User login

Taking the Detour

A 60‐year‐old woman presented to a community hospital's emergency department with 4 days of right‐sided abdominal pain and multiple episodes of black stools. She reported nausea without vomiting. She denied light‐headedness, chest pain, or shortness of breath. She also denied difficulty in swallowing, weight loss, jaundice, or other bleeding.

The first priority when assessing a patient with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is to ensure hemodynamic stability. Next, it is important to carefully characterize the stools to help narrow the differential diagnosis. As blood is a cathartic, frequent, loose, and black stools suggest vigorous bleeding. It is essential to establish that the stools are actually black, as some patients will mistake dark brown stools for melena. Using a visual aid like a black pen or shoes as a point of reference can help the patient differentiate between dark stool and melena. It is also important to obtain a thorough medication history because iron supplements or bismuth‐containing remedies can turn stool black. The use of any antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants should also be noted. The right‐sided abdominal pain should be characterized by establishing the frequency, severity, and association with eating, movement, and position. For this patient's presentation, increased pain with eating would rapidly heighten concern for mesenteric ischemia.

The patient reported having 1 to 2 semiformed, tarry, black bowel movements per day. The night prior to admission she had passed some bright red blood along with the melena. The abdominal pain had increased gradually over 4 days, was dull, constant, did not radiate, and there were no evident aggravating or relieving factors. She rated the pain as 4 out of 10 in intensity, worst in her right upper quadrant.

Her past medical history was notable for recurrent deep venous thromboses and pulmonary emboli that had occurred even while on oral anticoagulation. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters had twice been placed many years prior; anticoagulation had been subsequently discontinued. Additionally, she was known to have chronic superior vena cava (SVC) occlusion, presumably related to hypercoagulability. Previous evaluation had identified only hyperhomocysteinemia as a risk factor for recurrent thromboses. Other medical problems included hemorrhoids, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and asthma. Her only surgical history was an abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy many years ago for nonmalignant disease. Home medications were omeprazole, ranitidine, albuterol, and fluticasone‐salmeterol. She denied using nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, aspirin, or any dietary supplements. She denied smoking, alcohol, or recreational drug use.

Because melena is confirmed, an upper GI tract bleeding source is most likely. The more recent appearance of bright red blood is concerning for acceleration of bleeding, or may point to a distal small bowel or right colonic source. Given the history of thromboembolic disease and likely underlying hypercoagulability, vascular occlusion is a leading possibility. Thus, mesenteric arterial insufficiency or mesenteric venous thrombosis should be considered, even though the patient does not report the characteristic postprandial exacerbation of pain. Ischemic colitis due to arterial insufficiency typically presents with severe, acute pain, with or without hematochezia. This syndrome is typically manifested in vascular watershed areas such as the splenic flexure, but can also affect the right colon. Mesenteric venous thrombosis is a rare condition that most often occurs in patients with hypercoagulability. Patients present with variable degrees of abdominal pain and often with GI bleeding. Finally, portal venous thrombosis may be seen alongside thromboses of other mesenteric veins or may occur independently. Portal hypertension due to portal vein thrombosis can result in esophageal and/or gastric varices. Although variceal bleeding classically presents with dramatic hematemesis, the absence of hematemesis does not rule out a variceal bleed in this patient.

On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 37.1C with a pulse of 90 beats per minute and blood pressure of 161/97 mm Hg. Orthostatics were not performed. No blood was seen on nasal and oropharyngeal exam. Respiratory and cardiovascular exams were normal. On abdominal exam, there was tenderness to palpation of the right upper quadrant without rebound or guarding. The spleen and the liver were not palpable. There was a lower midline incisional scar. Rectal exam revealed nonbleeding hemorrhoids and heme‐positive stool without gross blood. Bilateral lower extremities had trace pitting edema, hyperpigmentation, and superficial venous varicosities. On skin exam, there were distended subcutaneous veins radiating outward from around the umbilicus as well as prominent subcutaneous venous collaterals over the chest and lateral abdomen.

The collateral veins over the chest and lateral abdomen are consistent with central venous obstruction from the patient's known SVC thrombus. However, the presence of paraumbilical venous collaterals (caput medusa) is highly suggestive of portal hypertension. This evidence, in addition to the known central venous occlusion and history of thromboembolic disease, raises the suspicion for mesenteric thrombosis as a cause of her bleeding and pain. The first diagnostic procedure should be an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to identify and potentially treat the source of bleeding, whether it is portal hypertension related (portal gastropathy, variceal bleed) or from a more common cause (peptic ulcer disease, stress gastritis). If the EGD is not diagnostic, the next step should be to obtain computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast. In many patients with GI bleed, a colonoscopy would typically be performed as the next diagnostic study after EGD. However, in this patient, a CT scan is likely to be of higher yield because it could help assess the mesenteric and portal vessels for patency and characterize the appearance of the small intestine and colon. Depending on the findings of the CT, additional dedicated vascular diagnostics might be needed.

Hemoglobin was 8.5 g/dL (12.4 g/dL 6 weeks prior) with a normal mean corpuscular volume and red cell distribution. The white cell count was normal, and the platelet count was 142,000/mm3. The blood urea nitrogen was 27 mg/dL, with a creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL. Routine chemistries, liver enzymes, bilirubin, and coagulation parameters were normal. Ferritin was 15 ng/mL (normal: 15200 ng/mL).

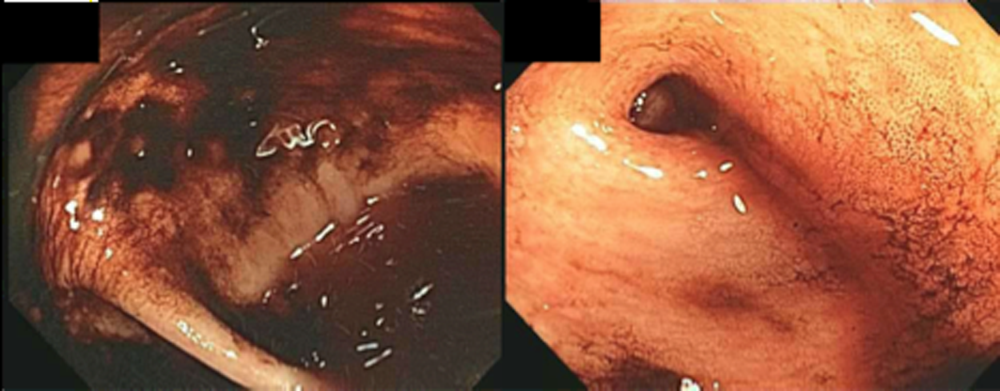

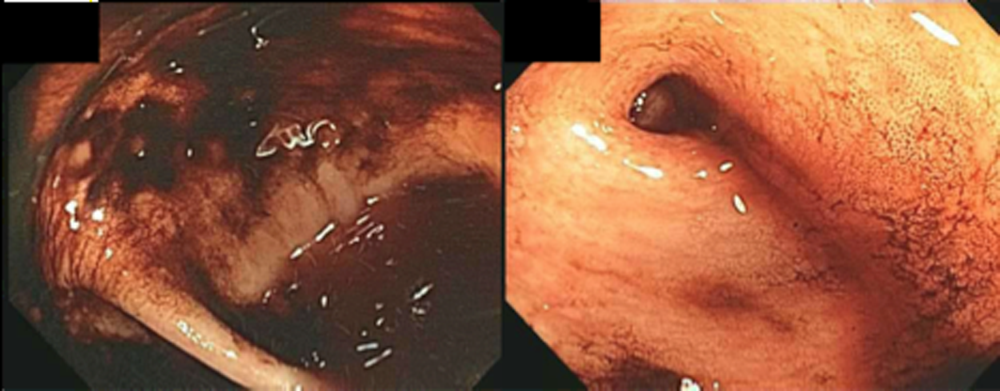

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. An EGD revealed a hiatal hernia and grade II nonbleeding esophageal varices with normal=appearing stomach and duodenum. The varices did not have stigmata of a recent bleed and were not ligated. The patient continued to bleed and received 2 U of packed red blood cells (RBCs), as her hemoglobin had decreased to 7.3 g/dL. On hospital day 3, a colonoscopy was done that showed blood clots in the ascending colon but was otherwise normal. The patient had ongoing abdominal pain, melena, and hematochezia, and continued to require blood transfusions every other day.

Esophageal varices were confirmed on EGD. However, no high‐risk stigmata were seen. Findings that suggest either recent bleeding or are risk factors for subsequent bleeding include large size of the varices, nipple sign referring to a protruding vessel from an underlying varix, or red wale sign, referring to a longitudinal red streak on a varix. The lack of evidence for an esophageal, gastric, or duodenal bleeding source correlates with lack of clinical signs of upper GI tract hemorrhage such as hematemesis or coffee ground emesis. Because the colonoscopy also did not identify a bleeding source, the bleeding remains unexplained. The absence of significant abnormalities in liver function or liver inflammation labs suggests that the patient does not have advanced cirrhosis and supports the suspicion of a vascular cause of the portal hypertension. At this point, it would be most useful to obtain a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis.

