User login

Early SAVR tops watchful waiting in severe, asymptomatic aortic stenosis: AVATAR

Better to intervene early with a new valve in patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) who are asymptomatic, even during exercise, than to wait for the disease to progress and symptoms to emerge before operating, suggests a small, randomized trial that challenges the guidelines.

Of the trial’s 157 patients, all with negative results on stress tests and normal left ventricular (LV) function despite severe AS, those assigned to early surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), compared with standard watchful waiting, showed a better-than-50% drop in risk for death or major adverse cardiac events (MACE) over 2-3 years. The benefit appeared driven by fewer hospitalizations for heart failure (HF) and deaths in the early-surgery group.

The findings “advocate for early surgery once aortic stenosis becomes significant and regardless of symptom status,” Marko Banovic, MD, PhD, said during his presentation at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Banovic, from the University of Belgrade Medical School in Serbia, is coprincipal investigator on the trial, called AVATAR (Aortic Valve Replacement vs. Conservative Treatment in Asymptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis). He is also lead author on the study’s publication in Circulation, timed to coincide with his AHA presentation.

“The AVATAR findings provide additional evidence to help clinicians in guiding their decision when seeing a patient with significant aortic stenosis, normal left ventricular function, overall low surgical risk, and without significant comorbidities,” Dr. Banovic told this news organization.

European and North American Guidelines favor watchful waiting for asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis, with surgery upon development of symptoms or LV dysfunction, observed Victoria Delgado, MD, PhD, Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, an invited discussant for the AVATAR presentation.

AVATAR does suggest that “early surgery in truly asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction seems to provide better outcomes as compared to the conservative treatment,” she said. “But I think that the long-term follow-up for potential events, such as valve durability or endocarditis, is still needed.”

The trial has strengths, compared with the recent RECOVERY trial, which also concluded in favor of early SAVR over watchful waiting in patients described as asymptomatic with severe aortic stenosis. Dr. Delgado and other observers, however, have pointed out limitations of that trial, including questions about whether the patients were truly asymptomatic – stress testing wasn›t routinely performed.

In AVATAR, all patients were negative at stress testing, which required them to reach their estimated maximum heart rate, Dr. Banovic noted. As he and his colleagues write, the trial expands on RECOVERY “by providing evidence of the benefit of early surgery in a setting representative of a dilemma in decision making, in truly asymptomatic patients with severe but not critical aortic stenosis and normal LV function.”

A role for TAVR?

Guidelines in general “can be very conservative and lag behind evidence a bit,” Patricia A. Pellikka, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., who is not associated with AVATAR, said in an interview.

“I think when we see patients clinically, we can advise them that if they don’t have symptoms and they do have severe aortic stenosis,” she said, “they’re likely going to get symptoms within a reasonably short period of time, according to our retrospective databases, and that doing the intervention early may yield better long-term outcomes.”

The results of AVATAR, in which valve replacement consisted only of SAVR, “probably could be extrapolated” to transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), Dr. Pellikka observed. “Certainly, TAVR is the procedure that patients come asking for. It’s attractive to avoid a major surgery, and it seems very plausible that TAVR would have yielded similar results if that had been a therapy in this trial.”

In practice, patient age and functional status would figure heavily in deciding whether early valve replacement, and which procedure, is appropriate, Dr. Banovic said in an interview. Importantly, the trial’s patients were at low surgical risk and free of major chronic diseases or other important health concerns.

“Frailty and older age are known risk factors for suboptimal recovery” after SAVR, Dr. Banovic said when interviewed. Therefore, frail patients, who were not many in AVATAR, might be “more suitable for TAVR than SAVR, based on the TAVR-vs.-SAVR results in symptomatic AS patients,” he said.

“One might extrapolate experience from AVATAR trial to TAVR, which may lower the bar for TAVR indications,” but that would require more supporting evidence, Dr. Banovic said.

Confirmed asymptomatic

AVATAR, conducted at nine centers in seven countries in the European Union, randomly assigned 157 adults with severe AS by echocardiography and a LV ejection fraction (LVEF) greater than 50% to early SAVR or conservative management. They averaged 67 years in age, and 43% were women.

The trial excluded anyone with dyspnea, syncope, presyncope, angina, or LV dysfunction and anyone with a history of atrial fibrillation or significant cardiac, renal, or lung disease. The cohort’s average Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) score was 1.7%.

The 78 patients in the early-surgery group “were expected” to have the procedure within 8 weeks of randomization, the published report states; the median time was 55 days. Six of them ultimately did not have the surgery. There was only one periprocedural death, for an operative mortality of 1.4%.

The 79 patients assigned to conservative care were later referred for surgery if they developed symptoms, their LVEF dropped below 50%, or they showed a 0.3-m/sec jump in peak aortic jet velocity at follow-up echocardiography. That occurred with 25 patients a median of 400 days after randomization.

The rate of the primary endpoint – death from any cause, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, or unplanned HF hospitalization – was 16.6% in the early-surgery group and 32.9% for those managed conservatively over a median of 32 months. The hazard ratio by intention-to-treat analysis was 0.46 (95% confidence interval, 0.23-0.90; P = .02). The HR for death from any cause or HF hospitalization was 0.40 (95% CI, 0.19-0.84; P = .013). Any differences in the individual endpoints of death, first HF hospitalizations, thromboembolic complications, or major bleeding were not significant.

If early aortic valve replacement is better for patients like those in AVATAR, some sort of screening for previously unknown severe aortic stenosis may seem attractive for selected populations. “Echocardiography would be the screening test for aortic stenosis, but it’s fairly expensive and therefore has never been advocated as a test to screen everyone,” Dr. Pellikka observed.

“But things are changing,” given innovations such as point-of-care ultrasonography and machine learning, she noted. “Artificial intelligence is progressing in its application to echocardiography, and it’s conceivable that in the future, there might be some abbreviated or screening type of test. But I don’t think we’re quite there yet.”

Dr. Banovic had no conflicts; disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Delgado disclosed speaker fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, and GE Healthcare and unrestricted research grants to her institution from Abbott Vascular, Bayer, Biotronik, Bioventrix, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, GE Healthcare, Ionis, and Medtronic. Dr. Pellikka disclosed receiving a research grant from Ultromics and having unspecified modest relationships with GE Healthcare, Lantheus, and OxThera.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Better to intervene early with a new valve in patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) who are asymptomatic, even during exercise, than to wait for the disease to progress and symptoms to emerge before operating, suggests a small, randomized trial that challenges the guidelines.

Of the trial’s 157 patients, all with negative results on stress tests and normal left ventricular (LV) function despite severe AS, those assigned to early surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), compared with standard watchful waiting, showed a better-than-50% drop in risk for death or major adverse cardiac events (MACE) over 2-3 years. The benefit appeared driven by fewer hospitalizations for heart failure (HF) and deaths in the early-surgery group.

The findings “advocate for early surgery once aortic stenosis becomes significant and regardless of symptom status,” Marko Banovic, MD, PhD, said during his presentation at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Banovic, from the University of Belgrade Medical School in Serbia, is coprincipal investigator on the trial, called AVATAR (Aortic Valve Replacement vs. Conservative Treatment in Asymptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis). He is also lead author on the study’s publication in Circulation, timed to coincide with his AHA presentation.

“The AVATAR findings provide additional evidence to help clinicians in guiding their decision when seeing a patient with significant aortic stenosis, normal left ventricular function, overall low surgical risk, and without significant comorbidities,” Dr. Banovic told this news organization.

European and North American Guidelines favor watchful waiting for asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis, with surgery upon development of symptoms or LV dysfunction, observed Victoria Delgado, MD, PhD, Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, an invited discussant for the AVATAR presentation.

AVATAR does suggest that “early surgery in truly asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction seems to provide better outcomes as compared to the conservative treatment,” she said. “But I think that the long-term follow-up for potential events, such as valve durability or endocarditis, is still needed.”

