User login

Acral Necrosis After PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy

To the Editor:

A 67-year-old woman presented to the hospital with painful hands and feet. Two weeks prior, the patient experienced a few days of intermittent purple discoloration of the fingers, followed by black discoloration of the fingers, toes, and nose with notable pain. She reported no illness preceding the presenting symptoms, and there was no progression of symptoms in the days preceding presentation.

The patient had a history of smoking. She had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as well as recurrent non–small cell lung cancer that was treated most recently with a 1-year course of the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab (last treatment was 4 months prior to the current presentation).

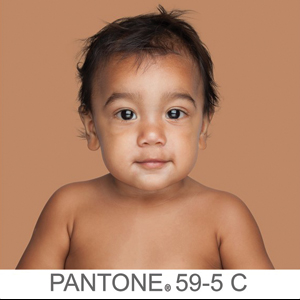

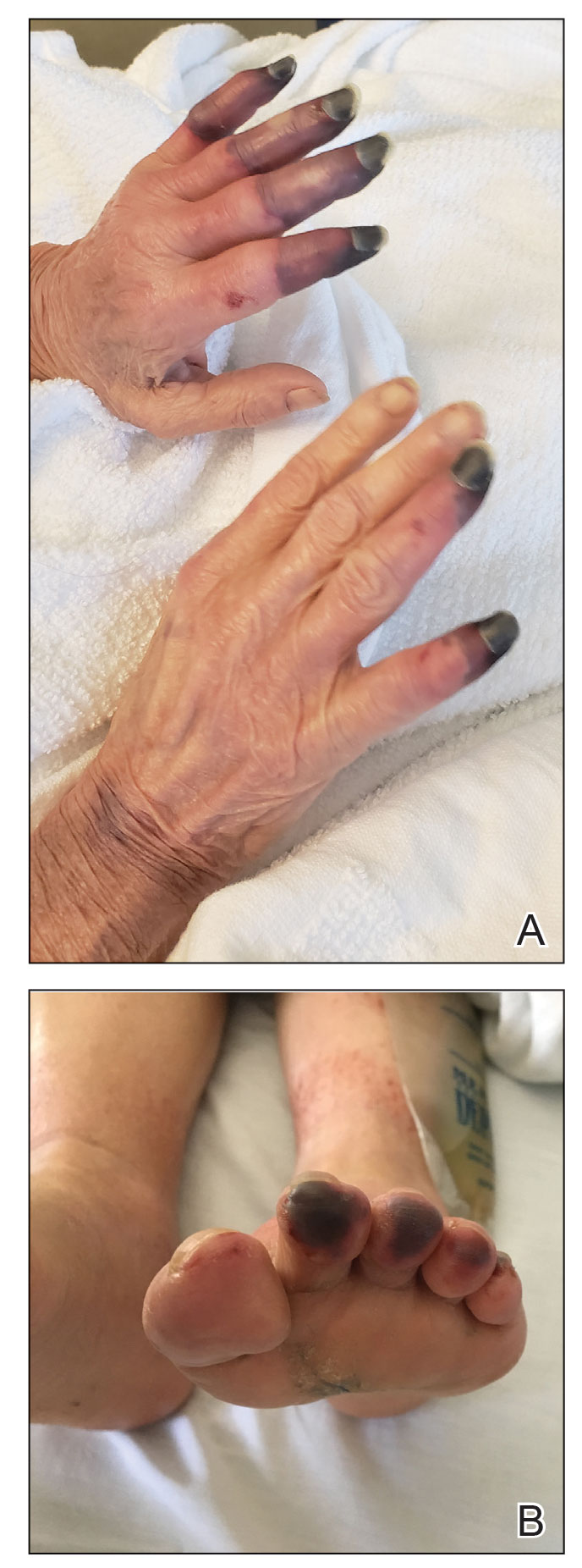

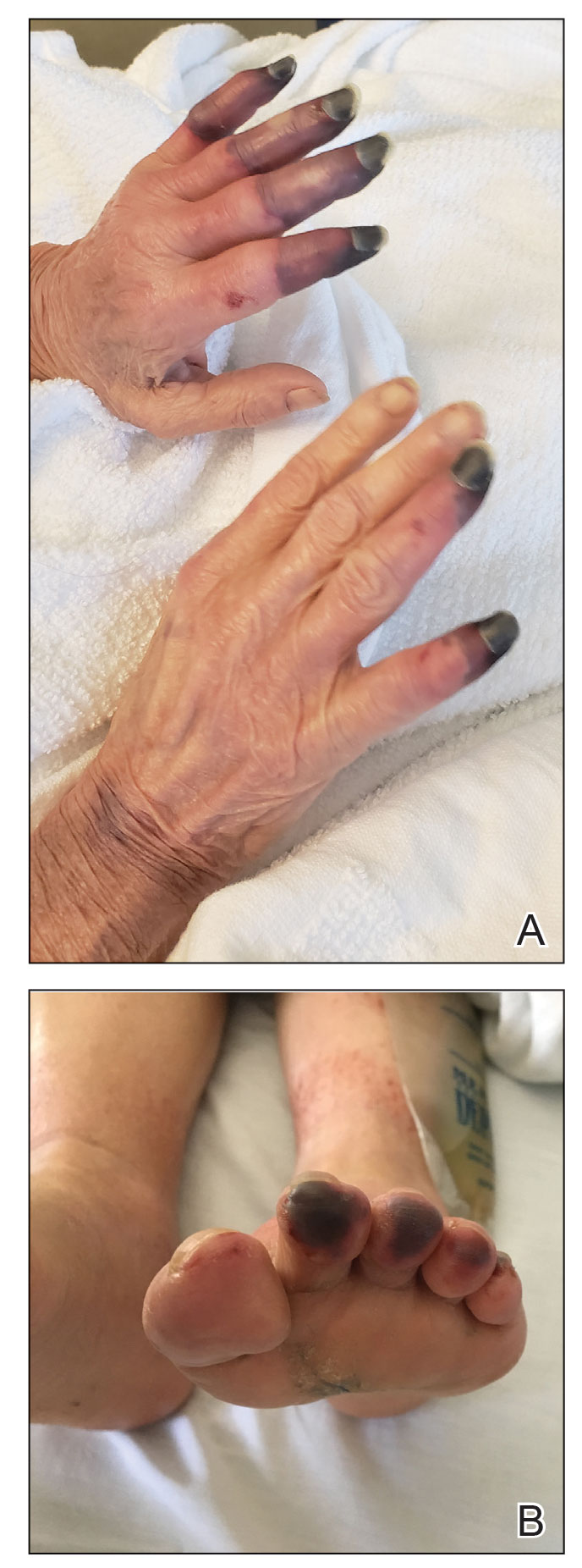

Physical examination revealed necrosis of the tips of the second, third, and fourth fingers of the left hand, as well as the tips of the third and fourth fingers of the right hand, progressing to purpura proximally on all involved fingers (Figure, A); scattered purpura and necrotic papules on the toe pads (Figure, B); and a 2- to 3-cm black plaque on the nasal tip. The patient was afebrile.

An embolic and vascular workup was performed. Transthoracic echocardiography was negative for thrombi, ankle brachial indices were within reference range, and computed tomography angiography revealed a few nonocclusive coronary plaques. Conventional angiography was not performed.

Laboratory testing revealed a mildly elevated level of cryofibrinogens (cryocrit, 2.5%); cold agglutinins (1:32); mild monoclonal κ IgG gammopathy (0.1 g/dL); and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, 76 mg/L [reference range, 0–10 mg/L]; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 38 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; fibrinogen, 571 mg/dL [reference range, 150–450 mg/dL]; and ferritin, 394 ng/mL [reference range, 10–180 ng/mL]). Additional laboratory studies were negative or within reference range, including tests of anti-RNA polymerase antibody, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticardiolipin antibody, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3), cryoglobulins, and complement; human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C virus serologic studies; prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and lupus anticoagulant; and a heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel.

A skin biopsy adjacent to an area of necrosis on the finger showed thickened walls of dermal vessels, sparse leukocytoclastic debris, and evidence of recanalizing medium-sized vessels. Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative.

Based on the clinical history and histologic findings showing an absence of vasculitis, a diagnosis of acral necrosis associated with the PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab—a delayed immune-related event (DIRE)—was favored. The calcium channel blocker amlodipine was started at a dosage of 2.5 mg/d orally. Necrosis of the toes resolved over the course of 1 week; however, necrosis of the fingers remained unchanged. After 1 week of hospitalization, the patient was discharged at her request.

Acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been reported as a rare and recalcitrant immune-related adverse event (AE).1-4 However, our patient’s symptoms occurred months after treatment was discontinued, which is consistent with a DIRE.5 The course of acral necrosis begins with acrocyanosis (a Raynaud disease–like phenomenon) of the fingers that progresses to necrosis. A history of Raynaud disease or other autoimmune disorder generally is absent.1 Our patient’s history indicated actively smoking at the time of presentation, similar to a case described by Khaddour et al.1 Similarly, in a case presented by Comont et al,3 the patient also had a history of smoking. In a recent study of acute vascular events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, 16 of 31 patients had a history of smoking.6

No definitive diagnostic laboratory or pathologic findings are associated with acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Histopathologic analysis does not demonstrate vasculitis or other overt vascular pathology.2,3

The optimal treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated digital necrosis is unclear. Corticosteroids and discontinuation of the immune checkpoint inhibitor generally are employed,1-4 though treatment response has been variable. Other therapies such as calcium channel blockers (as in our case), sympathectomy,1 epoprostenol, botulinum injection, rituximab,2 and alprostadil4 have been attempted without clear effect.

We considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in our patient, which was ruled out because the syndrome typically occurs in the setting of a worsening underlying malignancy7; our patient’s cancer was stable to improved. Thromboangiitis obliterans was ruled out by the absence of a characteristic thrombus on biopsy, the patient’s older age, and involvement of the nose.

We report an unusual case of acral necrosis occurring as a DIRE in response to administration of an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Further description is needed to clarify the diagnostic criteria for and treatment of this rare autoimmune phenomenon.

- Khaddour K, Singh V, Shayuk M. Acral vascular necrosis associated with immune-check point inhibitors: case report with literature review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:449. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5661-x

- Padda A, Schiopu E, Sovich J, et al. Ipilimumab induced digital vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:12. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0321-2

- Comont T, Sibaud V, Mourey L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related acral vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:120. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0443-6

- Gambichler T, Strutzmann S, Tannapfel A, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in a patient with metastatic melanoma under immune checkpoint blockade. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:327. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3313-6

- Couey MA, Bell RB, Patel AA, et al. Delayed immune-related events (DIRE) after discontinuation of immunotherapy: diagnostic hazard of autoimmunity at a distance. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:165. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0645-6

- Bar J, Markel G, Gottfried T, et al. Acute vascular events as a possibly related adverse event of immunotherapy: a single-institute retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;120:122-131. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.021

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:47-52. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120474

To the Editor:

A 67-year-old woman presented to the hospital with painful hands and feet. Two weeks prior, the patient experienced a few days of intermittent purple discoloration of the fingers, followed by black discoloration of the fingers, toes, and nose with notable pain. She reported no illness preceding the presenting symptoms, and there was no progression of symptoms in the days preceding presentation.

The patient had a history of smoking. She had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as well as recurrent non–small cell lung cancer that was treated most recently with a 1-year course of the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab (last treatment was 4 months prior to the current presentation).

Physical examination revealed necrosis of the tips of the second, third, and fourth fingers of the left hand, as well as the tips of the third and fourth fingers of the right hand, progressing to purpura proximally on all involved fingers (Figure, A); scattered purpura and necrotic papules on the toe pads (Figure, B); and a 2- to 3-cm black plaque on the nasal tip. The patient was afebrile.

An embolic and vascular workup was performed. Transthoracic echocardiography was negative for thrombi, ankle brachial indices were within reference range, and computed tomography angiography revealed a few nonocclusive coronary plaques. Conventional angiography was not performed.

Laboratory testing revealed a mildly elevated level of cryofibrinogens (cryocrit, 2.5%); cold agglutinins (1:32); mild monoclonal κ IgG gammopathy (0.1 g/dL); and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, 76 mg/L [reference range, 0–10 mg/L]; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 38 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; fibrinogen, 571 mg/dL [reference range, 150–450 mg/dL]; and ferritin, 394 ng/mL [reference range, 10–180 ng/mL]). Additional laboratory studies were negative or within reference range, including tests of anti-RNA polymerase antibody, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticardiolipin antibody, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3), cryoglobulins, and complement; human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C virus serologic studies; prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and lupus anticoagulant; and a heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel.

A skin biopsy adjacent to an area of necrosis on the finger showed thickened walls of dermal vessels, sparse leukocytoclastic debris, and evidence of recanalizing medium-sized vessels. Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative.

Based on the clinical history and histologic findings showing an absence of vasculitis, a diagnosis of acral necrosis associated with the PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab—a delayed immune-related event (DIRE)—was favored. The calcium channel blocker amlodipine was started at a dosage of 2.5 mg/d orally. Necrosis of the toes resolved over the course of 1 week; however, necrosis of the fingers remained unchanged. After 1 week of hospitalization, the patient was discharged at her request.

Acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been reported as a rare and recalcitrant immune-related adverse event (AE).1-4 However, our patient’s symptoms occurred months after treatment was discontinued, which is consistent with a DIRE.5 The course of acral necrosis begins with acrocyanosis (a Raynaud disease–like phenomenon) of the fingers that progresses to necrosis. A history of Raynaud disease or other autoimmune disorder generally is absent.1 Our patient’s history indicated actively smoking at the time of presentation, similar to a case described by Khaddour et al.1 Similarly, in a case presented by Comont et al,3 the patient also had a history of smoking. In a recent study of acute vascular events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, 16 of 31 patients had a history of smoking.6

No definitive diagnostic laboratory or pathologic findings are associated with acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Histopathologic analysis does not demonstrate vasculitis or other overt vascular pathology.2,3

The optimal treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated digital necrosis is unclear. Corticosteroids and discontinuation of the immune checkpoint inhibitor generally are employed,1-4 though treatment response has been variable. Other therapies such as calcium channel blockers (as in our case), sympathectomy,1 epoprostenol, botulinum injection, rituximab,2 and alprostadil4 have been attempted without clear effect.

We considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in our patient, which was ruled out because the syndrome typically occurs in the setting of a worsening underlying malignancy7; our patient’s cancer was stable to improved. Thromboangiitis obliterans was ruled out by the absence of a characteristic thrombus on biopsy, the patient’s older age, and involvement of the nose.

We report an unusual case of acral necrosis occurring as a DIRE in response to administration of an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Further description is needed to clarify the diagnostic criteria for and treatment of this rare autoimmune phenomenon.

To the Editor:

A 67-year-old woman presented to the hospital with painful hands and feet. Two weeks prior, the patient experienced a few days of intermittent purple discoloration of the fingers, followed by black discoloration of the fingers, toes, and nose with notable pain. She reported no illness preceding the presenting symptoms, and there was no progression of symptoms in the days preceding presentation.

The patient had a history of smoking. She had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as well as recurrent non–small cell lung cancer that was treated most recently with a 1-year course of the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab (last treatment was 4 months prior to the current presentation).

Physical examination revealed necrosis of the tips of the second, third, and fourth fingers of the left hand, as well as the tips of the third and fourth fingers of the right hand, progressing to purpura proximally on all involved fingers (Figure, A); scattered purpura and necrotic papules on the toe pads (Figure, B); and a 2- to 3-cm black plaque on the nasal tip. The patient was afebrile.

An embolic and vascular workup was performed. Transthoracic echocardiography was negative for thrombi, ankle brachial indices were within reference range, and computed tomography angiography revealed a few nonocclusive coronary plaques. Conventional angiography was not performed.

Laboratory testing revealed a mildly elevated level of cryofibrinogens (cryocrit, 2.5%); cold agglutinins (1:32); mild monoclonal κ IgG gammopathy (0.1 g/dL); and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, 76 mg/L [reference range, 0–10 mg/L]; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 38 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; fibrinogen, 571 mg/dL [reference range, 150–450 mg/dL]; and ferritin, 394 ng/mL [reference range, 10–180 ng/mL]). Additional laboratory studies were negative or within reference range, including tests of anti-RNA polymerase antibody, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticardiolipin antibody, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3), cryoglobulins, and complement; human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C virus serologic studies; prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and lupus anticoagulant; and a heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel.

A skin biopsy adjacent to an area of necrosis on the finger showed thickened walls of dermal vessels, sparse leukocytoclastic debris, and evidence of recanalizing medium-sized vessels. Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative.

Based on the clinical history and histologic findings showing an absence of vasculitis, a diagnosis of acral necrosis associated with the PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab—a delayed immune-related event (DIRE)—was favored. The calcium channel blocker amlodipine was started at a dosage of 2.5 mg/d orally. Necrosis of the toes resolved over the course of 1 week; however, necrosis of the fingers remained unchanged. After 1 week of hospitalization, the patient was discharged at her request.

Acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been reported as a rare and recalcitrant immune-related adverse event (AE).1-4 However, our patient’s symptoms occurred months after treatment was discontinued, which is consistent with a DIRE.5 The course of acral necrosis begins with acrocyanosis (a Raynaud disease–like phenomenon) of the fingers that progresses to necrosis. A history of Raynaud disease or other autoimmune disorder generally is absent.1 Our patient’s history indicated actively smoking at the time of presentation, similar to a case described by Khaddour et al.1 Similarly, in a case presented by Comont et al,3 the patient also had a history of smoking. In a recent study of acute vascular events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, 16 of 31 patients had a history of smoking.6

No definitive diagnostic laboratory or pathologic findings are associated with acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Histopathologic analysis does not demonstrate vasculitis or other overt vascular pathology.2,3

The optimal treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated digital necrosis is unclear. Corticosteroids and discontinuation of the immune checkpoint inhibitor generally are employed,1-4 though treatment response has been variable. Other therapies such as calcium channel blockers (as in our case), sympathectomy,1 epoprostenol, botulinum injection, rituximab,2 and alprostadil4 have been attempted without clear effect.

We considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in our patient, which was ruled out because the syndrome typically occurs in the setting of a worsening underlying malignancy7; our patient’s cancer was stable to improved. Thromboangiitis obliterans was ruled out by the absence of a characteristic thrombus on biopsy, the patient’s older age, and involvement of the nose.

We report an unusual case of acral necrosis occurring as a DIRE in response to administration of an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Further description is needed to clarify the diagnostic criteria for and treatment of this rare autoimmune phenomenon.

- Khaddour K, Singh V, Shayuk M. Acral vascular necrosis associated with immune-check point inhibitors: case report with literature review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:449. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5661-x

- Padda A, Schiopu E, Sovich J, et al. Ipilimumab induced digital vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:12. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0321-2

- Comont T, Sibaud V, Mourey L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related acral vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:120. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0443-6

- Gambichler T, Strutzmann S, Tannapfel A, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in a patient with metastatic melanoma under immune checkpoint blockade. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:327. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3313-6

- Couey MA, Bell RB, Patel AA, et al. Delayed immune-related events (DIRE) after discontinuation of immunotherapy: diagnostic hazard of autoimmunity at a distance. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:165. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0645-6

- Bar J, Markel G, Gottfried T, et al. Acute vascular events as a possibly related adverse event of immunotherapy: a single-institute retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;120:122-131. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.021

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:47-52. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120474

- Khaddour K, Singh V, Shayuk M. Acral vascular necrosis associated with immune-check point inhibitors: case report with literature review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:449. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5661-x

- Padda A, Schiopu E, Sovich J, et al. Ipilimumab induced digital vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:12. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0321-2

- Comont T, Sibaud V, Mourey L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related acral vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:120. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0443-6

- Gambichler T, Strutzmann S, Tannapfel A, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in a patient with metastatic melanoma under immune checkpoint blockade. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:327. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3313-6

- Couey MA, Bell RB, Patel AA, et al. Delayed immune-related events (DIRE) after discontinuation of immunotherapy: diagnostic hazard of autoimmunity at a distance. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:165. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0645-6

- Bar J, Markel G, Gottfried T, et al. Acute vascular events as a possibly related adverse event of immunotherapy: a single-institute retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;120:122-131. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.021

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:47-52. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120474

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware of acral necrosis as a rare adverse event of treatment with an immune checkpoint inhibitor.

- Delayed immune-related events are sequelae of immune checkpoint inhibitors that can occur months after treatment is discontinued.

Inequity, Bias, Racism, and Physician Burnout: Staying Connected to Purpose and Identity as an Antidote

“Where are you really from?”

When I tell patients I am from Casper, Wyoming—wh ere I have lived the majority of my life—it’smet with disbelief. The subtext: YOU can’t be from THERE.

I didn’t used to think much of comments like this, but as I have continued to hear them, I find myself feeling tired—tired of explaining myself, tired of being treated differently than my colleagues, and tired of justifying myself. My experiences as a woman of color sadly are not uncommon in medicine.

Sara Martinez-Garcia, BA

Racial bias and racism are steeped in the culture of medicine—from the medical school admissions process1,2 to the medical training itself.3 More than half of medical students who identify as underrepresented in medicine (UIM) experience microaggressions.4 Experiencing racism and sexism in the learning environment can lead to burnout, and microaggressions promote feelings of self-doubt and isolation. Medical students who experience microaggressions are more likely to report feelings of burnout and impaired learning.4 These experiences can leave one feeling as if “You do not belong” and “You are unworthy of being in this position.”

Addressing physician burnout already is complex, and addressing burnout caused by inequity, bias, and racism is even more so. In an ideal world, we would eliminate inequity, bias, and racism in medicine through institutional and individual actions. There has been movement to do so. For example, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which oversees standards for US resident and fellow training, launched ACGME Equity Matters (https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/ACGME-Equity-Matters/), an initiative aimed to improve diversity, equity, and antiracism practices within graduate medical eduation. However, we know that education alone isn’t enough to fix this monumental problem. Traditional diversity training as we have known it has never been demonstrated to contribute to lasting changes in behavior; it takes much more extensive and complex interventions to meaningfully reduce bias.5 In the meantime, we need action. As a medical community, we need to be better about not turning the other way when we see these things happening in our classrooms and in our hospitals. As individuals, we must self-reflect on the role that we each play in contributing to or combatting injustices and seek out bystander training to empower us to speak out against acts of bias such as sexism or racism. Whether it is supporting a fellow colleague or speaking out against an inappropriate interaction, we can all do our part. A very brief list of actions and resources to support our UIM students and colleagues are listed in the Table; those interested in more in-depth resources are encouraged to explore the Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit (https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/affinity-groups/cfas/diversity-inclusion-toolkit/resources).

We can’t change the culture of medicine quickly or even in our lifetime. In the meantime, those who are UIM will continue to experience these events that erode our well-being. They will continue to need support. Discussing mental health has long been stigmatized, and physicians are no exception. Many physicians are hesitant to discuss mental health issues out of fear of judgement and perceived or even real repercussions on their careers.10 However, times are changing and evolving with the current generation of medical students. It’s no secret that medicine is stressful. Most medical schools provide free counseling services, which lowers the barrier for discussions of mental health from the beginning. Making talk about mental health just as normal as talking about other aspects of health takes away the fear that “something is wrong with me” if someone seeks out counseling and mental health services. Faculty should actively check in and maintain open lines of communication, which can be invaluable for UIM students and their training experience. Creating an environment where trainees can be real and honest about the struggles they face in and out of the classroom can make everyone feel like they are not alone.

Addressing burnout in medicine is going to require an all-hands-on-deck approach. At an institutional level, there is a lot of room for improvement—improving systems for physicians so they are able to operate at their highest level (eg, addressing the burdens of prior authorizations and the electronic medical record), setting reasonable expectations around productivity, and creating work structures that respect work-life balance.11 But what can we do for ourselves? We believe that one of the most important ways to protect ourselves from burnout is to remember why. As a medical student, there is enormous pressure—pressure to learn an enormous volume of information, pass examinations, get involved in extracurricular activities, make connections, and seek research opportunities, while also cooking healthy food, grocery shopping, maintaining relationships with loved ones, and generally taking care of oneself. At times it can feel as if our lives outside of medical school are not important enough or valuable enough to make time for, but the pieces of our identity outside of medicine are what shape us into who we are today and are the roots of our purpose in medicine. Sometimes you can feel the most motivated, valued, and supported when you make time to have dinner with friends, call a family member, or simply spend time alone in the outdoors. Who you are and how you got to this point in your life are your identity. Reminding yourself of that can help when experiencing microaggressions or when that voice tries to tell you that you are not worthy. As you progress further in your career, maintaining that relationship with who you are outside of medicine can be your armor against burnout.

- Capers Q IV, Clinchot D, McDougle L, et al. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365-369.

- Lucey CR, Saguil A. The consequences of structural racism on MCAT scores and medical school admissions: the past is prologue. Acad Med. 2020;95:351-356.

- Nguemeni Tiako MJ, South EC, Ray V. Medical schools as racialized organizations: a primer. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1143-1144.

- Chisholm LP, Jackson KR, Davidson HA, et al. Evaluation of racial microaggressions experienced during medical school training and the effect on medical student education and burnout: a validation study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:310-314.

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why doesn’t diversity training work? the challenge for industry and academia. Anthropology Now. 2018;10:48-55.

- Okoye GA. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:57-60.

- Hackworth JM, Kotagal M, Bignall ONR, et al. Microaggressions: privileged observers’ duty to act and what they can do [published online December 1, 2021]. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052758.

- Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, et al. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2019;41:1112-1117.

- Scott K. Just Work: How to Root Out Bias, Prejudice, and Bullying to Build a Kick-Ass Culture of Inclusivity. St. Martin’s Press; 2021.

- Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289:3161-3166.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

“Where are you really from?”

When I tell patients I am from Casper, Wyoming—wh ere I have lived the majority of my life—it’smet with disbelief. The subtext: YOU can’t be from THERE.

I didn’t used to think much of comments like this, but as I have continued to hear them, I find myself feeling tired—tired of explaining myself, tired of being treated differently than my colleagues, and tired of justifying myself. My experiences as a woman of color sadly are not uncommon in medicine.

Sara Martinez-Garcia, BA

Racial bias and racism are steeped in the culture of medicine—from the medical school admissions process1,2 to the medical training itself.3 More than half of medical students who identify as underrepresented in medicine (UIM) experience microaggressions.4 Experiencing racism and sexism in the learning environment can lead to burnout, and microaggressions promote feelings of self-doubt and isolation. Medical students who experience microaggressions are more likely to report feelings of burnout and impaired learning.4 These experiences can leave one feeling as if “You do not belong” and “You are unworthy of being in this position.”

Addressing physician burnout already is complex, and addressing burnout caused by inequity, bias, and racism is even more so. In an ideal world, we would eliminate inequity, bias, and racism in medicine through institutional and individual actions. There has been movement to do so. For example, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which oversees standards for US resident and fellow training, launched ACGME Equity Matters (https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/ACGME-Equity-Matters/), an initiative aimed to improve diversity, equity, and antiracism practices within graduate medical eduation. However, we know that education alone isn’t enough to fix this monumental problem. Traditional diversity training as we have known it has never been demonstrated to contribute to lasting changes in behavior; it takes much more extensive and complex interventions to meaningfully reduce bias.5 In the meantime, we need action. As a medical community, we need to be better about not turning the other way when we see these things happening in our classrooms and in our hospitals. As individuals, we must self-reflect on the role that we each play in contributing to or combatting injustices and seek out bystander training to empower us to speak out against acts of bias such as sexism or racism. Whether it is supporting a fellow colleague or speaking out against an inappropriate interaction, we can all do our part. A very brief list of actions and resources to support our UIM students and colleagues are listed in the Table; those interested in more in-depth resources are encouraged to explore the Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit (https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/affinity-groups/cfas/diversity-inclusion-toolkit/resources).

We can’t change the culture of medicine quickly or even in our lifetime. In the meantime, those who are UIM will continue to experience these events that erode our well-being. They will continue to need support. Discussing mental health has long been stigmatized, and physicians are no exception. Many physicians are hesitant to discuss mental health issues out of fear of judgement and perceived or even real repercussions on their careers.10 However, times are changing and evolving with the current generation of medical students. It’s no secret that medicine is stressful. Most medical schools provide free counseling services, which lowers the barrier for discussions of mental health from the beginning. Making talk about mental health just as normal as talking about other aspects of health takes away the fear that “something is wrong with me” if someone seeks out counseling and mental health services. Faculty should actively check in and maintain open lines of communication, which can be invaluable for UIM students and their training experience. Creating an environment where trainees can be real and honest about the struggles they face in and out of the classroom can make everyone feel like they are not alone.

Addressing burnout in medicine is going to require an all-hands-on-deck approach. At an institutional level, there is a lot of room for improvement—improving systems for physicians so they are able to operate at their highest level (eg, addressing the burdens of prior authorizations and the electronic medical record), setting reasonable expectations around productivity, and creating work structures that respect work-life balance.11 But what can we do for ourselves? We believe that one of the most important ways to protect ourselves from burnout is to remember why. As a medical student, there is enormous pressure—pressure to learn an enormous volume of information, pass examinations, get involved in extracurricular activities, make connections, and seek research opportunities, while also cooking healthy food, grocery shopping, maintaining relationships with loved ones, and generally taking care of oneself. At times it can feel as if our lives outside of medical school are not important enough or valuable enough to make time for, but the pieces of our identity outside of medicine are what shape us into who we are today and are the roots of our purpose in medicine. Sometimes you can feel the most motivated, valued, and supported when you make time to have dinner with friends, call a family member, or simply spend time alone in the outdoors. Who you are and how you got to this point in your life are your identity. Reminding yourself of that can help when experiencing microaggressions or when that voice tries to tell you that you are not worthy. As you progress further in your career, maintaining that relationship with who you are outside of medicine can be your armor against burnout.

“Where are you really from?”

When I tell patients I am from Casper, Wyoming—wh ere I have lived the majority of my life—it’smet with disbelief. The subtext: YOU can’t be from THERE.

I didn’t used to think much of comments like this, but as I have continued to hear them, I find myself feeling tired—tired of explaining myself, tired of being treated differently than my colleagues, and tired of justifying myself. My experiences as a woman of color sadly are not uncommon in medicine.

Sara Martinez-Garcia, BA

Racial bias and racism are steeped in the culture of medicine—from the medical school admissions process1,2 to the medical training itself.3 More than half of medical students who identify as underrepresented in medicine (UIM) experience microaggressions.4 Experiencing racism and sexism in the learning environment can lead to burnout, and microaggressions promote feelings of self-doubt and isolation. Medical students who experience microaggressions are more likely to report feelings of burnout and impaired learning.4 These experiences can leave one feeling as if “You do not belong” and “You are unworthy of being in this position.”

Addressing physician burnout already is complex, and addressing burnout caused by inequity, bias, and racism is even more so. In an ideal world, we would eliminate inequity, bias, and racism in medicine through institutional and individual actions. There has been movement to do so. For example, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which oversees standards for US resident and fellow training, launched ACGME Equity Matters (https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/ACGME-Equity-Matters/), an initiative aimed to improve diversity, equity, and antiracism practices within graduate medical eduation. However, we know that education alone isn’t enough to fix this monumental problem. Traditional diversity training as we have known it has never been demonstrated to contribute to lasting changes in behavior; it takes much more extensive and complex interventions to meaningfully reduce bias.5 In the meantime, we need action. As a medical community, we need to be better about not turning the other way when we see these things happening in our classrooms and in our hospitals. As individuals, we must self-reflect on the role that we each play in contributing to or combatting injustices and seek out bystander training to empower us to speak out against acts of bias such as sexism or racism. Whether it is supporting a fellow colleague or speaking out against an inappropriate interaction, we can all do our part. A very brief list of actions and resources to support our UIM students and colleagues are listed in the Table; those interested in more in-depth resources are encouraged to explore the Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit (https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/affinity-groups/cfas/diversity-inclusion-toolkit/resources).

We can’t change the culture of medicine quickly or even in our lifetime. In the meantime, those who are UIM will continue to experience these events that erode our well-being. They will continue to need support. Discussing mental health has long been stigmatized, and physicians are no exception. Many physicians are hesitant to discuss mental health issues out of fear of judgement and perceived or even real repercussions on their careers.10 However, times are changing and evolving with the current generation of medical students. It’s no secret that medicine is stressful. Most medical schools provide free counseling services, which lowers the barrier for discussions of mental health from the beginning. Making talk about mental health just as normal as talking about other aspects of health takes away the fear that “something is wrong with me” if someone seeks out counseling and mental health services. Faculty should actively check in and maintain open lines of communication, which can be invaluable for UIM students and their training experience. Creating an environment where trainees can be real and honest about the struggles they face in and out of the classroom can make everyone feel like they are not alone.

Addressing burnout in medicine is going to require an all-hands-on-deck approach. At an institutional level, there is a lot of room for improvement—improving systems for physicians so they are able to operate at their highest level (eg, addressing the burdens of prior authorizations and the electronic medical record), setting reasonable expectations around productivity, and creating work structures that respect work-life balance.11 But what can we do for ourselves? We believe that one of the most important ways to protect ourselves from burnout is to remember why. As a medical student, there is enormous pressure—pressure to learn an enormous volume of information, pass examinations, get involved in extracurricular activities, make connections, and seek research opportunities, while also cooking healthy food, grocery shopping, maintaining relationships with loved ones, and generally taking care of oneself. At times it can feel as if our lives outside of medical school are not important enough or valuable enough to make time for, but the pieces of our identity outside of medicine are what shape us into who we are today and are the roots of our purpose in medicine. Sometimes you can feel the most motivated, valued, and supported when you make time to have dinner with friends, call a family member, or simply spend time alone in the outdoors. Who you are and how you got to this point in your life are your identity. Reminding yourself of that can help when experiencing microaggressions or when that voice tries to tell you that you are not worthy. As you progress further in your career, maintaining that relationship with who you are outside of medicine can be your armor against burnout.

- Capers Q IV, Clinchot D, McDougle L, et al. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365-369.

- Lucey CR, Saguil A. The consequences of structural racism on MCAT scores and medical school admissions: the past is prologue. Acad Med. 2020;95:351-356.

