User login

Research Agenda for Older Patient Care

Older adults with high levels of medical complexity occupy an increasing fraction of beds in acute‐care hospitals in the United States.[1, 2] By 2007, patients age 65 years and older accounted for nearly half of adult inpatient days of care.[1] These patients are commonly cared for by hospitalists who number more than 40,000.[3] Although hospitalists are most often trained in internal medicine, they have typically received limited formal geriatrics training. Increasingly, access to experts in geriatric medicine is limited.[4] Further, hospitalists and others who practice in acute care are limited by the lack of research to address the needs of the older adult population, specifically in the diagnosis and management of conditions encountered during acute illness.

To better support hospitalists in providing acute inpatient geriatric care, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) partnered with the Association of Specialty Professors to develop a research agenda to bridge this gap. Using methodology from the James Lind Alliance (JLA) and the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), the SHM joined with older adult advocacy groups, professional societies of providers, and funders to create a geriatric‐focused acute‐care research agenda, highlighting 10 key research questions.[5, 6, 7] The goal of this approach was to produce and promote high integrity, evidence‐based information that comes from research guided by patients, caregivers, and the broader healthcare community.[8] In this article, we describe the methodology and results of this agenda‐setting process, referred to as the Acute Care of Older Patients (ACOP) Priority Setting Partnership.

METHODS

Overview

This project focused on topic generation, the first step in the PCORI framework for identification and prioritization of research areas.[5] We employed a specific and defined methodology to elicit and prioritize potential research topics incorporating input from representatives of older patients, family caregivers, and healthcare providers.[6]

To elicit this input, we chose a collaborative and consultative approach to stakeholder engagement, drawing heavily from the published work of the JLA, an initiative promoting patient‐clinician partnerships in health research developed in the United Kingdom.[6] We previously described the approach elsewhere.[7]

The ACOP process for determining the research agenda consisted of 4 steps: (1) convene, (2) consult, (3) collate, and (4) prioritize.[6] Through these steps, detailed below, we were able to obtain input from a broad group of stakeholders and engage the stakeholders in a process of reducing and refining our research questions.

Convene

The steering committee (the article's authors) convened a stakeholder partnership group that included stakeholders representing patients and caregivers, advocacy organizations for the elderly, organizations that address diseases and conditions common among hospitalized older patients, provider professional societies (eg, hospitalists, subspecialists, and nurses and social workers), payers, and funders. Patient, caregiver, and advocacy organizations were identified based on their engagement in aging and health policy advocacy by SHM staff and 1 author who had completed a Health and Aging Policy Fellowship (H.L.W.).

The steering committee issued e‐mail invitations to stakeholder organizations, making initial inquiries through professional staff and relevant committee chairs. Second inquiries were made via e‐mail to each organization's volunteer leadership. We developed a webinar that outlined the overall research agenda setting process and distributed the webinar to all stakeholders. The stakeholder organizations were asked to commit to (1) surveying their memberships and (2) participating actively in prioritization by e‐mail and at a 1‐day meeting in Washington DC.

Consult

Each stakeholder organization conducted a survey of its membership via an Internet‐based survey in the summer of 2013 (see Supporting Information, Appendix A, in the online version of this article). Stakeholder organizations were asked to provide up to 75 survey responses each. Though a standard survey was used, the steering committee was not prescriptive in the methodology of survey distribution to accommodate the structure and communication methods of the individual stakeholder organizations. Survey respondents were asked to identify up to 5 unanswered questions relevant to the acute care of older persons and also provide demographic information.

Collate

In the collating process, we clarified and categorized the unanswered questions submitted in the individual surveys. Each question was initially reviewed by a member of the steering committee, using explicit criteria (see Supporting Information, Appendix B, in the online version of this article). Questions that did not meet all 4 criteria were removed. For questions that met all criteria, we clarified language, combined similar questions, and categorized each question. Categories were created in a grounded process, in which individual reviewers assigned categories based on the content of the questions. Each question could be assigned to up to 2 categories. Each question was then reviewed by a second member of the steering committee using the same 4 criteria. As part of this review, similar questions were consolidated, and when possible, questions were rewritten in a standard format.[6]

Finally, the steering committee reviewed previously published research agendas looking for additional relevant unanswered questions, specifically the New Frontiers Research Agenda created by the American Geriatrics Society in conjunction with participating subspecialty societies,[9] the Cochrane Library, and other systematic reviews identified in the literature via PubMed search.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

Prioritize

The resulting list of unanswered questions was prioritized in 2 phases. First, the list was e‐mailed to all stakeholder organizations. The organizations were asked to vote on their top 10 priorities from this list using an online ballot, assigning 10 points to their highest priority down to 1 point for their lowest priority. In so doing, they were asked to consider explicit criteria (see Supporting Information, Appendix B, in the online version of this article). Each organization had only 1 ballot and could arrive at their top 10 list in any manner they wished. The balloting from this phase was used to develop a list of unanswered questions for the second round of in‐person prioritization. Each priority's scores were totaled across all voting organizations. The 29 priorities with the highest point totals were brought to the final prioritization round because of a natural cut point at priority number 29, rather than number 30.

For the final prioritization round, the steering committee facilitated an in‐person meeting in Washington, DC in October 2013 using nominal group technique (NGT) methodologies to arrive at consensus.[16] During this process stakeholders were asked to consider additional criteria (see Supporting Information, Appendix B, in the online version of this article).

RESULTS

Table 1 lists the organizations who engaged in 1 or more parts of the topic generation process. Eighteen stakeholder organizations agreed to participate in the convening process. Ten organizations did not respond to our solicitation and 1 declined to participate.

| Organization (N=18) | Consultation % of Survey Responses (N=580) | Prioritization Round 1 | Prioritization Round 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Association | 7.0% | Yes | Yes |

| American Academy of Neurology | 3.4% | Yes | Yes |

| American Association of Retired Persons | 0.8% | No | No |

| American College of Cardiology | 11.4% | Yes | Yes |

| American College of Emergency Physicians | 1.3% | No | No |

| American College of Surgeons | 1.0% | Yes | Yes |

| American Geriatrics Society | 7.6% | Yes | Yes |

| American Hospital Association | 1.7% | Yes | No |

| Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services | 0.8% | Yes | Yes |

| Gerontological Society of America | 18.9% | Yes | Yes |

| National Alliance for Caregiving | 1.0% | Yes | Yes |

| National Association of Social Workers | 5.9% | Yes | Yes |

| National Coalition for Healthcare | 0.6% | No | No |

| National Institute on Aging | 2.1% | Yes | Yes |

| National Partnership for Women and Families | 0.0% | Yes | Yes |

| Nursing Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders | 28.6% | Yes | No |

| Society of Critical Care Medicine | 12.0% | Yes | Yes |

| Society of Hospital Medicine | 4.6% | Yes | Yes |

Seventeen stakeholder organizations obtained survey responses from a total of 580 individuals (range, 3150 per organization), who were asked to identify important unanswered questions in the acute care of older persons. Survey respondents were typically female (77%), white (85%), aged 45 to 65 years (65%), and identified themselves as health professionals (90%). Twenty‐six percent of respondents also identified as patients or family caregivers. Their surveys included 1299 individual questions.

