User login

Tanning Attitudes and Behaviors in Adolescents and Young Adults

Intentional tanning—through sun exposure and tanning beds—is an easily avoidable contributor to skin cancer development and an important area for public education. Since the advent of social media, a correlation between social media use and increased indoor tanning behaviors has been reported.1 In 2010, 11.3% of US adults aged 18 to 29 years reported using a tanning bed in the last 12 months.2 The American Academy of Dermatology first published their “Position Statement on Indoor Tanning” in 1998, endorsing a ban on the sale of indoor tanning equipment for nonmedical purposes.3

Although there has been no outright ban on indoor tanning, regulations have been put in place in many states—including Texas, where (as of 2013) a person younger than 18 years must have written consent from their parent(s) to use a tanning bed. Despite efforts of organizations including the American Academy of Dermatology and the government to educate the public on skin cancer prevention and sun safety, the skin cancer rate has been steadily increasing over the last 20 years.

There is a constant campaign among dermatologists to educate their patients on how to reduce or avoid the risk for skin cancer, including the use of sunscreen and avoidance of tanning. Adolescents and young adults are an especially important demographic to reach and educate because increased UV light exposure during these years leads to a greatly increased risk for skin cancer later in life.4 Data on the overall prevalence of tanning and the demographics of participation in tanning activities are important to capture and can be used to efficiently target higher-risk populations.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the attitudes and behaviors of adolescents and young adults regarding sun protection and tanning. We also aimed to determine which avenues, including social media, would be most effective at educating about skin cancer awareness and sun protection to the higher-risk younger population.

Materials and Methods

We developed an institutional review board–approved protocol for the prospective collection of data from registered patients at the dermatology clinic of the Mays Cancer Center at the University of Texas Health at San Antonio. A paper survey containing 15 rating-scale questions was administered to 60 patients aged 13 to 27 years. Surveys were administered during intake, prior to the patients’ visit with a dermatologist; all visits were of a functional (not cosmetic) nature. Data collection spanned June to August 2018. Survey results were entered into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software for qualitative analysis.

Results

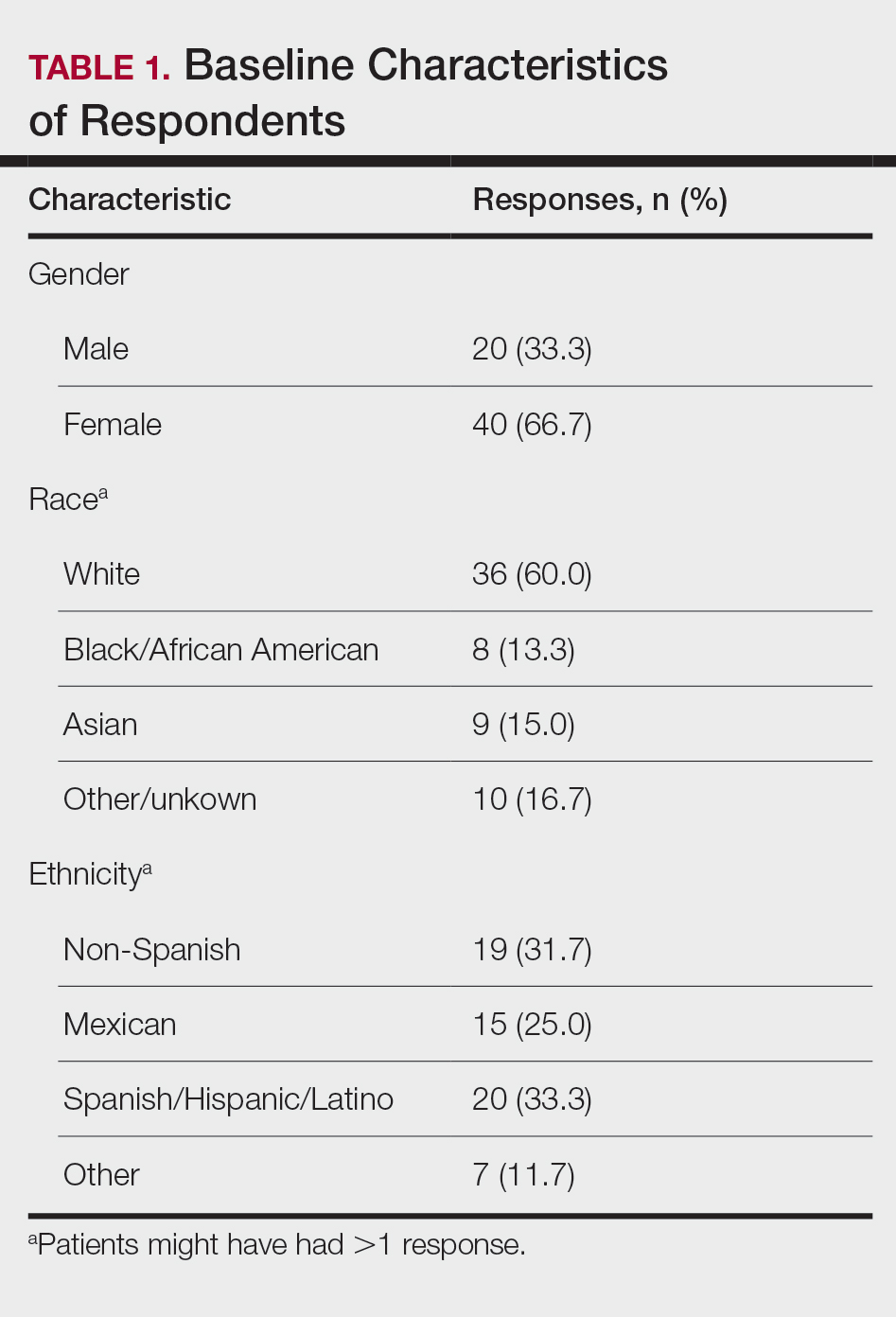

Sixty patients responded to the survey. The mean age of respondents was 19.5 years. No surveys were excluded from the data set. Table 1 provides baseline characteristics of respondents. Some respondents left questions unanswered, resulting in questions with fewer than 60 responses.

Among respondents to the survey, 70% (42/60) reported it is very important to protect their skin from sun exposure, and 30% (18/60) reported it is somewhat important. Regarding sunscreen use, 70% (42/60) indicated they use sunscreen only before outdoor activities, 12% (7/60) use sunscreen daily, and 17% (10/60) never use sunscreen. Of those who use sunscreen, 52% (28/54) do so to prevent skin damage and aging and 44% (24/54) to prevent skin cancer. Twenty-three percent (13/56) of respondents reported finding tanned skin attractive; 26% (14/55) reported wanting to be tan. Looking at race, 28% (10/36) of Whites, 25% (5/20) of Spanish/Hispanic/Latinos, and 22% (2/9) of Asians found tanned skin attractive; no Black respondents found tanned skin attractive.

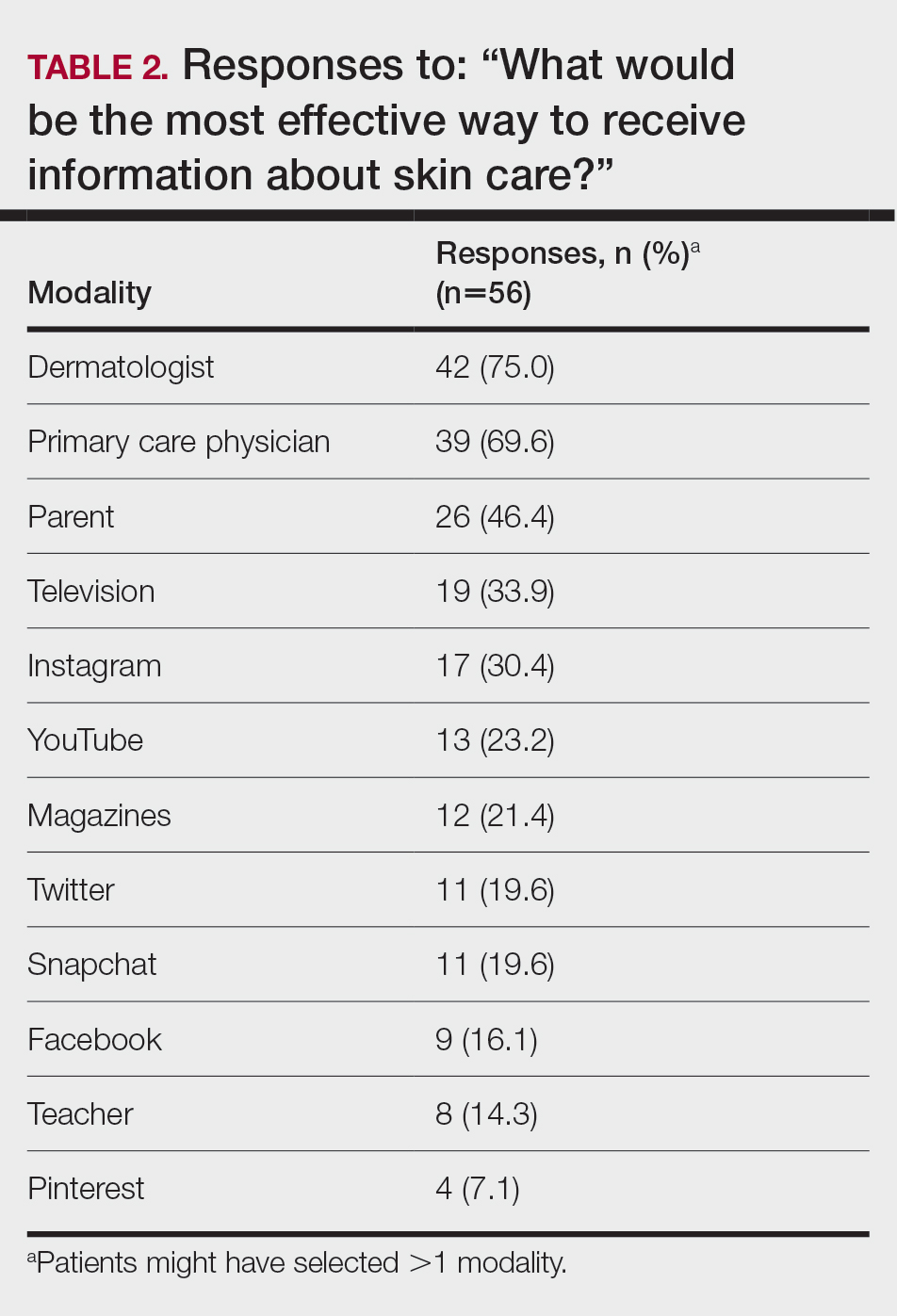

Regarding tanning, 12% (7/57) reported using a tanning bed in their lifetime and 4% (2/57) in the last year; 34% (19/56) reported deliberately tanning outdoors; and 9% (5/56) reported using sunless or spray-on tanning. Dermatologists (75% [42/56]), primary care physicians (69.6% [39/56]), and parents (46.4% [26/56]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education; among media modalities, television (33.9% [19/56]), Instagram (30.4% [17/60]), and YouTube (23.2% [13/60]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education (Table 2).

Comment

Perceptions of Tanning

Almost one-quarter of respondents found tanned skin attractive, which might reflect a shift from prior generations. Compared to the 11% of respondents in the 2010 survey,2 only 3.5% (2/57) of our respondents reported using a tanning bed in the last year, which could reflect the results of recent Texas legislation restricting the use of tanning beds by adolescents.

An alarming number of respondents reported going outdoors with the intention of tanning; although it appears that indoor tanning education has been successful, this finding shows that there is still a need for sun protection education because outdoor tanning is not a suitable alternative. A small number of respondents reported getting a sunless or spray-on tan, which is a risk-free alternative to indoor tanning.