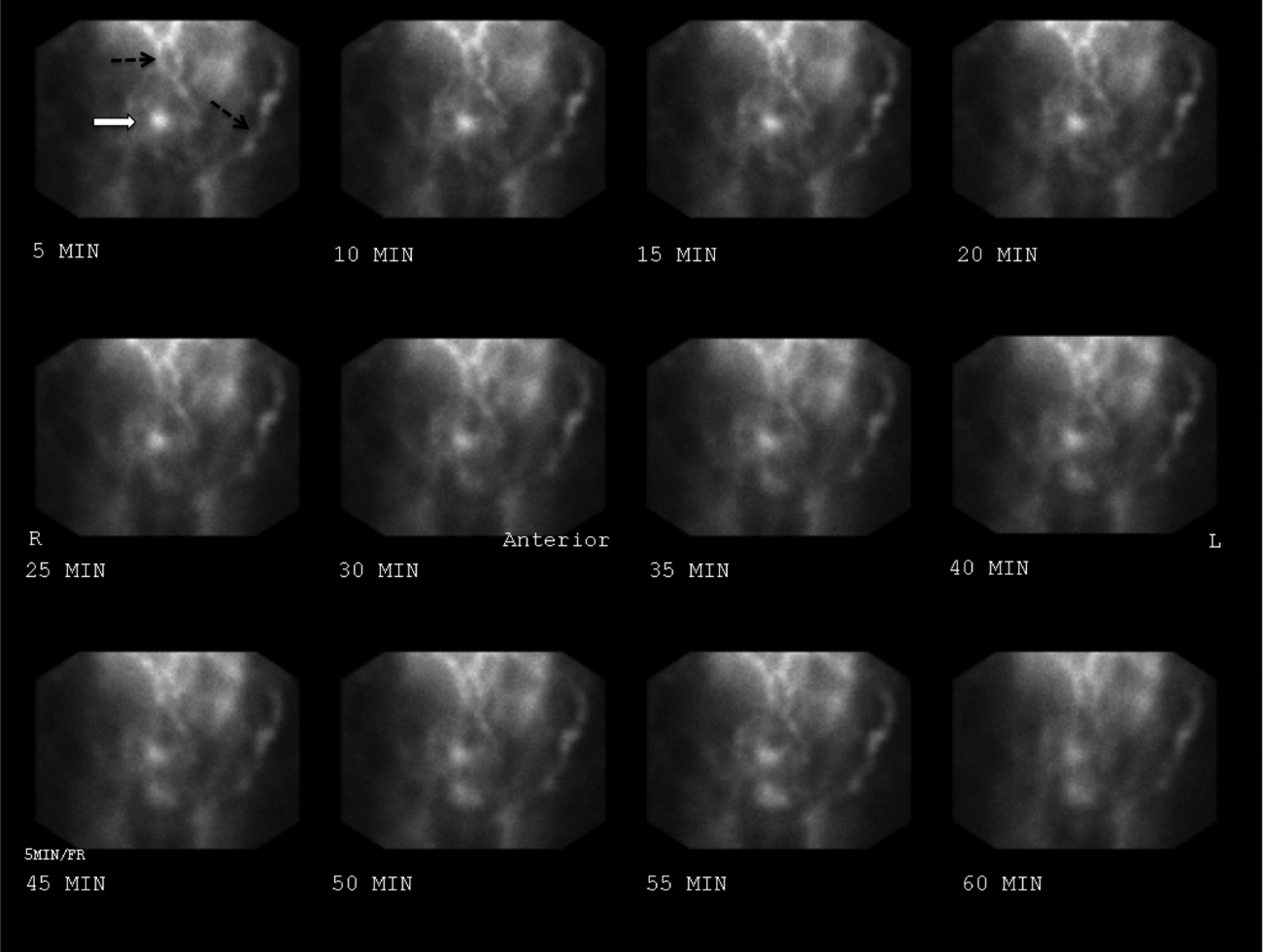

The patient continued to bleed, requiring a total of 7 U of packed RBCs over 7 days. On hospital day 4, a repeat EGD showed nonbleeding varices with a red wale sign that were banded. Despite this, the hemoglobin continued to drop. A technetium‐tagged RBC study showed a small area of subumbilical activity, which appeared to indicate transverse colonic or small bowel bleeding (Figure 1). A subsequent mesenteric angiogram failed to show active bleeding.

A red wale sign confers a higher risk of bleeding from esophageal varices. However, this finding can be subjective, and the endoscopist must individualize the decision for banding based on the size and appearance of the varices. It was reasonable to proceed with banding this time because the varices were large, had a red wale sign, and there was otherwise unexplained ongoing bleeding. Because her hemoglobin continued to drop after the banding and a tagged RBC study best localized the bleeding to the small intestine or transverse colon, it is unlikely that the varices are the primary source of bleeding. It is not surprising that the mesenteric angiogram did not show a source of bleeding, because this study requires active bleeding at a sufficient rate to radiographically identify the source.

The leading diagnosis remains an as yet uncharacterized small bowel bleeding source related to mesenteric thrombotic disease. Cross‐sectional imaging with IV contrast to identify significant vascular occlusion should be the next diagnostic step. Capsule endoscopy would be a more expensive and time‐consuming option, and although this could reveal the source of bleeding, it might not characterize the underlying vascular nature of the problem.

Due to persistent abdominal pain, a CT without intravenous contrast was done on hospital day 10. This showed extensive collateral vessels along the chest and abdominal wall with a distended azygos vein. The study was otherwise unrevealing. Her bloody stools cleared, so she was discharged with a plan for capsule endoscopy and outpatient follow‐up with her gastroenterologist. On the day of discharge (hospital day 11), hemoglobin was 7.5 g/dL and she received an eighth unit of packed RBCs. Overt bleeding was absent.

As an outpatient, intermittent hematochezia and melena recurred. The capsule endoscopy showed active bleeding approximately 45 minutes after the capsule exited the stomach. The lesion was not precisely located or characterized, but was believed to be in the distal small bowel.

The capsule finding supports the growing body of evidence implicating a small bowel source of bleeding. Furthermore, the ongoing but slow rate of blood loss makes a venous bleed more likely than an arterial bleed. A CT scan was performed prior to capsule study, but this was done without intravenous contrast. The brief description of the CT findings emphasizes the subcutaneous venous changes; a contraindication to IV contrast is not mentioned. Certainly IV contrast would have been very helpful to characterize the mesenteric arterial and venous vasculature. If there is no contraindication, a repeat CT scan with IV contrast should be performed. If there is a contraindication to IV contrast, it would be beneficial to revisit the noncontrast study with the specific purpose of searching for clues suggesting mesenteric or portal thrombosis. If the source still remains unclear, the next steps should be to perform push enteroscopy to assess the small intestine from the luminal side and magnetic resonance angiogram with venous phase imaging (or CT venogram if there is no contraindication to contrast) to evaluate the venous circulation.