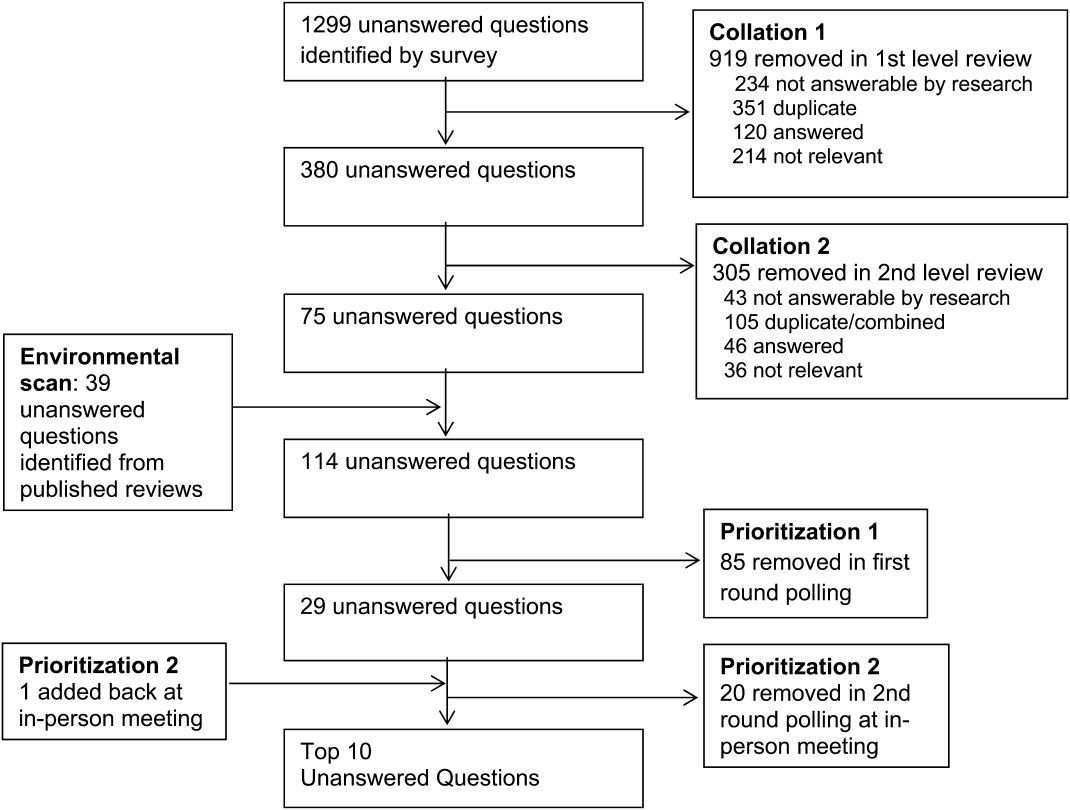

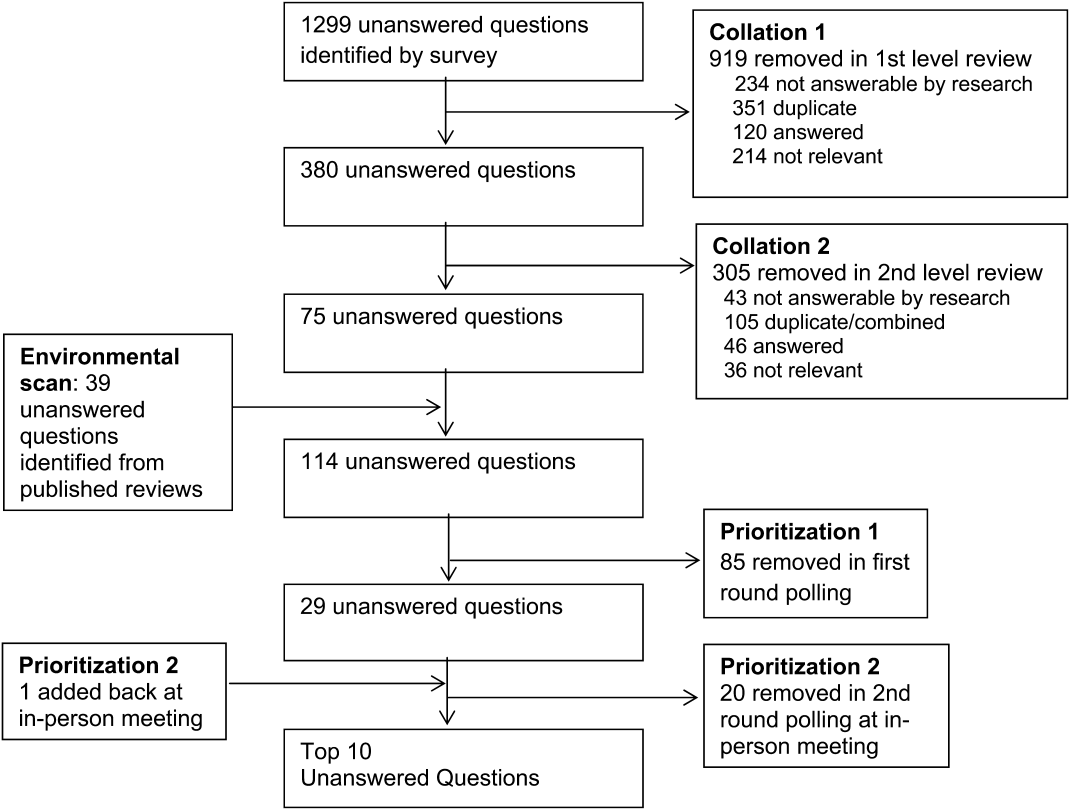

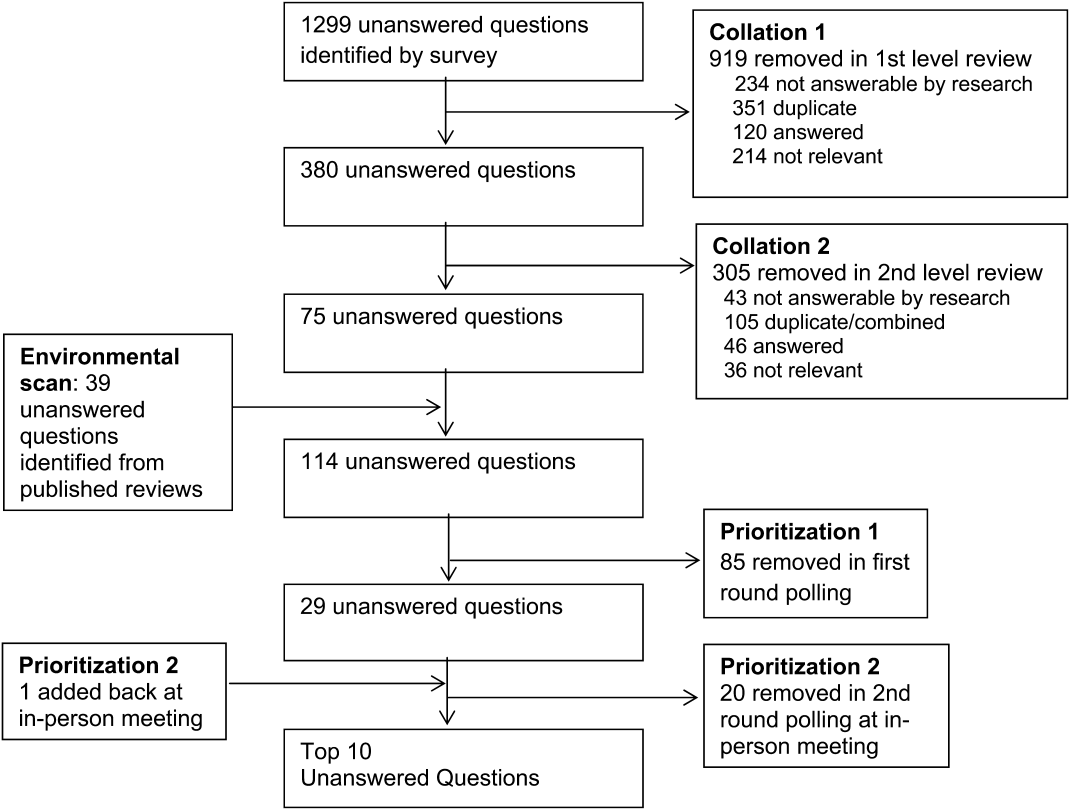

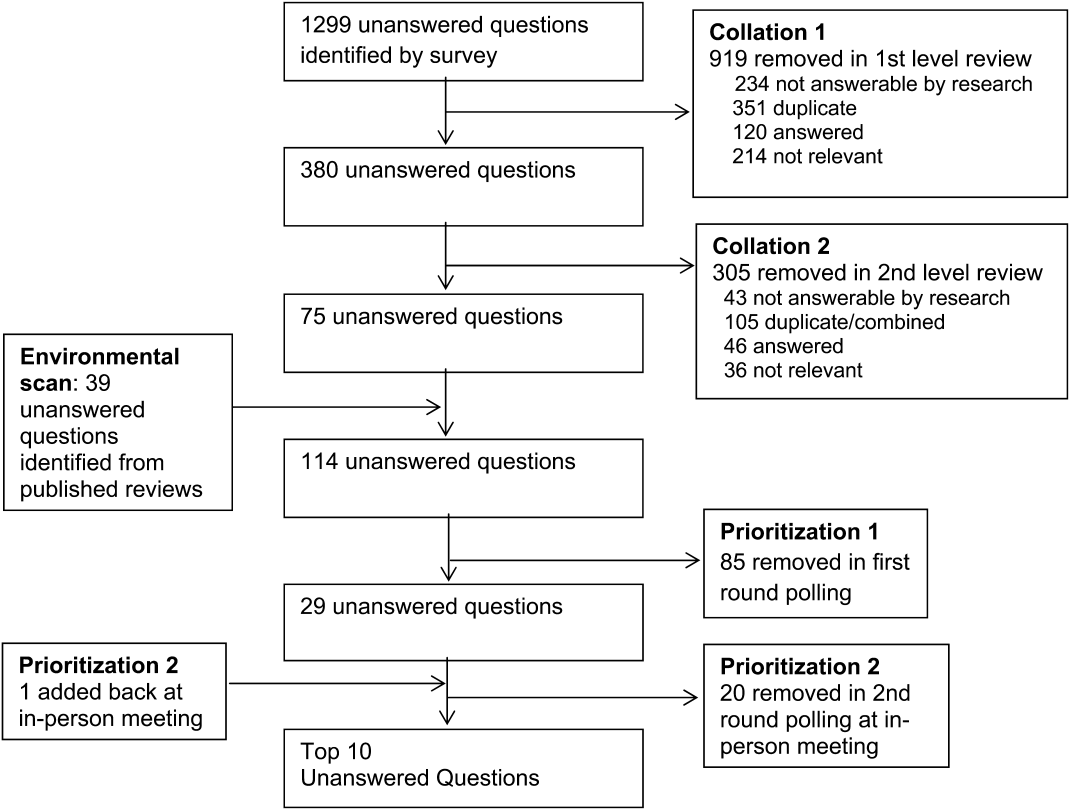

Figure 1 summarizes our collation and prioritization process and reports the numbers of questions resulting at each stage. Nine hundred nineteen questions were removed during the first review conducted by steering committee members, and 31 question categories were identified. An additional 305 questions were removed in the second review, with 75 questions remaining. As the final step of the collating process, literature review identified 39 relevant questions not already suggested or moved forward through our consultation and collation process. These questions were added to the list of unanswered questions.

