User login

Prices for Common Procedures Not Readily Available

Clinical question: Are patients able to select health-care providers based on price of service?

Background: With health-care costs rising, patients are encouraged to take a more active role in cost containment. Many initiatives call for greater pricing transparency in the health-care system. This study evaluated price availability for a common surgical procedure.

Study design: Telephone inquiries with standardized interview script.

Setting: Twenty top-ranked orthopedic hospitals and 102 non-top-ranked U.S. hospitals.

Synopsis: Hospitals were contacted by phone with a standardized, scripted request for the price of an elective total hip arthroplasty. The script described the patient as a 62-year-old grandmother without insurance who is able to pay out of pocket and wishes to compare hospital prices. On the first or second attempt, 40% of top-ranked and 32% of non-top-ranked hospitals were able to provide their price; after five attempts, authors were unable to obtain full pricing information (both hospital and physician fee) from 40% of top-ranked and 37% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Neither fee was made available by 15% of top-ranked and 16% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Wide variation in pricing was found across hospitals. The authors commented on the difficulties they encountered, such as the transfer of calls between departments and the uncertainty of representatives on how to assist.

Bottom line: For individual patients, applying basic economic principles as a consumer might be tiresome and often impossible, with no major differences between top-ranked and non-top-ranked hospitals.

Citation: Rosenthal JA, Lu X, Cram P. Availability of consumer prices from US hospitals for a common surgical procedure. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):427-432.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of recent HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: Are patients able to select health-care providers based on price of service?

Background: With health-care costs rising, patients are encouraged to take a more active role in cost containment. Many initiatives call for greater pricing transparency in the health-care system. This study evaluated price availability for a common surgical procedure.

Study design: Telephone inquiries with standardized interview script.

Setting: Twenty top-ranked orthopedic hospitals and 102 non-top-ranked U.S. hospitals.

Synopsis: Hospitals were contacted by phone with a standardized, scripted request for the price of an elective total hip arthroplasty. The script described the patient as a 62-year-old grandmother without insurance who is able to pay out of pocket and wishes to compare hospital prices. On the first or second attempt, 40% of top-ranked and 32% of non-top-ranked hospitals were able to provide their price; after five attempts, authors were unable to obtain full pricing information (both hospital and physician fee) from 40% of top-ranked and 37% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Neither fee was made available by 15% of top-ranked and 16% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Wide variation in pricing was found across hospitals. The authors commented on the difficulties they encountered, such as the transfer of calls between departments and the uncertainty of representatives on how to assist.

Bottom line: For individual patients, applying basic economic principles as a consumer might be tiresome and often impossible, with no major differences between top-ranked and non-top-ranked hospitals.

Citation: Rosenthal JA, Lu X, Cram P. Availability of consumer prices from US hospitals for a common surgical procedure. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):427-432.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of recent HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: Are patients able to select health-care providers based on price of service?

Background: With health-care costs rising, patients are encouraged to take a more active role in cost containment. Many initiatives call for greater pricing transparency in the health-care system. This study evaluated price availability for a common surgical procedure.

Study design: Telephone inquiries with standardized interview script.

Setting: Twenty top-ranked orthopedic hospitals and 102 non-top-ranked U.S. hospitals.

Synopsis: Hospitals were contacted by phone with a standardized, scripted request for the price of an elective total hip arthroplasty. The script described the patient as a 62-year-old grandmother without insurance who is able to pay out of pocket and wishes to compare hospital prices. On the first or second attempt, 40% of top-ranked and 32% of non-top-ranked hospitals were able to provide their price; after five attempts, authors were unable to obtain full pricing information (both hospital and physician fee) from 40% of top-ranked and 37% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Neither fee was made available by 15% of top-ranked and 16% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Wide variation in pricing was found across hospitals. The authors commented on the difficulties they encountered, such as the transfer of calls between departments and the uncertainty of representatives on how to assist.

Bottom line: For individual patients, applying basic economic principles as a consumer might be tiresome and often impossible, with no major differences between top-ranked and non-top-ranked hospitals.

Citation: Rosenthal JA, Lu X, Cram P. Availability of consumer prices from US hospitals for a common surgical procedure. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):427-432.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of recent HM-relevant literature.

Physician Reviews of Hospital Medicine-Related Research

In This Edition

Literature At A Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Prices for common hospital procedures not readily available

- Antibiotics associated with decreased mortality in acute COPD exacerbation

- Endovascular therapy has no benefit to systemic t-PA in acute stroke

- Net harm observed with rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis

- Noninvasive ventilation more effective, safer for AECOPD patients

- Synthetic cannabinoid use and acute kidney injury

- Dabigatran vs. warfarin in the extended treatment of VTE

- Spironolactone improves diastolic function

- Real-time EMR-based prediction tool for clinical deterioration

- Hypothermia protocol and cardiac arrest

Prices for Common Hospital Procedures Not Readily Available

Clinical question: Are patients able to select health-care providers based on price of service?

Background: With health-care costs rising, patients are encouraged to take a more active role in cost containment. Many initiatives call for greater pricing transparency in the health-care system. This study evaluated price availability for a common surgical procedure.

Study design: Telephone inquiries with standardized interview script.

Setting: Twenty top-ranked orthopedic hospitals and 102 non-top-ranked U.S. hospitals.

Synopsis: Hospitals were contacted by phone with a standardized, scripted request for their price of an elective total hip arthroplasty. The script described the patient as a 62-year-old grandmother without insurance who is able to pay out of pocket and wishes to compare hospital prices. On the first or second attempt, 40% of top-ranked and 32% of non-top-ranked hospitals were able to provide their price; after five attempts, authors were unable to obtain full pricing information (both hospital and physician fee) from 40% of top-ranked and 37% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Neither fee was made available by 15% of top-ranked and 16% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Wide variation of pricing was found across hospitals. The authors commented on the difficulties they encountered, such as the transfer of calls between departments and the uncertainty of representatives on how to assist.

Bottom line: For individual patients, applying basic economic principles as a consumer might be tiresome and often impossible, with no major differences between top-ranked and non-top-ranked hospitals.

Citation: Rosenthal JA, Lu X, Cram P. Availability of consumer prices from US hospitals for a common surgical procedure. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):427-432.

Antibiotics Associated with Decreased Mortality in Acute COPD Exacerbation

Clinical question: Do antibiotics when added to systemic steroids provide clinical benefit for patients with acute COPD exacerbation?

Background: Despite widespread use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute COPD, their benefit is not clear.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.Setting: Four hundred ten U.S. hospitals participating in Perspective, an inpatient administrative database.

Synopsis: More than 50,000 patients treated with systemic steroids for acute COPD exacerbation were included in this study; 85% of them received empiric antibiotics within the first two hospital days. They were compared with those treated with systemic steroids alone. In-hospital mortality was 1.02% for patients on steroids plus antibiotics versus 1.78% on steroids alone. Use of antibiotics was associated with a 40% reduction in the odds of in-hospital mortality (OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50-0.74) and reduced readmissions. In an analysis of matched cohorts, hospital mortality was 1% for patients on antibiotics and 1.8% for patients without antibiotics (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.40-0.71). The risk for readmission for Clostridium difficile colitis was not different between the groups, but other potential adverse effects of antibiotic use, such as development of resistant micro-organisms, were not studied. In a subset analysis, three groups of antibiotics were compared: macrolides, quinolones, and cephalosporins. None was better than another, but those treated with macrolides had a lower readmission rate for C. diff.

Bottom line: Treatment with antibiotics when added to systemic steroids is associated with improved outcomes in acute COPD exacerbations, but there is no clear advantage of one antibiotic class over another.

Citation: Stefan MS, Rothberg MB, Shieh M, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Association between antibiotic treatment and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD treated with systemic steroids. Chest. 2013;143(1):82-90.

Endovascular Therapy Added to Systemic t-PA Has No Benefit in Acute Stroke

Clinical question: Does adding endovascular therapy to intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) reduce disability in acute stroke?

