User login

Heart on the right may sometimes be ‘right’

A 76-year-old man presented to the emergency department with right-sided exertional chest pain radiating to the right shoulder and arm associated with shortness of breath. His vital signs were normal. On clinical examination, the cardiac apex was palpated on the right side, 9 cm from the midsternal line in the fifth intercostal space.

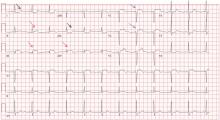

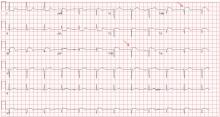

A standard left-sided 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed right-axis deviation and inverted P, QRS, and T waves in leads I and aVL (Figure 1). Although these changes are also seen when the right and left arm electrode wires are transposed, the precordial lead morphology in such a situation would usually be normal. In our patient, the precordial leads showed the absence or even slight reversal of R-wave progression, a feature indicative of dextrocardia.1,2

In patients with dextrocardia, right-sided hookup of the electrodes is usually necessary for proper interpretation of the ECG. When this was done in our patient, the ECG showed a normal cardiac axis, a negative QRS complex in lead aVR, a positive P wave and other complexes in lead I, and normal R-wave progression in the precordial leads—findings suggestive of dextrocardia (Figure 2).

Chest radiography showed a right-sided cardiac silhouette (Figure 3), and computed tomography of the abdomen (Figure 4) revealed the liver positioned on the left side and the spleen on the right, confirming the diagnosis of situs inversus totalis. The ECG showed dextrocardia, but no other abnormalities. The patient eventually underwent coronary angiography, which showed nonobstructive coronary artery disease.

DEXTROCARDIA, OTHER CONGENITAL CARDIOVASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

Dextrocardia was first described in early 17th century.1 Situs solitus is the normal position of the heart and viscera, whereas situs inversus is a mirror-image anatomic arrangement of the organs. Situs inversus with dextrocardia, also called situs inversus totalis, is a rare condition (with a prevalence of 1 in 8,000) in which the heart and descending aorta are on the right and the thoracic and abdominal viscera are usually mirror images of the normal morphology.1,3,4 A mirror-image sinus node lies at the junction of the left superior vena cava and the left-sided (morphologic right) atrium.1 People with situs inversus with dextrocardia are usually asymptomatic and have a normal life expectancy.1,2 Situs inversus with levocardia is a rare condition in which the heart is in the normal position but the viscera are in the dextro-position. This anomaly has a prevalence of 1 in 22,000.5

Atrial situs almost always corresponds to visceral situs. However, when the alignment of the atria and viscera is inconsistent and situs cannot be determined clearly because of the malpositioning of organs, the condition is called “situs ambiguous.” This is very rare, with a prevalence of 1 in 40,000.6

Risk factors

The cause of congenital cardiovascular malformations such as these is not known, but risk factors include positive family history, maternal diabetes, and cocaine use in the first trimester.7

The prevalence of congenital heart disease in patients with situs inversus with dextrocardia is low and ranges from 2% to 5%. This is in contrast to situs solitus with dextrocardia (isolated dextrocardia), which is almost always associated with cardiovascular anomalies.2,4 Kartagener syndrome—the triad of situs inversus, sinusitis, and bronchiectasis—occurs in 25% of people with situs inversus with dextrocardia.4 Situs inversus with levocardia is also frequently associated with cardiac anomalies.5

The major features of dextrocardia on ECG are:

- Negative P wave, QRS complex, and T wave in lead I

- Positive QRS complex in aVR

- Right-axis deviation

- Reversal of R-wave progression in the precordial leads.

Ventricular activation and repolarization are reversed, resulting in a negative QRS complex and an inverted T wave in lead I. The absence of R-wave progression in the precordial leads helps differentiate mirror-image dextrocardia from erroneously reversed limb-electrode placement, which shows normal R-wave progression from V1 to V6 while showing similar features to those seen in dextrocardia in the limb leads.2 In right-sided hookup, the limb electrodes are reversed, and the chest electrodes are recorded from the right precordium.

CORONARY INTERVENTIONS REQUIRE SPECIAL CONSIDERATION

In patients with dextrocardia, coronary interventions can be challenging because of the mirror-image position of the coronary ostia and the aortic arch.8 These patients also need careful imaging, consideration of other associated congenital cardiac abnormalities, and detailed planning before cardiac surgery, including coronary artery bypass grafting.9

Patients with dextrocardia may present with cardiac symptoms localized to the right side of the body and have confusing clinical and diagnostic findings. Keeping dextrocardia and other such anomalies in mind can prevent delay in appropriately directed interventions. In a patient such as ours, the heart on the right side of the chest may indeed be “right.” Still, diagnostic tests to look for disorders encountered with dextrocardia may be necessary.

- Perloff JK. The cardiac malpositions. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108:1352–1361.

- Tanawuttiwat T, Vasaiwala S, Dia M. ECG image of the month. Mirror mirror. Am J Med 2010; 123:34–36.

- Douard R, Feldman A, Bargy F, Loric S, Delmas V. Anomalies of lateralization in man: a case of total situs in-versus. Surg Radiol Anat 2000; 22:293–297.

- Maldjian PD, Saric M. Approach to dextrocardia in adults: review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 188(suppl 6):S39–S49.

- Gindes L, Hegesh J, Barkai G, Jacobson JM, Achiron R. Isolated levocardia: prenatal diagnosis, clinical im-portance, and literature review. J Ultrasound Med 2007; 26:361–365.

- Abut E, Arman A, Güveli H, et al. Malposition of internal organs: a case of situs ambiguous anomaly in an adult. Turk J Gastroenterol 2003; 14:151–155.

- Kuehl KS, Loffredo C. Risk factors for heart disease associated with abnormal sidedness. Teratology 2002; 66:242–248.

- Aksoy S, Cam N, Gurkan U, Altay S, Bozbay M, Agirbasli M. Primary percutaneous intervention: for acute myo-cardial infarction in a patient with dextrocardia and situs inversus. Tex Heart Inst J 2012; 39:140–141.

- Murtuza B, Gupta P, Goli G, Lall KS. Coronary revascularization in adults with dextrocardia: surgical implications of the anatomic variants. Tex Heart Inst J 2010; 37:633–640.

A 76-year-old man presented to the emergency department with right-sided exertional chest pain radiating to the right shoulder and arm associated with shortness of breath. His vital signs were normal. On clinical examination, the cardiac apex was palpated on the right side, 9 cm from the midsternal line in the fifth intercostal space.

A standard left-sided 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed right-axis deviation and inverted P, QRS, and T waves in leads I and aVL (Figure 1). Although these changes are also seen when the right and left arm electrode wires are transposed, the precordial lead morphology in such a situation would usually be normal. In our patient, the precordial leads showed the absence or even slight reversal of R-wave progression, a feature indicative of dextrocardia.1,2

In patients with dextrocardia, right-sided hookup of the electrodes is usually necessary for proper interpretation of the ECG. When this was done in our patient, the ECG showed a normal cardiac axis, a negative QRS complex in lead aVR, a positive P wave and other complexes in lead I, and normal R-wave progression in the precordial leads—findings suggestive of dextrocardia (Figure 2).

Chest radiography showed a right-sided cardiac silhouette (Figure 3), and computed tomography of the abdomen (Figure 4) revealed the liver positioned on the left side and the spleen on the right, confirming the diagnosis of situs inversus totalis. The ECG showed dextrocardia, but no other abnormalities. The patient eventually underwent coronary angiography, which showed nonobstructive coronary artery disease.