In the first round of prioritization, this list of 114 questions was emailed to each stakeholder organization (Table 1). After the stakeholder voting process was completed, 29 unanswered questions remained (see Supporting Information, Appendix C, in the online version of this article). These questions were refined and prioritized in the in‐person meeting to create the final list of 10 questions. The stakeholders present in the meeting represented 13 organizations (Table 1). Using the NGT with several rounds of small group breakouts and large group deliberation, 9 of the top 10 questions were selected from the list of 29. One additional highly relevant question that had been removed earlier in the collation process regarding workforce was added back by the stakeholder group.

This prioritized research agenda appears in Table 2 and below, organized alphabetically by topic.

- Advanced care planning: What approaches for determining and communicating goals of care across and within healthcare settings are most effective in promoting goal‐concordant care for hospitalized older patients?

- Care transitions: What is the comparative effectiveness of transitional care models on patient‐centered outcomes for hospitalized older adults?

- Delirium: What practices are most effective for consistent recognition, prevention, and treatment of delirium subtypes among hospitalized older adults?

- Dementia: Does universal assessment of hospitalized older adults for cognitive impairment (eg, at presentation and/or discharge) lead to more appropriate application of geriatric care principles and improve patient‐centered outcomes?

- Depression: Does identifying depressive symptoms during a hospital stay and initiating a therapeutic plan prior to discharge improve patient‐centered and/or disease‐specific outcomes?

- Medications: What systems interventions improve medication management for older adults (ie, appropriateness of medication choices and dosing, compliance, cost) in the hospital and postacute care?

- Models of care: For which populations of hospitalized older adults does systematic implementation of geriatric care principles/processes improve patient‐centered outcomes?

- Physical function: What is the comparative effectiveness of interventions that promote in‐hospital mobility, improve and preserve physical function, and reduce falls among older hospitalized patients?

- Surgery: What perioperative strategies can be used to optimize care processes and improve outcomes in older surgical patients?

- Training: What is the most effective approach to training hospital‐based providers in geriatric and palliative care competencies?

| Topic | Scope of Problem | What Is known | Unanswered Question | Proposed Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Advanced‐care planning | Older persons who lack decision‐making capacity often do not have surrogates or clear goals of care documented.[19] Advanced‐care directives are associated with an increase in patient autonomy and empowerment, and although 15% to 25% of adults completed the documentation in 2004,[20] a recent study found completion rates have increased to 72%.[21] | Nursing home residents with advanced directives are less likely to be hospitalized.[22, 23] Advanced directive tools, such as POLST, work to translate patient preferences to medical order.[24] standardized patient transfer tools may help to improve transitions between nursing homes and hospitals.[25] However, advanced care planning fails to integrate into courses of care if providers are unwilling or unskilled in using advanced care documentation.[26] | What approaches for determining and communicating goals of care across and within healthcare settings are most effective in promoting goal‐concordant care for hospitalized older patients? | Potential interventions: |

| Decision aids | ||||

| Standard interdisciplinary advanced care planning approach | ||||

| Patient advocates | ||||

| Potential outcomes might include: | ||||

| Completion of advanced directives and healthcare power of attorney | ||||

| Patient‐centered outcomesa | ||||

| Care transitions | Hospital readmission from home and skilled nursing facilities occurs within 30 days in up to a quarter of patients.[27, 28] The discharge of complex older hospitalized patients is fraught with challenges. The quality of the hospital discharge process can influence outcomes for vulnerable older patients.[29, 30, 31, 32] Studies measuring the quality of hospital discharge frequently find deficits in documentation of assessment of geriatric syndromes,[33] poor patient/caregiver understanding,[34, 35] and poor communication and follow‐up with postacute providers.[35, 36, 37, 38] | As many as 10 separate domains may influence the success of a discharge.[39] There is limited evidence, regarding quality‐of‐care transitions for hospitalized older patients. The Coordinated‐Transitional Care Program found that follow‐up with telecommunication decreased readmission rates and improved transitional care for a high‐risk condition veteran population.[40] There is modest evidence for single interventions,[41] whereas the most effective hospital‐to‐community care interventions address multiple processes in nongeriatric populations.[39, 42, 43] | What is the comparative effectiveness of the transitional care models on patient‐centered outcomes for hospitalized older adults? | Possible models: |

| Established vs novel care‐transition models | ||||

| Disease‐specific vs general approaches | ||||

| Accountable care models | ||||

| Caregiver and family engagement | ||||

| Community engagement | ||||

| Populations of interest: | ||||

| Patients with dementia | ||||

| Patients with multimorbidity | ||||

| Patients with geriatric syndromes | ||||

| Patients with psychiatric disease | ||||

| Racially and ethnically diverse patients | ||||

| Outcomes: | ||||

| Readmission | ||||

| Other adverse events | ||||

| Cost and healthcare utilization | ||||

| Patient‐centered outcomesa | ||||

| Delirium | Among older inpatients, the prevalence of delirium varies with severity of illness. Among general medical patients, in‐hospital prevalence ranges from 10% to 25 %.[44, 45] In the ICU, prevalence estimates are higher, ranging from 25% to as high as 80%.[46, 47] Delirium independently predicts increased length of stay,[48, 49] long‐term cognitive impairment,[50, 51] functional decline,[51] institutionalization,[52] and short‐ and long‐term mortality.[52, 53, 54] | Multicomponent strategies have been shown to be effective in preventing delirium. A systematic review of 19 such interventions identified the most commonly included such as[55]: early mobilization, nutrition supplements, medication review, pain management, sleep enhancement, vision/hearing protocols, and specialized geriatric care. Studies have included general medical patients, postoperative patients, and patients in the ICU. The majority of these studies found reductions in either delirium incidence (including postoperative), delirium prevalence, or delirium duration. Although medications have not been effective in treating delirium in general medical patients,[48] the choice and dose of sedative agents has been shown to impact delirium in the ICU.[56, 57, 58] | What practices are most effective for consistent recognition, prevention, and treatment of delirium subtypes (hypoactive, hyperactive, and mixed) among hospitalized older adults? | Outcomes to examine: |

| Delirium incidence (including postoperative) | ||||

| Delirium duration | ||||

| Delirium‐/coma‐free days | ||||

| Delirium prevalence at discharge | ||||

| Subsyndromal delirium | ||||

| Potential prevention and treatment modalities: | ||||

| Family education or psychosocial interventions | ||||

| Pharmacologic interventions | ||||

| Environmental modifications | ||||

| Possible areas of focus: | ||||

| Special populations | ||||

| Patients with varying stages of dementia | ||||

| Patients with multimorbidity | ||||

| Patients with geriatric syndromes | ||||

| Observation patients | ||||

| Diverse settings | ||||

| Emergency department | ||||

| Perioperative | ||||

| Skilled nursing/rehab/long‐term acute‐care facilities | ||||

| Dementia | 13% to 63% of older persons in the hospital have dementia.[59] Dementia is often unrecognized among hospitalized patients.[60] The presence of dementia is associated with a more rapid functional decline during admission and delayed hospital discharge.[59] Patients with dementia require more nursing hours, and are more likely to have complications[61] or die in care homes rather than in their preferred site.[59] | Several tools have been validated to screen for dementia in the hospital setting.[62] Studies have assessed approaches to diagnosing delirium in hospitalized patients with dementia.[63] Cognitive and functional stimulation interventions may have a positive impact on reducing behavioral issues.[64, 65] | Does universal assessment of hospitalized older adults for cognitive impairment (eg, at presentation and/or discharge) lead to more appropriate application of geriatric care principles and improve patient centered outcomes? | Potential interventions: |