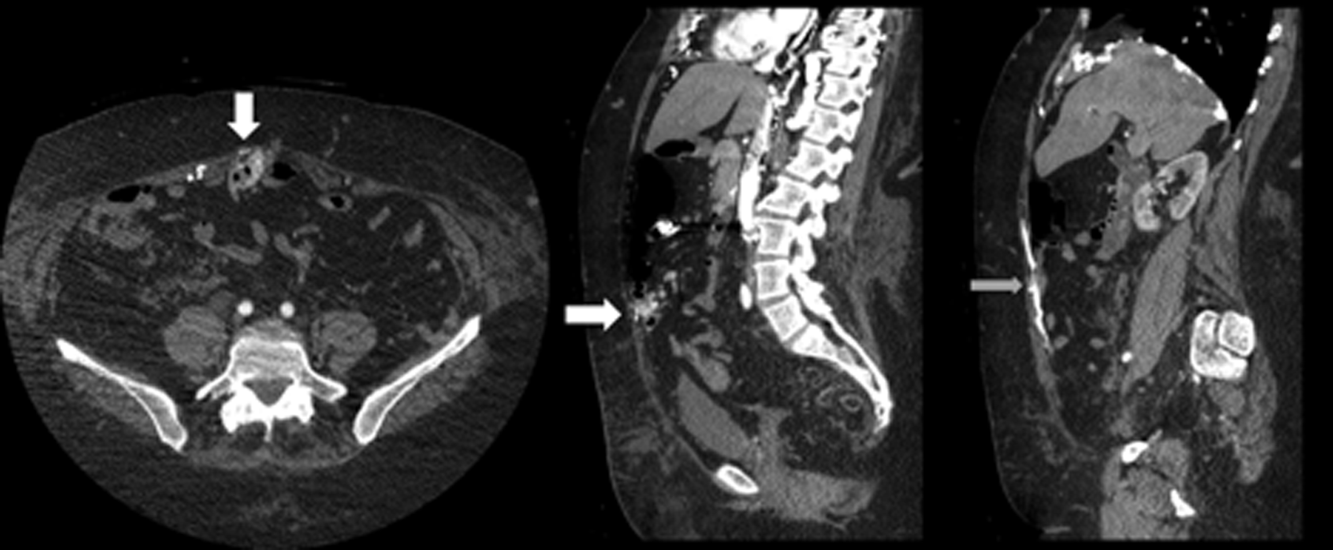

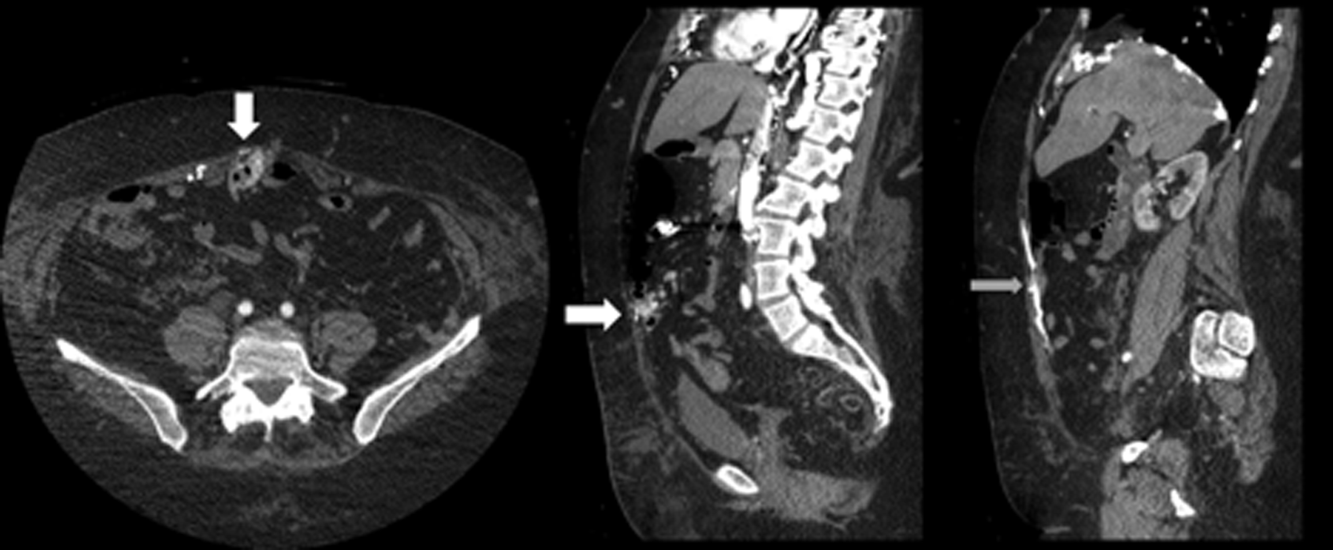

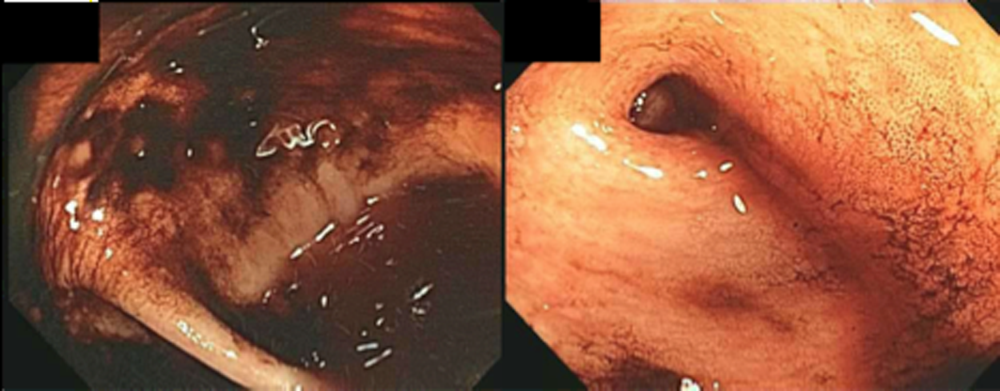

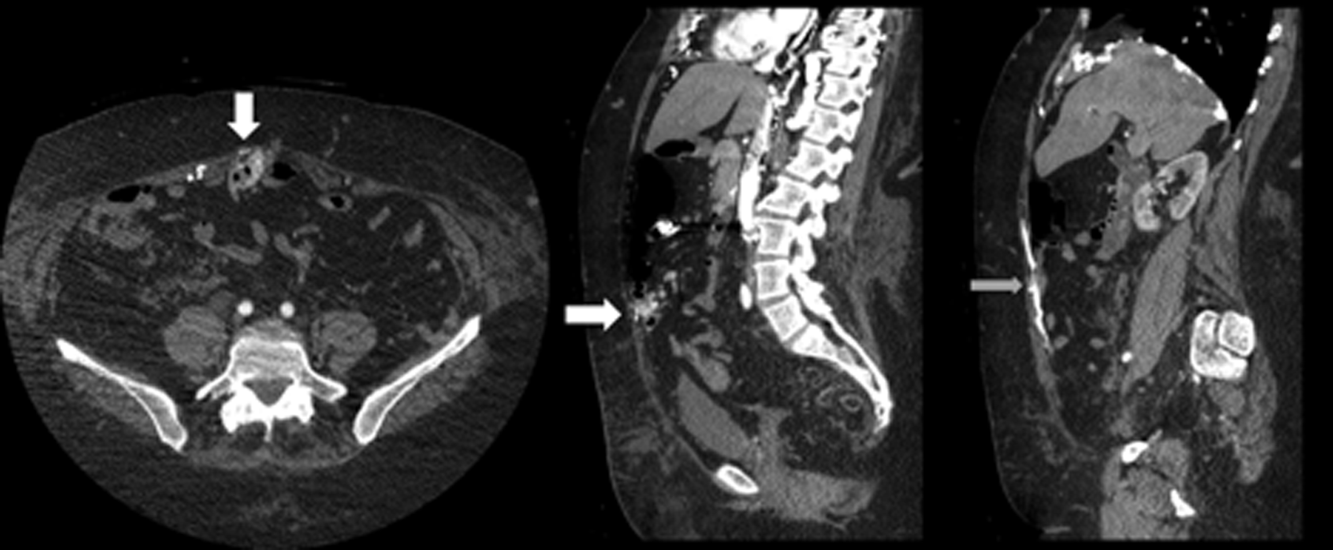

The patient was readmitted 9 days after discharge with persistent melena and hematochezia. Her hemoglobin was 7.2 g/dL. Given the lack of a diagnosis, the patient was transferred to a tertiary care hospital, where a second colonoscopy and mesenteric angiogram were negative for bleeding. Small bowel enteroscopy showed no source of bleeding up to 60 cm past the pylorus. A third colonoscopy was performed due to recurrent bleeding; this showed a large amount of dark blood and clots throughout the entire colon including the cecum (Figure 2). After copious irrigation, the underlying mucosa was seen to be normal. At this point, a CT angiogram with both venous and arterial phases was done due to the high suspicion for a distal jejunal bleeding source. The CT angiogram showed numerous venous collaterals encasing a loop of midsmall bowel demonstrating progressive submucosal venous enhancement. In addition, a venous collateral ran down the right side of the sternum to the infraumbilical area and drained through the encasing collaterals into the portal venous system (Figure 3). The CT scan also revealed IVC obstruction below the distal IVC filter and an enlarged portal vein measuring 18 mm (normal <12 mm).

The CT angiogram provides much‐needed clarity. The continued bleeding is likely due to ectopic varices in the small bowel. The venous phase of the CT angiogram shows thrombosis of key venous structures and evidence of a dilated portal vein (indicating portal hypertension) leading to ectopic varices in the abdominal wall and jejunum. Given the prior studies that suggest a small bowel source of bleeding, jejunal varices are the most likely cause of recurrent GI bleeding in this patient.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy. Loops of small bowel were found to be adherent to the hysterectomy scar. There were many venous collaterals from the abdominal wall to these loops of bowel, dilating the veins both in intestinal walls and those in the adjacent mesentery. After clamping these veins, the small bowel was detached from the abdominal wall. On unclamping, the collaterals bled with a high venous pressure. Because these systemic‐portal shunts were responsible for the bleeding, the collaterals were sutured, stopping the bleeding. Thus, partial small bowel resection was not necessary. Postoperatively, her bleeding resolved completely and she maintained normal hemoglobin at 1‐year follow‐up.

COMMENTARY

The axiom common ailments are encountered most frequently underpins the classical stepwise approach to GI bleeding. First, a focused history helps localize the source of bleeding to the upper or lower GI tract. Next, endoscopy is performed to identify and treat the cause of bleeding. Finally, advanced tests such as angiography and capsule endoscopy are performed if needed. For this patient, following the usual algorithm failed to make the diagnosis or stop the bleeding. Despite historical and examination features suggesting that her case fell outside of the common patterns of GI bleeding, this patient underwent 3 upper endoscopies, 3 colonoscopies, a capsule endoscopy, a technetium‐tagged RBC study, 2 mesenteric angiograms, and a noncontrast CT scan before the study that was ultimately diagnostic was performed. The clinicians caring for this patient struggled to incorporate the atypical features of her history and presentation and failed to take an earlier detour from the usual algorithm. Instead, the same studies that had not previously led to the diagnosis were repeated multiple times.

Ectopic varices are enlarged portosystemic venous collaterals located anywhere outside the gastroesophageal region.[1] They occur in the setting of portal hypertension, surgical procedures involving abdominal viscera and vasculature, and venous occlusion. Ectopic varices account for 4% to 5% of all variceal bleeding episodes.[1] The most common sites include the anorectal junction (44%), duodenum (17%33%), jejunum/emleum (5%17%), colon (3.5%14%), and sites of previous abdominal surgery.[2, 3] Ectopic varices can cause either luminal or extraluminal (i.e., peritoneal) bleeding.[3] Luminal bleeding, seen in this case, is caused by venous protrusion into the submucosa. Ectopic varices present as a slow venous ooze, which explains this patient's ongoing requirement for recurrent blood transfusions.[4]

In this patient, submucosal ectopic varices developed as a result of a combination of known risk factors: portal hypertension in the setting of chronic venous occlusion from her hypercoagulability and a history of abdominal surgery (hysterectomy). [5] The apposition of her abdominal wall structures (drained by the systemic veins) to the bowel (drained by the portal veins) resulted in adhesion formation, detour of venous flow, collateralization, and submucosal varix formation.[1, 2, 6]

The key diagnostic study for this patient was a CT angiogram, with both arterial and venous phases. The prior 2 mesenteric angiograms had been limited to the arterial phase, which had missed identifying the venous abnormalities altogether. This highlights an important lesson from this case: contrast‐enhanced CT may have a higher yield in diagnosing ectopic varices compared to repeated endoscopiesespecially when captured in the late venous phaseand should strongly be considered for unexplained bleeding in patients with stigmata of liver disease or portal hypertension.[7, 8] Another clue for ectopic varices in a bleeding patient are nonbleeding esophageal or gastric varices, as was the case in this patient.[9]

The initial management of ectopic varices is similar to bleeding secondary to esophageal varices.[1] Definitive treatment includes endoscopic embolization or ligation, interventional radiological procedures such as portosystemic shunting or percutaneous embolization, and exploratory laparotomy to either resect the segment of bowel that is the source of bleeding or to decompress the collaterals surgically.[9] Although endoscopic ligation has been shown to have a lower rebleeding rate and mortality compared to endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in patients with esophageal varices, the data are too sparse in jejunal varices to recommend 1 treatment over another. Both have been used successfully either alone or in combination with each other, and can be useful alternatives for patients who are unable to undergo laparotomy.[9]

Diagnostic errors due to cognitive biases can be avoided by following diagnostic algorithms. However, over‐reliance on algorithms can result in vertical line failure, a form of cognitive bias in which the clinician subconsciously adheres to an inflexible diagnostic approach.[10] To overcome this bias, clinicians need to think laterally and consider alternative diagnoses when algorithms do not lead to expected outcomes. This case highlights the challenges of knowing when to break free of conventional approaches and the rewards of taking a well‐chosen detour that leads to the diagnosis.

