User login

Advancing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Hospital Medicine

Studies continue to demonstrate persistent gaps in equity for women and underrepresented minorities (URMs)1 throughout nearly all aspects of academic medicine, including rank,2-4 tenure,5 authorship,6,7 funding opportunities,8,9 awards,10 speakership,11 leadership,12,13 and salaries.2,14,15

In this article, we report DEI efforts within our division, focusing on the development of our strategic plan and specific outcomes related to compensation, recruitment, and policies.

METHODS

Our Division’s Framework to DEI—“It Takes a Village”

Our Division of Hospital Medicine (DHM), previously within the Division of General Internal Medicine, was founded in October 2017. The DHM at the University of Colorado Hospital (UCH) is composed of 100 faculty members (70 physicians and 30 advanced-practice providers; 58% women and 42% men). In 2018, we implemented a stepwise approach to critically assess DEI within our group and to build a strategic plan to address the issues.

As a new division, we sought stakeholder feedback from division members. All faculty within the division were invited to attend a meeting in which issues related to DEI were discussed. A literature review that spanned both medical and nonmedical fields was also completed. Search terms included salary equity, gender equity, diverse teams, diversity recruitment and retention, diversifying leadership, and diverse speakers. Salaries, internally funded time, and other processes, such as recruitment, promotion, and hiring for leadership positions, were evaluated during the first year we became a division.

