User login

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM's "Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program" course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

How to Use Hospitalist Productivity, Compensation Survey Data

The 2014 State of Hospital Medicine report (SOHM), published by SHM in the fall of even years, is unquestionably the most robust and informative data available to understand the hospitalist workforce marketplace. And if you are the person who returned a completed survey for your practice, you get a free copy of the report mailed to you.

Keep in mind that the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) surveys and reports data on hospitalist productivity and compensation every year. And the data acquired by MGMA in even years is simply folded into the SOHM, along with a ton of additional information added by a separate SHM survey, including things like the amount of financial support provided to hospitalist groups by hospitals (now up to a median of $156, 063 per full-time equivalent, or FTE).

I’ve written previously about some of the ways that the data reported in both of these surveys can be tricky to interpret (September 2013 and October 2013), and in this column I’ll go a little deeper into how to use the data reported on number of shifts worked and productivity.

A Common Question

Assume that, to address a staffing shortage or simply as a way to boost their income, some of the doctors in your group are willing to work more shifts than required for full-time status. And, in your group, some portion of a doctor’s compensation is a function of their individual work relevant value unit (wRVU) productivity—for example, a bonus for wRVUs above a certain threshold. You want to know whether the wRVU productivity generated by a doctor on their extra shifts should factor into compensation the same way it does for “regular” shifts.

You might turn to the MGMA and SOHM surveys to see how other groups handle this issue. But here is where it gets tricky.

First, you need to realize that the MGMA surveys, and similar ones from the American Medical Group Association and others, report wRVUs and compensation per physician, not per FTE. So wRVUs generated by these doctors on extra shifts are included, and you can’t tell from the aggregate data what portion of wRVUs came from regular shifts and what portion came from extra shifts.

And it is critical to keep in mind that any doctor who works at least 0.8 FTE as defined by that particular practice is reported as full time. Those working 79% or less of full time are counted by MGMA as part time.

To summarize: The MGMA and similar surveys don’t provide data on wRVU productivity per FTE, even though in most cases that is how everyone describes the data. Instead, the surveys provide data per individual doctor, many of whom work more or less than 1.0 FTE. So, despite the fact that most people, including me, tend to quote data from the surveys as though it is per FTE, as in “The 2014 MGMA data shows median hospitalist compensation is $253,977 per FTE,” we should say “per doctor” instead.

Theoretically, doctors working slightly less than 1.0 FTE should offset the doctors working slightly more than 1.0 FTE. But, while I think that’s a reasonable assumption for most specialties, such a significant portion of hospitalist groups have had chronic staffing shortages that a lot of hospitalists across the country are working extra shifts, probably more than are working between 0.8 and 1.0 FTE. So the hospitalist survey wRVU data is probably at least a little higher than it would be if it were reported per FTE.

Unfortunately, there is no way to confirm my suspicion, because MGMA doesn’t allow any individual doctor to be reported as more than 1.0 FTE, even if he works far more shifts than the number that defines full time for that practice. In other words, extra shifts just aren’t accounted for in the MGMA survey.

Implications of Individual vs. FTE

For most purposes, it probably doesn’t make any difference if you are erroneously thinking about the compensation and productivity survey numbers on a per FTE basis. But, for some purposes, and for those who work significantly more shifts than most hospitalists, it can start to matter.

Now back to the original question. You’re thinking about whether wRVUs generated by the doctors in your group on extra shifts should count toward the wRVU bonus just like those generated on regular shifts. You’d like to handle this the same way as other groups, but, unfortunately, survey data just isn’t helpful here. You’ll have to decide this for yourself.

I think some, but probably not all, extra shift productivity should count toward your wRVU bonus. You might, for example, say that productivity for somewhere between three or five extra shifts per quarter—that’s totally arbitrary, and of course this would be a negotiation between you and hospital leadership—should count toward the productivity target, and the rest wouldn’t, or that those extra shifts above an agreed-upon number would result in an increase in the wRVU target. The biggest problem with this is that it would be a nightmare to administer—essentially impossible for many practices. But you could accomplish the same thing by including the first few shifts per quarter in the “base” FTE calculation and then, after that, adjusting each person’s FTE value up as they work more shifts.

One more thing about productivity targets…

It’s also important to remember that productivity targets make the most sense at the group—not the individual—level. The MGMA data includes hospitalists who work night shifts (including nocturnists) and doctors who work low-production shifts (i.e., pager or ED triage shifts), as well as daytime rounding doctors. So, if you have a doctor who only works days, you would expect him to generate wRVUs in excess of the global target of wRVUs per FTE to make up for the low-productivity shifts that other doctors have to work.

For example, your practice might decide the group as a whole is expected to generate the MGMA yearly median 4,298 wRVUs per doctor, multiplied by the number of FTEs in the group. But the nocturnists would be expected to generate fewer, while those who work most or all of their shifts in a daytime rounder would be expected to generate more. So the threshold to begin paying the wRVU bonus for daytime rounding doctors might be adjusted up to something like 4,500 wRVUs.

The above example is just as an illustration, of course, and there are all kinds of reasons it might be more appropriate to choose different thresholds for your practice. But it’s a good place to start the thinking.

The 2014 State of Hospital Medicine report (SOHM), published by SHM in the fall of even years, is unquestionably the most robust and informative data available to understand the hospitalist workforce marketplace. And if you are the person who returned a completed survey for your practice, you get a free copy of the report mailed to you.

Keep in mind that the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) surveys and reports data on hospitalist productivity and compensation every year. And the data acquired by MGMA in even years is simply folded into the SOHM, along with a ton of additional information added by a separate SHM survey, including things like the amount of financial support provided to hospitalist groups by hospitals (now up to a median of $156, 063 per full-time equivalent, or FTE).

I’ve written previously about some of the ways that the data reported in both of these surveys can be tricky to interpret (September 2013 and October 2013), and in this column I’ll go a little deeper into how to use the data reported on number of shifts worked and productivity.

A Common Question

Assume that, to address a staffing shortage or simply as a way to boost their income, some of the doctors in your group are willing to work more shifts than required for full-time status. And, in your group, some portion of a doctor’s compensation is a function of their individual work relevant value unit (wRVU) productivity—for example, a bonus for wRVUs above a certain threshold. You want to know whether the wRVU productivity generated by a doctor on their extra shifts should factor into compensation the same way it does for “regular” shifts.