Background: Early systemic t-PA is the only proven reperfusion therapy in acute stroke, but it is unknown if adding localized endovascular therapy is beneficial.

Study design: Randomized, open-label, blinded-outcome trial.

Setting: Fifty-eight centers in North America, Europe, and Australia.

Synopsis: Patients aged 18 to 82 with acute ischemic stroke were eligible if they received t-PA within three hours of enrollment and had moderate to severe neurologic deficit (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] >10, or NIHSS 8 or 9 with CT angiographic evidence of specific major artery occlusion). All patients received standard-dose t-PA; those randomized to endovascular treatment underwent angiography, and, if indicated, underwent one of the endovascular treatments chosen by the neurointerventionalist. The primary outcome measure was a modified Rankin score of 2 or lower (indicating functional independence) at 90 days (assessed by a neurologist).

After enrollment of 656 patients, the trial was terminated early for futility. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome, with 40.8% of patients in the endovascular intervention group and 38.7% in the t-PA-only group having a modified Rankin score of 2 or lower. There was also no difference in mortality or other secondary outcomes, even when the analysis was limited to patients presenting with more severe neurologic deficits.

Bottom line: The addition of endovascular therapy to systemic t-PA in acute ischemic stroke does not improve functional outcomes or mortality.

Citation: Broderick JP, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular therapy after intravenous t-PA versus t-PA alone for stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:893-903.

Rivaroxaban Compared with Enoxaparin for Thromboprophylaxis

Clinical question: Is extended-duration rivaroxaban more effective than standard-duration enoxaparin in preventing deep venous thrombosis in acutely ill medical patients?

Background: Trials have shown benefits of thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients at increased risk of venous thrombosis, but the optimal duration and type of anticoagulation is unknown.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, double-blinded, active-comparator controlled trial.

Setting: Five hundred fifty-two centers in 52 countries.

Synopsis: The trial enrolled 8,428 patients hospitalized with an acute medical condition and reduced mobility. Patients were randomized to receive either enoxaparin for 10 (+/-4) days or rivaroxaban for 35 (+/-4) days. The co-primary composite outcomes were the incidence of asymptomatic proximal deep venous thrombosis, symptomatic deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or death related to venous thromboembolism over 10 days and over 35 days.

Both groups had a 2.7% incidence of the primary endpoint over 10 days; over 35 days, the extended-duration rivaroxaban group had a reduced incidence of the primary endpoint of 4.4% compared with 5.7% for enoxaparin. However, there was an increase of clinically relevant bleeding in the rivaroxaban group, occurring in 2.8% and 4.1% of patients over 10 and 35 days, respectively, compared with 1.2% and 1.7% for enoxaparin.

Overall, there was net harm with rivaroxaban over both time periods: 6.6% and 9.4% of patients in the rivaroxaban group had a negative outcome at 10 and 35 days, compared with 4.4% and 7.8% with enoxaparin.

Bottom line: There was net harm with extended-duration rivaroxaban versus standard-duration enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients.

Citation: Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:513-523.

Noninvasive Ventilation More Effective, Safer for Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD)

Clinical question: What are the patterns in use of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) in patients with AECOPD, and which method produces better outcomes?

Background: Multiple randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have suggested a mortality benefit with NIV compared to standard medical care in AECOPD. However, little evidence exists on head-to-head comparisons of NIV and IMV.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Non-federal, short-term, general, and other specialty hospitals nationwide.

Synopsis: A sample of 67,651 ED visits for AECOPD with acute respiratory failure was analyzed from the National Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) database between 2006 and 2008. The study found that NIV use increased to 16% in 2008 from 14% in 2006. Use varied widely between hospitals and was more utilized in higher-case-volume, nonmetropolitan, and Northeastern hospitals. Compared with IMV, NIV was associated with 46% lower inpatient mortality (risk ratio 0.54, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.50-0.59), shortened hospital length of stay (-3.2 days, 95% CI -3.4 to -2.9), lower hospital charges (-$35,012, 95% CI -$36,848 to -$33,176), and lower risk of iatrogenic pneumothorax (0.05% vs. 0.5%, P<0.001). Causality could not be established given the observational study design.

Bottom line: NIV is associated with better outcomes than IMV in the management of AECOPD, and might be underutilized.

Citation: Tsai CL, Lee WY, Delclos GL, Hanania NA, Camargo CA Jr. Comparative effectiveness of noninvasive ventilation vs. invasive mechanical ventilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with acute respiratory failure. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(4):165-172.

Synthetic Cannabinoid Use May Cause Acute Kidney Injury

Clinical question: Are synthetic cannabinoids associated with acute kidney injury (AKI)?

Background: Synthetic cannabinoids are designer drugs of abuse with a growing popularity in the U.S.

Study design: Retrospective case series.

Setting: Hospitals in Wyoming, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, New York, Kansas, and Oregon.

Synopsis: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an alert when 16 cases of unexplained AKI after exposure to synthetic cannabinoids were reported between March and December 2012. Synthetic cannabinoid use is associated with neurologic, sympathomimetic, and cardiovascular toxicity; however, this is the first case series reporting renal toxicity. The 16 patients included 15 males and one female, aged 15-33 years, with no pre-existing renal disease or nephrotoxic medication consumption. All used synthetic cannabinoids within hours to days before developing nausea, vomiting, abdominal, and flank and/or back pain.

Creatinine peaked one to six days after symptom onset. Five patients required hemodialysis, and all 16 recovered. There was no finding specific for all cases on ultrasound and/or biopsy. Toxicologic analysis of specimens was possible in seven cases and revealed a previously unreported fluorinated synthetic cannabinoid compound XLR-11 in all clinical specimens of patients who used the drug within two days of being tested.

Overall, the analysis did not reveal any single compound or brand that could explain all cases.

Bottom line: Clinicians should be aware of the potential for renal or other toxicities in users of synthetic cannabinoid products and should ask about their use in cases of unexplained AKI.

Citation: Murphy TD, Weidenbach KN, Van Houten C, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(6):93-98.

Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Extended VTE Treatment

Clinical question: Is dabigatran suitable for extended treatment VTE?

Background: In contrast to warfarin (Coumadin), dabigatran (Pradaxa) is given in a fixed dose and does not require frequent laboratory monitoring. Dabigatran has been shown to be noninferior to warfarin in the initial six-month treatment of VTE.

Study design: Two double-blinded, randomized trials: an active-control study and a placebo-control study.

Setting: Two hundred sixty-five sites in 33 countries for the active-control study, and 147 sites in 21 countries for the placebo-control study.

Synopsis: This study enrolled 4,299 adult patients with objectively confirmed, symptomatic, proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. In the active-control study comparing warfarin and dabigatran, recurrent objectively confirmed symptomatic or fatal VTE was observed in 1.8% of patients in the dabigatran group compared with 1.3% of patients in the warfarin group (P=0.01 for noninferiority). While major or clinically relevant bleeding was less frequent with dabigatran compared to warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.54), more acute coronary syndromes were observed with dabigatran (0.9% vs. 0.2%, P=0.02). In the placebo-control study, symptomatic or fatal VTE was observed in 0.4% of patients in the dabigatran group compared with 5.6% in the placebo group. Clinically relevant bleeding was more common with dabigatran (5.3% vs. 1.8%; hazard ratio 2.92).

Bottom line: Treatment with dabigatran met the pre-specified noninferiority margin in this study. However, it is worth noting that patients with VTE given extended treatment with dabigatran had significantly higher rates of recurrent symptomatic or fatal VTE than patients treated with warfarin.

Citation: Schulman S, Kearson C, Kakkar AK, et al. Extended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(8):709-718.

Spironolactone Improves Diastolic Function

Clinical question: What is the efficacy of aldosterone receptor blockers on diastolic function and exercise capacity?