Despite all respondents stating that protecting skin from the sun is important, most respondents surveyed do not use sunscreen daily. More respondents use sunscreen to prevent damage and aging than to prevent skin cancer. Young people might be more alarmed by the threat of early aging and losing their “youthful appearance” than by the possibility of developing skin cancer in the distant future. This discrepancy might indicate a lack of knowledge and be an important focus for future education efforts.

Perceptions of Trustworthiness of Education Sources

Our findings show dermatologists and primary care physicians are important educators on skin protection. Primary care physicians should remain vigilant to recognize at-risk patients who would benefit from skin protection education, especially those who do not see a dermatologist. Education of young people focusing on their concern over maintaining a youthful appearance instead of the possibility of developing skin cancer in the future might be more effective.

Although education provided by a physician is effective, using media—particularly social media—might be more efficient. Television, Instagram, and YouTube were listed by respondents as the 3 most preferred media outlets for skin health education, which shows important areas of focus for future advertising. Facebook was listed at a surprisingly low level, possibly showing the change in use of certain social media websites among this age group. According to the Pew Research Center, the most widely used social media apps among young adults aged 18 to 29 years are YouTube (91%), Facebook (63%), Instagram (67%), and Snapchat (62%). More than half of the same demographic visit Facebook (74%), Instagram (63%), Snapchat (61%), and YouTube (51%) daily.5 Although respondents to our survey were not specifically asked about the frequency of their use of social media and our data set includes patients younger than 18 years, we know that social media use has been increasing over the last decade among adolescents.1 Therefore, we assume that more than one-half of respondents to our survey use their reported social media platforms daily.

Social media is an underused medium for skin cancer prevention education and can reach those who do not regularly see a dermatologist. Unlike printed pamphlets and posters, advertisements through social media can use metrics such as age, race, gender, and interests to target high-risk individuals.

Study Limitations

This was a single-site study of currently enrolled dermatology patients who might be more aware of skin protection than the general population because they are being treated by a dermatologist. Survey questions regarding demographics, required by our institution, could not effectively differentiate Hispanic and White patients. Respondents could have been subject to the Hawthorne effect—awareness that their behavior is being observed—when responding to the survey because it was administered in the office prior to being seen by a dermatologist.

- Falzone AE, Brindis CD, Chren M-M, et al. Teens, tweets, and tanning beds: rethinking the use of social media for skin cancer prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3 suppl 1):S86-S94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of indoor tanning devices by adults—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:323-326.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on indoor tanning. Amended November 14, 2009. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Indoor%20Tanning%2011-16-09.pdf?

- American Academy of Dermatology. Indoor tanning. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-indoor-tanning

- Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center; April 10, 2019. Accessed April 16, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/

Intentional tanning—through sun exposure and tanning beds—is an easily avoidable contributor to skin cancer development and an important area for public education. Since the advent of social media, a correlation between social media use and increased indoor tanning behaviors has been reported.1 In 2010, 11.3% of US adults aged 18 to 29 years reported using a tanning bed in the last 12 months.2 The American Academy of Dermatology first published their “Position Statement on Indoor Tanning” in 1998, endorsing a ban on the sale of indoor tanning equipment for nonmedical purposes.3

Although there has been no outright ban on indoor tanning, regulations have been put in place in many states—including Texas, where (as of 2013) a person younger than 18 years must have written consent from their parent(s) to use a tanning bed. Despite efforts of organizations including the American Academy of Dermatology and the government to educate the public on skin cancer prevention and sun safety, the skin cancer rate has been steadily increasing over the last 20 years.

There is a constant campaign among dermatologists to educate their patients on how to reduce or avoid the risk for skin cancer, including the use of sunscreen and avoidance of tanning. Adolescents and young adults are an especially important demographic to reach and educate because increased UV light exposure during these years leads to a greatly increased risk for skin cancer later in life.4 Data on the overall prevalence of tanning and the demographics of participation in tanning activities are important to capture and can be used to efficiently target higher-risk populations.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the attitudes and behaviors of adolescents and young adults regarding sun protection and tanning. We also aimed to determine which avenues, including social media, would be most effective at educating about skin cancer awareness and sun protection to the higher-risk younger population.

Materials and Methods

We developed an institutional review board–approved protocol for the prospective collection of data from registered patients at the dermatology clinic of the Mays Cancer Center at the University of Texas Health at San Antonio. A paper survey containing 15 rating-scale questions was administered to 60 patients aged 13 to 27 years. Surveys were administered during intake, prior to the patients’ visit with a dermatologist; all visits were of a functional (not cosmetic) nature. Data collection spanned June to August 2018. Survey results were entered into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software for qualitative analysis.

Results

Sixty patients responded to the survey. The mean age of respondents was 19.5 years. No surveys were excluded from the data set. Table 1 provides baseline characteristics of respondents. Some respondents left questions unanswered, resulting in questions with fewer than 60 responses.

Among respondents to the survey, 70% (42/60) reported it is very important to protect their skin from sun exposure, and 30% (18/60) reported it is somewhat important. Regarding sunscreen use, 70% (42/60) indicated they use sunscreen only before outdoor activities, 12% (7/60) use sunscreen daily, and 17% (10/60) never use sunscreen. Of those who use sunscreen, 52% (28/54) do so to prevent skin damage and aging and 44% (24/54) to prevent skin cancer. Twenty-three percent (13/56) of respondents reported finding tanned skin attractive; 26% (14/55) reported wanting to be tan. Looking at race, 28% (10/36) of Whites, 25% (5/20) of Spanish/Hispanic/Latinos, and 22% (2/9) of Asians found tanned skin attractive; no Black respondents found tanned skin attractive.

Regarding tanning, 12% (7/57) reported using a tanning bed in their lifetime and 4% (2/57) in the last year; 34% (19/56) reported deliberately tanning outdoors; and 9% (5/56) reported using sunless or spray-on tanning. Dermatologists (75% [42/56]), primary care physicians (69.6% [39/56]), and parents (46.4% [26/56]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education; among media modalities, television (33.9% [19/56]), Instagram (30.4% [17/60]), and YouTube (23.2% [13/60]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education (Table 2).

Comment

Perceptions of Tanning

Almost one-quarter of respondents found tanned skin attractive, which might reflect a shift from prior generations. Compared to the 11% of respondents in the 2010 survey,2 only 3.5% (2/57) of our respondents reported using a tanning bed in the last year, which could reflect the results of recent Texas legislation restricting the use of tanning beds by adolescents.

An alarming number of respondents reported going outdoors with the intention of tanning; although it appears that indoor tanning education has been successful, this finding shows that there is still a need for sun protection education because outdoor tanning is not a suitable alternative. A small number of respondents reported getting a sunless or spray-on tan, which is a risk-free alternative to indoor tanning.

Despite all respondents stating that protecting skin from the sun is important, most respondents surveyed do not use sunscreen daily. More respondents use sunscreen to prevent damage and aging than to prevent skin cancer. Young people might be more alarmed by the threat of early aging and losing their “youthful appearance” than by the possibility of developing skin cancer in the distant future. This discrepancy might indicate a lack of knowledge and be an important focus for future education efforts.

Perceptions of Trustworthiness of Education Sources

Our findings show dermatologists and primary care physicians are important educators on skin protection. Primary care physicians should remain vigilant to recognize at-risk patients who would benefit from skin protection education, especially those who do not see a dermatologist. Education of young people focusing on their concern over maintaining a youthful appearance instead of the possibility of developing skin cancer in the future might be more effective.

Although education provided by a physician is effective, using media—particularly social media—might be more efficient. Television, Instagram, and YouTube were listed by respondents as the 3 most preferred media outlets for skin health education, which shows important areas of focus for future advertising. Facebook was listed at a surprisingly low level, possibly showing the change in use of certain social media websites among this age group. According to the Pew Research Center, the most widely used social media apps among young adults aged 18 to 29 years are YouTube (91%), Facebook (63%), Instagram (67%), and Snapchat (62%). More than half of the same demographic visit Facebook (74%), Instagram (63%), Snapchat (61%), and YouTube (51%) daily.5 Although respondents to our survey were not specifically asked about the frequency of their use of social media and our data set includes patients younger than 18 years, we know that social media use has been increasing over the last decade among adolescents.1 Therefore, we assume that more than one-half of respondents to our survey use their reported social media platforms daily.

Social media is an underused medium for skin cancer prevention education and can reach those who do not regularly see a dermatologist. Unlike printed pamphlets and posters, advertisements through social media can use metrics such as age, race, gender, and interests to target high-risk individuals.

Study Limitations

This was a single-site study of currently enrolled dermatology patients who might be more aware of skin protection than the general population because they are being treated by a dermatologist. Survey questions regarding demographics, required by our institution, could not effectively differentiate Hispanic and White patients. Respondents could have been subject to the Hawthorne effect—awareness that their behavior is being observed—when responding to the survey because it was administered in the office prior to being seen by a dermatologist.

Intentional tanning—through sun exposure and tanning beds—is an easily avoidable contributor to skin cancer development and an important area for public education. Since the advent of social media, a correlation between social media use and increased indoor tanning behaviors has been reported.1 In 2010, 11.3% of US adults aged 18 to 29 years reported using a tanning bed in the last 12 months.2 The American Academy of Dermatology first published their “Position Statement on Indoor Tanning” in 1998, endorsing a ban on the sale of indoor tanning equipment for nonmedical purposes.3

Although there has been no outright ban on indoor tanning, regulations have been put in place in many states—including Texas, where (as of 2013) a person younger than 18 years must have written consent from their parent(s) to use a tanning bed. Despite efforts of organizations including the American Academy of Dermatology and the government to educate the public on skin cancer prevention and sun safety, the skin cancer rate has been steadily increasing over the last 20 years.

There is a constant campaign among dermatologists to educate their patients on how to reduce or avoid the risk for skin cancer, including the use of sunscreen and avoidance of tanning. Adolescents and young adults are an especially important demographic to reach and educate because increased UV light exposure during these years leads to a greatly increased risk for skin cancer later in life.4 Data on the overall prevalence of tanning and the demographics of participation in tanning activities are important to capture and can be used to efficiently target higher-risk populations.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the attitudes and behaviors of adolescents and young adults regarding sun protection and tanning. We also aimed to determine which avenues, including social media, would be most effective at educating about skin cancer awareness and sun protection to the higher-risk younger population.

Materials and Methods

We developed an institutional review board–approved protocol for the prospective collection of data from registered patients at the dermatology clinic of the Mays Cancer Center at the University of Texas Health at San Antonio. A paper survey containing 15 rating-scale questions was administered to 60 patients aged 13 to 27 years. Surveys were administered during intake, prior to the patients’ visit with a dermatologist; all visits were of a functional (not cosmetic) nature. Data collection spanned June to August 2018. Survey results were entered into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software for qualitative analysis.

Results

Sixty patients responded to the survey. The mean age of respondents was 19.5 years. No surveys were excluded from the data set. Table 1 provides baseline characteristics of respondents. Some respondents left questions unanswered, resulting in questions with fewer than 60 responses.

Among respondents to the survey, 70% (42/60) reported it is very important to protect their skin from sun exposure, and 30% (18/60) reported it is somewhat important. Regarding sunscreen use, 70% (42/60) indicated they use sunscreen only before outdoor activities, 12% (7/60) use sunscreen daily, and 17% (10/60) never use sunscreen. Of those who use sunscreen, 52% (28/54) do so to prevent skin damage and aging and 44% (24/54) to prevent skin cancer. Twenty-three percent (13/56) of respondents reported finding tanned skin attractive; 26% (14/55) reported wanting to be tan. Looking at race, 28% (10/36) of Whites, 25% (5/20) of Spanish/Hispanic/Latinos, and 22% (2/9) of Asians found tanned skin attractive; no Black respondents found tanned skin attractive.