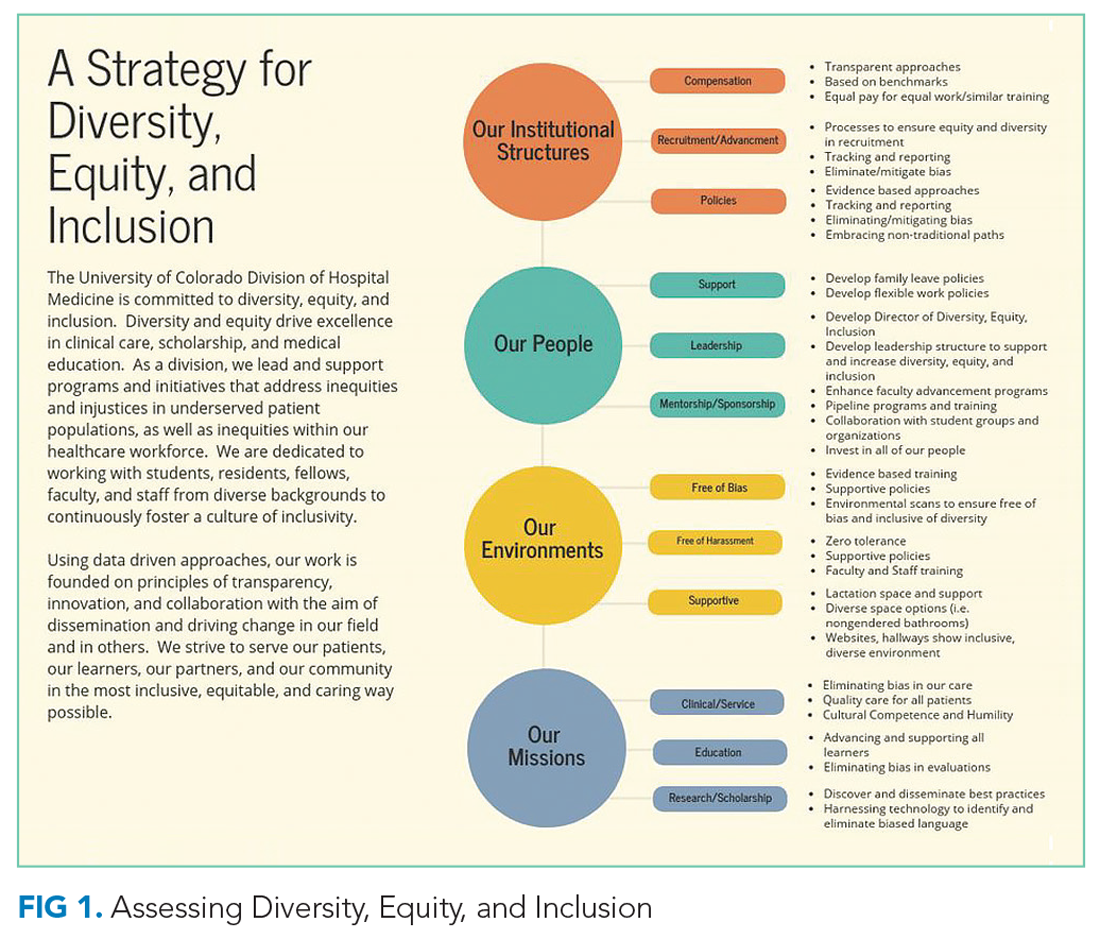

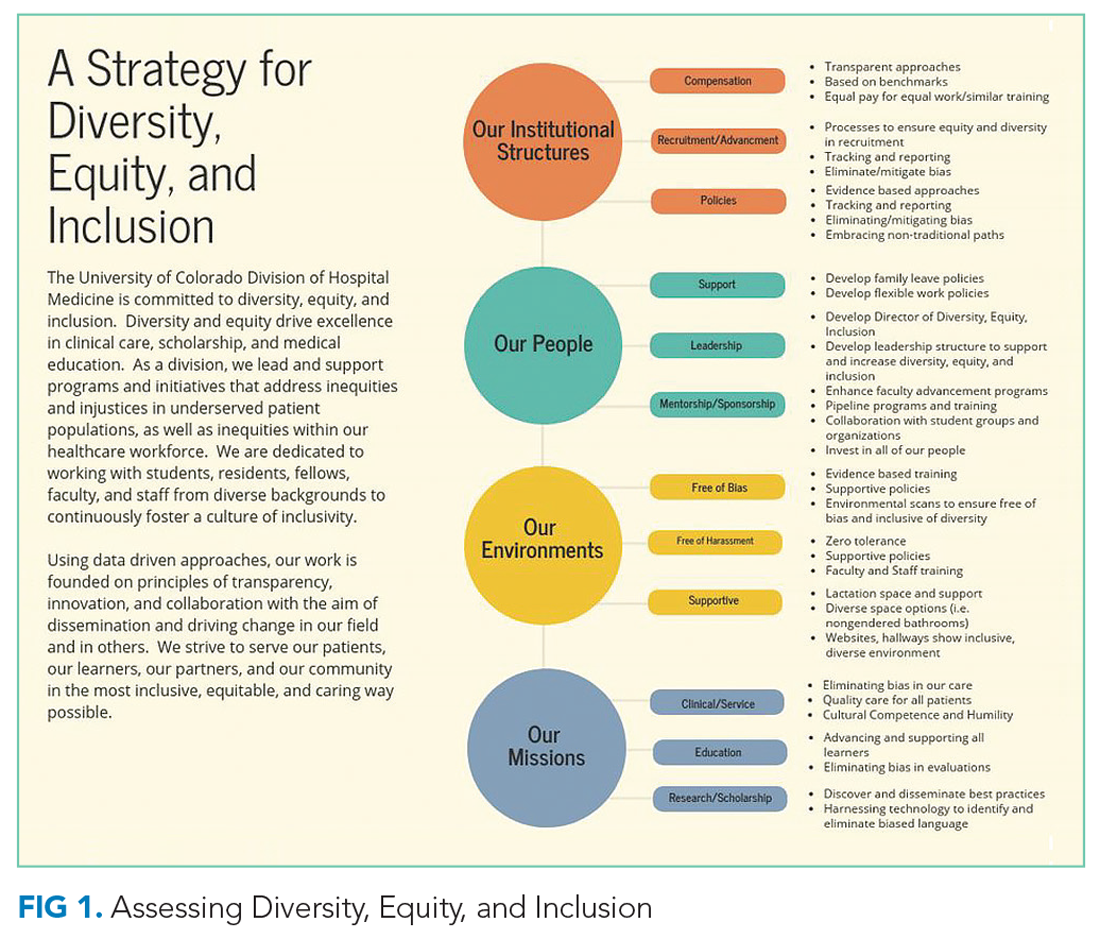

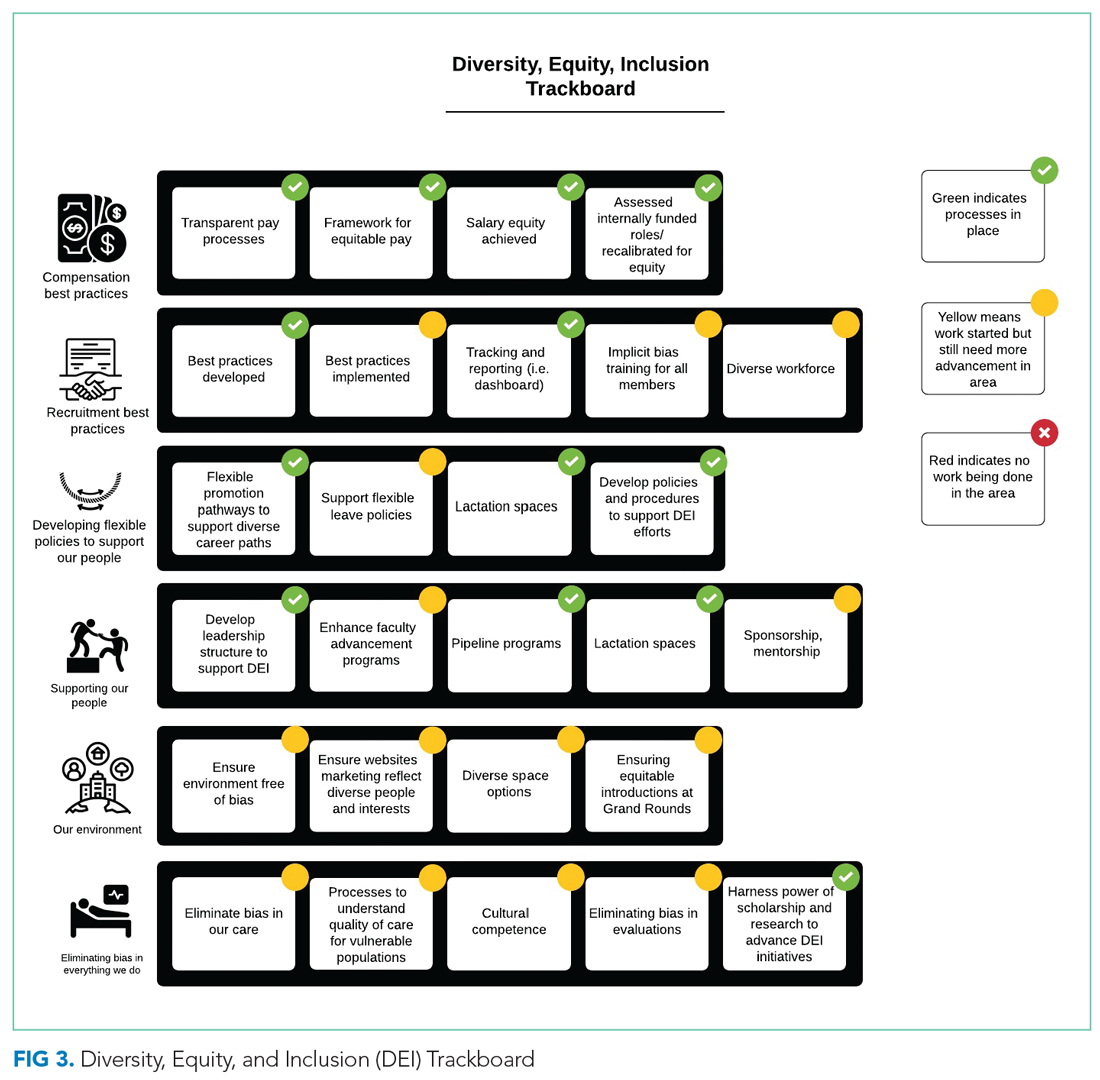

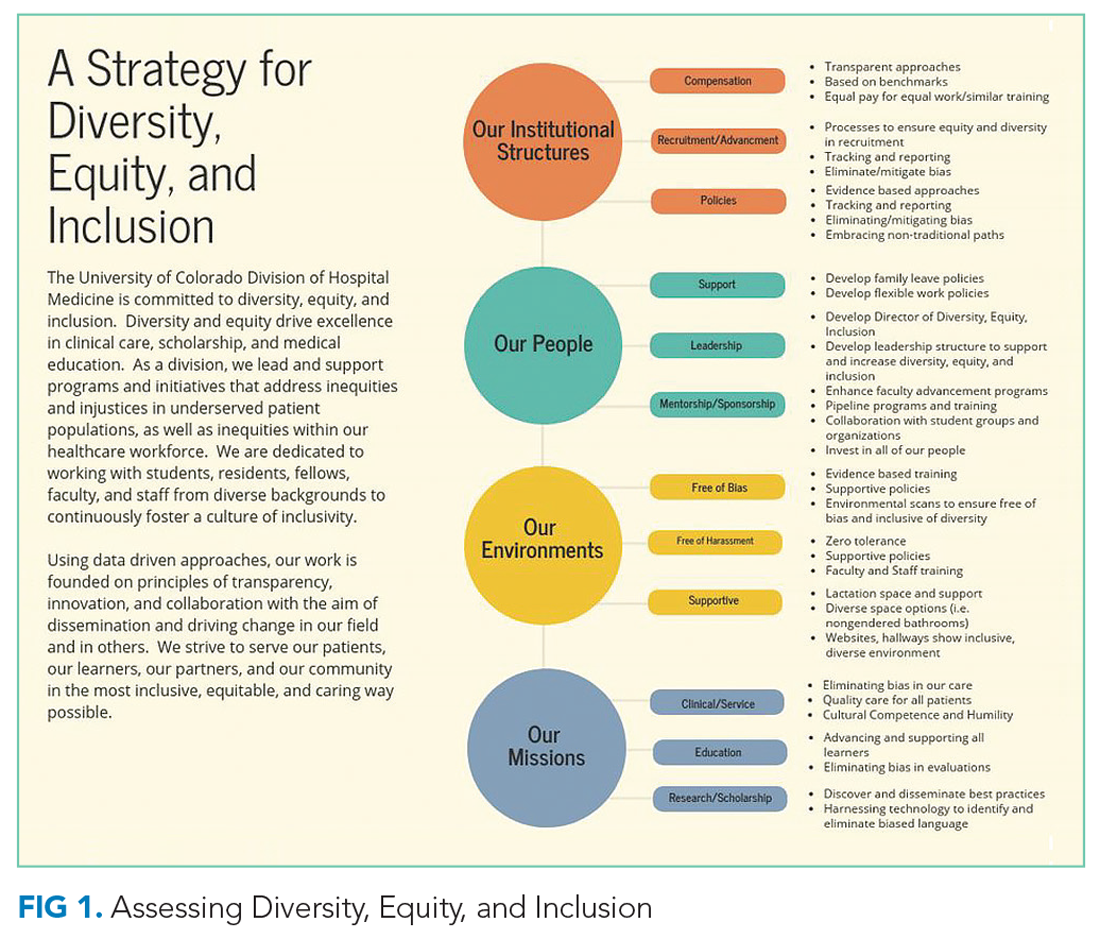

TThrough this work, and with stakeholder engagement, we developed a divisional strategic plan to address DEI globally. Our strategic plan included developing a DEI director role to assist with overseeing DEI efforts. We have highlighted the various methods utilized for each component (Figure 1). This work occurred from October 2017 to December 2018.

Our institutional structures

Using best practices from both medical and nonmedical fields, we developed evidence-based approaches to

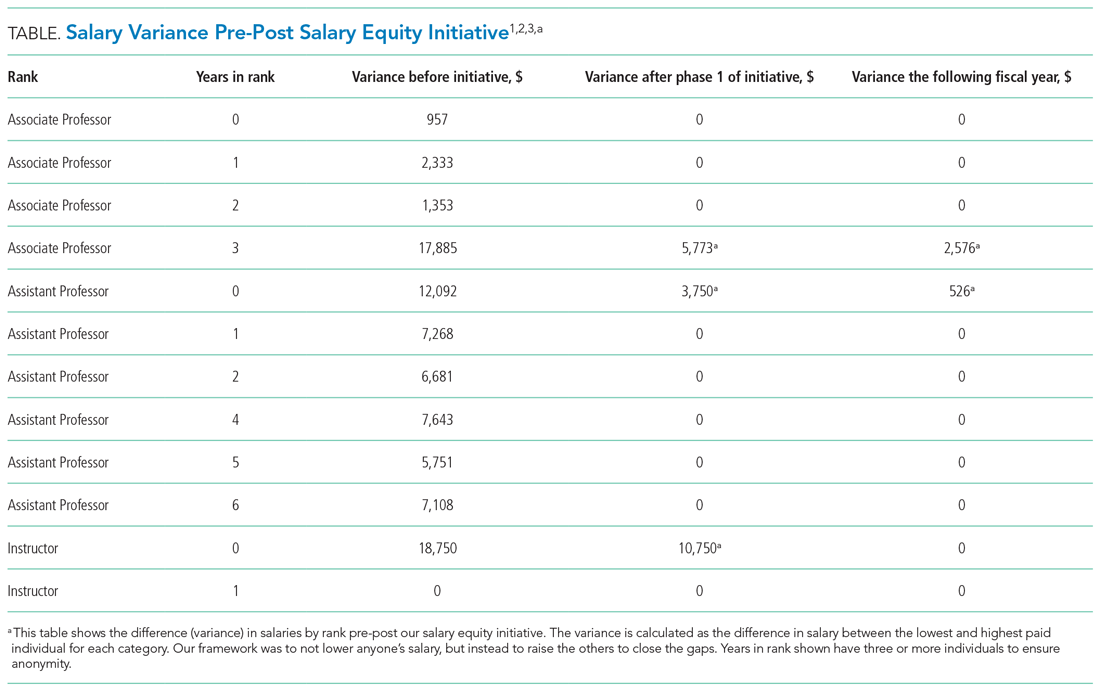

Compensation: transparent and consistent approaches based upon benchmarking with a framework of equal pay for equal work and similar advanced training/academic rank. In conjunction with efforts within the School of Medicine (SOM), Department of Medicine (DOM), and the UCH, our division sought to study salaries across DHM faculty members. We had an open call for faculty to participate in a newly developed DHM Compensation Committee, with the intent of rigorously examining our compensation practices and goals. Through faculty feedback and committee work, salary equity was defined as equal pay (ie, base salary for one clinical full-time equivalent [FTE]) for equal work based on academic rank and/or years of practice/advanced training. We also compared DHM salaries to regional academic hospital medicine groups and concluded that DHM salaries were lower than local and national benchmarks. This information was used to create a two-phase approach to increasing salaries for all individuals below the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) benchmarks33 for academic hospitalists. We also developed a stipend system for external roles that came with additional compensation and roles within our own division that came with additional pay (ie, nocturnist). Phase 1 focused on those whose salaries were furthest away from and below benchmark, and phase 2 targeted all remaining individuals below benchmark.

A similar review of FTEs (based on required number of shifts for a full-time hospitalist) tied to our internal DHM leadership positions was completed by the division head and director of DEI. Specifically, the mission for each of our internally funded roles, job descriptions, and responsibilities was reviewed to ensure equity in funding.

Recruitment and advancement: processes to ensure equity and diversity in recruitment, tracking, and reporting, working to eliminate/mitigate bias. In collaboration with members of the AAMC Group on Women in Medicine and Science (GWIMS) and coauthors from various institutions, we developed toolkits and checklists aimed at achieving equity and diversity within candidate pools and on major committees, including, but not limited to, search and promotion committees.32 Additionally, a checklist was developed to help recruit more diverse speakers, including women and URMs, for local, regional, and national conferences.

Policies: evidence-based approaches, tracking and reporting, standardized approaches to eliminate/mitigate bias, embracing nontraditional paths. In partnership with our departmental efforts, members of our team led data collection and reporting for salary benchmarking, leadership roles, and committee membership. This included developing surveys and reporting templates that can be used to identify disparities and inform future efforts. We worked to ensure that we have faculty representing our field at the department and SOM levels. Specifically, we made sure to nominate division members during open calls for departmental and schoolwide committees, including the promotions committee.

Our People

The faculty and staff within our division have been instrumental in moving efforts forward in the following important areas.

Leadership: develop the position of director of DEI as well as leadership structures to support and increase DEI. One of the first steps in our strategic plan was creating a director of DEI leadership role (Appendix Figure 2). The director is responsible for researching, applying, and promoting a broad scope of DEI initiatives and best practices within the DHM, DOM, and SOM (in collaboration with their leaders), including recruitment, retention, and promotion of medical students, residents, and faculty; educational program development; health disparities research; and community-engaged scholarship.