Background: Mineralocorticoid receptor activation by aldosterone contributes to the pathophysiology of heart failure (HF) in patients with and without reduced ejection fraction (EF). Aldosterone receptor blockers (spironolactone) reduce overall and cardiovascular mortality in HF patients with reduced EF; however, its effect on HF patients with preserved EF is unknown.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Ten ambulatory sites in Germany and Austria.

Synopsis: This study enrolled 422 men and women, aged 50 or older, with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II or III HF and preserved EF, and randomized them to receive spironolactone 25 mg daily or placebo for one year.

The endpoints included echocardiographic measures of diastolic function and remodeling; N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT pro-BNP) levels; exercise capacity; quality of life; and HF symptoms.

In the spironolactone group, there was significant improvement in echocardiographic measures of diastolic function and remodeling as well as NT pro-BNP levels. However, there was no difference in exercise capacity, quality of life, or HF symptoms when compared to placebo.

The spironolactone group had significantly lower blood pressure than the control group, which may account for some of the remodeling effects. The study may have been underpowered, and the study population might not have had severe enough disease to detect a difference in clinical measures. It remains unknown if structural changes on echocardiography will translate into clinical benefits.

Bottom line: Compared to placebo, spironolactone did improve diastolic function by echo but did not improve exercise capacity.

Citation: Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt A, et al. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309(8):781-791.

Real-Time, EMR-Based Prediction Tool Accurately Predicts ICU Transfer Risks

Clinical question: Can clinical deterioration be accurately predicted using real-time data from an electronic medical record (EMR), and can it lead to better outcomes using a floor-based intervention?

Background: Research has shown that EMR-based prediction tools can help identify real-time clinical deterioration in ward patients, but an intervention based on these computer-based alerts has not been shown to be effective.

Study design: Randomized controlled crossover study.

Setting: Eight adult medicine wards in an academic medical center in the Midwest.

Synopsis: There were 20,031 patients assigned to intervention versus control based on their floor location. Computerized alerts were generated using a prediction algorithm. For patients admitted to intervention wards, the alerts were sent to the charge nurse via pager. Patients meeting the alert threshold based on the computerized prediction tool had five times higher risk of ICU transfer, and nine times higher risk of death than patients not meeting the alert threshold. Intervention of charge nurse notification via pager did not result in any significant change in length of stay (LOS), ICU transfer, or mortality. Charge nurses in the intervention group were supposed to alert a physician after receiving the computer alert, but the authors did not measure how often this occurred.

Bottom line: A real-time EMR-based prediction tool accurately predicts higher risk of ICU transfer and death, as well as LOS, but a floor-based intervention to alert the charge nurse in real time did not lead to better outcomes.

Citation: Bailey TC, Chen Y, Mao Y, et al. A trial of a real-time alert for clinical deterioration in patients hospitalized on general medicine wards. J Hosp Med. 2013 Feb 25. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2009 [Epub ahead of print].

Hypothermia Protocol and Cardiac Arrest

Clinical question: Is mild therapeutic hypothermia (MTH) following cardiac arrest beneficial and safe?

Background: Those with sudden cardiac arrest often have poor neurologic outcome. There are some studies that show benefit with hypothermia, but information on safety is limited.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Europe, the United Kingdom, the U.S., Canada, Japan, and South Korea.

Synopsis: This study pooled data from 63 studies that looked at MTH protocols in the setting of comatose patients as a result of cardiac arrest. The end points included mortality and any complication potentially attributed to the MTH.

When restricting the analysis to include only randomized controlled trials, MTH was associated with decreased risk of in-hospital mortality (RR=0.75, 95% CI: 0.62-0.92), 30-day mortality (RR=0.61, 95% CI 0.45-0.81), and six-month mortality (RR=0.73, 95% CI 0.61-0.88). MTH was associated with increased risk of arrhythmia (RR=1.25, 95% CI: 1.00-1.55) and hypokalemia (RR=2.35, 95% CI: 1.35-4.11); all other complications were similar between groups.

There were inconsistent results regarding benefit in pediatric patients, as well as comatose patients with non-ventricular fibrillation (non-v-fib) arrest (i.e. asystole or pulseless electrical activity).

Bottom line: Mild therapeutic hypothermia can improve survival of comatose patients after v-fib cardiac arrest and is generally safe.

Citation: Xiao G, Guo Q, Xie X, et al. Safety profile and outcome of mild therapeutic hypothermia in patients following cardiac arrest: systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J. 2013;30:90-100.

In This Edition

Literature At A Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Prices for common hospital procedures not readily available

- Antibiotics associated with decreased mortality in acute COPD exacerbation

- Endovascular therapy has no benefit to systemic t-PA in acute stroke

- Net harm observed with rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis

- Noninvasive ventilation more effective, safer for AECOPD patients

- Synthetic cannabinoid use and acute kidney injury

- Dabigatran vs. warfarin in the extended treatment of VTE

- Spironolactone improves diastolic function

- Real-time EMR-based prediction tool for clinical deterioration

- Hypothermia protocol and cardiac arrest

Prices for Common Hospital Procedures Not Readily Available

Clinical question: Are patients able to select health-care providers based on price of service?

Background: With health-care costs rising, patients are encouraged to take a more active role in cost containment. Many initiatives call for greater pricing transparency in the health-care system. This study evaluated price availability for a common surgical procedure.

Study design: Telephone inquiries with standardized interview script.

Setting: Twenty top-ranked orthopedic hospitals and 102 non-top-ranked U.S. hospitals.

Synopsis: Hospitals were contacted by phone with a standardized, scripted request for their price of an elective total hip arthroplasty. The script described the patient as a 62-year-old grandmother without insurance who is able to pay out of pocket and wishes to compare hospital prices. On the first or second attempt, 40% of top-ranked and 32% of non-top-ranked hospitals were able to provide their price; after five attempts, authors were unable to obtain full pricing information (both hospital and physician fee) from 40% of top-ranked and 37% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Neither fee was made available by 15% of top-ranked and 16% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Wide variation of pricing was found across hospitals. The authors commented on the difficulties they encountered, such as the transfer of calls between departments and the uncertainty of representatives on how to assist.

Bottom line: For individual patients, applying basic economic principles as a consumer might be tiresome and often impossible, with no major differences between top-ranked and non-top-ranked hospitals.

Citation: Rosenthal JA, Lu X, Cram P. Availability of consumer prices from US hospitals for a common surgical procedure. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):427-432.

Antibiotics Associated with Decreased Mortality in Acute COPD Exacerbation

Clinical question: Do antibiotics when added to systemic steroids provide clinical benefit for patients with acute COPD exacerbation?

Background: Despite widespread use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute COPD, their benefit is not clear.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.Setting: Four hundred ten U.S. hospitals participating in Perspective, an inpatient administrative database.

Synopsis: More than 50,000 patients treated with systemic steroids for acute COPD exacerbation were included in this study; 85% of them received empiric antibiotics within the first two hospital days. They were compared with those treated with systemic steroids alone. In-hospital mortality was 1.02% for patients on steroids plus antibiotics versus 1.78% on steroids alone. Use of antibiotics was associated with a 40% reduction in the odds of in-hospital mortality (OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50-0.74) and reduced readmissions. In an analysis of matched cohorts, hospital mortality was 1% for patients on antibiotics and 1.8% for patients without antibiotics (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.40-0.71). The risk for readmission for Clostridium difficile colitis was not different between the groups, but other potential adverse effects of antibiotic use, such as development of resistant micro-organisms, were not studied. In a subset analysis, three groups of antibiotics were compared: macrolides, quinolones, and cephalosporins. None was better than another, but those treated with macrolides had a lower readmission rate for C. diff.

Bottom line: Treatment with antibiotics when added to systemic steroids is associated with improved outcomes in acute COPD exacerbations, but there is no clear advantage of one antibiotic class over another.

Citation: Stefan MS, Rothberg MB, Shieh M, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Association between antibiotic treatment and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD treated with systemic steroids. Chest. 2013;143(1):82-90.

