User login

Factors Influencing Patient Preferences for Phototherapy: A Survey Study

Phototherapy—particularly UVB phototherapy, which utilizes UVB rays of specific wavelengths within the UV spectrum—is indicated for a wide variety of dermatoses. In-office and at-home UVB treatments commonly are used, as are salon tanning and sunbathing. When selecting a form of phototherapy, patients are likely to consider safety, cost, effectiveness, insurance issues, and convenience. Research on patient preferences; the reasons for these preferences; and which options patients perceive to be the safest, most cost-effective, efficacious, and convenient is lacking. We aimed to assess the forms of phototherapy that patients would most consider using; the factors influencing patient preferences; and the forms patients perceived as the safest and most cost-effective, efficacious, and convenient.

Methods

Study Participants—We recruited 500 Amazon Mechanical Turk users who were 18 years or older to complete our REDCap-generated survey. The study was approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board (Winston-Salem, North Carolina).

Evaluation—Participants were asked, “If you were diagnosed with a skin disease that benefited from UV therapy, which of the following forms of UV therapy would you consider choosing?” Participants were instructed to choose all of the forms they would consider using. Available options included in-office UV, at-home UV, home tanning, salon tanning, sunbathing, and other. Participants were asked to select which factors—from safety, cost, effectiveness, issues with insurance, convenience, and other—influenced their decision-making; which form of phototherapy they would most consider along with the factors that influenced their preference for this specific form of phototherapy; and which options they considered to be safest and most cost-effective, efficacious, and convenient. Participants were asked to provide basic sociodemographic information, level of education, income, insurance status (private, Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans Affairs, and uninsured), and distance from the nearest dermatologist.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive and inferential statistics (χ2 test) were used to analyze the data with a significance set at P<.05.

