) as compared with other identified nutritional markers, such as albumin, indicate that it would be suitable for detecting rapid changes in nutritional status.

WHY PREALBUMIN IS NOT HELPFUL FOR DIAGNOSING MALNUTRITION

Prealbumin Is Not Specific

An ideal nutritional marker should be specific enough that changes in this marker reflect changes in nutritional status.9 While there are many systemic factors that affect nutritional markers, such as prealbumin (Table 1), the acute phase response triggered by inflammation is the most significant confounder in the acutely ill hospitalized patient.9 This response to infection, stress, and malignancy leads to an increase in proinflammatory cytokines, increased liver synthesis of inflammatory proteins, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), and increased vascular permeability. Prealbumin is a negative acute phase reactant that decreases in concentration during the stress response due to slowed synthesis and extravasation.9 In a study of 24 patients with severe sepsis and trauma, levels of prealbumin inversely correlated with CRP, a reflection of the stress response, and returned to normal when CRP levels normalized. Neither prealbumin nor CRP, however, correlated with total body protein changes.10 Unfortunately, many studies supporting the use of prealbumin as a nutritional marker do not address the role of the acute phase response in their results. These studies include the original report on prealbumin in kwashiorkor, a condition known to be associated with a high rate of infectious diseases that can trigger the acute phase response.9 A consensus statement from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) and ASPEN noted that prealbumin is an indicator of inflammation and lacks the specificity to diagnose malnutrition.11

Prealbumin Is Not Sensitive

A sensitive laboratory test for malnutrition should allow for detection of malnutrition at an early stage.9 However, patients who demonstrate severe malnutrition without a coexisting inflammatory state do not consistently show low levels of prealbumin. In a systematic review of 20 studies in nondiseased malnourished patients, only two studies, both of which assessed patients with anorexia nervosa, had a mean prealbumin below normal (<20 mg/dL), and this finding corresponded to patient populations with mean BMIs less than 12 kg/m2. More importantly, normal prealbumin levels were seen in groups of patients with a mean BMI as low as 12.9 kg/m2.12 Analysis by AND found insufficient evidence to support a correlation between prealbumin and weight loss in anorexia nervosa, calorie restricted diets, or starvation.13 The data suggest that prealbumin lacks sufficient sensitivity to consistently detect cases of malnutrition easily diagnosed by history and/or physical exam.

Prealbumin Is Not Consistently Responsive to Nutritional Interventions

An accurate marker for malnutrition should improve when nutritional intervention results in adequate nutritional intake.9 While some studies have shown improvements in prealbumin in the setting of a nutritional intervention, many of these works are subject to the same limitations related to specificity and lack of control for concurrent inflammatory processes. In a retrospective study, prealbumin increased significantly in 102 patients receiving TPN for one week. Unfortunately, patients with renal or hepatic disease were excluded, and the role of inflammation was not assessed.14 Institutionalized patients with Alzheimer’s disease and normal CRP levels showed a statistically significant increase in weight gain, arm muscle circumference, and triceps skin-fold thickness following a nutritional program without a notable change in prealbumin.15 In a study assessing the relationship of prealbumin, CRP, and nutritional intake, critically ill populations receiving less than or greater than 60% of their estimated caloric needs showed no significant difference in prealbumin. In fact, prealbumin levels were only correlated with CRP levels.16 This finding argues against the routine use of prealbumin for nutrition monitoring in the acutely ill hospitalized patient.

Prealbumin Is Not Consistently Correlated with Health Outcomes

Even if prealbumin increased consistently in response to nutritional intervention, whether this change corresponds to an improvement in clinical outcomes has yet to be demonstrated.9 In 2005, Koretz reviewed 99 clinical trials and concluded that even when changes in nutritional markers are seen with nutritional support, the “changes in nutritional markers do not predict clinical outcomes.”17

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD: USE NONBIOLOGIC METHODS FOR SCREENING AND DIAGNOSING MALNUTRITION

Given the lack of a suitable biologic assay to identify malnutrition, dieticians and clinicians must rely on other means to assess malnutrition. Professional societies, including ASPEN and the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, have proposed different guidelines for the screening and assessment of malnutrition (Table 2).11,18 In 2016, these organizations, along with the Latin American Federation of Nutritional Therapy, Clinical Nutrition, and Metabolism and the Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Society of Asia, formed The Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM). In 2017, the GLIM taskforce agreed on clinically relevant diagnostic variables for the screening and assessment of malnutrition, including reduced food intake (anorexia), nonvolitional weight loss, (reduced) lean mass, status of disease burden and inflammation, and low body mass index or underweight status.19

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Do not use prealbumin to screen for or diagnose malnutrition.

- Consult with local dietitians to ensure that your institutional approach is in agreement with consensus recommendations.

CONCLUSION

In revisiting the case above, the patient does not have clear evidence of malnutrition based on his history (stable weight and good reported nutritional intake), although he does have a low BMI of 18.5 kg/m2. Rather than prealbumin testing, which would likely be low secondary to the acute phase response, he would better benefit from a nutrition-focused history and physical exam.

The uncertainties faced by clinicians in diagnosing malnutrition cannot readily be resolved by relying on a solitary laboratory marker (eg, prealbumin) or a stand-alone assessment protocol. The data obtained reflect the need for multidisciplinary teams of dieticians and clinicians to contextualize each patient’s medical history and ensure that the selected metrics are used appropriately to aid in diagnosis and documentation. We advocate that clinicians not routinely use prealbumin to screen for, confirm the diagnosis of, or assess the severity of malnutrition in the hospitalized patient.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE PRESENTATION

A 34-year-old man is admitted for a complicated urinary tract infection related to a chronic in-dwelling Foley catheter. The patient suffered a spinal cord injury at the C4/C5 level as a result of a motor vehicle accident 10 years ago and is confined to a motorized wheelchair. He is an engineer and lives independently but has caregivers. His body mass index (BMI) is 18.5 kg/m2, and he reports his weight has been stable. He has slight muscle atrophy of the biceps, triceps, interosseous muscles, and quadriceps. The patient reports that he eats well, has no chronic conditions, and has not had any gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, anorexia, nausea, diarrhea) over the last six months. You consider whether to order a serum prealbumin test to assess for possible malnutrition.