The trial has strengths, compared with the recent RECOVERY trial, which also concluded in favor of early SAVR over watchful waiting in patients described as asymptomatic with severe aortic stenosis. Dr. Delgado and other observers, however, have pointed out limitations of that trial, including questions about whether the patients were truly asymptomatic – stress testing wasn›t routinely performed.

In AVATAR, all patients were negative at stress testing, which required them to reach their estimated maximum heart rate, Dr. Banovic noted. As he and his colleagues write, the trial expands on RECOVERY “by providing evidence of the benefit of early surgery in a setting representative of a dilemma in decision making, in truly asymptomatic patients with severe but not critical aortic stenosis and normal LV function.”

A role for TAVR?

Guidelines in general “can be very conservative and lag behind evidence a bit,” Patricia A. Pellikka, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., who is not associated with AVATAR, said in an interview.

“I think when we see patients clinically, we can advise them that if they don’t have symptoms and they do have severe aortic stenosis,” she said, “they’re likely going to get symptoms within a reasonably short period of time, according to our retrospective databases, and that doing the intervention early may yield better long-term outcomes.”

The results of AVATAR, in which valve replacement consisted only of SAVR, “probably could be extrapolated” to transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), Dr. Pellikka observed. “Certainly, TAVR is the procedure that patients come asking for. It’s attractive to avoid a major surgery, and it seems very plausible that TAVR would have yielded similar results if that had been a therapy in this trial.”

In practice, patient age and functional status would figure heavily in deciding whether early valve replacement, and which procedure, is appropriate, Dr. Banovic said in an interview. Importantly, the trial’s patients were at low surgical risk and free of major chronic diseases or other important health concerns.

“Frailty and older age are known risk factors for suboptimal recovery” after SAVR, Dr. Banovic said when interviewed. Therefore, frail patients, who were not many in AVATAR, might be “more suitable for TAVR than SAVR, based on the TAVR-vs.-SAVR results in symptomatic AS patients,” he said.

“One might extrapolate experience from AVATAR trial to TAVR, which may lower the bar for TAVR indications,” but that would require more supporting evidence, Dr. Banovic said.

Confirmed asymptomatic

AVATAR, conducted at nine centers in seven countries in the European Union, randomly assigned 157 adults with severe AS by echocardiography and a LV ejection fraction (LVEF) greater than 50% to early SAVR or conservative management. They averaged 67 years in age, and 43% were women.

The trial excluded anyone with dyspnea, syncope, presyncope, angina, or LV dysfunction and anyone with a history of atrial fibrillation or significant cardiac, renal, or lung disease. The cohort’s average Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) score was 1.7%.

The 78 patients in the early-surgery group “were expected” to have the procedure within 8 weeks of randomization, the published report states; the median time was 55 days. Six of them ultimately did not have the surgery. There was only one periprocedural death, for an operative mortality of 1.4%.

The 79 patients assigned to conservative care were later referred for surgery if they developed symptoms, their LVEF dropped below 50%, or they showed a 0.3-m/sec jump in peak aortic jet velocity at follow-up echocardiography. That occurred with 25 patients a median of 400 days after randomization.

The rate of the primary endpoint – death from any cause, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, or unplanned HF hospitalization – was 16.6% in the early-surgery group and 32.9% for those managed conservatively over a median of 32 months. The hazard ratio by intention-to-treat analysis was 0.46 (95% confidence interval, 0.23-0.90; P = .02). The HR for death from any cause or HF hospitalization was 0.40 (95% CI, 0.19-0.84; P = .013). Any differences in the individual endpoints of death, first HF hospitalizations, thromboembolic complications, or major bleeding were not significant.

If early aortic valve replacement is better for patients like those in AVATAR, some sort of screening for previously unknown severe aortic stenosis may seem attractive for selected populations. “Echocardiography would be the screening test for aortic stenosis, but it’s fairly expensive and therefore has never been advocated as a test to screen everyone,” Dr. Pellikka observed.

“But things are changing,” given innovations such as point-of-care ultrasonography and machine learning, she noted. “Artificial intelligence is progressing in its application to echocardiography, and it’s conceivable that in the future, there might be some abbreviated or screening type of test. But I don’t think we’re quite there yet.”

Dr. Banovic had no conflicts; disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Delgado disclosed speaker fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, and GE Healthcare and unrestricted research grants to her institution from Abbott Vascular, Bayer, Biotronik, Bioventrix, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, GE Healthcare, Ionis, and Medtronic. Dr. Pellikka disclosed receiving a research grant from Ultromics and having unspecified modest relationships with GE Healthcare, Lantheus, and OxThera.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Better to intervene early with a new valve in patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) who are asymptomatic, even during exercise, than to wait for the disease to progress and symptoms to emerge before operating, suggests a small, randomized trial that challenges the guidelines.

Of the trial’s 157 patients, all with negative results on stress tests and normal left ventricular (LV) function despite severe AS, those assigned to early surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), compared with standard watchful waiting, showed a better-than-50% drop in risk for death or major adverse cardiac events (MACE) over 2-3 years. The benefit appeared driven by fewer hospitalizations for heart failure (HF) and deaths in the early-surgery group.

The findings “advocate for early surgery once aortic stenosis becomes significant and regardless of symptom status,” Marko Banovic, MD, PhD, said during his presentation at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Banovic, from the University of Belgrade Medical School in Serbia, is coprincipal investigator on the trial, called AVATAR (Aortic Valve Replacement vs. Conservative Treatment in Asymptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis). He is also lead author on the study’s publication in Circulation, timed to coincide with his AHA presentation.

“The AVATAR findings provide additional evidence to help clinicians in guiding their decision when seeing a patient with significant aortic stenosis, normal left ventricular function, overall low surgical risk, and without significant comorbidities,” Dr. Banovic told this news organization.

European and North American Guidelines favor watchful waiting for asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis, with surgery upon development of symptoms or LV dysfunction, observed Victoria Delgado, MD, PhD, Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, an invited discussant for the AVATAR presentation.

AVATAR does suggest that “early surgery in truly asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction seems to provide better outcomes as compared to the conservative treatment,” she said. “But I think that the long-term follow-up for potential events, such as valve durability or endocarditis, is still needed.”

The trial has strengths, compared with the recent RECOVERY trial, which also concluded in favor of early SAVR over watchful waiting in patients described as asymptomatic with severe aortic stenosis. Dr. Delgado and other observers, however, have pointed out limitations of that trial, including questions about whether the patients were truly asymptomatic – stress testing wasn›t routinely performed.

In AVATAR, all patients were negative at stress testing, which required them to reach their estimated maximum heart rate, Dr. Banovic noted. As he and his colleagues write, the trial expands on RECOVERY “by providing evidence of the benefit of early surgery in a setting representative of a dilemma in decision making, in truly asymptomatic patients with severe but not critical aortic stenosis and normal LV function.”

A role for TAVR?

Guidelines in general “can be very conservative and lag behind evidence a bit,” Patricia A. Pellikka, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., who is not associated with AVATAR, said in an interview.

“I think when we see patients clinically, we can advise them that if they don’t have symptoms and they do have severe aortic stenosis,” she said, “they’re likely going to get symptoms within a reasonably short period of time, according to our retrospective databases, and that doing the intervention early may yield better long-term outcomes.”

The results of AVATAR, in which valve replacement consisted only of SAVR, “probably could be extrapolated” to transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), Dr. Pellikka observed. “Certainly, TAVR is the procedure that patients come asking for. It’s attractive to avoid a major surgery, and it seems very plausible that TAVR would have yielded similar results if that had been a therapy in this trial.”

In practice, patient age and functional status would figure heavily in deciding whether early valve replacement, and which procedure, is appropriate, Dr. Banovic said in an interview. Importantly, the trial’s patients were at low surgical risk and free of major chronic diseases or other important health concerns.