Regarding tanning, 12% (7/57) reported using a tanning bed in their lifetime and 4% (2/57) in the last year; 34% (19/56) reported deliberately tanning outdoors; and 9% (5/56) reported using sunless or spray-on tanning. Dermatologists (75% [42/56]), primary care physicians (69.6% [39/56]), and parents (46.4% [26/56]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education; among media modalities, television (33.9% [19/56]), Instagram (30.4% [17/60]), and YouTube (23.2% [13/60]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education (Table 2).

Comment

Perceptions of Tanning

Almost one-quarter of respondents found tanned skin attractive, which might reflect a shift from prior generations. Compared to the 11% of respondents in the 2010 survey,2 only 3.5% (2/57) of our respondents reported using a tanning bed in the last year, which could reflect the results of recent Texas legislation restricting the use of tanning beds by adolescents.

An alarming number of respondents reported going outdoors with the intention of tanning; although it appears that indoor tanning education has been successful, this finding shows that there is still a need for sun protection education because outdoor tanning is not a suitable alternative. A small number of respondents reported getting a sunless or spray-on tan, which is a risk-free alternative to indoor tanning.

Despite all respondents stating that protecting skin from the sun is important, most respondents surveyed do not use sunscreen daily. More respondents use sunscreen to prevent damage and aging than to prevent skin cancer. Young people might be more alarmed by the threat of early aging and losing their “youthful appearance” than by the possibility of developing skin cancer in the distant future. This discrepancy might indicate a lack of knowledge and be an important focus for future education efforts.

Perceptions of Trustworthiness of Education Sources

Our findings show dermatologists and primary care physicians are important educators on skin protection. Primary care physicians should remain vigilant to recognize at-risk patients who would benefit from skin protection education, especially those who do not see a dermatologist. Education of young people focusing on their concern over maintaining a youthful appearance instead of the possibility of developing skin cancer in the future might be more effective.

Although education provided by a physician is effective, using media—particularly social media—might be more efficient. Television, Instagram, and YouTube were listed by respondents as the 3 most preferred media outlets for skin health education, which shows important areas of focus for future advertising. Facebook was listed at a surprisingly low level, possibly showing the change in use of certain social media websites among this age group. According to the Pew Research Center, the most widely used social media apps among young adults aged 18 to 29 years are YouTube (91%), Facebook (63%), Instagram (67%), and Snapchat (62%). More than half of the same demographic visit Facebook (74%), Instagram (63%), Snapchat (61%), and YouTube (51%) daily.5 Although respondents to our survey were not specifically asked about the frequency of their use of social media and our data set includes patients younger than 18 years, we know that social media use has been increasing over the last decade among adolescents.1 Therefore, we assume that more than one-half of respondents to our survey use their reported social media platforms daily.

Social media is an underused medium for skin cancer prevention education and can reach those who do not regularly see a dermatologist. Unlike printed pamphlets and posters, advertisements through social media can use metrics such as age, race, gender, and interests to target high-risk individuals.

Study Limitations

This was a single-site study of currently enrolled dermatology patients who might be more aware of skin protection than the general population because they are being treated by a dermatologist. Survey questions regarding demographics, required by our institution, could not effectively differentiate Hispanic and White patients. Respondents could have been subject to the Hawthorne effect—awareness that their behavior is being observed—when responding to the survey because it was administered in the office prior to being seen by a dermatologist.

- Falzone AE, Brindis CD, Chren M-M, et al. Teens, tweets, and tanning beds: rethinking the use of social media for skin cancer prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3 suppl 1):S86-S94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of indoor tanning devices by adults—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:323-326.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on indoor tanning. Amended November 14, 2009. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Indoor%20Tanning%2011-16-09.pdf?

- American Academy of Dermatology. Indoor tanning. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-indoor-tanning

- Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center; April 10, 2019. Accessed April 16, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/

- Falzone AE, Brindis CD, Chren M-M, et al. Teens, tweets, and tanning beds: rethinking the use of social media for skin cancer prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3 suppl 1):S86-S94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of indoor tanning devices by adults—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:323-326.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on indoor tanning. Amended November 14, 2009. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Indoor%20Tanning%2011-16-09.pdf?

- American Academy of Dermatology. Indoor tanning. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-indoor-tanning

- Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center; April 10, 2019. Accessed April 16, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatologists are the preferred educators of skin care for adolescents and young adults.

- Social media is an underused medium for skin cancer prevention education and can reach those who do not regularly see a dermatologist.

- Education of young people focusing on their concerns about maintaining a youthful appearance instead of the possibility of developing skin cancer in the future might be more effective.