BACKGROUND

The presence of malnutrition in hospitalized patients is widely recognized as an independent predictor of hospital mortality.1 According to the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN), malnutrition is defined as “an acute, subacute or chronic state of nutrition, in which varying degrees of overnutrition or undernutrition with or without inflammatory activity have led to a change in body composition and diminished function.”2 In one large European study, patients screening positive for being at risk of malnutrition had a 12-fold increase in hospital mortality.1

Inpatient malnutrition is remarkably underdocumented. Studies using chart reviews have found a prevalence of malnutrition in hospitalized patients of between 20% and 50%, and only 3% of hospital discharges are associated with a diagnostic code for malnutrition.3–5 Appropriate diagnosis and documentation of malnutrition is important given the profound prognostic and management implications of a malnutrition diagnosis. Appropriate documentation benefits health systems as malnutrition documentation increases expected mortality, thereby improving the observed-to-expected mortality ratio.

Serum prealbumin testing is widely available and frequently ordered in the inpatient setting. In a query we performed of the large aggregate Cerner Electronic Health Record database, HealthFacts, which includes data from inpatient encounters for approximately 700 United States hospitals, prealbumin tests were ordered 129,152 times in 2015. This activity corresponds to estimated total charges of $2,562,375 based on the 2015 clinical laboratory fee schedule.6

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK PREALBUMIN DIAGNOSES MALNUTRITION

Prealbumin is synthesized in the liver and released into circulation prior to excretion by the kidneys and gastrointestinal tract. Prealbumin transports thyroxine, triiodothyronine, and holo-retinol binding protein and, as a result, is also known as transthyretin.7 It was first proposed as a nutritional marker in 1972 with the publication of a study that showed low levels of prealbumin in 40 children with kwashiorkor that improved with intensive dietary supplementation.8 The shorter half-life of prealbumin (2.5 days) as compared with other identified nutritional markers, such as albumin, indicate that it would be suitable for detecting rapid changes in nutritional status.

WHY PREALBUMIN IS NOT HELPFUL FOR DIAGNOSING MALNUTRITION

Prealbumin Is Not Specific

An ideal nutritional marker should be specific enough that changes in this marker reflect changes in nutritional status.9 While there are many systemic factors that affect nutritional markers, such as prealbumin (Table 1), the acute phase response triggered by inflammation is the most significant confounder in the acutely ill hospitalized patient.9 This response to infection, stress, and malignancy leads to an increase in proinflammatory cytokines, increased liver synthesis of inflammatory proteins, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), and increased vascular permeability. Prealbumin is a negative acute phase reactant that decreases in concentration during the stress response due to slowed synthesis and extravasation.9 In a study of 24 patients with severe sepsis and trauma, levels of prealbumin inversely correlated with CRP, a reflection of the stress response, and returned to normal when CRP levels normalized. Neither prealbumin nor CRP, however, correlated with total body protein changes.10 Unfortunately, many studies supporting the use of prealbumin as a nutritional marker do not address the role of the acute phase response in their results. These studies include the original report on prealbumin in kwashiorkor, a condition known to be associated with a high rate of infectious diseases that can trigger the acute phase response.9 A consensus statement from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) and ASPEN noted that prealbumin is an indicator of inflammation and lacks the specificity to diagnose malnutrition.11

Prealbumin Is Not Sensitive

A sensitive laboratory test for malnutrition should allow for detection of malnutrition at an early stage.9 However, patients who demonstrate severe malnutrition without a coexisting inflammatory state do not consistently show low levels of prealbumin. In a systematic review of 20 studies in nondiseased malnourished patients, only two studies, both of which assessed patients with anorexia nervosa, had a mean prealbumin below normal (<20 mg/dL), and this finding corresponded to patient populations with mean BMIs less than 12 kg/m2. More importantly, normal prealbumin levels were seen in groups of patients with a mean BMI as low as 12.9 kg/m2.12 Analysis by AND found insufficient evidence to support a correlation between prealbumin and weight loss in anorexia nervosa, calorie restricted diets, or starvation.13 The data suggest that prealbumin lacks sufficient sensitivity to consistently detect cases of malnutrition easily diagnosed by history and/or physical exam.

Prealbumin Is Not Consistently Responsive to Nutritional Interventions

An accurate marker for malnutrition should improve when nutritional intervention results in adequate nutritional intake.9 While some studies have shown improvements in prealbumin in the setting of a nutritional intervention, many of these works are subject to the same limitations related to specificity and lack of control for concurrent inflammatory processes. In a retrospective study, prealbumin increased significantly in 102 patients receiving TPN for one week. Unfortunately, patients with renal or hepatic disease were excluded, and the role of inflammation was not assessed.14 Institutionalized patients with Alzheimer’s disease and normal CRP levels showed a statistically significant increase in weight gain, arm muscle circumference, and triceps skin-fold thickness following a nutritional program without a notable change in prealbumin.15 In a study assessing the relationship of prealbumin, CRP, and nutritional intake, critically ill populations receiving less than or greater than 60% of their estimated caloric needs showed no significant difference in prealbumin. In fact, prealbumin levels were only correlated with CRP levels.16 This finding argues against the routine use of prealbumin for nutrition monitoring in the acutely ill hospitalized patient.