Endovascular Therapy Added to Systemic t-PA Has No Benefit in Acute Stroke

Clinical question: Does adding endovascular therapy to intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) reduce disability in acute stroke?

Background: Early systemic t-PA is the only proven reperfusion therapy in acute stroke, but it is unknown if adding localized endovascular therapy is beneficial.

Study design: Randomized, open-label, blinded-outcome trial.

Setting: Fifty-eight centers in North America, Europe, and Australia.

Synopsis: Patients aged 18 to 82 with acute ischemic stroke were eligible if they received t-PA within three hours of enrollment and had moderate to severe neurologic deficit (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] >10, or NIHSS 8 or 9 with CT angiographic evidence of specific major artery occlusion). All patients received standard-dose t-PA; those randomized to endovascular treatment underwent angiography, and, if indicated, underwent one of the endovascular treatments chosen by the neurointerventionalist. The primary outcome measure was a modified Rankin score of 2 or lower (indicating functional independence) at 90 days (assessed by a neurologist).

After enrollment of 656 patients, the trial was terminated early for futility. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome, with 40.8% of patients in the endovascular intervention group and 38.7% in the t-PA-only group having a modified Rankin score of 2 or lower. There was also no difference in mortality or other secondary outcomes, even when the analysis was limited to patients presenting with more severe neurologic deficits.

Bottom line: The addition of endovascular therapy to systemic t-PA in acute ischemic stroke does not improve functional outcomes or mortality.

Citation: Broderick JP, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular therapy after intravenous t-PA versus t-PA alone for stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:893-903.

Rivaroxaban Compared with Enoxaparin for Thromboprophylaxis

Clinical question: Is extended-duration rivaroxaban more effective than standard-duration enoxaparin in preventing deep venous thrombosis in acutely ill medical patients?

Background: Trials have shown benefits of thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients at increased risk of venous thrombosis, but the optimal duration and type of anticoagulation is unknown.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, double-blinded, active-comparator controlled trial.

Setting: Five hundred fifty-two centers in 52 countries.

Synopsis: The trial enrolled 8,428 patients hospitalized with an acute medical condition and reduced mobility. Patients were randomized to receive either enoxaparin for 10 (+/-4) days or rivaroxaban for 35 (+/-4) days. The co-primary composite outcomes were the incidence of asymptomatic proximal deep venous thrombosis, symptomatic deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or death related to venous thromboembolism over 10 days and over 35 days.

Both groups had a 2.7% incidence of the primary endpoint over 10 days; over 35 days, the extended-duration rivaroxaban group had a reduced incidence of the primary endpoint of 4.4% compared with 5.7% for enoxaparin. However, there was an increase of clinically relevant bleeding in the rivaroxaban group, occurring in 2.8% and 4.1% of patients over 10 and 35 days, respectively, compared with 1.2% and 1.7% for enoxaparin.

Overall, there was net harm with rivaroxaban over both time periods: 6.6% and 9.4% of patients in the rivaroxaban group had a negative outcome at 10 and 35 days, compared with 4.4% and 7.8% with enoxaparin.

Bottom line: There was net harm with extended-duration rivaroxaban versus standard-duration enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients.

Citation: Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:513-523.

Noninvasive Ventilation More Effective, Safer for Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD)

Clinical question: What are the patterns in use of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) in patients with AECOPD, and which method produces better outcomes?

Background: Multiple randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have suggested a mortality benefit with NIV compared to standard medical care in AECOPD. However, little evidence exists on head-to-head comparisons of NIV and IMV.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Non-federal, short-term, general, and other specialty hospitals nationwide.

Synopsis: A sample of 67,651 ED visits for AECOPD with acute respiratory failure was analyzed from the National Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) database between 2006 and 2008. The study found that NIV use increased to 16% in 2008 from 14% in 2006. Use varied widely between hospitals and was more utilized in higher-case-volume, nonmetropolitan, and Northeastern hospitals. Compared with IMV, NIV was associated with 46% lower inpatient mortality (risk ratio 0.54, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.50-0.59), shortened hospital length of stay (-3.2 days, 95% CI -3.4 to -2.9), lower hospital charges (-$35,012, 95% CI -$36,848 to -$33,176), and lower risk of iatrogenic pneumothorax (0.05% vs. 0.5%, P<0.001). Causality could not be established given the observational study design.

Bottom line: NIV is associated with better outcomes than IMV in the management of AECOPD, and might be underutilized.

Citation: Tsai CL, Lee WY, Delclos GL, Hanania NA, Camargo CA Jr. Comparative effectiveness of noninvasive ventilation vs. invasive mechanical ventilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with acute respiratory failure. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(4):165-172.

Synthetic Cannabinoid Use May Cause Acute Kidney Injury

Clinical question: Are synthetic cannabinoids associated with acute kidney injury (AKI)?

Background: Synthetic cannabinoids are designer drugs of abuse with a growing popularity in the U.S.

Study design: Retrospective case series.

Setting: Hospitals in Wyoming, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, New York, Kansas, and Oregon.

Synopsis: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an alert when 16 cases of unexplained AKI after exposure to synthetic cannabinoids were reported between March and December 2012. Synthetic cannabinoid use is associated with neurologic, sympathomimetic, and cardiovascular toxicity; however, this is the first case series reporting renal toxicity. The 16 patients included 15 males and one female, aged 15-33 years, with no pre-existing renal disease or nephrotoxic medication consumption. All used synthetic cannabinoids within hours to days before developing nausea, vomiting, abdominal, and flank and/or back pain.

Creatinine peaked one to six days after symptom onset. Five patients required hemodialysis, and all 16 recovered. There was no finding specific for all cases on ultrasound and/or biopsy. Toxicologic analysis of specimens was possible in seven cases and revealed a previously unreported fluorinated synthetic cannabinoid compound XLR-11 in all clinical specimens of patients who used the drug within two days of being tested.

Overall, the analysis did not reveal any single compound or brand that could explain all cases.

Bottom line: Clinicians should be aware of the potential for renal or other toxicities in users of synthetic cannabinoid products and should ask about their use in cases of unexplained AKI.

Citation: Murphy TD, Weidenbach KN, Van Houten C, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(6):93-98.

Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Extended VTE Treatment

Clinical question: Is dabigatran suitable for extended treatment VTE?

Background: In contrast to warfarin (Coumadin), dabigatran (Pradaxa) is given in a fixed dose and does not require frequent laboratory monitoring. Dabigatran has been shown to be noninferior to warfarin in the initial six-month treatment of VTE.

Study design: Two double-blinded, randomized trials: an active-control study and a placebo-control study.

Setting: Two hundred sixty-five sites in 33 countries for the active-control study, and 147 sites in 21 countries for the placebo-control study.

Synopsis: This study enrolled 4,299 adult patients with objectively confirmed, symptomatic, proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. In the active-control study comparing warfarin and dabigatran, recurrent objectively confirmed symptomatic or fatal VTE was observed in 1.8% of patients in the dabigatran group compared with 1.3% of patients in the warfarin group (P=0.01 for noninferiority). While major or clinically relevant bleeding was less frequent with dabigatran compared to warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.54), more acute coronary syndromes were observed with dabigatran (0.9% vs. 0.2%, P=0.02). In the placebo-control study, symptomatic or fatal VTE was observed in 0.4% of patients in the dabigatran group compared with 5.6% in the placebo group. Clinically relevant bleeding was more common with dabigatran (5.3% vs. 1.8%; hazard ratio 2.92).

Bottom line: Treatment with dabigatran met the pre-specified noninferiority margin in this study. However, it is worth noting that patients with VTE given extended treatment with dabigatran had significantly higher rates of recurrent symptomatic or fatal VTE than patients treated with warfarin.

Citation: Schulman S, Kearson C, Kakkar AK, et al. Extended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(8):709-718.

Spironolactone Improves Diastolic Function

Clinical question: What is the efficacy of aldosterone receptor blockers on diastolic function and exercise capacity?