DEXTROCARDIA, OTHER CONGENITAL CARDIOVASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

Dextrocardia was first described in early 17th century.1 Situs solitus is the normal position of the heart and viscera, whereas situs inversus is a mirror-image anatomic arrangement of the organs. Situs inversus with dextrocardia, also called situs inversus totalis, is a rare condition (with a prevalence of 1 in 8,000) in which the heart and descending aorta are on the right and the thoracic and abdominal viscera are usually mirror images of the normal morphology.1,3,4 A mirror-image sinus node lies at the junction of the left superior vena cava and the left-sided (morphologic right) atrium.1 People with situs inversus with dextrocardia are usually asymptomatic and have a normal life expectancy.1,2 Situs inversus with levocardia is a rare condition in which the heart is in the normal position but the viscera are in the dextro-position. This anomaly has a prevalence of 1 in 22,000.5

Atrial situs almost always corresponds to visceral situs. However, when the alignment of the atria and viscera is inconsistent and situs cannot be determined clearly because of the malpositioning of organs, the condition is called “situs ambiguous.” This is very rare, with a prevalence of 1 in 40,000.6

Risk factors

The cause of congenital cardiovascular malformations such as these is not known, but risk factors include positive family history, maternal diabetes, and cocaine use in the first trimester.7

The prevalence of congenital heart disease in patients with situs inversus with dextrocardia is low and ranges from 2% to 5%. This is in contrast to situs solitus with dextrocardia (isolated dextrocardia), which is almost always associated with cardiovascular anomalies.2,4 Kartagener syndrome—the triad of situs inversus, sinusitis, and bronchiectasis—occurs in 25% of people with situs inversus with dextrocardia.4 Situs inversus with levocardia is also frequently associated with cardiac anomalies.5

The major features of dextrocardia on ECG are:

- Negative P wave, QRS complex, and T wave in lead I

- Positive QRS complex in aVR

- Right-axis deviation

- Reversal of R-wave progression in the precordial leads.

Ventricular activation and repolarization are reversed, resulting in a negative QRS complex and an inverted T wave in lead I. The absence of R-wave progression in the precordial leads helps differentiate mirror-image dextrocardia from erroneously reversed limb-electrode placement, which shows normal R-wave progression from V1 to V6 while showing similar features to those seen in dextrocardia in the limb leads.2 In right-sided hookup, the limb electrodes are reversed, and the chest electrodes are recorded from the right precordium.

CORONARY INTERVENTIONS REQUIRE SPECIAL CONSIDERATION

In patients with dextrocardia, coronary interventions can be challenging because of the mirror-image position of the coronary ostia and the aortic arch.8 These patients also need careful imaging, consideration of other associated congenital cardiac abnormalities, and detailed planning before cardiac surgery, including coronary artery bypass grafting.9

Patients with dextrocardia may present with cardiac symptoms localized to the right side of the body and have confusing clinical and diagnostic findings. Keeping dextrocardia and other such anomalies in mind can prevent delay in appropriately directed interventions. In a patient such as ours, the heart on the right side of the chest may indeed be “right.” Still, diagnostic tests to look for disorders encountered with dextrocardia may be necessary.

A 76-year-old man presented to the emergency department with right-sided exertional chest pain radiating to the right shoulder and arm associated with shortness of breath. His vital signs were normal. On clinical examination, the cardiac apex was palpated on the right side, 9 cm from the midsternal line in the fifth intercostal space.

A standard left-sided 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed right-axis deviation and inverted P, QRS, and T waves in leads I and aVL (Figure 1). Although these changes are also seen when the right and left arm electrode wires are transposed, the precordial lead morphology in such a situation would usually be normal. In our patient, the precordial leads showed the absence or even slight reversal of R-wave progression, a feature indicative of dextrocardia.1,2

In patients with dextrocardia, right-sided hookup of the electrodes is usually necessary for proper interpretation of the ECG. When this was done in our patient, the ECG showed a normal cardiac axis, a negative QRS complex in lead aVR, a positive P wave and other complexes in lead I, and normal R-wave progression in the precordial leads—findings suggestive of dextrocardia (Figure 2).

Chest radiography showed a right-sided cardiac silhouette (Figure 3), and computed tomography of the abdomen (Figure 4) revealed the liver positioned on the left side and the spleen on the right, confirming the diagnosis of situs inversus totalis. The ECG showed dextrocardia, but no other abnormalities. The patient eventually underwent coronary angiography, which showed nonobstructive coronary artery disease.

DEXTROCARDIA, OTHER CONGENITAL CARDIOVASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

Dextrocardia was first described in early 17th century.1 Situs solitus is the normal position of the heart and viscera, whereas situs inversus is a mirror-image anatomic arrangement of the organs. Situs inversus with dextrocardia, also called situs inversus totalis, is a rare condition (with a prevalence of 1 in 8,000) in which the heart and descending aorta are on the right and the thoracic and abdominal viscera are usually mirror images of the normal morphology.1,3,4 A mirror-image sinus node lies at the junction of the left superior vena cava and the left-sided (morphologic right) atrium.1 People with situs inversus with dextrocardia are usually asymptomatic and have a normal life expectancy.1,2 Situs inversus with levocardia is a rare condition in which the heart is in the normal position but the viscera are in the dextro-position. This anomaly has a prevalence of 1 in 22,000.5

Atrial situs almost always corresponds to visceral situs. However, when the alignment of the atria and viscera is inconsistent and situs cannot be determined clearly because of the malpositioning of organs, the condition is called “situs ambiguous.” This is very rare, with a prevalence of 1 in 40,000.6

Risk factors

The cause of congenital cardiovascular malformations such as these is not known, but risk factors include positive family history, maternal diabetes, and cocaine use in the first trimester.7

The prevalence of congenital heart disease in patients with situs inversus with dextrocardia is low and ranges from 2% to 5%. This is in contrast to situs solitus with dextrocardia (isolated dextrocardia), which is almost always associated with cardiovascular anomalies.2,4 Kartagener syndrome—the triad of situs inversus, sinusitis, and bronchiectasis—occurs in 25% of people with situs inversus with dextrocardia.4 Situs inversus with levocardia is also frequently associated with cardiac anomalies.5

The major features of dextrocardia on ECG are:

- Negative P wave, QRS complex, and T wave in lead I

- Positive QRS complex in aVR

- Right-axis deviation

- Reversal of R-wave progression in the precordial leads.

Ventricular activation and repolarization are reversed, resulting in a negative QRS complex and an inverted T wave in lead I. The absence of R-wave progression in the precordial leads helps differentiate mirror-image dextrocardia from erroneously reversed limb-electrode placement, which shows normal R-wave progression from V1 to V6 while showing similar features to those seen in dextrocardia in the limb leads.2 In right-sided hookup, the limb electrodes are reversed, and the chest electrodes are recorded from the right precordium.

CORONARY INTERVENTIONS REQUIRE SPECIAL CONSIDERATION

In patients with dextrocardia, coronary interventions can be challenging because of the mirror-image position of the coronary ostia and the aortic arch.8 These patients also need careful imaging, consideration of other associated congenital cardiac abnormalities, and detailed planning before cardiac surgery, including coronary artery bypass grafting.9

Patients with dextrocardia may present with cardiac symptoms localized to the right side of the body and have confusing clinical and diagnostic findings. Keeping dextrocardia and other such anomalies in mind can prevent delay in appropriately directed interventions. In a patient such as ours, the heart on the right side of the chest may indeed be “right.” Still, diagnostic tests to look for disorders encountered with dextrocardia may be necessary.