Results

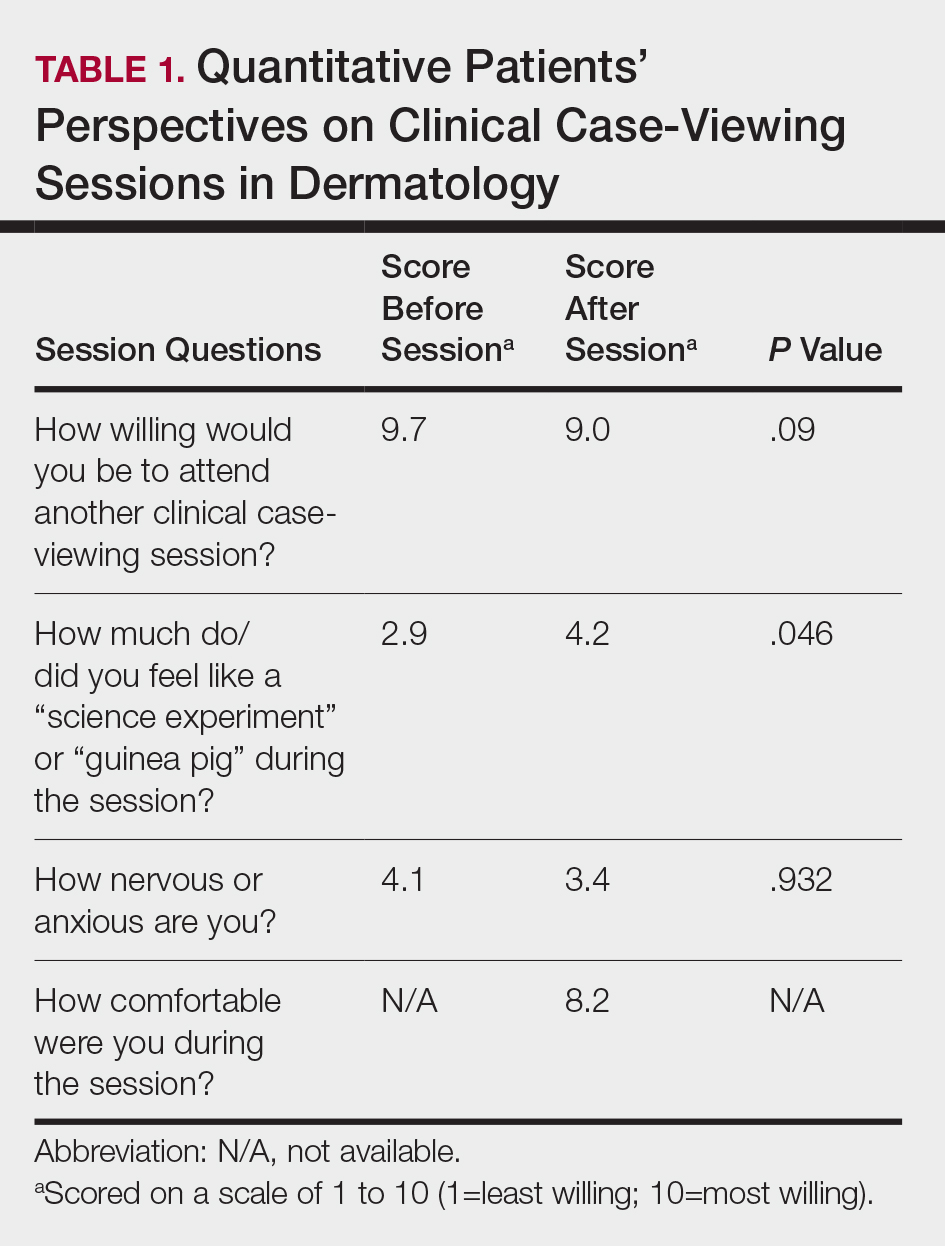

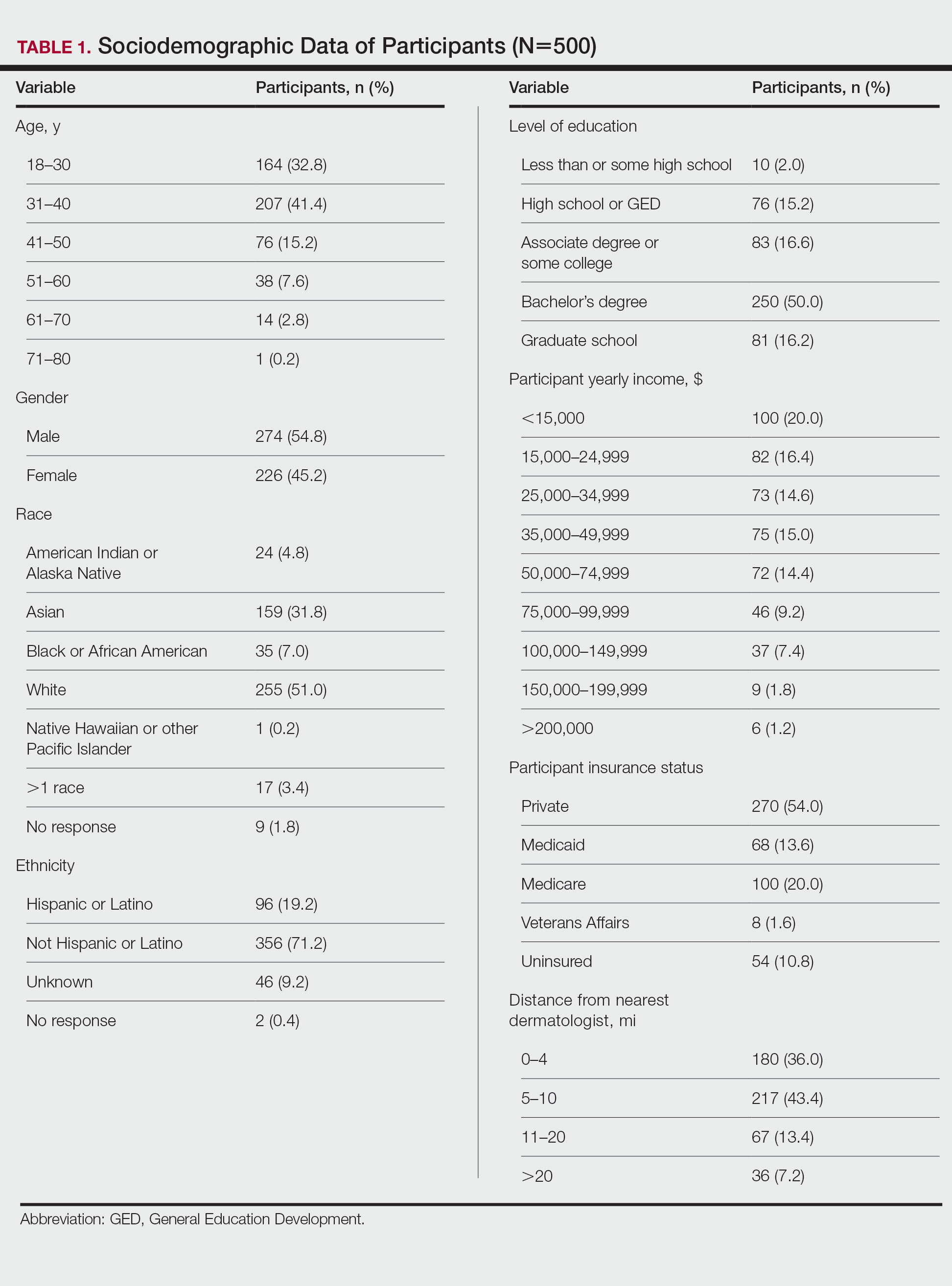

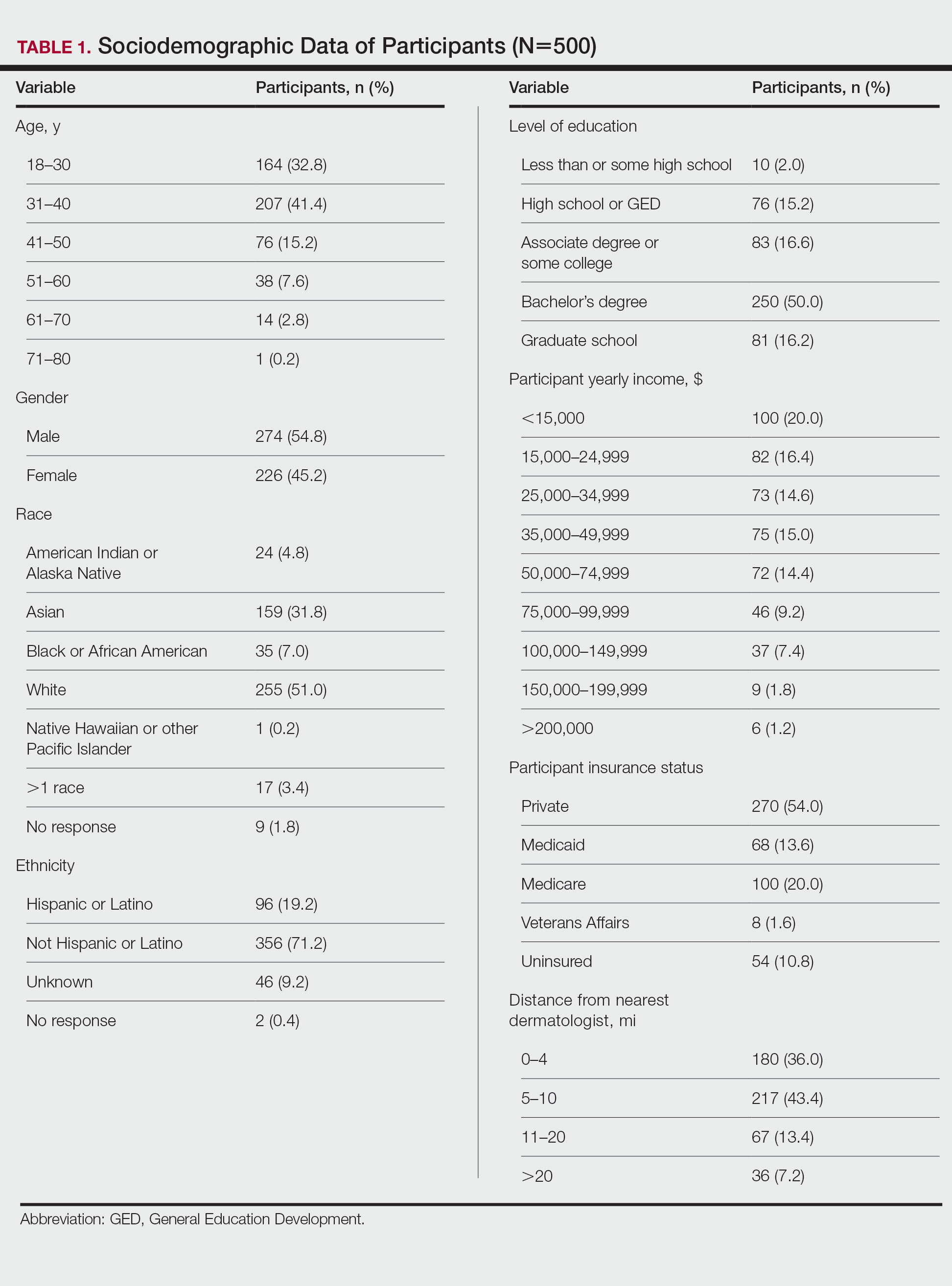

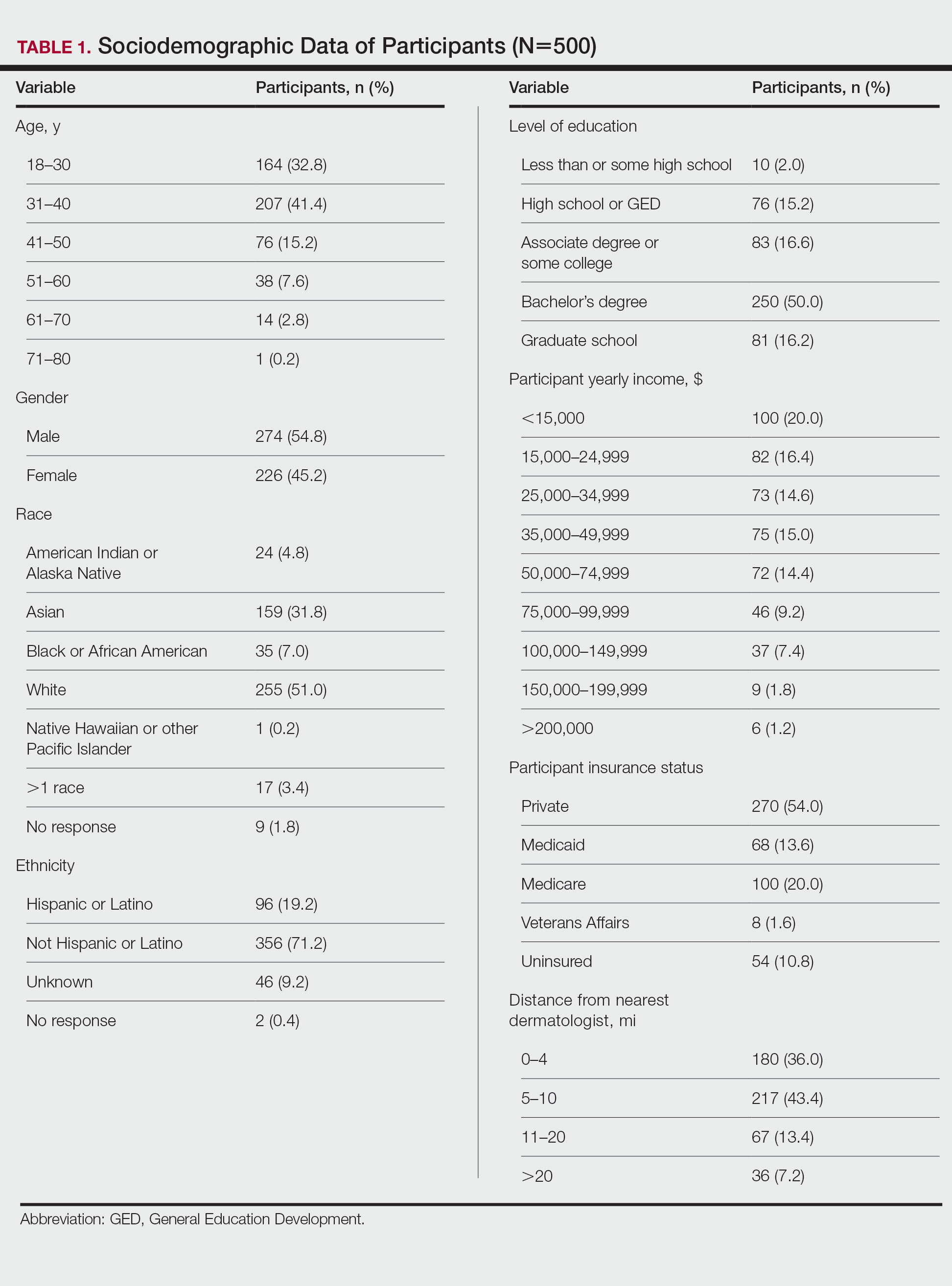

Five hundred participants completed the survey (Table 1).

Factors Influencing Patient Preferences—When asked to select all forms of phototherapy they would consider, 186 (37.2%) participants selected in-office UVB, 263 (52.6%) selected at-home UV, 141 (28.2%) selected home tanning, 117 (23.4%) selected salon tanning, 191 (38.2%) selected sunbathing, and 3 (0.6%) selected other. Participants who selected in-office UVB as an option were more likely to also select salon tanning (P<.012). No other relationship was found between the UVB options and the tanning options. When asked which factors influenced their phototherapy preferences, 295 (59%) selected convenience, 266 (53.2%) selected effectiveness, 220 (44%) selected safety, 218 (43.6%) selected cost, 72 (14.4%) selected issues with insurance, and 4 (0.8%) selected other. Forms of Phototherapy Patients Consider Using—When asked which form of phototherapy they would most consider using, 179 (35.8%) participants selected at-home UVB, 108 (21.6%) selected sunbathing, 92 (18.4%) selected in-office UVB, 62 (12.4%) selected home-tanning, 57 (11.4%) selected salon tanning, 1 (0.2%) selected other, and 1 participant provided no response (P<.001).

Reasons for Using Phototherapy—Of the 179 who selected at-home UVB, 125 (70%) cited convenience as a reason. Of the 108 who selected salon tanning as their top choice, 62 (57%) cited cost as a reason. Convenience (P<.001), cost (P<.001), and safety (P=.023) were related to top preference. Issues with insurance did not have a statistically significant relationship with the top preference. However, participant insurance type was related to top phototherapy preference (P=.021), with privately insured patients more likely to select in-office UVB, whereas those with Medicaid and Medicare were more likely to select home or salon tanning. Efficacy was not related to top preference. Furthermore, age, gender, education, income, and distance from nearest dermatologist were not related to top preference.

