User login

New ADA hypertension and diabetes treatment guide features visual aid

Clinicians can consult a diagram to plan treatment of hypertension in diabetes patients as part of the new American Diabetes Association guidelines.

“Diabetes and Hypertension: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association” was published in the September 2017 issue of Diabetes Care, and online on Aug. 22. The statement updates the ADA’s previous statement on hypertension and diabetes published in 2003.

“Numerous studies have shown that antihypertensive therapy reduces ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] events, heart failure, and microvascular complications in people with diabetes,” wrote Ian H. de Boer, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and his colleagues.

The statement is a collaboration between nine diabetes experts from the United States, Europe, and Australia whose specialties include endocrinology, nephrology, cardiology, and internal medicine (Diabetes Care. 2017 Sep.;40:1273-84).

The statement recommends that diabetes patients have their blood pressure checked at every routine clinical visit and that those with an elevated blood pressure on a clinical visit (defined as office-based measurements of 140/90 mm Hg and higher) have multiple measurements, including on a separate day to confirm the diagnosis.

In addition, during the initial evaluation, and then periodically, diabetes patients should be assessed for orthostatic hypotension “to individualize blood pressure goals, select the most appropriate antihypertensive agents, and minimize adverse effects of antihypertensive therapy,” according to the recommendations.

For most patients with diabetes and hypertension, the goal should be a blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg, and even lower targets may be appropriate for patients at high cardiovascular disease risk, the researchers said.

The guidelines include recommendations for managing hypertension and diabetes through lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity, achieving and maintaining a healthy weight, and following a healthy diet with minimal sodium intake and an emphasis on fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products.

The guidelines also emphasize the need for caution when treating older adults who are taking multiple medications. “Systolic blood pressure should be the main target of treatment,” for adults aged 65 years and older with diabetes and hypertension, the authors said.

In addition, the guidelines provide direction for clinicians treating pregnant women. “During pregnancy, treatment with ACE inhibitors, ARBs [angiotensin receptor blockers], or spironolactone is contraindicated, as [these medications] may cause fetal damage,” the authors wrote. Pregnant women with preexisting hypertension or with mild gestational hypertension with systolic blood pressure below 160 mm Hg, a diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg, and no sign of end-organ damage need not take antihypertensive medications, they said. For pregnant women who require antihypertensive treatment, the aim should be a systolic blood pressure between 120 mm Hg and 160 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure between 80 mm Hg and 105 mm Hg.

The authors concluded that there currently is insufficient evidence to support blood pressure medication for diabetes patients without hypertension.

The recommendations reference several key clinical trials that compared intensive and standard hypertension treatment strategies: the ACCORD BP (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes – Blood Pressure) trial, the ADVANCE BP (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation – Blood Pressure) trial, the HOT (Hypertension Optimal Treatment) trial, and SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial).

Lead author Dr. de Boer reported serving as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and his institution has received research equipment and supplies from Medtronic and Abbott. Study coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Merck, Abbott, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca.

Clinicians can consult a diagram to plan treatment of hypertension in diabetes patients as part of the new American Diabetes Association guidelines.

“Diabetes and Hypertension: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association” was published in the September 2017 issue of Diabetes Care, and online on Aug. 22. The statement updates the ADA’s previous statement on hypertension and diabetes published in 2003.

“Numerous studies have shown that antihypertensive therapy reduces ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] events, heart failure, and microvascular complications in people with diabetes,” wrote Ian H. de Boer, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and his colleagues.

The statement is a collaboration between nine diabetes experts from the United States, Europe, and Australia whose specialties include endocrinology, nephrology, cardiology, and internal medicine (Diabetes Care. 2017 Sep.;40:1273-84).

The statement recommends that diabetes patients have their blood pressure checked at every routine clinical visit and that those with an elevated blood pressure on a clinical visit (defined as office-based measurements of 140/90 mm Hg and higher) have multiple measurements, including on a separate day to confirm the diagnosis.

In addition, during the initial evaluation, and then periodically, diabetes patients should be assessed for orthostatic hypotension “to individualize blood pressure goals, select the most appropriate antihypertensive agents, and minimize adverse effects of antihypertensive therapy,” according to the recommendations.

For most patients with diabetes and hypertension, the goal should be a blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg, and even lower targets may be appropriate for patients at high cardiovascular disease risk, the researchers said.

The guidelines include recommendations for managing hypertension and diabetes through lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity, achieving and maintaining a healthy weight, and following a healthy diet with minimal sodium intake and an emphasis on fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products.

The guidelines also emphasize the need for caution when treating older adults who are taking multiple medications. “Systolic blood pressure should be the main target of treatment,” for adults aged 65 years and older with diabetes and hypertension, the authors said.

In addition, the guidelines provide direction for clinicians treating pregnant women. “During pregnancy, treatment with ACE inhibitors, ARBs [angiotensin receptor blockers], or spironolactone is contraindicated, as [these medications] may cause fetal damage,” the authors wrote. Pregnant women with preexisting hypertension or with mild gestational hypertension with systolic blood pressure below 160 mm Hg, a diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg, and no sign of end-organ damage need not take antihypertensive medications, they said. For pregnant women who require antihypertensive treatment, the aim should be a systolic blood pressure between 120 mm Hg and 160 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure between 80 mm Hg and 105 mm Hg.

The authors concluded that there currently is insufficient evidence to support blood pressure medication for diabetes patients without hypertension.

The recommendations reference several key clinical trials that compared intensive and standard hypertension treatment strategies: the ACCORD BP (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes – Blood Pressure) trial, the ADVANCE BP (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation – Blood Pressure) trial, the HOT (Hypertension Optimal Treatment) trial, and SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial).

Lead author Dr. de Boer reported serving as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and his institution has received research equipment and supplies from Medtronic and Abbott. Study coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Merck, Abbott, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca.

Clinicians can consult a diagram to plan treatment of hypertension in diabetes patients as part of the new American Diabetes Association guidelines.

“Diabetes and Hypertension: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association” was published in the September 2017 issue of Diabetes Care, and online on Aug. 22. The statement updates the ADA’s previous statement on hypertension and diabetes published in 2003.

“Numerous studies have shown that antihypertensive therapy reduces ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] events, heart failure, and microvascular complications in people with diabetes,” wrote Ian H. de Boer, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and his colleagues.

The statement is a collaboration between nine diabetes experts from the United States, Europe, and Australia whose specialties include endocrinology, nephrology, cardiology, and internal medicine (Diabetes Care. 2017 Sep.;40:1273-84).

The statement recommends that diabetes patients have their blood pressure checked at every routine clinical visit and that those with an elevated blood pressure on a clinical visit (defined as office-based measurements of 140/90 mm Hg and higher) have multiple measurements, including on a separate day to confirm the diagnosis.

In addition, during the initial evaluation, and then periodically, diabetes patients should be assessed for orthostatic hypotension “to individualize blood pressure goals, select the most appropriate antihypertensive agents, and minimize adverse effects of antihypertensive therapy,” according to the recommendations.

For most patients with diabetes and hypertension, the goal should be a blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg, and even lower targets may be appropriate for patients at high cardiovascular disease risk, the researchers said.

The guidelines include recommendations for managing hypertension and diabetes through lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity, achieving and maintaining a healthy weight, and following a healthy diet with minimal sodium intake and an emphasis on fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products.

The guidelines also emphasize the need for caution when treating older adults who are taking multiple medications. “Systolic blood pressure should be the main target of treatment,” for adults aged 65 years and older with diabetes and hypertension, the authors said.

In addition, the guidelines provide direction for clinicians treating pregnant women. “During pregnancy, treatment with ACE inhibitors, ARBs [angiotensin receptor blockers], or spironolactone is contraindicated, as [these medications] may cause fetal damage,” the authors wrote. Pregnant women with preexisting hypertension or with mild gestational hypertension with systolic blood pressure below 160 mm Hg, a diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg, and no sign of end-organ damage need not take antihypertensive medications, they said. For pregnant women who require antihypertensive treatment, the aim should be a systolic blood pressure between 120 mm Hg and 160 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure between 80 mm Hg and 105 mm Hg.

The authors concluded that there currently is insufficient evidence to support blood pressure medication for diabetes patients without hypertension.

The recommendations reference several key clinical trials that compared intensive and standard hypertension treatment strategies: the ACCORD BP (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes – Blood Pressure) trial, the ADVANCE BP (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation – Blood Pressure) trial, the HOT (Hypertension Optimal Treatment) trial, and SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial).

Lead author Dr. de Boer reported serving as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and his institution has received research equipment and supplies from Medtronic and Abbott. Study coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Merck, Abbott, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca.

FROM DIABETES CARE

VIDEO: What’s new in AAP’s pediatric hypertension guidelines

SAN FRANCISCO – The American Academy of Pediatrics recently released new hypertension guidelines for children and adolescents.

Some of the advice is similar to the group’s last effort in 2004, but there are a few key changes that clinicians need to know, according to lead author Joseph Flynn, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of nephrology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. He explained what they are, and the reasons behind them, in an interview at the joint hypertension scientific sessions sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension (Pediatrics. 2017 Aug 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904).

The prevalence of pediatric hypertension, he said, now rivals asthma.

SAN FRANCISCO – The American Academy of Pediatrics recently released new hypertension guidelines for children and adolescents.

Some of the advice is similar to the group’s last effort in 2004, but there are a few key changes that clinicians need to know, according to lead author Joseph Flynn, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of nephrology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. He explained what they are, and the reasons behind them, in an interview at the joint hypertension scientific sessions sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension (Pediatrics. 2017 Aug 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904).