Background: Mineralocorticoid receptor activation by aldosterone contributes to the pathophysiology of heart failure (HF) in patients with and without reduced ejection fraction (EF). Aldosterone receptor blockers (spironolactone) reduce overall and cardiovascular mortality in HF patients with reduced EF; however, its effect on HF patients with preserved EF is unknown.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Ten ambulatory sites in Germany and Austria.

Synopsis: This study enrolled 422 men and women, aged 50 or older, with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II or III HF and preserved EF, and randomized them to receive spironolactone 25 mg daily or placebo for one year.

The endpoints included echocardiographic measures of diastolic function and remodeling; N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT pro-BNP) levels; exercise capacity; quality of life; and HF symptoms.

In the spironolactone group, there was significant improvement in echocardiographic measures of diastolic function and remodeling as well as NT pro-BNP levels. However, there was no difference in exercise capacity, quality of life, or HF symptoms when compared to placebo.

The spironolactone group had significantly lower blood pressure than the control group, which may account for some of the remodeling effects. The study may have been underpowered, and the study population might not have had severe enough disease to detect a difference in clinical measures. It remains unknown if structural changes on echocardiography will translate into clinical benefits.

Bottom line: Compared to placebo, spironolactone did improve diastolic function by echo but did not improve exercise capacity.

Citation: Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt A, et al. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309(8):781-791.

Real-Time, EMR-Based Prediction Tool Accurately Predicts ICU Transfer Risks

Clinical question: Can clinical deterioration be accurately predicted using real-time data from an electronic medical record (EMR), and can it lead to better outcomes using a floor-based intervention?

Background: Research has shown that EMR-based prediction tools can help identify real-time clinical deterioration in ward patients, but an intervention based on these computer-based alerts has not been shown to be effective.

Study design: Randomized controlled crossover study.

Setting: Eight adult medicine wards in an academic medical center in the Midwest.

Synopsis: There were 20,031 patients assigned to intervention versus control based on their floor location. Computerized alerts were generated using a prediction algorithm. For patients admitted to intervention wards, the alerts were sent to the charge nurse via pager. Patients meeting the alert threshold based on the computerized prediction tool had five times higher risk of ICU transfer, and nine times higher risk of death than patients not meeting the alert threshold. Intervention of charge nurse notification via pager did not result in any significant change in length of stay (LOS), ICU transfer, or mortality. Charge nurses in the intervention group were supposed to alert a physician after receiving the computer alert, but the authors did not measure how often this occurred.

Bottom line: A real-time EMR-based prediction tool accurately predicts higher risk of ICU transfer and death, as well as LOS, but a floor-based intervention to alert the charge nurse in real time did not lead to better outcomes.

Citation: Bailey TC, Chen Y, Mao Y, et al. A trial of a real-time alert for clinical deterioration in patients hospitalized on general medicine wards. J Hosp Med. 2013 Feb 25. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2009 [Epub ahead of print].

Hypothermia Protocol and Cardiac Arrest

Clinical question: Is mild therapeutic hypothermia (MTH) following cardiac arrest beneficial and safe?

Background: Those with sudden cardiac arrest often have poor neurologic outcome. There are some studies that show benefit with hypothermia, but information on safety is limited.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Europe, the United Kingdom, the U.S., Canada, Japan, and South Korea.

Synopsis: This study pooled data from 63 studies that looked at MTH protocols in the setting of comatose patients as a result of cardiac arrest. The end points included mortality and any complication potentially attributed to the MTH.

When restricting the analysis to include only randomized controlled trials, MTH was associated with decreased risk of in-hospital mortality (RR=0.75, 95% CI: 0.62-0.92), 30-day mortality (RR=0.61, 95% CI 0.45-0.81), and six-month mortality (RR=0.73, 95% CI 0.61-0.88). MTH was associated with increased risk of arrhythmia (RR=1.25, 95% CI: 1.00-1.55) and hypokalemia (RR=2.35, 95% CI: 1.35-4.11); all other complications were similar between groups.

There were inconsistent results regarding benefit in pediatric patients, as well as comatose patients with non-ventricular fibrillation (non-v-fib) arrest (i.e. asystole or pulseless electrical activity).

Bottom line: Mild therapeutic hypothermia can improve survival of comatose patients after v-fib cardiac arrest and is generally safe.

Citation: Xiao G, Guo Q, Xie X, et al. Safety profile and outcome of mild therapeutic hypothermia in patients following cardiac arrest: systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J. 2013;30:90-100.

In This Edition

Literature At A Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Prices for common hospital procedures not readily available

- Antibiotics associated with decreased mortality in acute COPD exacerbation

- Endovascular therapy has no benefit to systemic t-PA in acute stroke

- Net harm observed with rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis

- Noninvasive ventilation more effective, safer for AECOPD patients

- Synthetic cannabinoid use and acute kidney injury

- Dabigatran vs. warfarin in the extended treatment of VTE

- Spironolactone improves diastolic function

- Real-time EMR-based prediction tool for clinical deterioration

- Hypothermia protocol and cardiac arrest

Prices for Common Hospital Procedures Not Readily Available

Clinical question: Are patients able to select health-care providers based on price of service?

Background: With health-care costs rising, patients are encouraged to take a more active role in cost containment. Many initiatives call for greater pricing transparency in the health-care system. This study evaluated price availability for a common surgical procedure.

Study design: Telephone inquiries with standardized interview script.

Setting: Twenty top-ranked orthopedic hospitals and 102 non-top-ranked U.S. hospitals.

Synopsis: Hospitals were contacted by phone with a standardized, scripted request for their price of an elective total hip arthroplasty. The script described the patient as a 62-year-old grandmother without insurance who is able to pay out of pocket and wishes to compare hospital prices. On the first or second attempt, 40% of top-ranked and 32% of non-top-ranked hospitals were able to provide their price; after five attempts, authors were unable to obtain full pricing information (both hospital and physician fee) from 40% of top-ranked and 37% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Neither fee was made available by 15% of top-ranked and 16% of non-top-ranked hospitals. Wide variation of pricing was found across hospitals. The authors commented on the difficulties they encountered, such as the transfer of calls between departments and the uncertainty of representatives on how to assist.

Bottom line: For individual patients, applying basic economic principles as a consumer might be tiresome and often impossible, with no major differences between top-ranked and non-top-ranked hospitals.

Citation: Rosenthal JA, Lu X, Cram P. Availability of consumer prices from US hospitals for a common surgical procedure. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):427-432.

Antibiotics Associated with Decreased Mortality in Acute COPD Exacerbation

Clinical question: Do antibiotics when added to systemic steroids provide clinical benefit for patients with acute COPD exacerbation?

Background: Despite widespread use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute COPD, their benefit is not clear.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.Setting: Four hundred ten U.S. hospitals participating in Perspective, an inpatient administrative database.

Synopsis: More than 50,000 patients treated with systemic steroids for acute COPD exacerbation were included in this study; 85% of them received empiric antibiotics within the first two hospital days. They were compared with those treated with systemic steroids alone. In-hospital mortality was 1.02% for patients on steroids plus antibiotics versus 1.78% on steroids alone. Use of antibiotics was associated with a 40% reduction in the odds of in-hospital mortality (OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50-0.74) and reduced readmissions. In an analysis of matched cohorts, hospital mortality was 1% for patients on antibiotics and 1.8% for patients without antibiotics (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.40-0.71). The risk for readmission for Clostridium difficile colitis was not different between the groups, but other potential adverse effects of antibiotic use, such as development of resistant micro-organisms, were not studied. In a subset analysis, three groups of antibiotics were compared: macrolides, quinolones, and cephalosporins. None was better than another, but those treated with macrolides had a lower readmission rate for C. diff.

Bottom line: Treatment with antibiotics when added to systemic steroids is associated with improved outcomes in acute COPD exacerbations, but there is no clear advantage of one antibiotic class over another.

Citation: Stefan MS, Rothberg MB, Shieh M, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Association between antibiotic treatment and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD treated with systemic steroids. Chest. 2013;143(1):82-90.