- Perloff JK. The cardiac malpositions. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108:1352–1361.

- Tanawuttiwat T, Vasaiwala S, Dia M. ECG image of the month. Mirror mirror. Am J Med 2010; 123:34–36.

- Douard R, Feldman A, Bargy F, Loric S, Delmas V. Anomalies of lateralization in man: a case of total situs in-versus. Surg Radiol Anat 2000; 22:293–297.

- Maldjian PD, Saric M. Approach to dextrocardia in adults: review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 188(suppl 6):S39–S49.

- Gindes L, Hegesh J, Barkai G, Jacobson JM, Achiron R. Isolated levocardia: prenatal diagnosis, clinical im-portance, and literature review. J Ultrasound Med 2007; 26:361–365.

- Abut E, Arman A, Güveli H, et al. Malposition of internal organs: a case of situs ambiguous anomaly in an adult. Turk J Gastroenterol 2003; 14:151–155.

- Kuehl KS, Loffredo C. Risk factors for heart disease associated with abnormal sidedness. Teratology 2002; 66:242–248.

- Aksoy S, Cam N, Gurkan U, Altay S, Bozbay M, Agirbasli M. Primary percutaneous intervention: for acute myo-cardial infarction in a patient with dextrocardia and situs inversus. Tex Heart Inst J 2012; 39:140–141.

- Murtuza B, Gupta P, Goli G, Lall KS. Coronary revascularization in adults with dextrocardia: surgical implications of the anatomic variants. Tex Heart Inst J 2010; 37:633–640.

- Perloff JK. The cardiac malpositions. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108:1352–1361.

- Tanawuttiwat T, Vasaiwala S, Dia M. ECG image of the month. Mirror mirror. Am J Med 2010; 123:34–36.

- Douard R, Feldman A, Bargy F, Loric S, Delmas V. Anomalies of lateralization in man: a case of total situs in-versus. Surg Radiol Anat 2000; 22:293–297.

- Maldjian PD, Saric M. Approach to dextrocardia in adults: review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 188(suppl 6):S39–S49.

- Gindes L, Hegesh J, Barkai G, Jacobson JM, Achiron R. Isolated levocardia: prenatal diagnosis, clinical im-portance, and literature review. J Ultrasound Med 2007; 26:361–365.

- Abut E, Arman A, Güveli H, et al. Malposition of internal organs: a case of situs ambiguous anomaly in an adult. Turk J Gastroenterol 2003; 14:151–155.

- Kuehl KS, Loffredo C. Risk factors for heart disease associated with abnormal sidedness. Teratology 2002; 66:242–248.

- Aksoy S, Cam N, Gurkan U, Altay S, Bozbay M, Agirbasli M. Primary percutaneous intervention: for acute myo-cardial infarction in a patient with dextrocardia and situs inversus. Tex Heart Inst J 2012; 39:140–141.

- Murtuza B, Gupta P, Goli G, Lall KS. Coronary revascularization in adults with dextrocardia: surgical implications of the anatomic variants. Tex Heart Inst J 2010; 37:633–640.

Can an ARB be given to patients who have had angioedema on an ACE inhibitor?

Current evidence suggests no absolute contraindication to angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients who have had angioedema attributable to an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor. However, since ARBs can also cause angioedema, they should be prescribed with extreme caution after a thorough risk-benefit analysis and after educating the patient to watch for signs of angioedema while taking the drug.

A GROWING PROBLEM

Angioedema is a potentially life-threatening swelling of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, often affecting the lips and tongue (Figure 1), and in some cases interfering with breathing and requiring tracheostomy.1 The incidence rate of angioedema in patients taking ACE inhibitors ranges from 0.1% to 0.7%.2–4 Although this rate may seem low, the widespread and growing use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in patients with diabetes, diabetic nephropathy, and congestive heart failure5 makes angioedema fairly common in clinical practice.

ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema most commonly occurs within days of initiating therapy, but it also may occur weeks, months, or even years after the start of treatment.1 Patients who are over age 65, black, or female are at higher risk, as are renal transplant recipients taking mTOR inhibitors such as sirolimus. Diabetes appears to be associated with a lower risk.4,6,7 This adverse reaction to ACE inhibitors is thought to be a class side effect, and the future use of this class of drugs would be contraindicated.8,9

ACE inhibitors cause angioedema by direct interference with the degradation of bradykinin, thereby increasing bradykinin levels and potentiating its biologic effect, leading to increased vascular permeability, inflammation, and activation of nociceptors.8

EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT THE USE OF ARBs

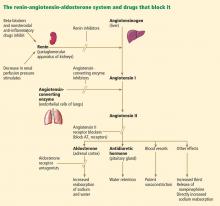

ACE inhibitors and ARBs both block the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone pathway and confer similar advantages in patients with congestive heart failure, renal failure, and diabetes. But since ARBs directly inhibit the angiotensin receptor and do not interfere with bradykinin degradation, how they cause angioedema is unclear, and clinicians have questioned whether these agents might be used safely in patients who have had angioedema on an ACE inhibitor.

In a large meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, Makani et al2 investigated the risk of angioedema with ARB use in 35,479 patients and compared this with other commonly used antihypertensive drugs. The weighted incidence of angioedema was 0.30% with an ACE inhibitor, 0.11% with an ARB, and 0.07% with placebo.2 In seven trials included in this study that compared ARBs with placebo, there was no significant difference in the risk of angioedema. Even in such a large study, the event rate was small, making definite conclusions difficult.

In a retrospective observational study of 4 million patients by Toh et al,3 patients on beta-blockers were used as a reference, and propensity scoring was used to estimate the hazard ratio of angioedema separately for drugs targeting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, including ACE inhibitors and ARBs. The risk of angioedema, as measured by the cumulative incidence and incidence rate, was highest for ACE inhibitors and was similar between ARBs and beta-blockers. The risk of serious angioedema was three times higher with ACE inhibitors than with beta-blockers, and there was no higher risk of serious angioedema with ARBs than with beta-blockers.3

Looking specifically at the use of ARBs in patients who developed angioedema on an ACE inhibitor, Haymore et al10 performed a meta-analysis evaluating only three studies that showed the estimated risk of angioedema with an ARB was between 3.5% and 9.4% in patients with a history of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. Later, when the results of the Telmisartan Randomised Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease trial11 were published, the previous meta-analysis was updated12: the risk of angioedema with an ARB was only 2.5% (95% confidence interval 0%–6.6%), and there was no statistically significant difference in the odds (odds ratio 1.1; 95% confidence interval 0.07–17) of angioedema between ARBs and placebo.10,12 Again, these results should be interpreted with caution, as only two patients in the ARB (telmisartan) group and three patients in the placebo group developed angioedema.

In another review, Beavers et al13 advised that the prescribing practitioner should carefully perform a risk-benefit analysis before substituting an ARB in patients with ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. They concluded that an ARB could be considered in patients who are likely to have a large clinical benefit from an ARB, such as those with heart failure. They also suggested that angioedema related to ARBs was less severe and occurred earlier than with that linked to ACE inhibitors.

No large clinical trial has yet been specifically designed to address the use of ARBs in patients with a history of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. The package insert for the ARB losartan mentions that the risk of this adverse reaction might be higher in patients who have had angioedema on an ACE inhibitor. However, the issue of recurrent angioedema is not further addressed for this or other commonly used ARBs.