The prevalence of pediatric hypertension, he said, now rivals asthma.

SAN FRANCISCO – The American Academy of Pediatrics recently released new hypertension guidelines for children and adolescents.

Some of the advice is similar to the group’s last effort in 2004, but there are a few key changes that clinicians need to know, according to lead author Joseph Flynn, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of nephrology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. He explained what they are, and the reasons behind them, in an interview at the joint hypertension scientific sessions sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension (Pediatrics. 2017 Aug 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904).

The prevalence of pediatric hypertension, he said, now rivals asthma.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA/ASH JOINT SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

New data prompt update to ACC guidance on nonstatin LDL lowering

The American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways has released a “focused update” for the 2016 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway (ECDP) on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

The update was deemed by the ECDP writing committee to be desirable given the additional evidence and perspectives that have emerged since the publication of the 2016 version, particularly with respect to the efficacy and safety of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for the secondary prevention of ASCVD, as well as the best use of ezetimibe in addition to statin therapy after acute coronary syndrome.

The ECDP algorithms endorse the four evidence-based statin benefit groups identified in the 2013 guidelines (adults aged 21 and older with clinical ASCVD, adults aged 21 and older with LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, adults aged 40-75 years without ASCVD but with diabetes and with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, and adults aged 40-75 without ASCVD or diabetes but with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL and an estimated 10-year risk for ASCVD of 7.5% or greater) and assume that the patient is currently taking or has attempted to take a statin, they noted.

Among the changes in the 2017 focused update are:

- Consideration of new randomized clinical trial data for the PCSK9 inhibitors evolocumab and bococizumab. Namely, they included results from the cardiovascular outcomes trials FOURIER (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk) and SPIRE-1 and SPIRE-2 (Studies of PCSK9 Inhibition and the Reduction of Vascular Events), which were published in early 2017.

- An adjustment in the ECDP algorithms with respect to thresholds for consideration of net ASCVD risk reduction. The 2016 ECDP thresholds for risk reduction benefit were percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C level in patients with clinical ASCVD, baseline LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, and primary prevention. In patients with diabetes with or without clinical ASCVD, clinicians were allowed to consider absolute LDL-C and/or non-HDL-cholesterol levels. In the 2017 ECDP update, the thresholds are percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C or non-HDL-C levels for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups. This change was based on the inclusion criteria of the FOURIER trial, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial (Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes after an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment with Alirocumab), and the SPIRE-2 trial, all of which included non-HDL-C thresholds. “In alignment with these inclusion criteria, the 2017 Focused Update includes both LDL-C and non-HDL-C thresholds for evaluation of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit when considering the addition of nonstatin therapies for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups” the update explained.

- An expansion of the threshold for consideration of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit from a reduction of LDL C of at least 50%, as well as consideration of LDL-C less than 70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C less than 100 mg/dL for all patients (that is, both those with and those without comorbidities) who have clinical ASCVD and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL. The 2016 ECDP had different thresholds for those with versus those without comorbidities. This change was based on findings from the FOURIER trial and the IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial).“Based on consideration of all available evidence, the consensus of the writing committee members is that lower LDL-C levels are safe and optimal in patients with clinical ASCVD due to [their] increased risk of recurrent events,” they said.

- An expanded recommendation on the use of ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibition. The 2016 ECDP stated that “if a decision is made to proceed with the addition of nonstatin therapy to maximally tolerated statin therapy, it is reasonable to consider the addition of ezetimibe as the initial agent and a PCSK9 inhibitor as the second agent.” However, based on the FOURIER findings, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial, and the IMPROVE-IT trial, the 2017 Focused Update states that, if such a decision is made in patients with clinical ASCVD with comorbidities and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, it is reasonable to weigh the addition of either ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor in light of “considerations of the additional percent LDL-C reduction desired, patient preferences, costs, route of administration, and other factors.” The update also spells out considerations that may favor the initial choice of ezetimibe versus a PCSK9 inhibitor (such as requiring less than 25% additional lowering of LDL-C, an age of over 75 years, cost, and other patient factors and preferences) .

- Additional factors, based on the FOURIER trial results and inclusion criteria, that may be considered for the identification of higher-risk patients with clinical ASCVD. The 2016 ECDP included on this list diabetes, a recent ASCVD event, an ASCVD event while already taking a statin, poorly controlled other major ASCVD risk factors, elevated lipoprotein, chronic kidney disease, symptomatic heart failure, maintenance hemodialysis, and baseline LDL-C of at least 190 mg/dL not due to secondary causes. The 2017 update added being 65 years or older, prior MI or nonhemorrhagic stroke, current daily cigarette smoking, symptomatic peripheral artery disease with prior MI or stroke, history of non-MI related coronary revascularization, residual coronary artery disease with at least 40% stenosis in at least two large vessels, HDL-C less than 40 mg/dL for men and less than 50 mg/dL for women, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein greater than 2 mg/L, and metabolic syndrome.

The content of the full ECDP has been changed in accordance with these updates and now includes more extensive and detailed guidance for decision making – both in the text and in treatment algorithms.

Aspects that remain unchanged include the decision pathways and algorithms for the use of ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors in primary prevention patients with LDL-C less than 190 mg/dL or in those without ASCVD and LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater unattributable to secondary causes.

In addition to other changes made for the purpose of clarification and consistency, recommendations regarding bile acid–sequestrant use were downgraded; these are now only recommended as optional secondary agents for consideration in patients who cannot tolerate ezetimibe.

“[These] recommendations attempt to provide practical guidance for clinicians and patients regarding the use of nonstatin therapies to further reduce ASCVD risk in situations not covered by the guideline until such time as the scientific evidence base expands and cardiovascular outcomes trials are completed with new agents for ASCVD risk reduction,” the committee concluded.

Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported having no disclosures.

The American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways has released a “focused update” for the 2016 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway (ECDP) on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

The update was deemed by the ECDP writing committee to be desirable given the additional evidence and perspectives that have emerged since the publication of the 2016 version, particularly with respect to the efficacy and safety of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for the secondary prevention of ASCVD, as well as the best use of ezetimibe in addition to statin therapy after acute coronary syndrome.

The ECDP algorithms endorse the four evidence-based statin benefit groups identified in the 2013 guidelines (adults aged 21 and older with clinical ASCVD, adults aged 21 and older with LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, adults aged 40-75 years without ASCVD but with diabetes and with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, and adults aged 40-75 without ASCVD or diabetes but with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL and an estimated 10-year risk for ASCVD of 7.5% or greater) and assume that the patient is currently taking or has attempted to take a statin, they noted.

Among the changes in the 2017 focused update are:

- Consideration of new randomized clinical trial data for the PCSK9 inhibitors evolocumab and bococizumab. Namely, they included results from the cardiovascular outcomes trials FOURIER (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk) and SPIRE-1 and SPIRE-2 (Studies of PCSK9 Inhibition and the Reduction of Vascular Events), which were published in early 2017.

- An adjustment in the ECDP algorithms with respect to thresholds for consideration of net ASCVD risk reduction. The 2016 ECDP thresholds for risk reduction benefit were percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C level in patients with clinical ASCVD, baseline LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, and primary prevention. In patients with diabetes with or without clinical ASCVD, clinicians were allowed to consider absolute LDL-C and/or non-HDL-cholesterol levels. In the 2017 ECDP update, the thresholds are percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C or non-HDL-C levels for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups. This change was based on the inclusion criteria of the FOURIER trial, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial (Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes after an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment with Alirocumab), and the SPIRE-2 trial, all of which included non-HDL-C thresholds. “In alignment with these inclusion criteria, the 2017 Focused Update includes both LDL-C and non-HDL-C thresholds for evaluation of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit when considering the addition of nonstatin therapies for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups” the update explained.

- An expansion of the threshold for consideration of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit from a reduction of LDL C of at least 50%, as well as consideration of LDL-C less than 70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C less than 100 mg/dL for all patients (that is, both those with and those without comorbidities) who have clinical ASCVD and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL. The 2016 ECDP had different thresholds for those with versus those without comorbidities. This change was based on findings from the FOURIER trial and the IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial).“Based on consideration of all available evidence, the consensus of the writing committee members is that lower LDL-C levels are safe and optimal in patients with clinical ASCVD due to [their] increased risk of recurrent events,” they said.

- An expanded recommendation on the use of ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibition. The 2016 ECDP stated that “if a decision is made to proceed with the addition of nonstatin therapy to maximally tolerated statin therapy, it is reasonable to consider the addition of ezetimibe as the initial agent and a PCSK9 inhibitor as the second agent.” However, based on the FOURIER findings, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial, and the IMPROVE-IT trial, the 2017 Focused Update states that, if such a decision is made in patients with clinical ASCVD with comorbidities and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, it is reasonable to weigh the addition of either ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor in light of “considerations of the additional percent LDL-C reduction desired, patient preferences, costs, route of administration, and other factors.” The update also spells out considerations that may favor the initial choice of ezetimibe versus a PCSK9 inhibitor (such as requiring less than 25% additional lowering of LDL-C, an age of over 75 years, cost, and other patient factors and preferences) .