Endovascular Therapy Added to Systemic t-PA Has No Benefit in Acute Stroke

Clinical question: Does adding endovascular therapy to intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) reduce disability in acute stroke?

Background: Early systemic t-PA is the only proven reperfusion therapy in acute stroke, but it is unknown if adding localized endovascular therapy is beneficial.

Study design: Randomized, open-label, blinded-outcome trial.

Setting: Fifty-eight centers in North America, Europe, and Australia.

Synopsis: Patients aged 18 to 82 with acute ischemic stroke were eligible if they received t-PA within three hours of enrollment and had moderate to severe neurologic deficit (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] >10, or NIHSS 8 or 9 with CT angiographic evidence of specific major artery occlusion). All patients received standard-dose t-PA; those randomized to endovascular treatment underwent angiography, and, if indicated, underwent one of the endovascular treatments chosen by the neurointerventionalist. The primary outcome measure was a modified Rankin score of 2 or lower (indicating functional independence) at 90 days (assessed by a neurologist).

After enrollment of 656 patients, the trial was terminated early for futility. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome, with 40.8% of patients in the endovascular intervention group and 38.7% in the t-PA-only group having a modified Rankin score of 2 or lower. There was also no difference in mortality or other secondary outcomes, even when the analysis was limited to patients presenting with more severe neurologic deficits.

Bottom line: The addition of endovascular therapy to systemic t-PA in acute ischemic stroke does not improve functional outcomes or mortality.

Citation: Broderick JP, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular therapy after intravenous t-PA versus t-PA alone for stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:893-903.

Rivaroxaban Compared with Enoxaparin for Thromboprophylaxis

Clinical question: Is extended-duration rivaroxaban more effective than standard-duration enoxaparin in preventing deep venous thrombosis in acutely ill medical patients?

Background: Trials have shown benefits of thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients at increased risk of venous thrombosis, but the optimal duration and type of anticoagulation is unknown.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, double-blinded, active-comparator controlled trial.

Setting: Five hundred fifty-two centers in 52 countries.

Synopsis: The trial enrolled 8,428 patients hospitalized with an acute medical condition and reduced mobility. Patients were randomized to receive either enoxaparin for 10 (+/-4) days or rivaroxaban for 35 (+/-4) days. The co-primary composite outcomes were the incidence of asymptomatic proximal deep venous thrombosis, symptomatic deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or death related to venous thromboembolism over 10 days and over 35 days.

Both groups had a 2.7% incidence of the primary endpoint over 10 days; over 35 days, the extended-duration rivaroxaban group had a reduced incidence of the primary endpoint of 4.4% compared with 5.7% for enoxaparin. However, there was an increase of clinically relevant bleeding in the rivaroxaban group, occurring in 2.8% and 4.1% of patients over 10 and 35 days, respectively, compared with 1.2% and 1.7% for enoxaparin.

Overall, there was net harm with rivaroxaban over both time periods: 6.6% and 9.4% of patients in the rivaroxaban group had a negative outcome at 10 and 35 days, compared with 4.4% and 7.8% with enoxaparin.

Bottom line: There was net harm with extended-duration rivaroxaban versus standard-duration enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients.

Citation: Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:513-523.

Noninvasive Ventilation More Effective, Safer for Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD)

Clinical question: What are the patterns in use of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) in patients with AECOPD, and which method produces better outcomes?

Background: Multiple randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have suggested a mortality benefit with NIV compared to standard medical care in AECOPD. However, little evidence exists on head-to-head comparisons of NIV and IMV.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Non-federal, short-term, general, and other specialty hospitals nationwide.

Synopsis: A sample of 67,651 ED visits for AECOPD with acute respiratory failure was analyzed from the National Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) database between 2006 and 2008. The study found that NIV use increased to 16% in 2008 from 14% in 2006. Use varied widely between hospitals and was more utilized in higher-case-volume, nonmetropolitan, and Northeastern hospitals. Compared with IMV, NIV was associated with 46% lower inpatient mortality (risk ratio 0.54, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.50-0.59), shortened hospital length of stay (-3.2 days, 95% CI -3.4 to -2.9), lower hospital charges (-$35,012, 95% CI -$36,848 to -$33,176), and lower risk of iatrogenic pneumothorax (0.05% vs. 0.5%, P<0.001). Causality could not be established given the observational study design.

Bottom line: NIV is associated with better outcomes than IMV in the management of AECOPD, and might be underutilized.

Citation: Tsai CL, Lee WY, Delclos GL, Hanania NA, Camargo CA Jr. Comparative effectiveness of noninvasive ventilation vs. invasive mechanical ventilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with acute respiratory failure. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(4):165-172.

Synthetic Cannabinoid Use May Cause Acute Kidney Injury

Clinical question: Are synthetic cannabinoids associated with acute kidney injury (AKI)?

Background: Synthetic cannabinoids are designer drugs of abuse with a growing popularity in the U.S.

Study design: Retrospective case series.

Setting: Hospitals in Wyoming, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, New York, Kansas, and Oregon.

Synopsis: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an alert when 16 cases of unexplained AKI after exposure to synthetic cannabinoids were reported between March and December 2012. Synthetic cannabinoid use is associated with neurologic, sympathomimetic, and cardiovascular toxicity; however, this is the first case series reporting renal toxicity. The 16 patients included 15 males and one female, aged 15-33 years, with no pre-existing renal disease or nephrotoxic medication consumption. All used synthetic cannabinoids within hours to days before developing nausea, vomiting, abdominal, and flank and/or back pain.

Creatinine peaked one to six days after symptom onset. Five patients required hemodialysis, and all 16 recovered. There was no finding specific for all cases on ultrasound and/or biopsy. Toxicologic analysis of specimens was possible in seven cases and revealed a previously unreported fluorinated synthetic cannabinoid compound XLR-11 in all clinical specimens of patients who used the drug within two days of being tested.

Overall, the analysis did not reveal any single compound or brand that could explain all cases.

Bottom line: Clinicians should be aware of the potential for renal or other toxicities in users of synthetic cannabinoid products and should ask about their use in cases of unexplained AKI.

Citation: Murphy TD, Weidenbach KN, Van Houten C, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(6):93-98.

Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Extended VTE Treatment

Clinical question: Is dabigatran suitable for extended treatment VTE?

Background: In contrast to warfarin (Coumadin), dabigatran (Pradaxa) is given in a fixed dose and does not require frequent laboratory monitoring. Dabigatran has been shown to be noninferior to warfarin in the initial six-month treatment of VTE.

Study design: Two double-blinded, randomized trials: an active-control study and a placebo-control study.

Setting: Two hundred sixty-five sites in 33 countries for the active-control study, and 147 sites in 21 countries for the placebo-control study.

Synopsis: This study enrolled 4,299 adult patients with objectively confirmed, symptomatic, proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. In the active-control study comparing warfarin and dabigatran, recurrent objectively confirmed symptomatic or fatal VTE was observed in 1.8% of patients in the dabigatran group compared with 1.3% of patients in the warfarin group (P=0.01 for noninferiority). While major or clinically relevant bleeding was less frequent with dabigatran compared to warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.54), more acute coronary syndromes were observed with dabigatran (0.9% vs. 0.2%, P=0.02). In the placebo-control study, symptomatic or fatal VTE was observed in 0.4% of patients in the dabigatran group compared with 5.6% in the placebo group. Clinically relevant bleeding was more common with dabigatran (5.3% vs. 1.8%; hazard ratio 2.92).

Bottom line: Treatment with dabigatran met the pre-specified noninferiority margin in this study. However, it is worth noting that patients with VTE given extended treatment with dabigatran had significantly higher rates of recurrent symptomatic or fatal VTE than patients treated with warfarin.

Citation: Schulman S, Kearson C, Kakkar AK, et al. Extended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(8):709-718.