- Nguemeni Tiako MJ, South EC, Ray V. Medical schools as racialized organizations: a primer. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1143-1144.

- Chisholm LP, Jackson KR, Davidson HA, et al. Evaluation of racial microaggressions experienced during medical school training and the effect on medical student education and burnout: a validation study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:310-314.

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why doesn’t diversity training work? the challenge for industry and academia. Anthropology Now. 2018;10:48-55.

- Okoye GA. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:57-60.

- Hackworth JM, Kotagal M, Bignall ONR, et al. Microaggressions: privileged observers’ duty to act and what they can do [published online December 1, 2021]. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052758.

- Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, et al. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2019;41:1112-1117.

- Scott K. Just Work: How to Root Out Bias, Prejudice, and Bullying to Build a Kick-Ass Culture of Inclusivity. St. Martin’s Press; 2021.

- Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289:3161-3166.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

- Capers Q IV, Clinchot D, McDougle L, et al. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365-369.

- Lucey CR, Saguil A. The consequences of structural racism on MCAT scores and medical school admissions: the past is prologue. Acad Med. 2020;95:351-356.

- Nguemeni Tiako MJ, South EC, Ray V. Medical schools as racialized organizations: a primer. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1143-1144.

- Chisholm LP, Jackson KR, Davidson HA, et al. Evaluation of racial microaggressions experienced during medical school training and the effect on medical student education and burnout: a validation study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:310-314.

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why doesn’t diversity training work? the challenge for industry and academia. Anthropology Now. 2018;10:48-55.

- Okoye GA. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:57-60.

- Hackworth JM, Kotagal M, Bignall ONR, et al. Microaggressions: privileged observers’ duty to act and what they can do [published online December 1, 2021]. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052758.

- Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, et al. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2019;41:1112-1117.

- Scott K. Just Work: How to Root Out Bias, Prejudice, and Bullying to Build a Kick-Ass Culture of Inclusivity. St. Martin’s Press; 2021.

- Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289:3161-3166.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

Racial Limitations of Fitzpatrick Skin Type

Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) is the most commonly used classification system in dermatologic practice. It was developed by Thomas B. Fitzpatrick, MD, PhD, in 1975 to assess the propensity of the skin to burn during phototherapy.1 Fitzpatrick skin type also can be used to assess the clinical benefits and efficacy of cosmetic procedures, including laser hair removal, chemical peel and dermabrasion, tattoo removal, spray tanning, and laser resurfacing for acne scarring.2 The original FST classifications included skin types I through IV; skin types V and VI were later added to include individuals of Asian, Indian, and African origin.1 As a result, FST often is used by providers as a means of describing constitutive skin color and ethnicity.3

How did FST transition from describing the propensity of the skin to burn from UV light exposure to categorizing skin color, thereby becoming a proxy for race? It most likely occurred because there has not been another widely adopted classification system for describing skin color that can be applied to all skin types. Even when the FST classification scale is used as intended, there are inconsistencies with its accuracy; for example, self-reported FSTs have correlated poorly with sunburn risk as well as physician-reported FSTs.4,5 Although physician-reported FSTs have been demonstrated to correlate with race, race does not consistently correlate with objective measures of pigmentation or self-reported FSTs.5 For example, Japanese women often self-identify as FST type II, but Asian skin generally is considered to be nonwhite.1 Fitzpatrick himself acknowledged that race and ethnicity are cultural and political terms with no scientific basis.6 Fitzpatrick skin type also has been demonstrated to correlate poorly with constitutive skin color and minimal erythema dose values.7

We conducted an anonymous survey of dermatologists and dermatology trainees to evaluate how providers use FST in their clinical practice as well as how it is used to describe race and ethnicity.

Methods

The survey was distributed electronically to dermatologists and dermatology trainees from March 13 to March 28, 2019, using the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserv, as well as in person at the annual Skin of Color Society meeting in Washington, DC, on February 28, 2019. The 8-item survey included questions about physician demographics (ie, primary practice setting, board certification, and geographic location); whether the respondent identified as an individual with skin of color; and how the respondent utilized FST in clinical notes (ie, describing race/ethnicity, skin cancer risk, and constitutive [baseline] skin color; determining initial phototherapy dosage and suitability for laser treatments, and likelihood of skin burning). A t test was used to determine whether dermatologists who identified as having skin of color utilized FST differently.

Results

A total of 141 surveys were returned, and 140 respondents were included in the final analysis. Given the methods used to distribute the survey, a response rate could not be calculated. The respondents included more board-certified dermatologists (70%) than dermatology trainees (30%). Ninety-three percent of respondents indicated an academic institution as their primary practice location. Notably, 26% of respondents self-identified as having skin of color.

Forty-one percent of all respondents agreed that FST should be included in their clinical documentation. In response to the question “In what scenarios would you refer to FST in a clinical note?” 31% said they used FST to describe patients’ race or ethnicity, 47% used it to describe patients’ constitutive skin color, and 22% utilized it in both scenarios. Respondents who did not identify as having skin of color were more likely to use FST to describe constitutive skin color, though this finding was not statistically significant (P=.063). Anecdotally, providers also included FST in clinical notes on postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, and treatment with cryotherapy.