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS

The mechanisms of ARB-induced angioedema are yet unknown. However, studies have shown that the incidence of angioedema while on an ARB is low and is probably comparable to that of placebo.2,3,12–14 And since ARBs share many of the cardiac and renal protective effects of ACE inhibitors, ARBs may be beneficial for patients who discontinue an ACE inhibitor because of adverse effects including angioedema.9,15,16 Based on the discussion above, there is no clear evidence to suggest that ARBs are contraindicated in such patients, especially if there is a compelling indication for an ARB.

The National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF KDOQI) guidelines on hypertension in chronic kidney disease recommend caution when substituting an ARB for an ACE inhibitor after angioedema.15 The joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults advise “extreme caution.”9,16

The risks and benefits of ARB therapy in this setting should be analyzed by the prescribing physician and discussed with the patient. The patient should be closely monitored for the recurrence of angioedema and should be given a clear plan of action should symptoms recur.

OUR ADVICE

In patients with ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema, we recommend the following:

- Determine that the patient truly has one of the evidence-based, compelling indications for an ARB. Carefully weigh the risks and benefits for the individual patient, and discuss the risk of angioedema based on age, race, sex, and medical history, and the availability of immediate medical care should angioedema occur.

- If there is an evidence-based indication for an ARB that outweighs the risk of angioedema, an ARB may be started with caution.

- Specifically discuss with the patient the possibility of recurrence of angioedema while on an ARB, and provide instructions on how to proceed if this should occur.

- Kaplan AP, Greaves MW. Angioedema. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 53:373–388.

- Makani H, Messerli FH, Romero J, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized trials of angioedema as an adverse event of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Am J Cardiol 2012; 110:383–391.

- Toh S, Reichman ME, Houstoun M, et al. Comparative risk for angioedema associated with the use of drugs that target the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172:1582–1589.

- Kostis JB, Kim HJ, Rusnak J, et al. Incidence and characteristics of angioedema associated with enalapril. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:1637–1642.

- Taylor AA, Siragy H, Nesbitt S. Angiotensin receptor blockers: pharmacology, efficacy, and safety. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2011; 13:677–686.

- Duerr M, Glander P, Diekmann F, Dragun D, Neumayer HH, Budde K. Increased incidence of angioedema with ACE inhibitors in combination with mTOR inhibitors in kidney transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:703–708.

- Byrd JB, Adam A, Brown NJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2006; 26:725–737.

- Inomata N. Recent advances in drug-induced angioedema. Allergol Int 2012; 61:545–557.

- Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:e1–e90.

- Haymore BR, Yoon J, Mikita CP, Klote MM, DeZee KJ. Risk of angioedema with angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with prior angioedema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008; 101:495–499.

- Telmisartan Randomised Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects with Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 372:1174–1183.

- Haymore BR, DeZee KJ. Use of angiotensin receptor blockers after angioedema with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2009; 103:83–84.

- Beavers CJ, Dunn SP, Macaulay TE. The role of angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:520–524.

- Caldeira D, David C, Sampaio C. Tolerability of angiotensin-receptor blockers in patients with intolerance to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2012; 12:263–277.

- Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43(suppl 1):S1–S290.

- Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:2432–2446.

Current evidence suggests no absolute contraindication to angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients who have had angioedema attributable to an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor. However, since ARBs can also cause angioedema, they should be prescribed with extreme caution after a thorough risk-benefit analysis and after educating the patient to watch for signs of angioedema while taking the drug.

A GROWING PROBLEM

Angioedema is a potentially life-threatening swelling of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, often affecting the lips and tongue (Figure 1), and in some cases interfering with breathing and requiring tracheostomy.1 The incidence rate of angioedema in patients taking ACE inhibitors ranges from 0.1% to 0.7%.2–4 Although this rate may seem low, the widespread and growing use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in patients with diabetes, diabetic nephropathy, and congestive heart failure5 makes angioedema fairly common in clinical practice.

ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema most commonly occurs within days of initiating therapy, but it also may occur weeks, months, or even years after the start of treatment.1 Patients who are over age 65, black, or female are at higher risk, as are renal transplant recipients taking mTOR inhibitors such as sirolimus. Diabetes appears to be associated with a lower risk.4,6,7 This adverse reaction to ACE inhibitors is thought to be a class side effect, and the future use of this class of drugs would be contraindicated.8,9

ACE inhibitors cause angioedema by direct interference with the degradation of bradykinin, thereby increasing bradykinin levels and potentiating its biologic effect, leading to increased vascular permeability, inflammation, and activation of nociceptors.8

EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT THE USE OF ARBs

ACE inhibitors and ARBs both block the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone pathway and confer similar advantages in patients with congestive heart failure, renal failure, and diabetes. But since ARBs directly inhibit the angiotensin receptor and do not interfere with bradykinin degradation, how they cause angioedema is unclear, and clinicians have questioned whether these agents might be used safely in patients who have had angioedema on an ACE inhibitor.

In a large meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, Makani et al2 investigated the risk of angioedema with ARB use in 35,479 patients and compared this with other commonly used antihypertensive drugs. The weighted incidence of angioedema was 0.30% with an ACE inhibitor, 0.11% with an ARB, and 0.07% with placebo.2 In seven trials included in this study that compared ARBs with placebo, there was no significant difference in the risk of angioedema. Even in such a large study, the event rate was small, making definite conclusions difficult.

In a retrospective observational study of 4 million patients by Toh et al,3 patients on beta-blockers were used as a reference, and propensity scoring was used to estimate the hazard ratio of angioedema separately for drugs targeting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, including ACE inhibitors and ARBs. The risk of angioedema, as measured by the cumulative incidence and incidence rate, was highest for ACE inhibitors and was similar between ARBs and beta-blockers. The risk of serious angioedema was three times higher with ACE inhibitors than with beta-blockers, and there was no higher risk of serious angioedema with ARBs than with beta-blockers.3

Looking specifically at the use of ARBs in patients who developed angioedema on an ACE inhibitor, Haymore et al10 performed a meta-analysis evaluating only three studies that showed the estimated risk of angioedema with an ARB was between 3.5% and 9.4% in patients with a history of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. Later, when the results of the Telmisartan Randomised Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease trial11 were published, the previous meta-analysis was updated12: the risk of angioedema with an ARB was only 2.5% (95% confidence interval 0%–6.6%), and there was no statistically significant difference in the odds (odds ratio 1.1; 95% confidence interval 0.07–17) of angioedema between ARBs and placebo.10,12 Again, these results should be interpreted with caution, as only two patients in the ARB (telmisartan) group and three patients in the placebo group developed angioedema.

In another review, Beavers et al13 advised that the prescribing practitioner should carefully perform a risk-benefit analysis before substituting an ARB in patients with ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. They concluded that an ARB could be considered in patients who are likely to have a large clinical benefit from an ARB, such as those with heart failure. They also suggested that angioedema related to ARBs was less severe and occurred earlier than with that linked to ACE inhibitors.

No large clinical trial has yet been specifically designed to address the use of ARBs in patients with a history of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. The package insert for the ARB losartan mentions that the risk of this adverse reaction might be higher in patients who have had angioedema on an ACE inhibitor. However, the issue of recurrent angioedema is not further addressed for this or other commonly used ARBs.

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS

The mechanisms of ARB-induced angioedema are yet unknown. However, studies have shown that the incidence of angioedema while on an ARB is low and is probably comparable to that of placebo.2,3,12–14 And since ARBs share many of the cardiac and renal protective effects of ACE inhibitors, ARBs may be beneficial for patients who discontinue an ACE inhibitor because of adverse effects including angioedema.9,15,16 Based on the discussion above, there is no clear evidence to suggest that ARBs are contraindicated in such patients, especially if there is a compelling indication for an ARB.