- Additional factors, based on the FOURIER trial results and inclusion criteria, that may be considered for the identification of higher-risk patients with clinical ASCVD. The 2016 ECDP included on this list diabetes, a recent ASCVD event, an ASCVD event while already taking a statin, poorly controlled other major ASCVD risk factors, elevated lipoprotein, chronic kidney disease, symptomatic heart failure, maintenance hemodialysis, and baseline LDL-C of at least 190 mg/dL not due to secondary causes. The 2017 update added being 65 years or older, prior MI or nonhemorrhagic stroke, current daily cigarette smoking, symptomatic peripheral artery disease with prior MI or stroke, history of non-MI related coronary revascularization, residual coronary artery disease with at least 40% stenosis in at least two large vessels, HDL-C less than 40 mg/dL for men and less than 50 mg/dL for women, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein greater than 2 mg/L, and metabolic syndrome.

The content of the full ECDP has been changed in accordance with these updates and now includes more extensive and detailed guidance for decision making – both in the text and in treatment algorithms.

Aspects that remain unchanged include the decision pathways and algorithms for the use of ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors in primary prevention patients with LDL-C less than 190 mg/dL or in those without ASCVD and LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater unattributable to secondary causes.

In addition to other changes made for the purpose of clarification and consistency, recommendations regarding bile acid–sequestrant use were downgraded; these are now only recommended as optional secondary agents for consideration in patients who cannot tolerate ezetimibe.

“[These] recommendations attempt to provide practical guidance for clinicians and patients regarding the use of nonstatin therapies to further reduce ASCVD risk in situations not covered by the guideline until such time as the scientific evidence base expands and cardiovascular outcomes trials are completed with new agents for ASCVD risk reduction,” the committee concluded.

Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported having no disclosures.

The American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways has released a “focused update” for the 2016 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway (ECDP) on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

The update was deemed by the ECDP writing committee to be desirable given the additional evidence and perspectives that have emerged since the publication of the 2016 version, particularly with respect to the efficacy and safety of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for the secondary prevention of ASCVD, as well as the best use of ezetimibe in addition to statin therapy after acute coronary syndrome.

The ECDP algorithms endorse the four evidence-based statin benefit groups identified in the 2013 guidelines (adults aged 21 and older with clinical ASCVD, adults aged 21 and older with LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, adults aged 40-75 years without ASCVD but with diabetes and with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, and adults aged 40-75 without ASCVD or diabetes but with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL and an estimated 10-year risk for ASCVD of 7.5% or greater) and assume that the patient is currently taking or has attempted to take a statin, they noted.

Among the changes in the 2017 focused update are:

- Consideration of new randomized clinical trial data for the PCSK9 inhibitors evolocumab and bococizumab. Namely, they included results from the cardiovascular outcomes trials FOURIER (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk) and SPIRE-1 and SPIRE-2 (Studies of PCSK9 Inhibition and the Reduction of Vascular Events), which were published in early 2017.

- An adjustment in the ECDP algorithms with respect to thresholds for consideration of net ASCVD risk reduction. The 2016 ECDP thresholds for risk reduction benefit were percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C level in patients with clinical ASCVD, baseline LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, and primary prevention. In patients with diabetes with or without clinical ASCVD, clinicians were allowed to consider absolute LDL-C and/or non-HDL-cholesterol levels. In the 2017 ECDP update, the thresholds are percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C or non-HDL-C levels for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups. This change was based on the inclusion criteria of the FOURIER trial, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial (Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes after an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment with Alirocumab), and the SPIRE-2 trial, all of which included non-HDL-C thresholds. “In alignment with these inclusion criteria, the 2017 Focused Update includes both LDL-C and non-HDL-C thresholds for evaluation of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit when considering the addition of nonstatin therapies for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups” the update explained.

- An expansion of the threshold for consideration of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit from a reduction of LDL C of at least 50%, as well as consideration of LDL-C less than 70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C less than 100 mg/dL for all patients (that is, both those with and those without comorbidities) who have clinical ASCVD and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL. The 2016 ECDP had different thresholds for those with versus those without comorbidities. This change was based on findings from the FOURIER trial and the IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial).“Based on consideration of all available evidence, the consensus of the writing committee members is that lower LDL-C levels are safe and optimal in patients with clinical ASCVD due to [their] increased risk of recurrent events,” they said.

- An expanded recommendation on the use of ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibition. The 2016 ECDP stated that “if a decision is made to proceed with the addition of nonstatin therapy to maximally tolerated statin therapy, it is reasonable to consider the addition of ezetimibe as the initial agent and a PCSK9 inhibitor as the second agent.” However, based on the FOURIER findings, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial, and the IMPROVE-IT trial, the 2017 Focused Update states that, if such a decision is made in patients with clinical ASCVD with comorbidities and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, it is reasonable to weigh the addition of either ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor in light of “considerations of the additional percent LDL-C reduction desired, patient preferences, costs, route of administration, and other factors.” The update also spells out considerations that may favor the initial choice of ezetimibe versus a PCSK9 inhibitor (such as requiring less than 25% additional lowering of LDL-C, an age of over 75 years, cost, and other patient factors and preferences) .

- Additional factors, based on the FOURIER trial results and inclusion criteria, that may be considered for the identification of higher-risk patients with clinical ASCVD. The 2016 ECDP included on this list diabetes, a recent ASCVD event, an ASCVD event while already taking a statin, poorly controlled other major ASCVD risk factors, elevated lipoprotein, chronic kidney disease, symptomatic heart failure, maintenance hemodialysis, and baseline LDL-C of at least 190 mg/dL not due to secondary causes. The 2017 update added being 65 years or older, prior MI or nonhemorrhagic stroke, current daily cigarette smoking, symptomatic peripheral artery disease with prior MI or stroke, history of non-MI related coronary revascularization, residual coronary artery disease with at least 40% stenosis in at least two large vessels, HDL-C less than 40 mg/dL for men and less than 50 mg/dL for women, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein greater than 2 mg/L, and metabolic syndrome.

The content of the full ECDP has been changed in accordance with these updates and now includes more extensive and detailed guidance for decision making – both in the text and in treatment algorithms.

Aspects that remain unchanged include the decision pathways and algorithms for the use of ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors in primary prevention patients with LDL-C less than 190 mg/dL or in those without ASCVD and LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater unattributable to secondary causes.

In addition to other changes made for the purpose of clarification and consistency, recommendations regarding bile acid–sequestrant use were downgraded; these are now only recommended as optional secondary agents for consideration in patients who cannot tolerate ezetimibe.

“[These] recommendations attempt to provide practical guidance for clinicians and patients regarding the use of nonstatin therapies to further reduce ASCVD risk in situations not covered by the guideline until such time as the scientific evidence base expands and cardiovascular outcomes trials are completed with new agents for ASCVD risk reduction,” the committee concluded.

Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported having no disclosures.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

ASCO issues guideline on communication with patients

Recommendations for improved communication between oncologists and their patients are the focus of a new guideline issued by a panel convened by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The guideline recommends that oncologists establish care goals with each patient, address the costs of care, and initiate discussion of end-of-life preferences early in the course of incurable disease.

Patients also should be made aware of all treatment options, which may include clinical trials and, for certain patients, palliative care alone, the panel recommended.

The ASCO Expert Panel included medical oncologists, psychiatrists, nurses, and experts in hospice and palliative medicine, communication skills, health disparities, and advocacy. Their consensus-based, patient-clinician communication guideline drew on the panel’s systematic evaluation of guidelines, reviews and meta-analyses, and randomized, controlled trials published from 2006 through Oct. 1, 2016.

More specifics on the guideline are available here and feedback can be provided at asco.org/guidelineswiki.

Dr. Gilligan of the Taussig Cancer Institute and the Center for Excellence in Healthcare Communication, Cleveland Clinic, disclosed support from WellPoint; other panel members disclosed various consultancy roles or funding from pharmaceutical companies and CVS Health.

lnikolaides@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

Recommendations for improved communication between oncologists and their patients are the focus of a new guideline issued by a panel convened by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The guideline recommends that oncologists establish care goals with each patient, address the costs of care, and initiate discussion of end-of-life preferences early in the course of incurable disease.

Patients also should be made aware of all treatment options, which may include clinical trials and, for certain patients, palliative care alone, the panel recommended.

The ASCO Expert Panel included medical oncologists, psychiatrists, nurses, and experts in hospice and palliative medicine, communication skills, health disparities, and advocacy. Their consensus-based, patient-clinician communication guideline drew on the panel’s systematic evaluation of guidelines, reviews and meta-analyses, and randomized, controlled trials published from 2006 through Oct. 1, 2016.

More specifics on the guideline are available here and feedback can be provided at asco.org/guidelineswiki.

Dr. Gilligan of the Taussig Cancer Institute and the Center for Excellence in Healthcare Communication, Cleveland Clinic, disclosed support from WellPoint; other panel members disclosed various consultancy roles or funding from pharmaceutical companies and CVS Health.

lnikolaides@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

Recommendations for improved communication between oncologists and their patients are the focus of a new guideline issued by a panel convened by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The guideline recommends that oncologists establish care goals with each patient, address the costs of care, and initiate discussion of end-of-life preferences early in the course of incurable disease.

Patients also should be made aware of all treatment options, which may include clinical trials and, for certain patients, palliative care alone, the panel recommended.

The ASCO Expert Panel included medical oncologists, psychiatrists, nurses, and experts in hospice and palliative medicine, communication skills, health disparities, and advocacy. Their consensus-based, patient-clinician communication guideline drew on the panel’s systematic evaluation of guidelines, reviews and meta-analyses, and randomized, controlled trials published from 2006 through Oct. 1, 2016.

More specifics on the guideline are available here and feedback can be provided at asco.org/guidelineswiki.