Asymptomatic Hemorrhagic Lesions in an Anemic Woman

The Diagnosis: Bullous Amyloidosis

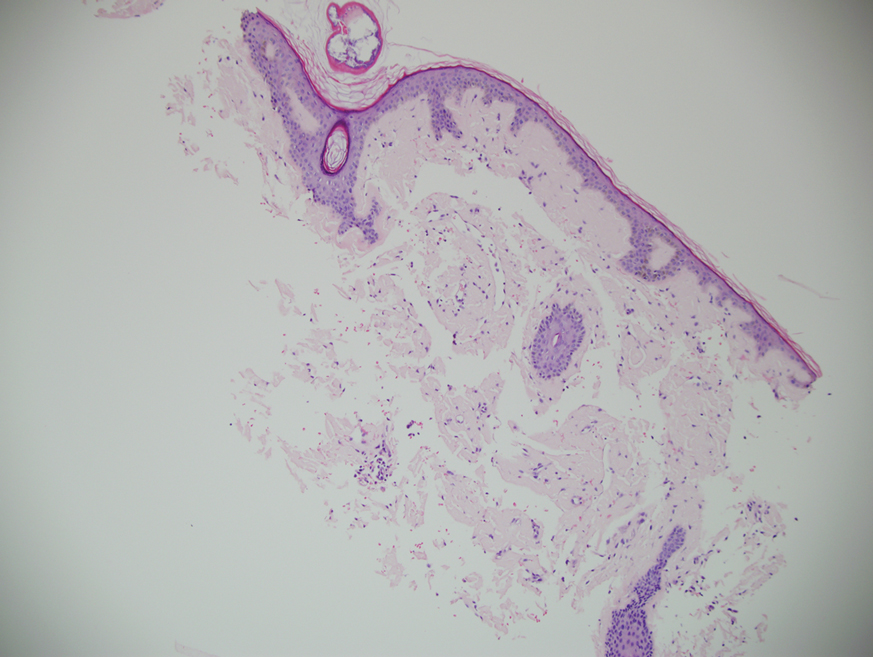

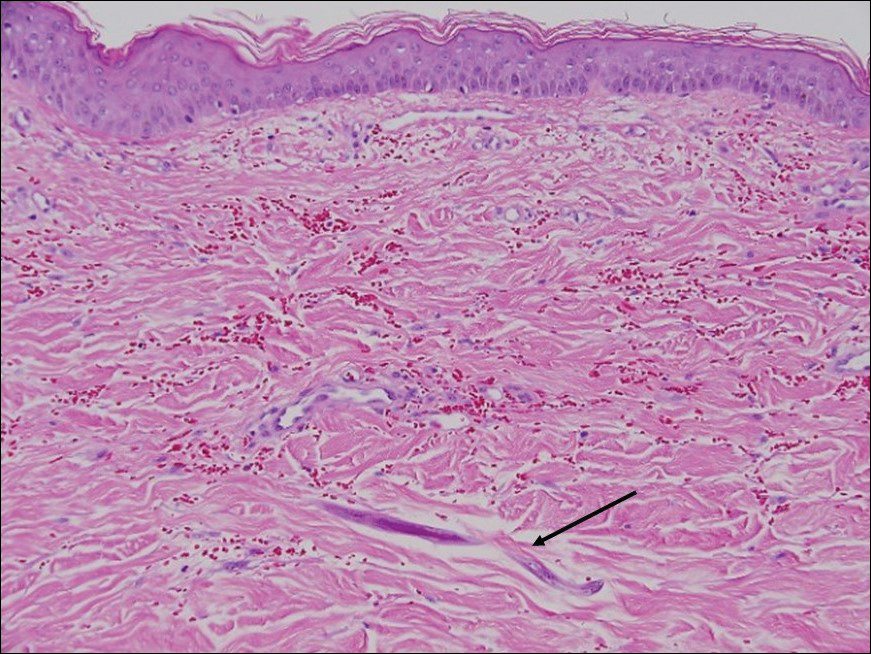

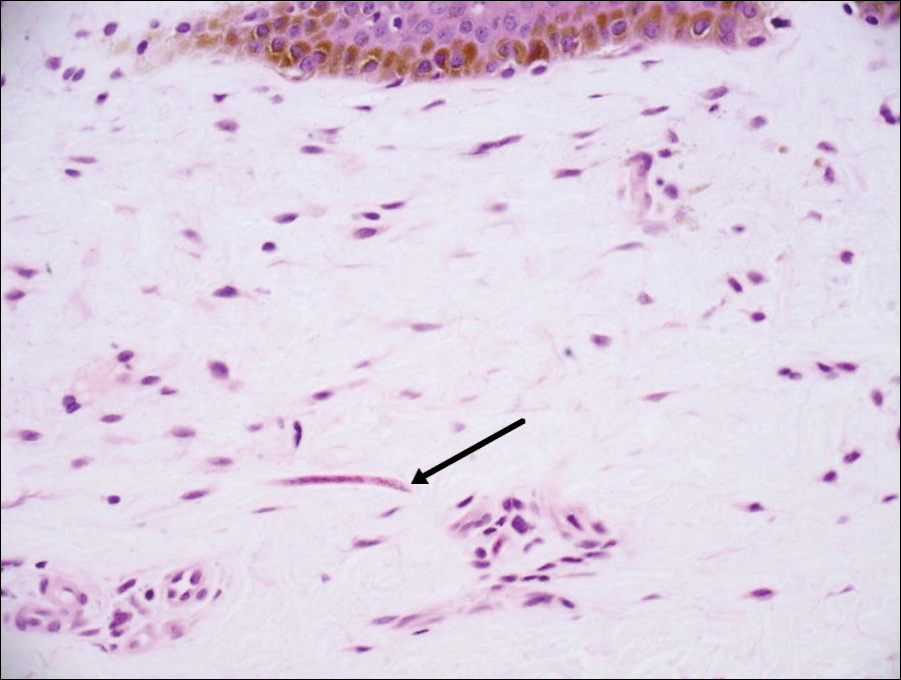

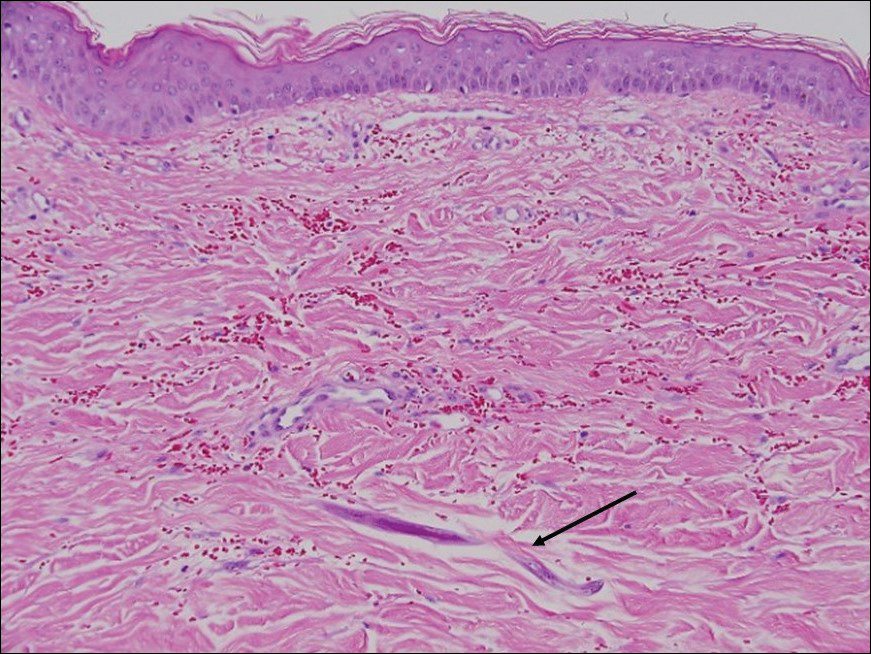

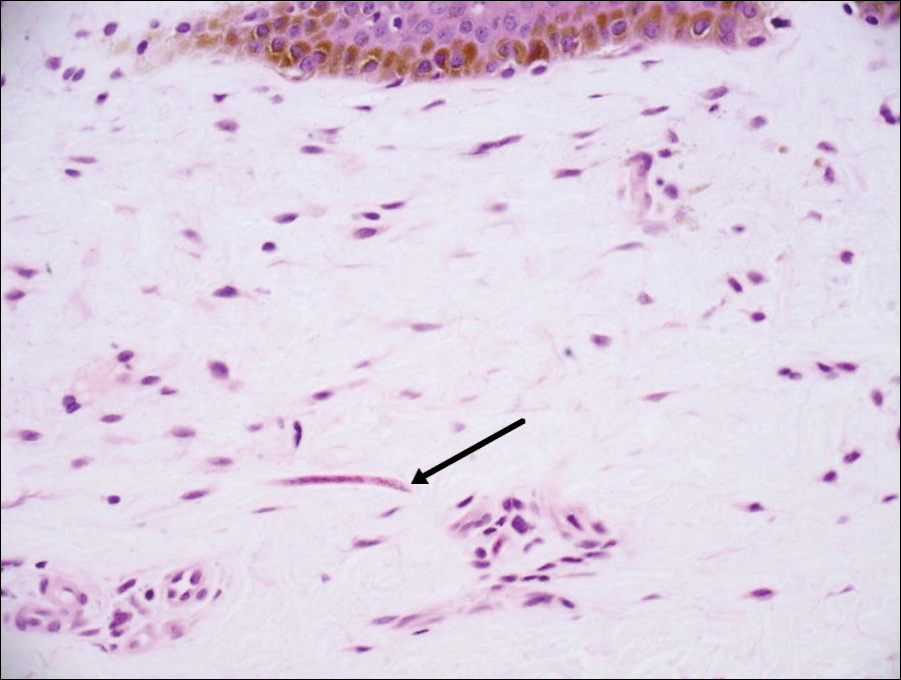

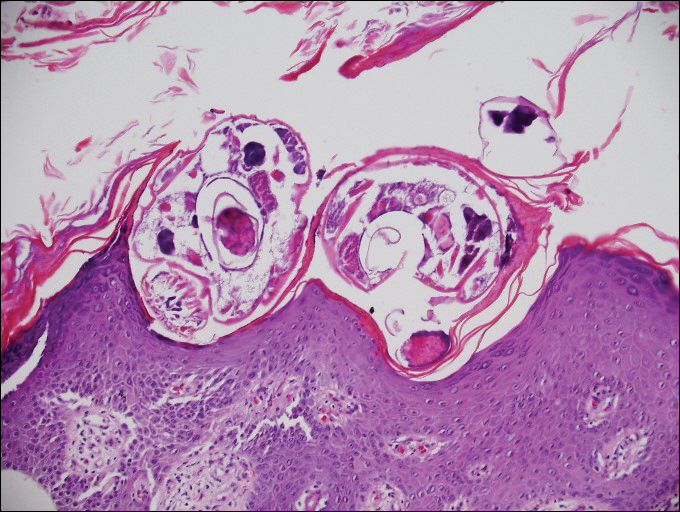

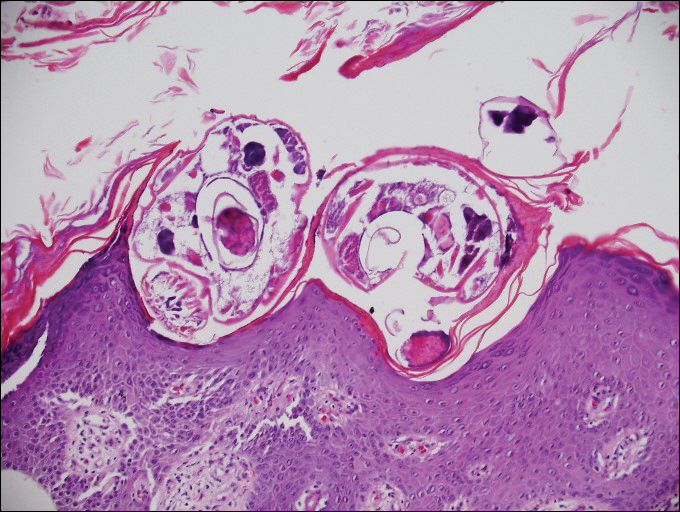

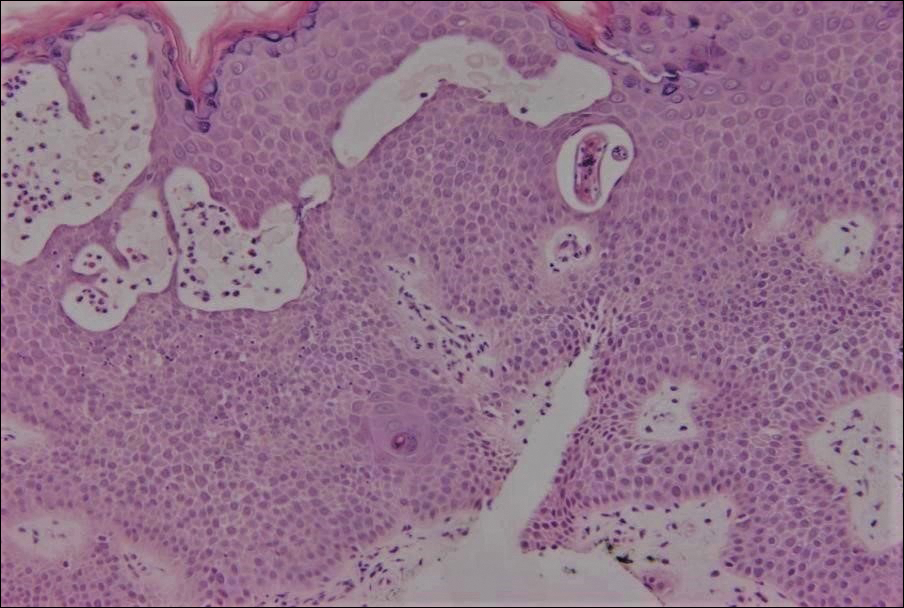

A punch biopsy from the left temple showed deposits of amorphous eosinophilic material at the tips of dermal papillae and in the papillary dermis with hemorrhage present (Figure 1). A diagnosis of amyloidosis was confirmed on the biopsy of the skin bulla. The low κ/λ light chain ratio and M-spike with notably elevated free λ light chains in both serum and urine were consistent with a λ light chain primary systemic amyloidosis. The patient was seen by hematology and oncology. A bone marrow biopsy demonstrated that 15% to 20% of the clonal-cell population was λ light chain restricted. Eosinophilic extracellular deposits found in the adjacent soft tissue and bone marrow space were confirmed as amyloid with apple green birefringence under polarized light on Congo red stain and metachromatic staining with crystal violet. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with λ light chain multiple myeloma and primary systemic amyloidosis.

Our patient was treated with a combination therapy of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone on 21-day cycles, with bortezomib on days 1, 4, 8, and 11. She had received 3 cycles of chemotherapy before developing diarrhea, hypotension, acute on chronic heart failure, and acute renal failure requiring hospitalization. She had several related complications due to amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis and subsequently died 16 days after her initial hospitalization from complications of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and septic shock.

Amyloidosis is the pathologic deposition of abnormal protein in the extracellular space of any tissue. Various soluble precursor proteins can make up amyloid, and these proteins polymerize into insoluble fibrils that damage the surrounding parenchyma. The clinical presentation of amyloidosis varies depending on the affected tissue as well as the constituent protein. The amyloidoses are divided into localized cutaneous, primary systemic, and secondary systemic variants. The initial distinction in amyloidosis is determining whether it is skin limited or systemic. Localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises 30% to 40% of all amyloidosis cases and is further divided into 3 main subtypes: macular, lichen, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis are composed of keratin derivatives and typically are induced by patients when rubbing or scratching the skin. Histologically, macular and lichen amyloidosis are restricted to the superficial papillary dermis.1 Nodular amyloidosis is composed of λ or κ light chain immunoglobulins, which are produced by cutaneous infiltrates of monoclonal plasma cells. Histologically, nodular amyloidosis is characterized by a diffuse dermal infiltrate of amorphous eosinophilic material.1 Primary systemic amyloidosis is associated with an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia, and unlike secondary keratinocyte-derived amyloid, it can involve internal organs. Similar to nodular amyloidosis, primary systemic amyloidosis is composed of AL proteins, and it is histologically similar to nodular amyloidosis.1

Primary systemic AL amyloidosis commonly affects individuals aged 50 to 60 years. Males and females are equally affected. Macroglossia and periorbital purpura are some of the pathognomonic presentations in AL amyloidosis. The major cause of death in these patients is cardiac and renal involvement. Renal involvement commonly presents as nephrotic syndrome, and cardiac involvement can present as a restrictive cardiomyopathy with dyspnea. Other symptoms include edema, hepatosplenomegaly, bleeding diathesis, and carpal tunnel syndrome.2 An evaluation for AL amyloidosis should include a complete review of systems and physical examination with studies such as complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, and electrocardiogram.