Prealbumin Is Not Consistently Correlated with Health Outcomes

Even if prealbumin increased consistently in response to nutritional intervention, whether this change corresponds to an improvement in clinical outcomes has yet to be demonstrated.9 In 2005, Koretz reviewed 99 clinical trials and concluded that even when changes in nutritional markers are seen with nutritional support, the “changes in nutritional markers do not predict clinical outcomes.”17

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD: USE NONBIOLOGIC METHODS FOR SCREENING AND DIAGNOSING MALNUTRITION

Given the lack of a suitable biologic assay to identify malnutrition, dieticians and clinicians must rely on other means to assess malnutrition. Professional societies, including ASPEN and the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, have proposed different guidelines for the screening and assessment of malnutrition (Table 2).11,18 In 2016, these organizations, along with the Latin American Federation of Nutritional Therapy, Clinical Nutrition, and Metabolism and the Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Society of Asia, formed The Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM). In 2017, the GLIM taskforce agreed on clinically relevant diagnostic variables for the screening and assessment of malnutrition, including reduced food intake (anorexia), nonvolitional weight loss, (reduced) lean mass, status of disease burden and inflammation, and low body mass index or underweight status.19

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Do not use prealbumin to screen for or diagnose malnutrition.

- Consult with local dietitians to ensure that your institutional approach is in agreement with consensus recommendations.

CONCLUSION

In revisiting the case above, the patient does not have clear evidence of malnutrition based on his history (stable weight and good reported nutritional intake), although he does have a low BMI of 18.5 kg/m2. Rather than prealbumin testing, which would likely be low secondary to the acute phase response, he would better benefit from a nutrition-focused history and physical exam.

The uncertainties faced by clinicians in diagnosing malnutrition cannot readily be resolved by relying on a solitary laboratory marker (eg, prealbumin) or a stand-alone assessment protocol. The data obtained reflect the need for multidisciplinary teams of dieticians and clinicians to contextualize each patient’s medical history and ensure that the selected metrics are used appropriately to aid in diagnosis and documentation. We advocate that clinicians not routinely use prealbumin to screen for, confirm the diagnosis of, or assess the severity of malnutrition in the hospitalized patient.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Sorensen J, Kondrup J, Prokopowicz J, et al. EuroOOPS: an international, multicentre study to implement nutritional risk screening and evaluate clinical outcome. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2008;27(3):340-349. PubMed

2. Mueller C, Compher C, Ellen DM, American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) Board of Directors. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in adults. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35(1):16-24. PubMed

3. Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Rämsch C, et al. Frequency of malnutrition in older adults: a multinational perspective using the mini nutritional assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1734-1738. PubMed

4. Robinson MK, Trujillo EB, Mogensen KM, Rounds J, McManus K, Jacobs DO. Improving nutritional screening of hospitalized patients: the role of prealbumin. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003;27(6):389-395; quiz 439. PubMed

5. Corkins MR, Guenter P, DiMaria-Ghalili RA, et al. Malnutrition diagnoses in hospitalized patients: United States, 2010. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(2):186-195. PubMed

6. Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule Files. cms.org. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files.html. Published September 29, 2016. Accessed January 5, 2018.

7. Myron Johnson A, Merlini G, Sheldon J, Ichihara K, Scientific Division Committee on Plasma Proteins (C-PP), International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC). Clinical indications for plasma protein assays: transthyretin (prealbumin) in inflammation and malnutrition. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45(3):419-426. PubMed

8. Ingenbleek Y, De Visscher M, De Nayer P. Measurement of prealbumin as index of protein-calorie malnutrition. Lancet. 1972;2(7768):106-109. PubMed

9. Barbosa-Silva MCG. Subjective and objective nutritional assessment methods: what do they really assess? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11(3):248-254. PubMed

10. Clark MA, Hentzen BTH, Plank LD, Hill GL. Sequential changes in insulin-like growth factor 1, plasma proteins, and total body protein in severe sepsis and multiple injury. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1996;20(5):363-370. PubMed

11. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, et al. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738. PubMed

12. Lee JL, Oh ES, Lee RW, Finucane TE. Serum albumin and prealbumin in calorically restricted, nondiseased individuals: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2015;128(9):1023.e1-22. PubMed

13. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Evidence Analysis Library. Nutrition Screening (NSCR) Systematic Review (2009-2010). https://www.andeal.org/tmp/pdf-print-919C51237950859AE3E15F978CEF49D8.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2017.

14. Sawicky CP, Nippo J, Winkler MF, Albina JE. Adequate energy intake and improved prealbumin concentration as indicators of the response to total parenteral nutrition. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92(10):1266-1268. PubMed

15. Van Wymelbeke V, Guédon A, Maniere D, Manckoundia P, Pfitzenmeyer P. A 6-month follow-up of nutritional status in institutionalized patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2004;8(6):505-508. PubMed

16. Davis CJ, Sowa D, Keim KS, Kinnare K, Peterson S. The use of prealbumin and C-reactive protein for monitoring nutrition support in adult patients receiving enteral nutrition in an urban medical center. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36(2):197-204. PubMed

17. Koretz RL. Death, morbidity and economics are the only end points for trials. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64(3):277-284. PubMed

18. Cederholm T, Bosaeus I, Barazzoni R, et al. Diagnostic criteria for malnutrition - an ESPEN consensus statement. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2015;34(3):335-340. PubMed

19. Jensen GL, Cederholm T. Global leadership initiative on malnutrition: progress report from ASPEN clinical nutrition week 2017. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. April 2017:148607117707761. PubMed

1. Sorensen J, Kondrup J, Prokopowicz J, et al. EuroOOPS: an international, multicentre study to implement nutritional risk screening and evaluate clinical outcome. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2008;27(3):340-349. PubMed

2. Mueller C, Compher C, Ellen DM, American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) Board of Directors. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in adults. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35(1):16-24. PubMed

3. Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Rämsch C, et al. Frequency of malnutrition in older adults: a multinational perspective using the mini nutritional assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1734-1738. PubMed

4. Robinson MK, Trujillo EB, Mogensen KM, Rounds J, McManus K, Jacobs DO. Improving nutritional screening of hospitalized patients: the role of prealbumin. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003;27(6):389-395; quiz 439. PubMed

5. Corkins MR, Guenter P, DiMaria-Ghalili RA, et al. Malnutrition diagnoses in hospitalized patients: United States, 2010. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(2):186-195. PubMed

6. Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule Files. cms.org. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files.html. Published September 29, 2016. Accessed January 5, 2018.