Support: develop family leave policies/develop flexible work policies. Several members of our division worked on departmental committees and served in leadership roles on staff and faculty council. Estimated costs were assessed. Through collective efforts of department leadership and division head support, the department approved parental leave to employees following the birth of an employee’s child or the placement of a child with an employee in connection with adoption or permanent foster care.

Mentorship/sponsorship: enhance faculty advancement programs/develop pipeline and trainings/collaborate with student groups and organizations/invest in all of our people. Faculty across our divisional sites have held important roles in developing pipeline programs for undergraduate students bound for health professions, as well as programs developed specifically for medical students and internal medicine residents. This includes two programs, the CU Hospitalist Scholars Program (CUHSP) and Leadership Education for Aspiring Doctors (LEAD), in which undergraduate students have the opportunity to round with hospital medicine teams, work on quality-improvement projects, and receive extensive mentorship and advising from a diverse faculty team. Additionally, our faculty advancement team within the DHM has grown and been restructured to include more defined goals and to ensure each faculty member has at least one mentor in their area of interest.

Supportive: lactation space and support/diverse space options/inclusive and diverse environments. We worked closely with hospital leadership to advocate for adequately equipped lactation spaces, including equipment such as pumps, refrigerators, and computer workstations.

Measures

Our measures focused on (1) development and implementation of our DEI strategic plan, including new policies, processes, and practices related to key components of the DEI program; and (2) assessment of specific DEI programs, including pre-post salary data disparities based on rank and pre-post disparities for protected time for similar roles.

Analysis

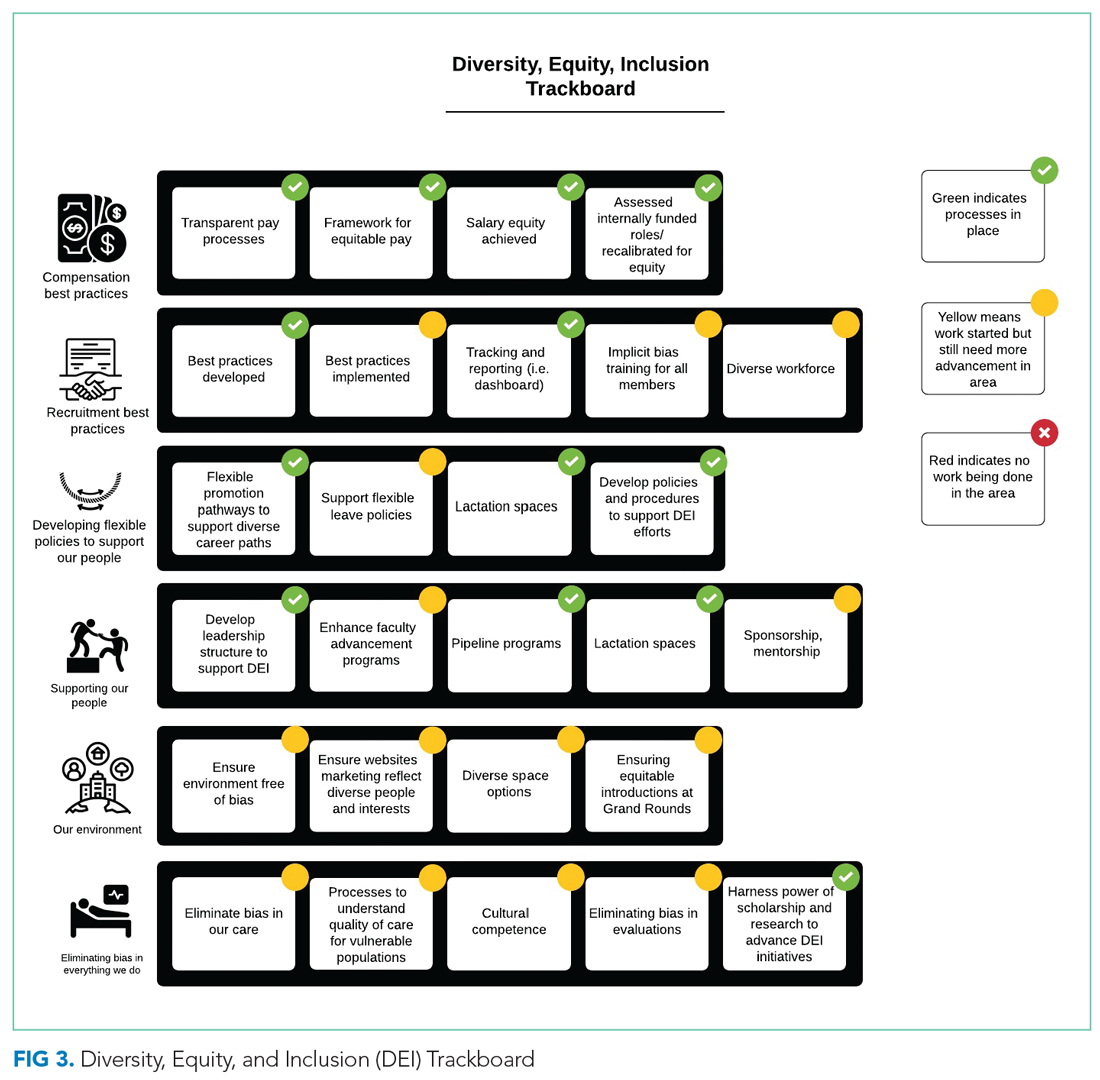

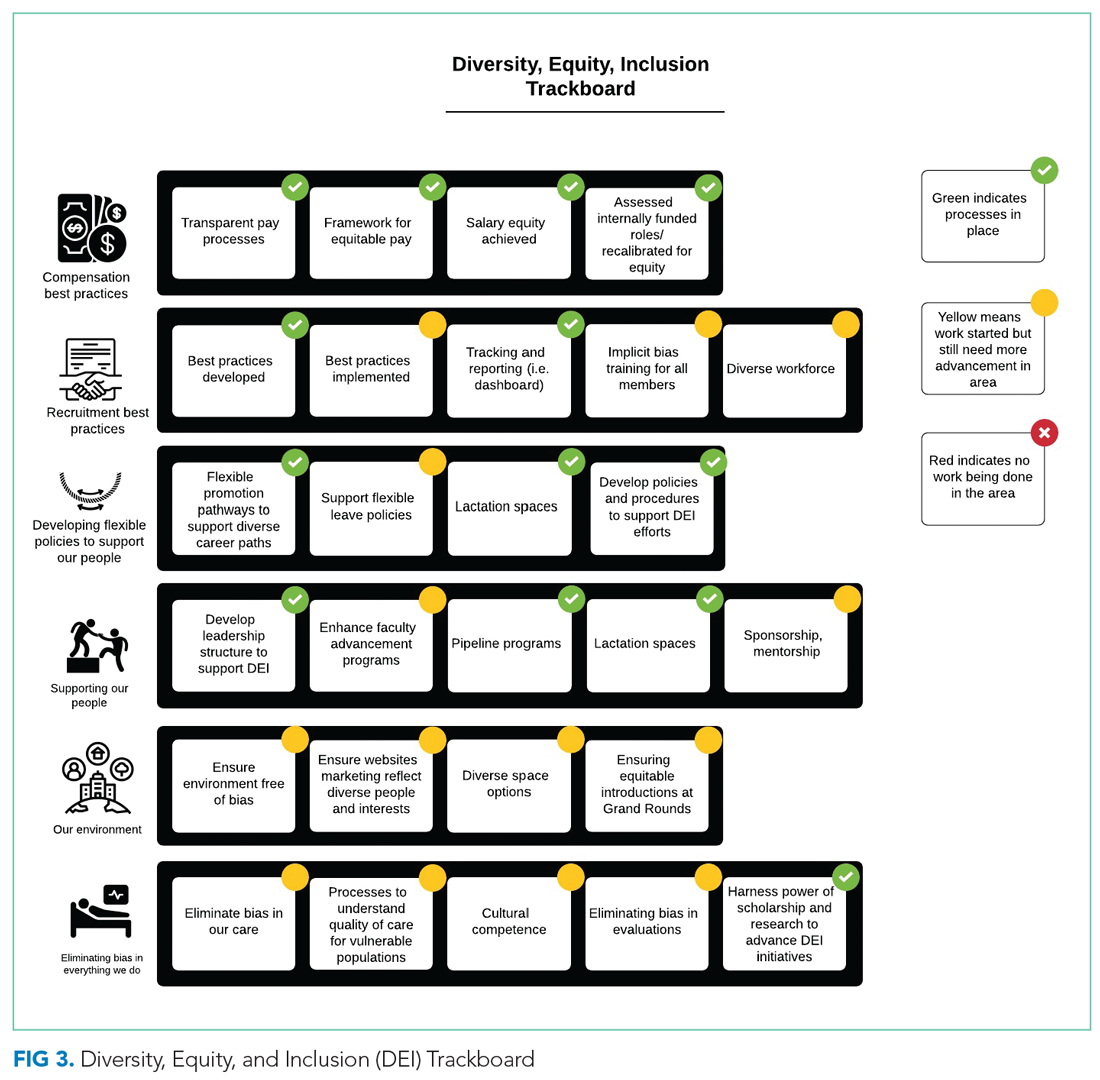

Through rapid PDSA cycles, we evaluated salary equity, equity in leadership allotment, and committee membership. We have developed a tracking board to track progress of the multiple projects in the strategic plan.

RESULTS

Strategic Plan Development and Tracking

From October 2017 to December 2018, we developed a robust strategic plan and stepwise approach to DEI (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The director of DEI position was developed (see Appendix Figure 2 for job description) to help oversee these efforts. Figure 3 highlights the specific efforts and the progress made on implementation (ie, high-level dashboard or “tracking board”). While outcomes are still pending in the areas of recruitment and advancement and environment, we have made measurable improvements in compensation, as outlined in the following section.