You might turn to the MGMA and SOHM surveys to see how other groups handle this issue. But here is where it gets tricky.

First, you need to realize that the MGMA surveys, and similar ones from the American Medical Group Association and others, report wRVUs and compensation per physician, not per FTE. So wRVUs generated by these doctors on extra shifts are included, and you can’t tell from the aggregate data what portion of wRVUs came from regular shifts and what portion came from extra shifts.

And it is critical to keep in mind that any doctor who works at least 0.8 FTE as defined by that particular practice is reported as full time. Those working 79% or less of full time are counted by MGMA as part time.

To summarize: The MGMA and similar surveys don’t provide data on wRVU productivity per FTE, even though in most cases that is how everyone describes the data. Instead, the surveys provide data per individual doctor, many of whom work more or less than 1.0 FTE. So, despite the fact that most people, including me, tend to quote data from the surveys as though it is per FTE, as in “The 2014 MGMA data shows median hospitalist compensation is $253,977 per FTE,” we should say “per doctor” instead.

Theoretically, doctors working slightly less than 1.0 FTE should offset the doctors working slightly more than 1.0 FTE. But, while I think that’s a reasonable assumption for most specialties, such a significant portion of hospitalist groups have had chronic staffing shortages that a lot of hospitalists across the country are working extra shifts, probably more than are working between 0.8 and 1.0 FTE. So the hospitalist survey wRVU data is probably at least a little higher than it would be if it were reported per FTE.

Unfortunately, there is no way to confirm my suspicion, because MGMA doesn’t allow any individual doctor to be reported as more than 1.0 FTE, even if he works far more shifts than the number that defines full time for that practice. In other words, extra shifts just aren’t accounted for in the MGMA survey.

Implications of Individual vs. FTE

For most purposes, it probably doesn’t make any difference if you are erroneously thinking about the compensation and productivity survey numbers on a per FTE basis. But, for some purposes, and for those who work significantly more shifts than most hospitalists, it can start to matter.

Now back to the original question. You’re thinking about whether wRVUs generated by the doctors in your group on extra shifts should count toward the wRVU bonus just like those generated on regular shifts. You’d like to handle this the same way as other groups, but, unfortunately, survey data just isn’t helpful here. You’ll have to decide this for yourself.

I think some, but probably not all, extra shift productivity should count toward your wRVU bonus. You might, for example, say that productivity for somewhere between three or five extra shifts per quarter—that’s totally arbitrary, and of course this would be a negotiation between you and hospital leadership—should count toward the productivity target, and the rest wouldn’t, or that those extra shifts above an agreed-upon number would result in an increase in the wRVU target. The biggest problem with this is that it would be a nightmare to administer—essentially impossible for many practices. But you could accomplish the same thing by including the first few shifts per quarter in the “base” FTE calculation and then, after that, adjusting each person’s FTE value up as they work more shifts.

One more thing about productivity targets…

It’s also important to remember that productivity targets make the most sense at the group—not the individual—level. The MGMA data includes hospitalists who work night shifts (including nocturnists) and doctors who work low-production shifts (i.e., pager or ED triage shifts), as well as daytime rounding doctors. So, if you have a doctor who only works days, you would expect him to generate wRVUs in excess of the global target of wRVUs per FTE to make up for the low-productivity shifts that other doctors have to work.

For example, your practice might decide the group as a whole is expected to generate the MGMA yearly median 4,298 wRVUs per doctor, multiplied by the number of FTEs in the group. But the nocturnists would be expected to generate fewer, while those who work most or all of their shifts in a daytime rounder would be expected to generate more. So the threshold to begin paying the wRVU bonus for daytime rounding doctors might be adjusted up to something like 4,500 wRVUs.

The above example is just as an illustration, of course, and there are all kinds of reasons it might be more appropriate to choose different thresholds for your practice. But it’s a good place to start the thinking.

The 2014 State of Hospital Medicine report (SOHM), published by SHM in the fall of even years, is unquestionably the most robust and informative data available to understand the hospitalist workforce marketplace. And if you are the person who returned a completed survey for your practice, you get a free copy of the report mailed to you.

Keep in mind that the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) surveys and reports data on hospitalist productivity and compensation every year. And the data acquired by MGMA in even years is simply folded into the SOHM, along with a ton of additional information added by a separate SHM survey, including things like the amount of financial support provided to hospitalist groups by hospitals (now up to a median of $156, 063 per full-time equivalent, or FTE).

I’ve written previously about some of the ways that the data reported in both of these surveys can be tricky to interpret (September 2013 and October 2013), and in this column I’ll go a little deeper into how to use the data reported on number of shifts worked and productivity.

A Common Question

Assume that, to address a staffing shortage or simply as a way to boost their income, some of the doctors in your group are willing to work more shifts than required for full-time status. And, in your group, some portion of a doctor’s compensation is a function of their individual work relevant value unit (wRVU) productivity—for example, a bonus for wRVUs above a certain threshold. You want to know whether the wRVU productivity generated by a doctor on their extra shifts should factor into compensation the same way it does for “regular” shifts.

You might turn to the MGMA and SOHM surveys to see how other groups handle this issue. But here is where it gets tricky.

First, you need to realize that the MGMA surveys, and similar ones from the American Medical Group Association and others, report wRVUs and compensation per physician, not per FTE. So wRVUs generated by these doctors on extra shifts are included, and you can’t tell from the aggregate data what portion of wRVUs came from regular shifts and what portion came from extra shifts.

And it is critical to keep in mind that any doctor who works at least 0.8 FTE as defined by that particular practice is reported as full time. Those working 79% or less of full time are counted by MGMA as part time.

To summarize: The MGMA and similar surveys don’t provide data on wRVU productivity per FTE, even though in most cases that is how everyone describes the data. Instead, the surveys provide data per individual doctor, many of whom work more or less than 1.0 FTE. So, despite the fact that most people, including me, tend to quote data from the surveys as though it is per FTE, as in “The 2014 MGMA data shows median hospitalist compensation is $253,977 per FTE,” we should say “per doctor” instead.

Theoretically, doctors working slightly less than 1.0 FTE should offset the doctors working slightly more than 1.0 FTE. But, while I think that’s a reasonable assumption for most specialties, such a significant portion of hospitalist groups have had chronic staffing shortages that a lot of hospitalists across the country are working extra shifts, probably more than are working between 0.8 and 1.0 FTE. So the hospitalist survey wRVU data is probably at least a little higher than it would be if it were reported per FTE.