The National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF KDOQI) guidelines on hypertension in chronic kidney disease recommend caution when substituting an ARB for an ACE inhibitor after angioedema.15 The joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults advise “extreme caution.”9,16

The risks and benefits of ARB therapy in this setting should be analyzed by the prescribing physician and discussed with the patient. The patient should be closely monitored for the recurrence of angioedema and should be given a clear plan of action should symptoms recur.

OUR ADVICE

In patients with ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema, we recommend the following:

- Determine that the patient truly has one of the evidence-based, compelling indications for an ARB. Carefully weigh the risks and benefits for the individual patient, and discuss the risk of angioedema based on age, race, sex, and medical history, and the availability of immediate medical care should angioedema occur.

- If there is an evidence-based indication for an ARB that outweighs the risk of angioedema, an ARB may be started with caution.

- Specifically discuss with the patient the possibility of recurrence of angioedema while on an ARB, and provide instructions on how to proceed if this should occur.

Current evidence suggests no absolute contraindication to angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients who have had angioedema attributable to an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor. However, since ARBs can also cause angioedema, they should be prescribed with extreme caution after a thorough risk-benefit analysis and after educating the patient to watch for signs of angioedema while taking the drug.

A GROWING PROBLEM

Angioedema is a potentially life-threatening swelling of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, often affecting the lips and tongue (Figure 1), and in some cases interfering with breathing and requiring tracheostomy.1 The incidence rate of angioedema in patients taking ACE inhibitors ranges from 0.1% to 0.7%.2–4 Although this rate may seem low, the widespread and growing use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in patients with diabetes, diabetic nephropathy, and congestive heart failure5 makes angioedema fairly common in clinical practice.

ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema most commonly occurs within days of initiating therapy, but it also may occur weeks, months, or even years after the start of treatment.1 Patients who are over age 65, black, or female are at higher risk, as are renal transplant recipients taking mTOR inhibitors such as sirolimus. Diabetes appears to be associated with a lower risk.4,6,7 This adverse reaction to ACE inhibitors is thought to be a class side effect, and the future use of this class of drugs would be contraindicated.8,9

ACE inhibitors cause angioedema by direct interference with the degradation of bradykinin, thereby increasing bradykinin levels and potentiating its biologic effect, leading to increased vascular permeability, inflammation, and activation of nociceptors.8

EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT THE USE OF ARBs

ACE inhibitors and ARBs both block the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone pathway and confer similar advantages in patients with congestive heart failure, renal failure, and diabetes. But since ARBs directly inhibit the angiotensin receptor and do not interfere with bradykinin degradation, how they cause angioedema is unclear, and clinicians have questioned whether these agents might be used safely in patients who have had angioedema on an ACE inhibitor.

In a large meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, Makani et al2 investigated the risk of angioedema with ARB use in 35,479 patients and compared this with other commonly used antihypertensive drugs. The weighted incidence of angioedema was 0.30% with an ACE inhibitor, 0.11% with an ARB, and 0.07% with placebo.2 In seven trials included in this study that compared ARBs with placebo, there was no significant difference in the risk of angioedema. Even in such a large study, the event rate was small, making definite conclusions difficult.

In a retrospective observational study of 4 million patients by Toh et al,3 patients on beta-blockers were used as a reference, and propensity scoring was used to estimate the hazard ratio of angioedema separately for drugs targeting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, including ACE inhibitors and ARBs. The risk of angioedema, as measured by the cumulative incidence and incidence rate, was highest for ACE inhibitors and was similar between ARBs and beta-blockers. The risk of serious angioedema was three times higher with ACE inhibitors than with beta-blockers, and there was no higher risk of serious angioedema with ARBs than with beta-blockers.3

Looking specifically at the use of ARBs in patients who developed angioedema on an ACE inhibitor, Haymore et al10 performed a meta-analysis evaluating only three studies that showed the estimated risk of angioedema with an ARB was between 3.5% and 9.4% in patients with a history of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. Later, when the results of the Telmisartan Randomised Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease trial11 were published, the previous meta-analysis was updated12: the risk of angioedema with an ARB was only 2.5% (95% confidence interval 0%–6.6%), and there was no statistically significant difference in the odds (odds ratio 1.1; 95% confidence interval 0.07–17) of angioedema between ARBs and placebo.10,12 Again, these results should be interpreted with caution, as only two patients in the ARB (telmisartan) group and three patients in the placebo group developed angioedema.

In another review, Beavers et al13 advised that the prescribing practitioner should carefully perform a risk-benefit analysis before substituting an ARB in patients with ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. They concluded that an ARB could be considered in patients who are likely to have a large clinical benefit from an ARB, such as those with heart failure. They also suggested that angioedema related to ARBs was less severe and occurred earlier than with that linked to ACE inhibitors.

No large clinical trial has yet been specifically designed to address the use of ARBs in patients with a history of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. The package insert for the ARB losartan mentions that the risk of this adverse reaction might be higher in patients who have had angioedema on an ACE inhibitor. However, the issue of recurrent angioedema is not further addressed for this or other commonly used ARBs.

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS

The mechanisms of ARB-induced angioedema are yet unknown. However, studies have shown that the incidence of angioedema while on an ARB is low and is probably comparable to that of placebo.2,3,12–14 And since ARBs share many of the cardiac and renal protective effects of ACE inhibitors, ARBs may be beneficial for patients who discontinue an ACE inhibitor because of adverse effects including angioedema.9,15,16 Based on the discussion above, there is no clear evidence to suggest that ARBs are contraindicated in such patients, especially if there is a compelling indication for an ARB.

The National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF KDOQI) guidelines on hypertension in chronic kidney disease recommend caution when substituting an ARB for an ACE inhibitor after angioedema.15 The joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults advise “extreme caution.”9,16

The risks and benefits of ARB therapy in this setting should be analyzed by the prescribing physician and discussed with the patient. The patient should be closely monitored for the recurrence of angioedema and should be given a clear plan of action should symptoms recur.

OUR ADVICE

In patients with ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema, we recommend the following:

- Determine that the patient truly has one of the evidence-based, compelling indications for an ARB. Carefully weigh the risks and benefits for the individual patient, and discuss the risk of angioedema based on age, race, sex, and medical history, and the availability of immediate medical care should angioedema occur.

- If there is an evidence-based indication for an ARB that outweighs the risk of angioedema, an ARB may be started with caution.

- Specifically discuss with the patient the possibility of recurrence of angioedema while on an ARB, and provide instructions on how to proceed if this should occur.

- Kaplan AP, Greaves MW. Angioedema. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 53:373–388.

- Makani H, Messerli FH, Romero J, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized trials of angioedema as an adverse event of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Am J Cardiol 2012; 110:383–391.

- Toh S, Reichman ME, Houstoun M, et al. Comparative risk for angioedema associated with the use of drugs that target the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172:1582–1589.

- Kostis JB, Kim HJ, Rusnak J, et al. Incidence and characteristics of angioedema associated with enalapril. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:1637–1642.

- Taylor AA, Siragy H, Nesbitt S. Angiotensin receptor blockers: pharmacology, efficacy, and safety. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2011; 13:677–686.