Comment

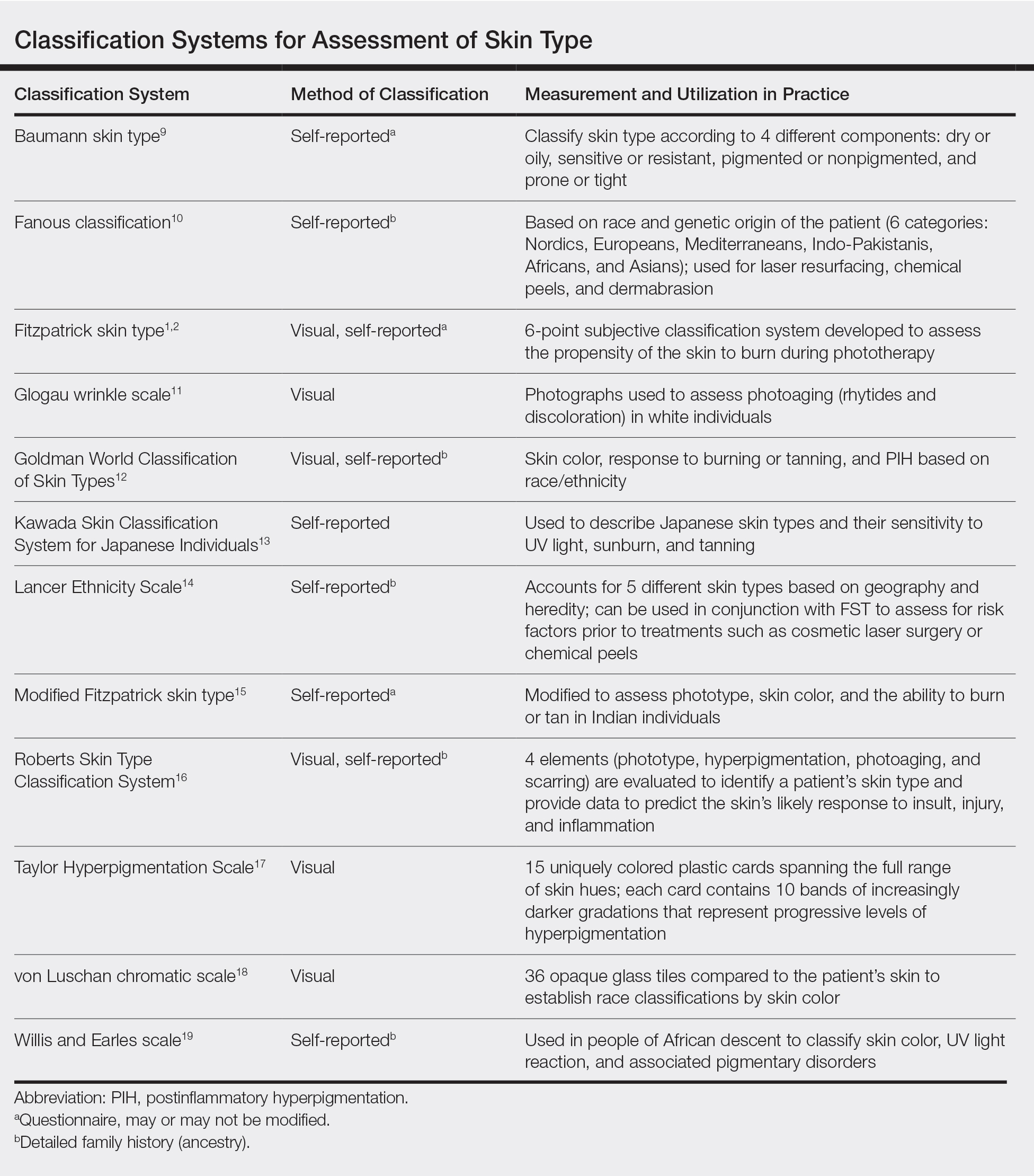

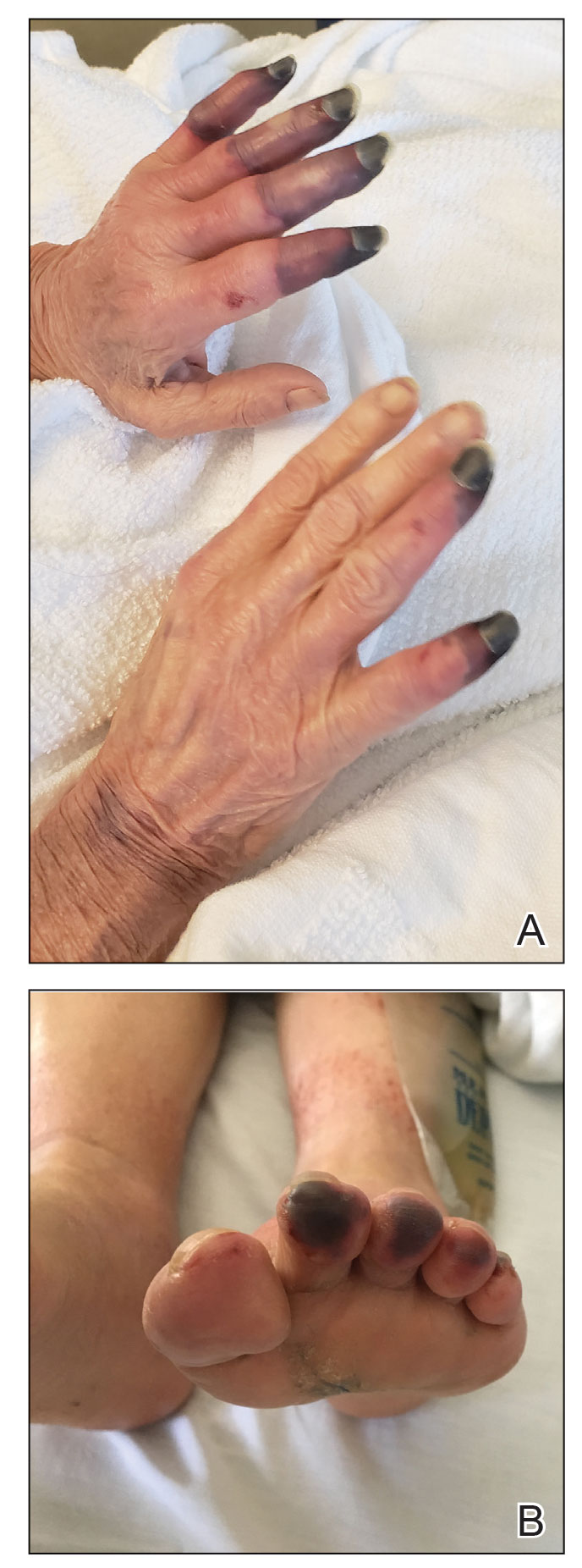

The US Census Bureau has estimated that half of the US population will be of non-European descent by 2050.8 As racial and ethnic distinctions continue to be blurred, attempts to include all nonwhite skin types under the umbrella term skin of color becomes increasingly problematic. The true number of skin colors is unknown but likely is infinite, as Brazilian artist Angélica Dass has demonstrated with her photographic project “Humanae” (Figure). Given this shift in demographics and the limitations of the FST, alternative methods of describing skin color must be developed.

© Angélica Dass | Humanae Work in Progress (Courtesy of the artist).

The results of our survey suggest that approximately one-third to half of academic dermatologists/dermatology trainees use FST to describe race/ethnicity and/or constitutive skin color. This misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color. Additionally, misuse of FST in academic settings may be problematic and confusing for medical students who may learn to use this common dermatologic tool outside of its original intent.

We acknowledge that the conundrum of how to classify individuals with nonwhite skin or skin of color is not simply answered. Several alternative skin classification models have been proposed to improve the sensitivity and specificity of identifying patients with skin of color (Table). Refining FST classification is one approach. Employing terms such as skin irritation, tenderness, itching, or skin becoming darker from sun exposure rather than painful burn or tanning may result in better identification.1,4 A study conducted in India modified the FST questionnaire to acknowledge cultural behaviors.15 Because lighter skin is culturally valued in this population, patient experience with purposeful sun exposure was limited; thus, the questionnaire was modified to remove questions on the use of tanning booths and/or creams as well as sun exposure and instead included more objective questions regarding dark brown eye color, black and dark brown hair color, and dark brown skin color.15 Other studies have suggested that patient-reported photosensitivity assessed via a questionnaire is a valid measure for assessing FST but is associated with an overestimation of skin color, known as “the dark shift.”20

Sharma et al15 utilized reflectance spectrophotometry as an objective measure of melanin and skin erythema. The melanin index consistently showed a positive correlation with FSTs as opposed to the erythema index, which correlated poorly.15 Although reflectance spectrometry accurately identifies skin color in patients with nonwhite skin,21,22 it is an impractical and cost-prohibitive tool for daily practice. A more practical tool for the clinical setting would be a visual color scale with skin hues spanning FST types I to VI, including bands of increasingly darker gradations that would be particularly useful in assessing skin of color. Once such tool is the Taylor Hyperpigmentation Scale.17 Although currently not widely available, this tool could be further refined with additional skin hues.

Conclusion

Other investigators have criticized the various limitations of FST, including physician vs patient assessment, interview vs questionnaire, and phrasing of questions on skin type.23 Our findings suggest that medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with FST. Two authors of this report (O.R.W. and J.E.D.) are medical students with skin of color and frequently have observed the addition of FST to the medical records of patients who were not receiving phototherapy as a proxy for race. We believe that more culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed and, in the interim, the original intent of FST should be emphasized and incorporated in medical school and resident education.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Adewole Adamson, MD (Austin, Texas), for discussion and feedback.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

- Everett JS, Budescu M, Sommers MS. Making sense of skin color in clinical care. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21:495-516.

- Eilers S, Bach DQ, Gaber R, et al. Accuracy of self-report in assessingFitzpatrick skin phototypes I through VI. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1289-1294.

- He SY, McCulloch CE, Boscardin WJ, et al. Self-reported pigmentary phenotypes and race are significant but incomplete predictors of Fitzpatrick skin phototype in an ethnically diverse population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:731-737.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Leenutaphong V. Relationship between skin color and cutaneous response to ultraviolet radiation in Thai. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1996;11:198-203.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

- Baumann L. Understanding and treating various skin types: the Baumann Skin Type Indicator. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:359-373.

- Fanous N. A new patient classification for laser resurfacing and peels: predicting responses, risks, and results. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26:99-104.

- Glogau RG. Chemical peeling and aging skin. J Geriatric Dermatol. 1994;2:30-35.

- Goldman M. Universal classification of skin type. In: Shiffman M, Mirrafati S, Lam S, et al, eds. Simplified Facial Rejuvenation. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008:47-50.

- Kawada A. UVB-induced erythema, delayed tanning, and UVA-induced immediate tanning in Japanese skin. Photodermatol. 1986;3:327-333.

- Lancer HA. Lancer Ethnicity Scale (LES). Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22:9.

- Sharma VK, Gupta V, Jangid BL, et al. Modification of the Fitzpatrick system of skin phototype classification for the Indian population, and its correlation with narrowband diffuse reflectance spectrophotometry. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:274-280.

- Roberts WE. The Roberts Skin Type Classification System. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:452-456.

- Taylor SC, Arsonnaud S, Czernielewski J. The Taylor hyperpigmentation scale: a new visual assessment tool for the evaluation of skin color and pigmentation. Cutis. 2005;76:270-274.

- Treesirichod A, Chansakulporn S, Wattanapan P. Correlation between skin color evaluation by skin color scale chart and narrowband reflectance spectrophotometer. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:339-342.

- Willis I, Earles RM. A new classification system relevant to people of African descent. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2005;18:209-216.

- Reeder AI, Hammond VA, Gray AR. Questionnaire items to assess skin color and erythemal sensitivity: reliability, validity, and “the dark shift.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1167-1173.

- Dwyer T, Muller HK, Blizzard L, et al. The use of spectrophotometry to estimate melanin density in Caucasians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:203-206.