| Dementia or delirium care | ||||

| Patient/family communication and engagement strategies | ||||

| Maintenance/recovery of independent functional status | ||||

| Potential outcomes: | ||||

| Patient‐centered outcomesa | ||||

| Length of stay, cost, and healthcare utilization (including palliative care) | ||||

| Immediate invasive vs early conservative treatments pursued | ||||

| Depression | Depression is a common geriatric syndrome among acutely ill older patients, occurring in up to 45% of patients.[66, 67] Rates of depression are similar among patients discharged following a critical illness, with somatic, rather than cognitive‐affective complaints being the most prevalent.[68] Depression among inpatients or immediately following hospitalization independently predicts worse functional outcomes,[69] cognitive decline,[70] hospital readmission,[71, 72] and long‐term mortality.[69, 73] Finally, geriatric patients are known to respond differently to medical treatment.[74, 75] | Although highly prevalent, depression is poorly recognized and managed in the inpatient setting. Depression is recognized in only 50% of patients, with previously undiagnosed or untreated depression being at highest risk for being missed.[76] The role of treatment of depression in the inpatient setting is poorly understood, particularly for those with newly recognized depression or depressive symptoms. Some novel collaborative care and telephone outreach programs have led to increases in depression treatment in patients with specific medical and surgical conditions, resulting in early promising mental health and comorbid outcomes.[77, 78] The efficacy of such programs for older patients is unknown. | Does identifying depressive symptoms during a hospital stay and initiating a therapeutic plan prior to discharge improve patient‐centered and/or disease‐specific outcomes? | Possible areas of focus: |

| Comprehensive geriatric and psychosocial assessment; | ||||

| Inpatient vs outpatient initiation of pharmacological therapy | ||||

| Integration of confusion assessment method into therapeutic approaches | ||||

| Linkages with outpatient mental health resources | ||||

| Medications | Medication exposure, particularly potentially inappropriate medications, is common in hospitalized elders.[79] Medication errorsof dosage, type, and discrepancy between what a patient takes at home and what is known to his/her prescribing physicianare common and adversely affects patient safety.[80] Geriatric populations are disproportionately affected, especially those taking more than 5 prescription medications per day.[81] | Numerous strategies including electronic alerts, screening protocols, and potentially inappropriate medication lists (Beers list, STOPP) exist, though the optimal strategies to limit the use of potentially inappropriate medications is not yet known.[82, 83, 84] | What systems interventions improve medication management for older adults (ie, appropriateness of medication choices and dosing, compliance, cost) in hospital and post‐acute care? | Possible areas of focus: |

| Use of healthcare information technology | ||||

| Communication across sites of care | ||||

| Reducing medication‐related adverse events | ||||

| Engagement of family caregivers | ||||

| Patient‐centered strategies to simplify regimens | ||||

| Models of care | Hospitalization marks a time of high risk for older patients. Up to half die during hospitalization or within the year following the hospitalization. There is high risk of nosocomial events, and more than a third experience a decline in health resulting in longer hospitalizations and/or placement in extended‐care facilities.[73, 85, 86] | Comprehensive inpatient care for older adults (acute care for elders units, geriatric evaluation and management units, geriatric consultation services) were studied in 2 meta‐analyses, 5 RCTs, and 1 quasiexperimental study and summarized in a systematic review.[87] The studies reported improved quality of care (1 of 1 article), quality of life (3 of 4), functional autonomy (5 of 6), survival (3 of 6), and equal or lower healthcare utilization (7 of 8). | For which populations of hospitalized older adults does systematic implementation of geriatric care principles/processes improve patient‐centered outcomes? | Potential populations: |

| Patients of the emergency department, critical care, perioperative, and targeted medical/surgical units | ||||

| Examples of care principles: | ||||

| Geriatric assessment, early mobility, medication management, delirium prevention, advanced‐care planning, risk‐factor modification, caregiver engagement | ||||

| Potential outcomes: | ||||

| Patient‐centered outcomesa | ||||

| Cost | ||||

| Physical function | Half of older patients will lose functional capacity during hospitalization.[88] Loss of physical function, particularly of lower extremities, is a risk factor for nursing home placement.[89, 90] Older hospitalized patients spend the majority (up to 80%) of their time lying in bed, even when they are capable of walking independently.[91] | Loss of independences with ADL capabilities is associated with longer hospital stays, higher readmission rates, and higher mortality risk.[92] Excessive time in bed during a hospital stay is also associated with falls.[93] Often, hospital nursing protocols and physician orders increase in‐hospital immobility in patients.[91, 94] However, nursing‐driven mobility protocols can improve functional outcomes of older hospitalized patients.[95, 96] | What is the comparative effectiveness of interventions that promote in‐hospital mobility, improve and preserve physical function, and reduce falls among older hospitalized patients? | Potential interventions: |

| Intensive physical therapy | ||||

| Incidental functional training | ||||

| Restraint reduction | ||||

| Medication management | ||||

| Potential outcomes: | ||||

| Discharge location | ||||

| Delirium, pressure ulcers, and falls | ||||

| Surgery | An increasing number of persons over age 65 years are undergoing surgical procedures.[97] These persons are at increased risk for developing delirium/cogitative dysfunction,[98] loss of functional status,[99] and exacerbations of chronic illness.[97] Additionally, pain management may be harder to address in this population.[100] Current outcomes may not reflect the clinical needs of elder surgical patients.[101] | Tailored drug selection and nursing protocols may prevent delirium.[98] Postoperative cognitive dysfunction may require weeks for resolution. Identifying frail patients preoperatively may lead to more appropriate risk stratification and improved surgical outcomes.[99] Pain management strategies focused on mitigating cognitive impact and other effects may also be beneficial.[100] Development of risk‐adjustment tools specific to older populations, as well as measures of frailty and patient‐centered care, have been proposed.[101] | What perioperative strategies can be used to optimize care processes and improve outcomes in older surgical patients? | Potential strategies: |

| Preoperative risk assessment and optimization for frail or multimorbid older patients | ||||

| Perioperative management protocols for frail or multimorbid older patients | ||||

| Potential outcomes: | ||||

| Postoperative patient centered outcomesa | ||||

| Perioperative cost, healthcare utilization | ||||

| Training | Adults over age 65 years comprise 13.2 % of the US population, but account for >30% of hospital discharges and 50% of hospital days.[86, 102, 103] By 2030, there will only be 1 geriatrician for every 3798 Americans >75 years.[4] Between 1997 and 2006, the odds that a hospitalist would treat a hospitalized Medicare patient rose 29% per year.[3] | Train the trainer programs for physicians include the CHAMP, the AGESP, and the PAGE. Education for nurses include the NICHE. Outcomes include improved self‐confidence, attitudes, teaching skills, and geriatric care environment.[104, 105, 106] | What is the most effective approach to training hospital‐based providers in geriatric and palliative care competencies? | Potential interventions: |

| Mentored implementation | ||||

| Train the trainer | ||||

| Technical support | ||||

Table 2 also contains a capsule summary of the scope of the problem addressed by each research priority, a capsule summary of related work in the content area (what is known) not intended as a systematic review, and proposed dimensions or subquestions suggested by the stakeholders at the final prioritization meeting

DISCUSSION

Older hospitalized patients account for an increasing number and proportion of hospitalized patients,[1, 2] and hospitalists increasingly are responsible for inpatient care for this population.[3] The knowledge required for hospitalists to deliver optimal care and improve outcomes has not kept pace with the rapid growth of either hospitalists or hospitalized elders. Through a rigorous prioritization process, we identified 10 areas that deserve the highest priority in directing future research efforts to improve care for the older hospitalized patient. Assessment, prevention, and treatment of geriatric syndromes in the hospital account for almost half of the priority areas. Additional research is needed to improve advanced care planning, develop new care models, and develop training models for future hospitalists competent in geriatric and palliative care competencies.

A decade ago, the American Geriatric Society and the John A. Hartford Foundation embarked upon a research agenda aimed at improving the care of hospitalized elders cared for by specialists (ie, New Frontiers in Geriatrics Research: An Agenda for Surgical and Related Medical Specialties).[9] This effort differed in many important ways from the current priortization process. First, the New Frontiers agenda focused upon specific diseases, whereas the ACOP agenda addresses geriatric syndromes that cut across multiple diseases. Second, the New Frontiers agenda was made by researchers and based upon published literature, whereas the ACOP agenda involved the input of multiple stakeholders. Finally, the New Frontiers prioritized a research agenda across a number of surgical specialties, emergency medicine, and geriatric rehabilitation. Hospital medicine, however, was still early in its development and was not considered a unique specialty. Since that time, hospital medicine has matured into a unique specialty, with increased numbers of hospitalists,[3] increased research in hospital medicine,[17] and a separate recertification pathway for internal medicine licensure.[18] To date, there has not been a similar effort performed to direct geriatric research efforts for hospital medicine.