Dr. Gilligan of the Taussig Cancer Institute and the Center for Excellence in Healthcare Communication, Cleveland Clinic, disclosed support from WellPoint; other panel members disclosed various consultancy roles or funding from pharmaceutical companies and CVS Health.

lnikolaides@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

Making Practice Perfect Download

Please click either of the links below to download your free eBook

Onecount Call To Arms

New recommendations tout biosimilars for rheumatologic diseases

The available evidence is sufficient to support switching appropriate patients with rheumatologic diseases from a bio-originator agent to an approved biosimilar agent, according to new consensus-based recommendations from an international multidisciplinary task force.

“Treatment with biological agents has dramatically improved the outcome for patients with inflammatory diseases. However, the high cost of these medications has limited access for many patients,” Jonathan Kay, MD, of UMass Memorial Medical Center and the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, and his colleagues wrote on behalf of the Task Force on the Use of Biosimilars to Treat Rheumatological Diseases. Biosimilars of agents no longer protected by patent allow for increased availability at lower costs, they noted. In the European Union, the United States, Japan, and other countries, biosimilars of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and rituximab have been approved, and those for which the bio-originator is no longer protected by patent have been marketed.

The task force, convened in 2016 to address the matter at an international level, included 25 experts from Europe, Japan, and the United States, including 17 rheumatologists, a rheumatologist/regulator, a dermatologist, a gastroenterologist, 2 pharmacologists, 2 patients, and a research fellow. The task force identified five overarching principles and made eight specific recommendations, based on expert opinion and an extensive literature review that yielded 29 relevant full-text papers and 20 relevant abstracts from the 2015 and 2016 American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism annual meetings (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Sep 2. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211937).

“This statement was intended both to guide clinicians and to serve as a framework for future educational efforts,” they wrote.

The experts based all five overarching principles for the use of biosimilars on level 5, grade D evidence, indicating that they were derived mainly from expert opinion. They determined that:

- Treatment of rheumatic diseases is based on a shared decision-making process between patients and their rheumatologists.

- The contextual aspects of the health care system should be taken into consideration when treatment decisions are made.

- A biosimilar, as approved by authorities in a highly regulated area, is neither better nor worse in efficacy and is not inferior in safety to its bio-originator.

- Patients and health care providers should be informed about the nature of biosimilars, their approval process, and their safety and efficacy.

- Harmonized methods should be established to obtain reliable pharmacovigilance data, including traceability, about both biosimilars and bio-originators.

These principles represent the key issues regarding biosimilars as identified by the task force. As for the specific recommendations, the task force agreed that:

1. The availability of biosimilars must significantly lower the cost of treating an individual patient and increase access to optimal therapy for all patients with rheumatic diseases (level 5, grade D evidence).

2. Approved biosimilars can be used to treat appropriate patients in the same way as their bio-originators (level 1b, grade A evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual randomized, controlled trial and that the level 1 evidence is consistent).

3. Antidrug antibodies to biosimilars need not be measured in clinical practice as no significant differences have been detected between biosimilars and their bio-originators (level 2b, grade B evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual cohort study/low-quality randomized, controlled trial and consistent level 2 or 3 evidence).

4. Relevant preclinical and phase 1 data on a biosimilar should be available when phase 3 data are published (level 5, grade D evidence).

5. Confirmation of efficacy and safety in a single indication is sufficient for extrapolation to other diseases for which the bio-originator has been approved because biosimilars are equivalent in physiochemical, functional, and pharmacokinetic properties to the bio-originator (level 5, grade D evidence).

6. Available evidence suggests that a single switch from a bio-originator to one of its biosimilars is safe and effective; there is no reason to expect a different clinical outcome. However, patient perspectives must be considered (level 1b, grade A evidence).

7. Multiple switching between biosimilars and their bio-originators or other biosimilars should be assessed in registries (level 5, grade D evidence).

8. No switch to or among biosimilars should be initiated without the prior awareness of the patient and the treating health care provider (level 5, grade D evidence).

Differing opinions about the use of biosimilars as published by various subspecialty organizations highlight a lack of confidence among many clinicians with respect to appropriate use of the products, but that is changing amid a rapidly growing body of evidence, the task force said. The group achieved a high level of agreement about both the evaluation of biosimilars and their use to treat rheumatologic diseases, reaching 100% consensus for six of the recommendations and 91% and 96% for the other two.

“Data available as of December 2016 support the use of biosimilars by rheumatologists to encourage a fair and competitive market for biologics. Biosimilars now provide an opportunity to expand access to effective but expensive medications, increasing the number of available treatment choices and helping to control rapidly increasing drug expenditures,” they concluded.

The task force’s work was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Amgen. Dr. Kay and his coauthors reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, many of which are developing biosimilars.

The available evidence is sufficient to support switching appropriate patients with rheumatologic diseases from a bio-originator agent to an approved biosimilar agent, according to new consensus-based recommendations from an international multidisciplinary task force.

“Treatment with biological agents has dramatically improved the outcome for patients with inflammatory diseases. However, the high cost of these medications has limited access for many patients,” Jonathan Kay, MD, of UMass Memorial Medical Center and the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, and his colleagues wrote on behalf of the Task Force on the Use of Biosimilars to Treat Rheumatological Diseases. Biosimilars of agents no longer protected by patent allow for increased availability at lower costs, they noted. In the European Union, the United States, Japan, and other countries, biosimilars of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and rituximab have been approved, and those for which the bio-originator is no longer protected by patent have been marketed.

The task force, convened in 2016 to address the matter at an international level, included 25 experts from Europe, Japan, and the United States, including 17 rheumatologists, a rheumatologist/regulator, a dermatologist, a gastroenterologist, 2 pharmacologists, 2 patients, and a research fellow. The task force identified five overarching principles and made eight specific recommendations, based on expert opinion and an extensive literature review that yielded 29 relevant full-text papers and 20 relevant abstracts from the 2015 and 2016 American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism annual meetings (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Sep 2. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211937).

“This statement was intended both to guide clinicians and to serve as a framework for future educational efforts,” they wrote.

The experts based all five overarching principles for the use of biosimilars on level 5, grade D evidence, indicating that they were derived mainly from expert opinion. They determined that:

- Treatment of rheumatic diseases is based on a shared decision-making process between patients and their rheumatologists.

- The contextual aspects of the health care system should be taken into consideration when treatment decisions are made.

- A biosimilar, as approved by authorities in a highly regulated area, is neither better nor worse in efficacy and is not inferior in safety to its bio-originator.

- Patients and health care providers should be informed about the nature of biosimilars, their approval process, and their safety and efficacy.

- Harmonized methods should be established to obtain reliable pharmacovigilance data, including traceability, about both biosimilars and bio-originators.

These principles represent the key issues regarding biosimilars as identified by the task force. As for the specific recommendations, the task force agreed that:

1. The availability of biosimilars must significantly lower the cost of treating an individual patient and increase access to optimal therapy for all patients with rheumatic diseases (level 5, grade D evidence).

2. Approved biosimilars can be used to treat appropriate patients in the same way as their bio-originators (level 1b, grade A evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual randomized, controlled trial and that the level 1 evidence is consistent).

3. Antidrug antibodies to biosimilars need not be measured in clinical practice as no significant differences have been detected between biosimilars and their bio-originators (level 2b, grade B evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual cohort study/low-quality randomized, controlled trial and consistent level 2 or 3 evidence).

4. Relevant preclinical and phase 1 data on a biosimilar should be available when phase 3 data are published (level 5, grade D evidence).

5. Confirmation of efficacy and safety in a single indication is sufficient for extrapolation to other diseases for which the bio-originator has been approved because biosimilars are equivalent in physiochemical, functional, and pharmacokinetic properties to the bio-originator (level 5, grade D evidence).

6. Available evidence suggests that a single switch from a bio-originator to one of its biosimilars is safe and effective; there is no reason to expect a different clinical outcome. However, patient perspectives must be considered (level 1b, grade A evidence).

7. Multiple switching between biosimilars and their bio-originators or other biosimilars should be assessed in registries (level 5, grade D evidence).

8. No switch to or among biosimilars should be initiated without the prior awareness of the patient and the treating health care provider (level 5, grade D evidence).

Differing opinions about the use of biosimilars as published by various subspecialty organizations highlight a lack of confidence among many clinicians with respect to appropriate use of the products, but that is changing amid a rapidly growing body of evidence, the task force said. The group achieved a high level of agreement about both the evaluation of biosimilars and their use to treat rheumatologic diseases, reaching 100% consensus for six of the recommendations and 91% and 96% for the other two.

“Data available as of December 2016 support the use of biosimilars by rheumatologists to encourage a fair and competitive market for biologics. Biosimilars now provide an opportunity to expand access to effective but expensive medications, increasing the number of available treatment choices and helping to control rapidly increasing drug expenditures,” they concluded.

The task force’s work was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Amgen. Dr. Kay and his coauthors reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, many of which are developing biosimilars.

The available evidence is sufficient to support switching appropriate patients with rheumatologic diseases from a bio-originator agent to an approved biosimilar agent, according to new consensus-based recommendations from an international multidisciplinary task force.

“Treatment with biological agents has dramatically improved the outcome for patients with inflammatory diseases. However, the high cost of these medications has limited access for many patients,” Jonathan Kay, MD, of UMass Memorial Medical Center and the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, and his colleagues wrote on behalf of the Task Force on the Use of Biosimilars to Treat Rheumatological Diseases. Biosimilars of agents no longer protected by patent allow for increased availability at lower costs, they noted. In the European Union, the United States, Japan, and other countries, biosimilars of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and rituximab have been approved, and those for which the bio-originator is no longer protected by patent have been marketed.