- Duerr M, Glander P, Diekmann F, Dragun D, Neumayer HH, Budde K. Increased incidence of angioedema with ACE inhibitors in combination with mTOR inhibitors in kidney transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:703–708.

- Byrd JB, Adam A, Brown NJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2006; 26:725–737.

- Inomata N. Recent advances in drug-induced angioedema. Allergol Int 2012; 61:545–557.

- Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:e1–e90.

- Haymore BR, Yoon J, Mikita CP, Klote MM, DeZee KJ. Risk of angioedema with angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with prior angioedema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008; 101:495–499.

- Telmisartan Randomised Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects with Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 372:1174–1183.

- Haymore BR, DeZee KJ. Use of angiotensin receptor blockers after angioedema with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2009; 103:83–84.

- Beavers CJ, Dunn SP, Macaulay TE. The role of angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:520–524.

- Caldeira D, David C, Sampaio C. Tolerability of angiotensin-receptor blockers in patients with intolerance to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2012; 12:263–277.

- Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43(suppl 1):S1–S290.

- Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:2432–2446.

- Kaplan AP, Greaves MW. Angioedema. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 53:373–388.

- Makani H, Messerli FH, Romero J, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized trials of angioedema as an adverse event of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Am J Cardiol 2012; 110:383–391.

- Toh S, Reichman ME, Houstoun M, et al. Comparative risk for angioedema associated with the use of drugs that target the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172:1582–1589.

- Kostis JB, Kim HJ, Rusnak J, et al. Incidence and characteristics of angioedema associated with enalapril. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:1637–1642.

- Taylor AA, Siragy H, Nesbitt S. Angiotensin receptor blockers: pharmacology, efficacy, and safety. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2011; 13:677–686.

- Duerr M, Glander P, Diekmann F, Dragun D, Neumayer HH, Budde K. Increased incidence of angioedema with ACE inhibitors in combination with mTOR inhibitors in kidney transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:703–708.

- Byrd JB, Adam A, Brown NJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2006; 26:725–737.

- Inomata N. Recent advances in drug-induced angioedema. Allergol Int 2012; 61:545–557.

- Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:e1–e90.

- Haymore BR, Yoon J, Mikita CP, Klote MM, DeZee KJ. Risk of angioedema with angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with prior angioedema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008; 101:495–499.

- Telmisartan Randomised Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects with Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 372:1174–1183.

- Haymore BR, DeZee KJ. Use of angiotensin receptor blockers after angioedema with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2009; 103:83–84.

- Beavers CJ, Dunn SP, Macaulay TE. The role of angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:520–524.

- Caldeira D, David C, Sampaio C. Tolerability of angiotensin-receptor blockers in patients with intolerance to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2012; 12:263–277.

- Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43(suppl 1):S1–S290.

- Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:2432–2446.

Implications of a prominent R wave in V1

A 19-year-old woman with no significant cardiac or pulmonary history presented with exertional dyspnea, which had begun a few months earlier. Auscultation revealed a loud pulmonary component of the second heart sound and a diastolic murmur heard along the upper left sternal border. Her 12-lead electrocardiogram is shown in Figure 1.

Q: Which of the following can cause prominent R waves in lead V1?

- Normal variant in young adults

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

- Posterior wall myocardial infarction

- Right ventricular hypertrophy

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.

The patient’s electrocardiogram shows a right atrial abnormality and right ventricular hypertrophy. Right atrial enlargement is evidenced by a prominent initial P wave in V1 with an amplitude of at least 1.5 mm (0.15 mV). A P wave taller than 2.5 mm (0.25 mV) in lead II may also suggest a right atrial abnormality.1

Multiple criteria exist for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy. Tall R waves in V1 with an R/S ratio greater than 1 (ie, the R wave amplitude is more than the S wave depth) is commonly used.2 Deep S waves with an R/S ratio less than 1 in V6 is another criterion. Tall R waves of amplitude greater than 7 mm in V1 by themselves may represent right ventricular hypertrophy. Most of the electrocardiographic criteria are specific but not sensitive for this diagnosis.3

Other causes of tall R waves in V1 are given in Table 1.

Q: Which of the following diseases can present with an electrocardiographic pattern of right ventricular hypertrophy in young patients?

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Atrial septal defect

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Pulmonary stenosis

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.4

Our patient underwent multiple investigations. On echocardiography, her estimated right ventricular pressure was 80 mm Hg, and on cardiac catheterization her mean pulmonary arterial pressure was 55 mm Hg and her pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 6 mm Hg. She was diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension, which was the cause of her right ventricular hypertrophy. She eventually underwent bilateral lung transplantation.

- Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American College of Cardiology Foundation; Heart Rhythm Society. AHA/ ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation 2009; 119:e251–e261.

- Milnor WR. Electrocardiogram and vectorcardiogram in right ventricular hypertrophy and right bundle-branch block. Circulation 1957; 16:348–367.

- Lehtonen J, Sutinen S, Ikäheimo M, Pääkkö P. Electrocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy verified at autopsy. Chest 1988; 93:839–842.

- Webb G, Gatzoulis MA. Atrial septal defects in the adult: recent progress and overview. Circulation 2006; 114:1645–1653.

A 19-year-old woman with no significant cardiac or pulmonary history presented with exertional dyspnea, which had begun a few months earlier. Auscultation revealed a loud pulmonary component of the second heart sound and a diastolic murmur heard along the upper left sternal border. Her 12-lead electrocardiogram is shown in Figure 1.

Q: Which of the following can cause prominent R waves in lead V1?

- Normal variant in young adults

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

- Posterior wall myocardial infarction

- Right ventricular hypertrophy

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.

The patient’s electrocardiogram shows a right atrial abnormality and right ventricular hypertrophy. Right atrial enlargement is evidenced by a prominent initial P wave in V1 with an amplitude of at least 1.5 mm (0.15 mV). A P wave taller than 2.5 mm (0.25 mV) in lead II may also suggest a right atrial abnormality.1

Multiple criteria exist for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy. Tall R waves in V1 with an R/S ratio greater than 1 (ie, the R wave amplitude is more than the S wave depth) is commonly used.2 Deep S waves with an R/S ratio less than 1 in V6 is another criterion. Tall R waves of amplitude greater than 7 mm in V1 by themselves may represent right ventricular hypertrophy. Most of the electrocardiographic criteria are specific but not sensitive for this diagnosis.3

Other causes of tall R waves in V1 are given in Table 1.

Q: Which of the following diseases can present with an electrocardiographic pattern of right ventricular hypertrophy in young patients?

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Atrial septal defect

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Pulmonary stenosis

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.4

Our patient underwent multiple investigations. On echocardiography, her estimated right ventricular pressure was 80 mm Hg, and on cardiac catheterization her mean pulmonary arterial pressure was 55 mm Hg and her pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 6 mm Hg. She was diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension, which was the cause of her right ventricular hypertrophy. She eventually underwent bilateral lung transplantation.

A 19-year-old woman with no significant cardiac or pulmonary history presented with exertional dyspnea, which had begun a few months earlier. Auscultation revealed a loud pulmonary component of the second heart sound and a diastolic murmur heard along the upper left sternal border. Her 12-lead electrocardiogram is shown in Figure 1.

Q: Which of the following can cause prominent R waves in lead V1?

- Normal variant in young adults

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

- Posterior wall myocardial infarction

- Right ventricular hypertrophy

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.