For researchers working in the field of hospital medicine, this list of topics has several implications. First, as hospitalists are commonly generalists, hospitalist researchers may be particularly well‐suited to study syndromes that cut across specialties. However, this does raise concerns about funding sources, as most National Institutes of Health institutes are disease‐focused. Funders that are not disease‐focused such as PCORI, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and private foundations (Hartford, Robert Wood Johnson, and Commonwealth) may be more fruitful sources of funding for this work, but funding may be challenging. Nonetheless, the increased focus on patient‐centered work may increase funders' interest in such work. Second, the topics on this list would suggest that interventions will not be pharmacologic, but will focus on nonpharmacologic, behavioral, and social interventions. Similarly, outcomes of interest must expand beyond utilization metrics such as length of stay and mortality, to include functional status and symptom management, and goal‐concordant care. Therefore, research in geriatric acute care will necessarily be multidisciplinary.

Although these 10 high‐priority areas have been selected, this prioritized list is inherently limited by our methodology. First, our survey question was not focused on a disease state, and this wording may have resulted in the list favoring geriatric syndromes rather than common disease processes. Additionally, the resulting questions encompass large research areas and not specific questions about discrete interventions. Our results may also have been skewed by the types of engaged respondents who participated in the consultation, collating, and prioritization phases. In particular, we had a large response from geriatric medicine nurses, whereas some stakeholder groups provided no survey responses. Thus, these respondents were not representative of all possible stakeholders, nor were the survey respondents necessarily representative of each of their organizations. Nonetheless, the participants self‐identified as representative of diverse viewpoints that included patients, caregivers, and advocacy groups, with the majority of stakeholder organizations remaining engaged through the completion of the process. Thus, the general nature of this agenda helps us focus upon larger areas of importance, leaving researchers the flexibility to choose to narrow the focus on a specific research question that may include potential interventions and unique outcomes. Finally, our methodology may have inadvertently limited the number of patient and family caregiver voices in the process given our approach to large advocacy groups, our desire to be inclusive of healthcare professional organizations, and our survey methodology. Other methodologies may have reached more patients and caregivers, yet many healthcare professionals have served as family caregivers to frail elders requiring hospitalization and may have been in an ideal position to answer the survey.

In conclusion, several forces are shaping the future of acute inpatient care. These include the changing demographics of the hospitalized patient population, a rapid increase in the proportion of multimorbid hospitalized older adults, an inpatient workforce (hospitalists, generalists, and subspecialists) with potentially limited geriatrics training, and gaps in evidence‐based guidance to inform diagnostic and therapeutic decision making for acutely ill older patients. Training programs in hospital medicine should be aware of and could benefit from the resulting list of unanswered questions. Our findings also have implications for training to enrich education in geriatrics. Moreover, there is growing recognition that patients and other stakeholders deserve a greater voice in determining the direction of research. In addition to efforts to improve patient‐centeredness of research, these areas have been uniquely identified by stakeholders as important, and therefore are in line with newer priorities of PCORI. This project followed a road map resulting in a patient‐centered research agenda at the intersection of hospital medicine and geriatric medicine.[7] In creating this agenda, we relied heavily on the framework proposed by PCORI. We propose to pursue a dissemination and evaluation strategy for this research agenda as well as additional prioritization steps. We believe the adoption of this methodology will create a knowledge base that is rigorously derived and most relevant to the care of hospitalized older adults and their families. Its application will ultimately result in improved outcomes for hospitalized older adults.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Claudia Stahl, Society of Hospital Medicine; Cynthia Drake, University of Colorado; and the ACOP stakeholder organizations.

Disclosures: This work was supported by the Association of Specialty Professors/American Society of Internal Medicine and the John A. Hartford Foundation. Dr. Vasilevskis was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23AG040157 and the Veterans Affairs Clinical Research Center of Excellence, and the Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC). Dr. Vasilevskis' institution receives grant funding for an aspect of submitted work. Dr. Meltzer is a PCORI Methodology Committee member. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Department of Veterans' Affairs. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , . National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2007 summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010(29):1–20, 24.

- Centers for Medicare 2012. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research‐Statistics‐Data‐and‐Systems/Statistics‐Trends‐and‐Reports/Chronic‐Conditions/Downloads/2012Chartbook.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- , , , . Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- , . A revelation of numbers: will America's eldercare workforce be ready to care for an aging America? Generations. 2010;34(4):11–19.

- Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute Methodology Committee. The PCORI methodology report. Available at: http://www.pcori.org/assets/2013/11/PCORI‐Methodology‐Report.pdf. Published November 2013. Accessed December 19, 2013.

- The James Lind Alliance. JLA method. Available at: http://www.lindalliance.org/JLA_Method.asp. Accessed December 19, 2013.

- , , , , . Road map to a patient‐centered research agenda at the intersection of hospital medicine and geriatric medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):926–931.

- Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute. About us. Available at: http://www.pcori.org/about‐us. Accessed February 23, 2015.

- , , . New Frontiers of Geriatrics Research: An Agenda for Surgical and Related Medical Specialties. New York, NY: American Geriatrics Society; 2004.

- , , , . Linking the NIH strategic plan to the research agenda for social workers in health and aging. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2010;53(1):77–93.

- , . Assessing the capacity to make everyday decisions: a guide for clinicians and an agenda for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(2):101–111.

- , , , et al. Practitioners' views on elder mistreatment research priorities: recommendations from a Research‐to‐Practice Consensus conference. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2011;23(2):115–126.

- , . The intersection between geriatrics and palliative care: a call for a new research agenda. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(9):1593–1598.

- . The cancer aging interface: a research agenda. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(14):1945–1948.

- , , , . Clinical care of persons with dementia in the emergency department: a review of the literature and agenda for research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(9):1742–1748.

- , . A group process model for problem identification and program planning. J Appl Behav Sci. 1971;7(4):466–492.

- , , , , . Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148–154.

- . ABFM and ABIM to jointly participate in recognition of focused practice (rfp) in hospital medicine pilot approved by abms. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(1):87.

- , , , . Medical decision‐making for older adults without family. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(11):2144–2150.

- , , , , , . Promoting advance directives among elderly primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(9):944–951.

- , , . Advance directive completion by elderly Americans: a decade of change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):706–710.

- , . Care transitions by older adults from nursing homes to hospitals: implications for long‐term care practice, geriatrics education, and research. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(4):231–238.

- , , , . Decisions to hospitalize nursing home residents dying with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1396–1401.

- , , , , , . A comparison of methods to communicate treatment preferences in nursing facilities: traditional practices versus the physician orders for life‐sustaining treatment program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(7):1241–1248.

- , , , , . Interventions to improve transitional care between nursing homes and hospitals: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):777–782.

- , , . Opening end‐of‐life discussions: how to introduce Voicing My CHOiCES, an advance care planning guide for adolescents and young adults [published online ahead of print March 13, 2014]. Palliat Support Care. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514000054.

- , , , . The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1):57–64.

- , , . Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee‐for‐service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428.

- , , , et al. Predictors of rehospitalization among elderly patients admitted to a rehabilitation hospital: the role of polypharmacy, functional status, and length of stay. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(10):761–767.

- , , , et al. Mobility after hospital discharge as a marker for 30‐day readmission. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(7):805–810.

- , , , , . The association between the quality of inpatient care and early readmission: a meta‐analysis of the evidence. Med Care. 1997;35(10):1044–1059.

- , , , , , . Association of impaired functional status at hospital discharge and subsequent rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. May 2014;9(5):277–282.

- , , , , , . A prospective cohort study of geriatric syndromes among older medical patients admitted to acute care hospitals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2001–2008.

- , , , et al. Hospital discharge instructions: comprehension and compliance among older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(11):1491–1498.

- , , , et al. Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):385–391.

- , , , et al. Communication and information deficits in patients discharged to rehabilitation facilities: an evaluation of five acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):E28–E33.

- , , , , , . The consequences of poor communication during transitions from hospital to skilled nursing facility: a qualitative study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1095–1102.

- , , , , , . Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , . Moving beyond readmission penalties: creating an ideal process to improve transitional care. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(2):102–109.

- , , , et al. Low‐cost transitional care with nurse managers making mostly phone contact with patients cut rehospitalization at a VA hospital. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(12):2659–2668.

- , , , et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(11):774–784.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , , , . Hospital‐initiated transitional care interventions as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 pt 2):433–440.

- , , , . Epidemiology and risk factors for delirium across hospital settings. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2012;26(3):277–287.

- , , , , . Does delirium contribute to poor hospital outcomes? A three‐site epidemiologic study. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(4):234–242.

- , , , . Incidence, risk factors and consequences of ICU delirium. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(1):66–73.

- , , , et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM‐ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–2710.

- , , , et al. Impact and recognition of cognitive impairment among hospitalized elders. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(2):69–75.

- , , , et al. The impact of delirium in the intensive care unit on hospital length of stay. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(12):1892–1900.