Unfortunately, there is no way to confirm my suspicion, because MGMA doesn’t allow any individual doctor to be reported as more than 1.0 FTE, even if he works far more shifts than the number that defines full time for that practice. In other words, extra shifts just aren’t accounted for in the MGMA survey.

Implications of Individual vs. FTE

For most purposes, it probably doesn’t make any difference if you are erroneously thinking about the compensation and productivity survey numbers on a per FTE basis. But, for some purposes, and for those who work significantly more shifts than most hospitalists, it can start to matter.

Now back to the original question. You’re thinking about whether wRVUs generated by the doctors in your group on extra shifts should count toward the wRVU bonus just like those generated on regular shifts. You’d like to handle this the same way as other groups, but, unfortunately, survey data just isn’t helpful here. You’ll have to decide this for yourself.

I think some, but probably not all, extra shift productivity should count toward your wRVU bonus. You might, for example, say that productivity for somewhere between three or five extra shifts per quarter—that’s totally arbitrary, and of course this would be a negotiation between you and hospital leadership—should count toward the productivity target, and the rest wouldn’t, or that those extra shifts above an agreed-upon number would result in an increase in the wRVU target. The biggest problem with this is that it would be a nightmare to administer—essentially impossible for many practices. But you could accomplish the same thing by including the first few shifts per quarter in the “base” FTE calculation and then, after that, adjusting each person’s FTE value up as they work more shifts.

One more thing about productivity targets…

It’s also important to remember that productivity targets make the most sense at the group—not the individual—level. The MGMA data includes hospitalists who work night shifts (including nocturnists) and doctors who work low-production shifts (i.e., pager or ED triage shifts), as well as daytime rounding doctors. So, if you have a doctor who only works days, you would expect him to generate wRVUs in excess of the global target of wRVUs per FTE to make up for the low-productivity shifts that other doctors have to work.

For example, your practice might decide the group as a whole is expected to generate the MGMA yearly median 4,298 wRVUs per doctor, multiplied by the number of FTEs in the group. But the nocturnists would be expected to generate fewer, while those who work most or all of their shifts in a daytime rounder would be expected to generate more. So the threshold to begin paying the wRVU bonus for daytime rounding doctors might be adjusted up to something like 4,500 wRVUs.

The above example is just as an illustration, of course, and there are all kinds of reasons it might be more appropriate to choose different thresholds for your practice. But it’s a good place to start the thinking.

Hospitals' Observation Status Designation May Trigger Malpractice Claims

I’m convinced that observation status is rapidly becoming a meaningful factor in patients’ decision to file a malpractice lawsuit.

First, let me concede that I don’t know of any hard data to support my claim. I even asked the nation’s largest malpractice insurer about this, and they didn’t have any data on it. I think that is because observation status has only become a really big issue in the last couple of years, and since it typically takes several years for a malpractice suit to conclude, it just hasn’t found its way onto their radar yet.

But I’m pretty sure that will change within the next few years.

Implications

As any seasoned practitioner in our field knows, all outpatient and inpatient physician charges for Medicare patients, along with those of other licensed practitioners, are billed through Medicare Part B. After meeting a deductible, patients with traditional fee-for-service Medicare are generally responsible for 20% of all approved Part B charges, with no upper limit. For patients seen by a large number of providers while hospitalized, this 20% can really add up. Some patients have a secondary insurance that pays for this.

Hospital charges for patients on inpatient status are billed through Medicare Part A. Patients have an annual Part A deductible, and only in the case of very long inpatient stays will they have to pay more than that for inpatient care each year.

But hospital charges for patients on observation status are billed through Part B. And because hospital charges add up so quickly, the 20% of this that the patient is responsible for can be a lot of money—thousands of dollars, even for stays of less than 24 hours. Understandably, patients are not at all happy about this.

Let’s say you’re admitted overnight on observation status and your doctor orders your usual Advair inhaler. You use it once. Most hospitals aren’t able to ensure compliance with regulations around dispensing medications for home use like a pharmacy, so they won’t let you take the inhaler home. A few weeks later you’re stunned to learn that the hospital charged $10,000 for all services provided, and you’re responsible for 20% of the allowable amount PLUS the cost of all “self administered” drugs, like inhalers, eye drops, and calcitonin nasal spray. You look over your bill to see that you’re asked to pay $350 for the inhaler you used once and couldn’t even take home with you! Many self-administered medications, including eye drops and calcitonin nasal spray, result in similarly alarming charges to patients.

On top of the unpleasant surprise of a large hospital bill, Medicare won’t pay for skilled nursing facility (SNF) care for patients who are on observation status. That is, observation is not a “qualifying” stay for beneficiaries to access their SNF benefit.

It is easy to see why patients are unhappy about observation status.

The Media Message

News media are making the public aware of the potentially high financial costs they face if placed on observation status. But, too often, they oversimplify the issue, making it seem as though the choice of observation vs. inpatient status is entirely up to the treating doctor.

Saying that this decision is entirely up to the doctor is a lot like saying it is entirely up to you to determine how fast you drive on a freeway. In a sense that is correct, because no one else is in your car to control how fast you go and, in theory, you could choose to go 100 mph or 30 mph. The only problem is that it wouldn’t be long before you’d be in trouble with the law. So you don’t have complete autonomy to choose your speed; you have to comply with the laws. The same is true for doctors choosing observation status. We must comply with regulations in choosing the status or face legal consequences like fines or accusations of fraud.

Most news stories, like this one from NBC news (www.nbcnews.com/video/nightly-news/54511352#54511352) in February, are generally accurate but leave out the important fact that hospitals and doctors have little autonomy to choose the status the patient prefers. Instead, media often simply encourage patients on observation status to argue for a change to inpatient status and “be persistent.” More and more often, patients and families are arguing with the treating doctor; in many cases, that is a hospitalist.

Complaints Surge

At the 2014 SHM annual meeting last spring in Las Vegas, I spoke with many hospitalists who said that, increasingly, they are targets of observation-status complaints. One hospitalist group recently had each doctor list his or her top three frustrations with work; difficult and stressful conversations about observation status topped the list.