7. Myron Johnson A, Merlini G, Sheldon J, Ichihara K, Scientific Division Committee on Plasma Proteins (C-PP), International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC). Clinical indications for plasma protein assays: transthyretin (prealbumin) in inflammation and malnutrition. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45(3):419-426. PubMed

8. Ingenbleek Y, De Visscher M, De Nayer P. Measurement of prealbumin as index of protein-calorie malnutrition. Lancet. 1972;2(7768):106-109. PubMed

9. Barbosa-Silva MCG. Subjective and objective nutritional assessment methods: what do they really assess? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11(3):248-254. PubMed

10. Clark MA, Hentzen BTH, Plank LD, Hill GL. Sequential changes in insulin-like growth factor 1, plasma proteins, and total body protein in severe sepsis and multiple injury. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1996;20(5):363-370. PubMed

11. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, et al. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738. PubMed

12. Lee JL, Oh ES, Lee RW, Finucane TE. Serum albumin and prealbumin in calorically restricted, nondiseased individuals: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2015;128(9):1023.e1-22. PubMed

13. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Evidence Analysis Library. Nutrition Screening (NSCR) Systematic Review (2009-2010). https://www.andeal.org/tmp/pdf-print-919C51237950859AE3E15F978CEF49D8.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2017.

14. Sawicky CP, Nippo J, Winkler MF, Albina JE. Adequate energy intake and improved prealbumin concentration as indicators of the response to total parenteral nutrition. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92(10):1266-1268. PubMed

15. Van Wymelbeke V, Guédon A, Maniere D, Manckoundia P, Pfitzenmeyer P. A 6-month follow-up of nutritional status in institutionalized patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2004;8(6):505-508. PubMed

16. Davis CJ, Sowa D, Keim KS, Kinnare K, Peterson S. The use of prealbumin and C-reactive protein for monitoring nutrition support in adult patients receiving enteral nutrition in an urban medical center. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36(2):197-204. PubMed

17. Koretz RL. Death, morbidity and economics are the only end points for trials. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64(3):277-284. PubMed

18. Cederholm T, Bosaeus I, Barazzoni R, et al. Diagnostic criteria for malnutrition - an ESPEN consensus statement. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2015;34(3):335-340. PubMed

19. Jensen GL, Cederholm T. Global leadership initiative on malnutrition: progress report from ASPEN clinical nutrition week 2017. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. April 2017:148607117707761. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Once-Weekly Antibiotic Might Be Effective for Treatment of Acute Bacterial Skin Infections

Background: Acute bacterial skin infections are common and often require hospitalization for intravenous antibiotic administration. Treatment covering gram-positive bacteria usually is indicated. Dalbavancin is effective against gram-positives, including MRSA. Its long half-life makes it an attractive alternative to other commonly used antibiotics, which require more frequent dosing.

Study design: Phase 3, double-blinded RCT.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,312 patients with acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections with signs of systemic infection requiring intravenous antibiotics to receive dalbavancin on days one and eight, with placebo on other days, or several doses of vancomycin with an option to switch to oral linezolid. The primary endpoint was cessation of spread of erythema and temperature of =37.6°C at 48–72 hours. Secondary endpoints included a decrease in lesion area of =20% at 48–72 hours and clinical success at end of therapy (determined by clinical and historical features). Results of the primary endpoint were similar with dalbavancin and vancomycin-linezolid groups (79.7% and 79.8%, respectively) and were within 10 percentage points of noninferiority. The secondary endpoints were similar between both groups. Limitations of the study were the early primary endpoint, lack of noninferiority analysis of the secondary endpoints, and cost-effective analysis.

Bottom line: Once-weekly dalbavancin appears to be similarly efficacious to intravenous vancomycin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections in terms of outcomes within 48–72 hours of therapy and might provide an alternative to continued inpatient hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics in stable patients.

Citation: Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169-2179.

Background: Acute bacterial skin infections are common and often require hospitalization for intravenous antibiotic administration. Treatment covering gram-positive bacteria usually is indicated. Dalbavancin is effective against gram-positives, including MRSA. Its long half-life makes it an attractive alternative to other commonly used antibiotics, which require more frequent dosing.

Study design: Phase 3, double-blinded RCT.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,312 patients with acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections with signs of systemic infection requiring intravenous antibiotics to receive dalbavancin on days one and eight, with placebo on other days, or several doses of vancomycin with an option to switch to oral linezolid. The primary endpoint was cessation of spread of erythema and temperature of =37.6°C at 48–72 hours. Secondary endpoints included a decrease in lesion area of =20% at 48–72 hours and clinical success at end of therapy (determined by clinical and historical features). Results of the primary endpoint were similar with dalbavancin and vancomycin-linezolid groups (79.7% and 79.8%, respectively) and were within 10 percentage points of noninferiority. The secondary endpoints were similar between both groups. Limitations of the study were the early primary endpoint, lack of noninferiority analysis of the secondary endpoints, and cost-effective analysis.

Bottom line: Once-weekly dalbavancin appears to be similarly efficacious to intravenous vancomycin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections in terms of outcomes within 48–72 hours of therapy and might provide an alternative to continued inpatient hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics in stable patients.

Citation: Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169-2179.

Background: Acute bacterial skin infections are common and often require hospitalization for intravenous antibiotic administration. Treatment covering gram-positive bacteria usually is indicated. Dalbavancin is effective against gram-positives, including MRSA. Its long half-life makes it an attractive alternative to other commonly used antibiotics, which require more frequent dosing.