- , , . Long‐term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(2):185–186.

- , , , et al. Delirium in the ICU and subsequent long‐term disability among survivors of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):369–377.

- , , , , , . Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta‐analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443–451.

- , , , et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1753–1762.

- , , , , , . Days of delirium are associated with 1‐year mortality in an older intensive care unit population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(11):1092–1097.

- , . In‐facility delirium prevention programs as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 pt 2):375–380.

- , , , et al. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for sedation of critically ill patients: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(5):489–499.

- , , , et al. Effect of sedation with dexmedetomidine vs lorazepam on acute brain dysfunction in mechanically ventilated patients: the MENDS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2644–2653.

- , , , , , . Protocolized intensive care unit management of analgesia, sedation, and delirium improves analgesia and subsyndromal delirium rates. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(2):451–463.

- , . A systematic review of the prevalence, associations and outcomes of dementia in older general hospital inpatients. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(3):344–355.

- , , , . Cognitive impairment is undetected in medical inpatients: a study of mortality and recognition amongst healthcare professionals. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:47.

- , , . How can we keep patients with dementia safe in our acute hospitals? A review of challenges and solutions. J R Soc Med. 2013;106(9):355–361.

- , , . Screening for dementia in general hospital inpatients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of available instruments. Age Ageing. 2013;42(6):689–695.

- , , , et al. Tools to detect delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(11):2005–2013.

- , , , , , . Functional analysis‐based interventions for challenging behaviour in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD006929.

- , , , . Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD005562.

- , , , et al. The prevalence and correlates of major and minor depression in older medical inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1344–1353.

- , , , , , . Major depressive disorder in hospitalized medically ill patients: an examination of young and elderly male veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(9):881–890.

- , , , et al. Depression, post‐traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN‐ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(5):369–379.

- , , , et al. Depressive symptoms after hospitalization in older adults: function and mortality outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(12):2254–2262.

- , , , , . 12‐month cognitive outcomes of major and minor depression in older medical patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(9):742–751.

- , , , et al. Depression is a risk factor for rehospitalization in medical inpatients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(4):256–262.

- , , , , , . Dose‐response relationship between depressive symptoms and hospital readmission. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(6):358–364.

- , , , , , . Depressive symptoms and 3‐year mortality in older hospitalized medical patients. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(7):563–569.

- , , , et al. Support for the vascular depression hypothesis in late‐life depression: results of a 2‐site, prospective, antidepressant treatment trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):277–285.

- , , , , , . Executive dysfunction and the course of geriatric depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(3):204–210.

- , , , , . Recognition of depression in older medical inpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(5):559–564.

- , , , , , . A collaborative care depression management program for cardiac inpatients: depression characteristics and in‐hospital outcomes. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(1):26–33.

- , , , , , . Impact of a depression care management program for hospitalized cardiac patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(2):198–205.

- , , , et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in hospitalized elders. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(2):91–102.

- , , , , , . Prevalence, incidence and nature of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2009;32(5):379–389.

- , . Minimizing adverse drug events in older patients. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(12):1837–1844.

- , , , , . STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person's Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46(2):72–83.

- American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616–631.

- , , , . Preventing potentially inappropriate medication use in hospitalized older patients with a computerized provider order entry warning system. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1331–1336.

- . Hazards of Hospitalization of the Elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219–223.

- . Improving health care for older persons. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(5 part 2):421–424.

- , , , , , . Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: evidence for the Institute of Medicine's "retooling for an aging America" report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(12):2328–2337.

- , , , et al. Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2171–2179.

- , , , . Changes in functional status and the risks of subsequent nursing home placement and death. J Gerontol. 1993;48(3):S94–S101.

- , , . Risk factors for nursing home placement in a population‐based dementia cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5):519–525.

- , , , . The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660–1665.

- , , , , . A systematic review of predictors and screening instruments to identify older hospitalized patients at risk for functional decline. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(1):46–57.

- . Immobility and falls. Clin Geriatr Med. 1998;14(4):699–726.

- , , . Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1263–1270.

- , , . Impact of a nurse‐driven mobility protocol on functional decline in hospitalized older adults. J Nurs Care Qual. 2009;24(4):325–331.

- , . Impact of early mobilization protocol on the medical‐surgical inpatient population: an integrated review of literature. Clin Nurse Spec. 2012;26(2):87–94.

- , , , . The aging population and its impact on the surgery workforce. Ann Surg. 2003;238(2):170–177.

- . Perioperative care of the elderly patient: an update. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(suppl 4):S16–S21.

- , , . Frailty in the older surgical patient: a review. Age Ageing. 2012;41(2):142–147.

- . The assessment and management of peri‐operative pain in older adults. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(suppl 1):54–60.

- , . National Research Strategies: what outcomes are important in peri‐operative elderly care? Anaesthesia. 2014;69(suppl 1):61–69.

- , . 2002 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Adv Data. 2004;342:1–30.

- , . Hospitalization in the United States, 2002. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005.

- , , , et al. The Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient program: a collaborative faculty development program for hospitalists, general internists, and geriatricians. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):384–393.

- , . Advancement of geriatrics education. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(6):370.

- , , , , , . Advancing geriatrics education: an efficient faculty development program for academic hospitalists increases geriatric teaching. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):541–546.

Older adults with high levels of medical complexity occupy an increasing fraction of beds in acute‐care hospitals in the United States.[1, 2] By 2007, patients age 65 years and older accounted for nearly half of adult inpatient days of care.[1] These patients are commonly cared for by hospitalists who number more than 40,000.[3] Although hospitalists are most often trained in internal medicine, they have typically received limited formal geriatrics training. Increasingly, access to experts in geriatric medicine is limited.[4] Further, hospitalists and others who practice in acute care are limited by the lack of research to address the needs of the older adult population, specifically in the diagnosis and management of conditions encountered during acute illness.

To better support hospitalists in providing acute inpatient geriatric care, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) partnered with the Association of Specialty Professors to develop a research agenda to bridge this gap. Using methodology from the James Lind Alliance (JLA) and the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), the SHM joined with older adult advocacy groups, professional societies of providers, and funders to create a geriatric‐focused acute‐care research agenda, highlighting 10 key research questions.[5, 6, 7] The goal of this approach was to produce and promote high integrity, evidence‐based information that comes from research guided by patients, caregivers, and the broader healthcare community.[8] In this article, we describe the methodology and results of this agenda‐setting process, referred to as the Acute Care of Older Patients (ACOP) Priority Setting Partnership.

METHODS

Overview

This project focused on topic generation, the first step in the PCORI framework for identification and prioritization of research areas.[5] We employed a specific and defined methodology to elicit and prioritize potential research topics incorporating input from representatives of older patients, family caregivers, and healthcare providers.[6]

To elicit this input, we chose a collaborative and consultative approach to stakeholder engagement, drawing heavily from the published work of the JLA, an initiative promoting patient‐clinician partnerships in health research developed in the United Kingdom.[6] We previously described the approach elsewhere.[7]

The ACOP process for determining the research agenda consisted of 4 steps: (1) convene, (2) consult, (3) collate, and (4) prioritize.[6] Through these steps, detailed below, we were able to obtain input from a broad group of stakeholders and engage the stakeholders in a process of reducing and refining our research questions.

Convene

The steering committee (the article's authors) convened a stakeholder partnership group that included stakeholders representing patients and caregivers, advocacy organizations for the elderly, organizations that address diseases and conditions common among hospitalized older patients, provider professional societies (eg, hospitalists, subspecialists, and nurses and social workers), payers, and funders. Patient, caregiver, and advocacy organizations were identified based on their engagement in aging and health policy advocacy by SHM staff and 1 author who had completed a Health and Aging Policy Fellowship (H.L.W.).

The steering committee issued e‐mail invitations to stakeholder organizations, making initial inquiries through professional staff and relevant committee chairs. Second inquiries were made via e‐mail to each organization's volunteer leadership. We developed a webinar that outlined the overall research agenda setting process and distributed the webinar to all stakeholders. The stakeholder organizations were asked to commit to (1) surveying their memberships and (2) participating actively in prioritization by e‐mail and at a 1‐day meeting in Washington DC.

Consult

Each stakeholder organization conducted a survey of its membership via an Internet‐based survey in the summer of 2013 (see Supporting Information, Appendix A, in the online version of this article). Stakeholder organizations were asked to provide up to 75 survey responses each. Though a standard survey was used, the steering committee was not prescriptive in the methodology of survey distribution to accommodate the structure and communication methods of the individual stakeholder organizations. Survey respondents were asked to identify up to 5 unanswered questions relevant to the acute care of older persons and also provide demographic information.