“Frailty and older age are known risk factors for suboptimal recovery” after SAVR, Dr. Banovic said when interviewed. Therefore, frail patients, who were not many in AVATAR, might be “more suitable for TAVR than SAVR, based on the TAVR-vs.-SAVR results in symptomatic AS patients,” he said.

“One might extrapolate experience from AVATAR trial to TAVR, which may lower the bar for TAVR indications,” but that would require more supporting evidence, Dr. Banovic said.

Confirmed asymptomatic

AVATAR, conducted at nine centers in seven countries in the European Union, randomly assigned 157 adults with severe AS by echocardiography and a LV ejection fraction (LVEF) greater than 50% to early SAVR or conservative management. They averaged 67 years in age, and 43% were women.

The trial excluded anyone with dyspnea, syncope, presyncope, angina, or LV dysfunction and anyone with a history of atrial fibrillation or significant cardiac, renal, or lung disease. The cohort’s average Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) score was 1.7%.

The 78 patients in the early-surgery group “were expected” to have the procedure within 8 weeks of randomization, the published report states; the median time was 55 days. Six of them ultimately did not have the surgery. There was only one periprocedural death, for an operative mortality of 1.4%.

The 79 patients assigned to conservative care were later referred for surgery if they developed symptoms, their LVEF dropped below 50%, or they showed a 0.3-m/sec jump in peak aortic jet velocity at follow-up echocardiography. That occurred with 25 patients a median of 400 days after randomization.

The rate of the primary endpoint – death from any cause, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, or unplanned HF hospitalization – was 16.6% in the early-surgery group and 32.9% for those managed conservatively over a median of 32 months. The hazard ratio by intention-to-treat analysis was 0.46 (95% confidence interval, 0.23-0.90; P = .02). The HR for death from any cause or HF hospitalization was 0.40 (95% CI, 0.19-0.84; P = .013). Any differences in the individual endpoints of death, first HF hospitalizations, thromboembolic complications, or major bleeding were not significant.

If early aortic valve replacement is better for patients like those in AVATAR, some sort of screening for previously unknown severe aortic stenosis may seem attractive for selected populations. “Echocardiography would be the screening test for aortic stenosis, but it’s fairly expensive and therefore has never been advocated as a test to screen everyone,” Dr. Pellikka observed.

“But things are changing,” given innovations such as point-of-care ultrasonography and machine learning, she noted. “Artificial intelligence is progressing in its application to echocardiography, and it’s conceivable that in the future, there might be some abbreviated or screening type of test. But I don’t think we’re quite there yet.”

Dr. Banovic had no conflicts; disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Delgado disclosed speaker fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, and GE Healthcare and unrestricted research grants to her institution from Abbott Vascular, Bayer, Biotronik, Bioventrix, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, GE Healthcare, Ionis, and Medtronic. Dr. Pellikka disclosed receiving a research grant from Ultromics and having unspecified modest relationships with GE Healthcare, Lantheus, and OxThera.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AHA 2021

Fully endovascular mitral valve replacement a limited success in feasibility study

It remains early days for transcatheter mitral-valve replacement (TMVR) as a minimally invasive way to treat severe, mitral regurgitation (MR), but it’s even earlier days for TMVR as an endovascular procedure. Most of the technique’s limited experience with a dedicated mitral prosthesis has involved transapical delivery.

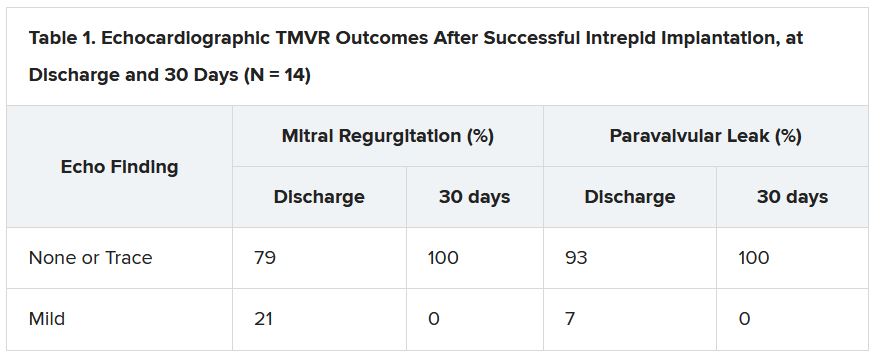

But now a 15-patient study of transfemoral, transeptal TMVR – with a prosthesis designed for the mitral position and previously tested only transapically – has shown good 30-day results in that MR was essentially abolished with virtually no paravalvular leakage.

Nor were there adverse clinical events such as death, stroke, reintervention, or new need for a pacemaker in any of the high-surgical-risk patients with MR in this feasibility study of the transfemoral Intrepid TMVR System (Medtronic). Implantation failed, however, in one patient who then received a surgical valve via sternotomy.

The current cohort is part of a larger ongoing trial that will track whether patients implanted transfemorally with the Intrepid also show reverse remodeling and good clinical outcomes over at least a year. That study, called APOLLO, is one of several exploring dedicated TMVR valves from different companies, with names like SUMMIT, MISCEND, and TIARA-2.

Currently, TMVR is approved in the United States only using one device designed for the aortic position and only for treating failed surgical mitral bioprostheses in high-risk patients.

If the Intrepid transfemoral system has an Achilles’ heel, at least in the current iteration, it might be its 35 F catheter delivery system that requires surgical access to the femoral vein. Seven of the patients in the small series experienced major bleeding events, including six at the femoral access site, listed as major vascular complications.

Overall, the study’s patients “were extremely sick with a lot of comorbidity. A lot of them had atrial fibrillation, a lot of them were on anticoagulation to start with,” observed Firas Zahr, MD, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as part of his presentation of the study at Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics (TCT) 2021, held virtually as well as onsite in Orlando, Florida.

All had moderate-to-severe, usually primary MR; two thirds of the cohort had been in NYHA class III or IV at baseline, and 40% had been hospitalized for heart failure within the past year. Eight had a history of cardiovascular surgery, and eight had diabetes. Their mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) score was 4.7, Dr. Zahr reported.

“At 30 days, there was a significant improvement in their heart failure classification; the vast majority of the patients were [NYHA] class I and class II,” said Dr. Zahr, who is also lead author on the study’s Nov. 6 publication in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Observers of the study at TCT 2021 seemed enthusiastic about the study’s results but recognized that TMVR in its current form still has formidable limitations.

“This is clearly an exciting look into the future and very reassuring to a degree, aside from the complications, which are somewhat expected as we go with 30-plus French devices,” Rajiv Tayal, MD, MPH, said at a press conference on the Intrepid study held before Dr. Zahr’s formal presentation. Dr. Tayal is an interventional cardiologist with Valley Health System, Ridgewood, New Jersey, and New York Medical College, Valhalla.

“I think we’ve all learned that transapical [access] is just not a viable procedure for a lot of these patients, and so we’ve got to get to transfemoral,” Susheel K. Kodali, MD, interventional cardiologist at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, said at the same forum.

A 35 F device “is going to be too big,” he said. However, “it is the first step to iterate to a smaller device.” Dr. Kodali said his center contributed a patient to the study, and he is listed as a coauthor on the publication.

The delivery system’s large profile is only part of the vascular complication issue. Not only did the procedure require surgical cutdown for venous access, but “we were fairly aggressive in anticoagulating these patients with the fear of thrombus formation,” Dr. Zahr said in the discussion following his presentation.

“A postprocedure anticoagulation regimen is recommended within the protocol, but ultimate therapy was left to the discretion of the treating site physician,” the published report states, noting that all 14 patients with successful TMVR were discharged on warfarin. They included 12 who were also put on a single antiplatelet and one given dual antiplatelet therapy on top of the oral anticoagulant.

“One thing that we learned is that we probably should standardize our approach to perioperative anticoagulation,” Dr. Zahr observed. Also, a 29 F sheath for the system is in the works, “and we’re hoping that with smaller sheath size, and hopefully going even to percutaneous, might have an impact on lowering the vascular complications.”