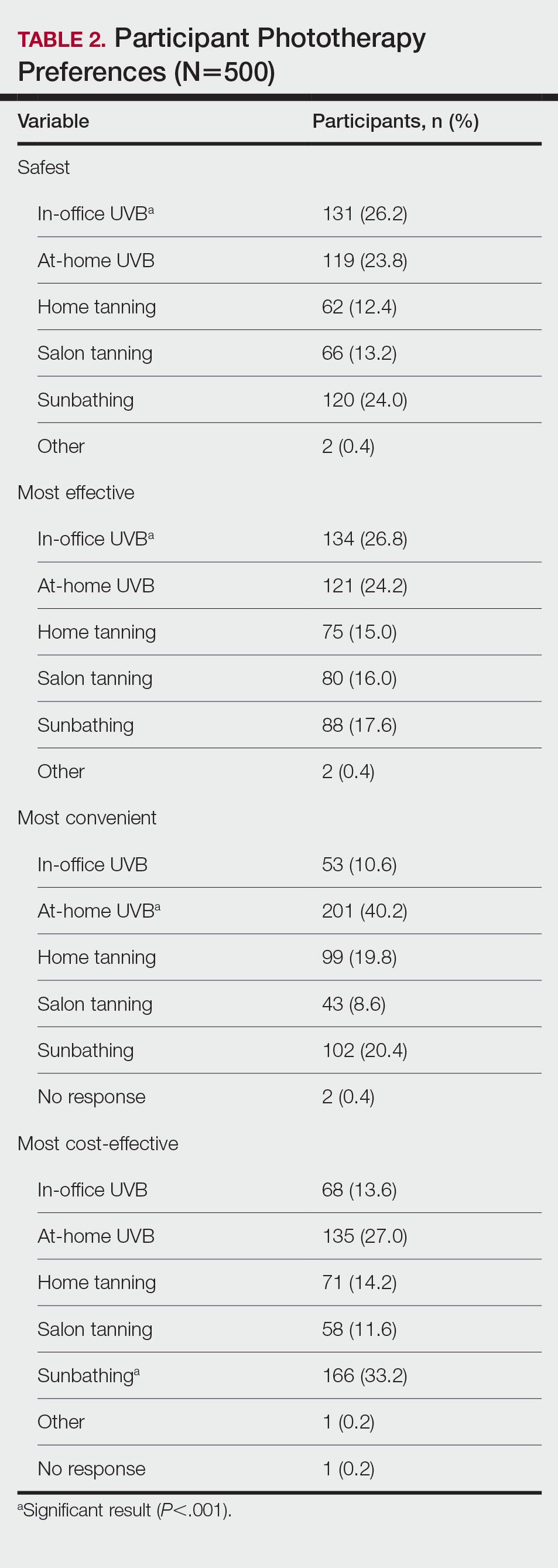

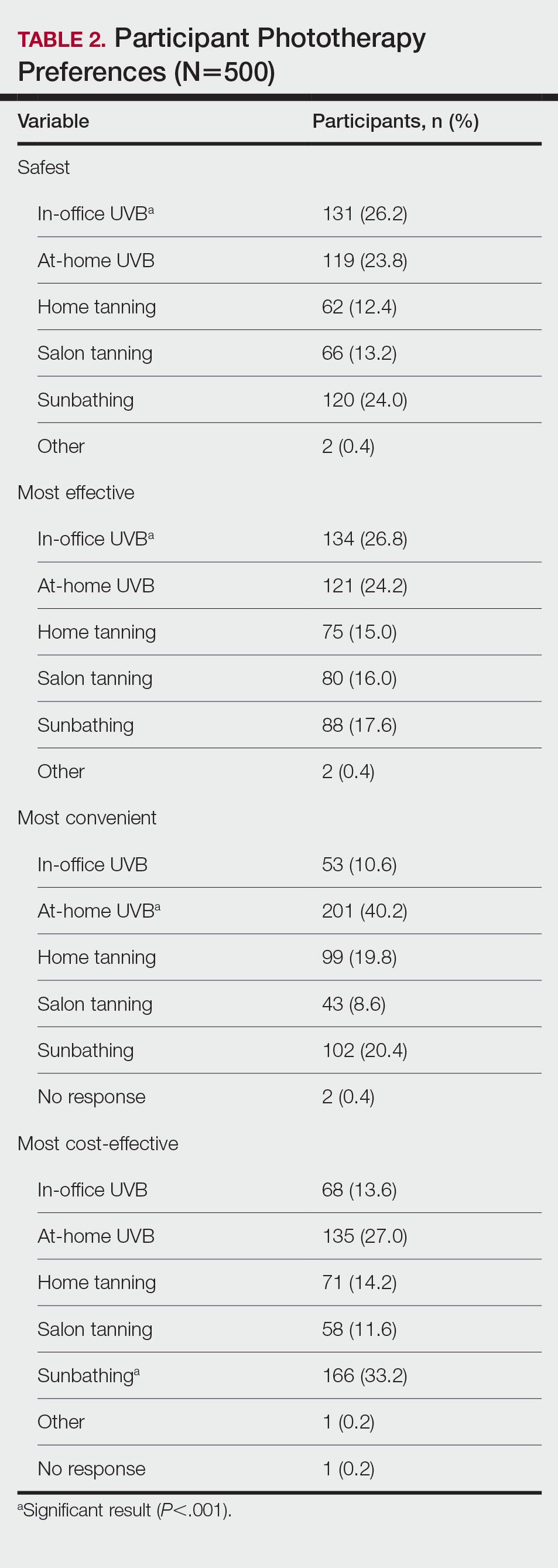

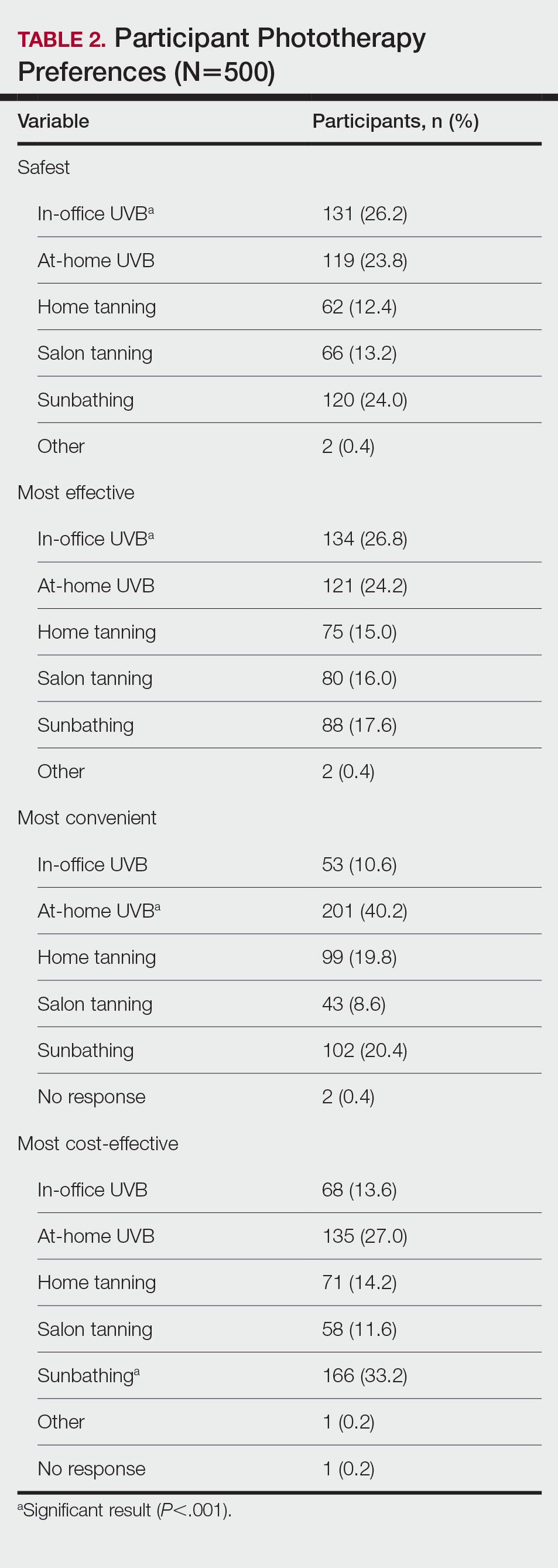

In-office UVB was perceived to be safest (P<.001) and most efficacious (P<.001). Meanwhile, at-home UVB was selected as most convenient (P<.001). Lastly, sunbathing was determined to be most cost-effective (P<.001)(Table 2). Cost-effectiveness had a relationship (P<.001) with the participant’s insurance, as those with private insurance were more likely to select at-home UVB, whereas those with Medicare or Medicaid were more likely to select the tanning options. Additionally, of the54 uninsured participants in the survey, 29 selected sunbathing as the most cost-effective option.

Comment

Phototherapy Treatment—UVB phototherapy at a wavelength of 290 to 320 nm (311–313 nm for narrowband UVB) is used to treat various dermatoses, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. UVB alters skin cytokines, induces apoptosis, promotes immunosuppression, causes DNA damage, and decreases the proliferation of dendritic cells and other cells of the innate immune system.1 In-office and at-home UV therapies make use of UVB wavelengths for treatment, while tanning and sunbathing contain not only UVB but also potentially harmful UVA rays. The wavelengths for indoor tanning devices include UVB at 280 to 315 nm and UVA at 315 to 400 nm, which are similar to those of the sun but with a different ratio of UVB to UVA and more intense total UV.2 When in-office and at-home UVB options are not available, various forms of tanning such as salon tanning and sunbathing may be alternatives that are widely used.3 One of the main reasons patients consider alternative phototherapy options is cost, as 1 in-office UVB treatment may cost $140, but a month of unlimited tanning may cost $30 or perhaps nothing if a patient has a gym membership with access to a tanning bed. Lack of insurance benefits covering phototherapy can exacerbate cost burden.4 However, tanning beds are associated with an increased risk for melanoma and nonmelanoma cancers.5,6 Additionally, all forms of phototherapy are associated with photoaging, but it is more intense with tanning and heliotherapy because of the presence of UVA, which penetrates deeper into the dermis.7 Meanwhile, for those who choose UVB therapy, deciding between an in-office and at-home UVB treatment could be a matter of convenience, as patients must consider long trips to the physician’s office; insurance status, as some insurances may not cover at-home UVB; or efficacy, which might be influenced by the presence of a physician or other medical staff. In many cases, patients may not be informed that at-home UVB is an option.

Patient Preferences—At-home UVB therapy was the most popular option in our study population, with most participants (52.6%) considering using it, and 35.9% choosing it as their top choice over all other phototherapy options. Safety, cost, and convenience were all found to be related to the option participants would most consider using. Prior analysis between at-home UVB and in-office UVB for the treatment of psoriasis determined that at-home UVB is as safe and cost-effective as in-office UVB without the inconvenience of the patient having to take time out of the week to visit the physician’s office,8,9 making at-home UVB an option dermatologists may strongly consider for patients who value safety, cost, and convenience. Oddly, efficacy was not related to the top preference, despite being the second highest–cited factor (53.2%) for which forms of phototherapy participants would consider using. For insurance coverage, those with Medicaid and Medicare selected the cheaper tanning options with higher-than-expected frequencies. Although problems with insurance were not related to the top preference, insurance status was related, suggesting that preferences are tied to cost. Of note, while the number of dermatologists that accept Medicare has increased in the last few years, there still remains an uneven distribution of phototherapy clinics. As of 2015, there were 19 million individuals who qualified for Medicare without a clinic within driving distance.10 This problem likely also exists for many Medicaid patients who may not qualify for at-home UVB. In this scenario, tanning or heliotherapy may be effective alternatives.

In-Office vs At-Home Options—Although in-office UVB was the option considered safest (26.2%) and most efficacious (26.8%), it was followed closely by at-home UVB in both categories (safest, 23.8%; most efficacious, 24.2%). Meanwhile, at-home UVB (40.2%) was chosen as the most convenient. Some patients consider tanning options over in-office UVB because of the inconvenience of traveling to an appointment.11 Therefore, at-home tanning may be a convenient alternative for these patients.

Considerations—Although our study was limited to an adult population, issues with convenience exist for the pediatric population as well, as children may need to miss multiple days of school each week to be treated in the office. For these pediatric patients, an at-home unit is preferable; however; issues with insurance coverage remain a challenge.12 Increasing insurance coverage of at-home units for the pediatric population therefore would be most prudent. However, when other options have been exhausted, including in-office UVB, tanning and sunbathing may be viable alternatives because of cost and convenience. In our study, sunbathing (33.2%) was considered the most cost-effective, likely because it does not require expensive equipment or a visit to a salon or physician’s office. Sunbathing has been effective in treating some dermatologic conditions, such as atopic dermatitis.13 However, it may only be effective during certain months and at different latitudes—conditions that make UVB sun rays more accessible—particularly when treating psoriasis.14 Furthermore, sunbathing may not be as cost-effective in patients with average-severity psoriasis compared with conventional psoriasis therapy because of the costs of travel to areas with sufficient UVB rays for treatment.15 Additionally, insurance status was related to which option was selected as the most cost-effective, as 29 (53.7%) of 54 uninsured participants chose sunbathing as the most cost-effective option, while only 92 (34.2%) of 269 privately insured patients selected sunbathing. Therefore, insurance status may be a factor for dermatologists to consider if a patient prefers a treatment that is cost-effective. Overall, dermatologists could perhaps consider guiding patients and optimizing their treatment plans based on the factors most important to the patients while understanding that costs and insurance status may ultimately determine the treatment option.

Limitations—Survey participants were recruited on Amazon Mechanical Turk, which could create sampling bias. Furthermore, these participants were representative of the general public and not exclusively patients on phototherapy, therefore representing the opinions of the general public and not those who may require phototherapy. Furthermore, given the nature of the survey, the study was limited to the adult population.

- Totonchy MB, Chiu MW. UV-based therapy. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:399-413, ix-x.

- Nilsen LT, Hannevik M, Veierød MB. Ultraviolet exposure from indoor tanning devices: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:730-740.

- Su J, Pearce DJ, Feldman SR. The role of commercial tanning beds and ultraviolet A light in the treatment of psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2005;16:324-326.

- Anderson KL, Huang KE, Huang WW, et al. Dermatology residents are prescribing tanning bed treatment. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt19h4k7sx.

- Wehner MR, Shive ML, Chren MM, et al. Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e5909.

- Boniol M, Autier P, Boyle P, et al. Cutaneous melanomaattributable to sunbed use: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:E4757.

- Barros NM, Sbroglio LL, Buffara MO, et al. Phototherapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:397-407.

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomized controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:b1542.

- Koek MB, Sigurdsson V, van Weelden H, et al. Cost effectiveness of home ultraviolet B phototherapy for psoriasis: economic evaluation of a randomized controlled trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2010;340:c1490.

- Tan SY, Buzney E, Mostaghimi A. Trends in phototherapy utilization among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, 2000 to 2015. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:672-679.

- Felton S, Adinoff B, Jeon-Slaughter H, et al. The significant health threat from tanning bed use as a self-treatment for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1015-1017.

- Juarez MC, Grossberg AL. Phototherapy in the pediatric population. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:91-108.

- Autio P, Komulainen P, Larni HM. Heliotherapy in atopic dermatitis: a prospective study on climatotherapy using the SCORAD index. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:436-440.

- Krzys´cin JW, Jarosławski J, Rajewska-Wie˛ch B, et al. Effectiveness of heliotherapy for psoriasis clearance in low and mid-latitudinal regions: a theoretical approach. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2012;115:35-41.

- Snellman E, Maljanen T, Aromaa A, et al. Effect of heliotherapy on the cost of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:288-292.

Phototherapy—particularly UVB phototherapy, which utilizes UVB rays of specific wavelengths within the UV spectrum—is indicated for a wide variety of dermatoses. In-office and at-home UVB treatments commonly are used, as are salon tanning and sunbathing. When selecting a form of phototherapy, patients are likely to consider safety, cost, effectiveness, insurance issues, and convenience. Research on patient preferences; the reasons for these preferences; and which options patients perceive to be the safest, most cost-effective, efficacious, and convenient is lacking. We aimed to assess the forms of phototherapy that patients would most consider using; the factors influencing patient preferences; and the forms patients perceived as the safest and most cost-effective, efficacious, and convenient.

Methods

Study Participants—We recruited 500 Amazon Mechanical Turk users who were 18 years or older to complete our REDCap-generated survey. The study was approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board (Winston-Salem, North Carolina).