Collate

In the collating process, we clarified and categorized the unanswered questions submitted in the individual surveys. Each question was initially reviewed by a member of the steering committee, using explicit criteria (see Supporting Information, Appendix B, in the online version of this article). Questions that did not meet all 4 criteria were removed. For questions that met all criteria, we clarified language, combined similar questions, and categorized each question. Categories were created in a grounded process, in which individual reviewers assigned categories based on the content of the questions. Each question could be assigned to up to 2 categories. Each question was then reviewed by a second member of the steering committee using the same 4 criteria. As part of this review, similar questions were consolidated, and when possible, questions were rewritten in a standard format.[6]

Finally, the steering committee reviewed previously published research agendas looking for additional relevant unanswered questions, specifically the New Frontiers Research Agenda created by the American Geriatrics Society in conjunction with participating subspecialty societies,[9] the Cochrane Library, and other systematic reviews identified in the literature via PubMed search.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

Prioritize

The resulting list of unanswered questions was prioritized in 2 phases. First, the list was e‐mailed to all stakeholder organizations. The organizations were asked to vote on their top 10 priorities from this list using an online ballot, assigning 10 points to their highest priority down to 1 point for their lowest priority. In so doing, they were asked to consider explicit criteria (see Supporting Information, Appendix B, in the online version of this article). Each organization had only 1 ballot and could arrive at their top 10 list in any manner they wished. The balloting from this phase was used to develop a list of unanswered questions for the second round of in‐person prioritization. Each priority's scores were totaled across all voting organizations. The 29 priorities with the highest point totals were brought to the final prioritization round because of a natural cut point at priority number 29, rather than number 30.

For the final prioritization round, the steering committee facilitated an in‐person meeting in Washington, DC in October 2013 using nominal group technique (NGT) methodologies to arrive at consensus.[16] During this process stakeholders were asked to consider additional criteria (see Supporting Information, Appendix B, in the online version of this article).

RESULTS

Table 1 lists the organizations who engaged in 1 or more parts of the topic generation process. Eighteen stakeholder organizations agreed to participate in the convening process. Ten organizations did not respond to our solicitation and 1 declined to participate.

| Organization (N=18) | Consultation % of Survey Responses (N=580) | Prioritization Round 1 | Prioritization Round 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Association | 7.0% | Yes | Yes |

| American Academy of Neurology | 3.4% | Yes | Yes |

| American Association of Retired Persons | 0.8% | No | No |

| American College of Cardiology | 11.4% | Yes | Yes |

| American College of Emergency Physicians | 1.3% | No | No |

| American College of Surgeons | 1.0% | Yes | Yes |

| American Geriatrics Society | 7.6% | Yes | Yes |

| American Hospital Association | 1.7% | Yes | No |

| Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services | 0.8% | Yes | Yes |

| Gerontological Society of America | 18.9% | Yes | Yes |

| National Alliance for Caregiving | 1.0% | Yes | Yes |

| National Association of Social Workers | 5.9% | Yes | Yes |

| National Coalition for Healthcare | 0.6% | No | No |

| National Institute on Aging | 2.1% | Yes | Yes |

| National Partnership for Women and Families | 0.0% | Yes | Yes |

| Nursing Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders | 28.6% | Yes | No |

| Society of Critical Care Medicine | 12.0% | Yes | Yes |

| Society of Hospital Medicine | 4.6% | Yes | Yes |

Seventeen stakeholder organizations obtained survey responses from a total of 580 individuals (range, 3150 per organization), who were asked to identify important unanswered questions in the acute care of older persons. Survey respondents were typically female (77%), white (85%), aged 45 to 65 years (65%), and identified themselves as health professionals (90%). Twenty‐six percent of respondents also identified as patients or family caregivers. Their surveys included 1299 individual questions.

Figure 1 summarizes our collation and prioritization process and reports the numbers of questions resulting at each stage. Nine hundred nineteen questions were removed during the first review conducted by steering committee members, and 31 question categories were identified. An additional 305 questions were removed in the second review, with 75 questions remaining. As the final step of the collating process, literature review identified 39 relevant questions not already suggested or moved forward through our consultation and collation process. These questions were added to the list of unanswered questions.

In the first round of prioritization, this list of 114 questions was emailed to each stakeholder organization (Table 1). After the stakeholder voting process was completed, 29 unanswered questions remained (see Supporting Information, Appendix C, in the online version of this article). These questions were refined and prioritized in the in‐person meeting to create the final list of 10 questions. The stakeholders present in the meeting represented 13 organizations (Table 1). Using the NGT with several rounds of small group breakouts and large group deliberation, 9 of the top 10 questions were selected from the list of 29. One additional highly relevant question that had been removed earlier in the collation process regarding workforce was added back by the stakeholder group.

This prioritized research agenda appears in Table 2 and below, organized alphabetically by topic.

- Advanced care planning: What approaches for determining and communicating goals of care across and within healthcare settings are most effective in promoting goal‐concordant care for hospitalized older patients?

- Care transitions: What is the comparative effectiveness of transitional care models on patient‐centered outcomes for hospitalized older adults?

- Delirium: What practices are most effective for consistent recognition, prevention, and treatment of delirium subtypes among hospitalized older adults?

- Dementia: Does universal assessment of hospitalized older adults for cognitive impairment (eg, at presentation and/or discharge) lead to more appropriate application of geriatric care principles and improve patient‐centered outcomes?

- Depression: Does identifying depressive symptoms during a hospital stay and initiating a therapeutic plan prior to discharge improve patient‐centered and/or disease‐specific outcomes?

- Medications: What systems interventions improve medication management for older adults (ie, appropriateness of medication choices and dosing, compliance, cost) in the hospital and postacute care?

- Models of care: For which populations of hospitalized older adults does systematic implementation of geriatric care principles/processes improve patient‐centered outcomes?

- Physical function: What is the comparative effectiveness of interventions that promote in‐hospital mobility, improve and preserve physical function, and reduce falls among older hospitalized patients?

- Surgery: What perioperative strategies can be used to optimize care processes and improve outcomes in older surgical patients?

- Training: What is the most effective approach to training hospital‐based providers in geriatric and palliative care competencies?

| Topic | Scope of Problem | What Is known | Unanswered Question | Proposed Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Advanced‐care planning | Older persons who lack decision‐making capacity often do not have surrogates or clear goals of care documented.[19] Advanced‐care directives are associated with an increase in patient autonomy and empowerment, and although 15% to 25% of adults completed the documentation in 2004,[20] a recent study found completion rates have increased to 72%.[21] | Nursing home residents with advanced directives are less likely to be hospitalized.[22, 23] Advanced directive tools, such as POLST, work to translate patient preferences to medical order.[24] standardized patient transfer tools may help to improve transitions between nursing homes and hospitals.[25] However, advanced care planning fails to integrate into courses of care if providers are unwilling or unskilled in using advanced care documentation.[26] | What approaches for determining and communicating goals of care across and within healthcare settings are most effective in promoting goal‐concordant care for hospitalized older patients? | Potential interventions: |

| Decision aids | ||||

| Standard interdisciplinary advanced care planning approach | ||||

| Patient advocates | ||||

| Potential outcomes might include: | ||||

| Completion of advanced directives and healthcare power of attorney | ||||

| Patient‐centered outcomesa | ||||

| Care transitions | Hospital readmission from home and skilled nursing facilities occurs within 30 days in up to a quarter of patients.[27, 28] The discharge of complex older hospitalized patients is fraught with challenges. The quality of the hospital discharge process can influence outcomes for vulnerable older patients.[29, 30, 31, 32] Studies measuring the quality of hospital discharge frequently find deficits in documentation of assessment of geriatric syndromes,[33] poor patient/caregiver understanding,[34, 35] and poor communication and follow‐up with postacute providers.[35, 36, 37, 38] | As many as 10 separate domains may influence the success of a discharge.[39] There is limited evidence, regarding quality‐of‐care transitions for hospitalized older patients. The Coordinated‐Transitional Care Program found that follow‐up with telecommunication decreased readmission rates and improved transitional care for a high‐risk condition veteran population.[40] There is modest evidence for single interventions,[41] whereas the most effective hospital‐to‐community care interventions address multiple processes in nongeriatric populations.[39, 42, 43] | What is the comparative effectiveness of the transitional care models on patient‐centered outcomes for hospitalized older adults? | Possible models: |