Compensation

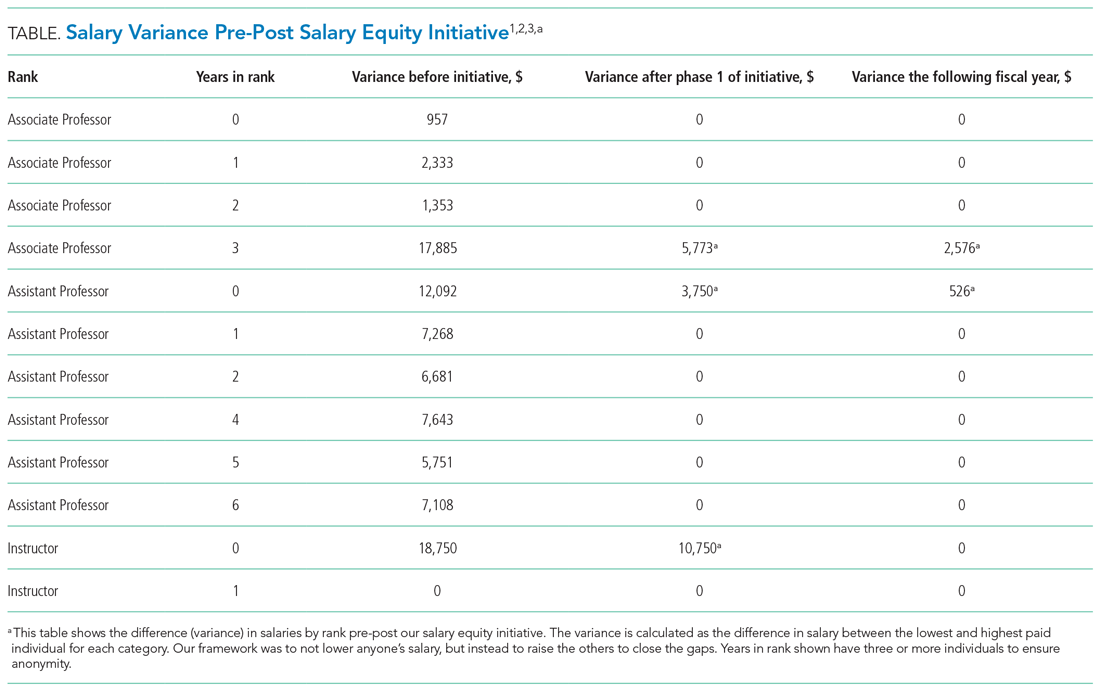

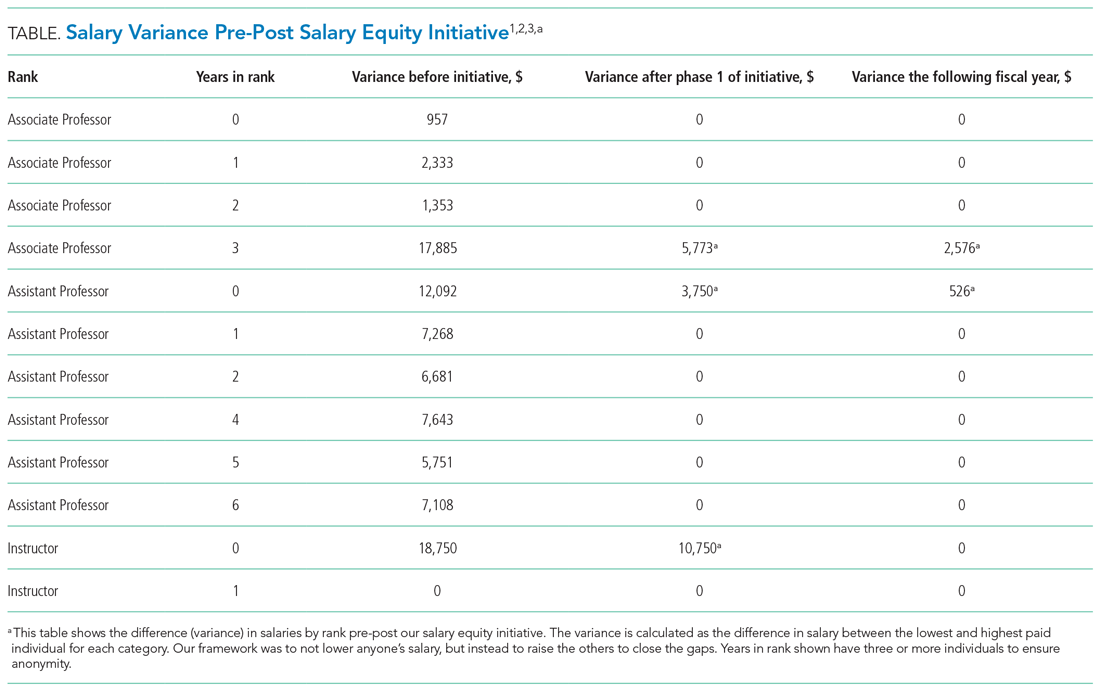

One year after the salary-equity interventions, all of our physician faculty’s salaries were at the goal benchmark (Table), and differences in salary for those in similar years of rank were nearly eliminated. Similarly, after implementing an internally consistent approach to assigning FTE for new and established positions within the division (ie, those that fall within the purview of the division), all faculty in similar types of roles had similar amounts of protected time.

Recruitment and Advancement

Toolkits32 and committee recommendations have been incorporated into division goals, though some aspects are still in implementation phases, as division-wide implicit bias training was delayed secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic. Key goals include: (1) implicit bias training for all members of major committees; (2) aiming for a goal of at least 40% representation of women and 40% URMs on committees; (3) having a diversity expert serve on each committee in order to identify and discuss any potential bias in the search and candidate-selection processes; and (4) careful tracking of diversity metrics in regard to diversity of candidates at each step of the interview and selection process.

Surveys and reporting templates for equity on committees and leadership positions have been developed and deployed. Data dashboards for our division have been developed as well (for compensation, leadership, and committee membership). A divisional dashboard to report recruitment efforts is in progress.

We have successfully nominated several faculty members to the SOM promotions committee and departmental committees during open calls for these positions. At the division level, we have also adapted internal policies to ensure promotion occurs on time and offers alternative pathways for faculty that may primarily focus on clinical pathways. All faculty who have gone up for promotion thus far have been successfully promoted in their desired pathway.

Environment

We successfully advocated and achieved adequately equipped lactation spaces, including equipment such as pumps, refrigerators, and computer workstations. This achievement was possible because of our hospital partners. Our efforts helped us acquire sufficient space and facilities such that nursing mothers can pump and still be able to answer phones, enter orders, and document visits.

Our team members conducted environmental scans and raised concerns when the environment was not inclusive, such as conference rooms with portraits of leadership that do not show diversity. The all-male pictures were removed from one frequently used departmental conference room, which will eventually house a diverse group of pictures and achievements.

We aim to eliminate bias by offering implicit bias training for our faculty. While this is presently required for those who serve on committees, in leadership positions, or those involved in recruitment and interviewing for the DOM, our goal is to eventually provide this training to all faculty and staff in the division. We have also incorporated DEI topics into our educational conferences for faculty, including sessions on recognizing bias in medicine, how to be an upstander/ally, and the impact of race and racism on medicine.

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this work are: (1) that successes in DEI can be achieved with strategic planning and stakeholder engagement; (2) through simple modification of processes, we can improve equity in compensation and FTE allotted to leadership; (3) though it takes time, diversity recruitment can be improved using sound, sustainable, evidence-based processes; (4) this work is time-intensive and challenging, requiring ongoing efforts to improve, modify, and enhance current efforts and future successes.

We have certainly made some progress with DEI initiatives within our division and have also learned a great deal from this experience. First, change is difficult for all parties involved, including those leading change and those affected by the changes. We purposely made an effort to facilitate discussions with all of the DHM faculty and staff to ensure that everyone felt included in this work and that everyone’s voice was heard. This was exemplified by inviting all faculty members to a feedback session in which we discussed DEI within our division and areas that we wanted to improve on. Early on, we were able to define what diversity, equity, and inclusion meant to us as a division and then use these definitions to develop tangible goals for all the areas of highest importance to the group.

By increasing faculty presence on key committees, such as the promotions committee, we now have faculty members who are well versed in promotions processes. We are fortunate to have a promotions process that supports faculty advancement for faculty with diverse interests that spans from supporting highly clinical faculty, clinician educators, as well as more traditional researchers.34 By having hospitalists serve in these roles, we help to add to the diverse perspectives on these committees, including emphasizing the scholarship that is associated with quality improvement, as well as DEI efforts which can often be viewed as service as opposed to scholarship.

Clear communication and transparency were key to all of our DEI initiatives. We had monthly updates on our DEI efforts during business meetings and also held impromptu meetings (also known as flash mobs35) to answer questions and discuss concerns in real time. As with all DEI work, it is important to know where you are starting (having accurate data and a clear understanding of the data) and be able to communicate that data to the group. For example, using AAMC salary benchmarking33 as well as other benchmarks allowed us to accurately calculate variance among salaries and identify the appropriate goal salary for each of our faculty members. Likewise, by completing an in-depth inventory on the work being done by all of our faculty in leadership roles, we were able to standardize the compensation/FTE for each of these roles. Tracking these changes over time, via the use of dashboards in our case, allows for real-time measurements and accountability for all of those involved. Our end goal will be to have all of these initiatives feed into one large dashboard.

Collaborating with leadership and stakeholders in the DOM, SOM, and hospital helped to make our DEI initiatives successful. Much too often, we work in silos when it comes to DEI work. However, we tend to have similar goals and can achieve much more if we work together. Collaboration with multiple stakeholders allowed for wider dissemination and resulted in a larger impact to the campus and community at large. This has been exemplified by the committee composition guidance that has been utilized by the DOM, as well as implementation of campus-wide policies, specifically the parental leave policy, which our faculty members played an important role in creating. Likewise, it is important to look outside of our institutions and work with other hospital medicine groups around the country who are interested in promoting DEI.

We still have much work ahead of us. We are continuing to measure outcomes status postimplementation of the toolkit and checklists being used for diversity recruitment and committee composition. Additionally, we are actively working on several initiatives, including:

- Instituting implicit bias training for all of our faculty

- Partnering with national leaders and our hospital systems to develop zero-tolerance policies regarding abusive behaviors (verbal, physical, and other), racism, and sexism in the hospital and other work settings

- Development of specific recruitment strategies as a means of diversifying our healthcare workforce (of note, based on a 2020 survey of our faculty, in which there was a 70% response rate, 8.5% of our faculty identified as URMs)

- Completion of a diversity dashboard to track our progress in all of these efforts over time

- Development of a more robust pipeline to promotion and leadership for our URM faculty

This study has several strengths. Many of the plans and strategies described here can be used to guide others interested in implementing this work. Figure 2 provides a stepwise

approach to addressing DEI in hospital medicine groups and divisions. We conducted this work at a large academic medical center, and while it may not be generalizable, it does offer some ideas for others to consider in their own work to advance DEI at their institutions. There are also several limitations to this work. Eliminating salary inequities with our approach did take resources. We took advantage of already lower salaries and the need to increase salaries closer to benchmark and paired this effort with our DEI efforts to achieve salary equity. This required partnerships with the department and hospital. Efforts to advance DEI also take a lot of time and effort, and thus commitment from the division, department, and institution as a whole is key. While we have outcomes for our efforts related to salary equity, recruitment efforts should be realized over time, as currently it is too early to tell. We have highlighted the efforts that have been put in place at this time.