Explanations for the “higher-than-expected vascular complication rate” remains somewhat unclear, agreed an editorial accompanying the study’s publication, “but may include a learning curve with the system, the large introducer sheath, the need for surgical cutdown, and postprocedural anticoagulation.”

For trans-septal TMVR to become a default approach, “venous access will need to be achieved percutaneously and vascular complications need to be infrequent,” contends the editorial, with lead author Mohamad Alkhouli, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“These data provide a glimpse into the future of TMVR. The excellent short-term safety and effectiveness of this still very early-stage procedure represent a major step forward in the field,” they write.

“The main question that the Intrepid early feasibility data raise is whether transfemoral, trans-septal TMVR will evolve to become the preferred strategy over transapical TMVR,” as occurred with transcatheter aortic-valve replacement (TAVR), the editorial states. “The answer is likely yes, but a few matters specific to trans-septal route will need be addressed first.”

Among those matters: The 35 F catheter leaves behind a considerable atrial septal defect (ASD). At operator discretion in this series, 11 patients received an ASD closure device.

None of the remaining four patients “developed significant heart failure or right ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Zahr observed. “So, it seems like those patients who had their ASD left open tolerated it fairly well, at least until 30 days.”

But “we still need to learn what to do with those ASDs,” he said. “What is an acceptable residual shunt and what is an acceptable ASD size is to be determined.”

In general, the editorial notes, “the TMVR population has a high prevalence of cardiomyopathy, and a large residual iatrogenic ASD may lead to worsening volume overload and heart failure decompensation in some patients.”

Insertion of a closure device has its own issues, it continues. “Closure of the ASD might impede future access to the left atrium, which could impact life-long management of this high-risk population. A large septal occluder may hinder potentially needed procedures such as paravalvular leak closure, left atrial appendage closure, or pulmonary vein isolation.”

Patients like those in the current series, Dr. Kodali observed, will face “a lifetime of management challenges, and you want to make sure you don’t take away other options.”

The study was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Zahr reported institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Dr. Kodali disclosed consultant fees from Admedus and Dura Biotech; equity in Dura Biotech, Microinterventional Devices, Thubrika Aortic Valve, Supira, Admedus, TriFlo, and Anona; and institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and JenaValve. The editorial writers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tayal disclosed consultant fees or honoraria from or serving on a speakers bureau for Abiomed, Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott Vascular, and Shockwave Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It remains early days for transcatheter mitral-valve replacement (TMVR) as a minimally invasive way to treat severe, mitral regurgitation (MR), but it’s even earlier days for TMVR as an endovascular procedure. Most of the technique’s limited experience with a dedicated mitral prosthesis has involved transapical delivery.

But now a 15-patient study of transfemoral, transeptal TMVR – with a prosthesis designed for the mitral position and previously tested only transapically – has shown good 30-day results in that MR was essentially abolished with virtually no paravalvular leakage.

Nor were there adverse clinical events such as death, stroke, reintervention, or new need for a pacemaker in any of the high-surgical-risk patients with MR in this feasibility study of the transfemoral Intrepid TMVR System (Medtronic). Implantation failed, however, in one patient who then received a surgical valve via sternotomy.

The current cohort is part of a larger ongoing trial that will track whether patients implanted transfemorally with the Intrepid also show reverse remodeling and good clinical outcomes over at least a year. That study, called APOLLO, is one of several exploring dedicated TMVR valves from different companies, with names like SUMMIT, MISCEND, and TIARA-2.

Currently, TMVR is approved in the United States only using one device designed for the aortic position and only for treating failed surgical mitral bioprostheses in high-risk patients.

If the Intrepid transfemoral system has an Achilles’ heel, at least in the current iteration, it might be its 35 F catheter delivery system that requires surgical access to the femoral vein. Seven of the patients in the small series experienced major bleeding events, including six at the femoral access site, listed as major vascular complications.

Overall, the study’s patients “were extremely sick with a lot of comorbidity. A lot of them had atrial fibrillation, a lot of them were on anticoagulation to start with,” observed Firas Zahr, MD, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as part of his presentation of the study at Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics (TCT) 2021, held virtually as well as onsite in Orlando, Florida.

All had moderate-to-severe, usually primary MR; two thirds of the cohort had been in NYHA class III or IV at baseline, and 40% had been hospitalized for heart failure within the past year. Eight had a history of cardiovascular surgery, and eight had diabetes. Their mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) score was 4.7, Dr. Zahr reported.

“At 30 days, there was a significant improvement in their heart failure classification; the vast majority of the patients were [NYHA] class I and class II,” said Dr. Zahr, who is also lead author on the study’s Nov. 6 publication in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Observers of the study at TCT 2021 seemed enthusiastic about the study’s results but recognized that TMVR in its current form still has formidable limitations.

“This is clearly an exciting look into the future and very reassuring to a degree, aside from the complications, which are somewhat expected as we go with 30-plus French devices,” Rajiv Tayal, MD, MPH, said at a press conference on the Intrepid study held before Dr. Zahr’s formal presentation. Dr. Tayal is an interventional cardiologist with Valley Health System, Ridgewood, New Jersey, and New York Medical College, Valhalla.

“I think we’ve all learned that transapical [access] is just not a viable procedure for a lot of these patients, and so we’ve got to get to transfemoral,” Susheel K. Kodali, MD, interventional cardiologist at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, said at the same forum.

A 35 F device “is going to be too big,” he said. However, “it is the first step to iterate to a smaller device.” Dr. Kodali said his center contributed a patient to the study, and he is listed as a coauthor on the publication.

The delivery system’s large profile is only part of the vascular complication issue. Not only did the procedure require surgical cutdown for venous access, but “we were fairly aggressive in anticoagulating these patients with the fear of thrombus formation,” Dr. Zahr said in the discussion following his presentation.

“A postprocedure anticoagulation regimen is recommended within the protocol, but ultimate therapy was left to the discretion of the treating site physician,” the published report states, noting that all 14 patients with successful TMVR were discharged on warfarin. They included 12 who were also put on a single antiplatelet and one given dual antiplatelet therapy on top of the oral anticoagulant.

“One thing that we learned is that we probably should standardize our approach to perioperative anticoagulation,” Dr. Zahr observed. Also, a 29 F sheath for the system is in the works, “and we’re hoping that with smaller sheath size, and hopefully going even to percutaneous, might have an impact on lowering the vascular complications.”

Explanations for the “higher-than-expected vascular complication rate” remains somewhat unclear, agreed an editorial accompanying the study’s publication, “but may include a learning curve with the system, the large introducer sheath, the need for surgical cutdown, and postprocedural anticoagulation.”

For trans-septal TMVR to become a default approach, “venous access will need to be achieved percutaneously and vascular complications need to be infrequent,” contends the editorial, with lead author Mohamad Alkhouli, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“These data provide a glimpse into the future of TMVR. The excellent short-term safety and effectiveness of this still very early-stage procedure represent a major step forward in the field,” they write.

“The main question that the Intrepid early feasibility data raise is whether transfemoral, trans-septal TMVR will evolve to become the preferred strategy over transapical TMVR,” as occurred with transcatheter aortic-valve replacement (TAVR), the editorial states. “The answer is likely yes, but a few matters specific to trans-septal route will need be addressed first.”

Among those matters: The 35 F catheter leaves behind a considerable atrial septal defect (ASD). At operator discretion in this series, 11 patients received an ASD closure device.

None of the remaining four patients “developed significant heart failure or right ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Zahr observed. “So, it seems like those patients who had their ASD left open tolerated it fairly well, at least until 30 days.”

But “we still need to learn what to do with those ASDs,” he said. “What is an acceptable residual shunt and what is an acceptable ASD size is to be determined.”

In general, the editorial notes, “the TMVR population has a high prevalence of cardiomyopathy, and a large residual iatrogenic ASD may lead to worsening volume overload and heart failure decompensation in some patients.”