Evaluation—Participants were asked, “If you were diagnosed with a skin disease that benefited from UV therapy, which of the following forms of UV therapy would you consider choosing?” Participants were instructed to choose all of the forms they would consider using. Available options included in-office UV, at-home UV, home tanning, salon tanning, sunbathing, and other. Participants were asked to select which factors—from safety, cost, effectiveness, issues with insurance, convenience, and other—influenced their decision-making; which form of phototherapy they would most consider along with the factors that influenced their preference for this specific form of phototherapy; and which options they considered to be safest and most cost-effective, efficacious, and convenient. Participants were asked to provide basic sociodemographic information, level of education, income, insurance status (private, Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans Affairs, and uninsured), and distance from the nearest dermatologist.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive and inferential statistics (χ2 test) were used to analyze the data with a significance set at P<.05.

Results

Five hundred participants completed the survey (Table 1).

Factors Influencing Patient Preferences—When asked to select all forms of phototherapy they would consider, 186 (37.2%) participants selected in-office UVB, 263 (52.6%) selected at-home UV, 141 (28.2%) selected home tanning, 117 (23.4%) selected salon tanning, 191 (38.2%) selected sunbathing, and 3 (0.6%) selected other. Participants who selected in-office UVB as an option were more likely to also select salon tanning (P<.012). No other relationship was found between the UVB options and the tanning options. When asked which factors influenced their phototherapy preferences, 295 (59%) selected convenience, 266 (53.2%) selected effectiveness, 220 (44%) selected safety, 218 (43.6%) selected cost, 72 (14.4%) selected issues with insurance, and 4 (0.8%) selected other. Forms of Phototherapy Patients Consider Using—When asked which form of phototherapy they would most consider using, 179 (35.8%) participants selected at-home UVB, 108 (21.6%) selected sunbathing, 92 (18.4%) selected in-office UVB, 62 (12.4%) selected home-tanning, 57 (11.4%) selected salon tanning, 1 (0.2%) selected other, and 1 participant provided no response (P<.001).

Reasons for Using Phototherapy—Of the 179 who selected at-home UVB, 125 (70%) cited convenience as a reason. Of the 108 who selected salon tanning as their top choice, 62 (57%) cited cost as a reason. Convenience (P<.001), cost (P<.001), and safety (P=.023) were related to top preference. Issues with insurance did not have a statistically significant relationship with the top preference. However, participant insurance type was related to top phototherapy preference (P=.021), with privately insured patients more likely to select in-office UVB, whereas those with Medicaid and Medicare were more likely to select home or salon tanning. Efficacy was not related to top preference. Furthermore, age, gender, education, income, and distance from nearest dermatologist were not related to top preference.

In-office UVB was perceived to be safest (P<.001) and most efficacious (P<.001). Meanwhile, at-home UVB was selected as most convenient (P<.001). Lastly, sunbathing was determined to be most cost-effective (P<.001)(Table 2). Cost-effectiveness had a relationship (P<.001) with the participant’s insurance, as those with private insurance were more likely to select at-home UVB, whereas those with Medicare or Medicaid were more likely to select the tanning options. Additionally, of the54 uninsured participants in the survey, 29 selected sunbathing as the most cost-effective option.

Comment

Phototherapy Treatment—UVB phototherapy at a wavelength of 290 to 320 nm (311–313 nm for narrowband UVB) is used to treat various dermatoses, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. UVB alters skin cytokines, induces apoptosis, promotes immunosuppression, causes DNA damage, and decreases the proliferation of dendritic cells and other cells of the innate immune system.1 In-office and at-home UV therapies make use of UVB wavelengths for treatment, while tanning and sunbathing contain not only UVB but also potentially harmful UVA rays. The wavelengths for indoor tanning devices include UVB at 280 to 315 nm and UVA at 315 to 400 nm, which are similar to those of the sun but with a different ratio of UVB to UVA and more intense total UV.2 When in-office and at-home UVB options are not available, various forms of tanning such as salon tanning and sunbathing may be alternatives that are widely used.3 One of the main reasons patients consider alternative phototherapy options is cost, as 1 in-office UVB treatment may cost $140, but a month of unlimited tanning may cost $30 or perhaps nothing if a patient has a gym membership with access to a tanning bed. Lack of insurance benefits covering phototherapy can exacerbate cost burden.4 However, tanning beds are associated with an increased risk for melanoma and nonmelanoma cancers.5,6 Additionally, all forms of phototherapy are associated with photoaging, but it is more intense with tanning and heliotherapy because of the presence of UVA, which penetrates deeper into the dermis.7 Meanwhile, for those who choose UVB therapy, deciding between an in-office and at-home UVB treatment could be a matter of convenience, as patients must consider long trips to the physician’s office; insurance status, as some insurances may not cover at-home UVB; or efficacy, which might be influenced by the presence of a physician or other medical staff. In many cases, patients may not be informed that at-home UVB is an option.

Patient Preferences—At-home UVB therapy was the most popular option in our study population, with most participants (52.6%) considering using it, and 35.9% choosing it as their top choice over all other phototherapy options. Safety, cost, and convenience were all found to be related to the option participants would most consider using. Prior analysis between at-home UVB and in-office UVB for the treatment of psoriasis determined that at-home UVB is as safe and cost-effective as in-office UVB without the inconvenience of the patient having to take time out of the week to visit the physician’s office,8,9 making at-home UVB an option dermatologists may strongly consider for patients who value safety, cost, and convenience. Oddly, efficacy was not related to the top preference, despite being the second highest–cited factor (53.2%) for which forms of phototherapy participants would consider using. For insurance coverage, those with Medicaid and Medicare selected the cheaper tanning options with higher-than-expected frequencies. Although problems with insurance were not related to the top preference, insurance status was related, suggesting that preferences are tied to cost. Of note, while the number of dermatologists that accept Medicare has increased in the last few years, there still remains an uneven distribution of phototherapy clinics. As of 2015, there were 19 million individuals who qualified for Medicare without a clinic within driving distance.10 This problem likely also exists for many Medicaid patients who may not qualify for at-home UVB. In this scenario, tanning or heliotherapy may be effective alternatives.

In-Office vs At-Home Options—Although in-office UVB was the option considered safest (26.2%) and most efficacious (26.8%), it was followed closely by at-home UVB in both categories (safest, 23.8%; most efficacious, 24.2%). Meanwhile, at-home UVB (40.2%) was chosen as the most convenient. Some patients consider tanning options over in-office UVB because of the inconvenience of traveling to an appointment.11 Therefore, at-home tanning may be a convenient alternative for these patients.

Considerations—Although our study was limited to an adult population, issues with convenience exist for the pediatric population as well, as children may need to miss multiple days of school each week to be treated in the office. For these pediatric patients, an at-home unit is preferable; however; issues with insurance coverage remain a challenge.12 Increasing insurance coverage of at-home units for the pediatric population therefore would be most prudent. However, when other options have been exhausted, including in-office UVB, tanning and sunbathing may be viable alternatives because of cost and convenience. In our study, sunbathing (33.2%) was considered the most cost-effective, likely because it does not require expensive equipment or a visit to a salon or physician’s office. Sunbathing has been effective in treating some dermatologic conditions, such as atopic dermatitis.13 However, it may only be effective during certain months and at different latitudes—conditions that make UVB sun rays more accessible—particularly when treating psoriasis.14 Furthermore, sunbathing may not be as cost-effective in patients with average-severity psoriasis compared with conventional psoriasis therapy because of the costs of travel to areas with sufficient UVB rays for treatment.15 Additionally, insurance status was related to which option was selected as the most cost-effective, as 29 (53.7%) of 54 uninsured participants chose sunbathing as the most cost-effective option, while only 92 (34.2%) of 269 privately insured patients selected sunbathing. Therefore, insurance status may be a factor for dermatologists to consider if a patient prefers a treatment that is cost-effective. Overall, dermatologists could perhaps consider guiding patients and optimizing their treatment plans based on the factors most important to the patients while understanding that costs and insurance status may ultimately determine the treatment option.

Limitations—Survey participants were recruited on Amazon Mechanical Turk, which could create sampling bias. Furthermore, these participants were representative of the general public and not exclusively patients on phototherapy, therefore representing the opinions of the general public and not those who may require phototherapy. Furthermore, given the nature of the survey, the study was limited to the adult population.

Phototherapy—particularly UVB phototherapy, which utilizes UVB rays of specific wavelengths within the UV spectrum—is indicated for a wide variety of dermatoses. In-office and at-home UVB treatments commonly are used, as are salon tanning and sunbathing. When selecting a form of phototherapy, patients are likely to consider safety, cost, effectiveness, insurance issues, and convenience. Research on patient preferences; the reasons for these preferences; and which options patients perceive to be the safest, most cost-effective, efficacious, and convenient is lacking. We aimed to assess the forms of phototherapy that patients would most consider using; the factors influencing patient preferences; and the forms patients perceived as the safest and most cost-effective, efficacious, and convenient.

Methods

Study Participants—We recruited 500 Amazon Mechanical Turk users who were 18 years or older to complete our REDCap-generated survey. The study was approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board (Winston-Salem, North Carolina).

Evaluation—Participants were asked, “If you were diagnosed with a skin disease that benefited from UV therapy, which of the following forms of UV therapy would you consider choosing?” Participants were instructed to choose all of the forms they would consider using. Available options included in-office UV, at-home UV, home tanning, salon tanning, sunbathing, and other. Participants were asked to select which factors—from safety, cost, effectiveness, issues with insurance, convenience, and other—influenced their decision-making; which form of phototherapy they would most consider along with the factors that influenced their preference for this specific form of phototherapy; and which options they considered to be safest and most cost-effective, efficacious, and convenient. Participants were asked to provide basic sociodemographic information, level of education, income, insurance status (private, Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans Affairs, and uninsured), and distance from the nearest dermatologist.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive and inferential statistics (χ2 test) were used to analyze the data with a significance set at P<.05.

Results

Five hundred participants completed the survey (Table 1).

Factors Influencing Patient Preferences—When asked to select all forms of phototherapy they would consider, 186 (37.2%) participants selected in-office UVB, 263 (52.6%) selected at-home UV, 141 (28.2%) selected home tanning, 117 (23.4%) selected salon tanning, 191 (38.2%) selected sunbathing, and 3 (0.6%) selected other. Participants who selected in-office UVB as an option were more likely to also select salon tanning (P<.012). No other relationship was found between the UVB options and the tanning options. When asked which factors influenced their phototherapy preferences, 295 (59%) selected convenience, 266 (53.2%) selected effectiveness, 220 (44%) selected safety, 218 (43.6%) selected cost, 72 (14.4%) selected issues with insurance, and 4 (0.8%) selected other. Forms of Phototherapy Patients Consider Using—When asked which form of phototherapy they would most consider using, 179 (35.8%) participants selected at-home UVB, 108 (21.6%) selected sunbathing, 92 (18.4%) selected in-office UVB, 62 (12.4%) selected home-tanning, 57 (11.4%) selected salon tanning, 1 (0.2%) selected other, and 1 participant provided no response (P<.001).

Reasons for Using Phototherapy—Of the 179 who selected at-home UVB, 125 (70%) cited convenience as a reason. Of the 108 who selected salon tanning as their top choice, 62 (57%) cited cost as a reason. Convenience (P<.001), cost (P<.001), and safety (P=.023) were related to top preference. Issues with insurance did not have a statistically significant relationship with the top preference. However, participant insurance type was related to top phototherapy preference (P=.021), with privately insured patients more likely to select in-office UVB, whereas those with Medicaid and Medicare were more likely to select home or salon tanning. Efficacy was not related to top preference. Furthermore, age, gender, education, income, and distance from nearest dermatologist were not related to top preference.