KEY POINTS

- Recurrent, occult gastrointestinal bleeding should raise concern for a small bowel source, and clinicians may need to take a detour away from the usual workup to arrive at a diagnosis.

- CT angiography of the abdomen and pelvis may miss venous sources of bleeding, unless a venous phase is specifically requested.

- Ectopic varices can occur in patients with portal hypertension who have had a history of abdominal surgery; these patients can develop venous collaterals for decompression into the systemic circulation through the abdominal wall.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , . Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:322–334.

- , , . Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology. 1998;28:1154–1158.

- , , , et al. Current status of ectopic varices in Japan: results of a survey by the Japan Society for Portal Hypertension. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:763–766.

- , , . Stomal Varices: Management with decompression TIPS and transvenous obliteration or sclerosis. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;16:126–134.

- , , , et al. Jejunal varices as a cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:514–517.

- , . Ectopic varices in portal hypertension. Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;14:105–121.

- , , , et al. Ectopic varices in portal hypertension: computed tomographic angiography instead of repeated endoscopies for diagnosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:620–622.

- , , , et al. ACR appropriateness criteria. Radiologic management of lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2011. Available at: http://www.acr.org/Quality‐Safety/Appropriateness‐Criteria/∼/media/5F9CB95C164E4DA19DCBCFBBA790BB3C.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- , . Diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Gastrointest Interv. 2012;1:3–10.

- . Achieving quality in clinical decision making: cognitive strategies and detection of bias. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1184–1204.

A 60‐year‐old woman presented to a community hospital's emergency department with 4 days of right‐sided abdominal pain and multiple episodes of black stools. She reported nausea without vomiting. She denied light‐headedness, chest pain, or shortness of breath. She also denied difficulty in swallowing, weight loss, jaundice, or other bleeding.

The first priority when assessing a patient with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is to ensure hemodynamic stability. Next, it is important to carefully characterize the stools to help narrow the differential diagnosis. As blood is a cathartic, frequent, loose, and black stools suggest vigorous bleeding. It is essential to establish that the stools are actually black, as some patients will mistake dark brown stools for melena. Using a visual aid like a black pen or shoes as a point of reference can help the patient differentiate between dark stool and melena. It is also important to obtain a thorough medication history because iron supplements or bismuth‐containing remedies can turn stool black. The use of any antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants should also be noted. The right‐sided abdominal pain should be characterized by establishing the frequency, severity, and association with eating, movement, and position. For this patient's presentation, increased pain with eating would rapidly heighten concern for mesenteric ischemia.

The patient reported having 1 to 2 semiformed, tarry, black bowel movements per day. The night prior to admission she had passed some bright red blood along with the melena. The abdominal pain had increased gradually over 4 days, was dull, constant, did not radiate, and there were no evident aggravating or relieving factors. She rated the pain as 4 out of 10 in intensity, worst in her right upper quadrant.

Her past medical history was notable for recurrent deep venous thromboses and pulmonary emboli that had occurred even while on oral anticoagulation. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters had twice been placed many years prior; anticoagulation had been subsequently discontinued. Additionally, she was known to have chronic superior vena cava (SVC) occlusion, presumably related to hypercoagulability. Previous evaluation had identified only hyperhomocysteinemia as a risk factor for recurrent thromboses. Other medical problems included hemorrhoids, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and asthma. Her only surgical history was an abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy many years ago for nonmalignant disease. Home medications were omeprazole, ranitidine, albuterol, and fluticasone‐salmeterol. She denied using nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, aspirin, or any dietary supplements. She denied smoking, alcohol, or recreational drug use.

Because melena is confirmed, an upper GI tract bleeding source is most likely. The more recent appearance of bright red blood is concerning for acceleration of bleeding, or may point to a distal small bowel or right colonic source. Given the history of thromboembolic disease and likely underlying hypercoagulability, vascular occlusion is a leading possibility. Thus, mesenteric arterial insufficiency or mesenteric venous thrombosis should be considered, even though the patient does not report the characteristic postprandial exacerbation of pain. Ischemic colitis due to arterial insufficiency typically presents with severe, acute pain, with or without hematochezia. This syndrome is typically manifested in vascular watershed areas such as the splenic flexure, but can also affect the right colon. Mesenteric venous thrombosis is a rare condition that most often occurs in patients with hypercoagulability. Patients present with variable degrees of abdominal pain and often with GI bleeding. Finally, portal venous thrombosis may be seen alongside thromboses of other mesenteric veins or may occur independently. Portal hypertension due to portal vein thrombosis can result in esophageal and/or gastric varices. Although variceal bleeding classically presents with dramatic hematemesis, the absence of hematemesis does not rule out a variceal bleed in this patient.

On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 37.1C with a pulse of 90 beats per minute and blood pressure of 161/97 mm Hg. Orthostatics were not performed. No blood was seen on nasal and oropharyngeal exam. Respiratory and cardiovascular exams were normal. On abdominal exam, there was tenderness to palpation of the right upper quadrant without rebound or guarding. The spleen and the liver were not palpable. There was a lower midline incisional scar. Rectal exam revealed nonbleeding hemorrhoids and heme‐positive stool without gross blood. Bilateral lower extremities had trace pitting edema, hyperpigmentation, and superficial venous varicosities. On skin exam, there were distended subcutaneous veins radiating outward from around the umbilicus as well as prominent subcutaneous venous collaterals over the chest and lateral abdomen.

The collateral veins over the chest and lateral abdomen are consistent with central venous obstruction from the patient's known SVC thrombus. However, the presence of paraumbilical venous collaterals (caput medusa) is highly suggestive of portal hypertension. This evidence, in addition to the known central venous occlusion and history of thromboembolic disease, raises the suspicion for mesenteric thrombosis as a cause of her bleeding and pain. The first diagnostic procedure should be an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to identify and potentially treat the source of bleeding, whether it is portal hypertension related (portal gastropathy, variceal bleed) or from a more common cause (peptic ulcer disease, stress gastritis). If the EGD is not diagnostic, the next step should be to obtain computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast. In many patients with GI bleed, a colonoscopy would typically be performed as the next diagnostic study after EGD. However, in this patient, a CT scan is likely to be of higher yield because it could help assess the mesenteric and portal vessels for patency and characterize the appearance of the small intestine and colon. Depending on the findings of the CT, additional dedicated vascular diagnostics might be needed.

Hemoglobin was 8.5 g/dL (12.4 g/dL 6 weeks prior) with a normal mean corpuscular volume and red cell distribution. The white cell count was normal, and the platelet count was 142,000/mm3. The blood urea nitrogen was 27 mg/dL, with a creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL. Routine chemistries, liver enzymes, bilirubin, and coagulation parameters were normal. Ferritin was 15 ng/mL (normal: 15200 ng/mL).

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. An EGD revealed a hiatal hernia and grade II nonbleeding esophageal varices with normal=appearing stomach and duodenum. The varices did not have stigmata of a recent bleed and were not ligated. The patient continued to bleed and received 2 U of packed red blood cells (RBCs), as her hemoglobin had decreased to 7.3 g/dL. On hospital day 3, a colonoscopy was done that showed blood clots in the ascending colon but was otherwise normal. The patient had ongoing abdominal pain, melena, and hematochezia, and continued to require blood transfusions every other day.

Esophageal varices were confirmed on EGD. However, no high‐risk stigmata were seen. Findings that suggest either recent bleeding or are risk factors for subsequent bleeding include large size of the varices, nipple sign referring to a protruding vessel from an underlying varix, or red wale sign, referring to a longitudinal red streak on a varix. The lack of evidence for an esophageal, gastric, or duodenal bleeding source correlates with lack of clinical signs of upper GI tract hemorrhage such as hematemesis or coffee ground emesis. Because the colonoscopy also did not identify a bleeding source, the bleeding remains unexplained. The absence of significant abnormalities in liver function or liver inflammation labs suggests that the patient does not have advanced cirrhosis and supports the suspicion of a vascular cause of the portal hypertension. At this point, it would be most useful to obtain a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis.

The patient continued to bleed, requiring a total of 7 U of packed RBCs over 7 days. On hospital day 4, a repeat EGD showed nonbleeding varices with a red wale sign that were banded. Despite this, the hemoglobin continued to drop. A technetium‐tagged RBC study showed a small area of subumbilical activity, which appeared to indicate transverse colonic or small bowel bleeding (Figure 1). A subsequent mesenteric angiogram failed to show active bleeding.

A red wale sign confers a higher risk of bleeding from esophageal varices. However, this finding can be subjective, and the endoscopist must individualize the decision for banding based on the size and appearance of the varices. It was reasonable to proceed with banding this time because the varices were large, had a red wale sign, and there was otherwise unexplained ongoing bleeding. Because her hemoglobin continued to drop after the banding and a tagged RBC study best localized the bleeding to the small intestine or transverse colon, it is unlikely that the varices are the primary source of bleeding. It is not surprising that the mesenteric angiogram did not show a source of bleeding, because this study requires active bleeding at a sufficient rate to radiographically identify the source.