Patient anger regarding observation status can turn a satisfied patient into an angry one. We all know that unhappy patients are the ones most likely to pursue malpractice lawsuits. While anger over observation status doesn’t equal medical malpractice, it can change a patient’s opinion of our care, which may in some cases result in a malpractice claim.

Solutions

Medicare is unlikely to do away with observation status, so the best way to prevent complaints is to ensure that all its implications are explained to patients and families, ideally before they’re put into the hospital (e.g., while still in the ED). I think it is best if this message is delivered by someone other than the treating doctor(s): For example, a case manager might handle the discussion. Of course, patients and families are often too overwhelmed in the ED to absorb this information, so the message may need to be repeated later.

Maybe everyone should tell observation patients, “We’re going to observe you” without using any form of the word “admission.” And having these patients stay in distinct observation units probably reduces misunderstandings and complaints compared to the common practice of mixing these patients in “regular” hospital floors housing those on inpatient status.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find research data to support this idea.

I bet some hospitals have even more elegant and effective ways to reduce misunderstandings and complaints around observation status. I’d love to hear from you if you know of any. E-mail me at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

I’m convinced that observation status is rapidly becoming a meaningful factor in patients’ decision to file a malpractice lawsuit.

First, let me concede that I don’t know of any hard data to support my claim. I even asked the nation’s largest malpractice insurer about this, and they didn’t have any data on it. I think that is because observation status has only become a really big issue in the last couple of years, and since it typically takes several years for a malpractice suit to conclude, it just hasn’t found its way onto their radar yet.

But I’m pretty sure that will change within the next few years.

Implications

As any seasoned practitioner in our field knows, all outpatient and inpatient physician charges for Medicare patients, along with those of other licensed practitioners, are billed through Medicare Part B. After meeting a deductible, patients with traditional fee-for-service Medicare are generally responsible for 20% of all approved Part B charges, with no upper limit. For patients seen by a large number of providers while hospitalized, this 20% can really add up. Some patients have a secondary insurance that pays for this.

Hospital charges for patients on inpatient status are billed through Medicare Part A. Patients have an annual Part A deductible, and only in the case of very long inpatient stays will they have to pay more than that for inpatient care each year.

But hospital charges for patients on observation status are billed through Part B. And because hospital charges add up so quickly, the 20% of this that the patient is responsible for can be a lot of money—thousands of dollars, even for stays of less than 24 hours. Understandably, patients are not at all happy about this.

Let’s say you’re admitted overnight on observation status and your doctor orders your usual Advair inhaler. You use it once. Most hospitals aren’t able to ensure compliance with regulations around dispensing medications for home use like a pharmacy, so they won’t let you take the inhaler home. A few weeks later you’re stunned to learn that the hospital charged $10,000 for all services provided, and you’re responsible for 20% of the allowable amount PLUS the cost of all “self administered” drugs, like inhalers, eye drops, and calcitonin nasal spray. You look over your bill to see that you’re asked to pay $350 for the inhaler you used once and couldn’t even take home with you! Many self-administered medications, including eye drops and calcitonin nasal spray, result in similarly alarming charges to patients.

On top of the unpleasant surprise of a large hospital bill, Medicare won’t pay for skilled nursing facility (SNF) care for patients who are on observation status. That is, observation is not a “qualifying” stay for beneficiaries to access their SNF benefit.

It is easy to see why patients are unhappy about observation status.

The Media Message

News media are making the public aware of the potentially high financial costs they face if placed on observation status. But, too often, they oversimplify the issue, making it seem as though the choice of observation vs. inpatient status is entirely up to the treating doctor.

Saying that this decision is entirely up to the doctor is a lot like saying it is entirely up to you to determine how fast you drive on a freeway. In a sense that is correct, because no one else is in your car to control how fast you go and, in theory, you could choose to go 100 mph or 30 mph. The only problem is that it wouldn’t be long before you’d be in trouble with the law. So you don’t have complete autonomy to choose your speed; you have to comply with the laws. The same is true for doctors choosing observation status. We must comply with regulations in choosing the status or face legal consequences like fines or accusations of fraud.

Most news stories, like this one from NBC news (www.nbcnews.com/video/nightly-news/54511352#54511352) in February, are generally accurate but leave out the important fact that hospitals and doctors have little autonomy to choose the status the patient prefers. Instead, media often simply encourage patients on observation status to argue for a change to inpatient status and “be persistent.” More and more often, patients and families are arguing with the treating doctor; in many cases, that is a hospitalist.

Complaints Surge

At the 2014 SHM annual meeting last spring in Las Vegas, I spoke with many hospitalists who said that, increasingly, they are targets of observation-status complaints. One hospitalist group recently had each doctor list his or her top three frustrations with work; difficult and stressful conversations about observation status topped the list.

Patient anger regarding observation status can turn a satisfied patient into an angry one. We all know that unhappy patients are the ones most likely to pursue malpractice lawsuits. While anger over observation status doesn’t equal medical malpractice, it can change a patient’s opinion of our care, which may in some cases result in a malpractice claim.

Solutions

Medicare is unlikely to do away with observation status, so the best way to prevent complaints is to ensure that all its implications are explained to patients and families, ideally before they’re put into the hospital (e.g., while still in the ED). I think it is best if this message is delivered by someone other than the treating doctor(s): For example, a case manager might handle the discussion. Of course, patients and families are often too overwhelmed in the ED to absorb this information, so the message may need to be repeated later.

Maybe everyone should tell observation patients, “We’re going to observe you” without using any form of the word “admission.” And having these patients stay in distinct observation units probably reduces misunderstandings and complaints compared to the common practice of mixing these patients in “regular” hospital floors housing those on inpatient status.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find research data to support this idea.

I bet some hospitals have even more elegant and effective ways to reduce misunderstandings and complaints around observation status. I’d love to hear from you if you know of any. E-mail me at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

I’m convinced that observation status is rapidly becoming a meaningful factor in patients’ decision to file a malpractice lawsuit.

First, let me concede that I don’t know of any hard data to support my claim. I even asked the nation’s largest malpractice insurer about this, and they didn’t have any data on it. I think that is because observation status has only become a really big issue in the last couple of years, and since it typically takes several years for a malpractice suit to conclude, it just hasn’t found its way onto their radar yet.

But I’m pretty sure that will change within the next few years.