- Pershing LK, Tirumala VP, Nelson JL, et al. Reflectance spectrophotometer: the dermatologists’ sphygmomanometer for skin phototyping? J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1633-1640.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) is the most commonly used classification system in dermatologic practice. It was developed by Thomas B. Fitzpatrick, MD, PhD, in 1975 to assess the propensity of the skin to burn during phototherapy.1 Fitzpatrick skin type also can be used to assess the clinical benefits and efficacy of cosmetic procedures, including laser hair removal, chemical peel and dermabrasion, tattoo removal, spray tanning, and laser resurfacing for acne scarring.2 The original FST classifications included skin types I through IV; skin types V and VI were later added to include individuals of Asian, Indian, and African origin.1 As a result, FST often is used by providers as a means of describing constitutive skin color and ethnicity.3

How did FST transition from describing the propensity of the skin to burn from UV light exposure to categorizing skin color, thereby becoming a proxy for race? It most likely occurred because there has not been another widely adopted classification system for describing skin color that can be applied to all skin types. Even when the FST classification scale is used as intended, there are inconsistencies with its accuracy; for example, self-reported FSTs have correlated poorly with sunburn risk as well as physician-reported FSTs.4,5 Although physician-reported FSTs have been demonstrated to correlate with race, race does not consistently correlate with objective measures of pigmentation or self-reported FSTs.5 For example, Japanese women often self-identify as FST type II, but Asian skin generally is considered to be nonwhite.1 Fitzpatrick himself acknowledged that race and ethnicity are cultural and political terms with no scientific basis.6 Fitzpatrick skin type also has been demonstrated to correlate poorly with constitutive skin color and minimal erythema dose values.7

We conducted an anonymous survey of dermatologists and dermatology trainees to evaluate how providers use FST in their clinical practice as well as how it is used to describe race and ethnicity.

Methods

The survey was distributed electronically to dermatologists and dermatology trainees from March 13 to March 28, 2019, using the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserv, as well as in person at the annual Skin of Color Society meeting in Washington, DC, on February 28, 2019. The 8-item survey included questions about physician demographics (ie, primary practice setting, board certification, and geographic location); whether the respondent identified as an individual with skin of color; and how the respondent utilized FST in clinical notes (ie, describing race/ethnicity, skin cancer risk, and constitutive [baseline] skin color; determining initial phototherapy dosage and suitability for laser treatments, and likelihood of skin burning). A t test was used to determine whether dermatologists who identified as having skin of color utilized FST differently.

Results

A total of 141 surveys were returned, and 140 respondents were included in the final analysis. Given the methods used to distribute the survey, a response rate could not be calculated. The respondents included more board-certified dermatologists (70%) than dermatology trainees (30%). Ninety-three percent of respondents indicated an academic institution as their primary practice location. Notably, 26% of respondents self-identified as having skin of color.

Forty-one percent of all respondents agreed that FST should be included in their clinical documentation. In response to the question “In what scenarios would you refer to FST in a clinical note?” 31% said they used FST to describe patients’ race or ethnicity, 47% used it to describe patients’ constitutive skin color, and 22% utilized it in both scenarios. Respondents who did not identify as having skin of color were more likely to use FST to describe constitutive skin color, though this finding was not statistically significant (P=.063). Anecdotally, providers also included FST in clinical notes on postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, and treatment with cryotherapy.

Comment

The US Census Bureau has estimated that half of the US population will be of non-European descent by 2050.8 As racial and ethnic distinctions continue to be blurred, attempts to include all nonwhite skin types under the umbrella term skin of color becomes increasingly problematic. The true number of skin colors is unknown but likely is infinite, as Brazilian artist Angélica Dass has demonstrated with her photographic project “Humanae” (Figure). Given this shift in demographics and the limitations of the FST, alternative methods of describing skin color must be developed.

© Angélica Dass | Humanae Work in Progress (Courtesy of the artist).

The results of our survey suggest that approximately one-third to half of academic dermatologists/dermatology trainees use FST to describe race/ethnicity and/or constitutive skin color. This misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color. Additionally, misuse of FST in academic settings may be problematic and confusing for medical students who may learn to use this common dermatologic tool outside of its original intent.

We acknowledge that the conundrum of how to classify individuals with nonwhite skin or skin of color is not simply answered. Several alternative skin classification models have been proposed to improve the sensitivity and specificity of identifying patients with skin of color (Table). Refining FST classification is one approach. Employing terms such as skin irritation, tenderness, itching, or skin becoming darker from sun exposure rather than painful burn or tanning may result in better identification.1,4 A study conducted in India modified the FST questionnaire to acknowledge cultural behaviors.15 Because lighter skin is culturally valued in this population, patient experience with purposeful sun exposure was limited; thus, the questionnaire was modified to remove questions on the use of tanning booths and/or creams as well as sun exposure and instead included more objective questions regarding dark brown eye color, black and dark brown hair color, and dark brown skin color.15 Other studies have suggested that patient-reported photosensitivity assessed via a questionnaire is a valid measure for assessing FST but is associated with an overestimation of skin color, known as “the dark shift.”20

Sharma et al15 utilized reflectance spectrophotometry as an objective measure of melanin and skin erythema. The melanin index consistently showed a positive correlation with FSTs as opposed to the erythema index, which correlated poorly.15 Although reflectance spectrometry accurately identifies skin color in patients with nonwhite skin,21,22 it is an impractical and cost-prohibitive tool for daily practice. A more practical tool for the clinical setting would be a visual color scale with skin hues spanning FST types I to VI, including bands of increasingly darker gradations that would be particularly useful in assessing skin of color. Once such tool is the Taylor Hyperpigmentation Scale.17 Although currently not widely available, this tool could be further refined with additional skin hues.

Conclusion

Other investigators have criticized the various limitations of FST, including physician vs patient assessment, interview vs questionnaire, and phrasing of questions on skin type.23 Our findings suggest that medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with FST. Two authors of this report (O.R.W. and J.E.D.) are medical students with skin of color and frequently have observed the addition of FST to the medical records of patients who were not receiving phototherapy as a proxy for race. We believe that more culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed and, in the interim, the original intent of FST should be emphasized and incorporated in medical school and resident education.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Adewole Adamson, MD (Austin, Texas), for discussion and feedback.

Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) is the most commonly used classification system in dermatologic practice. It was developed by Thomas B. Fitzpatrick, MD, PhD, in 1975 to assess the propensity of the skin to burn during phototherapy.1 Fitzpatrick skin type also can be used to assess the clinical benefits and efficacy of cosmetic procedures, including laser hair removal, chemical peel and dermabrasion, tattoo removal, spray tanning, and laser resurfacing for acne scarring.2 The original FST classifications included skin types I through IV; skin types V and VI were later added to include individuals of Asian, Indian, and African origin.1 As a result, FST often is used by providers as a means of describing constitutive skin color and ethnicity.3

How did FST transition from describing the propensity of the skin to burn from UV light exposure to categorizing skin color, thereby becoming a proxy for race? It most likely occurred because there has not been another widely adopted classification system for describing skin color that can be applied to all skin types. Even when the FST classification scale is used as intended, there are inconsistencies with its accuracy; for example, self-reported FSTs have correlated poorly with sunburn risk as well as physician-reported FSTs.4,5 Although physician-reported FSTs have been demonstrated to correlate with race, race does not consistently correlate with objective measures of pigmentation or self-reported FSTs.5 For example, Japanese women often self-identify as FST type II, but Asian skin generally is considered to be nonwhite.1 Fitzpatrick himself acknowledged that race and ethnicity are cultural and political terms with no scientific basis.6 Fitzpatrick skin type also has been demonstrated to correlate poorly with constitutive skin color and minimal erythema dose values.7

We conducted an anonymous survey of dermatologists and dermatology trainees to evaluate how providers use FST in their clinical practice as well as how it is used to describe race and ethnicity.

Methods

The survey was distributed electronically to dermatologists and dermatology trainees from March 13 to March 28, 2019, using the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserv, as well as in person at the annual Skin of Color Society meeting in Washington, DC, on February 28, 2019. The 8-item survey included questions about physician demographics (ie, primary practice setting, board certification, and geographic location); whether the respondent identified as an individual with skin of color; and how the respondent utilized FST in clinical notes (ie, describing race/ethnicity, skin cancer risk, and constitutive [baseline] skin color; determining initial phototherapy dosage and suitability for laser treatments, and likelihood of skin burning). A t test was used to determine whether dermatologists who identified as having skin of color utilized FST differently.

Results

A total of 141 surveys were returned, and 140 respondents were included in the final analysis. Given the methods used to distribute the survey, a response rate could not be calculated. The respondents included more board-certified dermatologists (70%) than dermatology trainees (30%). Ninety-three percent of respondents indicated an academic institution as their primary practice location. Notably, 26% of respondents self-identified as having skin of color.