In-office UVB was perceived to be safest (P<.001) and most efficacious (P<.001). Meanwhile, at-home UVB was selected as most convenient (P<.001). Lastly, sunbathing was determined to be most cost-effective (P<.001)(Table 2). Cost-effectiveness had a relationship (P<.001) with the participant’s insurance, as those with private insurance were more likely to select at-home UVB, whereas those with Medicare or Medicaid were more likely to select the tanning options. Additionally, of the54 uninsured participants in the survey, 29 selected sunbathing as the most cost-effective option.

Comment

Phototherapy Treatment—UVB phototherapy at a wavelength of 290 to 320 nm (311–313 nm for narrowband UVB) is used to treat various dermatoses, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. UVB alters skin cytokines, induces apoptosis, promotes immunosuppression, causes DNA damage, and decreases the proliferation of dendritic cells and other cells of the innate immune system.1 In-office and at-home UV therapies make use of UVB wavelengths for treatment, while tanning and sunbathing contain not only UVB but also potentially harmful UVA rays. The wavelengths for indoor tanning devices include UVB at 280 to 315 nm and UVA at 315 to 400 nm, which are similar to those of the sun but with a different ratio of UVB to UVA and more intense total UV.2 When in-office and at-home UVB options are not available, various forms of tanning such as salon tanning and sunbathing may be alternatives that are widely used.3 One of the main reasons patients consider alternative phototherapy options is cost, as 1 in-office UVB treatment may cost $140, but a month of unlimited tanning may cost $30 or perhaps nothing if a patient has a gym membership with access to a tanning bed. Lack of insurance benefits covering phototherapy can exacerbate cost burden.4 However, tanning beds are associated with an increased risk for melanoma and nonmelanoma cancers.5,6 Additionally, all forms of phototherapy are associated with photoaging, but it is more intense with tanning and heliotherapy because of the presence of UVA, which penetrates deeper into the dermis.7 Meanwhile, for those who choose UVB therapy, deciding between an in-office and at-home UVB treatment could be a matter of convenience, as patients must consider long trips to the physician’s office; insurance status, as some insurances may not cover at-home UVB; or efficacy, which might be influenced by the presence of a physician or other medical staff. In many cases, patients may not be informed that at-home UVB is an option.

Patient Preferences—At-home UVB therapy was the most popular option in our study population, with most participants (52.6%) considering using it, and 35.9% choosing it as their top choice over all other phototherapy options. Safety, cost, and convenience were all found to be related to the option participants would most consider using. Prior analysis between at-home UVB and in-office UVB for the treatment of psoriasis determined that at-home UVB is as safe and cost-effective as in-office UVB without the inconvenience of the patient having to take time out of the week to visit the physician’s office,8,9 making at-home UVB an option dermatologists may strongly consider for patients who value safety, cost, and convenience. Oddly, efficacy was not related to the top preference, despite being the second highest–cited factor (53.2%) for which forms of phototherapy participants would consider using. For insurance coverage, those with Medicaid and Medicare selected the cheaper tanning options with higher-than-expected frequencies. Although problems with insurance were not related to the top preference, insurance status was related, suggesting that preferences are tied to cost. Of note, while the number of dermatologists that accept Medicare has increased in the last few years, there still remains an uneven distribution of phototherapy clinics. As of 2015, there were 19 million individuals who qualified for Medicare without a clinic within driving distance.10 This problem likely also exists for many Medicaid patients who may not qualify for at-home UVB. In this scenario, tanning or heliotherapy may be effective alternatives.

In-Office vs At-Home Options—Although in-office UVB was the option considered safest (26.2%) and most efficacious (26.8%), it was followed closely by at-home UVB in both categories (safest, 23.8%; most efficacious, 24.2%). Meanwhile, at-home UVB (40.2%) was chosen as the most convenient. Some patients consider tanning options over in-office UVB because of the inconvenience of traveling to an appointment.11 Therefore, at-home tanning may be a convenient alternative for these patients.

Considerations—Although our study was limited to an adult population, issues with convenience exist for the pediatric population as well, as children may need to miss multiple days of school each week to be treated in the office. For these pediatric patients, an at-home unit is preferable; however; issues with insurance coverage remain a challenge.12 Increasing insurance coverage of at-home units for the pediatric population therefore would be most prudent. However, when other options have been exhausted, including in-office UVB, tanning and sunbathing may be viable alternatives because of cost and convenience. In our study, sunbathing (33.2%) was considered the most cost-effective, likely because it does not require expensive equipment or a visit to a salon or physician’s office. Sunbathing has been effective in treating some dermatologic conditions, such as atopic dermatitis.13 However, it may only be effective during certain months and at different latitudes—conditions that make UVB sun rays more accessible—particularly when treating psoriasis.14 Furthermore, sunbathing may not be as cost-effective in patients with average-severity psoriasis compared with conventional psoriasis therapy because of the costs of travel to areas with sufficient UVB rays for treatment.15 Additionally, insurance status was related to which option was selected as the most cost-effective, as 29 (53.7%) of 54 uninsured participants chose sunbathing as the most cost-effective option, while only 92 (34.2%) of 269 privately insured patients selected sunbathing. Therefore, insurance status may be a factor for dermatologists to consider if a patient prefers a treatment that is cost-effective. Overall, dermatologists could perhaps consider guiding patients and optimizing their treatment plans based on the factors most important to the patients while understanding that costs and insurance status may ultimately determine the treatment option.

Limitations—Survey participants were recruited on Amazon Mechanical Turk, which could create sampling bias. Furthermore, these participants were representative of the general public and not exclusively patients on phototherapy, therefore representing the opinions of the general public and not those who may require phototherapy. Furthermore, given the nature of the survey, the study was limited to the adult population.

- Totonchy MB, Chiu MW. UV-based therapy. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:399-413, ix-x.

- Nilsen LT, Hannevik M, Veierød MB. Ultraviolet exposure from indoor tanning devices: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:730-740.

- Su J, Pearce DJ, Feldman SR. The role of commercial tanning beds and ultraviolet A light in the treatment of psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2005;16:324-326.

- Anderson KL, Huang KE, Huang WW, et al. Dermatology residents are prescribing tanning bed treatment. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt19h4k7sx.

- Wehner MR, Shive ML, Chren MM, et al. Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e5909.

- Boniol M, Autier P, Boyle P, et al. Cutaneous melanomaattributable to sunbed use: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:E4757.

- Barros NM, Sbroglio LL, Buffara MO, et al. Phototherapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:397-407.

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomized controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:b1542.

- Koek MB, Sigurdsson V, van Weelden H, et al. Cost effectiveness of home ultraviolet B phototherapy for psoriasis: economic evaluation of a randomized controlled trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2010;340:c1490.

- Tan SY, Buzney E, Mostaghimi A. Trends in phototherapy utilization among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, 2000 to 2015. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:672-679.

- Felton S, Adinoff B, Jeon-Slaughter H, et al. The significant health threat from tanning bed use as a self-treatment for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1015-1017.

- Juarez MC, Grossberg AL. Phototherapy in the pediatric population. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:91-108.

- Autio P, Komulainen P, Larni HM. Heliotherapy in atopic dermatitis: a prospective study on climatotherapy using the SCORAD index. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:436-440.

- Krzys´cin JW, Jarosławski J, Rajewska-Wie˛ch B, et al. Effectiveness of heliotherapy for psoriasis clearance in low and mid-latitudinal regions: a theoretical approach. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2012;115:35-41.

- Snellman E, Maljanen T, Aromaa A, et al. Effect of heliotherapy on the cost of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:288-292.

- Totonchy MB, Chiu MW. UV-based therapy. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:399-413, ix-x.

- Nilsen LT, Hannevik M, Veierød MB. Ultraviolet exposure from indoor tanning devices: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:730-740.

- Su J, Pearce DJ, Feldman SR. The role of commercial tanning beds and ultraviolet A light in the treatment of psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2005;16:324-326.

- Anderson KL, Huang KE, Huang WW, et al. Dermatology residents are prescribing tanning bed treatment. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt19h4k7sx.

- Wehner MR, Shive ML, Chren MM, et al. Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e5909.

- Boniol M, Autier P, Boyle P, et al. Cutaneous melanomaattributable to sunbed use: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:E4757.

- Barros NM, Sbroglio LL, Buffara MO, et al. Phototherapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:397-407.

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomized controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:b1542.

- Koek MB, Sigurdsson V, van Weelden H, et al. Cost effectiveness of home ultraviolet B phototherapy for psoriasis: economic evaluation of a randomized controlled trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2010;340:c1490.

- Tan SY, Buzney E, Mostaghimi A. Trends in phototherapy utilization among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, 2000 to 2015. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:672-679.

- Felton S, Adinoff B, Jeon-Slaughter H, et al. The significant health threat from tanning bed use as a self-treatment for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1015-1017.

- Juarez MC, Grossberg AL. Phototherapy in the pediatric population. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:91-108.

- Autio P, Komulainen P, Larni HM. Heliotherapy in atopic dermatitis: a prospective study on climatotherapy using the SCORAD index. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:436-440.

- Krzys´cin JW, Jarosławski J, Rajewska-Wie˛ch B, et al. Effectiveness of heliotherapy for psoriasis clearance in low and mid-latitudinal regions: a theoretical approach. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2012;115:35-41.

- Snellman E, Maljanen T, Aromaa A, et al. Effect of heliotherapy on the cost of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:288-292.

Practice Points

- Patients have different priorities when selecting phototherapy, including safety, costs, effectiveness, insurance issues, and convenience.

- By offering and educating patients on all forms of phototherapy, dermatologists may help guide patients to their optimal treatment plan according to patient priorities.

Views and Beliefs of Vitiligo Patients in Online Discussion Forums: A Qualitative Study

Vitiligo is a chronic dermatologic condition that negatively affects quality of life (QOL), with substantial burden on the psychosocial well-being of patients.1 There is no cure, and current treatment modalities are aimed at controlling the chronic relapsing condition.1-3 Despite topical and cosmetic treatments for stabilization and repigmentation, vitiligo remains unpredictable.3

All genders, races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic classes are equally affected.4 The underlying etiology of vitiligo remains unknown to a great extent and is more poorly understood by the general public compared with other skin diseases (eg, acne).5 Patients with vitiligo experience social withdrawal, decreased sense of self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation.5,6 Stigmatization has the greatest impact on QOL, with strong correlations between avoidance behaviors and lesion concealment.6-8 Although the condition is especially disfiguring for darker skin types, lighter skin types also are substantially affected, with similar overall self-reported stress.6,7

Individuals with chronic illnesses such as vitiligo turn to online communities for health information and social support, commiserating with others who have the same condition.9,10 Online forums are platforms for asynchronous peer-to-peer exchange of disease-related information for better management of long-term disease.11 Moreover, of all available internet resources, online forum posts are the most commonly accessed source of information (91%) for patients following visits with their doctors.12

Qualitative research involving chronic skin conditions and the information exchanged in online forums has been conducted for patients with acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis, but not for patients with vitiligo.13-16 Although online questionnaires have been administered to patients with vitiligo, the content within online forums is not well characterized.2,17

The purpose of this qualitative study was to evaluate the online content exchanged by individuals with vitiligo to better understand the general attitudes and help-seeking behaviors in online forums.