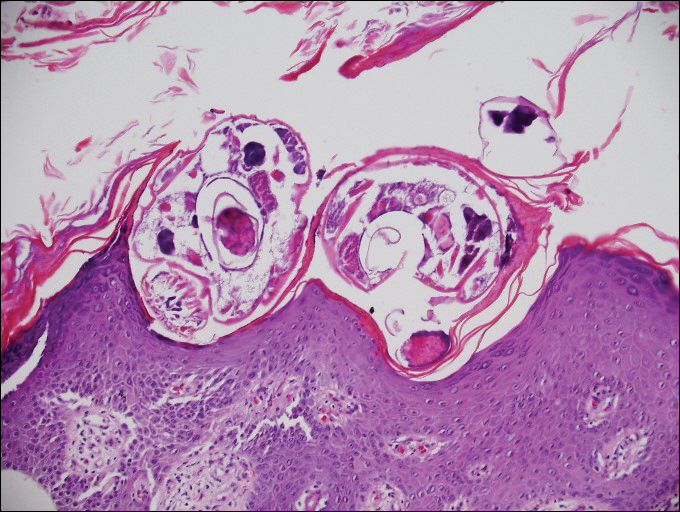

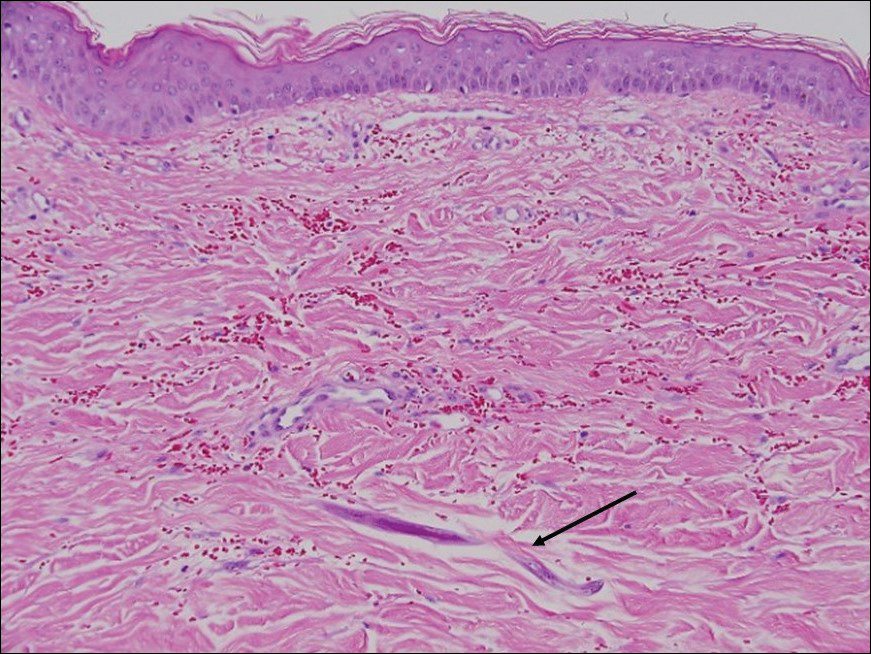

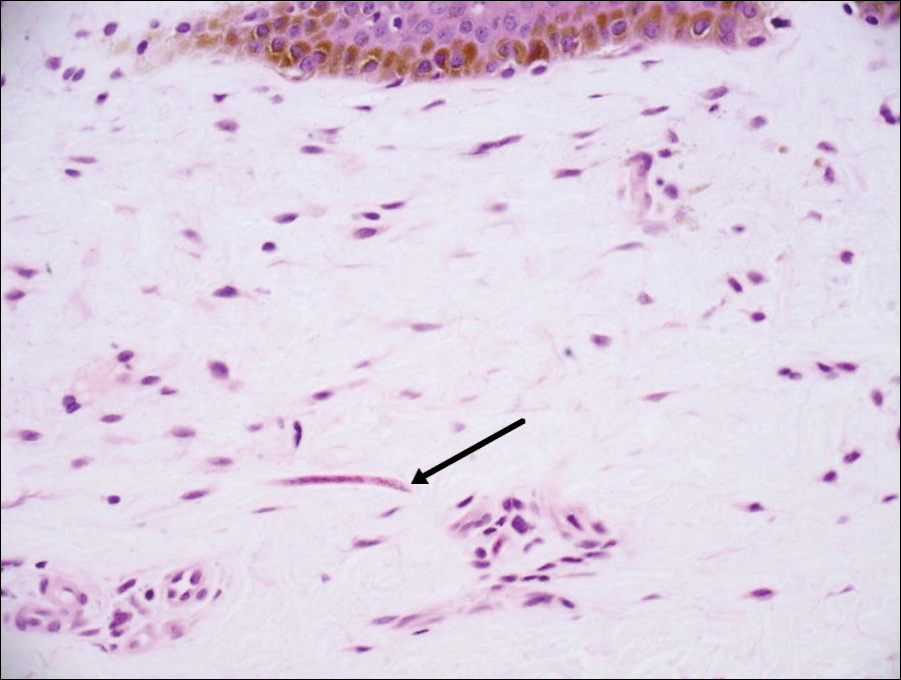

Cutaneous involvement in AL amyloidosis most commonly includes yellowish waxy papules, nodules, and plaques but also can include purpura and petechiae.2 Bullous amyloidosis, as seen in our patient, is a rare cutaneous presentation of AL amyloidosis that usually is negative for the Nikolsky sign (Figure 2). Bullae form due to weakness in amyloid-laden dermal connective tissue.3 Eighty-eight percent of cases of bullous amyloidosis have systemic involvement.1 Some cases have reported a familial linkage, suggesting there might be a genetic component to the disease.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bullous amyloidosis, bullous, amyloidosis, and amyloid revealed fewer than 35 cases of bullous amyloidosis in the English-language literature.5 Bullae can be located intradermally or subepidermally and commonly are hemorrhagic but also can be translucent, tender, and tense.

A study of electron microscopy in a patient with systemic bullous amyloidosis demonstrated amyloid and keratinocyte protrusions that perforated the dermis through the spaces in the lamina densa. The study concluded that the disintegration of the lamina densa and expansion of the intercellular spaces between keratinocytes were the causes of skin fragility as well as fluid exudation.5 Trauma or friction to the skin are local precipitating factors for blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.

Bullae can become apparent at any stage of AL amyloidosis, but they generally increase in size and number over time and are most common in intertriginous areas. Bullous amyloid lesions, especially those located in intertriginous areas, can have secondary impetiginization.6 In many cases, patients who present with bullous amyloidosis ultimately will be diagnosed with multiple myeloma or another plasma cell dyscrasia. In AL amyloidosis, only 10% to 15% of cases meet criteria for multiple myeloma, whereas 80% or more patients have a monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.7

The prognosis of cutaneous amyloidosis depends on the extent of organ involvement and response to treatment. Treatment is aimed at eliminating clonal plasma cell populations to decrease the production of light chains, thereby decreasing protein burden and amyloid progression. Historically, treatment options included cytotoxic chemotherapy such as oral melphalan and dexamethasone, followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplant. More recent treatment options include bortezomib, thalidomide, pomalidomide, and lenalidomide.8 Our patient received a regimen of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone that is used for patients with extensive multiple myeloma.

The differential diagnosis in our patient included bullous drug eruption, which should be considered if the bullae are reoccurring at the same location and in association with the administration of a culprit drug. Bullous pemphigoid is preceded by pruritus, and biopsy demonstrates subepidermal bullae with associated eosinophilic infiltrate. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can present with milia and a linear pattern along the basement membrane zone with direct immunofluorescence. Traumatic purpura usually present with the classic shape and hue of an ecchymosis, and the patient will have a history of trauma.

Cutaneous involvement of amyloidosis can be an early clue to the diagnosis of plasma cell dyscrasia. Early diagnosis and treatment can portend a better prognosis and prevent progression to renal or cardiac disease.

- Heaton J, Steinhoff N, Wanner B, et al. A review of primary cutaneous amyloidosis. J Am Osteopath Coll Dermatol. doi:10.1007/springerreference_42272

- Ventarola DJ, Schuster MW, Cohen JA, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. bullae and nodules on the legs of a 57-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1035-1037.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Suranagi VV, Siddramappa B, Bannur HB, et al. Bullous variant of familial biphasic lichen amyloidosis: a unique combination of three rare presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:105.

- Antúnez-Lay A, Jaque A, González S. Hemorrhagic bullous skin lesions. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:145-147.

- Reddy K, Hoda S, Penstein A, et al. Bullous amyloidosis complicated by cellulitis and sepsis: a case report. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:126-127.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Amyloidosis

A punch biopsy from the left temple showed deposits of amorphous eosinophilic material at the tips of dermal papillae and in the papillary dermis with hemorrhage present (Figure 1). A diagnosis of amyloidosis was confirmed on the biopsy of the skin bulla. The low κ/λ light chain ratio and M-spike with notably elevated free λ light chains in both serum and urine were consistent with a λ light chain primary systemic amyloidosis. The patient was seen by hematology and oncology. A bone marrow biopsy demonstrated that 15% to 20% of the clonal-cell population was λ light chain restricted. Eosinophilic extracellular deposits found in the adjacent soft tissue and bone marrow space were confirmed as amyloid with apple green birefringence under polarized light on Congo red stain and metachromatic staining with crystal violet. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with λ light chain multiple myeloma and primary systemic amyloidosis.

Our patient was treated with a combination therapy of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone on 21-day cycles, with bortezomib on days 1, 4, 8, and 11. She had received 3 cycles of chemotherapy before developing diarrhea, hypotension, acute on chronic heart failure, and acute renal failure requiring hospitalization. She had several related complications due to amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis and subsequently died 16 days after her initial hospitalization from complications of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and septic shock.

Amyloidosis is the pathologic deposition of abnormal protein in the extracellular space of any tissue. Various soluble precursor proteins can make up amyloid, and these proteins polymerize into insoluble fibrils that damage the surrounding parenchyma. The clinical presentation of amyloidosis varies depending on the affected tissue as well as the constituent protein. The amyloidoses are divided into localized cutaneous, primary systemic, and secondary systemic variants. The initial distinction in amyloidosis is determining whether it is skin limited or systemic. Localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises 30% to 40% of all amyloidosis cases and is further divided into 3 main subtypes: macular, lichen, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis are composed of keratin derivatives and typically are induced by patients when rubbing or scratching the skin. Histologically, macular and lichen amyloidosis are restricted to the superficial papillary dermis.1 Nodular amyloidosis is composed of λ or κ light chain immunoglobulins, which are produced by cutaneous infiltrates of monoclonal plasma cells. Histologically, nodular amyloidosis is characterized by a diffuse dermal infiltrate of amorphous eosinophilic material.1 Primary systemic amyloidosis is associated with an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia, and unlike secondary keratinocyte-derived amyloid, it can involve internal organs. Similar to nodular amyloidosis, primary systemic amyloidosis is composed of AL proteins, and it is histologically similar to nodular amyloidosis.1

Primary systemic AL amyloidosis commonly affects individuals aged 50 to 60 years. Males and females are equally affected. Macroglossia and periorbital purpura are some of the pathognomonic presentations in AL amyloidosis. The major cause of death in these patients is cardiac and renal involvement. Renal involvement commonly presents as nephrotic syndrome, and cardiac involvement can present as a restrictive cardiomyopathy with dyspnea. Other symptoms include edema, hepatosplenomegaly, bleeding diathesis, and carpal tunnel syndrome.2 An evaluation for AL amyloidosis should include a complete review of systems and physical examination with studies such as complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, and electrocardiogram.

Cutaneous involvement in AL amyloidosis most commonly includes yellowish waxy papules, nodules, and plaques but also can include purpura and petechiae.2 Bullous amyloidosis, as seen in our patient, is a rare cutaneous presentation of AL amyloidosis that usually is negative for the Nikolsky sign (Figure 2). Bullae form due to weakness in amyloid-laden dermal connective tissue.3 Eighty-eight percent of cases of bullous amyloidosis have systemic involvement.1 Some cases have reported a familial linkage, suggesting there might be a genetic component to the disease.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bullous amyloidosis, bullous, amyloidosis, and amyloid revealed fewer than 35 cases of bullous amyloidosis in the English-language literature.5 Bullae can be located intradermally or subepidermally and commonly are hemorrhagic but also can be translucent, tender, and tense.

A study of electron microscopy in a patient with systemic bullous amyloidosis demonstrated amyloid and keratinocyte protrusions that perforated the dermis through the spaces in the lamina densa. The study concluded that the disintegration of the lamina densa and expansion of the intercellular spaces between keratinocytes were the causes of skin fragility as well as fluid exudation.5 Trauma or friction to the skin are local precipitating factors for blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.

Bullae can become apparent at any stage of AL amyloidosis, but they generally increase in size and number over time and are most common in intertriginous areas. Bullous amyloid lesions, especially those located in intertriginous areas, can have secondary impetiginization.6 In many cases, patients who present with bullous amyloidosis ultimately will be diagnosed with multiple myeloma or another plasma cell dyscrasia. In AL amyloidosis, only 10% to 15% of cases meet criteria for multiple myeloma, whereas 80% or more patients have a monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.7

The prognosis of cutaneous amyloidosis depends on the extent of organ involvement and response to treatment. Treatment is aimed at eliminating clonal plasma cell populations to decrease the production of light chains, thereby decreasing protein burden and amyloid progression. Historically, treatment options included cytotoxic chemotherapy such as oral melphalan and dexamethasone, followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplant. More recent treatment options include bortezomib, thalidomide, pomalidomide, and lenalidomide.8 Our patient received a regimen of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone that is used for patients with extensive multiple myeloma.

The differential diagnosis in our patient included bullous drug eruption, which should be considered if the bullae are reoccurring at the same location and in association with the administration of a culprit drug. Bullous pemphigoid is preceded by pruritus, and biopsy demonstrates subepidermal bullae with associated eosinophilic infiltrate. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can present with milia and a linear pattern along the basement membrane zone with direct immunofluorescence. Traumatic purpura usually present with the classic shape and hue of an ecchymosis, and the patient will have a history of trauma.