Spironolactone Improves Diastolic Function

Clinical question: What is the efficacy of aldosterone receptor blockers on diastolic function and exercise capacity?

Background: Mineralocorticoid receptor activation by aldosterone contributes to the pathophysiology of heart failure (HF) in patients with and without reduced ejection fraction (EF). Aldosterone receptor blockers (spironolactone) reduce overall and cardiovascular mortality in HF patients with reduced EF; however, its effect on HF patients with preserved EF is unknown.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Ten ambulatory sites in Germany and Austria.

Synopsis: This study enrolled 422 men and women, aged 50 or older, with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II or III HF and preserved EF, and randomized them to receive spironolactone 25 mg daily or placebo for one year.

The endpoints included echocardiographic measures of diastolic function and remodeling; N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT pro-BNP) levels; exercise capacity; quality of life; and HF symptoms.

In the spironolactone group, there was significant improvement in echocardiographic measures of diastolic function and remodeling as well as NT pro-BNP levels. However, there was no difference in exercise capacity, quality of life, or HF symptoms when compared to placebo.

The spironolactone group had significantly lower blood pressure than the control group, which may account for some of the remodeling effects. The study may have been underpowered, and the study population might not have had severe enough disease to detect a difference in clinical measures. It remains unknown if structural changes on echocardiography will translate into clinical benefits.

Bottom line: Compared to placebo, spironolactone did improve diastolic function by echo but did not improve exercise capacity.

Citation: Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt A, et al. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309(8):781-791.

Real-Time, EMR-Based Prediction Tool Accurately Predicts ICU Transfer Risks

Clinical question: Can clinical deterioration be accurately predicted using real-time data from an electronic medical record (EMR), and can it lead to better outcomes using a floor-based intervention?

Background: Research has shown that EMR-based prediction tools can help identify real-time clinical deterioration in ward patients, but an intervention based on these computer-based alerts has not been shown to be effective.

Study design: Randomized controlled crossover study.

Setting: Eight adult medicine wards in an academic medical center in the Midwest.

Synopsis: There were 20,031 patients assigned to intervention versus control based on their floor location. Computerized alerts were generated using a prediction algorithm. For patients admitted to intervention wards, the alerts were sent to the charge nurse via pager. Patients meeting the alert threshold based on the computerized prediction tool had five times higher risk of ICU transfer, and nine times higher risk of death than patients not meeting the alert threshold. Intervention of charge nurse notification via pager did not result in any significant change in length of stay (LOS), ICU transfer, or mortality. Charge nurses in the intervention group were supposed to alert a physician after receiving the computer alert, but the authors did not measure how often this occurred.

Bottom line: A real-time EMR-based prediction tool accurately predicts higher risk of ICU transfer and death, as well as LOS, but a floor-based intervention to alert the charge nurse in real time did not lead to better outcomes.

Citation: Bailey TC, Chen Y, Mao Y, et al. A trial of a real-time alert for clinical deterioration in patients hospitalized on general medicine wards. J Hosp Med. 2013 Feb 25. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2009 [Epub ahead of print].

Hypothermia Protocol and Cardiac Arrest

Clinical question: Is mild therapeutic hypothermia (MTH) following cardiac arrest beneficial and safe?

Background: Those with sudden cardiac arrest often have poor neurologic outcome. There are some studies that show benefit with hypothermia, but information on safety is limited.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Europe, the United Kingdom, the U.S., Canada, Japan, and South Korea.

Synopsis: This study pooled data from 63 studies that looked at MTH protocols in the setting of comatose patients as a result of cardiac arrest. The end points included mortality and any complication potentially attributed to the MTH.

When restricting the analysis to include only randomized controlled trials, MTH was associated with decreased risk of in-hospital mortality (RR=0.75, 95% CI: 0.62-0.92), 30-day mortality (RR=0.61, 95% CI 0.45-0.81), and six-month mortality (RR=0.73, 95% CI 0.61-0.88). MTH was associated with increased risk of arrhythmia (RR=1.25, 95% CI: 1.00-1.55) and hypokalemia (RR=2.35, 95% CI: 1.35-4.11); all other complications were similar between groups.

There were inconsistent results regarding benefit in pediatric patients, as well as comatose patients with non-ventricular fibrillation (non-v-fib) arrest (i.e. asystole or pulseless electrical activity).

Bottom line: Mild therapeutic hypothermia can improve survival of comatose patients after v-fib cardiac arrest and is generally safe.

Citation: Xiao G, Guo Q, Xie X, et al. Safety profile and outcome of mild therapeutic hypothermia in patients following cardiac arrest: systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J. 2013;30:90-100.

How is Acute Pericarditis Diagnosed and Treated?

Case

A 32-year-old female with no significant past medical history is evaluated for sharp, left-sided chest pain for five days. Her pain is intermittent, worse with deep inspiration and in the supine position. She denies any shortness of breath. Her temperature is 100.8ºF, but otherwise her vital signs are normal. The physical exam and chest radiograph are unremarkable, but an electrocardiogram shows diffuse ST-segment elevations. The initial troponin is mildly elevated at 0.35 ng/ml.

Could this patient have acute pericarditis? If so, how should she be managed?

Background

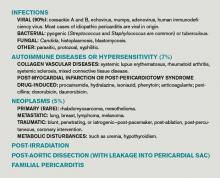

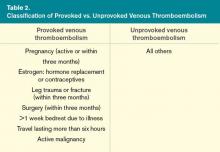

Pericarditis is the most common pericardial disease encountered by hospitalists. As many as 5% of chest pain cases unattributable to myocardial infarction (MI) are diagnosed with pericarditis.1 In immunocompetent individuals, as many as 90% of acute pericarditis cases are viral or idiopathic in etiology.1,2 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis are common culprits in developing countries and immunocompromised hosts.3 Other specific etiologies of acute pericarditis include autoimmune diseases, neoplasms, chest irradiation, trauma, and metabolic disturbances (e.g. uremia). An etiologic classification of acute pericarditis is shown in Table 2 (p. 16).

Pericarditis primarily is a clinical diagnosis. Most patients present with chest pain.4 A pericardial friction rub may or may not be heard (sensitivity 16% to 85%), but when present is nearly 100% specific for pericarditis.2,5 Diffuse ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram (EKG) is present in 60% to 90% of cases, but it can be difficult to differentiate from ST-segment elevations in acute MI.4,6

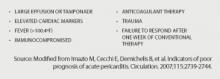

Uncomplicated acute pericarditis often is treated successfully as an outpatient.4 However, patients with high-risk features (see Table 1, right) should be hospitalized for identification and treatment of specific underlying etiology and for monitoring of complications, such as tamponade.7

Our patient has features consistent with pericarditis. In the following sections, we will review the diagnosis and treatment of acute pericarditis.

Review of the Data

How is acute pericarditis diagnosed?

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG and echocardiogram. At least two of the following four criteria must be present for the diagnosis: pleuritic chest pain, pericardial rub, diffuse ST-segment elevation on EKG, and pericardial effusion.8

History. Patients may report fever (46% in one small study of 69 patients) or a recent history of respiratory or gastrointestinal infection (40%).5 Most patients will report pleuritic chest pain. Typically, the pain is improved when sitting up and leaning forward, and gets worse when lying supine.4 Pain might radiate to the trapezius muscle ridge due to the common phrenic nerve innervation of pericardium and trapezius.9 However, pain might be minimal or absent in patients with uremic, neoplastic, tuberculous, or post-irradiation pericarditis.

Physical exam. A pericardial friction rub is nearly 100% specific for a pericarditis diagnosis, but sensitivity can vary (16% to 85%) depending on the frequency of auscultation and underlying etiology.2,5 It is thought to be caused by friction between the parietal and visceral layers of inflamed pericardium. A pericardial rub classically is described as a superficial, high-pitched, scratchy, or squeaking sound best heard with the diaphragm of the stethoscope at the lower left sternal border with the patient leaning forward.