Implications

As any seasoned practitioner in our field knows, all outpatient and inpatient physician charges for Medicare patients, along with those of other licensed practitioners, are billed through Medicare Part B. After meeting a deductible, patients with traditional fee-for-service Medicare are generally responsible for 20% of all approved Part B charges, with no upper limit. For patients seen by a large number of providers while hospitalized, this 20% can really add up. Some patients have a secondary insurance that pays for this.

Hospital charges for patients on inpatient status are billed through Medicare Part A. Patients have an annual Part A deductible, and only in the case of very long inpatient stays will they have to pay more than that for inpatient care each year.

But hospital charges for patients on observation status are billed through Part B. And because hospital charges add up so quickly, the 20% of this that the patient is responsible for can be a lot of money—thousands of dollars, even for stays of less than 24 hours. Understandably, patients are not at all happy about this.

Let’s say you’re admitted overnight on observation status and your doctor orders your usual Advair inhaler. You use it once. Most hospitals aren’t able to ensure compliance with regulations around dispensing medications for home use like a pharmacy, so they won’t let you take the inhaler home. A few weeks later you’re stunned to learn that the hospital charged $10,000 for all services provided, and you’re responsible for 20% of the allowable amount PLUS the cost of all “self administered” drugs, like inhalers, eye drops, and calcitonin nasal spray. You look over your bill to see that you’re asked to pay $350 for the inhaler you used once and couldn’t even take home with you! Many self-administered medications, including eye drops and calcitonin nasal spray, result in similarly alarming charges to patients.

On top of the unpleasant surprise of a large hospital bill, Medicare won’t pay for skilled nursing facility (SNF) care for patients who are on observation status. That is, observation is not a “qualifying” stay for beneficiaries to access their SNF benefit.

It is easy to see why patients are unhappy about observation status.

The Media Message

News media are making the public aware of the potentially high financial costs they face if placed on observation status. But, too often, they oversimplify the issue, making it seem as though the choice of observation vs. inpatient status is entirely up to the treating doctor.

Saying that this decision is entirely up to the doctor is a lot like saying it is entirely up to you to determine how fast you drive on a freeway. In a sense that is correct, because no one else is in your car to control how fast you go and, in theory, you could choose to go 100 mph or 30 mph. The only problem is that it wouldn’t be long before you’d be in trouble with the law. So you don’t have complete autonomy to choose your speed; you have to comply with the laws. The same is true for doctors choosing observation status. We must comply with regulations in choosing the status or face legal consequences like fines or accusations of fraud.

Most news stories, like this one from NBC news (www.nbcnews.com/video/nightly-news/54511352#54511352) in February, are generally accurate but leave out the important fact that hospitals and doctors have little autonomy to choose the status the patient prefers. Instead, media often simply encourage patients on observation status to argue for a change to inpatient status and “be persistent.” More and more often, patients and families are arguing with the treating doctor; in many cases, that is a hospitalist.

Complaints Surge

At the 2014 SHM annual meeting last spring in Las Vegas, I spoke with many hospitalists who said that, increasingly, they are targets of observation-status complaints. One hospitalist group recently had each doctor list his or her top three frustrations with work; difficult and stressful conversations about observation status topped the list.

Patient anger regarding observation status can turn a satisfied patient into an angry one. We all know that unhappy patients are the ones most likely to pursue malpractice lawsuits. While anger over observation status doesn’t equal medical malpractice, it can change a patient’s opinion of our care, which may in some cases result in a malpractice claim.

Solutions

Medicare is unlikely to do away with observation status, so the best way to prevent complaints is to ensure that all its implications are explained to patients and families, ideally before they’re put into the hospital (e.g., while still in the ED). I think it is best if this message is delivered by someone other than the treating doctor(s): For example, a case manager might handle the discussion. Of course, patients and families are often too overwhelmed in the ED to absorb this information, so the message may need to be repeated later.

Maybe everyone should tell observation patients, “We’re going to observe you” without using any form of the word “admission.” And having these patients stay in distinct observation units probably reduces misunderstandings and complaints compared to the common practice of mixing these patients in “regular” hospital floors housing those on inpatient status.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find research data to support this idea.

I bet some hospitals have even more elegant and effective ways to reduce misunderstandings and complaints around observation status. I’d love to hear from you if you know of any. E-mail me at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