CONCLUSION

Using a systematic evidence-based approach with key stakeholder involvement, a division-wide DEI strategy was developed and implemented. While this work is still ongoing, short-term wins are possible, in particular around salary equity and development of policies and structures to promote DEI.

1. Underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. National Institutes of Health website. Accessed December 26, 2020. https://extramural-diversity.nih.gov/diversity-matters/underrepresented-groups

2. Ash AS, Carr PL, Goldstein R, Friedman RH. Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: is there equity? Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(3):205-212. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00009

3. Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1149-1158. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10680

4. Fang D, Moy E, Colburn L, Hurley J. Racial and ethnic disparities in faculty promotion in academic medicine. JAMA. 2000;284(9):1085-1092. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.9.1085

5. Baptiste D, Fecher AM, Dolejs SC, et al. Gender differences in academic surgery, work-life balance, and satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2017;218:99-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.075

6. Hart KL, Perlis RH. Trends in proportion of women as authors of medical journal articles, 2008-2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1285-1287. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0907

7. Thomas EG, Jayabalasingham B, Collins T, Geertzen J, Bui C, Dominici F. Gender disparities in invited commentary authorship in 2459 medical journals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913682. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13682

8. Hechtman LA, Moore NP, Schulkey CE, et al. NIH funding longevity by gender. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(31):7943-7948. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800615115

9. Sege R, Nykiel-Bub L, Selk S. Sex differences in institutional support for junior biomedical researchers. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1175-1177. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.8517

10. Silver JK, Slocum CS, Bank AM, et al. Where are the women? The underrepresentation of women physicians among recognition award recipients from medical specialty societies. PM R. 2017;9(8):804-815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.06.001

11. Ruzycki SM, Fletcher S, Earp M, Bharwani A, Lithgow KC. Trends in the proportion of female speakers at medical conferences in the United States and in Canada, 2007 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2103

12. Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Gender differences in academic medicine: retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the National Faculty Survey. Acad Med. 2018;93(11):1694-1699. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002146

13. Carr PL, Gunn C, Raj A, Kaplan S, Freund KM. Recruitment, promotion, and retention of women in academic medicine: how institutions are addressing gender disparities. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(3):374-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2016.11.003

14. Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294-1304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3284

15. Lo Sasso AT, Richards MR, Chou CF, Gerber SE. The $16,819 pay gap for newly trained physicians: the unexplained trend of men earning more than women. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(2):193-201. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0597

16. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-517. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199608153350713

17. Weaver AC, Wetterneck TB, Whelan CT, Hinami K. A matter of priorities? Exploring the persistent gender pay gap in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):486-490. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2400

18. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

19. Northcutt N, Papp S, Keniston A, et al, Society of Hospital Medicine Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Special Interest Group. SPEAKers at the National Society of Hospital Medicine Meeting: a follow-up study of gender equity for conference speakers from 2015 to 2019. The SPEAK UP Study. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(4):228-231. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3401

20. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(7):393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

21. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Promoting gender equity at the Journal of Hospital Medicine [editorial]. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):517. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3522

22. Sheehy AM, Kolehmainen C, Carnes M. We specialize in change leadership: a call for hospitalists to lead the quest for workforce gender equity [editorial]. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):551-552. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2399

23. Evans MK, Rosenbaum L, Malina D, Morrissey S, Rubin EJ. Diagnosing and treating systemic racism [editorial]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):274-276. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe2021693

24. Rock D, Grant H. Why diverse teams are smarter. Harvard Business Review. Published November 4, 2016. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter

25. Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):101-110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30262.x

26. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competence and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):499-505. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.499

27. Acosta D, Ackerman-Barger K. Breaking the silence: time to talk about race and racism [comment]. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):285-288. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001416

28. Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):90-102. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90

29. Chang E, Simon M, Dong X. Integrating cultural humility into health care professional education and training. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17(2):269-278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9264-1

30. Foronda C, Baptiste DL, Reinholdt MM, Ousman K. Cultural humility: a concept analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(3):210-217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615592677

31. Butkus R, Serchen J, Moyer DV, et al; Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Achieving gender equity in physician compensation and career advancement: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(10):721-723. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3438

32. Burden M, del Pino-Jones A, Shafer M, Sheth S, Rexrode K. GWIMS Equity Recruitment Toolkit. Accessed July 27, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/download/492864/data/equityinrecruitmenttoolkit.pdf

33. AAMC Faculty Salary Report. AAMC website. Accessed September 6, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/aamc-faculty-salary-report

34. Promotion process. University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus website. Accessed September 7, 2020. https://medschool.cuanschutz.edu/faculty-affairs/for-faculty/promotion-and-tenure/promotion-process

35. Pierce RG, Diaz M, Kneeland P. Optimizing well-being, practice culture, and professional thriving in an era of turbulence. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):126-128. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3101

Studies continue to demonstrate persistent gaps in equity for women and underrepresented minorities (URMs)1 throughout nearly all aspects of academic medicine, including rank,2-4 tenure,5 authorship,6,7 funding opportunities,8,9 awards,10 speakership,11 leadership,12,13 and salaries.2,14,15

In this article, we report DEI efforts within our division, focusing on the development of our strategic plan and specific outcomes related to compensation, recruitment, and policies.

METHODS

Our Division’s Framework to DEI—“It Takes a Village”

Our Division of Hospital Medicine (DHM), previously within the Division of General Internal Medicine, was founded in October 2017. The DHM at the University of Colorado Hospital (UCH) is composed of 100 faculty members (70 physicians and 30 advanced-practice providers; 58% women and 42% men). In 2018, we implemented a stepwise approach to critically assess DEI within our group and to build a strategic plan to address the issues.

As a new division, we sought stakeholder feedback from division members. All faculty within the division were invited to attend a meeting in which issues related to DEI were discussed. A literature review that spanned both medical and nonmedical fields was also completed. Search terms included salary equity, gender equity, diverse teams, diversity recruitment and retention, diversifying leadership, and diverse speakers. Salaries, internally funded time, and other processes, such as recruitment, promotion, and hiring for leadership positions, were evaluated during the first year we became a division.

TThrough this work, and with stakeholder engagement, we developed a divisional strategic plan to address DEI globally. Our strategic plan included developing a DEI director role to assist with overseeing DEI efforts. We have highlighted the various methods utilized for each component (Figure 1). This work occurred from October 2017 to December 2018.

Our institutional structures

Using best practices from both medical and nonmedical fields, we developed evidence-based approaches to

Compensation: transparent and consistent approaches based upon benchmarking with a framework of equal pay for equal work and similar advanced training/academic rank. In conjunction with efforts within the School of Medicine (SOM), Department of Medicine (DOM), and the UCH, our division sought to study salaries across DHM faculty members. We had an open call for faculty to participate in a newly developed DHM Compensation Committee, with the intent of rigorously examining our compensation practices and goals. Through faculty feedback and committee work, salary equity was defined as equal pay (ie, base salary for one clinical full-time equivalent [FTE]) for equal work based on academic rank and/or years of practice/advanced training. We also compared DHM salaries to regional academic hospital medicine groups and concluded that DHM salaries were lower than local and national benchmarks. This information was used to create a two-phase approach to increasing salaries for all individuals below the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) benchmarks33 for academic hospitalists. We also developed a stipend system for external roles that came with additional compensation and roles within our own division that came with additional pay (ie, nocturnist). Phase 1 focused on those whose salaries were furthest away from and below benchmark, and phase 2 targeted all remaining individuals below benchmark.

A similar review of FTEs (based on required number of shifts for a full-time hospitalist) tied to our internal DHM leadership positions was completed by the division head and director of DEI. Specifically, the mission for each of our internally funded roles, job descriptions, and responsibilities was reviewed to ensure equity in funding.

Recruitment and advancement: processes to ensure equity and diversity in recruitment, tracking, and reporting, working to eliminate/mitigate bias. In collaboration with members of the AAMC Group on Women in Medicine and Science (GWIMS) and coauthors from various institutions, we developed toolkits and checklists aimed at achieving equity and diversity within candidate pools and on major committees, including, but not limited to, search and promotion committees.32 Additionally, a checklist was developed to help recruit more diverse speakers, including women and URMs, for local, regional, and national conferences.

Policies: evidence-based approaches, tracking and reporting, standardized approaches to eliminate/mitigate bias, embracing nontraditional paths. In partnership with our departmental efforts, members of our team led data collection and reporting for salary benchmarking, leadership roles, and committee membership. This included developing surveys and reporting templates that can be used to identify disparities and inform future efforts. We worked to ensure that we have faculty representing our field at the department and SOM levels. Specifically, we made sure to nominate division members during open calls for departmental and schoolwide committees, including the promotions committee.

Our People

The faculty and staff within our division have been instrumental in moving efforts forward in the following important areas.

Leadership: develop the position of director of DEI as well as leadership structures to support and increase DEI. One of the first steps in our strategic plan was creating a director of DEI leadership role (Appendix Figure 2). The director is responsible for researching, applying, and promoting a broad scope of DEI initiatives and best practices within the DHM, DOM, and SOM (in collaboration with their leaders), including recruitment, retention, and promotion of medical students, residents, and faculty; educational program development; health disparities research; and community-engaged scholarship.

Support: develop family leave policies/develop flexible work policies. Several members of our division worked on departmental committees and served in leadership roles on staff and faculty council. Estimated costs were assessed. Through collective efforts of department leadership and division head support, the department approved parental leave to employees following the birth of an employee’s child or the placement of a child with an employee in connection with adoption or permanent foster care.