| Established vs novel care‐transition models | ||||

| Disease‐specific vs general approaches | ||||

| Accountable care models | ||||

| Caregiver and family engagement | ||||

| Community engagement | ||||

| Populations of interest: | ||||

| Patients with dementia | ||||

| Patients with multimorbidity | ||||

| Patients with geriatric syndromes | ||||

| Patients with psychiatric disease | ||||

| Racially and ethnically diverse patients | ||||

| Outcomes: | ||||

| Readmission | ||||

| Other adverse events | ||||

| Cost and healthcare utilization | ||||

| Patient‐centered outcomesa | ||||

| Delirium | Among older inpatients, the prevalence of delirium varies with severity of illness. Among general medical patients, in‐hospital prevalence ranges from 10% to 25 %.[44, 45] In the ICU, prevalence estimates are higher, ranging from 25% to as high as 80%.[46, 47] Delirium independently predicts increased length of stay,[48, 49] long‐term cognitive impairment,[50, 51] functional decline,[51] institutionalization,[52] and short‐ and long‐term mortality.[52, 53, 54] | Multicomponent strategies have been shown to be effective in preventing delirium. A systematic review of 19 such interventions identified the most commonly included such as[55]: early mobilization, nutrition supplements, medication review, pain management, sleep enhancement, vision/hearing protocols, and specialized geriatric care. Studies have included general medical patients, postoperative patients, and patients in the ICU. The majority of these studies found reductions in either delirium incidence (including postoperative), delirium prevalence, or delirium duration. Although medications have not been effective in treating delirium in general medical patients,[48] the choice and dose of sedative agents has been shown to impact delirium in the ICU.[56, 57, 58] | What practices are most effective for consistent recognition, prevention, and treatment of delirium subtypes (hypoactive, hyperactive, and mixed) among hospitalized older adults? | Outcomes to examine: |

| Delirium incidence (including postoperative) | ||||

| Delirium duration | ||||

| Delirium‐/coma‐free days | ||||

| Delirium prevalence at discharge | ||||

| Subsyndromal delirium | ||||

| Potential prevention and treatment modalities: | ||||

| Family education or psychosocial interventions | ||||

| Pharmacologic interventions | ||||

| Environmental modifications | ||||

| Possible areas of focus: | ||||

| Special populations | ||||

| Patients with varying stages of dementia | ||||

| Patients with multimorbidity | ||||

| Patients with geriatric syndromes | ||||

| Observation patients | ||||

| Diverse settings | ||||

| Emergency department | ||||

| Perioperative | ||||

| Skilled nursing/rehab/long‐term acute‐care facilities | ||||

| Dementia | 13% to 63% of older persons in the hospital have dementia.[59] Dementia is often unrecognized among hospitalized patients.[60] The presence of dementia is associated with a more rapid functional decline during admission and delayed hospital discharge.[59] Patients with dementia require more nursing hours, and are more likely to have complications[61] or die in care homes rather than in their preferred site.[59] | Several tools have been validated to screen for dementia in the hospital setting.[62] Studies have assessed approaches to diagnosing delirium in hospitalized patients with dementia.[63] Cognitive and functional stimulation interventions may have a positive impact on reducing behavioral issues.[64, 65] | Does universal assessment of hospitalized older adults for cognitive impairment (eg, at presentation and/or discharge) lead to more appropriate application of geriatric care principles and improve patient centered outcomes? | Potential interventions: |

| Dementia or delirium care | ||||

| Patient/family communication and engagement strategies | ||||

| Maintenance/recovery of independent functional status | ||||

| Potential outcomes: | ||||

| Patient‐centered outcomesa | ||||

| Length of stay, cost, and healthcare utilization (including palliative care) | ||||

| Immediate invasive vs early conservative treatments pursued | ||||

| Depression | Depression is a common geriatric syndrome among acutely ill older patients, occurring in up to 45% of patients.[66, 67] Rates of depression are similar among patients discharged following a critical illness, with somatic, rather than cognitive‐affective complaints being the most prevalent.[68] Depression among inpatients or immediately following hospitalization independently predicts worse functional outcomes,[69] cognitive decline,[70] hospital readmission,[71, 72] and long‐term mortality.[69, 73] Finally, geriatric patients are known to respond differently to medical treatment.[74, 75] | Although highly prevalent, depression is poorly recognized and managed in the inpatient setting. Depression is recognized in only 50% of patients, with previously undiagnosed or untreated depression being at highest risk for being missed.[76] The role of treatment of depression in the inpatient setting is poorly understood, particularly for those with newly recognized depression or depressive symptoms. Some novel collaborative care and telephone outreach programs have led to increases in depression treatment in patients with specific medical and surgical conditions, resulting in early promising mental health and comorbid outcomes.[77, 78] The efficacy of such programs for older patients is unknown. | Does identifying depressive symptoms during a hospital stay and initiating a therapeutic plan prior to discharge improve patient‐centered and/or disease‐specific outcomes? | Possible areas of focus: |

| Comprehensive geriatric and psychosocial assessment; | ||||

| Inpatient vs outpatient initiation of pharmacological therapy | ||||

| Integration of confusion assessment method into therapeutic approaches | ||||

| Linkages with outpatient mental health resources | ||||

| Medications | Medication exposure, particularly potentially inappropriate medications, is common in hospitalized elders.[79] Medication errorsof dosage, type, and discrepancy between what a patient takes at home and what is known to his/her prescribing physicianare common and adversely affects patient safety.[80] Geriatric populations are disproportionately affected, especially those taking more than 5 prescription medications per day.[81] | Numerous strategies including electronic alerts, screening protocols, and potentially inappropriate medication lists (Beers list, STOPP) exist, though the optimal strategies to limit the use of potentially inappropriate medications is not yet known.[82, 83, 84] | What systems interventions improve medication management for older adults (ie, appropriateness of medication choices and dosing, compliance, cost) in hospital and post‐acute care? | Possible areas of focus: |

| Use of healthcare information technology | ||||

| Communication across sites of care | ||||

| Reducing medication‐related adverse events | ||||

| Engagement of family caregivers | ||||

| Patient‐centered strategies to simplify regimens | ||||

| Models of care | Hospitalization marks a time of high risk for older patients. Up to half die during hospitalization or within the year following the hospitalization. There is high risk of nosocomial events, and more than a third experience a decline in health resulting in longer hospitalizations and/or placement in extended‐care facilities.[73, 85, 86] | Comprehensive inpatient care for older adults (acute care for elders units, geriatric evaluation and management units, geriatric consultation services) were studied in 2 meta‐analyses, 5 RCTs, and 1 quasiexperimental study and summarized in a systematic review.[87] The studies reported improved quality of care (1 of 1 article), quality of life (3 of 4), functional autonomy (5 of 6), survival (3 of 6), and equal or lower healthcare utilization (7 of 8). | For which populations of hospitalized older adults does systematic implementation of geriatric care principles/processes improve patient‐centered outcomes? | Potential populations: |

| Patients of the emergency department, critical care, perioperative, and targeted medical/surgical units | ||||

| Examples of care principles: | ||||

| Geriatric assessment, early mobility, medication management, delirium prevention, advanced‐care planning, risk‐factor modification, caregiver engagement | ||||

| Potential outcomes: | ||||

| Patient‐centered outcomesa | ||||

| Cost | ||||

| Physical function | Half of older patients will lose functional capacity during hospitalization.[88] Loss of physical function, particularly of lower extremities, is a risk factor for nursing home placement.[89, 90] Older hospitalized patients spend the majority (up to 80%) of their time lying in bed, even when they are capable of walking independently.[91] | Loss of independences with ADL capabilities is associated with longer hospital stays, higher readmission rates, and higher mortality risk.[92] Excessive time in bed during a hospital stay is also associated with falls.[93] Often, hospital nursing protocols and physician orders increase in‐hospital immobility in patients.[91, 94] However, nursing‐driven mobility protocols can improve functional outcomes of older hospitalized patients.[95, 96] | What is the comparative effectiveness of interventions that promote in‐hospital mobility, improve and preserve physical function, and reduce falls among older hospitalized patients? | Potential interventions: |

| Intensive physical therapy | ||||

| Incidental functional training | ||||

| Restraint reduction | ||||

| Medication management | ||||

| Potential outcomes: | ||||

| Discharge location | ||||

| Delirium, pressure ulcers, and falls | ||||

| Surgery | An increasing number of persons over age 65 years are undergoing surgical procedures.[97] These persons are at increased risk for developing delirium/cogitative dysfunction,[98] loss of functional status,[99] and exacerbations of chronic illness.[97] Additionally, pain management may be harder to address in this population.[100] Current outcomes may not reflect the clinical needs of elder surgical patients.[101] | Tailored drug selection and nursing protocols may prevent delirium.[98] Postoperative cognitive dysfunction may require weeks for resolution. Identifying frail patients preoperatively may lead to more appropriate risk stratification and improved surgical outcomes.[99] Pain management strategies focused on mitigating cognitive impact and other effects may also be beneficial.[100] Development of risk‐adjustment tools specific to older populations, as well as measures of frailty and patient‐centered care, have been proposed.[101] | What perioperative strategies can be used to optimize care processes and improve outcomes in older surgical patients? | Potential strategies: |

| Preoperative risk assessment and optimization for frail or multimorbid older patients | ||||

| Perioperative management protocols for frail or multimorbid older patients | ||||

| Potential outcomes: | ||||

| Postoperative patient centered outcomesa | ||||

| Perioperative cost, healthcare utilization | ||||