The task force, convened in 2016 to address the matter at an international level, included 25 experts from Europe, Japan, and the United States, including 17 rheumatologists, a rheumatologist/regulator, a dermatologist, a gastroenterologist, 2 pharmacologists, 2 patients, and a research fellow. The task force identified five overarching principles and made eight specific recommendations, based on expert opinion and an extensive literature review that yielded 29 relevant full-text papers and 20 relevant abstracts from the 2015 and 2016 American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism annual meetings (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Sep 2. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211937).

“This statement was intended both to guide clinicians and to serve as a framework for future educational efforts,” they wrote.

The experts based all five overarching principles for the use of biosimilars on level 5, grade D evidence, indicating that they were derived mainly from expert opinion. They determined that:

- Treatment of rheumatic diseases is based on a shared decision-making process between patients and their rheumatologists.

- The contextual aspects of the health care system should be taken into consideration when treatment decisions are made.

- A biosimilar, as approved by authorities in a highly regulated area, is neither better nor worse in efficacy and is not inferior in safety to its bio-originator.

- Patients and health care providers should be informed about the nature of biosimilars, their approval process, and their safety and efficacy.

- Harmonized methods should be established to obtain reliable pharmacovigilance data, including traceability, about both biosimilars and bio-originators.

These principles represent the key issues regarding biosimilars as identified by the task force. As for the specific recommendations, the task force agreed that:

1. The availability of biosimilars must significantly lower the cost of treating an individual patient and increase access to optimal therapy for all patients with rheumatic diseases (level 5, grade D evidence).

2. Approved biosimilars can be used to treat appropriate patients in the same way as their bio-originators (level 1b, grade A evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual randomized, controlled trial and that the level 1 evidence is consistent).

3. Antidrug antibodies to biosimilars need not be measured in clinical practice as no significant differences have been detected between biosimilars and their bio-originators (level 2b, grade B evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual cohort study/low-quality randomized, controlled trial and consistent level 2 or 3 evidence).

4. Relevant preclinical and phase 1 data on a biosimilar should be available when phase 3 data are published (level 5, grade D evidence).

5. Confirmation of efficacy and safety in a single indication is sufficient for extrapolation to other diseases for which the bio-originator has been approved because biosimilars are equivalent in physiochemical, functional, and pharmacokinetic properties to the bio-originator (level 5, grade D evidence).

6. Available evidence suggests that a single switch from a bio-originator to one of its biosimilars is safe and effective; there is no reason to expect a different clinical outcome. However, patient perspectives must be considered (level 1b, grade A evidence).

7. Multiple switching between biosimilars and their bio-originators or other biosimilars should be assessed in registries (level 5, grade D evidence).

8. No switch to or among biosimilars should be initiated without the prior awareness of the patient and the treating health care provider (level 5, grade D evidence).

Differing opinions about the use of biosimilars as published by various subspecialty organizations highlight a lack of confidence among many clinicians with respect to appropriate use of the products, but that is changing amid a rapidly growing body of evidence, the task force said. The group achieved a high level of agreement about both the evaluation of biosimilars and their use to treat rheumatologic diseases, reaching 100% consensus for six of the recommendations and 91% and 96% for the other two.

“Data available as of December 2016 support the use of biosimilars by rheumatologists to encourage a fair and competitive market for biologics. Biosimilars now provide an opportunity to expand access to effective but expensive medications, increasing the number of available treatment choices and helping to control rapidly increasing drug expenditures,” they concluded.

The task force’s work was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Amgen. Dr. Kay and his coauthors reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, many of which are developing biosimilars.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Latest recommendations for the 2017-2018 flu season

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported details of the 2016-2017 influenza season in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report1 and at the June meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. The CDC monitors influenza activity using several systems, and last flu season was shown to be moderately severe, starting in December in the Western United States, moving east, and peaking in February.

During the peak, 5.1% of outpatient visits were attributed to influenza-like illnesses, and 8.2% of reported deaths were due to pneumonia and influenza. For the whole influenza season, there were more than 18,000 confirmed influenza-related hospitalizations, with 60% of these occurring among those ≥65 years.1 Confirmed influenza-associated pediatric deaths totaled 98.1