The leading diagnosis remains an as yet uncharacterized small bowel bleeding source related to mesenteric thrombotic disease. Cross‐sectional imaging with IV contrast to identify significant vascular occlusion should be the next diagnostic step. Capsule endoscopy would be a more expensive and time‐consuming option, and although this could reveal the source of bleeding, it might not characterize the underlying vascular nature of the problem.

Due to persistent abdominal pain, a CT without intravenous contrast was done on hospital day 10. This showed extensive collateral vessels along the chest and abdominal wall with a distended azygos vein. The study was otherwise unrevealing. Her bloody stools cleared, so she was discharged with a plan for capsule endoscopy and outpatient follow‐up with her gastroenterologist. On the day of discharge (hospital day 11), hemoglobin was 7.5 g/dL and she received an eighth unit of packed RBCs. Overt bleeding was absent.

As an outpatient, intermittent hematochezia and melena recurred. The capsule endoscopy showed active bleeding approximately 45 minutes after the capsule exited the stomach. The lesion was not precisely located or characterized, but was believed to be in the distal small bowel.

The capsule finding supports the growing body of evidence implicating a small bowel source of bleeding. Furthermore, the ongoing but slow rate of blood loss makes a venous bleed more likely than an arterial bleed. A CT scan was performed prior to capsule study, but this was done without intravenous contrast. The brief description of the CT findings emphasizes the subcutaneous venous changes; a contraindication to IV contrast is not mentioned. Certainly IV contrast would have been very helpful to characterize the mesenteric arterial and venous vasculature. If there is no contraindication, a repeat CT scan with IV contrast should be performed. If there is a contraindication to IV contrast, it would be beneficial to revisit the noncontrast study with the specific purpose of searching for clues suggesting mesenteric or portal thrombosis. If the source still remains unclear, the next steps should be to perform push enteroscopy to assess the small intestine from the luminal side and magnetic resonance angiogram with venous phase imaging (or CT venogram if there is no contraindication to contrast) to evaluate the venous circulation.

The patient was readmitted 9 days after discharge with persistent melena and hematochezia. Her hemoglobin was 7.2 g/dL. Given the lack of a diagnosis, the patient was transferred to a tertiary care hospital, where a second colonoscopy and mesenteric angiogram were negative for bleeding. Small bowel enteroscopy showed no source of bleeding up to 60 cm past the pylorus. A third colonoscopy was performed due to recurrent bleeding; this showed a large amount of dark blood and clots throughout the entire colon including the cecum (Figure 2). After copious irrigation, the underlying mucosa was seen to be normal. At this point, a CT angiogram with both venous and arterial phases was done due to the high suspicion for a distal jejunal bleeding source. The CT angiogram showed numerous venous collaterals encasing a loop of midsmall bowel demonstrating progressive submucosal venous enhancement. In addition, a venous collateral ran down the right side of the sternum to the infraumbilical area and drained through the encasing collaterals into the portal venous system (Figure 3). The CT scan also revealed IVC obstruction below the distal IVC filter and an enlarged portal vein measuring 18 mm (normal <12 mm).

The CT angiogram provides much‐needed clarity. The continued bleeding is likely due to ectopic varices in the small bowel. The venous phase of the CT angiogram shows thrombosis of key venous structures and evidence of a dilated portal vein (indicating portal hypertension) leading to ectopic varices in the abdominal wall and jejunum. Given the prior studies that suggest a small bowel source of bleeding, jejunal varices are the most likely cause of recurrent GI bleeding in this patient.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy. Loops of small bowel were found to be adherent to the hysterectomy scar. There were many venous collaterals from the abdominal wall to these loops of bowel, dilating the veins both in intestinal walls and those in the adjacent mesentery. After clamping these veins, the small bowel was detached from the abdominal wall. On unclamping, the collaterals bled with a high venous pressure. Because these systemic‐portal shunts were responsible for the bleeding, the collaterals were sutured, stopping the bleeding. Thus, partial small bowel resection was not necessary. Postoperatively, her bleeding resolved completely and she maintained normal hemoglobin at 1‐year follow‐up.

COMMENTARY

The axiom common ailments are encountered most frequently underpins the classical stepwise approach to GI bleeding. First, a focused history helps localize the source of bleeding to the upper or lower GI tract. Next, endoscopy is performed to identify and treat the cause of bleeding. Finally, advanced tests such as angiography and capsule endoscopy are performed if needed. For this patient, following the usual algorithm failed to make the diagnosis or stop the bleeding. Despite historical and examination features suggesting that her case fell outside of the common patterns of GI bleeding, this patient underwent 3 upper endoscopies, 3 colonoscopies, a capsule endoscopy, a technetium‐tagged RBC study, 2 mesenteric angiograms, and a noncontrast CT scan before the study that was ultimately diagnostic was performed. The clinicians caring for this patient struggled to incorporate the atypical features of her history and presentation and failed to take an earlier detour from the usual algorithm. Instead, the same studies that had not previously led to the diagnosis were repeated multiple times.

Ectopic varices are enlarged portosystemic venous collaterals located anywhere outside the gastroesophageal region.[1] They occur in the setting of portal hypertension, surgical procedures involving abdominal viscera and vasculature, and venous occlusion. Ectopic varices account for 4% to 5% of all variceal bleeding episodes.[1] The most common sites include the anorectal junction (44%), duodenum (17%33%), jejunum/emleum (5%17%), colon (3.5%14%), and sites of previous abdominal surgery.[2, 3] Ectopic varices can cause either luminal or extraluminal (i.e., peritoneal) bleeding.[3] Luminal bleeding, seen in this case, is caused by venous protrusion into the submucosa. Ectopic varices present as a slow venous ooze, which explains this patient's ongoing requirement for recurrent blood transfusions.[4]

In this patient, submucosal ectopic varices developed as a result of a combination of known risk factors: portal hypertension in the setting of chronic venous occlusion from her hypercoagulability and a history of abdominal surgery (hysterectomy). [5] The apposition of her abdominal wall structures (drained by the systemic veins) to the bowel (drained by the portal veins) resulted in adhesion formation, detour of venous flow, collateralization, and submucosal varix formation.[1, 2, 6]

The key diagnostic study for this patient was a CT angiogram, with both arterial and venous phases. The prior 2 mesenteric angiograms had been limited to the arterial phase, which had missed identifying the venous abnormalities altogether. This highlights an important lesson from this case: contrast‐enhanced CT may have a higher yield in diagnosing ectopic varices compared to repeated endoscopiesespecially when captured in the late venous phaseand should strongly be considered for unexplained bleeding in patients with stigmata of liver disease or portal hypertension.[7, 8] Another clue for ectopic varices in a bleeding patient are nonbleeding esophageal or gastric varices, as was the case in this patient.[9]

The initial management of ectopic varices is similar to bleeding secondary to esophageal varices.[1] Definitive treatment includes endoscopic embolization or ligation, interventional radiological procedures such as portosystemic shunting or percutaneous embolization, and exploratory laparotomy to either resect the segment of bowel that is the source of bleeding or to decompress the collaterals surgically.[9] Although endoscopic ligation has been shown to have a lower rebleeding rate and mortality compared to endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in patients with esophageal varices, the data are too sparse in jejunal varices to recommend 1 treatment over another. Both have been used successfully either alone or in combination with each other, and can be useful alternatives for patients who are unable to undergo laparotomy.[9]

Diagnostic errors due to cognitive biases can be avoided by following diagnostic algorithms. However, over‐reliance on algorithms can result in vertical line failure, a form of cognitive bias in which the clinician subconsciously adheres to an inflexible diagnostic approach.[10] To overcome this bias, clinicians need to think laterally and consider alternative diagnoses when algorithms do not lead to expected outcomes. This case highlights the challenges of knowing when to break free of conventional approaches and the rewards of taking a well‐chosen detour that leads to the diagnosis.

KEY POINTS

- Recurrent, occult gastrointestinal bleeding should raise concern for a small bowel source, and clinicians may need to take a detour away from the usual workup to arrive at a diagnosis.

- CT angiography of the abdomen and pelvis may miss venous sources of bleeding, unless a venous phase is specifically requested.

- Ectopic varices can occur in patients with portal hypertension who have had a history of abdominal surgery; these patients can develop venous collaterals for decompression into the systemic circulation through the abdominal wall.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

A 60‐year‐old woman presented to a community hospital's emergency department with 4 days of right‐sided abdominal pain and multiple episodes of black stools. She reported nausea without vomiting. She denied light‐headedness, chest pain, or shortness of breath. She also denied difficulty in swallowing, weight loss, jaundice, or other bleeding.

The first priority when assessing a patient with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is to ensure hemodynamic stability. Next, it is important to carefully characterize the stools to help narrow the differential diagnosis. As blood is a cathartic, frequent, loose, and black stools suggest vigorous bleeding. It is essential to establish that the stools are actually black, as some patients will mistake dark brown stools for melena. Using a visual aid like a black pen or shoes as a point of reference can help the patient differentiate between dark stool and melena. It is also important to obtain a thorough medication history because iron supplements or bismuth‐containing remedies can turn stool black. The use of any antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants should also be noted. The right‐sided abdominal pain should be characterized by establishing the frequency, severity, and association with eating, movement, and position. For this patient's presentation, increased pain with eating would rapidly heighten concern for mesenteric ischemia.

The patient reported having 1 to 2 semiformed, tarry, black bowel movements per day. The night prior to admission she had passed some bright red blood along with the melena. The abdominal pain had increased gradually over 4 days, was dull, constant, did not radiate, and there were no evident aggravating or relieving factors. She rated the pain as 4 out of 10 in intensity, worst in her right upper quadrant.