Study design: Phase 3, double-blinded RCT.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,312 patients with acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections with signs of systemic infection requiring intravenous antibiotics to receive dalbavancin on days one and eight, with placebo on other days, or several doses of vancomycin with an option to switch to oral linezolid. The primary endpoint was cessation of spread of erythema and temperature of =37.6°C at 48–72 hours. Secondary endpoints included a decrease in lesion area of =20% at 48–72 hours and clinical success at end of therapy (determined by clinical and historical features). Results of the primary endpoint were similar with dalbavancin and vancomycin-linezolid groups (79.7% and 79.8%, respectively) and were within 10 percentage points of noninferiority. The secondary endpoints were similar between both groups. Limitations of the study were the early primary endpoint, lack of noninferiority analysis of the secondary endpoints, and cost-effective analysis.

Bottom line: Once-weekly dalbavancin appears to be similarly efficacious to intravenous vancomycin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections in terms of outcomes within 48–72 hours of therapy and might provide an alternative to continued inpatient hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics in stable patients.

Citation: Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169-2179.

Once-Weekly Antibiotic Might Be Effective for Treatment of Acute Bacterial Skin Infections

Clinical question: Is once-weekly intravenous dalbavancin as effective as conventional therapy for the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections?

Background: Acute bacterial skin infections are common and often require hospitalization for intravenous antibiotic administration. Treatment covering gram-positive bacteria usually is indicated. Dalbavancin is effective against gram-positives, including MRSA. Its long half-life makes it an attractive alternative to other commonly used antibiotics, which require more frequent dosing.

Study design: Phase 3, double-blinded RCT.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,312 patients with acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections with signs of systemic infection requiring intravenous antibiotics to receive dalbavancin on days one and eight, with placebo on other days, or several doses of vancomycin with an option to switch to oral linezolid. The primary endpoint was cessation of spread of erythema and temperature of ≤37.6°C at 48-72 hours. Secondary endpoints included a decrease in lesion area of ≥20% at 48-72 hours and clinical success at end of therapy (determined by clinical and historical features).

Results of the primary endpoint were similar with dalbavancin and vancomycin-linezolid groups (79.7% and 79.8%, respectively) and were within 10 percentage points of noninferiority. The secondary endpoints were similar between both groups.

Limitations of the study were the early primary endpoint, lack of noninferiority analysis of the secondary endpoints, and cost-effective analysis.

Bottom line: Once-weekly dalbavancin appears to be similarly efficacious to intravenous vancomycin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections in terms of outcomes within 48-72 hours of therapy and might provide an alternative to continued inpatient hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics in stable patients.

Citation: Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169-2179.

Clinical question: Is once-weekly intravenous dalbavancin as effective as conventional therapy for the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections?

Background: Acute bacterial skin infections are common and often require hospitalization for intravenous antibiotic administration. Treatment covering gram-positive bacteria usually is indicated. Dalbavancin is effective against gram-positives, including MRSA. Its long half-life makes it an attractive alternative to other commonly used antibiotics, which require more frequent dosing.

Study design: Phase 3, double-blinded RCT.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,312 patients with acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections with signs of systemic infection requiring intravenous antibiotics to receive dalbavancin on days one and eight, with placebo on other days, or several doses of vancomycin with an option to switch to oral linezolid. The primary endpoint was cessation of spread of erythema and temperature of ≤37.6°C at 48-72 hours. Secondary endpoints included a decrease in lesion area of ≥20% at 48-72 hours and clinical success at end of therapy (determined by clinical and historical features).

Results of the primary endpoint were similar with dalbavancin and vancomycin-linezolid groups (79.7% and 79.8%, respectively) and were within 10 percentage points of noninferiority. The secondary endpoints were similar between both groups.

Limitations of the study were the early primary endpoint, lack of noninferiority analysis of the secondary endpoints, and cost-effective analysis.

Bottom line: Once-weekly dalbavancin appears to be similarly efficacious to intravenous vancomycin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections in terms of outcomes within 48-72 hours of therapy and might provide an alternative to continued inpatient hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics in stable patients.

Citation: Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169-2179.

Clinical question: Is once-weekly intravenous dalbavancin as effective as conventional therapy for the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections?

Background: Acute bacterial skin infections are common and often require hospitalization for intravenous antibiotic administration. Treatment covering gram-positive bacteria usually is indicated. Dalbavancin is effective against gram-positives, including MRSA. Its long half-life makes it an attractive alternative to other commonly used antibiotics, which require more frequent dosing.

Study design: Phase 3, double-blinded RCT.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,312 patients with acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections with signs of systemic infection requiring intravenous antibiotics to receive dalbavancin on days one and eight, with placebo on other days, or several doses of vancomycin with an option to switch to oral linezolid. The primary endpoint was cessation of spread of erythema and temperature of ≤37.6°C at 48-72 hours. Secondary endpoints included a decrease in lesion area of ≥20% at 48-72 hours and clinical success at end of therapy (determined by clinical and historical features).

Results of the primary endpoint were similar with dalbavancin and vancomycin-linezolid groups (79.7% and 79.8%, respectively) and were within 10 percentage points of noninferiority. The secondary endpoints were similar between both groups.

Limitations of the study were the early primary endpoint, lack of noninferiority analysis of the secondary endpoints, and cost-effective analysis.

Bottom line: Once-weekly dalbavancin appears to be similarly efficacious to intravenous vancomycin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections in terms of outcomes within 48-72 hours of therapy and might provide an alternative to continued inpatient hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics in stable patients.

Citation: Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169-2179.

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Outperforms Noctural Oxygen for Blood Pressure Reduction

Clinical question: What is the effect of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or supplemental oxygen on ambulatory blood pressures and markers of cardiovascular risk when combined with sleep hygiene education in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and coronary artery disease or cardiac risk factors?