Cutaneous involvement of amyloidosis can be an early clue to the diagnosis of plasma cell dyscrasia. Early diagnosis and treatment can portend a better prognosis and prevent progression to renal or cardiac disease.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Amyloidosis

A punch biopsy from the left temple showed deposits of amorphous eosinophilic material at the tips of dermal papillae and in the papillary dermis with hemorrhage present (Figure 1). A diagnosis of amyloidosis was confirmed on the biopsy of the skin bulla. The low κ/λ light chain ratio and M-spike with notably elevated free λ light chains in both serum and urine were consistent with a λ light chain primary systemic amyloidosis. The patient was seen by hematology and oncology. A bone marrow biopsy demonstrated that 15% to 20% of the clonal-cell population was λ light chain restricted. Eosinophilic extracellular deposits found in the adjacent soft tissue and bone marrow space were confirmed as amyloid with apple green birefringence under polarized light on Congo red stain and metachromatic staining with crystal violet. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with λ light chain multiple myeloma and primary systemic amyloidosis.

Our patient was treated with a combination therapy of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone on 21-day cycles, with bortezomib on days 1, 4, 8, and 11. She had received 3 cycles of chemotherapy before developing diarrhea, hypotension, acute on chronic heart failure, and acute renal failure requiring hospitalization. She had several related complications due to amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis and subsequently died 16 days after her initial hospitalization from complications of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and septic shock.

Amyloidosis is the pathologic deposition of abnormal protein in the extracellular space of any tissue. Various soluble precursor proteins can make up amyloid, and these proteins polymerize into insoluble fibrils that damage the surrounding parenchyma. The clinical presentation of amyloidosis varies depending on the affected tissue as well as the constituent protein. The amyloidoses are divided into localized cutaneous, primary systemic, and secondary systemic variants. The initial distinction in amyloidosis is determining whether it is skin limited or systemic. Localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises 30% to 40% of all amyloidosis cases and is further divided into 3 main subtypes: macular, lichen, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis are composed of keratin derivatives and typically are induced by patients when rubbing or scratching the skin. Histologically, macular and lichen amyloidosis are restricted to the superficial papillary dermis.1 Nodular amyloidosis is composed of λ or κ light chain immunoglobulins, which are produced by cutaneous infiltrates of monoclonal plasma cells. Histologically, nodular amyloidosis is characterized by a diffuse dermal infiltrate of amorphous eosinophilic material.1 Primary systemic amyloidosis is associated with an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia, and unlike secondary keratinocyte-derived amyloid, it can involve internal organs. Similar to nodular amyloidosis, primary systemic amyloidosis is composed of AL proteins, and it is histologically similar to nodular amyloidosis.1

Primary systemic AL amyloidosis commonly affects individuals aged 50 to 60 years. Males and females are equally affected. Macroglossia and periorbital purpura are some of the pathognomonic presentations in AL amyloidosis. The major cause of death in these patients is cardiac and renal involvement. Renal involvement commonly presents as nephrotic syndrome, and cardiac involvement can present as a restrictive cardiomyopathy with dyspnea. Other symptoms include edema, hepatosplenomegaly, bleeding diathesis, and carpal tunnel syndrome.2 An evaluation for AL amyloidosis should include a complete review of systems and physical examination with studies such as complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, and electrocardiogram.

Cutaneous involvement in AL amyloidosis most commonly includes yellowish waxy papules, nodules, and plaques but also can include purpura and petechiae.2 Bullous amyloidosis, as seen in our patient, is a rare cutaneous presentation of AL amyloidosis that usually is negative for the Nikolsky sign (Figure 2). Bullae form due to weakness in amyloid-laden dermal connective tissue.3 Eighty-eight percent of cases of bullous amyloidosis have systemic involvement.1 Some cases have reported a familial linkage, suggesting there might be a genetic component to the disease.4 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bullous amyloidosis, bullous, amyloidosis, and amyloid revealed fewer than 35 cases of bullous amyloidosis in the English-language literature.5 Bullae can be located intradermally or subepidermally and commonly are hemorrhagic but also can be translucent, tender, and tense.

A study of electron microscopy in a patient with systemic bullous amyloidosis demonstrated amyloid and keratinocyte protrusions that perforated the dermis through the spaces in the lamina densa. The study concluded that the disintegration of the lamina densa and expansion of the intercellular spaces between keratinocytes were the causes of skin fragility as well as fluid exudation.5 Trauma or friction to the skin are local precipitating factors for blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.

Bullae can become apparent at any stage of AL amyloidosis, but they generally increase in size and number over time and are most common in intertriginous areas. Bullous amyloid lesions, especially those located in intertriginous areas, can have secondary impetiginization.6 In many cases, patients who present with bullous amyloidosis ultimately will be diagnosed with multiple myeloma or another plasma cell dyscrasia. In AL amyloidosis, only 10% to 15% of cases meet criteria for multiple myeloma, whereas 80% or more patients have a monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.7

The prognosis of cutaneous amyloidosis depends on the extent of organ involvement and response to treatment. Treatment is aimed at eliminating clonal plasma cell populations to decrease the production of light chains, thereby decreasing protein burden and amyloid progression. Historically, treatment options included cytotoxic chemotherapy such as oral melphalan and dexamethasone, followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplant. More recent treatment options include bortezomib, thalidomide, pomalidomide, and lenalidomide.8 Our patient received a regimen of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone that is used for patients with extensive multiple myeloma.

The differential diagnosis in our patient included bullous drug eruption, which should be considered if the bullae are reoccurring at the same location and in association with the administration of a culprit drug. Bullous pemphigoid is preceded by pruritus, and biopsy demonstrates subepidermal bullae with associated eosinophilic infiltrate. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can present with milia and a linear pattern along the basement membrane zone with direct immunofluorescence. Traumatic purpura usually present with the classic shape and hue of an ecchymosis, and the patient will have a history of trauma.

Cutaneous involvement of amyloidosis can be an early clue to the diagnosis of plasma cell dyscrasia. Early diagnosis and treatment can portend a better prognosis and prevent progression to renal or cardiac disease.

- Heaton J, Steinhoff N, Wanner B, et al. A review of primary cutaneous amyloidosis. J Am Osteopath Coll Dermatol. doi:10.1007/springerreference_42272

- Ventarola DJ, Schuster MW, Cohen JA, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. bullae and nodules on the legs of a 57-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1035-1037.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Suranagi VV, Siddramappa B, Bannur HB, et al. Bullous variant of familial biphasic lichen amyloidosis: a unique combination of three rare presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:105.

- Antúnez-Lay A, Jaque A, González S. Hemorrhagic bullous skin lesions. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:145-147.

- Reddy K, Hoda S, Penstein A, et al. Bullous amyloidosis complicated by cellulitis and sepsis: a case report. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:126-127.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

- Heaton J, Steinhoff N, Wanner B, et al. A review of primary cutaneous amyloidosis. J Am Osteopath Coll Dermatol. doi:10.1007/springerreference_42272

- Ventarola DJ, Schuster MW, Cohen JA, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. bullae and nodules on the legs of a 57-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1035-1037.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Suranagi VV, Siddramappa B, Bannur HB, et al. Bullous variant of familial biphasic lichen amyloidosis: a unique combination of three rare presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:105.

- Antúnez-Lay A, Jaque A, González S. Hemorrhagic bullous skin lesions. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:145-147.

- Reddy K, Hoda S, Penstein A, et al. Bullous amyloidosis complicated by cellulitis and sepsis: a case report. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:126-127.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

A 67-year-old woman with a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, unspecified leukocytosis, and anemia presented to the dermatology clinic with asymptomatic hemorrhagic bullae on the face, chest, and tongue, as well as a large, tender, tense, hemorrhagic bulla on the groin of 3 to 4 months’ duration. A review of systems was negative for fever, chills, night sweats, malaise, shortness of breath, and dyspnea on exertion. A complete blood cell count showed mild leukocytosis, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Her creatinine level was slightly elevated. Chest computed tomography showed early pulmonary fibrosis and coronary artery calcification. An echocardiogram showed diastolic dysfunction with moderate left ventricle thickening. A serum and urine electrophoresis demonstrated elevated free λ light chains with an M-spike. A punch biopsy was performed.

A sheep in wolf’s clothing?

A 25-year-old college student with no medical history sought care at our hospital for a nonproductive cough, subjective fevers, myalgia, and malaise that he’d developed 10 days earlier. The day before his visit, he’d also developed scratchy red eyes and a sore throat. He said he’d taken an over-the-counter cough suppressant to help with the cough, but his eyes and lips developed further redness and irritation.