The patient’s electrocardiogram shows a right atrial abnormality and right ventricular hypertrophy. Right atrial enlargement is evidenced by a prominent initial P wave in V1 with an amplitude of at least 1.5 mm (0.15 mV). A P wave taller than 2.5 mm (0.25 mV) in lead II may also suggest a right atrial abnormality.1

Multiple criteria exist for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy. Tall R waves in V1 with an R/S ratio greater than 1 (ie, the R wave amplitude is more than the S wave depth) is commonly used.2 Deep S waves with an R/S ratio less than 1 in V6 is another criterion. Tall R waves of amplitude greater than 7 mm in V1 by themselves may represent right ventricular hypertrophy. Most of the electrocardiographic criteria are specific but not sensitive for this diagnosis.3

Other causes of tall R waves in V1 are given in Table 1.

Q: Which of the following diseases can present with an electrocardiographic pattern of right ventricular hypertrophy in young patients?

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Atrial septal defect

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Pulmonary stenosis

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.4

Our patient underwent multiple investigations. On echocardiography, her estimated right ventricular pressure was 80 mm Hg, and on cardiac catheterization her mean pulmonary arterial pressure was 55 mm Hg and her pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 6 mm Hg. She was diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension, which was the cause of her right ventricular hypertrophy. She eventually underwent bilateral lung transplantation.

- Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American College of Cardiology Foundation; Heart Rhythm Society. AHA/ ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation 2009; 119:e251–e261.

- Milnor WR. Electrocardiogram and vectorcardiogram in right ventricular hypertrophy and right bundle-branch block. Circulation 1957; 16:348–367.

- Lehtonen J, Sutinen S, Ikäheimo M, Pääkkö P. Electrocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy verified at autopsy. Chest 1988; 93:839–842.

- Webb G, Gatzoulis MA. Atrial septal defects in the adult: recent progress and overview. Circulation 2006; 114:1645–1653.

- Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American College of Cardiology Foundation; Heart Rhythm Society. AHA/ ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation 2009; 119:e251–e261.

- Milnor WR. Electrocardiogram and vectorcardiogram in right ventricular hypertrophy and right bundle-branch block. Circulation 1957; 16:348–367.

- Lehtonen J, Sutinen S, Ikäheimo M, Pääkkö P. Electrocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy verified at autopsy. Chest 1988; 93:839–842.

- Webb G, Gatzoulis MA. Atrial septal defects in the adult: recent progress and overview. Circulation 2006; 114:1645–1653.

Giant inverted T waves

A 48-year-old man with hypertension was being evaluated for a noncardiac issue (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy). He had been an active runner and did not have any cardiovascular symptoms at the time. The electrocardiogram (ECG) shown in Figure 1 was a routine study done as a part of that evaluation. His cardiovascular examination was unremarkable, without murmur, S3, or S4. His pulse was regular at 72 beats per minute, and his blood pressure was 112/76 mm Hg.

Q: Which of the following electrocardiographic findings suggest left ventricular hypertrophy?

- Sum of the S wave in V1 and the R wave in V6 ≥ 35 mm

- Sum of the S wave in V3 and the R wave in aVL > 28 mm (men)

- Sum of the S wave in V3 and the R wave in aVL > 20 mm (women)

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.1,2

Our patient’s ECG shows sinus bradycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy, suggested by prominent voltage (sum of S in V1 and R in V6 ≥ 35 mm) and supported by ST-segment and T-wave changes in the lateral and midprecordial leads. Classic changes of left ventricular hypertrophy often include increased voltage and downsloping ST-segment depression with negative T waves in V5 and V6 (secondary repolarization changes or “strain” pattern).

Notable on this tracing are the large, asymmetric negative T waves in leads V3 through V6. Giant T waves are defined as negative T waves with voltage greater than 10 mm.3 Although there is no specific pattern of ventricular hypertrophy on an ECG that establishes the diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular hypertrophy with T waves of this quality suggest the possibility of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with apical hypertrophy.

Q: What are the other causes of giant negative T waves?

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Complete heart block

- Non-Q-wave myocardial infarction

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above. Additional causes of dramatic T-wave inversion are listed in Table 1. Clinically, non-Q-wave myocardial infarction with T-wave changes and acute central nervous system injury are probably the most commonly seen.4

Echocardiography in this patient revealed severe apical hypertrophy of the ventricle with distal cavity obliteration. The left ventricular outflow-tract gradient was normal. The mitral valve appeared normal, and there was no resting systolic anterior motion.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed the apical variant of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy but no evidence of left ventricular noncompaction, which is a differential diagnosis of apical hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. This disease was first described in Japan by Yamaguchi et al5 and Sakamoto et al6 and is regarded as a subgroup of nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The prognosis of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with regard to sudden cardiac death is believed to be better than that of other forms of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.3

- Sokolow M, Lyon TP. The ventricular complex in left ventricular hypertrophy as obtained by unipolar precordial and limb leads. 1949. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2001; 6:343–368.

- Casale PN, Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Campo E, Kligfield P. Improved sex-specific criteria of left ventricular hypertrophy for clinical and computer interpretation of electrocardiograms: validation with autopsy findings. Circulation 1987; 75:565–572.

- Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:638–645.

- Jacobson D, Schrire V. Giant T wave inversion. Br Heart J 1966; 28:768–775.

- Yamaguchi H, Ishimura T, Nishiyama S, et al. Hypertrophic nonobstructive cardiomyopathy with giant negative T waves (apical hypertrophy): ventriculographic and echocardiographic features in 30 patients. Am J Cardiol 1979; 44:401–412.

- Sakamoto T, Tei C, Murayama M, Ichiyasu H, Hada Y. Giant T wave inversion as a manifestation of asymmetrical apical hypertrophy (AAH) of the left ventricle. Echocardiographic and ultrasonocardiotomographic study. Jpn Heart J 1976; 17:611–629.

A 48-year-old man with hypertension was being evaluated for a noncardiac issue (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy). He had been an active runner and did not have any cardiovascular symptoms at the time. The electrocardiogram (ECG) shown in Figure 1 was a routine study done as a part of that evaluation. His cardiovascular examination was unremarkable, without murmur, S3, or S4. His pulse was regular at 72 beats per minute, and his blood pressure was 112/76 mm Hg.

Q: Which of the following electrocardiographic findings suggest left ventricular hypertrophy?

- Sum of the S wave in V1 and the R wave in V6 ≥ 35 mm

- Sum of the S wave in V3 and the R wave in aVL > 28 mm (men)

- Sum of the S wave in V3 and the R wave in aVL > 20 mm (women)

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.1,2

Our patient’s ECG shows sinus bradycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy, suggested by prominent voltage (sum of S in V1 and R in V6 ≥ 35 mm) and supported by ST-segment and T-wave changes in the lateral and midprecordial leads. Classic changes of left ventricular hypertrophy often include increased voltage and downsloping ST-segment depression with negative T waves in V5 and V6 (secondary repolarization changes or “strain” pattern).

Notable on this tracing are the large, asymmetric negative T waves in leads V3 through V6. Giant T waves are defined as negative T waves with voltage greater than 10 mm.3 Although there is no specific pattern of ventricular hypertrophy on an ECG that establishes the diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular hypertrophy with T waves of this quality suggest the possibility of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with apical hypertrophy.

Q: What are the other causes of giant negative T waves?