Background: OSA is considered a risk factor for the development of hypertension. One meta-analysis showed reduction of mean arterial pressure (MAP) with CPAP therapy, but randomized controlled data on blood pressure reduction with treatment of OSA is lacking.

Study design: Randomized, parallel-group trial.

Setting: Four outpatient cardiology practices.

Synopsis: Patients ages 45-75 with OSA were randomized to receive nocturnal CPAP and healthy lifestyle and sleep education (HLSE), nocturnal oxygen therapy and HSLE, or HSLE alone. The primary outcome was 24-hour MAP. Secondary outcomes included fasting blood glucose, lipid panel, insulin level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), and N-terminal pro-brain naturetic peptide.

Participants had high rates of diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. At 12 weeks, the CPAP arm experienced greater reductions in 24-hour MAP compared to both the nocturnal oxygen and HSLE arms (-2.8 mmHg [P=0.02] and -2.4 mmHg [P=0.04], respectively). No significant decrease in MAP was identified in the nocturnal oxygen arm when compared to the HSLE arm. The only significant difference in secondary outcomes was a decrease in CRP in the CPAP arm when compared to the HSLE arm, the clinical significance of which is unclear.

Bottom line: CPAP therapy with sleep hygiene education appears superior to nocturnal oxygen therapy with sleep hygiene education and sleep hygiene education alone in decreasing 24-hour MAP in patients with OSA and coronary artery disease or cardiac risk factors.

Citation: Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM, Mehra R, et al. CPAP versus oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(24):2276-2285.

Clinical question: What is the effect of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or supplemental oxygen on ambulatory blood pressures and markers of cardiovascular risk when combined with sleep hygiene education in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and coronary artery disease or cardiac risk factors?

Background: OSA is considered a risk factor for the development of hypertension. One meta-analysis showed reduction of mean arterial pressure (MAP) with CPAP therapy, but randomized controlled data on blood pressure reduction with treatment of OSA is lacking.

Study design: Randomized, parallel-group trial.

Setting: Four outpatient cardiology practices.

Synopsis: Patients ages 45-75 with OSA were randomized to receive nocturnal CPAP and healthy lifestyle and sleep education (HLSE), nocturnal oxygen therapy and HSLE, or HSLE alone. The primary outcome was 24-hour MAP. Secondary outcomes included fasting blood glucose, lipid panel, insulin level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), and N-terminal pro-brain naturetic peptide.

Participants had high rates of diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. At 12 weeks, the CPAP arm experienced greater reductions in 24-hour MAP compared to both the nocturnal oxygen and HSLE arms (-2.8 mmHg [P=0.02] and -2.4 mmHg [P=0.04], respectively). No significant decrease in MAP was identified in the nocturnal oxygen arm when compared to the HSLE arm. The only significant difference in secondary outcomes was a decrease in CRP in the CPAP arm when compared to the HSLE arm, the clinical significance of which is unclear.

Bottom line: CPAP therapy with sleep hygiene education appears superior to nocturnal oxygen therapy with sleep hygiene education and sleep hygiene education alone in decreasing 24-hour MAP in patients with OSA and coronary artery disease or cardiac risk factors.

Citation: Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM, Mehra R, et al. CPAP versus oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(24):2276-2285.

Clinical question: What is the effect of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or supplemental oxygen on ambulatory blood pressures and markers of cardiovascular risk when combined with sleep hygiene education in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and coronary artery disease or cardiac risk factors?

Background: OSA is considered a risk factor for the development of hypertension. One meta-analysis showed reduction of mean arterial pressure (MAP) with CPAP therapy, but randomized controlled data on blood pressure reduction with treatment of OSA is lacking.

Study design: Randomized, parallel-group trial.

Setting: Four outpatient cardiology practices.

Synopsis: Patients ages 45-75 with OSA were randomized to receive nocturnal CPAP and healthy lifestyle and sleep education (HLSE), nocturnal oxygen therapy and HSLE, or HSLE alone. The primary outcome was 24-hour MAP. Secondary outcomes included fasting blood glucose, lipid panel, insulin level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), and N-terminal pro-brain naturetic peptide.

Participants had high rates of diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. At 12 weeks, the CPAP arm experienced greater reductions in 24-hour MAP compared to both the nocturnal oxygen and HSLE arms (-2.8 mmHg [P=0.02] and -2.4 mmHg [P=0.04], respectively). No significant decrease in MAP was identified in the nocturnal oxygen arm when compared to the HSLE arm. The only significant difference in secondary outcomes was a decrease in CRP in the CPAP arm when compared to the HSLE arm, the clinical significance of which is unclear.

Bottom line: CPAP therapy with sleep hygiene education appears superior to nocturnal oxygen therapy with sleep hygiene education and sleep hygiene education alone in decreasing 24-hour MAP in patients with OSA and coronary artery disease or cardiac risk factors.

Citation: Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM, Mehra R, et al. CPAP versus oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(24):2276-2285.

Lactate Clearance Portends Better Outcomes after Cardiac Arrest

Clinical question: Is greater lactate clearance following resuscitation from cardiac arrest associated with lower mortality and better neurologic outcomes?

Background: Recommendations from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation for monitoring serial lactate levels in post-resuscitation patients are based primarily on extrapolation from other conditions such as sepsis. Two single-retrospective analyses found effective lactate clearance was associated with decreased mortality. This association had not previously been validated in a multicenter, prospective study.

Study design: Multicenter, prospective, observational study.

Setting: Four urban, tertiary-care teaching hospitals.

Synopsis: Absolute lactate levels and the differences in the percent lactate change over 24 hours were compared in 100 patients who suffered out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Ninety-seven percent received therapeutic hypothermia, and overall survival was 46%. Survivors and patients with a good neurologic outcome had lower lactate levels at zero hours (4.1 vs. 7.3), 12 hours (2.2 vs. 6.0), and 24 hours (1.6 vs. 4.4) compared with nonsurvivors and patients with bad neurologic outcomes.