Methods

Study Design—This qualitative study sought to investigate health beliefs and messages about vitiligo posted by users in US-based online discussion forums. An interpretive research paradigm was utilized so that all content collected in online forums were the views expressed by individuals.18-20 An integrated approach was used in the development of the coding manual, with pre-established major themes and subthemes as a guiding framework.16,21,22 We adhered to an inductive grounded method by means of de novo line-by-line coding, such that we had flexibility for new subthemes to emerge throughout the duration of the entire coding process.23

Individual posts and subsequent replies embedded within public online forums were used as the collected data source. Google was utilized as the primary search engine to identify forums pertaining to vitiligo, as 80% of US adults with chronic disease report that their inquiries for health information start with Google, Bing, or Yahoo.24 The institutional review board at the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) granted approval of the study (IRB00063073). Online forums were considered “property” of the public domain and were accessible to all, eliminating the need for written informed consent.24-26

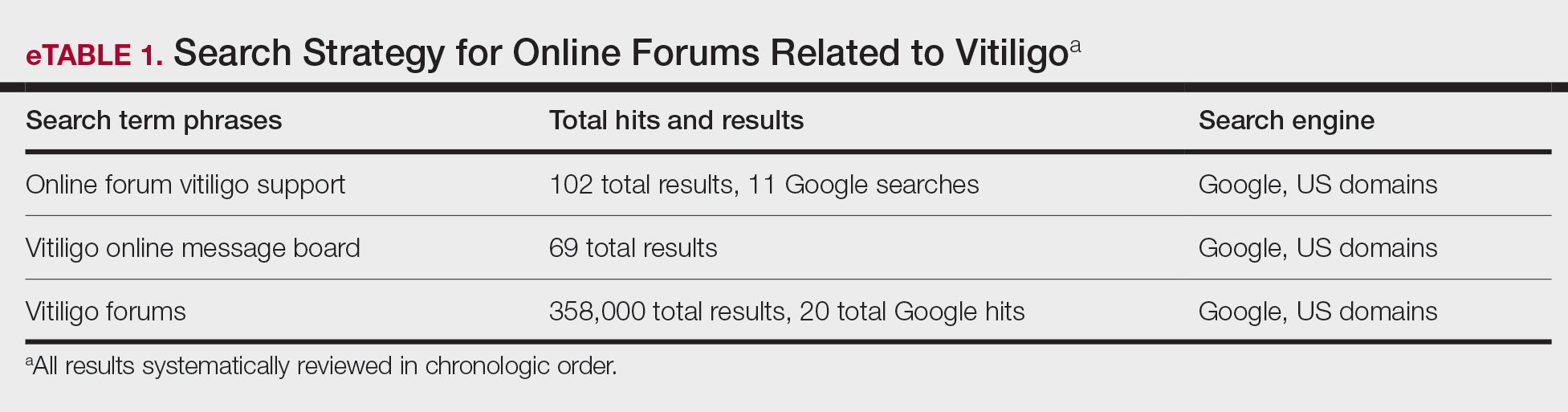

Search Criteria—We conducted our forum search in February 2020 with a systematic approach using predetermined phrases—online forum vitiligo support, vitiligo online message board, and vitiligo forums—which yielded more than 358,171 total results (eTable 1). Threads were identified in chronological order (from newest to oldest) based on how they appeared during each internet search, and all Google results for the respective search phrases were reviewed. Dates of selected threads ranged from 2005 to 2020. Only sites with US domains were included. Posts that either included views and understandings of vitiligo or belonged to a thread that contained a vitiligo discussion were deemed relevant for inclusion. Forums were excluded if registration or means of payment was required to view posts, if there were fewer than 2 user replies to a thread, if threads contained patient photographs, or if no posts had been made in the last 2 years (rendering the thread inactive). No social media platforms, such as Facebook, or formal online platforms, such as MyVitiligoTeam, were included in the search. A no-fee-for-access was chosen for this study, as the majority of those with a chronic condition who encounter a required paywall find the information elsewhere.25

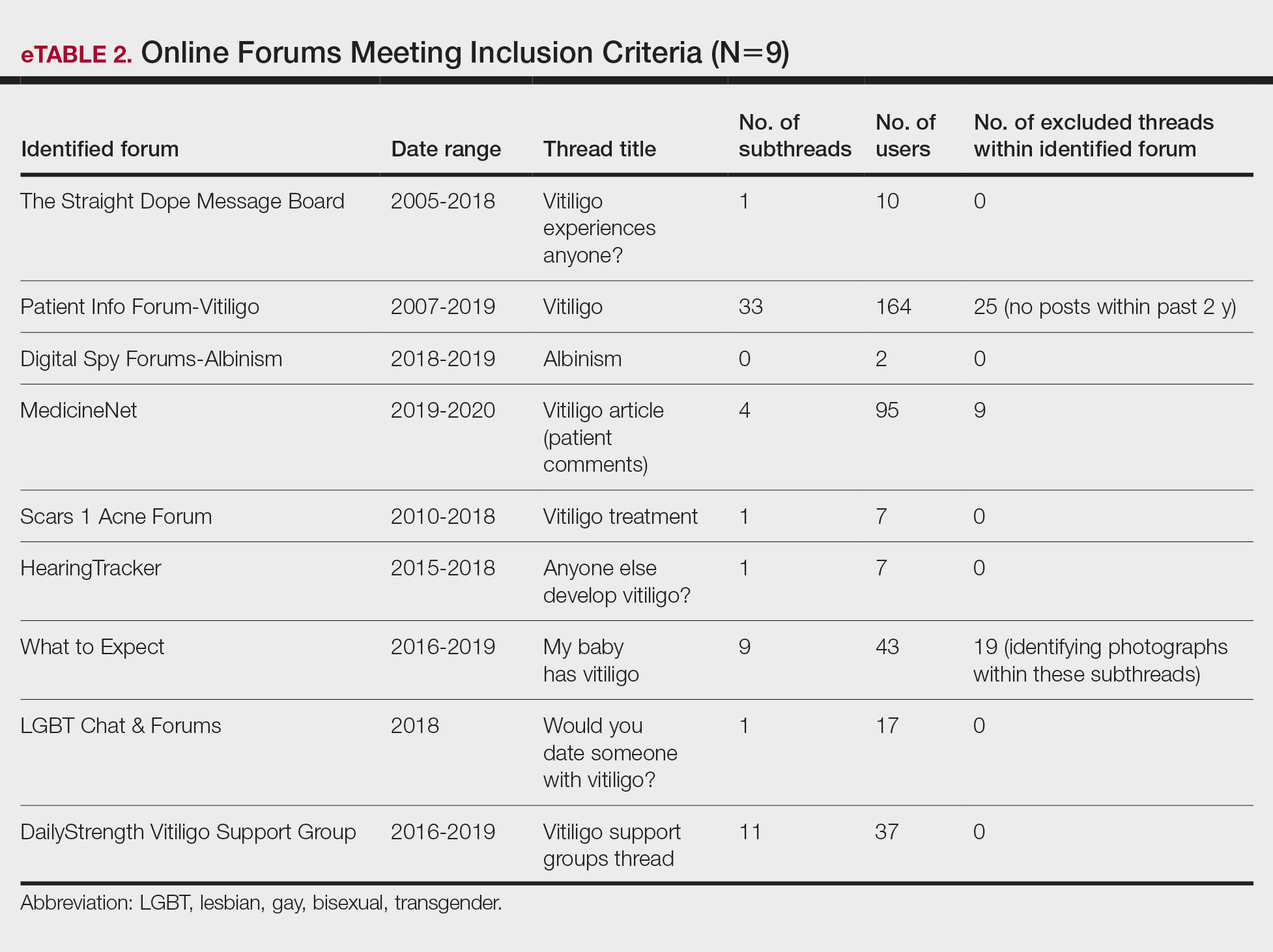

Data Analysis—A total of 39 online forums were deemed relevant to the topic of vitiligo; 9 of them met inclusion criteria (eTable 2). The messages within the forums were copied verbatim into a password-encrypted text document, and usernames in the threads were de-identified, ensuring user confidentiality.

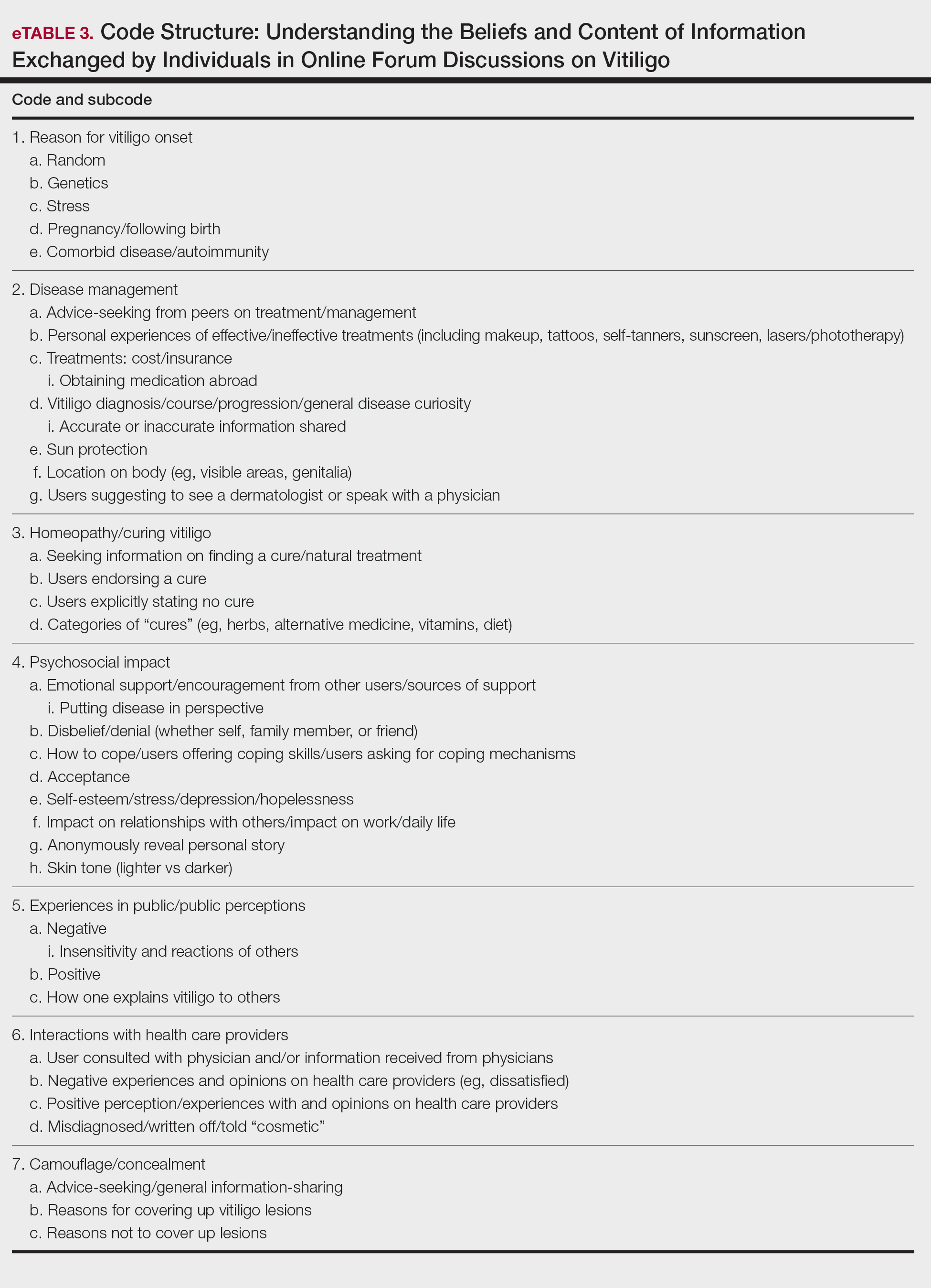

An inductive thematic analysis was utilized to explore the views and beliefs of online forum users discussing vitiligo. One author (M.B.G.) read the extracted message threads, developed an initial codebook, and established a finalized version with the agreement of another author (A.M.B.)(eTable 3). The forums were independently coded (M.B.G. and A.M.B.) in a line-by-line manner according to the codebook. Discrepancies were documented and resolved. Data saturation was adequately achieved, such that no new themes emerged during the iterative coding process. NVivo was used for qualitative analysis.

Results

Nine forums met inclusion criteria, comprising 105 pages of text. There were 61 total discussion threads, with 382 anonymous contributing users. Most users initiated a thread by posting either a question, an advice statement, or a request for help. The psychosocial impact of the disease permeated multiple domains,including personal relationships and daily life. Several threads discussed treatment, including effective camouflage and makeup, as well as peer validation of physician-prescribed treatments, along with threads dedicated to “cures” or homeopathy regimens. In several instances, commercial product endorsement, testimonials, and marketing links were reposted by the same user multiple times.