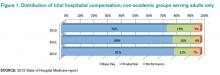

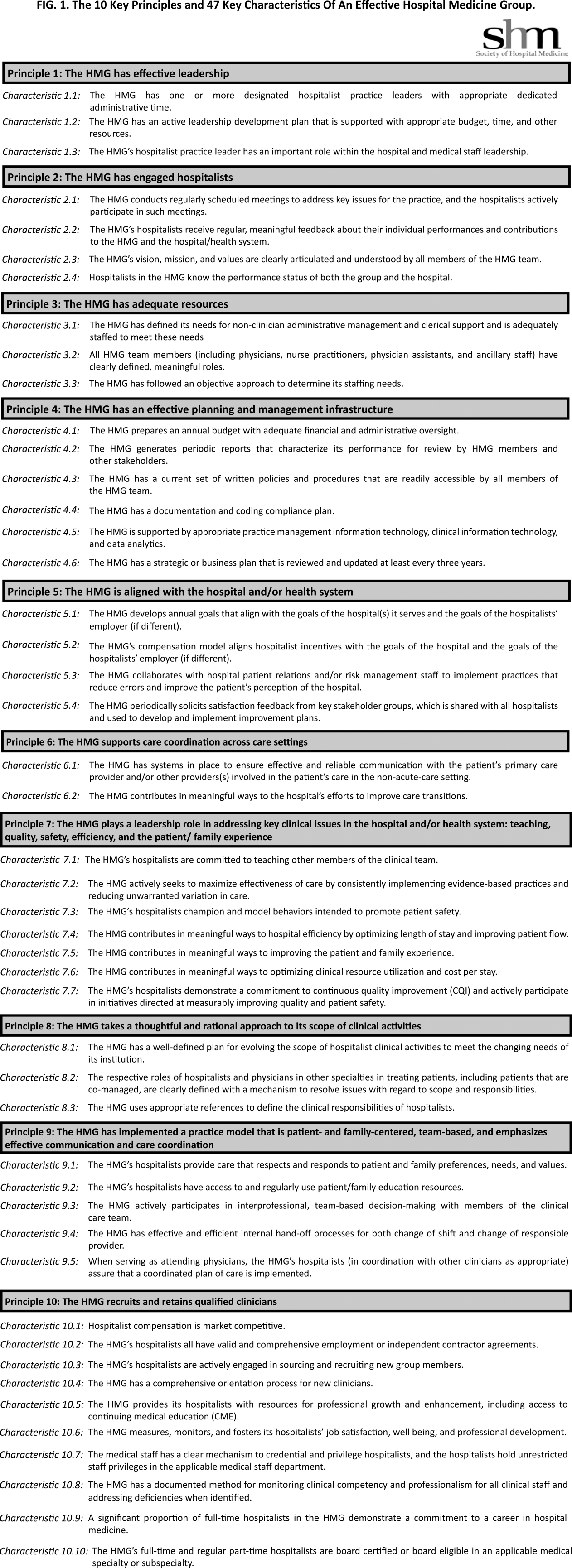

Put Key Principles, Characteristics of Effective Hospital Medicine Groups to Work

I hope you’re already familiar with “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: An Assessment Guide for Hospitals and Hospitalists” [www.hospitalmedicine.org/keychar] and have spent at least a few minutes reviewing the list of 10 “principles” and 47 “characteristics” thought to be associated with effective hospital medicine groups (HMGs). (Full disclosure: I was one of the authors of the article published in February 2014 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.) Most of us are very busy, so the temptation might be high to set the article aside and risk forgetting it. But I hope many in our field, both clinicians and administrators, will look at it more carefully. There are a number of ways you could use the guide to stimulate thinking or change in your practice.

Grading Our Specialty

I just returned from a meeting of about 10 hospitalist leaders from different organizations around the country. Attendees represented the diversity of our field, including hospital-employed HMGs, large hospitalist management companies, and academic programs. We spent a portion of the meeting discussing what grade we as a group would give the whole specialty of hospital medicine on each of the 10 “principles.” Essentially, we generated a report card for the U.S. hospitalist movement.

This wasn’t a rigorous scientific exercise; instead, it was a robust and thought-provoking discussion around what grade to assign. Opinions regarding the appropriate grade varied significantly, but a common theme was that our specialty really “owns” the importance of pursuing many or most of the principles listed in the article and is devoting time and resources to them even if many individual HMGs might have a long way to go to perform optimally.

For example, meeting attendees thought our field has for a long time worked diligently to “support care coordination across the care continuum” (Principle 6). No one thought that all HMGs do this optimally, but the consensus was that most HMGs have invested effort to do it well. And most were concerned that many HMGs still lack “adequate resources” (Principle 3) and sufficiently “engaged hospitalists” (Principle 2)—and that the former contributes to the latter.

The opinion of the hospitalist leaders who happened to attend the meeting where this conversation took place doesn’t represent the final word on how our specialty is performing, but I think all involved found value in having the conversation, hearing different perspectives about what we’re doing well and where we should focus energy and resources to improve.

Grading Your HM Group

You might want to do something similar within your own group, but make it more relevant by grading how your own practice performs on each of the 10 principles. You could do this on your own just to stimulate your thinking, or you could have each member of your HMG generate a report card of your group’s performance—then discuss where there is agreement or disagreement within the group.

You could structure this sort of individual or group assessment simply as an exercise to generate ideas and conversation about the practice, or your group could take a more formal approach and use it as part of a planning process to determine future practice management-related goals. I know of some groups that scheduled strategic planning meetings specifically to discuss which of the elements to make a priority.

Discussion Document for Leadership

In addition to using the article to generate conversation among hospitalists within your group, it can be a really valuable tool in guiding conversations with hospital leaders and the entity that employs the hospitalists. For example, you could use the article to generate or update the job description of the lead hospitalist or practice manager. Or during annual budgeting for the hospitalist practice, the guide could be used as a checklist to think about whether there are important areas that would benefit from more resources.

Of course, there is a risk that hospital leaders or those who employ the hospitalists could use the article primarily to criticize a hospitalist group and its leader for not already having excellent performance on every one of the principles and characteristics listed. That would be pretty unfortunate; there probably isn’t a single group that performs well on every domain, and the real value of the article is to “be aspirational, helping to raise the bar” for each HMG and our specialty as a whole.

And, as discussed in the article, an HMG doesn’t need to be a stellar performer on all 47 characteristics to be effective. Some of the characteristics listed in the article may not apply to all groups, so all involved in the management of any individual HMG should think about whether to set some aside when assessing their own group.

Where to Go from Here

The article is based on expert opinion, with the help of many more people than those listed as author, and I’m hopeful it will stimulate researchers to study some of these principles and characteristics. For many reasons, we will probably never have robust data, but I’d be happy for whatever we can get.

There is a pretty good chance that the evolution in the work we do and the nature of the hospital setting mean that the principles and characteristics may need to be revised periodically. I would love to know how they might be different in 10 or 20 years.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

I hope you’re already familiar with “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: An Assessment Guide for Hospitals and Hospitalists” [www.hospitalmedicine.org/keychar] and have spent at least a few minutes reviewing the list of 10 “principles” and 47 “characteristics” thought to be associated with effective hospital medicine groups (HMGs). (Full disclosure: I was one of the authors of the article published in February 2014 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.) Most of us are very busy, so the temptation might be high to set the article aside and risk forgetting it. But I hope many in our field, both clinicians and administrators, will look at it more carefully. There are a number of ways you could use the guide to stimulate thinking or change in your practice.

Grading Our Specialty

I just returned from a meeting of about 10 hospitalist leaders from different organizations around the country. Attendees represented the diversity of our field, including hospital-employed HMGs, large hospitalist management companies, and academic programs. We spent a portion of the meeting discussing what grade we as a group would give the whole specialty of hospital medicine on each of the 10 “principles.” Essentially, we generated a report card for the U.S. hospitalist movement.

This wasn’t a rigorous scientific exercise; instead, it was a robust and thought-provoking discussion around what grade to assign. Opinions regarding the appropriate grade varied significantly, but a common theme was that our specialty really “owns” the importance of pursuing many or most of the principles listed in the article and is devoting time and resources to them even if many individual HMGs might have a long way to go to perform optimally.