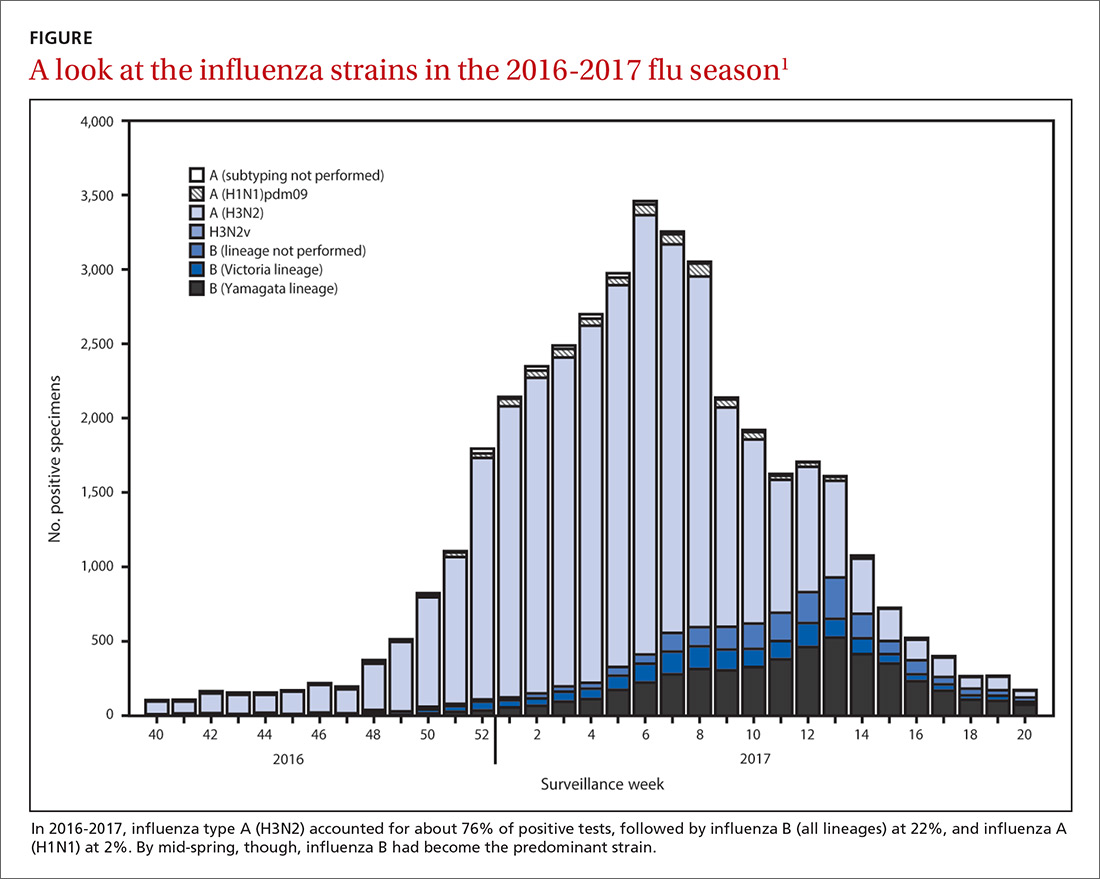

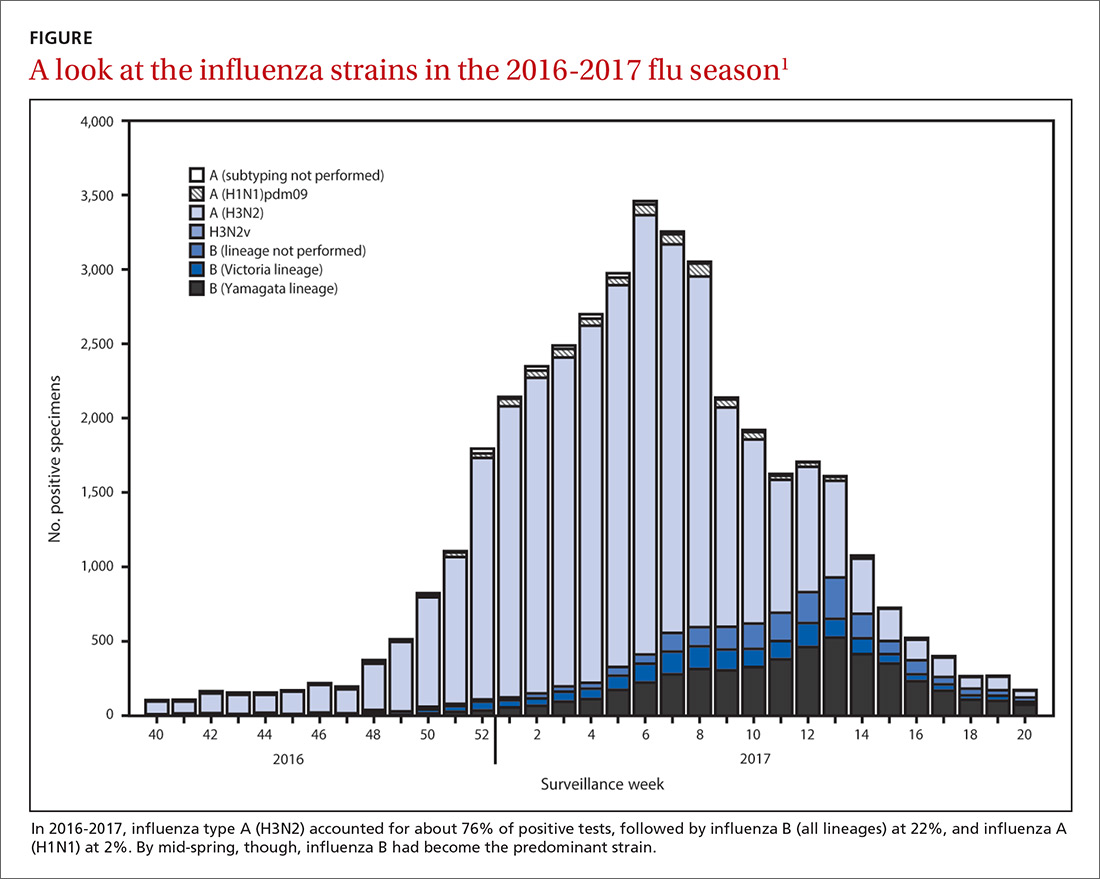

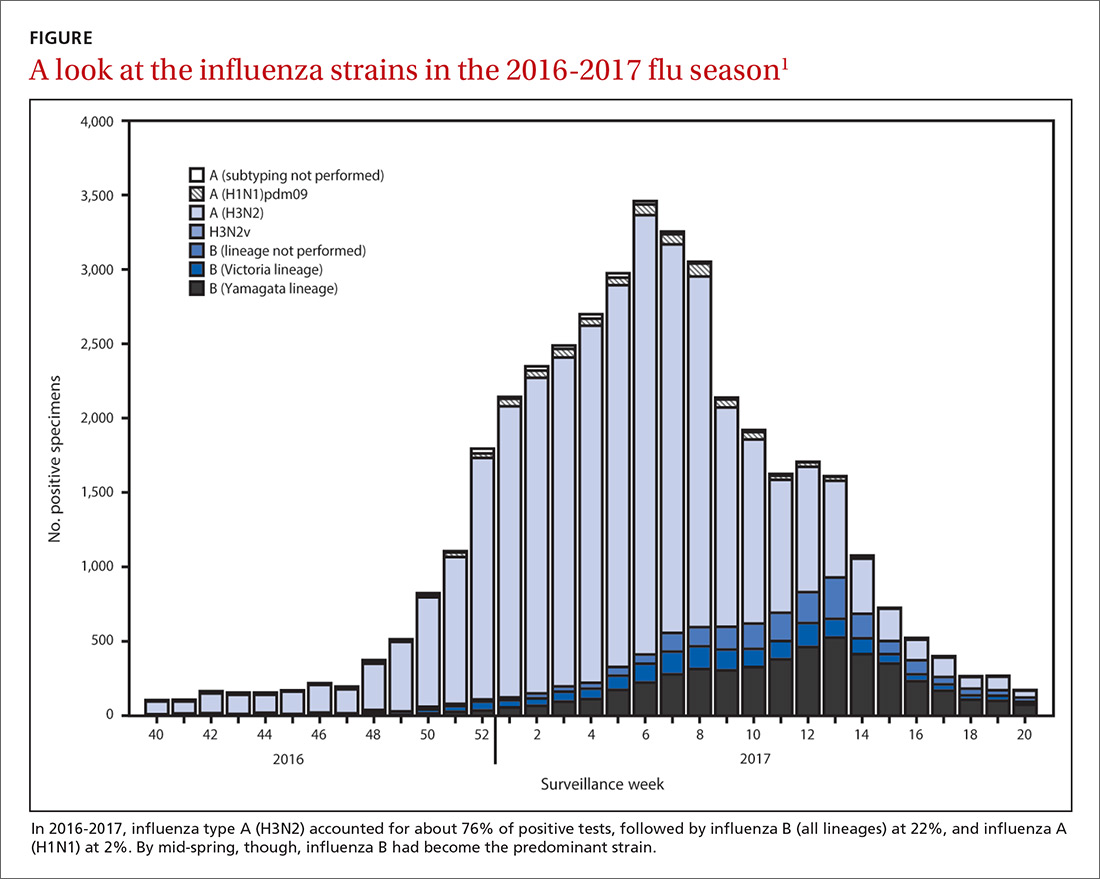

The predominant influenza strain last year was type A (H3N2), accounting for about 76% of positive tests in public health laboratories (FIGURE).1 This was followed by influenza B (all lineages) at 22%, and influenza A (H1N1), accounting for only 2%. However, in early April, the predominant strain changed from A (H3N2) to influenza B. Importantly, all viruses tested last year were sensitive to oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir. No antiviral resistance was detected to these neuraminidase inhibitors.

Good news and bad news on vaccine effectiveness. The good news: Circulating viruses were a close match to those contained in the vaccine. The bad news: Vaccine effectiveness at preventing illness was estimated to be just 34% against A (H3N2) and 56% against influenza B viruses.1 There has been no analysis of the relative effectiveness of different vaccines and vaccine types.

The past 6 influenza seasons have revealed a pattern of lower vaccine effectiveness against A (H3N2) compared with effectiveness against A (H1N1) and influenza B viruses. While vaccine effectiveness is not optimal, routine universal use still prevents a great deal of mortality and morbidity. It’s estimated that in 2012-2013, vaccine effectiveness (comparable to that in 2016-2017) prevented 5.6 million illnesses, 2.7 million medical visits, 61,500 hospitalizations, and 1800 deaths.1

More good news: Vaccine safety studies are reassuring

The CDC monitors influenza vaccine safety by using several sources, including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System and the Vaccine Safety Datalink.2

Changes for the 2017-2018 influenza season

The composition of influenza vaccine products for the 2017-2018 season will differ slightly from last year’s formulation in the H1N1 component. Viral antigens to be included in the trivalent products are A/Michigan (H1N1), A/Hong Kong (H3N2), and B/Brisbane.3 Quadrivalent products will add B/Phuket to the other 3 antigens.3 A wide array of influenza vaccine products is available. Each one is described on the CDC Web site.4

Two minor changes in the recommendations were made at the June ACIP meeting.5 Afluria is approved by the FDA for use in children starting at age 5 years. ACIP had recommended that its use be reserved for children 9 years and older because previous influenza seasons had raised concerns about increased rates of febrile seizures in children younger than age 9. These concerns have been resolved, however, and the ACIP recommendations are now in concert with those of the FDA for this product.

Influenza immunization with an inactivated influenza vaccine product has been recommended for all pregnant women. Safety data are increasingly available for other product options as well, and ACIP now recommends vaccination in pregnancy with any age-appropriate product except for live attenuated influenza vaccine. 5