Inductive thematic analysis highlighted diverse themes and subthemes related to the beliefs and perspectives of users with vitiligo or with relatives or friends with vitiligo: psychosocial impact, disease management and camouflage/concealment, alternative medicine/homeopathy/cures, interactions with the public and health care providers, and skin tone and race. Quotes from individuals were included to demonstrate themes and subthemes.

Psychosocial Impact: QOL, Sources of Support, and Coping—There was a broad range of comments on how patients cope with and view their vitiligo. Some individuals felt vitiligo made them special, and others were at peace with and accepted their condition. In contrast, others reported the disease had devastated them and interfered with relationships. Individuals shared their stories of grief and hardships through childhood and adulthood and their concerns, especially on affected visible areas or the potential for disease progression. Users were vocal about how vitiligo affected their daily routines and lives, sharing how they felt uncomfortable outside the home, no longer engaged in swimming or exposing their legs, and preferred to stay inside instead. Some users adopted a “tough love” approach to coping, sharing how they have learned to either embrace their vitiligo or “live with it.” Some examples include:

“My best advice is go with the flow, vitiligo is not the worst thing that can happen.”

“I hate my life with vitiligo yet really I feel so selfish that there is much worse suffering in the world than a few white patches.”

Other advice was very practical:

“I hope it isn’t vanity that is tearing you apart because that is only skin deep. Make a fashion statement with hats.”

Some users acknowledged and adopted the mantra that vitiligo is not a somatic condition or “physical ailment,” while others emphasized its pervasive psychological burden:

“I still deal with this psychologically . . . You must keep a positive attitude and frame of mind . . . Vitiligo will not kill you, but you do need to stay strong and keep your head up emotionally.”

“I am just really thankful that I have a disease that will not kill me or that has [not] affected me physically at all. I consider myself lucky.”

Disease Management: Treatment, Vitiligo Course, Advice-Seeking, Camouflage—The range of information discussed for treatment was highly variable. There were many accounts in which users advised others to seek professional help, namely that of a dermatologist, for a formal assessment. Many expressed frustrations with treatments and their ineffectiveness, to which the majority of users said to consult with a professional and to remain patient and hopeful/optimistic:

“The best thing to do would be to take an appointment with a dermatologist and have the discoloration checked out. That’s the only way to know whether it is vitiligo or not.”

“My way of dealing with it is to gain control by camouflage.”

“The calming effect of being in control of my vitiligo, whether with concealers, self-tan or anything else, has stopped my feelings of despair.”

Beliefs on Alternative Medicine: Homeopathy and Alternative Regimens—Although some threads started with a post asking for the best treatments, others initiated a discussion by posting “best herbal treatments for cure” or “how to cure my vitiligo,” emphasizing the beliefs and wishes for a cure for vitiligo. Alternative therapies that users endorsed included apple cider vinegar, toothpaste, vitamins, and Ayurvedic treatment, among others. Dietary plans were popular, with users claiming success with dietary alterations in stopping and preventing lesion progression. For example, individuals felt that avoidance of sugar, meat, dairy, and citrus fruits or drinks and consumption of only filtered water were crucial to preventing further lesion spread and resulted in their “cure”:

“Don’t eat chocolate, wine (made of grapes), coffee, or tea if you don’t want to have vitiligo or let it get worse. Take Vitamin B, biotin, and nuts for Vitamin E.”

Other dangerous messages pitted treatments by health professionals against beliefs in homeopathy:

“I feel that vitiligo treatment is all in your diet and vitamins. All that medicine and UV lights is a no-no . . .w ith every medicine there is a side effect. The doctors could be healing your vitiligo and severely damaging you inside and out, and you won’t know until years later.”

There was a minor presence of users advising against homeopathy and the associated misinformation and inaccurate claims on curing vitiligo, though this group was small in comparison to the number of users posting outlandish claims on cure:

“There is no cure . . . It’s where your immune system attacks your skin cells causing loss of pigmentation. The skin that has lost the pigmentation can’t be reversed.”

Interactions With the Public and Health Care Providers—Those with vitiligo encounter unique situations in public and in their daily lives. Many of the accounts shared anecdotal stories on how patients have handled the stigma and discrimination faced:

“I have had to face discrimination at school, public places, college, functions, and every new person I have met has asked me this: ‘how did this happen?’”

Those with vitiligo even stated how they wished others would deal with their condition out in public, hoping that others would directly ask what the lesions were instead of the more hurtful staring. There were many stories in which users said others feel vitiligo was contagious or “dirty” and stressed that the condition is not infectious:

“I refer to myself as ‘camo-man’ and reassure people I come into contact with that it is not contagious.”

“Once I was eating at a restaurant . . . and a little girl said to her mom, ‘Look, Mom, that lady doesn’t wash her arms, look how dirty they are.’ That just broke my heart.”

Skin Tone and Implications—The belief that vitiligo lesions are less dramatic or less anxiety provoking for individuals with lighter skin was noted by users themselves and by health care providers in certain cases. Skin tone and its impact on QOL was confusing and contentious. Some users with fair skin stated their vitiligo was “less of an annoyance” or “less obvious” compared with individuals with darker complexions. Conversely, other accounts of self-reported White users vehemently stressed the anxieties felt by depigmented lesions, despite being “already white at baseline.”

“Was told by my dermatologist (upon diagnosis) that ‘You’re lucky you’re not African American—it shows up on them much worse. You’re so fair, it doesn’t really matter.’ ”

“You didn’t say what race you are. I could imagine it has a bigger impact if you are anything other than White.”

Comment

Patients Looking for Cures—The general attitude within the forums was uplifting and encouraging, with users detailing how they respond to others in public and sharing their personal perspectives. We found a mix of information regarding disease management and treatment of vitiligo. Overall, there was uncertainty about treatments, with individuals expressing concern that their treatments were ineffective or had failed or that better alternatives would be more suitable for their condition. We found many anecdotal endorsements of homeopathic remedies for vitiligo, with users boasting that their disease had not only been cured but had never returned. Some users completely denounced these statements, while other threads seemed to revolve completely around “cure” discussions with no dissenting voices. The number of discussions related to homeopathy was concerning. Furthermore, there often were no moderators within threads to remove cure-related content, whether commercially endorsed or anecdotal. It is plausible that supplements and vitamins recommended by some physicians may be incorrectly interpreted as a “cure” in online discussions. Our findings are consistent with prior reports that forums are a platform to express dissatisfaction with treatment and the need for additional treatment options.15,22

Concern Expressed by Health Care Providers—Prior qualitative research has described how patients with chronic dermatologic conditions believe that health care providers minimize patients’ psychological distress.27,28 We found several accounts in which an individual had explicitly stated their provider had “belittled” the extent and impact of vitiligo when comparing skin phototypes. This suggests either that physicians underestimate the impact of vitiligo on their patients or that physicians are not expressing enough empathic concern about the impact the condition has on those affected.

Cosmetic Aspects of Vitiligo—Few clinical trials have investigated QOL and cosmetic acceptability of treatments as outcome measures.29 We found several instances in which users with vitiligo had reported being dismissed as having a “cosmetic disease,” consistent with other work demonstrating the negative impact on such dismissals.22 Moreover, concealment and camouflage techniques frequently were discussed, demonstrating the relevance of cosmetic management as an important research topic.

Trustworthy Sources of Health Information—Patients still view physicians as trustworthy and a key source of health care information and advice.30-32 Patients with vitiligo who have been directed to reliable information sources often express gratitude22 and want health professionals to remain an important source in their health information-seeking.31 Given the range in information discussed online, it may be valuable to invite patients to share what information they have encountered online.

Our study highlights the conflicting health information and advice shared by users in online forums, complicating an already psychologically burdensome condition. Guiding patients to credible, moderated sites and resources that are accurate, understandable, and easy to access may help dispel the conflicting messages and stories discussed in the online community.

Study Strengths and Limitations—Limitations included reporting bias and reliance on self-reported information on the diagnosis and extent of individuals’ vitiligo. Excluding social media websites and platforms from the data collection is a limitation to comprehensively assessing the topic of internet users with vitiligo. Many social media platforms direct patients and their family members to support groups and therefore may have excluded these particular individuals. Social media platforms were excluded from our research owing to the prerequisite of creating user accounts or registering as an online member. Our inclusion criteria were specific to forums that did not require registering or creating an account and were therefore freely accessible to all internet viewers. There is an inherent lack of context present in online forums, preventing data collection on individuals’ demographics and socioeconomic backgrounds. However, anonymity may have allowed individuals to express their thoughts more freely.

An integrated approach, along with our sampling method of online forums not requiring registration, allows for greater transferability and understanding of the health needs of the general public with vitiligo.

Conclusion

Individuals with vitiligo continue to seek peer psychosocial support for the physical and emotional management of their disease. Counseling those with vitiligo about cosmetic concealment options, homeopathy, and treatment scams remains paramount. Directing patients to evidence-based resources, along with providing structured sources of support, may help to improve the psychosocial burden and QOL experienced by patients with vitiligo. Connecting patients with local and national support groups moderated by physicians, such as the Global Vitiligo Foundation (https://globalvitiligofoundation.org/), may provide benefit to patients with vitiligo.

- Yaghoobi R, Omidian M, Bagherani N. Vitiligo: a review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2011;38:419-431.

- Ezzedine K, Sheth V, Rodrigues M, et al. Vitiligo is not a cosmetic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:883-885.

- Faria AR, Tarlé RG, Dellatorre G, et al. Vitiligo—part 2—classification, histopathology and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:784-790.

- Alkhateeb A, Fain PR, Thody A, et al. Epidemiology of vitiligo and associated autoimmune diseases in Caucasian probands and their families. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:208-214.

- Nguyen CM, Beroukhim K, Danesh MJ, et al. The psychosocial impact of acne, vitiligo, and psoriasis: a review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:383-392.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Grimes PE, Billips M. Childhood vitiligo: clinical spectrum and therapeutic approaches. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ, eds. Vitiligo: A Monograph on the Basic and Clinical Science. Blackwell Science; 2000.

- Sawant NS, Vanjari NA, Khopkar U. Gender differences in depression, coping, stigma, and quality of life in patients of vitiligo. Dermatol Res Pract. 2019;2019:6879412.

- Liu Y, Kornfield R, Shaw BR, et al. When support is needed: social support solicitation and provision in an online alcohol use disorder forum. Digit Health. 2017;3:2055207617704274.

- Health 2.0. The Economist. 2007;384:14.

- Fox S. Peer-to-peer health care. Pew Research Center. February 28, 2011. Accessed December 14, 2021. https://www.pewinternet.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/media/Files/Reports/2011/Pew_P2PHealthcare_2011.pdf

- Li N, Orrange S, Kravitz RL, et al. Reasons for and predictors of patients’ online health information seeking following a medical appointment. Fam Pract. 2014;31:550-556.

- Idriss SZ, Kvedar JC, Watson AJ. The role of online support communities: benefits of expanded social networks to patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:46-51.

- Teasdale EJ, Muller I, Santer M. Carers’ views of topical corticosteroid use in childhood eczema: a qualitative study of online discussion forums. Br J Dermatol 2017;176:1500-1507.

- Santer M, Chandler D, Lown M, et al. Views of oral antibiotics and advice seeking about acne: a qualitative study of online discussion forums. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:751-757.

- Santer M, Burgess H, Yardley L, et al. Experiences of carers managing childhood eczema and their views on its treatment: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:e261-e267.

- Talsania N, Lamb B, Bewley A. Vitiligo is more than skin deep: a survey of members of the Vitiligo Society. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:736-739.

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications, Inc; 1994:105-117.