Her past medical history was notable for recurrent deep venous thromboses and pulmonary emboli that had occurred even while on oral anticoagulation. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters had twice been placed many years prior; anticoagulation had been subsequently discontinued. Additionally, she was known to have chronic superior vena cava (SVC) occlusion, presumably related to hypercoagulability. Previous evaluation had identified only hyperhomocysteinemia as a risk factor for recurrent thromboses. Other medical problems included hemorrhoids, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and asthma. Her only surgical history was an abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy many years ago for nonmalignant disease. Home medications were omeprazole, ranitidine, albuterol, and fluticasone‐salmeterol. She denied using nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, aspirin, or any dietary supplements. She denied smoking, alcohol, or recreational drug use.

Because melena is confirmed, an upper GI tract bleeding source is most likely. The more recent appearance of bright red blood is concerning for acceleration of bleeding, or may point to a distal small bowel or right colonic source. Given the history of thromboembolic disease and likely underlying hypercoagulability, vascular occlusion is a leading possibility. Thus, mesenteric arterial insufficiency or mesenteric venous thrombosis should be considered, even though the patient does not report the characteristic postprandial exacerbation of pain. Ischemic colitis due to arterial insufficiency typically presents with severe, acute pain, with or without hematochezia. This syndrome is typically manifested in vascular watershed areas such as the splenic flexure, but can also affect the right colon. Mesenteric venous thrombosis is a rare condition that most often occurs in patients with hypercoagulability. Patients present with variable degrees of abdominal pain and often with GI bleeding. Finally, portal venous thrombosis may be seen alongside thromboses of other mesenteric veins or may occur independently. Portal hypertension due to portal vein thrombosis can result in esophageal and/or gastric varices. Although variceal bleeding classically presents with dramatic hematemesis, the absence of hematemesis does not rule out a variceal bleed in this patient.

On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 37.1C with a pulse of 90 beats per minute and blood pressure of 161/97 mm Hg. Orthostatics were not performed. No blood was seen on nasal and oropharyngeal exam. Respiratory and cardiovascular exams were normal. On abdominal exam, there was tenderness to palpation of the right upper quadrant without rebound or guarding. The spleen and the liver were not palpable. There was a lower midline incisional scar. Rectal exam revealed nonbleeding hemorrhoids and heme‐positive stool without gross blood. Bilateral lower extremities had trace pitting edema, hyperpigmentation, and superficial venous varicosities. On skin exam, there were distended subcutaneous veins radiating outward from around the umbilicus as well as prominent subcutaneous venous collaterals over the chest and lateral abdomen.

The collateral veins over the chest and lateral abdomen are consistent with central venous obstruction from the patient's known SVC thrombus. However, the presence of paraumbilical venous collaterals (caput medusa) is highly suggestive of portal hypertension. This evidence, in addition to the known central venous occlusion and history of thromboembolic disease, raises the suspicion for mesenteric thrombosis as a cause of her bleeding and pain. The first diagnostic procedure should be an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to identify and potentially treat the source of bleeding, whether it is portal hypertension related (portal gastropathy, variceal bleed) or from a more common cause (peptic ulcer disease, stress gastritis). If the EGD is not diagnostic, the next step should be to obtain computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast. In many patients with GI bleed, a colonoscopy would typically be performed as the next diagnostic study after EGD. However, in this patient, a CT scan is likely to be of higher yield because it could help assess the mesenteric and portal vessels for patency and characterize the appearance of the small intestine and colon. Depending on the findings of the CT, additional dedicated vascular diagnostics might be needed.

Hemoglobin was 8.5 g/dL (12.4 g/dL 6 weeks prior) with a normal mean corpuscular volume and red cell distribution. The white cell count was normal, and the platelet count was 142,000/mm3. The blood urea nitrogen was 27 mg/dL, with a creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL. Routine chemistries, liver enzymes, bilirubin, and coagulation parameters were normal. Ferritin was 15 ng/mL (normal: 15200 ng/mL).

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. An EGD revealed a hiatal hernia and grade II nonbleeding esophageal varices with normal=appearing stomach and duodenum. The varices did not have stigmata of a recent bleed and were not ligated. The patient continued to bleed and received 2 U of packed red blood cells (RBCs), as her hemoglobin had decreased to 7.3 g/dL. On hospital day 3, a colonoscopy was done that showed blood clots in the ascending colon but was otherwise normal. The patient had ongoing abdominal pain, melena, and hematochezia, and continued to require blood transfusions every other day.

Esophageal varices were confirmed on EGD. However, no high‐risk stigmata were seen. Findings that suggest either recent bleeding or are risk factors for subsequent bleeding include large size of the varices, nipple sign referring to a protruding vessel from an underlying varix, or red wale sign, referring to a longitudinal red streak on a varix. The lack of evidence for an esophageal, gastric, or duodenal bleeding source correlates with lack of clinical signs of upper GI tract hemorrhage such as hematemesis or coffee ground emesis. Because the colonoscopy also did not identify a bleeding source, the bleeding remains unexplained. The absence of significant abnormalities in liver function or liver inflammation labs suggests that the patient does not have advanced cirrhosis and supports the suspicion of a vascular cause of the portal hypertension. At this point, it would be most useful to obtain a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis.

The patient continued to bleed, requiring a total of 7 U of packed RBCs over 7 days. On hospital day 4, a repeat EGD showed nonbleeding varices with a red wale sign that were banded. Despite this, the hemoglobin continued to drop. A technetium‐tagged RBC study showed a small area of subumbilical activity, which appeared to indicate transverse colonic or small bowel bleeding (Figure 1). A subsequent mesenteric angiogram failed to show active bleeding.

A red wale sign confers a higher risk of bleeding from esophageal varices. However, this finding can be subjective, and the endoscopist must individualize the decision for banding based on the size and appearance of the varices. It was reasonable to proceed with banding this time because the varices were large, had a red wale sign, and there was otherwise unexplained ongoing bleeding. Because her hemoglobin continued to drop after the banding and a tagged RBC study best localized the bleeding to the small intestine or transverse colon, it is unlikely that the varices are the primary source of bleeding. It is not surprising that the mesenteric angiogram did not show a source of bleeding, because this study requires active bleeding at a sufficient rate to radiographically identify the source.

The leading diagnosis remains an as yet uncharacterized small bowel bleeding source related to mesenteric thrombotic disease. Cross‐sectional imaging with IV contrast to identify significant vascular occlusion should be the next diagnostic step. Capsule endoscopy would be a more expensive and time‐consuming option, and although this could reveal the source of bleeding, it might not characterize the underlying vascular nature of the problem.

Due to persistent abdominal pain, a CT without intravenous contrast was done on hospital day 10. This showed extensive collateral vessels along the chest and abdominal wall with a distended azygos vein. The study was otherwise unrevealing. Her bloody stools cleared, so she was discharged with a plan for capsule endoscopy and outpatient follow‐up with her gastroenterologist. On the day of discharge (hospital day 11), hemoglobin was 7.5 g/dL and she received an eighth unit of packed RBCs. Overt bleeding was absent.

As an outpatient, intermittent hematochezia and melena recurred. The capsule endoscopy showed active bleeding approximately 45 minutes after the capsule exited the stomach. The lesion was not precisely located or characterized, but was believed to be in the distal small bowel.

The capsule finding supports the growing body of evidence implicating a small bowel source of bleeding. Furthermore, the ongoing but slow rate of blood loss makes a venous bleed more likely than an arterial bleed. A CT scan was performed prior to capsule study, but this was done without intravenous contrast. The brief description of the CT findings emphasizes the subcutaneous venous changes; a contraindication to IV contrast is not mentioned. Certainly IV contrast would have been very helpful to characterize the mesenteric arterial and venous vasculature. If there is no contraindication, a repeat CT scan with IV contrast should be performed. If there is a contraindication to IV contrast, it would be beneficial to revisit the noncontrast study with the specific purpose of searching for clues suggesting mesenteric or portal thrombosis. If the source still remains unclear, the next steps should be to perform push enteroscopy to assess the small intestine from the luminal side and magnetic resonance angiogram with venous phase imaging (or CT venogram if there is no contraindication to contrast) to evaluate the venous circulation.

The patient was readmitted 9 days after discharge with persistent melena and hematochezia. Her hemoglobin was 7.2 g/dL. Given the lack of a diagnosis, the patient was transferred to a tertiary care hospital, where a second colonoscopy and mesenteric angiogram were negative for bleeding. Small bowel enteroscopy showed no source of bleeding up to 60 cm past the pylorus. A third colonoscopy was performed due to recurrent bleeding; this showed a large amount of dark blood and clots throughout the entire colon including the cecum (Figure 2). After copious irrigation, the underlying mucosa was seen to be normal. At this point, a CT angiogram with both venous and arterial phases was done due to the high suspicion for a distal jejunal bleeding source. The CT angiogram showed numerous venous collaterals encasing a loop of midsmall bowel demonstrating progressive submucosal venous enhancement. In addition, a venous collateral ran down the right side of the sternum to the infraumbilical area and drained through the encasing collaterals into the portal venous system (Figure 3). The CT scan also revealed IVC obstruction below the distal IVC filter and an enlarged portal vein measuring 18 mm (normal <12 mm).

The CT angiogram provides much‐needed clarity. The continued bleeding is likely due to ectopic varices in the small bowel. The venous phase of the CT angiogram shows thrombosis of key venous structures and evidence of a dilated portal vein (indicating portal hypertension) leading to ectopic varices in the abdominal wall and jejunum. Given the prior studies that suggest a small bowel source of bleeding, jejunal varices are the most likely cause of recurrent GI bleeding in this patient.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy. Loops of small bowel were found to be adherent to the hysterectomy scar. There were many venous collaterals from the abdominal wall to these loops of bowel, dilating the veins both in intestinal walls and those in the adjacent mesentery. After clamping these veins, the small bowel was detached from the abdominal wall. On unclamping, the collaterals bled with a high venous pressure. Because these systemic‐portal shunts were responsible for the bleeding, the collaterals were sutured, stopping the bleeding. Thus, partial small bowel resection was not necessary. Postoperatively, her bleeding resolved completely and she maintained normal hemoglobin at 1‐year follow‐up.