For example, meeting attendees thought our field has for a long time worked diligently to “support care coordination across the care continuum” (Principle 6). No one thought that all HMGs do this optimally, but the consensus was that most HMGs have invested effort to do it well. And most were concerned that many HMGs still lack “adequate resources” (Principle 3) and sufficiently “engaged hospitalists” (Principle 2)—and that the former contributes to the latter.

The opinion of the hospitalist leaders who happened to attend the meeting where this conversation took place doesn’t represent the final word on how our specialty is performing, but I think all involved found value in having the conversation, hearing different perspectives about what we’re doing well and where we should focus energy and resources to improve.

Grading Your HM Group

You might want to do something similar within your own group, but make it more relevant by grading how your own practice performs on each of the 10 principles. You could do this on your own just to stimulate your thinking, or you could have each member of your HMG generate a report card of your group’s performance—then discuss where there is agreement or disagreement within the group.

You could structure this sort of individual or group assessment simply as an exercise to generate ideas and conversation about the practice, or your group could take a more formal approach and use it as part of a planning process to determine future practice management-related goals. I know of some groups that scheduled strategic planning meetings specifically to discuss which of the elements to make a priority.

Discussion Document for Leadership

In addition to using the article to generate conversation among hospitalists within your group, it can be a really valuable tool in guiding conversations with hospital leaders and the entity that employs the hospitalists. For example, you could use the article to generate or update the job description of the lead hospitalist or practice manager. Or during annual budgeting for the hospitalist practice, the guide could be used as a checklist to think about whether there are important areas that would benefit from more resources.

Of course, there is a risk that hospital leaders or those who employ the hospitalists could use the article primarily to criticize a hospitalist group and its leader for not already having excellent performance on every one of the principles and characteristics listed. That would be pretty unfortunate; there probably isn’t a single group that performs well on every domain, and the real value of the article is to “be aspirational, helping to raise the bar” for each HMG and our specialty as a whole.

And, as discussed in the article, an HMG doesn’t need to be a stellar performer on all 47 characteristics to be effective. Some of the characteristics listed in the article may not apply to all groups, so all involved in the management of any individual HMG should think about whether to set some aside when assessing their own group.

Where to Go from Here

The article is based on expert opinion, with the help of many more people than those listed as author, and I’m hopeful it will stimulate researchers to study some of these principles and characteristics. For many reasons, we will probably never have robust data, but I’d be happy for whatever we can get.

There is a pretty good chance that the evolution in the work we do and the nature of the hospital setting mean that the principles and characteristics may need to be revised periodically. I would love to know how they might be different in 10 or 20 years.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

I hope you’re already familiar with “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: An Assessment Guide for Hospitals and Hospitalists” [www.hospitalmedicine.org/keychar] and have spent at least a few minutes reviewing the list of 10 “principles” and 47 “characteristics” thought to be associated with effective hospital medicine groups (HMGs). (Full disclosure: I was one of the authors of the article published in February 2014 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.) Most of us are very busy, so the temptation might be high to set the article aside and risk forgetting it. But I hope many in our field, both clinicians and administrators, will look at it more carefully. There are a number of ways you could use the guide to stimulate thinking or change in your practice.

Grading Our Specialty

I just returned from a meeting of about 10 hospitalist leaders from different organizations around the country. Attendees represented the diversity of our field, including hospital-employed HMGs, large hospitalist management companies, and academic programs. We spent a portion of the meeting discussing what grade we as a group would give the whole specialty of hospital medicine on each of the 10 “principles.” Essentially, we generated a report card for the U.S. hospitalist movement.

This wasn’t a rigorous scientific exercise; instead, it was a robust and thought-provoking discussion around what grade to assign. Opinions regarding the appropriate grade varied significantly, but a common theme was that our specialty really “owns” the importance of pursuing many or most of the principles listed in the article and is devoting time and resources to them even if many individual HMGs might have a long way to go to perform optimally.

For example, meeting attendees thought our field has for a long time worked diligently to “support care coordination across the care continuum” (Principle 6). No one thought that all HMGs do this optimally, but the consensus was that most HMGs have invested effort to do it well. And most were concerned that many HMGs still lack “adequate resources” (Principle 3) and sufficiently “engaged hospitalists” (Principle 2)—and that the former contributes to the latter.

The opinion of the hospitalist leaders who happened to attend the meeting where this conversation took place doesn’t represent the final word on how our specialty is performing, but I think all involved found value in having the conversation, hearing different perspectives about what we’re doing well and where we should focus energy and resources to improve.

Grading Your HM Group

You might want to do something similar within your own group, but make it more relevant by grading how your own practice performs on each of the 10 principles. You could do this on your own just to stimulate your thinking, or you could have each member of your HMG generate a report card of your group’s performance—then discuss where there is agreement or disagreement within the group.

You could structure this sort of individual or group assessment simply as an exercise to generate ideas and conversation about the practice, or your group could take a more formal approach and use it as part of a planning process to determine future practice management-related goals. I know of some groups that scheduled strategic planning meetings specifically to discuss which of the elements to make a priority.

Discussion Document for Leadership

In addition to using the article to generate conversation among hospitalists within your group, it can be a really valuable tool in guiding conversations with hospital leaders and the entity that employs the hospitalists. For example, you could use the article to generate or update the job description of the lead hospitalist or practice manager. Or during annual budgeting for the hospitalist practice, the guide could be used as a checklist to think about whether there are important areas that would benefit from more resources.

Of course, there is a risk that hospital leaders or those who employ the hospitalists could use the article primarily to criticize a hospitalist group and its leader for not already having excellent performance on every one of the principles and characteristics listed. That would be pretty unfortunate; there probably isn’t a single group that performs well on every domain, and the real value of the article is to “be aspirational, helping to raise the bar” for each HMG and our specialty as a whole.

And, as discussed in the article, an HMG doesn’t need to be a stellar performer on all 47 characteristics to be effective. Some of the characteristics listed in the article may not apply to all groups, so all involved in the management of any individual HMG should think about whether to set some aside when assessing their own group.

Where to Go from Here

The article is based on expert opinion, with the help of many more people than those listed as author, and I’m hopeful it will stimulate researchers to study some of these principles and characteristics. For many reasons, we will probably never have robust data, but I’d be happy for whatever we can get.