Mentorship/sponsorship: enhance faculty advancement programs/develop pipeline and trainings/collaborate with student groups and organizations/invest in all of our people. Faculty across our divisional sites have held important roles in developing pipeline programs for undergraduate students bound for health professions, as well as programs developed specifically for medical students and internal medicine residents. This includes two programs, the CU Hospitalist Scholars Program (CUHSP) and Leadership Education for Aspiring Doctors (LEAD), in which undergraduate students have the opportunity to round with hospital medicine teams, work on quality-improvement projects, and receive extensive mentorship and advising from a diverse faculty team. Additionally, our faculty advancement team within the DHM has grown and been restructured to include more defined goals and to ensure each faculty member has at least one mentor in their area of interest.

Supportive: lactation space and support/diverse space options/inclusive and diverse environments. We worked closely with hospital leadership to advocate for adequately equipped lactation spaces, including equipment such as pumps, refrigerators, and computer workstations.

Measures

Our measures focused on (1) development and implementation of our DEI strategic plan, including new policies, processes, and practices related to key components of the DEI program; and (2) assessment of specific DEI programs, including pre-post salary data disparities based on rank and pre-post disparities for protected time for similar roles.

Analysis

Through rapid PDSA cycles, we evaluated salary equity, equity in leadership allotment, and committee membership. We have developed a tracking board to track progress of the multiple projects in the strategic plan.

RESULTS

Strategic Plan Development and Tracking

From October 2017 to December 2018, we developed a robust strategic plan and stepwise approach to DEI (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The director of DEI position was developed (see Appendix Figure 2 for job description) to help oversee these efforts. Figure 3 highlights the specific efforts and the progress made on implementation (ie, high-level dashboard or “tracking board”). While outcomes are still pending in the areas of recruitment and advancement and environment, we have made measurable improvements in compensation, as outlined in the following section.

Compensation

One year after the salary-equity interventions, all of our physician faculty’s salaries were at the goal benchmark (Table), and differences in salary for those in similar years of rank were nearly eliminated. Similarly, after implementing an internally consistent approach to assigning FTE for new and established positions within the division (ie, those that fall within the purview of the division), all faculty in similar types of roles had similar amounts of protected time.

Recruitment and Advancement

Toolkits32 and committee recommendations have been incorporated into division goals, though some aspects are still in implementation phases, as division-wide implicit bias training was delayed secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic. Key goals include: (1) implicit bias training for all members of major committees; (2) aiming for a goal of at least 40% representation of women and 40% URMs on committees; (3) having a diversity expert serve on each committee in order to identify and discuss any potential bias in the search and candidate-selection processes; and (4) careful tracking of diversity metrics in regard to diversity of candidates at each step of the interview and selection process.

Surveys and reporting templates for equity on committees and leadership positions have been developed and deployed. Data dashboards for our division have been developed as well (for compensation, leadership, and committee membership). A divisional dashboard to report recruitment efforts is in progress.

We have successfully nominated several faculty members to the SOM promotions committee and departmental committees during open calls for these positions. At the division level, we have also adapted internal policies to ensure promotion occurs on time and offers alternative pathways for faculty that may primarily focus on clinical pathways. All faculty who have gone up for promotion thus far have been successfully promoted in their desired pathway.

Environment

We successfully advocated and achieved adequately equipped lactation spaces, including equipment such as pumps, refrigerators, and computer workstations. This achievement was possible because of our hospital partners. Our efforts helped us acquire sufficient space and facilities such that nursing mothers can pump and still be able to answer phones, enter orders, and document visits.

Our team members conducted environmental scans and raised concerns when the environment was not inclusive, such as conference rooms with portraits of leadership that do not show diversity. The all-male pictures were removed from one frequently used departmental conference room, which will eventually house a diverse group of pictures and achievements.

We aim to eliminate bias by offering implicit bias training for our faculty. While this is presently required for those who serve on committees, in leadership positions, or those involved in recruitment and interviewing for the DOM, our goal is to eventually provide this training to all faculty and staff in the division. We have also incorporated DEI topics into our educational conferences for faculty, including sessions on recognizing bias in medicine, how to be an upstander/ally, and the impact of race and racism on medicine.

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this work are: (1) that successes in DEI can be achieved with strategic planning and stakeholder engagement; (2) through simple modification of processes, we can improve equity in compensation and FTE allotted to leadership; (3) though it takes time, diversity recruitment can be improved using sound, sustainable, evidence-based processes; (4) this work is time-intensive and challenging, requiring ongoing efforts to improve, modify, and enhance current efforts and future successes.

We have certainly made some progress with DEI initiatives within our division and have also learned a great deal from this experience. First, change is difficult for all parties involved, including those leading change and those affected by the changes. We purposely made an effort to facilitate discussions with all of the DHM faculty and staff to ensure that everyone felt included in this work and that everyone’s voice was heard. This was exemplified by inviting all faculty members to a feedback session in which we discussed DEI within our division and areas that we wanted to improve on. Early on, we were able to define what diversity, equity, and inclusion meant to us as a division and then use these definitions to develop tangible goals for all the areas of highest importance to the group.

By increasing faculty presence on key committees, such as the promotions committee, we now have faculty members who are well versed in promotions processes. We are fortunate to have a promotions process that supports faculty advancement for faculty with diverse interests that spans from supporting highly clinical faculty, clinician educators, as well as more traditional researchers.34 By having hospitalists serve in these roles, we help to add to the diverse perspectives on these committees, including emphasizing the scholarship that is associated with quality improvement, as well as DEI efforts which can often be viewed as service as opposed to scholarship.

Clear communication and transparency were key to all of our DEI initiatives. We had monthly updates on our DEI efforts during business meetings and also held impromptu meetings (also known as flash mobs35) to answer questions and discuss concerns in real time. As with all DEI work, it is important to know where you are starting (having accurate data and a clear understanding of the data) and be able to communicate that data to the group. For example, using AAMC salary benchmarking33 as well as other benchmarks allowed us to accurately calculate variance among salaries and identify the appropriate goal salary for each of our faculty members. Likewise, by completing an in-depth inventory on the work being done by all of our faculty in leadership roles, we were able to standardize the compensation/FTE for each of these roles. Tracking these changes over time, via the use of dashboards in our case, allows for real-time measurements and accountability for all of those involved. Our end goal will be to have all of these initiatives feed into one large dashboard.

Collaborating with leadership and stakeholders in the DOM, SOM, and hospital helped to make our DEI initiatives successful. Much too often, we work in silos when it comes to DEI work. However, we tend to have similar goals and can achieve much more if we work together. Collaboration with multiple stakeholders allowed for wider dissemination and resulted in a larger impact to the campus and community at large. This has been exemplified by the committee composition guidance that has been utilized by the DOM, as well as implementation of campus-wide policies, specifically the parental leave policy, which our faculty members played an important role in creating. Likewise, it is important to look outside of our institutions and work with other hospital medicine groups around the country who are interested in promoting DEI.

We still have much work ahead of us. We are continuing to measure outcomes status postimplementation of the toolkit and checklists being used for diversity recruitment and committee composition. Additionally, we are actively working on several initiatives, including:

- Instituting implicit bias training for all of our faculty

- Partnering with national leaders and our hospital systems to develop zero-tolerance policies regarding abusive behaviors (verbal, physical, and other), racism, and sexism in the hospital and other work settings

- Development of specific recruitment strategies as a means of diversifying our healthcare workforce (of note, based on a 2020 survey of our faculty, in which there was a 70% response rate, 8.5% of our faculty identified as URMs)

- Completion of a diversity dashboard to track our progress in all of these efforts over time

- Development of a more robust pipeline to promotion and leadership for our URM faculty

This study has several strengths. Many of the plans and strategies described here can be used to guide others interested in implementing this work. Figure 2 provides a stepwise

approach to addressing DEI in hospital medicine groups and divisions. We conducted this work at a large academic medical center, and while it may not be generalizable, it does offer some ideas for others to consider in their own work to advance DEI at their institutions. There are also several limitations to this work. Eliminating salary inequities with our approach did take resources. We took advantage of already lower salaries and the need to increase salaries closer to benchmark and paired this effort with our DEI efforts to achieve salary equity. This required partnerships with the department and hospital. Efforts to advance DEI also take a lot of time and effort, and thus commitment from the division, department, and institution as a whole is key. While we have outcomes for our efforts related to salary equity, recruitment efforts should be realized over time, as currently it is too early to tell. We have highlighted the efforts that have been put in place at this time.

CONCLUSION

Using a systematic evidence-based approach with key stakeholder involvement, a division-wide DEI strategy was developed and implemented. While this work is still ongoing, short-term wins are possible, in particular around salary equity and development of policies and structures to promote DEI.

Studies continue to demonstrate persistent gaps in equity for women and underrepresented minorities (URMs)1 throughout nearly all aspects of academic medicine, including rank,2-4 tenure,5 authorship,6,7 funding opportunities,8,9 awards,10 speakership,11 leadership,12,13 and salaries.2,14,15

In this article, we report DEI efforts within our division, focusing on the development of our strategic plan and specific outcomes related to compensation, recruitment, and policies.

METHODS

Our Division’s Framework to DEI—“It Takes a Village”

Our Division of Hospital Medicine (DHM), previously within the Division of General Internal Medicine, was founded in October 2017. The DHM at the University of Colorado Hospital (UCH) is composed of 100 faculty members (70 physicians and 30 advanced-practice providers; 58% women and 42% men). In 2018, we implemented a stepwise approach to critically assess DEI within our group and to build a strategic plan to address the issues.

As a new division, we sought stakeholder feedback from division members. All faculty within the division were invited to attend a meeting in which issues related to DEI were discussed. A literature review that spanned both medical and nonmedical fields was also completed. Search terms included salary equity, gender equity, diverse teams, diversity recruitment and retention, diversifying leadership, and diverse speakers. Salaries, internally funded time, and other processes, such as recruitment, promotion, and hiring for leadership positions, were evaluated during the first year we became a division.

TThrough this work, and with stakeholder engagement, we developed a divisional strategic plan to address DEI globally. Our strategic plan included developing a DEI director role to assist with overseeing DEI efforts. We have highlighted the various methods utilized for each component (Figure 1). This work occurred from October 2017 to December 2018.