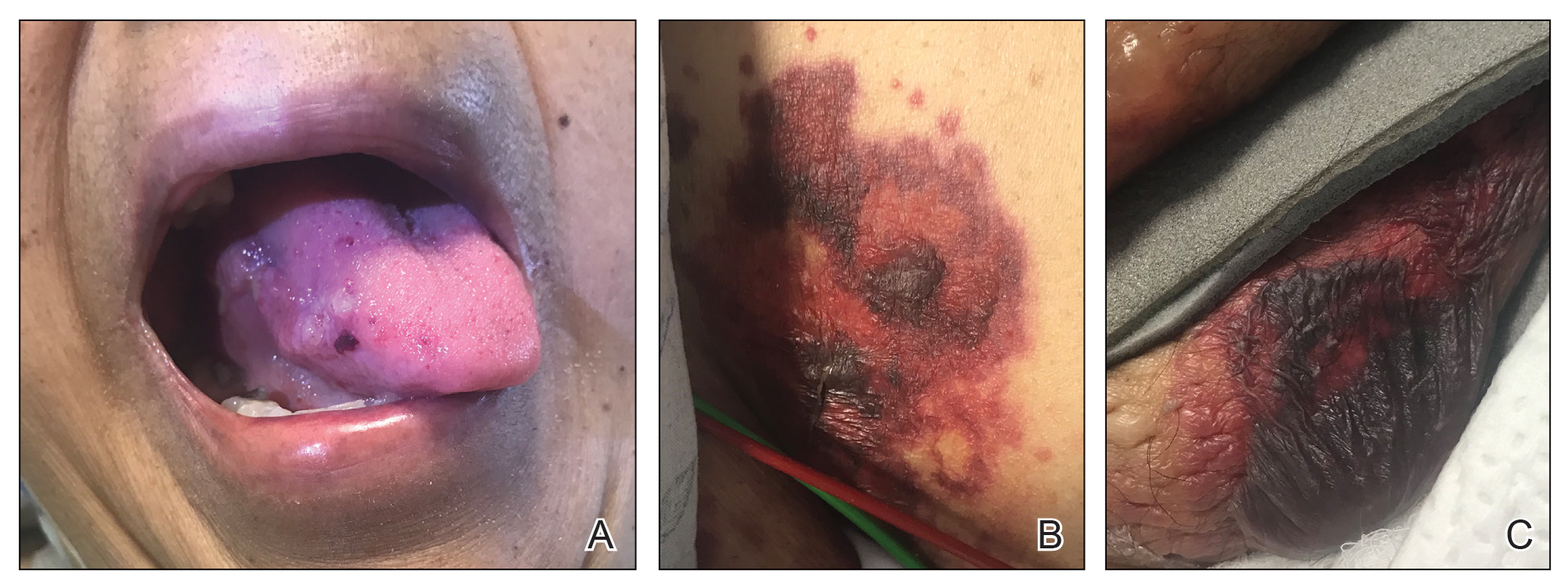

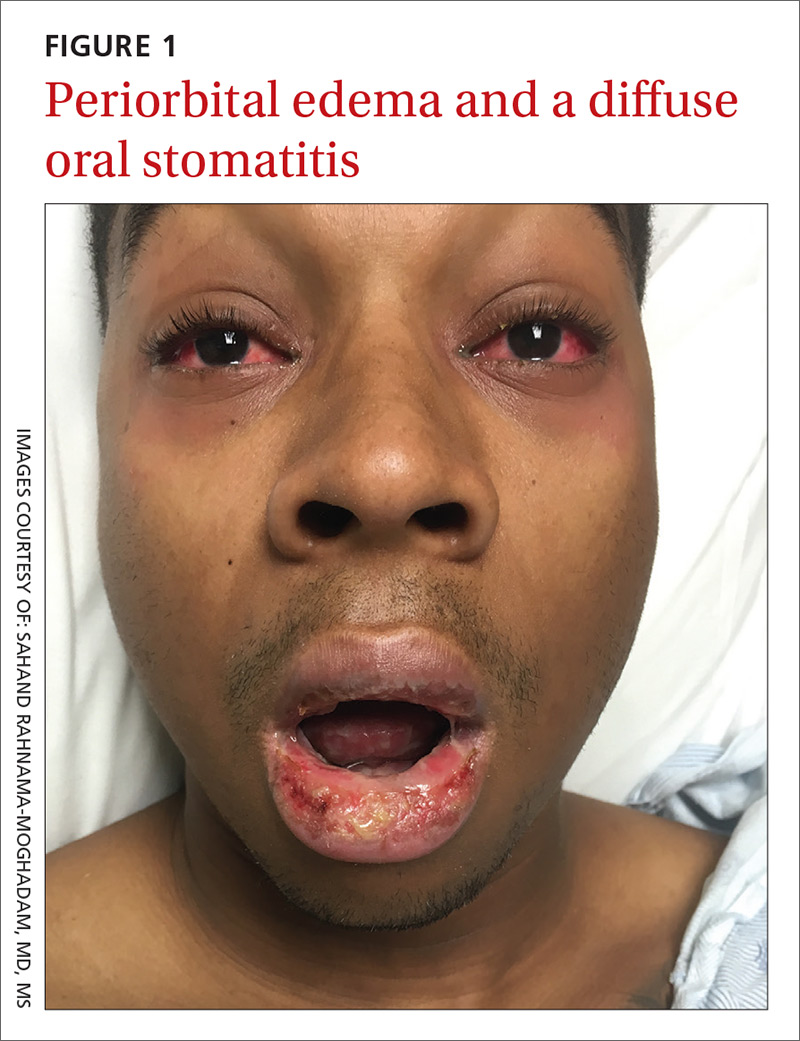

On examination, the patient demonstrated conjunctival suffusion, periorbital edema, diffuse oral stomatitis with pseudomembranous crusting, and nasal crusting (FIGURE 1). His vital signs were within normal limits, and he had no epithelial skin eruptions or erosions in any other mucosal regions.

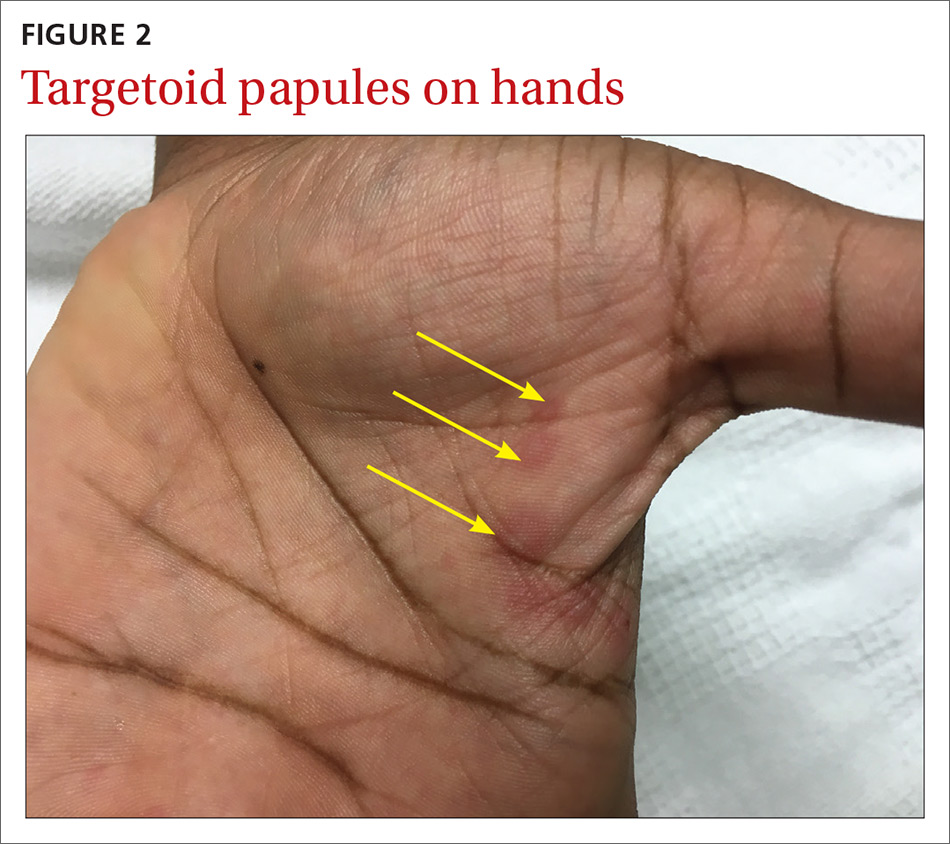

The patient was not currently sexually active and had one lifetime female sexual partner. He had no history of sexually transmitted infections or cold sores, and was not taking any medications, herbs, or supplements. During the initial 24 hours of admission, he developed 4 to 5 red targetoid papules on each hand (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: M pneumoniae-associated mucositis

The patient was admitted for observation to rule out Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN). We felt that the degree of mucositis (extensive) compared to the number of targetoid papules on the hands (minimal) suggested a diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis (MPAM), a subtype of erythema multiforme (EM) major. The patient’s prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise also supported a “walking pneumonia” diagnosis, such as MPAM.

Further testing. The patient had a normal chest x-ray and a negative respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR), but IgM serologies for Mycoplasma were elevated. Although the patient developed targetoid lesions on his hands during his first 24 hours in the hospital, he felt his constitutional symptoms had improved.

Exposure to Mycoplasma leads to an immune response

MPAM (also known as Fuchs’ syndrome and mycoplasma-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations) appears at some point during infection with M pneumoniae and causes severe ocular, oral, and sometimes genital symptoms with minimal skin manifestations.

MPAM is primarily seen in young males. In one systemic review of 202 cases, the average age of the patients was 11.9 years and 66% were male.1 Exposure to M pneumoniae is theorized to result in the production of autoantibodies to mycoplasma p1-adhesion molecules and to molecular mimicry of keratinocyte antigens located in the mucosa.1-3

Mycoplasma organisms have not been isolated from the cutaneous lesions of patients with MPAM; they have only been isolated from the respiratory tract, supporting the theory that MPAM is the body’s immune response to Mycoplasma, rather than a direct pathologic effect.4 This pathogenesis is distinct from that of SJS/TEN, which is thought to involve CD8+ T-cell-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis (programed cell death). In addition, SJS/TEN is almost always drug induced.

First up in the differential: Rule out SJS/TEN

When evaluating a patient like ours with a blistering eruption, the most important diagnosis to exclude is SJS/TEN. This condition is usually triggered by a medication, which was absent in this case. SJS/TEN begins with a host of constitutional symptoms and an erythematous blistering eruption, which may be preceded by atypical targetoid (2-zoned) flat papules along with erosions on 2 or more mucosal surfaces.

Patients with SJS/TEN are usually critically ill and may have a guarded prognosis. Patients with MPAM have a more favorable prognosis and are unlikely to be critically ill—as was the case with our patient.

EM major is often associated with Mycoplasma infections. Patients with EM major may have fever and arthralgias, as well as extensive mucous membrane involvement including that of the lips/mouth, eyes, and genitals.

Experts agree that EM is separate from the SJS/TEN continuum, and that patients with EM major, including those with MPAM, are not at risk of developing SJS/TEN.5 EM is characterized by the presence of the more characteristic ‘target’ or ‘iris’ 3-zoned lesion—a central dusky purpura, surrounded by an elevated edematous pale ring, rimmed by a red macular outer ring. EM major is defined as EM along with involvement of one or more mucosal regions.

In this case, the patient had acral target lesions and oral and ocular mucosal involvement characteristic of EM major, without widespread skin erosions or sloughing commonly seen with SJS/TEN.

Kawasaki’s disease occurs in young children and presents with conjunctivitis and oral changes. However, patients with Kawasaki’s disease generally have a fever for >5 days, a strawberry tongue (not a part of the morphology of EM major or MPAM), and palmoplantar erythema and desquamation that are not common with EM major or MPAM.1

Pemphigus vulgaris is uncommon in children and young adults. The disease does not present with diffuse mucositis nor diffuse blistering of the skin, but rather with discrete shallow erosions on the mucosa and the trunk along with flaccid bullae and erosions on the skin.

The morphologies of a fixed drug eruption (round purpuric patch) and toxic shock syndrome (diffuse macular erythema and widespread skin sloughing) are inconsistent with this patient’s diffuse mucositis, conjunctivitis, and targetoid lesions.

Confirm exposure to M pneumoniae

Testing with the purpose of ruling in MPAM is directed toward proving that the patient has been exposed to M pneumoniae. (Of note: M pneumoniae cannot be detected via routine commercial blood cultures.)

Serologic testing for elevated IgM antibodies to Mycoplasma is the most specific method. Various studies have found it to be positive in 100% of cases, but detection may be delayed for a couple of weeks while the body develops the requisite antibodies.4

Respiratory PCR for Mycoplasma is rapid and usually appropriately positive, but may be negative in cases where the patient has spontaneously cleared the infection or has been exposed to antibiotics before development of the eruption.4 An infiltrate on chest imaging is supportive of the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy will demonstrate either mucositis and necrosis of keratinocytes or EM-like necrosis, but does not suggest an etiology.

Strikingly different paths of care

Distinguishing between SJS/TEN and EM major (including MPAM) is crucial to guiding management. Patients with SJS/TEN need critical care, particularly of their eyes and genitourinary and respiratory systems. Specialist consultation is often required.

For EM major, patients require supportive care along with ongoing assurances that the eruption has a benign prognosis. Hospital admission is not mandatory as long as adequate supportive care and symptom control can be provided on an outpatient basis. Early consultation with Ophthalmology, Oral Medicine, and Urology may also be key.

Keep in mind that patients may have severe stomatitis and pain that alter their ability to eat and perform normal activities. Thus, managing pain and ensuring adequate nutrition are crucial for successful support. While antibiotics treat active Mycoplasma infection, there is no clear evidence that antibiotics alter the course of the eruption, which is also consistent with the hypothesized pathogenesis.3,4

While there is no clear statistical evidence that systemic immune suppression alters the disease course, a large proportion (31%) of patients in a recent systematic review of MPAM were treated with corticosteroids, and a smaller, but noteworthy, percentage (9%) were treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG).4 There are reports of severe stomatitis that didn’t improve with supportive care, but that showed dramatic improvement with IVIG treatment.6,7

Our patient had difficulty controlling secretions and managing the painful mucositis of his mouth; he was initially unable to tolerate solid foods. Topical lidocaine solution for his mucositis caused burning and more discomfort, but acetaminophen-hydrocodone 300 mg-5 mg every 6 hours did relieve his pain. Wound care with a bland emollient and the application of non-stick dressings to his lips at night also helped to relieve some of the pain.

Because the patient’s oropharyngeal swelling made it hard for him to swallow, he received oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d, which provided him with relief within 24 hours. The acute inflammation and eruption also subsided within 48 hours and the patient was discharged after 5 days of being hospitalized. He continued to recover as an outpatient, seeing his primary care physician within 2 weeks for final nutrition and wound care support. Two weeks after that, he had a dermatology appointment, and all of his lesions had re-epithelialized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, MS, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7323 Snowden Road, Apt. 1205, San Antonio, TX 78240; sahandazeez@gmail.com.