The percent lactate decreased was greater in survivors and in those with good neurologic outcomes (odds ratio, 2.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.1–4.4).

Nonsurvivors or those with poor neurologic outcomes were less likely to have received bystander CPR, to have suffered a witnessed arrest, or to have had a shockable rhythm at presentation. Superior lactate clearance in survivors and those with good neurologic outcomes suggests a potential role in developing markers of effective resuscitation.

Bottom line: Lower lactate levels and more effective clearance of lactate in patients following cardiac arrest are associated with improved survival and good neurologic outcome.

Citation: Donnino MW, Andersen LW, Giberson T, et al. Initial lactate and lactate change in post-cardiac arrest: a multicenter validation study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(8):1804-1811.

Clinical question: Is greater lactate clearance following resuscitation from cardiac arrest associated with lower mortality and better neurologic outcomes?

Background: Recommendations from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation for monitoring serial lactate levels in post-resuscitation patients are based primarily on extrapolation from other conditions such as sepsis. Two single-retrospective analyses found effective lactate clearance was associated with decreased mortality. This association had not previously been validated in a multicenter, prospective study.

Study design: Multicenter, prospective, observational study.

Setting: Four urban, tertiary-care teaching hospitals.

Synopsis: Absolute lactate levels and the differences in the percent lactate change over 24 hours were compared in 100 patients who suffered out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Ninety-seven percent received therapeutic hypothermia, and overall survival was 46%. Survivors and patients with a good neurologic outcome had lower lactate levels at zero hours (4.1 vs. 7.3), 12 hours (2.2 vs. 6.0), and 24 hours (1.6 vs. 4.4) compared with nonsurvivors and patients with bad neurologic outcomes.

The percent lactate decreased was greater in survivors and in those with good neurologic outcomes (odds ratio, 2.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.1–4.4).

Nonsurvivors or those with poor neurologic outcomes were less likely to have received bystander CPR, to have suffered a witnessed arrest, or to have had a shockable rhythm at presentation. Superior lactate clearance in survivors and those with good neurologic outcomes suggests a potential role in developing markers of effective resuscitation.

Bottom line: Lower lactate levels and more effective clearance of lactate in patients following cardiac arrest are associated with improved survival and good neurologic outcome.

Citation: Donnino MW, Andersen LW, Giberson T, et al. Initial lactate and lactate change in post-cardiac arrest: a multicenter validation study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(8):1804-1811.

Clinical question: Is greater lactate clearance following resuscitation from cardiac arrest associated with lower mortality and better neurologic outcomes?

Background: Recommendations from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation for monitoring serial lactate levels in post-resuscitation patients are based primarily on extrapolation from other conditions such as sepsis. Two single-retrospective analyses found effective lactate clearance was associated with decreased mortality. This association had not previously been validated in a multicenter, prospective study.

Study design: Multicenter, prospective, observational study.

Setting: Four urban, tertiary-care teaching hospitals.

Synopsis: Absolute lactate levels and the differences in the percent lactate change over 24 hours were compared in 100 patients who suffered out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Ninety-seven percent received therapeutic hypothermia, and overall survival was 46%. Survivors and patients with a good neurologic outcome had lower lactate levels at zero hours (4.1 vs. 7.3), 12 hours (2.2 vs. 6.0), and 24 hours (1.6 vs. 4.4) compared with nonsurvivors and patients with bad neurologic outcomes.

The percent lactate decreased was greater in survivors and in those with good neurologic outcomes (odds ratio, 2.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.1–4.4).

Nonsurvivors or those with poor neurologic outcomes were less likely to have received bystander CPR, to have suffered a witnessed arrest, or to have had a shockable rhythm at presentation. Superior lactate clearance in survivors and those with good neurologic outcomes suggests a potential role in developing markers of effective resuscitation.

Bottom line: Lower lactate levels and more effective clearance of lactate in patients following cardiac arrest are associated with improved survival and good neurologic outcome.

Citation: Donnino MW, Andersen LW, Giberson T, et al. Initial lactate and lactate change in post-cardiac arrest: a multicenter validation study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(8):1804-1811.

Time to Meds Matters for Patients with Cardiac Arrest Due to Nonshockable Rhythms

Clinical question: Is earlier administration of epinephrine in patients with cardiac arrest due to nonshockable rhythms associated with increased return of spontaneous circulation, survival, and neurologically intact survival?

Background: About 200,000 hospitalized patients in the U.S. have a cardiac arrest, commonly due to nonshockable rhythms. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation has been the only efficacious intervention. There are no well-controlled trials of the use of epinephrine on survival and neurological outcomes.

Study design: Prospective cohort from a large multicenter registry of in-hospital cardiac arrests.

Setting: Data from 570 hospitals from 2000 to 2009.

Synopsis: Authors included 25,095 adults from 570 hospitals who had cardiac arrests in hospital with asystole or pulseless electrical activity as the initial rhythm. Time to first administration of epinephrine was recorded and then separated into quartiles, and odds ratios were evaluated using one to three minutes as the reference group. Outcomes of survival to hospital discharge (10%), return of spontaneous circulation (47%), and survival to hospital discharge with favorable neurologic status (7%) were assessed.

Survival to discharge decreased as the time to administration of the first dose of epinephrine increased. Of those patients receiving epinephrine in one minute, 12% survived. This dropped to 7% for those first receiving epinephrine after seven minutes. Return of spontaneous circulation and survival to discharge with favorable neurologic status showed a similar stepwise decrease with longer times to first administration of epinephrine.

Bottom line: Earlier administration of epinephrine to patients with cardiac arrest due to nonshockable rhythms is associated with improved survival to discharge, return of spontaneous circulation, and neurologically intact survival.