Our institutional structures

Using best practices from both medical and nonmedical fields, we developed evidence-based approaches to

Compensation: transparent and consistent approaches based upon benchmarking with a framework of equal pay for equal work and similar advanced training/academic rank. In conjunction with efforts within the School of Medicine (SOM), Department of Medicine (DOM), and the UCH, our division sought to study salaries across DHM faculty members. We had an open call for faculty to participate in a newly developed DHM Compensation Committee, with the intent of rigorously examining our compensation practices and goals. Through faculty feedback and committee work, salary equity was defined as equal pay (ie, base salary for one clinical full-time equivalent [FTE]) for equal work based on academic rank and/or years of practice/advanced training. We also compared DHM salaries to regional academic hospital medicine groups and concluded that DHM salaries were lower than local and national benchmarks. This information was used to create a two-phase approach to increasing salaries for all individuals below the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) benchmarks33 for academic hospitalists. We also developed a stipend system for external roles that came with additional compensation and roles within our own division that came with additional pay (ie, nocturnist). Phase 1 focused on those whose salaries were furthest away from and below benchmark, and phase 2 targeted all remaining individuals below benchmark.

A similar review of FTEs (based on required number of shifts for a full-time hospitalist) tied to our internal DHM leadership positions was completed by the division head and director of DEI. Specifically, the mission for each of our internally funded roles, job descriptions, and responsibilities was reviewed to ensure equity in funding.

Recruitment and advancement: processes to ensure equity and diversity in recruitment, tracking, and reporting, working to eliminate/mitigate bias. In collaboration with members of the AAMC Group on Women in Medicine and Science (GWIMS) and coauthors from various institutions, we developed toolkits and checklists aimed at achieving equity and diversity within candidate pools and on major committees, including, but not limited to, search and promotion committees.32 Additionally, a checklist was developed to help recruit more diverse speakers, including women and URMs, for local, regional, and national conferences.

Policies: evidence-based approaches, tracking and reporting, standardized approaches to eliminate/mitigate bias, embracing nontraditional paths. In partnership with our departmental efforts, members of our team led data collection and reporting for salary benchmarking, leadership roles, and committee membership. This included developing surveys and reporting templates that can be used to identify disparities and inform future efforts. We worked to ensure that we have faculty representing our field at the department and SOM levels. Specifically, we made sure to nominate division members during open calls for departmental and schoolwide committees, including the promotions committee.

Our People

The faculty and staff within our division have been instrumental in moving efforts forward in the following important areas.

Leadership: develop the position of director of DEI as well as leadership structures to support and increase DEI. One of the first steps in our strategic plan was creating a director of DEI leadership role (Appendix Figure 2). The director is responsible for researching, applying, and promoting a broad scope of DEI initiatives and best practices within the DHM, DOM, and SOM (in collaboration with their leaders), including recruitment, retention, and promotion of medical students, residents, and faculty; educational program development; health disparities research; and community-engaged scholarship.

Support: develop family leave policies/develop flexible work policies. Several members of our division worked on departmental committees and served in leadership roles on staff and faculty council. Estimated costs were assessed. Through collective efforts of department leadership and division head support, the department approved parental leave to employees following the birth of an employee’s child or the placement of a child with an employee in connection with adoption or permanent foster care.

Mentorship/sponsorship: enhance faculty advancement programs/develop pipeline and trainings/collaborate with student groups and organizations/invest in all of our people. Faculty across our divisional sites have held important roles in developing pipeline programs for undergraduate students bound for health professions, as well as programs developed specifically for medical students and internal medicine residents. This includes two programs, the CU Hospitalist Scholars Program (CUHSP) and Leadership Education for Aspiring Doctors (LEAD), in which undergraduate students have the opportunity to round with hospital medicine teams, work on quality-improvement projects, and receive extensive mentorship and advising from a diverse faculty team. Additionally, our faculty advancement team within the DHM has grown and been restructured to include more defined goals and to ensure each faculty member has at least one mentor in their area of interest.

Supportive: lactation space and support/diverse space options/inclusive and diverse environments. We worked closely with hospital leadership to advocate for adequately equipped lactation spaces, including equipment such as pumps, refrigerators, and computer workstations.

Measures

Our measures focused on (1) development and implementation of our DEI strategic plan, including new policies, processes, and practices related to key components of the DEI program; and (2) assessment of specific DEI programs, including pre-post salary data disparities based on rank and pre-post disparities for protected time for similar roles.

Analysis

Through rapid PDSA cycles, we evaluated salary equity, equity in leadership allotment, and committee membership. We have developed a tracking board to track progress of the multiple projects in the strategic plan.

RESULTS

Strategic Plan Development and Tracking

From October 2017 to December 2018, we developed a robust strategic plan and stepwise approach to DEI (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The director of DEI position was developed (see Appendix Figure 2 for job description) to help oversee these efforts. Figure 3 highlights the specific efforts and the progress made on implementation (ie, high-level dashboard or “tracking board”). While outcomes are still pending in the areas of recruitment and advancement and environment, we have made measurable improvements in compensation, as outlined in the following section.

Compensation

One year after the salary-equity interventions, all of our physician faculty’s salaries were at the goal benchmark (Table), and differences in salary for those in similar years of rank were nearly eliminated. Similarly, after implementing an internally consistent approach to assigning FTE for new and established positions within the division (ie, those that fall within the purview of the division), all faculty in similar types of roles had similar amounts of protected time.

Recruitment and Advancement

Toolkits32 and committee recommendations have been incorporated into division goals, though some aspects are still in implementation phases, as division-wide implicit bias training was delayed secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic. Key goals include: (1) implicit bias training for all members of major committees; (2) aiming for a goal of at least 40% representation of women and 40% URMs on committees; (3) having a diversity expert serve on each committee in order to identify and discuss any potential bias in the search and candidate-selection processes; and (4) careful tracking of diversity metrics in regard to diversity of candidates at each step of the interview and selection process.

Surveys and reporting templates for equity on committees and leadership positions have been developed and deployed. Data dashboards for our division have been developed as well (for compensation, leadership, and committee membership). A divisional dashboard to report recruitment efforts is in progress.

We have successfully nominated several faculty members to the SOM promotions committee and departmental committees during open calls for these positions. At the division level, we have also adapted internal policies to ensure promotion occurs on time and offers alternative pathways for faculty that may primarily focus on clinical pathways. All faculty who have gone up for promotion thus far have been successfully promoted in their desired pathway.

Environment

We successfully advocated and achieved adequately equipped lactation spaces, including equipment such as pumps, refrigerators, and computer workstations. This achievement was possible because of our hospital partners. Our efforts helped us acquire sufficient space and facilities such that nursing mothers can pump and still be able to answer phones, enter orders, and document visits.

Our team members conducted environmental scans and raised concerns when the environment was not inclusive, such as conference rooms with portraits of leadership that do not show diversity. The all-male pictures were removed from one frequently used departmental conference room, which will eventually house a diverse group of pictures and achievements.

We aim to eliminate bias by offering implicit bias training for our faculty. While this is presently required for those who serve on committees, in leadership positions, or those involved in recruitment and interviewing for the DOM, our goal is to eventually provide this training to all faculty and staff in the division. We have also incorporated DEI topics into our educational conferences for faculty, including sessions on recognizing bias in medicine, how to be an upstander/ally, and the impact of race and racism on medicine.

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this work are: (1) that successes in DEI can be achieved with strategic planning and stakeholder engagement; (2) through simple modification of processes, we can improve equity in compensation and FTE allotted to leadership; (3) though it takes time, diversity recruitment can be improved using sound, sustainable, evidence-based processes; (4) this work is time-intensive and challenging, requiring ongoing efforts to improve, modify, and enhance current efforts and future successes.

We have certainly made some progress with DEI initiatives within our division and have also learned a great deal from this experience. First, change is difficult for all parties involved, including those leading change and those affected by the changes. We purposely made an effort to facilitate discussions with all of the DHM faculty and staff to ensure that everyone felt included in this work and that everyone’s voice was heard. This was exemplified by inviting all faculty members to a feedback session in which we discussed DEI within our division and areas that we wanted to improve on. Early on, we were able to define what diversity, equity, and inclusion meant to us as a division and then use these definitions to develop tangible goals for all the areas of highest importance to the group.

By increasing faculty presence on key committees, such as the promotions committee, we now have faculty members who are well versed in promotions processes. We are fortunate to have a promotions process that supports faculty advancement for faculty with diverse interests that spans from supporting highly clinical faculty, clinician educators, as well as more traditional researchers.34 By having hospitalists serve in these roles, we help to add to the diverse perspectives on these committees, including emphasizing the scholarship that is associated with quality improvement, as well as DEI efforts which can often be viewed as service as opposed to scholarship.

Clear communication and transparency were key to all of our DEI initiatives. We had monthly updates on our DEI efforts during business meetings and also held impromptu meetings (also known as flash mobs35) to answer questions and discuss concerns in real time. As with all DEI work, it is important to know where you are starting (having accurate data and a clear understanding of the data) and be able to communicate that data to the group. For example, using AAMC salary benchmarking33 as well as other benchmarks allowed us to accurately calculate variance among salaries and identify the appropriate goal salary for each of our faculty members. Likewise, by completing an in-depth inventory on the work being done by all of our faculty in leadership roles, we were able to standardize the compensation/FTE for each of these roles. Tracking these changes over time, via the use of dashboards in our case, allows for real-time measurements and accountability for all of those involved. Our end goal will be to have all of these initiatives feed into one large dashboard.

Collaborating with leadership and stakeholders in the DOM, SOM, and hospital helped to make our DEI initiatives successful. Much too often, we work in silos when it comes to DEI work. However, we tend to have similar goals and can achieve much more if we work together. Collaboration with multiple stakeholders allowed for wider dissemination and resulted in a larger impact to the campus and community at large. This has been exemplified by the committee composition guidance that has been utilized by the DOM, as well as implementation of campus-wide policies, specifically the parental leave policy, which our faculty members played an important role in creating. Likewise, it is important to look outside of our institutions and work with other hospital medicine groups around the country who are interested in promoting DEI.

We still have much work ahead of us. We are continuing to measure outcomes status postimplementation of the toolkit and checklists being used for diversity recruitment and committee composition. Additionally, we are actively working on several initiatives, including:

- Instituting implicit bias training for all of our faculty

- Partnering with national leaders and our hospital systems to develop zero-tolerance policies regarding abusive behaviors (verbal, physical, and other), racism, and sexism in the hospital and other work settings

- Development of specific recruitment strategies as a means of diversifying our healthcare workforce (of note, based on a 2020 survey of our faculty, in which there was a 70% response rate, 8.5% of our faculty identified as URMs)

- Completion of a diversity dashboard to track our progress in all of these efforts over time

- Development of a more robust pipeline to promotion and leadership for our URM faculty

This study has several strengths. Many of the plans and strategies described here can be used to guide others interested in implementing this work. Figure 2 provides a stepwise

approach to addressing DEI in hospital medicine groups and divisions. We conducted this work at a large academic medical center, and while it may not be generalizable, it does offer some ideas for others to consider in their own work to advance DEI at their institutions. There are also several limitations to this work. Eliminating salary inequities with our approach did take resources. We took advantage of already lower salaries and the need to increase salaries closer to benchmark and paired this effort with our DEI efforts to achieve salary equity. This required partnerships with the department and hospital. Efforts to advance DEI also take a lot of time and effort, and thus commitment from the division, department, and institution as a whole is key. While we have outcomes for our efforts related to salary equity, recruitment efforts should be realized over time, as currently it is too early to tell. We have highlighted the efforts that have been put in place at this time.