COMMENTARY

The axiom common ailments are encountered most frequently underpins the classical stepwise approach to GI bleeding. First, a focused history helps localize the source of bleeding to the upper or lower GI tract. Next, endoscopy is performed to identify and treat the cause of bleeding. Finally, advanced tests such as angiography and capsule endoscopy are performed if needed. For this patient, following the usual algorithm failed to make the diagnosis or stop the bleeding. Despite historical and examination features suggesting that her case fell outside of the common patterns of GI bleeding, this patient underwent 3 upper endoscopies, 3 colonoscopies, a capsule endoscopy, a technetium‐tagged RBC study, 2 mesenteric angiograms, and a noncontrast CT scan before the study that was ultimately diagnostic was performed. The clinicians caring for this patient struggled to incorporate the atypical features of her history and presentation and failed to take an earlier detour from the usual algorithm. Instead, the same studies that had not previously led to the diagnosis were repeated multiple times.

Ectopic varices are enlarged portosystemic venous collaterals located anywhere outside the gastroesophageal region.[1] They occur in the setting of portal hypertension, surgical procedures involving abdominal viscera and vasculature, and venous occlusion. Ectopic varices account for 4% to 5% of all variceal bleeding episodes.[1] The most common sites include the anorectal junction (44%), duodenum (17%33%), jejunum/emleum (5%17%), colon (3.5%14%), and sites of previous abdominal surgery.[2, 3] Ectopic varices can cause either luminal or extraluminal (i.e., peritoneal) bleeding.[3] Luminal bleeding, seen in this case, is caused by venous protrusion into the submucosa. Ectopic varices present as a slow venous ooze, which explains this patient's ongoing requirement for recurrent blood transfusions.[4]

In this patient, submucosal ectopic varices developed as a result of a combination of known risk factors: portal hypertension in the setting of chronic venous occlusion from her hypercoagulability and a history of abdominal surgery (hysterectomy). [5] The apposition of her abdominal wall structures (drained by the systemic veins) to the bowel (drained by the portal veins) resulted in adhesion formation, detour of venous flow, collateralization, and submucosal varix formation.[1, 2, 6]

The key diagnostic study for this patient was a CT angiogram, with both arterial and venous phases. The prior 2 mesenteric angiograms had been limited to the arterial phase, which had missed identifying the venous abnormalities altogether. This highlights an important lesson from this case: contrast‐enhanced CT may have a higher yield in diagnosing ectopic varices compared to repeated endoscopiesespecially when captured in the late venous phaseand should strongly be considered for unexplained bleeding in patients with stigmata of liver disease or portal hypertension.[7, 8] Another clue for ectopic varices in a bleeding patient are nonbleeding esophageal or gastric varices, as was the case in this patient.[9]

The initial management of ectopic varices is similar to bleeding secondary to esophageal varices.[1] Definitive treatment includes endoscopic embolization or ligation, interventional radiological procedures such as portosystemic shunting or percutaneous embolization, and exploratory laparotomy to either resect the segment of bowel that is the source of bleeding or to decompress the collaterals surgically.[9] Although endoscopic ligation has been shown to have a lower rebleeding rate and mortality compared to endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in patients with esophageal varices, the data are too sparse in jejunal varices to recommend 1 treatment over another. Both have been used successfully either alone or in combination with each other, and can be useful alternatives for patients who are unable to undergo laparotomy.[9]

Diagnostic errors due to cognitive biases can be avoided by following diagnostic algorithms. However, over‐reliance on algorithms can result in vertical line failure, a form of cognitive bias in which the clinician subconsciously adheres to an inflexible diagnostic approach.[10] To overcome this bias, clinicians need to think laterally and consider alternative diagnoses when algorithms do not lead to expected outcomes. This case highlights the challenges of knowing when to break free of conventional approaches and the rewards of taking a well‐chosen detour that leads to the diagnosis.

KEY POINTS

- Recurrent, occult gastrointestinal bleeding should raise concern for a small bowel source, and clinicians may need to take a detour away from the usual workup to arrive at a diagnosis.

- CT angiography of the abdomen and pelvis may miss venous sources of bleeding, unless a venous phase is specifically requested.

- Ectopic varices can occur in patients with portal hypertension who have had a history of abdominal surgery; these patients can develop venous collaterals for decompression into the systemic circulation through the abdominal wall.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , . Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:322–334.

- , , . Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology. 1998;28:1154–1158.

- , , , et al. Current status of ectopic varices in Japan: results of a survey by the Japan Society for Portal Hypertension. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:763–766.

- , , . Stomal Varices: Management with decompression TIPS and transvenous obliteration or sclerosis. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;16:126–134.

- , , , et al. Jejunal varices as a cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:514–517.

- , . Ectopic varices in portal hypertension. Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;14:105–121.

- , , , et al. Ectopic varices in portal hypertension: computed tomographic angiography instead of repeated endoscopies for diagnosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:620–622.

- , , , et al. ACR appropriateness criteria. Radiologic management of lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2011. Available at: http://www.acr.org/Quality‐Safety/Appropriateness‐Criteria/∼/media/5F9CB95C164E4DA19DCBCFBBA790BB3C.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- , . Diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Gastrointest Interv. 2012;1:3–10.

- . Achieving quality in clinical decision making: cognitive strategies and detection of bias. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1184–1204.

- , , . Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:322–334.

- , , . Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology. 1998;28:1154–1158.

- , , , et al. Current status of ectopic varices in Japan: results of a survey by the Japan Society for Portal Hypertension. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:763–766.

- , , . Stomal Varices: Management with decompression TIPS and transvenous obliteration or sclerosis. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;16:126–134.

- , , , et al. Jejunal varices as a cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:514–517.

- , . Ectopic varices in portal hypertension. Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;14:105–121.

- , , , et al. Ectopic varices in portal hypertension: computed tomographic angiography instead of repeated endoscopies for diagnosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:620–622.

- , , , et al. ACR appropriateness criteria. Radiologic management of lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2011. Available at: http://www.acr.org/Quality‐Safety/Appropriateness‐Criteria/∼/media/5F9CB95C164E4DA19DCBCFBBA790BB3C.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- , . Diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Gastrointest Interv. 2012;1:3–10.

- . Achieving quality in clinical decision making: cognitive strategies and detection of bias. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1184–1204.

A clinician's guide to managing Helicobacter pylori infection

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

- Heartburn on 2 or more days a week warrants medical attention, as patients are likely to suffer from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).Chronic GERD can lead to the development of complications including erosive esophagitis, stricture formation, and Barrett’s esophagus, which increases the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

- A trial with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is the quickest and most cost-effective way to diagnose GERD, and is at least as sensitive as 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring.

- As PPIs only bind to actively secreting proton pumps, they should be dosed 30 to 60 minutes before a meal.Despite these recommendations, a recent survey of over 1000 US primary care physicians found that 36% instructed their patients to take a PPI with or after a meal or did not specify the timing of dosing.

- The patients who will have the best response to surgical therapy for GERD are those who had clearly documented acid reflux with typical symptoms, and who have responded to PPI treatment. Unfortunately, the same survey found that most physicians recommend antireflux surgery for patients in whom medical therapy has failed.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common, multifactorial condition that often results in decreased quality of life with interruptions of sleep, work, and social activities. Patients have reported that GERD affects emotional well-being to a greater degree than diabetes or hypertension.1,2 GERD is also associated with well-established complications, including Barrett’s esophagus. The role of reflux in carcinogenesis is controversial; the possibility of an association, however, implies that GERD should be treated aggressively and early.3

Symptoms of gerd

The typical symptoms of GERD are heartburn and regurgitation. Heartburn is best defined as a burning retrosternal discomfort starting in the epigastrium or lower chest and moving upwards towards the neck. Regurgitation is the effortless movement of gastric contents up into the esophagus or pharynx.

Most patients with GERD do not have endoscopically visible lesions; a careful analysis of symptoms generally forms the basis of a preliminary diagnosis.

The occurrence of heartburn on 2 or more days a week has been suggested as a basis for further investigation for GERD.4 However, symptoms vary greatly. Patients may be asymptomatic or experience symptoms that more closely resemble gastric disorders, infectious and motor disorders of the esophagus, biliary tract disease, or even coronary artery disease.

Extraesophageal manifestations

Adding to the complexity of diagnosis, GERD has been shown to have extraesophageal manifestations, including chronic cough, asthma, recurrent aspiration, chronic sore throat, reflux laryngitis, and paroxysmal laryngospasm or voice changes.

Although the relationship between asthma and GERD remains unclear, it has been estimated that 24% to 98% of patients with asthma also have GERD.5 Some patients with asthma have been shown to have excess acid reflux into the esophagus. Reflux-like symptoms may precede episodes of asthma that occur after meals or when lying down.6 8

Additionally, GERD has been noted in 10% to 50% of patients with non-cardiac chest pain.9,10

Diagnostic strategies

Trial of treatment

Diagnosis is usually based on typical symptoms—heartburn or regurgitation—in the clinical history. (The Figure shows a treatment algorithm for both severe and mild symptoms.)