There is a pretty good chance that the evolution in the work we do and the nature of the hospital setting mean that the principles and characteristics may need to be revised periodically. I would love to know how they might be different in 10 or 20 years.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Proper Inpatient Documentation, Coding Essential to Avoid a Medicare Audit

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

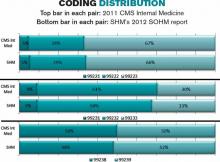

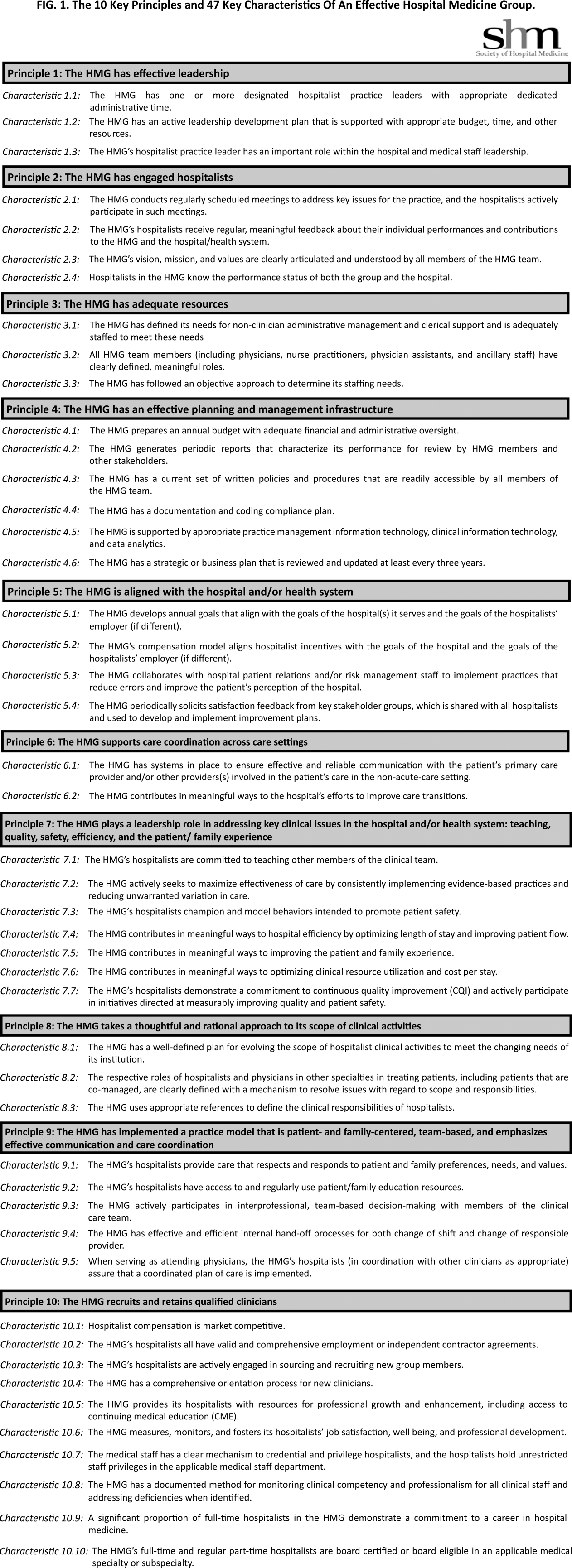

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Hospitalists Working Hard to Improve Patient Care

Dear Ms. Bernstein:

I’m writing this letter to let you know about some of the things happening in hospital medicine, to ensure we are always improving the care we provide.

While we talked on New Year’s Eve, you reluctantly told me that you and many of your friends were not happy with the move toward hospital care being provided by hospitalists, rather than the PCP you know. I didn’t respond because we were having a nice lunch and I didn’t want to distract you from praising my kids and talking about your grandbaby and her sibling on the way. So I thought I’d respond by writing this open letter to you on the chance it might also be thought provoking for some of my hospitalist colleagues.

I think your reluctance to share with me the unflattering opinion you and many of your friends have of the hospitalist model of care stemmed from a desire not to offend me rather than any uncertainty in your conclusion. It isn’t difficult to find others, both healthcare providers and consumers, who share your opinion.

As I’ve told you before, outside of my own parents, you and Mr. B. are among the people who had the most influence on my upbringing, and your opinion still matters to me. So I’m writing this hoping to change your view, at least a little.

Updated Numbers of Hospitalists

Our field is now larger than many other specialties, and we are experiencing ever-increasing pressure to “get it right.” A 2012 survey of hospitals conducted by the American Hospital Association found more than 38,000 doctors who identify themselves as hospitalists. This number has been increasing rapidly for more than a decade. The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) estimates that the number has grown to more than 44,000 in 2014, and that there are hospitalists in 72% of U.S. hospitals—90% at hospitals with over 200 beds. In 1996, there were fewer than 1,000 hospitalists.

The rapid growth in our field has brought challenges, and we’re lucky to have attracted many dedicated and talented people who are helping all of us make strides to do better, both by providing better technical care (e.g. ensuring careful assessments and ordering the best tests and treatments) and by doing so in a way that ensures patients and their families are highly satisfied.

Tools to Support Ongoing Improvements in Hospitalist Practice

There are many outlets hospitalists can turn to for education on essentially any aspect of their practice. Several years ago, the SHM published “The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development,” a publication that continues to be valuable in guiding hospitalists’ professional scope of clinical skills as well as educational curricula for training programs and continuing education. SHM and other organizations generate a great deal of educational content for hospitalists, which is available in many forms, including in-person conferences, webinars, and written materials. And there are several scientific journals that have significant content for hospitalists, including SHM’s own Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Our field encourages and recognizes ongoing commitment to hospitalists’ growth and development in a number of ways. When it is time for a doctor to renew his/her board certification, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) offers the option to pursue “Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine.” And SHM’s designation of Fellow, Senior Fellow and Master in Hospital Medicine recognizes those who have “demonstrated a commitment to hospital medicine, system change, and quality improvement principles.” Many in our field have achieved one or both of these distinctions, and countless others are pursuing them now.

Through its foundation, the ABIM developed a campaign known as “Choosing Wisely” to “promote conversations between physicians and patients by helping patients choose care that is: supported by evidence, not duplicative of other tests or procedures already received, free from harm, and truly necessary.” SHM joined in this effort by developing separate criteria for hospitalists who care for adults or children.

New Tool Encourages High Performance