Insertion of a closure device has its own issues, it continues. “Closure of the ASD might impede future access to the left atrium, which could impact life-long management of this high-risk population. A large septal occluder may hinder potentially needed procedures such as paravalvular leak closure, left atrial appendage closure, or pulmonary vein isolation.”

Patients like those in the current series, Dr. Kodali observed, will face “a lifetime of management challenges, and you want to make sure you don’t take away other options.”

The study was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Zahr reported institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Dr. Kodali disclosed consultant fees from Admedus and Dura Biotech; equity in Dura Biotech, Microinterventional Devices, Thubrika Aortic Valve, Supira, Admedus, TriFlo, and Anona; and institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and JenaValve. The editorial writers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tayal disclosed consultant fees or honoraria from or serving on a speakers bureau for Abiomed, Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott Vascular, and Shockwave Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It remains early days for transcatheter mitral-valve replacement (TMVR) as a minimally invasive way to treat severe, mitral regurgitation (MR), but it’s even earlier days for TMVR as an endovascular procedure. Most of the technique’s limited experience with a dedicated mitral prosthesis has involved transapical delivery.

But now a 15-patient study of transfemoral, transeptal TMVR – with a prosthesis designed for the mitral position and previously tested only transapically – has shown good 30-day results in that MR was essentially abolished with virtually no paravalvular leakage.

Nor were there adverse clinical events such as death, stroke, reintervention, or new need for a pacemaker in any of the high-surgical-risk patients with MR in this feasibility study of the transfemoral Intrepid TMVR System (Medtronic). Implantation failed, however, in one patient who then received a surgical valve via sternotomy.

The current cohort is part of a larger ongoing trial that will track whether patients implanted transfemorally with the Intrepid also show reverse remodeling and good clinical outcomes over at least a year. That study, called APOLLO, is one of several exploring dedicated TMVR valves from different companies, with names like SUMMIT, MISCEND, and TIARA-2.

Currently, TMVR is approved in the United States only using one device designed for the aortic position and only for treating failed surgical mitral bioprostheses in high-risk patients.

If the Intrepid transfemoral system has an Achilles’ heel, at least in the current iteration, it might be its 35 F catheter delivery system that requires surgical access to the femoral vein. Seven of the patients in the small series experienced major bleeding events, including six at the femoral access site, listed as major vascular complications.

Overall, the study’s patients “were extremely sick with a lot of comorbidity. A lot of them had atrial fibrillation, a lot of them were on anticoagulation to start with,” observed Firas Zahr, MD, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as part of his presentation of the study at Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics (TCT) 2021, held virtually as well as onsite in Orlando, Florida.

All had moderate-to-severe, usually primary MR; two thirds of the cohort had been in NYHA class III or IV at baseline, and 40% had been hospitalized for heart failure within the past year. Eight had a history of cardiovascular surgery, and eight had diabetes. Their mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) score was 4.7, Dr. Zahr reported.

“At 30 days, there was a significant improvement in their heart failure classification; the vast majority of the patients were [NYHA] class I and class II,” said Dr. Zahr, who is also lead author on the study’s Nov. 6 publication in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Observers of the study at TCT 2021 seemed enthusiastic about the study’s results but recognized that TMVR in its current form still has formidable limitations.

“This is clearly an exciting look into the future and very reassuring to a degree, aside from the complications, which are somewhat expected as we go with 30-plus French devices,” Rajiv Tayal, MD, MPH, said at a press conference on the Intrepid study held before Dr. Zahr’s formal presentation. Dr. Tayal is an interventional cardiologist with Valley Health System, Ridgewood, New Jersey, and New York Medical College, Valhalla.

“I think we’ve all learned that transapical [access] is just not a viable procedure for a lot of these patients, and so we’ve got to get to transfemoral,” Susheel K. Kodali, MD, interventional cardiologist at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, said at the same forum.

A 35 F device “is going to be too big,” he said. However, “it is the first step to iterate to a smaller device.” Dr. Kodali said his center contributed a patient to the study, and he is listed as a coauthor on the publication.

The delivery system’s large profile is only part of the vascular complication issue. Not only did the procedure require surgical cutdown for venous access, but “we were fairly aggressive in anticoagulating these patients with the fear of thrombus formation,” Dr. Zahr said in the discussion following his presentation.

“A postprocedure anticoagulation regimen is recommended within the protocol, but ultimate therapy was left to the discretion of the treating site physician,” the published report states, noting that all 14 patients with successful TMVR were discharged on warfarin. They included 12 who were also put on a single antiplatelet and one given dual antiplatelet therapy on top of the oral anticoagulant.

“One thing that we learned is that we probably should standardize our approach to perioperative anticoagulation,” Dr. Zahr observed. Also, a 29 F sheath for the system is in the works, “and we’re hoping that with smaller sheath size, and hopefully going even to percutaneous, might have an impact on lowering the vascular complications.”

Explanations for the “higher-than-expected vascular complication rate” remains somewhat unclear, agreed an editorial accompanying the study’s publication, “but may include a learning curve with the system, the large introducer sheath, the need for surgical cutdown, and postprocedural anticoagulation.”

For trans-septal TMVR to become a default approach, “venous access will need to be achieved percutaneously and vascular complications need to be infrequent,” contends the editorial, with lead author Mohamad Alkhouli, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“These data provide a glimpse into the future of TMVR. The excellent short-term safety and effectiveness of this still very early-stage procedure represent a major step forward in the field,” they write.

“The main question that the Intrepid early feasibility data raise is whether transfemoral, trans-septal TMVR will evolve to become the preferred strategy over transapical TMVR,” as occurred with transcatheter aortic-valve replacement (TAVR), the editorial states. “The answer is likely yes, but a few matters specific to trans-septal route will need be addressed first.”

Among those matters: The 35 F catheter leaves behind a considerable atrial septal defect (ASD). At operator discretion in this series, 11 patients received an ASD closure device.

None of the remaining four patients “developed significant heart failure or right ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Zahr observed. “So, it seems like those patients who had their ASD left open tolerated it fairly well, at least until 30 days.”

But “we still need to learn what to do with those ASDs,” he said. “What is an acceptable residual shunt and what is an acceptable ASD size is to be determined.”

In general, the editorial notes, “the TMVR population has a high prevalence of cardiomyopathy, and a large residual iatrogenic ASD may lead to worsening volume overload and heart failure decompensation in some patients.”

Insertion of a closure device has its own issues, it continues. “Closure of the ASD might impede future access to the left atrium, which could impact life-long management of this high-risk population. A large septal occluder may hinder potentially needed procedures such as paravalvular leak closure, left atrial appendage closure, or pulmonary vein isolation.”

Patients like those in the current series, Dr. Kodali observed, will face “a lifetime of management challenges, and you want to make sure you don’t take away other options.”

The study was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Zahr reported institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Dr. Kodali disclosed consultant fees from Admedus and Dura Biotech; equity in Dura Biotech, Microinterventional Devices, Thubrika Aortic Valve, Supira, Admedus, TriFlo, and Anona; and institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and JenaValve. The editorial writers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tayal disclosed consultant fees or honoraria from or serving on a speakers bureau for Abiomed, Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott Vascular, and Shockwave Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA panel slams Endologix response to stent-graft safety issues

The Food and Drug Administration has long kept a watchful eye over successive iterations of endovascular stent graphs in the Endologix AFX line, designed for repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA). For years, the devices, first approved in 2011, have drawn safety alerts and recalls , stemming from what the agency says was a “higher than expected” risk for potentially injurious or fatal type III endoleaks.

As part of the latest review process, Endologix recently showed regulators data from a rare randomized trial of the AAA endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) technique. The company said the recent postmarket study LEOPARD suggested the type III endoleaks – blood seeping around or through the device into the aneurysm – are no more common with the current AFX2 system than with other available AAA stent-grafts.

Technical upgrades to its AFX line of EVAR devices in recent years have largely resolved the safety issues identified in previous models, the company argued.