Antivirals: Give as needed, even before lab confirmation

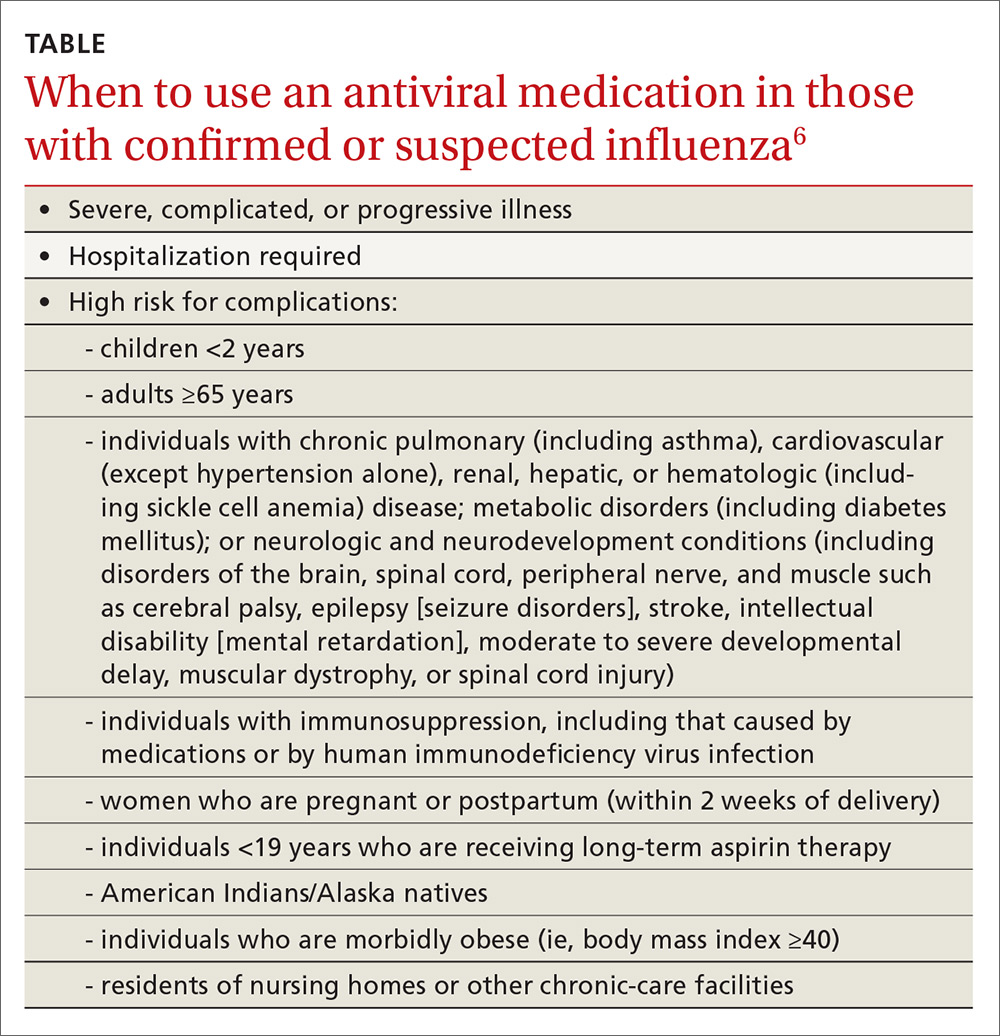

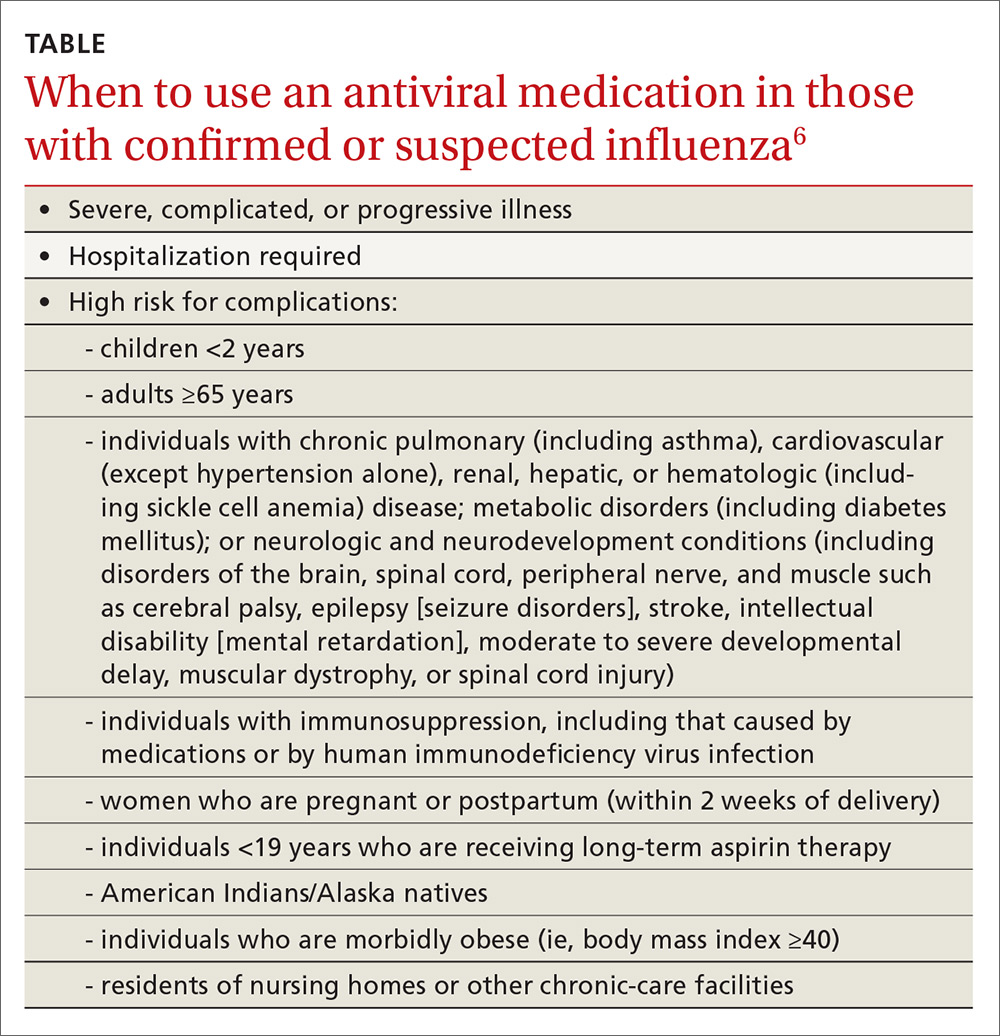

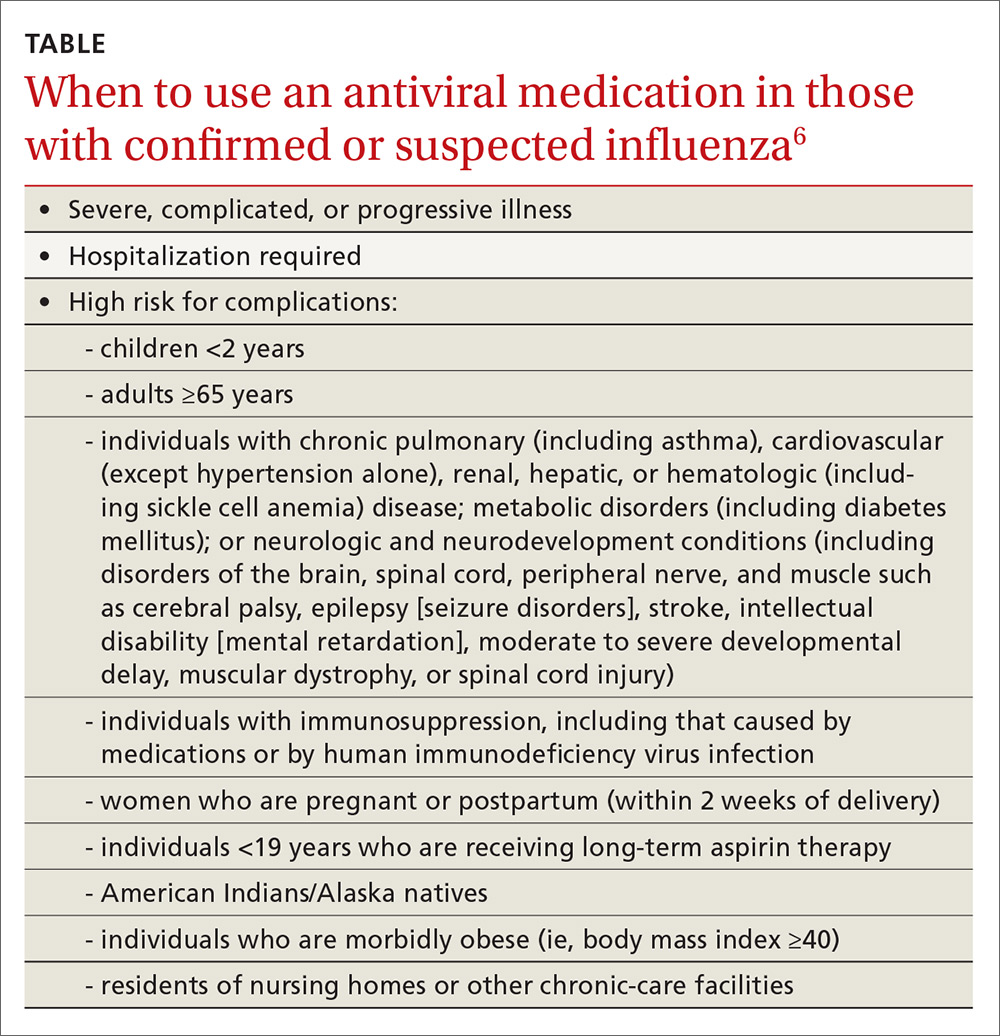

The CDC recommends antiviral medication for individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza who have severe, complicated, or progressive illness, who require hospitalization, or who are at high risk of complications from influenza (TABLE6). Start treatment without waiting for laboratory confirmation for those with suspected influenza who are seriously ill. Outcomes are best when antivirals are started within 48 hours of illness onset, but they can be started even after this “window” has passed.

Once antiviral treatment has begun, make sure the full 5-day course is completed regardless of culture or rapid-test results.6 Use only neuraminidase inhibitors, as there is widespread resistance to adamantanes among influenza A viruses.

Influenza can occur year round

Rates of influenza infection are low in the summer, but cases do occur. Be especially alert if patients with influenza-like illness have been exposed to swine or poultry; they may have contracted a novel influenza A virus. Report such cases to the state or local health department so that staff can facilitate laboratory testing of viral subtypes. Follow the same protocol for patients with influenza symptoms who have traveled to areas where avian influenza viruses have been detected. The CDC is interested in detecting novel influenza viruses, which can start a pandemic.

Prepare for the 2017-2018 influenza season

Family physicians can help prevent influenza and its associated morbidity and mortality in several ways. Offer immunization to all patients, and immunize all health care personnel in your offices and clinics. Treat with antivirals those for whom they are recommended. Prepare office triage policies that prevent patients with flu symptoms from mixing with other patients, ensure that clinic infection control practices are enforced, and advise ill patients to avoid exposing others.7 Finally, stay current on influenza epidemiology and changes in recommendations for treatment and vaccination.

1. Blanton L, Alabi N, Mustaquim D, et al. Update: Influenza activity in the United States during the 2016-2017 season and composition of the 2017-2018 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:668-676.

2. Shimabukuro T. End-of-season update: 2016-2017 influenza vaccine safety monitoring. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 21, 2017; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-06/flu-04-shimabukuro.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. CDC. Frequently asked flu questions 2017-2018 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season-2017-2018.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

4. CDC. Influenza vaccines — United States, 2016-17 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/vaccine/vaccines.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

5. Grohskopf L. Influenza WG considerations and proposed recommendations. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 21, 2017; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-06/flu-06-grohskopf.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

6. CDC. Use of antivirals. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/antiviral-use-influenza.htm#Box. Accessed July 17, 2017.

7. CDC. Prevention strategies for seasonal influenza in healthcare settings. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/healthcaresettings.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported details of the 2016-2017 influenza season in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report1 and at the June meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. The CDC monitors influenza activity using several systems, and last flu season was shown to be moderately severe, starting in December in the Western United States, moving east, and peaking in February.