Forty-one percent of all respondents agreed that FST should be included in their clinical documentation. In response to the question “In what scenarios would you refer to FST in a clinical note?” 31% said they used FST to describe patients’ race or ethnicity, 47% used it to describe patients’ constitutive skin color, and 22% utilized it in both scenarios. Respondents who did not identify as having skin of color were more likely to use FST to describe constitutive skin color, though this finding was not statistically significant (P=.063). Anecdotally, providers also included FST in clinical notes on postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, and treatment with cryotherapy.

Comment

The US Census Bureau has estimated that half of the US population will be of non-European descent by 2050.8 As racial and ethnic distinctions continue to be blurred, attempts to include all nonwhite skin types under the umbrella term skin of color becomes increasingly problematic. The true number of skin colors is unknown but likely is infinite, as Brazilian artist Angélica Dass has demonstrated with her photographic project “Humanae” (Figure). Given this shift in demographics and the limitations of the FST, alternative methods of describing skin color must be developed.

© Angélica Dass | Humanae Work in Progress (Courtesy of the artist).

The results of our survey suggest that approximately one-third to half of academic dermatologists/dermatology trainees use FST to describe race/ethnicity and/or constitutive skin color. This misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color. Additionally, misuse of FST in academic settings may be problematic and confusing for medical students who may learn to use this common dermatologic tool outside of its original intent.

We acknowledge that the conundrum of how to classify individuals with nonwhite skin or skin of color is not simply answered. Several alternative skin classification models have been proposed to improve the sensitivity and specificity of identifying patients with skin of color (Table). Refining FST classification is one approach. Employing terms such as skin irritation, tenderness, itching, or skin becoming darker from sun exposure rather than painful burn or tanning may result in better identification.1,4 A study conducted in India modified the FST questionnaire to acknowledge cultural behaviors.15 Because lighter skin is culturally valued in this population, patient experience with purposeful sun exposure was limited; thus, the questionnaire was modified to remove questions on the use of tanning booths and/or creams as well as sun exposure and instead included more objective questions regarding dark brown eye color, black and dark brown hair color, and dark brown skin color.15 Other studies have suggested that patient-reported photosensitivity assessed via a questionnaire is a valid measure for assessing FST but is associated with an overestimation of skin color, known as “the dark shift.”20

Sharma et al15 utilized reflectance spectrophotometry as an objective measure of melanin and skin erythema. The melanin index consistently showed a positive correlation with FSTs as opposed to the erythema index, which correlated poorly.15 Although reflectance spectrometry accurately identifies skin color in patients with nonwhite skin,21,22 it is an impractical and cost-prohibitive tool for daily practice. A more practical tool for the clinical setting would be a visual color scale with skin hues spanning FST types I to VI, including bands of increasingly darker gradations that would be particularly useful in assessing skin of color. Once such tool is the Taylor Hyperpigmentation Scale.17 Although currently not widely available, this tool could be further refined with additional skin hues.

Conclusion

Other investigators have criticized the various limitations of FST, including physician vs patient assessment, interview vs questionnaire, and phrasing of questions on skin type.23 Our findings suggest that medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with FST. Two authors of this report (O.R.W. and J.E.D.) are medical students with skin of color and frequently have observed the addition of FST to the medical records of patients who were not receiving phototherapy as a proxy for race. We believe that more culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed and, in the interim, the original intent of FST should be emphasized and incorporated in medical school and resident education.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Adewole Adamson, MD (Austin, Texas), for discussion and feedback.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

- Everett JS, Budescu M, Sommers MS. Making sense of skin color in clinical care. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21:495-516.

- Eilers S, Bach DQ, Gaber R, et al. Accuracy of self-report in assessingFitzpatrick skin phototypes I through VI. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1289-1294.

- He SY, McCulloch CE, Boscardin WJ, et al. Self-reported pigmentary phenotypes and race are significant but incomplete predictors of Fitzpatrick skin phototype in an ethnically diverse population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:731-737.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Leenutaphong V. Relationship between skin color and cutaneous response to ultraviolet radiation in Thai. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1996;11:198-203.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

- Baumann L. Understanding and treating various skin types: the Baumann Skin Type Indicator. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:359-373.

- Fanous N. A new patient classification for laser resurfacing and peels: predicting responses, risks, and results. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26:99-104.

- Glogau RG. Chemical peeling and aging skin. J Geriatric Dermatol. 1994;2:30-35.

- Goldman M. Universal classification of skin type. In: Shiffman M, Mirrafati S, Lam S, et al, eds. Simplified Facial Rejuvenation. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008:47-50.

- Kawada A. UVB-induced erythema, delayed tanning, and UVA-induced immediate tanning in Japanese skin. Photodermatol. 1986;3:327-333.

- Lancer HA. Lancer Ethnicity Scale (LES). Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22:9.

- Sharma VK, Gupta V, Jangid BL, et al. Modification of the Fitzpatrick system of skin phototype classification for the Indian population, and its correlation with narrowband diffuse reflectance spectrophotometry. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:274-280.

- Roberts WE. The Roberts Skin Type Classification System. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:452-456.

- Taylor SC, Arsonnaud S, Czernielewski J. The Taylor hyperpigmentation scale: a new visual assessment tool for the evaluation of skin color and pigmentation. Cutis. 2005;76:270-274.

- Treesirichod A, Chansakulporn S, Wattanapan P. Correlation between skin color evaluation by skin color scale chart and narrowband reflectance spectrophotometer. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:339-342.

- Willis I, Earles RM. A new classification system relevant to people of African descent. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2005;18:209-216.

- Reeder AI, Hammond VA, Gray AR. Questionnaire items to assess skin color and erythemal sensitivity: reliability, validity, and “the dark shift.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1167-1173.

- Dwyer T, Muller HK, Blizzard L, et al. The use of spectrophotometry to estimate melanin density in Caucasians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:203-206.

- Pershing LK, Tirumala VP, Nelson JL, et al. Reflectance spectrophotometer: the dermatologists’ sphygmomanometer for skin phototyping? J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1633-1640.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

- Everett JS, Budescu M, Sommers MS. Making sense of skin color in clinical care. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21:495-516.

- Eilers S, Bach DQ, Gaber R, et al. Accuracy of self-report in assessingFitzpatrick skin phototypes I through VI. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1289-1294.

- He SY, McCulloch CE, Boscardin WJ, et al. Self-reported pigmentary phenotypes and race are significant but incomplete predictors of Fitzpatrick skin phototype in an ethnically diverse population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:731-737.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Leenutaphong V. Relationship between skin color and cutaneous response to ultraviolet radiation in Thai. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1996;11:198-203.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

- Baumann L. Understanding and treating various skin types: the Baumann Skin Type Indicator. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:359-373.

- Fanous N. A new patient classification for laser resurfacing and peels: predicting responses, risks, and results. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26:99-104.

- Glogau RG. Chemical peeling and aging skin. J Geriatric Dermatol. 1994;2:30-35.

- Goldman M. Universal classification of skin type. In: Shiffman M, Mirrafati S, Lam S, et al, eds. Simplified Facial Rejuvenation. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008:47-50.

- Kawada A. UVB-induced erythema, delayed tanning, and UVA-induced immediate tanning in Japanese skin. Photodermatol. 1986;3:327-333.

- Lancer HA. Lancer Ethnicity Scale (LES). Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22:9.

- Sharma VK, Gupta V, Jangid BL, et al. Modification of the Fitzpatrick system of skin phototype classification for the Indian population, and its correlation with narrowband diffuse reflectance spectrophotometry. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:274-280.

- Roberts WE. The Roberts Skin Type Classification System. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:452-456.

- Taylor SC, Arsonnaud S, Czernielewski J. The Taylor hyperpigmentation scale: a new visual assessment tool for the evaluation of skin color and pigmentation. Cutis. 2005;76:270-274.

- Treesirichod A, Chansakulporn S, Wattanapan P. Correlation between skin color evaluation by skin color scale chart and narrowband reflectance spectrophotometer. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:339-342.

- Willis I, Earles RM. A new classification system relevant to people of African descent. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2005;18:209-216.

- Reeder AI, Hammond VA, Gray AR. Questionnaire items to assess skin color and erythemal sensitivity: reliability, validity, and “the dark shift.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1167-1173.

- Dwyer T, Muller HK, Blizzard L, et al. The use of spectrophotometry to estimate melanin density in Caucasians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:203-206.

- Pershing LK, Tirumala VP, Nelson JL, et al. Reflectance spectrophotometer: the dermatologists’ sphygmomanometer for skin phototyping? J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1633-1640.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

Practice Points

- Medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with Fitzpatrick skin type (FST).

- Misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color.

- Although alternative skin type classification systems have been proposed, more clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed.

Barriers and Job Satisfaction Among Dermatology Hospitalists