But the company’s case was unconvincing for a majority of the FDA Circulatory System Devices Advisory Panel that assembled virtually on Nov. 2. A number of panelists questioned the earnestness with which Endologix worked to rectify the safety alert and recall issues. Many also decried the real-world relevance of the randomized trial presented as evidence, with its follow-up time of only a few years.

The panel that included more than a dozen clinicians – mostly surgeons or interventional cardiologists or radiologists – were not instructed to formally vote on the issues. But it ultimately advised the FDA that more exacting studies with longer follow-ups appear needed to show that the device’s benefits in routine use outweigh its risks, especially for type III endoleaks.

“There isn’t a tremendous amount of confidence” that Endologix had enacted sufficient risk-mitigation measures in the wake of the safety alerts and recalls, chair Richard A. Lange, MD, MBA, Foster School of Medicine and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso, said when summarizing the panel’s take on the day’s proceedings.

Although the stent-graft’s safety seemed improved with recent design changes, the panel wasn’t convinced the upgrades could take the credit, or even that they were aimed specifically at preventing endoleaks, Dr. Lange said. “Nobody feels assurance that the problem has been solved.”

“I believe that the type-three endoleaks pose a challenge to patients, and I have not seen enough data to assure me with a degree of certainty that that problem no longer persists,” said panelist Joaquin E. Cigarroa, MD, a cardiologist at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His take on the LEOPARD trial, moreover, is that it “does not refute that there is an issue, given the duration of follow-up.”

On the other hand, a majority of the panel agreed that, currently, the AFX2’s benefits would likely outweigh risks for patients in narrowly defined high-risk anatomic or clinical scenarios and those with no other endovascular or surgical option.

“I do believe that there are patient subsets where the Endologix graft can play an important and vital role,” surgeon Keith B. Allen, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart & Vascular Institute, Kansas City, Missouri, offered from the panel.

“In patients that don’t have aneurysmal disease but have distal bifurcation proximal iliac disease, it can be a very nice graft to use and solves a problem,” he said. “To remove that graft completely from the market, I believe, would deny a subset of patients.”

But for aortic aneurysms in routine practice, Dr. Allen said, “I think there are some red flags with it.”

Joining the day’s proceedings as a public commenter, surgeon Mark Conrad, MD, St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, Boston, agreed that “there’s not one commercial device out there that is able to handle every anatomy.”

Having options for patients is important, he said, because “the biggest problems we run into are when somebody only uses one graft, and they try to make that fit everything.”

Another public commenter offered a similar take. “I think we haven’t done a great job in the vascular surgery community really honing in on the detailed nuances that separate one device from another,” said Naiem Nassiri, MD, Yale New Haven Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Connecticut.

The Endologix device, he said, “serves a very specific role under certain anatomic configurations and limitations, and really, truly fills a gap” left by other available grafts. It suits a very specific niche, “and I think it needs to be explored further for that.”

Endologix representatives who advise clinicians could play a better role in familiarizing operators with the EVAR system’s strengths and limitations, proposed several panelists, including Minhaj S. Khaja, MD, MBA, interventional radiologist at UVA Health and the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“There definitely needs to be more education of the clinical reps as well as the physicians implanting these devices,” he said, regarding the type III leaks, patient selection issues, appropriate imaging follow-up, “and the potential for increased reintervention.”

All public commenters, Dr. Lange observed, had been invited to disclose potential conflicts of interest, but it was not mandatory and none did so during the public forum. Disclosures of potential conflicts for the panelists are available on the FDA site.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has long kept a watchful eye over successive iterations of endovascular stent graphs in the Endologix AFX line, designed for repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA). For years, the devices, first approved in 2011, have drawn safety alerts and recalls , stemming from what the agency says was a “higher than expected” risk for potentially injurious or fatal type III endoleaks.

As part of the latest review process, Endologix recently showed regulators data from a rare randomized trial of the AAA endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) technique. The company said the recent postmarket study LEOPARD suggested the type III endoleaks – blood seeping around or through the device into the aneurysm – are no more common with the current AFX2 system than with other available AAA stent-grafts.

Technical upgrades to its AFX line of EVAR devices in recent years have largely resolved the safety issues identified in previous models, the company argued.

But the company’s case was unconvincing for a majority of the FDA Circulatory System Devices Advisory Panel that assembled virtually on Nov. 2. A number of panelists questioned the earnestness with which Endologix worked to rectify the safety alert and recall issues. Many also decried the real-world relevance of the randomized trial presented as evidence, with its follow-up time of only a few years.

The panel that included more than a dozen clinicians – mostly surgeons or interventional cardiologists or radiologists – were not instructed to formally vote on the issues. But it ultimately advised the FDA that more exacting studies with longer follow-ups appear needed to show that the device’s benefits in routine use outweigh its risks, especially for type III endoleaks.

“There isn’t a tremendous amount of confidence” that Endologix had enacted sufficient risk-mitigation measures in the wake of the safety alerts and recalls, chair Richard A. Lange, MD, MBA, Foster School of Medicine and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso, said when summarizing the panel’s take on the day’s proceedings.

Although the stent-graft’s safety seemed improved with recent design changes, the panel wasn’t convinced the upgrades could take the credit, or even that they were aimed specifically at preventing endoleaks, Dr. Lange said. “Nobody feels assurance that the problem has been solved.”

“I believe that the type-three endoleaks pose a challenge to patients, and I have not seen enough data to assure me with a degree of certainty that that problem no longer persists,” said panelist Joaquin E. Cigarroa, MD, a cardiologist at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His take on the LEOPARD trial, moreover, is that it “does not refute that there is an issue, given the duration of follow-up.”

On the other hand, a majority of the panel agreed that, currently, the AFX2’s benefits would likely outweigh risks for patients in narrowly defined high-risk anatomic or clinical scenarios and those with no other endovascular or surgical option.

“I do believe that there are patient subsets where the Endologix graft can play an important and vital role,” surgeon Keith B. Allen, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart & Vascular Institute, Kansas City, Missouri, offered from the panel.

“In patients that don’t have aneurysmal disease but have distal bifurcation proximal iliac disease, it can be a very nice graft to use and solves a problem,” he said. “To remove that graft completely from the market, I believe, would deny a subset of patients.”

But for aortic aneurysms in routine practice, Dr. Allen said, “I think there are some red flags with it.”

Joining the day’s proceedings as a public commenter, surgeon Mark Conrad, MD, St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, Boston, agreed that “there’s not one commercial device out there that is able to handle every anatomy.”

Having options for patients is important, he said, because “the biggest problems we run into are when somebody only uses one graft, and they try to make that fit everything.”

Another public commenter offered a similar take. “I think we haven’t done a great job in the vascular surgery community really honing in on the detailed nuances that separate one device from another,” said Naiem Nassiri, MD, Yale New Haven Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Connecticut.

The Endologix device, he said, “serves a very specific role under certain anatomic configurations and limitations, and really, truly fills a gap” left by other available grafts. It suits a very specific niche, “and I think it needs to be explored further for that.”

Endologix representatives who advise clinicians could play a better role in familiarizing operators with the EVAR system’s strengths and limitations, proposed several panelists, including Minhaj S. Khaja, MD, MBA, interventional radiologist at UVA Health and the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“There definitely needs to be more education of the clinical reps as well as the physicians implanting these devices,” he said, regarding the type III leaks, patient selection issues, appropriate imaging follow-up, “and the potential for increased reintervention.”

All public commenters, Dr. Lange observed, had been invited to disclose potential conflicts of interest, but it was not mandatory and none did so during the public forum. Disclosures of potential conflicts for the panelists are available on the FDA site.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has long kept a watchful eye over successive iterations of endovascular stent graphs in the Endologix AFX line, designed for repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA). For years, the devices, first approved in 2011, have drawn safety alerts and recalls , stemming from what the agency says was a “higher than expected” risk for potentially injurious or fatal type III endoleaks.