During the peak, 5.1% of outpatient visits were attributed to influenza-like illnesses, and 8.2% of reported deaths were due to pneumonia and influenza. For the whole influenza season, there were more than 18,000 confirmed influenza-related hospitalizations, with 60% of these occurring among those ≥65 years.1 Confirmed influenza-associated pediatric deaths totaled 98.1

The predominant influenza strain last year was type A (H3N2), accounting for about 76% of positive tests in public health laboratories (FIGURE).1 This was followed by influenza B (all lineages) at 22%, and influenza A (H1N1), accounting for only 2%. However, in early April, the predominant strain changed from A (H3N2) to influenza B. Importantly, all viruses tested last year were sensitive to oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir. No antiviral resistance was detected to these neuraminidase inhibitors.

Good news and bad news on vaccine effectiveness. The good news: Circulating viruses were a close match to those contained in the vaccine. The bad news: Vaccine effectiveness at preventing illness was estimated to be just 34% against A (H3N2) and 56% against influenza B viruses.1 There has been no analysis of the relative effectiveness of different vaccines and vaccine types.

The past 6 influenza seasons have revealed a pattern of lower vaccine effectiveness against A (H3N2) compared with effectiveness against A (H1N1) and influenza B viruses. While vaccine effectiveness is not optimal, routine universal use still prevents a great deal of mortality and morbidity. It’s estimated that in 2012-2013, vaccine effectiveness (comparable to that in 2016-2017) prevented 5.6 million illnesses, 2.7 million medical visits, 61,500 hospitalizations, and 1800 deaths.1

More good news: Vaccine safety studies are reassuring

The CDC monitors influenza vaccine safety by using several sources, including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System and the Vaccine Safety Datalink.2

Changes for the 2017-2018 influenza season

The composition of influenza vaccine products for the 2017-2018 season will differ slightly from last year’s formulation in the H1N1 component. Viral antigens to be included in the trivalent products are A/Michigan (H1N1), A/Hong Kong (H3N2), and B/Brisbane.3 Quadrivalent products will add B/Phuket to the other 3 antigens.3 A wide array of influenza vaccine products is available. Each one is described on the CDC Web site.4

Two minor changes in the recommendations were made at the June ACIP meeting.5 Afluria is approved by the FDA for use in children starting at age 5 years. ACIP had recommended that its use be reserved for children 9 years and older because previous influenza seasons had raised concerns about increased rates of febrile seizures in children younger than age 9. These concerns have been resolved, however, and the ACIP recommendations are now in concert with those of the FDA for this product.

Influenza immunization with an inactivated influenza vaccine product has been recommended for all pregnant women. Safety data are increasingly available for other product options as well, and ACIP now recommends vaccination in pregnancy with any age-appropriate product except for live attenuated influenza vaccine. 5

Antivirals: Give as needed, even before lab confirmation

The CDC recommends antiviral medication for individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza who have severe, complicated, or progressive illness, who require hospitalization, or who are at high risk of complications from influenza (TABLE6). Start treatment without waiting for laboratory confirmation for those with suspected influenza who are seriously ill. Outcomes are best when antivirals are started within 48 hours of illness onset, but they can be started even after this “window” has passed.

Once antiviral treatment has begun, make sure the full 5-day course is completed regardless of culture or rapid-test results.6 Use only neuraminidase inhibitors, as there is widespread resistance to adamantanes among influenza A viruses.

Influenza can occur year round

Rates of influenza infection are low in the summer, but cases do occur. Be especially alert if patients with influenza-like illness have been exposed to swine or poultry; they may have contracted a novel influenza A virus. Report such cases to the state or local health department so that staff can facilitate laboratory testing of viral subtypes. Follow the same protocol for patients with influenza symptoms who have traveled to areas where avian influenza viruses have been detected. The CDC is interested in detecting novel influenza viruses, which can start a pandemic.

Prepare for the 2017-2018 influenza season

Family physicians can help prevent influenza and its associated morbidity and mortality in several ways. Offer immunization to all patients, and immunize all health care personnel in your offices and clinics. Treat with antivirals those for whom they are recommended. Prepare office triage policies that prevent patients with flu symptoms from mixing with other patients, ensure that clinic infection control practices are enforced, and advise ill patients to avoid exposing others.7 Finally, stay current on influenza epidemiology and changes in recommendations for treatment and vaccination.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported details of the 2016-2017 influenza season in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report1 and at the June meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. The CDC monitors influenza activity using several systems, and last flu season was shown to be moderately severe, starting in December in the Western United States, moving east, and peaking in February.

During the peak, 5.1% of outpatient visits were attributed to influenza-like illnesses, and 8.2% of reported deaths were due to pneumonia and influenza. For the whole influenza season, there were more than 18,000 confirmed influenza-related hospitalizations, with 60% of these occurring among those ≥65 years.1 Confirmed influenza-associated pediatric deaths totaled 98.1

The predominant influenza strain last year was type A (H3N2), accounting for about 76% of positive tests in public health laboratories (FIGURE).1 This was followed by influenza B (all lineages) at 22%, and influenza A (H1N1), accounting for only 2%. However, in early April, the predominant strain changed from A (H3N2) to influenza B. Importantly, all viruses tested last year were sensitive to oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir. No antiviral resistance was detected to these neuraminidase inhibitors.

Good news and bad news on vaccine effectiveness. The good news: Circulating viruses were a close match to those contained in the vaccine. The bad news: Vaccine effectiveness at preventing illness was estimated to be just 34% against A (H3N2) and 56% against influenza B viruses.1 There has been no analysis of the relative effectiveness of different vaccines and vaccine types.

The past 6 influenza seasons have revealed a pattern of lower vaccine effectiveness against A (H3N2) compared with effectiveness against A (H1N1) and influenza B viruses. While vaccine effectiveness is not optimal, routine universal use still prevents a great deal of mortality and morbidity. It’s estimated that in 2012-2013, vaccine effectiveness (comparable to that in 2016-2017) prevented 5.6 million illnesses, 2.7 million medical visits, 61,500 hospitalizations, and 1800 deaths.1

More good news: Vaccine safety studies are reassuring

The CDC monitors influenza vaccine safety by using several sources, including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System and the Vaccine Safety Datalink.2

Changes for the 2017-2018 influenza season

The composition of influenza vaccine products for the 2017-2018 season will differ slightly from last year’s formulation in the H1N1 component. Viral antigens to be included in the trivalent products are A/Michigan (H1N1), A/Hong Kong (H3N2), and B/Brisbane.3 Quadrivalent products will add B/Phuket to the other 3 antigens.3 A wide array of influenza vaccine products is available. Each one is described on the CDC Web site.4

Two minor changes in the recommendations were made at the June ACIP meeting.5 Afluria is approved by the FDA for use in children starting at age 5 years. ACIP had recommended that its use be reserved for children 9 years and older because previous influenza seasons had raised concerns about increased rates of febrile seizures in children younger than age 9. These concerns have been resolved, however, and the ACIP recommendations are now in concert with those of the FDA for this product.

Influenza immunization with an inactivated influenza vaccine product has been recommended for all pregnant women. Safety data are increasingly available for other product options as well, and ACIP now recommends vaccination in pregnancy with any age-appropriate product except for live attenuated influenza vaccine. 5

Antivirals: Give as needed, even before lab confirmation

The CDC recommends antiviral medication for individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza who have severe, complicated, or progressive illness, who require hospitalization, or who are at high risk of complications from influenza (TABLE6). Start treatment without waiting for laboratory confirmation for those with suspected influenza who are seriously ill. Outcomes are best when antivirals are started within 48 hours of illness onset, but they can be started even after this “window” has passed.

Once antiviral treatment has begun, make sure the full 5-day course is completed regardless of culture or rapid-test results.6 Use only neuraminidase inhibitors, as there is widespread resistance to adamantanes among influenza A viruses.

Influenza can occur year round

Rates of influenza infection are low in the summer, but cases do occur. Be especially alert if patients with influenza-like illness have been exposed to swine or poultry; they may have contracted a novel influenza A virus. Report such cases to the state or local health department so that staff can facilitate laboratory testing of viral subtypes. Follow the same protocol for patients with influenza symptoms who have traveled to areas where avian influenza viruses have been detected. The CDC is interested in detecting novel influenza viruses, which can start a pandemic.

Prepare for the 2017-2018 influenza season

Family physicians can help prevent influenza and its associated morbidity and mortality in several ways. Offer immunization to all patients, and immunize all health care personnel in your offices and clinics. Treat with antivirals those for whom they are recommended. Prepare office triage policies that prevent patients with flu symptoms from mixing with other patients, ensure that clinic infection control practices are enforced, and advise ill patients to avoid exposing others.7 Finally, stay current on influenza epidemiology and changes in recommendations for treatment and vaccination.

1. Blanton L, Alabi N, Mustaquim D, et al. Update: Influenza activity in the United States during the 2016-2017 season and composition of the 2017-2018 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:668-676.

2. Shimabukuro T. End-of-season update: 2016-2017 influenza vaccine safety monitoring. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 21, 2017; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-06/flu-04-shimabukuro.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. CDC. Frequently asked flu questions 2017-2018 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season-2017-2018.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

4. CDC. Influenza vaccines — United States, 2016-17 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/vaccine/vaccines.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

5. Grohskopf L. Influenza WG considerations and proposed recommendations. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 21, 2017; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-06/flu-06-grohskopf.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

6. CDC. Use of antivirals. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/antiviral-use-influenza.htm#Box. Accessed July 17, 2017.

7. CDC. Prevention strategies for seasonal influenza in healthcare settings. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/healthcaresettings.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

1. Blanton L, Alabi N, Mustaquim D, et al. Update: Influenza activity in the United States during the 2016-2017 season and composition of the 2017-2018 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:668-676.