Citation: Donnino MW, Salciccioli JD, Howell MD, et al. Time to administration of epinephrine and outcome after in-hospital cardiac arrest with non-shockable rhythms: restrospective analysis of large in-hospital data registry. BMJ. 2014;348:g3028.

Clinical question: Is earlier administration of epinephrine in patients with cardiac arrest due to nonshockable rhythms associated with increased return of spontaneous circulation, survival, and neurologically intact survival?

Background: About 200,000 hospitalized patients in the U.S. have a cardiac arrest, commonly due to nonshockable rhythms. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation has been the only efficacious intervention. There are no well-controlled trials of the use of epinephrine on survival and neurological outcomes.

Study design: Prospective cohort from a large multicenter registry of in-hospital cardiac arrests.

Setting: Data from 570 hospitals from 2000 to 2009.

Synopsis: Authors included 25,095 adults from 570 hospitals who had cardiac arrests in hospital with asystole or pulseless electrical activity as the initial rhythm. Time to first administration of epinephrine was recorded and then separated into quartiles, and odds ratios were evaluated using one to three minutes as the reference group. Outcomes of survival to hospital discharge (10%), return of spontaneous circulation (47%), and survival to hospital discharge with favorable neurologic status (7%) were assessed.

Survival to discharge decreased as the time to administration of the first dose of epinephrine increased. Of those patients receiving epinephrine in one minute, 12% survived. This dropped to 7% for those first receiving epinephrine after seven minutes. Return of spontaneous circulation and survival to discharge with favorable neurologic status showed a similar stepwise decrease with longer times to first administration of epinephrine.

Bottom line: Earlier administration of epinephrine to patients with cardiac arrest due to nonshockable rhythms is associated with improved survival to discharge, return of spontaneous circulation, and neurologically intact survival.

Citation: Donnino MW, Salciccioli JD, Howell MD, et al. Time to administration of epinephrine and outcome after in-hospital cardiac arrest with non-shockable rhythms: restrospective analysis of large in-hospital data registry. BMJ. 2014;348:g3028.

Clinical question: Is earlier administration of epinephrine in patients with cardiac arrest due to nonshockable rhythms associated with increased return of spontaneous circulation, survival, and neurologically intact survival?

Background: About 200,000 hospitalized patients in the U.S. have a cardiac arrest, commonly due to nonshockable rhythms. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation has been the only efficacious intervention. There are no well-controlled trials of the use of epinephrine on survival and neurological outcomes.

Study design: Prospective cohort from a large multicenter registry of in-hospital cardiac arrests.

Setting: Data from 570 hospitals from 2000 to 2009.

Synopsis: Authors included 25,095 adults from 570 hospitals who had cardiac arrests in hospital with asystole or pulseless electrical activity as the initial rhythm. Time to first administration of epinephrine was recorded and then separated into quartiles, and odds ratios were evaluated using one to three minutes as the reference group. Outcomes of survival to hospital discharge (10%), return of spontaneous circulation (47%), and survival to hospital discharge with favorable neurologic status (7%) were assessed.

Survival to discharge decreased as the time to administration of the first dose of epinephrine increased. Of those patients receiving epinephrine in one minute, 12% survived. This dropped to 7% for those first receiving epinephrine after seven minutes. Return of spontaneous circulation and survival to discharge with favorable neurologic status showed a similar stepwise decrease with longer times to first administration of epinephrine.

Bottom line: Earlier administration of epinephrine to patients with cardiac arrest due to nonshockable rhythms is associated with improved survival to discharge, return of spontaneous circulation, and neurologically intact survival.

Citation: Donnino MW, Salciccioli JD, Howell MD, et al. Time to administration of epinephrine and outcome after in-hospital cardiac arrest with non-shockable rhythms: restrospective analysis of large in-hospital data registry. BMJ. 2014;348:g3028.

Frailty Indices Tool Predicts Post-Operative Complications, Mortality after Elective Surgery in Geriatric Patients

Clinical question: Is there a more accurate way to predict adverse post-operative outcomes in geriatric patients undergoing elective surgery?

Background: More than half of all operations in the U.S. involve geriatric patients. Most tools hospitalists use to predict post-operative outcomes are focused on cardiovascular events and do not account for frailty. Common in geriatric patients, frailty is thought to influence post-operative outcomes.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: A 1,000-bed academic hospital in Seoul, South Korea.

Synopsis: A cohort of 275 elderly patients (>64 years old) who were scheduled for elective intermediate or high-risk surgery underwent a pre-operative comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) that included measures of frailty. This cohort was then followed for mortality, major post-operative complications (pneumonia, urinary infection, pulmonary embolism, and unplanned transfer to intensive care), length of stay, and transfer to a nursing home. Post-operative complications, transfer to a nursing facility, and one-year mortality were associated with a derived scoring tool that included the Charlson Comorbidity Index, activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), dementia, risk for delirium, mid-arm circumference, and a mini-nutritional assessment.

This tool was more accurate at predicting one-year mortality than the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification.

Bottom line: This study establishes that measures of frailty predict post-operative outcomes in geriatric patients undergoing elective surgery; however, the authors’ tool depends on CGA, which is time-consuming, cumbersome, and depends on indices not familiar to many hospitalists.

Citation: Kim SW, Han HS, Jung HW, et al. Multidimensional frailty scores for the prediction of postoperative mortality risk. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(7):633-640.

Clinical question: Is there a more accurate way to predict adverse post-operative outcomes in geriatric patients undergoing elective surgery?

Background: More than half of all operations in the U.S. involve geriatric patients. Most tools hospitalists use to predict post-operative outcomes are focused on cardiovascular events and do not account for frailty. Common in geriatric patients, frailty is thought to influence post-operative outcomes.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: A 1,000-bed academic hospital in Seoul, South Korea.