As part of the latest review process, Endologix recently showed regulators data from a rare randomized trial of the AAA endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) technique. The company said the recent postmarket study LEOPARD suggested the type III endoleaks – blood seeping around or through the device into the aneurysm – are no more common with the current AFX2 system than with other available AAA stent-grafts.

Technical upgrades to its AFX line of EVAR devices in recent years have largely resolved the safety issues identified in previous models, the company argued.

But the company’s case was unconvincing for a majority of the FDA Circulatory System Devices Advisory Panel that assembled virtually on Nov. 2. A number of panelists questioned the earnestness with which Endologix worked to rectify the safety alert and recall issues. Many also decried the real-world relevance of the randomized trial presented as evidence, with its follow-up time of only a few years.

The panel that included more than a dozen clinicians – mostly surgeons or interventional cardiologists or radiologists – were not instructed to formally vote on the issues. But it ultimately advised the FDA that more exacting studies with longer follow-ups appear needed to show that the device’s benefits in routine use outweigh its risks, especially for type III endoleaks.

“There isn’t a tremendous amount of confidence” that Endologix had enacted sufficient risk-mitigation measures in the wake of the safety alerts and recalls, chair Richard A. Lange, MD, MBA, Foster School of Medicine and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso, said when summarizing the panel’s take on the day’s proceedings.

Although the stent-graft’s safety seemed improved with recent design changes, the panel wasn’t convinced the upgrades could take the credit, or even that they were aimed specifically at preventing endoleaks, Dr. Lange said. “Nobody feels assurance that the problem has been solved.”

“I believe that the type-three endoleaks pose a challenge to patients, and I have not seen enough data to assure me with a degree of certainty that that problem no longer persists,” said panelist Joaquin E. Cigarroa, MD, a cardiologist at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His take on the LEOPARD trial, moreover, is that it “does not refute that there is an issue, given the duration of follow-up.”

On the other hand, a majority of the panel agreed that, currently, the AFX2’s benefits would likely outweigh risks for patients in narrowly defined high-risk anatomic or clinical scenarios and those with no other endovascular or surgical option.

“I do believe that there are patient subsets where the Endologix graft can play an important and vital role,” surgeon Keith B. Allen, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart & Vascular Institute, Kansas City, Missouri, offered from the panel.

“In patients that don’t have aneurysmal disease but have distal bifurcation proximal iliac disease, it can be a very nice graft to use and solves a problem,” he said. “To remove that graft completely from the market, I believe, would deny a subset of patients.”

But for aortic aneurysms in routine practice, Dr. Allen said, “I think there are some red flags with it.”

Joining the day’s proceedings as a public commenter, surgeon Mark Conrad, MD, St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, Boston, agreed that “there’s not one commercial device out there that is able to handle every anatomy.”

Having options for patients is important, he said, because “the biggest problems we run into are when somebody only uses one graft, and they try to make that fit everything.”

Another public commenter offered a similar take. “I think we haven’t done a great job in the vascular surgery community really honing in on the detailed nuances that separate one device from another,” said Naiem Nassiri, MD, Yale New Haven Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Connecticut.

The Endologix device, he said, “serves a very specific role under certain anatomic configurations and limitations, and really, truly fills a gap” left by other available grafts. It suits a very specific niche, “and I think it needs to be explored further for that.”

Endologix representatives who advise clinicians could play a better role in familiarizing operators with the EVAR system’s strengths and limitations, proposed several panelists, including Minhaj S. Khaja, MD, MBA, interventional radiologist at UVA Health and the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“There definitely needs to be more education of the clinical reps as well as the physicians implanting these devices,” he said, regarding the type III leaks, patient selection issues, appropriate imaging follow-up, “and the potential for increased reintervention.”

All public commenters, Dr. Lange observed, had been invited to disclose potential conflicts of interest, but it was not mandatory and none did so during the public forum. Disclosures of potential conflicts for the panelists are available on the FDA site.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FFR-guided PCI falls short vs. surgery in multivessel disease: FAME 3

Coronary stenting guided by fractional flow reserve (FFR) readings, considered to reflect the targeted lesion’s functional impact, was no match for coronary bypass surgery (CABG) in patients with multivessel disease (MVD) in a major international randomized trial.

Indeed, FFR-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using one of the latest drug-eluting stents (DES) seemed to perform poorly in the trial, compared with surgery, apparently upping the risk for clinical events by 50% over 1 year.

Designed statistically for noninferiority, the third Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation (FAME 3) trial, with 1,500 randomized patients, showed that FFR-guided PCI was “not noninferior” to CABG. Of those randomized to PCI, 10.6% met the 1-year primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE), compared with only 6.9% of patients assigned to CABG.

The trial enrolled only patients with three-vessel coronary disease with no left-main coronary artery involvement, who were declared by their institution’s multidisciplinary heart team to be appropriate for either form of revascularization.

One of the roles of FFR for PCI guidance is to identify significant lesions “that are underrecognized by the angiogram,” which is less likely to happen in patients with very complex coronary anatomy, study chair William F. Fearon, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview.

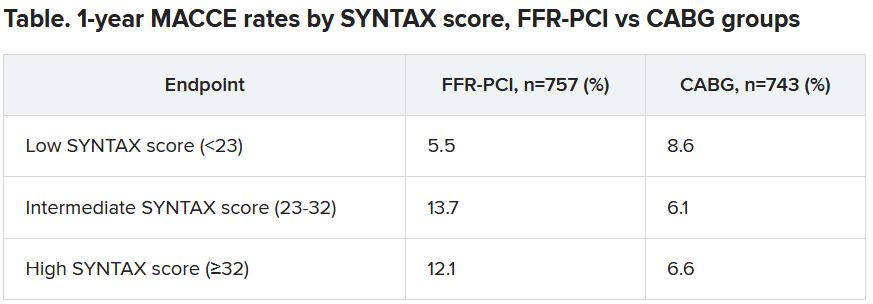

“That’s what we saw in a subgroup analysis based on SYNTAX score,” an index of lesion complexity. “In patients with very high SYNTAX scores, CABG outperformed FFR-guided PCI. But if you look at patients with low SYNTAX scores, actually, FFR-guided PCI outperformed CABG for 1-year MACCE.”

Dr. Fearon is lead author on the study’s Nov. 4, 2021, publication in the New England Journal of Medicine, its release timed to coincide with his presentation of the trial at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, held virtually and live in Orlando and sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

He noted that FAME-3 “wasn’t designed or powered to test for superiority,” so its results do not imply CABG is superior to FFR-PCI in patients with MVD, and remains “inconclusive” on that question.

“I think what this study does is provide both the physician and patients more contemporary data and information on options and expected outcomes in multivessel disease. So if you are a patient who has less complex disease, I think you can feel comfortable that you will get an equivalent result with FFR-guided PCI.” But, at least based on FAME-3, Dr. Fearon said, CABG provides better outcomes in patients with more complex disease.

“I think there are still patients that look at trade-offs. Some patients will accept a higher event rate in order to avoid a long recovery, and vice versa.” So the trial may allow patients and physicians to make more informed decisions, he said.

A main message of FAME-3 “is that we’re getting very good results with three-vessel PCI, but better results with surgery,” Ran Kornowski, MD, Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, and Tel Aviv University, said as a discussant following Dr. Fearon’s presentation of the trial. The subanalysis by SYNTAX score, he agreed, probably could be used as part of shared decision-making with patients.

Not all that surprising

“It’s a well-designed study, with a lot of patients,” said surgeon Frank W. Sellke, MD, of Rhode Island Hospital, Miriam Hospital, and Brown University, all in Providence.

“I don’t think it’s all that surprising,” he said in an interview. “It’s very consistent with what other studies have shown, that for three-vessel disease, surgery tends to have the edge,” even when pitted against FFR-guided PCI.