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Complete heart block

- Non-Q-wave myocardial infarction

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above. Additional causes of dramatic T-wave inversion are listed in Table 1. Clinically, non-Q-wave myocardial infarction with T-wave changes and acute central nervous system injury are probably the most commonly seen.4

Echocardiography in this patient revealed severe apical hypertrophy of the ventricle with distal cavity obliteration. The left ventricular outflow-tract gradient was normal. The mitral valve appeared normal, and there was no resting systolic anterior motion.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed the apical variant of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy but no evidence of left ventricular noncompaction, which is a differential diagnosis of apical hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. This disease was first described in Japan by Yamaguchi et al5 and Sakamoto et al6 and is regarded as a subgroup of nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The prognosis of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with regard to sudden cardiac death is believed to be better than that of other forms of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.3

A 48-year-old man with hypertension was being evaluated for a noncardiac issue (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy). He had been an active runner and did not have any cardiovascular symptoms at the time. The electrocardiogram (ECG) shown in Figure 1 was a routine study done as a part of that evaluation. His cardiovascular examination was unremarkable, without murmur, S3, or S4. His pulse was regular at 72 beats per minute, and his blood pressure was 112/76 mm Hg.

Q: Which of the following electrocardiographic findings suggest left ventricular hypertrophy?

- Sum of the S wave in V1 and the R wave in V6 ≥ 35 mm

- Sum of the S wave in V3 and the R wave in aVL > 28 mm (men)

- Sum of the S wave in V3 and the R wave in aVL > 20 mm (women)

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.1,2

Our patient’s ECG shows sinus bradycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy, suggested by prominent voltage (sum of S in V1 and R in V6 ≥ 35 mm) and supported by ST-segment and T-wave changes in the lateral and midprecordial leads. Classic changes of left ventricular hypertrophy often include increased voltage and downsloping ST-segment depression with negative T waves in V5 and V6 (secondary repolarization changes or “strain” pattern).

Notable on this tracing are the large, asymmetric negative T waves in leads V3 through V6. Giant T waves are defined as negative T waves with voltage greater than 10 mm.3 Although there is no specific pattern of ventricular hypertrophy on an ECG that establishes the diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular hypertrophy with T waves of this quality suggest the possibility of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with apical hypertrophy.

Q: What are the other causes of giant negative T waves?

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Complete heart block

- Non-Q-wave myocardial infarction

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above. Additional causes of dramatic T-wave inversion are listed in Table 1. Clinically, non-Q-wave myocardial infarction with T-wave changes and acute central nervous system injury are probably the most commonly seen.4

Echocardiography in this patient revealed severe apical hypertrophy of the ventricle with distal cavity obliteration. The left ventricular outflow-tract gradient was normal. The mitral valve appeared normal, and there was no resting systolic anterior motion.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed the apical variant of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy but no evidence of left ventricular noncompaction, which is a differential diagnosis of apical hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. This disease was first described in Japan by Yamaguchi et al5 and Sakamoto et al6 and is regarded as a subgroup of nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The prognosis of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with regard to sudden cardiac death is believed to be better than that of other forms of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.3

- Sokolow M, Lyon TP. The ventricular complex in left ventricular hypertrophy as obtained by unipolar precordial and limb leads. 1949. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2001; 6:343–368.

- Casale PN, Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Campo E, Kligfield P. Improved sex-specific criteria of left ventricular hypertrophy for clinical and computer interpretation of electrocardiograms: validation with autopsy findings. Circulation 1987; 75:565–572.

- Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:638–645.

- Jacobson D, Schrire V. Giant T wave inversion. Br Heart J 1966; 28:768–775.

- Yamaguchi H, Ishimura T, Nishiyama S, et al. Hypertrophic nonobstructive cardiomyopathy with giant negative T waves (apical hypertrophy): ventriculographic and echocardiographic features in 30 patients. Am J Cardiol 1979; 44:401–412.

- Sakamoto T, Tei C, Murayama M, Ichiyasu H, Hada Y. Giant T wave inversion as a manifestation of asymmetrical apical hypertrophy (AAH) of the left ventricle. Echocardiographic and ultrasonocardiotomographic study. Jpn Heart J 1976; 17:611–629.

- Sokolow M, Lyon TP. The ventricular complex in left ventricular hypertrophy as obtained by unipolar precordial and limb leads. 1949. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2001; 6:343–368.

- Casale PN, Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Campo E, Kligfield P. Improved sex-specific criteria of left ventricular hypertrophy for clinical and computer interpretation of electrocardiograms: validation with autopsy findings. Circulation 1987; 75:565–572.

- Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:638–645.

- Jacobson D, Schrire V. Giant T wave inversion. Br Heart J 1966; 28:768–775.

- Yamaguchi H, Ishimura T, Nishiyama S, et al. Hypertrophic nonobstructive cardiomyopathy with giant negative T waves (apical hypertrophy): ventriculographic and echocardiographic features in 30 patients. Am J Cardiol 1979; 44:401–412.

- Sakamoto T, Tei C, Murayama M, Ichiyasu H, Hada Y. Giant T wave inversion as a manifestation of asymmetrical apical hypertrophy (AAH) of the left ventricle. Echocardiographic and ultrasonocardiotomographic study. Jpn Heart J 1976; 17:611–629.

V1: The most important lead in inferior STEMI

Q: Which would be the most appropriate diagnosis?

- Pericarditis

- Acute inferior and right ventricular myocardial infarction

- Anterior and inferior myocardial infarction

- None of the above

A: The correct answer is acute inferior and right ventricular myocardial infarction.

Her electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm and inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) evidenced by ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF. Hemodynamic instability or ST-segment elevation of more than 1 mm in lead V1 raises the suspicion of right ventricular myocardial infarction. In such patients, the American Heart Association guidelines recommend electrocardiography with right-sided precordial leads.1

A 1-mm ST-segment elevation in the right precordial lead V4R is one of the most predictive electrocardiographic findings in right ventricular infarction.2 The electrocardiographic changes in this type of myocardial infarction may be transient and resolve within 10 hours in up to 48% of cases.3

Echocardiography can also be used to confirm the possibility of right ventricular infarction.

Q: Which clinical condition can occur as a complication of right ventricular myocardial infarction?

- Profound hypotension after nitrate administration

- High-degree heart block

- Atrial fibrillation

- All of the above

A: All of the conditions can occur.

Right ventricular involvement is very common, noted in up to 50% of patients with acute inferior STEMI in postmortem studies.4 However, hemodynamically significant right ventricular dysfunction is much less common.

Intravenous volume loading with normal saline is one of the first steps in the management of hypotension associated with right ventricular infarction. Patients with significant bradycardia or a high degree of atrioventricular block may require pacing. Early reperfusion should be achieved, if possible. Heightened suspicion is critical to the early diagnosis of this condition, since the prognosis is much worse than for isolated inferior STEMI.4

Our patient was found to have right coronary artery disease requiring percutaneous coronary intervention.

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al; American College of Cardiology. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation 2004; 110:e82–e292.

- Robalino BD, Whitlow PL, Underwood DA, Salcedo EE. Electrocardiographic manifestations of right ventricular infarction. Am Heart J 1989; 118:138–144.

- Braat SH, Brugada P, de Zwaan C, Coenegracht JM, Wellens HJ. Value of electrocardiogram in diagnosing right ventricular involvement in patients with an acute inferior wall myocardial infarction. Br Heart J 1983; 49:368–372.

- Zehender M, Kasper W, Kauder E, et al. Right ventricular infarction as an independent predictor of prognosis after acute inferior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:981–988.

Q: Which would be the most appropriate diagnosis?

- Pericarditis

- Acute inferior and right ventricular myocardial infarction

- Anterior and inferior myocardial infarction

- None of the above

A: The correct answer is acute inferior and right ventricular myocardial infarction.