A 2-week trial of treatment with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) provides the quickest and most cost-effective confirmation of diagnosis and is recommended for the patient whose history suggests uncomplicated GERD. A positive response to PPI treatment in a patient with symptoms suggestive of GERD is at least as sensitive and specific as 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring, which is still often considered the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of GERD. Furthermore, complete lack of improvement in response to PPI treatment is highly predictive that the patient does not have GERD and indicates the need for further evaluation and a possible revision of diagnosis.11,12

H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) have also been investigated in empirical trials for usefulness in diagnosing GERD. H2RAs are less effective than PPIs.13,14

FIGURE Medical management of suspected GERD

Endoscopy

No data support routine endoscopy for patients with the recent onset of uncomplicated heartburn who respond to medical therapy. Endoscopy is recommended, however, for patients with severe or atypical GERD symptoms, when other diseases may be present, or when a treatment trial with a PPI is ineffective.15 Endoscopy is useful for diagnosing complications of GERD, such as Barrett’s esophagus, esophagitis, and strictures. Fewer than 50% of patients with GERD symptoms have evidence of esophagitis on endoscopy.16

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends endoscopy when there are clinical suggestions of severe reflux or other disease.17 The American College of Gastroenterology recommends further testing

- when empiric therapy has failed

- when symptoms of complicated disease exist

- when there is dysphagia, bleeding, weight loss, choking, chest pain, or long-standing symptoms

- when continuous therapy is required

- to screen for Barrett’s esophagus.18

The Canadian Consensus Conference recommends endoscopy in the presence of

- dysphagia

- odynophagia

- bleeding

- weight loss

- noncardiac chest pain

- failure to respond to 4 to 8 weeks of pharmacologic therapy.19

It also recommends a single test if maintenance therapy is required.

Other diagnostic tests

Other diagnostic tools may be of use in some settings.

A barium esophagram can document reflux, and Bernstein testing (esophageal acid infusion test) can identify esophageal hypersensitivity to acid, although neither establishes a diagnosis of GERD. Ambulatory 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring can help to establish the presence of GERD by documenting the proportion of time during which the intraesophageal pH is acidic (<4) and can also establish the degree of association between patients’ symptoms and episodes of esophageal acidification.

Esophageal manometry is not recommended as a routine diagnostic test for GERD. It is important in selected patients to exclude an esophageal motility disorder and may be necessary as part of the pre-operative evaluation for patients in whom a surgical operation for GERD is being considered.

Management of gerd

GERD commonly requires long-term management that includes dietary, lifestyle, and pharmacological interventions. Surgery may be considered for the long-term management of the condition in carefully selected patients.

Diet and lifestyle

Dietary modifications. Patients should not consume large meals and should avoid lying down for 3 to 4 hours after eating. Caffeinated products, peppermint, fatty foods, chocolate, spicy foods, citrus fruits and juices, tomato-based products, and alcohol may contribute to episodes of GERD.18,21 Lozenges of any kind are able to stimulate salivary secretion, help clear refluxed acid, and hence, help relieve symptoms.

Lifestyle modifications. Changes in lifestyle may include such seemingly sensible interventions as sleeping with the head elevated, stopping smoking, and losing weight. There is little or no established evidence for the efficacy of these and other lifestyle modifications in the management of GERD. However, in1 trial of 63 patients, elevating the head of the bed with 6-inch blocks resulted in 1 less episode of heartburn or acid regurgitation per night when compared with lying flat.22 In another trial of 71 patients with esophagitis, elevating the bed was nearly as effective as ranitidine for reducing symptoms and producing endoscopically verifiable healing.23

Arecent survey20 of 1046 primary care physicians found that:

- 36% instructed patients to take PPIs during or after a meal or did not specify a time of dosing

- 75% referred patients for surgical antireflux therapy and 20% referred patients directly to a surgeon without gastrointestinal consultation

- 15% reported that a trial with a H2 receptor antagonist was required by their healthsystem or insurance company prior to using a PPI.

Drug interventions

Pharmacological interventions include over-the-counter remedies such as antacids and H2RAs (Table 1), as well as prescription-only doses of H2RAs and PPIs. At the time of writing, no PPI was available in an over-the-counter preparation in the United States, although over-the-counter omeprazole may soon be approved. Many authorities believe an incremental approach to the management of GERD is appropriate, beginning with lifestyle modifications and over-the-counter preparations, continuing with H2 blockers, and reserving PPIs for nonresponders. While this approach may have appeal from a cost perspective, we believe another approach (as illustrated in the Figure) is clinically superior.

Antacids. Over-the-counter antacids rapidly increase the pH of the intraesophageal contents and also neutralize acidic gastric contents that might be refluxed. They are frequently used to treat heartburn. However, few clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of antacids. Published trials24-26 are limited by small sample sizes and a lack of intention-to-treat analysis. Only 1 showed positive evidence for antacid efficacy.25

The utility of antacids is limited by the need for frequent dosing and possible interactions with such drugs as fluoroquinolones, tetracycline, and ferrous sulfate.27 Alginate/antacids have shown statistically significant benefit compared with placebo for relief of mild-to-moderate GERD symptoms and healing of esophagitis.24,28-34

H 2 receptor antagonists. H2RAs have shown positive effects on symptoms in some studies, although symptomatic response rates observed were only around 60% to 70%. Additionally, most of the trials to date have been for 2 to 6 weeks in duration.35 43 An issue worthy of consideration with the H2RAs is the development of tolerance with continuous use.44

An H2RA-antacid combination was recently evaluated in a trial that compared it with monotherapy using either agent. Of the patients receiving combination therapy, 81% reported an excellent or good symptom response. Those receiving famotidine or atacid alone reported a 72% excellent or good symptom response.3

Proton pump inhibitors. PPIs potently reduce gastric acid secretion by inhibiting the H+-K+adenosine triphosphatase pump of the parietal cell. As a result, they suppress gastric acid secretion for a longer period than H2RAs.45 Evidence from randomized, controlled trials has demonstrated the superiority of PPIs over any other class of drugs for the relief of GERD symptoms, for healing esophagitis, and for maintaining patients in remission. Standard doses of omeprazole, lansoprazole, panto-prazole, esomeprazole, and rabeprazole have, for the most part, shown comparable rates of healing and remission in erosive esophagitis.46-52

PPIs are best absorbed in the absence of food. Ingestion of food after a PPI stimulates parietal cell activity when blood levels of the PPI are increasing; this promotes uptake of the PPI by the parietal cells. Therefore, patients should be advised to take their PPI between 30 and 60 minutes before eating. For patients on a once-daily PPI, the best time to take it is about 30 to 60 minutes before breakfast. Despite these recommendations, a recent survey of over 1000 US primary care physicians found that 36% instructed their patients to take their PPI with or after a meal or did not specify the timing of dosing.53

Clinical evidence indicates that a trial with a PPI provides the quickest and most cost-effective method for diagnosing GERD. Despite this, many physicians use a trial of H2 receptor antagonists prior to initiation of PPI therapy.

- Clinicians should clearly instruct their patients regarding optimal timing of the dose, since this can have a significant effect on the success of therapy.

- Patients for whom antireflux surgery is being considered should first be referred for consultation with a gastroenterologist to assist in patient selection, to ensure that appropriate preoperative evaluation has been performed and to help exclude other possible causes of their symptoms.21,54

PPI therapy can be tailored to control GERD symptoms. Treatment can start with the most effective dosage and then be stepped down, or start with a minimum dosage and then be stepped up (Table 2). Patients with predominantly daytime symptoms should take PPIs before breakfast. Concerns that were once expressed about the long-term use of PPIs, such as predisposing patients to stomach cancer, have been refuted by extensive clinical experience and intensive monitoring (Table 3).3

TABLE 1

Over-the-counter therapy for GERD

|

| Adapted from Peterson, WL.GERD:Evidence-based therapeutic strategies. |

| Bethesda, Md.:American Gastroenterological Association;2002. |

TABLE 2

Step-down and step-up treatments: advantages and disadvantages

| Regimen | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Step-down therapy (high-dose initial therapy) | Rapid symptom relief | Potential overtreatment |

| Efficient for physician | Higher initial drug cost | |

| Avoids overinvestigation and associated costs | ||

| Step-up therapy (minimum-dose initial therapy) | Avoids overtreatment | Patient may continue with symptoms unnecessarily |

| Lower initial drug cost | Inefficient for physician | |

| May lead to overinvestigation | ||

| Uncertain end point (partial symptom relief) | ||

| Adapted from Dent J, et al. Management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in general practice.BMJ 2001;322:344-347. | ||

TABLE 3

Potential concerns associated with the use of proton pump inhibitors

| Potential concern | Level of Evidence* | Grade † | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term PPI treatment may lead to reduced serum cobalamin levels | 2b | B | This is most likely to occur in individuals with atrophic gastritis |

| Increased acid output has been seen after stopping a PPI | 2b | B | Effects of PPI treatment on corpus glandular atrophy in H pylori-infected individuals are difficult to interpret due to possible sampling error and short study duration |

| PPI treatment may predispose to bacterial enteric infection | 3 | B | Only shown in a single case control study |

| *Level of evidence:1, Evidence for and/or general agreement that treatment is useful and effective;1a, systematic review with homogeneity of randomized controlled trials (RCTs);1b, individual RCTs (with narrow confidence interval);2, conflicting evidence and/or divergent opinion about efficacy and use;2a, evidence or opinion is in favor of treatment;2b, use and efficacy is less well established by evidence or opinion;3, evidence and/or general agreement that treatment is not useful or effective and may be harmful in some cases. | |||

| †Quality grading:A, well-designed, clinical trials;B, well-designed cohort or case-control studies;C, case reports, flawed trials;D, personal clinical experience;E, insufficient evidence to form opinion. | |||

| Adapted from Peterson, WL.GERD:Evidence-based therapeutic strategies. Bethesda, Md:American Gastroenterological Association, 2002. | |||

Surgery

Surgical antireflux therapy is an option in carefully selected patients. Those who respond best to surgical therapy will have had clearly documented acid reflux, typical symptoms, and symptomatic improvement while on PPI treatment.54