Indeed, pressure-wire FFR-PCI has a spotty history, even as an alternative to standard angiography-based PCI. For example, it has performed well in registry and other cohort studies but showed no advantage in the all-comers RIPCORD-2 trial or in the setting of complete revascularization PCI for acute MI in FLOWER-MI. And it emitted an increased-mortality signal in the prematurely halted FUTURE trial.

In FAME-3, “the 1-year follow-up was the best chance for FFR-PCI to be noninferior to CABG. The CABG advantage is only going to get better with time if prior experience and pathobiology is true,” Sanjay Kaul, MD, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

Overall, “the quality and quantity of evidence is insufficient to support FFR-guided PCI” in patients with complex coronary artery disease (CAD), he said. “I would also argue that the evidence for FFR-guided PCI for simple CAD is also not high quality.”

Dr. Kaul also blasted the claim that FFR-PCI was seen to perform better against CABG in patients with low SYNTAX scores. “In general, one cannot use a positive subgroup in a null or negative trial, as is the case with FAME-3, to ‘rescue’ the treatment intervention.” Such a positive subgroup finding, he said, “would at best be deemed hypothesis-generating and not hypothesis validating.”

Dr. Fearon agreed that the subgroup analysis by SYNTAX score, though prespecified, was only hypothesis generating. “But I think that other studies have shown the same thing – that in less complex disease, the two strategies appear to perform in a similar fashion.”

The FAME-3 trial’s 1,500 patients were randomly assigned at 48 centers to undergo standard CABG or FFR-guided PCI with Resolute Integrity (Medtronic) zotarolimus-eluting DES. Lesions with a pressure-wire FFR of 0.80 or less were stented and those with higher FFR readings were deferred.

The 1-year hazard ratio for the primary endpoint—a composite of death from any cause, MI, stroke, or repeat revascularization – was 1.5 (95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.2) with a noninferiority P value of .35 for the comparison of FFR-PCI versus CABG.

FFR-guided PCI fared significantly better than CABG for some safety endpoints, including major bleeding (1.6% vs 3.8%, P < .01), arrhythmia including atrial fibrillation (2.4% vs. 14.1%, P < .001), acute kidney injury (0.1% vs 0.9%, P < .04), and 30-day rehospitalization (5.5% vs 10.2%, P < .001).

Did the primary endpoint favor CABG?

At a media briefing prior to Dr. Fearon’s TCT 2021 presentation of the trail, Roxana Mehran, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, proposed that the inclusion of repeat revascularization in the trial’s composite primary endpoint tilted the outcome in favor of CABG. “To me, the FAME-3 results are predictable because repeat revascularization is in the equation.”

It’s well recognized that the endpoint is less likely after CABG than PCI. The latter treats focal lesions that are a limited part of a coronary artery in which CAD is still likely progressing. CABG, on the other hand, can bypass longer segments of diseased artery.

Indeed, as Dr. Fearon reported, the rates of death, MI, or stroke excluding repeat revascularization were 7.3% with FFR-PCI and 5.2% for CABG, for an HR of 1.4 (95% CI, 0.9-2.1).

Dr. Mehran also proposed that intravascular-ultrasound (IVUS) guidance, had it been part of the trial, could potentially have boosted the performance of FFR-PCI.

Repeat revascularization, Dr. Kaul agreed, “should not have been included” in the trial’s primary endpoint. It had been added “to amplify events and to minimize sample size. Not including revascularization would render the sample size prohibitive. There is always give and take in designing clinical trials.”

And he agreed that “IVUS-based PCI optimization would have further improved PCI outcomes.” However, “IVUS plus FFR adds to the procedural burden and limited resources available.” Dr. Fearon said when interviewed that the trial’s definition of procedural MI, a component of the primary endpoint, might potentially be seen as controversial. Procedural MIs in both the PCI and CABG groups were required to meet the standards of CABG-related type-5 MI according to the third and fourth Universal Definitions. The had also had to be accompanied by “a significant finding like new Q waves or a new wall-motion abnormality on echocardiography,” he said.

“That’s fairly strict. Because of that, we had a low rate of periprocedural MI and it was similar between the two groups, around 1.5% in both arms.”

FAME-3 was funded by Medtronic and Abbott Vascular. Dr. Kaul disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kornowsky receives royalties from or holds intellectual property rights with CathWorks. Dr. Mehran disclosed financial ties to numerous pharmaceutical and device companies, and that she, her spouse, or her institution hold equity in Elixir Medical, Applied Therapeutics, and ControlRad.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Coronary stenting guided by fractional flow reserve (FFR) readings, considered to reflect the targeted lesion’s functional impact, was no match for coronary bypass surgery (CABG) in patients with multivessel disease (MVD) in a major international randomized trial.

Indeed, FFR-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using one of the latest drug-eluting stents (DES) seemed to perform poorly in the trial, compared with surgery, apparently upping the risk for clinical events by 50% over 1 year.

Designed statistically for noninferiority, the third Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation (FAME 3) trial, with 1,500 randomized patients, showed that FFR-guided PCI was “not noninferior” to CABG. Of those randomized to PCI, 10.6% met the 1-year primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE), compared with only 6.9% of patients assigned to CABG.

The trial enrolled only patients with three-vessel coronary disease with no left-main coronary artery involvement, who were declared by their institution’s multidisciplinary heart team to be appropriate for either form of revascularization.

One of the roles of FFR for PCI guidance is to identify significant lesions “that are underrecognized by the angiogram,” which is less likely to happen in patients with very complex coronary anatomy, study chair William F. Fearon, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview.

“That’s what we saw in a subgroup analysis based on SYNTAX score,” an index of lesion complexity. “In patients with very high SYNTAX scores, CABG outperformed FFR-guided PCI. But if you look at patients with low SYNTAX scores, actually, FFR-guided PCI outperformed CABG for 1-year MACCE.”

Dr. Fearon is lead author on the study’s Nov. 4, 2021, publication in the New England Journal of Medicine, its release timed to coincide with his presentation of the trial at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, held virtually and live in Orlando and sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

He noted that FAME-3 “wasn’t designed or powered to test for superiority,” so its results do not imply CABG is superior to FFR-PCI in patients with MVD, and remains “inconclusive” on that question.

“I think what this study does is provide both the physician and patients more contemporary data and information on options and expected outcomes in multivessel disease. So if you are a patient who has less complex disease, I think you can feel comfortable that you will get an equivalent result with FFR-guided PCI.” But, at least based on FAME-3, Dr. Fearon said, CABG provides better outcomes in patients with more complex disease.

“I think there are still patients that look at trade-offs. Some patients will accept a higher event rate in order to avoid a long recovery, and vice versa.” So the trial may allow patients and physicians to make more informed decisions, he said.

A main message of FAME-3 “is that we’re getting very good results with three-vessel PCI, but better results with surgery,” Ran Kornowski, MD, Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, and Tel Aviv University, said as a discussant following Dr. Fearon’s presentation of the trial. The subanalysis by SYNTAX score, he agreed, probably could be used as part of shared decision-making with patients.

Not all that surprising

“It’s a well-designed study, with a lot of patients,” said surgeon Frank W. Sellke, MD, of Rhode Island Hospital, Miriam Hospital, and Brown University, all in Providence.

“I don’t think it’s all that surprising,” he said in an interview. “It’s very consistent with what other studies have shown, that for three-vessel disease, surgery tends to have the edge,” even when pitted against FFR-guided PCI.

Indeed, pressure-wire FFR-PCI has a spotty history, even as an alternative to standard angiography-based PCI. For example, it has performed well in registry and other cohort studies but showed no advantage in the all-comers RIPCORD-2 trial or in the setting of complete revascularization PCI for acute MI in FLOWER-MI. And it emitted an increased-mortality signal in the prematurely halted FUTURE trial.

In FAME-3, “the 1-year follow-up was the best chance for FFR-PCI to be noninferior to CABG. The CABG advantage is only going to get better with time if prior experience and pathobiology is true,” Sanjay Kaul, MD, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.