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.

2. Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:e238-e240.

3. Dinulos JG. What’s new with common, uncommon and rare rashes in childhood. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27:261-266.

4. Meyer Sauteur PM, Goetschel P, Lautenschlager S. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and mucositis–part of the Stevens-Johnson syndrome spectrum. J Dtsh Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:740-746.

5. Figueira-Coelho J, Lourenço S, Pires AC, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:399-403.

6. Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:e238-e240.

7. Zipitis CS, Thalange N. Intravenous immunoglobulins for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome with minimal skin manifestations. Eur J Pediatr.2007;166:585-588.

A 25-year-old college student with no medical history sought care at our hospital for a nonproductive cough, subjective fevers, myalgia, and malaise that he’d developed 10 days earlier. The day before his visit, he’d also developed scratchy red eyes and a sore throat. He said he’d taken an over-the-counter cough suppressant to help with the cough, but his eyes and lips developed further redness and irritation.

On examination, the patient demonstrated conjunctival suffusion, periorbital edema, diffuse oral stomatitis with pseudomembranous crusting, and nasal crusting (FIGURE 1). His vital signs were within normal limits, and he had no epithelial skin eruptions or erosions in any other mucosal regions.

The patient was not currently sexually active and had one lifetime female sexual partner. He had no history of sexually transmitted infections or cold sores, and was not taking any medications, herbs, or supplements. During the initial 24 hours of admission, he developed 4 to 5 red targetoid papules on each hand (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: M pneumoniae-associated mucositis

The patient was admitted for observation to rule out Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN). We felt that the degree of mucositis (extensive) compared to the number of targetoid papules on the hands (minimal) suggested a diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis (MPAM), a subtype of erythema multiforme (EM) major. The patient’s prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise also supported a “walking pneumonia” diagnosis, such as MPAM.

Further testing. The patient had a normal chest x-ray and a negative respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR), but IgM serologies for Mycoplasma were elevated. Although the patient developed targetoid lesions on his hands during his first 24 hours in the hospital, he felt his constitutional symptoms had improved.

Exposure to Mycoplasma leads to an immune response

MPAM (also known as Fuchs’ syndrome and mycoplasma-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations) appears at some point during infection with M pneumoniae and causes severe ocular, oral, and sometimes genital symptoms with minimal skin manifestations.

MPAM is primarily seen in young males. In one systemic review of 202 cases, the average age of the patients was 11.9 years and 66% were male.1 Exposure to M pneumoniae is theorized to result in the production of autoantibodies to mycoplasma p1-adhesion molecules and to molecular mimicry of keratinocyte antigens located in the mucosa.1-3

Mycoplasma organisms have not been isolated from the cutaneous lesions of patients with MPAM; they have only been isolated from the respiratory tract, supporting the theory that MPAM is the body’s immune response to Mycoplasma, rather than a direct pathologic effect.4 This pathogenesis is distinct from that of SJS/TEN, which is thought to involve CD8+ T-cell-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis (programed cell death). In addition, SJS/TEN is almost always drug induced.

First up in the differential: Rule out SJS/TEN

When evaluating a patient like ours with a blistering eruption, the most important diagnosis to exclude is SJS/TEN. This condition is usually triggered by a medication, which was absent in this case. SJS/TEN begins with a host of constitutional symptoms and an erythematous blistering eruption, which may be preceded by atypical targetoid (2-zoned) flat papules along with erosions on 2 or more mucosal surfaces.

Patients with SJS/TEN are usually critically ill and may have a guarded prognosis. Patients with MPAM have a more favorable prognosis and are unlikely to be critically ill—as was the case with our patient.

EM major is often associated with Mycoplasma infections. Patients with EM major may have fever and arthralgias, as well as extensive mucous membrane involvement including that of the lips/mouth, eyes, and genitals.

Experts agree that EM is separate from the SJS/TEN continuum, and that patients with EM major, including those with MPAM, are not at risk of developing SJS/TEN.5 EM is characterized by the presence of the more characteristic ‘target’ or ‘iris’ 3-zoned lesion—a central dusky purpura, surrounded by an elevated edematous pale ring, rimmed by a red macular outer ring. EM major is defined as EM along with involvement of one or more mucosal regions.

In this case, the patient had acral target lesions and oral and ocular mucosal involvement characteristic of EM major, without widespread skin erosions or sloughing commonly seen with SJS/TEN.

Kawasaki’s disease occurs in young children and presents with conjunctivitis and oral changes. However, patients with Kawasaki’s disease generally have a fever for >5 days, a strawberry tongue (not a part of the morphology of EM major or MPAM), and palmoplantar erythema and desquamation that are not common with EM major or MPAM.1

Pemphigus vulgaris is uncommon in children and young adults. The disease does not present with diffuse mucositis nor diffuse blistering of the skin, but rather with discrete shallow erosions on the mucosa and the trunk along with flaccid bullae and erosions on the skin.

The morphologies of a fixed drug eruption (round purpuric patch) and toxic shock syndrome (diffuse macular erythema and widespread skin sloughing) are inconsistent with this patient’s diffuse mucositis, conjunctivitis, and targetoid lesions.

Confirm exposure to M pneumoniae

Testing with the purpose of ruling in MPAM is directed toward proving that the patient has been exposed to M pneumoniae. (Of note: M pneumoniae cannot be detected via routine commercial blood cultures.)

Serologic testing for elevated IgM antibodies to Mycoplasma is the most specific method. Various studies have found it to be positive in 100% of cases, but detection may be delayed for a couple of weeks while the body develops the requisite antibodies.4

Respiratory PCR for Mycoplasma is rapid and usually appropriately positive, but may be negative in cases where the patient has spontaneously cleared the infection or has been exposed to antibiotics before development of the eruption.4 An infiltrate on chest imaging is supportive of the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy will demonstrate either mucositis and necrosis of keratinocytes or EM-like necrosis, but does not suggest an etiology.

Strikingly different paths of care

Distinguishing between SJS/TEN and EM major (including MPAM) is crucial to guiding management. Patients with SJS/TEN need critical care, particularly of their eyes and genitourinary and respiratory systems. Specialist consultation is often required.

For EM major, patients require supportive care along with ongoing assurances that the eruption has a benign prognosis. Hospital admission is not mandatory as long as adequate supportive care and symptom control can be provided on an outpatient basis. Early consultation with Ophthalmology, Oral Medicine, and Urology may also be key.

Keep in mind that patients may have severe stomatitis and pain that alter their ability to eat and perform normal activities. Thus, managing pain and ensuring adequate nutrition are crucial for successful support. While antibiotics treat active Mycoplasma infection, there is no clear evidence that antibiotics alter the course of the eruption, which is also consistent with the hypothesized pathogenesis.3,4

While there is no clear statistical evidence that systemic immune suppression alters the disease course, a large proportion (31%) of patients in a recent systematic review of MPAM were treated with corticosteroids, and a smaller, but noteworthy, percentage (9%) were treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG).4 There are reports of severe stomatitis that didn’t improve with supportive care, but that showed dramatic improvement with IVIG treatment.6,7

Our patient had difficulty controlling secretions and managing the painful mucositis of his mouth; he was initially unable to tolerate solid foods. Topical lidocaine solution for his mucositis caused burning and more discomfort, but acetaminophen-hydrocodone 300 mg-5 mg every 6 hours did relieve his pain. Wound care with a bland emollient and the application of non-stick dressings to his lips at night also helped to relieve some of the pain.

Because the patient’s oropharyngeal swelling made it hard for him to swallow, he received oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d, which provided him with relief within 24 hours. The acute inflammation and eruption also subsided within 48 hours and the patient was discharged after 5 days of being hospitalized. He continued to recover as an outpatient, seeing his primary care physician within 2 weeks for final nutrition and wound care support. Two weeks after that, he had a dermatology appointment, and all of his lesions had re-epithelialized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, MS, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7323 Snowden Road, Apt. 1205, San Antonio, TX 78240; sahandazeez@gmail.com.

A 25-year-old college student with no medical history sought care at our hospital for a nonproductive cough, subjective fevers, myalgia, and malaise that he’d developed 10 days earlier. The day before his visit, he’d also developed scratchy red eyes and a sore throat. He said he’d taken an over-the-counter cough suppressant to help with the cough, but his eyes and lips developed further redness and irritation.

On examination, the patient demonstrated conjunctival suffusion, periorbital edema, diffuse oral stomatitis with pseudomembranous crusting, and nasal crusting (FIGURE 1). His vital signs were within normal limits, and he had no epithelial skin eruptions or erosions in any other mucosal regions.

The patient was not currently sexually active and had one lifetime female sexual partner. He had no history of sexually transmitted infections or cold sores, and was not taking any medications, herbs, or supplements. During the initial 24 hours of admission, he developed 4 to 5 red targetoid papules on each hand (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: M pneumoniae-associated mucositis

The patient was admitted for observation to rule out Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN). We felt that the degree of mucositis (extensive) compared to the number of targetoid papules on the hands (minimal) suggested a diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis (MPAM), a subtype of erythema multiforme (EM) major. The patient’s prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise also supported a “walking pneumonia” diagnosis, such as MPAM.

Further testing. The patient had a normal chest x-ray and a negative respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR), but IgM serologies for Mycoplasma were elevated. Although the patient developed targetoid lesions on his hands during his first 24 hours in the hospital, he felt his constitutional symptoms had improved.

Exposure to Mycoplasma leads to an immune response

MPAM (also known as Fuchs’ syndrome and mycoplasma-associated mucositis with minimal skin manifestations) appears at some point during infection with M pneumoniae and causes severe ocular, oral, and sometimes genital symptoms with minimal skin manifestations.

MPAM is primarily seen in young males. In one systemic review of 202 cases, the average age of the patients was 11.9 years and 66% were male.1 Exposure to M pneumoniae is theorized to result in the production of autoantibodies to mycoplasma p1-adhesion molecules and to molecular mimicry of keratinocyte antigens located in the mucosa.1-3

Mycoplasma organisms have not been isolated from the cutaneous lesions of patients with MPAM; they have only been isolated from the respiratory tract, supporting the theory that MPAM is the body’s immune response to Mycoplasma, rather than a direct pathologic effect.4 This pathogenesis is distinct from that of SJS/TEN, which is thought to involve CD8+ T-cell-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis (programed cell death). In addition, SJS/TEN is almost always drug induced.

First up in the differential: Rule out SJS/TEN

When evaluating a patient like ours with a blistering eruption, the most important diagnosis to exclude is SJS/TEN. This condition is usually triggered by a medication, which was absent in this case. SJS/TEN begins with a host of constitutional symptoms and an erythematous blistering eruption, which may be preceded by atypical targetoid (2-zoned) flat papules along with erosions on 2 or more mucosal surfaces.

Patients with SJS/TEN are usually critically ill and may have a guarded prognosis. Patients with MPAM have a more favorable prognosis and are unlikely to be critically ill—as was the case with our patient.

EM major is often associated with Mycoplasma infections. Patients with EM major may have fever and arthralgias, as well as extensive mucous membrane involvement including that of the lips/mouth, eyes, and genitals.

Experts agree that EM is separate from the SJS/TEN continuum, and that patients with EM major, including those with MPAM, are not at risk of developing SJS/TEN.5 EM is characterized by the presence of the more characteristic ‘target’ or ‘iris’ 3-zoned lesion—a central dusky purpura, surrounded by an elevated edematous pale ring, rimmed by a red macular outer ring. EM major is defined as EM along with involvement of one or more mucosal regions.

In this case, the patient had acral target lesions and oral and ocular mucosal involvement characteristic of EM major, without widespread skin erosions or sloughing commonly seen with SJS/TEN.