Laboratory data. A complete blood count, metabolic panel, and cardiac enzymes should be checked in all patients with suspected acute pericarditis. Troponin values are elevated in up to one-third of patients, indicating cardiac muscle injury or myopericarditis, but have not been shown to adversely impact hospital length of stay, readmission, or complication rates.5,10 Markers of inflammation (e.g. erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein) are frequently elevated but do not point to a specific underlying etiology. Routine viral cultures and antibody titers are not useful.11

Most cases of pericarditis are presumed idiopathic (viral); however, finding a specific etiology should be considered in patients who do not respond after one week of therapy. Anti-nuclear antibody, complement levels, and rheumatoid factor can serve as screening tests for autoimmune disease. Purified protein derivative or quantiferon testing and HIV testing might be indicated in patients with appropriate risk factors. In cases of suspected tuberculous or neoplastic pericarditis, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy could be warranted.

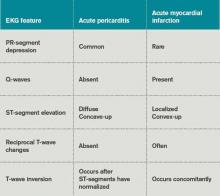

Electrocardiography. The EKG is the most useful test in diagnosing acute pericarditis. EKG changes in acute pericarditis can progress over four stages:

- Stage 1: diffuse ST elevations with or without PR depressions, initially;

- Stage 2: normalization of ST and PR segments, typically after several days;

- Stage 3: diffuse T-wave inversions; and

- Stage 4: normalization of T-waves, typically after weeks or months.

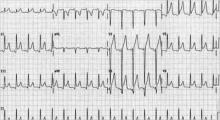

While all four stages are unlikely to be present in a given case, 80% of patients with pericarditis will demonstrate diffuse ST-segment elevations and PR-segment depression (see Figure 2, above).12

Table 3 lists EKG features helpful in differentiating acute pericarditis from acute myocardial infarction.

Chest radiography. Because a pericardial effusion often accompanies pericarditis, a chest radiograph (CXR) should be performed in all suspected cases. The CXR might show enlargement of the cardiac silhouette if more than 250 ml of pericardial fluid is present.3 A CXR also is helpful to diagnose concomitant pulmonary infection, pleural effusion, or mediastinal mass—all findings that could point to an underlying specific etiology of pericarditis and/or pericardial effusion.

Echocardiography. An echocardiogram should be performed in all patients with suspected pericarditis to detect effusion, associated myocardial, or paracardial disease.13 The echocardiogram frequently is normal but could show an effusion in 60%, and tamponade (see Figure 1, p. 15) in 5%, of cases.4

Computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).CT or CMR are the imaging modalities of choice when an echocardiogram is inconclusive or in cases of pericarditis complicated by a hemorrhagic or localized effusion, pericardial thickening, or pericardial mass.14 They also help in precise imaging of neighboring structures, such as lungs or mediastinum.

Pericardial fluid analysis and pericardial biopsy. In cases of refractory pericarditis with effusion, pericardial fluid analysis might provide clues to the underlying etiology. Routine chemistry, cell count, gram and acid fast staining, culture, and cytology should be sent. In addition, acid-fast bacillus staining and culture, adenosine deaminase, and interferon-gamma testing should be ordered when tuberculous pericarditis is suspected. A pericardial biopsy may show granulomas or neoplastic cells. Overall, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy reveal a diagnosis in roughly 20% of cases.11

How is acute pericarditis treated?

Most cases of uncomplicated acute pericarditis are viral and respond well to NSAID plus colchicine therapy.2,4 Failure to respond to NSAIDs plus colchicine—evidenced by persistent fever, pericardial chest pain, new pericardial effusion, or worsening of general illness—within a week of treatment should prompt a search for an underlying systemic illness. If found, treatment should be aimed at the causative illness.

Bacterial pericarditis usually requires surgical drainage in addition to treatment with appropriate antibiotics.11 Tuberculous pericarditis is treated with multidrug therapy; when underlying HIV is present, patients should receive highly active anti-retroviral therapy as well. Steroids and immunosuppressants should be considered in addition to NSAIDs and colchicine in autoimmune pericarditis.10 Neoplastic pericarditis may resolve with chemotherapy but it has a high recurrence rate.13 Uremic pericarditis requires intensified dialysis.

Treatment options for uncomplicated idiopathic or viral pericarditis include:

NSAIDs. It is important to adequately dose NSAIDs when treating acute pericarditis. Initial treatment options include ibuprofen (1,600 to 3,200 mg daily), indomethacin (75 to 150 mg daily) or aspirin (2 to 4 gm daily) for one week.11,15 Aspirin is preferred in patients with ischemic heart disease. For patients with symptoms that persist longer than a week, NSAIDS may be continued, but investigation for an underlying etiology is indicated. Concomitant proton-pump-inhibitor therapy should be considered in patients at high risk for peptic ulcer disease to minimize gastric side effects.

Colchicine. Colchicine has a favorable risk-benefit profile as an adjunct treatment for acute and recurrent pericarditis. Patients experience better symptom relief when treated with both colchicine and an NSAID, compared with NSAIDs alone (88% versus 63%). Recurrence rates are lower with combined therapy (11% versus 32%).16 Colchicine treatment (0.6 mg twice daily after a loading dose of up to 2 mg) is recommended for several months to greater than one year.13,16,17

Glucocorticoids. Routine glucocorticoid use should be avoided in the treatment of acute pericarditis, as it has been associated with an increased risk for recurrence (OR 4.3).16,18 Glucocorticoid use should be considered in cases of pericarditis refractory to NSAIDs and colchicine, cases in which NSAIDs and or colchicine are contraindicated, and in autoimmune or connective-tissue-disease-related pericarditis. Prednisone should be dosed up to 1 mg/kg/day for at least one month, depending on symptom resolution, then tapered after either NSAIDs or colchicine have been started.13 Smaller prednisone doses of up to 0.5 mg/kg/day could be as effective, with the added benefit of reduced side effects and recurrences.19

Invasive treatment. Pericardiocentesis and/or pericardiectomy should be considered when pericarditis is complicated by a large effusion or tamponade, constrictive physiology, or recurrent effusion.11 Pericardiocentesis is the least invasive option and helps provide immediate relief in cases of tamponade or large symptomatic effusions. It is the preferred modality for obtaining pericardial fluid for diagnostic analysis. However, effusions can recur and in those cases pericardial window is preferred, as it provides continued outflow of pericardial fluid. Pericardiectomy is recommended in cases of symptomatic constrictive pericarditis unresponsive to medical therapy.15

Back to the Case

The patient’s presentation—prodrome followed by fever and pleuritic chest pain—is characteristic of acute idiopathic pericarditis. No pericardial rub was heard, but EKG findings were typical. Troponin I elevation suggested underlying myopericarditis. An echocardiogram was unremarkable. Given the likely viral or idiopathic etiology, no further diagnostic tests were ordered to explore the possibility of an underlying systemic illness.

The patient was started on ibuprofen 600 mg every eight hours. She had significant relief of her symptoms within two days. A routine fever workup was negative. She was discharged the following day.

The patient was readmitted three months later with recurrent pleuritic chest pain, which did not improve with resumption of NSAID therapy. Initial troponin I was 0.22 ng/ml, electrocardiogram was unchanged, and an echocardiogram showed small effusion. She was started on ibuprofen 800 mg every eight hours, as well as colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily. Her symptoms resolved the next day and she was discharged with prescriptions for ibuprofen and colchicine. She was instructed to follow up with a primary-care doctor in one week.

At the clinic visit, ibuprofen was tapered but colchicine was continued for another six months. She remained asymptomatic at her six-month clinic follow-up.

Bottom Line

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG findings. Most cases are idiopathic or viral, and can be treated successfully with NSAIDs and colchicine. For cases that do not respond to initial therapy, or cases that present with high-risk features, a specific etiology should be sought.

Dr. Southern is chief of the division of hospital medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y. Dr. Galhorta is an instructor and Drs. Martin, Korcak, and Stehlihova are assistant professors in the department of medicine at Albert Einstein.

References