- Lincoln YS. Emerging criteria for quality in qualitative and interpretive research. Qualitative Inquiry. 2016;1:275-289.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245-1251.

- Teasdale EJ, Muller I, Santer M. Carers’ views of topical corticosteroid use in childhood eczema: a qualitative study of online discussion forums. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1500-1507.

- Teasdale E, Muller I, Sani AA, et al. Views and experiences of seeking information and help for vitiligo: a qualitative study of written accounts. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e018652.

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1758-1772.

- Hewson C, Buchanan T, Brown I, et al. Ethics Guidelines for Internet-mediated Research. The British Psychological Society; 2017.

- Coulson NS. Sharing, supporting and sobriety: a qualitative analysis of messages posted to alcohol-related online discussion forums in the United Kingdom. J Subst Use. 2014;19:176-180.

- Attard A, Coulson NS. A thematic analysis of patient communication in Parkinson’s disease online support group discussion forums. Comput Hum Behav. 2012;28:500-506.

- Nelson PA, Chew-Graham CA, Griffiths CE, et al. Recognition of need in health care consultations: a qualitative study of people with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:354-361.

- Gore C, Johnson RJ, Caress AL, et al. The information needs and preferred roles in treatment decision-making of parents caring for infants with atopic dermatitis: a qualitative study. Allergy. 2005;60:938-943.

- Eleftheriadou V, Thomas KS, Whitton ME, et al. Which outcomes should we measure in vitiligo? Results of a systematic review and a survey among patients and clinicians on outcomes in vitiligo trials. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:804-814.

- Tan SS, Goonawardene N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e9.

- Sillence E, Briggs P, Harris PR, et al. How do patients evaluate and make use of online health information? Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1853-1862.

- Hay MC, Cadigan RJ, Khanna D, et al. Prepared patients: internet information seeking by new rheumatology patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:575-582.

Vitiligo is a chronic dermatologic condition that negatively affects quality of life (QOL), with substantial burden on the psychosocial well-being of patients.1 There is no cure, and current treatment modalities are aimed at controlling the chronic relapsing condition.1-3 Despite topical and cosmetic treatments for stabilization and repigmentation, vitiligo remains unpredictable.3

All genders, races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic classes are equally affected.4 The underlying etiology of vitiligo remains unknown to a great extent and is more poorly understood by the general public compared with other skin diseases (eg, acne).5 Patients with vitiligo experience social withdrawal, decreased sense of self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation.5,6 Stigmatization has the greatest impact on QOL, with strong correlations between avoidance behaviors and lesion concealment.6-8 Although the condition is especially disfiguring for darker skin types, lighter skin types also are substantially affected, with similar overall self-reported stress.6,7

Individuals with chronic illnesses such as vitiligo turn to online communities for health information and social support, commiserating with others who have the same condition.9,10 Online forums are platforms for asynchronous peer-to-peer exchange of disease-related information for better management of long-term disease.11 Moreover, of all available internet resources, online forum posts are the most commonly accessed source of information (91%) for patients following visits with their doctors.12

Qualitative research involving chronic skin conditions and the information exchanged in online forums has been conducted for patients with acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis, but not for patients with vitiligo.13-16 Although online questionnaires have been administered to patients with vitiligo, the content within online forums is not well characterized.2,17

The purpose of this qualitative study was to evaluate the online content exchanged by individuals with vitiligo to better understand the general attitudes and help-seeking behaviors in online forums.

Methods

Study Design—This qualitative study sought to investigate health beliefs and messages about vitiligo posted by users in US-based online discussion forums. An interpretive research paradigm was utilized so that all content collected in online forums were the views expressed by individuals.18-20 An integrated approach was used in the development of the coding manual, with pre-established major themes and subthemes as a guiding framework.16,21,22 We adhered to an inductive grounded method by means of de novo line-by-line coding, such that we had flexibility for new subthemes to emerge throughout the duration of the entire coding process.23

Individual posts and subsequent replies embedded within public online forums were used as the collected data source. Google was utilized as the primary search engine to identify forums pertaining to vitiligo, as 80% of US adults with chronic disease report that their inquiries for health information start with Google, Bing, or Yahoo.24 The institutional review board at the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) granted approval of the study (IRB00063073). Online forums were considered “property” of the public domain and were accessible to all, eliminating the need for written informed consent.24-26

Search Criteria—We conducted our forum search in February 2020 with a systematic approach using predetermined phrases—online forum vitiligo support, vitiligo online message board, and vitiligo forums—which yielded more than 358,171 total results (eTable 1). Threads were identified in chronological order (from newest to oldest) based on how they appeared during each internet search, and all Google results for the respective search phrases were reviewed. Dates of selected threads ranged from 2005 to 2020. Only sites with US domains were included. Posts that either included views and understandings of vitiligo or belonged to a thread that contained a vitiligo discussion were deemed relevant for inclusion. Forums were excluded if registration or means of payment was required to view posts, if there were fewer than 2 user replies to a thread, if threads contained patient photographs, or if no posts had been made in the last 2 years (rendering the thread inactive). No social media platforms, such as Facebook, or formal online platforms, such as MyVitiligoTeam, were included in the search. A no-fee-for-access was chosen for this study, as the majority of those with a chronic condition who encounter a required paywall find the information elsewhere.25

Data Analysis—A total of 39 online forums were deemed relevant to the topic of vitiligo; 9 of them met inclusion criteria (eTable 2). The messages within the forums were copied verbatim into a password-encrypted text document, and usernames in the threads were de-identified, ensuring user confidentiality.

An inductive thematic analysis was utilized to explore the views and beliefs of online forum users discussing vitiligo. One author (M.B.G.) read the extracted message threads, developed an initial codebook, and established a finalized version with the agreement of another author (A.M.B.)(eTable 3). The forums were independently coded (M.B.G. and A.M.B.) in a line-by-line manner according to the codebook. Discrepancies were documented and resolved. Data saturation was adequately achieved, such that no new themes emerged during the iterative coding process. NVivo was used for qualitative analysis.

Results

Nine forums met inclusion criteria, comprising 105 pages of text. There were 61 total discussion threads, with 382 anonymous contributing users. Most users initiated a thread by posting either a question, an advice statement, or a request for help. The psychosocial impact of the disease permeated multiple domains,including personal relationships and daily life. Several threads discussed treatment, including effective camouflage and makeup, as well as peer validation of physician-prescribed treatments, along with threads dedicated to “cures” or homeopathy regimens. In several instances, commercial product endorsement, testimonials, and marketing links were reposted by the same user multiple times.

Inductive thematic analysis highlighted diverse themes and subthemes related to the beliefs and perspectives of users with vitiligo or with relatives or friends with vitiligo: psychosocial impact, disease management and camouflage/concealment, alternative medicine/homeopathy/cures, interactions with the public and health care providers, and skin tone and race. Quotes from individuals were included to demonstrate themes and subthemes.

Psychosocial Impact: QOL, Sources of Support, and Coping—There was a broad range of comments on how patients cope with and view their vitiligo. Some individuals felt vitiligo made them special, and others were at peace with and accepted their condition. In contrast, others reported the disease had devastated them and interfered with relationships. Individuals shared their stories of grief and hardships through childhood and adulthood and their concerns, especially on affected visible areas or the potential for disease progression. Users were vocal about how vitiligo affected their daily routines and lives, sharing how they felt uncomfortable outside the home, no longer engaged in swimming or exposing their legs, and preferred to stay inside instead. Some users adopted a “tough love” approach to coping, sharing how they have learned to either embrace their vitiligo or “live with it.” Some examples include:

“My best advice is go with the flow, vitiligo is not the worst thing that can happen.”

“I hate my life with vitiligo yet really I feel so selfish that there is much worse suffering in the world than a few white patches.”

Other advice was very practical:

“I hope it isn’t vanity that is tearing you apart because that is only skin deep. Make a fashion statement with hats.”

Some users acknowledged and adopted the mantra that vitiligo is not a somatic condition or “physical ailment,” while others emphasized its pervasive psychological burden:

“I still deal with this psychologically . . . You must keep a positive attitude and frame of mind . . . Vitiligo will not kill you, but you do need to stay strong and keep your head up emotionally.”

“I am just really thankful that I have a disease that will not kill me or that has [not] affected me physically at all. I consider myself lucky.”

Disease Management: Treatment, Vitiligo Course, Advice-Seeking, Camouflage—The range of information discussed for treatment was highly variable. There were many accounts in which users advised others to seek professional help, namely that of a dermatologist, for a formal assessment. Many expressed frustrations with treatments and their ineffectiveness, to which the majority of users said to consult with a professional and to remain patient and hopeful/optimistic:

“The best thing to do would be to take an appointment with a dermatologist and have the discoloration checked out. That’s the only way to know whether it is vitiligo or not.”

“My way of dealing with it is to gain control by camouflage.”

“The calming effect of being in control of my vitiligo, whether with concealers, self-tan or anything else, has stopped my feelings of despair.”

Beliefs on Alternative Medicine: Homeopathy and Alternative Regimens—Although some threads started with a post asking for the best treatments, others initiated a discussion by posting “best herbal treatments for cure” or “how to cure my vitiligo,” emphasizing the beliefs and wishes for a cure for vitiligo. Alternative therapies that users endorsed included apple cider vinegar, toothpaste, vitamins, and Ayurvedic treatment, among others. Dietary plans were popular, with users claiming success with dietary alterations in stopping and preventing lesion progression. For example, individuals felt that avoidance of sugar, meat, dairy, and citrus fruits or drinks and consumption of only filtered water were crucial to preventing further lesion spread and resulted in their “cure”:

“Don’t eat chocolate, wine (made of grapes), coffee, or tea if you don’t want to have vitiligo or let it get worse. Take Vitamin B, biotin, and nuts for Vitamin E.”

Other dangerous messages pitted treatments by health professionals against beliefs in homeopathy:

“I feel that vitiligo treatment is all in your diet and vitamins. All that medicine and UV lights is a no-no . . .w ith every medicine there is a side effect. The doctors could be healing your vitiligo and severely damaging you inside and out, and you won’t know until years later.”

There was a minor presence of users advising against homeopathy and the associated misinformation and inaccurate claims on curing vitiligo, though this group was small in comparison to the number of users posting outlandish claims on cure:

“There is no cure . . . It’s where your immune system attacks your skin cells causing loss of pigmentation. The skin that has lost the pigmentation can’t be reversed.”

Interactions With the Public and Health Care Providers—Those with vitiligo encounter unique situations in public and in their daily lives. Many of the accounts shared anecdotal stories on how patients have handled the stigma and discrimination faced:

“I have had to face discrimination at school, public places, college, functions, and every new person I have met has asked me this: ‘how did this happen?’”

Those with vitiligo even stated how they wished others would deal with their condition out in public, hoping that others would directly ask what the lesions were instead of the more hurtful staring. There were many stories in which users said others feel vitiligo was contagious or “dirty” and stressed that the condition is not infectious:

“I refer to myself as ‘camo-man’ and reassure people I come into contact with that it is not contagious.”

“Once I was eating at a restaurant . . . and a little girl said to her mom, ‘Look, Mom, that lady doesn’t wash her arms, look how dirty they are.’ That just broke my heart.”

Skin Tone and Implications—The belief that vitiligo lesions are less dramatic or less anxiety provoking for individuals with lighter skin was noted by users themselves and by health care providers in certain cases. Skin tone and its impact on QOL was confusing and contentious. Some users with fair skin stated their vitiligo was “less of an annoyance” or “less obvious” compared with individuals with darker complexions. Conversely, other accounts of self-reported White users vehemently stressed the anxieties felt by depigmented lesions, despite being “already white at baseline.”

“Was told by my dermatologist (upon diagnosis) that ‘You’re lucky you’re not African American—it shows up on them much worse. You’re so fair, it doesn’t really matter.’ ”

“You didn’t say what race you are. I could imagine it has a bigger impact if you are anything other than White.”

Comment