CONCLUSION

Using a systematic evidence-based approach with key stakeholder involvement, a division-wide DEI strategy was developed and implemented. While this work is still ongoing, short-term wins are possible, in particular around salary equity and development of policies and structures to promote DEI.

1. Underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. National Institutes of Health website. Accessed December 26, 2020. https://extramural-diversity.nih.gov/diversity-matters/underrepresented-groups

2. Ash AS, Carr PL, Goldstein R, Friedman RH. Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: is there equity? Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(3):205-212. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00009

3. Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1149-1158. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10680

4. Fang D, Moy E, Colburn L, Hurley J. Racial and ethnic disparities in faculty promotion in academic medicine. JAMA. 2000;284(9):1085-1092. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.9.1085

5. Baptiste D, Fecher AM, Dolejs SC, et al. Gender differences in academic surgery, work-life balance, and satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2017;218:99-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.075

6. Hart KL, Perlis RH. Trends in proportion of women as authors of medical journal articles, 2008-2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1285-1287. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0907

7. Thomas EG, Jayabalasingham B, Collins T, Geertzen J, Bui C, Dominici F. Gender disparities in invited commentary authorship in 2459 medical journals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913682. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13682

8. Hechtman LA, Moore NP, Schulkey CE, et al. NIH funding longevity by gender. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(31):7943-7948. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800615115

9. Sege R, Nykiel-Bub L, Selk S. Sex differences in institutional support for junior biomedical researchers. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1175-1177. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.8517

10. Silver JK, Slocum CS, Bank AM, et al. Where are the women? The underrepresentation of women physicians among recognition award recipients from medical specialty societies. PM R. 2017;9(8):804-815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.06.001

11. Ruzycki SM, Fletcher S, Earp M, Bharwani A, Lithgow KC. Trends in the proportion of female speakers at medical conferences in the United States and in Canada, 2007 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2103

12. Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Gender differences in academic medicine: retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the National Faculty Survey. Acad Med. 2018;93(11):1694-1699. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002146

13. Carr PL, Gunn C, Raj A, Kaplan S, Freund KM. Recruitment, promotion, and retention of women in academic medicine: how institutions are addressing gender disparities. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(3):374-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2016.11.003

14. Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294-1304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3284

15. Lo Sasso AT, Richards MR, Chou CF, Gerber SE. The $16,819 pay gap for newly trained physicians: the unexplained trend of men earning more than women. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(2):193-201. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0597

16. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-517. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199608153350713

17. Weaver AC, Wetterneck TB, Whelan CT, Hinami K. A matter of priorities? Exploring the persistent gender pay gap in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):486-490. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2400

18. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

19. Northcutt N, Papp S, Keniston A, et al, Society of Hospital Medicine Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Special Interest Group. SPEAKers at the National Society of Hospital Medicine Meeting: a follow-up study of gender equity for conference speakers from 2015 to 2019. The SPEAK UP Study. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(4):228-231. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3401

20. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(7):393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

21. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Promoting gender equity at the Journal of Hospital Medicine [editorial]. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):517. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3522

22. Sheehy AM, Kolehmainen C, Carnes M. We specialize in change leadership: a call for hospitalists to lead the quest for workforce gender equity [editorial]. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):551-552. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2399

23. Evans MK, Rosenbaum L, Malina D, Morrissey S, Rubin EJ. Diagnosing and treating systemic racism [editorial]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):274-276. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe2021693

24. Rock D, Grant H. Why diverse teams are smarter. Harvard Business Review. Published November 4, 2016. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter

25. Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):101-110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30262.x

26. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competence and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):499-505. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.499

27. Acosta D, Ackerman-Barger K. Breaking the silence: time to talk about race and racism [comment]. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):285-288. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001416

28. Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):90-102. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90

29. Chang E, Simon M, Dong X. Integrating cultural humility into health care professional education and training. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17(2):269-278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9264-1

30. Foronda C, Baptiste DL, Reinholdt MM, Ousman K. Cultural humility: a concept analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(3):210-217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615592677

31. Butkus R, Serchen J, Moyer DV, et al; Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Achieving gender equity in physician compensation and career advancement: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(10):721-723. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3438

32. Burden M, del Pino-Jones A, Shafer M, Sheth S, Rexrode K. GWIMS Equity Recruitment Toolkit. Accessed July 27, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/download/492864/data/equityinrecruitmenttoolkit.pdf

33. AAMC Faculty Salary Report. AAMC website. Accessed September 6, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/aamc-faculty-salary-report

34. Promotion process. University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus website. Accessed September 7, 2020. https://medschool.cuanschutz.edu/faculty-affairs/for-faculty/promotion-and-tenure/promotion-process

35. Pierce RG, Diaz M, Kneeland P. Optimizing well-being, practice culture, and professional thriving in an era of turbulence. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):126-128. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3101

1. Underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. National Institutes of Health website. Accessed December 26, 2020. https://extramural-diversity.nih.gov/diversity-matters/underrepresented-groups

2. Ash AS, Carr PL, Goldstein R, Friedman RH. Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: is there equity? Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(3):205-212. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00009

3. Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1149-1158. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10680

4. Fang D, Moy E, Colburn L, Hurley J. Racial and ethnic disparities in faculty promotion in academic medicine. JAMA. 2000;284(9):1085-1092. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.9.1085

5. Baptiste D, Fecher AM, Dolejs SC, et al. Gender differences in academic surgery, work-life balance, and satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2017;218:99-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.075

6. Hart KL, Perlis RH. Trends in proportion of women as authors of medical journal articles, 2008-2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1285-1287. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0907

7. Thomas EG, Jayabalasingham B, Collins T, Geertzen J, Bui C, Dominici F. Gender disparities in invited commentary authorship in 2459 medical journals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913682. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13682

8. Hechtman LA, Moore NP, Schulkey CE, et al. NIH funding longevity by gender. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(31):7943-7948. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800615115

9. Sege R, Nykiel-Bub L, Selk S. Sex differences in institutional support for junior biomedical researchers. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1175-1177. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.8517

10. Silver JK, Slocum CS, Bank AM, et al. Where are the women? The underrepresentation of women physicians among recognition award recipients from medical specialty societies. PM R. 2017;9(8):804-815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.06.001

11. Ruzycki SM, Fletcher S, Earp M, Bharwani A, Lithgow KC. Trends in the proportion of female speakers at medical conferences in the United States and in Canada, 2007 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2103

12. Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Gender differences in academic medicine: retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the National Faculty Survey. Acad Med. 2018;93(11):1694-1699. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002146

13. Carr PL, Gunn C, Raj A, Kaplan S, Freund KM. Recruitment, promotion, and retention of women in academic medicine: how institutions are addressing gender disparities. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(3):374-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2016.11.003

14. Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294-1304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3284

15. Lo Sasso AT, Richards MR, Chou CF, Gerber SE. The $16,819 pay gap for newly trained physicians: the unexplained trend of men earning more than women. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(2):193-201. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0597

16. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-517. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199608153350713

17. Weaver AC, Wetterneck TB, Whelan CT, Hinami K. A matter of priorities? Exploring the persistent gender pay gap in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):486-490. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2400

18. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

19. Northcutt N, Papp S, Keniston A, et al, Society of Hospital Medicine Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Special Interest Group. SPEAKers at the National Society of Hospital Medicine Meeting: a follow-up study of gender equity for conference speakers from 2015 to 2019. The SPEAK UP Study. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(4):228-231. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3401

20. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(7):393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

21. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Promoting gender equity at the Journal of Hospital Medicine [editorial]. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):517. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3522

22. Sheehy AM, Kolehmainen C, Carnes M. We specialize in change leadership: a call for hospitalists to lead the quest for workforce gender equity [editorial]. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):551-552. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2399

23. Evans MK, Rosenbaum L, Malina D, Morrissey S, Rubin EJ. Diagnosing and treating systemic racism [editorial]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):274-276. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe2021693

24. Rock D, Grant H. Why diverse teams are smarter. Harvard Business Review. Published November 4, 2016. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter

25. Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):101-110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30262.x

26. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competence and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):499-505. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.499

27. Acosta D, Ackerman-Barger K. Breaking the silence: time to talk about race and racism [comment]. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):285-288. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001416

28. Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):90-102. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90

29. Chang E, Simon M, Dong X. Integrating cultural humility into health care professional education and training. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17(2):269-278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9264-1

30. Foronda C, Baptiste DL, Reinholdt MM, Ousman K. Cultural humility: a concept analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(3):210-217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615592677

31. Butkus R, Serchen J, Moyer DV, et al; Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Achieving gender equity in physician compensation and career advancement: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(10):721-723. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3438

32. Burden M, del Pino-Jones A, Shafer M, Sheth S, Rexrode K. GWIMS Equity Recruitment Toolkit. Accessed July 27, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/download/492864/data/equityinrecruitmenttoolkit.pdf

33. AAMC Faculty Salary Report. AAMC website. Accessed September 6, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/aamc-faculty-salary-report

34. Promotion process. University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus website. Accessed September 7, 2020. https://medschool.cuanschutz.edu/faculty-affairs/for-faculty/promotion-and-tenure/promotion-process

35. Pierce RG, Diaz M, Kneeland P. Optimizing well-being, practice culture, and professional thriving in an era of turbulence. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):126-128. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3101

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

You Can’t Have It All: The Experience of Academic Hospitalists During Pregnancy, Parental Leave, and Return to Work

Despite recent advances made in medicine, gender-based disparities persist.1-3 In particular, women with children have barriers to career advancement and show evidence of slower career advancement.1,2 Multiple challenges for working women experiencing motherhood have been described. In academic medicine in the United States, women have limited access to paid parental leave.4-6 For women who choose to breastfeed, there is limited time, space, and support available for breastfeeding.7 Furthermore, sleep deprivation in the postpartum period significantly impacts the ability to function at work.8